-

Posts

5,532 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by wefalck

-

Thanks, Kurt, these are interesting insights into the operation of such tow-boats. Of course, if these flanking rudders can move, they make perfect sense, when going backward. This would be a classical application for Schottel-props, but I gather they may be too delicate for the shallow rivers full of debris. There is also a limit to the amount of HP they can bring into the water. Turnable pods with Kort-nozzles would obviate the need for all those rudders, but again debris might be a problem and the shallow draught needed. In the early 20th century for working on shallow (central and eastern) European rivers systems, where the props worked in half-tunnels were developed. Some tow-boats also used early forms of water-jet propulsion to aid maneuvering and turning in tight bends.

-

Greg, what do you mean by 'dernier line'? Dernier normally is a measure for the fineness of a thread (1 den = 1 g per 9000 metre) and was also used to classify ladies' stockings and pantyhoses. There are other systems, such as the tex. I am not a great fan of monofilament, as it tends to be relatively springy and, thus, knots tend to unravel, unless immediately secured with some varnish. Some time ago, I became aware of this high-end Japanese fishing line. It's braided, available in 'steel-gray' and down to diameters of 0.06 mm: https://fish.shimano.com/en-GB/product/line/braided/a155f00000c5ijoqa3.html. Quite pricey. I have not tried it myself, because I didn't have a need for 'wire-rope', which it might simulate quite well.

-

BTW, talking about toolmaker's buttons: I learned about them about 25 years ago, when I purchased from Lindsay Publications (now sadly defunct) a bunch of reprints of early 20th century machinist textbooks and the likes. Among these was JONES, F.D. (1915): Modern Toolmaking Methods.- 309 p., (Industrial Press, reprint 1998 by Lindsay Publications Inc., Bradley IL). Just checked on archive.org and one can now download a copy from there: https://archive.org/details/moderntoolmakingmethodsbyfranklind.jones.

-

I have a separate hard-drive for backing up everything (as I also use the computer for work) around once a month and I only remove images from the telephone, once I have copies on two independent devices ... I was wondering about these rudders in front of the Kort-nozzles: do they move? If not, the boat would be quite sluggish to turn, I could imagine. And: oh, yes, the project is coming on nicely !

-

OUTSTANDING Mini Drill

wefalck replied to Bill Jackson's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

That's a bit of thread drift now, but for really delicate work I use a watchmakers archimedean drill that requires both hands, as it does not have a return spring. I can precisely control the pressure needed/permissible (with tiny drills). Of course, the workpiece has to be fixed (some 'cello-type' suffices often), but this is good practice anyway. Mine can clamp drills down to 0.1 mm diameter. -

Talking about other people's projects: there is German colleague, I just remembered, who build a Viking-ship (the HAVHINGSTEN after one of the replicas after the Roskilde finds) in 1:25 scale and he had a whole boatload of 'Vikings' (or what he declared to be such). Not sure, whether you can see this without registering: https://www.segelschiffsmodellbau.com/t6718f20-Havhingsten-fra-Glendalough-21.html. He did a really good job in painting those figures.

-

Well, the sleeves around the smoke stacks are not just 'decorative': in order ensure sufficient draft, the smoke-stacks have to long, but then would cool down quickly. The sleeve isolates the actual smoke-stack, so that it stays hot. As even the sleeves become quite hot and old-time oil paints did not take the heat very well, ship company logos were painted onto an outer sleeve, some distance from the the sleeve that housed-in the smoke-stacks. Normally, the engine-exhausts are led into a condenser to improve fuel-economy. Some ships may have had the possibility to redirect the exhausts temporarily into the smoke-stack to increase draft (as is done on railway locomotives), but more commonly fans were used. The pipes placed behind or in front of the smoke-stacks are normally the exhausts for the safety-valves. Talking about pilot-houses open to the back: over here in Europe, when the pilot-house began to be enclosed, crews on some ships complained, because previously they got warmth from the radiating smoke-stacks, but now they were cold in the enclosed, but unheated pilot-houses ...

-

Can't respond on possible figurines. There may be something in 1/24 that could be converted with some effort. As to any goods, this would depend from where to where the ship was sailing and in what mission: trade or loot (I gather the border between the two might have been a bit muddled at times ...) Right up to the 19th century, perishable goods and those, where humidity either had to be kept in (say pickled fish, beer, wine, etc.) or out (metal ware, dried fish, cereals/flour, etc.) where stored in closed barrels, the containers of the time. A typical good of a ship sailing to Island or Greenland would have been wood, pitch and all sorts of provisions. Ships sailing from the Eastern Baltic would have carried inter alia pine-tar, pitch, wood, hemp etc. There were some major trade-hubs, such as Haithabu and Birka, where everything from agricultural produce, metal ware, luxury goods to slaves were traded.

