-

Posts

42 -

Joined

-

Last visited

About John Ott

- Birthday 01/01/1953

Contact Methods

-

Website URL

www.ottgalleries.com

Profile Information

-

Gender

Male

-

Location

Los Angeles

-

Interests

Illustration; several different and ever-changing fields of modeling.

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

BlackDog reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

BlackDog reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

Dan DSilva reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

Dan DSilva reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

Nek0 reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

Nek0 reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

Nek0 reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

Nek0 reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

yvesvidal reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

HiSModel reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

HiSModel reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

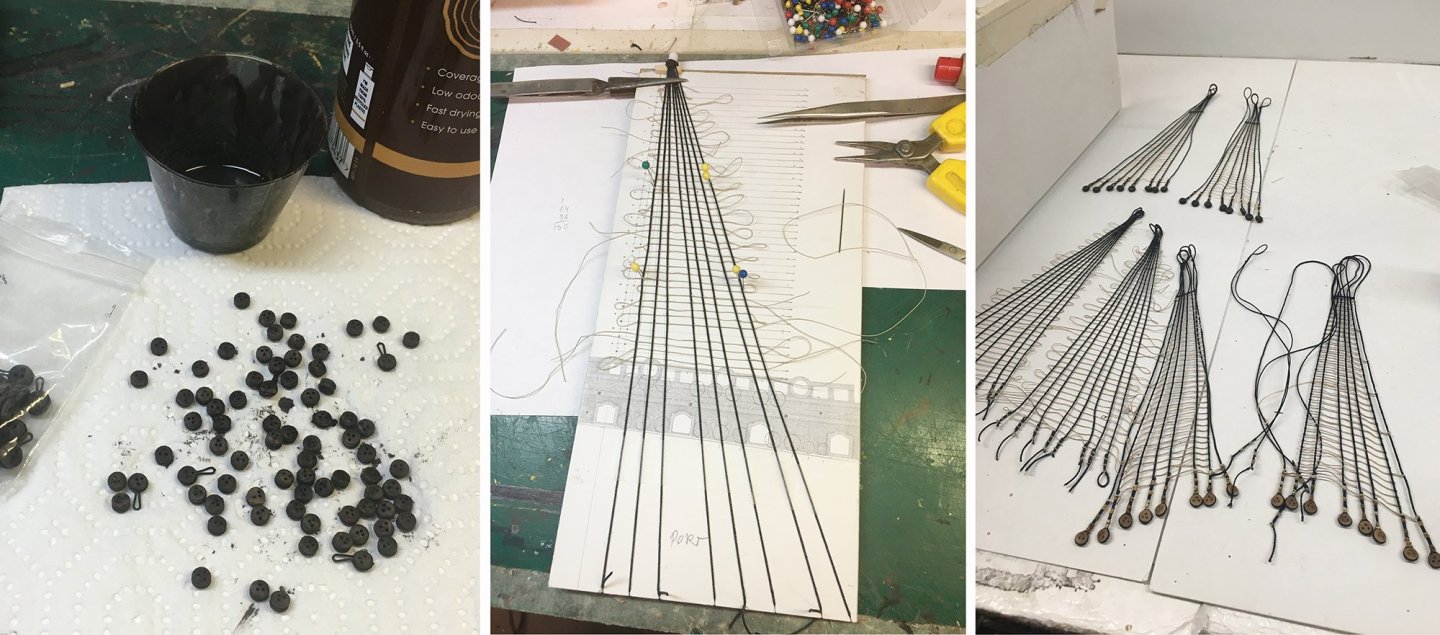

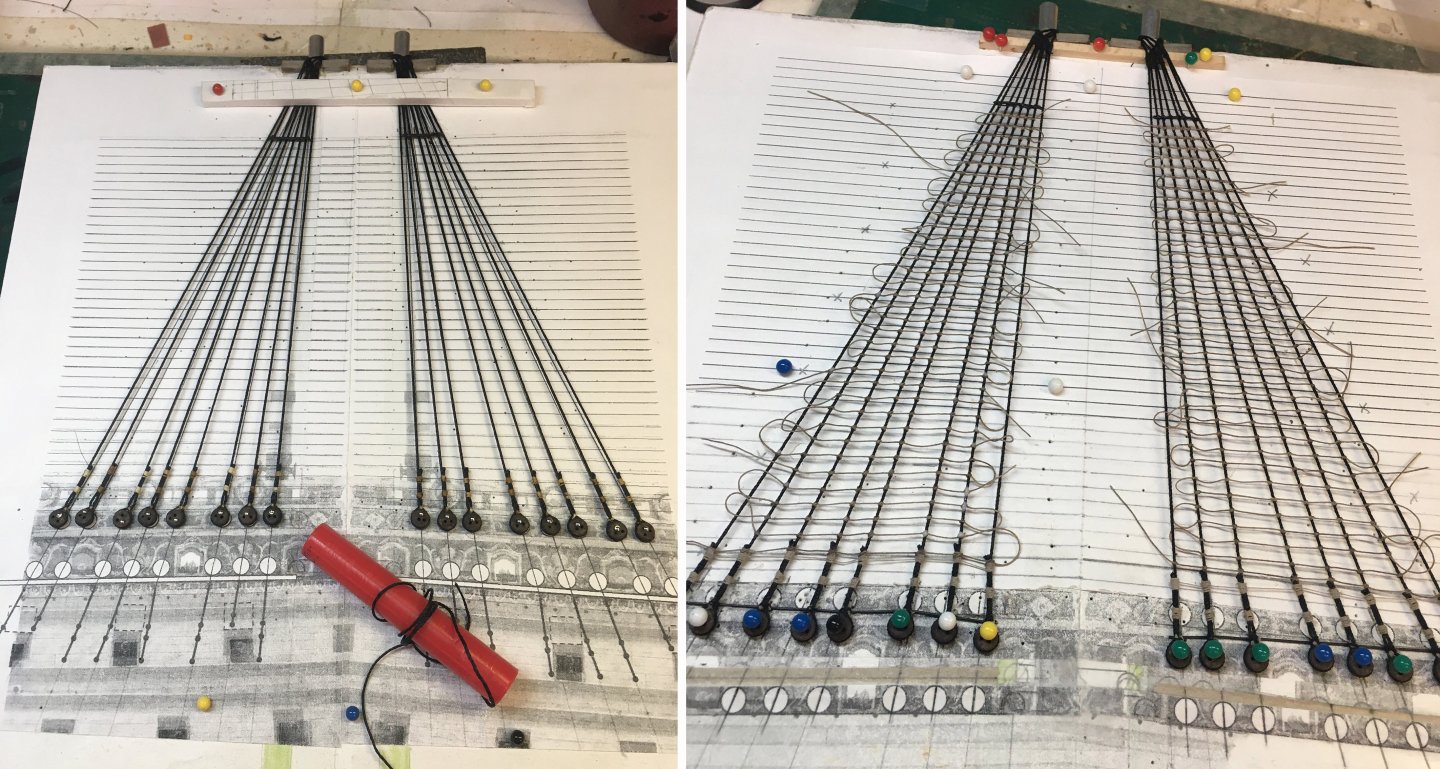

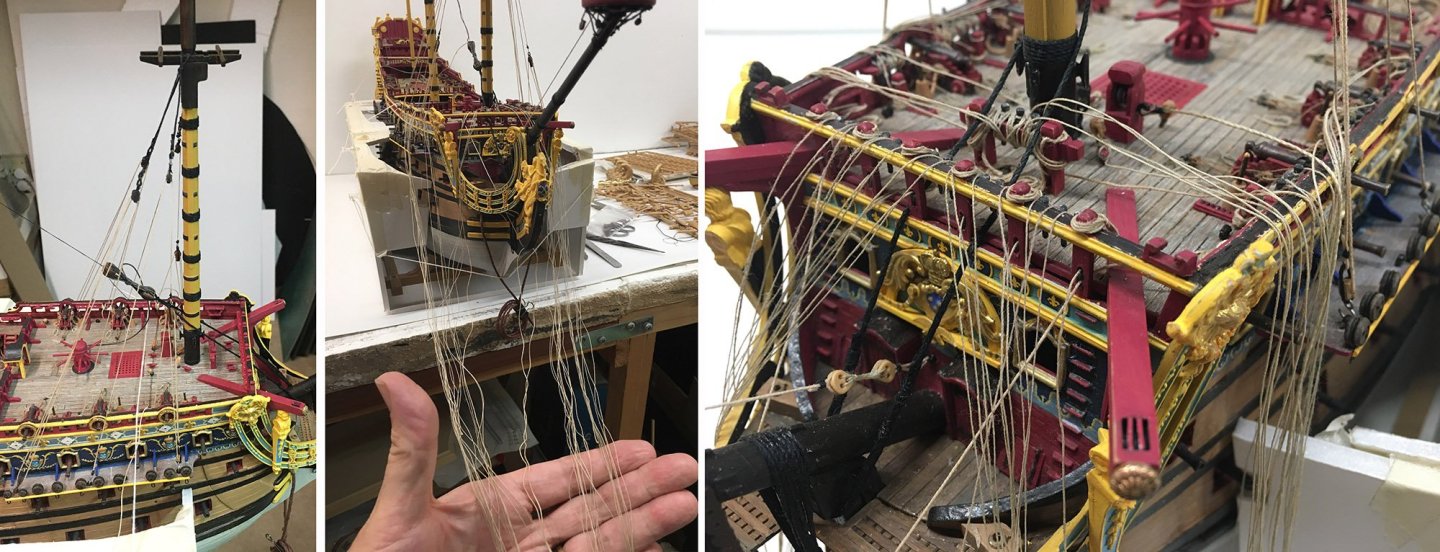

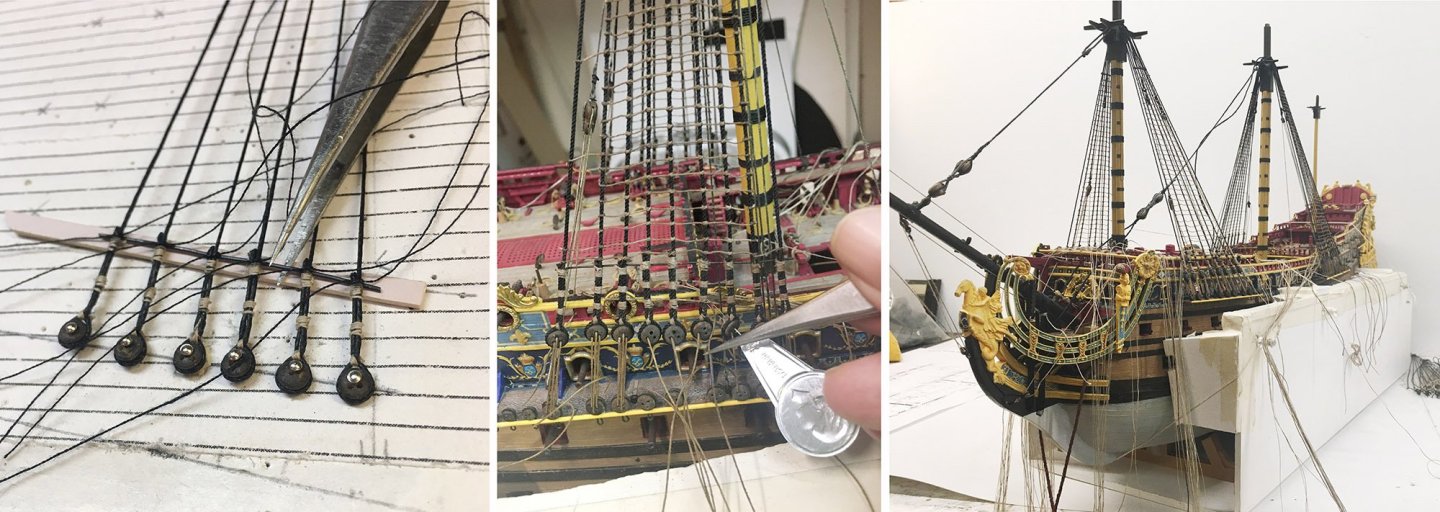

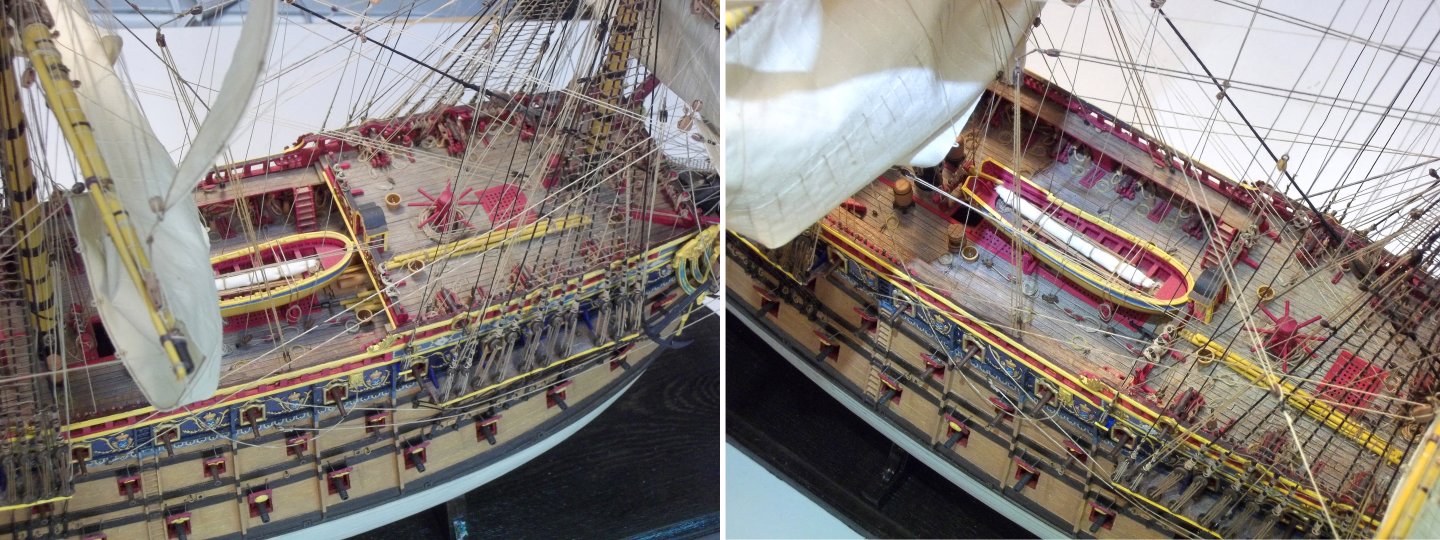

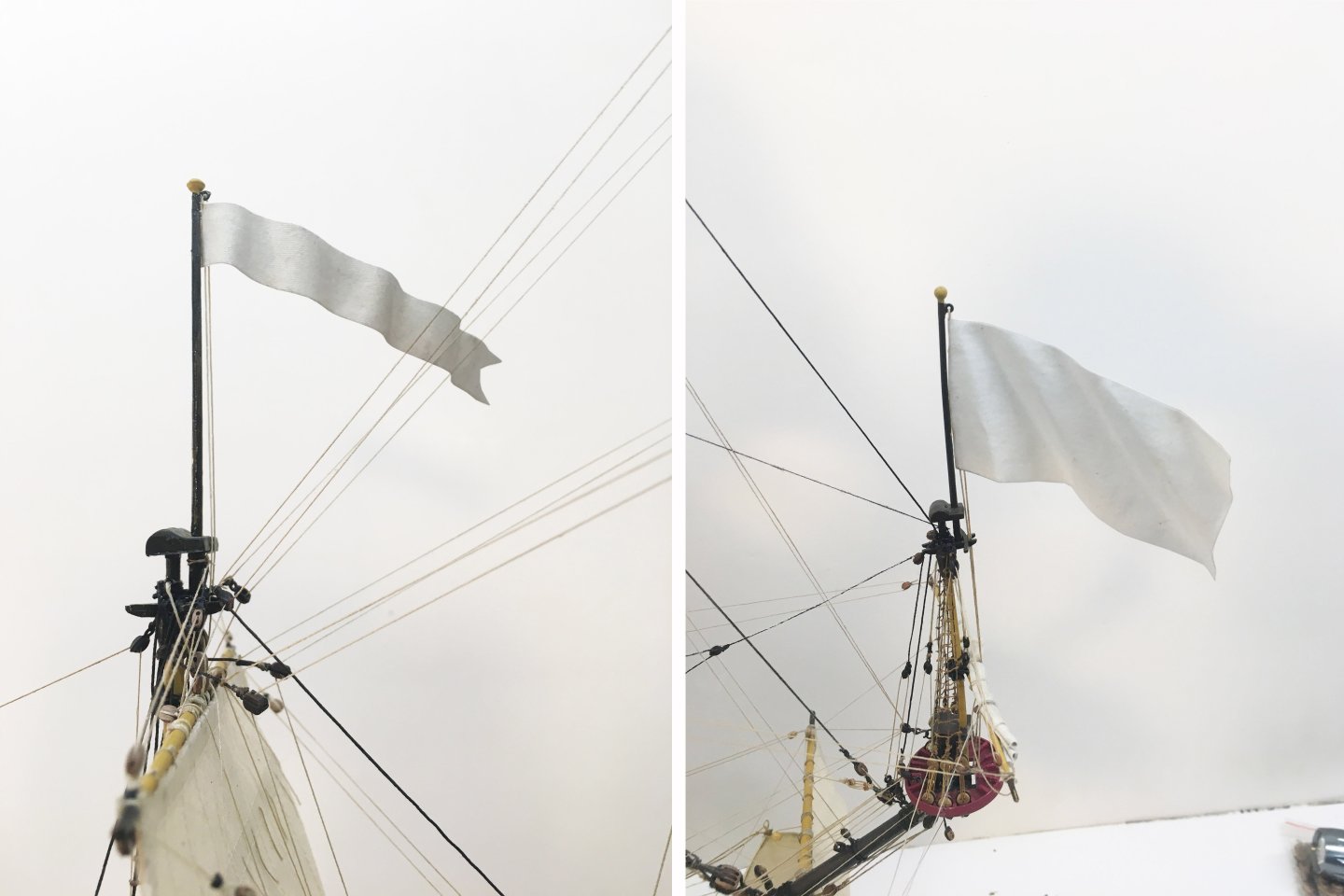

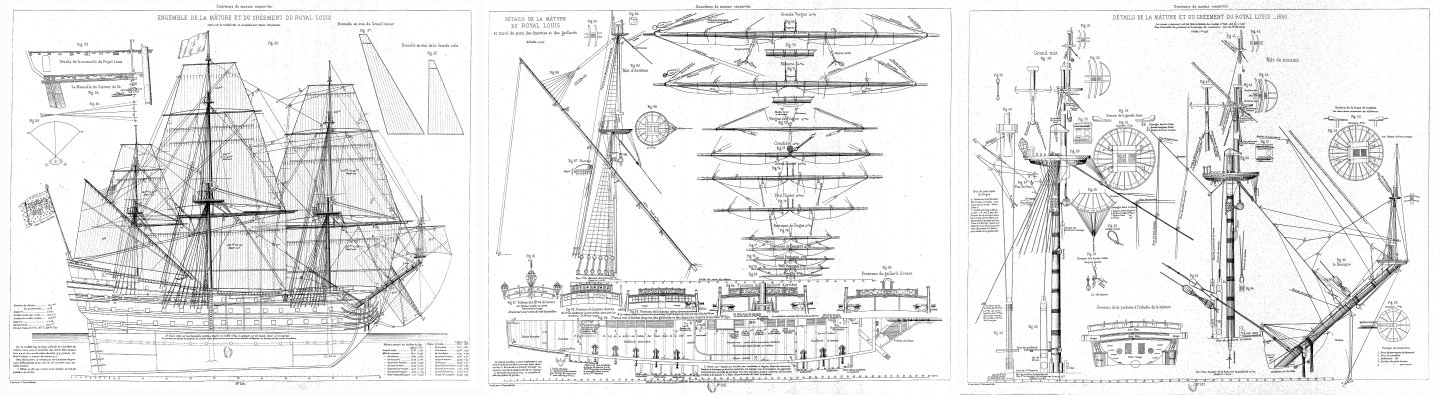

L'ENVOI— Soleil Royal 1693. It took me 25 months. I had originally figured it would take a year. Little did I know... but it was my first large ship model. When last I posted (August), I had finished the standing rigging and just figured out how to do channels and chains. What followed was four intense months of evenings and weekends dealing with yards, sails, blocks, and miles of thread. I wouldn't know where to start in describing it all. I took photos of the process periodically, but lost many of them when I tried to update the OS on my old phone... I needed the memory space and I thought I had safely transferred the photos... but oh, well. It's not like I had anything revelatory to share. There are plenty of outstanding rigging jobs very well explained on this forum. Mine wouldn't have competed. So enjoy looking at some photos for awhile. We'll talk later. So how did I get here? If I had possessed any sense, I would have stopped the model at the point of having bare masts, but modeling a fully-rigged sailing ship was on my bucket list. It was all about experiencing the process, not the final result, that motivated me. I set aside the Heller kit instructions because they were extraordinarily confusing and complex, used no explanatory nautical terminology, and were suspected of being overly-simplified. Instead, I made up my own sail plan loosely based on the Jérôme Hélyot drawing on his Malaga Battle scroll— topsails bent, mainsails gathered, topgallants furled. This was maybe the appropriate set for keeping in line with the other ships in the squadron. I had help in figuring out the lines and blocks from my old friends Anderson, Boudriot, Petersson, and Marquardt. Those books were never shut. Also very helpful was Admiral Paris's La Souvenirs de Marine and the plans for the 1690 Royal Louis. I had gotten a set of sails, scale rope, and supply of walnut blocks from HISmodel (Hismodel.com), with more ropes and blocks in a variety of sizes from Dry Dock Models (drydockmodelsandparts.com) and Modelers Central (modelerscentral.com). I also had a supply of Revell 1/100 blocks left over from—believe it or not— a pair of Revell ship models damaged in the 1994 Northridge earthquake and subsequently stripped for usable parts. These made good approximations of hearts. I did my best to keep everything organized and find-able when I needed it. The deck furniture on the ship had been simplified, based on what I saw on Boudriot's deck diagrams. Also—as discussed several posts ago—I had decided to install pin rails. This gave me the opportunity to belay lines to the pins before I started to hang yardarms. I was afraid that as things progressed and lines multiplied, I wouldn't be able to get my clumsy hands and tweezers where I needed to belay lines coming from the tops down. So my ship quickly grew a ZZ Top beard. This turned out to be about 80% of the running rig. The HISmodel sails were beautiful. I trimmed the main and foresails from the bottom for a slightly better fit. I first tried sewing on the bolt-ropes, but the additional thread made the edges look clumsy. I ended up gluing on the bolt-ropes with white glue. Likewise, I glued on earrings and cringles. Robands and reef points were sewn in. I used thin acrylic paint to stain some old sheet material with a high thread count to match the HISmodel sails, then cut out short lengths to tie to the topgallant yards (and sprit topsail yard) as furled sails. The same fear of my own rampant clumsiness made me prepare all the yardarms with sails already bent before attempting to place them on the masts. I tied and glued on ties, brace pendants, horses, sheet and lift blocks, and yard tackles. Also clewline, buntline, and leechline blocks. Sails got clewgarnet and sheet blocks at their clews. All at my desk. The Heller kit didn't come with parrels. HISmodel makes a photo-etched set that works out perfectly. All the yardarms except the crossjack and the spritsail yard got parrels. There was plenty for all in the set. I bent the sails starting with the mizzenmast and working forward. All those lines in the ship's "beard" got separated and routed through the appropriate blocks to their points of attachment, yard rigging first, then sails. Ties—lifts—tackles (if any)—clewlines—buntlines—leechlines and reeflines. Then came braces and bowlines. Finally, sheets and tacks. The mizzensail got brails. The studdingsail booms on the fore, mainsail, and topsail yards got outhaul and inhaul lines. Anything that had a knot was only loosely tied, so I could go back and adjust the tension later. When everything was the way I wanted it, the knots got a spot of white glue and the "tails" were cut off. Unfortunately, when it came to routing lines and their belaying points, Anderson, Boudriot, and Marquardt could never agree with each other. Sometimes the routing made no sense on the model anyway. So my rigging plan takes a little from each and simplifies a lot. The biggest influence comes from Boudriot's diagrams and Admiral Paris. Lastly came the flags and banners. I copied Jérôme Hélyot's drawing again, and the national flags are the pure white of the French. Boudriot makes the point in his article on the flags of the Battle of Malaga: "It is important once again to underline the fact that the white flag decorated with fleur-de-lis with the arms of the king, which we see abounding in iconography, and in particular in most of the paintings retracing the great battles, has absolutely no historical reality." The flag on the mainmast is blue, indicating that the Soleil Royal is the flagship of the rear squadron. At first, thanks to adjustments in the clewlines, leechlines, and bowlines, I got the sails looking like they were catching a light wind, but the banners and flags still hung limp. I needed something to stiffen them. A coat of diluted acrylic matt medium did the job. After the medium was dry, the banners could be bent into appropriate wind-ripply shapes. I left the big stern flag un-stiffened because I want to be able to move it from side to side, always keeping it out of the way so that the quarter galleries aren't hidden behind it, no matter which side of the ship I decide to face outward. So this is my last post for this project. Aside from a few touch-ups, I think my Heller Soleil Royal is done. I learned a lot in the process— a lot about how old ships were put together, a lot about Baroque history and the attitudes of that time toward war and art, and a lot about having the patience to complete a lengthy, complex, and demanding model job in an area of expertise I didn't know much about. Also got to discuss things with some very skilled and knowledgeable modelers who continue to amaze and delight me. You know who you are. Will I be back with another ship project? Not soon. I usually get around to building one model ship every ten years. I think I'm good for this decade. Thanks much for reading my log. I hope my misadventures have somehow either inspired you or warned you about which paths to avoid. In previous posts, I warned you all to stay dry— not this time. The water's fine. Get wet. Au revoir. Dieu soit toujours avec toi.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

