-

Posts

1,752 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Mark P

-

Good Afternoon Brunnells; I have a large selection of English boxwood (I know it is because I cut the branches from the trees myself, or got them from gardeners who had cut them down, with the leaves still on them) This has a good range of colour, and some of it is indeed very noticeably yellow. Some is very pale yellow, more of a cream colour, and there is a whole variety of inbetween shades. Some of it has no grain visible at all; some is prominently marked, with the end-grain looking like pine softwood; which of course it isn't, it is much too heavy, and must be the result of some growth rings being very close together, with others which are more dispersed. The main characteristics are that it is heavy, hard, and extremely fine-grained. Below is a picture of a model made with boxwood planking, which is very yellow; presumably sealed with something, but the colour looks lovely. All the best, Mark P

-

Thank you Morgan; That is a really interesting picture. My immediate reaction is that it is 17th century, for two reasons: Firstly, the underside of the floor timbers have notches in each timber for the limber passage. Secondly, the futtocks appear to stop short of the keel, which is strongly indicative also. However, more photos would make it clearer. I will see if I can contact the chap who took the pictures. The closeness of the timbers would also seem to indicate a warship, although I would not state that with any certainty. I don't think it is a particularly large vessel, as the outer planking appears to be quite thin: 2-3 inches. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Markus; Your question touches on several separate topics; not being knowledgeable concerning American ships I cannot perhaps answer with full authority, but I can tell you the equivalent English practice. Firstly, all timber used in ship-building was classified in various categories, according to its size and intended use. For planking, this comprised 'board', 'plank' & 'thick stuff'. Board was around 1" thick, and was used for bulkheads and partitions. Plank was up to 4 or 5" thick, and was used for most of the hull covering, in and out. Thick stuff was used where extra strength was needed, and was up to around 9" thick. Generally, anything over this thickness was only used (in larger ships) for the keel and related pieces, along with deck beams. Compass timber was anything curved, the main use of which was for forming the curves of the frames. The thicker strakes of deck planking, which are flush with the main deck coverings, but are let down into the top of the deck beams, are known as 'binding strakes', and their purpose was to stiffen the ship's structure. They were also often used to fix the ring-bolts for the train-tackles for the ordnance. Lord's survey is obviously a very thorough one, and much attention has been paid to detail. I would be very dubious that he shows anything that was not there when he carried out his work. In the 17th century, the central portion of the deck was normally raised above the planking outside this strip, and was delineated by timbers known as 'long carlings'. See photograph below from a model of the 'Boyne'. This practice continued in the 18th century; see photograph of a model in the National Maritime Museum, dating from the early 1760s. Thanks for posting an interesting drawing. All the best, Mark P

-

As a piece of interesting trivia, the earlier name for these items was 'dead men eyes'. This was especially apt when they were triangualar rather than round, making the resemblance to a skull face more obvious. All the best, Mark P

-

Help with understanding the rigging diagram

Mark P replied to Linda DOBLE's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Good Morning Linda; To help you understand what is happening in the rigging diagrams you show, a simple rule can be applied: The mast and sails on the left show the 'sheets'. All sails shown on the mast need a rope to keep their lower corners from flying up in the air, in which event the sail would hold no wind, and the ship would not move. The sheet performs this function, and is essentially the same on all the sails shown. The right hand mast and sails show the ropes which are designed to do the exact opposite to the sheet, and to raise the lower corner of the sails to the yard when it is time to furl the sail. These are known as 'clew-lines'. To haul on the sheet opens the sail; to haul on the clew-line furls the sail. When the sheet is hauled, the clew-line must be 'paid-out', or slackened so that it runs free. By far the best reference book I know of for ships of this era, which covers the rigging of such ships in great detail, is the 'Masting and Rigging of Clipper Ships and Ocean Carriers', by Harold A Underhill; first published in 1946. He was a very skilled modeller and draughtsman, and knew many of these ships personally. He also wrote several other books dealing with simiilar vessels, and produced a wide range of plans for such ships, which have very good masting and rigging details on them. If you are building your model without sails, then the ends of the clew-line and the sheet would be shackled or tied together, so as to be ready in position when time came to fit the sail back to the yard. (edit) I have just checked and the book is available online from £16, with many copies listed by different sellers, with different qualities and prices. Wishing you all success with your modellling! Mark P -

