-

Posts

51 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Philemon1948

-

The reactions concerning my last posts surprise me. But the post is not deleted nor is my account. That surprised me too, I thought this would have happened much earlier. I promised to say something about the article Ab Hoving has written about drawings kept in the maritime museum in Amsterdam. Ab claims these drawing are forgeries. I have read the article and wasn’t surprised by its content. It’s characteristic for how Ab Hoving writes. The article is published in ‘Scheepshistorie 24’, a glossy magazine with all kinds of articles concerning ships, shipbuilding and related subjects and is written in Dutch. Citations are given in Dutch together with a translation. The article is called: “Zeventiende-eeuwse Hollandse ontwerptekeningen. Echt of namaak?”, “Seventeenth-century Dutch design drawings. Real or counterfeit?” The article opens with the following two sentences: “De methode die de Nederlandse scheepsbouwers in de zeventiende eeuw bij de bouw van hun schepen gebruikten, was het zogenaamde huid-eerst systeem, waarbij de buitenbeplanking maatgevend was voor de vorm van de spanten. Tekeningen kwamen daar niet aan te pas.” “The method Dutch shipbuilders used in the construction of their ships in the seventeenth century was the so-called skin-first system, in which the outer planking was decisive for the shape of the frames. Drawings did not fit in this process.” First of all, there is no ‘general method’ used to build ships in the seventeenth century Dutch republic. But the second sentence is the most revealing. Ab claims, to the aid of the building process, drawings were not used. But there is no substantiation whatsoever to back up this claim nor have I ever read one in Ab’s work. The claim also raises questions as to why this article is written? If you are so sure that drawings were not used to the aid of ship construction in the seventeenth century Dutch republic, why would you write an article about them? In fact, you can skip the article and go straight away to the conclusion: these drawings are forgeries. Of course they are, because if someone proposes these drawings could have a relation with shipbuilding in the seventeenth century, the only way to break off a discussion which is not favourable for Ab’s own unsubstantiated opinions, is to declare they are fake. This is circular reasoning. The article itself contains the same way of making claims and assumptions who are not substantiated. Like the remark: “De stand van de techniek in Storcks dagen was van een ander niveau dan hier wordt gepresenteerd”, “The state of the art in Storck's (the author of the drawing red.) day was of a different level than is presented here”. Of course this remark is without any substantiation. Do I need to explain the bluntness of this remark? I won’t go into great detail to what Ab states because that isn’t necessary. I would merely like to mention one basic assumption Ab makes. I have the impression Ab doesn’t even know he makes this assumption. But it is a huge mistake. In general this assumption comes down to the notion that how a process is executed in our time, that is what would have happened in the seventeenth century. But this will prove to be a very dangerous assumption. I will give one simple example. Many original copies of Nicolaes Witsen’s book about shipbuilding in the Dutch seventeenth century republic contains a portrait. The caption states his name, his age, 36, and the date his book was published, 1671. But Nicolaes was born in 1641, so by the time his book was published he would have been 29 or 30 years old. How is it possible a portrait of Nicolaes at the age of 36 was present in his book? The answer is simple and I think I have said something about it somewhere on this forum. The assumption here, which causes the confusion, is books are made in the seventeenth century Dutch republic the same way as we do it now. And that is not the case, which provides the answer. The assumption Ab makes about these drawings is that they are made prior to construction. That is the way we do it now, first you make a drawing, after that you start construction. This assumption leads to the fact that Ab thinks the drawings he uses as examples in his article, are correct geometrical representations of the ship to be built. The consequence is that Ab frantically tries to prove one ‘fault’ after another in these drawings. But were these drawings made prior to construction and are they made to represent a correct geometrical representation of the actual ship? As said at the beginning of this post, according to Ab, drawings were never used for the benefit of construction. So why does he bother to try to expose them as badly conceived and ultimately as fake? If Ab’s case, drawings were not made prior to construction, is a strong one, there is no reason to do that. I will give another example. In the eighteenth century Dutch republic drawings were produced to the aid of constructing a ship. What was the procedure? I think almost all of the eighteenth century drawings we now know are made during or after construction and not prior to construction. Can I prove that? Yes, I can. I will try to describe this as brief as possible. In the specifications and conditions, written before a ship was build and issued by the Admiralty of Rotterdam, many measurements were recorded. What was not recorded were the layouts of the decks. These layouts are mentioned in the specifications as “shall be decreed”. These layouts are crucial for a complete longitudinal design. Yet, these layouts are established during construction. And indeed, notes of the secretary of the Rotterdam Admiralty show that after about two months of construction work, the layout of the decks is officially established. So what did the building process look like in the eighteenth century? What kind of drawings did they use prior to construction? The answer to these questions sheds some light to the drawings made in the seventeenth century. Because I think drawings were indeed used in the seventeenth century Dutch republic to the aid of constructing a ship. To answer this question how this was done you need a thorough understanding of the process of building a ship. I don’t think this concept has reached Ab Hoving, far from it. I only encounter unsubstantiated claims and assumptions. Years ago I put aside the books of Ab because for me they are completely irrelevant. Which brings me to another subject. If you don’t have any knowledge about historic shipbuilding, you can still read an article in a critical way. That is why I am still astonished how it is possible Ab Hoving is regarded as an expert? This present article about drawings from the seventeenth century Dutch republic is written in a way that a critical reader easily recognizes as being seriously flawed. How is it possible people don’t see through that?

-

Hello Hubac's Historian, Thank you for your reaction. Let me start with who I am. I don’t think that really matters. A forum like this is a platform on which you can publish things if you think you have something to say about the subject, no matter who you are. I don’t think position, status and reputation are things that matter in a genuine substantive discussion as long as the participants involved are content competent. And I think I am. Concerning Ab Hoving, I wonder how it is possible this man is regarded as an expert concerning shipbuilding in the seventeenth century Dutch Republic? And I will tell you why I am asking myself this question. I started about ten years ago with an analysis of the book ‘De Nederlandsche Scheepsbouw Open Gestelt’ written by Cornelis van Yk and published in 1697. I assumed Ab Hoving had done thorough research with regard to the books of Nicolaes Witsen so, in case I got stuck with van Yk, I could try to find an answer in Ab’s book about Witsen. But nothing could be further from the truth. There is not one single question I asked and ask myself which is answered by Ab’s book. His book is superficial and for me completely useless, like it is useless for anybody who likes to have a deeper understanding about shipbuilding in that age. When I discovered this I couldn’t believe it at first. This can’t be true, I must be making a mistake. But no, unfortunately. It would have been much better if Ab’s book could be used as a support for my own work. I have published a number of articles on this forum where I point out many strange contradictions and omissions in the books of Nicolaes Witsen, all of whom are completely missed by Ab. I decided years ago to take Witsen along in my analysis and leave Ab’s work for what it is. Ab Hoving doesn’t bother me, I am completely independent and I am only interested in people who are genuinely capable to discuss the subject, so knowing the sources, use their knowledge in the discussion and be able to listen. Unfortunately Ab surfaces once in a while when I am doing my research and meet people. This is the case with the seventeenth century drawings in the collection of the Maritime Museum in Amsterdam. For years I vaguely knew of the existence of these drawings but I had never seen them. That changed in February this year when I met someone who is handling a subject which has relations with what I do. And he uses the book of van Yk to tackle some of his questions. He showed me digital copies of these drawings, 12 in total, made by an unknown artist. This convinced me that these drawings could give information about certain questions I have concerning van Yk’s book. But at the same time I was told these drawings were forgeries according to Ab Hoving. Knowing the substantive quality of Ab’s work I doubted that and simple reasoning makes clear that it is impossible for someone like Ab to make such a statement. If you want to prove these drawings are forgeries you need to be an expert on subjects like paper, ink, handwriting and art history and you need to do hands on research on these drawings. Ab is not qualified on one of these fields neither did he perform the necessary research on these drawings. The Maritime Museum Amsterdam however did investigate these drawings recently which confirmed they date from the second half of the seventeenth century. So these drawings are genuine. Since I have not read the article in which Ab apparently states these drawings are fake I decided to order the magazine in which this article is published to read with my own eyes what arguments Ab presents to make the reader belief these drawings are fake. I expect to receive this magazine next week. I am very curious what to expect but I suspect Ab raises the same kind of smokescreens as he does in his other work. I know Ab Hoving is regarded as an expert in the field of shipbuilding and according to you: “He has done far more than most to bring light and understanding to this time period where knowledge was spoken from one generation to the next, and perfected through the doing of the thing”. As said, I discovered years ago you can have some doubts about that. But if I say this and make my point by giving clear examples, I am usually met with hostility. I don’t care about that but it raises a very intruiging question: how it is possible people think Ab is an expert? The most striking feature of Ab’s book about Witsen is the fact Ab uses tricks to make the reader believe he knows while he does not. This is the hallmark of the charlatan. Grete de Francesco gives in her book ‘The power of the charlatan’ (1939) a definition of a charlatan: “one who pretends to know what he does not know, boasts abilities that he does not possess and proclaims talents that he lacks”. It would be interesting to analyse Ab’s book with regard to the methods he uses to pretend he knows what he is talking about. I won’t do that here, everybody who is able to critically read a text can do that. But the above mentioned subject about these seventeenth century drawings is very suitable as an example of how Ab goes to work. Again, I would have liked this to be very different. I am not very fond of trumpeting forth negative statements about the work of others but I know first hand that Ab is capable of causing considerable damage by imposing himself as an expert by pretending to know what he doesn’t know. As soon as I have read the article Ab wrote about these drawings I will give a comment. And last but not least, I am a shipwright and worked for years in traditional settings concerning ship reconstructions and restoration projects. But before I started my career I was a student at Art School. I don’t think I am searching for absolutes but I am searching for what can be said about the books of Nicolaes Witsen and Cornelis van Yk concerning the very practical question: what is the practical meaning of these books? And can I build a ship with the information which is presented in these books?