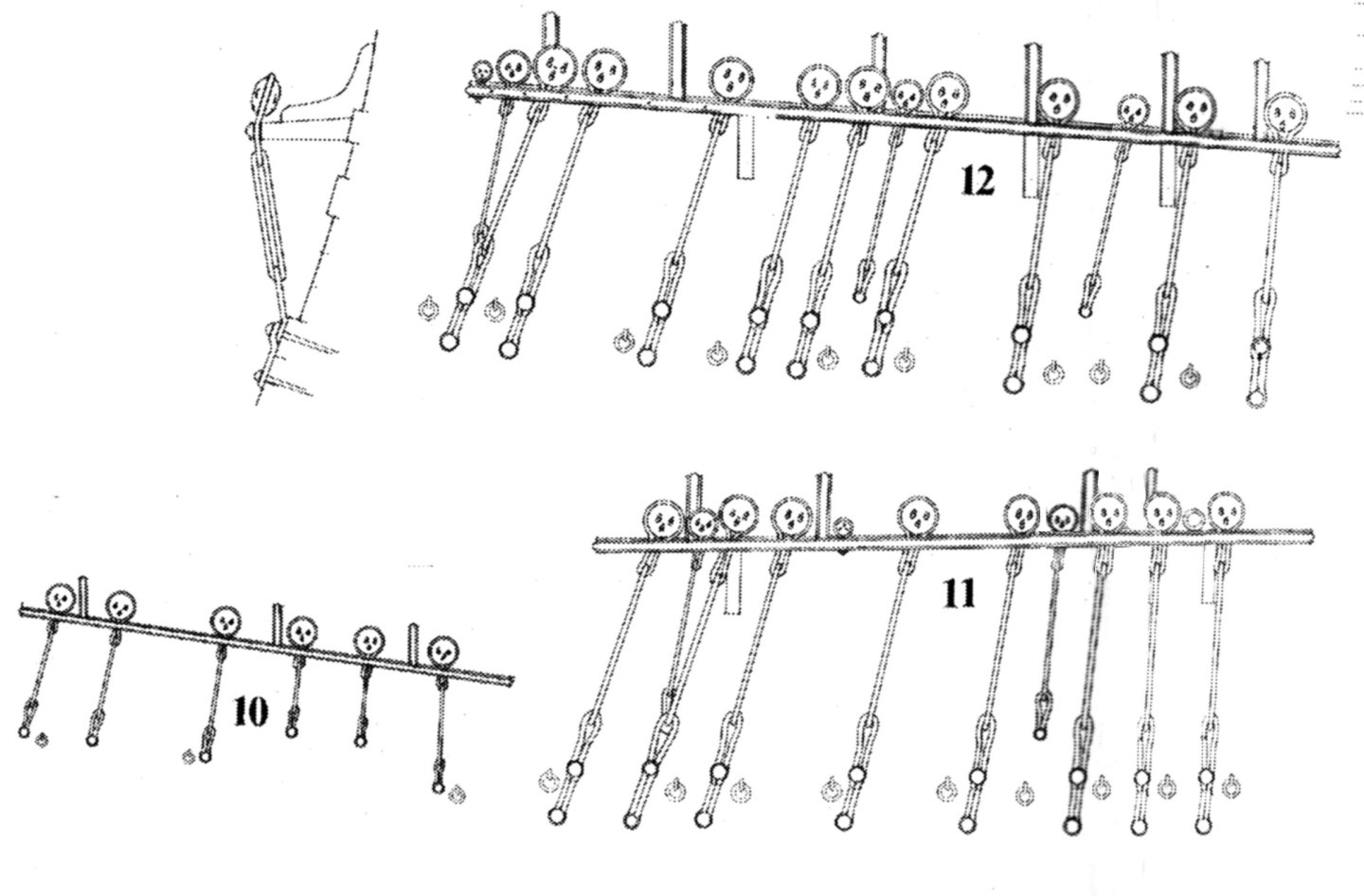

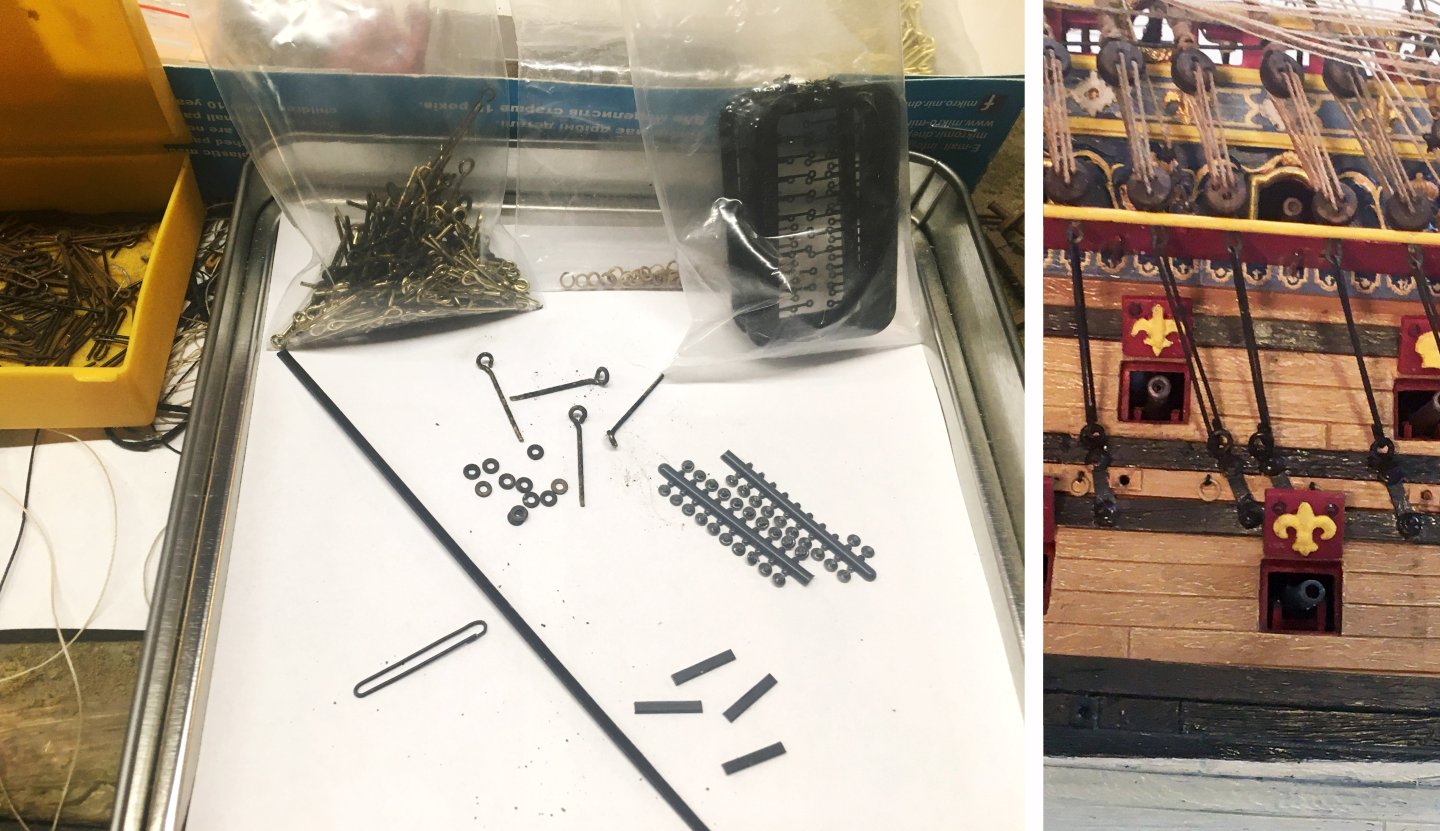

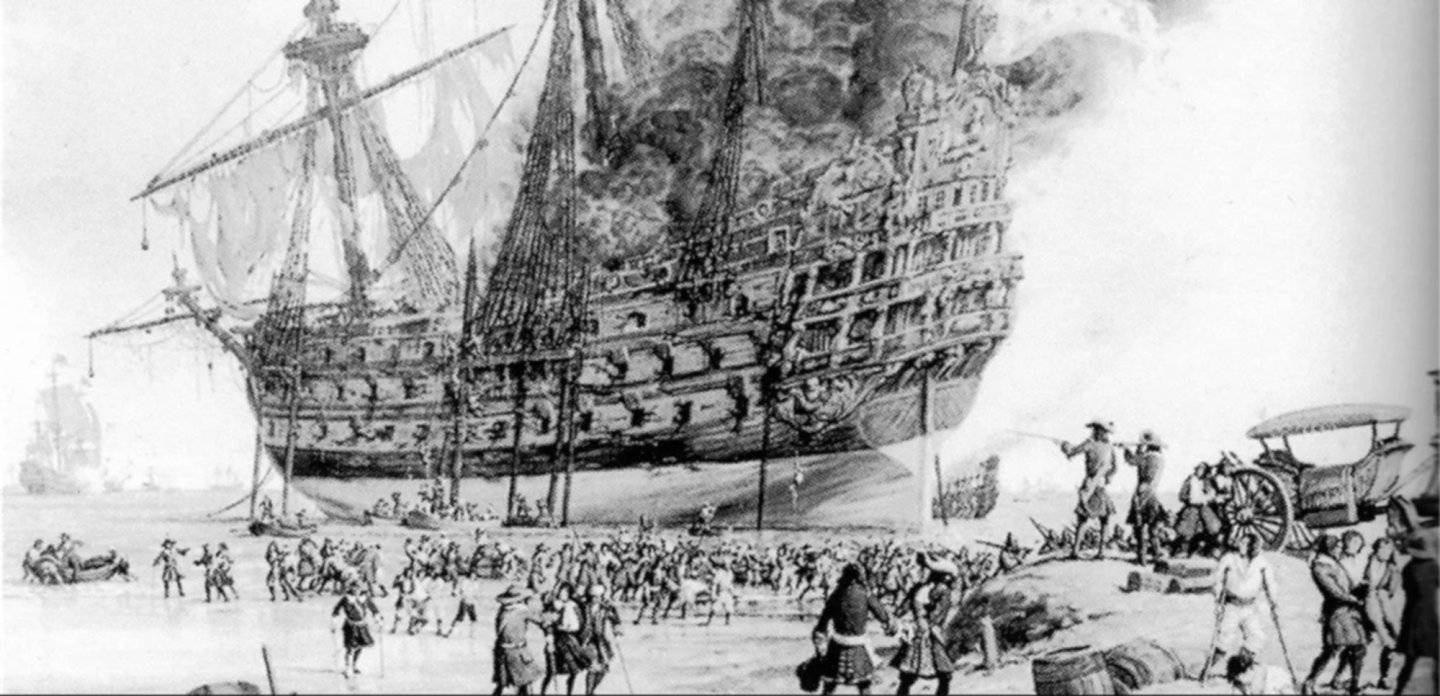

Two different ways of visualizing history: Above, "La Hougue" (1692), painted by a contemporary, Adriaen van Diest (1655-1704). And here's ... "La Hougue," by Benjamin West (1738–1820), painted almost a century later. All things considered, give me a good Dutch marine artist any day. The subject is the British attack in which the first Soleil Royal was burnt to charcoal. I think it's a good illustration (pun intended) of how, when reading about historical events, the focus of the narrative changes over time—from what was more or less news reporting soon after the incident, to breathless tales of jingoist heroism in the decades afterward. It makes researching Baroque marine adventures both entertaining and frustrating. But we were talking about chains and channels ... Being a novice at building large sailing ship models, I was stumped for a long time about how to make chains. Here's how they looked in one of my main references, Jean Boudriot's The Three-decker of the Chevalier de Tourville: Unfortunately, I had mounted my channels and installed all my shrouds BEFORE worrying about chains. In hindsight, I should have made the chains and attached them to the strops of the lower shroud deadeyes before tying on the shrouds. Hindsight is a wonderful thing. I was now faced with making the long chain loop (and the lower loop with the mounts) and somehow attaching it to the lower deadeyes. Bending and soldering loops of wire was contemplated, but I thought it was a terrible idea to bring a hot soldering iron anywhere near my styrene model. I finished the shrouds soon after the start of the year. Another couple months were spent finishing the standing rigging while I wondered how to do the chains. Another couple months went by devoted to another hobby project. I got re-inspired to tackle the chains by reading Marc LaGuardia's (Hubac's Historian) ever-helpful build log and finding out he made his large chains out of thread, tied with surreptitious knots. Now that was an idea to emulate! Or so I thought. My model had sat on a high shelf for several months. I took it down and started examining it to make plans for the chains... but something else was immediately apparent and troubling. My starboard main channel had a noticeable bow in it, the center a few scale feet higher than the ends. The channels had been epoxied to brass posts for (I thought) durability, but apparently the tension from the shrouds had popped the epoxy joints in the middle. This was doubleplus ungood. My port-side main channels were bowing too, though not as bad. I managed to (more or less) level out the main channels again with epoxy and wire-tie reinforcements, but thoughts of using thread for chains went out the window. My chains were not going to be window dressing. They were going to have to be functional. I didn't know if the remaining glue joints were going to pop with age. This decision cast the die. Each long chain was going to have to be 24-gauge soft steel wire, measured and bent to length. No shortcuts. I had a package of brass eyes, around the right size for the lower chain loops. Their posts got bent to 45 degrees and fit— sans glue— into holes drilled on the upper edge of the upper middle wale. The chain mounts were assembled from black styrene sheet, small washers I had on hand, and Tichy NBW castings, also on hand. The mounts were painted black and glued up against the bottoms of the brass eyes. I used a pair of dividers and carefully measured the distance between the strap loops on the channel deadeyes and the brass eyes, then bent the big chains to match. Each was open at one end, with the two wire ends overlapping. I took out each brass eye (not yet glued, remember), attached the big loop, then held the open end open enough to fit through the deadeye strop. With the chain complete, I glued the brass eye into its hole. I think I got the large loop right-sized the first time maybe 30% of the time. With everything painted black, I hoped the open ends of the large loop wouldn't be noticeable. From a foot or more of distance, I was right. I still don't know what the rings mounted on the plank between the middle wales were used for. There was one for every chain, plus a few extra, spaced out along the ship. I made them with some tiny styrene eyes from Tichy and rings made from stretched sprue. They should be painted black but I'm trying to rationalize leaving them light-colored. Before putting on the chains, I figured this was the time to mount the gunport doors. I had them finished and painted for a year, waiting for this opportunity. The shells and fleur-de-lis on the interiors were both brass and leftover castings from the upper decks. The ropes were more soft steel wire. It took about five or six evenings to do each side. But—chains! Port and starboard aren't symmetrical. Never read where they had to be. At any rate, only one side at a time can be seen, so pffffft. The mizzen chains are thread. Not much tension from shrouds there. Marc's idea got used after all. Now I can go on to mounting yards and sails. And reading more—trying to put together a good narrative for the battles of Barfleur and La Hougue. By the way, I really, really hate that Benjamin West painting at the start of this post. In this country it is good to lampoon a marine artist from time to time, in order to encourage the others. ("Dans ce pays là, il est bon se moquer de temps en temps un artiste marin pour encourager les autres.") De Tourville did not say that. Stay dry. JO

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

One handy source is HISmodel, https://www.hismodel.com/. They have complete accessory sets for the Heller Soleil Royal, including Amati rope sets. This is a good place to start. Check around the internet for other model ship suppliers. The ropes you need will depend on how many changes and re-dos you decide to make with your rigging.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

