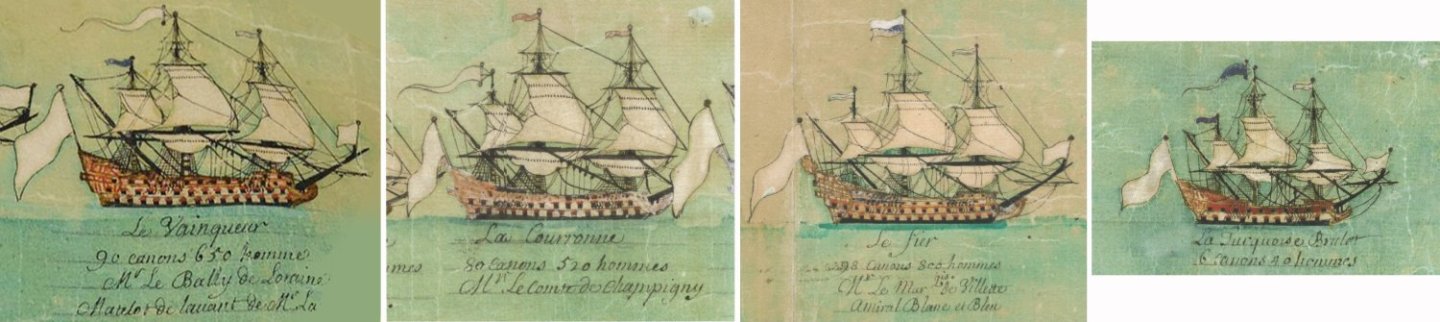

-

Posts

38 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by John Ott

-

Are you being logical again, Marc? This has to stop... Seriously, I've regretted not taking your path and not making and installing chain plates at the same time I attached the stropped deadeyes to the channels. Now I'm stuck retrofitting the chains—somehow without soldering, since soldering elements + styrene = tragedy. I think I'll put off my own wire-bending until your next few posts so I can see how my betters do it.

- 2,444 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

Yeah, Hitchhiker's, Marc. I suppose that dates me somewhat. I spent the day installing mainmast tackles and mulling over the problem you highlighted. I finally hit on a good rationalization: my Soleil has fish because the model represents the ship as it appeared some time after the Battle of Malaga instead of before, as I previously intended. The masts had battle damage repaired, but remained weakened, hence the fish. Actually, having repaired battle damage justifies a whole host of deviations from the Boudroit norm, so I can use the same excuse next time I get into trouble.

- 2,444 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

Wow. Good job on correcting the masts. Boudroit says specifically in his section on masts and fittings that there were no fish, except—"The use of fish was known, but used as pieces of timber intended to correct the least weakness in resistance of a mast that could have been cracked but not broken." (Book's not-terribly-great English translation.) So—live and learn. In my case, I learned too late. I didn't get Boudroit's book until after my lower masts were already installed, and so I'm going to live with them, fish and all. So long, and thanks for all the fish.* (*dated reference.)

- 2,444 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you, Kirill. It looks like all my lines may need another coat of stain. It's better to find that out now before any are up.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Johnny. Thanks for the input. I never know what to make of the rigging on historic models. They've either aged several centuries themselves or the ropes have been replaced in restoration. Either way, the lines probably aren't the original color. And I don't know how close they were to reality in the first place. For my model, maybe I should just stain the ratlines dark brown.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Keith. I don't know if it's visible in the photos, but I stain my "light" lines to look (at least to my eye) like old hemp rope, kind of a greyish brown.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Johnny. So far, I think I'll be using light-colored lines. I read somewhere that the deadeye lanyards weren't tarred because they frequently needed adjusting, and the ratlines don't seem to be tarred on OPM (other people's models). Being a newbie, I learn a lot from OPM. If I'm wrong—there's always black paint.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