-

Hello Waldemar, I wouldn't give my head for that statement. The drawings show too much intriguing details to be regarded as drawings who are solely made for a purpose like beauty, sales or for display. But since there are no written sources to confirm this there is nothing you can say with any certainty. Because these drawings are unique the only thing you can do is trying to find a sort of inner consistency which might point to some use. The latter is also true for the books of Cornelis van Yk and Nicolaes Witsen. You can never state these books are very reliable because the references for both books are very poor. These books are unique and so are these drawings.

-

Hello Hubac's Historian, Thanks for your reaction. What you state could very well be true. But the question is how? Is the drawing a geometrically adequate representation of the ship which was built and is to be build? How do you ‘read’ the drawing? And if this drawing is a way to record a specific successful design in order to be able to repeat its characteristics in the next ship to be build, how is the drawing used in the building process? If you mention a purpose why these drawings are made, this should be accompanied by an explanation or substantiation for this claim. I absolutely do not pretend to know it all but I ask questions and try to do just that, give a substantiation if I am making a claim. I haven't read the article Ab Hoving wrote, about the seventeenth century drawings in the Amsterdam maritime museum being forgeries, but knowing his work, which is crammed with unsubstantiated claims, I would not be surprised if this is the case there too. I like to stay far removed from this.

-

A bit off topic but not so much : Recent research on materials used for a number of drawings kept in the Maritime Museum in Amsterdam show these drawings were made in the second half of the seventeenth century. That means that besides these, to my knowledge, 12 drawings made by an unknown author, together with the drawings made by Jacobus Storck and Johannes Sturckenburgh, are made in this century. This is interesting news. I can prove most of the drawings made in the eightheenth century Dutch Republic are not made to facilitate building but are made during and/or after construction. So, what was the purpose of making drawings in the eighteenth century? And what was the purpose of making drawings in the seventeenth century? What was the relation of these drawings with the building process? How do they fit in? What do these drawings show and why? These questions could be the start of an interesting discussion.

-

One of the strangest remarks, made by Nicolaes Witsen in his books (1671 and 1690), is what he states in chapter eighteen: “Het Schip hier in gedachten gebouwt is noch van de wydtste noch van de naauwste slagh; welke maat met voordacht is genoomen, om zoo wel een Oorlogh- als een Koopvaardy-schip te vertoonen”, “The ship built here in mind is nor the widest nor the narrowest kind; which size is chosen deliberately, to be able to represent a warship as well as a merchant ship”. This statement is an echo of an earlier statement Nicolaes makes at the beginning of chapter eight: “Hier toe laat een Pynas - schip, (by gedachten gebouwt) lang over steven 134 Amsterdamsche voeten, en in al zyn deelen ontleedt, tot voorbeeldt dienen”, “To this end a pinas ship (built in mind) long over stem and stern 134 Amsterdam feet, and dissected in all its parts, serves as an example”. These sentences contain the same remark; “built in mind” suggesting Nicolaes presents an imaginary, virtual ship. Nicolaes identifies this ship as a pinas. Concerning the assumption that Nicolaes presents in his books a virtual ship, I made this assumption too, before I started to have a closer look at what Nicolaes actually presents. The text directly following the quoted remark from chapter eight, about his example ship, contains an enigma: “na welkers maat en gestalte, zoo de zelve recht verstaan wort, men zeer lichtelyk Scheepen van onbegreepen lengte en gebruik, (mutatis mutandis, verandert het geene verandert dient te zyn) zoo wel groote als kleine, na vormen en toestellen kan; want alle regels, even-maat en gelykdeeligheit, blyven van eenderleye aart op alle kiels lengten, 't zy het Schip een kiel heeft van 180, of slechts van 60 voeten lang. Ik zal hier vaste grondt-slagen, en wetten, hoe men alle Scheeps deelen, ja zelfs een geheel Schip, maken moet, genoegh-zaam trachten ten toon te stellen. Hoewel echter waar is, dat het niet wel doenlyk is, altydt de wis-konstige maat ten vollen na te komen, wegens de menighvuldige, en onderscheidelyke kromme en gebogen gestalten, die men de houten aan een Schip geven moet. Waar vandaan het zeggen komt, dat twee Scheepen, of twee menschen, elkander nimmer ten vollen gelyken. Doch hoe naauwkeuriger d'evenmaat en gelykdeeligheit in het Scheeps-bouwen gevolght wert, hoe volmaakter, cierlyker, sterker, en wel bezeilder het Schip zal zyn”, “after whose size (this ship red.) and shape, if properly understood, one can very easily make ships of unknown length and use, (mutatis mutandis, after the things are changed that needed to be changed) both large and small, to shape and make; for all rules, equal and proportionate, are of the same kind on all keel lengths, whether the ship has a keel of 180, or just 60 feet in length. I shall establish firm foundations, and laws, how to make all ship parts, yes, even a whole ship. While it is true, however, that it is not doable, to always follow the exact measure fully, because of the many, various and bent forms in which the wooden parts for a ship must be shaped. Whence comes the saying that two ships, or two men, are never exactly alike. But the more closely the proportion and equality is followed in ship-building, the more perfect, neater, stronger, and more sailable the ship will be.” The message is quite clear: no matter the length of the keel, if you stick to the recommended ratios you will end up with a good ship. But strikingly enough Nicolaes does not follow his own recommendations. Chapter nine of Nicolaes’ book starts with around six pages where ratios are given, the ratios about which Nicolaes states: “for all rules, equal and proportionate, are of the same kind on all keel lengths, whether the ship has a keel of 180, or just 60 feet in length”. After these six pages, these ratios are followed by the measurements of his ‘example ship’ a pinas, long 134 feet over stem and stern. These measurements do not follow the given ratios, to say the least. Only one measurement corresponds: the height of the bilge. The other measurements deviate and not in a minor way. From 40 mentioned measurements one is equal, seventeen differ ten to twenty percent, fifteen differ twenty to fifty percent, five fifty to one hundred percent and two more than one hundred percent. What is happening here? How is it possible the measurements differ this much from the ratios Nicolaes gives? To be continued.

-

This post is actually a kind of appendix to the previous one that dealt with the use of drawings in the seventeenth century building process in the Republic. As an introduction I use a quote by Cornel Bierens from his book 'The hand-sawn soul', with the subtitle 'On the return of craftsmanship in art and surroundings'. Cornel starts with a quote from the sociologist Richard Sennet. “In 1926, after he thought he had solved all the problems of philosophy and spent some time as a teacher and gardener, the 37-year-old Ludwig Wittgenstein began a new career as an architect. He designed and built a house in Vienna for his sister Gretl, which was to immediately become 'the foundation of all conceivable buildings'. Thanks to the excessive wealth of the Wittgenstein family, the ambitions were not subject to any material limitations and the building came in exactly the sizes and proportions that the designer had envisioned. When he discovered to his horror just before completion that the ceiling of a large salon was three centimeters too low, he had it raised after all. After that huge surgery, he showed himself satisfied. Still, something kept gnawing, and eventually he understood what it was all about. In a note to himself, he wrote that while the house had “good manners” it also had “failed health.” It lacked 'original life’. The American sociologist Richard Sennet tells this story in The Craftsman (2008) and fully agrees with Wittgenstein's self-criticism. He compares him as an architect to Adolf Loos, who also built a house in Vienna (Villa Moller) at the same time. The difference is not that Loos had less strict starting points (he did not, for example, deal with ornaments, he considered them signs of primitivism), but that, unlike Wittgenstein, he always continued to look and act like a craftsman. For example, he spent a lot of time on the construction site and continuously sketched how the light fell at different times of the day. Wittgenstein, on the other hand, did not like sketches and was especially obsessed with exact proportions. Sennet lists a number of characteristics of craftsmanship, all of which are the opposite of what Wittgenstein did: determining in advance what he wanted to achieve, not deviating from his rules, seeing unforeseen difficulties as a hindrance, striving for perfection and erasing all traces of the creative process. Loos took a much more playful approach, kept his plans flexible, saw setbacks as new opportunities, improvised continuously and created a rhythmic, organic building in the process. He allowed thinking and execution to flow into each other, which is why he is a craftsman. Because he not only thinks with the head, like Wittgenstein, but also with the executive hand. That thinking, executing hand is the pivot around which Sennet's book revolves. “Every good craftsman conducts a dialogue between concrete actions and thinking,” he writes. And also: “All skills, even the most abstract ones, begin as physical exercise.” Craftsmanship is making something for the sake of making it, focused on the thing itself, on standards set by itself. It is not a phase in human production history that can be overcome by clever engineering. It is a 'sustainable, basic human drive'. Of all time. Except for the twentieth century, which believed that craftsmanship could be overcome. Progressive thinking was the norm, rationalisation the key word. Everything would become more efficient, even eating, and it wouldn't be long before we would just as easily take all those nutrients through pills. Our hands wouldn't have to make anything anymore and our teeth to chew anymore. Poor futurologists. We are now short of hands and there is no higher art than cooking.” Thus the quote from Cornel. If you set yourself the task of describing the building process of a ship in the seventeenth century Republic, you cannot ignore this notion. Its great difficulty is that you cannot recover the attitude of the craftsmen at that time. I have made statements about this before, also with regard to the so often used word 'authentic' and what we should understand by it. For the time being it is impossible to transfer the mentality of the seventeenth-century craftsman to a present-day one. The question is, is it necessary? In a lecture I once gave about what I had in mind for the reconstruction of the ‘Delft’, an eighteenth century warship in Rotterdam, this sentence can be read: “Doing something while you are closely connected to what you do is the key aspect”. That's why I think that if you want to understand the books of Nicolaes Witsen and especially Cornelis van Yk well, you have to know a craft from the inside. That doesn't necessarily have to be the carpentry trade, but that certainly helps. In essence, it is about recognising the way of working, as can be read in the quote by Cornel Bierens and Richard Sennet. My proposal to view drawings such as those in the shipping museum in Amsterdam in this way fits seamlessly into such a process. In other words, a drawing is not regarded as Wittgenstein would, and what we do nowadays, as a geometric representation from which no millimeter may be deviated, but as a kind of sketch or intention within a given geometric frame. Moving back and forth and to and from the object you are working on, is also an essential factor. I also do this while writing, I zoom in, continue to distance myself, look at other things and look at how everything relates to each other. And do something else in the meantime. Writing is also a craft. Recently, an analogy occurred to me for this process that does not quite cover it, but comes pretty close: Emmenthaler cheese. While reasoning and writing you try to visualize your subject. That's the cheese. The better you do that, the better you can see where there is no cheese: the holes. It's not quite right because knowledge is also more or less fluid. Things can shift and sometimes a different coherence arises when you discover something new that makes you look at things differently. This is far from vague whining. It stands in a tradition as old as humanity itself. “It is a 'sustainable, basic human drive'. Of all time."