To be fair to Mike he does say he is not sure if those two are in the Rogers Collection or not. Vol III covers fourth to sixth rates. Presumably the brig is unrated, and so is too small to fall into this category; and must wait for the next volume, along with any single masted vessels. However, as a frigate one would expect that the Shannon would be in vol III if it was part of the Collection; something I know not. Unless it is intended to produce a separate volume of American vessels? All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Mike; Thank you for posting your reply. If it is the spam filters, yes please, sort them out, as customer communications are a vital interface for us all. However, regrettably, this still does not answer my original query: Will it be possible to order a copy of the Rogers Collection Vol III? Which is marked up on the website as sold out. Is this an error? Or if it is correct (in which event I am very surprised not to have received any notification of the book being available for pre-order) will you be increasing the print run? I would really like to order a copy of this book, as well as the Fubbs volume, and my query being continually left unanswered is rather frustrating. All the best, Mark P

-

Thanks Mike; I did indeed read along with the topic you link to, whenever there was a new contribution. It seemed best to post this under a new topic, though. I would expect that if there is any problem, that someone somewhere, closer to SeaWatch than most of us are, would know of it and post an update to keep potential clients informed, as was the case with both Jim Byrnes' business, and SeaWatch itself under the previous owners. There are two books listed as forthcoming, one of which has already sold out, seemingly. So it seems that things are ticking over as usual. Maybe there are difficulties behind the scenes; but my main gripe is that a business which does not respond to two separate emails for a period of over a month in total, needs to do a lot better; that is unarguable; and the doing better category would include letting people know if there is a reason for such delays. All the best, Mark P

-

I don't know what's happening over at Seawatch Books, but I have twice sent them a message via their contact us page, and on neither occasion have they deigned to answer my query. I looked through their catalogue in December, and saw that vol III of the Rogers Collection was now available, but that it had sold out. I therefore sent a message asking if they had any plans to increase the print run to allow for later orders, and to have a number in stock. I don't know who's monitoring their incoming messages, but they need a large rocket up their backsides, especially if other's messages are eliciting no more response than mine have. On top of being rather upset that I had received no notification of this latest volume being available, despite being on their mailing list, to then have my valid queries completely ignored is adding insult to injury. Just to assist, I will advise you of the three possible answers, none of which take long to write: 1) Yes 2) No 3) We are considering this WHERE ARE YOU!!!???? Mark P

-

Good Morning All; The main point when discussing any possible set of plans for a model of a ship from this period is that there is no 'true' draught, or picture, of any vessel which can be used as a reliable basis for a reconstruction. Any draughts wich exist are modern, or relatively modern. If we are lucky we know the length of the keel, the greatest breadth, and the depth in hold. Using these, and following known conventions and methods of the times, it is possible to make a reasonable reconstruction. Lengths of masts and yards are available to anyone who knows where to look, and it is even possible to know something of the decorative works applied to some ships. However, these measurements are only recorded for warships, and there is often some variation between various sources. But overall, the information is far less than that which is required to be certain that any draught drawn is a true representation. Accept this, draw a draught if you can, or use the one available in Peter Kirsch's excellent book, which is probably as near to the truth as it is possible to get, and make the best quality of model which one can. Or use a draught from a reputable kit/plan supplier which is at least based on some level of research (if it is possible to find this out; other members here may know more in this respect) Opinions of the finished result's verisimilitude may vary, but if you have done the best possible, using the avaiable resources, no-one can say that it is not a true likeness, as there is no comparator to set it against. Contemporary engravings look like caricatures, or cartoons. Certainty is unachievable. Enjoy the research, enjoy the build process, and admire the finished model, with the words we all know in your head: 'I wish I had done that/those bits a little better', and use the lessons learned in your next model. All the best, Mark P