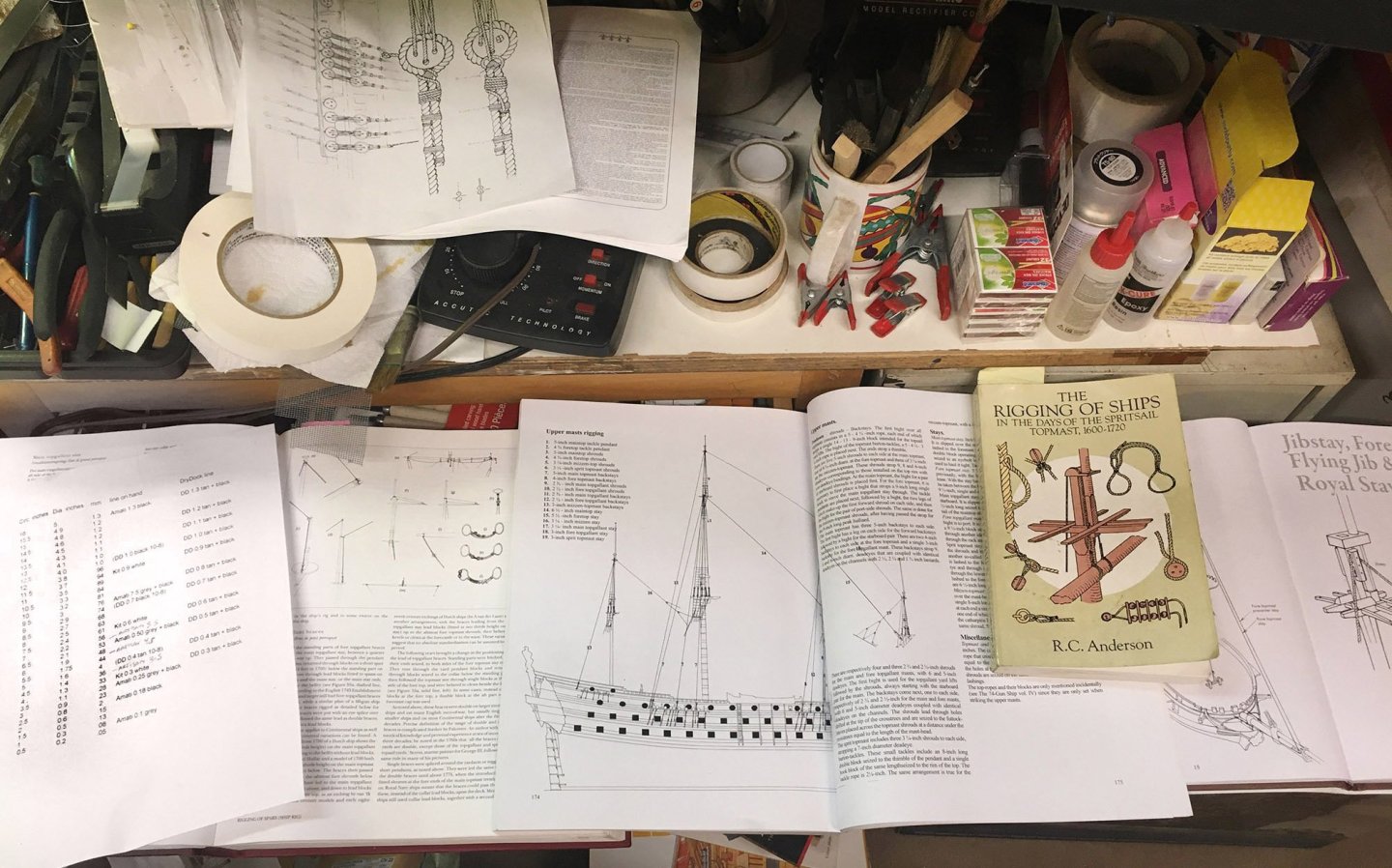

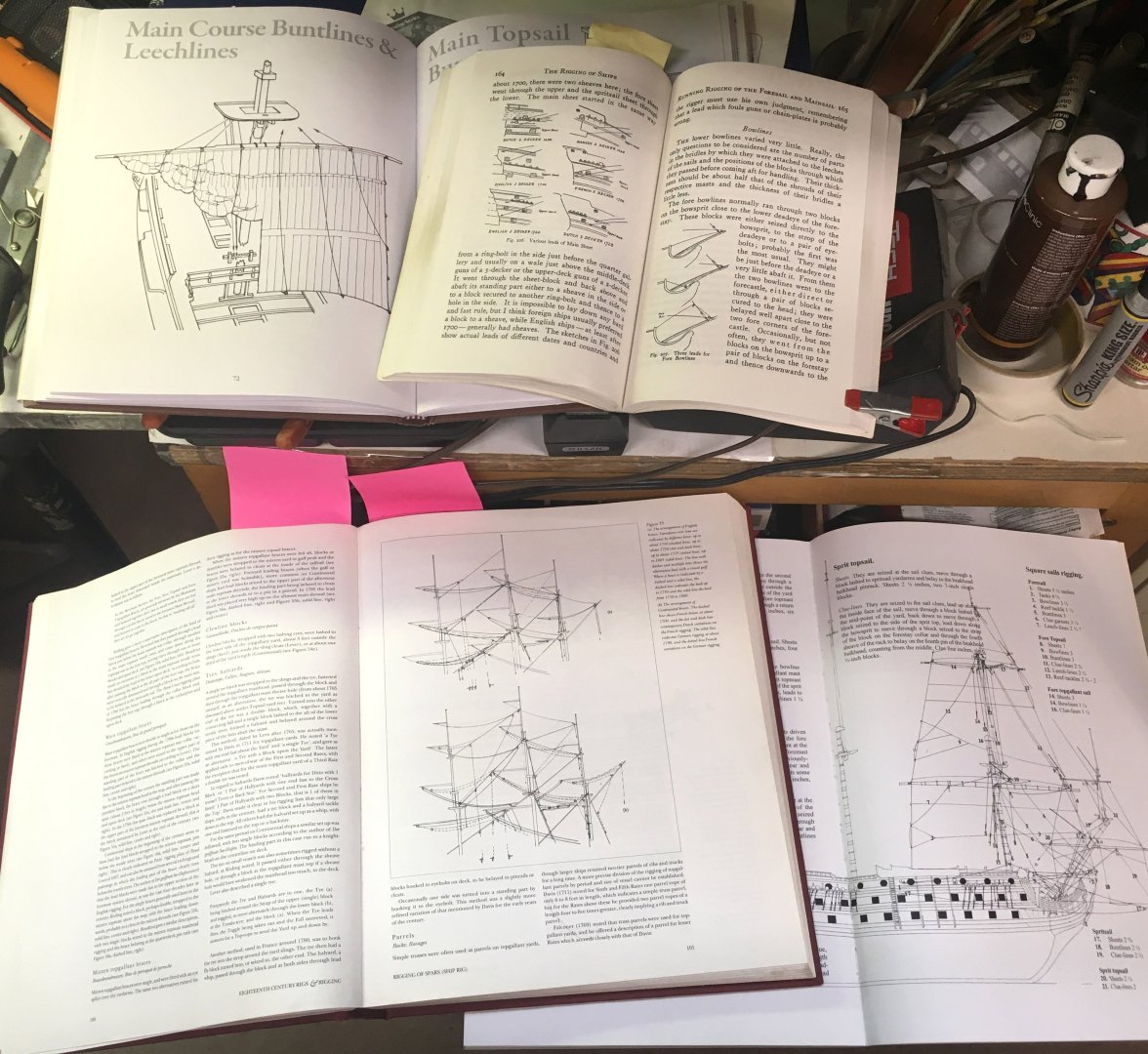

Hello, shipwrights. Those of you that are left. It's long past time for an update. I think my last one was in November. The hull of my Heller 1:100 Soliel was mostly complete last fall. With the advice of other modelers I respected, I had decided to forego the kit's rigging instructions, which I judged to be too impenetrable anyway, and just go line-by-line using three sources of reference: R.C. Anderson's The Rigging of Ships in the Days of the Spritsail Topmast, 1600–1720, Karl Heinz Marquardt's Eighteenth-Century Rigs & Rigging, Jean Boudriot's The Three-Decker of the Chevalier De Tourville, and Lennarth Petersson's Rigging Period Ship Models, AKA Model Ship Rigging for Dummies—which fit my (lack of) aptitude nicely. The intent was to use these to make a custom rigging diagram and obtain prototypical specs for belaying points, line weights, block sizes, etc. Once past that point, I soon realized that, while the source materials specified what the lines did and where the lines should run, they didn't say much about how and in what order a modeler like me should handle the ropes. I figured—logically, I thought—to begin at the bow and work aft. Simple, right? Oops. Nnnnnnnope. Without writing a boring screed about all my misadventures and re-dos, suffice to say that I learned you had to be much more subtle about this process. Rigging is like a chess game, you have to plan things several moves in advance. My present inclination is that If you're belaying lines behind shrouds and ratlines, DON'T put the shrouds and ratlines on first. A better plan is to take care of things from the masts, outboard. Lines close to the centerline of the ship should be dealt with before anything running to the rails. So, after several months of mistakes and nonsense, I've more or less completed the standing rigging. I intend on completing the chain-plates and building a display stand before coping with the running rigging. I'm going to show photos rather than make lengthy descriptions. There are SO MANY better rigging jobs to be seen on other build logs. If you want a thorough how-to, I commend you to those. Here's the current work area. My foam-core clamshell protection box has done a good job of keeping my clumsy hands from dislodging the artillery. I made an attempt to plan ahead. Bought the rigging supplies I thought I needed and organized everything with labels. Painted a lot of rope and sorted it according to size, with the sizes written on the spools. I felt like my dog, with her well-curated collection of tennis balls. Prepared the lower masts and tops. Since everything else about the kit dimensions was exaggerated, I decided to go with the flow and keep the kit's styrene masts without much modification. They did get turned wooden dowels inside to straighten and stiffen them. The tops got their sides and ribs built up with styrene strips. Too late, I read in Boudriot that masts in this period did not have fish, unless the masts were damaged in battle. So—oops again—my masts have fish. I decided my model had to represent the Soliel as it was refit AFTER the Battle of Malaga, not BEFORE, as planned. Sigh. I figured the spritsail topmast was a good place to try tying shrouds and ratlines. I didn't like the result. The thread was too stiff. ANYBODY KNOW HOW TO SOFTEN THREAD AND MAKE IT DROOP? The kit had the main and fore channels placed one deck too high. As shown in the Jerome Helyot drawing above, the channels on the prototype were placed BELOW the upper gun deck. No problem, right? Just make the shrouds longer, right? But the kit had very little tumblehome. In order to keep the longer shrouds from hitting the rails, you had to make sure the new channels were wide enough. Also, you had to place the shrouds so that they didn't come down right over a gunport. I made diagrams, in the process realizing that my deadeyes were too big. Got new ones. I ended up using the kit's channels, widening them with sheet styrene where needed. Filled in the slots for the kit's chain deadeyes and filed new ones at the channels' edges. This was closer to prototype practice anyway. The deadeyes got stained a uniform dark color. This began about three months of frustration trying different ways to make the lower mast shrouds and ratlines. I tried sewing them on because I had used that technique on another ship model years ago. Tried it three times. Disliked each try. Ran out of thread the size needed for foremast shrouds. Got more. Re-used deadeyes. Sobered up from the pity party. Tried again. Wash, rinse repeat. I began to wonder if I was ever going to finish. I thought about different things I could do with this model. Like burn it. But I finally settled on doing shrouds the old, time-consuming, uninventive way. Tied every knot. Accepted that the lines weren't going to droop the way I wanted. The new channels were mounted on brass posts with epoxy for strength. Even then, when tightening the shrouds later on, one popped loose and I had to perform a do-over. I don't know what would have happened if I had just tried gluing on the channels styrene to styrene. There was a lot of running rigging that was supposed to belay behind the shrouds. I decided that I'd better take care of those lines before the shrouds went on. To this day, I don't know if it was a good decision or not. I'll find out when I tackle the running rigging. For the time being, I tell people that my model has grown a beard and joined a Texas hard-rock band. Finally, I had shrouds and ratlines on the foremast. Managed to repeat the process on the other two lower masts without much further nonsense. The upper masts went up in a surprisingly short amount of time—within a month or so. This was very encouraging. I assembled them on my workbench and simply tied the deadeye lanyards after they were up. Then came stays, backstays, bobstay, tackles, futtocks, crowsfeet—all the stuff that seems easy after fighting for months with the shrouds. One thing I forgot to mention is all the touchup paint on the ropes. I tried to soften the contrast between the tarred and un-tarred lines. It produced a nice variety of shades to the rope. Not being much of a tall ships sailor, I don't know how realistic that is, but to my eye, it helps the job look authentic. So—yeah. There's the standing rigging. By the time you're reading this post (it took me since April to decide to upload it), I'll hopefully be busy trying to figure out the best technique for making chain plates. I'll post more when I make progress with the running rigging. My hope is to have a finished model by the end of the year. I had originally planned for this project to take a year. I think now I'll be fortunate if it only takes two. I'm still optimistic I'll have a mantlepiece-worthy model when I finish. Thanks much for looking in. Gardez la poudre au sec. Or else.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Are you being logical again, Marc? This has to stop... Seriously, I've regretted not taking your path and not making and installing chain plates at the same time I attached the stropped deadeyes to the channels. Now I'm stuck retrofitting the chains—somehow without soldering, since soldering elements + styrene = tragedy. I think I'll put off my own wire-bending until your next few posts so I can see how my betters do it.

- 2,623 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal by Hubac's Historian - Heller - An Extensive Modification and Partial Scratch-Build

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal by Hubac's Historian - Heller - An Extensive Modification and Partial Scratch-Build

-

Yeah, Hitchhiker's, Marc. I suppose that dates me somewhat. I spent the day installing mainmast tackles and mulling over the problem you highlighted. I finally hit on a good rationalization: my Soleil has fish because the model represents the ship as it appeared some time after the Battle of Malaga instead of before, as I previously intended. The masts had battle damage repaired, but remained weakened, hence the fish. Actually, having repaired battle damage justifies a whole host of deviations from the Boudroit norm, so I can use the same excuse next time I get into trouble.

- 2,623 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal by Hubac's Historian - Heller - An Extensive Modification and Partial Scratch-Build

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal by Hubac's Historian - Heller - An Extensive Modification and Partial Scratch-Build

-

Wow. Good job on correcting the masts. Boudroit says specifically in his section on masts and fittings that there were no fish, except—"The use of fish was known, but used as pieces of timber intended to correct the least weakness in resistance of a mast that could have been cracked but not broken." (Book's not-terribly-great English translation.) So—live and learn. In my case, I learned too late. I didn't get Boudroit's book until after my lower masts were already installed, and so I'm going to live with them, fish and all. So long, and thanks for all the fish.* (*dated reference.)

- 2,623 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

John Ott reacted to a post in a topic:

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - FINISHED - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

-

Thank you, Kirill. It looks like all my lines may need another coat of stain. It's better to find that out now before any are up.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Johnny. Thanks for the input. I never know what to make of the rigging on historic models. They've either aged several centuries themselves or the ropes have been replaced in restoration. Either way, the lines probably aren't the original color. And I don't know how close they were to reality in the first place. For my model, maybe I should just stain the ratlines dark brown.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Keith. I don't know if it's visible in the photos, but I stain my "light" lines to look (at least to my eye) like old hemp rope, kind of a greyish brown.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Johnny. So far, I think I'll be using light-colored lines. I read somewhere that the deadeye lanyards weren't tarred because they frequently needed adjusting, and the ratlines don't seem to be tarred on OPM (other people's models). Being a newbie, I learn a lot from OPM. If I'm wrong—there's always black paint.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

