Jules van Beek

Members-

Posts

56 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Profile Information

-

Gender

Not Telling

-

Location

France

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello Harvey, Thank you for your reaction. To be clear: I would certainly not present someone else's work without attribution. But things were surely different in seventeenth century Holland. Witsen's father was the sheriff of Amsterdam, and Witsen himself studied law in Leiden and graduated as a doctor in law. Still he must not have thought it a crime to present somenone's work without mentioning its author. As far as I know, Witsen never had any legal trouble because of the publication of his book. What he did must not have been considered unlawful, or even unethical, in his time. For me it is remarkable to see that the line "presenting someone's work without mentioning the author is not the same as presenting someone's work and claiming it as your own" jumped out at you. The fact that Hoving accuses Witsen of being a thief and a deceiver, without providing any evidence, does not seem to stir up that same emotion for you. The key point for me is that Hoving claims that Witsen stole his design method from Fournier. A claim for which Hoving provides no evidence, and the evidence I provided proves the opposite: that Witsen did not steal his design method from Fournier. You are not a lawyer, and neither am I, but I think mister Witsen would have the right to sue mister Hoving for slander in the present time. Kind regards, Jules -

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

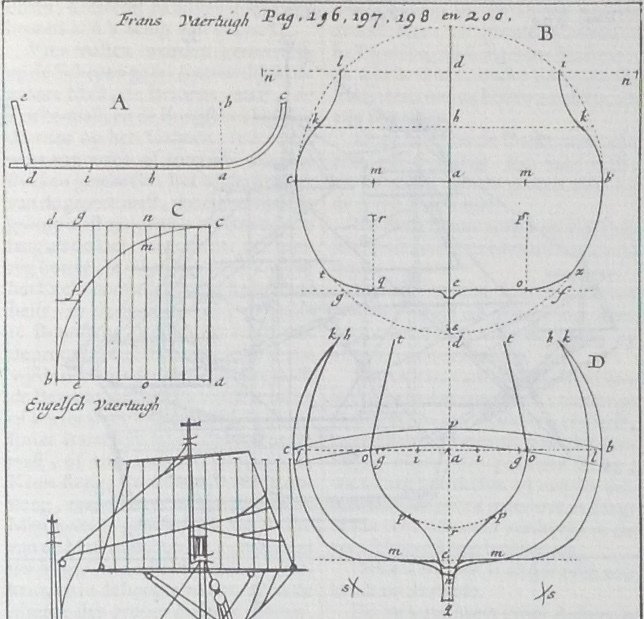

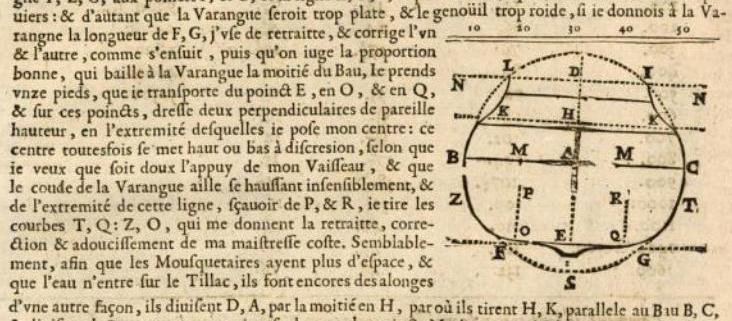

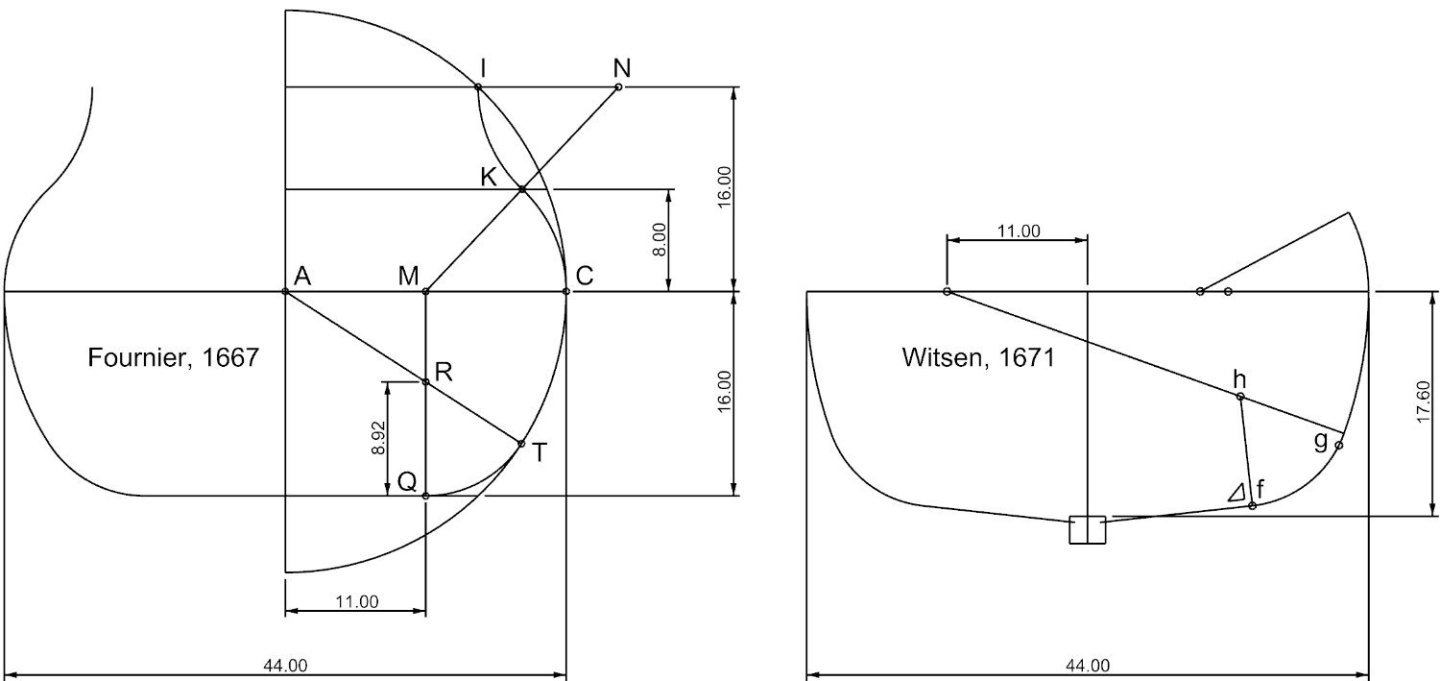

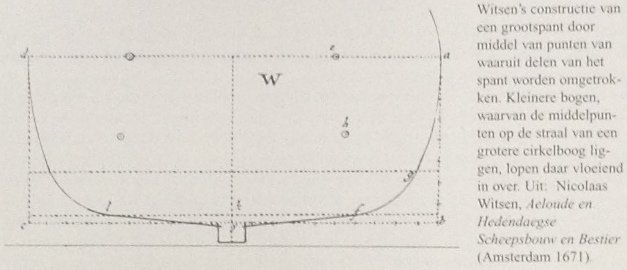

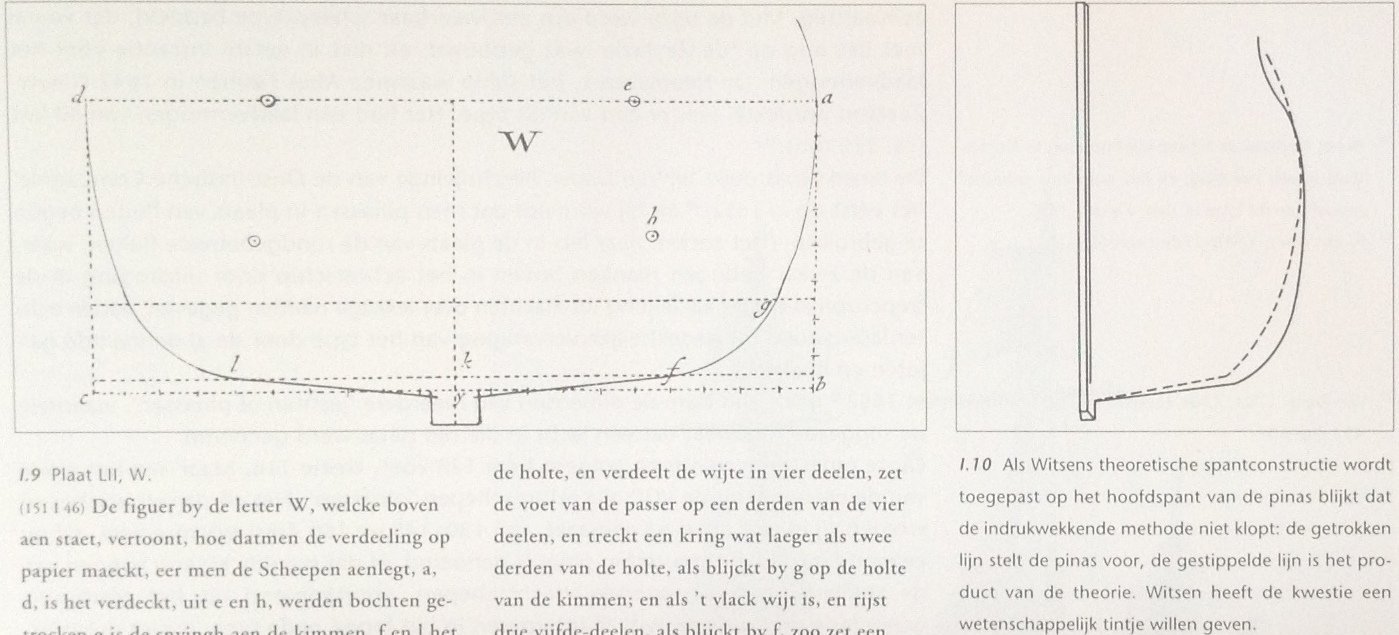

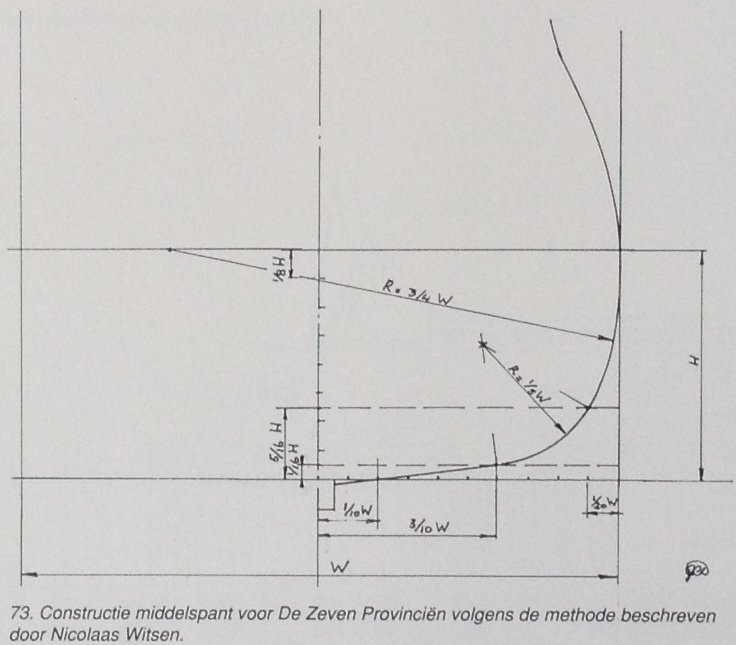

Hello all, Part 3 We repeated in part 1 that Hoving in his book of 1994 claimed that: "It appears that Witsen, who had knowledge of the mathematical methods used elsewhere in Europe, designed this formula himself, out of status considerations, or out of the urge to find explanations for existing phenomenae." And in part 2 we found Hoving's substantiation for his 1994 claim: "Witsen borrowed his mysterious construction of the "Dutch" main frame from Georges Fournier's Hydrographie (1646)" Let's find out if it makes sense to say that Witsen "borrowed" from Fournier; to say that Witsen stole from Fournier. Here is the third part of my critical comments on: Ab Hoving, Dutch Shipbuilding in the Seventeenth Century, in: Nautical Research Journal, 53.1, spring 2008. Witsen and Fournier If I understand correctly, Hoving's reason for claiming that Witsen 'borrowed' from Fournier is that Witsen copied work from Oliveira, Furttenbach and Dudley without mentioning them as his sources, and therefore Witsen must have copied work from Fournier also without mentioning Fournier as his source, and presented Fournier's work as his own. It certainly is true that Witsen copied work from Oliveira, Furttenbach, Dudley and Fournier, but it is also very clear that he did so: Witsen copied the figures from these four authors on his own copper plates and had these printed for his books. Witsen may not have mentined the authors of the original figures, but he did not present the figures of the other authors as his own work either. In all these cases it is very clear that Witsen made direct copies from the other author's work; as Hoving himself says: "on many occasions it is easy to determine that he "borrowed" from other authors". To get more to the point, in the case of Georges Fournier's 'Hydrographie': Witsen names "P. Fournier" on page 4 of his foreword of his book of 1671, Witsen translates Fournier's description of ship design beginning on page 196 of his book of 1671, and Witsen gives four figures of Fournier's 'Hydrographie' on plate LXXXII of his book of 1671. Here are those four copied figures: Witsen, Aeloude ..., 1671, detail of Plate LXXXII, opposite page 198. Witsen's copies of four figures from Fournier's 'Hydrographie'. From this it is clear that there is absolutely no doubt that Witsen copied the work of Fournier. And, although Witsen gives no credit to Fournier in his main text, he does not present Fournier's work as his own work either. But Hoving is making another claim in the case of Witsen copying the work of Fournier as well: Witsen presented the work of Fournier as his own; according to Hoving, Witsen presented Fournier's method for designing the main frame as the method Dutch shipwrights used to design their main frames. Presenting someone's work without mentioning the author is not the same as presenting someone's work and claiming it as your own. Hoving says in his article that Witsen on the one hand copied Fournier's work openly, like he did with the work of Oliveira, Furttenbach and Dudley, but on the other hand stole Fournier's work while claiming it as his own. I think that is an extraordinary claim, a claim Hoving does not substantiate in his article, he just states as a fact that: "Witsen borrowed his mysterious construction of the "Dutch" main frame from Georges Fournier's Hydrographie (1646)." So let's try to do mister Hoving's job and try to find out if it is justified to say that Witsen stole the construction of the main frame from Fournier. While the easiest way to find out if Witsen stole his figure W from Fournier's figure would be to compare the figures of both authors, Hoving does not present Fournier's original figure in his article; he only shows Witsen's figure W. So we have to find Fournier's figure ourselves. Fournier's figure was first published in the chapter "How to trace the main frame of a Ship, in the modern way" of his 'Hydrographie' of 1643. (There is no 'Hydrographie' of 1646 as Hoving claims) That same figure was published in Fournier's second edition of his book of 1667. Here it is: Fournier, Hydrographie, 1667, detail of page 20. We now have all the ingredients to compare Fournier's figure with Witsen's figure W. To make the comparison even easier I made the following sketch in which both figures show a ship with a width of 44 feet: Sketch of Fournier's figure next to Witsen's figure W. Since Fournier does not give information about how the deadrise in his figure was determined, I did not show it in this figure. You can judge for yourself if the figure of Fournier was stolen by Witsen to make his figure W. Allow me to give my opinion though: Fournier using a circle with a diameter equal to the width of the ship is not very Dutch. As Grebber and Witsen show, the diameter of this circle was determined by the distance the second futtock hung from the width of the ship in the bilge. Also, the deadrise Fournier shows in his original figure is not very Dutch: Dutch bottom timbers have flat undersides. For me Fournier using arcs of circles and straight lines, and Witsen using arcs of circles and straight lines can hardly be enough to claim that Witsen stole his main frame design method from Fournier. So my conslusion would be: Witsen did not steal his main frame design method from Fournier. Another question also arises: if we suppose that Witsen stole Fournier's main frame design, why would Witsen have stopped there? There was much more to steal from Fournier: Fournier also explains the method for determining the diminishing of all the other frames, which method Witsen also describes extensively in his book on page 197 and shows in his figure C on plate LXXXII. Witsen could have stolen this method of Fournier also of course, but he decided to not do this. It would have been nice if Hoving would have given an explanation for why he thinks Witsen stole his method for designing the main frame from Fournier; we are left completely in the dark now. Making accusations like these, without providing even the slightest evidence, is really unacceptable. Let's move on ... Why Hoving calls Witsen's method "mysterious" is a mystery to me. If the method is stolen from Fournier, it is no longer a mystery where it came from. And Witsen's method in itself is not "mysterious": Witsen is very clear in the description of his method. I suppose Hoving places "Dutch" between parentheses because he thinks Witsen's method is not Dutch. He probably wants us to believe it's French. Hoving says that it is unfortunate for Witsen that "Dutch shipbuilders did not create geometrical constructions". But Witsen explicitely said they did, so maybe it is more