Glen Senkowski

Members-

Posts

10 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

Canute reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

Canute reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

lmagna reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

lmagna reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

lmagna reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

lmagna reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

Old Collingwood reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

Old Collingwood reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

mtaylor reacted to a post in a topic:

HMT Olympic by Glen Senkowski - Trumpeter - 1/200 - PLASTIC - RADIO

-

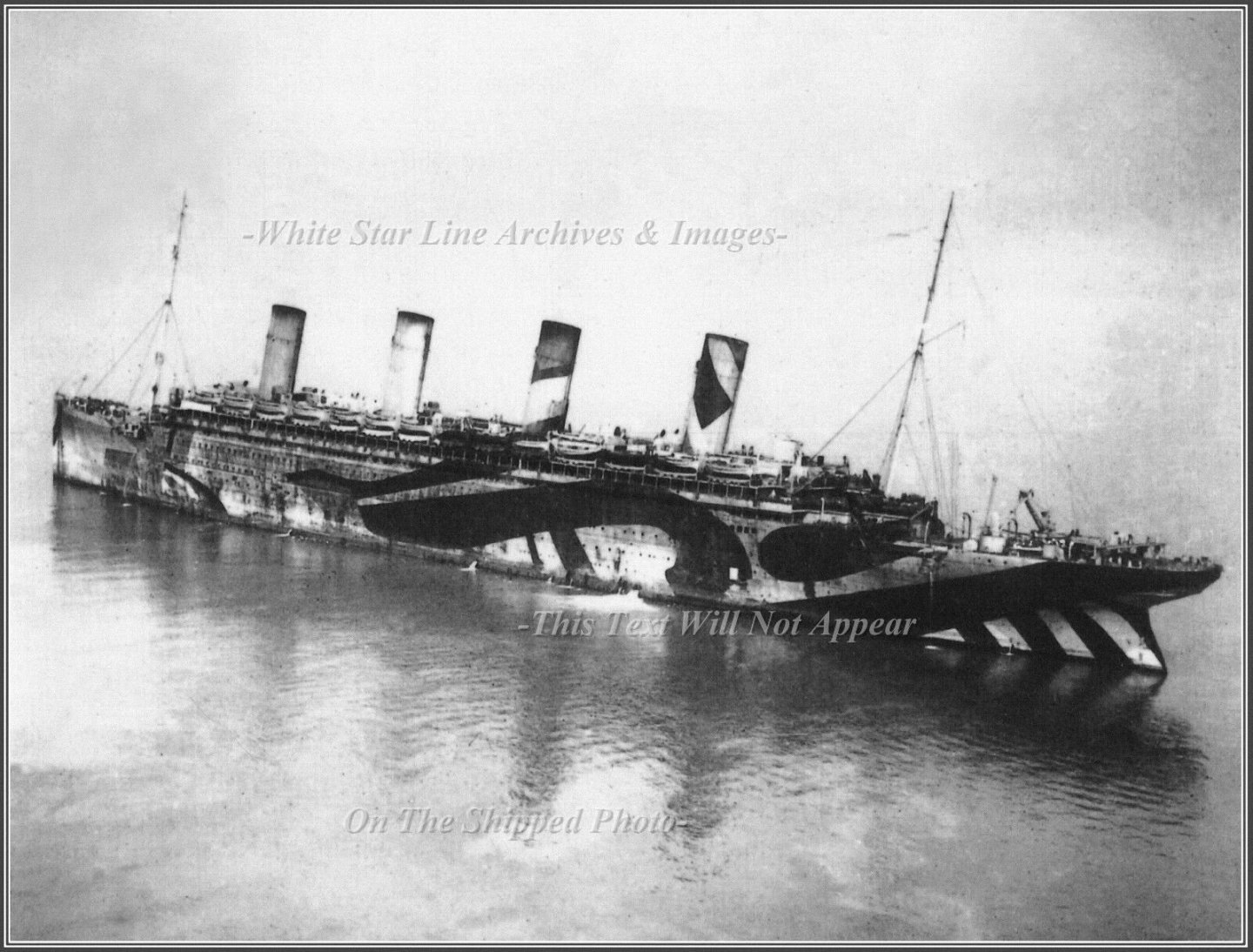

A port side view of scheme 19A in port, probably taken during the same voyage as above. It is likely that the aircraft that took these photos escorted the ship out of port and into open water. Note in this photo that the weapons are stowed and the lifeboats still have their canvas on. Judging by the extreme wear, she has been transporting troops for some time.

