-

Posts

2,176 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by uss frolick

-

Stoves/Ovens on ships in the 1600s and Onward

uss frolick replied to acaron41120's topic in Nautical/Naval History

They're not working, (again) and the normal, edit-post tab doesn't appear either ... drat. -

Stoves/Ovens on ships in the 1600s and Onward

uss frolick replied to acaron41120's topic in Nautical/Naval History

The Wasa provides some answers. Her stove was essentially a brick lined wooden box. The archeological drawings: https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50525123216_c223556a67_b.jpg[url=https://flic.kr/p/2jYJsS5]0[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/165793220@N04/]Stephen Duffy[/url], on Flickr [url=https://flic.kr/p/2jYKieb][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50525285912_538a1c1d36_h.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2jYKieb]0-1[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/165793220@N04/]Stephen Duffy[/url], on Flickr Edit by MTaylor.. Sorry.. I tried to fiddle with the first one and no joy. Best way is download the photo to your HDD and then use the image attachment (paperclip - lower left hand side). -

Bill Romero told our club a long time ago that the author did not obtain permission to reproduce many of the plans shown in his book, and got sued by multiple persons soon after publication. Sad. Pays to be careful ...

- 4 replies

-

- Milton roth

- lusci

- (and 4 more)

-

Actually, a third Swan-Class sloop fell to the Americans! HMS Thorn was taken by USF Deane (12-pounders) and USF Boston (a mixture of 12-pounders and 9-pounders) . Very few particulars are available about this fight. From the Wiki page on the Frigate Deane: Under the command of Captain Samuel Nicholson of the Continental Navy, Deane sailed from Boston 14 January 1779 with Alliance for a cruise in the West Indies. She returned to Philadelphia 17 April with one prize, the armed ship Viper. On 29 July she joined with USS Boston and two ships of the Virginia Navy guarding a convoy of merchantmen out to sea and continuing on for a five-week cruise which netted eight prizes, including four privateers, the packet Sandwich, and the sloop-of-war HMS Thorn. The frigates arrived at Boston 6 September with 250 prisoners after one of the most notable cruises of the Continental Navy. During the winter and early spring of 1781 Deane cruised with Confederacy and Saratoga in the West Indies. In May, Lloyd's List reported that the rebel frigates Dean and Protector had captured John, Ashburner, master, from Lancaster to St. Kitts, and a ship sailing from Glasgow to Jamaica with 90-0 barrels of beef and a quantity of dry goods, and had taken them into Martinique.[1] Deane again cruised with Confederacy and Saratoga in the West Indies in 1782, capturing four prizes. In April 1782 she captured the cutter HMS Jackal. After two more cruises in the Caribbean, one in September 1782 and the other in 1783, she was renamed Hague in September 1782 (perhaps because of false accusation against Deane that was current at the time). According to Wiki, HMS Thorn became a yankee privateer, was recaptured, and survived until 1816, making her the longest lasting of the Swans (so far)! HMS Thorn (1779) was a 14-gun sloop launched in 1779 that two American frigates, USS Deane and USS Boston captured on 25 August 1779. She became an American privateer with a number of successful engagements and prizes to her name. Arethusa captured her on 20 August 1782.[3] She then returned to service in the Royal Navy, serving until 1816 when she was sold.

-

Savage wasn't the only Swan Class Sloop to tangle with an American. In 1781, the Atalanta was taken by the Continental Frigate Alliance, a ship probably similar the later Essex, which had been produced by the same shipbuilder family, but unlike the Essex, the Alliance was armed with 28 long French 18-pounders that had been earmarked for the lower deck of the lost Bon Homme Richard. HMS Atalanta was sailing in company with another, smaller British sloop of war, HMS Trepassy, both having batteries of only 6-pounders. From Wiki: "During a tempest on the 17th, lightning shattered the frigate's main topmast and carried away her main yard while damaging her foremast and injuring almost a score of men. Jury-rigged repairs had been completed when Barry observed two vessels approaching him from windward 10 days later but his ship was still far from her best fighting trim. The two strangers kept pace with Alliance roughly a league off her starboard beam. At first dawn, the unknown ships hoisted British colors and prepared for battle. Although all three ships were almost completely becalmed, the American drifted within hailing distance of the largest British vessel about an hour before noon; Barry learned that it was the sloop of war HMS Atalanta. Her smaller consort proved to be Trepassey, also a sloop of war. The American captain then identified his own vessel and invited Atalanta's commanding officer to surrender. A few moments later, Barry opened the inevitable battle with a broadside. The sloops immediately pulled out of field of fire of the frigate's broadsides and took positions aft of their foe where their guns could pound her with near impunity In the motionless air, Alliance – too large to be propelled by sweeps – was powerless to maneuver. A grapeshot hit Barry's left shoulder, seriously wounding him, but he continued to direct the fighting until loss of blood almost robbed him of consciousness. Lieutenant Hoystead Hacker, the frigate's executive officer, took command as Barry was carried to the cockpit for treatment. Hacker fought the ship with valor and determination until her inability to maneuver out of her relatively defenseless position prompted him to seek Barry's permission to surrender. Indignantly, Barry refused to allow this and asked to be brought back on deck to resume command. Inspired by Barry's zeal, Hacker returned to the fray. Then a wind sprang up and restored Alliance's steerage way, enabling her to bring her battery back into action. Two devastating broadsides knocked Trepassey out of the fight. Another broadside forced Atalanta to strike, ending the bloody affair. The next day, while carpenters labored to repair all three ships, Barry transferred all of his prisoners to Trepassey which – as a cartel ship – would carry them to St. John's, Newfoundland, to be exchanged for American prisoners. HMS Charlestown recaptured Atalanta in June and sent her into Halifax. Temporary repairs to Atalanta ended on the last day of May, and the prize got underway for Boston. After more patching her battered hull and rigging, Alliance set out the next day and reached Boston on 6 June. "