appropriate to say that it is unfortunate for mister Hoving that Dutch shipbuilders did create geometrical frame constructions. It is also unfortunate for mister Hoving that Rembrandt's portrait of master shipwright of the VOC Jan Rijcksen, painted 10 years before Fournier published the first edition of his 'Hydrographie', shows a Dutch shipbuilder creating geometrical frame constructions. To me it seems highly unlikely that Jan Rijcksen also "borrowed" his design methods from Fournier. Hoving saying that Witsen "had to invent a "scientific" system" "that showed no lesser scientific quality than those he found in foreign books and manuscripts" makes no sense to me. Hoving, still in the paragraph "Design of the Main Frame", page 29, II: "Witsen draws a mold, using the shape of already standing futtocks, and these additional futtocks could easily be planed to the right shape if necessary; (Figure 16)". Witsen does not say that he 'draws a mold using the shape of already standing futtocks'. Witsen actually says this about the mold of the futtocks on page 60 of his book of 1671 (my translation): "D the second futtock; which makes the width, and depth of the ship, for example, if one places the mold of the second futtock, put a nail on the depth of the ship, and let a plumb hang down from there, and measure on the bilge how much it hangs from the nail; because the ship is wide over the bilges 27 feet, and has a width of 29 feet over all, hanging from each side one foot. Or if one takes the width 27 feet, and each side hanging 1 foot, gives 29 feet." This text from Witsen shows that he is talking about the main frame, and that the mold of the second futtock is placed before the second futtock is placed itself. Hence the mold is made before the second futtock is made. The "Figure 16" Hoving refers to is a drawing of a mold included in Witsen's book. Hoving's caption for Witsen's mold says: "Figure 16. In his list of tools Witsen depicts a mold, probably for a futtock or a deck beam. It consists of a thin plank, the shape of which can easily be adjusted with a plane." Witsen says this about the mold that Hoving shows in his 'Figure 16' (1671, page 185, I, my translation): "33 A Mold." From this we simply can not tell what this mold was made for. Hoving, still in the paragraph "Design of the Main Frame", page 30, II: "Top timbers formed the upper part of the ship. Their shapes were found with the aid of ribbands, running forward from the stern top timber, which were placed previously." The shape of the first top timbers was obviously not taken from the ribbands; these first top timbers supported the ribbands which were placed against them. The shape of the top timbers was taken from the design. This is clear from the building sequence Witsen presents in his chapter 11 (page 145, I, my translation): "36. Set de Stut-Mallen.", "36. Place the molds of the top timbers", before he mentions: "39. Maeckt Senten om, Schooren en Swiepingen aen.", "39. Place the ribbands around, supports and spalls." And on page 152, I Witsen confirms this by saying (my translation): "When the deck beams are laid, one makes the lower scaffolding on top of the deck beams, ans place the Frame-top timbers ... The top timbers placed, one nails across, and nails supports on the insides, with one end on the deck beam, and the other to the top timber, and then brings ribbands around to determine the run of the upper wales, and then places the other top timbers, ...". So the molds of the top timbers were placed before the ribbands were placed, their shapes could not have been taken form the ribbands. As Hoving confirms himself in his book of 1994, page 110 (my translation): "These top timber molds would not have consisted of much more than planks sawn in curves, but their purpose was clear: this was the moment when the ship above the waterline was shaped." The "stern top timbers" mentioned by Hoving, the top timbers that are part of the transom assembly, were already made in step 9, and placed in step 13 of the building process Witsen describes on page 144 of his book of 1671 (also see Hoving, 1994, page 78 and 82). So their shapes had to be determined very early in the building process. Rembrandt's painting of 1633 shows a design for these 'stern top timbers' on the drawing in front of Jan Rijcksen. Hoving continues: "Conclusion We have tried to depict the method of construction employed by Dutch shipwrights in the seventeenth century. The idea that no well thought-out reconstruction of these ships can be made because of lack of drafts is incorrect. Instead of looking for drafts, the researcher should investigate the building method in use at that time, which can be found in written sources. ...". The big problem with Hoving's depiction of "the method of construction employed by Dutch shipwrights in the seventeenth century" is that it does not depict "the building method in use at that time, which can be found in written sources". Since Hoving discards the design method Witsen so clearly describes in his "written source", Hoving does not describe "the building method in use at that time, which can be found in written sources". We have seen that Hoving discards Witsen's design method on very dubious grounds: by just saying that "Witsen borrowed his mysterious construction of the "Dutch" main frame from Georges Fournier's Hydrographie", without providing any evidence for this assertion. The final result is that Hoving's description of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method is not the same as Witsen's description of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method. To say it differently: in this article Hoving does not describe the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method in the same way as the only valid source for the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method describes it. Hoving's advice to "investigate the building method in use at the time, which can be found in written sources" "instead of looking for drafts", raises a question: why does Hoving oppose these two options of research? Why does Hoving wants us to choose between these two options of research? Why can't we just do both: 'investigate the building method in use at that time, which can be found in written sources' and look for drafts? And there are of course also written sources that combine both, that show 'the building method in use at that time' and show drafts; Nicolaes Cornelisz Witsen's 'Aeloude en Hedendaegsche Scheeps-Bouw en Bestier' of 1671 is an obvious example. Hoving says this in the second part of his "Conclusion": "Model building experiments can compensate for lack of direct experience and enable research into the variety of shapes of seventeenth century ships, as clearly was proven in the Duyfken project. Once on its ways, "the ship practically builds itself, " as the Fremantle shipwright, Bill Leonard remarked. It may seem to be a cumbersome method, but the eventual reward, retracing seventeenth-century Dutch ship shapes, is most satisfying." Well... as we've seen, the "retracing" of the "authentic seventeenth-century Dutch ship shapes" was done on the drawing board, with the help of mister Hoving, before the Duyfken replica was built. This conclude my research into this important Hoving article. I think I am allowed to say that the intention of Hoving's article is to prove that the building method defined the design of the ship; that the use of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method defined the design of the ship. I am afraid I have to disagree: Witsen shows that the design was made on paper, and that the ship was build according to that design by using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method. But, in this article, Hoving strongly rejects the use of any design on paper in the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method, even emphasizing that the reader "need not look for original drafts, because he will not find any". Hoving's conviction that it is impossible to find "original drafts" probably explains his rejection of any prove for the use of these "original drafts" in Dutch shell first shipbuilding. P.S. Although Witsen mentions the use of molds in several cases, Hoving seems to have a strong tendency to reject the use of molds in the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method. My question to you is if we should consider the use of molds in construction as a form of premeditated design. To be continued, Jules -