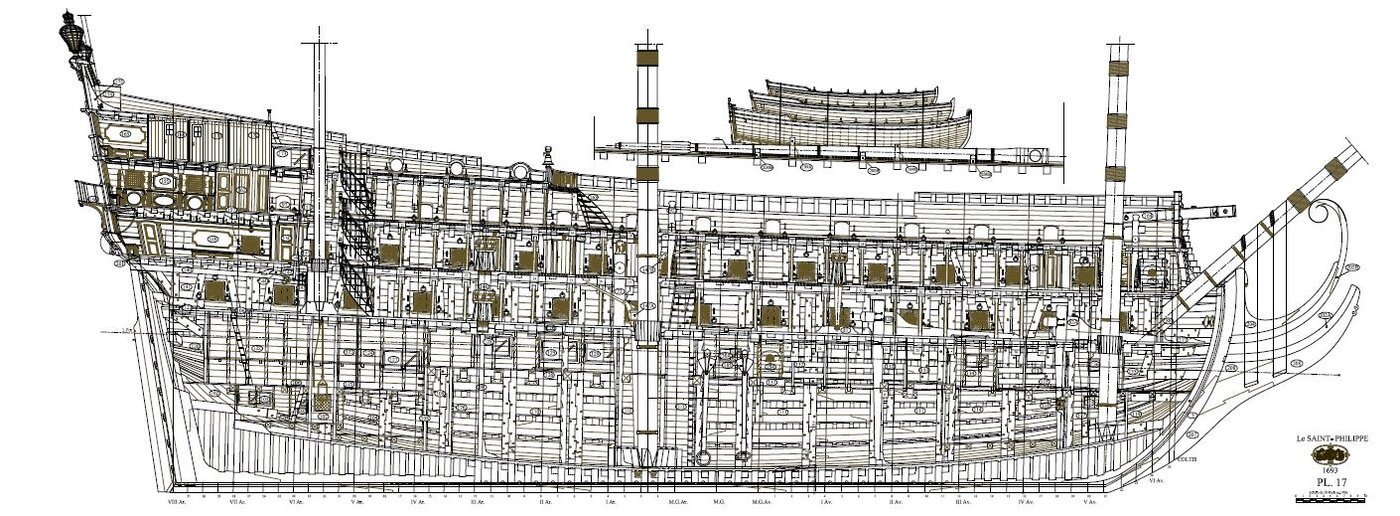

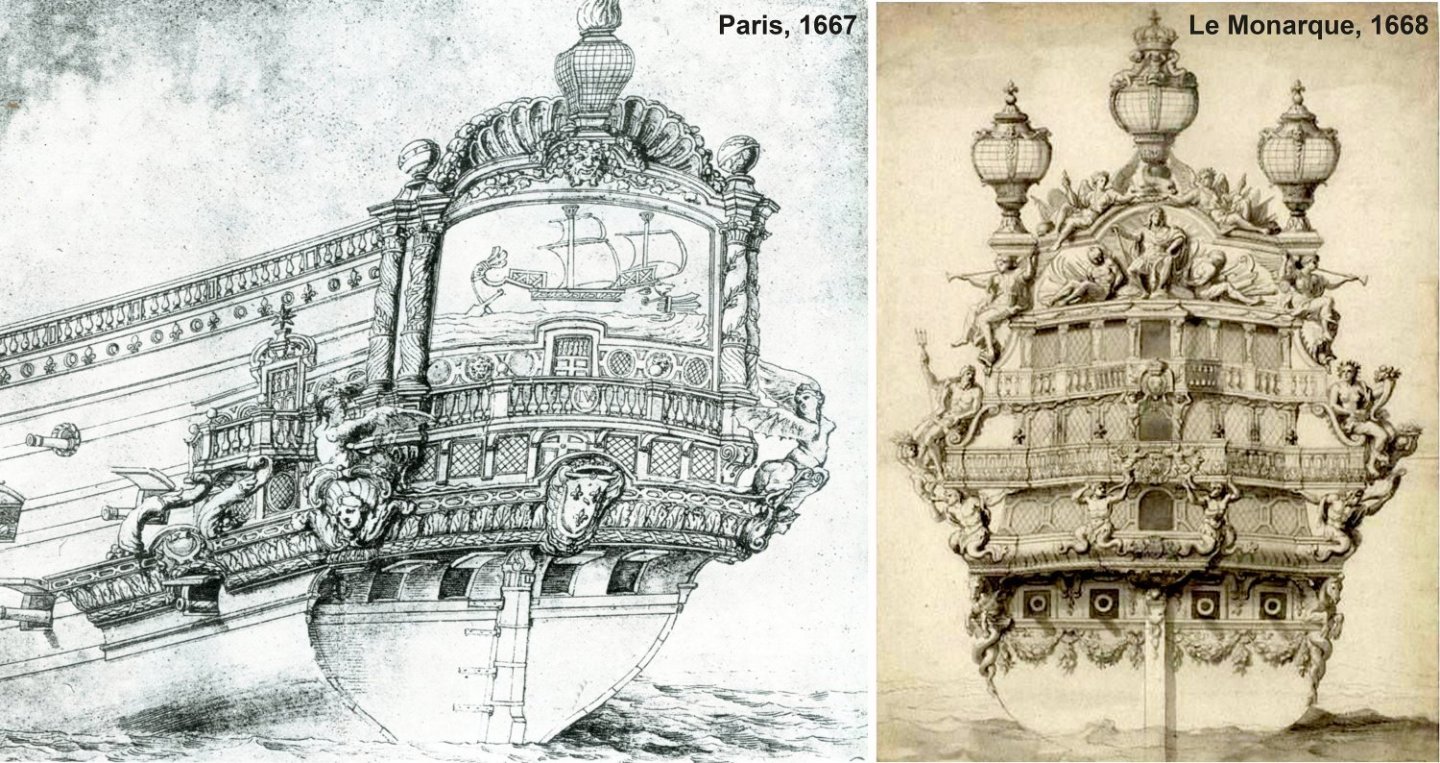

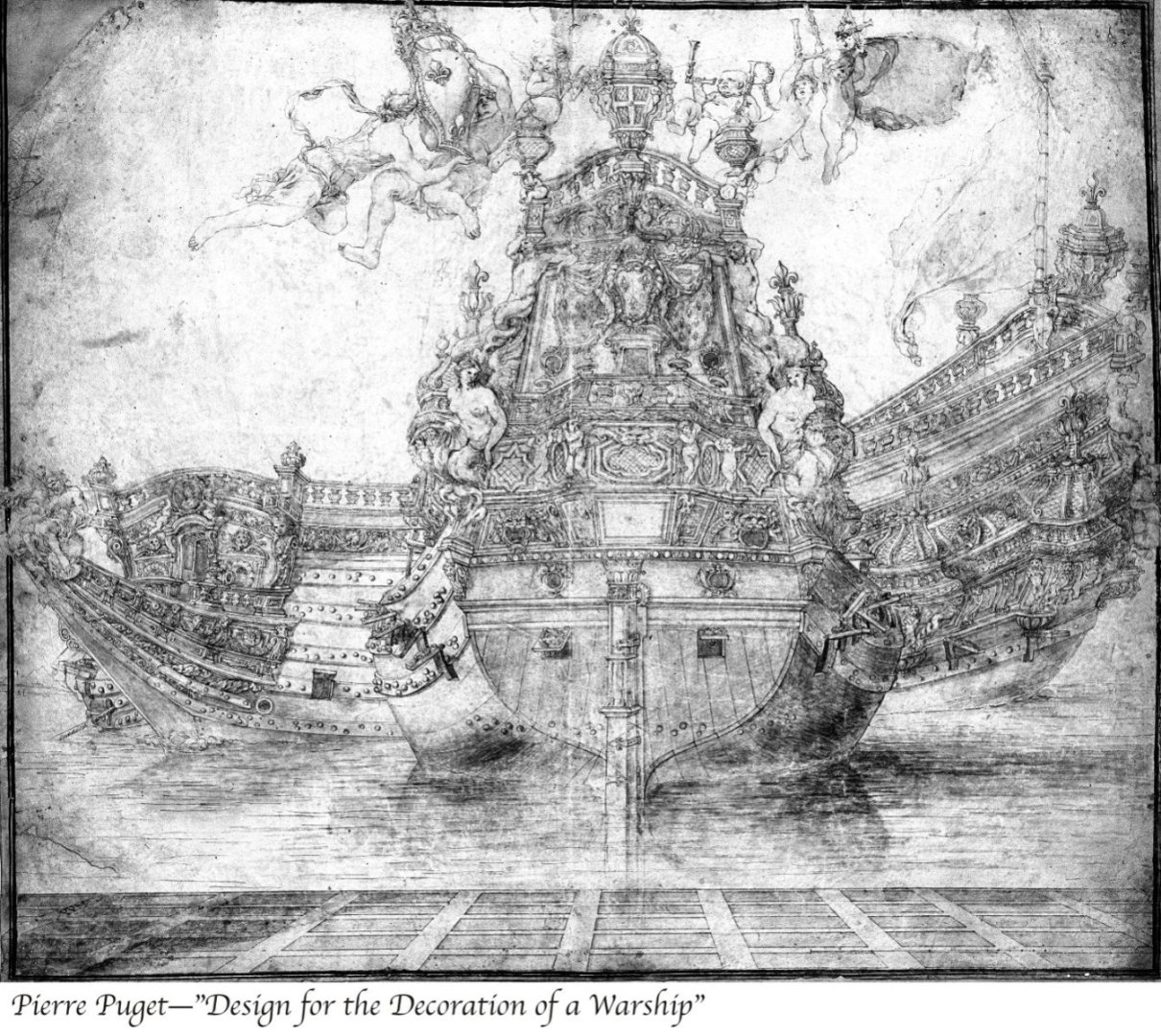

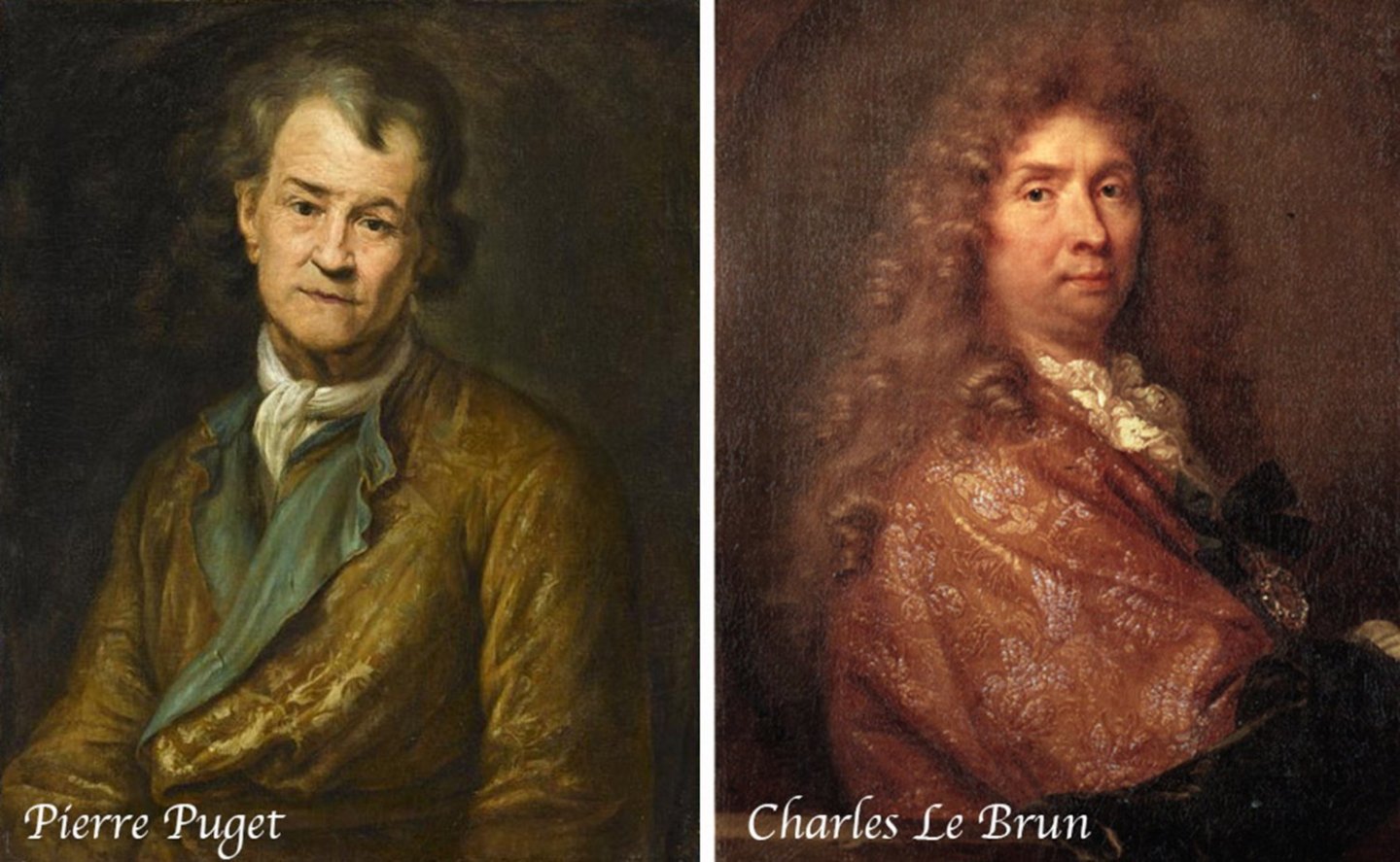

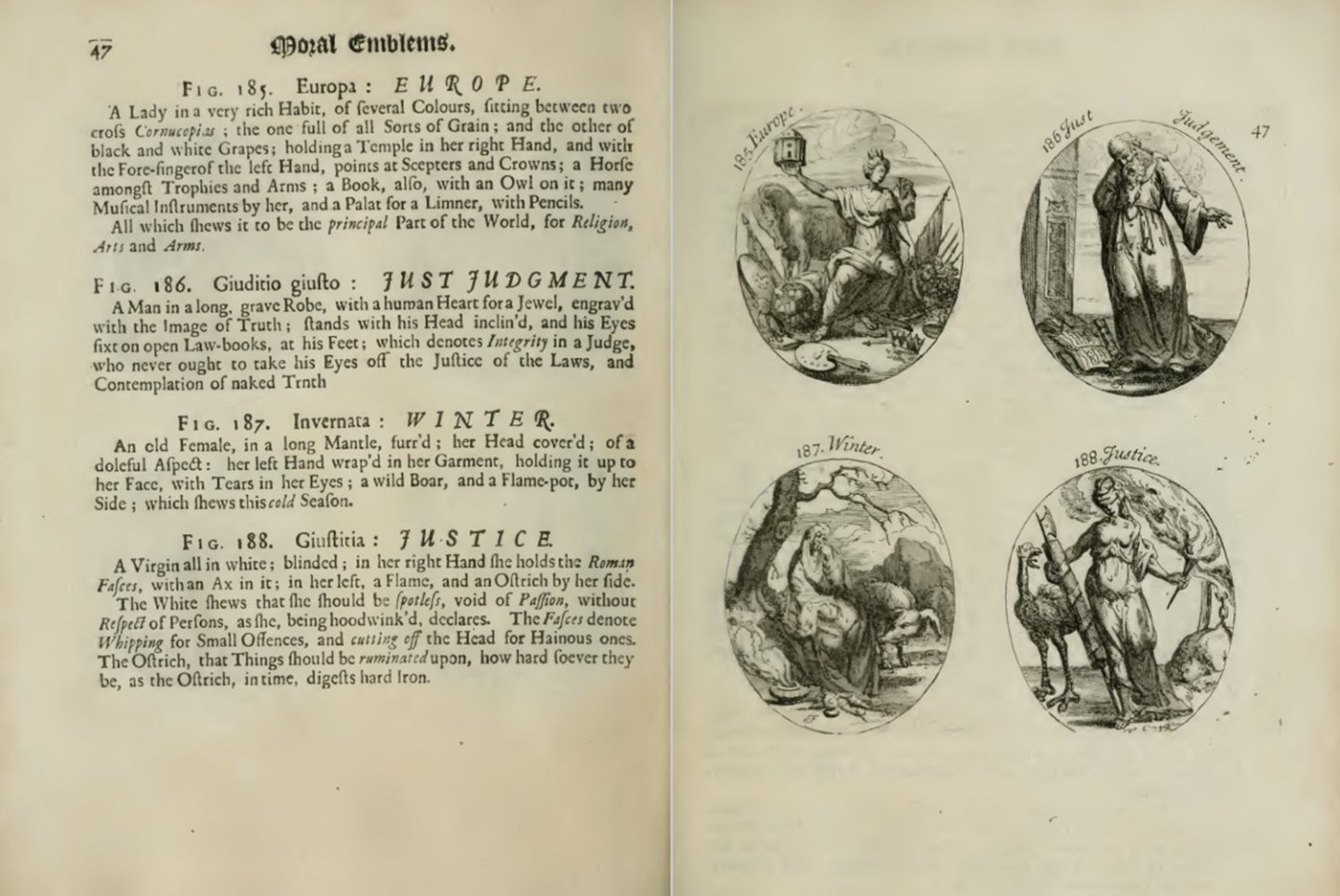

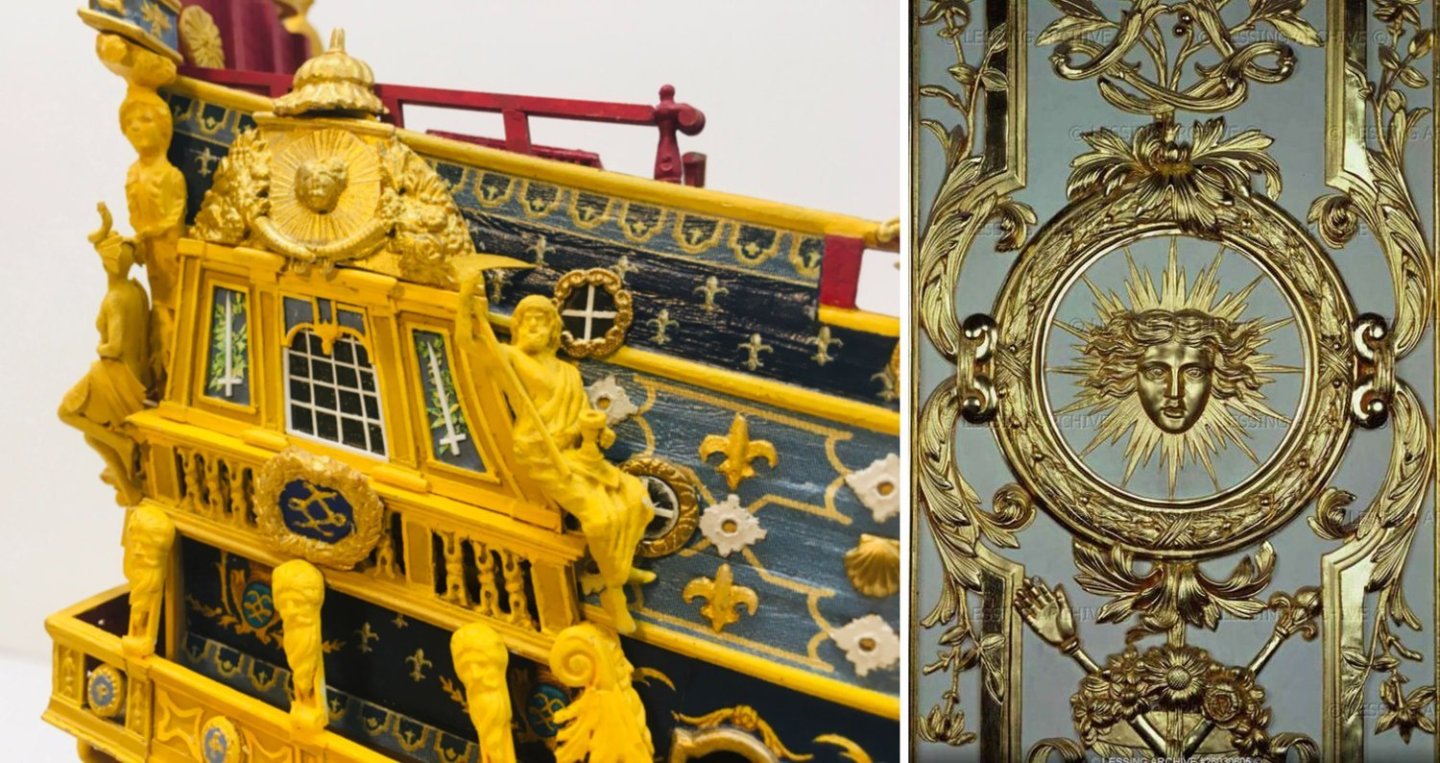

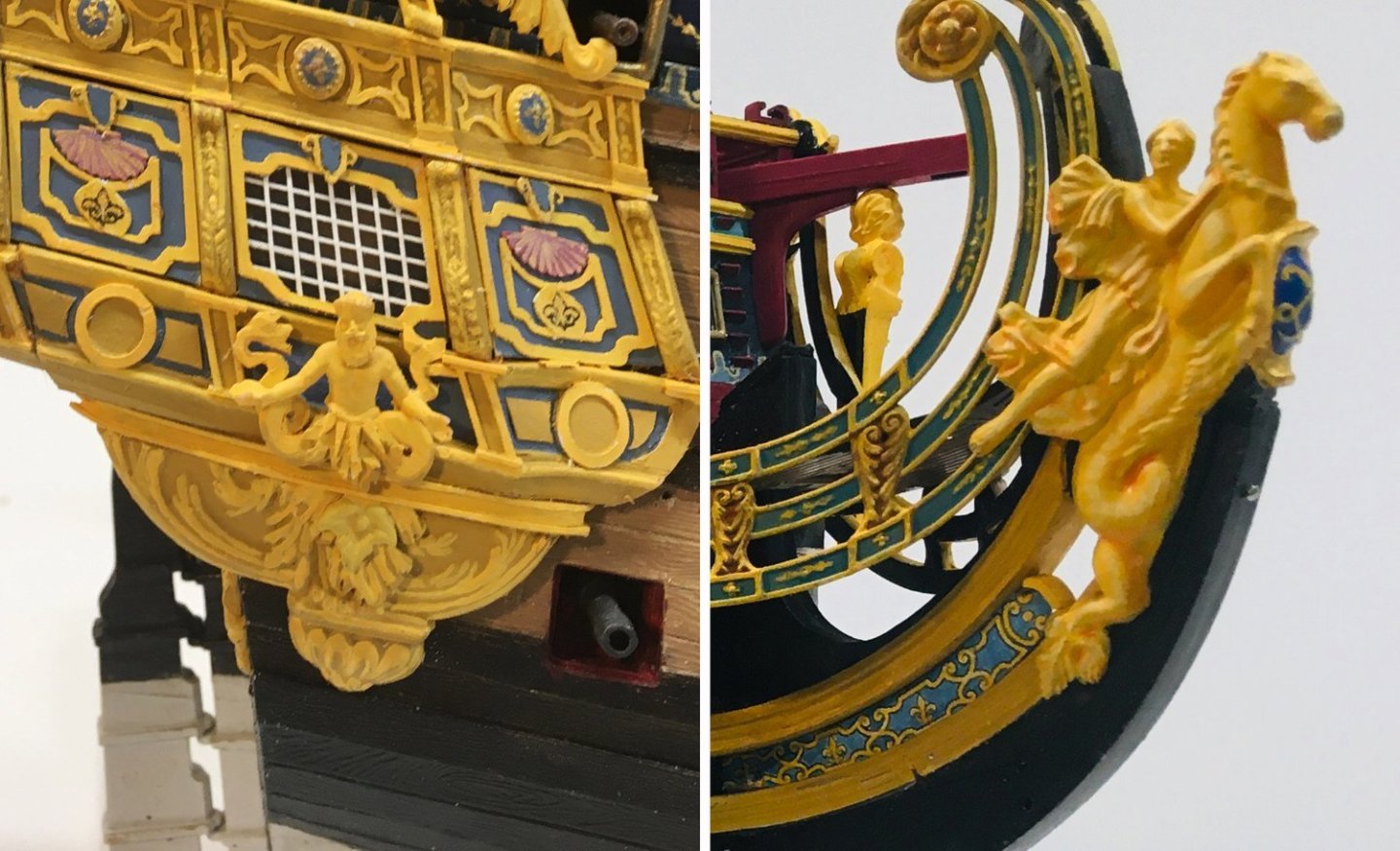

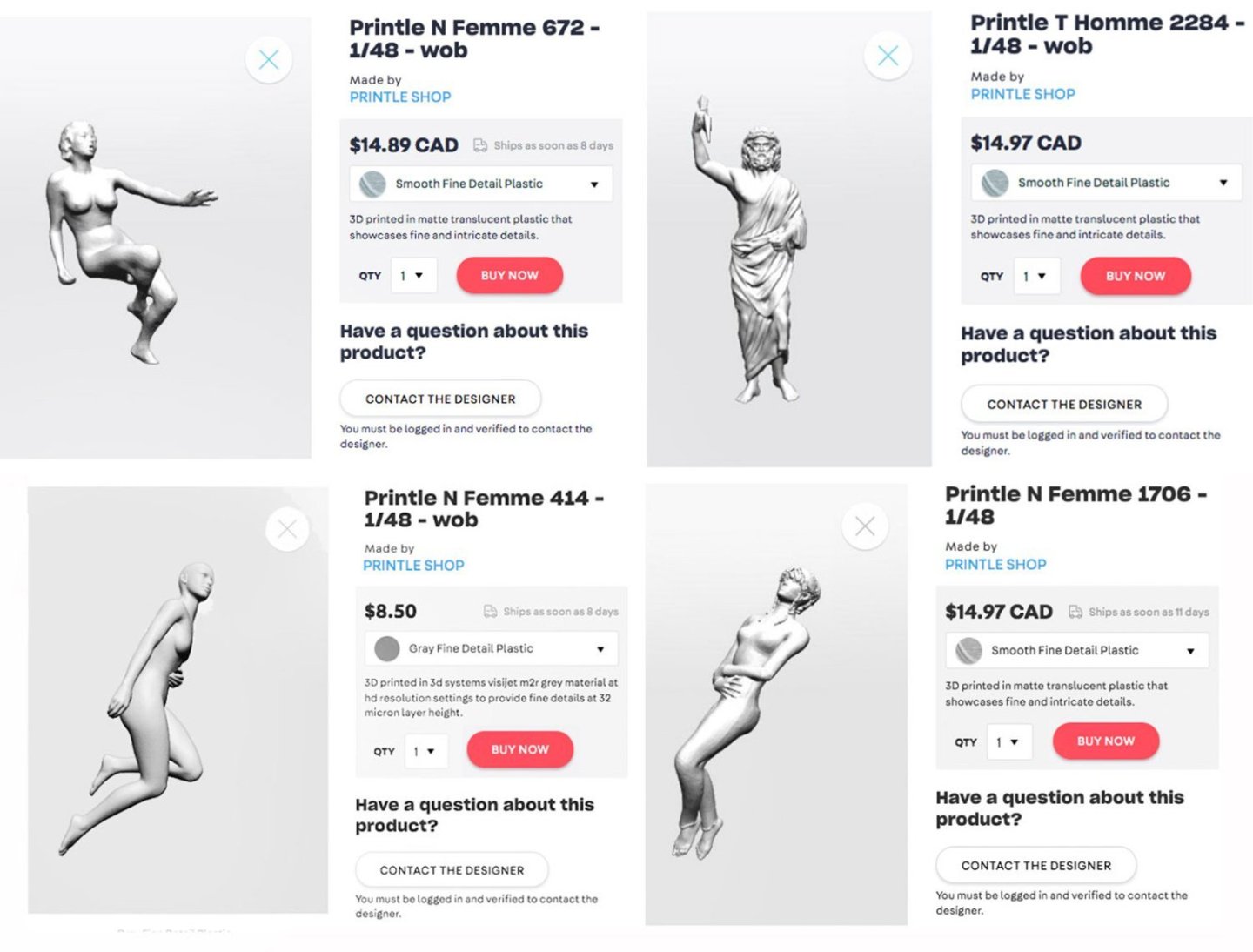

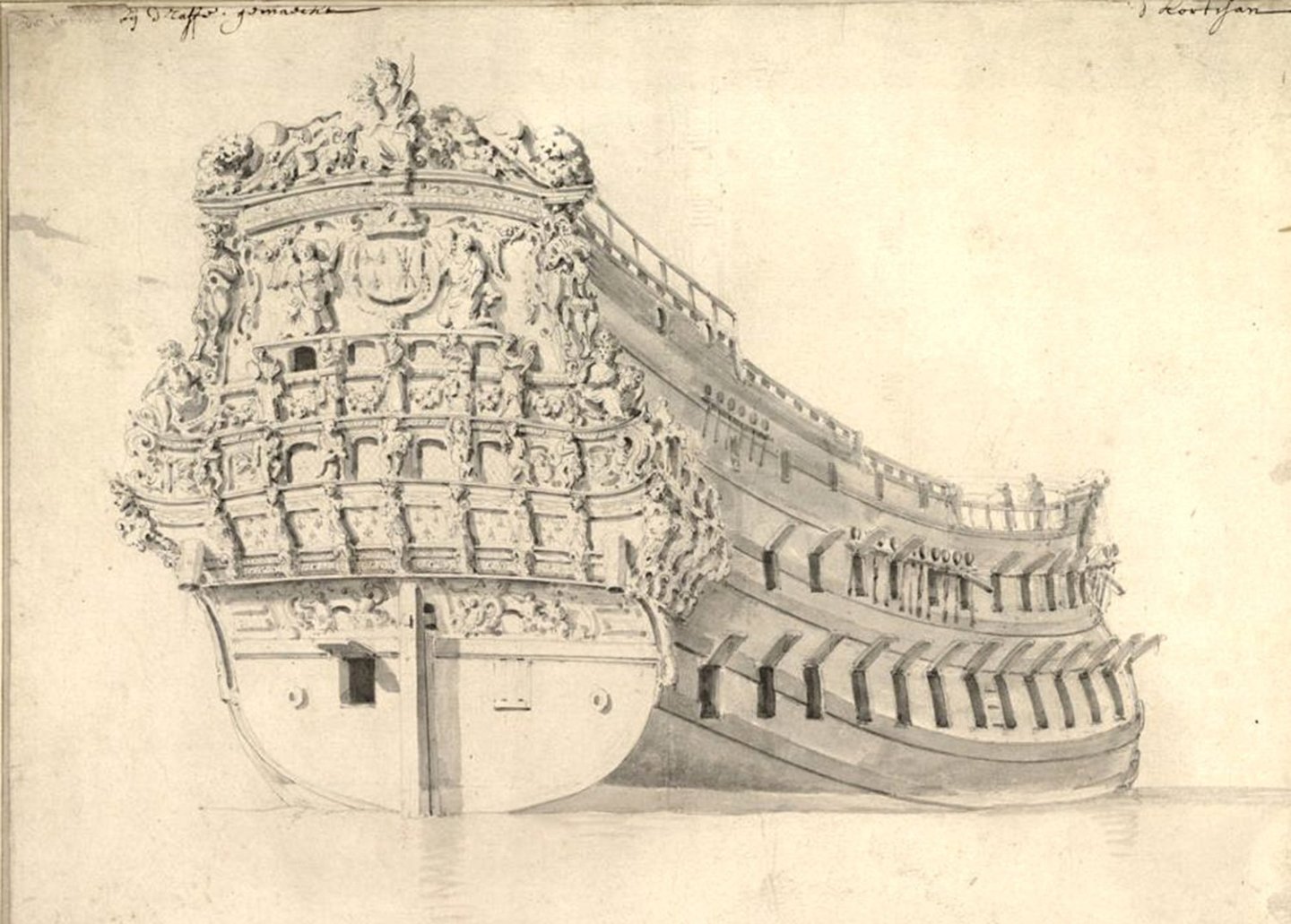

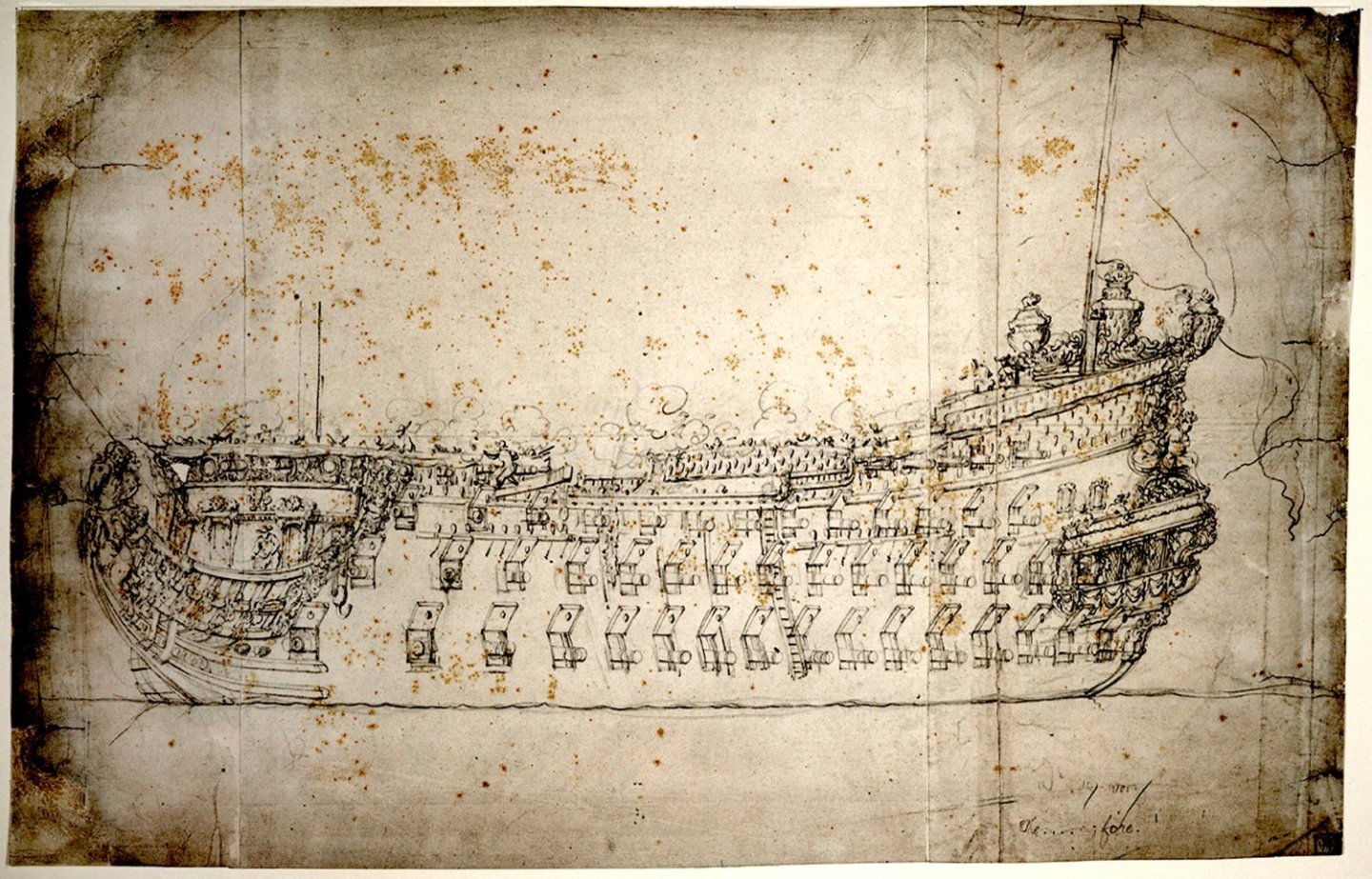

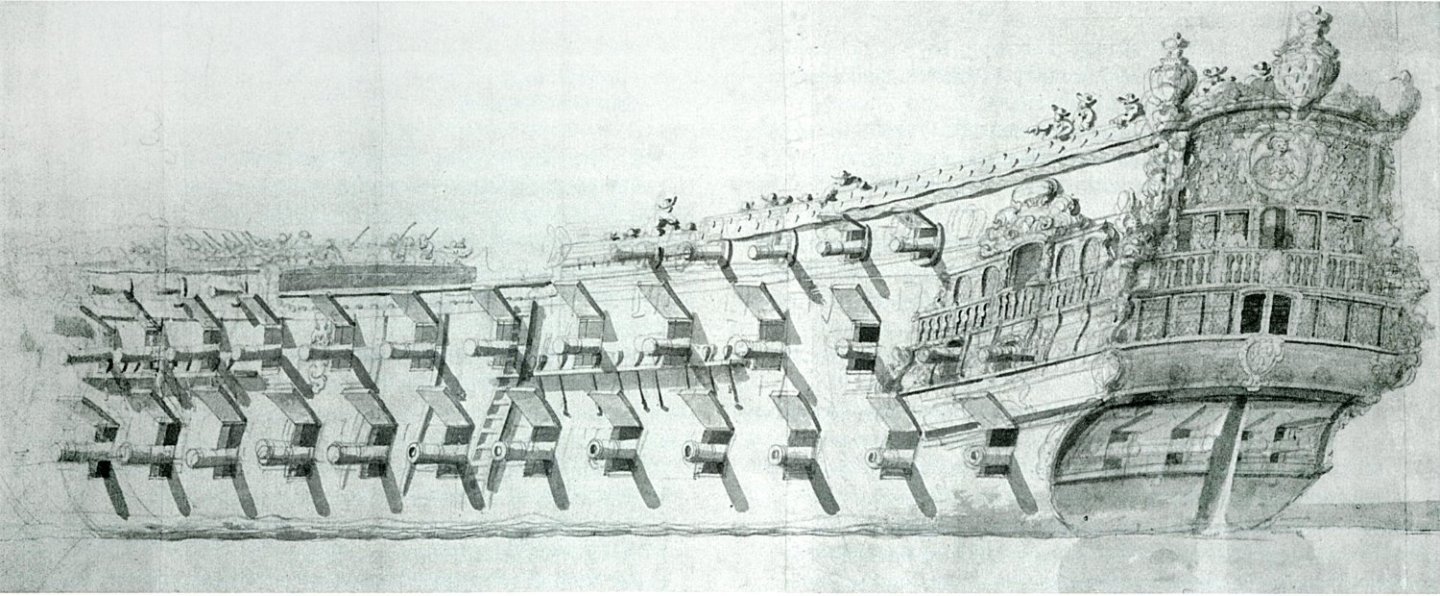

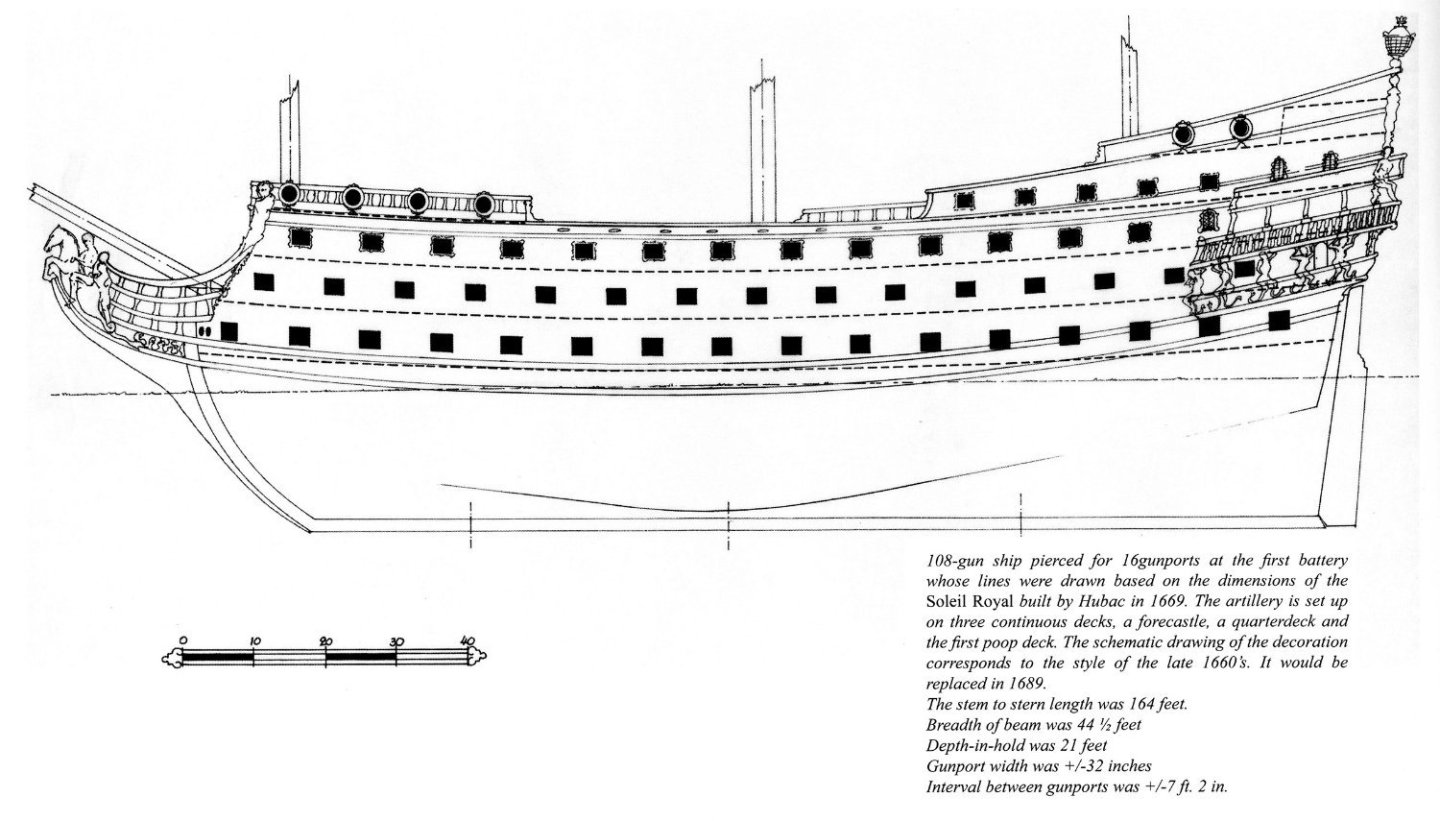

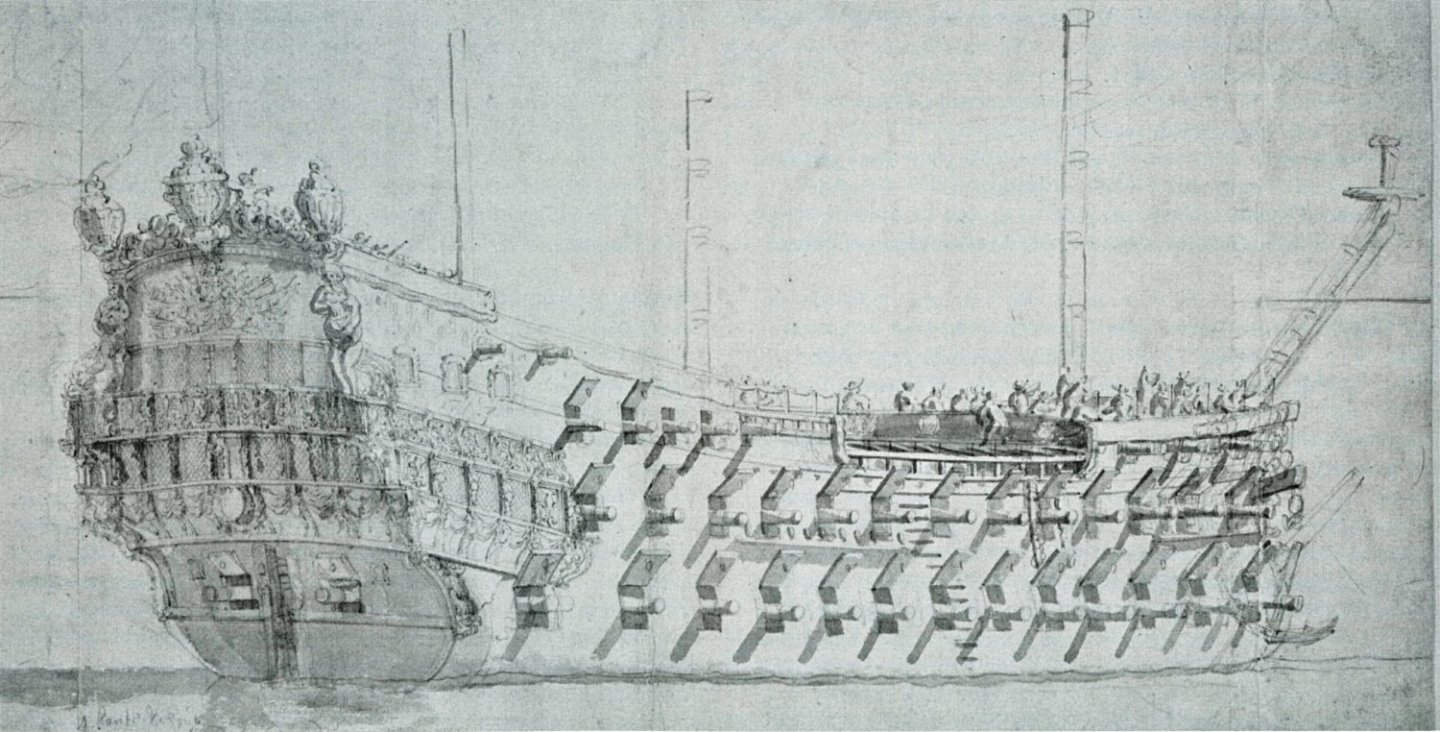

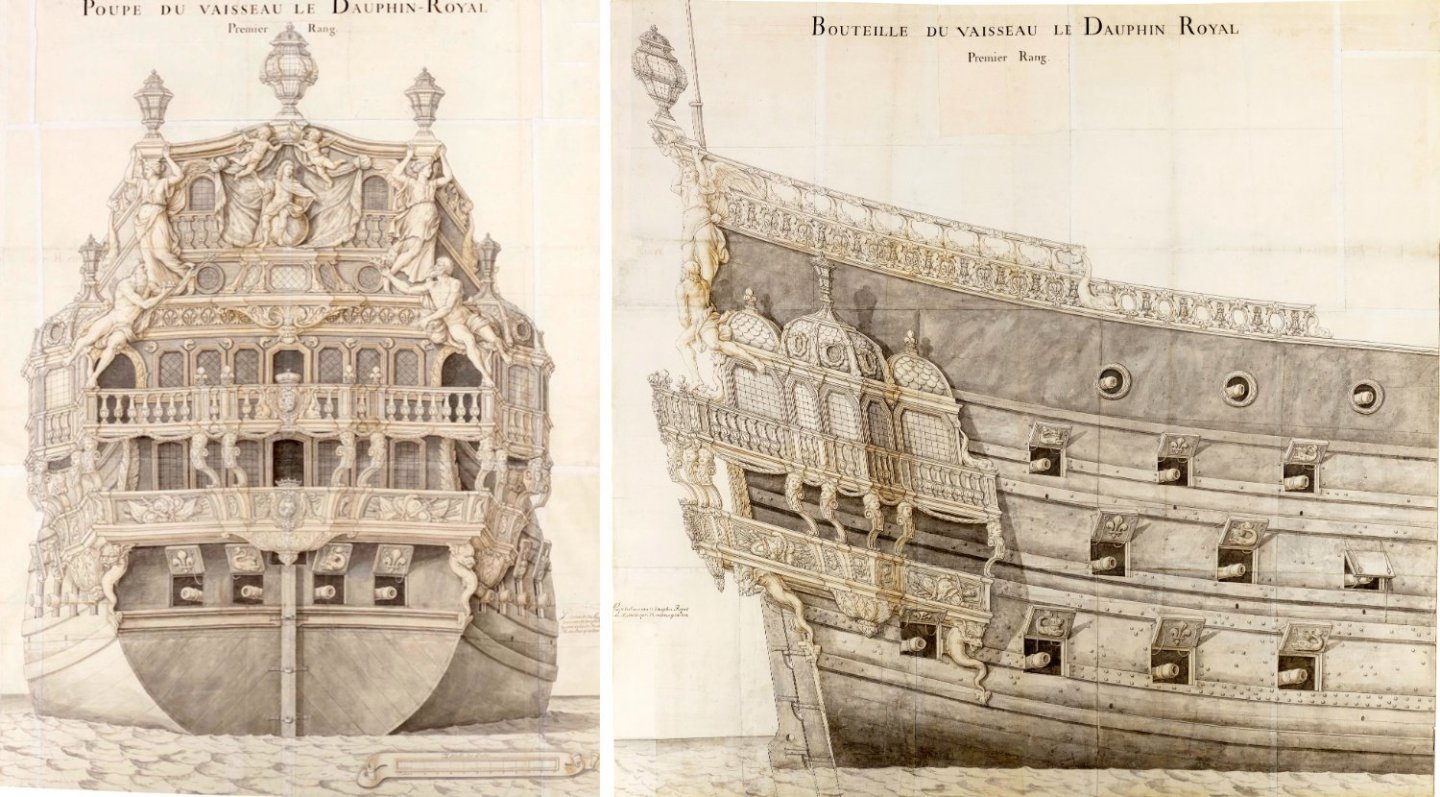

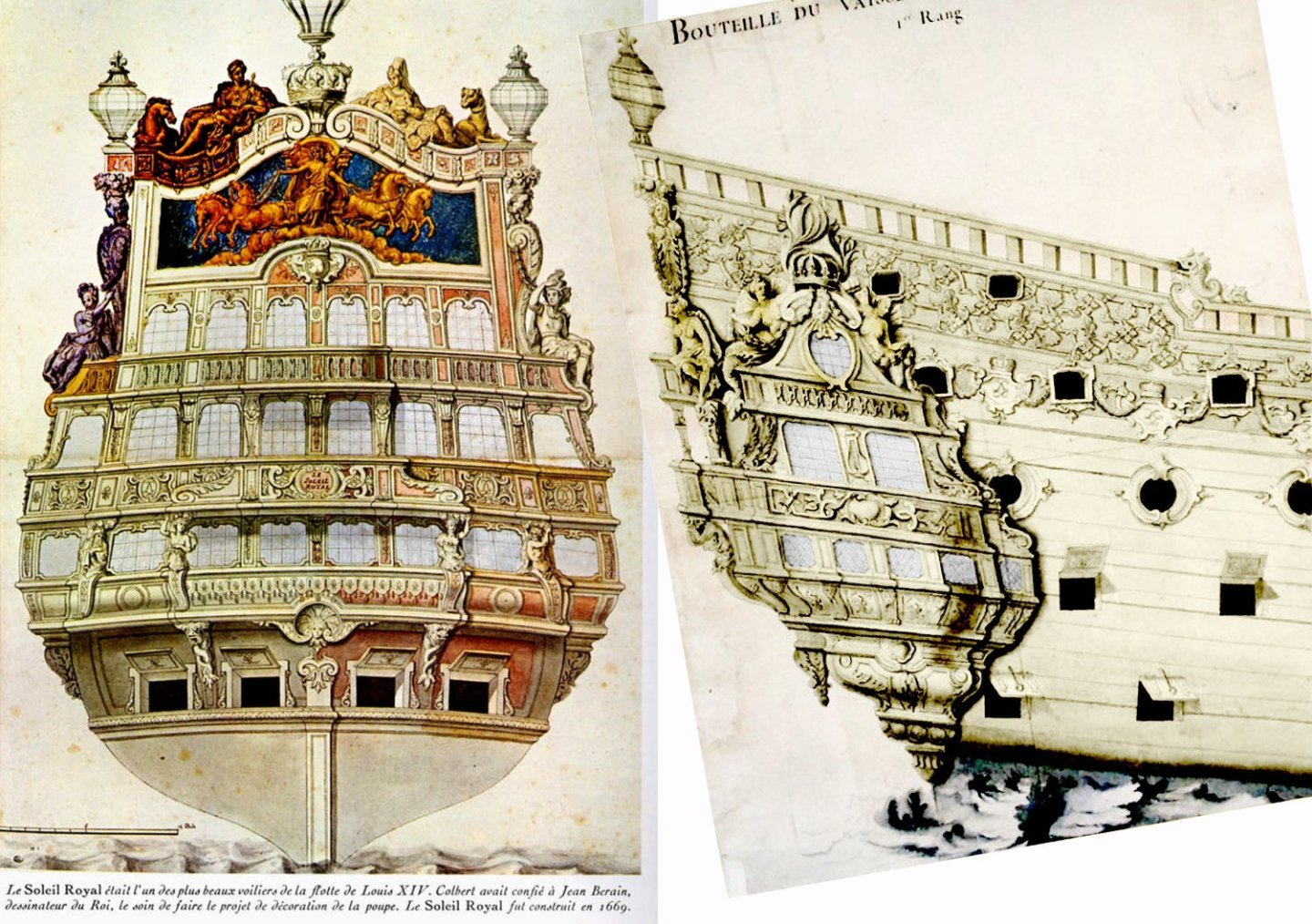

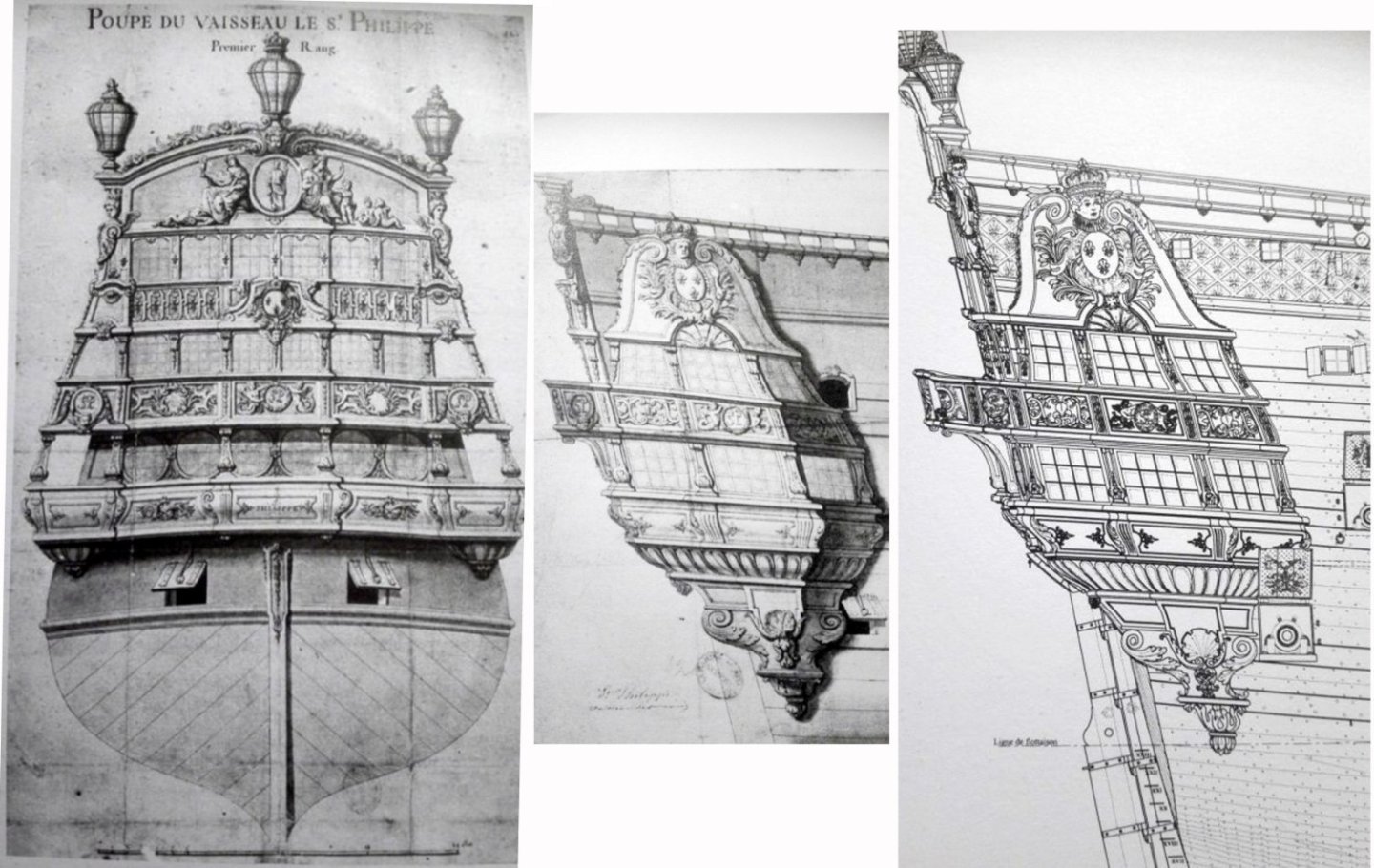

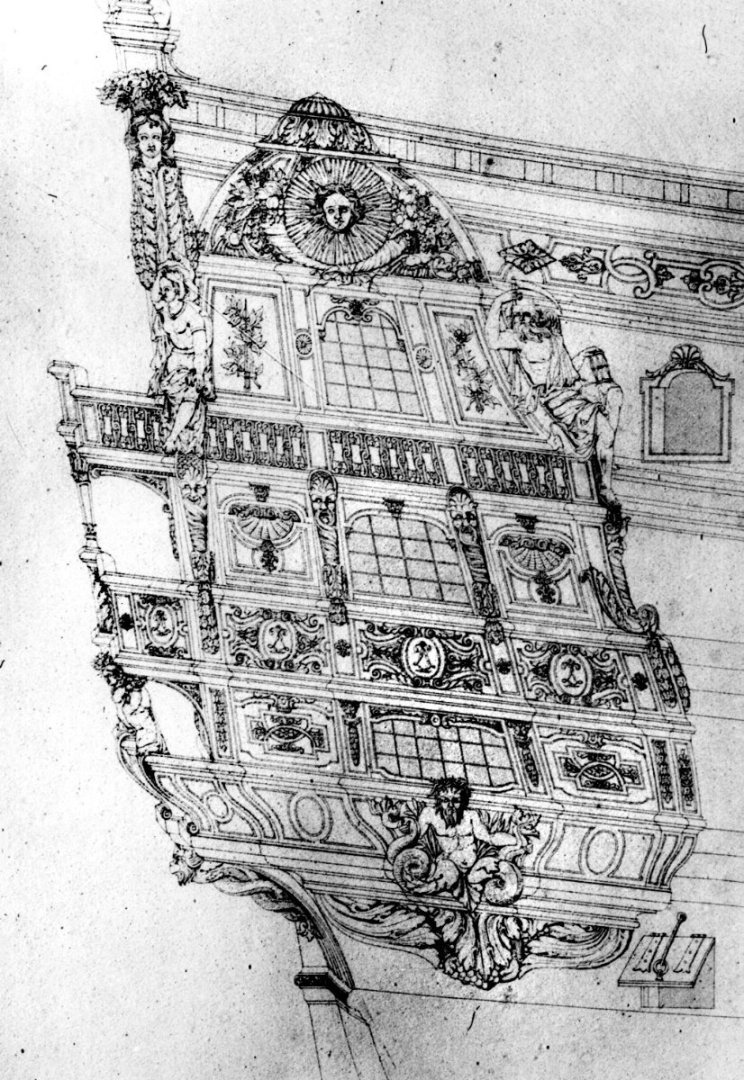

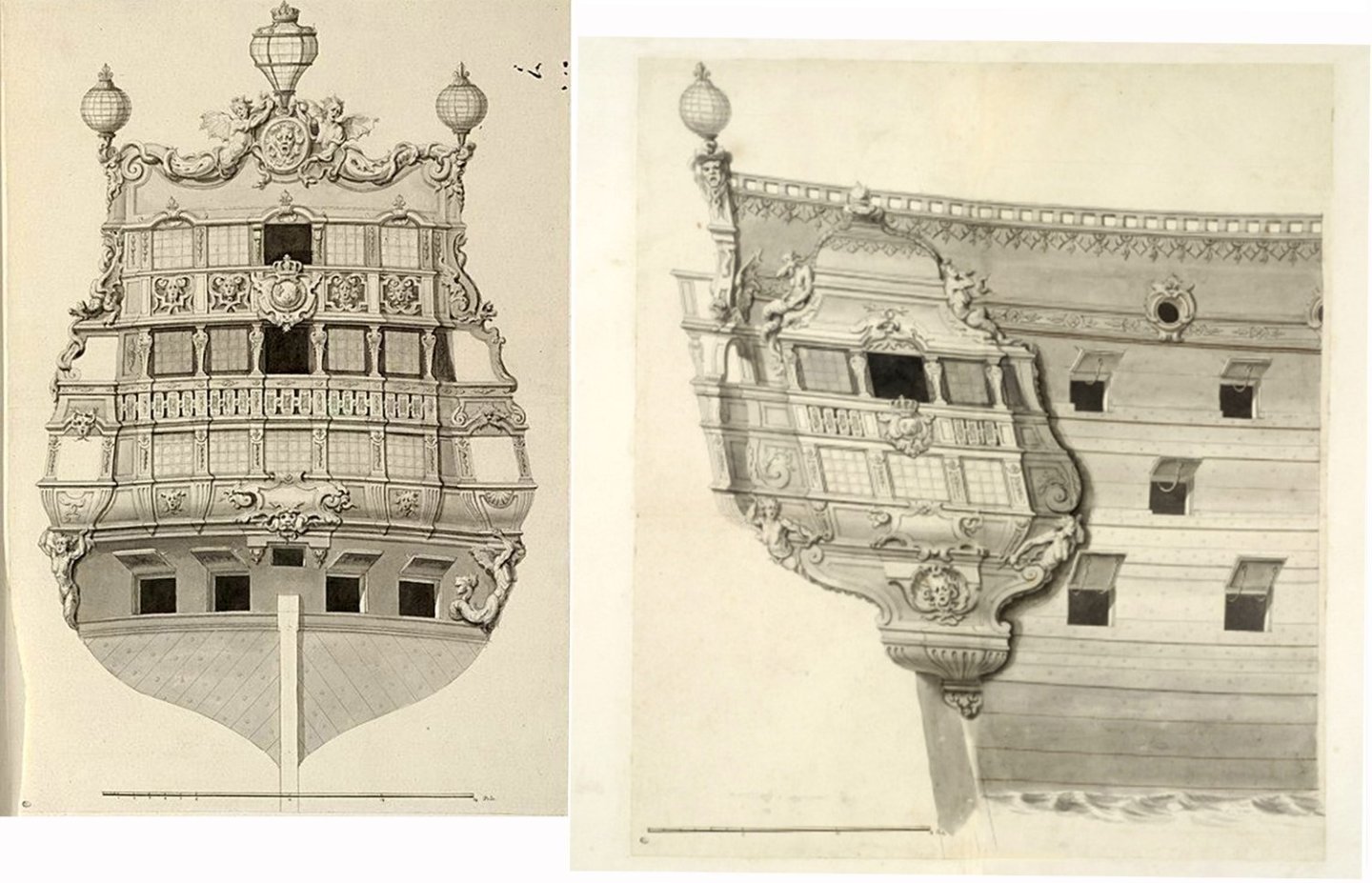

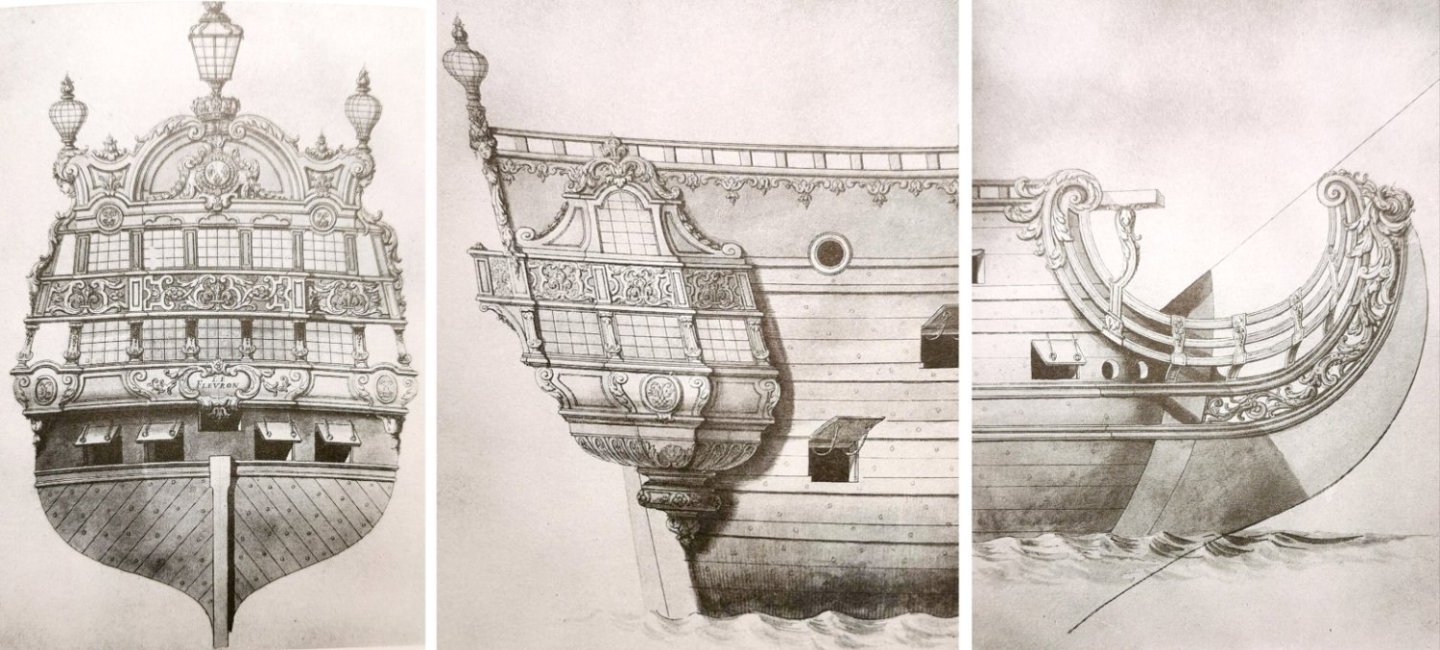

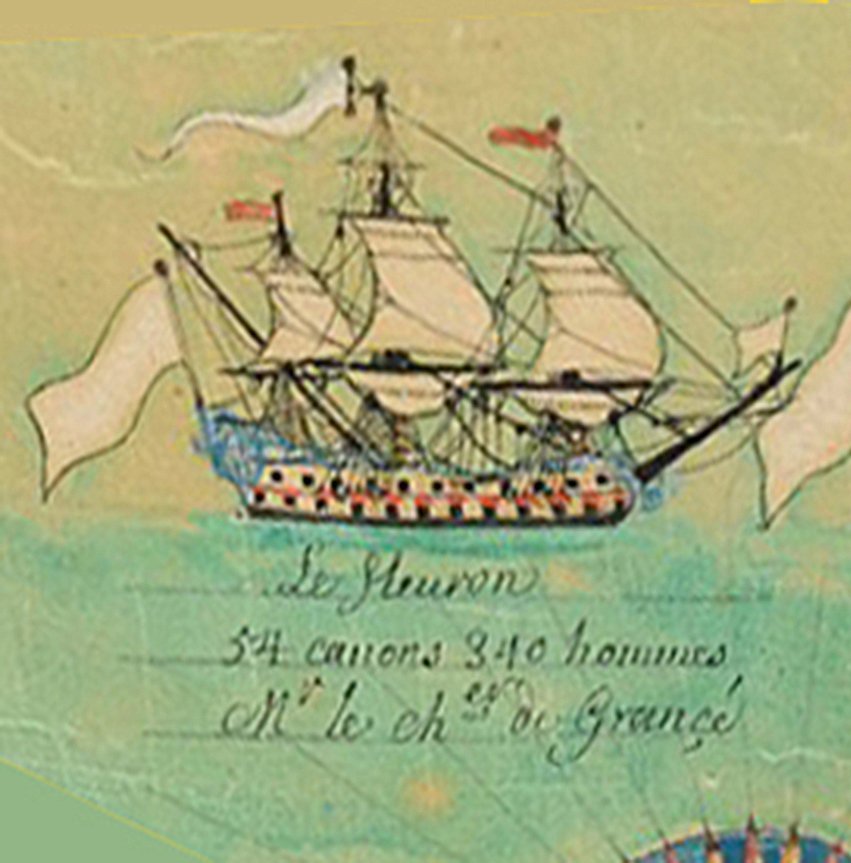

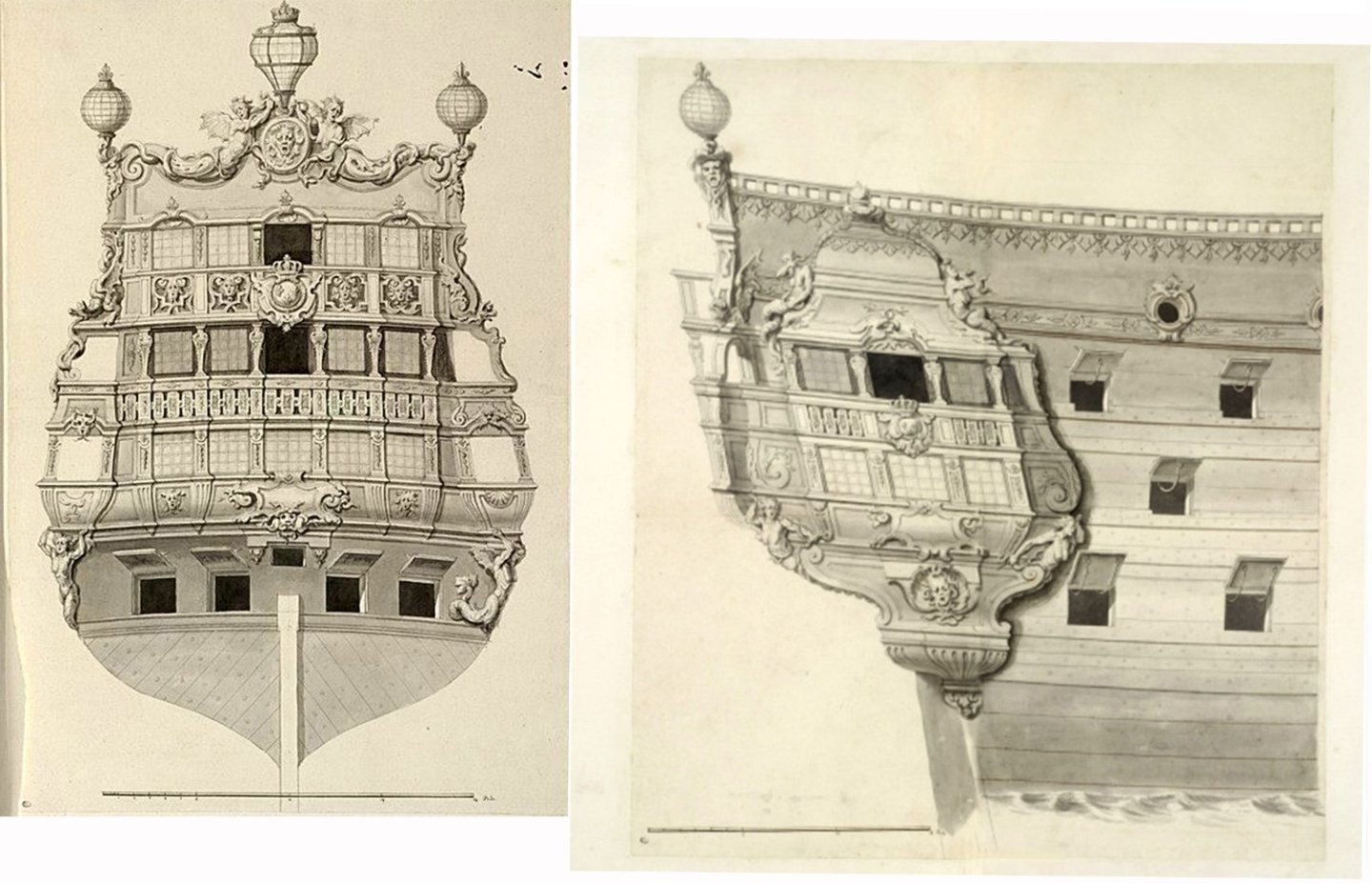

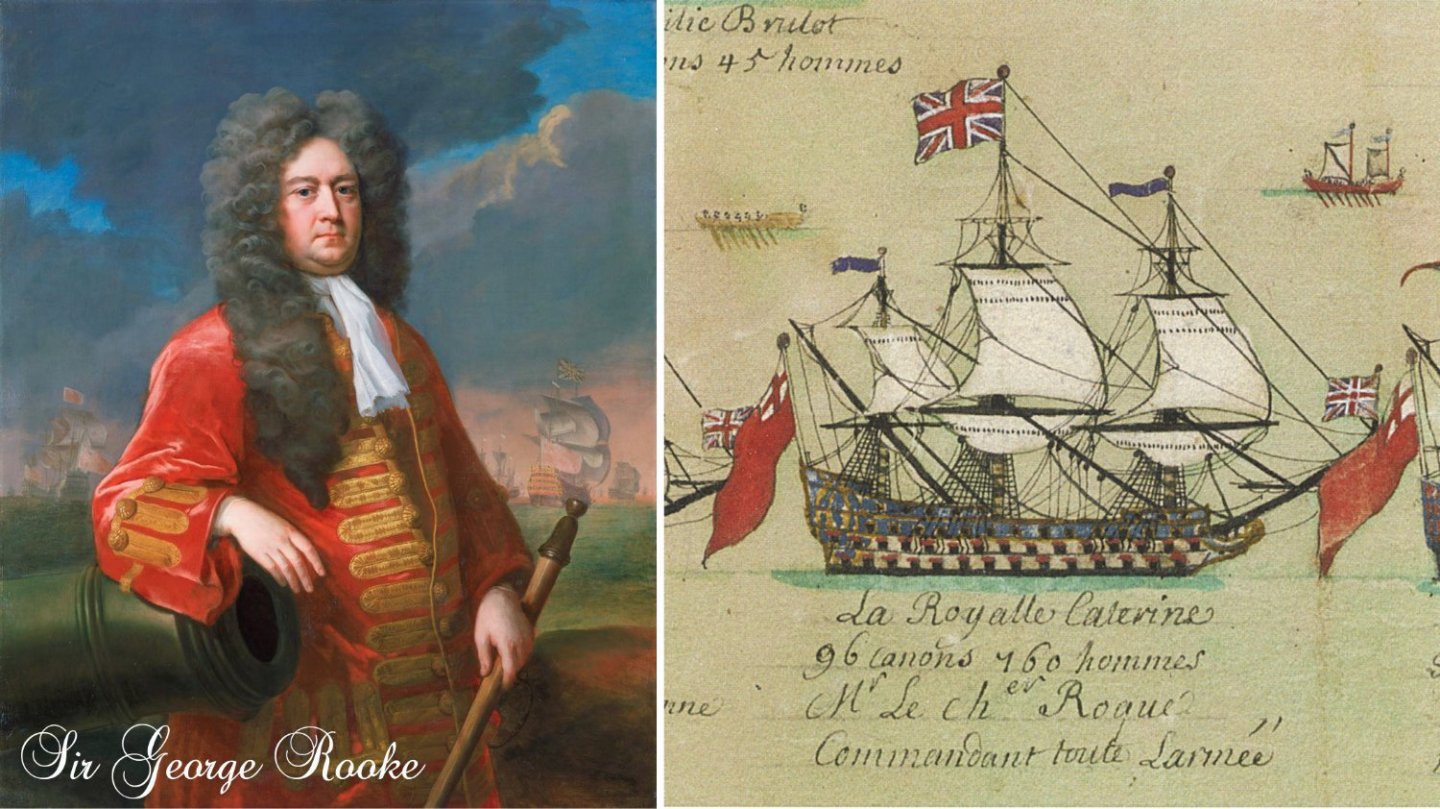

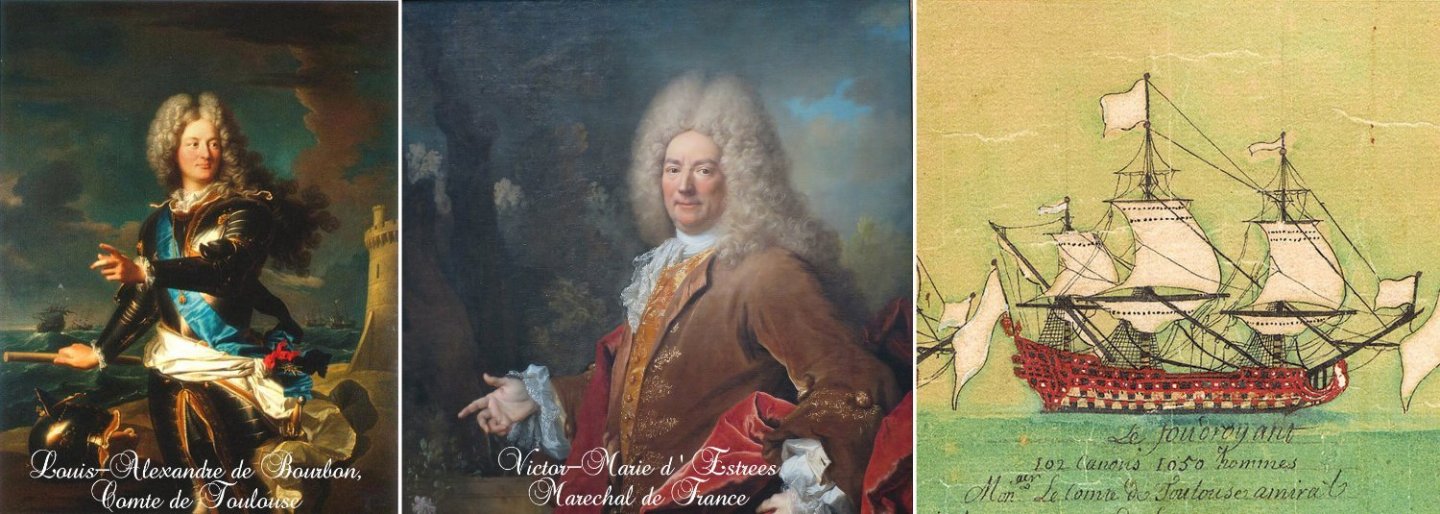

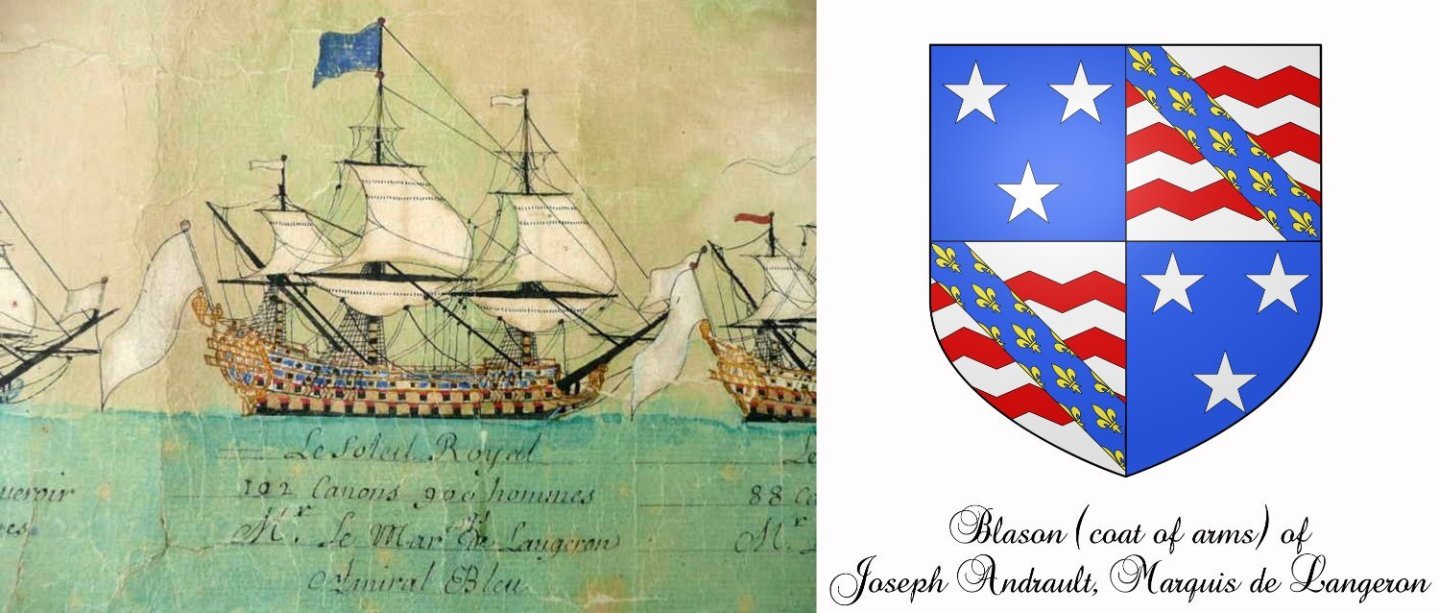

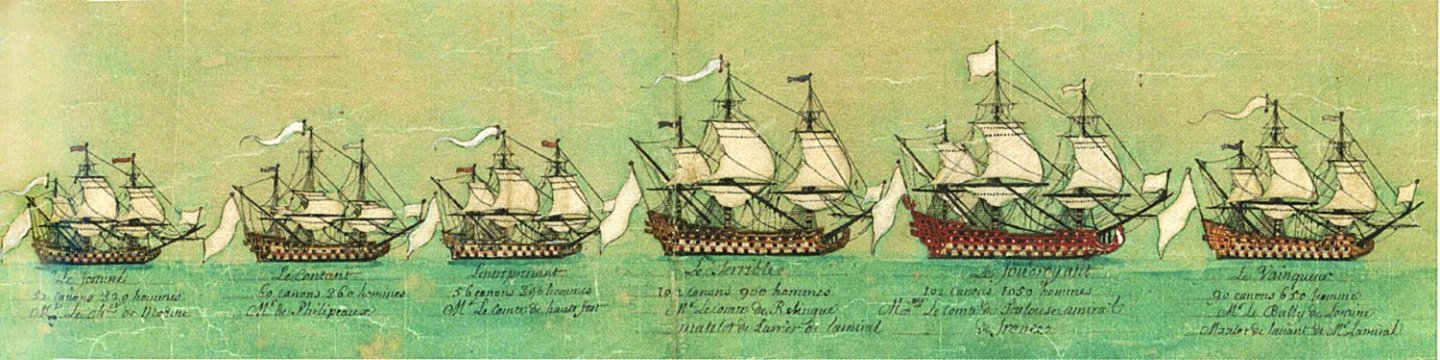

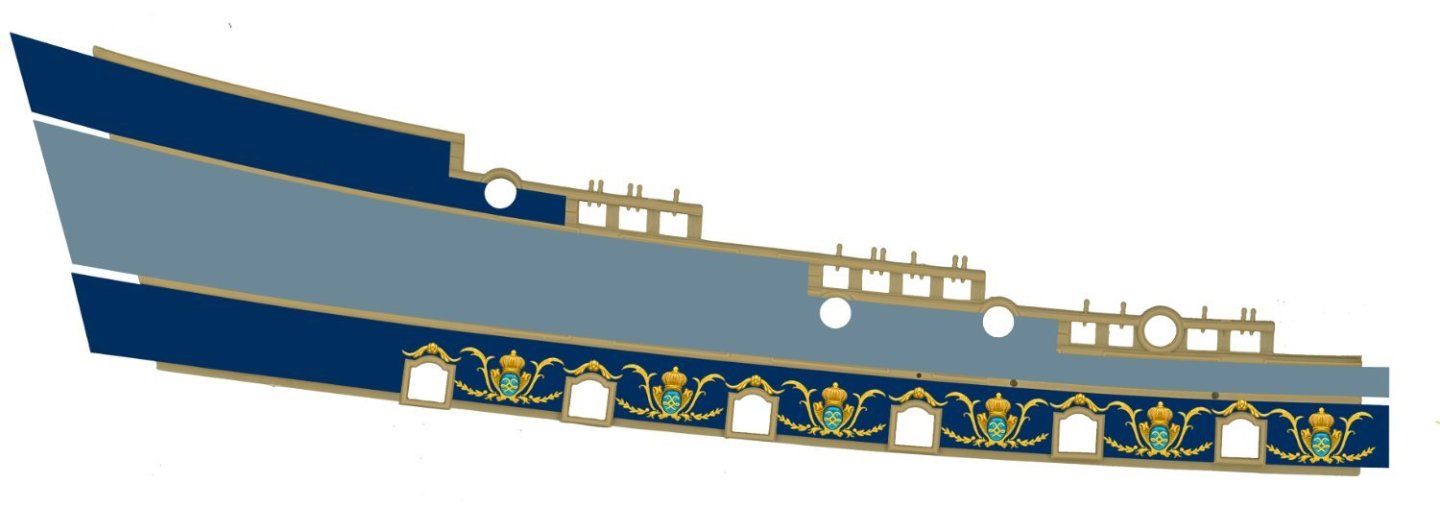

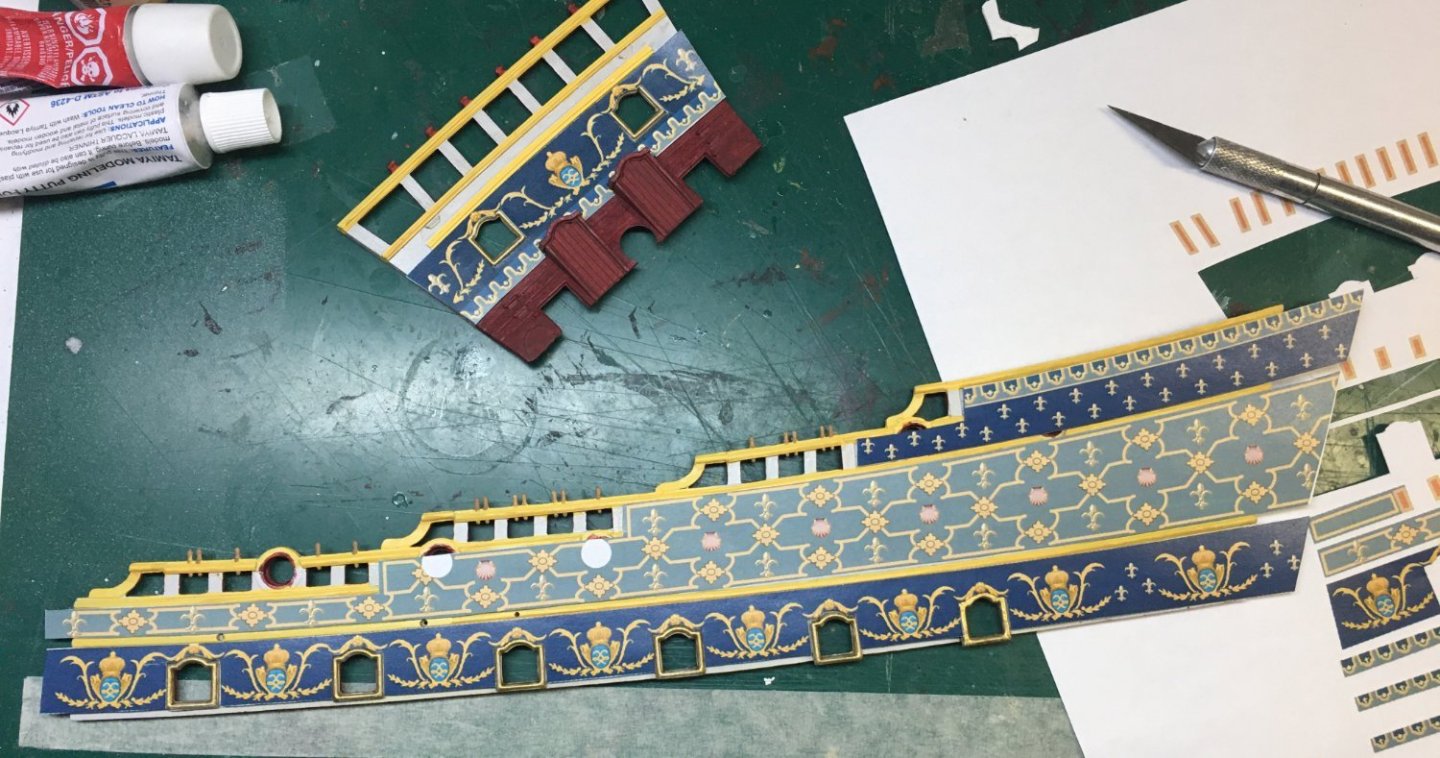

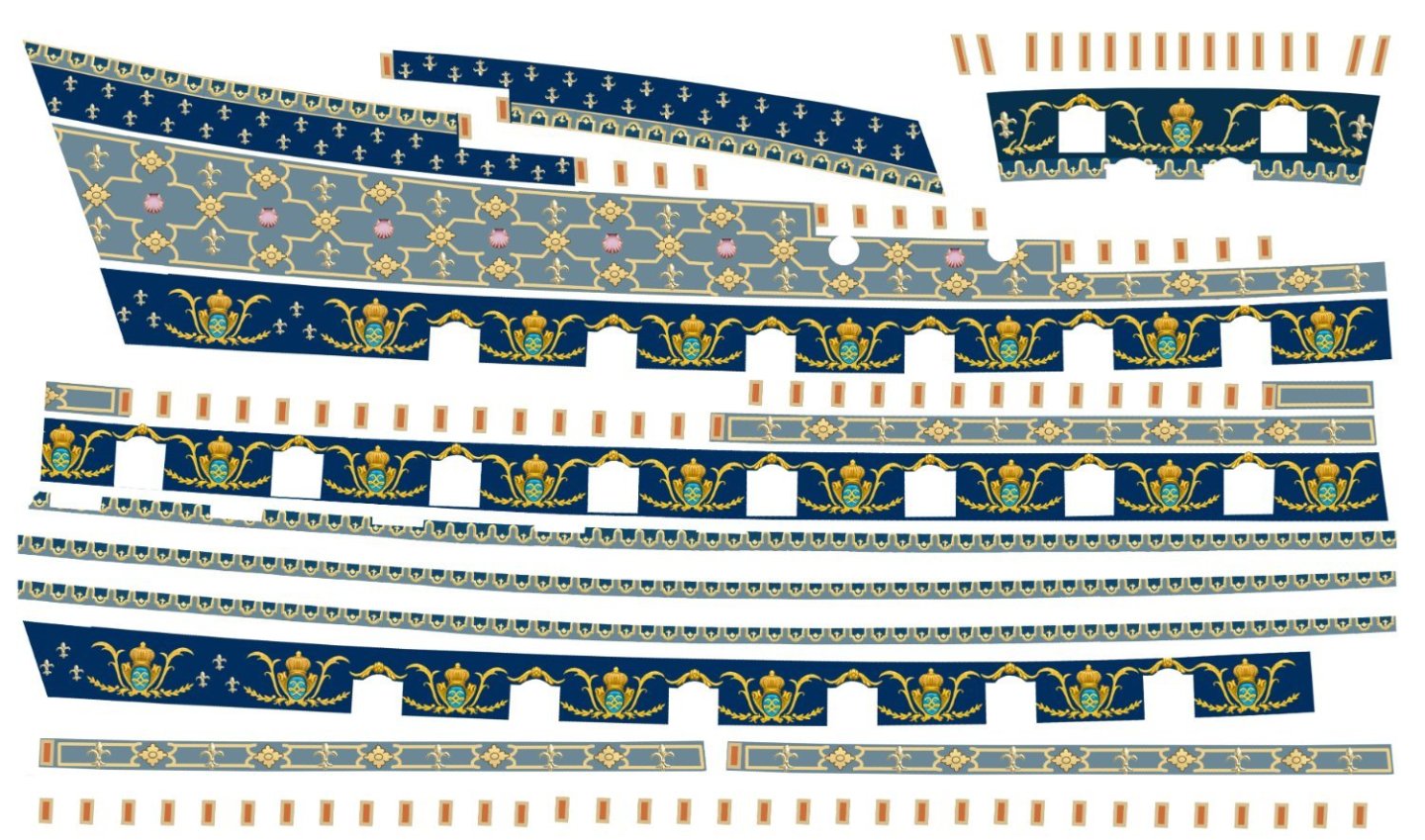

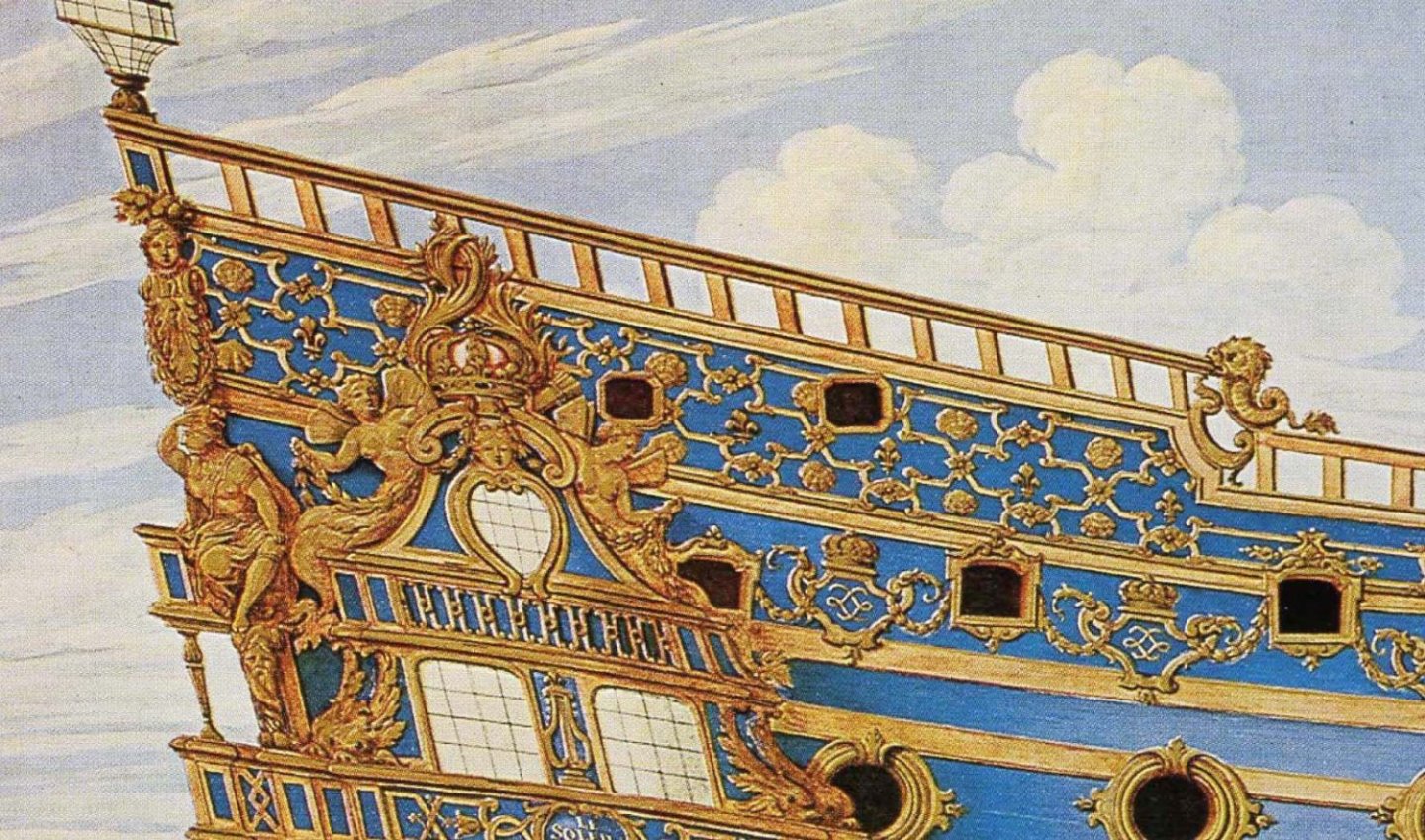

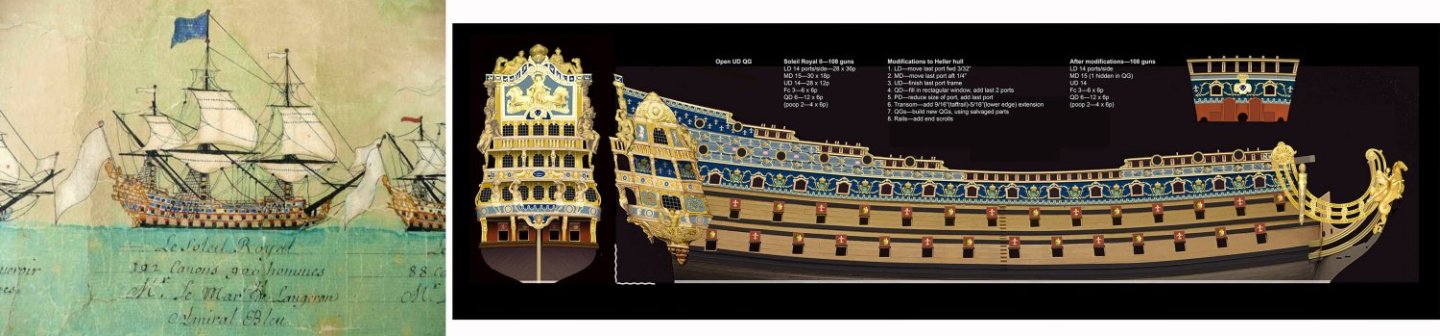

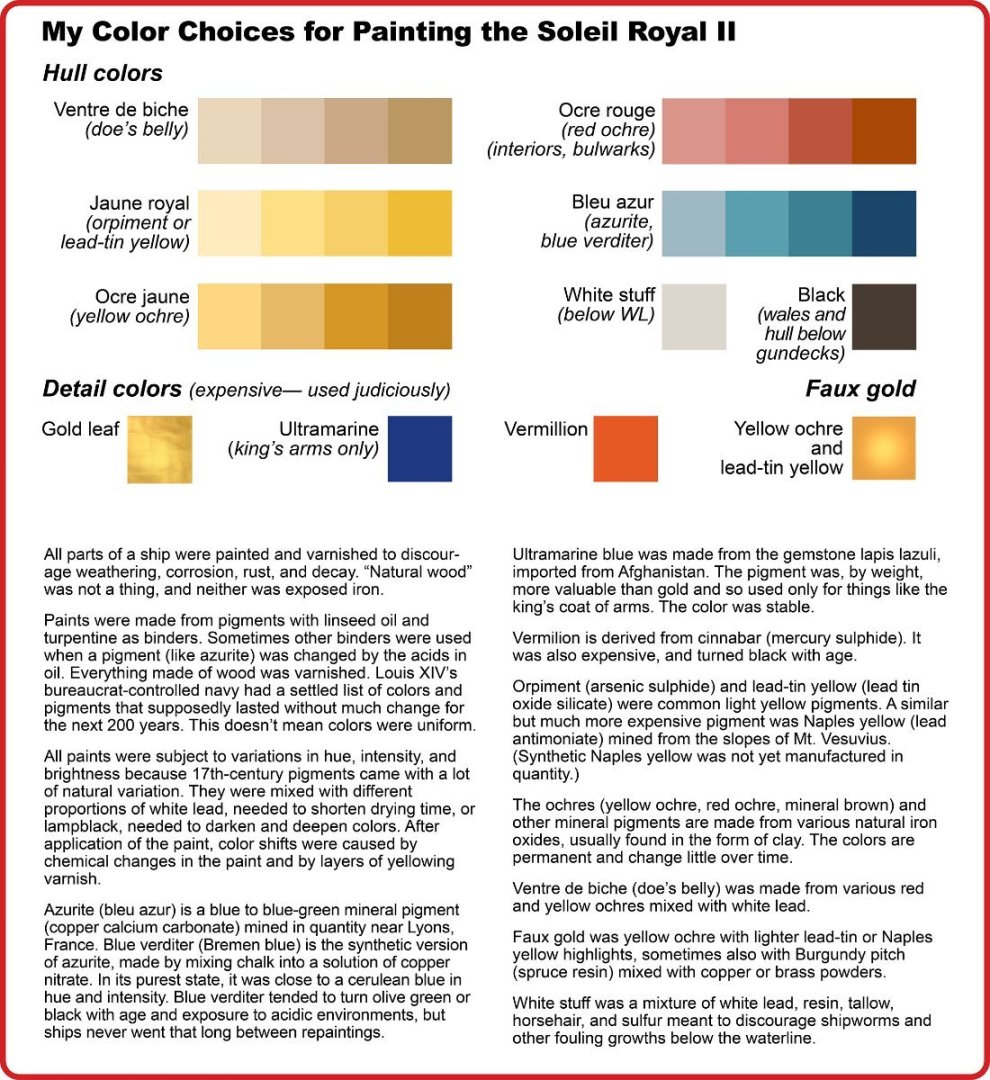

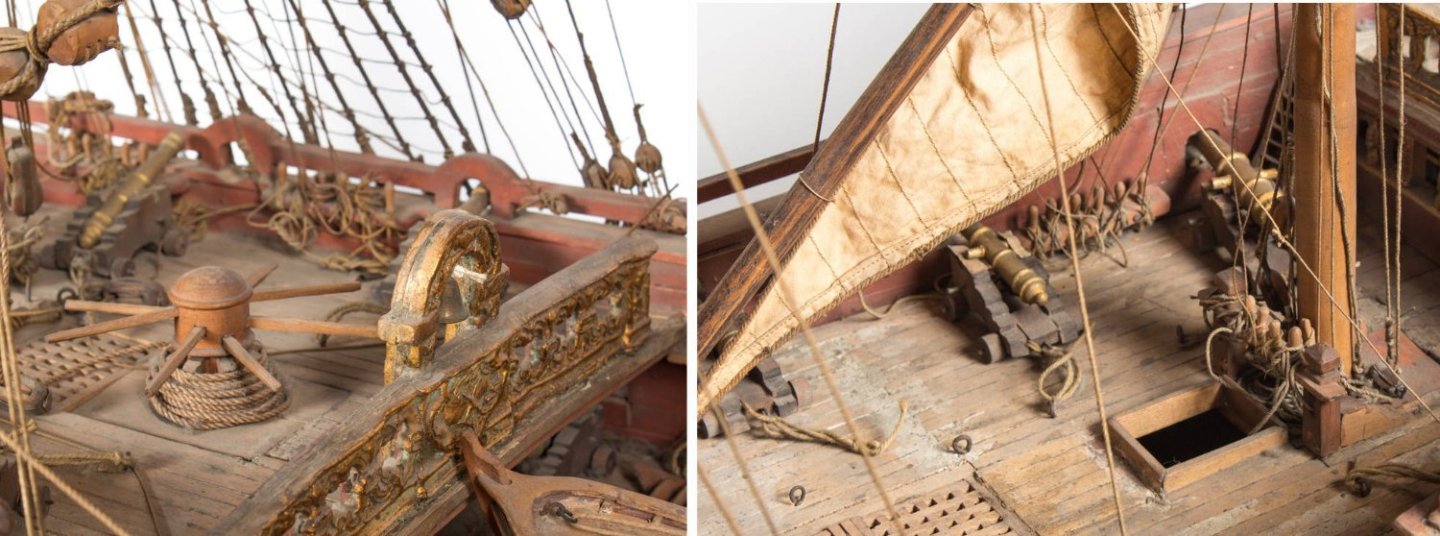

James A. Flood By the mid-1600s, it was taken for granted that warships had to look awesome. Decorations were no longer being painted or tacked on, but were being incorporated into the ship’s architecture. Louis XIV and his ministers were obsessed with having French ships look bigger and richer than their British counterparts. They hired the best artists in France to design statues, friezes, and decorative woodwork. Louis’s chief minion, Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, engaged artist Charles Le Brun to design statuary for Versailles, and when Colbert was given the additional position of Minister of Marine in 1669, he made Le Brun responsible for the decoration of the king’s newly-built fleet of ships-of-the-line as well. Le Brun set up sculpture academies in the shipbuilding centers of Brest, Toulon, and Rochefort to train the army of sculptors needed. The task of designing the architecture and decoration for the ships was assigned to the same artists who worked on the palace of Versailles, like Jean Bérain, and they churned out preparatory drawings to be given to the sculptors. The Italian-trained artist Pierre Puget was appointed head sculptor at the shipyard in Toulon after notable success decorating France’s Mediterranean galley fleet. His fanciful statues and designs for the new warships were inspired by Italian theater sets. This was an age when popular stage productions were growing more elaborate. Opera had been newly invented. Music specifically for the stage was being composed. The palace of Versailles had its own theater and the king and his aristocrats took part in the productions. Puget’s theatrical shipboard tableaux were immediately popular and widely copied. They looked a lot like opera backdrops. Two of Puget's ship designs. You kind of expect someone to come out on the balcony and start singing . . . . Puget’s sculptures were unquestionably awesome, but were also huge, heavy, and for the most part impractical. His boss, Le Brun, refused several of his designs with the note that they were “very handsome but not at all convenient for ships.” It was because of Puget’s extreme theatricality that Le Brun issued an order in 1673 indicating that sterns would not be allowed to carry figures so big that they affected the stability of the ship. Puget resigned in 1679, but one of the 1689 Bérain drawings of the Soleil Royal has the scribbled notation that it was made “apres Pierre Puget.” This caused at least one 19th-century French ship historian to attribute all of the Soleil Royal’s sculptures to Puget, in spite of evidence to the contrary. (Puget worked in Toulon; the Soleil Royal was built in Brest.) Instead of Puget, it’s fairly easy to connect the carvings on the Soleil Royal to the work of Charles Le Brun. Most of the figures turn out to be adaptations of Le Brun’s sculptural work at Versailles, especially his statues designed for the Versailles gardens in the grand commande (great commission) of 1674. The statues on the ship were originally made with Puget’s grandiosity in mind, but were later “adjusted” in size—in some cases replaced, in others, hollowed out—to reduce the weight and improve the ship’s stability. In a further effort to improve the ship’s handling, several of the larger statues were unshipped by Admiral De Tourville and left behind when the flagship went to war. These carvings were available for reuse on the Soleil Royal II, built in 1693. The new ship’s builder, Étienne Hubac, had been responsible for rebuilding the Soleil Royal I in 1689 and still had all of les garabits (templates and patterns) for the revised statuary. And so (we suppose), the second ship was decorated much like the first. There’s a weird thing about the symbolism and statuary on the Soleil Royal— well, weird for 1693— and that’s the ship’s total lack of Christian motifs and symbols. We’re used to thinking