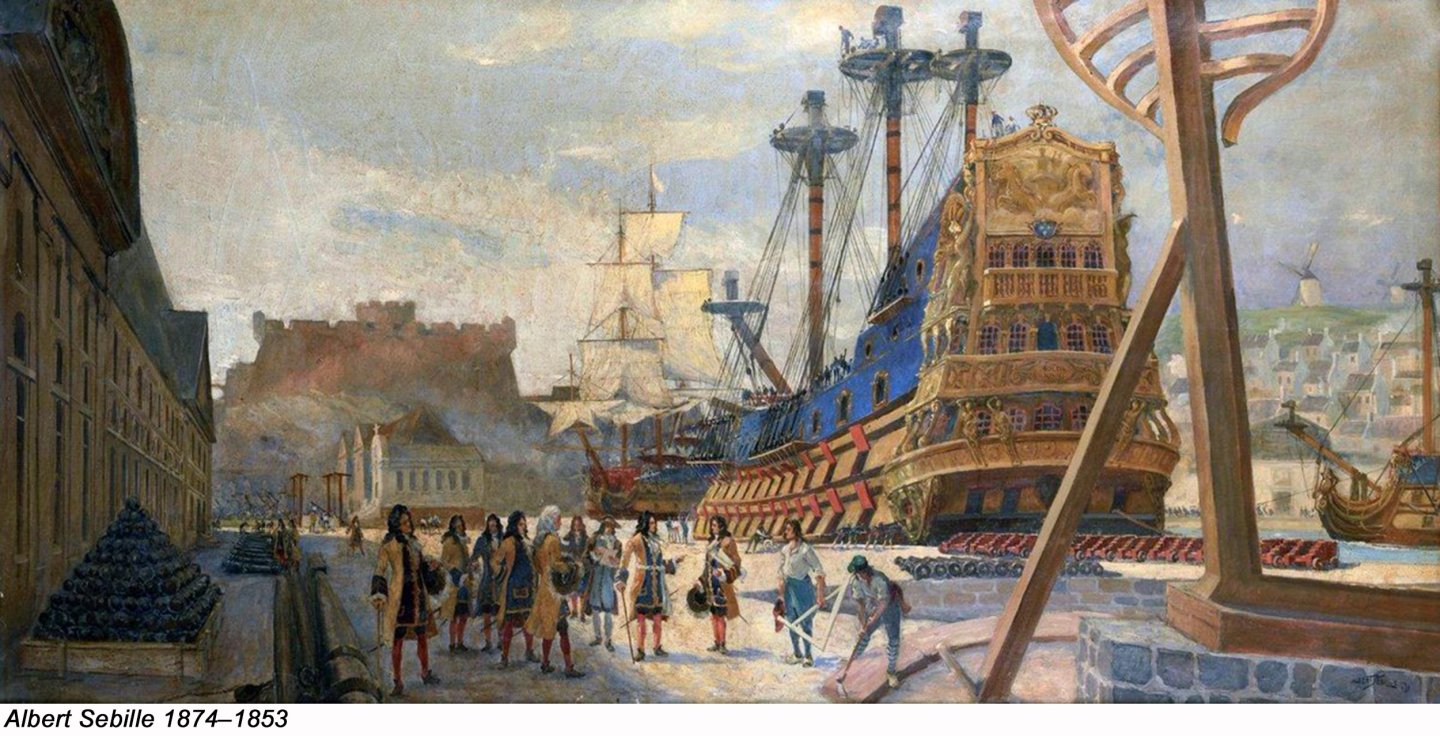

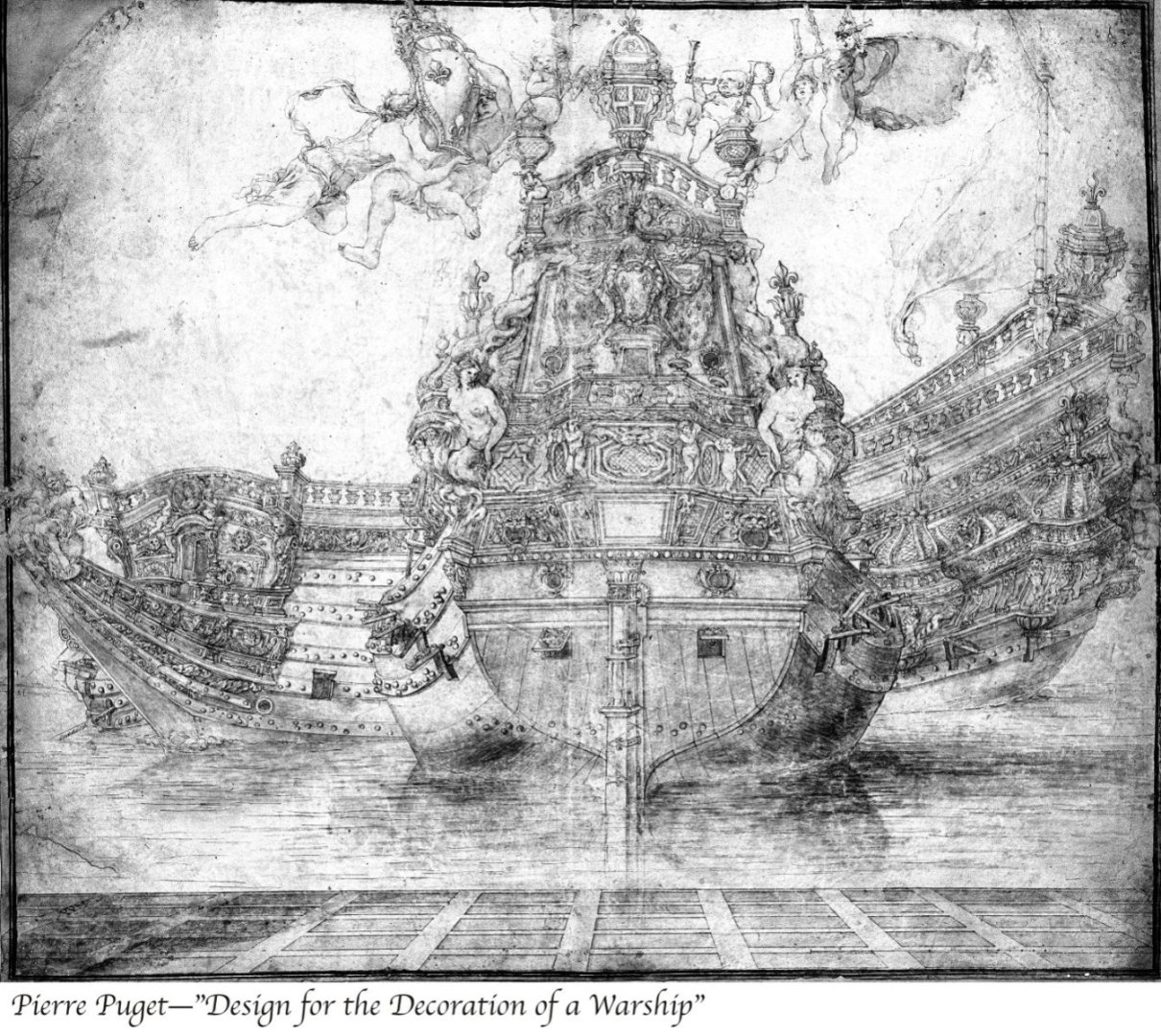

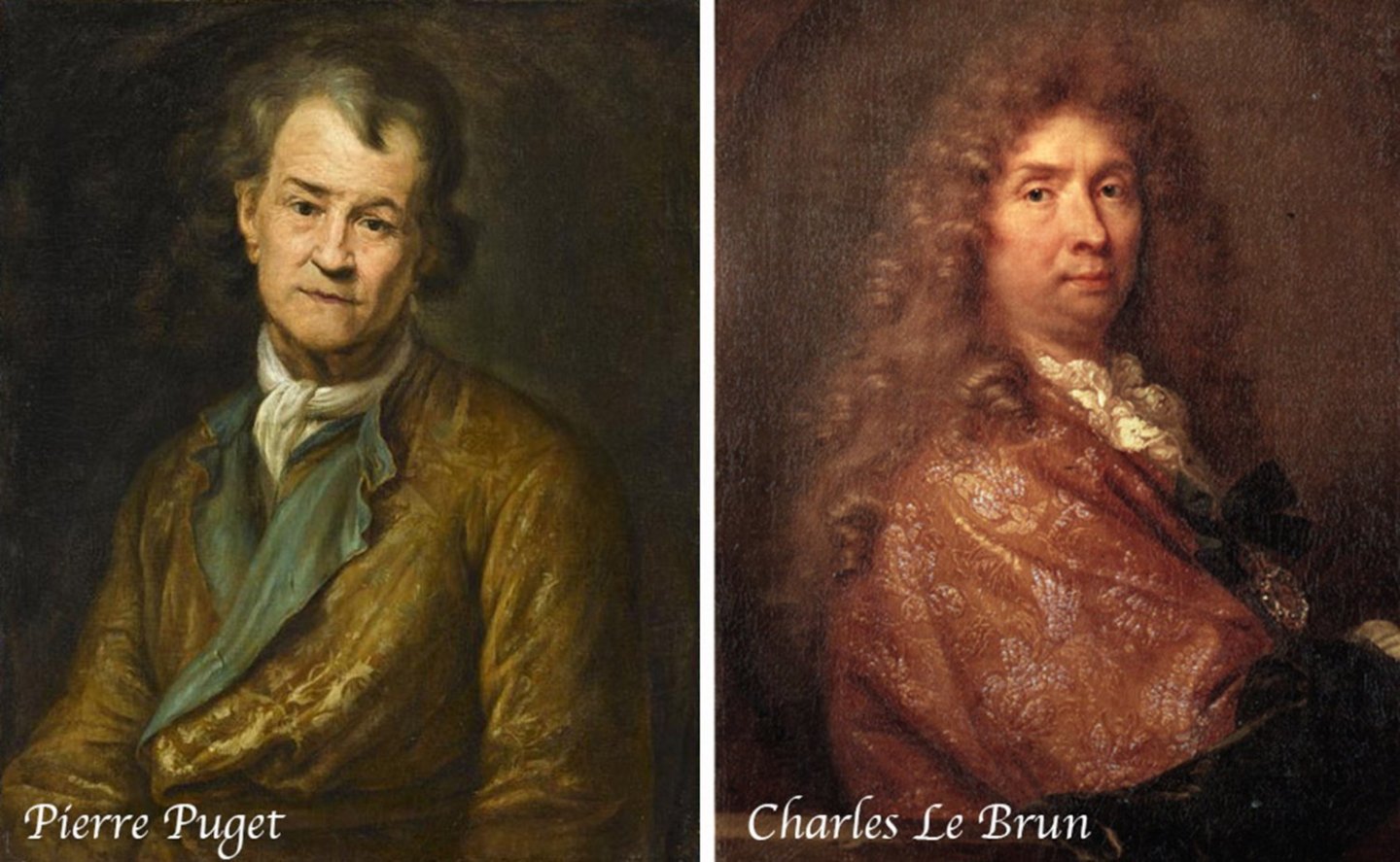

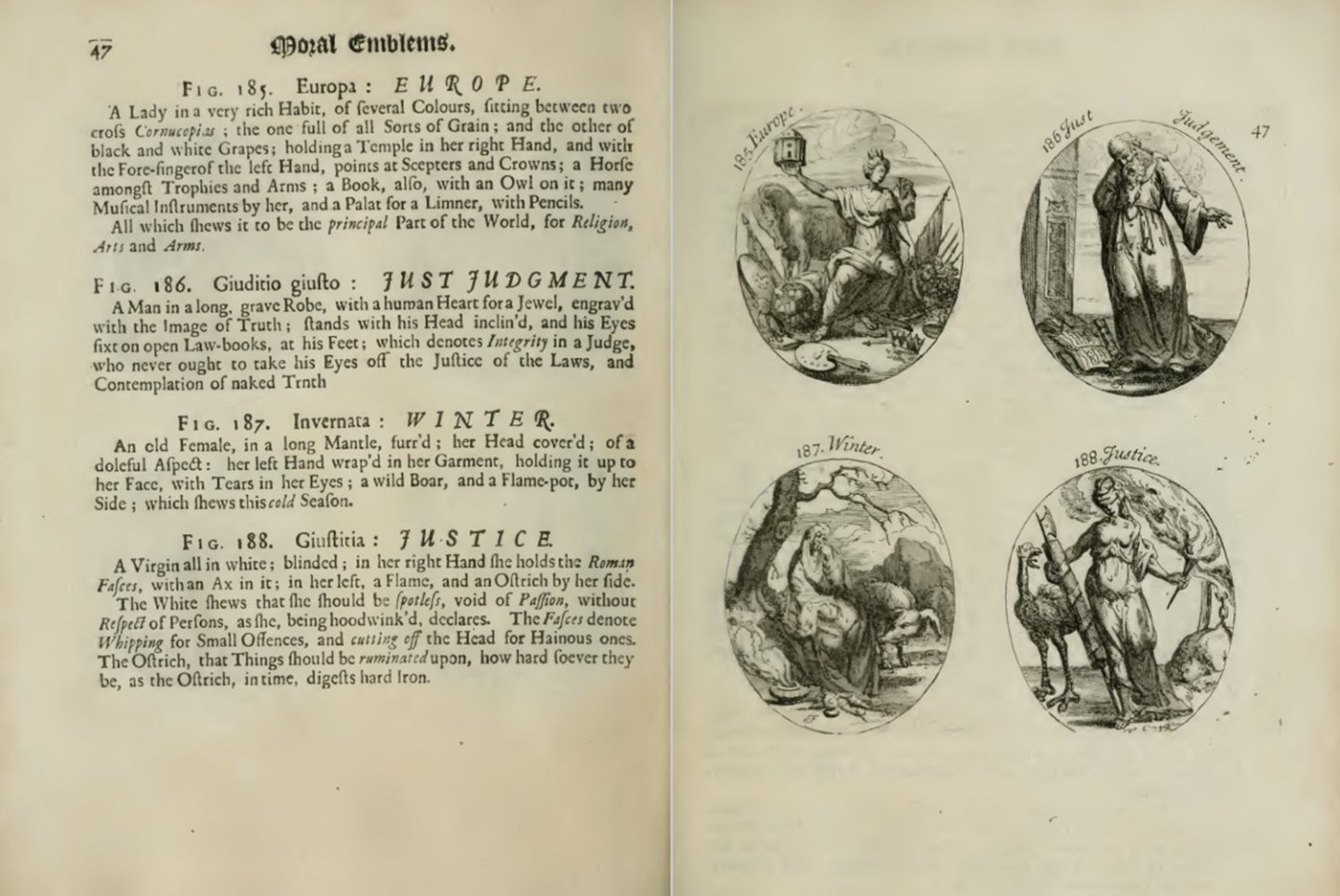

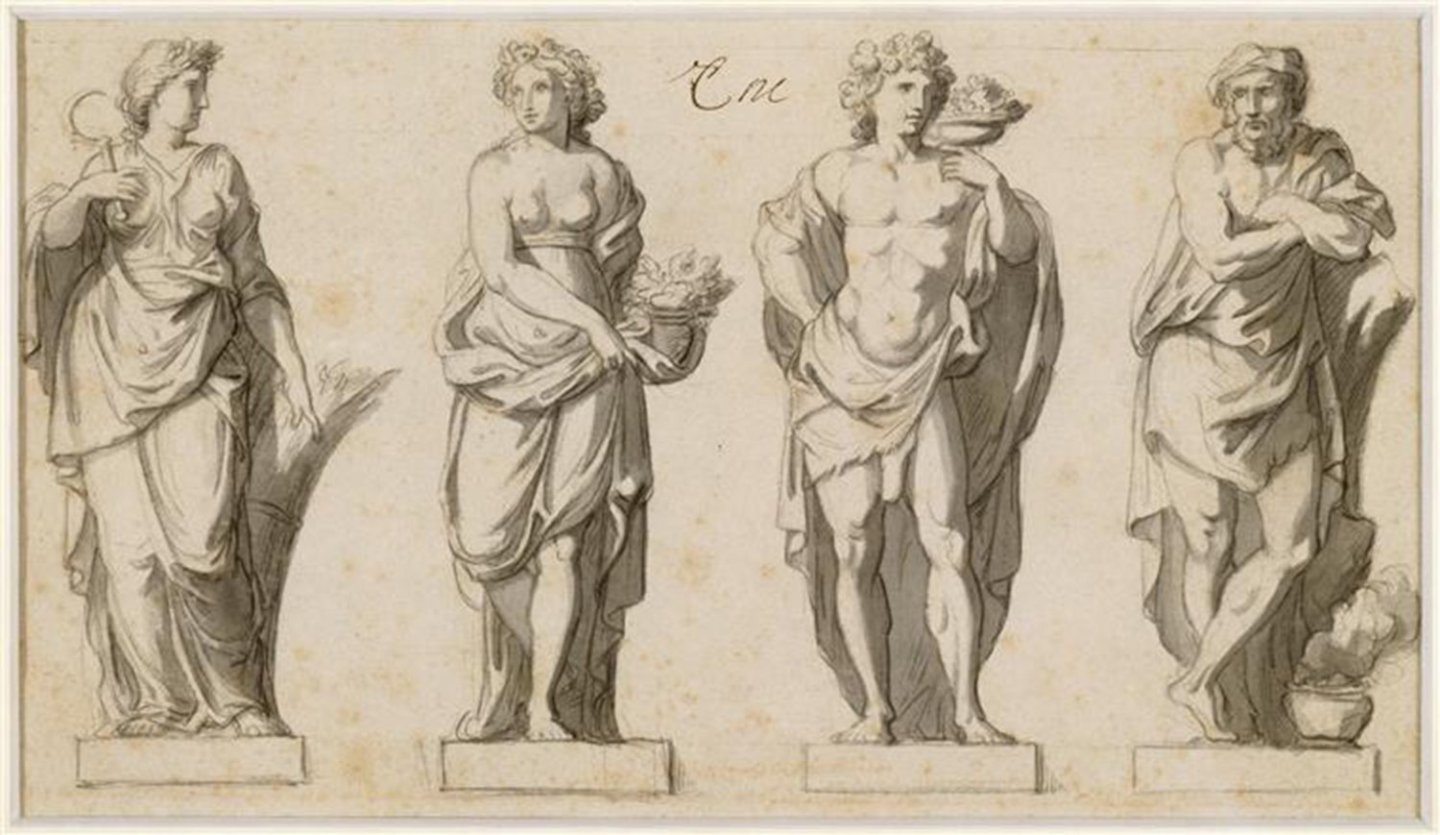

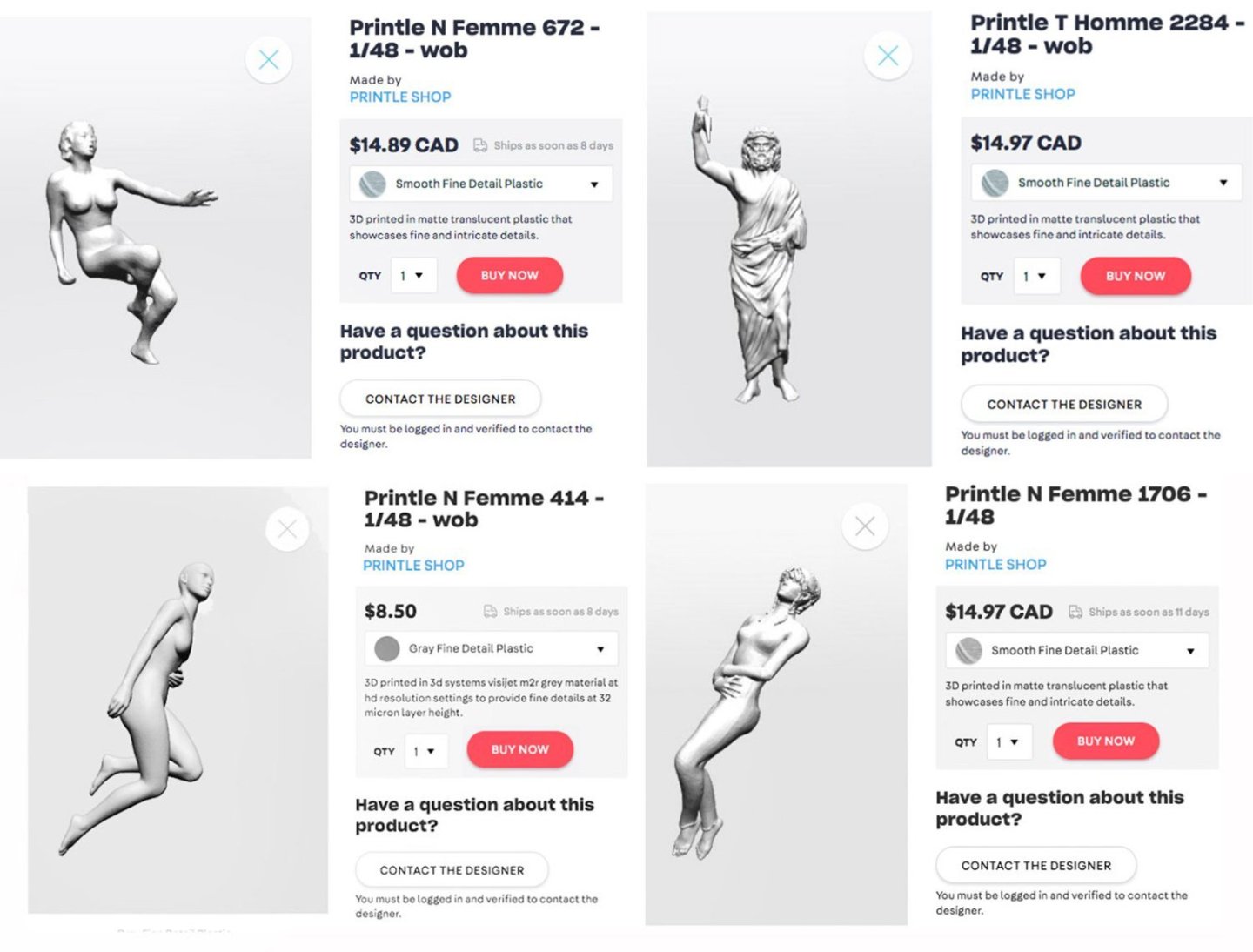

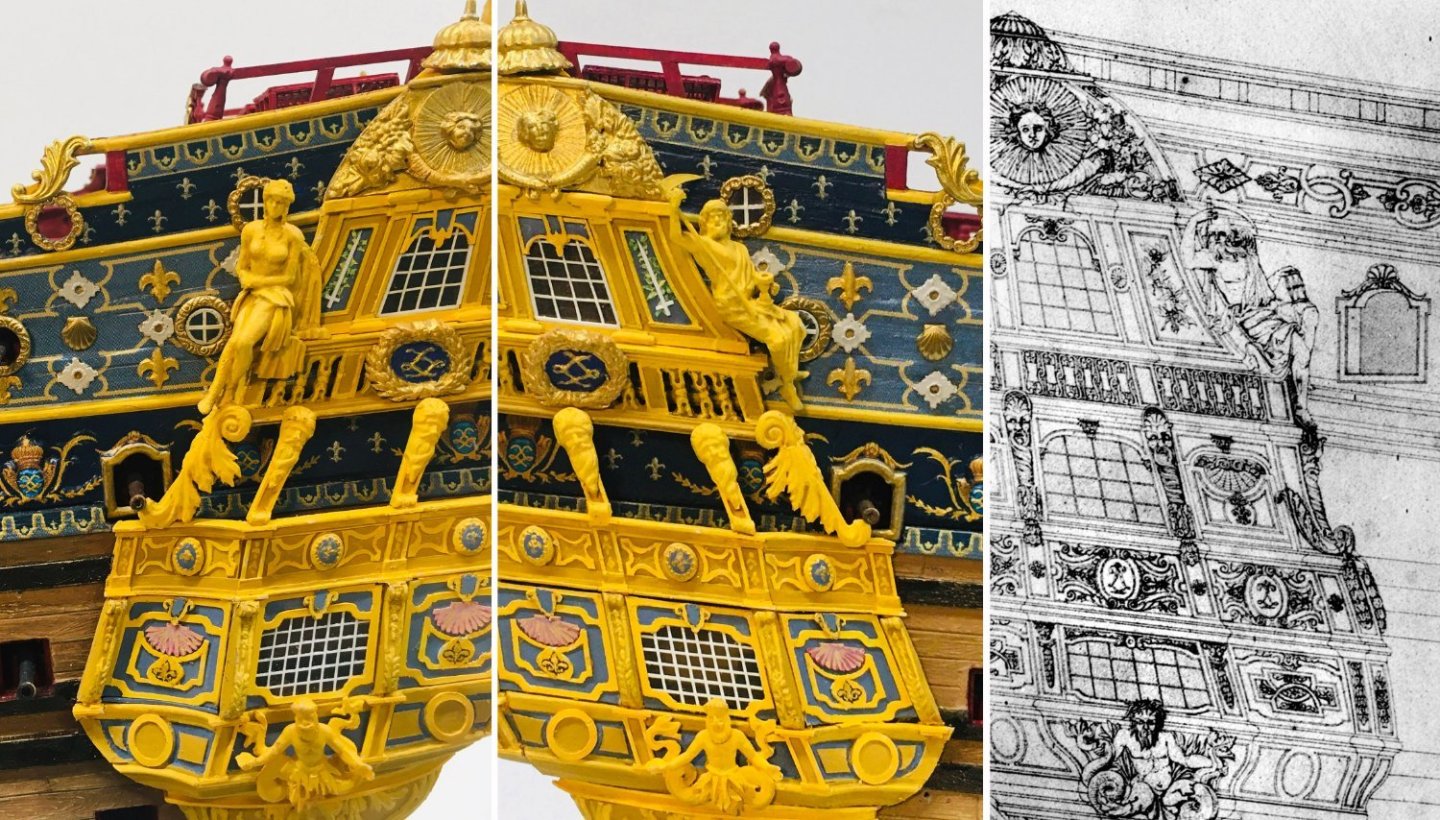

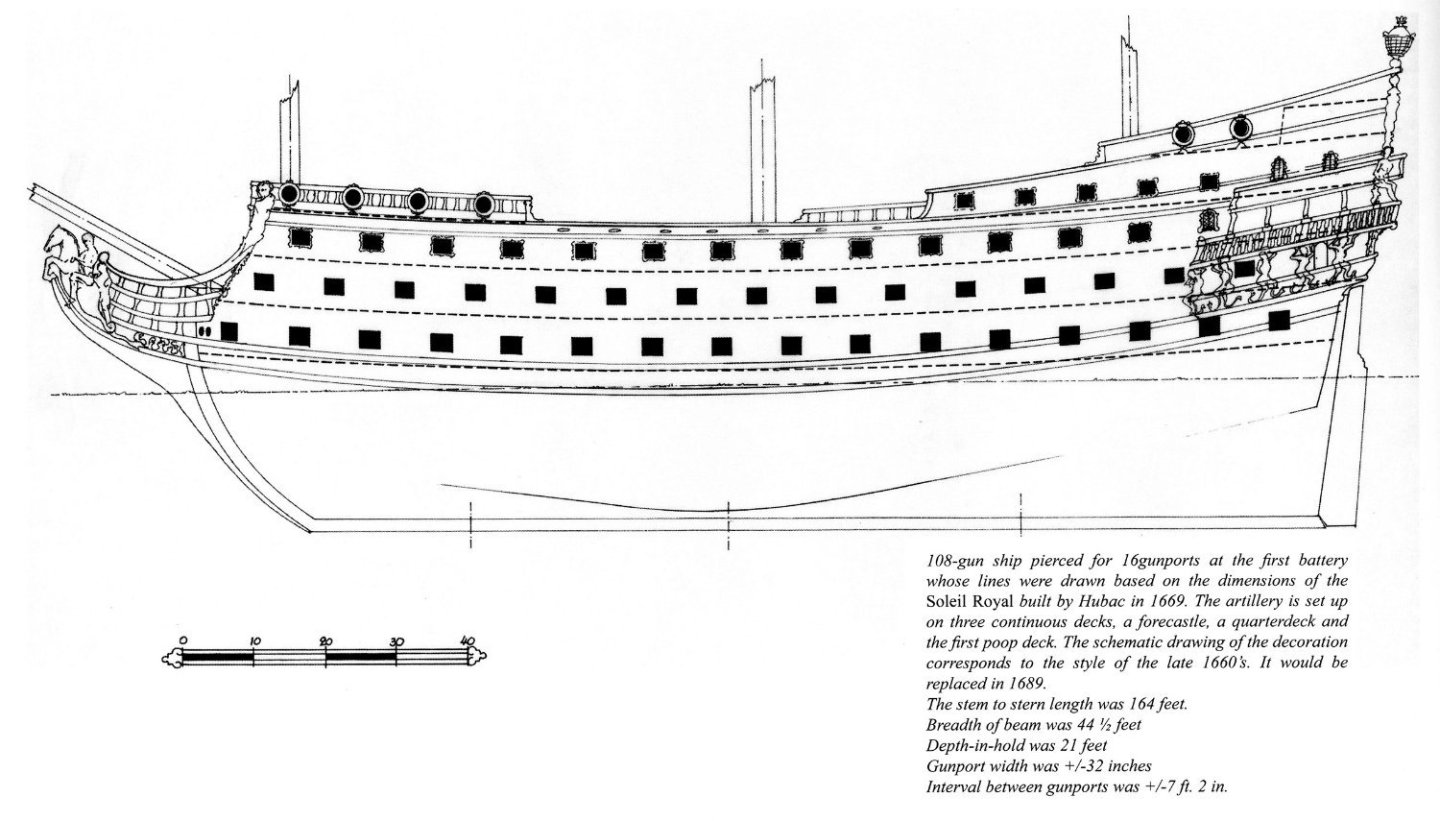

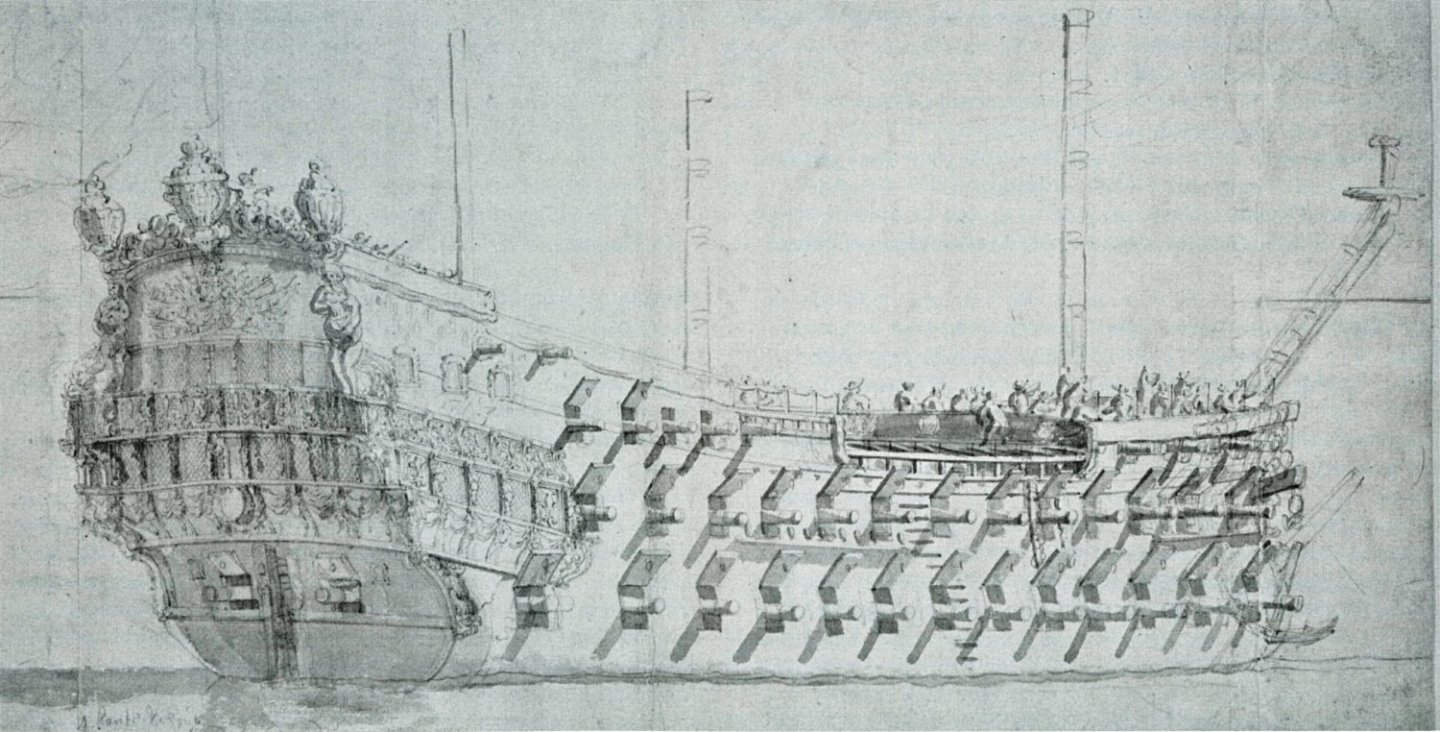

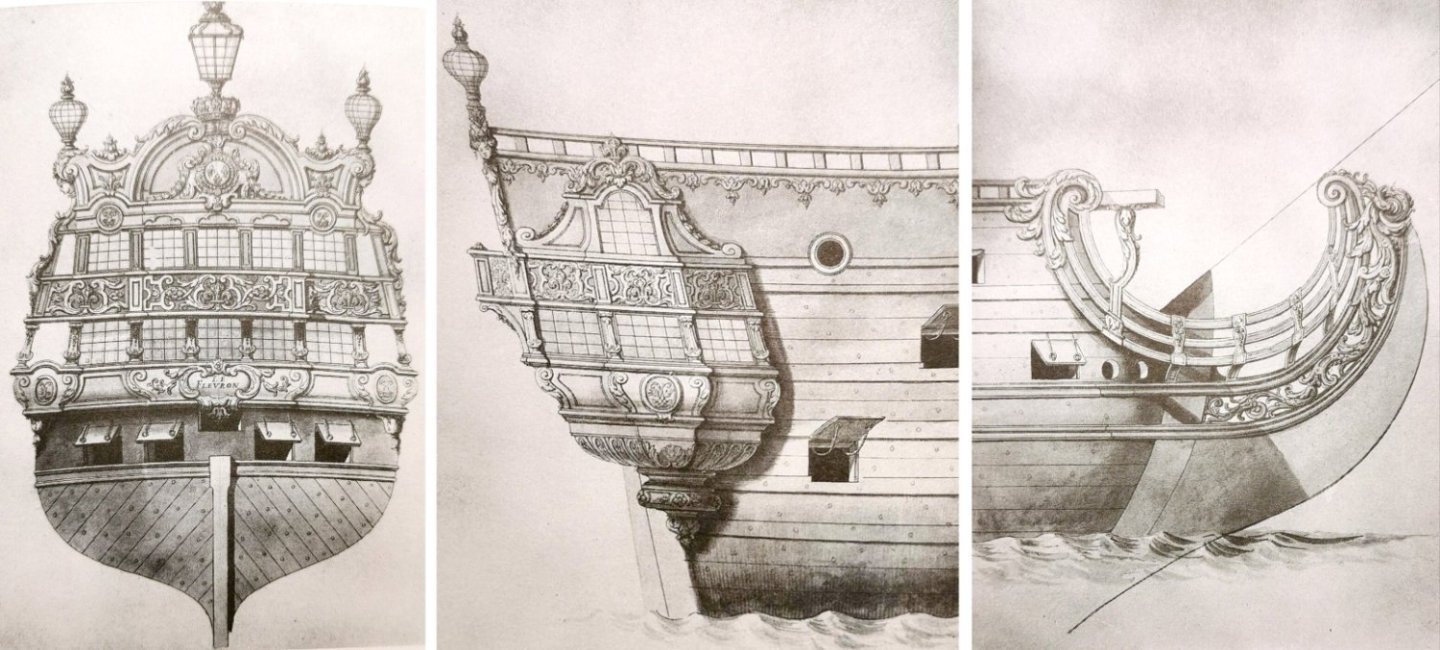

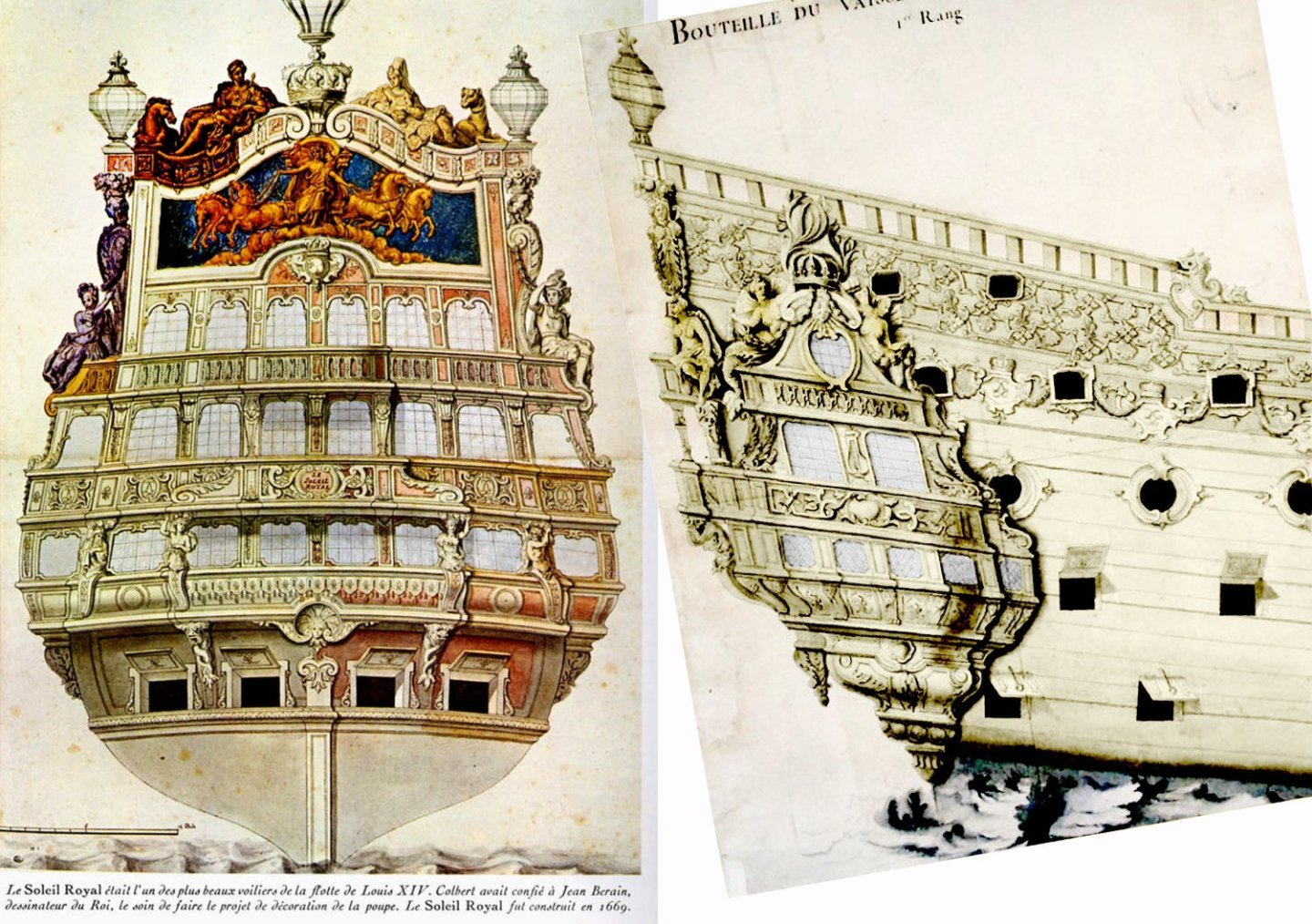

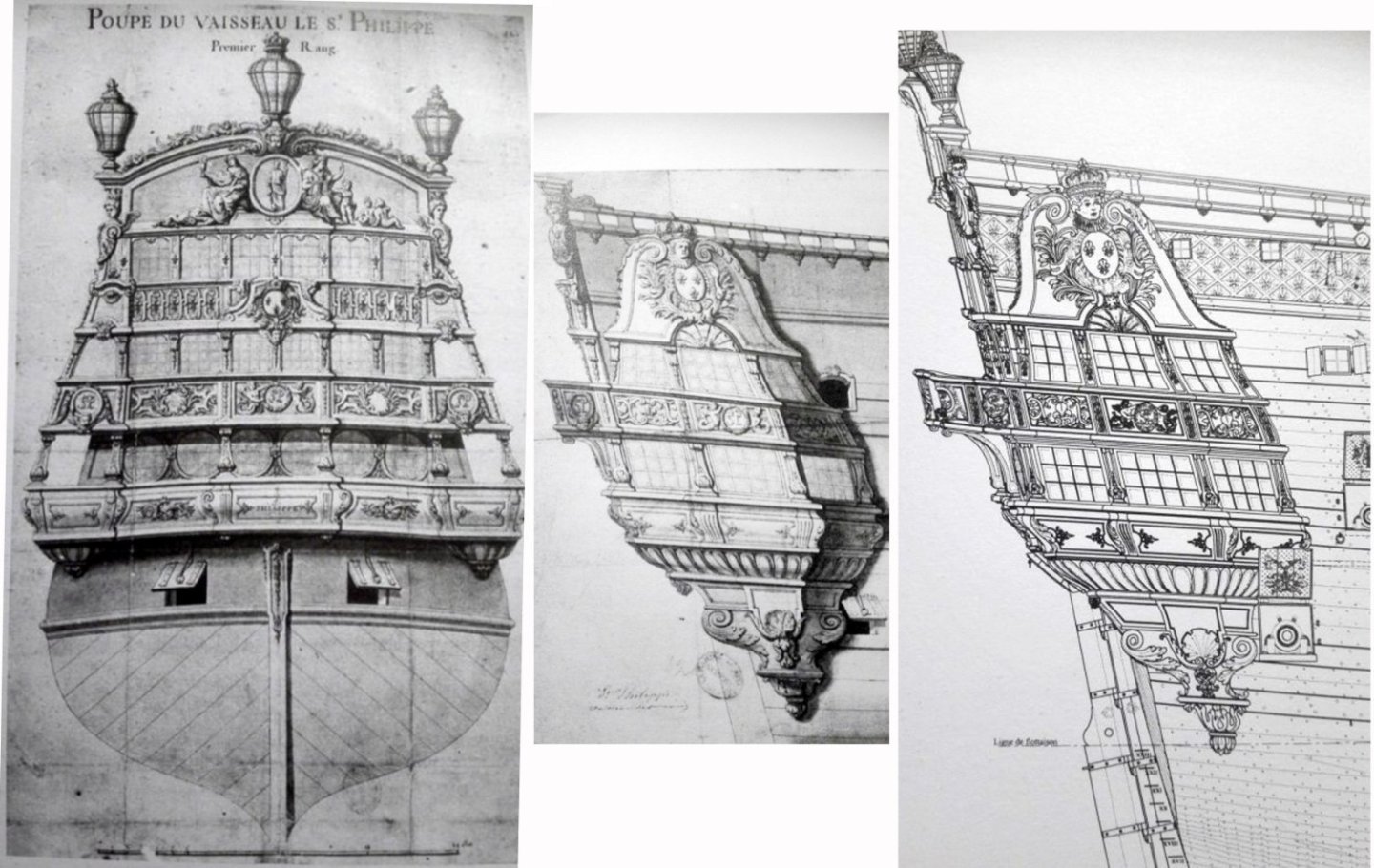

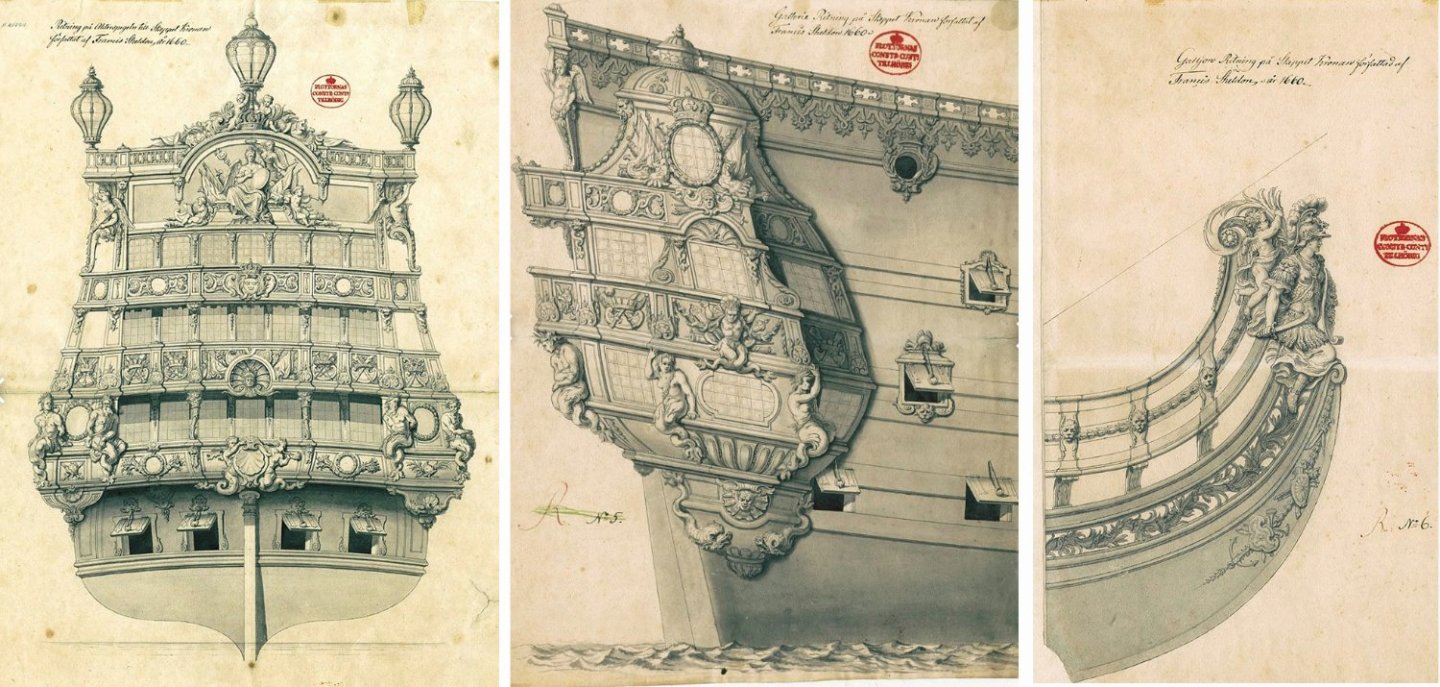

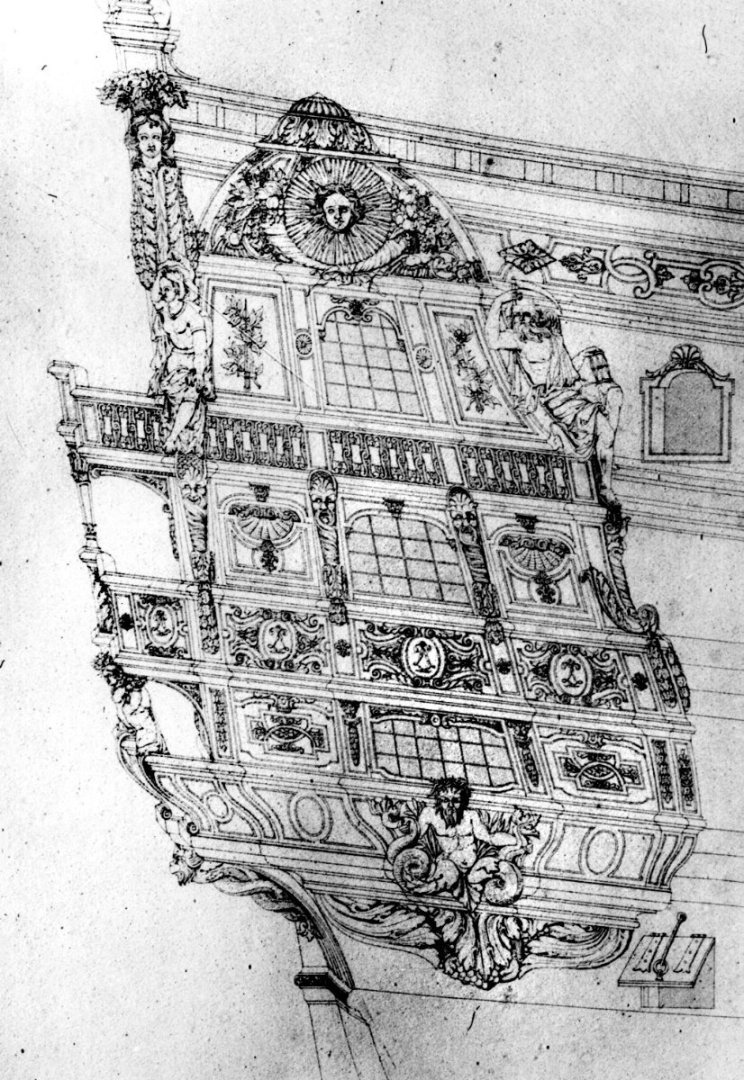

James A. Flood By the mid-1600s, it was taken for granted that warships had to look awesome. Decorations were no longer being painted or tacked on, but were being incorporated into the ship’s architecture. Louis XIV and his ministers were obsessed with having French ships look bigger and richer than their British counterparts. They hired the best artists in France to design statues, friezes, and decorative woodwork. Louis’s chief minion, Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, engaged artist Charles Le Brun to design statuary for Versailles, and when Colbert was given the additional position of Minister of Marine in 1669, he made Le Brun responsible for the decoration of the king’s newly-built fleet of ships-of-the-line as well. Le Brun set up sculpture academies in the shipbuilding centers of Brest, Toulon, and Rochefort to train the army of sculptors needed. The task of designing the architecture and decoration for the ships was assigned to the same artists who worked on the palace of Versailles, like Jean Bérain, and they churned out preparatory drawings to be given to the sculptors. The Italian-trained artist Pierre Puget was appointed head sculptor at the shipyard in Toulon after notable success decorating France’s Mediterranean galley fleet. His fanciful statues and designs for the new warships were inspired by Italian theater sets. This was an age when popular stage productions were growing more elaborate. Opera had been newly invented. Music specifically for the stage was being composed. The palace of Versailles had its own theater and the king and his aristocrats took part in the productions. Puget’s theatrical shipboard tableaux were immediately popular and widely copied. They looked a lot like opera backdrops. Two of Puget's ship designs. You kind of expect someone to come out on the balcony and start singing . . . . Puget’s sculptures were unquestionably awesome, but were also huge, heavy, and for the most part impractical. His boss, Le Brun, refused several of his designs with the note that they were “very handsome but not at all convenient for ships.” It was because of Puget’s extreme theatricality that Le Brun issued an order in 1673 indicating that sterns would not be allowed to carry figures so big that they affected the stability of the ship. Puget resigned in 1679, but one of the 1689 Bérain drawings of the Soleil Royal has the scribbled notation that it was made “apres Pierre Puget.” This caused at least one 19th-century French ship historian to attribute all of the Soleil Royal’s sculptures to Puget, in spite of evidence to the contrary. (Puget worked in Toulon; the Soleil Royal was built in Brest.) Instead of Puget, it’s fairly easy to connect the carvings on the Soleil Royal to the work of Charles Le Brun. Most of the figures turn out to be adaptations of Le Brun’s sculptural work at Versailles, especially his statues designed for the Versailles gardens in the grand commande (great commission) of 1674. The statues on the ship were originally made with Puget’s grandiosity in mind, but were later “adjusted” in size—in some cases replaced, in others, hollowed out—to reduce the weight and improve the ship’s stability. In a further effort to improve the ship’s handling, several of the larger statues were unshipped by Admiral De Tourville and left behind when the flagship went to war. These carvings were available for reuse on the Soleil Royal II, built in 1693. The new ship’s builder, Étienne Hubac, had been responsible for rebuilding the Soleil Royal I in 1689 and still had all of les garabits (templates and patterns) for the revised statuary. And so (we suppose), the second ship was decorated much like the first. There’s a weird thing about the symbolism and statuary on the Soleil Royal— well, weird for 1693— and that’s the ship’s total lack of Christian motifs and symbols. We’re used to thinking of the Baroque era as a religious age, one dominated by cardinals and cathedrals, sacred relics, bible-inspired art, witch-finders, and endless Catholic-Protestant wars. The hierarchy of the church was at the top of the social heap and kings wielded their power by divine right. The open-minded period of the Enlightenment was over half a century in the future. But without being terribly anti-clerical about it, along came Louis XIV with his aristocrats, retainers, bureaucrats, and artisans, and overt Christianity suddenly took a back seat to a revived interest in pre-Christian classical paganism. Instead of Christ, angels, and saints, the denizens of Versailles were more fascinated by gods, demigods, and caesars. In paintings, Louis had himself and his family portrayed as characters out of classical mythology. Louis and his over-extended family . . . . just another day of lounging around like Olympian gods. I’m sure the whys and hows are the subject of numerous books I’ll never get around to reading. For the time being, though, we can contemplate how all this influenced the decorations on Louis’s warships. What was in the art on the Soleil Royal? What did it represent? What did it all mean? Why was it there? First point—the art was meant to be symbolism. It consisted of elements meant to be read for their symbolic value by a largely unlettered population. Everybody back then was used to reading symbolism. It was all over their churches. Even if they couldn’t read, the populace knew all the bible stories by looking at the statuary, paintings, icons, altarpieces, carvings, and stained-glass that decorated their houses of worship. Every saint has his/her symbols for identification. Every condition or attribute had its own visual elements for storytelling purposes. The carvings on the Soleil Royal didn’t use Christian iconography, but the same principles applied. Artists like Le Brun even had textbooks of common iconography they could consult, like Caesar Ripa’s Iconologia, which described in detail what visual attributes went with which allegorical or historic figures. Caesar Ripa's Iconologia. Next point—this was Louis’s ship. Louis XIV was an absolute monarch, and when he famously proclaimed “L’État, c’est moi,” he meant it. The ships as well as the state were his, and the most important (gilded) artistic elements on the ship proclaimed his ownership. First, there was his Bourbon coat-of-arms on the bow and the stern, Azure, three fleurs-de-lys or—three gold fleur d’lis on a blue field, topped by a crown to indicate royalty. The fleurs would be repeated many places on the ship. On my model, white, open-faced fleurs (lilies seen from the top) are used on the quarter deck/forecastle level. There was also the king’s monogram, two intertwined, mirrored “L”s, also topped with a crown and surrounded by acanthus stems and chains of bellflowers, on the length of the upper gundeck. On the quarter galleries, the monograms are surrounded with a classical-antiquity-inspired