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

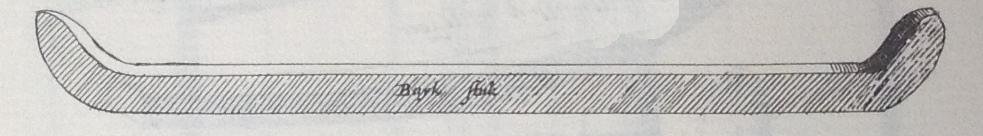

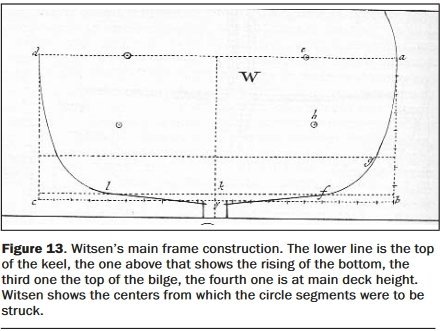

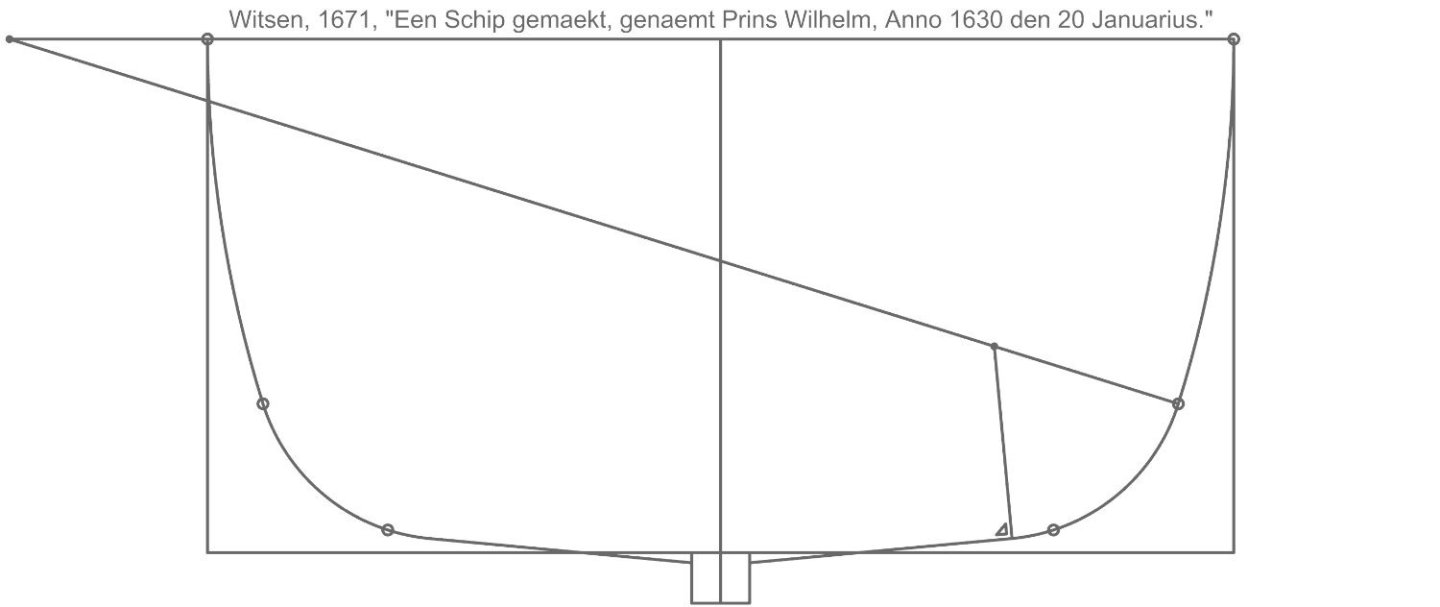

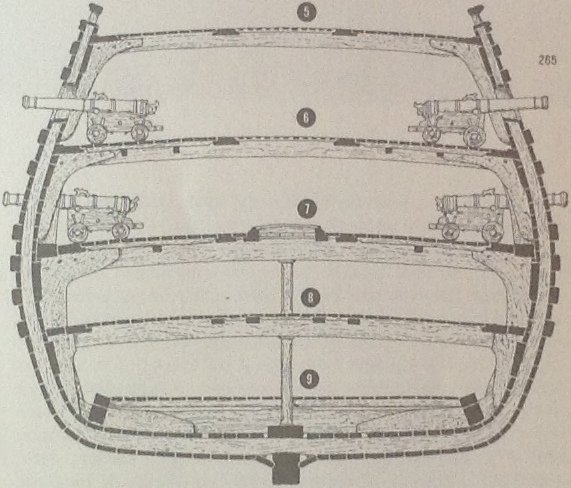

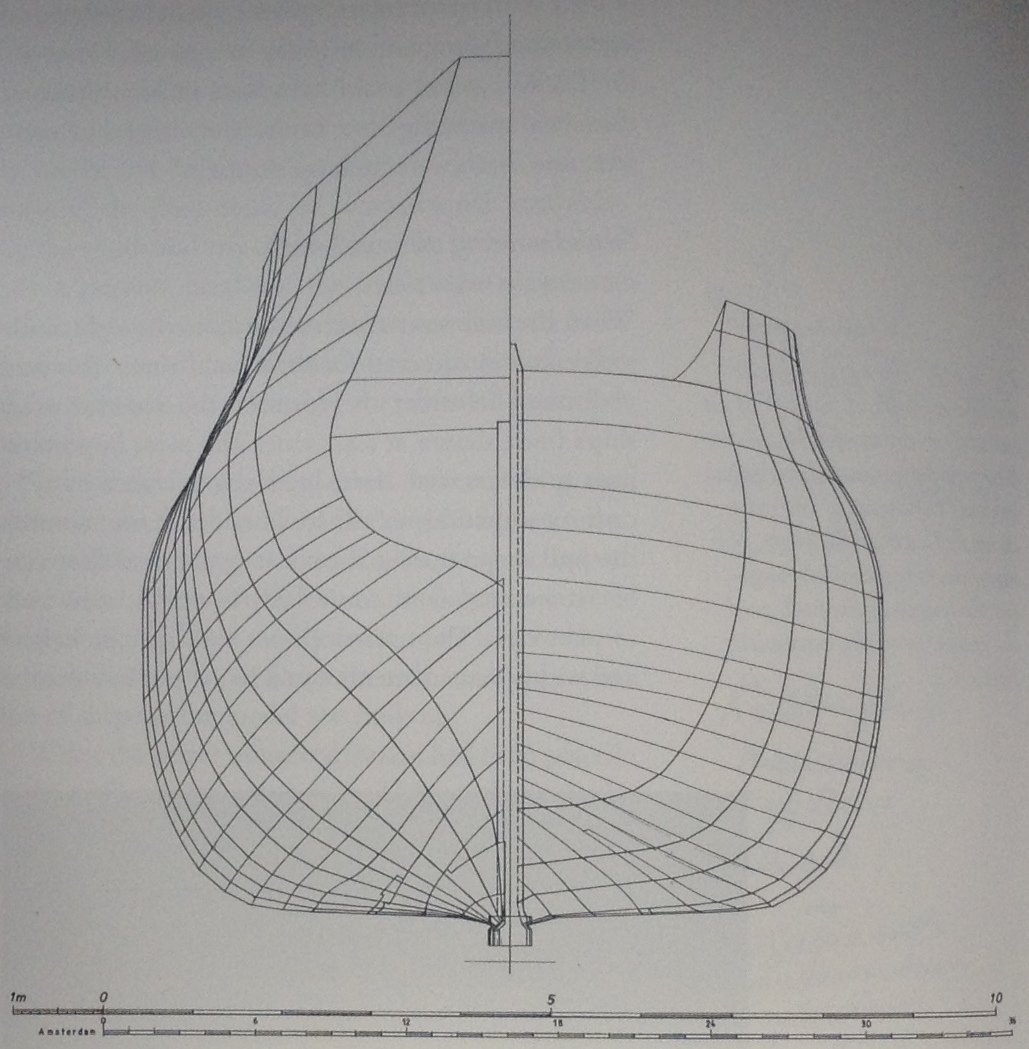

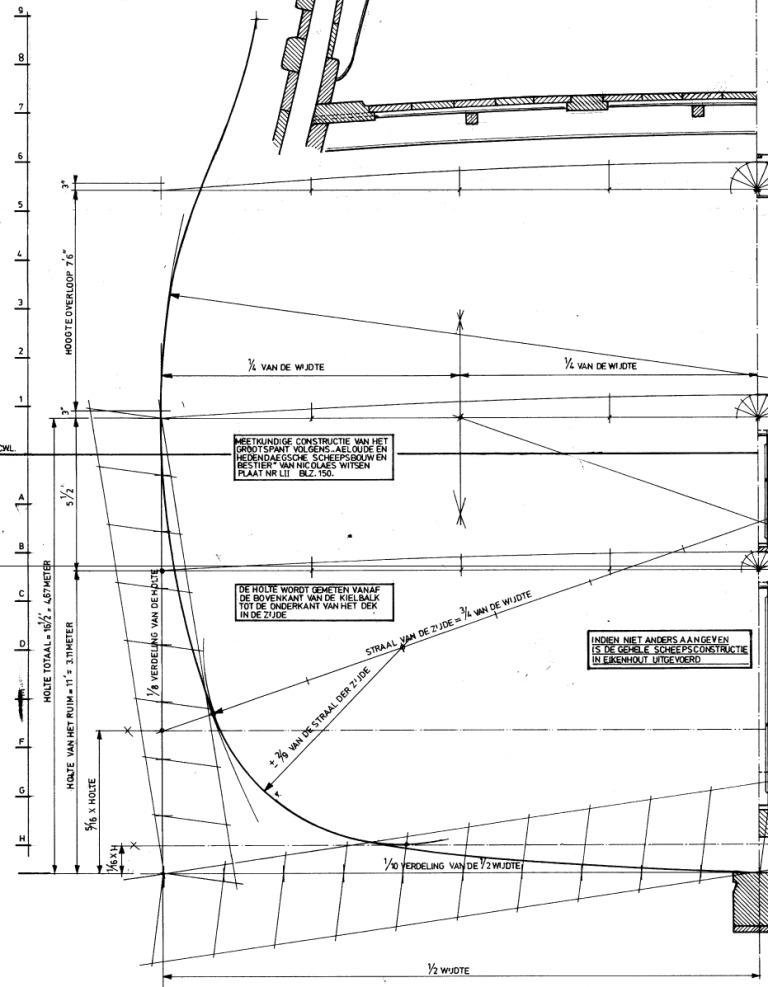

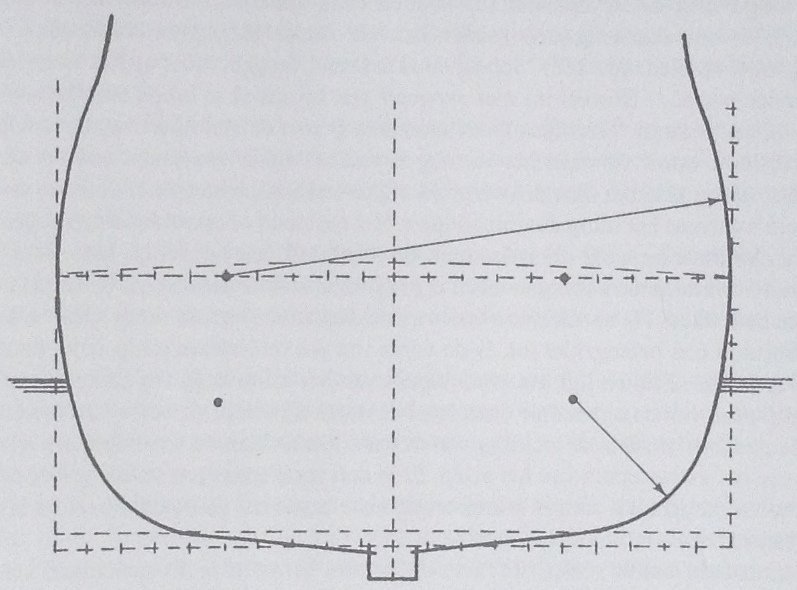

Hello all, This is part 2 about Hoving's article of 2008, the article which holds Hoving's substantiation for his 1994 claim. Here is the second part of my critical comments on: Ab Hoving, Dutch Shipbuilding in the Seventeenth Century, in: Nautical Research Journal, 53.1, spring 2008. Hoving, in the long paragraph "Design of the Main Frame", says this on page 27, II: "Design of the Main Frame The reader must have noticed that a shipbuilder who applied the method described here never saw a ship's frame as an entity. The parts that formed his frames, even the principal frame, were installed individually into the hull during the building process and never formed isolated shapes that could be identified as frames. As we saw, the buikstuk that reinforced the bottom was fitted after the bottom was built and its shape was copied from the inside of the bottom." The 'shipbuilder who applied the the method described here' did see the ship's frame as an entity: on paper. What Hoving calls the 'principal frame', which I guess is the main frame, is shown by Witsen in his figure W. We must remember that Hoving claims to show the Dutch shell first shipbuiding method as described by Nicolaes Witsen in this article, and since Witsen clearly shows that a design of the 'principal frame' was made on paper, Hoving should mention this. That the shape of the buikstuk was determined by the shape of the bottom, and not by the design on paper, has to be contested: Witsen shows us that the bottom did not shape the buikstuk, but that the buikstuk shaped the bottom: the shape of the buikstuk was predesigned on paper. And, as we've seen, when Hoving built his model of the '106-foot long war-yacht' he did not determine the shape of the buikstuk by taking the shape of the bottom he had built, but by taking the shape of the buikstuk of the preliminary design he had made. Witsen shows how the shape of the buikstuk was determined on paper in his figure W, and also shows an isolated buikstuk on plate XXVI (between pages 56 and 57) of his book of 1671: Witsen, Aeloude ..., 1671, Plate XXVII, 'Buyk stuk'. Bottom timber. Hoving continues: "It is true that the shape of the two sitters at each side of the bottom seems open to free choice but, if we realize that the formula stipulated that for every ten feet of ship's length the width of the bilge was one inch less than the total beam and its height was one tenth of the depth, then we realize that there was not much room for variation." Witsen in his figure W clearly describes how the flat and the bilge, and how the bilge and the side of the ship should be designed smoothly. I would not say there "was not much room for variation" in the choice of the width of the bilge, so I think we can say that "the shape of the two sitters at each side of the bottom" was "open to free choice". Witsen also clearly shows in his figure W how the shape of these two sitters was chosen: by using a pair of compasses: the shape of the sitters was an arc of a circle. The height of the bilge being 'one tenth of the depth' must be a misprint; it should read, according to Witsen, 'approximately one third of the depth'. Hoving continues: "Once the bottom and bilges were constructed and reinforced with frame sections and ceiling, additional futtocks were erected on top of the structure and a very important temporary mold, the scheerstrook (master ribband), was fitted to connect their tops." Hoving does not say how the shape of these 'additional futtocks' was determined. Witsen shows in his figure X that the second futtocks were shaped according to the design of the main frame made in figure W, and, as we've seen with Lemée (2006), Witsen talks about molds for the second futtocks; we will get to that soon, again. Hoving, still in the paragraph "Design of the Main Frame", on page 28, I: "The decision about the shape of the main frame was separated into different stages, therefore allowing last minute modifications to the shape of the hull. That is why it is so odd that Witsen draws a complicated construction in his book to show how a Dutch shipwright constructed his main frame. (Witsen 1671, Plate LII, W, Figure 13)." Hoving can not simply claim that "the decision about the shape of the main frame was separated into different stages" because his article does not in any way show that "the decision about the shape of the main frame was separated into different stages." And, again, Witsen shows the contrary, Witsen shows that "the decision about the shape of the main frame was" not "separated into different stages": "the decision about the shape of the main frame was" made before the building of the ship started, on paper. I would not say Witsen's figure W shows "a complicated construction" as Hoving claims. I hope I have shown in earlier posts that it is very easy to apply Witsen's design method as shown in his figure W. The "Figure 13" Hoving refers to is Witsen's figure W, no more, no less. Here it is with Hoving's caption: Hoving presents Witsen's figure W without its context, again. Hoving decided to not show the figures V, X, Z and AA that follow Witsen's figure W; the figures that explain how the design shown in figure W was incorporated in the build of the ship. Hoving continues: "This interesting construction has been the source of many misunderstandings. Many researchers have tried to connect Witsen's drawing to data from building contracts, painstakingly looking for the points from where Witsen's curves had to be drawn, and totally ignoring the question of the actual validity of his 'method'. If the shape of the main frame indeed was the product of a geometric construction, what would be more obvious than presenting the length of the radii in the contract or, at least, the exact location of the points from which the arcs had to be struck? As in the case of the design of the stem, not even the vaguest reference to the use of compasses can be found in a single contract." I dot know which researchers Hoving refers to, but a lot of researchers have passed in my last posts and I do seem to remember they were 'painstakingly looking for the points from where Witsen's curves had to be drawn'. To name but two of these researchers: Dik and Blom. That many researchers seem to ignore 'the question of the actual validity' of Witsen's 'method', as Hoving says, can be easily explained: there is no reason to 'question the actual validity' of Witsen's method. I already explained in an answer to a question from Amateur in an earlier post that I would not expect design specifications in a contract: it makes the customer responsible for the functioning of the design. Customers defining radii and 'points form which the arcs had to be struck' would probably have to be qualified shipwrights themselves. Hoving's "not even the vaguest reference to the use of compasses can be found in a single contract" would imply that the customers should define what design equipment should be used by the shipwright; these customers must have been very rare. I do not know if it was usual to include information about 'points from which arcs had to be struck' or about 