-

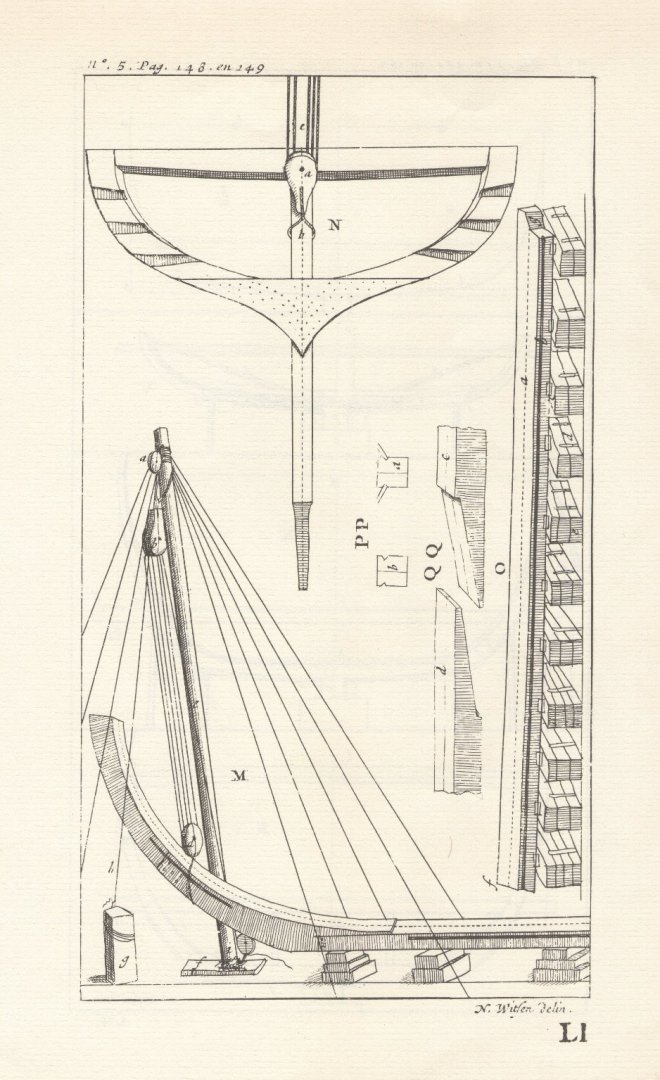

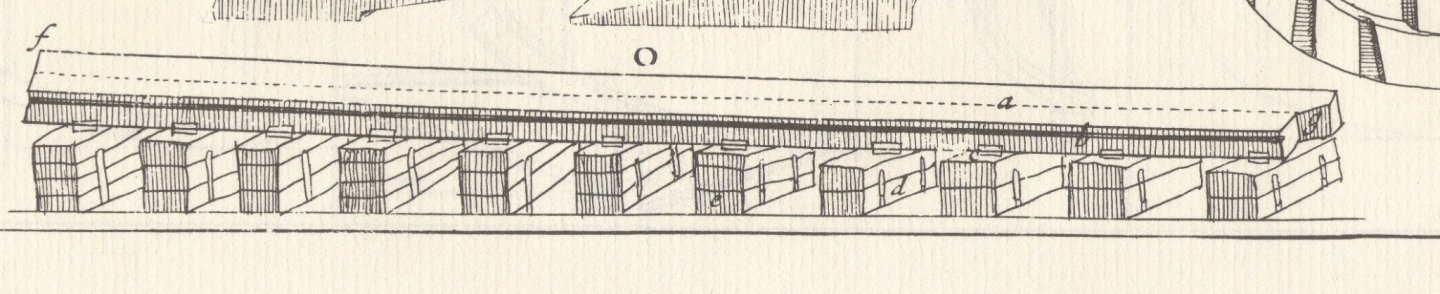

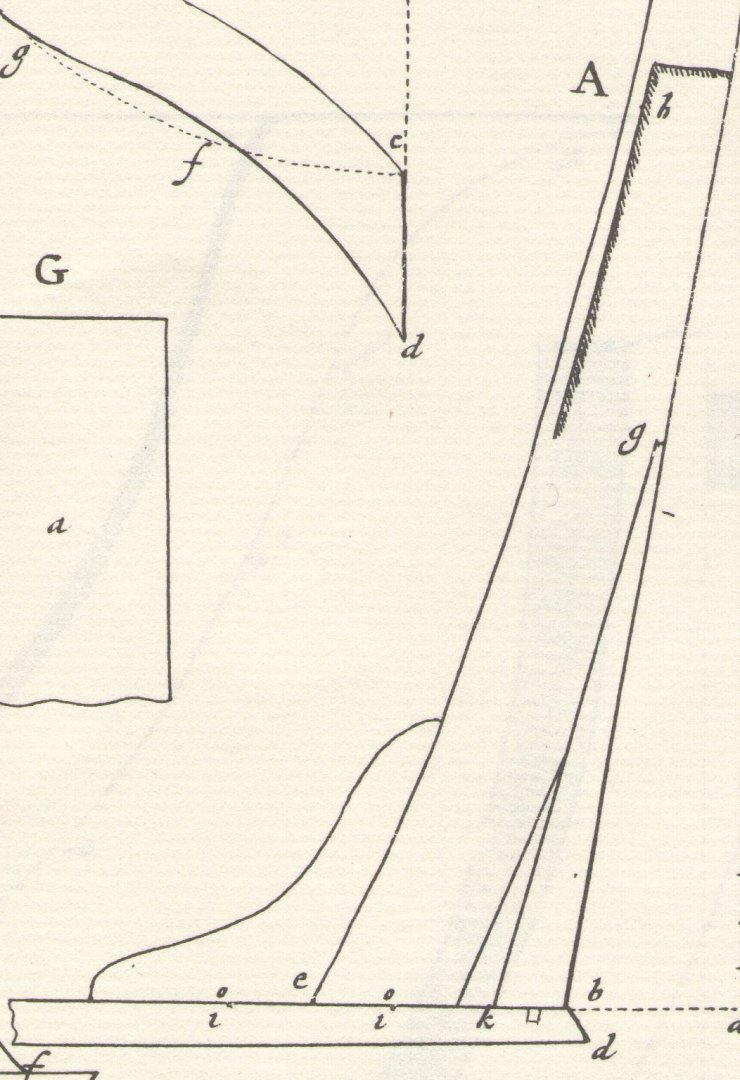

Drawing A.0149(0860) from the Amsterdam Maritime Museum. The drawing below is in the collection of the Amsterdam Maritime Museum with collection number A.0149(0860). The drawing is dated around 1650 and slightly worked up in contrast. I believe I have heard rumours that this drawing is a forgery. I'm not going to assume that for now. I approach this document in exactly the same way as I approach the books by Cornelis van Yk and Nicolaes Witsen. These books, like this drawing, are one of a kind and if there are no sources to shed light on their origin, you can only do one thing: try to establish the content consistency. Is the information presented in these documents mutually consistent, are there inconsistencies and/or omissions? In this case this means: is it possible to link the information that the drawing seems to give to what Nicolaes and Cornelis report? The main question is what was this drawing for? Was it made prior to construction, during or after construction? Many drawings have survived from the eighteenth century Dutch Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and almost all of these drawings were made during or after construction. I can prove that too, although I'm not going to do that here now. What concerns me is that I think this also applies to this seventeenth-century drawing from the Amsterdam Maritime Museum. I believe that this drawing was also made during or after construction and not directly for the purpose of construction but indirectly. This means that the geometry of the ship was not determined with this drawing, and no measurements were taken from this drawing. Then the following question arises: what did the building process look like and how can this drawing be part of it? In other words, what information do you need to determine the shape of the hull, especially of a large ship? I will go through this process briefly and try to make clear where in this process this drawing could play a role. Before I do that, I want to highlight one characteristic of this drawing and draw a conclusion from it. It seems that the drawing emphasizes profiles of some parts. It is striking that the profile of the stem is given on the inside. Cornelis van Yk does that too. He first determines the inner profile of the stem and then works outwards. Nicolaes Witsen does not give a clear description of this but in his case the total length of the ship is constituted from the rakes of stem and stern and the length of the keel, whereby the rake of the stem is measured from the front of he stem to the front of the keel. Cornelis van Yk doesn’t do this, he determines the rake of the stem from a certain point, the node, to the inner top of the stem. For this reason I think that this drawing can be related to the building method that was in vogue in the southern part of the Dutch Republic, the surroundings of Rotterdam and Zeeland. Cornelis van Yk is the one who describes this construction method. What does Cornelis van Yk describe? The keel and sterns are made, the keel is placed on stocks, and the sterns set. Then the garboard strakes, the first planks of the hull on both sides of the keel, are applied. The garboard strakes determine the course of the bottom of the ship and the direction in which these garboard strakes leave the keel is determined by the rabbet in the keel. That is why the profile of this rabbet is such an important factor when shaping the hull. Then two middle or main frames are placed on the keel. Subsequently the sheer strake is set. The shape of the sheer strake is determined in a flat plane and then folded to form the perimeter of the ship. There is nothing that you can deduce or measure from when determining the sheer strake. These measurements must have been known in advance. That to me is a very intriguing fact, together with the fact the sheer strake is a plank, comparable to an outer hull plank, which is located at a height of seven to eight meters and weighs 600 to 800 kilos, while there is nothing to see at all in terms of structure except two main frames and the stem and stern. You will need to make a heavy load-bearing structure to be able to attach this sheer strake at this height as well as scaffolding at that height to be able to work and fair the sheer strake. How and why was this done? Why are you putting on so much work to install this sheer strake? Apparently placing this sheer strake was of great importance for the further construction process. I can't think of anything other than that the sheer strake mainly serves as a reference in the process afterwards. I will come back to this in a moment. The profile of the main frame indicates the direction of the bottom midships. According to the profiles that Cornelis gives, the bottom is completely flat. Battens are set together with the components of the frames, the futtocks. These battens show the way, as it were, how the entire construction develops. The battens are too thin to be able to build up tension by themselves and will therefore always have to be supported by the futtocks. The scaffolding grows along with the growth of the number of futtocks. In order to be able to determine how the hullshape develops, the sheer strake comes into view. Together with lines that are strung in the ship's median longitudinal plane, the sheer strake is the reference to see how the ship should develop in width at each point in the longitudinal direction. This is done with perpendiculars that indicate exactly how far the futtocks have approached the widest point of the ship, which is the sheer strake, at each height. When setting the timbers, you pay attention to how much the futtocks overlap. Finally, all the futtocks are made beneath the sheer strake and the last fairing round can begin, whereby the ship is faired to its final fairness of bevel with a chalk line, while simultaneously determining the boundaries of the hull planks. The use of the drawing comes into view with the construction of the futtocks from keel to sheer strake. How did they determine the shape and bevel of the various futtocks? That must have been a combination of looking very carefully while following the course of the battens. A drawing that gives you a reasonable idea of the development of the shape of the hull can help. The determination of that hull shape is always done by estimating at each point, what the direction of the relevant part will be and the resulting shape. This is done in conjunction with the battens and the sheer strake. So you keep moving back and forth from the place where you are working to the bigger