-

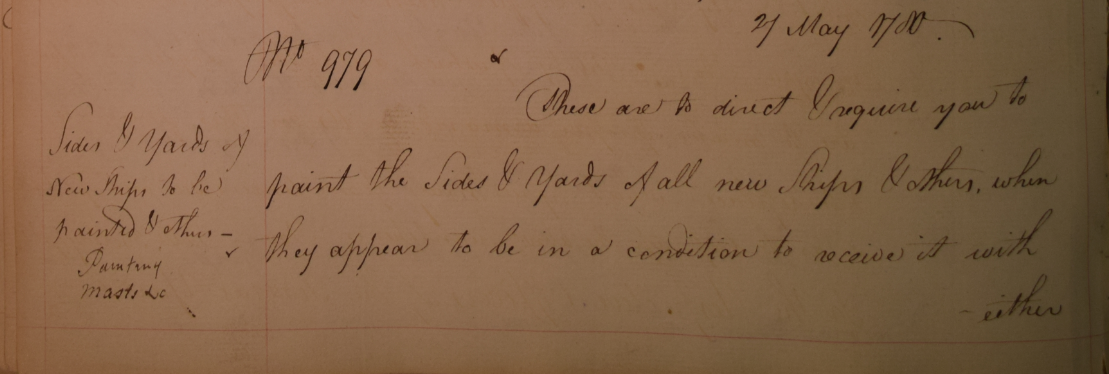

Good Morning Michael; Upon further digging in my files, I have found the following Navy Board order, dated 27th May 1780, which orders that the sides of ships are to be painted with either black or yellow, as the commander desires. All the best, Mark P