'the use of compasses' in contracts for ships built with other building methods than the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method though. Maybe a forum member can help here and show one of these contracts. Hoving continues: "Picking an arbitrary contract to see what actually was written about the shape of the main frame - for instance, the contract for "a Ship named Prins Willem, Anno 1630 den 20 Januarius" (Witsen 1671, 106) - we read: "The bottom is 24 feet wide, rises 9 inches, the bilge 5 feet 4 inches high, 33 feet wide. The futtocks end at the top 2 feet beyond the bilge." This ... Did the shipwright need paper and compasses? No, on the contrary, using compasses and trying to find the points from which the radii should be struck is only misleading and deceptive. Does the entire wording of the contract give the impression that all these data play a role in a geometrical construction? Certainly not, the data are scattered over the contract, which usually was written in an order that followed that of the actual building process." Let me remind you of what Hoving said in 1994 about Rembrandt's portrait of master shipwright of the VOC Jan Rijcksen using paper and compasses in 1633: "The paper in the hand of the master builder shows the graphic representation of what usually can be found in a written contract." It looks like Hoving is rejecting his own vision of 1994 now, in 2008, but that does not mean that his vision of 1994 is no longer valid. As we've seen in an earlier post: Rijcksen is clearly making technical drawings and he built his ships with the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method. About Hoving's the "data are scattered over the contract"-argument; in the case of the contract Hoving chose, the contract for 'Prins Willem' of 1630, the data are not scattered over the contract; as Hoving shows himself: the data are given in two consecutive sentences. And yet, even if the data was scattered over the contract, Hoving, as we've seen, used this same data to make a 'geometrical construction' before he started to build his models of the 'Speeljacht' and the '106-foot long war-yacht', making it even more likely that the 17th-century shipwright did the same. For those who doubt if the information given in the contract of the 'Prins Willem' of 1630 is sufficient to make a design of the main frame, here is that design, made according to Witsen's design method: Design of the main frame of Prins Willem, 1630. First the arc of the second futtock is drawn, then the arc of the lower futtocks is drawn, then the line of the flat is drawn from the keel tangent to the arc of the lower futtocks: two arcs and a straight line, smooth transitions. I dare to declare that I have not been "painstakingly looking for the points from where Witsen's curves have to be drawn". And then we get to the part of the article which holds Hoving's substantion for his 1994 claim, so I feel the need to give an extensive excerpt of Hoving's text here: Hoving, still in the paragraph "Design of the Main Frame", says on page 29, I: "But why did Witsen depict his geometrical method, captioned with the text: "how the division on paper is made, before the ships are built"? We must realize that Witsen did not write his book as a shipbuilder's manual. His purpose was to concentrate all the knowledge about shipbuilding available in his time into one book, and he took material and inspiration from a handful of earlier scholars, whose books he found in the Vossius Library at Leiden, where he studied law. On many occasions it is easy to determine that he "borrowed" from other authors without bothering to mention his sources. The sequence of drawings in the chapter "How Ships Were Built for a Hundred and Fifty Years" was copied entirely from Fernando Oliveira's O Livro da Fabrica das Naus (circa 1580) The drawings for the construction of galleys are copied from Joseph Furttenbach's Architectura Navalis (1629). The sections of English ships in plates LXXXIII and LXXXIV originate from Robert Dudley's Arcano dell' Mare (1646) and Witsen borrowed his mysterious construction of the "Dutch" main frame from Georges Fournier's Hydrographie (1646). Witsen was a scientist, looking for a representative main frame construction that showed no lesser scientific quality than those he found in foreign books and manuscripts. Unfortunately for him, Dutch shipbuilders did not create geometrical frame constructions. Their main frame shapes were generated organically from the traditional handicraft method of construction they employed, which is why Witsen had to invent a "scientific" system." According to Hoving, Witsen did not write his book as a shipbuilder's manual. But, Witsen's description of the design of the main frame and his figure W are placed in Witsen's chapter 11, which is called "How the ship's parts are assembled thereafter", and that chapter clearly talks about all the consecutive building steps of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method. This chapter 11 can actually be read as a shipbuilder's manual. Hoving himself used Witsen's chapter 11 as the foundation for making his description of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method in his book 'Nicolaes Witsens Scheeps-Bouw-Konst Open Gestelt' of 1994, and for this article of 2008. And then we come to Hoving's substantiation for his 1994 claim: "Witsen borrowed his mysterious construction of the "Dutch" main frame from Georges Fournier's Hydrographie (1646)." Let's find out if it makes sense to say that Witsen 'borrowed' from Fournier; to say that Witsen stole from Fournier. To be continued, Jules -

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

flying_dutchman2 reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Mark P reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Mark P reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Mark P reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Mark P reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello Druxey, Thank you very much for your interest. To me it is surprising that all this has become controversial. The commonly held view in the Netherlands used to be that Witsen, being the only valid source we have on Dutch shell first shipbuilding, had to be taken at face value. Now this is no longer the commonly held view. With my posts I am trying to trace where this new view came from, and how it spread across the nations. As you can tell, my research has progressed up to 2008 already, only 15 more years of publications to deal with. The conclusion of my research will be published on this forum, in due time. To finally answer your question: no, I have not submitted my 'thesis' for publication in the Netherlands or the U.K. Hello Marcus, Thanks for seconding Druxey, but I am afraid I have to disappoint you: there is no thesis or dissertation on the above information. You could say I am writing and publishing my 'thesis' on this forum. I am afraid you will have to stick to this forum to read the complete 'thesis'. To be clear: what I am writing here are my own opinions which are based on my own research; it is my own original work. This of course also means that I am the only one responsible for what I say here. I will keep your request for a bibliography list in mind. If you want to know more about a specific article, just let me know, I will certainly try to give you more information. Thank you both again, Jules -