-

Preserved Killick: "Which I think it's one of the Doctor's high words, a physician he is, with a fine wig, and a silver cane! He wouldn't look at you on land for under five guinies, I'm told ..." Barrett Bonden: "The captain urges us to go forth upon the enemy's deck, I do believe, and convince those fat-arsed, dutch-built buggers of the error of their ways." Killick, "Which then, we shall endeavor to persevere ... Hand me that-there boarding-axe ..."

-

American Captain Geddes: “Huzzah, vicissitude her lads!” I thought about the figurehead too, since no plan is known to survive. But the term ‘savage’ was frequently used at that time to describe the North American Indians, so maybe her head resembled the Essex’s hatchet wielding warrior or the Rattlesnakes knife bearing brother! How ironic if true! since she lasted at least until 1803, when she was finally hulked, that would make her older than even the Fly, which sank in a storm off Canada in 1802! I wonder if either Savage or Fly was ever rearmed with carronades ..,

-

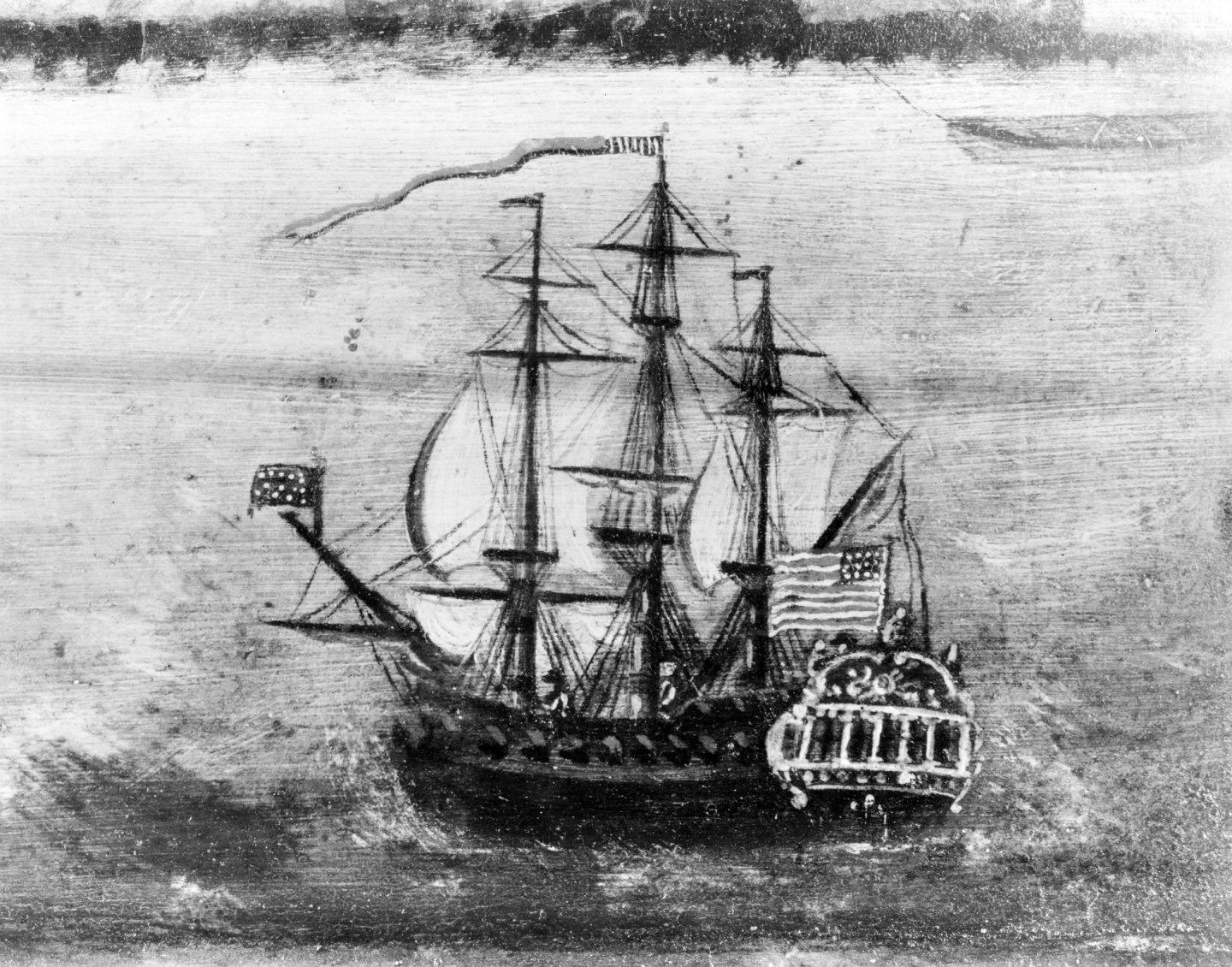

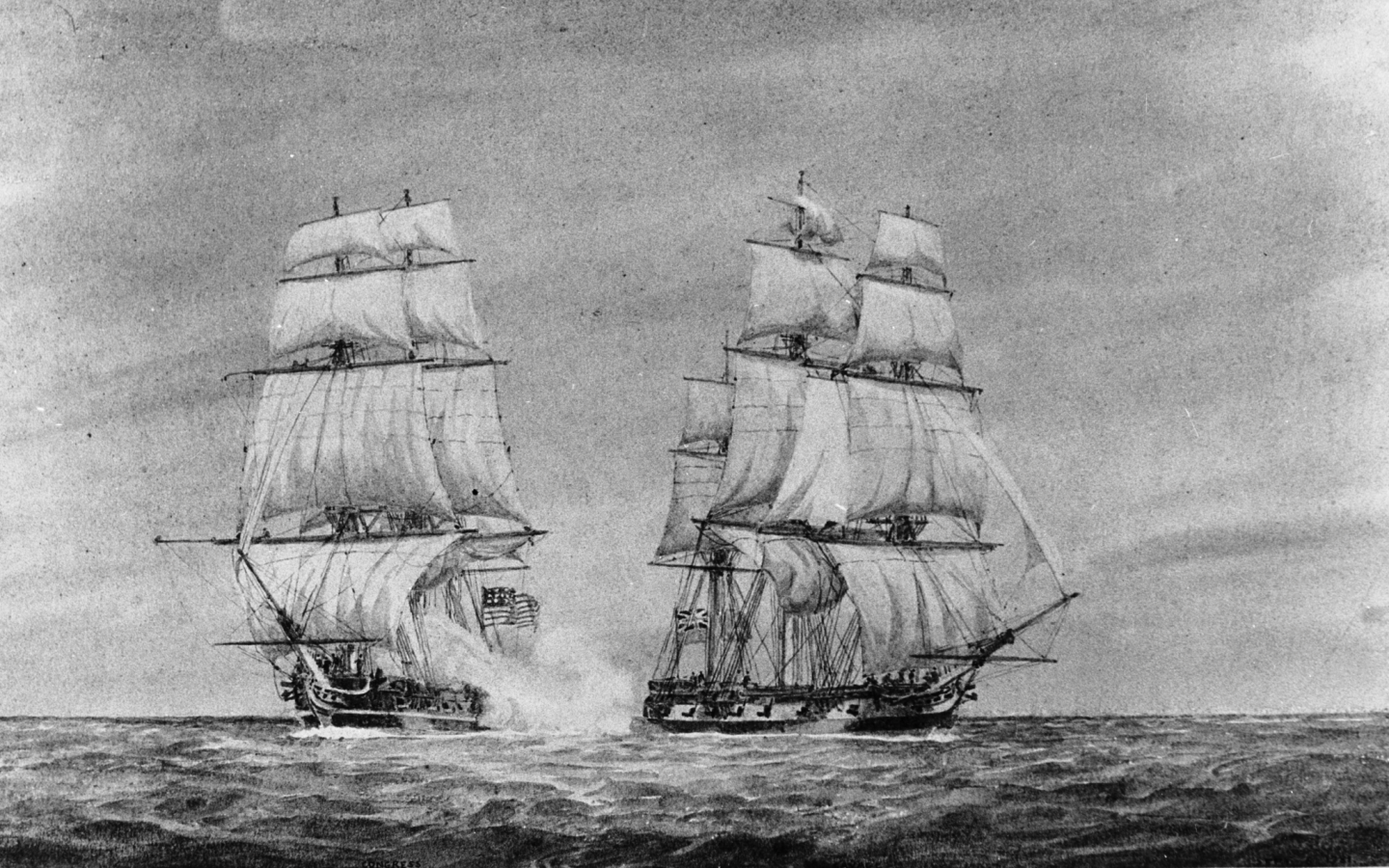

From Edward Stanton McClay's classic "The History of American Privateers", pp. 211-13: "One of the most creditable actions of this war in which an American privateer was engaged took place on September 6, 1781. It had been the habit of the smaller British cruisers stationed on the North American coast to send boat expeditions at night for the purpose of plundering estates along the shore. One of the most persistent English commanders in this questionable style of warfare was Captain Sterling, of the 16-gun sloop of war Savage. About the time mentioned Captain Sterling had been exploring Chesapeake Bay, and on one occasion sent a boat expedition to Mount Vernon and plundered Washington's estate. Soon after the Savage had put to sea from the Chesapeake, and was cruising off the coast of Georgia in search of other estates to plunder, she fell in with the American privateer Congress, of twenty-four guns and two hundred men, under the command of Captain George Geddes, of Philadelphia. Mr. Geddes, as we have noticed, had been a highly successful officer in the privateer service, having two years before commanded the 10-gun brig Holker, in which he made a most creditable record. Upon making out the Congress to be an American war craft of superior force, Captain Sterling made all sail to escape, upon which the Congress gave chase. It was early in the morning when the two vessels discovered each other, and by half past ten o'clock the American had gained so much that she was able to open with her bow chasers, and by eleven o'clock Captain Geddes was close on the Englishman's quarter, when he opened a rapid fire of small arms, to which the enemy answered with energy. Observing that he had the swifter ship of the two, Captain Geddes forged ahead until he got fairly abreast of his antagonist, when a fierce broad- side duel took place. Notwithstanding the American superiority in armament, this fire at close range so injured the privateer's rigging that it became unmanageable, and Captain Geddes was compelled to fall back to make repairs. As soon as he had com- pleted this work, the Congress again closed on the Savage and engaged in a heavy cannon fire. In the course of an hour the