-

Posts

19 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Profile Information

-

Gender

Male

-

Location

California, USA

-

Interests

Design, model kits

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Thank you @Snug Harbor Johnny. The period I am looking at is right before getting stuck. I want to challenge myself with a diorama showing ice around the ship. I wanted to get the hull above the water line right, the one below shouldn't be visible. Since I am quite new to this fascinating world of ship modeling, I take new opportunities to learn new techniques 🙂

-

Jim Lad reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Jim Lad reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

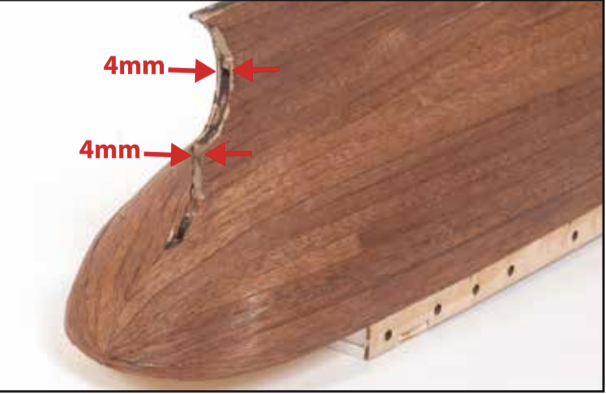

Today, I am doing some research on planking for the second layer of the hull. While many suggest that a second planking is unnecessary due to the hull’s subsequent painting, I believe that the planks will still be visible, necessitating their accurate representation. Standard ship-building practices at that time for a vessel of 144-foot size suggest surface planks widths of approximately 8 to 10 inches. Most planks were between 20 and 30 feet (6 to 9 meters) long. While some exceptional timbers could reach up to 40 feet, these were rare due to the difficulty of steaming and bending such large sections of oak or greenheart to fit the ship's curves. Like all wooden ships, the lengths varied to ensure that the "butts" (the joints where two planks meet) did not line up vertically. This "staggering" was vital for the structural integrity of the hull. The builders followed strict rules for the "butts”: The 3-Strake Rule: No two joints could be on the same vertical frame unless there were at least three full planks(strakes) between them. Horizontal Distance: Joints in adjacent planks had to be separated horizontally by at least 5 to 6 feet. Result: This required using a variety of plank lengths (e.g., a 22-foot plank followed by a 28-foot plank) to create a complex, interlocking brick-like pattern that distributed stress across the entire hull. This seem to be confirmed by the post https://modelshipworld.com/topic/39502-splice-hull-plank/#findComment-1128329 from @Dr PR. Translating this to the model, planks width should be 2.90 mm to 3.63 mm, and 86 mm to 128 mm in length. Finally, I will also have to revise how planks are layered since the kit instructions don’t seem to match with the ship pictures. I hope that my research is accurate, but if anyone has any suggestions, I would be delighted to rectify any errors.

-

Ronald-V reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Ronald-V reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