picture. You don't have to work terribly accurately because you know that at the end of making the futtocks there will be a last process that definitively determines the final fairness of bevel of the ship. In one sentence: for keel, stem and stern, sheer strake and main frames, dimensions are required that must be known in advance, for the subsequent process of determining the shape of the hull, the basis is an estimate of the shape within the margin offered by keel, stem and stern, main frames and sheer strake. In other words: to get an impression of the shape you want, this drawing is a tool, not a prescription. It is not inconceivable that very simple moulds were made based on the profiles that can be seen in the drawing. In that case, the drawing is used more directly to be able to determine the shape of the futtocks, but even then there is still no question of direct dimensioning. In any case, the ship's carpenters at that time must have had a very well-developed sense of form to make this method possible. At least, in my, not so humble, opinion.

-

Hello mtaylor, You state: "The word "rivet" implies that the end is hammered such that it's flat and not bent and done in past with the metal being hot". That is exactly what I was thinking reading he descriptions of Nicolaes Witsen. A rivet implies an extrusion of material in all directions over a plate or a surface. That is not the definition of a 'bent end' as we would describe it today. This rather looks like an uncertainty between what they understood als a 'klink' in general and what we understand today as a 'clink'. So it is a matter of definition and these uncertainties are present with regard to much more understandings, for instance in the case of a 'joint' between two wooden construction pieces.

-

Understandings that have disappeared from our language. There is at least one major advantage of Nicolaes Witsen being an outsider with regard to shipbuilding in his time. The vast amount of information Nicolaes presents seems to be a compensation for not being able to describe the trade from within. This information includes a glossarium at the end of his book where many understandings and proverbs are gathered, many of which have disappeared today. There is a striking example of an understanding which has disappeared today but is vital for understanding something Nicolaes mentions in his book. It is also a good example that a translation is also always an interpretation. Nicolaes states: “Het Kolzem is breeder als de kiel, (…..)het werdt met bouts aan de kiel vast geklonken: het dient tot stevigheit van 't geheele Schip, en magh te recht een binne-kiel genaamt worden” How do you translate this sentence and in particular the word ‘geklonken’? ‘Geklonken’ is a conjugation of the verb ‘klinken’ and is a Dutch word which, in the shipbuilding trade, usually translates as ‘to rivet’. If you use this translation the sentence translates to: ‘The kelson is wider than the keel, it is riveted with bolts to the keel: its purpose is to strengthen the whole ship, and may be rightly called an inner-keel.’ At first glance you think the kelson is mounted in the ship with bolts who are riveted at one side. Bit this is highly unlikely if not impossible. If you take for example a ship with a keel of about 2 feet square, the bolts, who are going through the kelson, which has a height that matches that of the keel, first futtocks, keel and shoe, must have been more than a meter long. These bolts can only be applied from within. There is no way you can hammer a bolt about one meter long from the underside of the ship as it is rest on stocks with just a limited amount of space underneath the keel. If these bolts are to be riveted, the top of the bolt is made red hot and hammered through the kelson, futtocks, keel and shoe to be riveted under the keel at the other end. That doesn’t make any sense. First you try to make a watertight seal with cowhair and tar between keel and shoe as Cornelis van Yk describes and subsequently you hammer a bolt through all that. Besides, riveting underneath the keel of bolts of that size is nearly impossible. Furthermore the underside of the shoe should be completely flat without protruding heads of bolts, to prevent trouble during the launch of the ship. But Nicolaes specifically states: “geklonken”. The answer to this riddle is, in the seventeenth century Dutch language, ‘klinken’ can have more than one meaning according to Nicolaes. In his glossary he gives these meanings: “Klink. Het krom omgeslagen eindt van een spyker, of bout.” ‘Klink. The hammered bent end of a nail or bolt’ “Klinken. Stukken hout aan een slaan. De einden der spykers om slaan. Iets buiten boort toe dryven”, ‘Klinken. To beat two peaces of wood together. To hammer and bent the tip of nails. To force something outboard.’ “Klink-werk. Hout-werk, van 't welke de planken, of balken, met hun kant op elkander leggen.” ‘Klink-werk. Putting wood, wether planks or beams, on eithers sides.’ It is apparent the meaning of ‘klinken’ in the mentioned passage about the kelson cannot be translated by the understanding ‘to rivet’. What Nicolaes is saying can be better described by ‘to beat two peaces of wood together’ or ‘putting wood, wether planks or beams, on eithers sides’. This meaning has disappeared from the Dutch language today. But ‘klinken’ in the Dutch language today still means ‘to sound’ or ‘to clink’. The last word indicates the relationship between the two languages English and Dutch. So what Nicolaes describes is that the bolts with which the kelson is attached to the keel are driven through the layers of wood but not completely through the keel. Nicolaes states this at another place in his book: “Ondertusschen maakt men het Kolsem (…..). Men slaat door elk of om 't ander Buik-stuk een bout met een Italiaans hooft, tot door het Kolsem, en op 11⁄2 duim na door de Kiel.” ‘Meanwhile one makes the kelson (…..). One hammers through each or alternating futtock a bolt with an Italian head, through the kelson, and through the keel but for 1,5 inches. So the bolt does not leave the keel, the hole for the bolt stops 1,5 inches above the bottom of the keel. Nicolaes unfortunately doesn’t explain what an ‘Italian head’ exactly is. Cornelis van Yk describes the mounting of the kelson to futtocks and keel the very same way, with a bolt that stops above the bottom of the keel. If Nicolaes did not make a note of these different meanings of the word ‘klink’ and ‘klinken’, there is no way of establishing what he could have meant. The translation of the Dutch word 'klinken' by ‘to rivet’ would have been made all too easy, leaving you with the question, how on earth did they pull that off?