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Doreltomin reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

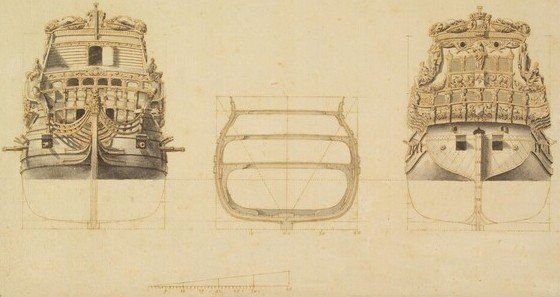

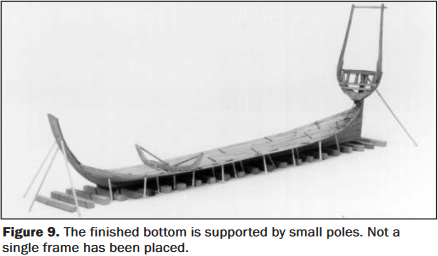

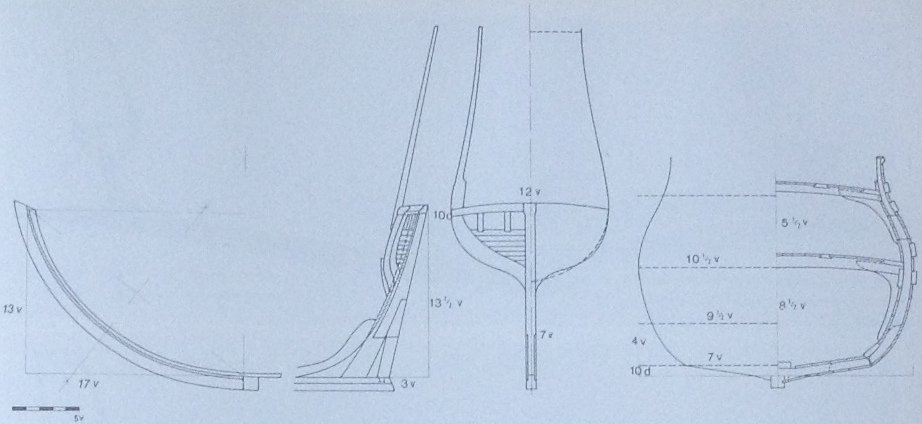

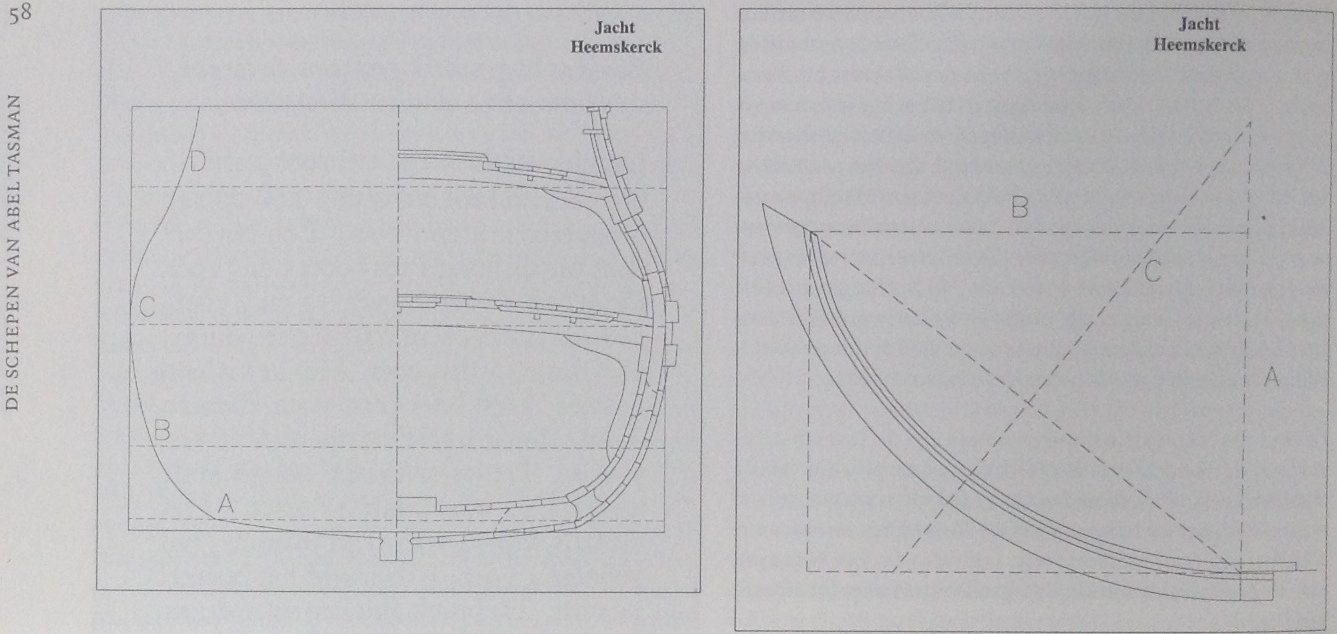

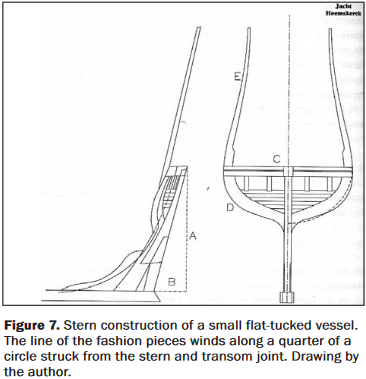

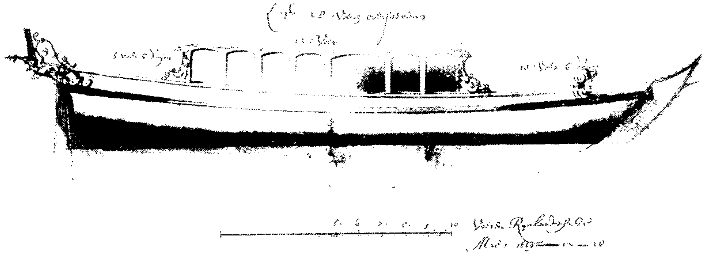

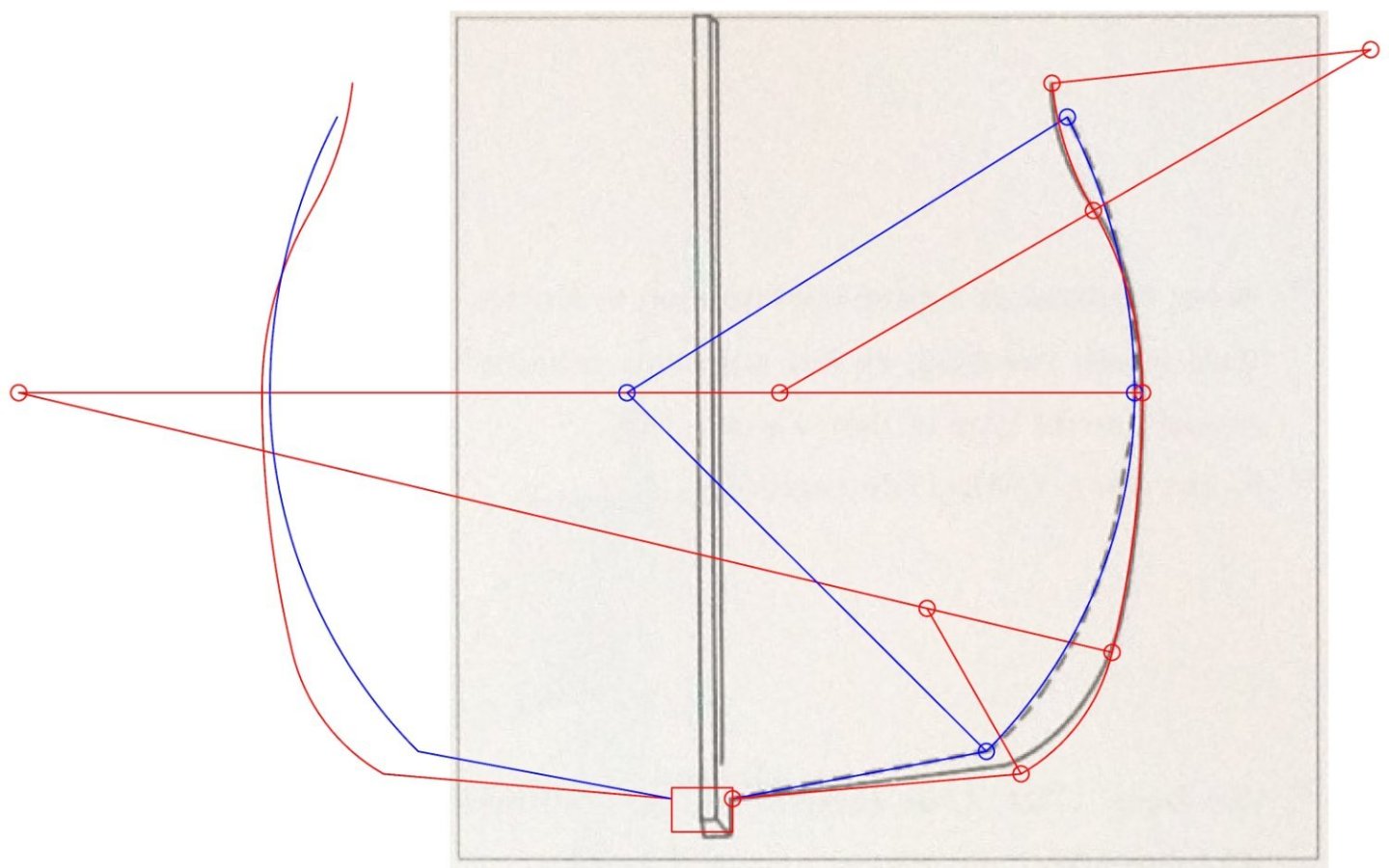

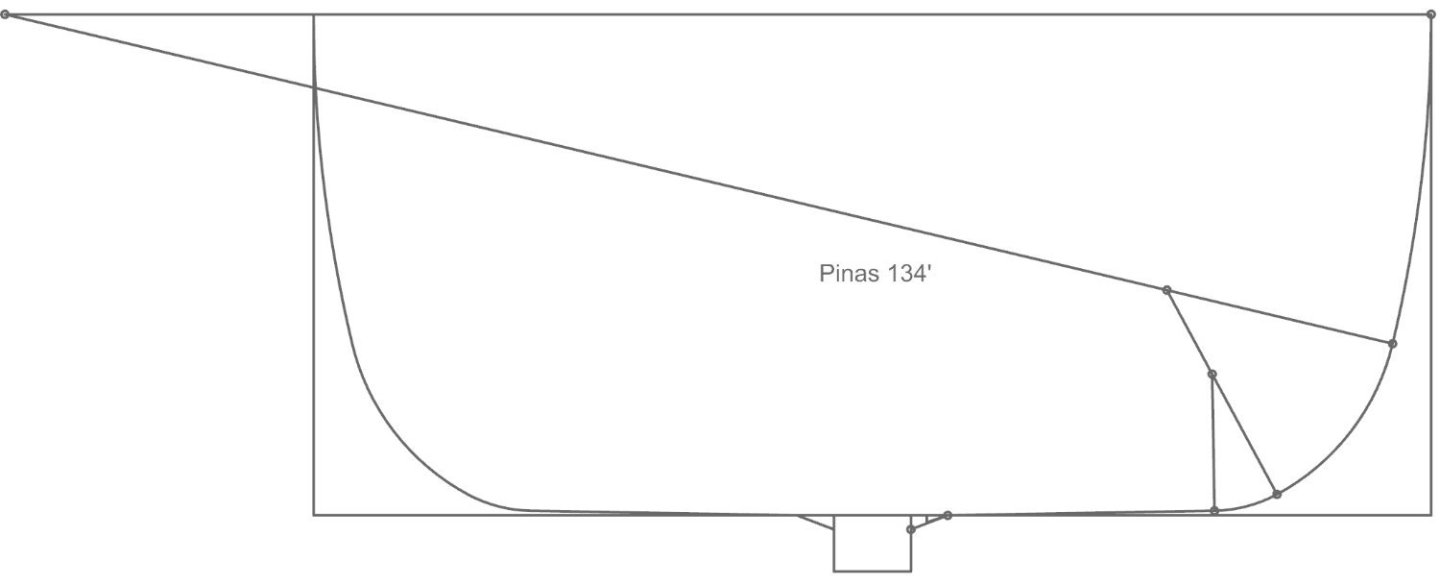

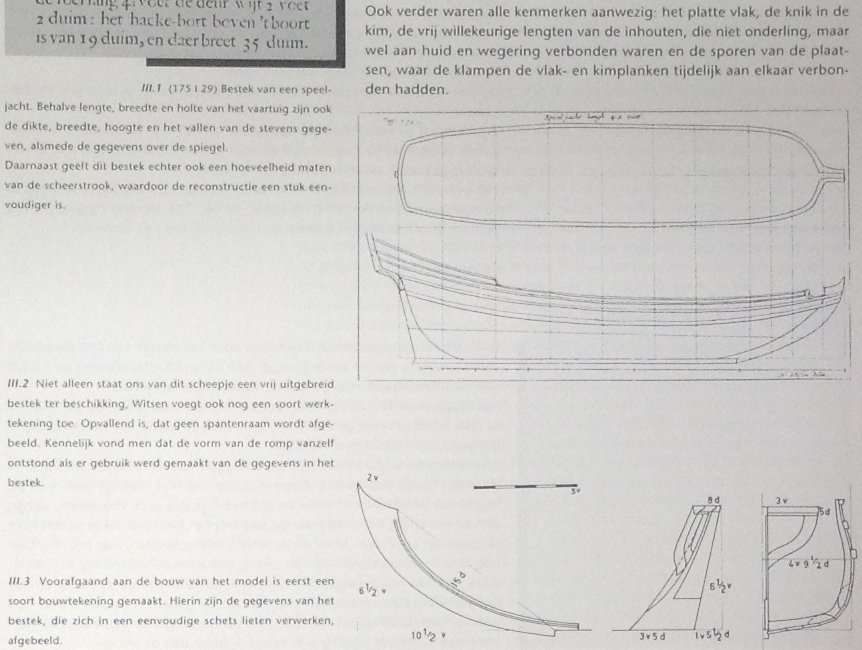

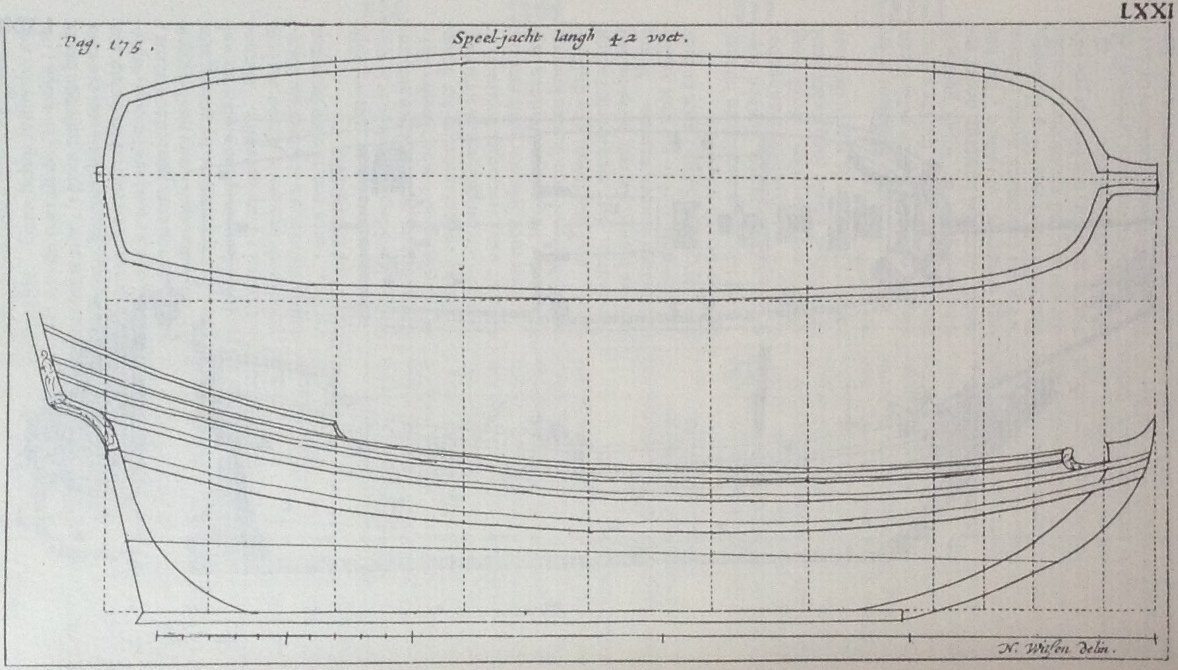

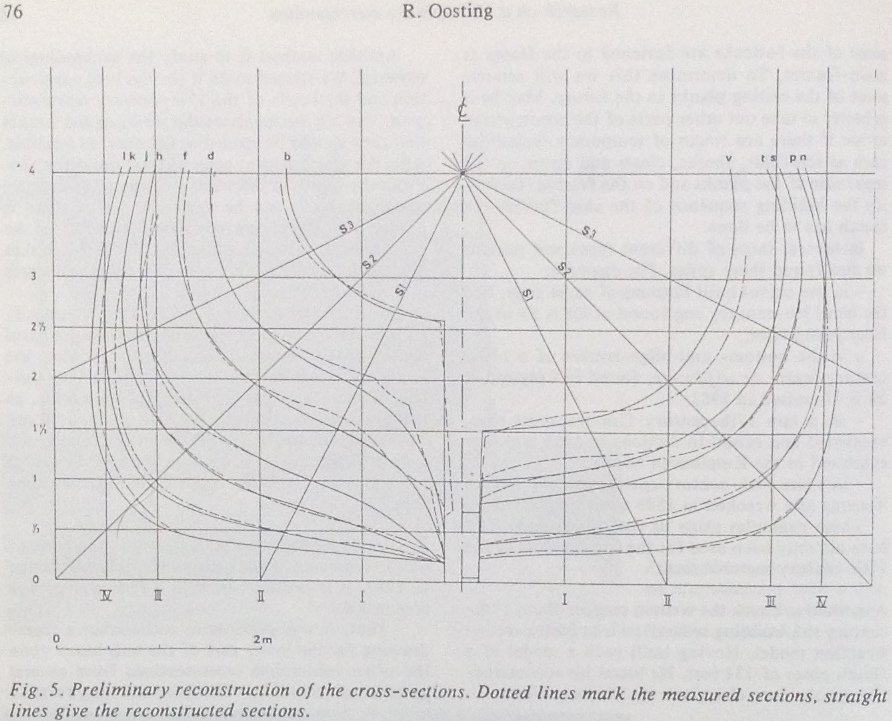

Hello all, Thank you flying-dutchman2. We have already seen that A.J. Hoving in his 'Nicolaes Witsens Scheeps-Bouw-Konst Open Gestelt' of 1994 rejected Witsen's design method for the main frame because applying Witsen's design method to the main frame of Witsen's example pinas of 134 feet did not result in the same design as Hoving made for the main frame of Witsen's example pinas of 134 feet. We have already seen that this argument for rejecting Witsen's main frame design method is not valid. It is very well possible to make a valid design of the main frame of Witsen's example pinas using Witsen's main frame design method. We have also seen that Hoving gives a second reason for rejecting Witsen's design methid for the main frame in his book of 1994: "It appears that Witsen, who had knowledge of the mathematical methods used elsewhere in Europe, designed this formula himself, out of status considerations, or out of the urge to find explanations for existing phenomenae." As we've seen, Hoving did not substntiate this claim in 1994, but we will see that in the next article, in 2008, Hoving will substantiate his 1994 claim. Let's have a look. Ab Hoving, Dutch Schipbuilding in the Seventeenth Century, in: Nautical Research Journal, 53.1, spring 2008. Hoving starts his article, unsurprisingly, with an introduction. Here are some lines from that introduction. Hoving, page 19: "The enormous prosperity that characterized the seventeenth century in the Dutch Republic led to the fact that in Holland the period is generally called the "Golden Age". The products of the Dutch shipbuilding industry, which were very popular, both in the Republic and abroad, in part led to this prosperity. ... One might say that anyone who wants to study northwest European continental shipbuilding history should start in Holland." Hoving says this in his paragraph "Shipbuilding as a handicraft" on page 20: "Our engineering mindset is barely capable of imagining a handicraft building process in which design on paper was both unnecessary and not deployed. Anyone wishing to build a seventeenth-century ship nowadays (regardless of the scale) need not look for original drafts, because he will not find any. He wil have to try to comprehend what the handicraft of a shipbuilder of the era was all about." I admit, I have an engineering mindset, but that does not mean that I can not read what Witsen says in his books; on the contrary I would say. When Witsen says design on paper was deployed, design must not have been unnecessary. In my opinion you need both: understanding of the "handicraft building process" and understanding of the design process. The limits of the handicraft determine the limits of the design; they are unbreakably linked; as any engineer will tell you. I am not sure why Hoving states that it is impossible to find "original drafts". For reasons I have already explained I consider the drafts in Witsen's books to be "original drafts". Hoving of course knows the drafts in Witsen's books very well, and, as we've seen, has used Witsen's drafts to build his models. So why doesn't he consider Witsen's drafts to be "original drafts"? And I have shown a couple of, what I consider to be, "original drafts" of the Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam already in previous posts, and these can be found on the internet easily now. Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam, A.0149(0864). "Seek and ye shall find", but first you should be willing to find. Hoving, in the same paragraph "Shipbuilding as a Handicraft", on page 21, I: "But how about a shipbuilder? Was it possible to build a complete ship, complying with all wishes and demands of the period, without even making at least some simple calculations? With no drafts or blueprints? Yes, it was possible! And almost every time it worked out well. The aim of this article is to describe and elucidate the process of ship design and construction in Holland during the seventeenth century." This is the wrong question to start with: the point is not if it is possible to build a ship 'with no drafts or blueprints', the point is if a Dutch shipbuilder of the seventeenth century using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method used 'drafts or blueprints' to build a ship. I think Witsen's books show us the Dutch shipbuilder did. I also think Rembrandt's painting of Dutch shipbuilder Jan Rijcksen of 1633 shows us he did. Hoving then continues by naming his sources for his article. He names: "Pictorial sources ... Archaeological sources ... Literary sources ... Experiments ... The Proportional System ... The Functions of Ship types ...". Obviously Hoving ignores the Dutch seventeenth-century technical drawings of ships; for example those in Witsen's books, or those in the Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam. For obvious reasons I guess; as seen, Hoving said earlier in his article that these drawings can not be found. Hoving, page 21, II: "Literary sources Almost everything we know now about the construction of seventeenth-century ships originates from just a few books, written in the second half of the century. The oldest is Aeloude en Hedendaegse Scheepsbouw en Bestier ..., written in 1671 by the Amsterdam diplomat, collector, naturalist, and Lord Mayor Nicolaes Witsen (1641-1717). ... Nevertheless it contains a mass of useful and most reliable observations, even though Witsen was a patrician and certainly not a sailor or shipbuilder." Again the combination of the claim that Witsen is an excellent source and at the same time ignoring part of what Witsen writes. While Hoving says here that all we know originates from a few books, and says Witsen's work contains "most reliable observations", and claims on page 21 that the aim of his article is to "decribe and elucidate the process of ship design and construction in Holland during the seventeenth centry", Hoving chooces to ignore Witsen's description of ship design. Hoving, page 22, II: "Experiments Doing research into shipbuilding methods without some kind of practice is a useless affair. The notion that the method for building was mainly responsible for the design of the ship forces us to undertake the same steps the shipbuilder did in his time to get the desired end product and to do research with woodworking tools in our hands. Thus model building experiments are an important component within the research into Dutch shipbuilding." If you think it is importatnt to "undertake the same steps the shipbuilder did in his time", then please do "undertake the same steps the shipbuilder did in his time". Witsen shows us that one of these steps was to make a design of the main frame before the building of the ship started; which Hoving prefers to ignore here, again. Hoving continues: "Much more interesting are the possibilities offered by projects of creating full-size replicas of Dutch ships, provided the construction team can be induced to add an axperimental aspect to their project and build the ships in the same way