Carlos Reira

Members-

Posts

33 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Carlos Reira

-

For me it's upgrade from Dremel to a decent flex shaft tool.

-

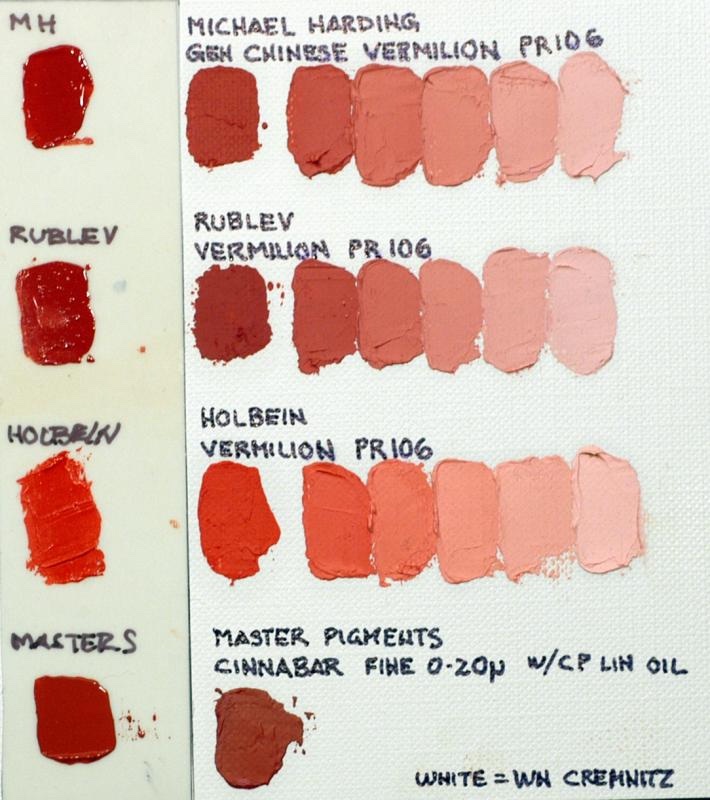

Assuming that the bulwarks were painted a pure red, not an earth red, I believe there was only one choice in the eighteenth century--vermilion, a toxic pigment of mercuric sulfide ground from the mineral cinnabar. This would have been an exceptionally expensive option and I'm certainly not qualified to say if this was the actual practice. But everyone seems to be doing it, so I thought it would be good to show what vermilion looks like. It varies a lot, but is usually to the warm end of the spectrum, but can also be cool. It's a very opaque pigment. I think it has the highest refractive index of any known pigment, so it was opaque as paint could be. But if you need opacity you can always use more coats. The closest modern equivalent is cadmium red light or medium.

- 607 replies

-

- winchelsea

- syren ship model

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Mahogany veneer is somewhat prone to splitting, even the real deal mahogany, Swietenia sp. And there's the open pore structure which is heavy on even quarter sliced veneer. As someone above said, cherry would be easier to deal with in something like a model. Mahogany is a great solid wood for a million things, carves great, pretty strong, doesn't react to humidity much. But unless you're using some antique Cuban mahogany (the only true true mahogany) veneer or crotches or something, I feel like there's better woods. Sapele is even more meh. Once you've seen it up close, you'll know what I mean. They all have their uses. Mostly, the reason all this African lumber gets made into veneer is that the trees are huge and knot free, easy to capitalize into a commodity worth dragging out of the dark continent. Like everywhere, they'll soon be putting embargoes on their diminishing forest products. Remember all that "ramin" wood furniture that was ubiquitous for a few decades. Not any more, it's endangered. A lot of dowels in kits etc. were ramin. It was a very strong wood, about as strong as hickory. Khaya sp. called African mahogany, can yield some amazing veneers, often better than Honduras aka genuine mahogany. Veneer is actually a very cost effective way to process trees as there is no kerf waste and huge amounts of surface area are created. But after a while, especially in large expanses and under a gleaming finish coat, it starts looking like formica.