-

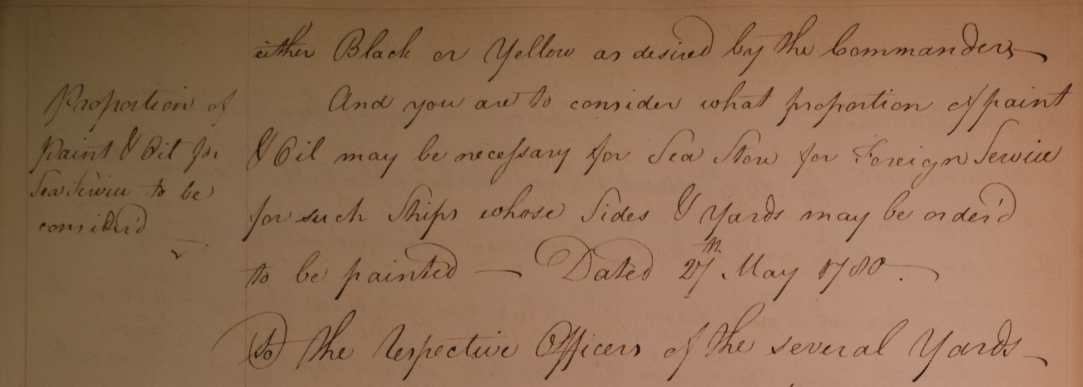

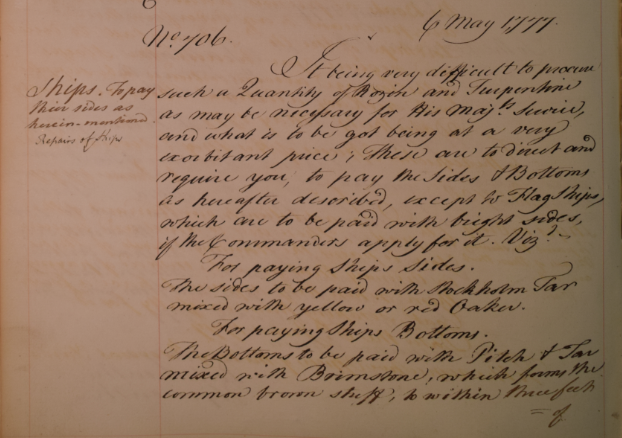

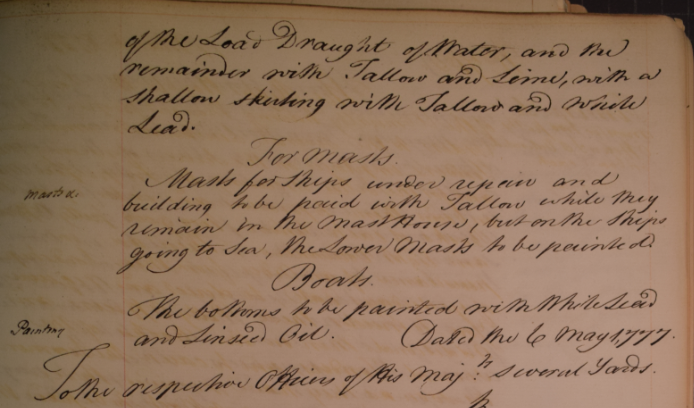

Good Morning Michael; By a Navy Board order of 6th May 1777, ships' sides were to be 'paid' with Stockholm Tar mixed with yellow or red ochre; except flagships which could be painted with bright colours at the Commander's request. This was due to the difficulty in obtaining sufficient quantity, and high price, of supplies of Rozin and Turpentine. The same order directs that the bottoms of ships are to be paid with Pitch & Tar mixed with Brimstone, which makes the common brown stuff, to within nine feet of the load draught of water, and the remainder with Tallow and Lime, with a shallow skirting with Tallow and White Lead [this presumably meant that the 'brown stuff' was normally invisible below the water] The same order directs that masts removed from ships under repair, or those ready to be placed in new-built ships, all of them whilst in storage in the mast house, are to be treated with Tallow. Whereas for ships going to sea, the lower masts are to be painted [unfortunately no colour is stipulated here] These orders probably remained in place until Nelson's time, when his preferred mode of yellow with black stripes and chequered gun-ports became copied through squadrons, and then fleets (although recent analysis of paint remnants on the Victory has led to claims of her being some shade of red/pink I believe) All the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Dave; Contracts from the period stipulate the following for the cook room: I have added the words in square brackets for clarity. 'To lead [meaning the metal sheet material] and lay cants for the fireplace, to line the underside of the deck & forecastle beams [meaning the ceiling overhead] with lead & double tin plates all round within the compass of the heat of the fire, to cover the upper deck [within the area outlined by the cants] with lead 7lb to the foot square & to put up such convenient dressers and lockers as shall be necessary. Cants are timbers laid flat on the deck to create a kerb, or upstand, around the area of the cook room. All the best, Mark

-

Good Morning Allan; The essential difference between 'white stuff' & 'black' was the cost. The ingredients of the black variant were cheaper, and its use was apparently widespread. However, the white was considered more efficacious, and was used for ships designated to serve in warmer, tropical seas, where the risk of worm attack was higher, and presumably fouling was worse due to longer time out of the dockyard before the ship could be graved again. However, as a black-coloured hull is not as attractive to look at as a white one, artists and modelmakers invariably use white to colour this part of the ships they depict. Artistic licence is the deciding factor in what we see, not a strict adherence to reality; understandably so, I would say. All the best, Mark P