as the original vessels. This possibilty led to great efforts to duplicate early practice in the building of the Duyfken (1606) replica in Australia." The builders of the Duyfken replica may have succeeded in duplicating the "early practice in building", but they certainly did not succeed in showing that it was possible to build the Duyfken replica without prior design, as Hoving is implying here. Duyfken So let's find out if the Duyfken replica was built without prior design. Hoving says this about the design of the Duyfken replica in: Hoving & Emke, Het ship van Willem Barentsz, 2004, page 39 (my translation): "Early in the preliminary research into the build of the ship, the team contacted the Netherlands, which resulted in a long correspondence between the leader of the research team, Nick Burningham, and me. There was little I could offer him. ... Nevertheless it is remarkable that the master shipwright, the Englishman Bill Leonard, with much confidence, without the support of a construction drawing, with not much more than his enthusiasm and the experiences of a couple of model builders, dared to build the ship in the way it was done four centuries ago." And this is what Hoving's correspondant, archaeologist Nick Burningham, said about the design of the Duyfken replica in his article "An update on the Duyfken Project" in the Maritime Association Journal, Volume 8, No. 3. Sptember, 1996, page 13: "Our research to design the ship needed to be thorough, and equally importantly, had to be seen to be thorough by the experts in the Netherlands and elsewhere. In communicating with those experts it became clear that none of them had a complete picture of what the design should be. At an early stage Ab Hoving from the Rijksmuseum was warning me "everything before 1630 is pre-history". There are certainly no plans of any Dutch ship built at the time of DUYFKEN because plans on paper were never used. The ship's plan was in the head of the master shipwright. We hope to recreate the authentic process of building a late 16th-century ship but it is very unlikely that we can recruit a late 16th century shipwright whose memory is reliable, so we do need to reconstruct plans, in detail, on paper. ... We have sent copies of our drawings and a paper summarizing the research to our expert contacts in the Netherlands and the response has been favourable. No one can say: "Yes, this is definitely correct." but the quality of the research and some new understandings have received definite approval. The design has also been tested using computer hydrostatic modelling: the results are encouraging. ..." Hoving claiming that the Duyfken replica was built "without the support of a construction drawing" in 2004, does not seem to be supported by what Burningham says in 1996, before the actual building of the Duyfken replica started. Burningham's statement that "plans on paper were never used" in Dutch shell first shipbuilding was probably based on information provided by one of the "expert contacts in the Netherlands". Hoving, in his paragraph "Building a Ship - Keel, Stem, and Stern", says this on page 24, I: "The shipbuilder needed no draughts to create the shape of the stem either. ... With our engineering mindset it is very easy to make incorrect assumptions. To us it seems most obvious that a pair of compasses (or a piece of rope, fixed at one end) was used to draw every curved shape necessary in shipbuilding, especially if the shape comes so close to an arc of a circle, as it does in the case of the stem. ... It is most questionable that compasses were used like that in actual shipyard practice." It looks like Hoving is saying that a design can only be made with a compass: if the resulting shape is not an arc of a circle it can not have been designed: if no compass was used, no design was made. Some Dutch seventeenth-century technical drawings show another method for capturing the design of a stem post without using 'multi-meter-long compasses', as Hoving suggests in his article; we have for example this technical drawing of the 'Statenjacht' we have seen in an earlier post: Detail of the technical drawing of a 'Statenjacht'. Scheepvaartmuseum, Amsterdam, 2015.4375. (Drawing authenticated by the RCE) The drawing shows a method for capturing the curve of the stem post without using a pair of compasses. And, Rembrandt's painting of 1633 shows master shipwright Jan Rijcksen with two designs of a stem post on paper. And, Witsen shows in his figure W of 1671 that arcs of circles were used in design; in the design of the main frame. And, Lemée shows that arcs of circles were used in the design of the Dutch wreck B&W 5. And, if we consider Ralamb's design drawing of a 'boeier in the Dutch way' of 1691 to be a Dutch design, we see a lot of arcs of circles were used in Dutch design. (For more information see the thread 'Ralamb's boeier' in the 'Discussions for Ships plans'-section of this forum.) Hoving, in his paragraph 'Bottom and Bilges", says this on page 26, I: "The "rising" in the longitudinal direction seldom was specified in the contract because it was left to the shipbuilder's experience. In practice, very little can go wrong if the correct bottom rising is combined with the correctly planned shape of the stem and the stern. Wood is a material that can be deformed to a considerable degree but, within the parameters of the contract, the possibilities were very restricted. Also the experience the shipbuilder had with previous projects helped to stay within the contract's margin. (Figure 8)." This leans on the principle that the building material will decide on the limitations of the design. And although this principle is sound of course, in the case of wood the limitations are so far away from the desired shape that these limitations can not be used to make a design for a ship. Heated wood can become very plastic, and can be bent in unusable shapes for shipbuilding, or for ship model building. As the following picture shows: Bent wood. The material, in this case heated wood, will not help in making design choices, the shipbuilder needs to make the design choices. Figure 8. A 106-foot long war-yacht. The "Figure 8" Hoving refers to in the main text of his article is a picture of a step in the building process of a model of a "106-foot long war-yacht". In the caption of that "Figure 8" Hoving says: "Figure 8. Keel, stem and stern construction of a 106-foot long war-yacht. (All photographs by the author, unless stated otherwise.)" Hoving uses nine pictures of the building steps of this model of a "106-foot long war-yacht" to illustrate his article. Here is one of them, "Figure 9": The nine pictures of the model Hoving uses to illustrate his article have a long history, which, as far as I can tell, started in 1994. Allow me to elucidate. 1994, 'De Brack'. In his book of 1994 Hoving included a chapter named "III.3 Modelbouw als methode van onderzoek", "III.3 Modelbuilding as a method of research". One of the projects presented in this chapter is the building of the model of the yacht 'De Brack' of 92 1/2 feet of 1631. Hoving uses thirteen pictures of the building steps of this model in his article, and numbered them III.20 to III.32. The caption of the last picture, III.32, mentions (page 267, my translation): "The charter was used for the reconstruction of the war yacht the 'Heemskerck', with which Abel Tasman discovered New Zealand in 1642." So Hoving had transformed the yacht 'De Brack' into the war yacht 'Jacht Heemskerck'. For the building of his yacht 'De Brack' a.k.a. 