Englishman was reduced to a wreck, the vessels at times being so near each other that the men frequently were scorched by the flashes of the opposing cannon; and it is even asserted that shot were thrown with effect by hand. Seeing that the Englishman was reduced to a de- plorable condition, that his quarter-deck and fore-castle were swept clear of men, and that his mizzen-mast had gone by the board, while the mainmast threatened to follow it, Captain Geddes prepared to board and settle the sanguinary conflict on the enemy's decks. Just as the Americans were about to carry out this programme the boatswain of the Savage appeared on the forecastle, and waving his cap announced that they had surrendered, upon which Captain Geddes immediately took possession. The Englishmen's losses, according to their own statements, were eight killed and twenty-four wounded, while those of the Americans were thirty killed or wounded. Among the enemy's killed was Captain Sterling himself, who appears to have fought with the most determined bravery. Unfortunately Captain Geddes was not able to secure his prize, as both vessels were captured by a British frigate and carried into Charleston. The Congress was taken into the British service under the name of Duchess of Cumberland, Captain Samuel Marsh, and was wrecked off the coast of Newfoundland soon afterward while on her way to England with American prisoners. " The same fight - A more modern assessment from Wikipedia: "By 1781 the smaller British vessels blockading Chesapeake Bay were raiding the American coast by means of boat expeditions. One commander involved in the operations was Captain Charles Stirling of the sloop Savage, armed with sixteen 6-pounders. Stirling was noted for having plundered Mount Vernon, the Virginia estate of General George Washington, who was commander in chief of the Continental Army and later the first American president. Shortly after the raid of Mount Vernon, Captain Stirling sailed his ship south. In the early morning of September 6, Savage was escorting a convoy when she encountered the sloop-of-war Congress ten leagues from Charleston. Stirling placed Savage between the merchant vessels and the stranger. American privateers during the Revolutionary War Congress was under the command of Captain George Geddes of Philadelphia, armed with twenty 12-pounders and four 6-pounders, with a complement of 215 officers and men. Its Marines were under the command of Captain Allan McLane of the Continental Army. Congress was returning from Cap-François, Haiti, where McLane had carried dispatches from George Washington to Comte François Joseph Paul de Grasse, commander of a French fleet, appealing for his aid at Chesapeake Bay. When Stirling first saw Congress he sailed towards her, in the hope that she was a privateer of twenty 9-pounder guns that had been raiding in the area. However, when he got closer and saw that she was significantly stronger even than the privateer he thought she might be, Stirling attempted an escape. However, by 10:30 am the Americans came within range and opened fire with their bow chasers. By 11:00 Congress had closed the distance and her crew engaged with muskets and pistols, to which the British replied with "energy". At this point Captain Geddes observed that his ship was faster than that