-

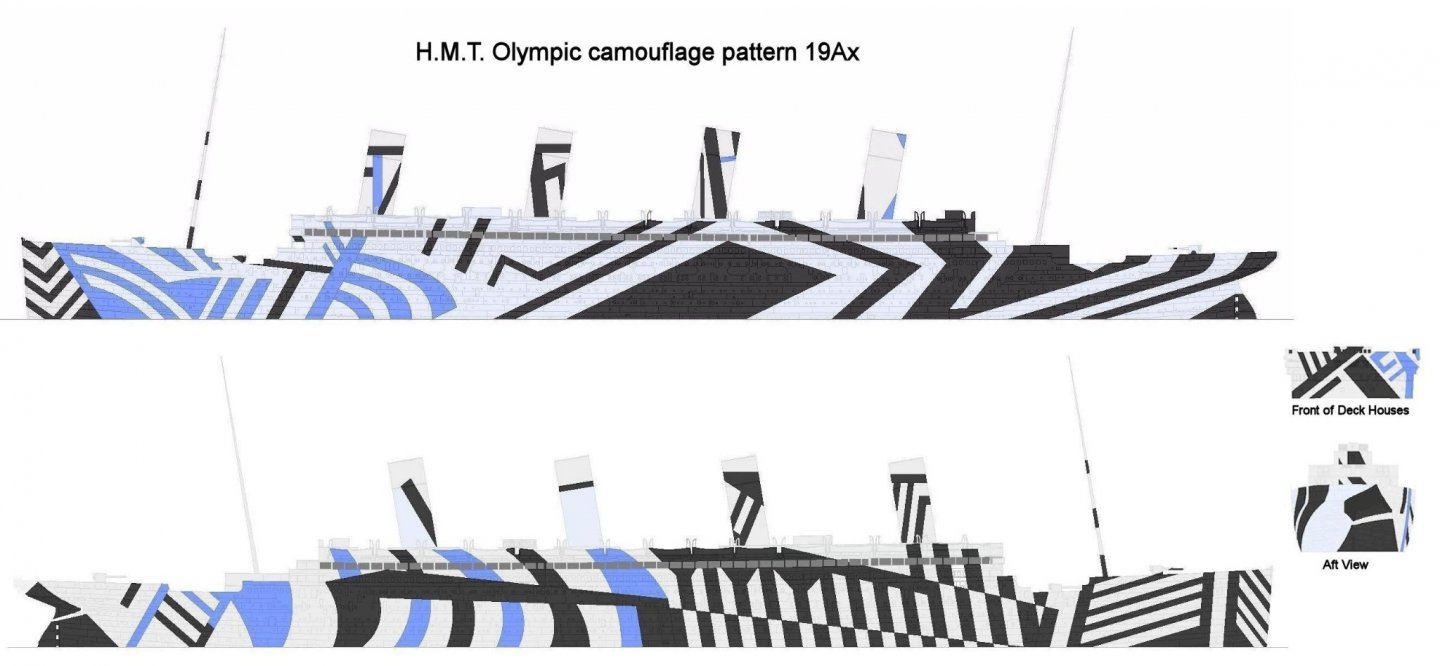

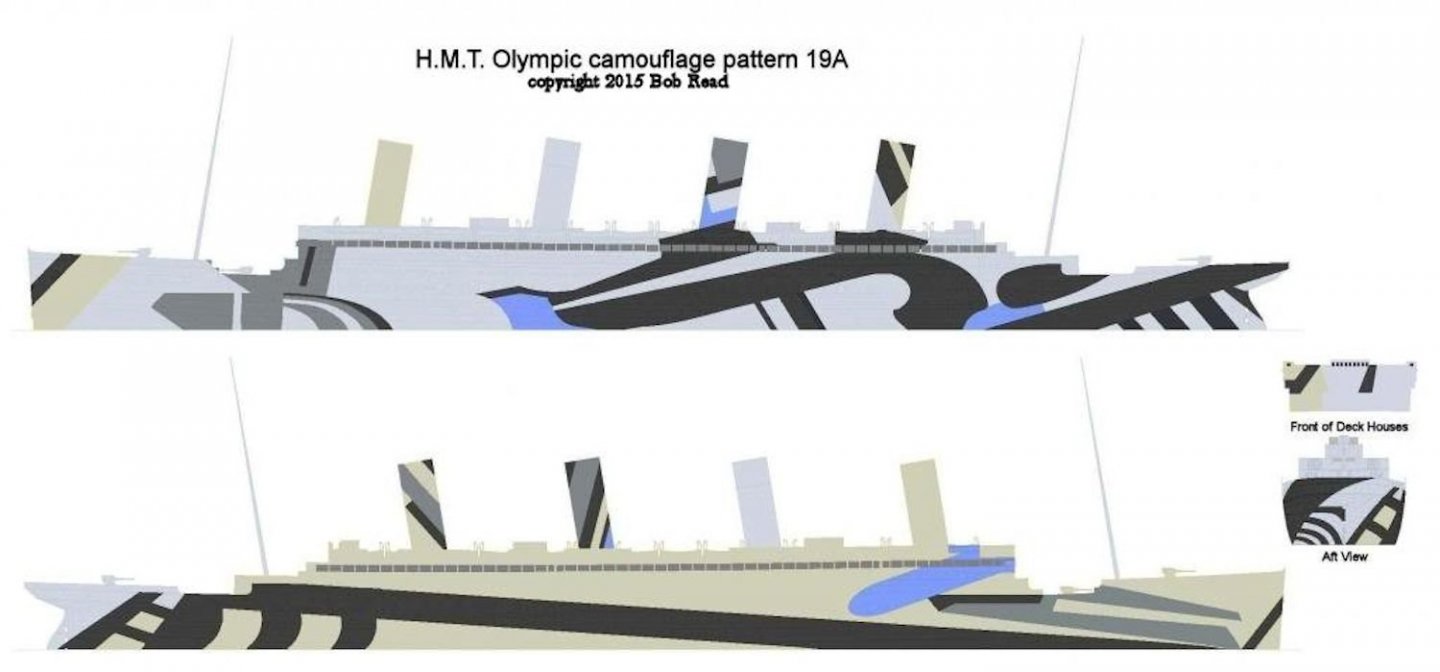

These are the wacky dazzle camouflage schemes that sold me on building the Olympic! She had two main versions: scheme 19A applied in 1917. Sometime in 1918, the scheme was changed to 19Ax, which remained until the Armistice. Mixed up photos of the two schemes are all over the internet, and cause a lot of confusion. Since no original color photos exist, the easiest ways to tell the two schemes apart are that 19A had solid colors on funnels 1 and 2, And 19Ax had the zebra stripes on the bow. Along with being literally "colorful," she had a colorful service history, transporting over 200,000 troops and intentionally ramming and sinking an enemy submarine! Sometimes the prey becomes the hunter. The Captain received the DSO for this action. Unfortunately, post-war, she also accidentally rammed and sank the US lightship Nantucket.

-

CONVERTING RMS TITANIC TO HMT OLYMPIC. Using the 1/200 Trumpeter RMS Titanic as the base kit. Acknowledgements. The vast majority of the source data I used were taken from the Titanic CAD Plans website, created by Dr. Bob Read. Sadly, the operation has been permanently closed, but the site is still available as a research center. If you purchased any of the Olympic plans when they were available, I would like to get some information off them, because the thumbnails on the site are too small for me to see some of the details. Caveats. This is just a construction log; historical information is available all over the place, so I will only discuss them as they relate to building the model. Also, I am not attempting to rebuild the Trumpeter kit from the keel up. To me, it is perfectly fine for what I am doing. If you are wanting to 100% "accurize" the kit, like correcting the stern hull plates, etc., I recommend visiting 1/200 Titanic Builders Group on Facebook. This kit has upgrade detail products available out the ying yang. I have no vested interest in any of these products, but I will describe what I used and why. HMT OLYMPIC. Below is a photo of Olympic in camouflage scheme, 19A. She is underway at around her full speed of 23 knots, with a full load of troops. She is in battle-ready condition, with lifeboats swung out and her complement of (6) 6" guns manned and ready (the aft two are visible on the poop deck.) She is also flying the white Royal Navy battle ensign from her aft mast. This scheme was applied in 1917 and sometime in 1918 it was changed to 19Ax. Note that the canvas is removed from ALL of the lifeboats: it was a lesson learned by the sinking of Britannic that she might be needed to offload her entire complement of approximately 4,000 souls in less than one hour! Of particular interest to me is the two long booms swung out near the forward well deck. I believe these are for handling lines to operate the paravanes, but if you have other ideas, please comment.

-

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

-

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

-

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

-

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

-

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

Glen Senkowski reacted to a post in a topic:

USS Keokuk 1863 by Glen Senkowski - 1/32 scale - Union Ironclad Ram

-

Roger, I found the letter: "The exigencies of the public service are so pressing in the gulf that the department directs you to send all the iron-clads that are in a fit condition to move, after your present attack upon Charleston, directly to New Orleans, reserving to yourself only two." Gideon Welles, April 2, 1862 [sic] Pretty sure they meant 1863, since the letters are listed chronologically. Maybe they wanted them to hook up with the Union fleet first before being sent to Mobile.

-

Hi Roger, I will recheck my source, which is an original House of Representatives copy of the Report of the Secretary of the Navy In Relation to Armored Vessels, 1864. I could have very well been having a Senior Moment! :-) I completely agree with your assessment of ironclads and the referenced book has some "lively" messages that went back and forth between DuPont and Welles. I give them each 50% credit for the boondoggle that is remembered as the Ironclad Attack on Charleston. (DuPont's Chief Engineer of Ironclads, Stimers, had a hissy-fit both before and after the battle, and DuPont tried to have him court-martialed.) Had Keokuk made it into the inner harbor, it would have - in my opinion - easily sunk both Chicora and Palmetto State, even in a combined engagement.