-

Actually, in the physical archive there are two resources, the books that list the ships by name and then the folders with the drawings in the vaults. These books are a great resource, because they list all the archive numbers that belong to one particular ship, which allows you to collect all the drawings pertaining to this ship. I have physically worked though some of those books in the Rigsarkivet in Copenhagen some 25+ years ago. Then you wrote down the number for the staff and they would bring you the folder an hour later or so. These books now have also been digitised. In consequence, there are two ways of working with the material, you can either look up the drawings for a particular ship you are interested in, or you can go to the group of drawings that show particular details, e.g. anchors or ship's stoves etc.

-

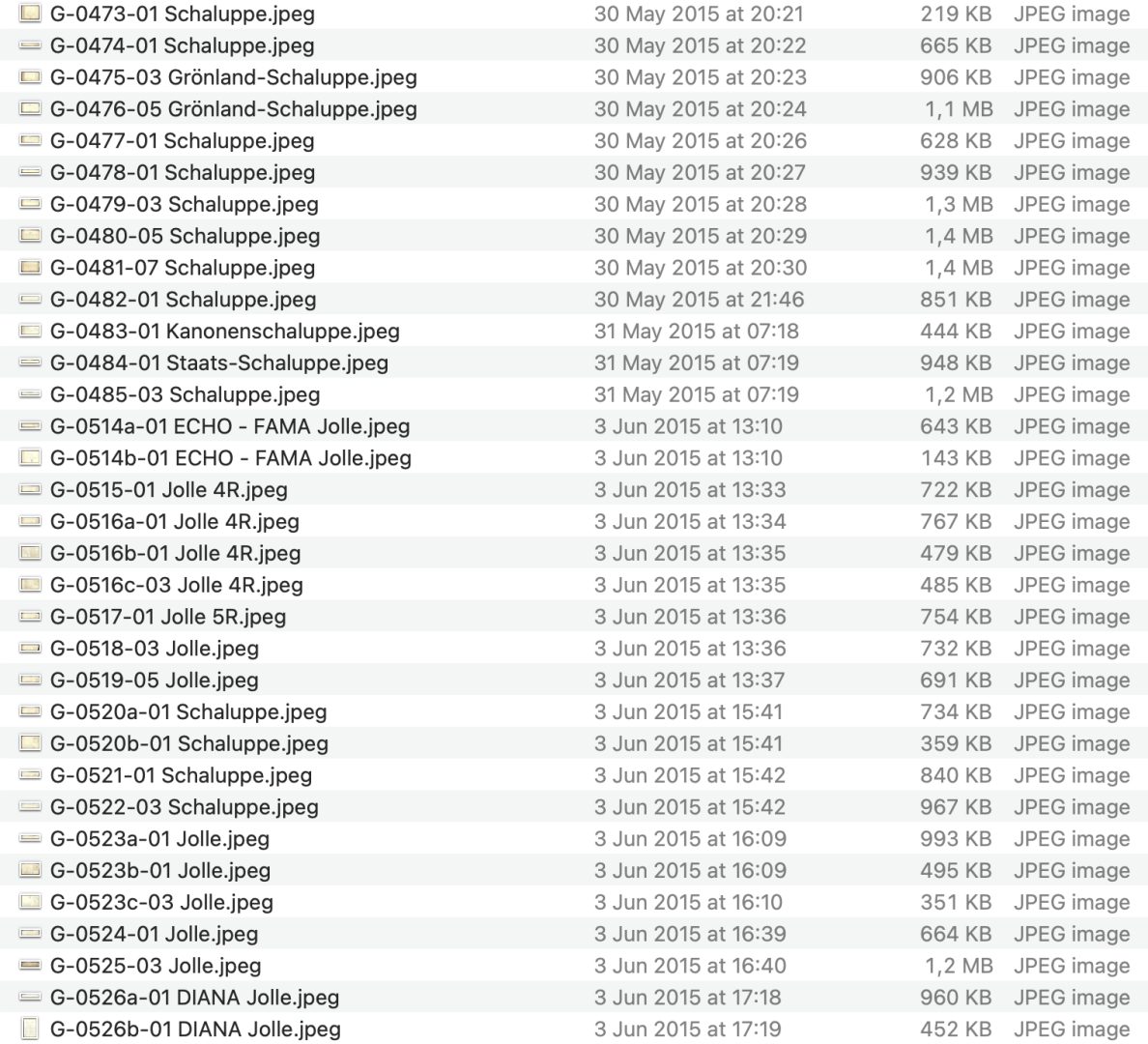

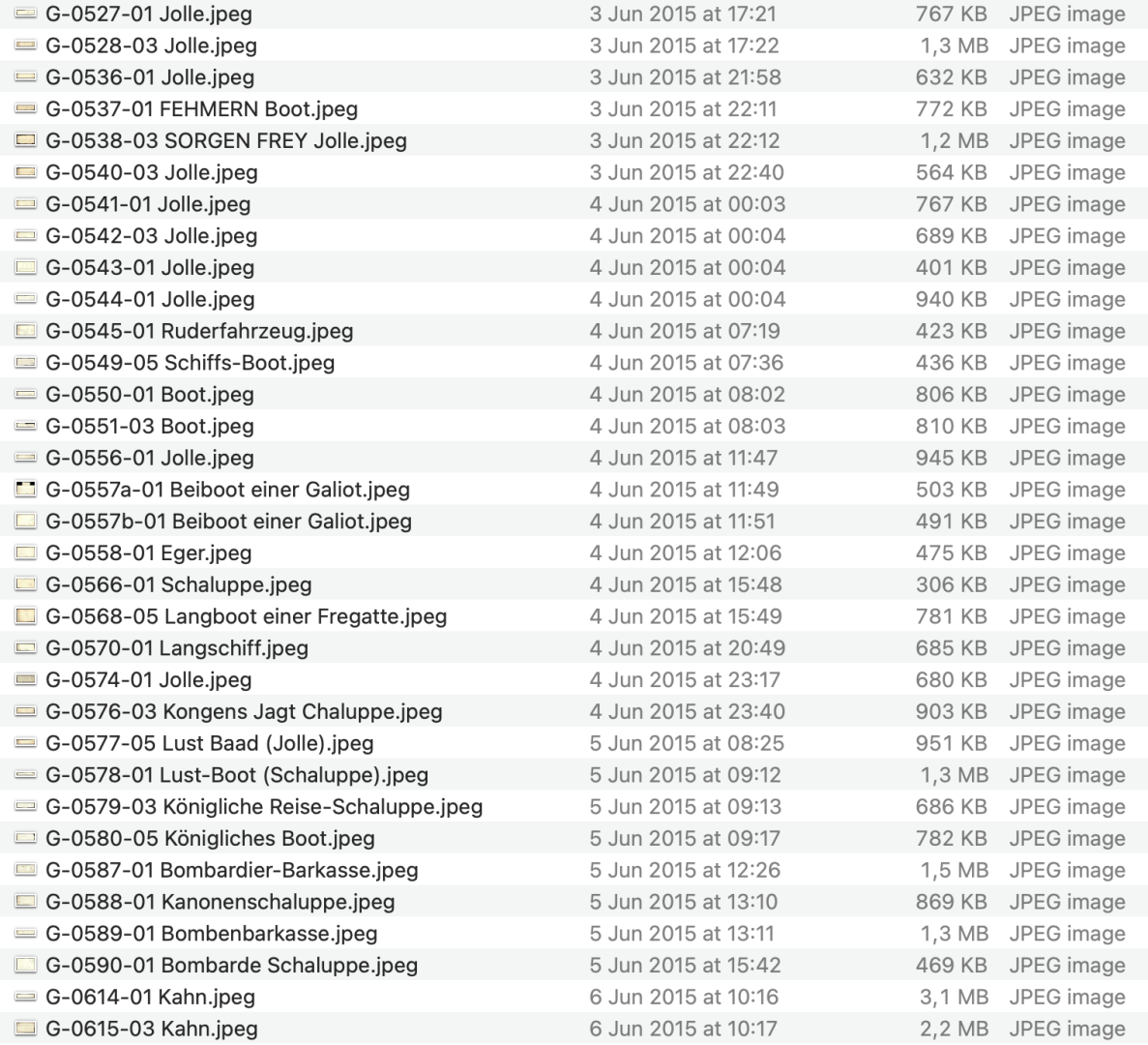

Alllan, unfortunately, there is no easy way to navigate around the site, which is structured exactly as the physical archive is. However, in general terms the archive is structured by subjects, but this doesn't mean necessarily that particularly drawing do not pop up elswehere. Historically, there might have been a logic for this, but this is lost now. A colleague and myself have actually gone through the pains some ten years ago to download the whole archive (I think they have added to it since, but I didn't have time to check ...). So, I have a fairly good overview over what is where. Below is a list under which numbers boats before ca. 1820 (this is an arbitrary date chosen according to my interests) can be found (sorry this is not 'clickable', I had to take screen-shots - and the description is German): Unfortunately, in the navigationsystem for the archive there are no 'thumbnails', so one really has to go through each archive number. I quickly clicked through the previews on my computer and have the impression that in many cases, give the large number of stations drawn, that these correspond to frames. The date of the drawing, or rather of its approval, can be usually found under the legend to the right, but not all drawings are dated.