-

And everybody here will appreciate your doing so, I assure you. Theft of another's work undermines the whole ethos behind developing a kit in the first place. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Allan; This is an excellent book. It is based on the author's reconstruction of a galleon using the 'Salisbury Treatise', which is an early 17th century work on designing ships. This is a detailed treatise, and is in some places hard to understand (it does not help that some of the sentences here and there were lost in copying) I believe that there are one or two errors in Mr Kirsch's reconstruction (I cannot remember who told me this, it was some time back) but overall it is certainly a good buy. He uses a surviving votive model from Denmark, I believe it was, as a general guide to what he is trying to achieve. However, the treatise is written in English, presumably by an Englishman (the original has not survived, which was certainly larger than what we now have, with tables, now lost, included) and to the best of my memory, it can only be assumed to refer to English practice. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Allan; This kind of detail is quite common on draughts of the later 18th century, certainly. I have always been of the opinion that such things represent the joining of beams by scarphs, seen from the end, and cannot conceive of it representing anything else. The location and spacing make it certain. The use of scarphs was not so much dependent upon the whim of the shipwright in charge, but rather was driven by the timber available. As good timber became harder and harder to obtain, it became necessary to use ever shorter pieces. I have read of deck beams being formed of two, three, or even four separate sections, all scarphed together. The scantlings of timbers used in early 17th century ships, which were much smaller than those of the later 18th century, are much larger in size than the corresponding timbers ever were in the later period. This presumably reflects the need to make the most of the timber available. Deck planks were both spiked (nailed) and treenayled at various times. Generally the butt end of a plank would be fixed with a bolt for extra security, or if a wider plank, with a bolt and a treenail, if my memory serves me correctly. All the best, Mark P

-

Congratulations Jerry, on a real working model which is a reflection of both the real vessel, and also your many hours of dedication and effort to bring her to life in miniature. Great model, well done indeed! All the best, Mark P

- 74 replies

-

- pride of baltimore

- privateer

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Good Morning Everyone; Some interesting thoughts are being added to this debate. However, although some are correct, and some somewhat less so, nobody has yet stated the truth regarding the reasons for adding wales to a ship. They were structural members, yes, and important ones; and they evolved over time from a number of single, relatively parallel strakes of timber into broader bands made up of several strakes together. However, the main intention and function of wales was to counteract 'hogging', also called 'reaching'. This was the perennial problem of timber construction, wherein as a wave passes under a ship from end to end, the stern and bow in succession are left unsupported, and tend to droop. Over time, this led to the butt joints of the planking opening up, and to the keel becoming curved downward at each end. Warships were especially prone to this, due to the weight of the ordnance carried at bow and stern. The wales were separate strakes of heavier timbers, inserted in the planking, running parallel to the external planks. Although not always specified, they were often bolted to the timbers, not treenailed, for additional strength (remember that iron bolts were expensive, and were not used lightly) In order to achieve the maximum benefit of this method of strengthening, the curvature of the wales was exaggerated relative to the sheer of the deck, so that the ends of the wales were higher relative to the line of the deck, than was the case amidships. The main wales were always sited so that they gave strength to the main deck, being in line with it at the midships, and above it at the bow and stern. As Druxey states above the decks were, in earlier times, stepped downwards at the end, in order to avoid the need to cut gunports through the wales, thereby weakening them. However, it was realised that this significantly weakened the resistance of the deck planking to hogging, and it was already recommended in England that steps should be avoided, by 1612. The internal planking, though, did follow the sheer of the decks. The essential principle of internal planking was that at every location where there was a line of overlap in the ship's timbers, between floor timbers and futtocks, for example, and different ranks of futtocks, this overlap was strengthened with a much thicker band of planking, in many locations, and with quite a variety of names: for example, what in later times was known as 'spirketting', that is the run of thick timbers between the waterways and the gunport cills, was originally known as the 'spirkett wale'. This is because the spaces between the ends of the timbers were known as 'spirketts'. Others were 'sleepers'; 'middle bands'; and 'footwaling'. In later times these became known under the more generic term of 'thick stuff over the futtock heads'. In order for the wales of the model which started all this to look realistic, it is necessary that they must follow the sheer of the planking. All the best, Mark P