of the Baroque era as a religious age, one dominated by cardinals and cathedrals, sacred relics, bible-inspired art, witch-finders, and endless Catholic-Protestant wars. The hierarchy of the church was at the top of the social heap and kings wielded their power by divine right. The open-minded period of the Enlightenment was over half a century in the future. But without being terribly anti-clerical about it, along came Louis XIV with his aristocrats, retainers, bureaucrats, and artisans, and overt Christianity suddenly took a back seat to a revived interest in pre-Christian classical paganism. Instead of Christ, angels, and saints, the denizens of Versailles were more fascinated by gods, demigods, and caesars. In paintings, Louis had himself and his family portrayed as characters out of classical mythology. Louis and his over-extended family . . . . just another day of lounging around like Olympian gods. I’m sure the whys and hows are the subject of numerous books I’ll never get around to reading. For the time being, though, we can contemplate how all this influenced the decorations on Louis’s warships. What was in the art on the Soleil Royal? What did it represent? What did it all mean? Why was it there? First point—the art was meant to be symbolism. It consisted of elements meant to be read for their symbolic value by a largely unlettered population. Everybody back then was used to reading symbolism. It was all over their churches. Even if they couldn’t read, the populace knew all the bible stories by looking at the statuary, paintings, icons, altarpieces, carvings, and stained-glass that decorated their houses of worship. Every saint has his/her symbols for identification. Every condition or attribute had its own visual elements for storytelling purposes. The carvings on the Soleil Royal didn’t use Christian iconography, but the same principles applied. Artists like Le Brun even had textbooks of common iconography they could consult, like Caesar Ripa’s Iconologia, which described in detail what visual attributes went with which allegorical or historic figures. Caesar Ripa's Iconologia. Next point—this was Louis’s ship. Louis XIV was an absolute monarch, and when he famously proclaimed “L’État, c’est moi,” he meant it. The ships as well as the state were his, and the most important (gilded) artistic elements on the ship proclaimed his ownership. First, there was his Bourbon coat-of-arms on the bow and the stern, Azure, three fleurs-de-lys or—three gold fleur d’lis on a blue field, topped by a crown to indicate royalty. The fleurs would be repeated many places on the ship. On my model, white, open-faced fleurs (lilies seen from the top) are used on the quarter deck/forecastle level. There was also the king’s monogram, two intertwined, mirrored “L”s, also topped with a crown and surrounded by acanthus stems and chains of bellflowers, on the length of the upper gundeck. On the quarter galleries, the monograms are surrounded with a classical-antiquity-inspired laurel crown. You couldn’t go ten feet in any direction on this ship without being reminded it was Louis’s. The name itself, “the Royal Sun,” was one of his self-aggrandizing unofficial titles. Whose ship was it again? Louis himself is represented several times. The beaming face of the Sun King surrounded by solar rays appears on the headrail medallions and on the dormers of the quarter galleries—looking out from the four quarters of the ship. These were all elements I chose to paint as if they were gilded on my model. The same devices are always gilded where they appear at Versailles. Right, the face of the Sun King at Versailles, same as on the ship. Louis also starred in the most distinctive piece of décor on the ship—the Apollo solar chariot frieze on the stern-plate. The zodiac frieze above the chariot and the clouds below it show that the tableau is supposed to be occurring in the heavens, far above lowly Earth. Louis, as Apollo, drives the solar chariot on its daily celestial path. He's not carrying the sun. He is the sun. The gold leaf would have blazed in daylight. The frieze was patterned after the Apollo fountain, a major sculptural group by Charles Le Brun in the gardens of Versailles. Louis was supposedly a devout Catholic who did a lot to enhance the power of the church, including expelling all French protestants. I don’t know how he managed to reconcile his devotion with presenting himself as an Olympian god. Charles Le Brun's Apollo fountain at Versailles. Charles Le Brun was responsible for the other sculptural groups on the ship’s stern. He designed four statues for the gardens of Versailles to represent the four seasons. Variations of these serve as pillars between the ship's middle deck and upper deck balconies. Louis was being advertised as literally, a “king for all seasons.” Le Brun's original design drawings for the Four Seasons, Autumn, Spring, Summer, and Winter. The statues were executed by hired sculptors. I don't know where or if the statues survived. They no longer seem to be at Versailles. At the bottoms of the quarter galleries are mermen, two split-tailed tritons from classical mythology. These were often used on French ship décor. Their function was to hail