-

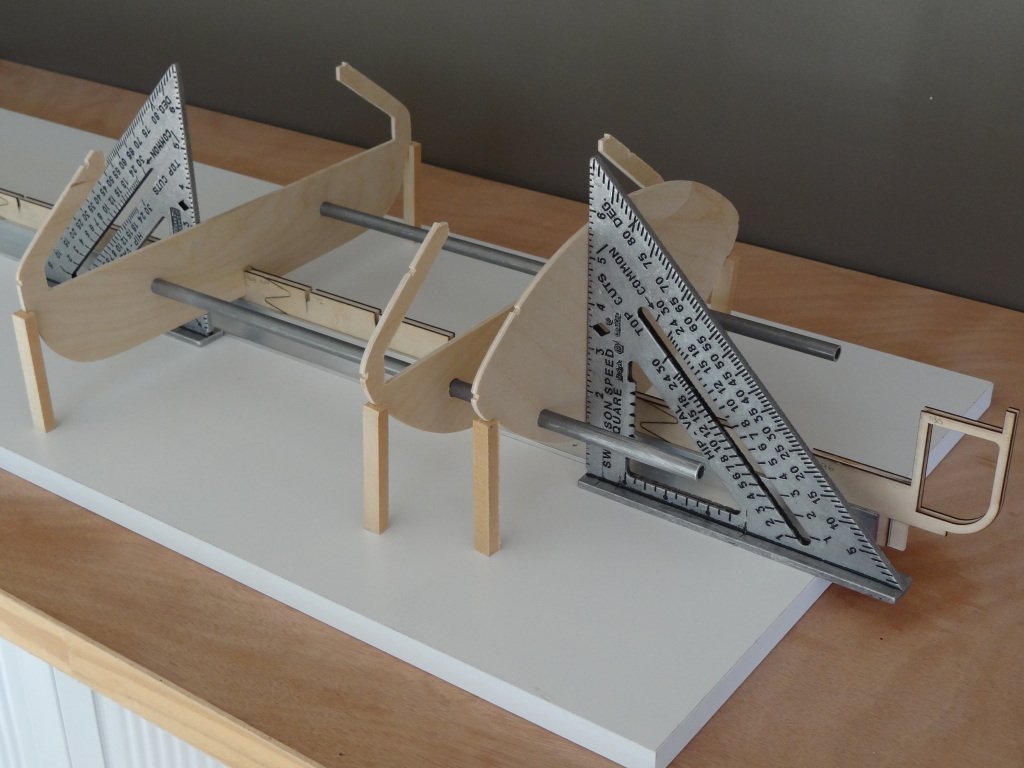

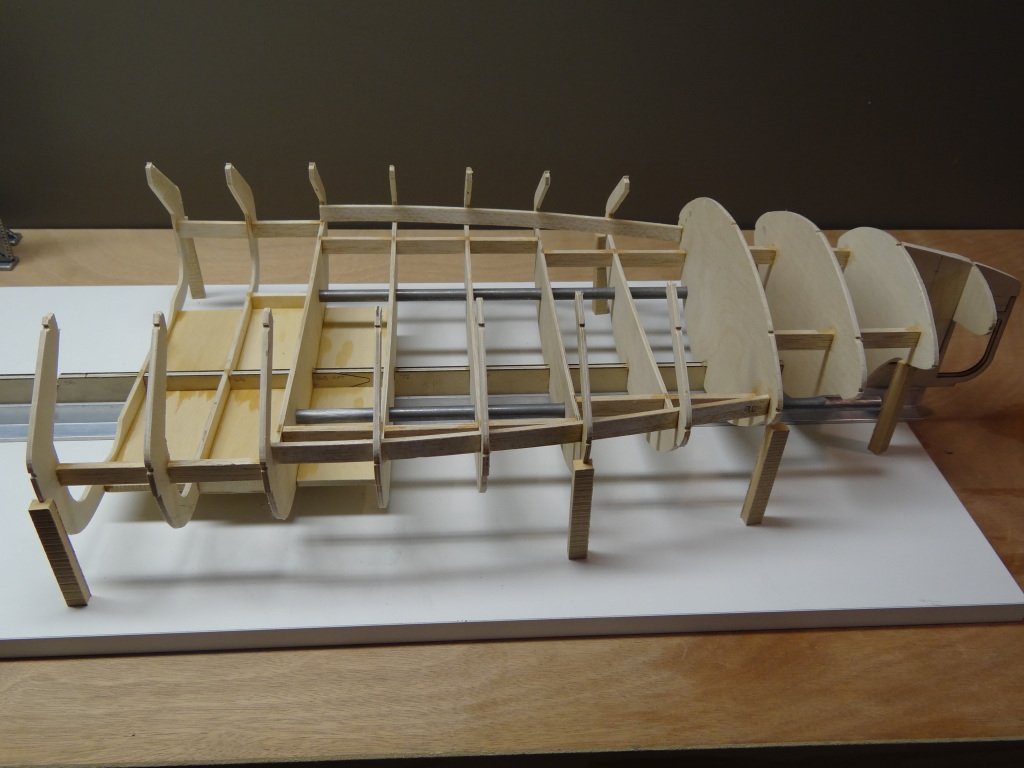

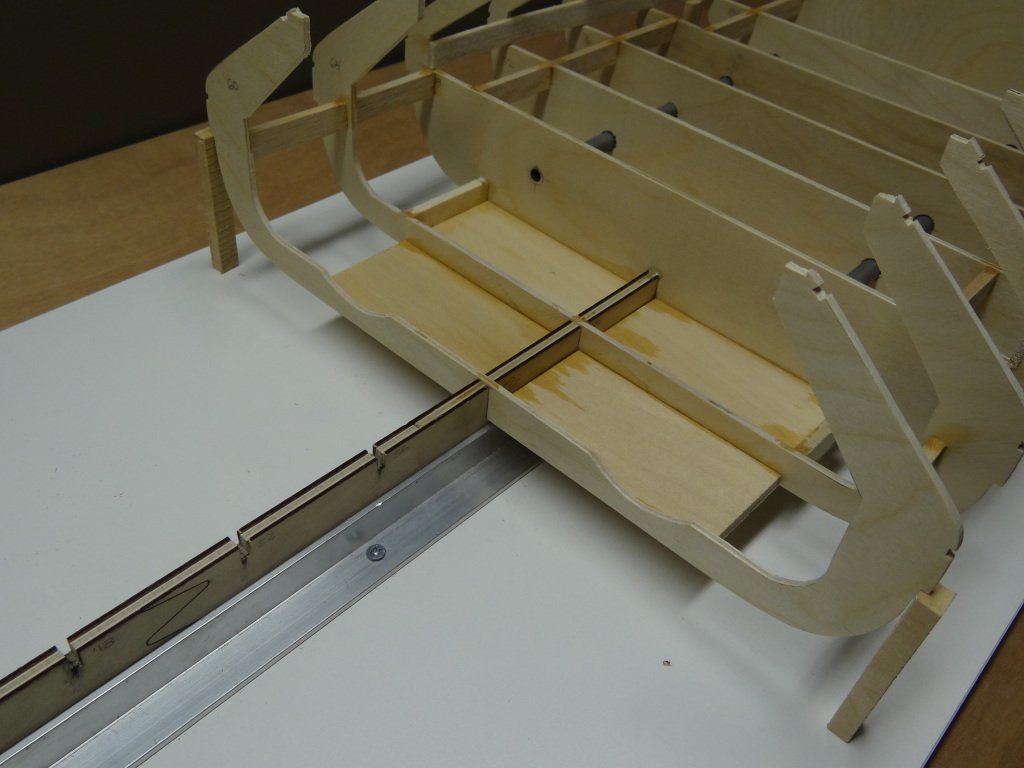

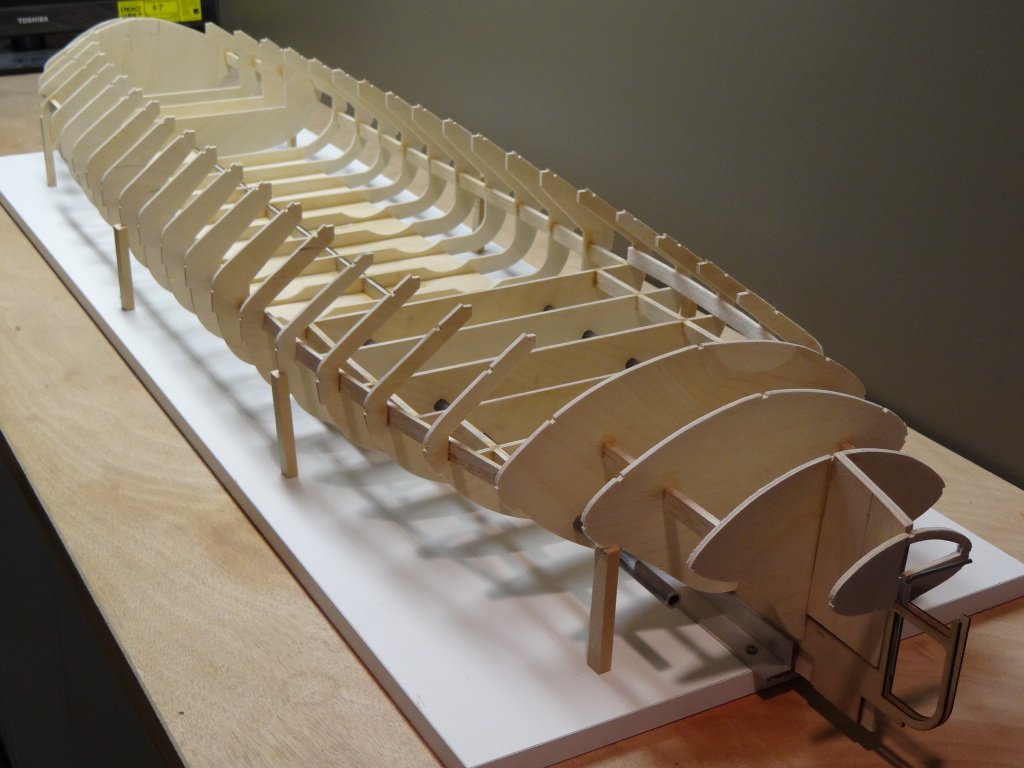

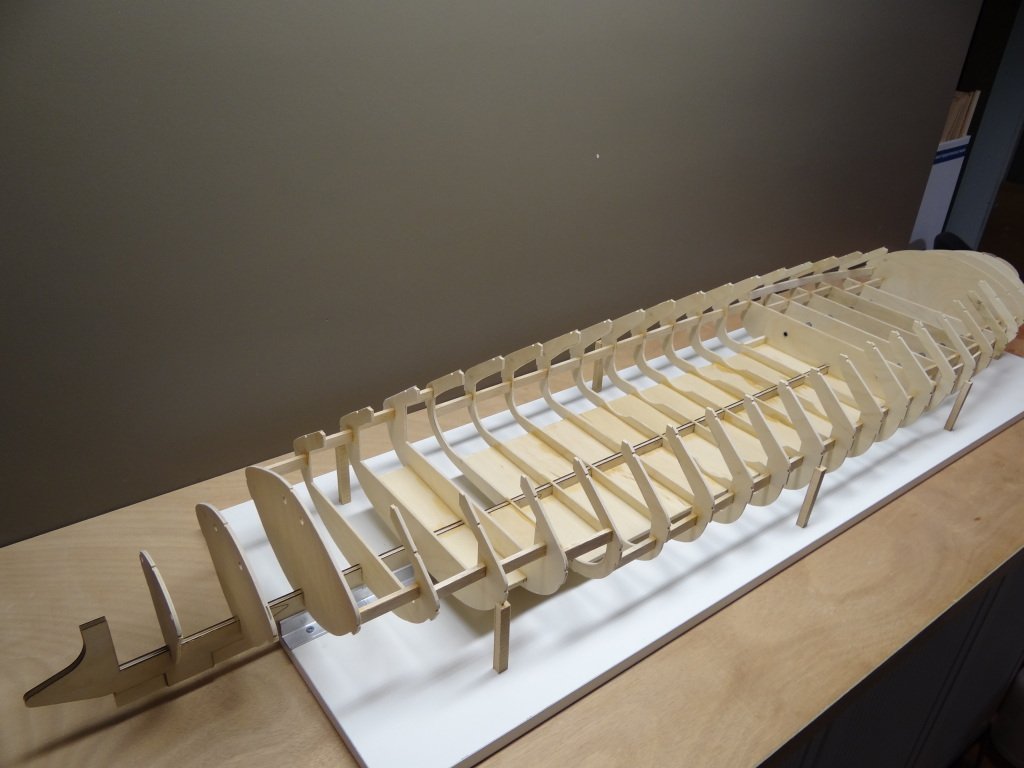

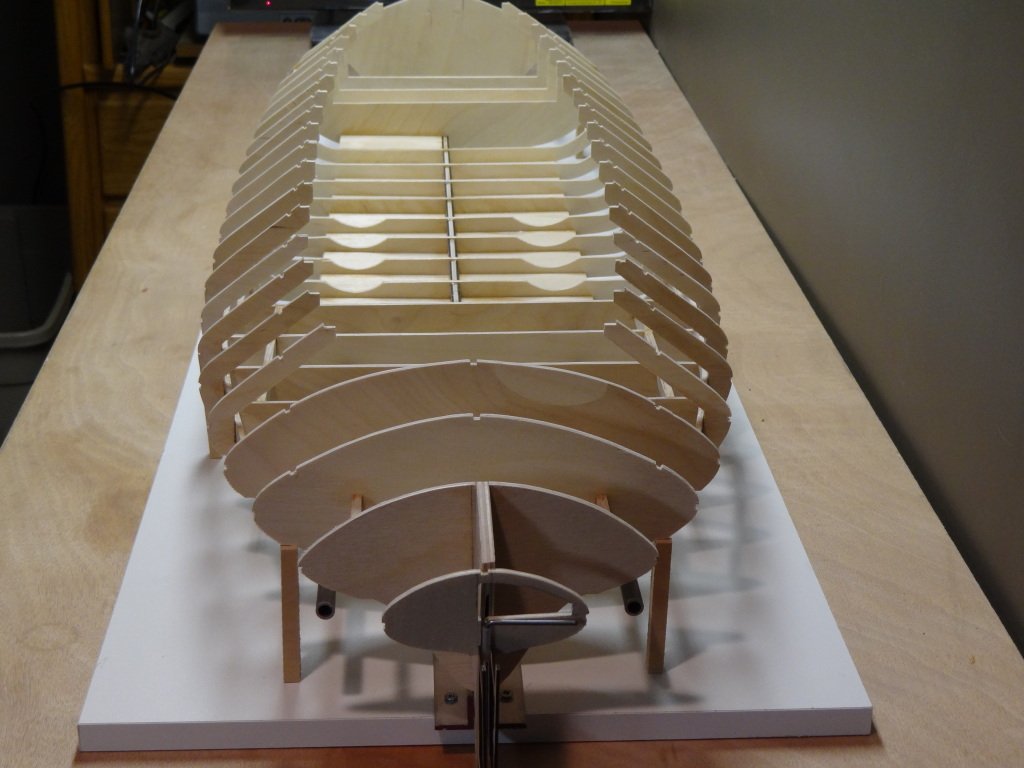

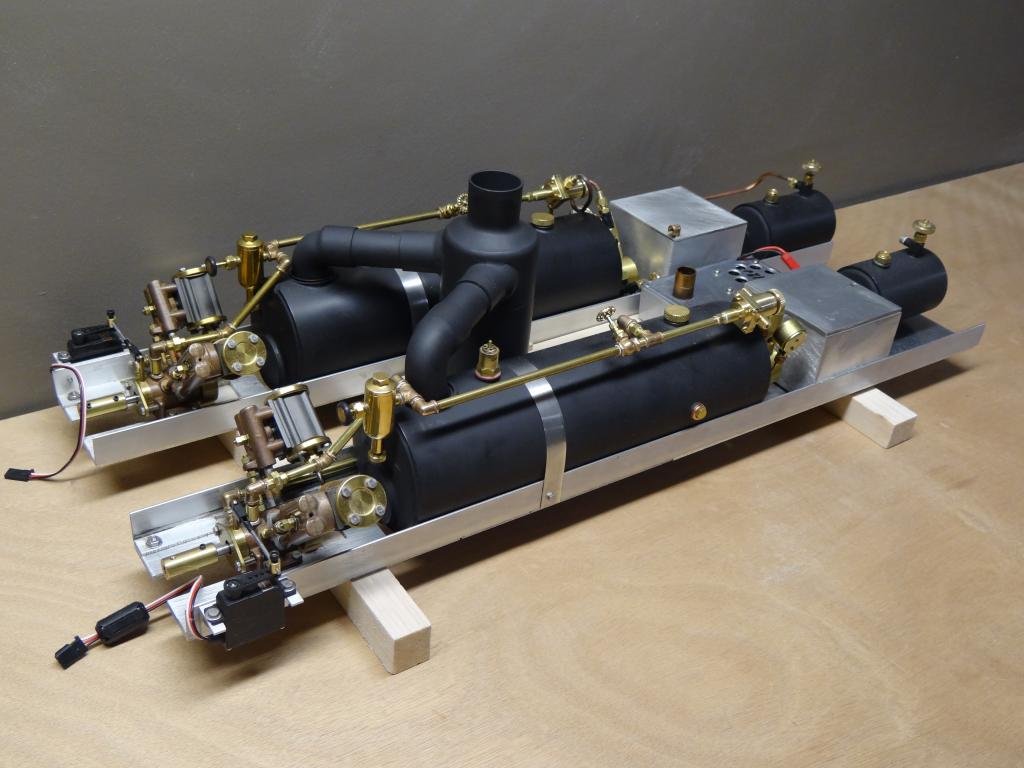

USS KEOKUK: The Ship that Could Have Sunk the Merrimac. Historical and Technical Overview A Brief Revisionist History Notional view of the engagement between USS Keokuk and CSS Virginia (aka Merrimac.) Painted by Patrick O'Brien. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper – March 29, 1862 (fictional account) Hampton Roads, Virginia, March 9, 1862 – from the deck of the U.S.S. Minnesota. In her first battle, our Navy’s new iron-hulled, steam-powered ram U.S.S. Keokuk, under Captain A.C. Rhind, has today engaged and sunk the iron-clad rebel ram Merrimac, which but the day before had destroyed our gallant warships Cumberland and Congress, with considerable loss of life, and inflicted slight damage upon the Minnesota, grounded during the battle. When Merrimac returned this morning with her consorts to resume her attack of the still-grounded Minnesota, she instead was met by the much smaller Keokuk, secreted from easy view behind the Minnesota during the night. Keokuk arrived in Hampton Roads but the evening beforehand, and was made ready to avenge the Cumberland and Congress at the first opportunity. As the unsuspecting Merrimac came within easy range of Minnesota, Keokuk emerged from behind her bows and had straight at Merrimac at a speed that startled both your writer and several members of Minnesota’s crew, standing nearby at their gun stations. Without doubt the rebels were equally startled, as almost immediately, Merrimac’s two lightly armed consorts steamed away back toward Sewell’s Point with all possible haste, leaving Merrimac alone to deal with this peculiar-looking, but clearly fast and nimble, new adversary. As she bore down on Merrimac, Keokuk turned out wide to her right in what appeared a maneuver to better position herself for a broadside ramming. Merrimac responded by trying to turn her bows to Keokuk and to move away from the shallow water on her right, but she was slow to answer her rudder. A few scant seconds later, Keokuk drove her five foot long solid iron ram into the left side of Merrimac. Coming together at such great speed as they were, there was a thunderous crash, much like a thunder-clap, that could be clearly heard by your writer one-half of a mile distant. Merrimac was mortally pierced on her left side, eight feet beneath her waterline and in a location that the Captains of both ships could doubtless clearly see each other’s faces from their pilot houses. Thus coupled, Keokuk remained at full ahead power to drive her ram deeper into Merrimac’s wooden hull, propelling the much larger ship sideways with seeming ease in an attempt to ground her. What few rebel guns that could be brought to bear in response fired only glancing blows, due to Keokuk’s all over rounded shape and iron skin. Some damage was done to the armor on the right side of the hull and turrets. The water churned frothy brown around the two ships, with Merrimac, like a fish on a spear, struggling to get away, and all the while Keokuk trying to drive Merrimac further into the shallows. Those gun crews on the left side of Minnesota with a clear shot, poured cannon fire into the right side of Merrimac. No rebel fire was directed at the Minnesota or Dragon during the battle. Keokuk then proceeded to engage Merrimac’s iron armor where it met the wooden lower hull, with her forward XI in. Dahlgren shell gun, firing solid iron shot of 165 pounds weight, from a distance of less than 40 feet. It took but two shots, into the area weakened by the ramming, to completely expose Merrimac’s gun deck through a hole so large that a sailor standing near to your writer exclaimed he, “could easily pass down the foredeck of Keokuk and into Merrimac walking straight up with my arms spread wide.” Likely fearing a third shot by an explosive shell would pierce her boilers or ignite her powder magazines, and being unable to maneuver off Keokuk’s ram, the rebel commander struck Merrimac’s colors just before eight o’clock this morning. Our gun-boat Dragon came alongside Merrimac and brought her surrendered officers and crew into captivity, transporting them to the Minnesota, much to the jubilation of the awaiting crew, who had suffered greatly at Merrimac’s hands the day before. In an act of humanity, the rebels were allowed to carry away the mortal remains of six shipmates, killed during the exchange of gunfire. Mercifully, the entire crew of Keokuk was spared all but some minor injuries. When Keokuk withdrew her ram, the now unattended Merrimac lost the buoyancy provided by the same, and exposed her inner hull to an onrush of sea water. She immediately began to settle by her forward left side, as Keokuk backed well down, anticipating an explosion. Instead, when the sea water reached Merrimac’s boilers, an immense white plume of steam billowed hundreds of feet into the morning sky. Resounding cheers of “HURRAH!” went up from the Minnesota and Dragon at this sight. It is believed that an explosion was avoided by failure of the rebels to attend to Merrimac’s fire boxes for the hour preceding. By nine and a half o’clock, all that remained above the surface of the now-calm Hampton Roads were the tops of her tattered smoke pipe, and the flagstaffs where the rebel colors had so proudly waved but one hour and a half beforehand. It is to be determined if Merrimac can be raised, repaired, and properly returned to Federal service, as to this day she remains a commissioned warship in the United States Navy, albeit briefly set to misdeeds by the rebels under the name “C.S.S. Virginia.” As of now there are three major warships resting on the bottom of Hampton Roads, all within easy sight of each other. Victorious Keokuk has been ordered to make all necessary repairs and proceed immediately to Charleston, South Carolina, to join in the blockade of that vital rebel port. It is known that at least one and possibly more rebel iron-clad batterys similar to Merrimac are being made ready there to attack our blockading ships. Keokuk will doubtless despatch these vessels with the same alacrity as Merrimac, should they be foolish enough to venture beyond the protection of the inner harbor shore batterys. As she appears to be one of the fastest warships in the U.S. Navy, she will likely be set to the additional task of seizing or sinking any blockade runners attempting to enter or leave the inner harbor. Navy Secretary Welles has ordered that all Federal Blockading Squadrons be equipped with at least one iron-hulled ram of Keokuk’s manner, at most possible haste, for further protection of wooden-hulled Federal ships from rebel iron-clad rams. Construction will be temporarily suspended on iron turreted batterys, including Monitor and Catskill, until all squadrons are suitably equipped with rams. As reported previously by your writer, plans are already underway to construct an iron-hulled ram of nearly four times the size of Keokuk. Back to Reality That is how the history books could have recorded USS Keokuk’s first engagement, had she been built a year earlier and sent to Hampton Roads instead of USS Monitor. But rather than receiving the praise heaped on Monitor for fighting to a draw with “Merrimac” – a contest that Keokuk would have won handily – barely 13 months later and just four months after sliding down the ways, Keokuk was at the bottom of Charleston’s Main Ship Channel after her first engagement, labeled a pariah. The fact is that Keokuk was a technological marvel for her time, equal – and even superior – to Monitor in many respects, and a purpose-built ship never used for her intended purpose. Even worse, she was immediately put into a situation that her designers explicitly warned against: placing her within range of heavy ordnance. On the technological downside, had Keokuk been built and sent to Hampton Roads instead of Monitor, “ram fever” would likely have replaced “monitor fever” in the Union Navy. Rams were nearly at an evolutionary dead-end in 1862 and became totally obsolete as soon as double wall iron hulls and large caliber, rapid firing, rifled guns appeared on nearly all capital ships. As such, by selecting the Keokuk ram design over turreted batteries like the Monitor - almost guaranteeing near term successes against the Confederate wooden-hulled iron clad rams - warship technology development would have been