-

Drafting Frames

Mark P replied to tmj's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Good Evening tmj; Assuming that you are speaking of Royal Navy ships, or similar, even for experienced folk it is not really basic, unfortunately. With some exception, the inner line of the timbers at each station is a gradual taper from the thickest dimension over the keel, to the thinnest at the capping rail of the ship's side. To draw the timbers successfully, it is necessary to know the thicknesses and the points at which they were measured. This knowledge can be gained only from study, of either contemporary or modern books, or the sources on which they are based. Allan Yedlinsky's book 'Scantlings of the Royal Navy', gives a good start in this field, but it will not be a quick learning process. You will need either a level of dedication bordering on the masochistic, or a very determined interest in mastering the particulars. However, once grasped, the principles will remain with you, and the only additions are the particular dimensions for each size or type of ship. It is a rewarding study. Did I say anything about the additionally necessary knowledge of the 'horizontal' timbers which tie all these stations together; which also have their own idiosyncrasies and behaviour: keel, keelson, clamps, wales, spirketting, to name the principal ones. 🙂 All the best, Mark P -

Good Evening Michael; There has been considerable discussion on this forum previously regarding whether the Sovereign had a round or square tuck, so I won't go over it all again; suffice to say that it is there to be found if you are really interested. I can say that the late and much-missed Frank Fox, widely regarded as the foremost expert of his time in 17th century ships, was firmly of the opinion that she had a round tuck stern. I wish you a successful completion of your model, with only you being aware of the small regrets! (why did I not change that when I could!) All the best, Mark P

- 99 replies

-

- Sovereign of the Seas

- Airfix

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Good Evening Georgik; An interesting query. I will do my best to give you a relevant answer, but can I ask you to clarify the connection between what seems to be an 'Italian' (or at least Mediterranean) ship (Medici; Livorno) and an English ship's cabin? If you are referring to an old model somewhere, it would be good to know about it. To answer your query I can tell you that there are, as far as is known, no woodcuts, engravings or paintings of the interior of a cabin from this date (the earliest I know of are more than 70 years later) nor have I seen any such features in the background of contemporary portraits. They are still very rare even in much later portraits (I would be very happy to be proven wrong!) However, there is a simple rule which enables a reasonable start to making a reconstruction of an English cabin at least, which probably applies to other nations at this era. That is, that the interior of the cabins used by senior officers was constructed and furnished to resemble as closely as possible the rooms of the homes in which they lived on land; so look at architecture surviving from that period. Fundamentally, the side walls would be covered with wood panelling up to the dado level, with pilasters at intervals, surmounted by a moulded cornice. The panels above the dado were normally? frequently? sometimes? made not of timber but of fabric. Bulkheads would be all timber construction, probably. The level of finishing of the decoration would depend upon the likely status of the person using it. For someone royal this would involve carving, gilding, elaborate moulded ceilings, and painted ceiling and wall panels too (or maybe tapestries, although this is not mentioned anywhere) Those of lesser status would have cabins without the wall and ceiling paintings, but still with plenty of mouldings, carving and gilding. There are some mentions of the ceiling being painted to match the sky with 'clowdes'. The completed cabin was furnished with benches, settles and tables; and beds or bedsteads (probably of rope strung over a wooden frame) This should be enough to enable you to make a good start; and the real guidance is that within the outline of what I have written above, nobody could be more specific for any individual ship of the time, so create what you feel best will fit. All the best, Mark P

-

Shot Garlands

Mark P replied to tmj's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Good Evening All; To add a further note to the thread, I came across this while reading through Sir Henry Manwayring's seaman's dictionary, dated around 1624. He specifically states that lockers were placed by the ship's sides, at every gun, for shot to be stored in. However, in a fight, the shot would be taken out, and placed in, quote: 'in a rope made like a ring which sits flat upon the deck'. The reason for this was that if an enemy shot were to hit the full locker of balls, the contents would be spread around like shrapnel and do great injury. All the best, Mark P

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.