'Jacht Heemskerck' Hoving made preliminary design drawings. He published them on page 263 of his book of 1994. Here they are: Hoving, Nicolaes Witsens Scheeps-Bouw-Konst Open Gestelt, 1994, detail page 263, figures III.17, III.18 and III.19. Preliminary design drawings for the yacht 'De Brack' of 92 1/2 feet. From the caption of figure III.17: "Where it crosses the vertical A, the foot of the compass is placed, and the stem post circled." And this is what Hoving says about the use of these design drawings in the building of the model of 'De Brack' a.k.a. 'Jacht Heemskerck' (page 262, my translation): "After the placement of the posts, the bottoms was laid. With the gained experience building the pinas and the 'speeljacht' this posed no problem at all. The frame parts of the 'hals' could be copied from the drawing, which was made at the start of the building, together with the stem-and stern post. ... The second futtocks which carried the master ribband all had the same shape, taken from the sectional drawing. ... The shape of the second futtocks fore and aft had to be changed: the frame becomes more curved there. This change is so gradual though, that the mold they undoubtedly used, could be adjusted with just a couple of strokes of the plane." 2000, 'Jacht Heemskerck' In 2000 Hoving used the same pictures of the building steps of the yacht 'De Brack' a.k.a. 'Jacht Heemskerck' to illustrate his book 'De schepen van Abel Tasman', "The ships of Abel Tasman". On page 57 Hoving says (my translation): "As mentioned, Witsen's charter of the yacht 'De Brack' formed the basis for the reconstruction of the yacht. ... 'De Brack' was only 92 1/2 feet long, while the length of the 'Heemskerck' was determined at 106 feet." And Hoving says this about the use of the prliminary design drawings for 'Jacht Heemskerck' of 106 feet (starting on page 57, my translation): "It is of course possible to recalculate all data, but it is easier to use the original data for making the drawings and then just enlarge these by 16,5%. The contract provides enough data to reconstruct the main frame: ... The stem post can be constructed with the measure for the height of 13 feet (A) and 17 feet for the rake (B). From where the perpendicular C crosses the vertical from A, the circle is drawn. ... He can use the arc of the circle for the rabbet and for a part of the outside of the stem post ... The stern post can be reconstructed in the same way: ... To be able to orientate ourselves in the ship later, a sketch was made of the interior. ... With this the complete drawing work is completed, and the build can start. The first bottom timber can be taken from the drawing of the main frame and can be placed on the flat with glue and pins. Both the first futtocks can be placed in the same way." Hoving shows the new preliminary design drawings for the 'Jacht Heemskerck' on page 58 of his book of 2000. Here are two of them: Hoving's preliminary design drawings of the main frame and the stem post of a '106-foot long war-yacht' (Jacht Heemskerck); as published on page 58 of Hoving's book: 'De schepen van Abel Tasman' of 2000. We can see in the design of the main frame that the 'chine' is already present in the design, and is not a result of the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method used to build the model. We can see in the design of the stem post that several arcs of circles were used. Another one of the design drawings of 'Jacht Heemskerck' is used as "Figure 7" in this article of 2008. Here it is, with its caption: Please notice that Hoving's illustration does mention "Jacht Heemskerck" and that this is the "stern construction of a small flat-tucked vessel", but that it does not mention that this is the preliminary design drawing of the "stern construction" of the "106-foot long war-yacht" of which Hoving uses the pictures to illustrate his article. In the article it is not mentioned that the preliminary design drawing of a "106-foot long war-yacht" and the nine pictures of the building steps of that same model of a "106-foot long war-yacht" belong together. 2008. A '106-foot long war-yacht'. The model of the '106-foot long war-yacht' (2008) a.k.a. 'Jacht Heemskerck' (2000) a.k.a. yacht 'De Brack' (1994) was built using preliminary design drawings. The pictures used to illustrate Hoving's article show the building steps of a model that was built using preliminary drawings. To me it is surprising that the pictures used to illustrate an article claiming that in Dutch shell first shipbuilding no preliminary design drawings were used, show a model that was built using preliminary design drawings. To me it is even more surprising that a preliminary design drawing made to build that same model shows up in an article claiming that in Dutch shell first shipbuilding no preliminary design drawings were used. To me it is equally surprising that the stem posts of the models of the yacht 'De Brack' and the 'Jacht Heemskerck' a.k.a. 'the 106-foot long war-yacht' were designed with the use of compasses, while Hoving claims on page 24 of his article that "it is most questionable that compasses were used like that in actual shipyard practice." It is good to see that Hoving's texts and pictures of 1994 and 2000, which combined give a complete account of how the model of the 'Jacht Heemskerck' was built, also give a complete account of how it was done by the sevnteenth-century shipwright: first the preliminary design drawings of the ship were made, then the shapes registered in these preliminary design drawings were used to build the ship; as per Witsen. Wrong assumptions In general, to say it bluntly: ship replica building projects and model ship building projects executed to prove that preliminary design drawings were not used, prove nothing. All these projects are based on the wrong assumption that if you can build a ship replica or a ship model without using preliminary design drawings, you have proven that seventeenth-century shipwrights did not use preliminary design drawings. This reasoning is obviously seriously flawed. All the ship replica building projects and ship model building projects using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method, I know of, used preliminary design drawings. These projects have only proven that it is possible to build a ship replica or a ship model using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method when using preliminary design drawings. But even if you would succeed in building a replica or a model using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method without the use of preliminary design drawings in 2023, this does not prove that shipwrights using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method did not use preliminary design drawings in the seventeenth century. To take this a step further: proving the assertion that preliminary design drawings were not used by shipwrights using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method, is very difficult. First of all: it is almost impossible to prove a negative: to prove that something did not exist. Because, in this case, if I can show only one example of the use of preliminary design drawings by a shipwright using the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method, the assertion collapses. And, I have already shown that one example: master shipwright of the VOC Jan Rijcksen, in 1633; two years before the yacht 'De Brack' was built, nine years before the 'Jacht Heemskerck' discovered New Zealand. See you in part 2 about Hoving's article of 2008, when we finally get to Hoving's substantiation for his 1994 claim. To be continued, Jules -