laurel crown. You couldn’t go ten feet in any direction on this ship without being reminded it was Louis’s. The name itself, “the Royal Sun,” was one of his self-aggrandizing unofficial titles. Whose ship was it again? Louis himself is represented several times. The beaming face of the Sun King surrounded by solar rays appears on the headrail medallions and on the dormers of the quarter galleries—looking out from the four quarters of the ship. These were all elements I chose to paint as if they were gilded on my model. The same devices are always gilded where they appear at Versailles. Right, the face of the Sun King at Versailles, same as on the ship. Louis also starred in the most distinctive piece of décor on the ship—the Apollo solar chariot frieze on the stern-plate. The zodiac frieze above the chariot and the clouds below it show that the tableau is supposed to be occurring in the heavens, far above lowly Earth. Louis, as Apollo, drives the solar chariot on its daily celestial path. He's not carrying the sun. He is the sun. The gold leaf would have blazed in daylight. The frieze was patterned after the Apollo fountain, a major sculptural group by Charles Le Brun in the gardens of Versailles. Louis was supposedly a devout Catholic who did a lot to enhance the power of the church, including expelling all French protestants. I don’t know how he managed to reconcile his devotion with presenting himself as an Olympian god. Charles Le Brun's Apollo fountain at Versailles. Charles Le Brun was responsible for the other sculptural groups on the ship’s stern. He designed four statues for the gardens of Versailles to represent the four seasons. Variations of these serve as pillars between the ship's middle deck and upper deck balconies. Louis was being advertised as literally, a “king for all seasons.” Le Brun's original design drawings for the Four Seasons, Autumn, Spring, Summer, and Winter. The statues were executed by hired sculptors. I don't know where or if the statues survived. They no longer seem to be at Versailles. At the bottoms of the quarter galleries are mermen, two split-tailed tritons from classical mythology. These were often used on French ship décor. Their function was to hail Louis as master of the seas. The ship’s figurehead is a classical winged sea nymph on the back of a sea horse (literally, a mer-horse with a fish tail)—a herald for the procession of royal emblems to follow. Another nautical-themed element was the bevy of scallop shells. The ribs on the scallops represented the sun’s rays, so they worked as one of Louis’s solar symbols as well as a symbol of the sea. Surrounding the stern plate are allegorical figures representing the four continents (as they were known at the time), representing the wide overseas reach of French power. Reclining atop the zodiac frieze above the Apollo chariot are the figures of Europe, port, in classical garb with a horse, and Asia, starboard, in “eastern” dress, a turban, and a camel. On the lower port of the stern-plate is a female figure representing the Americas, in a straw skirt and feather crown. Starboard is the figure of Africa, with a distinct elephant-head headdress. These, too, are variants on Le Brun’s Versailles sculptures. The figures of the Americas and Africa on the Soleil Royal have exactly the same headdresses. This and the Apollo's chariot frieze are the strongest links between the ship's sculpture and Charles Le Brun. Pierre Puget—sorry, nope! Charles Le Brun, the Four Continents. Still on display at Versailles. In the Heller kit, I felt that the two figures on the lower stern-plate corners were too large and not very attractive to boot. I needed a smaller Africa and the Americas. I went looking for other model figures to use. What size was okay? I thought 1/48 (O scale)—about 10–12 feet in 1/100— was about the largest that would be reasonable. After an internet search, I focused on some 3D-printed figures by a company named Printle on the Shapeways.com website. Some were copies of classical statues. Some were female nudes. They were cheap enough; I ordered a few. The quality was good. The plastic was easy to cut, so I could make adjustments to the positions of arms and legs. I added clothing (not much, admittedly) and headdresses with scraps of styrene. The figures might not be identical to the ones in the Bérain drawings, but neither is the ship. I think these figures work fine. Shapeways also supplied me with figures to make the two missing statues shown on the Cherbourg Library drawing of the quarter galleries. The starboard one (the only one shown in the Cherbourg drawing) was Kronos, “Father Time,” the Greek-mythology titan, first king of the Olympian gods, whose symbols were a scythe and an hourglass. The figure I got from Shapeways was a standing figure of Zeus. I cut and re-glued the figure at neck, waist, and knees to give him more of a sitting posture and replaced Zeus’s thunderbolt with Kronos’s scythe. Why was Kronos there? What did he represent? What did he have to do with the sun-god Apollo? I don’t know if I ever found a good answer. In mythology, Kronos reigned during the “golden age” (this is where we get the term) before he was slain and replaced by his son Zeus, who in turn was the father of Apollo. So Kronos was Apollo’s grandfather. And his “golden age” might be considered to have returned under the reign of his “grandson,” Apollo-Louis. It didn’t make sense to repeat the same statue on the port side. Another accompanying figure was needed. What figure went along with Kronos, though? I decided it had to be Rhea, Kronos’s consort, first queen of the gods, Apollo’s grandmother, who served as midwife for the sun-god’s birth. Rhea’s main symbolic attributes were a mural crown (representing fortress walls) and a chariot drawn by lions. I opted to give my figure the crown and forget about the lions. Again, I used a nude Shapeways figure and dressed her somewhat with scrap styrene. I think I’ve caught everyone up on my Heller model to the present. Posts from me are going to get less frequent from now on. I’m busy right now working—and re-working—the masts and rigging. I’m on my fourth try at installing foremast shrouds. Man, I thought building the hull was tough. It’s nothing compared to the complexity of the rigging. Slow process. I thought I’d be done with this model in a year. Now I’m giving it two. My model has grown a beard. It’s all the lines running from the forecastle pin rails and deck cleats. I figured I’d better tie them in before the foremast shrouds go on and get in the way. I belayed the lines according to a rigging plan, so I know what each line is and where it is going to go once the masts and yardarms are up. Most of the lines are three feet or more in length. As far as postings go, there’s still a discussion of deck furniture to do, which I’ll put off once more. And my rigging diagram is in a constant state of re-evolution as I absorb stuff from Jean Boudroit's monograph The Three-Decker of the Chevalier De Tourville. You’ll find out more about that next time, whenever that will be. With the holidays coming up, it’s hard to tell how much modeling time I'll have. Happy Meleagris gallopavo day. The bird formerly known as turkey. Let’s all be respectful with our culinary nomenclature this Thanksgiving and eat some nice roast gallopavo with stuffing. And have fun building and rigging model ships over the holiday. Speaking of turkeys—