-

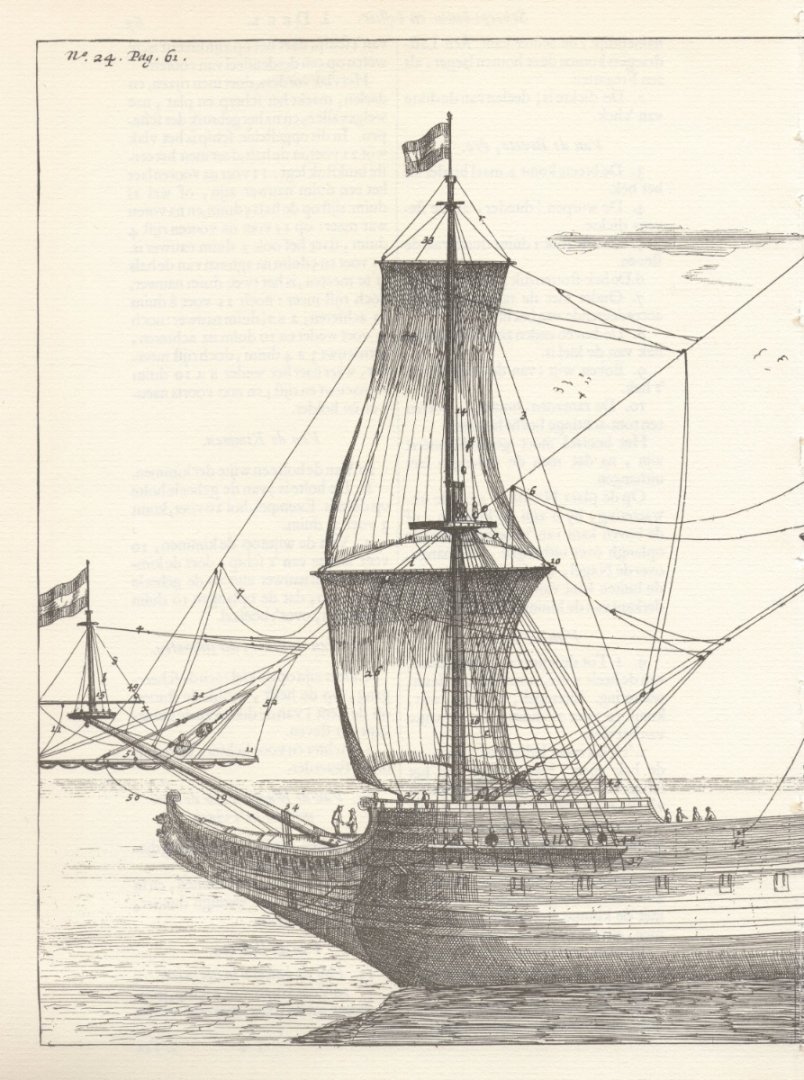

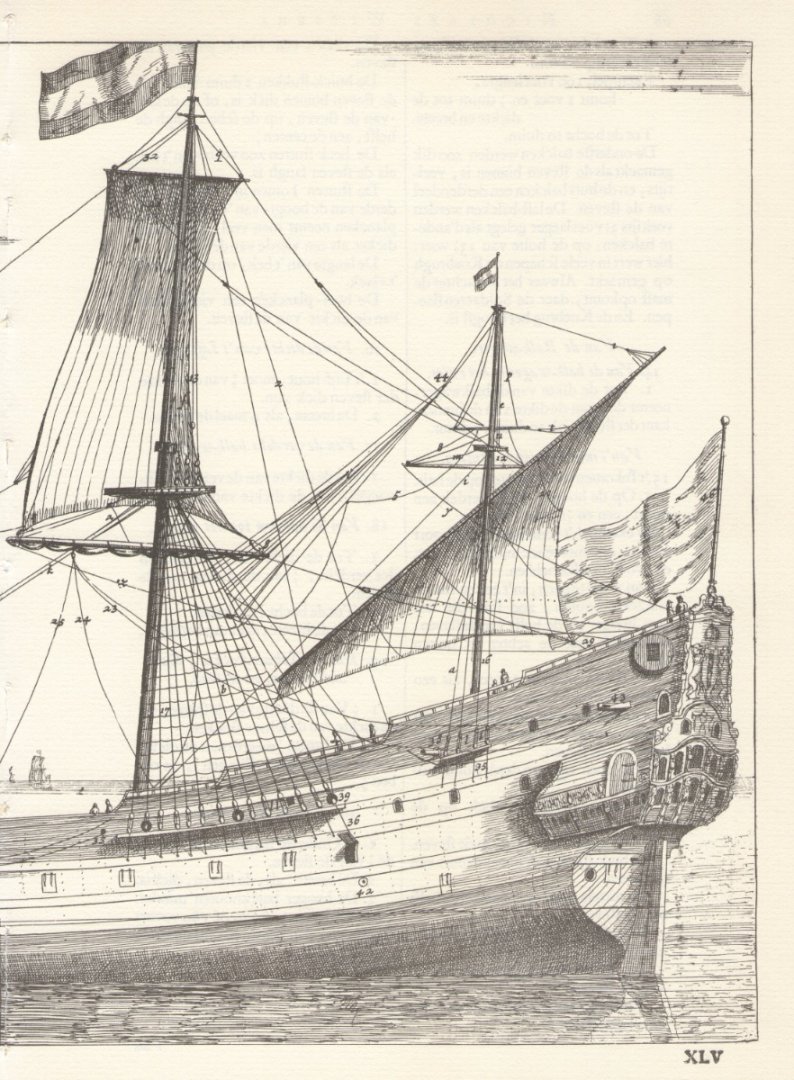

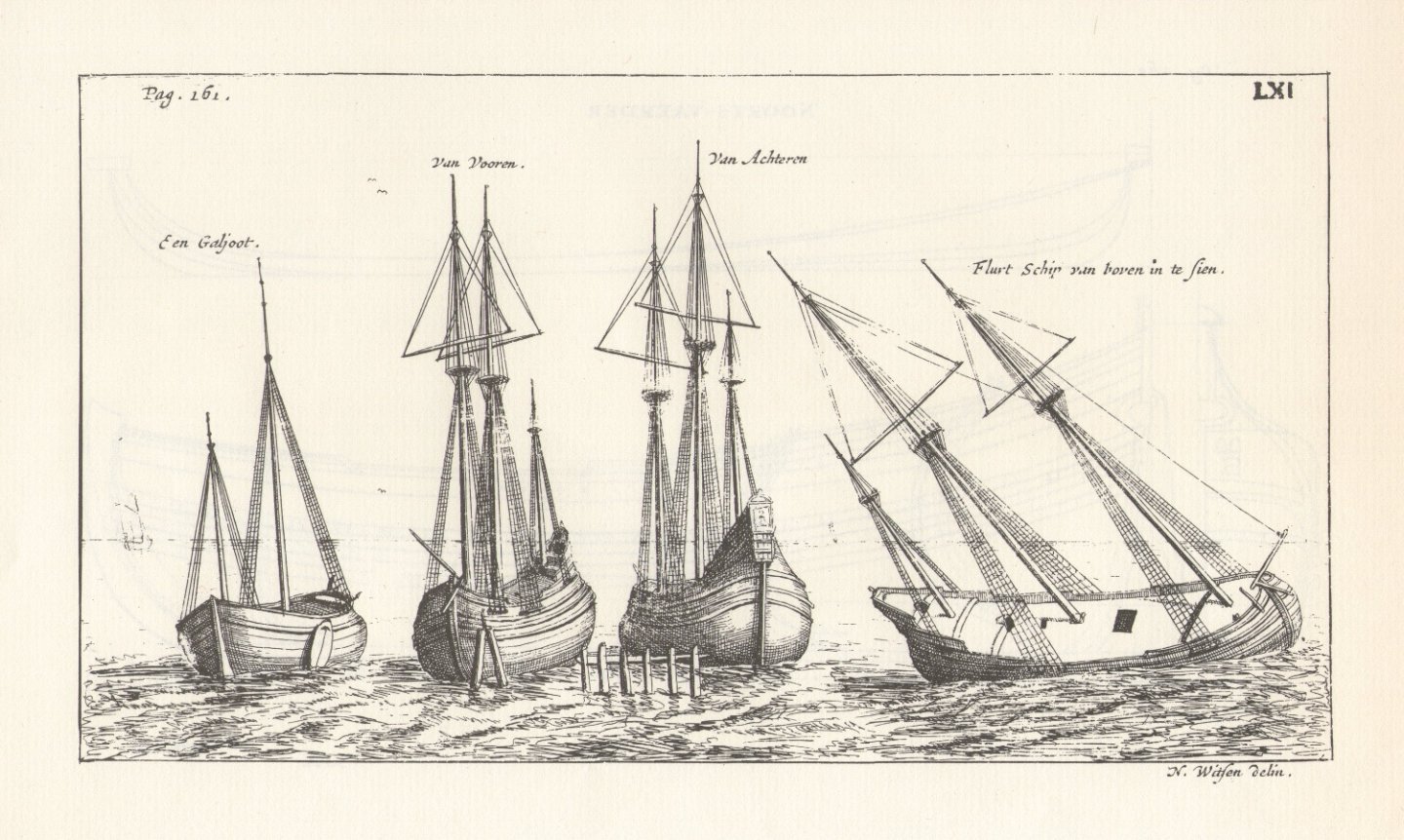

Hello mtaylor, Nicolaes Witsen describes both the pinas and the flute(ship) and so does Cornelis van Yk. Nicolaes gives two pictures, attached to this post. The first is a representation of a pinas, in two parts, the second shows a galjoot and a flute seen from three different angles. The flute and the pinas represent two different ship types although they tend to have many features in common. The main difference in the seventeenth century was the stern construction. Nicolaes Witsen also mentions ‘hybrid’ combinations are possible between the different ship types in use in his days. But it is specifically the stern construction which can be considered as the main difference between the two ship types. Cornelis van Yk literally states he cannot think of a reason why one should prefer to build a flute instead of a pinas and he mentions the stern construction as one of the main disadvantages of the flute. So there is not much reason to argue about the fact these two ship types actually existed and what their features were. The two ship types are often pictured in many drawings and paintings of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. There are a few books who especially describe the flute, but they are, unfortunately written in the Dutch language. But standardisation and the description of the difference between features are always moot points in arguments about different ship types during the ages.