of the enemy so he maneuvered ahead of Savage until almost abreast, in preparation for a broadside. A duel then commenced at extreme close range, during which both ships were heavily damaged. Sailors on both sides were also burned by the flashes of their enemy's cannon. Congress's rigging was torn to shreds during the exchange, which compelled the Americans to stand off for quick repairs. After doing so, they resumed the chase. Congress was swiftly alongside the Savage again and another duel began. The Americans and British fought for about an hour, the combat ending with Savage in ruins. Her quarterdeck and forecastle had been completely cleared of resistance, her mizzenmast was blown away, and her mainmast was nearly gone as well. Geddes felt that this was an opportune time to board the enemy, but just as he was moving his ship in, a boatswain appeared on Savage's forecastle, waving his hat as a sign of surrender. British forces lost eight men killed and 34 wounded, including Captain Stirling; the Americans had 11 killed and around 30 wounded. In his letter reporting on the action, Captain Stirling noted that after he and his men became prisoners, the Americans had treated them "with great Humanity." In America, the capture was widely cheered as payback for the looting of George Washington's home by Captain Stirling and Savage's crew. However, the Americans who boarded Savage never made it back to port. The frigate HMS Solebay recaptured Savage on 12 September, with a prize crew of thirty Americans aboard. Maclay states that the same frigate captured Congress and recaptured Savage. (The London Gazette mentions the recapture of Savage, but not the capture of her captor Congress.) Notes Savage had a broadside of 48 pounds; Congress had a broadside of 132 pounds. (The privateer Stirling thought Congress was would have had a broadside of 90 pounds, or almost twice that of Savage.) Savage also had 90 fewer men on board than Congress. Maclay further states that Congress became HMS Duchess of Cumberland, and on 19 September wrecked during the passage to Newfoundland where a prison ship was waiting to take on the American prisoners. Twenty men died in the incident, though the survivors eventually made it to Placentia, where the Americans were put aboard the ship sloop HMS Fairy and taken to Old Mill Prison in England. This appears incorrect. The court martial record for her loss reports she sailed on 21 September from Placentia and was wrecked on 22 September. The nautical distance between Charleston and Halifax, Nova Scotia, is such that a vessel sailing at a steady 10 knots, a fast pace for a sailing vessel, would take four and a half days, and Placentia lies beyond Halifax, making it extremely improbable that a vessel captured on 12 September at Charleston would be sailing again from Placentia on 21 September, let alone 19 September. Furthermore Duchess of Cumberland was a cutter (or sloop; accounts vary) of 125 tons burthen and 16 guns. Lastly, early in his book, Maclay states that Congress/Duchess of Cumberland was built in Beverley, Massachusetts; Geddes's Congress was a Philadelphia privateer. She may have been a Congress, but if so, she may have been Congress, of eighteen 9-pounders guns, and 120 men, that HMS Oiseaux captured sometime between 16 June and 2 July 1781."