Louis as master of the seas. The ship’s figurehead is a classical winged sea nymph on the back of a sea horse (literally, a mer-horse with a fish tail)—a herald for the procession of royal emblems to follow. Another nautical-themed element was the bevy of scallop shells. The ribs on the scallops represented the sun’s rays, so they worked as one of Louis’s solar symbols as well as a symbol of the sea. Surrounding the stern plate are allegorical figures representing the four continents (as they were known at the time), representing the wide overseas reach of French power. Reclining atop the zodiac frieze above the Apollo chariot are the figures of Europe, port, in classical garb with a horse, and Asia, starboard, in “eastern” dress, a turban, and a camel. On the lower port of the stern-plate is a female figure representing the Americas, in a straw skirt and feather crown. Starboard is the figure of Africa, with a distinct elephant-head headdress. These, too, are variants on Le Brun’s Versailles sculptures. The figures of the Americas and Africa on the Soleil Royal have exactly the same headdresses. This and the Apollo's chariot frieze are the strongest links between the ship's sculpture and Charles Le Brun. Pierre Puget—sorry, nope! Charles Le Brun, the Four Continents. Still on display at Versailles. In the Heller kit, I felt that the two figures on the lower stern-plate corners were too large and not very attractive to boot. I needed a smaller Africa and the Americas. I went looking for other model figures to use. What size was okay? I thought 1/48 (O scale)—about 10–12 feet in 1/100— was about the largest that would be reasonable. After an internet search, I focused on some 3D-printed figures by a company named Printle on the Shapeways.com website. Some were copies of classical statues. Some were female nudes. They were cheap enough; I ordered a few. The quality was good. The plastic was easy to cut, so I could make adjustments to the positions of arms and legs. I added clothing (not much, admittedly) and headdresses with scraps of styrene. The figures might not be identical to the ones in the Bérain drawings, but neither is the ship. I think these figures work fine. Shapeways also supplied me with figures to make the two missing statues shown on the Cherbourg Library drawing of the quarter galleries. The starboard one (the only one shown in the Cherbourg drawing) was Kronos, “Father Time,” the Greek-mythology titan, first king of the Olympian gods, whose symbols were a scythe and an hourglass. The figure I got from Shapeways was a standing figure of Zeus. I cut and re-glued the figure at neck, waist, and knees to give him more of a sitting posture and replaced Zeus’s thunderbolt with Kronos’s scythe. Why was Kronos there? What did he represent? What did he have to do with the sun-god Apollo? I don’t know if I ever found a good answer. In mythology, Kronos reigned during the “golden age” (this is where we get the term) before he was slain and replaced by his son Zeus, who in turn was the father of Apollo. So Kronos was Apollo’s grandfather. And his “golden age” might be considered to have returned under the reign of his “grandson,” Apollo-Louis. It didn’t make sense to repeat the same statue on the port side. Another accompanying figure was needed. What figure went along with Kronos, though? I decided it had to be Rhea, Kronos’s consort, first queen of the gods, Apollo’s grandmother, who served as midwife for the sun-god’s birth. Rhea’s main symbolic attributes were a mural crown (representing fortress walls) and a chariot drawn by lions. I opted to give my figure the crown and forget about the lions. Again, I used a nude Shapeways figure and dressed her somewhat with scrap styrene. I think I’ve caught everyone up on my Heller model to the present. Posts from me are going to get less frequent from now on. I’m busy right now working—and re-working—the masts and rigging. I’m on my fourth try at installing foremast shrouds. Man, I thought building the hull was tough. It’s nothing compared to the complexity of the rigging. Slow process. I thought I’d be done with this model in a year. Now I’m giving it two. My model has grown a beard. It’s all the lines running from the forecastle pin rails and deck cleats. I figured I’d better tie them in before the foremast shrouds go on and get in the way. I belayed the lines according to a rigging plan, so I know what each line is and where it is going to go once the masts and yardarms are up. Most of the lines are three feet or more in length. As far as postings go, there’s still a discussion of deck furniture to do, which I’ll put off once more. And my rigging diagram is in a constant state of re-evolution as I absorb stuff from Jean Boudroit's monograph The Three-Decker of the Chevalier De Tourville. You’ll find out more about that next time, whenever that will be. With the holidays coming up, it’s hard to tell how much modeling time I'll have. Happy Meleagris gallopavo day. The bird formerly known as turkey. Let’s all be respectful with our culinary nomenclature this Thanksgiving and eat some nice roast gallopavo with stuffing. And have fun building and rigging model ships over the holiday. Speaking of turkeys—