dealt a blow that could have set it back by several years. Launched on December 6, 1862 by J.S. Underhill Shipbuilders at 11th Street in New York City, Keokuk was from her conception incorrectly labeled and marketed to the Navy Department as a “battery”: which was essentially a floating fort. She was too lacking in armor and guns to serve as a battery. Keokuk was in fact a ram: probably the finest in the world at that time. Her singular task was to drive her five foot long integral iron ram into the side of a wooden-hulled ship and engage the weakened area pointblank with an 11 inch Dahlgren shell gun, one of the most powerful ship-borne guns available. Merrimac had already proven the effectiveness of an ironclad ram against wooden hulled warships by destroying the Cumberland and Congress and grounding the Minnesota, all in one engagement. But for all her initial successes, in comparison to Keokuk, Merrimac was grossly under- powered and under-armed. USS Keokuk being readied for launch at J.S. Underhill Shipbuilders. This is a surprisingly accurate depiction, down to the correct number of armor bands and the iron strakes into the conformal ram. Keokuk with her two independent 7 foot 6 inch diameter, 13 foot pitch, four-bladed screws; two, twin-cylinder 250 horsepower propulsion engines; and 9 foot draft, would have easily outmaneuvered Merrimac and rammed her, something that the single-cylinder engine / single-screw Monitor was unable to accomplish. Also, with half the speed and over twice the draft of Keokuk, Merrimac would have been unable to outrun Keokuk back up the Elizabeth River to the protection of Confederate shore batteries had she chosen not to fight. Following astern, Keokuk would have quickly disabled Merrimac’s stern gun, overtaken her, and destroyed Merrimac’s lightly protected rudder and propeller with her iron ram. Like Merrimac, her ram was Keokuk’s primary weapon. She was designed for frontal attacks with lightly armored flanks, where Merrimac was designed more like a battery to be used in broadside exchanges. Most importantly and unlike Merrimac, Keokuk’s ram was an integral part of the ship; with reinforced iron hull plates and reinforcing strakes extending into a ram shaped bow, with an iron core that was an extension of the stem post. In contrast, Merrimac’s ram was added on to the wooden hull and broke off inside the Cumberland the first time it was used. Keokuk would have been impervious to return fire while running in to ram, as what little frontal hull area that was exposed was a 20-foot long, innovative flooding compartment, separated from the rest of the ship by a watertight bulkhead, and designed to raise and lower her profile with steam-driven pumps that could maintain her at the desired trim regardless of how many additional holes were shot into the forward compartment. An elevated, sloping pilot house with only four small viewing slits facing forward ensured reasonable protection for the captain, pilot, and helmsman, unlike the muzzle-level, vertical-sided box arrangement on the Monitor. The only possible Achilles Heel when ramming would have been the shutters on the forward gun port, but the gun was just a secondary weapon to help speed up destroying the adversary. Keokuk’s first and only engagement came on the afternoon of April 7, 1863, when she joined Admiral Du Pont’s poorly conceived and executed attack on the heavily fortified port of Charleston, South Carolina, which had Fort Sumter, or “Sumpter” as its linch pin. The fleet was composed entirely of ironclads and in part was meant to show the superiority of these new, high-technology Federal weapons. But of the nine ships involved, only the flagship New Ironsides was specifically designed as a floating battery: a ship that could anchor and slug it out with shore batteries on an equal footing. The rest were designed to fight other ships. Equipped with fourteen 11 inch Dahlgren guns, and two Parrott rifles, had New Ironsides been able to run the gauntlet, accompanied by Keokuk or one or two monitors for protection from the ironclad rams Palmetto State and Chicora, and enter the inner harbor, she could have laid waste to the city of Charleston and possibly forced its surrender in the summer of 1863. As is, during a three month period in the fall of 1863, New Ironsides fired over 4,500 rounds of 11 inch shot and shell into the forts around Charleston: over half a million pounds of iron. The Union fleet line of battle, April 7, 1863, with Keokuk bringing up the rear and depicted much larger than she actually was: ¾ the length of USS Nahant immediately in front of her. Without land forces in support, the “attack” visually and tactically resembled a row of ducks in a shooting gallery. Instead, when the lead ship Weehawken with its fouled propeller and torpedo net stalled at the buoys of the floating barricade strung between Forts Sumter and Moultrie, the parade of ships broke formation and became a tangled mass fighting the tidal surge through the narrow mouth of Charleston Harbor. Caught in the crossfire between the surrounding forts with little room to maneuver around each other, and all the while fighting the tidal surge, it is estimated that within 30 minutes, over 3,500 Confederate artillery rounds were rained down on the fleet from a semi-circular ring of five forts. With forward progress to the inner harbor stalled by floating barricades and torpedoes, the Union fleet engaged in a disorganized shooting match with the forts: outnumbered in guns by a ratio of over 10:1. When Nahant, immediately in front of Keokuk, received a direct hit to the pilothouse roof that killed the pilot and wounded the helmsman, Keokuk was forced to maneuver around her while still staying within the narrow channel. New Ironsides had great difficulty maintaining headway due to the tide conditions and her extreme beam and marginal steering, and signaled the other ships to disregard her maneuvering. As the only ship that day with twin screws, Keokuk certainly coped better with the tidal surge, continuing around the single screw monitors and eventually finding herself in the number two position behind Weehawken. At that point she could proceed no further up the channel and found herself within 600 yards of both Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie, who barraged her with solid shot, hot shot, and rifled bolts for over half an hour. Keokuk's light armor was not designed to absorb such punishment, and her flanks and turrets were “completely riddled,” in the words of her captain, Commander Alexander C. Rhind, by the crossfire from the two forts. After receiving over 90 hits in less than 30 minutes, at least 19 of which penetrated the armor, many of them below the waterline and breaching the iron, single-walled hull, Keokuk was forced to withdraw out of range to the Main Ship Channel off Morris Island. The night was passed trying to save her, and it is likely that her biggest problem would have been dry coal for the boilers to keep the steam-driven pumps operating. Since she was a single-wall hull design, with the coal bunkers forming the outer compartments on the flanks of the ship, the bunkers were no doubt partially or completely flooded. As the coal chutes were low to the engine room deck, sea water would have been constantly pouring from the bunkers into the engine room. In the morning when the offshore winds picked up, the higher waves swamped her. She sank in about 20 feet of water 2,000 yards off the Morris Island lighthouse’s original location (the lighthouse had been torn down when the war began to deny the Federals its use for navigation.) Outside the effective range of Confederate shore batteries, the sinking was orderly, attended by a Union tug, and witnessed by many Southern soldiers and civilians on shore. There were reports of objects from the ship washing ashore “covered in blood,” which was most likely oil or grease, but certainly not blood. Largely due to the shallow water and her relatively flat bottom, Keokuk wound up on a fairly even keel with the tops of the turrets exposed at low tide. The wreck quickly filled with sand and the Union engineers declared Keokuk unrecoverable. As such, the blockading squadron did not put any emphasis on guarding the wreck site. This would prove unfortunate for the Union, as the two Dahlgren gun barrels were recovered by the Confederates and put to use in defense of Charleston. The Union experts had declared such a salvage operation to be impossible, at least until they read about it in the Charleston Mercury. A terse letter from Secretary Welles to Admiral