-

OK, I'm obviously getting errors with Flickr once again ...

-

Here is the Rattlesnake model in question, enlarged as much as is possible: [url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRidUp][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50440982983_554872ab82_b.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRidUp]0-2[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/165793220@N04/]Stephen Duffy[/url], on Flickr [url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRifh4][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50440987603_bfb3e7ffa6_k.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRifh4]0[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/165793220@N04/]Stephen Duffy[/url], on Flickr [url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRmPAv][img]https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50441685021_ea2c812f62_h.jpg[/img][/url][url=https://flic.kr/p/2jRmPAv]0-1[/url] by [url=https://www.flickr.com/photos/165793220@N04/]Stephen Duffy[/url], on Flickr Remember, this was 1920. There were no books available then by Howard Chapelle or Charles Davis. Nobody layman model builder knew of the National Archives resources, and the Admiralty draughts in London were still inaccessible and not yet unclassified. Yet these models were old in 1920 , so what did they use to build them, I wonder. The USS Delaware, 74 model actually looks pretty good.

-

Unfortunately, no. That was painted in 1828, probably long after the USS Rattlesnake was broken up, and way too large vessel carrying 28 guns. The RN had many Rattlesnakes, and that is surely another. But it does sound like a nice painting, however, by Antione Roux, no less. The catalog's author seemed duly impressed with his painting. Here is the Atholl-Class 28-gun ship of the same name, built in 1822, painted by Sir Oswald Walters Brierly. This was probably the ship pictured there.

-

I’d like to see more pics of that Brig Rattlesnake model of 1812! That is the only contemporary visual representation known of her. She shared similar lines with the Argus, but was built by Edward Hardt as a privateer and bought by the navy.

-

The problem with model shipways new Essex Kit is that They made it in an oddball scale of 1/76.2! That will definitely complicate the conversion math. I don’t understand why they didn’t just make the kit in 3/16th scale like their confederacy. Rafine’s Essex build was just beautiful, and should be carefully studied by anyone making the kit.

-

Dating 18th-century map from ship drawings

uss frolick replied to Stephen Gadd's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Welcome! You're not the famous drummer of the same name, are you?- 17 replies

-

- flag

- 18th century

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Well done, lads! Beating Wasa's record is quite an achievement!

-

Here's an interesting article I found tucked away in my old research papers from the 1990's. I can't find the title page, but I'm pretty sure comes from 'The American Neptune Quarterly' published by the Peabody Museum of Salem, but I don't have a date or a Volume for it. My bad. Anyway, it was written by a Fred Hopkins, and it concerns the post war career of the famous Chasseur, aka "the pride of Baltimore". She was sold south to the Spanish Royal Government of South America and used to battle revolutionary Colombian privateers during the great upheaval of the 1820s. Her name was changed to Cazador, and she fought several very bloody battles under the Spanish colors, including one where she captured an enemy privateer, and her captain proceeded to hang the captain and all the surviving crewmen! She changed hands several time, and while her fate becomes fuzzy about 1824, she may have ended her long career as a slaver. Anyway, the article is well written, and at 11 pages, kind of long. If anyone knows the exact issue of this article, please help me properly source this valuable information. My copy was folded, and somewhat distorted with age, but it is still legible, and here it is: 0 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-1 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-2 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-3 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-4 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-5 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-6 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-7 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-8 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-9 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr 0-10 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr