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

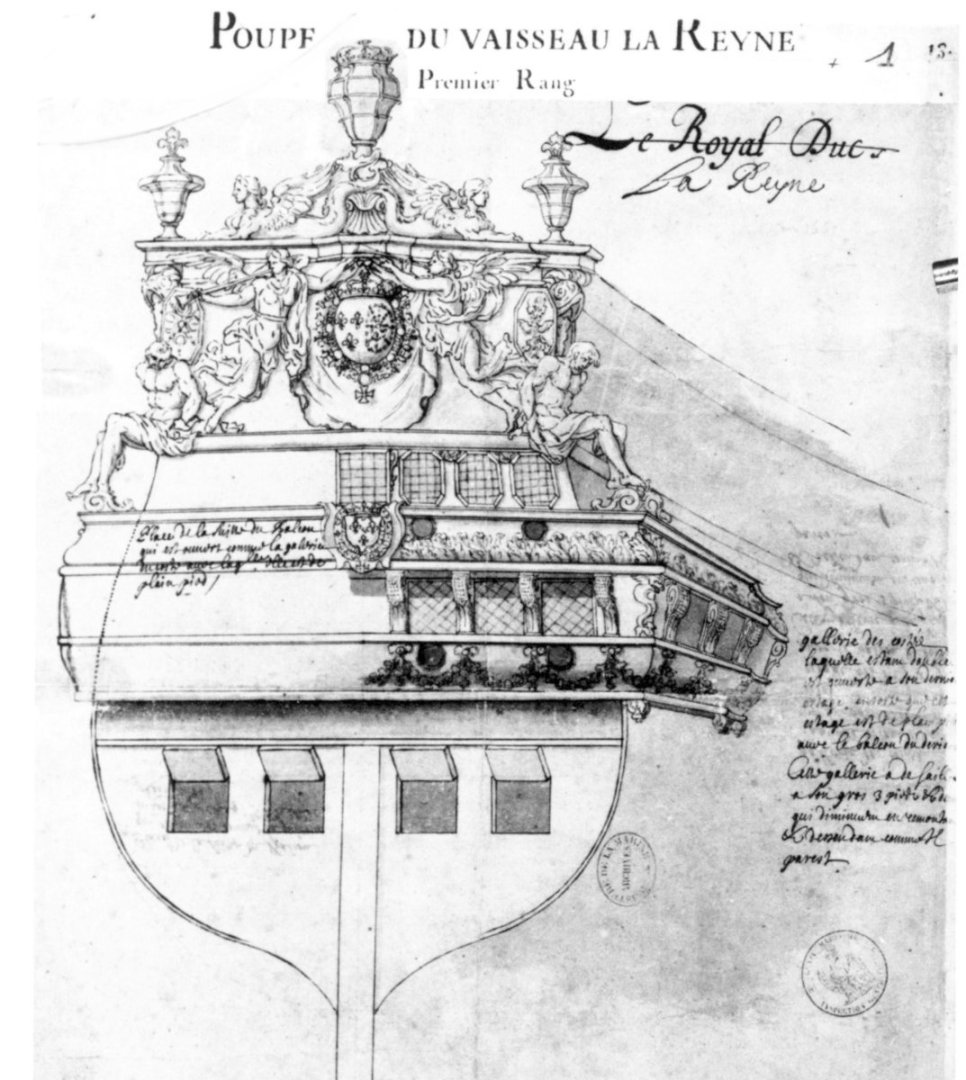

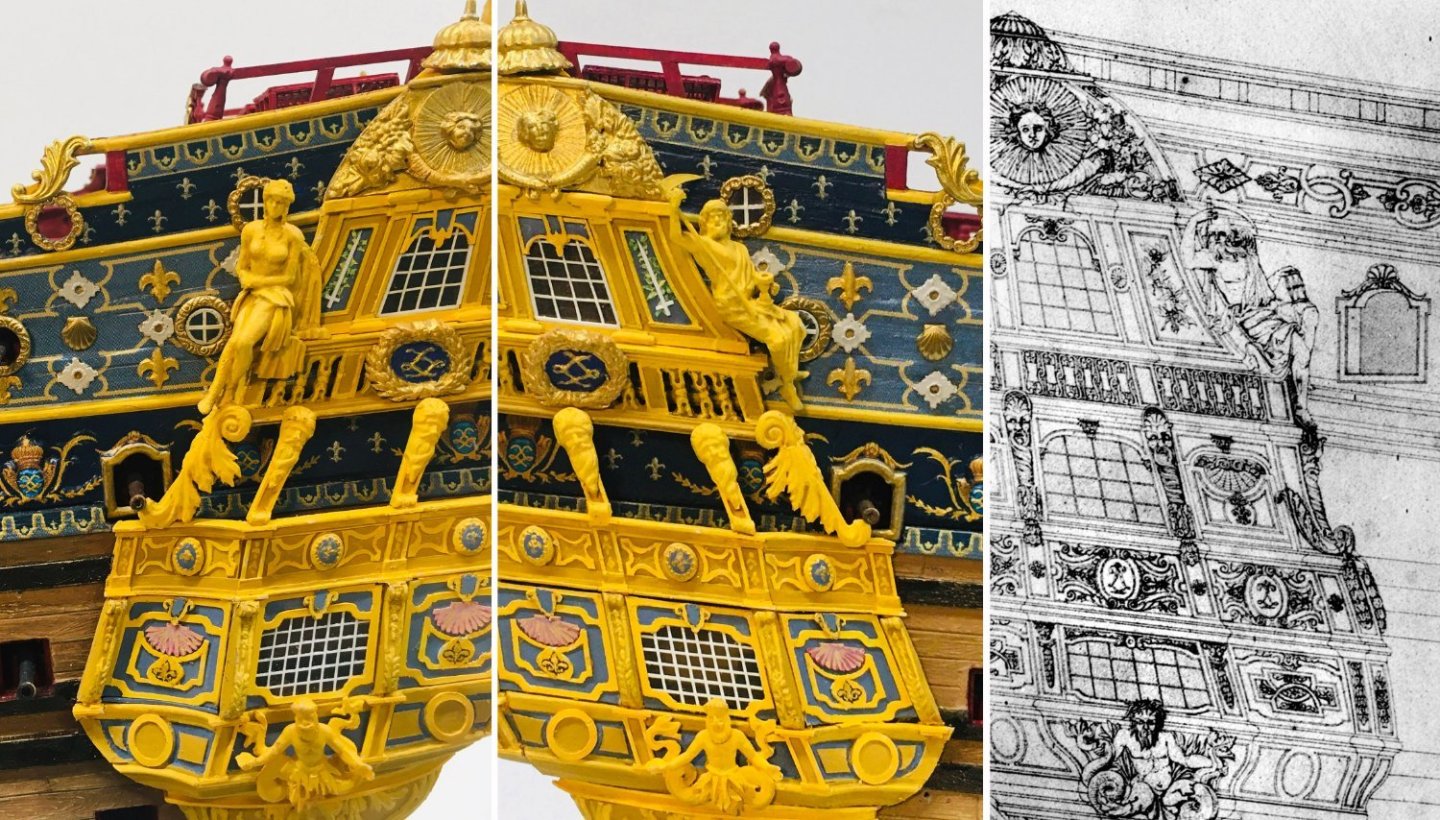

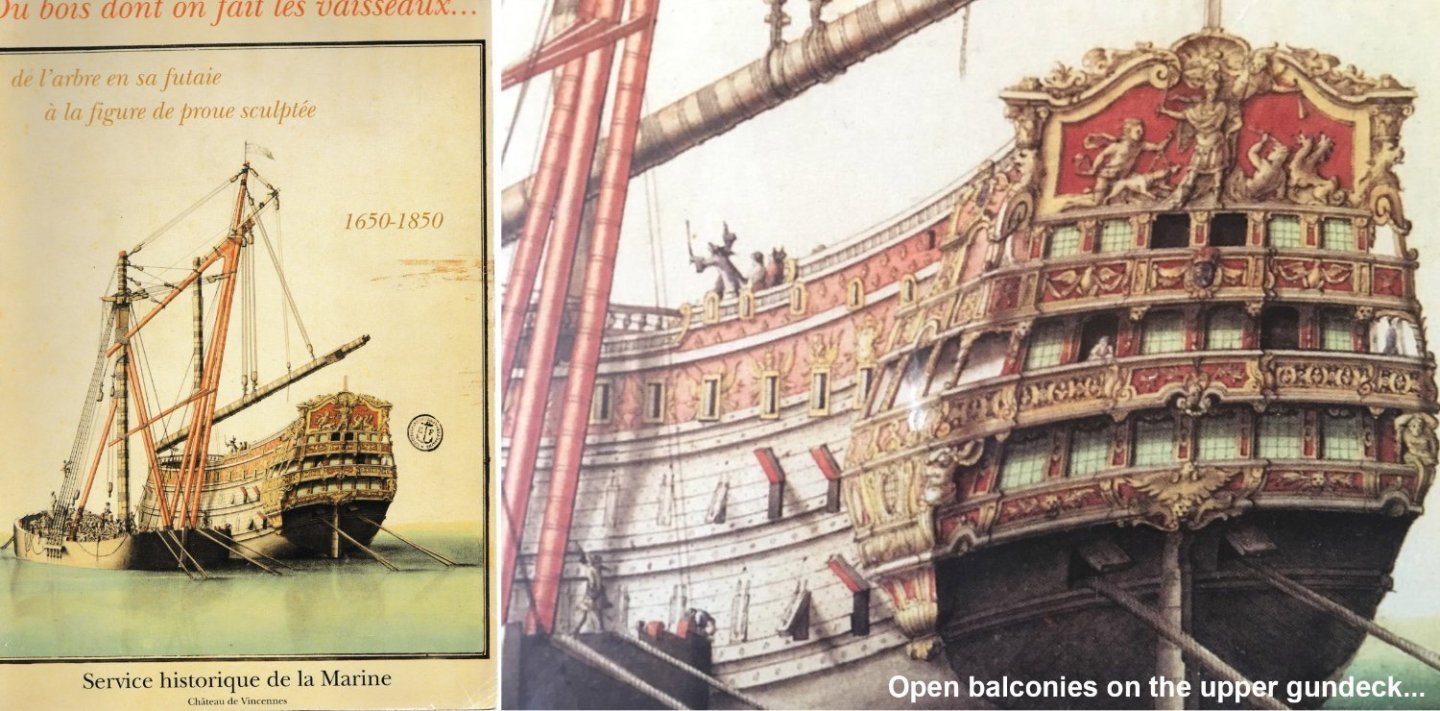

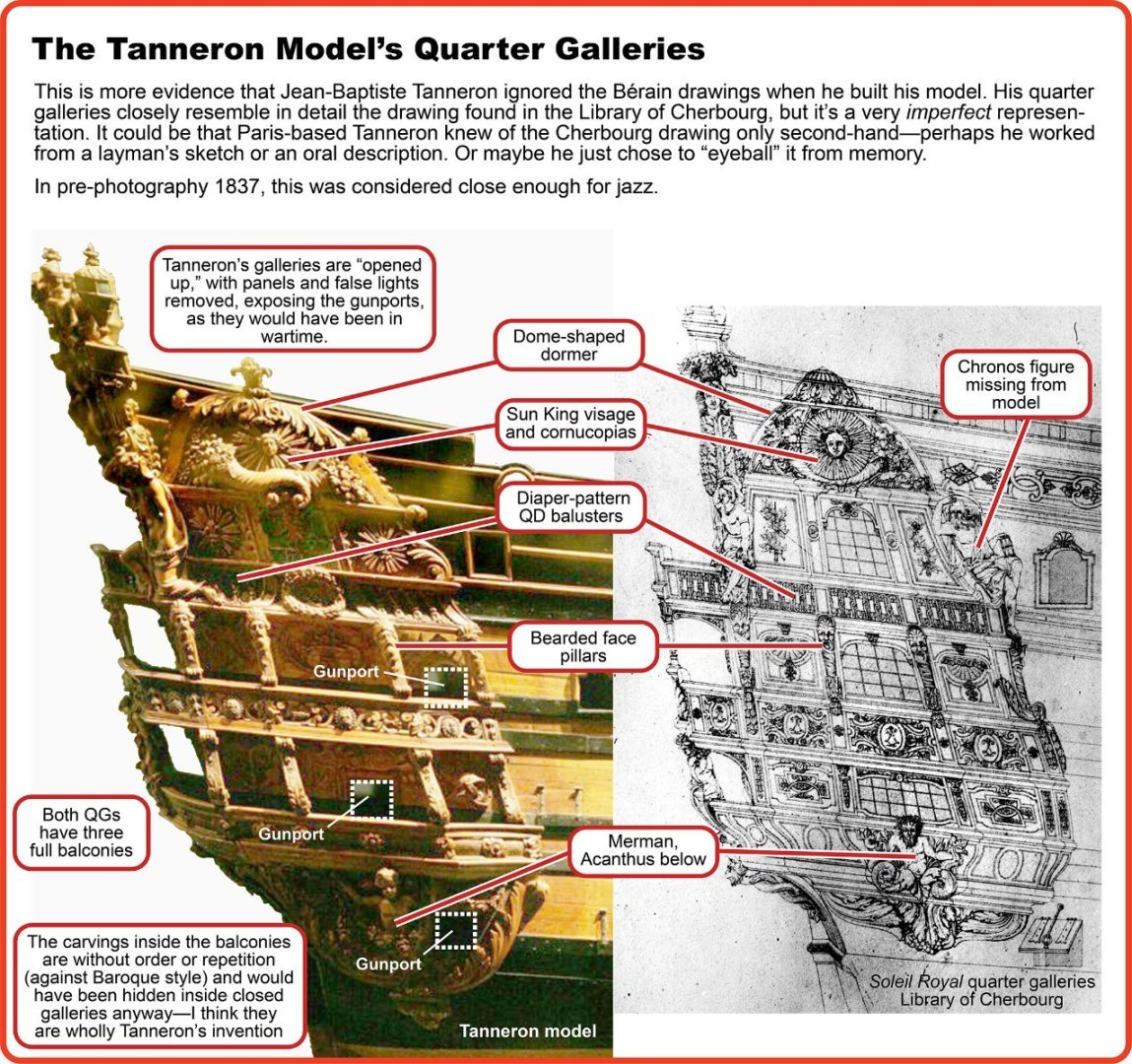

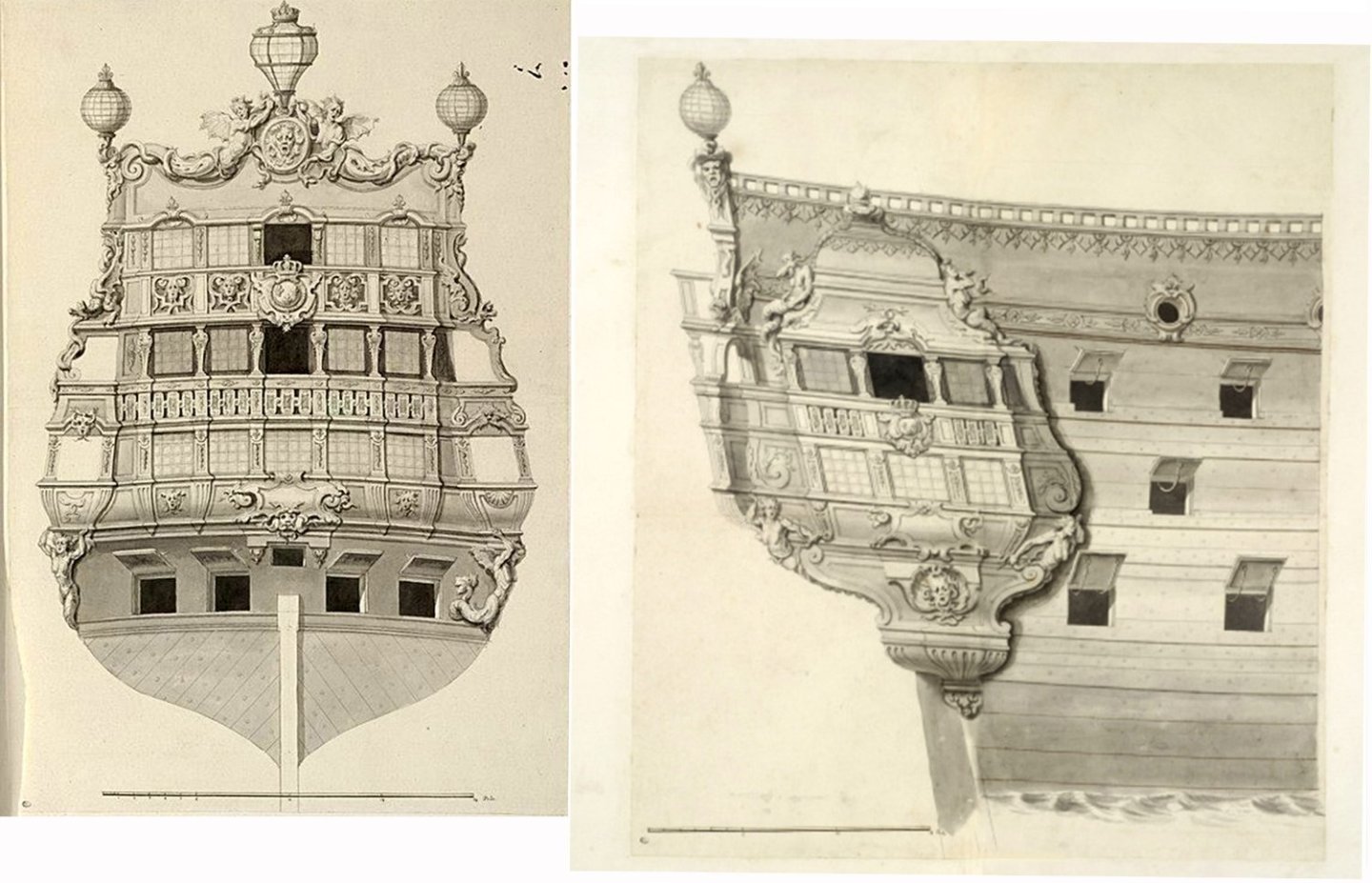

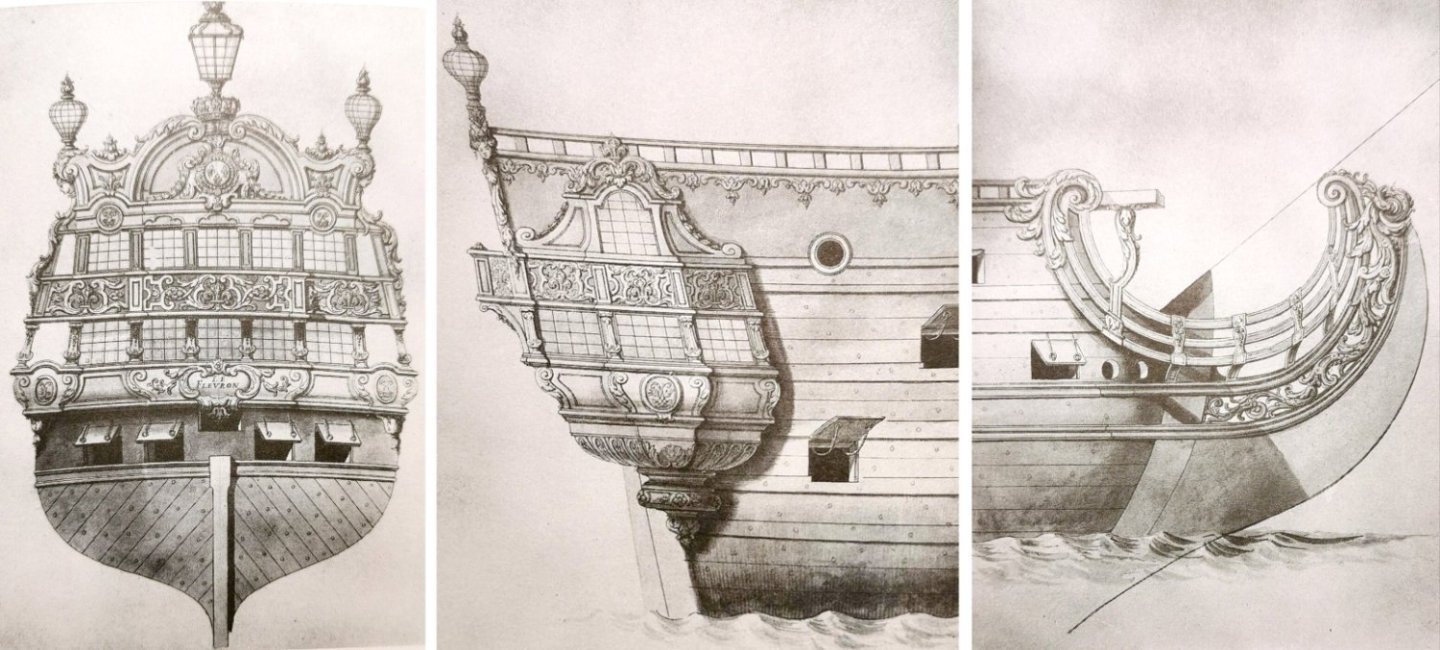

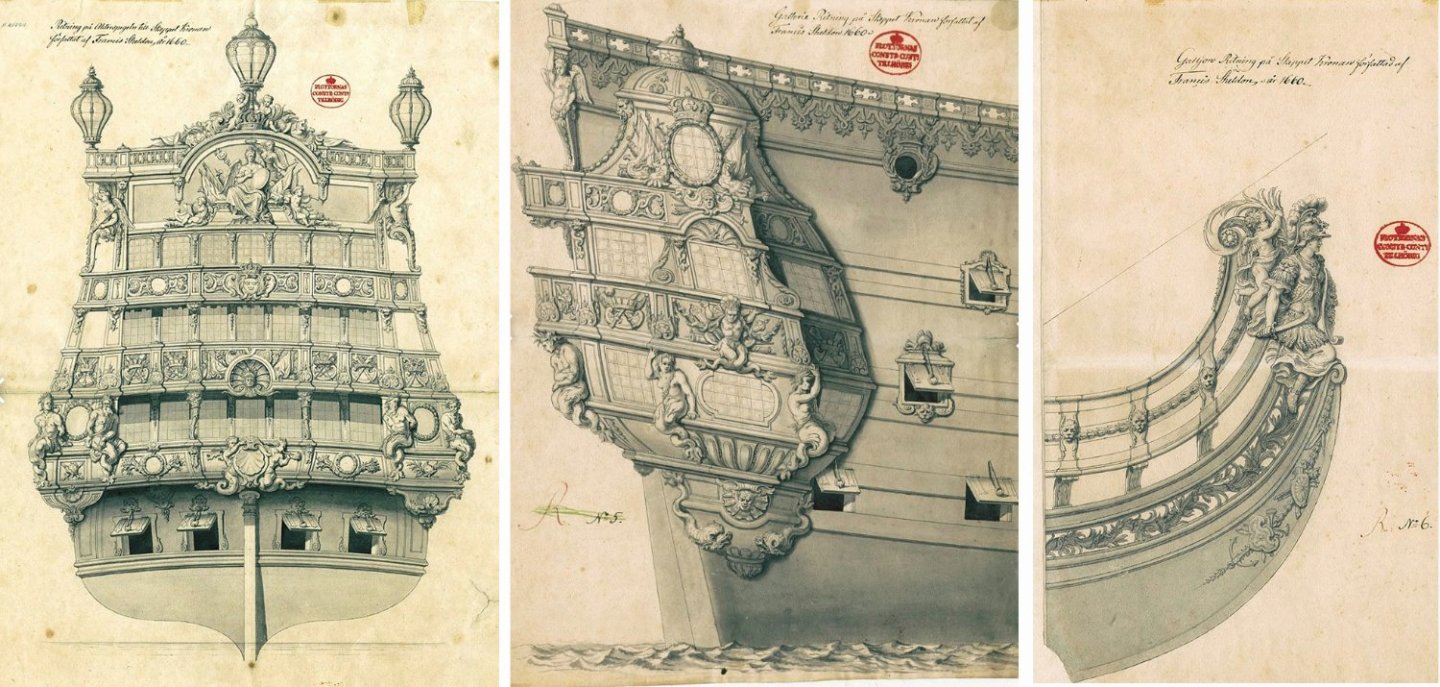

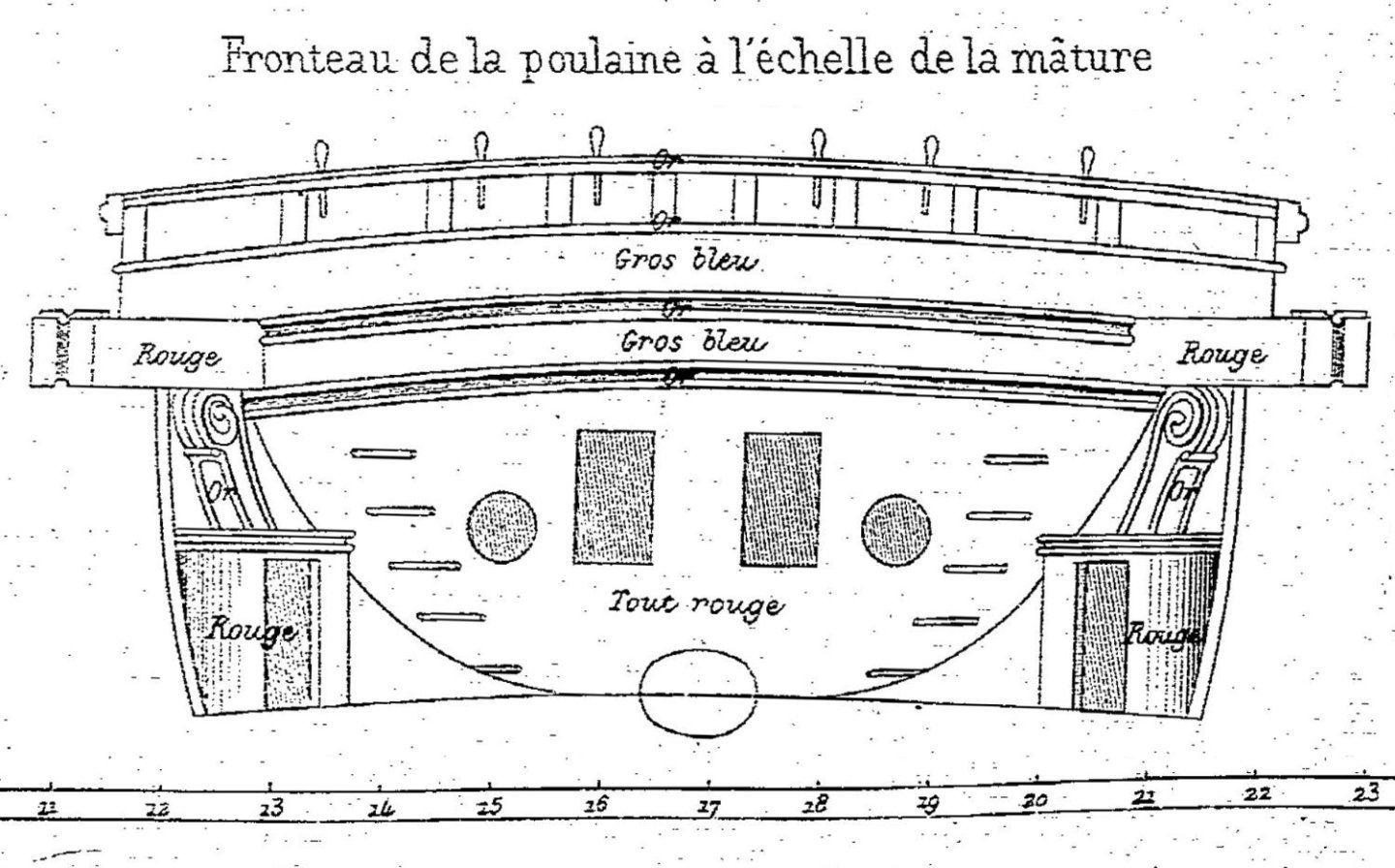

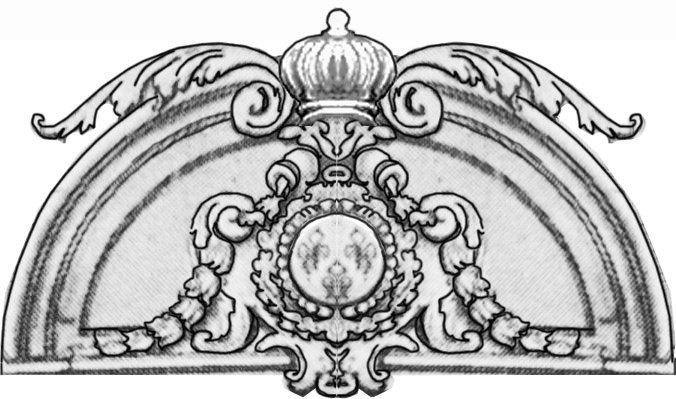

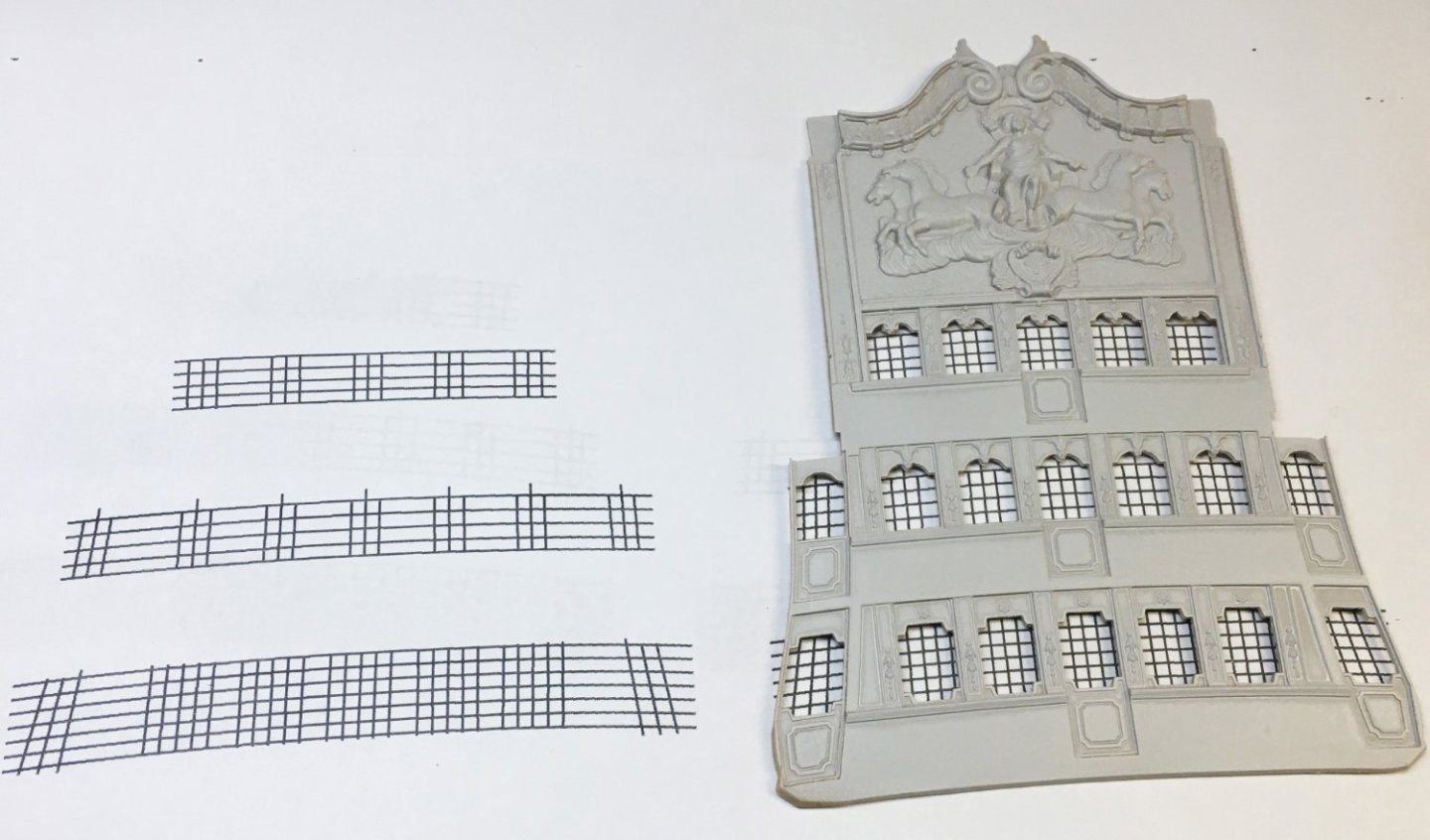

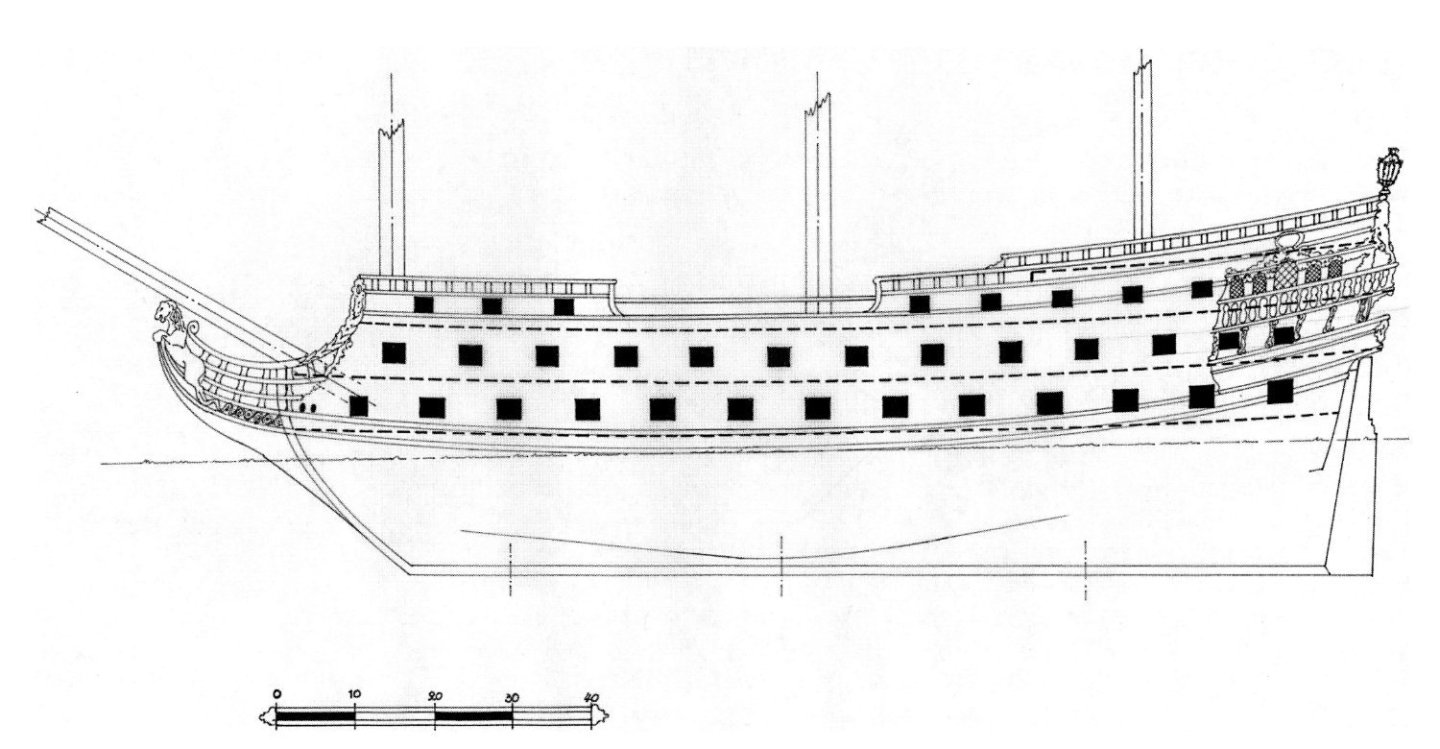

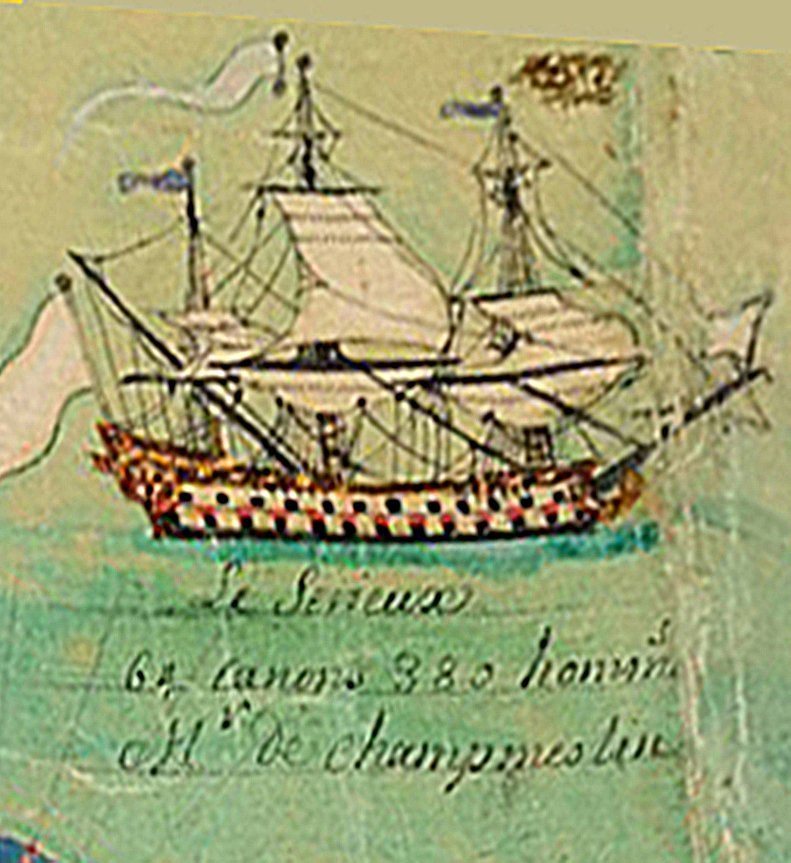

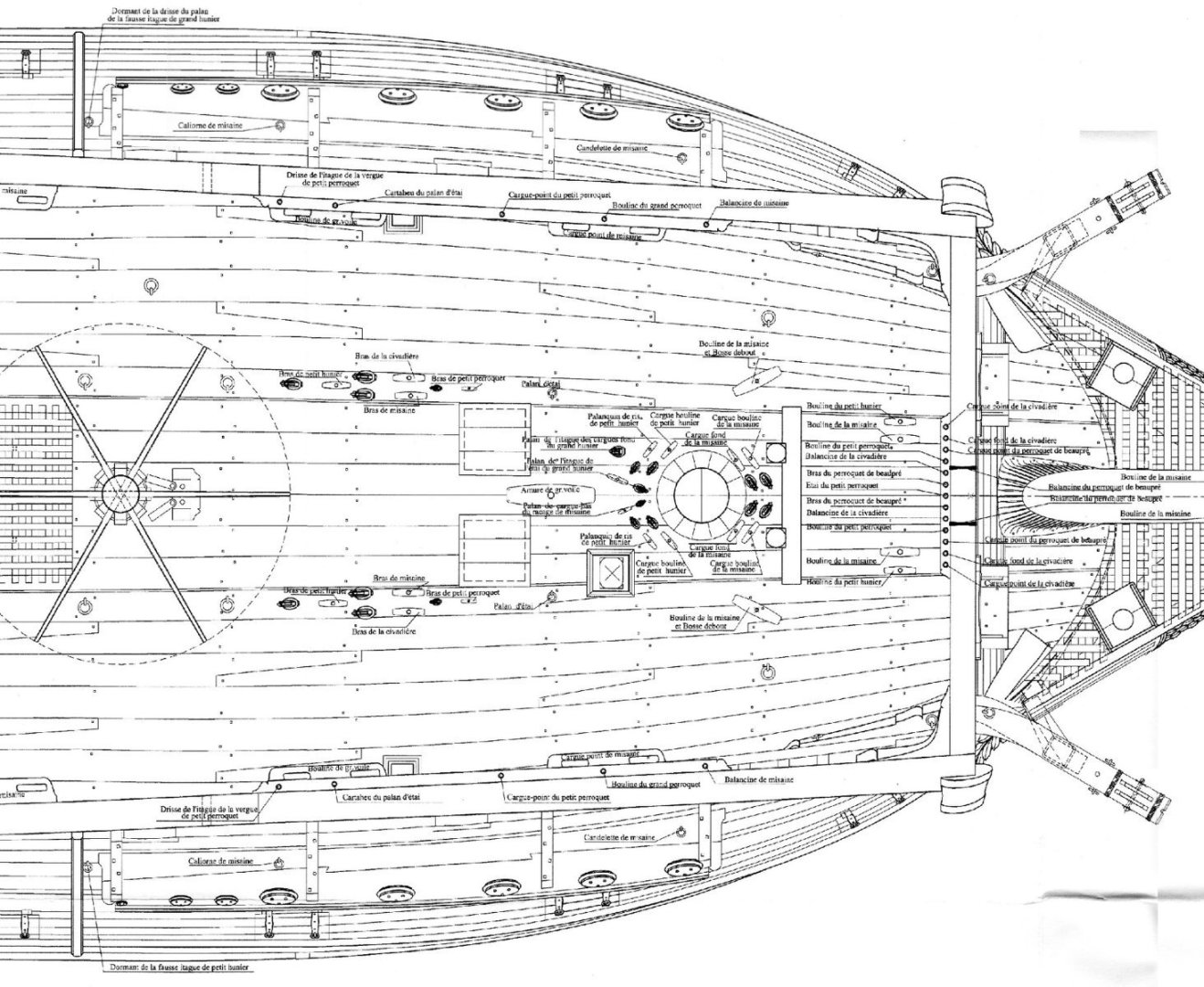

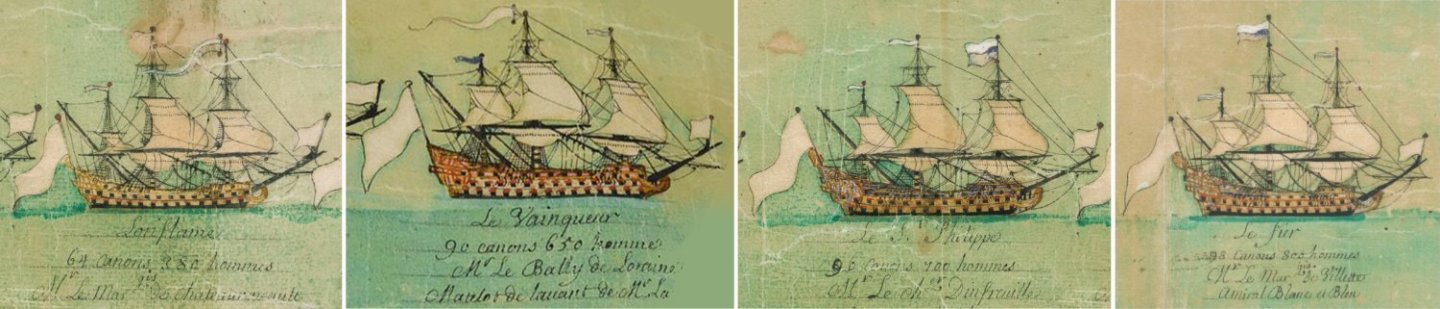

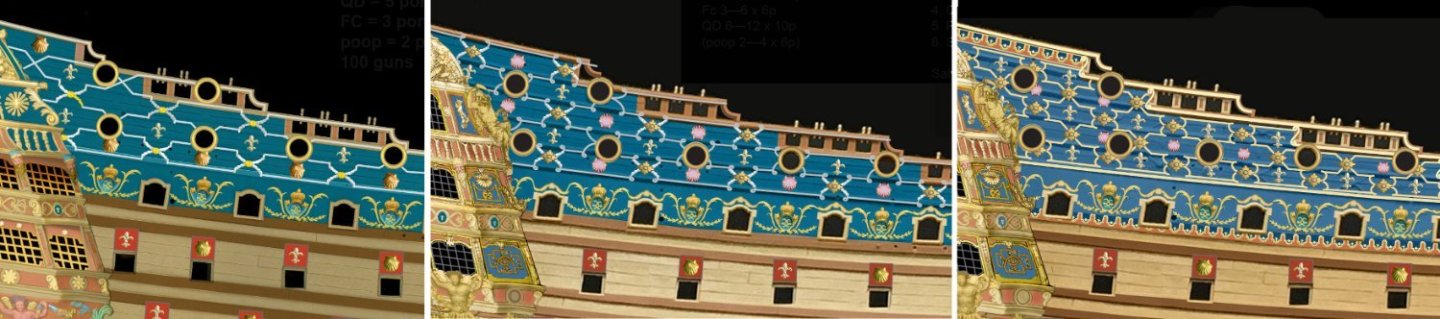

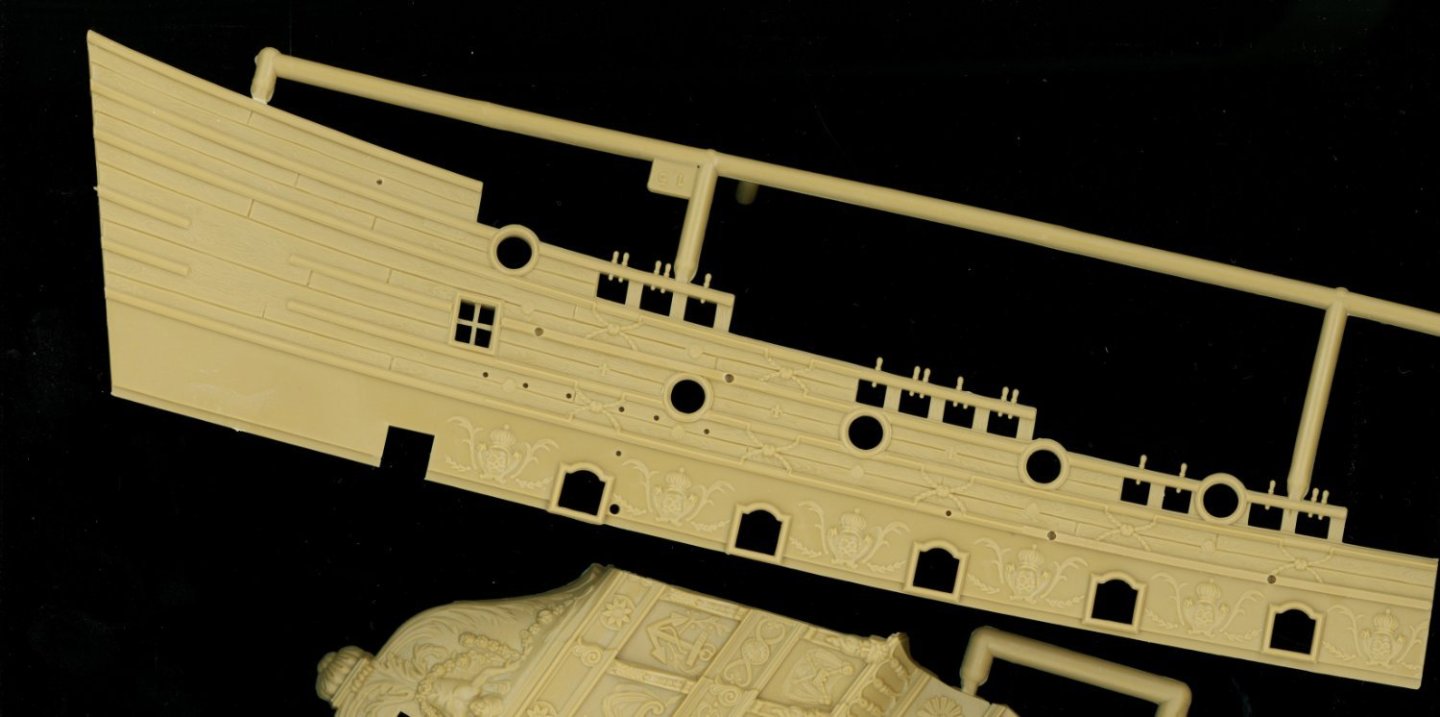

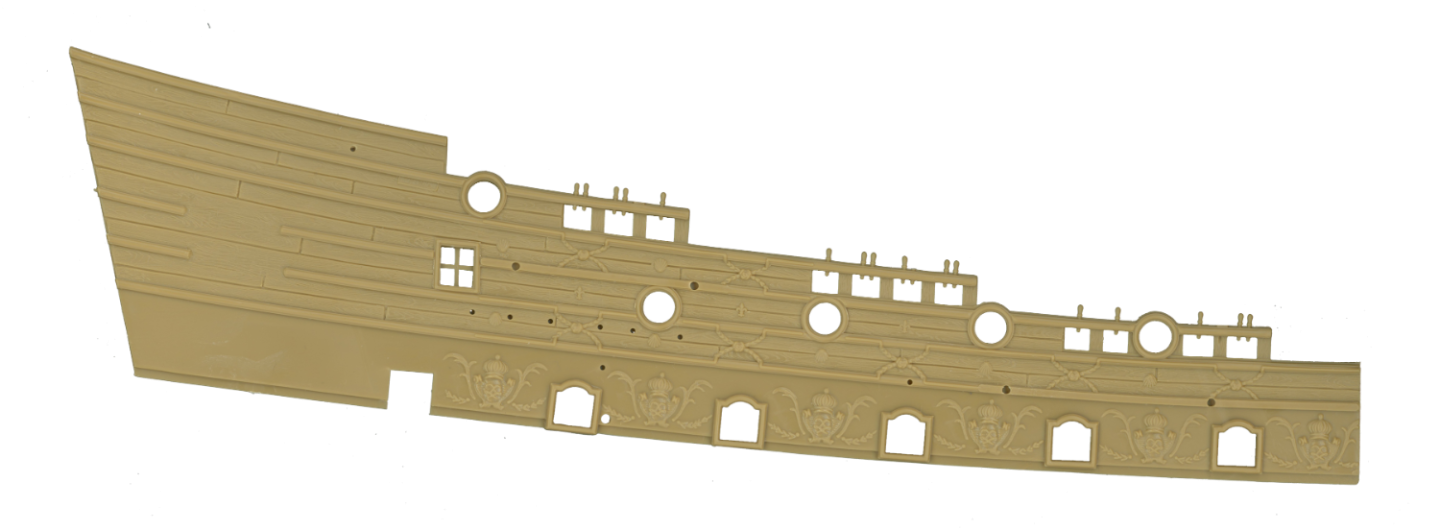

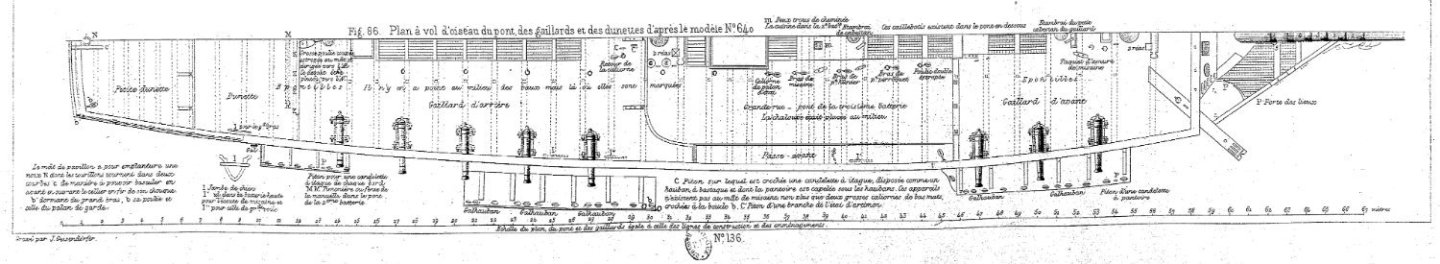

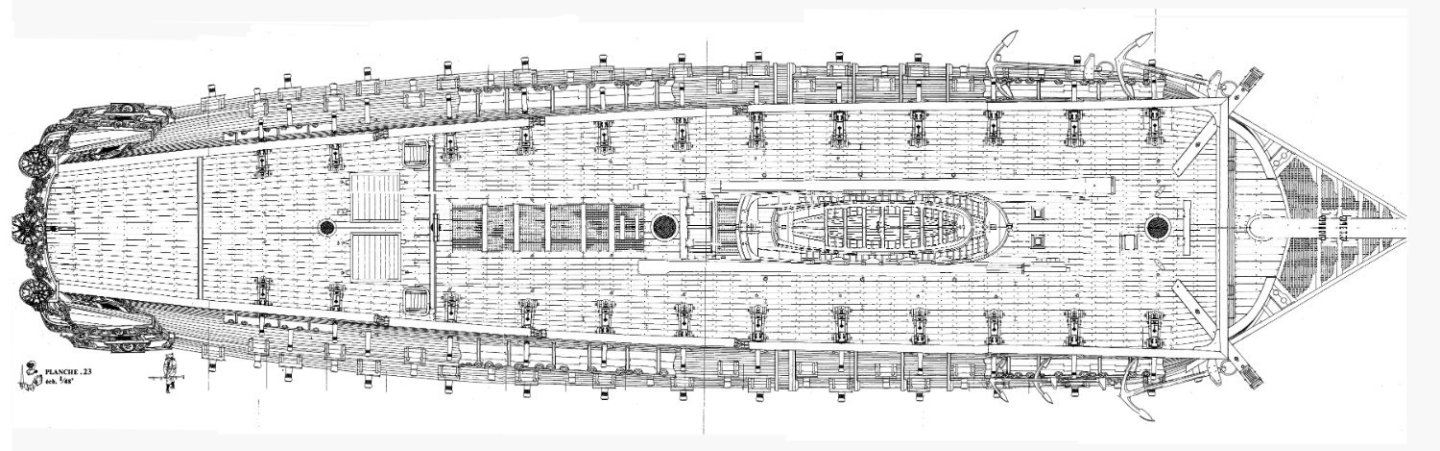

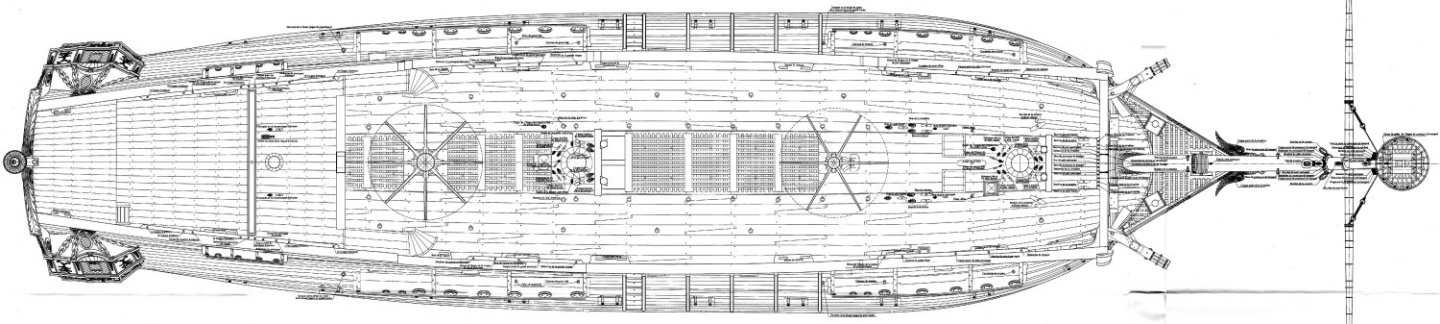

So what do we do with the Heller kit’s quarter galleries? They are kinda problematic, after all. Modelers have had a tough time deciding which version of the Soleil Royal the Tanneron model represents, and some think it’s the first 1669 version because of the open balconies on the quarter galleries. Warships from 1660s had open balconies as a matter of course. Nice . . . but complicating that analysis is the fact that quarter galleries on French warships were often built over the aft-most gunports. In times of war there had to be a way of opening those ports, and the practical solution seemed to be making the quarter gallery panels removable. To back this up, there are pictures of French warships from the 1690s that show open balconies, even though closed quarter galleries had been dictated by the Navy administration back in 1674. So—first version? Maybe so and maybe not. The Tanneron model is pretty obviously not the 1689 rebuilt version, because there are big discrepancies between the model and the Bérain drawings of the rebuild. Others modelers—like me—think Tanneron’s model is the second Soleil Royal, built in 1693, based on the layout of the gunports and the resemblance of the model’s quarter galleries to a drawing from the Library of Cherbourg which is labeled as belonging to the Soleil Royal but is definitely not the Bérain version. Here's the Cherbourg Library drawing. And here are the similarities to Tanneron's model— So where did this drawing come from? When did it come from? Can we tell from context? How do we know it wasn’t from some earlier version of the Soleil Royal? To answer that, we need to go back and look at the development of quarter galleries on French warships over a period of 35 years. The Soleil Royal was one of the first 100+-gun three-deckers built by the French navy. In the 1660s, realizing the need for bigger and better warships, Louis XIV’s ministers attempted to jump-start their shipbuilding program by hiring Dutch-trained shipwrights like Laurent Hubac, builder of the first Soleil Royal, and even by buying Dutch-built ships. Dutch shipbuilding at that time was the most advanced in the western world. Their ships had elaborate decorated sterns, but didn’t have much in the way of quarter galleries. The Courtesan of 1666, below, was one of the Dutch-built French ships. This is the kind of ship design the French emulated. The drawing is by Willem van de Velde. Courtesan Laurent Hubac’s first Brest-built ships had similar abbreviated galleries, like the 1669 la Reine (ex-Royal Duc). It had an enclosed middle-deck gallery (where the officers’ heads were) and an open balcony above it. (These are more drawings from Willem van de Velde . . . .) The first Soleil Royal was built that same year. la Reine Royal Therese, built in Toulon in 1669, shows the same idea. Royal Therese No drawings survive from the first Soleil Royal, but ship historians like Jean-Claude Lemineur were inclined to reconstruct the ship using the same principle. This went on for another five years, including ships like 1671’s le Terrible below, another one of Laurent Hubac’s ships. This shows that Hubac-built ships from both before and after the first Soleil Royal had abbreviated galleries. If I was making a conjectural drawing of the first Soleil Royal, I'd be making notes. le Terrible In 1673, the rather arbitrary decision from Paris was promulgated, advising shipbuilders that henceforth, quarter galleries would be built with all balconies enclosed, like on English ships. At the same time, the stern balconies were supposed to be reduced—in many cases, making the middle deck balcony into a false façade. I’m sure this didn’t settle well with the conservative Dutch-trained shipwrights. Surviving drawings show a lot of halfway measures, like the 1680 rebuild of the 1668 Dauphin Royal, where the upper gundeck balcony was given a little Moorish castle, but the middle gundeck balcony was left open. The next decade more or less corresponded with the arrival of chief decorative designer Jean Bérain, whose plans for sterns and quarter galleries made them look like little multistory Paris palaces or wings of Versailles. Here is le Furieux of 1684, built in Brest, and le Fleuron of 1689, built in Toulon. le Furieux le Fleuron Of course, there’s also Bérain's drawings of the proposed rebuild of Soleil Royal. By the time the second Soleil Royal was built in the early 1690s, the dormers of Bérain’s quarter galleries had taken on a definite dome shape, like on the Saint Philippe of 1693 and the Swedish Konung Karl of 1694. Notice that the Konung Karl sports twin-tailed mermen on the balconies very similar to those in the Cherbourg Library drawing of the Soleil Royal. Interestingly, it looks like all the stern balconies had depth, just like ones in the Cherbourg drawing. In that and other details, I would judge the Konung Karl quarter galleries closest in style to the ones from the Cherbourg Library. le Saint Philippe Konung Karl The Soleil Royal II was built in 1692–1693, one year before the Konung Karl. In other words, the KK drawing was probably made during the time the SRII was under construction. So—back to the Tanneron model. Yes, the model’s quarter galleries have open balconies, like the early French three-deckers. The problem is that it has too many balconies, plus upper works—dormers, domes, panels, and false lights— that just weren’t a thing on 1669 French warships. From the design and the detailing, the closest stylistic matches we have are the 1690s Bérain designs. I think the Cherbourg drawing came from a 1690s ship and so, by deduction, from the Soleil Royal II. This, I think, was the prototype for the Tanneron model. At the start of this post, I outlined the differences between the Tanneron quarter