DuPont clearly expressed his displeasure that DuPont’s squadron allowed this to happen. Of Keokuk’s 13 officers and 86 crewmen, 14 were wounded in the battle, most slightly, including Commander Rhind with a contusion to his leg from a piece of his ship breaking loose during the artillery barrage. One of the gun captains, Acting Ensign Mackintosh, later died from his wounds. He was one of only two fatalities sustained by the Union fleet, the other being Nahant’s pilot. Confederate forces sustained no casualties, due largely in part to Du Pont’s orders to the ships to direct all of their fire low, at the center embrasures of the forts. Keokuk’s Quartermaster Robert Anderson was awarded the Medal of Honor for shielding Commander Rhind from fragments when a shell hit the wheelhouse. April 8, 1863. Keokuk settles by the bows in the Main Ship Channel off Morris Island. Epilogue Had Union Navy decision makers been more realistic concerning Keokuk’s strengths and weaknesses, broadside exchanges would have been avoided and attacking forts would have been totally off the table. With 37 degree sloping sides, broadside hits from other ships would be at least partially deflected, but great care was still needed to protect her relatively thin composite wood and iron flanks from any shot at all. What Keokuk was specifically not designed for was exposure of her flanks to the plunging fire of heavy ordnance from shore batteries, which is exactly the position that she found herself in on April 7, 1863, caught in the crossfire of Forts Sumter and Moultrie. Most of the plunging shot would have hit the sloping armor of the turrets and hull casemates at or near perpendicular: one of the worst possible scenarios. Having been present during her construction, Commander Rhind well understood his ship’s vulnerabilities and tried to attack Sumter bows-on, using only the forward Dahlgren (the ram wouldn’t have done much damage to the fort!) Keokuk got off a total of three shots at Fort Sumter from the forward gun, which turned out to be the only shots she ever fired in active service. Her two cannon barrels, however, soldiered on after being recovered by the Confederates in a daring, near impossible operation, and were used in the defense of Charleston until its surrender. One is still on display in Charleston’s Battery Park. Keokuk’s untimely demise was no doubt helped along by the detailed descriptions of the ship published in the Scientific American, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and the New York Times in 1862 during her construction. So detailed in fact that in today’s world they would have been classified as at least SECRET and withheld from the public. By the time Keokuk arrived in Charleston, Confederate artillerymen already knew how thick her casemate armor was, the angle of its slope, and that it ended three feet nine inches below the waterline. All thanks to diligent Northern reporters, Confederate spies, and lackadaisical intelligence security by the Navy Department. In partial defense of Admiral DuPont, Secretaries Welles and Fox knew they were sending his fleet of ironclads on a suicide mission, ordering him to “reduce” the forts, with no illusions about destroying or capturing them. In addition, Du Pont was implicitly instructed to commit all of his ironclads to the attack. He was ordered that after the attack, he was to hold two ironclads in reserve (he chose his flagship New Ironsides and Weehawken) and that all other ironclads “fit to move” were to be sent immediately to New Orleans. These instructions were sent prior to the attack, so there was a clear understanding in Washington that things might end badly, which they did. Had Keokuk been held back from the doomed attack and kept in Charleston instead of Weehawken, she would have been available to deal with the rebel rams Palmetto State and Chicora, which had driven the Union blockading squadron into deeper water with their attacks on the Mercedita and Keystone State a few months earlier. It is interesting to speculate on the outcome of Keokuk engaging both Confederate ironclads at the same time, but she had the same advantages over them that she would have had with Merrimac: approximately twice the speed, half the draft, superior weaponry, and above all twin propulsion engines and screws, which was of critical importance for tactical maneuvering in the tidal surges of Charleston harbor. At least one of the Confederate ironclads most likely would have been rammed and sunk and Keokuk would have still been able to withdraw, with possible heavy damage from broadside fire. The Armor Controversy Keokuk is best remembered and, unjustly, vilified by many naval historians for her inadequate, “experimental” armor cladding (wasn’t all armor experimental at that time?) of alternating one inch wide and four inch deep strips of iron and yellow pine, covered by a 1.25 inch thick outer skin of overlapping, bolted iron plates. The figure, shown full size, shows what the casemate and cupola armor cross section would look like if you were to rotate the figure 37 degrees for the casemate or 20 degrees for the cupolas and look down the side of either. The Corbett drawing helps make this a little clearer. Now, was this armor design really inadequate for its intended purpose? Probably not. It should be remembered that Keokuk was designed as a ram, which would have limited her exposure to mostly frontal attacks and glancing blows to the hull side, or casemate, armor running down the length of the ship, not broadside. She would have also been exposed to much smaller caliber ship guns than what she experienced during the attack on Forts Sumter and Moultrie. She was not a large ship and was fitted with “as much armor as she could float,” according to her designer. In the end she still came in at 172 tons over the design weight of 688 tons, which added nine inches to her draft and almost totally rendered useless her innovative fore and aft flooding compartment feature. A vindication of her armor and design is that although she sustained over 90 hits in 30 minutes, many of them penetrating her armor cladding and breaching her single wall iron hull, only 14 of her crew of 99 were wounded, most of them only slightly but with one later dying from his wounds. She was also able to withdraw under her own power and be kept afloat overnight before finally being swamped and sunk by high waves in the morning. Whitney’s proposed design for Keokuk’s casemate and cupola armor, reproduced full size. None of my research indicates that something else was used, and this arrangement is shown on the Corbett drawing. The outer skin attachments could be interpreted as flush rivets, but all written descriptions found indicate that flush bolts and six-sided nuts were used throughout, as shown on the through-bolt. This could have been a modification to the proposed design. Based on the description published in Scientific American, Dec 20, 1862, the main deck was lightly armored with ½ inch iron plate laid directly on the iron hull frames, then 5 inch thick caulked wood planks followed by a 1 inch outer iron skin made up of two layers of ½ inch thick overlapping iron plates. Written and graphic interpretations abound on the “novel” armor concept used for the turrets and hull sides or “casemates” consisting of alternating 4 inch deep by 1 inch thick iron and 1-1/4 inch thick yellow pine wood strips, followed by a 1-1/4 inch thick outer skin composed of three layers of overlapping iron plates. According to the engineering drawing of 1863 by Keokuk’s Assistant Superintendent Charles Corbett, the alternating 1 inch thick iron and 1-1/4 inch thick wood strips were laid horizontally, or parallel to the waterline, on both the hull and turrets. All external attachments were performed with countersunk flush bolts, not domed rivets as often portrayed. The result would have been a relatively smooth outer iron skin with no raised rivets or bolt heads and a minimum of visible butt joints. That being said, the contemporary steel engraving of Keokuk on the ways prior to launching clearly, and presumed accurately, shows the vertical butt lines of the outer casemate and turret armor plates. This however may be just representing the tonal variations of the blackened iron plates, which were probably left unpainted. Historical Footnote: Robert Smalls The “pilot” on Keokuk at the time of her loss was Robert Smalls, a former slave who had piloted ships around Charleston Harbor and knew the area well. In 1862, Smalls was serving as pilot of CSS Planter, a small, armed, sidewheeler cargo