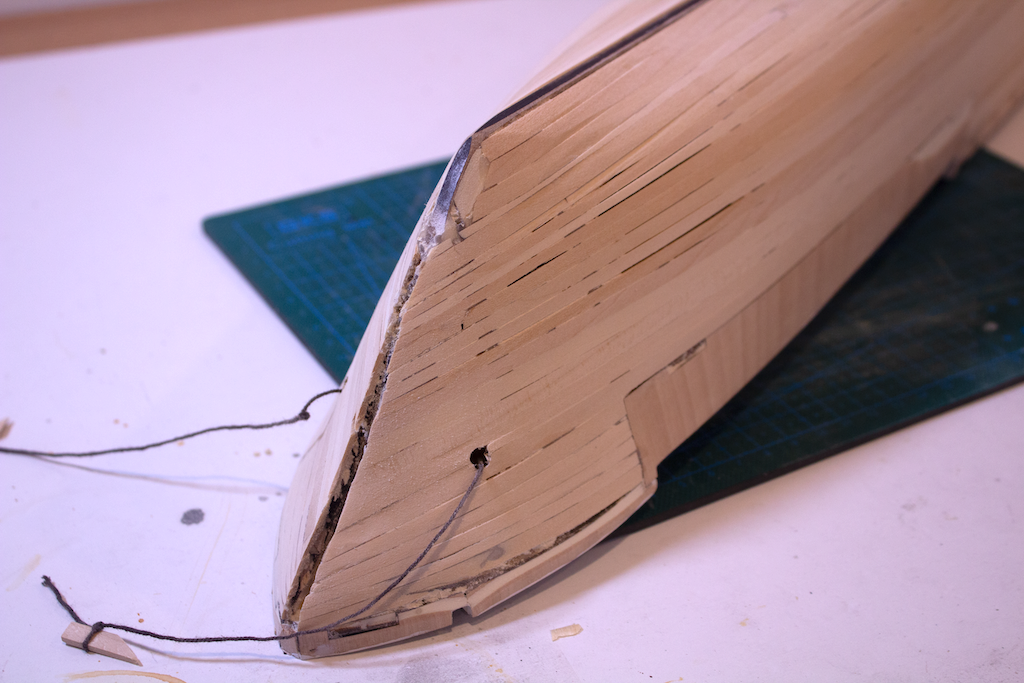

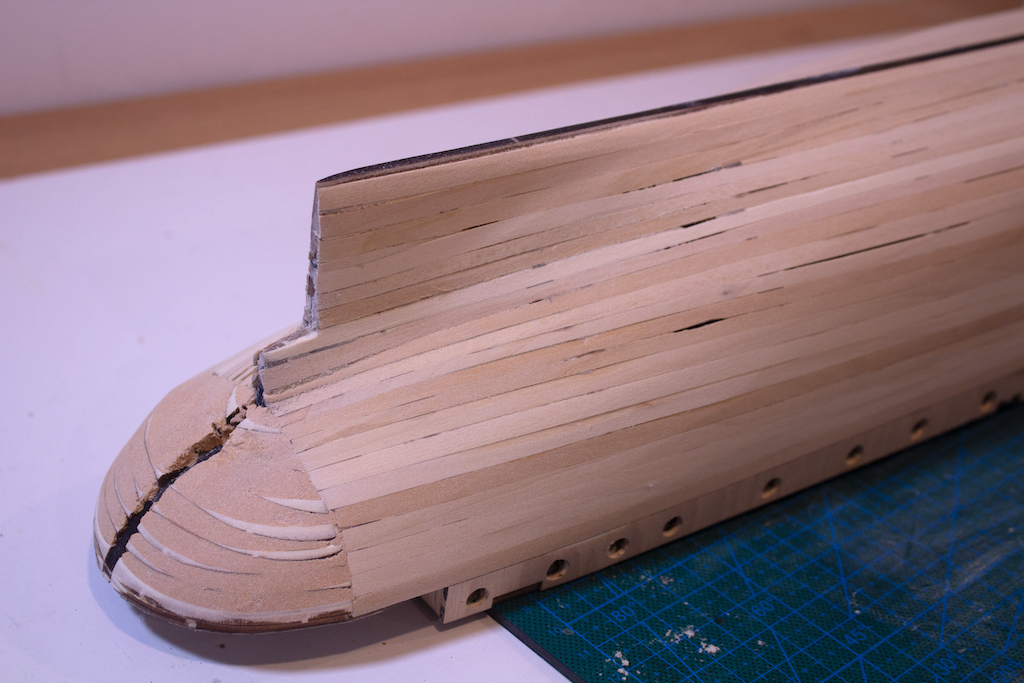

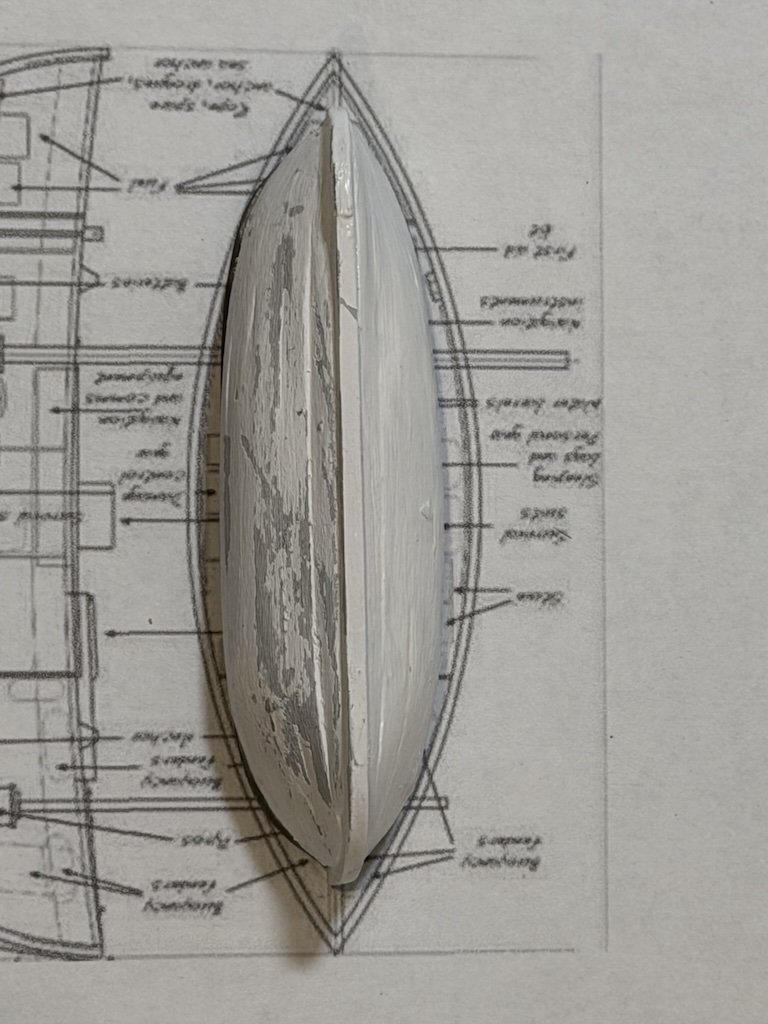

The initial layer of planking is nearly complete. I still require the addition of filling and further sanding. My intention is to incorporate a second layer of planking. Although I intend to paint the surface, I believe the underlying planks will be discernible, so I would like to enhance their scale accuracy.

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Keel first before planking?

-

Knocklouder reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Knocklouder reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

sheepsail reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

sheepsail reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Harvey Golden reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Harvey Golden reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Harvey Golden reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Harvey Golden reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Pierre Greborio started following Keel first before planking?