galleries (copied by Heller) and the Cherbourg drawing. I really wanted to redo the galleries to closer match the drawing. This didn’t sound radical at first. Lots of Soleil Royal modelers open up their QGs by carving away the relief panels which seem to have no relation to anything on real French warships. While doing the necessary styrene surgery, I planned on fiddling with the proportions a little—maybe give the QGs new, more accurate dormers. I had already extended the stern by 3/16”, intending to expose two of the three gunports incorporated into the QGs. I made some Photoshop sketches, showing my choices for opening up balconies. I decided to leave the upper gundeck gallery open, like in the second photo. That would give some added interest to the QGs and still give the 1/100 officers some privacy when they visited their heads. First, I had to finish the stern balconies and glue on the stern plate. I noticed that the balconies stuck out too far—four feet. I trimmed them back to 3 feet, similar to the surviving drawing. Had to trim the knees, too. The middle deck balcony was supposed to be a false balcony anyway, so it got trimmed the most—it’s only 2-1/2 feet wide. Oh—and I hated the sunflowers on the middle deck balcony. I checked—and yeah, they were considered official symbols of le Roi Soleil—but I had never seen sunflowers on any drawing of a French warship. On Bérain’s drawings, they were supposed to be cartouches (architectural oval frames), sometimes with Louis’s monogram, sometimes empty. Stern lights were affixed with Testors’ canopy glue. I thought the white cames (lead between the panes) looked cool. Time to take a deep breath and glue on the stern. Now for the quarter galleries. With razor saw and x-acto knives, I carved up the kit’s quarter galleries. Having embarked on an orgy of destruction, I never paused to take photos. Everything usable was trimmed out and set aside—besides the balconies and columns, that included all the figures, faces, and foliage. Then I could start Frankensteining everything back together again. I decided to keep the "drop" from the bottom of the galleries. It hid the waste chute, after all, but I trimmed it and repositioned it to keep it out of the way of the lower gundeck's furthest aft cannon. An important feature of the middle gundeck balcony was the mermen. Tanneron had placed them below the balcony and turned them into winged, garland-draped fairy figures. I wanted to put them back on the balcony where the drawing said they belonged, and also return them to being split-tailed tritons. For a first try, I attempted to repurpose the fairy figures from the kit, giving them fish-tails instead of garlands, and new bearded faces taken from the QG's quarterdeck level. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that the figures were about 50% too large to fit comfortably on the balcony. This was a genuine moment of frustration. What to do? Carve new figures from scratch? Too bad I’m terrible at it. I have never felt competent making 3-dimensional sculpture. Should I check to see if the kit had any other figures I could use to make castings? Sure—but the answer was nope. Anything around my hobby desk? The house? Nope and nope. Go to the hobby store and see what I can scrounge for new figures? That sounded like a plan. Drink beer afterward? Even better. So a trip to the hobby store led me to a set of 1/72 Nexus plastic figures labeled “Ancient Life.” Are they supposed to be used for games? I don’t know. I don’t care. Looked promising. The set contained a number of bare-chested males with arms spread. Perfect. I cut them off at the waist, added fishtails and beards carved from scrap styrene, and I had my two split-tailed tritons. Excelsior. I glued on the first four balconies. Paper templates told me where the columns were going to go and what size the panels and false lights needed to be. I was making progress—or so I thought. But the columns and panels weren’t lining up with anything. There should have been some vertical elements on the balconies that met the columns. Plus, the sunflowers were bugging me again. Before too long, I called a halt and went to find another beer. Then I ripped away the new balconies plus the stern middle deck balcony, and started over again. This time I built the balconies from scratch using Evergreen sheet and strip styrene. This time, the balconies and panels had their connecting vertical elements. All the sunflowers got deep-sixed in favor of blank cartouches. Happier? Yeah. For the quarterdeck balcony, I had made a lot of little castings of the diaper-pattern balusters from the stern with mold putty and 5-minute epoxy. I cut them apart and assembled them with more strip styrene into railings. The false dormers and lights above the railings were made with more sheet and strip styrene. It took me a while to stare at the Cherbourg drawing and figure out what was painted on the side panels of the dormer—swords and olive branches. War and peace. All righty then. I painted on the foliage and cut the swords from scrap strip styrene. Tanneron’s (and Heller’s) QG domes had the same elements as the ones in the Cherbourg drawing, but Tanneron carved them in a way that I don’t think would have been acceptable in Louis XIV’s time. The king’s beaming face was small and secondary compared to the giant cornucopias Tanneron carved surrounding it. One thing Baroque art teaches you—the king is never to be shown as being of lesser importance. That feature needed to be fixed. The new domes with the smaller cornucopias and the Sun King’s large radiant countenance were made with sheet styrene decorated with small sections salvaged from the kit’s QGs. The showers of fruit and foliage coming from the cornucopias were cut and shaped from the originals. The domes' lanterntops are two stacked bead caps from the local craft store. Since all this involved Louis’s smiling autocratic face, I gave the domes a coat of Vallejo 70.996 gold. As planned, the golden dormer-tops perfectly complimented the gilded Apollo frieze on the stern. Longue vie au Roi. I was pretty much done with the stern and quarter galleries, but there were still other details and figures to add. Does anyone really want to hear about how I tore off and rebuilt the lower quarter galleries a third time? I thought not . . . . Next time, I'll discuss the figures in detail, and French ship carvings in general. And you'll see the discourse on deck furniture and belaying plans that I had promised, but didn’t get to today. Stay out of trouble 'till then. Remember, if it isn't Baroque, don't try to fix it.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