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

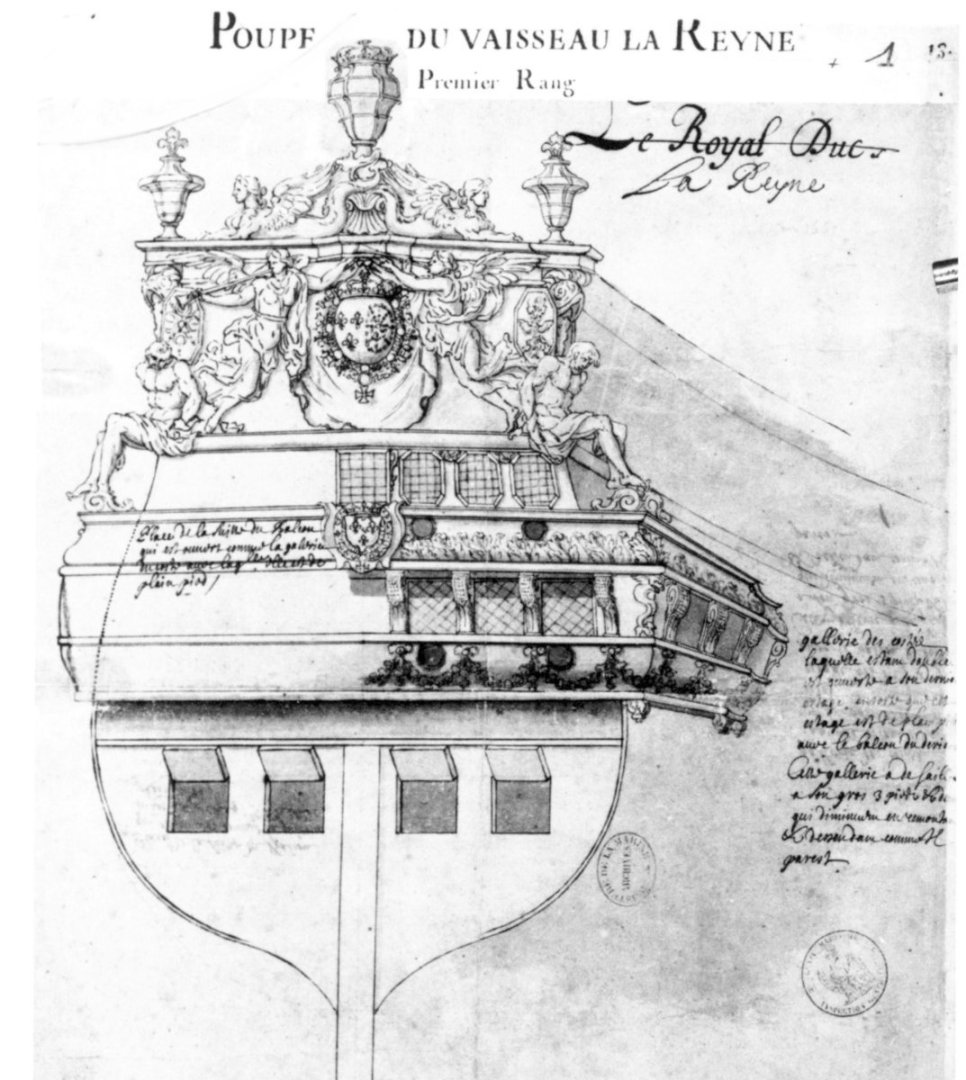

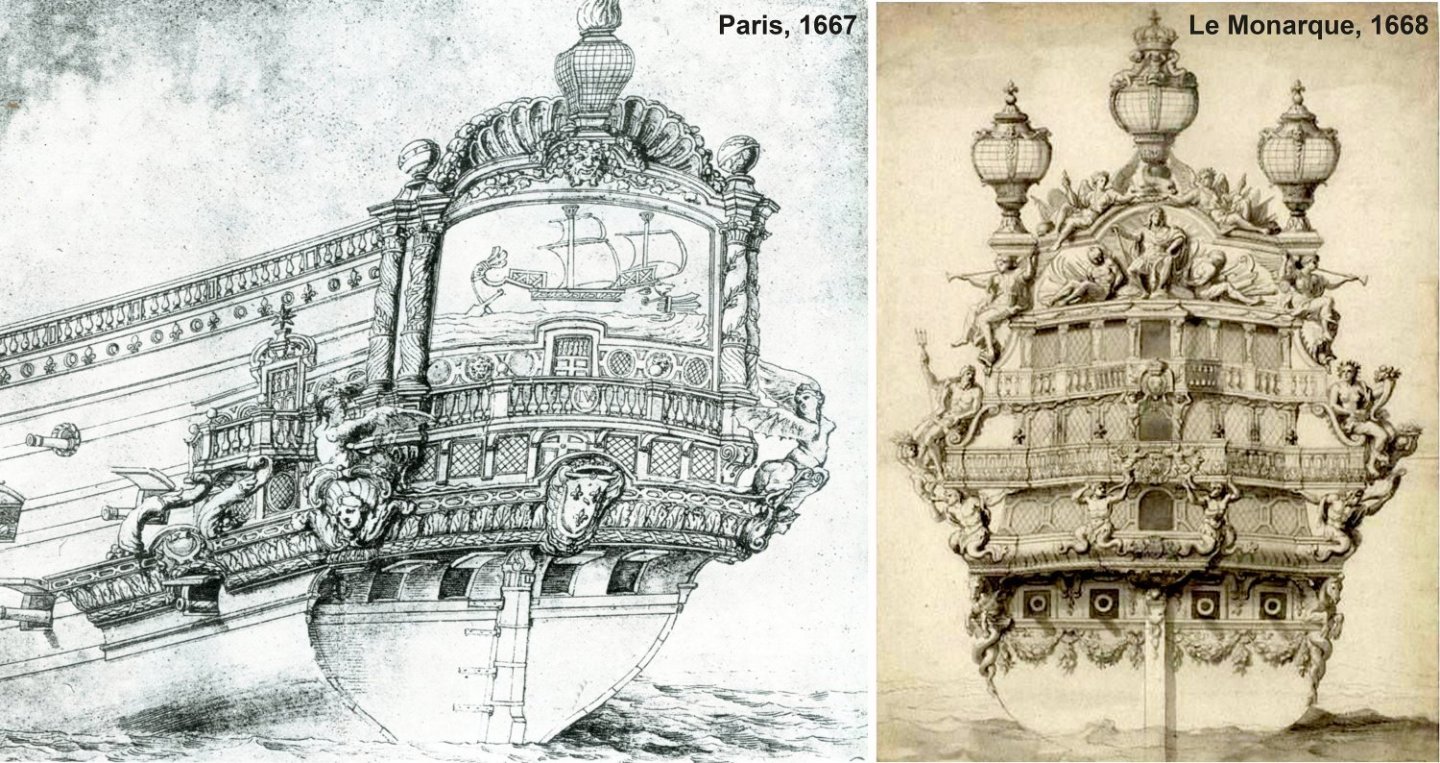

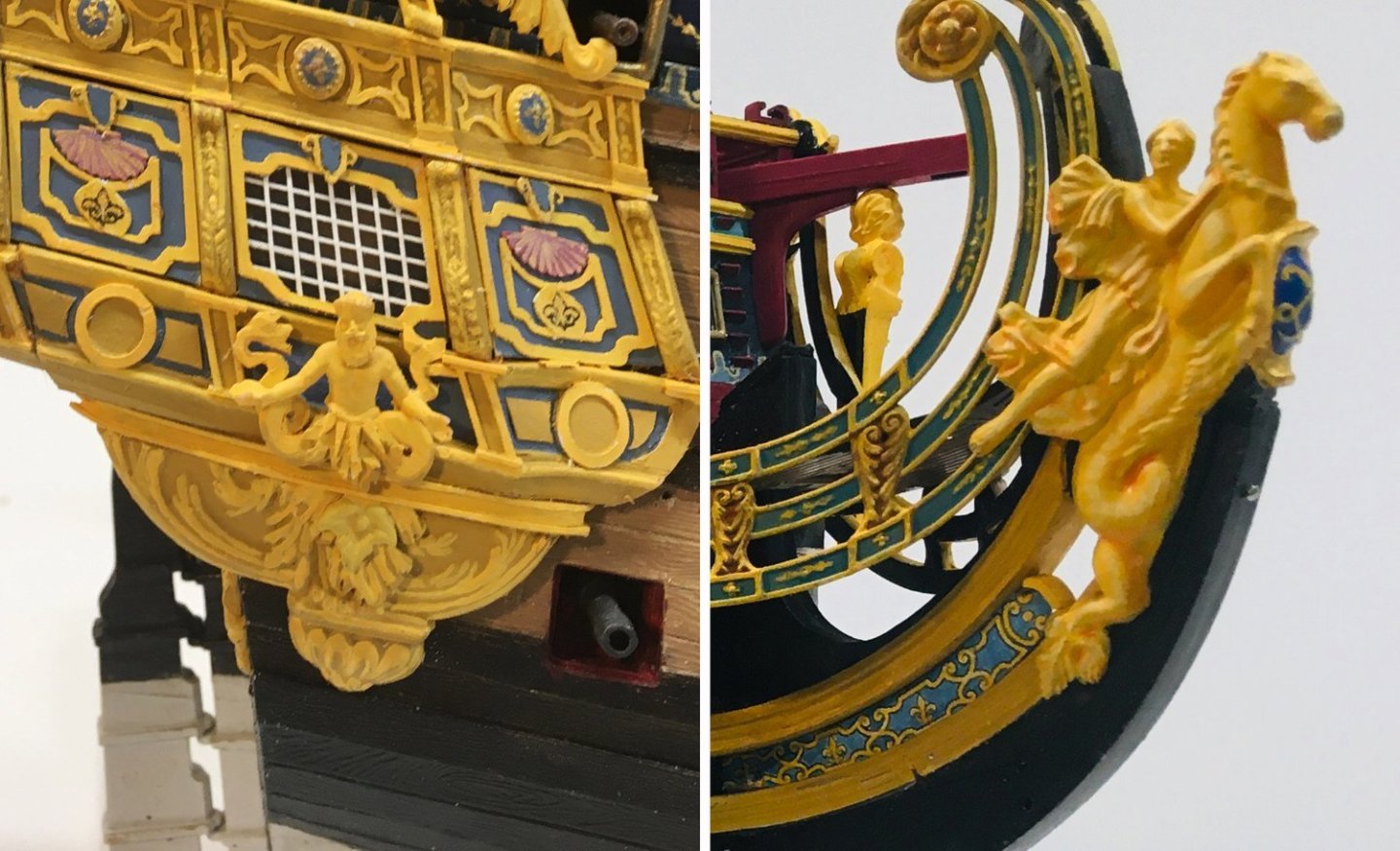

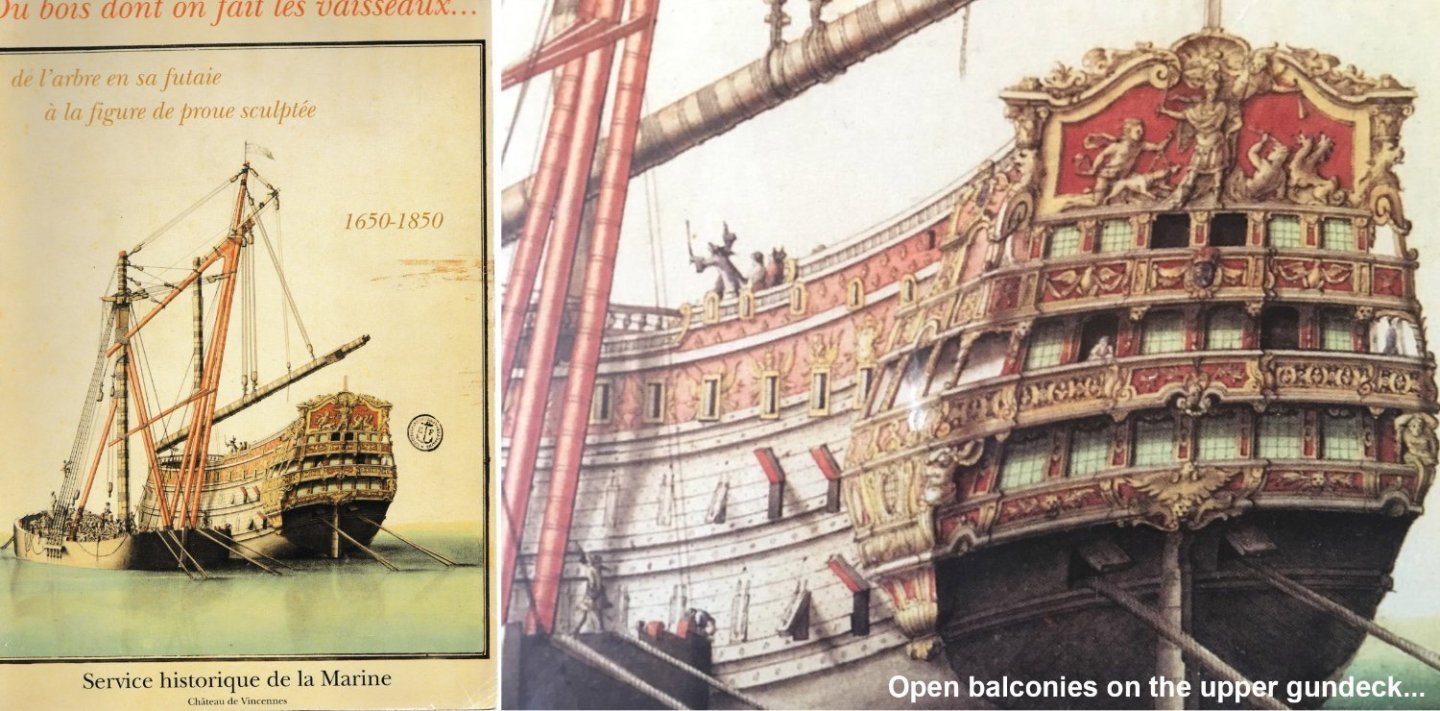

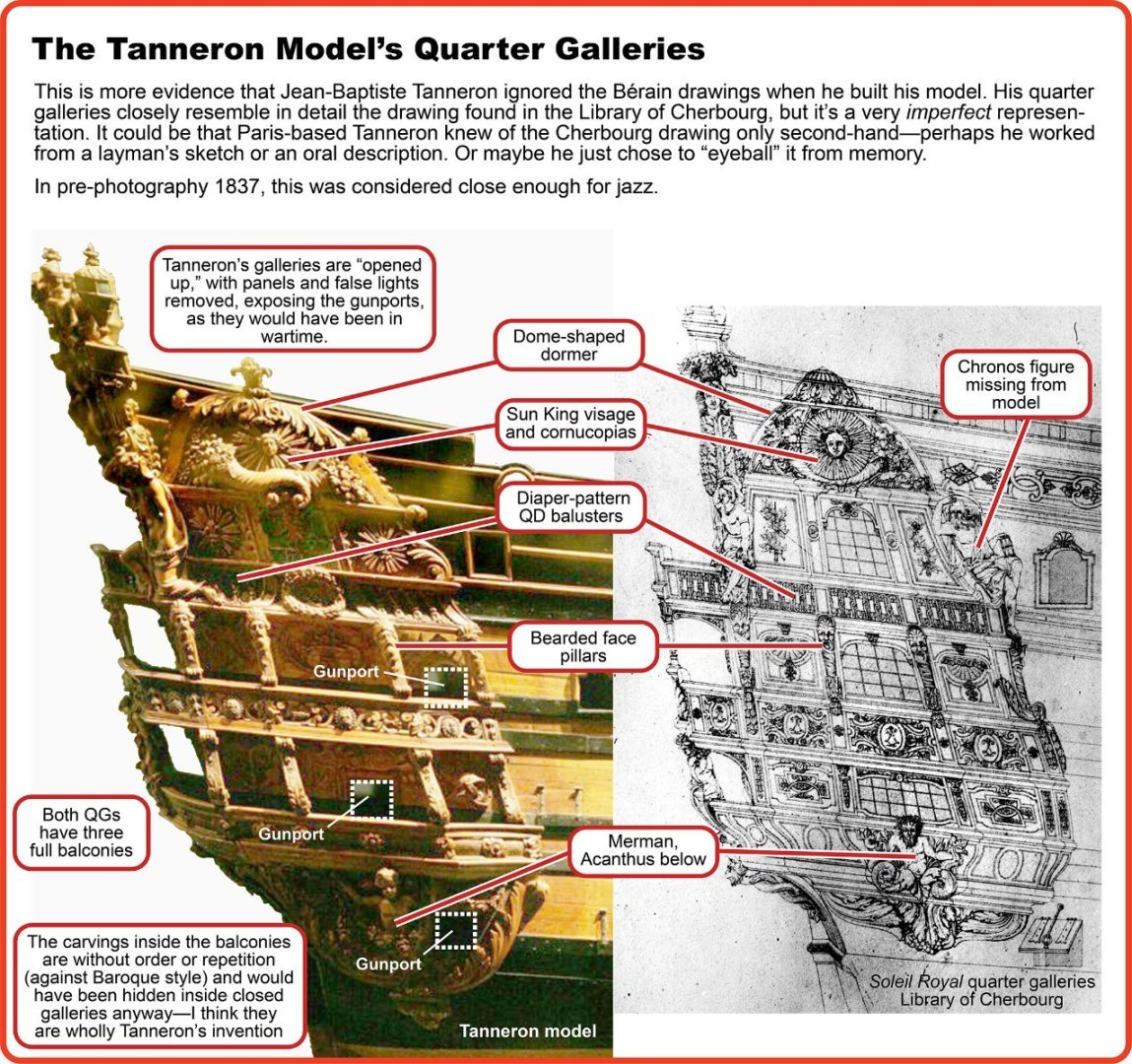

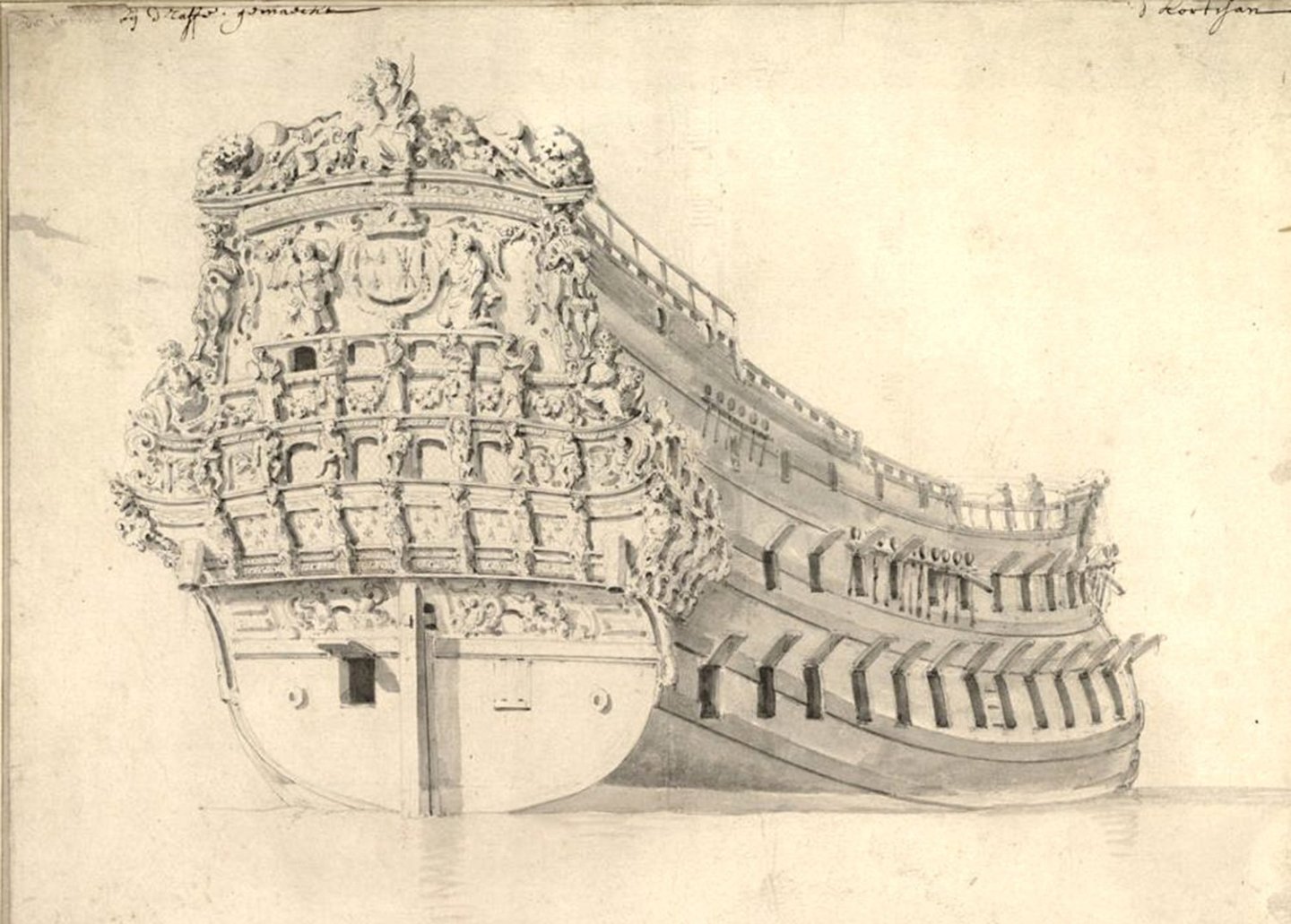

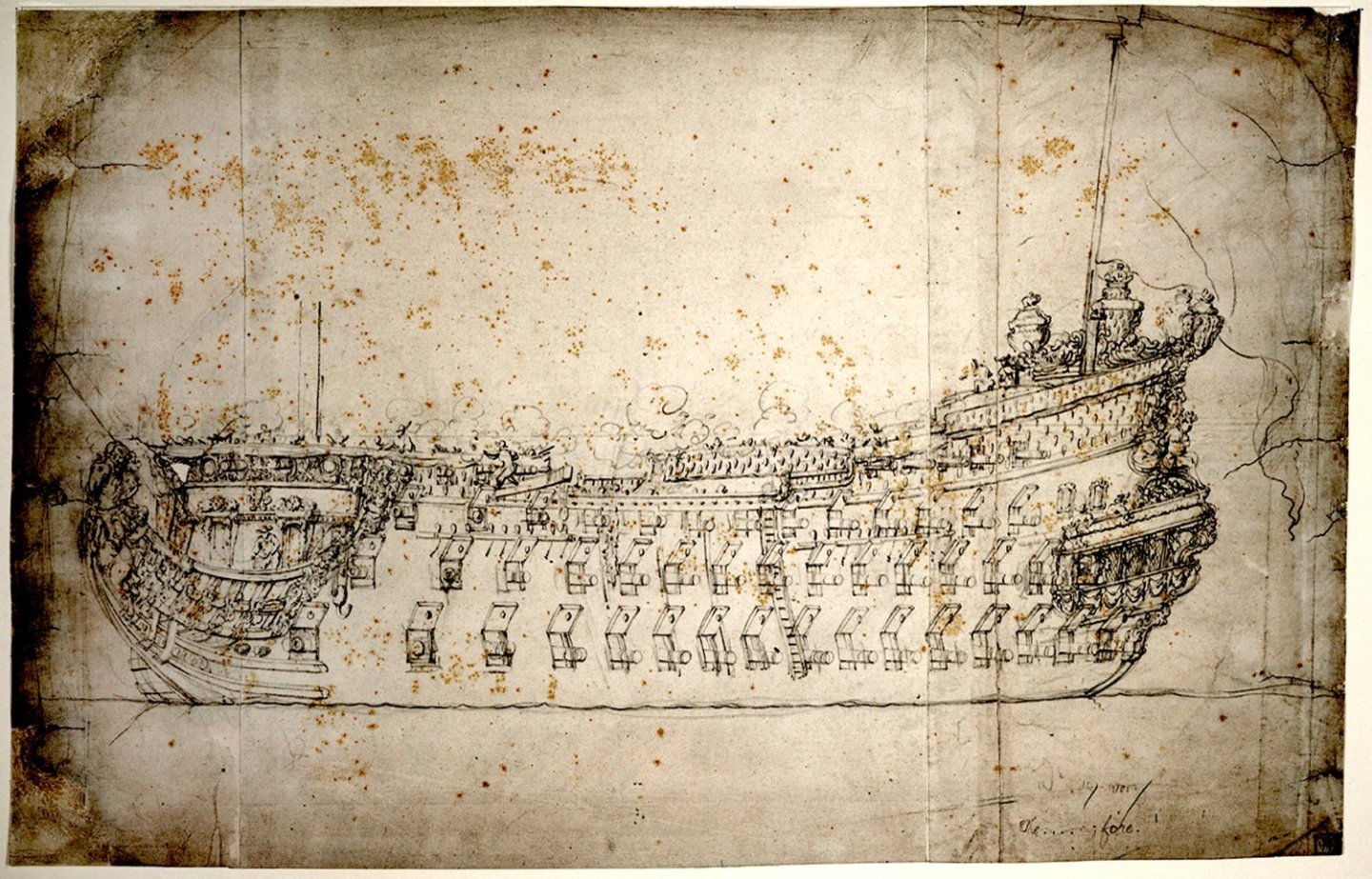

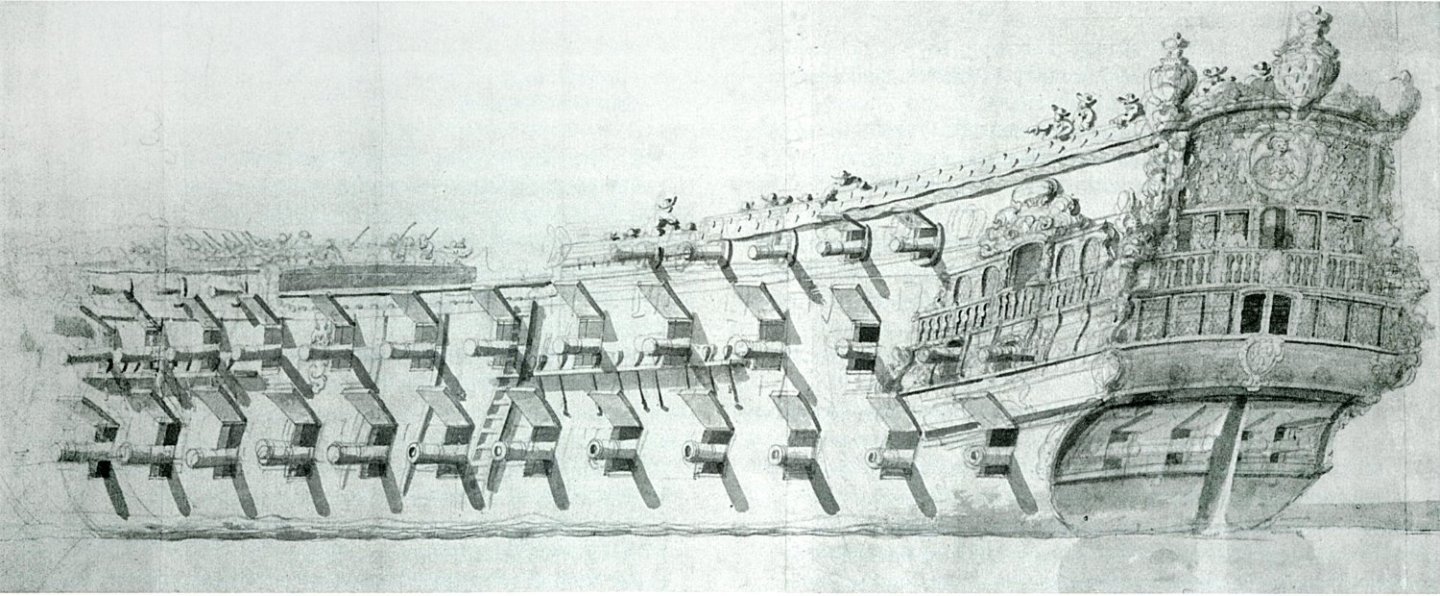

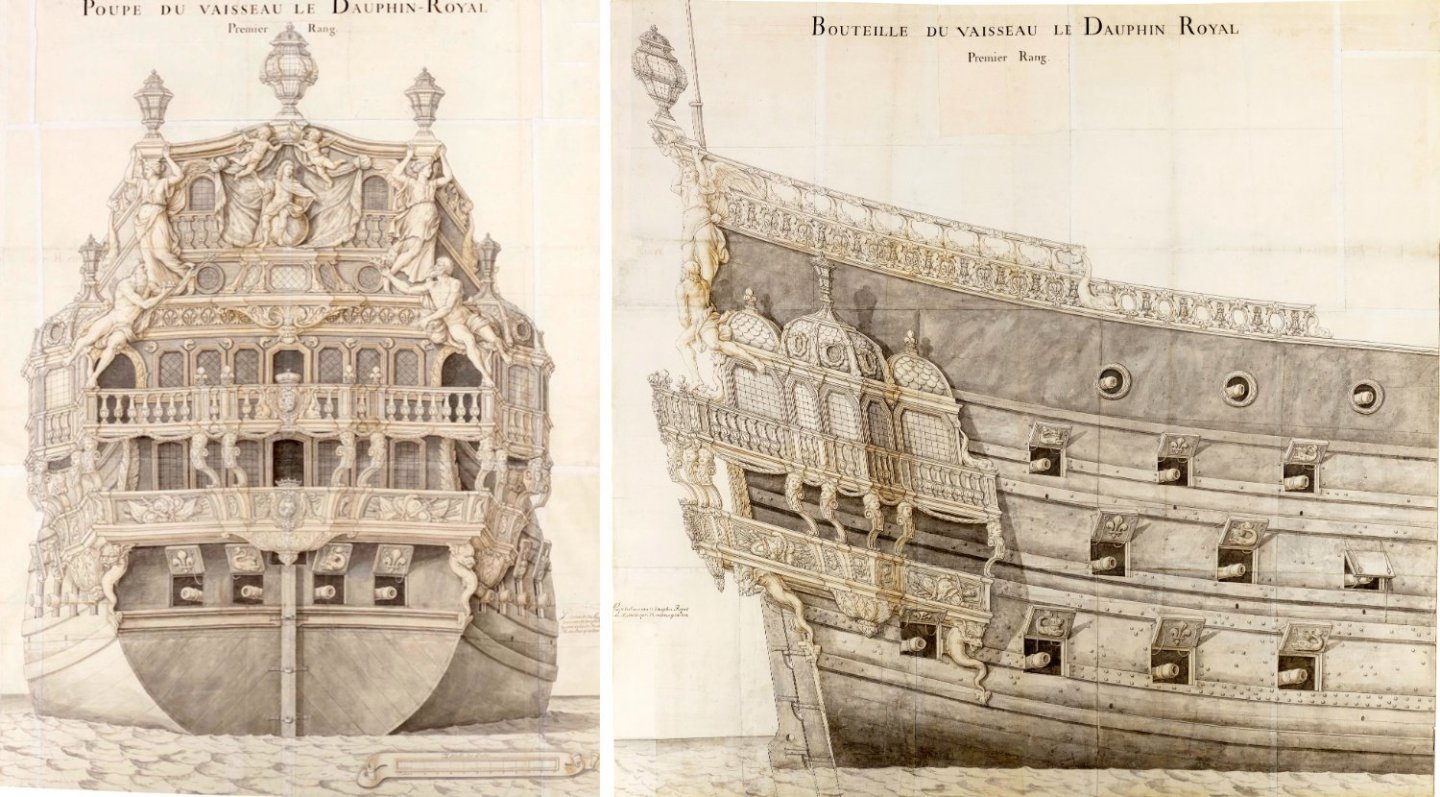

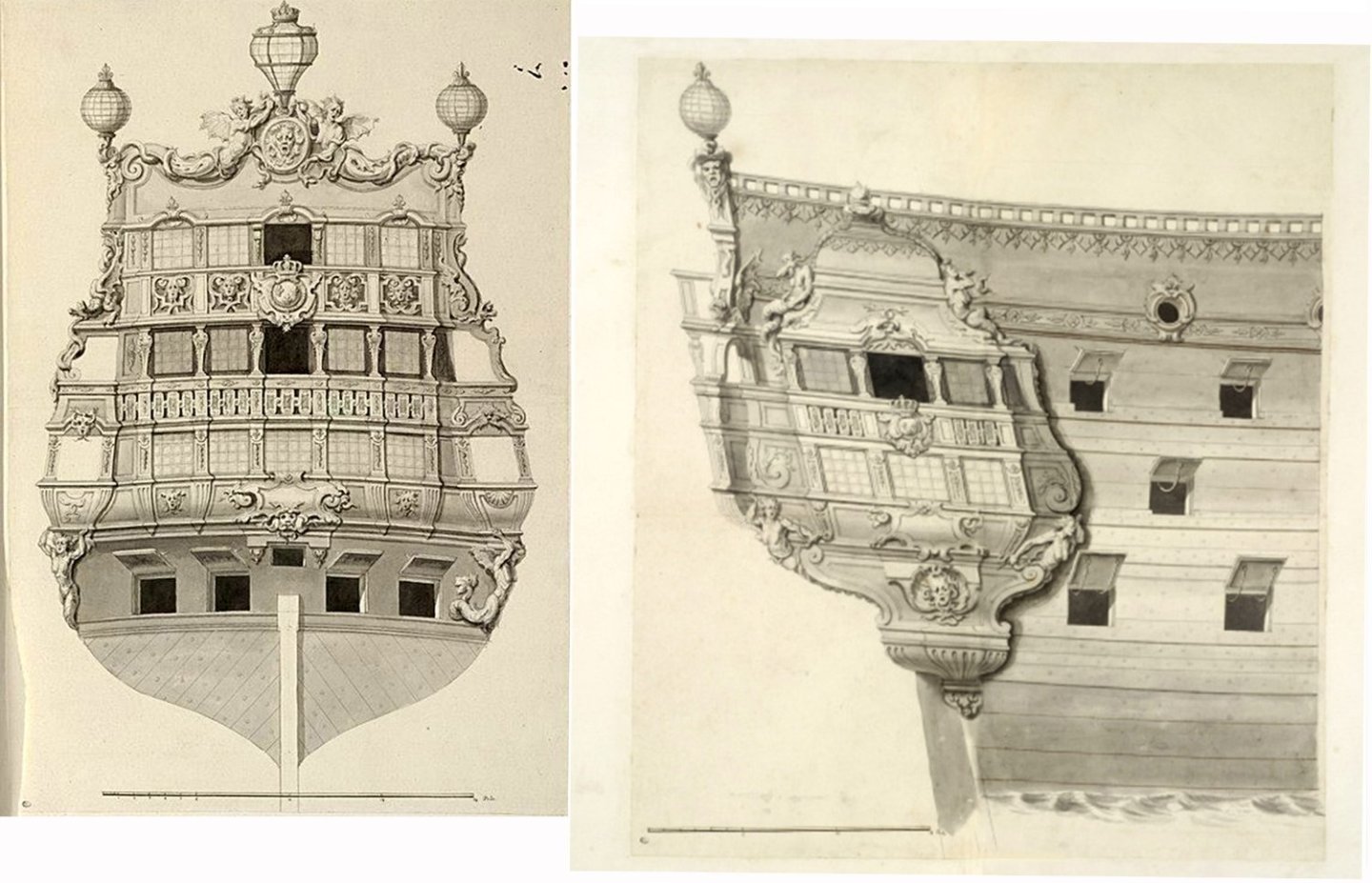

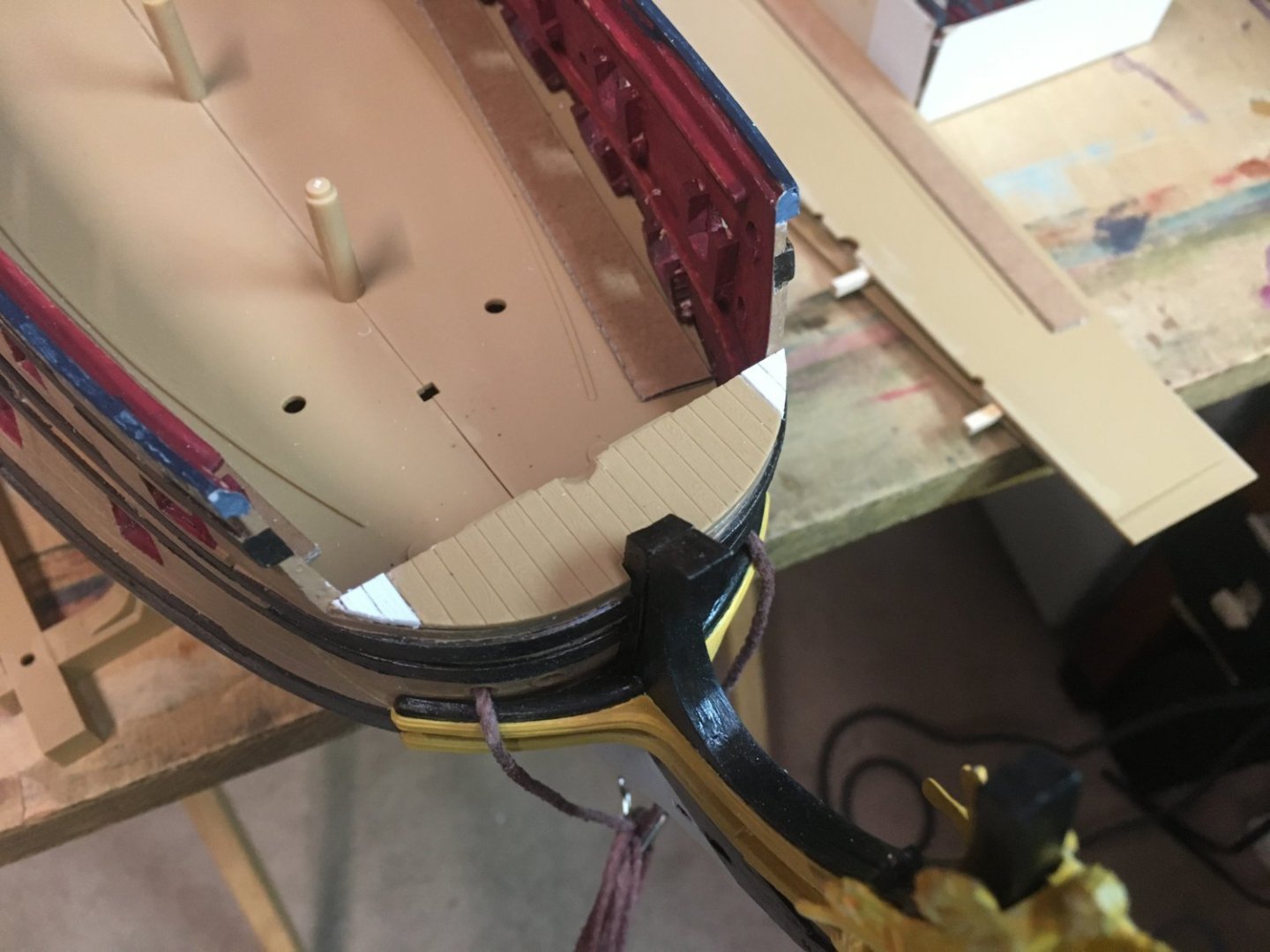

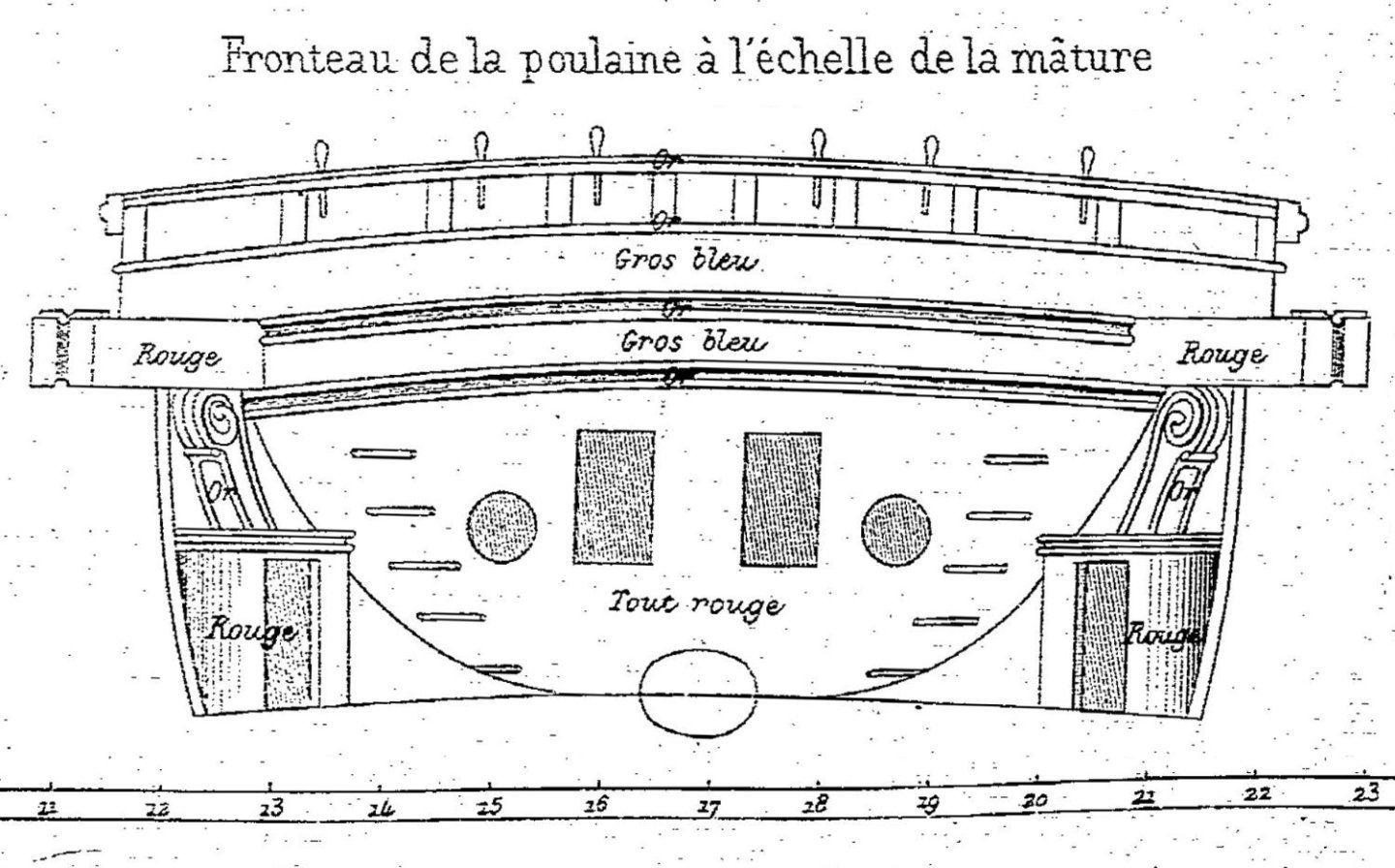

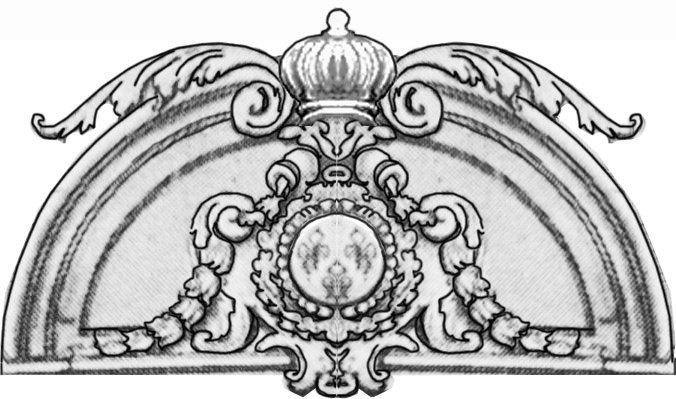

So what do we do with the Heller kit’s quarter galleries? They are kinda problematic, after all. Modelers have had a tough time deciding which version of the Soleil Royal the Tanneron model represents, and some think it’s the first 1669 version because of the open balconies on the quarter galleries. Warships from 1660s had open balconies as a matter of course. Nice . . . but complicating that analysis is the fact that quarter galleries on French warships were often built over the aft-most gunports. In times of war there had to be a way of opening those ports, and the practical solution seemed to be making the quarter gallery panels removable. To back this up, there are pictures of French warships from the 1690s that show open balconies, even though closed quarter galleries had been dictated by the Navy administration back in 1674. So—first version? Maybe so and maybe not. The Tanneron model is pretty obviously not the 1689 rebuilt version, because there are big discrepancies between the model and the Bérain drawings of the rebuild. Others modelers—like me—think Tanneron’s model is the second Soleil Royal, built in 1693, based on the layout of the gunports and the resemblance of the model’s quarter galleries to a drawing from the Library of Cherbourg which is labeled as belonging to the Soleil Royal but is definitely not the Bérain version. Here's the Cherbourg Library drawing. And here are the similarities to Tanneron's model— So where did this drawing come from? When did it come from? Can we tell from context? How do we know it wasn’t from some earlier version of the Soleil Royal? To answer that, we need to go back and look at the development of quarter galleries on French warships over a period of 35 years. The Soleil Royal was one of the first 100+-gun three-deckers built by the French navy. In the 1660s, realizing the need for bigger and better warships, Louis XIV’s ministers attempted to jump-start their shipbuilding program by hiring Dutch-trained shipwrights like Laurent Hubac, builder of the first Soleil Royal, and even by buying Dutch-built ships. Dutch shipbuilding at that time was the most advanced in the western world. Their ships had elaborate decorated sterns, but didn’t have much in the way of quarter galleries. The Courtesan of 1666, below, was one of the Dutch-built French ships. This is the kind of ship design the French emulated. The drawing is by Willem van de Velde. Courtesan Laurent Hubac’s first Brest-built ships had similar abbreviated galleries, like the 1669 la Reine (ex-Royal Duc). It had an enclosed middle-deck gallery (where the officers’ heads were) and an open balcony above it. (These are more drawings from Willem van de Velde . . . .) The first Soleil Royal was built that same year. la Reine Royal Therese, built in Toulon in 1669, shows the same idea. Royal Therese No drawings survive from the first Soleil Royal, but ship historians like Jean-Claude Lemineur were inclined to reconstruct the ship using the same principle. This went on for another five years, including ships like 1671’s le Terrible below, another one of Laurent Hubac’s ships. This shows that Hubac-built ships from both before and after the first Soleil Royal had abbreviated galleries. If I was making a conjectural drawing of the first Soleil Royal, I'd be making notes. le Terrible In 1673, the rather arbitrary decision from Paris was promulgated, advising shipbuilders that henceforth, quarter galleries would be built with all balconies enclosed, like on English ships. At the same time, the stern balconies were supposed to be reduced—in many cases, making the middle deck balcony into a false façade. I’m sure this didn’t settle well with the conservative Dutch-trained shipwrights. Surviving drawings show a lot of halfway measures, like the 1680 rebuild of the 1668 Dauphin Royal, where the upper gundeck balcony was given a little Moorish castle, but the middle gundeck balcony was left open. The next decade more or less corresponded with the arrival of chief decorative designer Jean Bérain, whose plans for sterns and quarter galleries made them look like little multistory Paris palaces or wings of Versailles. Here is le Furieux of 1684, built in Brest, and le Fleuron of 1689, built in Toulon. le Furieux le Fleuron Of course, there’s also Bérain's drawings of the proposed rebuild of Soleil Royal. By the time the second Soleil Royal was built in the early 1690s, the dormers of Bérain’s quarter galleries had taken on a definite dome shape, like on the Saint Philippe of 1693 and the Swedish Konung Karl of 1694. Notice that the Konung Karl sports twin-tailed mermen on the balconies very similar to those in the Cherbourg Library drawing of the Soleil Royal. Interestingly, it looks like all the stern balconies had depth, just like ones in the Cherbourg drawing. In that and other details, I would judge the Konung Karl quarter galleries closest in style to the ones from the Cherbourg Library. le Saint Philippe Konung Karl The Soleil Royal II was built in 1692–1693, one year before the Konung Karl. In other words, the KK drawing was probably made during the time the SRII was under construction. So—back to the Tanneron model. Yes, the model’s quarter galleries have open balconies, like the early French three-deckers. The problem is that it has too many balconies, plus upper works—dormers, domes, panels, and false lights— that just weren’t a thing on 1669 French warships. From the design and the detailing, the closest stylistic matches we have are the 1690s Bérain designs. I think the Cherbourg drawing came from a 1690s ship and so, by deduction, from the Soleil Royal II. This, I think, was the prototype for the Tanneron model. At the start of this post, I outlined the differences between the Tanneron quarter galleries (copied by Heller) and the Cherbourg drawing. I really wanted to redo the galleries to closer match the drawing. This didn’t sound