ship that operated around Charleston, supporting the local forts. Technically, slaves could not be pilots, but they operated as such under the supervision of white officers. On May 12 th , when the white crew went ashore, Smalls and seven (or three, depending on which report you read,) slave crewmembers, along with their families, got underway and sailed the Planter past the five forts guarding the entrance to Charleston. When out of range, they hauled down the Confederate “Stainless,” hoisted a white flag, and surrendered Planter to the Union blockading fleet. Along with the ship and cargo, and even more valuable, Smalls surrendered the code book of the Confederate secret signals, and the placement of mines and torpedoes in and around Charleston Harbor. Smalls became a celebrity in the North, where he met with President Lincoln. His exploit was credited in part with the North more actively recruiting black men for the Union Army and Navy. Smalls went on to become the first black captain of a US Navy ship: USS Planter - the same ship that he had delivered into Federal hands. He was made captain following an action where Planter was caught in a crossfire between Folly and Morris Island and the white officer in command decided to surrender. Fearing that he and the other black crewmen would be summarily executed according to the Confederate proclamation concerning blacks serving for the Union, Smalls took command of Planter and avoided capture, while the white captain hid in the coal bunker. For that action, Smalls was awarded command of the ship and the previous captain was dismissed from the Navy by Admiral Du Pont for cowardice and desertion. Robert Smalls and CSS / USS Planter from the Harper’s Weekly article of June 14, 1862. After the war, Smalls served in the US House of Representatives between 1875 and 1887, and eventually owned and lived in the house where he and his mother once served as slaves. While Smalls and Keokuk were called on to mark the approach into the harbor before the attack, there is no logical explanation for why Smalls was piloting the ship at the back of the formation on April 7, instead of the one guiding the fleet into Charleston Harbor, aside perhaps because of the color of his skin. It should also be noted that despite the clearly valuable knowledge he provided about Charleston’s channels and defenses, he is only vaguely referred to in official documents as “with help from others.” Smalls might have changed history and the course of the war that day had he been piloting Weehawken instead of Keokuk. Documented Technical Description of USS Keokuk The following information was collected from contemporary published sources that were reasonably consistent in their details and can be cross-checked to the Corbett drawing. Derived information is discussed in a later section. Length (including the 5 foot integral ram) – 159 feet 6 inches Maximum Beam – 36 feet 3 inches Draft as designed – 8 feet 6 inches Draft as launched and fully outfitted – 9 feet 3 inches Moulded Depth – 13 feet 6 inches Design Weight – 688 tons Weight as Launched and fully outfitted – 860 tons (172 tons over design weight) Hull Construction Frames (100) – Iron 4 inches deep by 1 inch (or ¾ inch depending on the reference cited) thick with integral deck and platform braces; 18 inches between centers; frames included integral deck beams and bracing Inner iron skin attached to the frames by multiple U-shaped brackets, bolted to the skin on both sides of each frame Inner and Outer Skins – overlapping rolled sheet iron of primarily ½ inch thicknesses; outer casemate armor plates 36 inches wide laid vertically and butted together Five keelsons (no keel), but with a thicker center keelson Countersunk flush bolted attachment of the outer iron plates First 20 feet fore and aft were completely open flooding compartments separated from the rest of the ship by water-tight bulkheads Water-tight bulkhead at forward end of engine room; water-tight half-bulkhead at the aft end up to the first platform Nine stiffening strakes on the hull below the waterline, made from 36 inch wide iron plates – believed to be ½ inch thick Armor Main Deck – two layers of ½ inch overlapping iron plates laid over 5 inch caulked yellow pine planks; less than 1 inch of camber and no sheer to the main deck per the Corbett drawing Turrets and Hull Casemates – alternating 1 inch thick by 4 inch deep iron and 1-1/4 inch thick by 4 inch deep yellow pine strips; gum rubber applied between the strips for corrosion protection. Three layers of overlapping ½ inch armor plate applied on top of the strips All armor plates secured with 1-1/8 inch diameter countersunk bolts at 12 inch spacing on the edges; bolts secured internally with six-sided nuts Steam Engines – Nine total Four Propulsion – a pair of twin-cylinder 250 horse-power steam engines built by Wheeler of New York; 23 inch bore and 20 inch stroke (counts as four or the nine engines) Four Pumping – two for flooding and emptying the fore and aft flooding compartments and two for providing water to the boilers One Blowing – for running the air circulating blowers Boilers and Steam Chest Two 12 feet long by 6 feet diameter boilers; two fire boxes per boiler, forming cradles for the boilers One 14 feet long by 2.7 feet diameter steam chest cradled between the boilers Armament – two 11 inch Dahlgren Shell Guns on modified wooden slide carriages (shortened and rounded on both ends to fit in the turrets); gun runout / recoil travel reduced by about one third and standard powder charges reduced accordingly Crew – 13 officers and 86 men Unique Features Five foot long, smoothly faired, integral iron ram incorporated as an extension of the ship’s stem and center keelson, which would more evenly distribute the shock from impact than would an attached ram All iron construction with the exception of wood used for decks, filler between armor slats, and interior joiner bulkheads and doors; wood areas covered by iron were yellow pine and exposed horizontal wood areas, e.g., the gun and internal decks, were white oak Fore and aft flooding compartments to lower the ship’s profile for combat Toilets for crew and officers Some Inaccuracies Reported in Contemporary Sources It is always risky to point to a published statement and say, “That’s wrong.” But the following are just plain wrong. It appears they got picked up from contemporary newspaper articles (primarily the New York Times) and / or may just be misinterpreted from information provided. The only reason this is significant is because modern day reasearchers have perpetuated these misconceptions in print, illustrations, and models: “Single propeller” or “screw” – actually twin screws “Round bottom” – was in fact almost dead flat “Keel” – used five keelsons; no keel “11 foot Dahlgrens” - THAT would be impressive! Actually 11 inch Dahlgrens “Two guns in each tower” – two guns total with one in each tower “Three boilers” – original Whitney design called for three boilers; final design consisted of two boilers and a large steam chest between them “Turtleback” – sides actually flat for over 2/3’s of the hull length and less than 1 inch camber to the main deck with a sharp knuckle at the deck edge. Only the extreme bow and stern areas could be considered “turtleback” “Wooden deck” – yes, but covered with a double layer of iron plate Model Planning and Design Why? I have been asked that question a lot. What started out as morbid curiosity evolved over 14 years into what some friends and family members describe as an obsession. I was first introduced to Keokuk by William Blackmore of Cottage Industry Models and his 1/96 resin kit of Keokuk. At that point I knew nothing about the ship or its history, but I just had to build the model, because it was so UGLY! However, the more I learned about the ship and its history, the more intrigued I became. Initially I was in the same camp as other casual Civil War naval historians: Keokuk was an inferior design, which is why it got sunk on its first engagement. But after many years of research, I came to believe that instead, she was a technological marvel that could have served as the poster child for bad marketing and even worse military tactics. The Model The model is in 1/32 scale, giving an overall length of just under 60 inches and providing just enough internal volume to allow “kind-of-scale” twin engine/ twin cylinder/ twin boiler, live steam propulsion. Live steam presents its own set of unique challenges: it’s messy, cantankerous, potentially dangerous, expensive, provides shorter run times than