-

I can only speak about German naval boats, but I think it would be more or less the same for all navies: The bow-oars were indeed shorter than the others, as the boat would be much narrower at the first bench. Some 30 years ago a colleague of mine, who unfortunately died prematurely a couple of years ago, wrote a series of articles on the naval oars of the Imperial German Navy that summarise the knowledge pulled together from various books, naval instruction manuals etc. that are difficult to put your hands on. Although, I do have some of these sources, these articles were extremely helpful, when I worked on my current project. He gives as a rule of thumb the following dimensions/proportions: Length = 3 times largest breadth of the boat, 2/3 outside, 1/3 inside the boat. Max diameter = 0.017 times the length at 1/3 of the length Handle = 0.8 times the larges diameter and about a foot long Length of the blade = 0.27 to 0.3 of the total length of the oar Max breadth of the blade = 1.5 times the max. diameter. Min. thickness of the blade = 0.16 times the max. diameter, at the end. In fact, there are tables with detailed dimensions for all the oars of the Imperial Navy, which were standardised to nine different sizes and matched to the different boat types, which were provided in different size classes. In fact, there were some 20 different boat types in the navy.

-

I think the original question was, what the distance between the frames would be, correct. And I seem to infer that the question concerns 18th century ship's boats? Have you had a look at the images from the Danish archives? There are some very detailed drawings, if I remember correctly, that even show individual frames etc. and not just the stations. For the 19th century, were are better informed, as there are various textbooks from different countries, that have plan views or longitudinal sections of naval boats with all the interior details. There are also few surviving boats that give an idea. At that time most bent frames were used.

-

Sorry, I indeed missed the point with the carpenters' glue. So once trimmed to shape, you lift off the assembly, apply the glue and put it back, right?