radical at first. Lots of Soleil Royal modelers open up their QGs by carving away the relief panels which seem to have no relation to anything on real French warships. While doing the necessary styrene surgery, I planned on fiddling with the proportions a little—maybe give the QGs new, more accurate dormers. I had already extended the stern by 3/16”, intending to expose two of the three gunports incorporated into the QGs. I made some Photoshop sketches, showing my choices for opening up balconies. I decided to leave the upper gundeck gallery open, like in the second photo. That would give some added interest to the QGs and still give the 1/100 officers some privacy when they visited their heads. First, I had to finish the stern balconies and glue on the stern plate. I noticed that the balconies stuck out too far—four feet. I trimmed them back to 3 feet, similar to the surviving drawing. Had to trim the knees, too. The middle deck balcony was supposed to be a false balcony anyway, so it got trimmed the most—it’s only 2-1/2 feet wide. Oh—and I hated the sunflowers on the middle deck balcony. I checked—and yeah, they were considered official symbols of le Roi Soleil—but I had never seen sunflowers on any drawing of a French warship. On Bérain’s drawings, they were supposed to be cartouches (architectural oval frames), sometimes with Louis’s monogram, sometimes empty. Stern lights were affixed with Testors’ canopy glue. I thought the white cames (lead between the panes) looked cool. Time to take a deep breath and glue on the stern. Now for the quarter galleries. With razor saw and x-acto knives, I carved up the kit’s quarter galleries. Having embarked on an orgy of destruction, I never paused to take photos. Everything usable was trimmed out and set aside—besides the balconies and columns, that included all the figures, faces, and foliage. Then I could start Frankensteining everything back together again. I decided to keep the "drop" from the bottom of the galleries. It hid the waste chute, after all, but I trimmed it and repositioned it to keep it out of the way of the lower gundeck's furthest aft cannon. An important feature of the middle gundeck balcony was the mermen. Tanneron had placed them below the balcony and turned them into winged, garland-draped fairy figures. I wanted to put them back on the balcony where the drawing said they belonged, and also return them to being split-tailed tritons. For a first try, I attempted to repurpose the fairy figures from the kit, giving them fish-tails instead of garlands, and new bearded faces taken from the QG's quarterdeck level. Unfortunately, it soon became apparent that the figures were about 50% too large to fit comfortably on the balcony. This was a genuine moment of frustration. What to do? Carve new figures from scratch? Too bad I’m terrible at it. I have never felt competent making 3-dimensional sculpture. Should I check to see if the kit had any other figures I could use to make castings? Sure—but the answer was nope. Anything around my hobby desk? The house? Nope and nope. Go to the hobby store and see what I can scrounge for new figures? That sounded like a plan. Drink beer afterward? Even better. So a trip to the hobby store led me to a set of 1/72 Nexus plastic figures labeled “Ancient Life.” Are they supposed to be used for games? I don’t know. I don’t care. Looked promising. The set contained a number of bare-chested males with arms spread. Perfect. I cut them off at the waist, added fishtails and beards carved from scrap styrene, and I had my two split-tailed tritons. Excelsior. I glued on the first four balconies. Paper templates told me where the columns were going to go and what size the panels and false lights needed to be. I was making progress—or so I thought. But the columns and panels weren’t lining up with anything. There should have been some vertical elements on the balconies that met the columns. Plus, the sunflowers were bugging me again. Before too long, I called a halt and went to find another beer. Then I ripped away the new balconies plus the stern middle deck balcony, and started over again. This time I built the balconies from scratch using Evergreen sheet and strip styrene. This time, the balconies and panels had their connecting vertical elements. All the sunflowers got deep-sixed in favor of blank cartouches. Happier? Yeah. For the quarterdeck balcony, I had made a lot of little castings of the diaper-pattern balusters from the stern with mold putty and 5-minute epoxy. I cut them apart and assembled them with more strip styrene into railings. The false dormers and lights above the railings were made with more sheet and strip styrene. It took me a while to stare at the Cherbourg drawing and figure out what was painted on the side panels of the dormer—swords and olive branches. War and peace. All righty then. I painted on the foliage and cut the swords from scrap strip styrene. Tanneron’s (and Heller’s) QG domes had the same elements as the ones in the Cherbourg drawing, but Tanneron carved them in a way that I don’t think would have been acceptable in Louis XIV’s time. The king’s beaming face was small and secondary compared to the giant cornucopias Tanneron carved surrounding it. One thing Baroque art teaches you—the king is never to be shown as being of lesser importance. That feature needed to be fixed. The new domes with the smaller cornucopias and the Sun King’s large radiant countenance were made with sheet styrene decorated with small sections salvaged from the kit’s QGs. The showers of fruit and foliage coming from the cornucopias were cut and shaped from the originals. The domes' lanterntops are two stacked bead caps from the local craft store. Since all this involved Louis’s smiling autocratic face, I gave the domes a coat of Vallejo 70.996 gold. As planned, the golden dormer-tops perfectly complimented the gilded Apollo frieze on the stern. Longue vie au Roi. I was pretty much done with the stern and quarter galleries, but there were still other details and figures to add. Does anyone really want to hear about how I tore off and rebuilt the lower quarter galleries a third time? I thought not . . . . Next time, I'll discuss the figures in detail, and French ship carvings in general. And you'll see the discourse on deck furniture and belaying plans that I had promised, but didn’t get to today. Stay out of trouble 'till then. Remember, if it isn't Baroque, don't try to fix it.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