electric, and heavily impacts construction decisions, e.g., forget about using plastic or resin parts! And then as the final insult, it doesn’t smoke or sound like full scale steam, so for full scale effect you still have to add electric smoke and sound units, just as if you were powering the model with electric motors. But when I finished the first propulsion unit, fired up the boiler, built up pressure, cracked open the main steam valve and brought the engine to life, something magical happened. Information Sources The hull lines were taken off the original 1/48 scale Whitney drawings and recreated in CAD at 1/32 scale. This required some fudging because a large piece of the cross section area is torn and partially missing on the original. https://docs.google.com/drawings/d/sikB5zpl1WEpvd4XWlcj3Yg/image?w=644&h=280&rev=1&ac=1&parent=1i4Ya4yvGiBa-8UZZ6oeN6jwLY7jYeK57dDpQcUB42TM Surviving Whitney Design Drawing with Damaged Area. This design was presented to the Navy as the "Whitney Battery.) Aside from the hull lines, the original drawings or “Booklet of General Plans” are not of much use: for example, they show a third cupola that combined the pilothouse and the smoke pipe. I don’t even want to think what it would have been like in the pilothouse on blockading duty in Charleston Harbor in the summer! They also show three boilers, props and shafts the wrong diameter and length, incorrect strut arrangement, hatches in the wrong locations, and far too many deck lights for a warship. Also during model construction it became apparent that the hull lines themselves were off, as they did not match the plan view on the same sheet in the stern area. This was largely in part because the cross sections were not drawn as “projections” off the hull lines: they were put on the drawing separately and with no apparent cross check of the profile or hull lines, or “lifts.” As an example, taking beam measurements off the cross sections and comparing to the profile and hull lines, I found discrepancies of almost 12 full scale inches in some places. This created a lot of problems during construction. I also found on my first model that the full scale prop shafts must have been moved down and out, as when I tried to install the scale diameter props, they were banging against the hull. I presume that like the guns (discussed later), somewhere in the design development a decision was made to go with larger props, which was not reflected on the original drawing. The final “as launched” design placed the pilot house at the rear of the forward gun turret. I went with conventional wooden construction of the hull as opposed to the all metal “Erector Set” approach used on the original. Because of that, the model is 100% scale outline, but bears no resemblance to how the actual ship was built, aside from locating the 25 frames in the same positions as the corresponding 25 on the actual ship. Most of the details on this model were derived from the “As Built” drawing done by Charles H. Corbett, who was Keokuk’s Assistant Superintendent during construction and no doubt created the drawing from life. The drawing was done in 1/48 scale, still exists, and is owned by the New York Historical Society. Unfortunately, providing only a right inboard profile, four half-cross sections, and an interior plan view, it raises almost as many questions as it answers. That being said, to me it epitomizes a unique combination of fine art, historical significance, and technical illustration. Corbett’s beautiful and ornate rendering of Keokuk, dated 1863. As her Assistant Superintendent, one can only imagine how painful it was for him to add the riband, “Delivrd Feb 24 th 1863 - Lost Apr 8 th 1863.” ©New York Historical Society. Used with permission. I purchased a digital copy of the original from the NYHS in the highest available resolution, had it enlarged to 1/32 scale, and used that to take the majority of my measurements for the model. To see this image in a reduced-size book format – even in color – really doesn’t do it justice. For example, all of the deck light locations are shown as faint dashed lines that are only clearly visible when the drawing is viewed at actual size or larger. Fortunately, several original Keokuk detailed “as-built” engineering drawings also exist, including the props, prop shafts, struts, casemate and turret plating arrangements, and the gun deck arrangements. Hull plating runs required some study of contemporary shipbuilding and ironwork practices and “shipbuilding forensics”, aided by my working in a military shipyard for several years. I knew from the historical records that Keokuk used several layers of thin rolled iron plates, which would have most likely been rolled to a maximum width of 36 inches in lengths up to 180 inches: about the upper size limit that iron factories could produce at the time. Larger, thicker plates like those used on New Ironsides were generally steam hammered. As a rule of thumb, thicker plates were riveted and thinner plates were either screwed or bolted together to create laminations, although there was a multitude of variations and combinations used on the various ironclads. The original ship had 100 frames set 18 inches between centers, consistent with the 36 inch maximum width of available iron plate and measurements of the outside casemate armor bands. The frames included integral iron deck crossbeams, unlike most of the monitors, which stayed with wooden crossbeams. The inner plates were attached to the frames and each other by U-shaped clamps, secured by bolts on each side of the frame. On the model I chose to go with 25 frames set 2-1/4 inches apart. These line up with the major frames on the Whitney hull drawing, e.g., the three water tight bulkheads and the aft half-bulkhead of the engine room. I had a set of frames and keel sections laser cut off the CAD drawings at scale thickness, which came out to roughly 1/16”. These proved far too flimsy to build a functioning live steam model on, so I used them as patterns and hand cut a new set of frames out of 1/8 inch marine plywood. I was then ready to proceed with assembly. Model Construction Introduction This is not meant to be a tutorial on how to build a radio controlled, steam powered model ship, or a testimonial for modeling products: I am simply describing what I did and what I used. Your results may vary! Also, I wanted to keep this model’s appearance as accurate and “historically pure” as possible, with a minimum of “techno guesswork.” To that end, I avoided adding features that aren’t documented on the Corbett drawing. Believe me, the urge was there to dress up the interior with obvious necessities like lights and a chart table and chair in the pilot house, but I successfully fought it. If I come across additional information that indicates certain features indeed existed, I will add them. Hull Framing First I made a building board from a piece of 48 inch long x ¾ inch particle board and two 48 inch lengths of heavy wall angled aluminum, tightly fitted to the keel and screwed to the board to keep the keel straight during construction, but still easily removable (figure H-1.) The board was 48 inches long because that’s what I had sitting around, and hanging 6 inches of hull off each end didn’t present any serious problems, plus I could slide the keel back and forth in the vise as needed. I use particle board because it tends to lay flat and not bow like some wood is prone to do. I personally would never consider building a framed ship model without clamping the keel in some kind of vise, although I see it done all the time, often with a lot of success. Other times, not so much. I started framing the hull by assembling a multi-piece keel, which had additional depth on the bottom to secure it in the keel vise while still leaving room for the outer planking. This extension would be cut away after the hull was planked and glassed. The keel consisted of two 1/16 inch plywood outer units and a center core of 1/8 inch plywood, which ended roughly at the forward and aft perpendiculars. I made the center short because the ship tapers at the bow into the ram and at the stern into the rudder guard. This way I could just pull the two outside keel pieces together and fill them with epoxy to make them rigid. I can testify that after doing battle with the ceiling, walls, and shop lights many times during construction, that integral ram is highly effective! Keel installed on the building board. Four foot ruler in foreground. I prefer to build a model around its propulsion system, rather than build a hull and hope for the best