-

One of the best purposes for modern composites is jigs, fixtures, and shop built machines. Some Trex type flooring, not Trex brand though, which is kinda meh, is so slippery that it works for linear bearings. The outdoor decking products are mostly polyethylene, so no way to glue them. None of the plastic lumber types have stiffness values anywhere near wood, which is why they're so flexible. PVC lumber can be bent into very tight curves. It glues with PVC plumbing cement. PVC plumbing pipe for that matter is great for making all kinds of parts. It can be heat flattened and machined with normal woodworking tools. It's available for free everywhere as trash. For interior flooring, many products are available that have woodworking application. Cali Bamboo flooring, a resin impregnated bamboo product, is so hard and dense that it can substitute for metal parts in certain machine applications such as pulley sheaves, much like lignum vitae was used historically. Wherever precise flatness or thickness, dimensional stability, hardness, wear resistance, machinability, glue resistance etc. are involved, modern materials excel. But as a substitute for solid wood I don't think much of them.

-

Yes, small pieces of almost any North American wood, actually anything about 1 1/2" thick will dry in a year indoors, in the house that has heat on over the winter, not a shed. The relative humidity in winter in most homes with central heating is basically the same as a wood kiln. It can actually dry too fast, but so much depends on the species. Of the three species you mentioned, cherry is the trickiest. I think if it's cut in the growing season it has too much moisture and cracks fast. Hickory can be like that too, but not Pecan for some reason. Walnut is not a problem to air dry, even in massive thicknesses. That's my experience. The most important thing is to get rid of all bark and inner bark, that's where the bug eggs are, and coat the end grain with many coats of paint, glossier is better, 3 coats is minimum for big pieces, or a couple coats of wood glue. The emulsified wax that they sell for this purpose is good, but not more effective than wood glue. It's just soft and clear so the grain can be seen and tools aren't blunted. The advantage of glue and latex paint is that it will be carried into cracks by capillary action and hold them shut. Oil base paint is actually better for preventing moisture transmission but doesn't have the same capillary-gluing effect. If you've got short precious pieces with end checking, such as you often get from "firewood." you can stand them in a pan of wood glue diluted with methyl alcohol (blue wiper fluid). Capillary action will suck up the liquid and close the cracks, sometimes a few clamps will help close a crack. This works well with cherry. No amount of end coating can overcome the cracking of a round log as it dries. It does work for half logs. An unheated attic is a great place for drying and storing lumber if you have one. The temp will get high enough in the summer to keep vermin and fungus at bay, and the relative humidity will be very good year round. The year per inch thickness rule is for air drying stacks of milled hardwood lumber outdoors. Covered and stickered flat is how they do it. In olden times wood was air dried vertically and allowed to warp or split as it pleased, doesn't even need to be covered because the rain will drip down the sides and not soak the wood too much. Defects were worked around, and crooks were used for furniture parts. Construction lumber was used green.

-

This probably belongs in the tool category, but to cut that Lauan plywood and for many other tasks, a jeweler's fret saw is indispensable. They're like a super fine toothed coping saw, but the blades don't rotate, so you're limited by throat depth. They're used with a simple block of wood sticking off the bench called a "bird's mouth" to support the workpiece. The blades are cheap and come in many varieties, even spiral toothed. They'll cut metal too, brass, even mild steel. The pictures show the variety and huge difference in price that you can get. Anywhere from $10 to a hundred plus for the "Knew" tools line of super rigid precision milled aluminum stuff. The first picture shows their unique powered design. ($2k+!) It's advantage over the usual scroll saws is that it moves straight up and down and with a much longer, slower stroke. Great for mother of pearl artisans, jewelers, and model makers. In general, when working with Lauan aka Philippine mahogany plywood, score the face veneer with a sharp knife, and then saw to the outside of your score line. It's a good strong material, but really splintery. It's not as common as it used to be. I believe the Shorea species are now endangered.