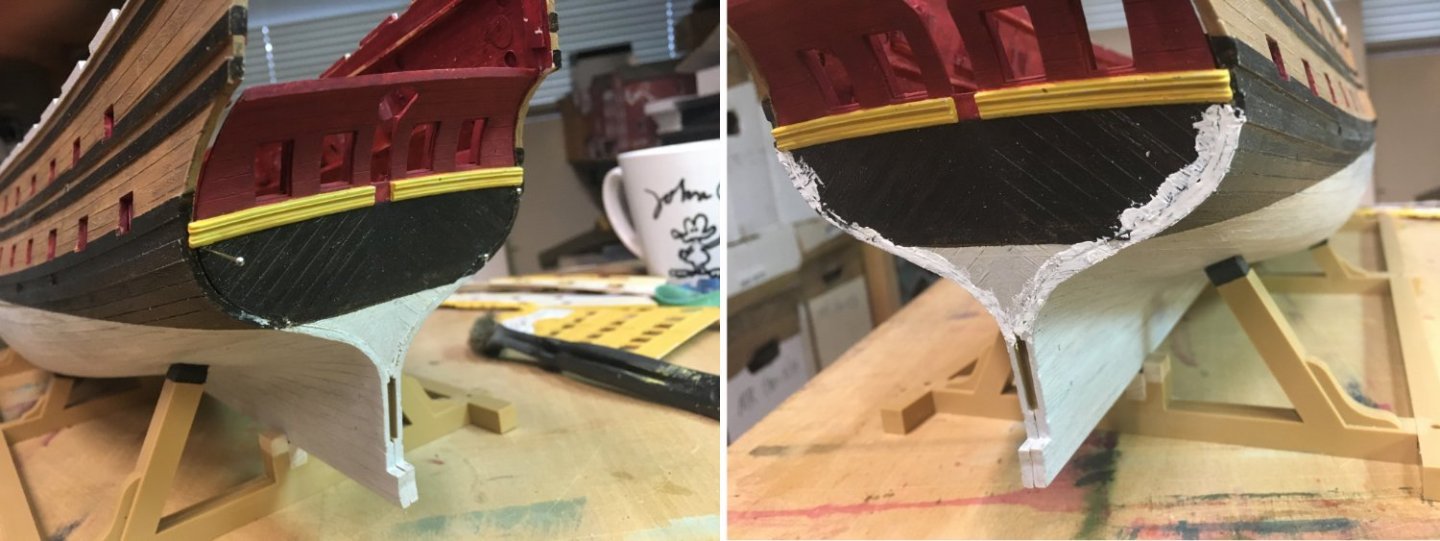

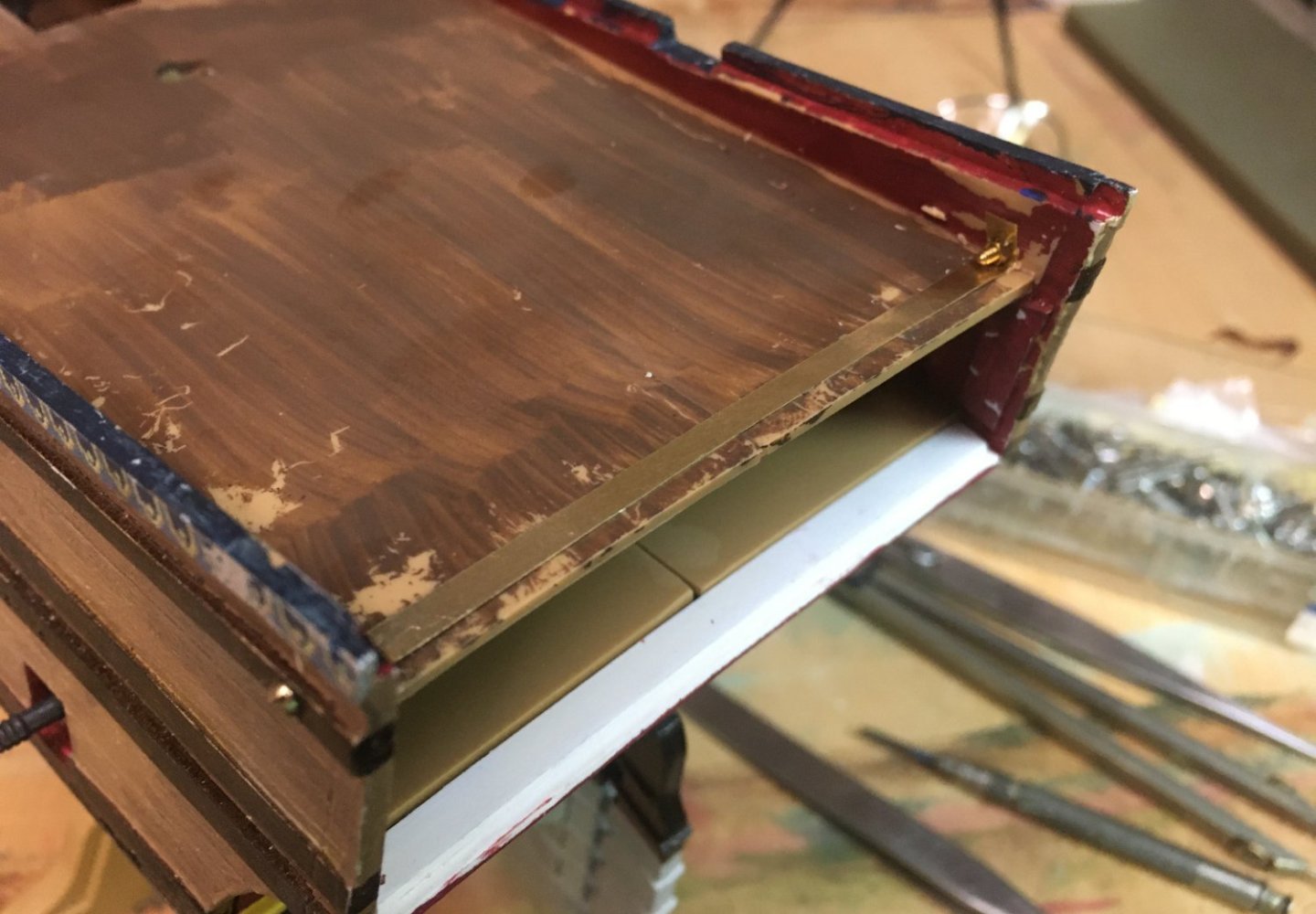

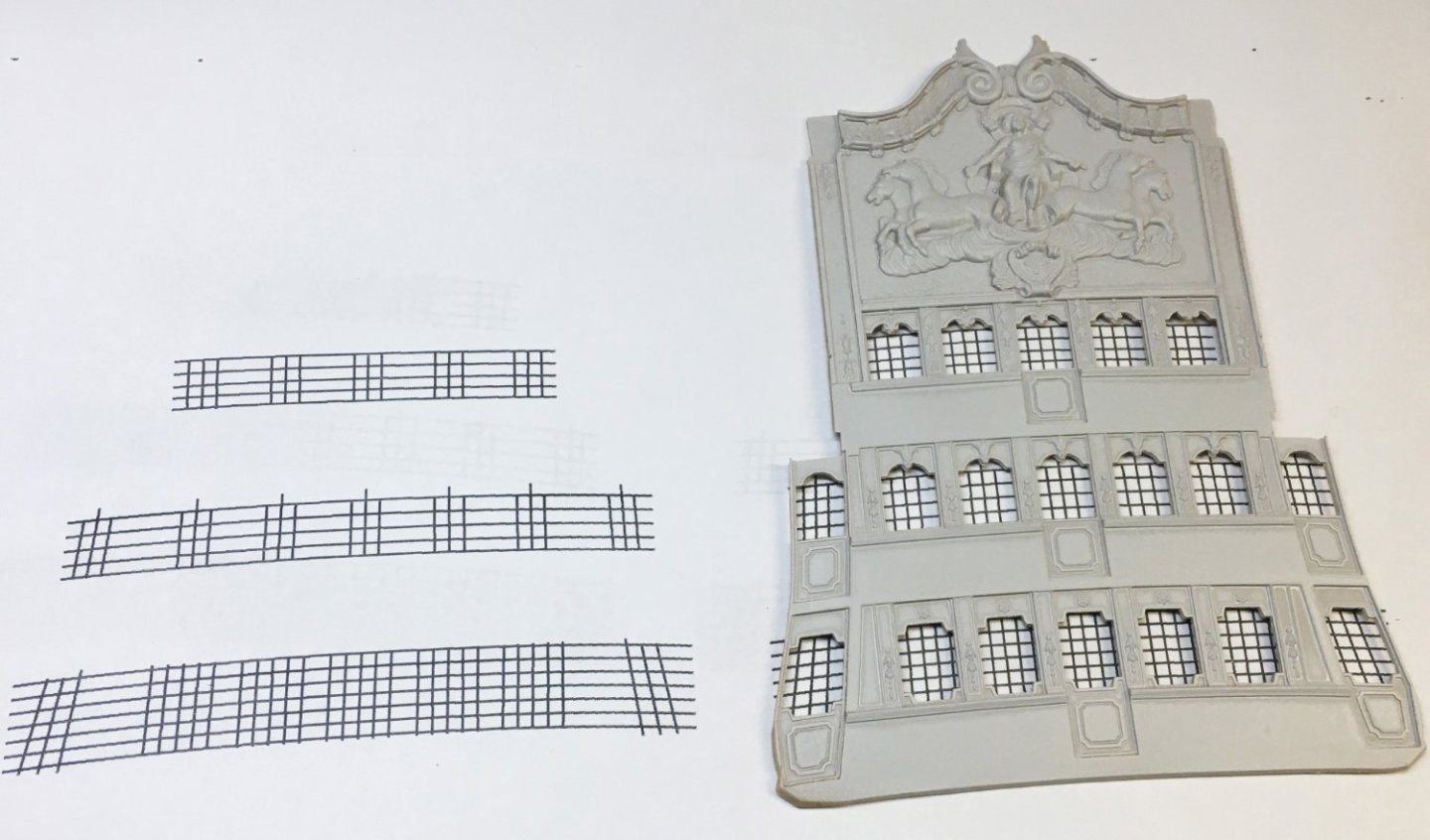

Welcome back. Here's my little tub recently, about half-done, and waiting on me to get a passing grade in rigging 101, as taught by M'sieurs Anderson, Marquardt, et Boudroit, so we can continue the build. Setting the "D–" in rigging class aside, getting to this point was fun and what I'll be blathering about today. At the end of about three months' work, I was finally ready to put some glue to parts and start assembling the hull. Sides and decks were painted. I had the guns ready for mounting. With binder clips, I could put it all together to see how everything fit. But I still had to make some improvements to the bow and stern—the subject for today. So where to start with the bow? One obvious thing is to remove the s—. . . ahem, roundhouses. Nobody except maybe officers could expect privacy on a 17th-century warship (their facilities were in the enclosed quarter galleries). Roundhouses weren’t even introduced until the early 18th-century. This was a period-inappropriate goof made by Tanneron on his model and copied by Heller. It was time for surgery. The roundhouse bases were sliced off the beak deck and replaced by strip styrene. The insets for the roundhouses on the front of the forecastle were likewise patched. Next problem, the front of the forecastle was too plain for my taste. I had a drawing of the 1693 Royal Louis that gave me a clue where to start—blue above; red below. It made sense to me to continue the colors and patterns from the hull sides around the front, so I made decals that matched. I ended up painting over most of them, but you'll see that evolution presently. I had read that the royal ships mounted the king’s arms on the bows. I used mold putty and epoxy resin to copy the royal emblem from the stern. I added a crown—a little brass jewelry stamping from Etsy—because that was how royal arms were always supposed to be displayed. (On the stern, the crown is above the frieze, under the center lantern.) I was sort of okay with this until I got a look at the forecastle on Marc La Guardia’s beautiful ship. Then I wasn’t okay. I was jealous. (It has happened more than once!) I went back and studied every old painting and drawing I could find, looking for a fancier treatment of the royal emblem. I came to realize the king’s arms got special artistic consideration wherever they appeared. They were usually isolated from the other design elements by some sort of containment— a box, a shape, a frame— that indicated how exaltedly separate the king was from everything mundane. He didn’t mix with the hoi polloi. In the Bérain drawing of the Soleil Royal’s stern, the king’s arms were isolated by a lunette. I decided to make a similar complimentary lunette for the prow. Eventually, I settled on copying a lunette from a drawing of another ship, Le Fleuron. The lunette was made from scrap styrene, plus the earlier resin casting and a pair of brass stampings I found on the Etsy website. This was beginning to look better. (Thank you, Marc, for the inspiration!) I continued the planking and wales from the ship’s sides around the front, because that seemed to be a neat thing on certain antique ship models. The beakhead slats were turned into gratings by adding thin styrene strips. It just seemed more logical, if anyone was expected to walk there on a rolling ship without turning an ankle. Eventually, I added a pair of “seats of ease” to the head. They probably should have both been two-holers, but I never could figure out how even four seats could have serviced a crew of 900. I’m sure there were other… avenues of relief. Moving on. Heller’s knee of the head has a lot of odd detail—like the holes for the bowsprit gammoning placed parallel to the waterline, and all those mold lines indicating separate pieces of wood. I saw some modern reconstructions, like Jean Boudroit’s drawings of L'Ambitieux, that show something similar, but other descriptions say the knee was made from just a few large pieces. I decided to just de-emphasize everything. I took the white putty, sanding sticks, and drill bits to the pieces and did some revisioning. When it came time to glue the knee to the hull, there was significant gapping—but nothing a little tapered strip styrene and white putty couldn’t handle. The ship’s figurehead was beautiful, but a mold flaw deprived the fairy sea nymph (or whatever she was) of her port wing. I carved another from sheet styrene. Instead of gold leaf, it looked to me like most ship’s statuary from the Baroque was faux gold—different shades of yellow ochre, with bright lead-tin yellow for highlights and browns or oranges to deepen shadows. Sometimes the formula included a coat of Burgundy pitch (spruce resin) with powdered copper or brass. There are some examples of faux gold nautical statuary in French museums. I used them as color models when I painted the figurehead. This worked out well and I now knew what to do when I got to the figures on the stern. The colors I used were the same mix of Vallejos and generics I had on hand—Vallejo 70.948 golden yellow, 70.858 ice yellow, 70.911 light orange, and a generic craft acrylic, "antique gold" which was a perfect yellow ochre. I couldn’t glue on the headrails until the bowsprit was installed and gammoned, but I could paint them. Here’s another example of special treatment for royal symbols—I decided the face of the Sun King surrounded by the sun’s rays was worthy of gold leaf. It and the royal arms are practically the only gilded parts on the bow and beakhead. I ended up gammoning the bowsprit twice—once, after mis-reading a measurement and using too light a rope. I cut it away to do the job over with the proper diameter rope. I followed the description and diagrams in Anderson’s The Rigging of Ships in the days of the Spritsail Topmast 1600–1720. Once the gammoning was on, I could fit the headrail braces, made from more Evergreen sheet and strip styrene. The oddball geometry of the beak and headrails defied making accurate measurements, so it took forever to cut cardstock templates, fit, cut again, fit, trim, fit—then do the same repeatedly with the Evergreen plastic—cut, fit, trim, fit—start again—cut, fit . . . . Forward to the stern. I decided to paint the lower stern red for a couple of reasons—first, it matched the red on the lower part of the forecastle. Second, I was inspired by this 1834 painting of the Foudroyant by Auguste Étienne François Mayer. Which seemed to perfectly capture the “look” of a Baroque French warship I was trying for. The lower stern piece didn’t quite fit the hull halves without a lot of coaxing with clamps and rubber bands. I didn’t want glue joints giving way at some later date, so I opted for a more metal solution. I drilled for pins to hold the lower part of the stern-piece in place. Then, after the glue was dry, the heads of the pins were clipped off. White putty improved the joints. The upper part was fixed by pulling the hull pieces together into a tight fit and installing a brass strip attached with screw-headed bolts and nuts. The bolt-heads would be invisible inside the quarter galleries. Since I had extended the stern 3/16”, the middle gundeck got an matching extension with a lip to hold the stern plate. The stern plate wouldn’t get glued on until I had finished the balconies and was ready to do the quarter galleries. In the meantime, I made sure the piece fit the new stern extension perfectly. I thought the rear gunports were oddly proportioned—a little too tall—so they were cut down in size by the addition of some decorative framing. The cut-down doors were decorated with the king's monogram (more decals). It was here I decided that the gunport doors throughout the ship were going to be held open by blackened wire—not thread. I disliked the way thread looked when it was slack, and I never found a way to make both sides taut at the same time. The stern lights on the Heller model are supposed to be leaded windows. But instead of thin cames (the proper name for the lead strips between panes), the kit windows have fat three-inch mullions. Kind of typical for a small-scale plastic model, but not optimal. I decided to give them another try. First, I put the stern on my scanner and made a to-scale digital image of it. Then I chopped out the thick mullions— On my laptop, I used the scan of the stern plate as a template to draw new lead cames in Adobe Illustrator. When the time came to assemble the stern, I printed the cames on a sheet of laser printer transparency film. After seeing how the dark cames disappeared against the dark windows, I decided to use the printout as a template and make the cames with thin white chart tape on clear styrene. It made them fatter again, but they still looked better than the plastic mullions. An important but missing element on the stern plate was the lunette that separated and highlighted the king’s arms. This was very evident on the Bérain drawing of the stern. The crest was too important an element to be simply built into the frieze. So, after scribing a guideline with a circle template, I got out more sheet and strip styrene. This element was important to Baroque thinking. As mentioned before, the king’s emblems were almost sacred, and they were almost always isolated and given priority over all other visual elements. The king’s arms here would later get painted with expensive ultramarine blue and gold leafed. The stern plate was given two shades of yellow— yellow ochre (generic “antique gold” craft acrylic) for the lower “background” surfaces and Vallejo 70.948 golden yellow for the higher “foreground” features like frames and decorations. Where blue was needed, I used the same old 70.943 grey blue to match blue verditer paint. The king’s Apollo-in-his-sun-chariot frieze was designed by Charles Le Brun after Le Brun’s similar Apollo fountain in the gardens of Versailles. The fountain statuary had been originally covered in gold leaf (I understand it has recently been restored to gold leaf again). That fit right in with my notion that the only major parts of the ship that were genuinely gilded had to do with the king himself. Back when I was making Photoshop mock-ups, I had planned to gild the Apollo frieze and the Sun King's face on the top of the quarter galleries. I made a few minor changes to the paint scheme on the fly—using the lighter blue on the Apollo frieze and giving it a white frame instead of more gilding. The frieze was painted white. After it dried, I carefully masked to separate the white frame from the frieze’s blue background. The gold followed the blue. I had brand-new fine-tip sable detail brushes, so I hand-painted the whole thing. Apollo-Louis and his steeds got painted Vallejo 70.996 gold with 69.060 old gold on the undersides for shading. Feathered it so there wasn't a hard transition. Gold was also used for the zodiac frieze above and the chains of bellflowers between the lights. The insides of the upper gundeck and quarterdeck balconies got some of the leftover decals, continuing the patterns from the sides around the stern. I later painted the insides of the false balcony on the middle gun deck red, like an interior bulkhead. The lights got their white-chart-tape cames, sealed onto the clear styrene by a coat of Testor’s canopy glue. I would finish the stern balconies later, in concert with the quarter galleries. The model **finally** got glued together. By this time, I had been working on the ship for three months. In the photos below, you can see the mostly-hidden lower and middle deck guns sitting on their simplified carriages glued to cardboard strips. In theory, the cardboard was supposed to provide a little "give" and prevent guns from breaking loose every time they were bumped. I didn’t want any light-colored plastic decks visible through hatchways, hence the big blob of brown paint on the middle gundeck. Around the second time I accidentally knocked a gun barrel loose, I realized my cardboard-strip scheme wasn't doing its job. Some added protection was needed. I made a clamshell box out of 3/16” foam-core, masking tape, push-pins, and string. Same width as the model's cradle. Undo the string and the sides fall away flat. The model wears its boxy cuirass to this day and it’s one of the most useful ideas I’ve ever had. Haven’t knocked a gun loose with my big clumsy hands since. I can carry the ship without disturbing anything on it. This is handy since the model has outgrown my workbench and has to sit beside me on a TV tray while I prepare parts for it. When not being worked on, the model gets boxed up and set on a two-foot shelf that will someday be an extension of my . . . (pardon the expression) . . . ahem, model railroad. As the build progresses, I’ve cut away portions of the box to expose parts of the ship I didn’t want the foam-core rubbing against. Before I could install the upper decks, I had to figure out a rigging plan so I could finalize the deck furniture. Then I needed to make quarter galleries. This will all be discussed next time, along with a little history of the development of French quarter galleries. Until then, Honneur, patrie, valeur, discipline—and 5-minute epoxy. That should cover it.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hi Daniel. The knowledge I have comes from from sources like Winfield & Roberts' French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626–1786 and Jean-Claude Lemineur's The Sun King's Vessels. The latter book is a focused monograph on the development of French three-decker warships. That and all the other sources I've read say that the SRII was built as intended, a 100+-gun three-decker, originally meant to be named Foudroyant. It wasn't modified from a smaller warship. It was already completed and ready for decoration at the time the issue of renaming came up. That being said, it's entirely possible the ship sat lower in the water than intended. Ship design science wasn't great before the age of slide rules. Nobody really knew the displacement of a ship before it was launched. All that had to be adjusted by adding or removing guns, ballast, etc. However, it's hard to escape the fact that Tanneron used a lot of exaggeration with the proportions of his model. Even if we ignore the shallow draft, which isn't close to the 24 feet mentioned in surviving records, there's the issue that Tanneron built his model with eight feet between gun decks. There's just no way any shipbuilder back then would have done that. I think the best suggestion is that Tanneron exaggerated the proportions to give more emphasis to all the remarkable miniature carvings he made for the stern of the model. Good enough reasoning for me.

- 103 replies

-

- Soleil Royal

- Ship-of-the-line

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.thumb.jpg.31390171e38ce2ea1395f821332ab98c.jpg)