when it comes time to install the running gear. So starting at the stern, I built up the after hull frames around the scale outside diameter prop shaft housings, focusing on the two frames where the housings enter the engine room and exit the hull. Aside from a straight keel, getting the prop shafts true to each other and square is the best way to ensure a twist-free, straight tracking hull. Note that the constant-height, lower edge of the armor belt on each frame provided a nice ledge for vertical supports, ensuring that the frames were level. Supporting the hull frames with constant length supports during construction is another handy way to avoid building any twist into the hull. I made sure the supports were all identical by setting the fence on my saw and cutting them all at once. Prop shaft housings installed in the aft frames with frame supports in place. Working my way forward, I installed all the frames on the keel. Note the 1/8 inch plywood “false bottom” pieces that extend from each side of the keel to the knuckle on the bottom of the hull. These help stiffen and straighten the hull as well as support the weight of the propulsion units. Also note the cutouts in the frames at the boiler locations to get the boilers as low as possible. This is not only to lower the center of gravity but to keep the exhaust trunking below the main deck. Keokuk’s moulded depth was only 13 feet 6 inches, which scales out to an extremely cramped 5 inches of vertical space, especially when using 3 inch diameter boilers. I also installed temporary balsa spacers between the frames to keep them square on the keel and to each other. As with the vertical supports, I set the fence on my saw and cut all the spacers at once to ensure they were identical. Since all of the frames were equally spaced, it there was a spacer that was too short or long, I knew the problem was in the relationship of the frames to each other. Note the stiffeners added to the bottom of the hull. Boilers are heavy! I continued working my way forward. Also note the cutouts for the boilers, which needed to be as low in the hull as possible. In the bows-on photo below, you can just make out the holes in the first three frames for the hawsepipes. These were angled up and into the focsle area where the anchor chains were connected to an internal capstan mounted to the overhead. I wanted the hawsepipes to be scale, rather than just drilling a couple holes in the bow for the anchor chains later and hoping they were in the right places and symmetrical. The whole operation was probably more trouble than it was worth, but I like the end results. More on that later. The framing is complete. The last couple frames are left loose while I fiddled with the superficial rudder linkage. I planned to drive Keokuk like a bulldozer because the rudder is so small as to be useless. We shall see during sea trials. Propulsion Units Before proceeding with finishing the hull, it was a good idea to make sure that everything that went inside actually fit! I built the propulsion units as two independent, modular assemblies on aluminum trays made from 1/8 inch thick plate and ¾ inch angles, bolted together. I made the units separate so they can be removed relatively easily by removing the exhaust system and return steam lines, disconnecting the prop shaft couplers and servo leads, and sliding each tray inboard for removal, because they will not lift straight out due to the hull’s extreme tumblehome. The trays are held in place by gravity, a few shims, and the spacer between the trays that the exhaust system sits on. The custom MacSteam boilers are 3 inches in diameter by 10 inches long and fired by appropriately sized MacSteam butane burners and tanks. The boilers are as large as possible to get a decent run time without having to include onboard water tanks and pumps. They are completely independent of each other, can be used in other models together or independently, and are environmentally friendly. I also cut large rectangular holes in the trays so the bottoms of the boilers are actually lower than the bottoms of the trays, as I was (rightfully!) concerned about vertical clearance between the exhaust trunking and deck. The engines are twin oscillating vee’s, available as fully machined kits from PM Research. These are one of the best deals to be had in model steam, as they are compact, self-starting, and include throttle and reverse at a relatively inexpensive price. They are also primarily brass, bronze, nylon, and stainless steel, which eliminates a lot of corrosion problems. On the downside, they leak and throw a lot of spray and steam oil, so there is some cleanup to be done after running them. I made sure that all internal wood is protected from the oil spray with a heavy coat of finishing resin followed by layers of high heat paint. I test ran both propulsion units outside the hull to debug them and found that with judicious steam management using pressure regulators I could get 1+ hour run times at various power settings just using the water in the boilers. Therefore, if I keep operating times to 45 minutes, I will be safe. Running the water down too far can damage the boilers. Once I had test run both units, I put them in the hull for a trial fit. This helped me determine where I needed to remove wood to provide clearance for the piping and smoke pipe trunking. Test fitting the propulsion units inside the hull. Not a whole lot of space! I like using solid couplers to connect engines to prop shafts (figure P-3) because it forces me to ensure that everything is lined up perfectly. Plus I’ve never seen a flexible coupler on a real drive train! This required ensuring that the propulsion units were properly shimmed to line up exactly with the prop shafts. I checked this by attaching the coupler to each engine shaft, sticking the prop shaft in the other end of the coupler, and adjusting shims under the propulsion unit until the prop shaft turned freely inside the coupler. Thanks to careful alignment and the quality of the custom Prop Shop propellers, the engines can be run at full speed with virtually no vibration. I won’t know until sea trials, but I assume that I will need no more than half power to operate at scale speeds. Figure P-3. Test fitting the solid coupler connecting the engine and prop shaft. On final installation, the tray is flush against the bulkhead. Next came fiddling with the exhaust trunking to get it to line up with the scale location of the smokestack (figure P-4.) I used standard plumbing copper fittings for the trunking; available at most hardware stores. I had lots of room under the fitting where the boiler exhausts enter the uptake, so I decided to use that as a chamber to create black smoke. More on that later. Figure P-4. Propulsion units and exhaust trunking being test fitted. Once I had the everything test fitted and shimmed, I removed the propulsion units and finished detailing them (figure P-5). Detailing included cleaning, painting, and modifying the engine piping and oiler locations to clear the aft gun deck without having to cut holes in it. I used Rustoleum High Heat black spray paint; The “Ultra” version proved too glossy and the regular too flat for the look I was after. So I experimented by spraying the parts first with Ultra (which has higher heat resistance) and then over painting with the regular flat black. Once the paint was “cooked” on and wiped down a bit, it has the semi-gloss effect I was looking for and appears to be quite durable. To extend run time, I reduced the diameter of the steam and gas lines and added Bix boiler pressure regulators. By regulating the boiler pressure to idle the burner at 20 psi, the safe run time on one fill of water went from approximately 30 minutes to 60 minutes without the annoyance of safety valves blowing if I sit at idle too long. I have designed in the capablity to refill the gas tanks and boilers while under pressure but I am leaving off the fittings for initial sea trials. Figure P-5. Propulsion units and exhaust trunking detailed, test run, and awaiting final installation. Hull Finishing I started out by blocking between the frames with ½ inch thick balsa planks to make the engine modules are test fitted into the hull. I made them independent so they could be use in pairs or singly for other projects. They went through a couple design transformation and these were the final version. The boxes at the front collect the steam as it leaves the engines and condenses. This is a green model with no overboard discharge.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.