-

Pinus strobus, Eastern white pine, is very common tree, a legendary wood with much history. It was the preferred mast and spar species for the British admiralty once it was discovered in New England. Everyone knows about the King's pines. If slow growth, it carves pretty well in the round, but not for really small things. It was used for figureheads and stern board carvings on actual ships. If fast growth the end grain is difficult to cut without crushing and the difference between the soft early wood and the hard latewood is prominent as in most pines. Western white pine, Pinus monticola, is also excellent, and usually found in lumberyards in 1x boards. Sugar pine, Pinus lambertiana, one of the world's biggest trees is another Western soft pine, and I believe the preferred pattern making material when there was such an industry, as Roger said. For ship model purposes, if you live around white pines, go for the limb wood after a storm. The tight grain is really good for carving. You'll get a soft half and a harder half, not sure which is top or bottom, but the wood grows that way to support the limb. Another quality of white pine is that all branching occurs around one nodal region, and the wood in between is perfectly clear. Sometimes the heartwood is much harder. It's the preferred part, as it's rot resistant and ages to the famous "pumpkin pine" color, but you need big old pines to get heartwood.

-

The North American wood marketed as "cherry" is Prunus serotina, black cherry, a not fruiting species. Well actually it does bear very small fruit, but it's not the same as the sweet cherry, Prunus avium and the sour cherry, Prunus cerasus, both old world varieties from which the fruiting cultivars have been derived. The wood of black cherry is more reddish but the texture probably similar to the European cherry. American black cherry trees also can grow to very large size, yielding top grade lumber, similar to black walnut in that regard. Large cherry trees are more rare than large walnut trees due to the fact that they like to grow at the edge of the woods and along fence rows etc. Walnut trees grow sometimes in pure stands and release juglone, a chemical that makes many competitors die off.

-

I second Jaager on Bradford pear aka Callery pear, a very commonly planted non-fruiting ornamental. It's a true pear, Pyrus sp. and the wood is nearly indistinguishable from true pearwood, in some ways better, much less knotty and twisty. It's disadvantages would be wide growth rings and sometimes curly grain, usually a plus for woodworkers. The limb wood is outstanding. They grow very vertically so there's no reaction wood to them. The grain is tighter. It carves amazingly. Dries easily without degrading. Can be subject to worm damage, so best to remove all bark early on. But the best wood all around for ship modeling would probably be apple. It's slightly harder than cherry, carves better, and doesn't show as much ray fleck on quartered surfaces. It's tan to brown, and oxides to a amazing color. Think of an old North American handsaw handle. They were usually apple wood. Disadvantages are: different heart wood and sapwood color, apple trees are not known for straightness and worms love it. It's also sort of hard to dry, but so is black cherry. They will check rapidly if left out in the sun. Most anything ship model wise could be made from apple, except maybe the smallest details where boxwood would be the choice. Even very small boxwood twigs can be used for turned stanchions, blocks, stern details, figureheads etc. Another advantage of apple would be the numerous bends and crazy branch structure can yield just the right shapes for knees and other parts of the ship that were historically made from such crooked lumber.

-

Boxwood is the same as the shrubs and hedgerows and topiaries and all that. It's not uncommon here in the US but I think of the UK as swimming in boxwood. I can smell it from here. It takes lifetimes for boxwood to attain any size suitable for "lumber." It once had numerous uses, of which Admiralty models was one. Anything that required hardness and precision could benefit from being made of box. Fine tools etc. Molds for butter, for decorative plaster or wax elements. In medieval and Renaissance times, amazing miniature carvings were made from boxwood. It can hold detail as well as ivory. It's prized for netsuke, Japanese novelty pocket carvings. Early postage stamps were engraved on boxwood end grain. This practice was developed by Thomas Bewick and eventually became the go-to method for mass media printed illustrations, the famous Victorian line-art images that advertised everything from undergarments to machinery. It could hold up to thousands of imprints without degrading.

-

Yeah, there's no way that's Spanish cedar (cedrela odorata) which is the wood that cigar humidors use. So if it looks and smells like a cigar box, it's cedrela, a Latin American hardwood which isn't a true cedar. But...could be some really nice American wood like Atlantic white cedar, a legendary boat building wood. More likely Northern white cedar. If it looks like the shims that they sell, you know the bundles that are really low grade rood shingles. Those are Northern white from Canada. Very nice, light weight wood. Won't bend worth a crap though.