-

Here's another Adam and Noah Brown clipper that cruised in the war of 1812, the Zebra. She was captured and her lines were taken off. She might be enlarged and used to reconstruct the General Armstrong. 0-1 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr Of all the above privateers mentioned, the Dominica is well documented. Her lines are here: 0 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr While no named plan survives of the Chasseur, one plan of an unnamed Baltimore schooner does, and it is close to the large dimensions of the famed privateer. It was obtained by a French naval officer in Baltimore after the war. It is close enough to the dimensions of Chasseur that it might be her. It is here: 0-2 by Stephen Duffy, on Flickr All three drawings, of course, are by Howard Chapelle, and are taken from The Search For Speed Under Sail.

-

Well, it looks just like the buttons on the cloaks that I wear ... 🤓

-

I vote button belonging perhaps to a cloak. Likely the metal loop on the back long ago rusted away.

-

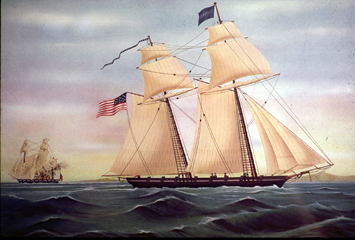

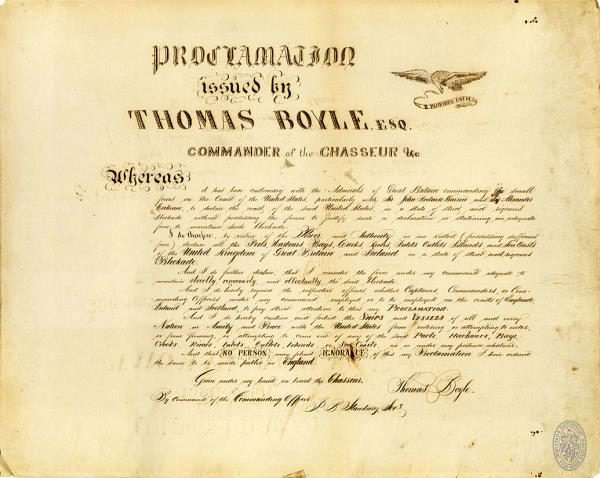

The cruise of the US Privateer Chasseur! From the same source ... "The History of American Privateers" by Edmond Stanton Maclay. "So great had been the success of Captain Boyle in the Comet that soon after his return from his last. cruise he was placed in command of the formidable privateer Chasseur, in which craft he achieved his greatest renown. This vessel probably was one of the best equipped and manned privateers that sailed in this war. She was familiarly called the Pride of Baltimore, mounting sixteen long 12-pounders and usually carrying a complement of one hundred officers, seamen, and marines. Speaking of her sailing qualities a Baltimore paper said : " She is, perhaps, the most beautiful vessel that ever floated on the ocean. Those who have not seen our schooners have but little idea of her appearance. As you look at her you may easily figure to yourself the idea that she is almost about to rise out of the water and fly into the air, seeming to sit so lightly. She has carried terror and alarm throughout the West Indies, as appears by numerous extracts from the West Indian papers received by her. She was frequently chased by British vessels sent out on purpose to catch her. She was once pretty hard run by the frigate Bareosa; but sometimes, out of sheer wantonness, she affected to chase the enemy's men-of-war of far superior force." In his first cruise in this formidable vessel Captain Boyle captured eighteen merchantmen, nearly all of them of great value. Some of these were the sloop Christiana, of Kilkade, Scotland; the brig Reindeer, of Aberdeen; schooner Favorite, laden with wine; the brig Marquis of Cornwallis; the brigs Alert and Harmony, from Newfoundland; the ship Carlbury, of London, from Jamaica, laden with cotton, cocoa, hides, indigo, etc. (the goods taken from this vessel were valued at fifty thousand dollars); the brigs Eclipse, Commerce, and Antelope, the schooner Fox; the ships James and Theodore; and the brigs Atlantic and Amicus. The Chasseur brought into port forty-three prisoners, having released on parole one hundred and fifty. Captain Boyle's favorite cruising ground was in the British Channel and around the coasts of Great Britain. He seemed to act on the principle which led Farragut to immortal fame half a century later, namely: "The nearer you get to your enemy the harder you can strike." By thus " bearding the lion in his den " the Chasseur had some exceedingly nar- row escapes, but always eluded the enemy by her fine sailing qualities and by the superb audacity of her commander. At one time the privateer was so near a British frigate as to exchange an effective broadside with her, and not long afterward she was completely surrounded by two frigates and two brigs of war. In making a dash to escape, the Chas- seur received a shot from one of the frigates, which wounded three men, but in spite of the danger she finally eluded the enemy. The "superb audacity" of Captain Boyle has already been mentioned, not that it was peculiar to him, for it was shared more or less by all our priva- teersmen, but because it was exhibited by him on this cruise in a unique and emphatic manner. It had been the custom of British admirals on the American stations to issue "paper blockades," declaring the entire coast of the United States to be blockaded. Several of these "paper blockades" had been recently issued by Admiral Sir John Borlaise Warren and by Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane. On the strength of these foolish proclamations British cruisers were withdrawn, at will, from the ports blockaded and transferred to other points along the coast without at least in the estimation of the English admirals in the least invalidating the blockade. To show the absurdity of these procla- mations, Captain Boyle, while cruising in the English Channel, sent by a cartel to London the following proclamation, which he " requested " to be posted in Lloyd's Coffee House: " By Thomas Boyle, Esquire, Commander of the Private Armed Brig Chasseur, etc. "PROCLAMATION: " Whereas, It has become customary with the admirals of Great Britain, commanding small forces on the coast of the United States, particularly with Sir John Borlaise Warren and Sir Alexander Cochrane, to declare all the coast of the said United States in a state of strict and rigorous blockade without possessing the power to justify