-

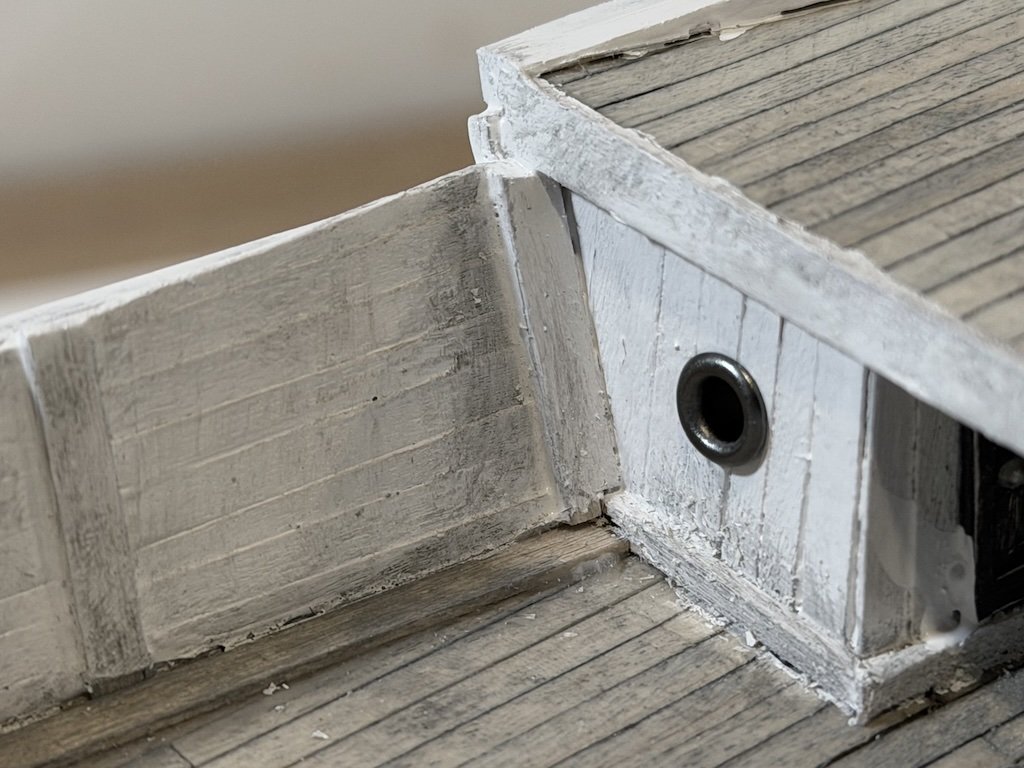

Working on the inboard side of the bulwark according to instructions with few modifications. In heavy polar vessels such as the Endurance, leaving the stanchions exposed on the interior (a common practice on lighter sailing ships to reduce weight) was not feasible. The bulwarks were specifically designed to serve as a solid, insulating barrier. Solid interior planking effectively prevented ice, snow, and frozen spray from being trapped between the stanchions, where they could expand and potentially cause structural damage. Additionally, this design enhanced crew safety during storms by preventing gear, ropes, or limbs from becoming ensnared in the “pockets” formed between the vertical posts. Furthermore, the interior planking facilitated the distribution of the immense tension exerted by the pin rails (where the ropes were secured) across multiple stanchions, rather than concentrating it on a single point. Horizontal planks with a width of 7-8 inches were laid. Consequently, I incorporated 2.8 mm planks between the stanchions. Finally I weathered a bit.

