-

Posts

984 -

Joined

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

TJM reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

TJM reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

Arthur Goulart reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Arthur Goulart reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

Kris Avonts reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

Kris Avonts reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

cotrecerf reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

cotrecerf reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

It's called estain and is quite common on French plans (but encountered on others as well).

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

druxey reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

Bob Legge reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

Bob Legge reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

JerryTodd reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

JerryTodd reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

bruce d reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

bruce d reacted to a post in a topic:

Index of French plans from the Danish archive

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

https://www.aamm.fr/archives/neptunia/articles/plansdanois

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

Hubac's Historian reacted to a post in a topic:

Sovereign of the Seas by 72Nova - Airfix - PLASTIC

Hubac's Historian reacted to a post in a topic:

Sovereign of the Seas by 72Nova - Airfix - PLASTIC

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

Martes reacted to a post in a topic:

Hvide Ørne and Wildmanden by Arthur Goulart

-

There is a contemporary plan for the frigate La Licorne https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-82907 but you'd note that both her and Belle-Poule's reconstructed wales include a step above the wale, on the gundeck level, just like on the model and plans for Wildmanden. A that's what the Danish got rid of towards the end of the century, making the ships' sides totally smooth.

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

A bit of both, I suppose. But it is definitely more expensive and requires more time, effort and quality control to produce, install and post-process uneven planks, thinner at one side and thicker at the other, that form the blended wale and have to be precisely touching one another. The British adopted this practice only in the wake of the captured Danish fleet, as they were really impressed by the Danish workmanship. Note that in itself this is a case of reverse-engineering of a French design that passed through British hands.

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

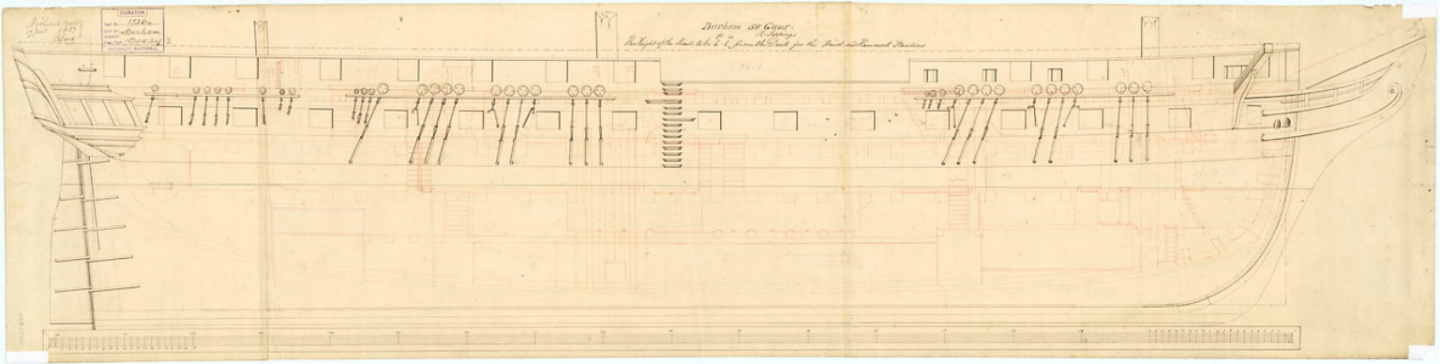

For the context. Le Superbe was a curious ship, as she was a very large privateer in origin, designed by Pierre Coulomb. There are three plans of her in RMG collection. 1. https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-81601 as (apparently) taken off at Woolwich Dockyard prior too undergoing her 'Grand Repair' 2. https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-81602 shows her as she (apparently) emerged after the great repair, note that the hull form is different 3. https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-385589 shows her French framing structure, which is very light for a large ship, also, from the shape of the hull lines, (apparently) made during the preparations for the rebuilding. The dating, however, may be reversed, with the original form of the ship being 2,3, and as rebuilt on image 1 (there are some indications to support this, but closer inspection of the plans is needed to be sure). The main difference is in the lines close to the keel, being either fuller, or more hollowed. The design for Augusta is, in any case, based on the lines on plans 2 and 3 https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-81552 https://arkivalieronline.rigsarkivet.dk/da/billedviser?epid=17149179#189859,31918075 And it is this form that reached Denmark and was studied, and unless I am much mistaken, it does bear some relation to the design of the Wildmanden.

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Well, painting of ships was always somewhat fluid, subject to paint availability and all, and not necessarily coinciding with the run of the planking at all. From construction point of view, at least in 1807 it was observed by the British (Naval Chronicle article about the captured ships) that on the Danish ships the wales are blended into the planking, thus preventing accumulation of filth. The decoration plans follow the French practice, that usually shows the uppermost and the lowest planks of the wales, creating an illusion of having two. It's purely a drawing convention, however.

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

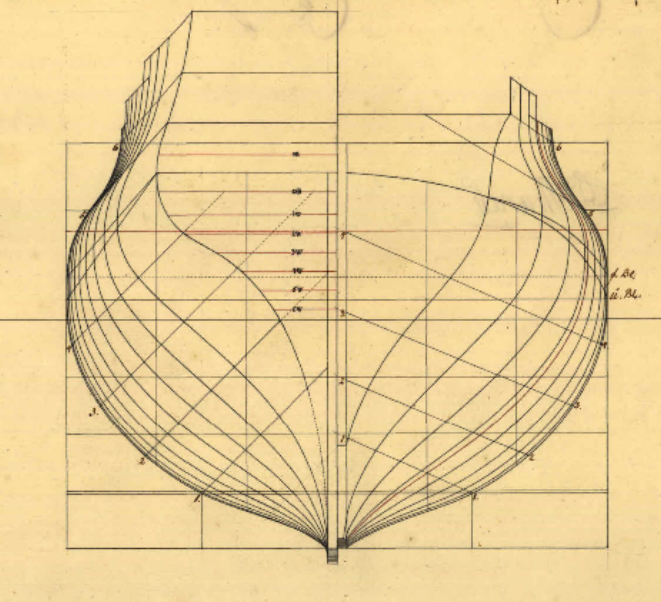

FWIW, plan A 1126 e https://arkivalieronline.rigsarkivet.dk/da/billedviser?epid=17149179#208249,39521732 contains some references to the design method including quarter frames.