-

Nicolaes Witsen’s 'example ship'. Is it plausible the Diemermeer, a flute ship, built for the VOC chamber Amsterdam in 1659, is the ship that Nicolaes Witsen focuses on in his book? While Nicolaes Witsen himself states that he is presenting a pinas. I need a large chapter to describe that fully substantiated. And I can’t do that here, unfortunately. But I can mention a few main points. In the first place by looking critically at Nicolaes Witsen himself and his book on shipbuilding in his time. The main question is, how reliable are the data Nicolaes provides? Formally speaking, you can't judge this for the simple reason that Nicolaes's book is one of a kind. The chapters on shipbuilding are not only a technical subject, but also a historical one. And in order to verify historical facts, there must be at least two sources that corroborate each other. Some things such as names of ships and main dimensions can easily be checked, but the description of the building process cannot. You can also look at the book written by Cornelis van Yk, but that is a completely different book in terms of content. The only way you have to check whether the data are reliable is to look at their interrelationships. Are these data consistent or do they contradict each other? Unfortunately, Nicolaes's book is not very consistent. And it doesn’t take long to find the reason for that. Nicolaes was born on May 8, 1641. His book was published in 1671. So he wrote his book in his twenties. You can rightly call it a youth work. And it's not all he's done in that time. You can ask yourself all kinds of things about Nicolaes' book. How did it come about, was it his own idea and did Nicolaes wrote it all himself? But that will probably always remain speculation. What you can take as a fact is that Nicolaes tried to tackle a subject of which he lacked a deeper understanding of the construction process. This immediately explains the fragmentary nature of his book and the inconsistency of much of the data that Nicolaes provides. Nicolaes, due to his status, will have had little or no practical experience with regard to the subject he describes. It is precisely this experience that you need to be able to penetrate more deeply into the process that is going on at the yard. Nicolaes must have been almost completely dependent on third parties for the shipbuilding information he presents in his book. And because of his position, it would not have been difficult to gather this information. What then happens is, Nicolaes puts all the information together as best he can, without real insight into what is actually being described and, above all, without insight into how the parts are related to each other. That is why ship-parts show up at different places while it would be better to describe them in one place. While you also find strange omissions and contradictions. And it is also the reason that some very essential concepts are hardly mentioned because Nicolaes cannot judge how essential these concepts are. In other words, the consequence of a lack of deeper insight into the building process, means that you cannot process information received from others and subsequently write your own story because you cannot properly assess this information. You cannot adequately describe what you do not understand. This fact makes it interesting to take a good look at Nicolaes' text and see if you can define and/or recognize specific parts. I will come back to this shortly. The biggest mystery is the ship that Nicolaes calls his 'model ship'. In short: in chapter nine, Cornelis starts with giving general proportions for a 100-foot pinas and subsequently gives the concrete measurements for a 134 foot pinas. And those concrete measurements differ significantly from the proportions given by Nicolaes. This has been a big mystery to me for years: not only the fact and how it is presented, but also how it is possible that hardly anyone has questioned this? Especially if you pretend to have seriously examined Nicolaes Witsen's books. However, one person has made some comments to this but I have the impression that this man is being ridiculed and suppressed a bit. On the basis of the concrete data provided by Nicolaes, I have drawn the conclusion that the 'example ship' that Nicolaes presents as a pinas cannot have been a pinas, nor is it an imaginary ship but an actual existing ship. No one can come up with all these details, especially Nicolaes can’t. The question what the identity of this example ship was remained open for years until I recently came across the data from the Diemermeer. Here the perspective turns half a turn and it is possible to look at data outside Nicolaes' book. It is very strange to see Nicolaes touting the main measurements of his example pinas, 134 feet long, 29 feet wide and 13 feet high, as the sizes of an average pinas, because that is what he says, literally. However, his ship is much narrower than an average pinas. A pinas has a length-width ratio approximately between 4.1-4.3:1, with Nicolaes it is 4.62:1. When suddenly a flute ship slides into my field of view, with exactly the same main measurements as Nicolaes gives for his pinas, this is a big surprise. In itself, independent of Nicolaes' book, the dimensions of the Diemermeer are already special. This is evident from the data from the VOC site. Of the 224 ships for which a length has been given, 75 are 130 feet in length. That means 33.5% of the flutes for which data are known were 130 feet long. 130 feet length was a standard measurement for the flute, established by the ‘Heren XVII’ of the VOC. There are deviations from that standard size. In itself it is intriguing that they exist, because why do you deviate from a standard that was often applied? And there are still quite a few, both down and up. Certain sizes stand out, for example 128 feet and 136 feet. Intriguing about some deviations is why it’s so small? What benefit can you gain from building a ship 128 feet instead of 130? That becomes all the more interesting if these measurements occur several times. The only reason I can think of for a deviating size that occurs once is that there must have been something with the sizes of the available wood, which meant that a desired length cannot be achieved or can be exceeded. But that does not apply if this deviating size occurs significantly more often. The sizes of Nicolaes' 'example pinas' are 134 feet long, 29 feet wide, 13 feet high and these measurements only appears once in the list of VOC flute ships. If Nicolaes himself invented the ship he presents, choosing such a size makes no sense. If you want to present an 'average ship', you choose a standard size, based on a length of 100 or 130 feet. And these sizes apply to both flute ships and pinases. Strikingly enough, Nicolaes also choose a standard size when he mentions the proportions that a 'normal' ship must meet. He gives those proportions and sizes based on the length of a pinas of 100 feet long, which also makes calculations a lot easier. Then suddenly, he switches to a 134 feet pinas, where Nicolaes gives completely different proportions and corresponding measurements. In summary: Nicolaes' example ship has exactly the same main dimensions as appearing only for one flute ship that sailed for the VOC. Nicolaes' example pinas deviates significantly from the proportions for an average ship, proportions that Nicolaes also specifies. From this I conclude that Nicolaes presents a ship that actually existed and that can be identified as the 'Diemermeer', a flute that was built for the Amsterdam Chamber of the VOC in 1659. What should I think of all this now? I find it strange that I have to be the first to make this connection. Some 350 years after the publication of Nicolaes' book. The emphasis of my research is not with Nicolaes Witsen. If it had, I probably would have seen it much sooner because I noticed the mentioned discrepancy between the 100 and 134 foot pinas years ago. The mentioned information doesn’t require an in-depth understanding of the building process. It just takes some skill with a spreadsheet and asking some very basic questions about the basics of shipbuilding at the time. And that starts with the main measurements. The consequences are also significant. Suddenly, the central question is now how it is possible that Nicolaes mistook a flute for a pinas? With that question in mind, I can look much more specifically for clues to this question. One approach is, for example, looking at the structural differences between a flute and a pinas and how this is presented in Nicolaes' text. The stern construction is a good example of this. This construction does occur with a pinas but not with a flute. How does Nicolaes solve that? That means analyzing Nicolaes' text, and in particular, how and what, where is presented. And, last but not least, does the text indicate what Nicolaes himself was aware of? Anyone?

-

The true identity of Nicolaes Witsen's pinas. Cornelis van Yk comments on the flute ship in his book. At the time of the Dutch Republic's existence, the flute played an important role in its economic development. At the end of his comment, Cornelis draws a conclusion: that he has never heard a valid reason to prefer building a flute to building a pinas. The reasons Cornelis gives in his comment, on which he bases his rather striking conclusion, are in my view more than valid. Yet many of those flutes were built, given the role this ship played during the Republic's existence. This comment by Cornelis on the flute has therefore always resonated in my head. Something weird is going on here, but so far I can't get my fingers behind it. What also strikes me is that almost everyone claims that the flute is usually a much narrower ship than the larger and wider East Indiamen. This means that the length:width ratio is different for a flute than for an East Indiaman. But this is not apparent at all from the main measurements of the few flutes that Cornelis gives in his book. The main measurements Cornelis gives for these flutes could be the main measurements for an East Indiaman, perhaps slightly narrower, but not convincingly much narrower. Since Cornelis only gives measurements for a few flutes, this provides too little information to base a conclusion on. So I thought, what if you put the data of all the flutes that sailed for the VOC in a spreadsheet? Then you have some more basis to make a more thorough analysis. This information can be found in the VOC database on the internet. Once that job was done and I did some juggling with this data, the result was revealing. But interesting as it may be, the above is not the reason I am writing this. When I was typing the data of these flutes into the computer, I followed the list as presented on that VOC site: alphabetically. I soon came across the following ship in that list: the 'Diemermeer'. The Diemermeer is a flute ship that was built for the VOC Chamber Amsterdam in 1659. The ship was in service with the VOC from 1660 until it sank on June 28, 1670 at Banda, Indonesia. But what struck me as by lightning were the main measurements given for this ship: 134 feet long, 29 feet wide, 13 feet high. These are exactly the same main measurements given by Nicolaes Witsen for his 'example pinas'. I immediately thought, this can’t be true? That Nicolaes' 'example pinas' is actually a flute? I am already convinced that the example ship of Nicolaes is not a pinas. The specified sizes differ too much the general ratios Nicolaes provides. But if it's not a pinas, then what is it? And what arguments can you put forward for that position? There is only one author, to my knowledge, who also realizes that the ship Nicolaes describes cannot be a pinas. This author is Mr. Kamer who makes a proposal to name the type of ship that Nicolaes describes. He does so in his book 'Ships on Scale' where he concludes, among other things, that it concerns a ship that Nicolaes did not see or has known during his life. The type of ship characterizes Mr. Kamer as a ‘hekboot’, built below as a Noordsvaarder (a type of flute ship) and rigged as a pinas. I can neither confirm nor deny nor investigate this assertion because Mr. Kamer provides no substantiation for it. To my great disappointment. Nor do I know whether such hybrid craft were built in the Republic. But the main measurements of Nicolaes' example pinas certainly make one think of a flute. The ship Nicolaes describes is narrow, the narrowest ship he describes in his book except one. These main measurements are certainly not standard sizes for a pinas or East Indiaman. What is the argument for or against the proposition that the Diemermeer is the ship that Nicolaes describes in his book? The Diemermeer was built in 1659. At that time Nicolaes was about eighteen years old. So he may have known or seen the ship. That argues against the claim. Nicolaes describes a ship with a transom construction which is missing from a flute. He must have been able to make that distinction clear when he wrote his book. But it is certainly possible that the ship was built during his lifetime but that he has neither known nor seen it. Approached slightly different: is it a coincidence that exactly the same main measurements are given for the Diemermeer as Nicolaes gives for his example pinas? If the Diemermeer is a flute that was built for the VOC in Zeeland or Noord-Holland, I would say yes. But that the Diemermeer is a ship with exactly the same main dimensions, main dimensions that do not appear twice in the list presented by the VOC site, and was built in Amsterdam during Nicolaes' lifetime, I say: no. This is a little too coincidental. That raises a lot of questions. Before I came across the Diemermeer, my main question was how it is possible that Nicolaes does not notice the enormous discrepancy between the proportions for ships to be built, which he himself states, and the concrete dimensions that he gives for his example pinas? Now the question is, if the Diemermeer is indeed the ship Nicolaes describes, how is it possible that Nicolaes could mistake a flute for a pinas? For now, I don't have a clear answer to that. But I now 'officially' include the statement that Nicolaes Witsen's 'example pinas' was an actual existing ship. The type of ship is a flute with the name 'Diemermeer', built in Amsterdam in 1659. If this statement is true, it will have rather far-reaching consequences for the substantive approach of Nicolaes' book. To prove this statement I will have to come up with clearer evidence than I present now. Literal proof will probably be difficult but it should be possible to make it very plausible. That is to say, I will not provide direct evidence but rather circumstantial evidence. I will explain that in a 'to be continued'.