-

They're related, same genus Tilia, but not the same. To say they are is misleading. The eminent European limewood has a history of being used for amazing carvings. Artists like Tilman Riemenschneider in the Gothic period and Grinling Gibbons in the Baroque did things with limewood that would be nearly impossible to do in American basswood. Basswood is no slouch, it being the wood used by most American carousel carvers, but the hardness and workability of limewood is superior, especially in smaller scale. They are both called "linden" sometimes but they are no more the same than butternut is walnut. There are at least two species of European lime, the small-leaved lime and the large-leaved lime, and it's possible one of them is better than the others. The Midwest company has done an amazing PR job for American basswood lumber. It was not much used historically.

-

It's hard to get truly white holly. The one seller on eBay who has it charges a fortune and I think uses a vacuum dehumidification kiln. The commenter who said cut in the winter is right. But all lumber should be cut in the winter if possible. Sometimes the blue stain will only be on the surface and the inside will be white. The conditions have to be right for the fungus to flourish, temperature, moisture and oxygen. But I'm not sure if holly discoloration is the same thing a what they call blue stain in softwood lumber.

-

I've ripped mountains of lumber with chainsaws of various sizes, but my favorite is my Makita electric. Two stroke works great, but if you have neighbors electric is the way to go. There is kerf loss, but usually the whole log is a loss. Eventually enough shavings build up and you can rip the log on the shavings without worrying about hitting dirt. Usually I split the log in half down the middle, or into quarters or sometimes sixths. I don't try to get boards though it's possible. If there's a bow in the log, I always cut exactly in line with it, otherwise the will bow again while drying. Crooked wood is better than bowed for me. That is, C shaped on the face with the edge straight. Normal saw chain works fine for ripping, but you want to keep the blade somewhat in line with the length of the log to get good long shavings, exactly like rip cutting with a hand saw. Don't try ripping like the chainsaw mill guys do. That takes huge horsepower and special rip chain. The chainsaw doesn't want to dig into end grain any more than any other edge tool. You can snap a chalk line right on the bark if it's clean. Sight down the blade and with practice you'll get very straight cuts. There's a Russian guy on YouTube demonstrating this technique on fairly large logs. Bob is right about splitting, but some woods split readily green and some take enormous force to split. Everything splits with enough of a wedge, even crotches, but obviously straight grain wood is best for splitting. Sawing a kerf helps to get the wedges started, and a circular saw works for this as long as the round end of the log is flat and safe to use one. Use multiple wedges, because one is bound to get stuck. Even plastic or wood wedges help.

-

You can sticker it with popsicle sticks or something like that, but you'll still need to bind it with string, weight it down or something like that. And keep an eye on it. The hydraulic forces in wood are amazingly strong. If they're cupped, the convex side is the higher moisture side, so put two boards concave to concave side and clamp them with spring clamps all around. When they warp the other way, switch the boards, and keep doing this until they're good and equalized. If you need to moisten the concave sides first.

-

For working the wood, sometimes green (full moisture content) is best. Green hickory can be carved like cheese, and Tilia sp. (Linden, Limewood, Basswood) would work beautifully green. But for longterm stability, preventing cracking and gaps opening up, the wood should be at least as dry if not a little drier than the expected location where it will be placed. This is why most woodworking is done with seasoned wood. Wood is hygroscopic like a sponge, but once it loses its bound moisture and goes through enough of a seasoning period, it becomes much less so. As you noted, dry wood is usually more brittle. If you want to restore some of the softness to the wood without effecting its stability too much try soaking it in a glycol-alcohol mixture, such as RV antifreeze, the pink nontoxic kind. There is also the commercially available high molecular weight polyethylene glycol (PEG) for wood stabilization, but I've never tried it. Gluing will be affected though.

-

I guess Beech is often used for scale oak because of its prominent rays which resemble those of quarter sawn oak in miniature, but if your scale is big enough, slow growth oak branches and twigs are good too, very soft and have lots of oak character. Castello wood is a nice wood, but it's not box, and can't be worked to the same degree of detail. Real boxwood is all over the UK, and I'll bet more UK boxwood is pruned and discarded every season than could be used by every period ship modeler the world over. But if you need to buy it, there's Chinese boxwood for sale on AliBaba.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.