-

I am back working on the double-ended whaleboat following instructions from the kit I am not really satisfied. The lifeboat seem to be quite off scale This includes the planks and ribs, which are significantly larger than their intended size. I acknowledge the compromises made in the kit, as those components are quite small when considering the scale. I am entertaining the idea of building those from scratch 🤔

-

I started working on the sides of the hull. Pretty straightforward, with one small change, the diameter of the portholes. Looking at this picture it appears the porthole is about bit larger than 2 planks. At construction time, standard ship-building practices for a vessel of her 144-foot size suggest surface widths of approximately 8 to 10 inches. Let’s assume the porthole to be 20 inches in diameter, I then drilled those to 7mm.

-

I have been doing some research on the lifeboats. The kits shows two kind of lifeboats: a double-ended whaleboat and a standard rowing cutter. The double-ended whaleboat, named James Caird, went through several modifications made to prepare for the legendary 800-mile journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia. I am more interested in the version prior to those modifications. Luckily there is ample documentation online about this lifeboat, and here I collected some of them: Length: 22.5 feet (6.9 meters) Beam (Width): 6 feet (1.8 meters). Original Build Materials: * Planking: Baltic Pine. Keel and Timbers: American Elm. Stem and Sternpost: English Oak. Based on the original vessel preserved at Dulwich College (https://www.dulwich.org.uk/about/history/the-james-caird) and the technical surveys conducted for modern replicas (like the Alexandra Shackleton), the planks width of the hull varies due to the curvature of the hull ("tapering"). In the middle of the boat (the midships), the planks are typically between 4 and 6 inches (10–15 cm) wide. The thickness was approximately 1 inch (25 mm) thick. Finally planks were fastened to the ribs using copper nails and roves (small washers), which were standard for high-quality boat building at the time to prevent rust in saltwater. Thus, if my sourcing is accurate, at scale 1:70 it should be: Length: 98.57 mm Beam (Width): 25.714 mm Plank width: 2.143 mm Plank thickness: 0.36 mm I couldn’t find an image of the plans to make a comparison with what is provided with the kit. However it appears that the kit is smaller by few millimeters, and the planks are double their size. If anyone has an image of both lifeboats plans I would rally love to see them.

-

Some progress has been made on the open space beneath the foredeck, drawing inspiration from @Tomculb. The planking has been added, painted white, and weathered to achieve a realistic appearance. Two small doors have been constructed, painted dark brown, and weathered accordingly. To enhance the authenticity, wear and tear have been applied, simulating the typical characteristics of doors. The door knob has been crafted from the head of a brass nail, sourced from the kit, and subsequently aged using ammonia fumes.

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

Pierre Greborio reacted to a post in a topic:

Endurance by Pierre Greborio - OcCre - 1:70

-

After conducting some research on deck planking, I discovered several features that deviate from the kit specifications and require adjustments. Plank width Upon comparing photographs with the kit plans, it is evident that the planks are more than double the required dimensions (https://modelshipworld.com/topic/39482-endurance-deck-planks-on-170-scale/). Consequently, I have decided to reduce the plank thickness to 1.75 mm. Nails It is suggested to draw nails at the end of each plank. Looking at multiple pictures I fail to see any nail. By the time the Endurance was built in 1912, shipwrights used a technique called "Counterboring and Plugging" to hide all metal fasteners. Months in the Antarctic, the saltwater, ice, and coal dust weathered the entire deck to a uniform "silver-gray" or "charcoal" color, masking the circular outlines of the plugs. Plus the decks were frequently "holy-stoned" (scrubbed with sandstone and seawater), which kept the surface extremely flat and level. I decided to skip nails altogether. Stain The deck was primarily constructed from Norwegian Fir and Oak. Unlike the hull, which Shackleton had repainted from white and gold to a stark black (to make it more visible against the ice), the deck was generally left unpainted. When fresh, the wood would have been a warm, pale honey-tan or creamy yellow (typical of fir). But once the ship reached the Antarctic, the constant exposure to saltwater, intense UV light, and abrasive ice crystals would have weathered the wood. This turns the tannins in the wood a "driftwood silver" or soft gray. The long gaps between the planks were made watertight using a process called caulking. Sailors hammered unspun hemp fibers (oakum) soaked in pine tar into the seams and then poured hot pitch or "marine glue" over the top. This created the dark, thin lines you see running the length of the ship in photos. I treated the edges of each plank with graphite bars, subsequently glued them together. Following this, I sanded the planks to achieve a smooth surface. Finally, I applied a couple of coats of weathered aged wood finish, utilizing a combination of #0000 steel wool and white vinegar, which was left to react for two days. Here is the result of my experiment (the picture lost a bit of gray). I feel pretty good about it and ready to start the real deck planking.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.