-

Hello Waldemar, It took some time to reflect on your last post. I will dive into the last mentioned sources. But I am not very enthusiastic about the books of Ab Hoving. I will explain why. In 2009 I started writing about wooden shipbuilding. My first aim was to write down the experience and knowledge I had gained in a project concerning the reconstruction of a Dutch eighteenth century warship. But, as it happened, I realised very soon that, if you want to say something about shipbuilding methods in the Dutch eighteenth century, you encounter a problem: there is not one single word published about shipbuilding practice in the eighteenth century Dutch Republic. Not in that age, nor since. So, if you are researching the connection between the information that is available about eighteenth century shipbuilding in the Dutch republic and the actual practice in that same age, you end up in the seventeenth century. Two seventeenth century Dutch authors have left their mark in this field: Nicolaes Witsen and Cornelis van Yk. Both wrote books about the subject what the shipbuilding practice looked like in their days. Because the book Cornelis van Yk has written hasn’t been scrutinized and critically approached yet, I thought that would be a good start. I assumed, making this decision, someone else had scrutinized the books of Nicolaes Witsen. Ab Hoving published in 1994 a book about Nicolaes Witsens’s books about shipbuilding and in 2012 a translation of Witsen’s work in English. So, I assumed, if I had some difficulties understanding Cornelis van Yk, I could consult the work of Ab. Gradually I started to discover, not one single question I ask myself, is answered by Ab. At first I couldn’t believe this. How is it possible that the writings of someone who is regarded by many as an expert in this field, are so shallow and meaningless? His book resembles a scrapbook. Ab takes an old book, tares it apart, put some of the parts together again and put some comments to the text. I can write a book like that with ease. Most of the information Ab presents is just a copy of what Nicolaes Witsen already mentions and that is not what I consider to be a critical approach. I started to wonder, for whom did Ab wrote this book? If you are a layman and seek some knowledge about the subject without the need for a deeper understanding, Ab’s book is perfect. The information supplied by Ab is very superficial and doesn’t explain anything. So there is nothing to think about. I will mention a few oddities and omissions, some already mentioned in my previous posts. The first one is the very strange difference between the general ratios Nicolaes mentions and the given measurements of his so called ‘example pinas’. There is just one measurement exactly the same: the height of the bilge. The rest deviates, and not with a small margin. This deviation starts with the main measurements. The ratio length:width is 4,62:1. Nicolaas's example ship is the narrowest of all but one mentioned in Nicolaes’s books. Only the flutes are narrower but they are described by Nicoales as “imaginary”. Can someone explain to me why Nicolaes fails to mention these significant differences between the measurements of his “example ship” and the general ratios he gives? Can someone explain to me why Ab fails to recognize this? Can someone explain to me what ‘imaginary” flutes are? Can someone explain to me why the description Nicolaes presents doesn’t seem to be a pinas at all? The second one is the fact the rabbet in the keel, stem- and sternpost is a vital understanding for shaping the hull. The rabbet is barely mentioned by Nicolaes and, correspondingly, nor by Ab. One of the most difficult procedures in the process of building a wooden ship, which is connected to the rabbet, is fitting the garboard strakes. Nicolaes gives a very cryptic and incomprehensible description of how this is done, which is not explained by Ab. Instead Ab substitutes this very cryptic description with another cryptic description. This substitute given by Ab is also complete nonsense. Oldest trick in the book. This way Ab doesn’t explain anything, he only suggests he understands. But he doesn’t understand and explains anything. Can someone explain to me what Nicolaes writes when he describes the fitting of the garboard strakes? The third one is failing to mention how the sheer strake is made and attached to the ship. Also one of the most important understandings of the whole building process. This procedure is not mentioned by Nicolaes nor by Ab. But it is a very vital and ingenious procedure. The sheer strake is in fact a temporary hull plank which is marked and made in one plane and folded in place, so made spatial, to show the ships circumference. How the sheer strake is designed and mounted is not explained. Can someone explain to me how the sheer strake is designed and made? Can someone explain to me why the strange contradictions and omissions in Nicolaes Witsen’s books are completely overlooked by Ab? I can give numerous examples besides these three. Let me try to give an answer to the last question, why the strange contradictions and omissions in Nicolaes Witsen’s books are completely overlooked by Ab. As Nicolaes Witsen was an outsider and had to rely for his information on third parties, his deeper understanding of the processes involved building a wooden ship, is very shallow. And the same thing is true for the books of Ab Hoving. As said, to my amazement, the books from Ab about Nicolaes are completely useless when you want a thorough answer to the simple question: what is meant by this writing? Cornelis van Yk sheds some light on this matter. Cornelis starts his book with a dedication to the people in charge of the VOC chamber Delft. But he rewrites this dedication. The difference between these two dedications is significant. In the first version of this dedication he writes: “Dog, staande, gelijk als, op het punct van ’t gezeide Werk by der Hand te vatten, wierdmy, door iemand mijner Vrienden, berigt, dat, zijn Ed: den zeer geleerden, en door naspeuren noit vermoeiden, Heer, en Amsterdams Burgemeester, Nicolaus Witsen, al voor eenige Jaaren, gelijk als niet konnende verdragen, dat aan zo groot Ligt de kandelaar langer zoude ontbreeken, en daar mede genoegsaam de nalatigheid van de respective Bouwmeesters, als met de Vinger, aanwijsende, een notabel, en deze Stoffe aangaande, zeer lofwaardig Boek, onder den Tijtel van Nederlandsche Scheepsbouw en Bestier, hadde in het ligt gegeven.” "But, standing, as if, on the point of beginning the said work, it was reported to me by one of my friends that his noble, very learned, and never wearied by searching, Lord, and Amsterdam mayor , Nicolaus Witsen, already for some years, as he could not bear, that such great light would be missing any longer, and with that showing the negligence of the respective master shipwrights, published a notable, and this matter concerning, a very praisworthy book, under the title of Dutch shipbuilding and management." After this remark Cornelis writes extensively that Nicolaes’s book was sold out and he could no longer buy a copy. But Cornelis changed the first passage to this: “Doch, staande gelijk als op het punct van ‘t gezeide Werk by der hand te vatten,wierd my, door iemand myner Vrienden berigt, dat zijn Ed: den zeer geleerden, en door na speuren nooit vermoeiden Heer, en Amsterdams Burgermeester, Nicolaas Witsen, al voor omtrent dartig Jaaren, een deese stoffe eenigsints aangaande, zeer lofwaardig Werk onder den Titul van, Aeloude en hedendaagse Scheeps=bouw en Bestier: hadde in ‘t licht gegeven.” "But, standing, as if, on the point of beginning the said work, it was reported to me by one of my friends that his noble, very learned, and never wearied by searching, lord and Amsterdam mayor , Nicolaas Witsen, already for about thirty years, published a very praisworthy book, this matter somewhat concerning, under the title of Dutch shipbuilding and management." A very intruiging difference between the two remarks is Cornelis changes "this matter concerning" to “this matter somewhat concerning”. It is not the only place in his book where Cornelis makes remarks in veiled terms about Nicolaes’s book. So, apparently Cornelis was able to, in the end, lay his hand on a copy of Nicolaes’s book. And he concluded the knowledge of Nicolaes was shallow and lacked insight in the fundamental processes concerning building a ship. This is unfortunately mirrored today by the books of Ab Hoving.

-

Hello Waldemar, You bring about quite a lot of stuff in one article. I would like to take one of your remarks and try to say something about that. You state: Firstly, it may be connected with the frame-led method as described by van Yk, rather than with the shell method. Working for years now on the books written by Cornelis van Yk and Nicolaes Witsen I began to wonder if the two ‘methods’ described in both books really are that different? I try to describe each step in the building process by imagining how things are done. Can I come closer to understanding this by trying to describe that? And does this description fit in a greater understanding about the whole building process? I would like to propose first that we try to make a description from the actual activities when building a ship according to the two methods. When I started thinking about that I had the idea not to describe the process from the perspective of the sequence but from the perspective of the procedure. And that is fairing. If you do that, looking at the whole building process from the perspective of fairing, things look quite different. Using the phrases ‘bottom first’ and ‘skeleton first’ over and over again creates some sort of situation as if everybody exactly knows what this means and that everybody agrees these methods are very different from each other. But I am not so sure about this. I am very careful about stating this because I know, or at least suspect, that saying this undermines long-held views and propositions. Which always raises resistance. But I would propose to start with one of the authors, if you can agree with this?