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

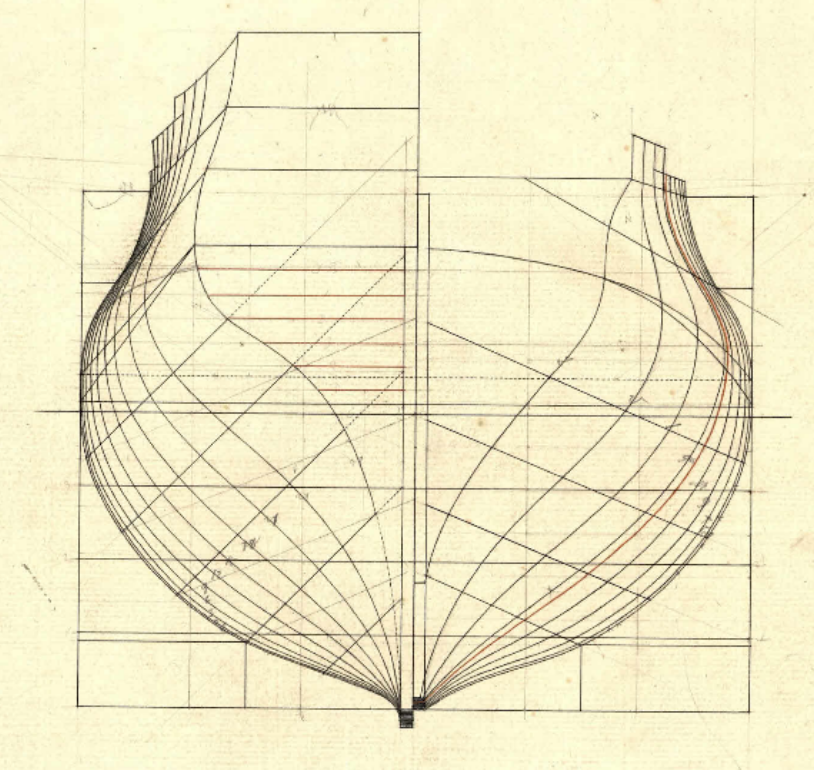

Note that in Danish practice it was common to position the frames perpendicular to horizontal waterline, and thus in a kind of ladder on an inclined keel, so in this case the stations on the plan do represent the shape of the frames. see A 1126 b inboard view https://arkivalieronline.rigsarkivet.dk/da/billedviser?epid=17149179#208246,39521729 Also note that both A1126 e and G 2793 plans show an apparent correction or some auxiliary line at the 4th station that would likely require an explanation (in red)

- 49 replies

-

- Wildmanden

- Turesen

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

See this post for the latest state of the razee model - https://modelshipworld.com/topic/20250-age-of-sail-2-3d-ship-models-for-pc-wargame/?do=findComment&comment=1053647 I did not model the rig and sails, they're ingame models that are assigned in a configuration file. Strictly speaking, the Barham is the only razee configuration I did not do, i.e. unlike her sisterships she had a conventional square stern (they all were built a bit differently, because this was an experimental series, and sometimes the sterns were altered along the way). see the whole gallery here - https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/object?vessels[0]=Barham (1811) But she certainly wasn't wrecked in 1828 (although they seem to have been messing with her bottom at some point in Curacoa), she was pretty active in 1830s in Mediterranean.

-

In 1803 the British, and in 1812 the Americans were widely experimenting with all kinds of floating explosives with various mechanic timers, that ranged from a barrel to a boat full of explosives with fixed sails. The intention was to launch them during the tide in the direction of anchored ships, and if I recall correctly, one such attack in 1812 was almost successful, but the explosive was spotted and shot from the ship. And both types of those devices are, surprisingly, present in the game. You can use a towed submarine to drop explosive barrels (they won't move, but you can position them relatively accurately), you can dive the submarine under a stationary vessel and release the explosive there, that will act as attached to the hull, and you can make an explosive torpedo from a small ship by assigning an appropriate quality in the database editor.

-

That's not how it works in the game. Well, mostly. The submarine is awfully slow when released, and it leaves the explosive mine where it is on the map, not attaching it or anything. So you have to time the release correctly, because there is a pause between the placement and the explosion (that is intended to remove the submarine from the danger zone). The way it is implemented it is probably closer to torpedo experiments of 1803 and partly 1812. I also scaled the model down to about half original size, it looks more natural like that. And it's working best when in tow of a ship, not autonomously. And, of course, you can create as many copies of them as you like. They just shouldn't be treated is as a historical unit, but rather as an ad-hoc device (which it is), and with understanding that such ad-hoc devices were an essential part of period warfare.

-

Apart from adjusting damage and maneuverability models in the game, I think it's the submarines that I found the most enjoyable part of the gameplay. They give that very Master&Commander-like functionality of towing something with the ship and using it to blow things up - especially that you don't need to detach the submarine to place a bomb, so they are automatically reloaded, and thus you can hunt the enemy subs (that are barely visible and vulnerable only to own bombs) or even try to sneak with a brig or sloop and mine the path of an enemy ship. Lots, lots of fun. What I need for increasing replayability is some kind of automated converter from geospatial data to ingame maps.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.