such a declaration or stationing an adequate force to maintain said blockade; " I do therefore, by virtue of the power and authority in me vested (possessing sufficient force), declare all the ports, harbors, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, and seacoast of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in a state of strict and rigorous blockade. "And I do further declare that I consider the force under my command adequate to maintain strictly, rigorously, and effectually the said block- ade. " And I do hereby require the respective officers, whether captains, commanders, or commanding officers, under my command, employed or to be em ployed, on the coasts of England, Ireland, and Scot- land, to pay strict attention to the execution of this my proclamation. " And I do hereby caution and forbid the ships and vessels of all and every nation in amity and peace with the United States from entering or attempting to enter, or from coming or attempting to come out of, any of the said ports, harbors, bays, creeks, rivers, inlets, outlets, islands, or seacoast under any pretense whatsoever. And that no person may plead ignorance of this, my proclamation, I have ordered the same to be made public in England. Given under my hand on board the Chasseur. "THOMAS BOYLE. " By command of the commanding officer. " J. J. STANBTJRY, Secretary." Quite in keeping with Captain Boyle's audacity is the memorial presented by the merchants of St. Vincent to Admiral Durham, in which it is stated that the Chasseur had blockaded them for five days, doing much damage, and requesting that the admiral would sent them at least " a heavy sloop of war." The frigate Barrosa was sent. The memorial gave a pitiful account of how the Chasseur was frequently chased " in vain," at one time by three cruisers to- gether. It then quotes a letter from Martinique stating that this vessel was permitted to supply herself with a new boom, that the captain was treated very politely, that on Sunday he dined with M. Du Buc, the French intendant at the island, " a fine companion, truly, for the governor of such a colony as Martinique." The memorial further complained that the Chasseur ventured within gunshot of the forts of St. Lucia to cut out the transport Lord Eldon, and probably would have done it but for the sloop of war Wolverine, which hove in sight; that the Chasseur burned two sloops "in the face of the island" possibly a West Indian form of the expression " under their noses " ; that she hoisted the Yankee stripes over the British ensign " and played many curious pranks " ; and other complaints in the same tenor. The Chasseur arrived in New York from her European cruise in October, 1814 It was in his last cruise in this war that Captain Boyle gained his greatest reputation for daring and success on the high seas. On February 26, 1815, when the Chasseur was about thirty-six miles to windward of Havana and some twelve miles from land, a schooner was discovered, about eleven o'clock in the morning, to the northeast, apparently running before the wind. This was the English war schooner St. Lawrence, Lieutenant Henry Cranmer Gordon, which, as we remember, was the American privateer Atlas, Captain David Maffitt, captured by boats from Rear-Admiral Cockburn's squadron in Ocracoke Inlet, July 12, 1813, the Atlas having been taken into the British service under the new name. The St. Lawrence proved to be a valuable addition to the enemy's fleet, taking an active part in their many expeditions along the coast and acting as a dispatch boat, in which service her fine sailing qualities gave her every advantage. Here we have an admirable opportunity to compare the relative merits of American and British man-of-warsmen; for the St. Lawrence, being built and equipped by Americans, deprives our friends, the English, of their oft-repeated cry that our vessels were better built, etc. The Chasseur carried fourteen guns and one hundred and two men, as opposed to the St. Lawrence's thirteen guns and seventy-six men. Both vessels were schooners. When sighted by Captain Boyle, the St. Lawrence was bearing important dispatches and troops from Rear-Admiral Cockburn relative to the New Orleans expedition. Captain Boyle promptly made sail in chase, and soon discovered the stranger to be a war craft having a convoy in company, the latter being just dis- cernible from the masthead. By noon the Chasseur had perceptibly gained on the chase, which to the Americans appeared to be a long, narrow pilot-boat schooner with yellow sides. When she made out the Chasseur she hauled up more' to the north, evidently anxious to escape. At half past twelve Captain Boyle fired a gun and showed his colors, hoping to ascertain to what nation the chase belonged, but the latter paid no attention to the summons, and in her efforts to carry a greater press of sail her fore-topmast was carried away. At the time this happened she was about three miles ahead. Her people promptly cleared the wreck away and trimmed her sails sharp by the wind. Owing to this accident the Chasseur drew up on the chase very fast, and at one o'clock the latter fired a stern gun and hoisted English colors. As the stranger showed only three ports on the side nearest to the Chasseur, Captain Boyle got the impression that she was a " running vessel " bound for Havana which in all probability was poorly armed and manned. Acting on this impression he increased his efforts to get alongside, confident of making short work