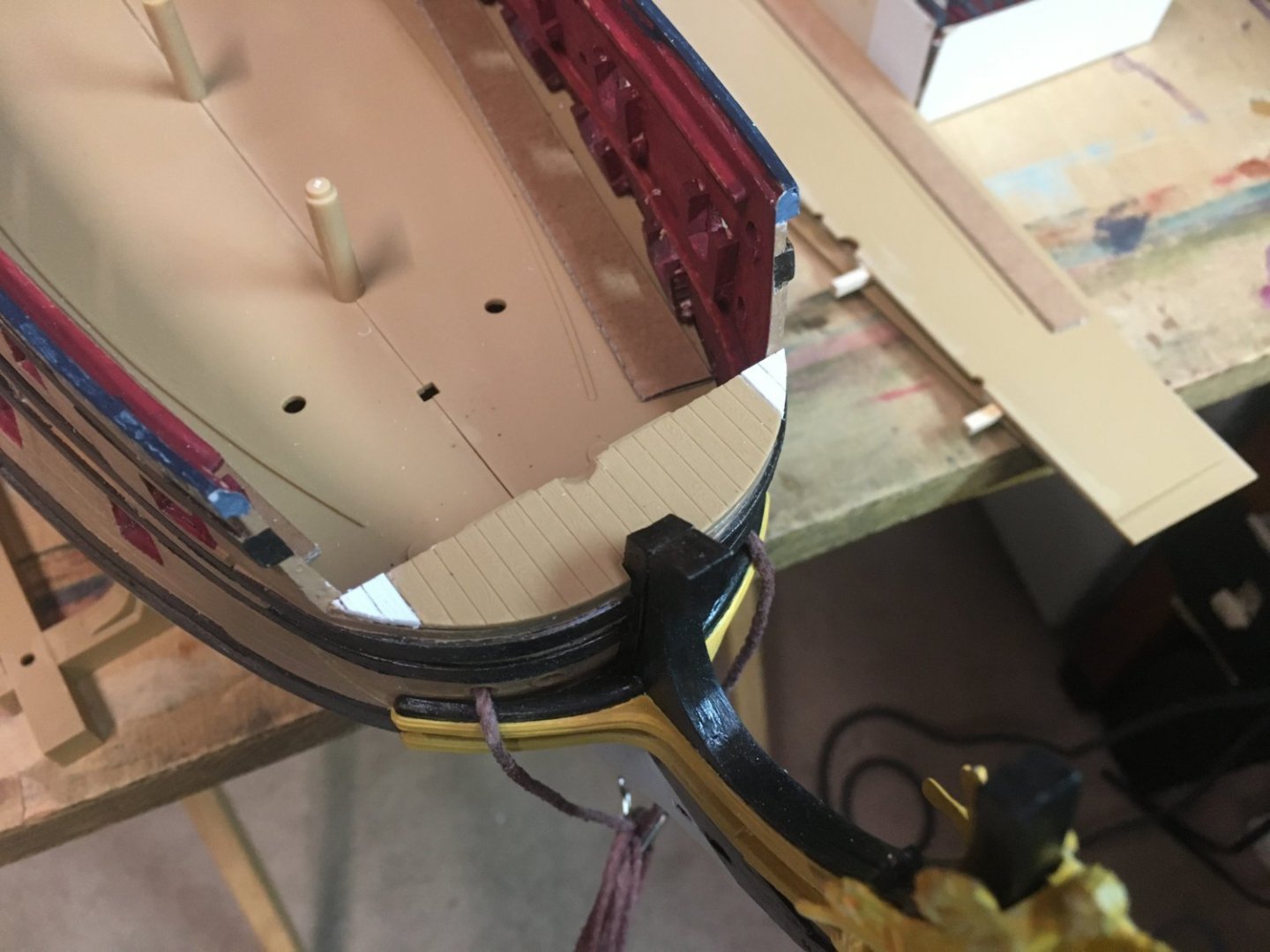

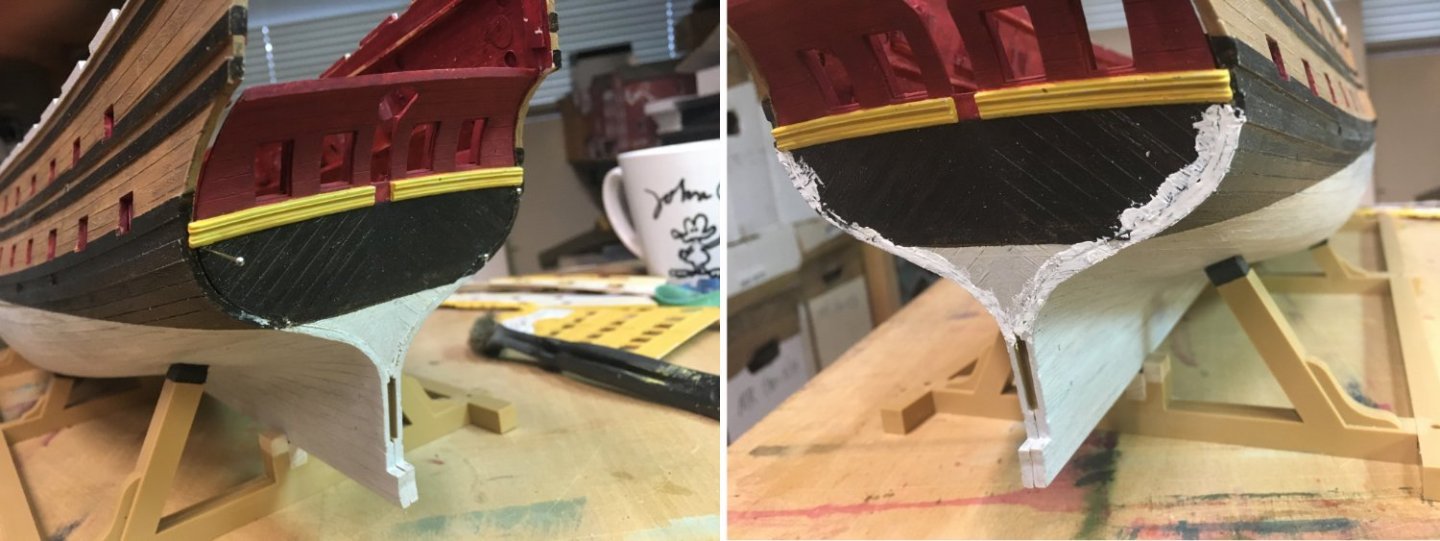

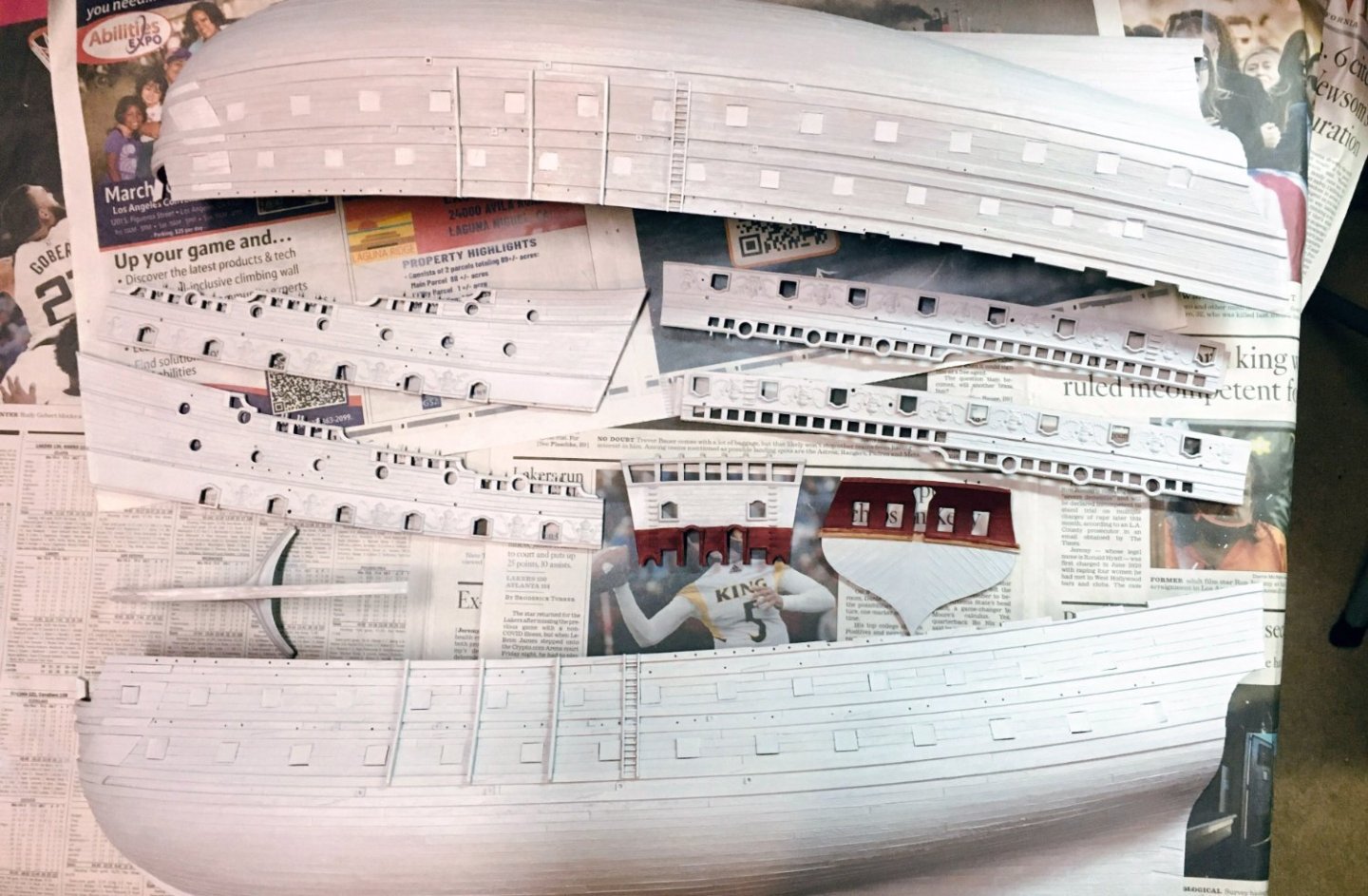

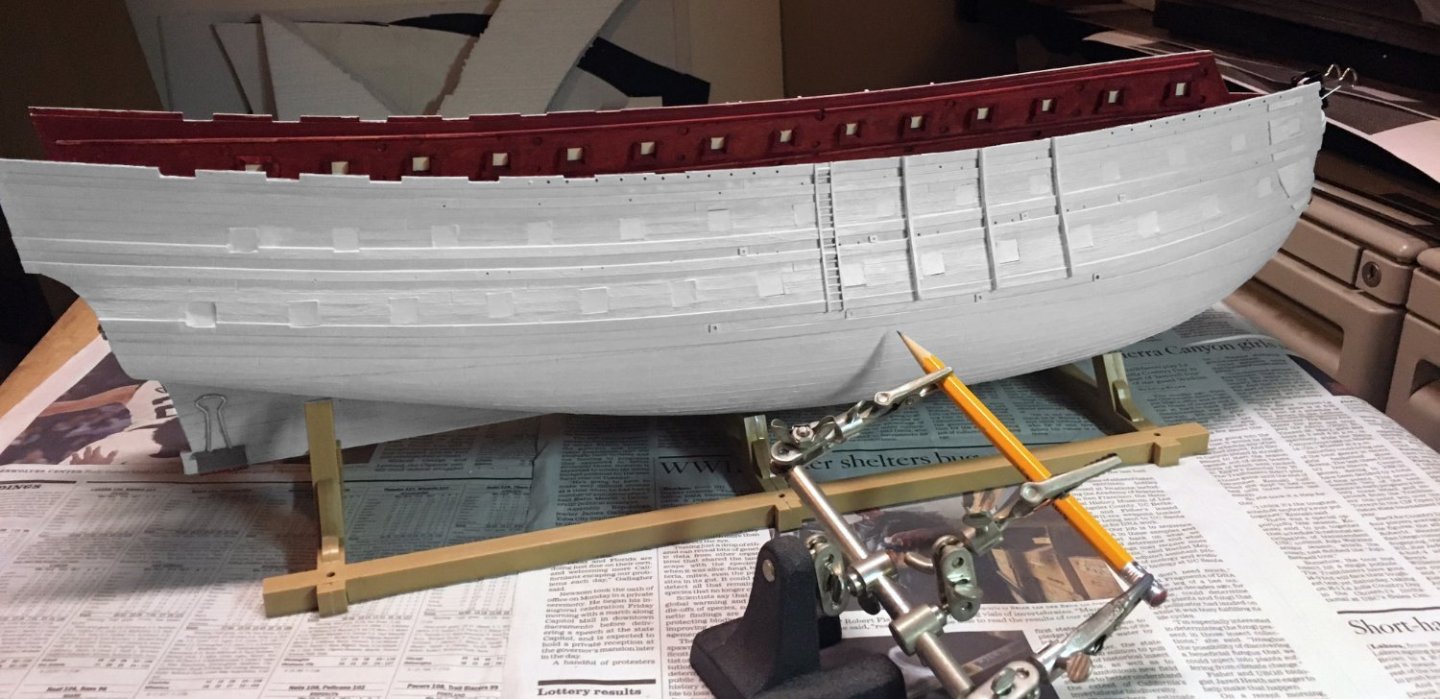

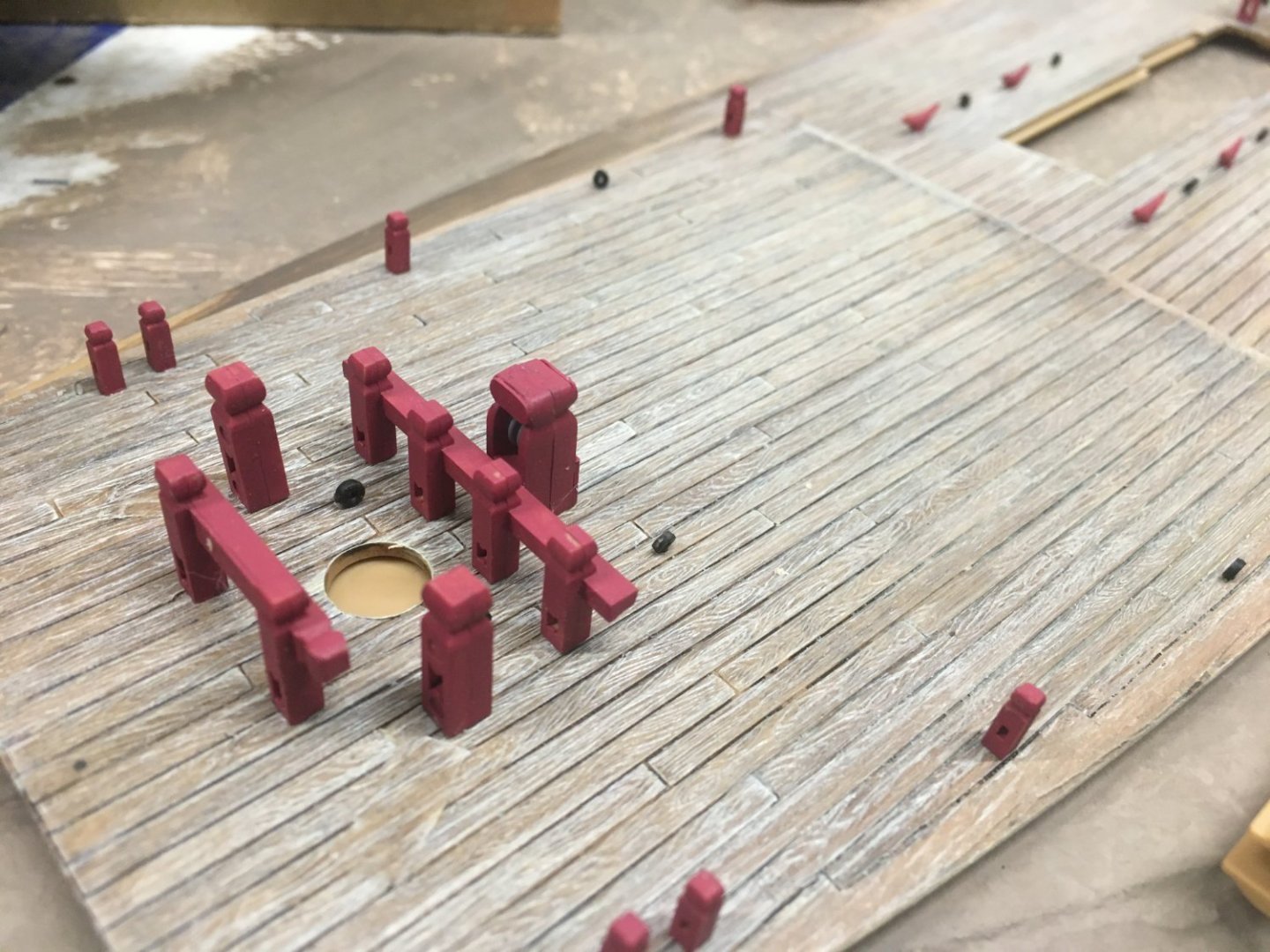

Welcome back. Here's my little tub recently, about half-done, and waiting on me to get a passing grade in rigging 101, as taught by M'sieurs Anderson, Marquardt, et Boudroit, so we can continue the build. Setting the "D–" in rigging class aside, getting to this point was fun and what I'll be blathering about today. At the end of about three months' work, I was finally ready to put some glue to parts and start assembling the hull. Sides and decks were painted. I had the guns ready for mounting. With binder clips, I could put it all together to see how everything fit. But I still had to make some improvements to the bow and stern—the subject for today. So where to start with the bow? One obvious thing is to remove the s—. . . ahem, roundhouses. Nobody except maybe officers could expect privacy on a 17th-century warship (their facilities were in the enclosed quarter galleries). Roundhouses weren’t even introduced until the early 18th-century. This was a period-inappropriate goof made by Tanneron on his model and copied by Heller. It was time for surgery. The roundhouse bases were sliced off the beak deck and replaced by strip styrene. The insets for the roundhouses on the front of the forecastle were likewise patched. Next problem, the front of the forecastle was too plain for my taste. I had a drawing of the 1693 Royal Louis that gave me a clue where to start—blue above; red below. It made sense to me to continue the colors and patterns from the hull sides around the front, so I made decals that matched. I ended up painting over most of them, but you'll see that evolution presently. I had read that the royal ships mounted the king’s arms on the bows. I used mold putty and epoxy resin to copy the royal emblem from the stern. I added a crown—a little brass jewelry stamping from Etsy—because that was how royal arms were always supposed to be displayed. (On the stern, the crown is above the frieze, under the center lantern.) I was sort of okay with this until I got a look at the forecastle on Marc La Guardia’s beautiful ship. Then I wasn’t okay. I was jealous. (It has happened more than once!) I went back and studied every old painting and drawing I could find, looking for a fancier treatment of the royal emblem. I came to realize the king’s arms got special artistic consideration wherever they appeared. They were usually isolated from the other design elements by some sort of containment— a box, a shape, a frame— that indicated how exaltedly separate the king was from everything mundane. He didn’t mix with the hoi polloi. In the Bérain drawing of the Soleil Royal’s stern, the king’s arms were isolated by a lunette. I decided to make a similar complimentary lunette for the prow. Eventually, I settled on copying a lunette from a drawing of another ship, Le Fleuron. The lunette was made from scrap styrene, plus the earlier resin casting and a pair of brass stampings I found on the Etsy website. This was beginning to look better. (Thank you, Marc, for the inspiration!) I continued the planking and wales from the ship’s sides around the front, because that seemed to be a neat thing on certain antique ship models. The beakhead slats were turned into gratings by adding thin styrene strips. It just seemed more logical, if anyone was expected to walk there on a rolling ship without turning an ankle. Eventually, I added a pair of “seats of ease” to the head. They probably should have both been two-holers, but I never could figure out how even four seats could have serviced a crew of 900. I’m sure there were other… avenues of relief. Moving on. Heller’s knee of the head has a lot of odd detail—like the holes for the bowsprit gammoning placed parallel to the waterline, and all those mold lines indicating separate pieces of wood. I saw some modern reconstructions, like Jean Boudroit’s drawings of L'Ambitieux, that show something similar, but other descriptions say the knee was made from just a few large pieces. I decided to just de-emphasize everything. I took the white putty, sanding sticks, and drill bits to the pieces and did some revisioning. When it came time to glue the knee to the hull, there was significant gapping—but nothing a little tapered strip styrene and white putty couldn’t handle. The ship’s figurehead was beautiful, but a mold flaw deprived the fairy sea nymph (or whatever she was) of her port wing. I carved another from sheet styrene. Instead of gold leaf, it looked to me like most ship’s statuary from the Baroque was faux gold—different shades of yellow ochre, with bright lead-tin yellow for highlights and browns or oranges to deepen shadows. Sometimes the formula included a coat of Burgundy pitch (spruce resin) with powdered copper or brass. There are some examples of faux gold nautical statuary in French museums. I used them as color models when I painted the figurehead. This worked out well and I now knew what to do when I got to the figures on the stern. The colors I used were the same mix of Vallejos and generics I had on hand—Vallejo 70.948 golden yellow, 70.858 ice yellow, 70.911 light orange, and a generic craft acrylic, "antique gold" which was a perfect yellow ochre. I couldn’t glue on the headrails until the bowsprit was installed and gammoned, but I could paint them. Here’s another example of special treatment for royal symbols—I decided the face of the Sun King surrounded by the sun’s rays was worthy of gold leaf. It and the royal arms are practically the only gilded parts on the bow and beakhead. I ended up gammoning the bowsprit twice—once, after mis-reading a measurement and using too light a rope. I cut it away to do the job over with the proper diameter rope. I followed the description and diagrams in Anderson’s The Rigging of Ships in the days of the Spritsail Topmast 1600–1720. Once the gammoning was on, I could fit the headrail braces, made from more Evergreen sheet and strip styrene. The oddball geometry of the beak and headrails defied making accurate measurements, so it took forever to cut cardstock templates, fit, cut again, fit, trim, fit—then do the same repeatedly with the Evergreen plastic—cut, fit, trim, fit—start again—cut, fit . . . . Forward to the stern. I decided to paint the lower stern red for a couple of reasons—first, it matched the red on the lower part of the forecastle. Second, I was inspired by this 1834 painting of the Foudroyant by Auguste Étienne François Mayer. Which seemed to perfectly capture the “look” of a Baroque French warship I was trying for. The lower stern piece didn’t quite fit the hull halves without a lot of coaxing with clamps and rubber bands. I didn’t want glue joints giving way at some later date, so I opted for a more metal solution. I drilled for pins to hold the lower part of the stern-piece in place. Then, after the glue was dry, the heads of the pins were clipped off. White putty improved the joints. The upper part was fixed by pulling the hull pieces together into a tight fit and installing a brass strip attached with screw-headed bolts and nuts. The bolt-heads would be invisible inside the quarter galleries. Since I had extended the stern 3/16”, the middle gundeck got an matching extension with a lip to hold the stern plate. The stern plate wouldn’t get glued on until I had finished the balconies and was ready to do the quarter galleries. In the meantime, I made sure the piece fit the new stern extension perfectly. I thought the rear gunports were oddly proportioned—a little too tall—so they were cut down in size by the addition of some decorative framing. The cut-down doors were decorated with the king's monogram (more decals). It was here I decided that the gunport doors throughout the ship were going to be held open by blackened wire—not thread. I disliked the way thread looked when it was slack, and I never found a way to make both sides taut at the same time. The stern lights on the Heller model are supposed to be leaded windows. But instead of thin cames (the proper name for the lead strips between panes), the kit windows have fat three-inch mullions. Kind of typical for a small-scale plastic model, but not optimal. I decided to give them another try. First, I put the stern on my scanner and made a to-scale digital image of it. Then I chopped out the thick mullions— On my laptop, I used the scan of the stern plate as a template to draw new lead cames in Adobe Illustrator. When the time came to assemble the stern, I printed the cames on a sheet of laser printer transparency film. After seeing how the dark cames disappeared against the dark windows, I decided to use the printout as a template and make the cames with thin white chart tape on clear styrene. It made them fatter again, but they still looked better than the plastic mullions. An important but missing element on the stern plate was the lunette that separated and highlighted the king’s arms. This was very evident on the Bérain drawing of the stern. The crest was too important an element to be simply built into the frieze. So, after scribing a guideline with a circle template, I got out more sheet and strip styrene. This element was important to Baroque thinking. As mentioned before, the king’s emblems were almost sacred, and they were almost always isolated and given priority over all other visual elements. The king’s arms here would later get painted with expensive ultramarine blue and gold leafed. The stern plate was given two shades of yellow— yellow ochre (generic “antique gold” craft acrylic) for the lower “background” surfaces and Vallejo 70.948 golden yellow for the higher “foreground” features like frames and decorations. Where blue was needed, I used the same old 70.943 grey blue to match blue verditer paint. The king’s Apollo-in-his-sun-chariot frieze was designed by Charles Le Brun after Le Brun’s similar Apollo fountain in the gardens of Versailles. The fountain statuary had been originally covered in gold leaf (I understand it has recently been restored to gold leaf again). That fit right in with my notion that the only major parts of the ship that were genuinely gilded had to do with the king himself. Back when I was making Photoshop mock-ups, I had planned to gild the Apollo frieze and the Sun King's face on the top of the quarter galleries. I made a few minor changes to the paint scheme on the fly—using the lighter blue on the Apollo frieze and giving it a white frame instead of more gilding. The frieze was painted white. After it dried, I carefully masked to separate the white frame from the frieze’s blue background. The gold followed the blue. I had brand-new fine-tip sable detail brushes, so I hand-painted the whole thing. Apollo-Louis and his steeds got painted Vallejo 70.996 gold with 69.060 old gold on the undersides for shading. Feathered it so there wasn't a hard transition. Gold was also used for the zodiac frieze above and the chains of bellflowers between the lights. The insides of the upper gundeck and quarterdeck balconies got some of the leftover decals, continuing the patterns from the sides around the stern. I later painted the insides of the false balcony on the middle gun deck red, like an interior bulkhead. The lights got their white-chart-tape cames, sealed onto the clear styrene by a coat of Testor’s canopy glue. I would finish the stern balconies later, in concert with the quarter galleries. The model **finally** got glued together. By this time, I had been working on the ship for three months. In the photos below, you can see the mostly-hidden lower and middle deck guns sitting on their simplified carriages glued to cardboard strips. In theory, the cardboard was supposed to provide a little "give" and prevent guns from breaking loose every time they were bumped. I didn’t want any light-colored plastic decks visible through hatchways, hence the big blob of brown paint on the middle gundeck. Around the second time I accidentally knocked a gun barrel loose, I realized my cardboard-strip scheme wasn't doing its job. Some added protection was needed. I made a clamshell box out of 3/16” foam-core, masking tape, push-pins, and string. Same width as the model's cradle. Undo the string and the sides fall away flat. The model wears its boxy cuirass to this day and it’s one of the most useful ideas I’ve ever had. Haven’t knocked a gun loose with my big clumsy hands since. I can carry the ship without disturbing anything on it. This is handy since the model has outgrown my workbench and has to sit beside me on a TV tray while I prepare parts for it. When not being worked on, the model gets boxed up and set on a two-foot shelf that will someday be an extension of my . . . (pardon the expression) . . . ahem, model railroad. As the build progresses, I’ve cut away portions of the box to expose parts of the ship I didn’t want the foam-core rubbing against. Before I could install the upper decks, I had to figure out a rigging plan so I could finalize the deck furniture. Then I needed to make quarter galleries. This will all be discussed next time, along with a little history of the development of French quarter galleries. Until then, Honneur, patrie, valeur, discipline—and 5-minute epoxy. That should cover it.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Daniel. The knowledge I have comes from from sources like Winfield & Roberts' French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626–1786 and Jean-Claude Lemineur's The Sun King's Vessels. The latter book is a focused monograph on the development of French three-decker warships. That and all the other sources I've read say that the SRII was built as intended, a 100+-gun three-decker, originally meant to be named Foudroyant. It wasn't modified from a smaller warship. It was already completed and ready for decoration at the time the issue of renaming came up. That being said, it's entirely possible the ship sat lower in the water than intended. Ship design science wasn't great before the age of slide rules. Nobody really knew the displacement of a ship before it was launched. All that had to be adjusted by adding or removing guns, ballast, etc. However, it's hard to escape the fact that Tanneron used a lot of exaggeration with the proportions of his model. Even if we ignore the shallow draft, which isn't close to the 24 feet mentioned in surviving records, there's the issue that Tanneron built his model with eight feet between gun decks. There's just no way any shipbuilder back then would have done that. I think the best suggestion is that Tanneron exaggerated the proportions to give more emphasis to all the remarkable miniature carvings he made for the stern of the model. Good enough reasoning for me.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks, Kirill, for your observations. You are right, I tend to use "found" materials (like the common string I used for breech ropes) on models simply because I'm not very experienced at building large ship models and I'm having to learn as I go where to get correct-to-scale materials. Or learn if they even exist. Yes, I know the gun rigging blocks are large, but I didn't find 2mm blocks until after these guns were already rigged. My six-pounders with the smaller blocks look better. I think I'd have to dismantle the ship if I wanted to re-rig the guns and replace the larger blocks. The project is probably too far along to do that. At some point, I have to live with my mistakes. "Learning experiences." Considering that the model is going to live in a plexiglas case and be viewed mostly from a few feet away, I don't mind that the detailing doesn't match contest-model standards. That was never the intention. But it is nice to learn what's possible, so I can do a better job next time. Thanks again! John