- 253 replies

-

I quite like the look of the 'painted canvas' decks. My concern, however, would be how long it stays attached to the decks. These masking tapes are designed to be not too tacky and I know that ordinary painters' masking tape becomes quite brittle with time. Good luck with your lecture and make sure that the audience watches with their eyes and not their fingers 😉

- 253 replies

-

I was about to suggest to use a home-made scraper with a half-round profile, made from a piece of razor-blade to shape the shafts of the oars. You can cut the profile into an ordinary razor-blade with a diamond burr. Brake off the piece with pliers. This scraper can be held in a pin-vice that is slotted cross-wise. I have used such purpose-made scrapers for shaping very small profiles etc.

-

Indeed, jewellers' drawplates are not suitable for reducing wood in size. I think we had this discussion already in some thread here. The anatomy of an oar depends on it's use and the period. Sea-oars are rather different from the oars that are used on inland waterways. Basically, sea-oars are symmetrical, so that one can use them forward and backward. Also the diameter is round for much of the length. Likewise, the blade is quite narrow. The diameter is, of course, proportionate to the length. The length depends on the breadth of the boat and whether it is single- or double-banked. For single-banked boats the length would be about three- to four-times the breadth. In 1/128 scale I think it would be not so easy to make the blade and the shaft in two pieces. You would need to slot the shaft for the blade and this could be a challenge for a shaft only somewhere, say, 0.6 to 0.8 mm in diameter. I would start from a flat piece of wood (or styrene), layout the shape, cut out the shape, and then shape the shaft and blade by scraping and sanding. My 1/160 scale oars where made from layer of paper blanks cut out with the laser-cutter and laminated together using varnish. They were further shaped using diamond files.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.