-

Good afternoon Mark, This is quite a fundamental statement indeed. In my opinion negative absolute statements in science are impossible. You cannot prove a negative statement and absolute statements makes a sound and thorough discussion impossible. For me, the very basis of science is a non judgemental approach to the question what the reality around us consists of. And absolute statements are not part of that approach. You state it correctly, an absolute statement provokes an absolute necessity, which makes every discussion superfluous. I think I have shown that there are reasons to suppose, beyond reasonable doubt, technical drawings were made in the seventeenth century Dutch Republic. And it doesn’t matter if you make a distinction between drawings showing the hull shape or the layout of the interior of the ship. A technical drawing is a technical drawing. I am a shipwright and I approach the books of Nicolaes Witsen and Cornelis van Yk from a practical perspective. If I can deliver a description of what is described in those books in a general, understandable and verifiable manner, than that is science for me. To that end I use Hitchens’s razor. According to Wikipedia: “Hitchens's razor is an epistemological razor (a general rule for rejecting certain knowledge claims) that states "what can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.The razor was created by and named after author and journalist Christopher Hitchens (1949–2011). It implies that the burden of proof regarding the truthfulness of a claim lies with the one who makes the claim; if this burden is not met, then the claim is unfounded, and its opponents need not argue further in order to dismiss it. Hitchens used this phrase specifically in the context of refuting religious belief”. Absolute statements tend to cling to religious belief. Can you take someone serious who makes these kind of absolute statements in a scientific debate? Well, I don’t.

-

Hello amateur, Thanks for your remarks and thanks for the drawings! I will try to give a proper reply to your remarks. One of the most striking features of the Dutch seventeenth century is that it was a turbulent age with lots of developments who were not recorded as we would do it now or not recorded at all. The way things were done are also often quite different from the way we do things today. So I am very weary of making firm statements or draw conclusions on the basis of information which is almost by definition incomplete. The books written by Nicolaes Witsen and Cornelis van Yk were the first of their kind in those days. But I think they represent a phase in a more general development. The social structures where knowledge and craft was passed on from generation to generation, the guilds, were lost in the ever growing industrialisation of the Dutch Republic. So the need arose for other ways of transferring knowledge. The invention of the printing press could meet that need. Nicolaes and Cornelis both mention their motivation of writing their book: to record what never has been recorded before (in the Dutch Republic). And that is the crucial understanding I think. Many things are not recorded. And I think this is reflected in the way Nicolaes and Cornelis wrote their respective books. Often you can find statements done by Nicolaes and Cornelis where they say something is done without explaining why. Also definitions or more strict descriptions of certain used understandings often lack. The books of Nicolaes and Cornelis are in that sense representatives of a certain development. This is in a sense also true for the drawings of Pieter van Zwijndregt. The drawings are there, the manuscripts with the design theory and method of Pieter are there but a connection with the actual practice of building a ship lacks. Only in the so-called ‘provisions’, attached to the specifications for a ship to build, you can find some of this information. So, I think most of the assets used on a shipyard to be able to build a ship are lost and so is the knowledge. In the former string of posts I tried to give some examples of this. Concerning Cornelis I try an indirect approach in an attempt to retrieve some of the procedures by trying to regard the whole description of Cornelis as a consistent coherent whole. I am not familiair with this article of Ab Hoving about the seventeenth century drawings. In general I am not impressed by the analytical capabilities of Ab. You mention watermarks. I examined the watermarks in many drawings of Pieter van Zwijndregt (1711-1790) and tried to find some information about these watermarks. I am not an expert, far from it, but what I found is that much information about these watermarks lack, especially in the seventeenth century. What makes watermarks extremely difficult to attribute to a certain era or even producer is the fact many of the producers of this upcoming industry of paper making changed their watermarks, used several watermarks at the same time and were often taken over by competitors who in their own way reused the watermarks or introduced new ones. Even older watermarks were reused again. And I don’t regard Ab Hoving to be an expert on paper. I made a survey on ‘Maritiem Digitaal’ for the seventeenth century drawings but this site functions so badly that its is, for me, often very difficult if not impossible to find what I am looking for, alas. So thanks for the pictures!

-

Hello Waldemar, Thank you for your comment. I can only give a short and incomplete reaction. According to one of the major plates in Rålamb’s book different types of shipbuilding methods were common in Sweden in the seventeenth century. So this seems to confirm your statement. The second remark is also true I think. To be able to build a ship you don’t need a complete drawing. And here it gets complicated. And interesting. So, my remarks are in no way complete nor can they ever be. I will just make a few remarks about the things I have encountered so far. The first remark is about the drawings made in the eighteenth century Dutch Republic. I am convinced most of these drawings were not made to be able to build a ship, they were made during or after building a ship. I have several arguments to back up this claim. One of them is they used to establish the layout of the decks during he building proces as is recorded by the secretary of the Rotterdam Admiralty. This means they could never have made a longitudinal section with a complete layout including the place of all the structures like capstans, galley etc.. This is confirmed by the provision in the specifications for these ships. So, the question is then: what do you need to be able to build a ship from a considerable size? What is the information they used, how did that came about and how was the information translated to the building site? The problem is, there is not one single piece of paper published or written, that I know of, about the actual building practice in the eighteenth century Dutch Republic. The first building stage of a ship concerns the establishment of the hull shape. That is alltogether something different compared to designing the layout of the decks as you rightly point out. So, you need information to be able to do that. Did they make a line plan on scale? I can’t go into detail here but I think they did make a plan on scale, after which the whole shape was translated to a full-scale layout. One of the major problems was: the design methods in the eighteenth century had a serious flaw: they couldn’t use this method to design the bow and stern of a ship. These shapes had to be found by trial and error. The question is, did they find this solution on scale or full-scale? Did they make a scale drawing of the hull in the seventeenth century Dutch Republic? I don’t think so. Just as you say, full-scale tracing on a floor is sufficient to produce the moulds you need to make the parts you need. And the mould was the way they transfered information to the building site. But what was the origin of this full-scale tracing? What was the information they used and how did they construct it? In this matter you see a tremendous gap emerge between the books of Nicolaes Witsen and van Cornelis van Yk. Witsen was 29 or 30 when he published his book. The fact he didn’t know the trade from within is reflected throughout his book. I think in most cases he didn’t have a clue what he was talking about. That is to say, Nicolaes was unaware of the actual process of building a ship, and he certainly had no idea what was important and was not. In a sense this makes his book very valuable from a point of view of information: Witsen just tried to record as much as possible without being able to make a distinction of what is important and what is not. But is is information recorded by an outsider. Cornelis van Yk’s book is a completely different matter. Cornelis was probably about 50 years old when he wrote his book and is mainly concerned with the main issues. His descriptions can be categorized mainly in two types. The first are ratio’s. If the ship has a certain length, the keel has a width and height derived from this length. And so on. The second are procedures. And here it gets interesting. The procedures are responsible for shaping the hull. Some of them are revealed, some of them not. But the essence is they used measurements which were known beforehand in a procedure to produce a shape. One of the most striking examples of this is the rabbet in keel, stem- and sternpost. Cornelis pays a lot of attention to this rabbet as it is in essence the beginning of shaping the hull. For comparison, Nicolaes barely mentions the rabbet. So, establishing the hull shape was mainly done by following certain procedures using certain measurements which were known beforehand. The question is, how did these measurements come about? Did they make drawings to retrieve these measurements from? Or was this done another way?

-

On this forum Ab Hoving declares that in the seventeenth century Dutch Republic drawings weren’t used to the end of building a ship. In his own words: “Draughts were not made in those days, as you know. The '134 feet long pinas' by Witsen is only described in words and sketches in his book”. Is this true? Were drawings not used before they started building a ship in the seventeenth century? Let’s first have a closer look at the statement from Ab. First of all he mentions the ship Witsen describes in his book is designated as a pinas. In my first string of post I showed there is a fair ground for reasonable doubt that Witsen describes a pinas in his book. The data indicate the type of ship tends to be more like a flute like vessel. But the identification of the ship Witsen describes in his book is not my subject now. Ab’s statement is a negative one. So, from a strictly logical point of view, this statement is completely useless. You can’t prove a negative statement. Much more fruitful is the question if evidence can be found they did make drawings in the seventeenth century. Is there? Yes there is. I would like to present two pieces of evidence which directly point to the fact they indeed made technical drawings. The first piece of evidence is a quote from the book of Cornelis van Yk (1697). He states at page 117: “Why the Master Shipwright, to prevent making a mistake, be very cautious and makes a drawing of his whole ship with an open side, and positions all the adequate ship-parts like masts, capstans, stepmasts, bulkheads, hatches, pumps, galley, bottling plant, stairs, gates &c. and gives them their respective places”. What Cornelis describes here is nothing less than a complete design of the interior of a ship. If you want to put every part Cornelis mentions at the right place, you need to know the exact place and number of the beams of the decks. Placing these beams happens quite early in the building process and certainly before anything else is put in place. So you will have to know the exact position of these beams before you can make and place them. And Cornelis urgently advises to make a drawing to that end. Cornelis van Yk makes many more remarks indicating they made use of drawings, but these remarks can not be considered direct evidence, contrary to the above mentioned quote. The second piece of evidence is a drawing in itself. Is can be found in the book from Åke Rålamb, entitled Skeps Byggerij, published in 1691. This is a very interesting little book, mainly a collection of plates, entirely devoted to shipbuilding. The drawing shows several drawing instruments especially designed to make technical drawings. Very interesting are the adjustable pieces allowing you to draw fair lines with different profiles. If they used these instruments in Sweden, they certainly used them in the Dutch Republic. An interesting thing to think about is how drawings were integrated in the building process of a ship in those days? How is information transferred to the building site? And at what moment by what means? Last but not least, I am told that three Dutch seventeenth century ship drawings are kept in the ‘Scheepvaart Museum Amsterdam’. I have never seen them but I am very curious what they show. And what they can tell us about the process they were intended for. Is there anybody who is familiair with these drawings?

-

A critique of the works of Nicolaes Witsen

Philemon1948 replied to Philemon1948's topic in Nautical/Naval History