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

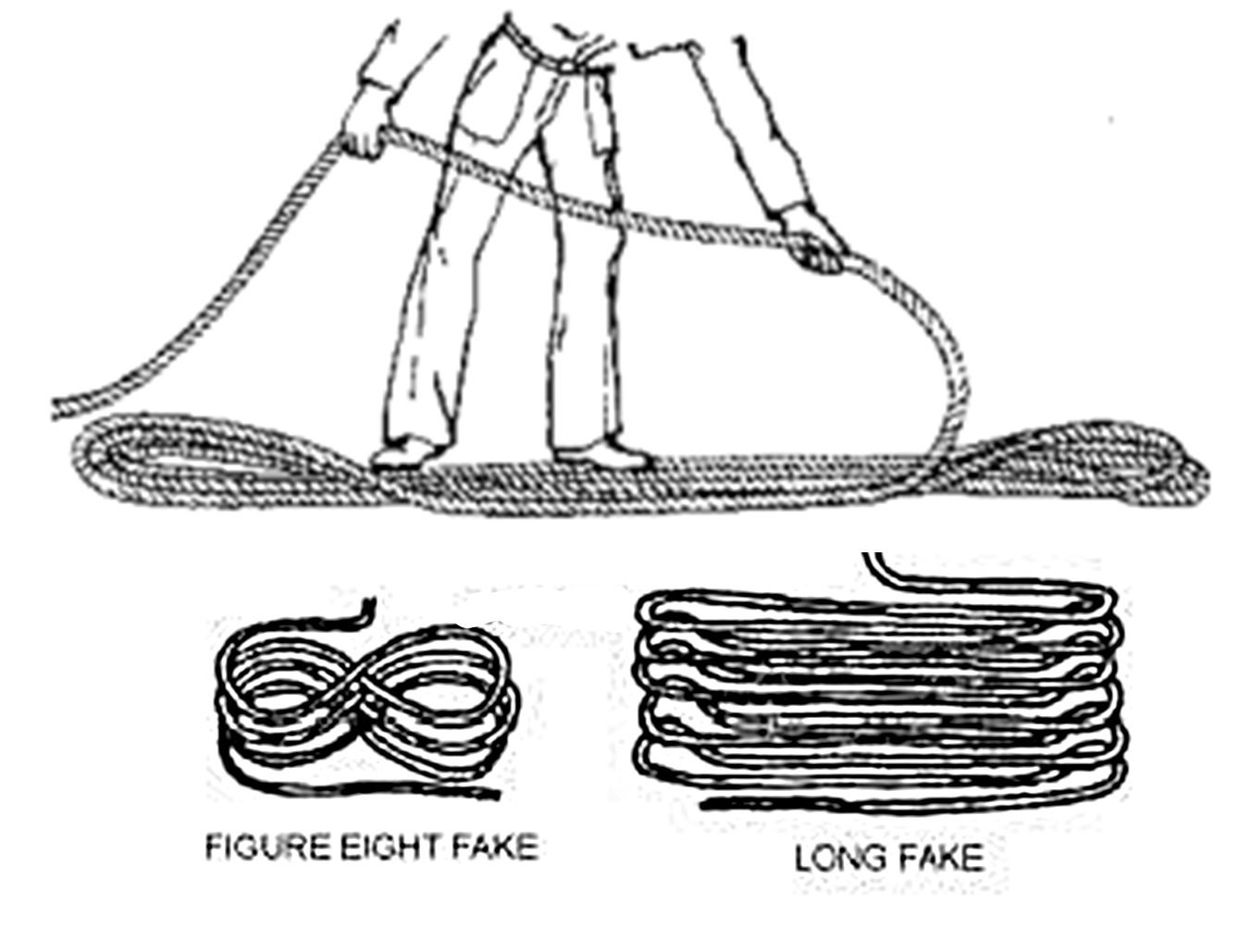

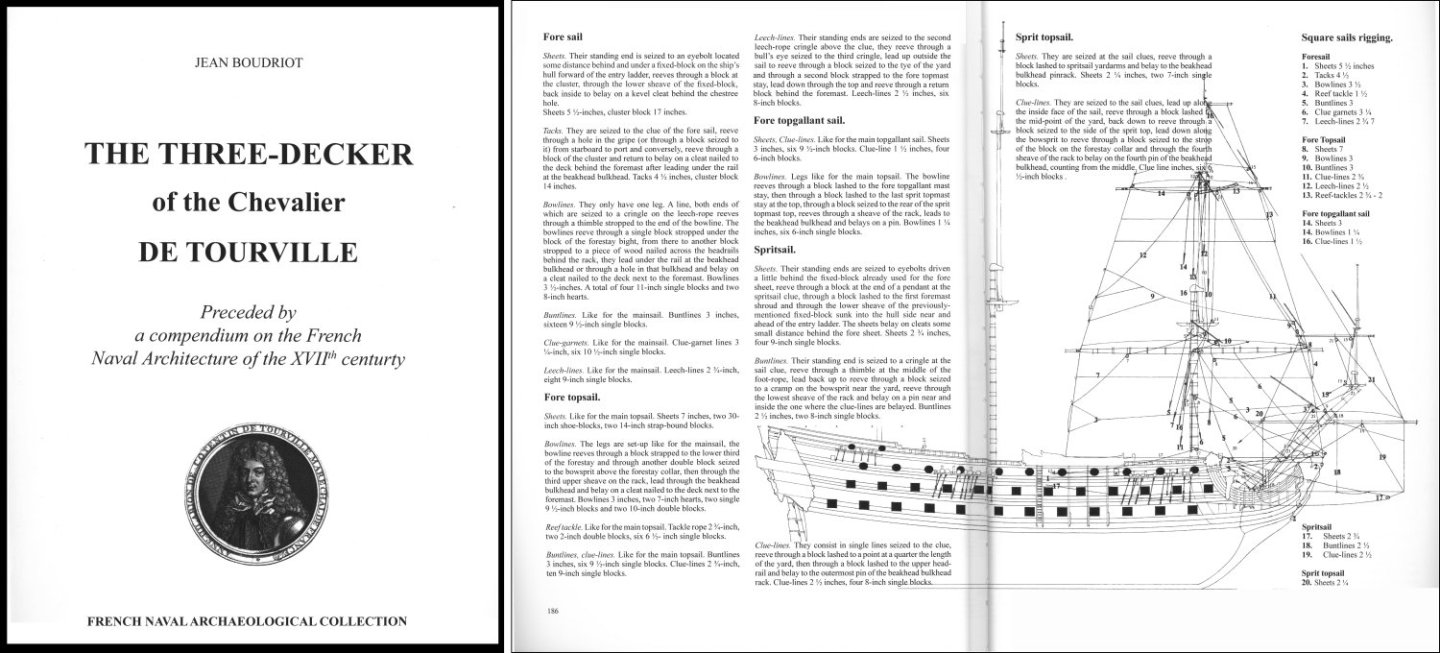

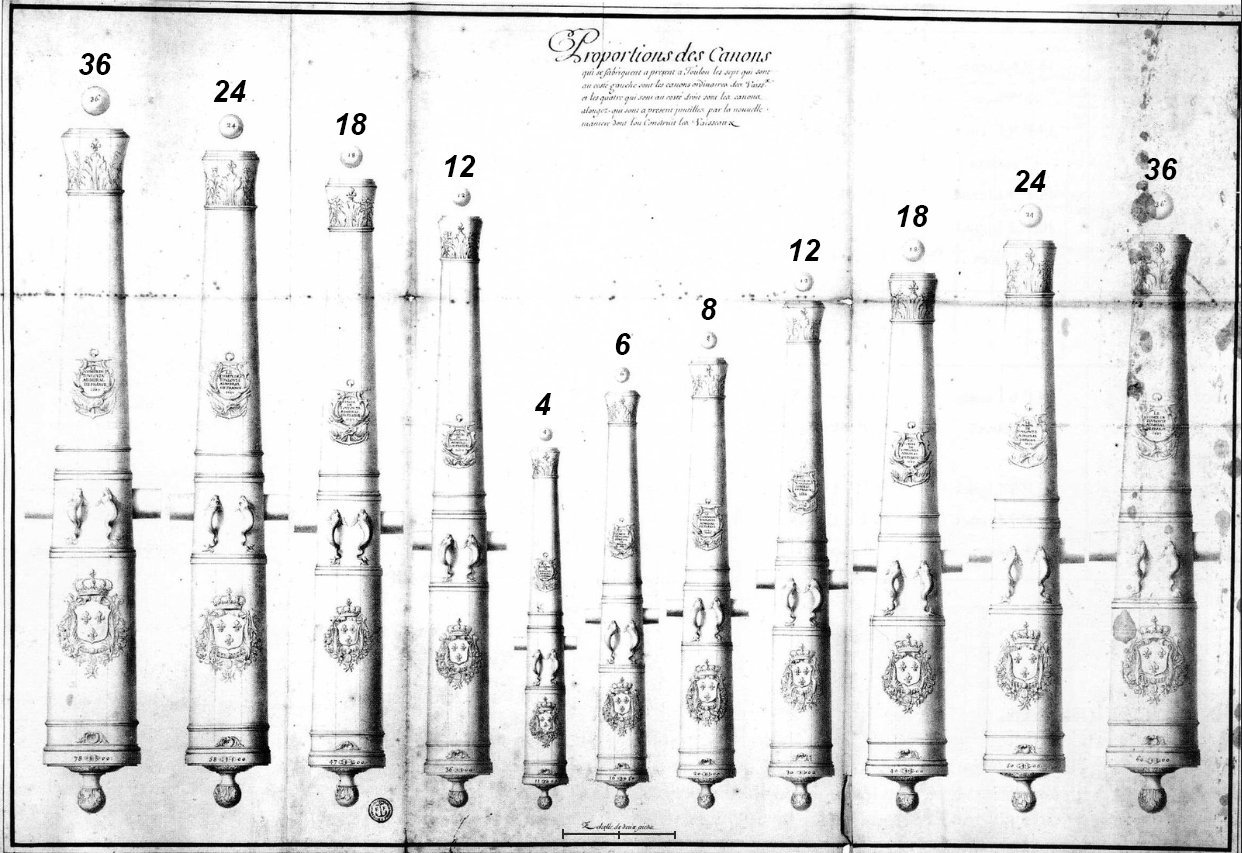

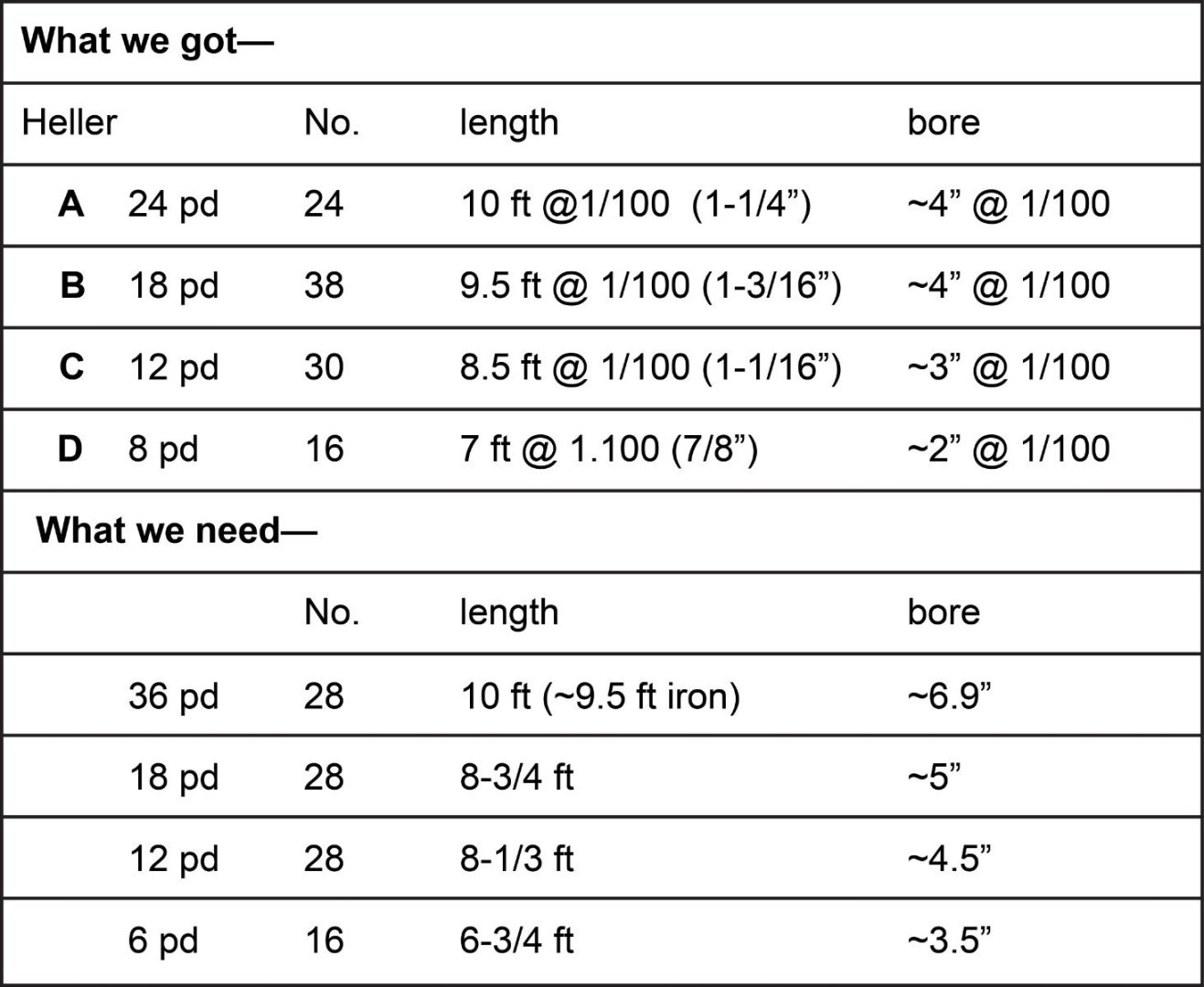

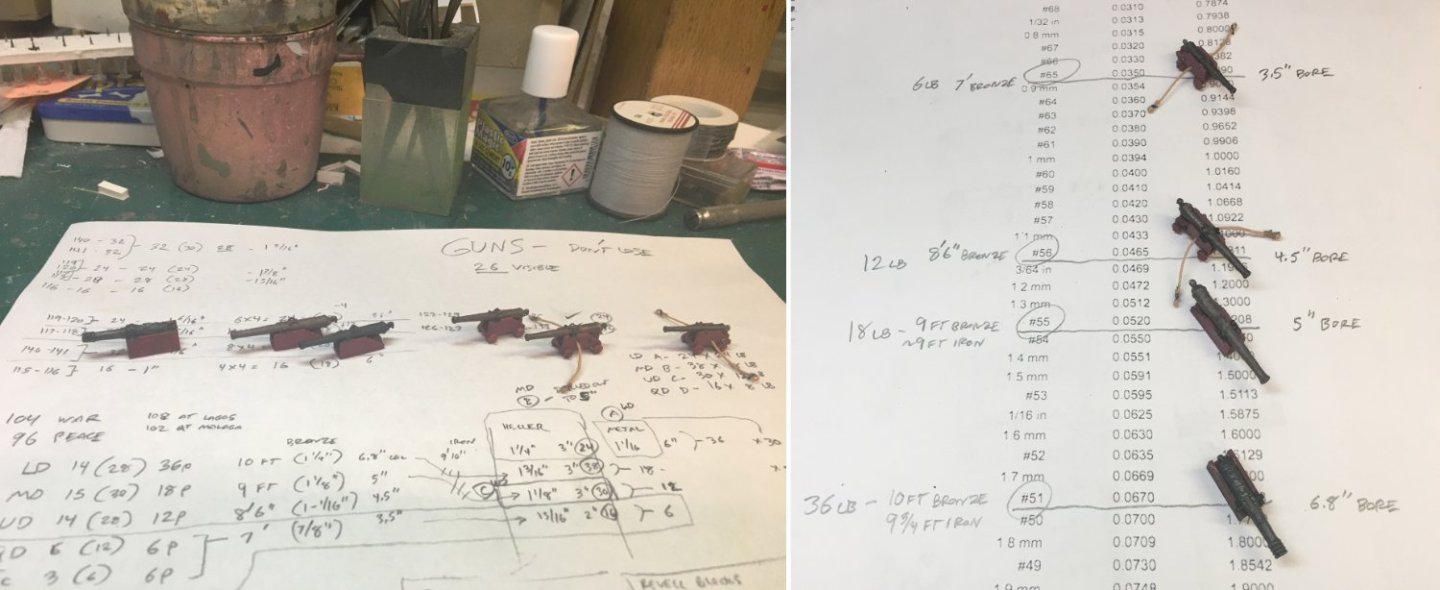

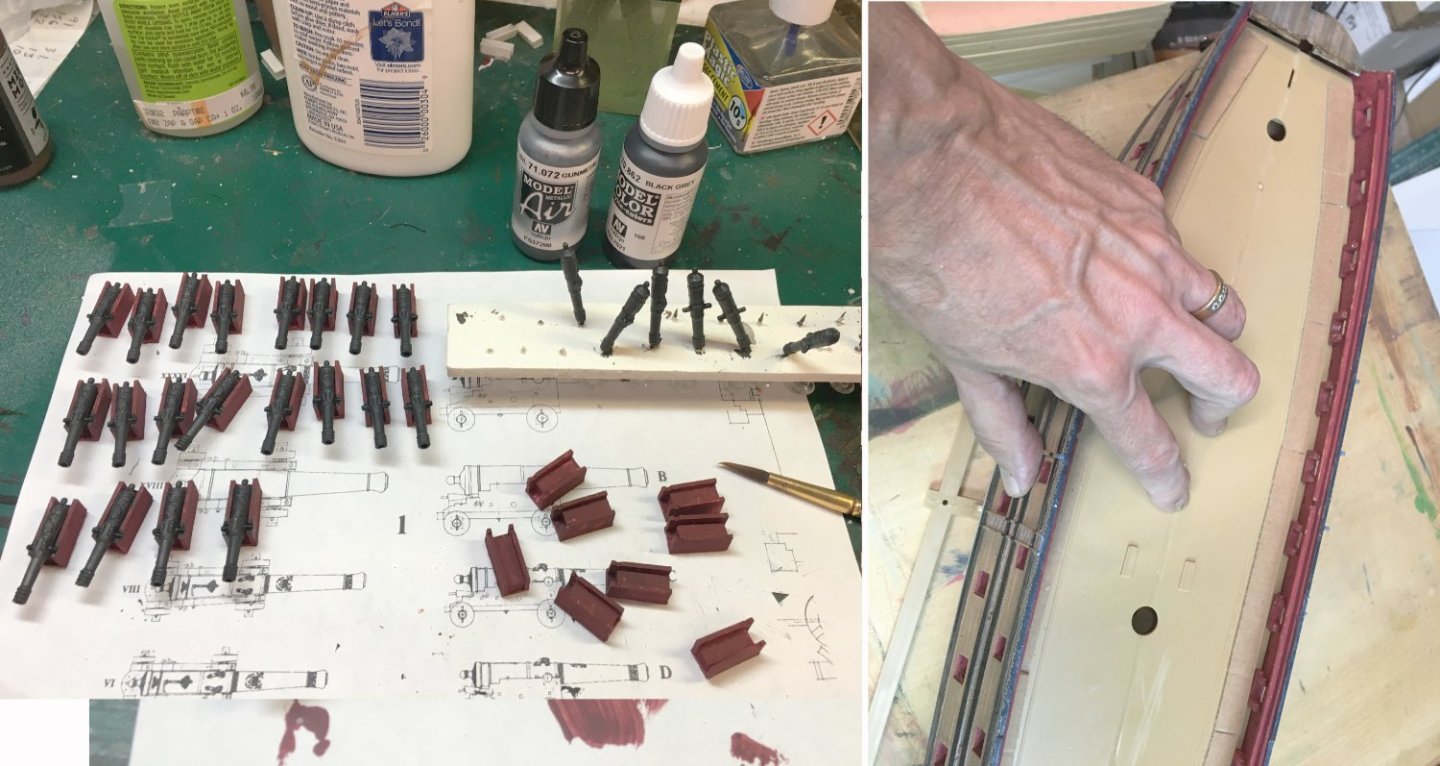

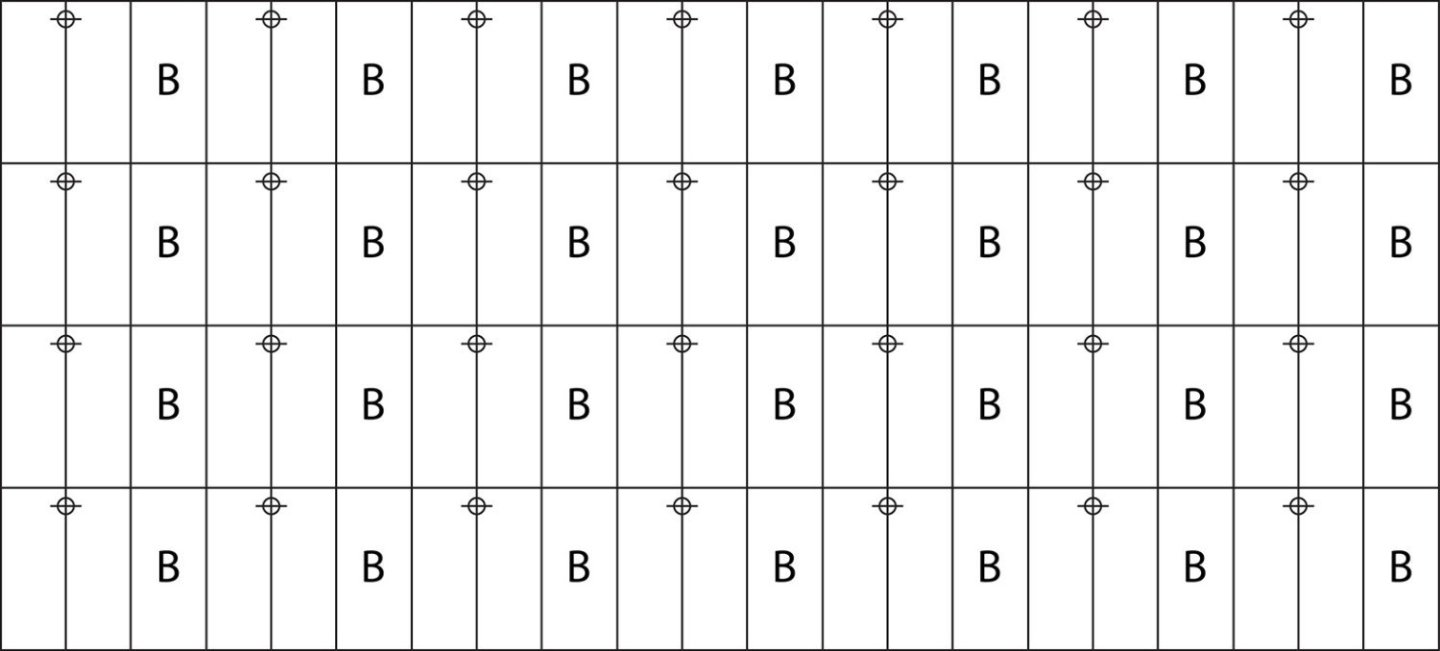

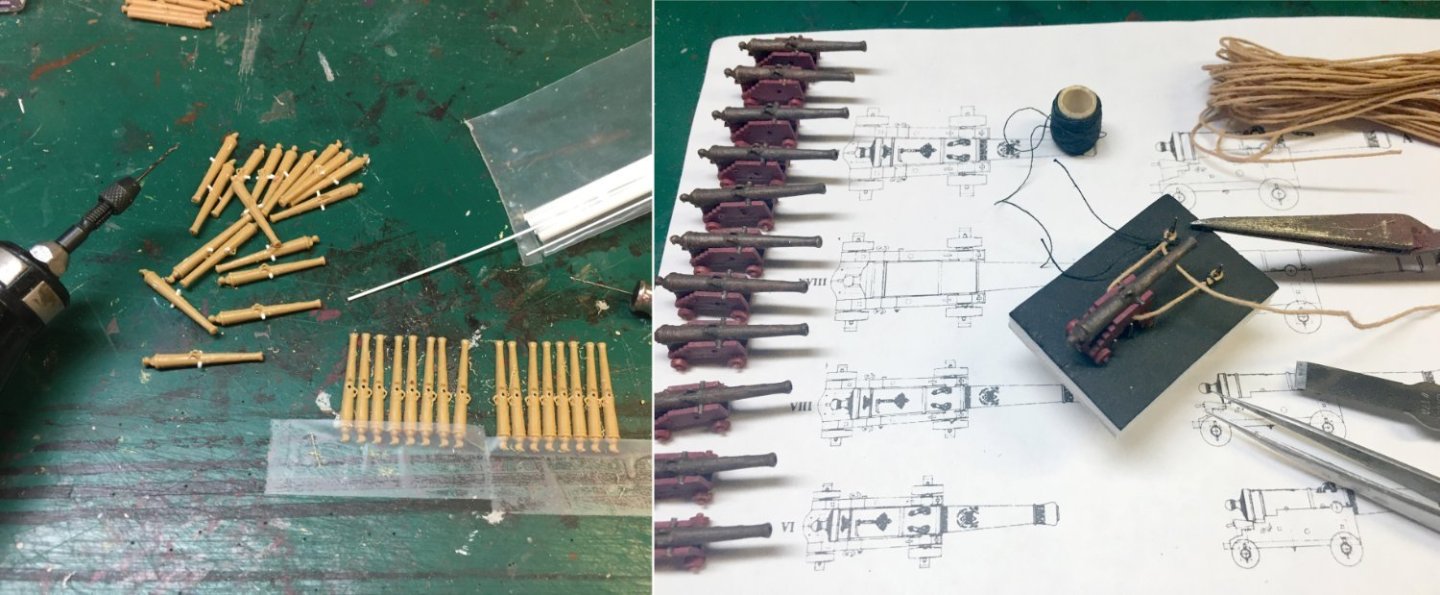

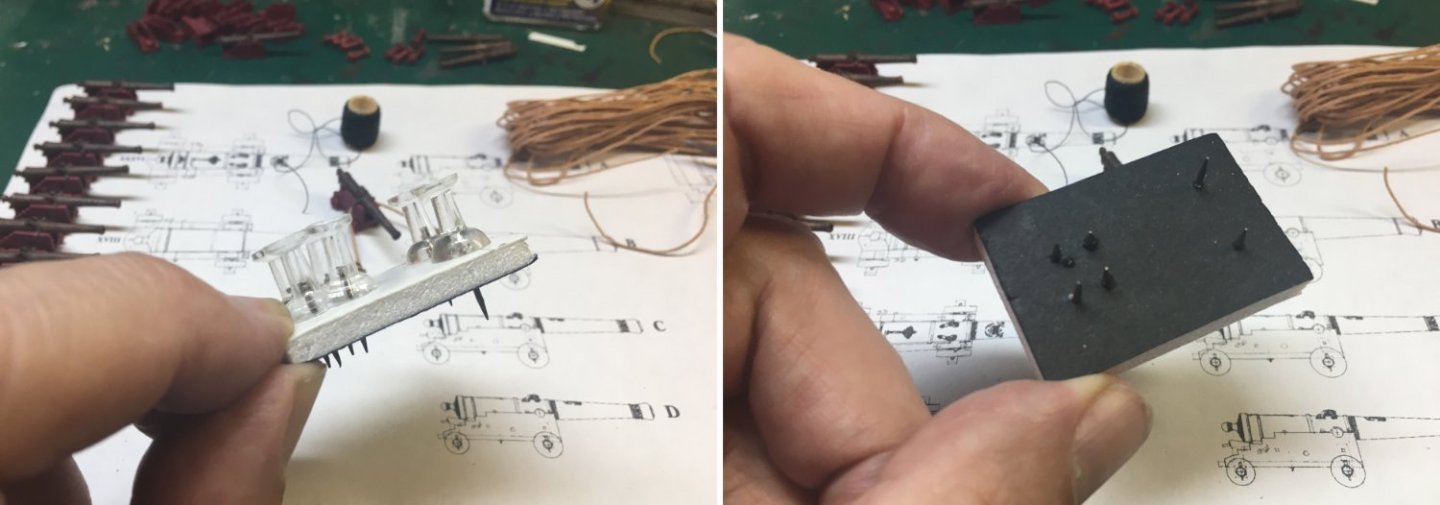

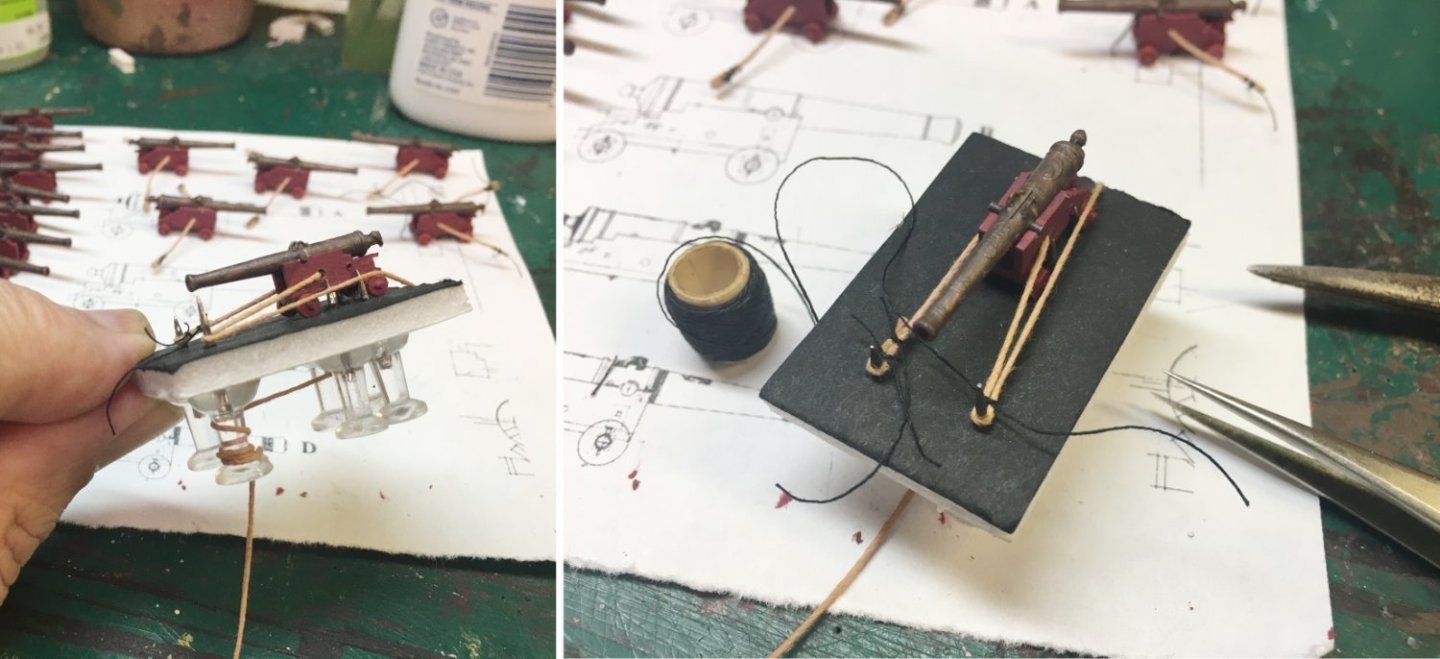

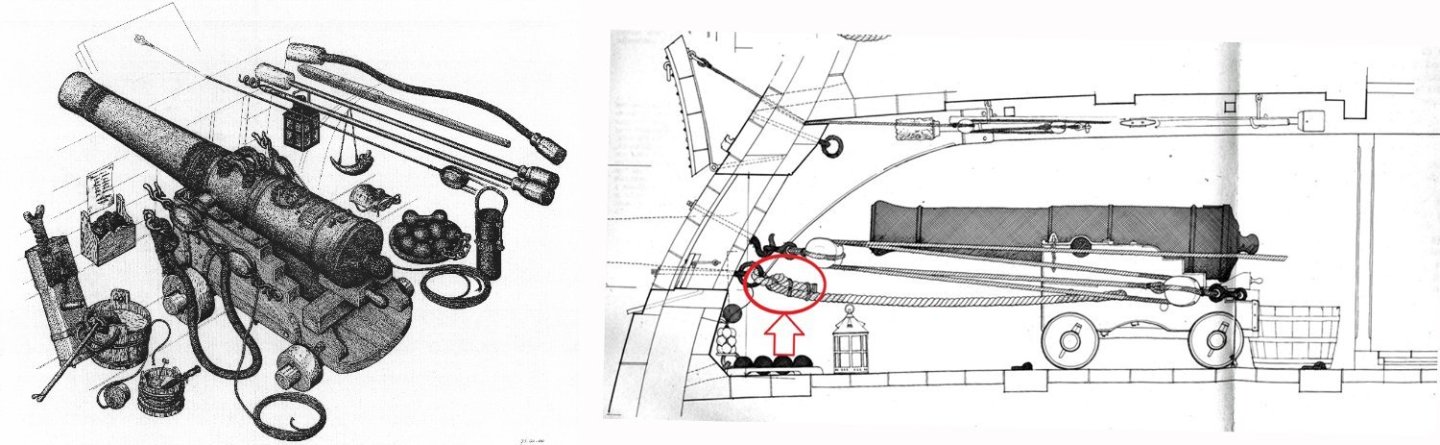

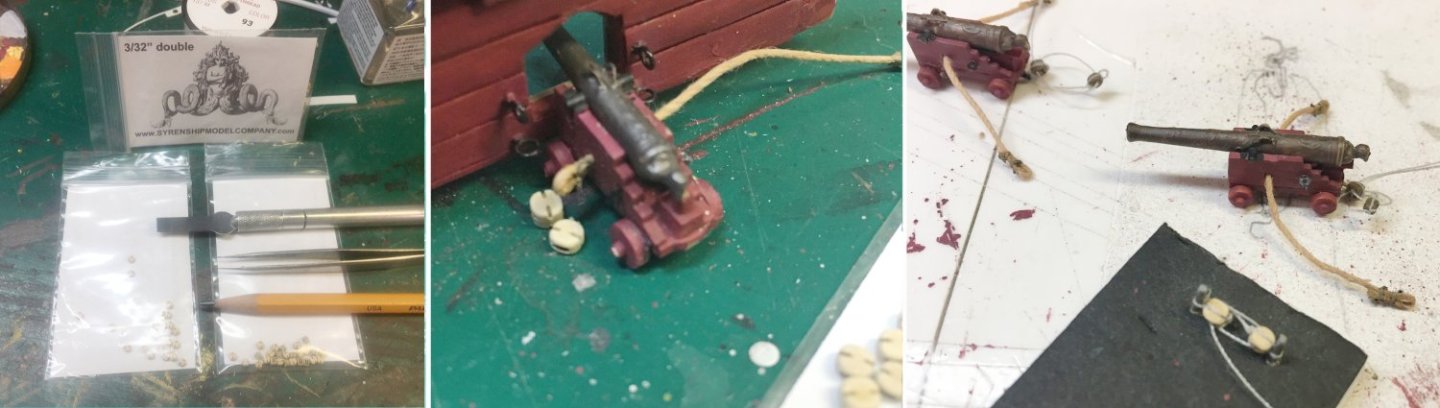

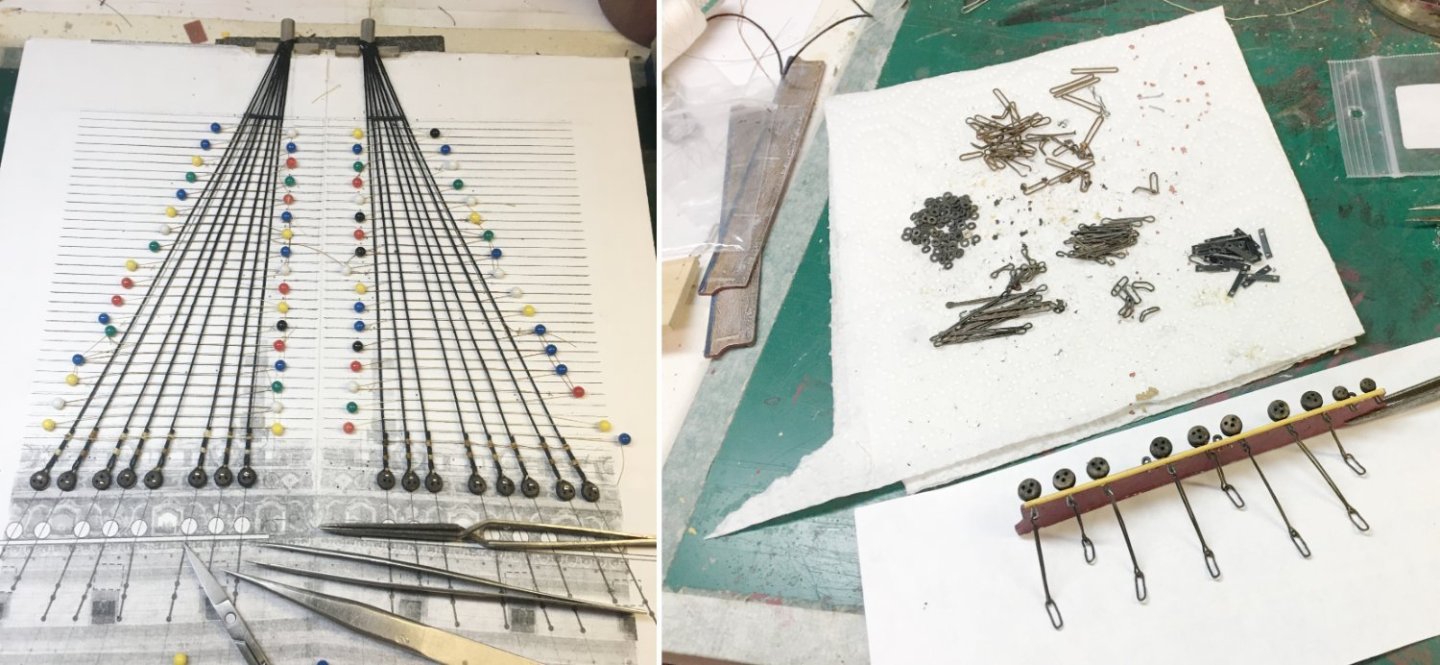

The side of my desk is stacked with books used to support my Soleil Royal project. There will be the matter of finding shelf space for them eventually, since all my bookcases are overloaded, but I'll worry about that sometime in the future, after the build is done. Having good sources to consult for how-things-worked and how-things-looked is part of the fun of model-building for me. Others can do just fine with following the kit directions and come up with a nice model, but for me, that misses out on a lot of the enjoyment. Art needs context. Unfortunately, when it comes to the Soleil Royal, you can't just drive down to Brookhurst Hobbies or The Last Grenadier (or whatever your hobby shop is) and buy a Squadron book written especially for model-builders. Baroque ships are somewhere off the map of popular model-building. You have to find out about sources from other model-builders who have been down the same road before you. So, in that spirit, here are my main text acquisitions that have helped (and will still help me) in my Soleil Royal build. If you have others of your own, PLEASE add them in the comments. French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626-1786 by Rif Winfield and Stephen Roberts. Just really handy, basic stuff. Contains capsule specs, dates, and historical summaries of every French ship from the Baroque. Also includes short summaries of all the wars and battles, ship technology, and gunnery. Find a copy on Amazon— Kindle 4.99, hardcover 60.54, used from 49.98. (I checked just before writing this.) The Three-Decker of the Chevalier De Tourville by Jean Boudroit. This is the best book I've got on referencing and detailing three-decker French Baroque warships. There's a much better review than mine on Ships of Scale: https://shipsofscale.com/sosforums/threads/the-three-decker-of-the-chevalier-de-tourville-le-trois-ponts-du-chevalier-de-tourville-l%E2%80%99ambitieux-1680-by-jean-boudriot.4253/ The book is broken into two parts. The front part, "A compendium on the French Naval Architecture of the XVII Century," is a detailed exegesis on the attempts of Louis XIV's bureaucracy to standardize shipbuilding, including all the letters and documents outlining what the sizes and structures of the ships should be. (This was largely ignored by the shipbuilders, but that's another matter.) It contains a ship-by-ship review of ALL the surviving plans, drawings, and documents in the Paris Marine Museum. The second part is Boudroit's generic reconstruction of a three-decker warship ("L'Ambitieux"), complete with plans, drawings, and specifications for EVERYTHING, including deck furniture, rigging, and belaying points. I know there's been pushback from modelers on some of Jean Boudroit's conclusions. Your mileage may vary. Boudroit also wrote several monographs that I haven't seen on the ships of this period. Based on what I've seen here, if I were rich, I'd get them all. You can get an English-language translation of this book from the publisher, ANCRE. 50 euros plus shipping: https://ancre.fr/en/monograph/68-monographie-de-l-ambitieux-vaisseau-3-ponts-1680.html#/langue-anglais The Construction and Fitting of the English Man of War 1650–1850 by Peter Goodwin. This one is a good explanatory text on the frame-by-frame structure of a Baroque ship-of-the-line—keel, beams, knees, timbers, planking, bulkheads, fittings—that sort of thing. The "English" part shouldn't scare anyone off. Shipbuilding technology wasn't all that different across the Channel in the nation of shopkeepers. Plenty of drawings and diagrams. Really good for figuring out the details of the hull, what sizes they were, where things go, and how they worked. Amazon—hardcover 45.41, used 23.53. The Sailor's Lexicon by Adm. W.H. Smyth. I'm a train modeler. I needed this. Badly. It's a good way to keep terminology at least halfway straight when deciphering the logs of other ship modelers, who will always know much more about ships than you do. Amazon—hardcover 12.15, used from 10.00. The Sun King's Vessels (aka Ships of the Sun King) by Jean-Claude Lemineur. A scholarly study of the development of three-decker French warships in Louis XIV's time and the development of standards for the various ranks of warships. Kind of similar to Boudroit's book. Lots of basic information on the layout and structure of the ships—distance between gunports, overall ship length—stuff like that. Good sections on ship decoration and ordinance. Lots of good hull drawings and ship diagrams. There's not much specific to the Soleil Royal simply because not much information has survived, but this provides a good context. Lemineur also wrote a detailed monograph and ship plans for the three-decker Saint Philippe that I haven't seen, though many modelers swear by it. Amazon has The Sun King's Vessels in English. It's a poor translation that reads like somebody ran the original text through Google Translate, and a lousy layout done by someone who didn't understand typesetting, but all the pictures and diagrams are there and you can make sense of the text with a little work. Hardcover 129.00. Ship Decoration 1630–1780 by Andrew Peters. A book on ship decoration by a guy who decorates ships—at least, reproductions of historical ships. This is more of an art book, but a must-have for anyone who admires and wants to understand the decoration schemes of English, French, Dutch, and other northern European Baroque ships. Want to know why Jean Bérain was different from Charles Le Brun or Pierre Puget? It's all discussed from an artistic and art-historical standpoint. I love this book. Amazon—Kindle 4.99, hardcover 42.09, used from 30.28. The Rigging of Ships in the Days of the Spritsail Topmast, 1600–1720, by R.C. Anderson. This is your first stop for rigging Baroque ships. Anderson's text is well-organized, very readable, and has lots and lots of illustrations. The text is divided up into standing rigging and running rigging sections. He points out where French practice differs from English practice, and gives approximate dates for innovations. It's written by a ship modeler for other ship modelers. Before getting into the weeds with detailed rigging diagrams, read Anderson first. Amazon—Kindle 9.99, softcover 16.94, used from 3.84. So cheap, I can't imagine anyone doing without this book. Eighteenth-century Rigs & Rigging by Karl Marquardt. After you finish Anderson, you'll think this is Anderson on steroids. Every line and every block is broken down mast by mast, yardarm by yardarm, and sail by sail. Not only for big three-masted ships, but every class of ships, galleys, or boats from the era, no matter which nation. Marquardt also includes tables of rope and block sizes taken from period documents, plus complete belaying diagrams. In spite of the title, Marquardt also includes a healthy amount of information specific to the 17th century. He includes French terminology for every piece of rigging. (A bowsprit shroud collar is a collier de hauban de beaupré.) There are many, many more diagrams than found in Anderson. It's easy to get totally lost in Marquardt, which is why I recommend reading Anderson first. Still, this book is indispensable to me. Amazon—hardcover 90.35, used from 89.95. French Naval Sculpture Under the Ancien Régime (1650–1789) by Ronald Portanier. This is a free PDF available from the website below. It's the author's doctoral thesis on the decoration of french warships and goes into great detail on each aspect of the French process of ship decoration, including how the sculptures were made and how they were finished before installation. It's another art book, in essence, but a treasure trove of information on the bureaucrats, artists, and sculptors responsible for the ships, with lots of illustrations. It's free. Get it. https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/id/eprint/984742/1/Portanier_PhD_S2019.pdf So what else have I missed? Please let me know your indispensable references in the replies. In the meantime, here's what I did with my kit's unextraordinary ordinance. I needed a couple of decks' worth of guns before I could start gluing the hull together. Other people have remarked on the issues with the kit’s guns. Trunnions, carriages, cascabels, calibres, lack of rigging, and just plain general sizes and proportions could use improvement. Fixing and detailing 100 guns is a deep rabbit-hole. To start from scratch, the 1704 version of the ship (the one I’m modeling) needed 28 36-pounders (lower gundeck), 30 18-pounders (middle), 28 12-pounders (upper), and 16 6-pounders (quarterdeck and forecastle). Of these, 26 6- and 12-pounders were going to be on open decks exposed for all to see, needing to be rigged and have all the details right. That’s a lotta guns. The kit provided what it called 24 24-pounders, 38 18-pounders, 30 12-pounders, and 16 8-pounders. Hmmm. It wasn’t hard to go into the books and find the prototype sizes and proportions for the right guns. For instance, a bronze 36-pounder was 10 feet long and had a calibre of 6.88”. An iron barrel of the same calibre was closer to 9-1/2 feet. In the time period I was modeling, bronze guns predominated, but iron guns had been introduced and were becoming more common. The kit’s 24-pounders looked too skinny and had too small a calibre to look right. They weren’t fat enough to drill out to the nearly 7” that a real 36-pounder had. They would have to be replaced. A search through all the naval model suppliers on the internet didn’t come up with many options for 1/100 scale. Since most of the guns were just going to be barrels sticking out of gunports, I decided some liberties could be taken with the barrel sizes. The calibre would be more of a consideration than the length. I penciled up a table— I found some right-sized (fat) guns to represent the 36-pounders on eBay and bought 30 of them. They were only 7.5 scale feet long, but nobody would see anything except their muzzles sticking out from the lower gundeck. More importantly, they had a nice 6”–7” bore. I found out later that they were probably modeled after guns from a century or more after the time of the Soleil, but ehhh. I wasn’t going to take the ship apart to replace them. I decided they were iron 36-pounders instead of bronze, so they were painted black. (The real iron guns were.) If you don’t want things noticed, paint them black. The kit’s 24-pounders became the middle gundeck’s 18-pounders, muzzles drilled out with a #55 bit to get close to a 5” bore. I kept the kit’s 12-pounders, just drilled them with a #56 bit to make 4.5” bores. The kit’s 8-pounders became the 6-pounders, drilled out with a #65 to a scale 3.5”. Four of the kit’s 18-pounders became “iron” 18-pounders instead of bronze—slightly smaller, painted black, and drilled out to the 5” bore. That made up for the shortage of 18-pounders. The rest of the kit’s 18-pounders were surplus. Most of the guns were supposed to be new bronze, but the hobby shop was out of anything closely resembling bronze paint. I mixed my own, using Mission Model’s dark rust and Vallejo 71.072 gunmetal. It came out a rich, shiny, metallic dark brown—just like recently-cast bronze. I didn’t want even a hint of green patina. Most of the guns in the rapidly-growing French fleet of the 1690s were newly-cast, and I imagine gunner’s mates would risk a flogging if their weapons weren’t cleaned, vinegared, and shined. This was the king’s ship, after all. I was going to prepare two classes of guns. The ones hidden in the lower decks were going to be rudimentary, just the barrel sitting on a wheel-less carriage. No rigging or detailing. The 26 visible on the open decks were going to get all their “Hellerisms” corrected—trunnions in the right place, carriages with proper seats for the trunnions, eyebolts for the gun rigging, and holes drilled in the sides of the carriages for the breech ropes. The new lower deck gun barrels from eBay needed something to sit on. I fashioned some simple styrene boxes. Because they and the middle deck guns were going to be mostly hidden, their carriages didn’t have to sit on four tiny wheels with four tiny glue points to come loose. I wanted a bigger and stronger mounting surface that was just a little flexible so that if a gun was accidentally bumped, it might still stay in place. Here's the template I made for the boxes. It got spray-glued to a sheet of 1 mm styrene and used to drill and cut. This ain't to scale, in case anyone is wondering—it's just to show the principle. When it came time to glue the hull together, I attached some corrugated cardboard strips to the decks and glued the flat bottoms of the wheel-less carriages to them. The dressy, visible guns got new trunnions (Evergreen styrene 1.2 mm rod) and breech ropes. The carriages had the raised trunnion blocks carved away, new slots for the trunnions filed in, and holes drilled into the carriage sides for the rigging eyes and breech ropes. The breech rope stock (kite string) was white—ugly and not looking like rope—so about five feet of it got stretched and stained with the same cork brown color I used for the hull and decks. It helped. A little jig made from foam-core board and push-pins insured the breech ropes were all the same length. I didn't bother with too many gun carriage details. I figured things like bolts, etc. weren't going to be noticeable anyway. Some black paint made it look like the trunnions had top brackets. Eyebolts for gun tackle were added to the carriage sides. So far so easy. In the meantime, I was trying to figure out how I was going to do the gun rigging. There were plenty of good diagrams on the internet. The main problem foreseen was dealing with all those tiny blocks. First task—where to get them? I ordered from a few different suppliers. Most were way too large, but Syren blocks were beautiful and small enough for the 12-pounders. Still too large for the 6-pounders, though. I finally got some 2mm blocks from HISmodels, which I used on the 6-pounders. If I had to start over, I would have used them from the beginning. I figured that it was easier to work on the gun rigging with all the pieces on the workbench, so the bulwarks got their guns tied to them before getting glued to the ship. All those blocks and lines… I think each gun needed sixteen knots. This is probably one reason why I build only one sailing ship per decade. It usually came out all right in the end. I’ve seen all the drawings and diagrams that show the gun tackle ropes in neat inspection-ready coils, but I wonder what the gun crews really did with their lines. I didn’t glue the coils down all that securely just in case I see something that changes my mind. I was getting closer to gluing the ship's hull together. I needed to work on the bow and stern first. That'll be in the next post. But now that it's October, I'm finally going on my summer vacation. I'll finally (hopefully) get to make some progress on rigging my ship. (Below are experiments that may or may not work.) See you in two weeks.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

I'm with you there. I always thought Van de Velde was a more reliable authority because he obviously knew ships well and made his drawings after they were reality, while Bérain's and Puget's drawings were more... aspirational.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Marc—the Furieux drawings are interesting because they have the same problems as Bérain's Soleil drawings—the stern and quarter drawings don't match up. I can understand why Bérain drew the stern asymmetrical, since they were proposal drawings, after all ("which do you prefer, monsieur?"), but someone in the office of ship decoration is going to look at those figures under the wing transom and say some bad words. Maybe Bérain was rushed, maybe he was overloaded with work from Versailles, or most likely he was just unfamiliar with the geometry of a ship. Is there any indication he even visited Brest or spoke to the shipbuilders, or did anything other than exchange letters and drawings? I honestly think the drawings were meant to be advisory only, and nobody expected the ship-decorators to follow them precisely. Still, Le Furieux would make a great modeling project for some brave soul. Lemineur has a drawing of the same class (66 guns, not 88 like I accidentally typed) in his Sun King's Vessels book.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Nice furniture, light walls, wood floor, no carpet, nice, well-lit corner. No clutter, everything necessary in easy reach. A great setting for building and rigging a great model. Of course you know you're making the rest of us look bad.

- 2,444 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

Henry and Johnny—thanks for giving the correct spelling and usage of "ded reckoning." I kinda knew that, but my unfortunate propensity for joking around got the better of me. I'm not the one to go to for serieux discussion.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hello Marc—here is le Fleuron, 60-gun 3rd-rate, 1689. It was wearing blue in 1704. And here's le Furieux, 70-gun 2nd-rate, 1684. Sorry—I didn't write down where I got these. I also attached a PDF that I made of all the sterns and galleries I could find. (Apologies—it's kind of large.) Used it for quick reference. Many of the images are ehhhh because they were low-resolution swiped off the internet. First & Second Marine Drawings by Date.pdf

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks for the comments, guys. Marc—yeah, I think naval history is pretty dry (ouch!) if you don't consider the personalities aboard the ships deciding what to do. Naval engagements are in many ways like battles between orchestra conductors. I'm sure professional historians would happily rip me a new one for over-dramatization, but I don't care. I like telling stories. Everyone can read the sources and come up with their own. Kirill—thanks much for the information. I'd love to see the books and models you referenced. I went back and forth on the issue of pin rails but finally decided that the model would be more attractive if I used them. Given the other appearance issues with the model, it seemed like a small compromise. Since my aim is to show the Soleil Royal as it more or less looked in the early 1700s, I rationalized it by thinking the ship must have been upgraded and re-rigged when it was recommissioned after sitting idle for eleven years. J.C. Lemineur also seemed to like pin rails. I was influenced by his drawings a lot.

- 80 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-