of her. This mistake of the Americans was encouraged by the fact that very few men were seen on the deck of the stranger. As neither Captain Boyle nor his officers anticipated serious fighting, the regular preparations for battle were not made. At 1.26 P. M. the Chasseur was within pistol shot of the enemy, when the latter suddenly triced up ten port covers, showing that number of guns and her decks swarming with men wearing the uniform of a regular British man-of-war. Evidently they had been carefully concealed during the chase. It took the enemy scarcely five seconds to give three cheers, run out their guns, and pour in a whole broadside of round shot, grape, and musket balls into the Chasseur. For once, at least, the crafty Yankee skipper had been caught napping. He was fairly and squarely under the guns of an English man-of-war, so that either prompt surrender or fight were the only alternatives. It did not take Captain Boyle an instant to decide on the latter course, and, although taken somewhat by surprise, he made the best of the situation and returned the enemy's fire with both cannon and musketry. Believing that his best chance for victory was at close quarters, Captain Boyle endeavored to board "in the smoke of his broadside; but the Chasseur, having the greater speed at that moment, shot ahead under the stranger's lee. The latter put up his helm for the purpose of wearing across the privateer's stern, with a view of pouring in a raking fire. Perceiving the enemy's object, Captain Boyle frustrated the maneuver by putting his helm up also. The Englishman now forged ahead and came within ten yards of the privateer, the fire of both vessels at that time being exceedingly destructive. At 1.40 P. M. Cap- tain Boyle, seizing a favorable moment, put his helm to starboard and called on his men to follow him aboard the enemy. Just as the two vessels came to- gether W. N. Christie, prize master, jumped aboard the stranger's deck, followed by a number of other Americans, but before they could strike a blow the English surrendered. The St. Lawrence, according to British accounts, mounted twelve short 12-pounders and one long 9-pounder and had a complement of seventy-five men, besides a number of officers, soldiers, and civilians as passengers, who were bound for the British squadron off New Orleans. According to the report of her commander she had six men killed and seventeen wounded, several of them mortally. According to American accounts the English had fifteen killed and twenty-five wounded. The St. Lawrence was found to be seriously injured in the hull, while scarcely a rope was left intact, such had been the accuracy and rapidity of the Chasseur's fire. The privateer also suffered considerably in her sails and rigging, while five of her crew were killed and eight wounded, among the latter being Captain Boyle himself. In view of the fact that the action lasted only fifteen minutes these casualties reveal, better than words, the desperate nature of the encounter. The Chasseur mounted six 12-pounders and eight short 9-pounders ten of her original sixteen 12-pounders having been thrown overboard when the privateer was chased by the British frigate Barrosa. They were replaced by the 9-pounders which had been taken from a prize. " From the number of hammocks, bedding, etc., found on board the enemy," said Captain Boyle, in his official report to one of the owners of the Chas- seur, George P. Stephenson, of Baltimore, " it led us to believe that many more were killed than were reported. The St. Lawrence fired double the weight of shot that we did. From her 12-pounders at close quarters she fired a stand of grape and two bags containing two hundred and twenty musket balls each, when from the Chasseur's 9-pounders were fired 6- and 4-pound shot, we having no other except some few grape." In closing his report, Captain Boyle speaks in the highest terms of the gallantry of his first officer, John Dieter, and of the second and third officers, Moran and Hammond N. Stansbury. That night the masts of the St. Lawrence went by the board, and having no object in bringing home so many prisoners Captain Boyle made a cartel of his prize and sent the prisoners by her into Havana. After this gallant affair the Chasseur returned to the United States with her hold filled with valuable goods. She arrived in Baltimore, April 15, 1815, where it was learned that a treaty of peace had been signed. So well pleased were the British officers at the treatment they received from the Americans that Lieutenant Gordon issued the following memorial or certificate dated: "At Sea, February 27, 1815, on board the United States Privateer Chasseur: In the event of Captain Boyle's becoming a prisoner of war to any British cruiser I consider it a tribute justly due to his humane and generous treatment of myself, the surviving officers and crew of His Majesty's late schooner St. Lawrence, to state that his obliging attention and watchful solicitude to preserve our effects and render us comfortable during the short time we were in his possession were such as justly entitle him to the indulgence and respect of every British subject. I also certify that his endeavors to render us comfortable and to secure our property were carefully seconded by all his officers, who did their utmost to that effect." The Chasseur fights HMS St. Lawrence! The Chasseur privateer: Captain Thomas Boyle: That infamous proclamation!

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.