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello all, After we have seen in a former post that it is common in a part of the archaeological world to ignore Witsen's description of how the main frame was designed when working according to the Dutch shell first shipbuilding method, and to ignore Witsen's figure W, we will today have a short look at another Hoving-publication and a treatise of a history student from Belgium. Ab Hoving & Gerbrand de Vries, Bouw van replica's een waardevolle herontdekking van traditionele bouwmethoden, in: Cornelis Cornelisz van Uitgeest, Uitvinder aan de basis van de Gouden Eeuw, 2004. In their article 'Building of replicas a valuable rediscovery of traditional building methods', which was published as chapter 9 in: 'Cornelis Cornelisz van Uitgeest, inventor at the basis of the Golden Age', Hoving and De Vries say this on page 180, I (my translation): "It becomes completely incomprehensible when we look at a wooden ship. You can barely imagine that the builder did not have a picture in his head of what the ship should look like when finished. And still the largest sea castles were built without even a simple sketch. With nothing more than a number of groundrules and formulas and sometimes some moulds, our ancestors built ships with which they placed the Netherlands at the absolute top of the seafaring nations for some time. ... Concerning shipbuilding we are in luck. Near the end of the seventeenth century there were a couple of authors who described the process of building a ship step by step, and together with archaeological material, images in paintings, drawings and archival material, ...". And yet again we find the fabricated illusion that the "couple of authors who described the process of building a ship step by step" "near the end of the century" described that "the largest sea castles were made without even a simple sketch". The "couple of authors" Hoving and De Vries refer to must certainly include Nicolaes Witsen, and Witsen, as we know, describes how "a simple design sketch" was used in Dutch shell first shipbuilding. Hoving and De Vries, certainly aware of what Witsen wrote, simply decided to leave this information out of their story. Hoving and De Vries amplify their 'vision' on page 183,II (my translation): "And thus the shipbuilder determined, completely without drawings, the definitive shape of his ship hull, by which the design process was in fact divided into small steps, and every step was determined by a certain number of traditional ground rules and methods that were handed down to him. The ship arose under his hands, without an image on paper or without a model." No comment. FYI: Cornelis Cornelisz Uitgeest invented the wind-powered sawmill in 1593. His invention propelled shipbuilding in the Netherlands. Benoit Strubbe, Oorlogsscheepsbouw en werven in Zeeland tijdens de Engels-Staatse Oorlogen (1650-1674) (treatise University of Gent), 2007. In his 'Warship building and shipyards in Zeeland during the Anglo-Dutch wars (1650-1674)', Strubbe says this in his chapter "V.3 Historical wooden shipbuilding", on page 45 (my translation): "The English and the Dutch had, during the seventeenth century, the best shipbuilders between them. Their ships were rarely built based on preliminary drawings. A graphic design was almost never present. In our time this can hardly be imagined, but in the seventeenth century this was not surprising. How did they proceed to build a ship? Well, the English and the Dutch built their ships on the basis of a predetermined contract.105" Strubbe's footnote 105 says: "HOVING A.J., Nicolaes Witsens scheeps-bouw-konst open gestelt, Franeker, 1994, p.32." Again we find the statement 'no preliminary drawings were used', in combination with the source 'Hoving 1994'. While Strubbe used Van Yk's work of 1697 for his treatise, Strubbe does not even mention Witsen's work of 1671 anymore, he replaced Witsen's work with Hoving's work of 1994; he replaced the primary source with the secondary source. And this while Strubbe was surely able to read that primary source; he simply chose not to do so. Witsen's book of 1671 is still, for good measure, mentioned in the 'Published Sources' of Strubbe's treatise, on page 13, but it is never refered to in any of Strubbe's 366 footnotes; instead Strubbe refers to Hoving's book of 1994. With the aforementioned result: essential passages in Witsen's text about the use of technical drawings in Dutch shell first shipbuilding, which are left out or discredited by Hoving in his work of 1994, can no longer be found in a treatise of a history student. Benoit Strubbe graduated with honors in 2007. To be continued, Jules -

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello Mark, Thank you for sharing your views on the treatises of these three archaeologists. You are using qualifications I would not dare to repeat here, but which are probably fully justified. We will get to some more treatises of archaeologists later in this thread, and, I'm afraid, it will get worse: you have been warned. I am sorry to hear your work is also plagued by the archival losses due to fires. Paper and fire do not seem to go well together. Luckily more and more archives digitize their collections and share them on the internet. For some archives this comes too late though: they already suffered irreparable damage to their collections ages ago. So, I repeat after you: keep up the good work! All the best, Jules -

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello Doreltomin, Thank you for taking the time to share your reflections; again, much appreciated. Allow me to paraphrase your conclusion: For big projects it is natural for humans to use drawings as a means of registration during the design of the project, and it is natural to use drawings as a means of communication during the realization of the project. Since the building of a large ship qualifies as a big project, it is normal to find humans using drawings for building a large ship. You say this about intellectual property: "Yet I believe there were rules which said the plans were private property of the shipwright and he would keep (them) to himself." Let me give you an example of these rules: the master shipwright of the VOC had to swear an oath of the second degree. This oath included the clause: "That we shall not take outside the house or the office, or hand to anyone, any books, paper accounts, writings or extracts thereof, or anything concerning the foresaid Company, without order of the foresaid Lords or Masters. That all that is written, heard or seen by us, or what is ordered to be managed or to be kept secret by the Directors or the lawyers of the Company, or what our conscience should understand to be kept secret, we will keep secret and will not reveal to anyone." I think we can conclude from this that any designs the master shipwright of the VOC made, would stay the property of the VOC. I think this also shows that the VOC decided on what master shipwright of the VOC Gerrit Claesz Pool was allowed to share with Tsar Peter I in 1697; I will get to that in a later post. Again, thank you very much, Jules -

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek reacted to a post in a topic:

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

-

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Hello MTaylor, Thank you for your questions. Sorry for taking so long in replying. Let me repeat your first question: "1) Given all the wars that went through Europe over the centuries, is it likely that many (most) records were destroyed?" About Dutch naval records, I am afraid it was not because of wars that most records were destroyed. To repeat after J. de Hullu, archivist of the National Archives in The Hague from 1902-1924, specializing in the archives of the Admiralty, the VOC and the WIC: "From the start, one would almost say, the archives of the Admiralty Colleges were doomed." 22 February 1604: fire in the Admiralty of Rotterdam. 12 January 1771: fire in the Admiralty of Friesland in Harlingen. 8 January 1844: fire in the centralized Archives of the Admiralties in the Department of the Navy in The Hague. I have spent a lot of time going through the burnt remnants of these naval records, mostly on microfilm, in the National Archives in The Hague. The VOC-archives have fared better. I will show an example of the use of technical drawings in Dutch shell first shipbuilding from these archives in a future post. And your second question: "2) Guilds in many ways were secret societies, so if build plans were made, would it be realistic to think they were destroyed when the ship was launched? I do believe that much knowledge in the past was word of mouth and not recorded in an archival form." Regarding the guilds, again, a big problem for research arises. To study Dutch shell first shipbuilding we have to turn mostly to the Guild of the Shipcarpenters in Amsterdam. Nowadays the archives of this guild are kept in the minicipal archive of the City of Amsterdam. This is what the municipal archive of Amsterdam says about the archive of the Guild of the Shipcarpenters of Amsterdam on its website: "Not much is left of the archive. Just some of the financial registers are kept in the municipal archives." I have never heard that the Guild of the Shipcarpenters in Amsterdam recommended destroying build plans after the ships were built. If the Guild recommended destroying, its recommendation must not have been followed, for example: Witsen shows a lot of build plans in his book of 1671, the Scheepvaartmuseum in Amsterdam holds a lot of seventeenth century build plans in its collection, I know build plans were kept at an artist's place in Amsterdam in 1669, and I know of a handbook of a shipwright of the second half of the seventeenth century that holds coordinates of built sloops, and build plans of ships and their construction. To me, all these sources show that build plans were not destroyed after building the ship, but that the build plans were used as "an archival form", as you call it. I will dedicate future posts to the design drawings at the artist's place and the handbook of the shipwright to show what I mean. "Knowledge was not recorded in an archival form". I do not know about your memory capacity right now, but my memory capacity is certainly not enough to hold all the data of one ship, let alone of several ships. Drawings were made in architecture, be it in house building or ship building, in the seventeenth century because they served a purpose: they expanded the memory capacity; once the drawing is made you can forget about the data used to make that drawing. These drawings for me are a form of knowledge "recorded in an archival form", as you call it. Why do we accept that drawings were made in seventeenth century house building, and why don't we accept that drawings were made in seventeenth century ship building? Here is for example a design drawing made by the 'City carpenter', we would call him city architect now, of the city of Leiden Willem van der Helm in 1669: 'City carpenter' Willem van der Helm made design drawings for buildings and bridges for the city of Leiden from 1662 to the early 1670s, and, as we can see, also made a design drawing for the yacht of the city of Leiden in 1669. (From: Elske Gerristen, 'De grondt, standt teeckeninge ende profyl geteeckent op de cleene maet', UvA). Gerristen says: "Every city had her own city yacht that had to be replaced regularly. The city carpenter usually provided the designs." I think 'building architect/naval architect' Willem van der Helm shows us that there was no 'hard' separation in design activity in 1669. In general I think we have to keep a very open mind to study design activity in the seventeenth century. When we assume that 'knowledge in the past was word of mouth and not recorded in archival form', as you suggest, the will to research is the victim: when we assume that there are no 'records in archival form', I am pretty sure we will not find any 'records in archival form'. Regarding Dutch ship design activity, we first of all have to accept that Rembrandt shows us design activity of a shipwright in 1633, and that Witsen shows us design activity of shipwrights in 1671. I notice that, for some, it is very hard to even accept those two facts. I hope this answers your questions. If not, please do not hesitate to ask some more. Kind regards, Jules -

Technical drawings & Dutch shell first

Jules van Beek replied to Jules van Beek's topic in Nautical/Naval History