-

Posts

2,178 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by uss frolick

-

Lost voices from HMS Guerriere: Court Martial testimony.

uss frolick replied to uss frolick's topic in Nautical/Naval History

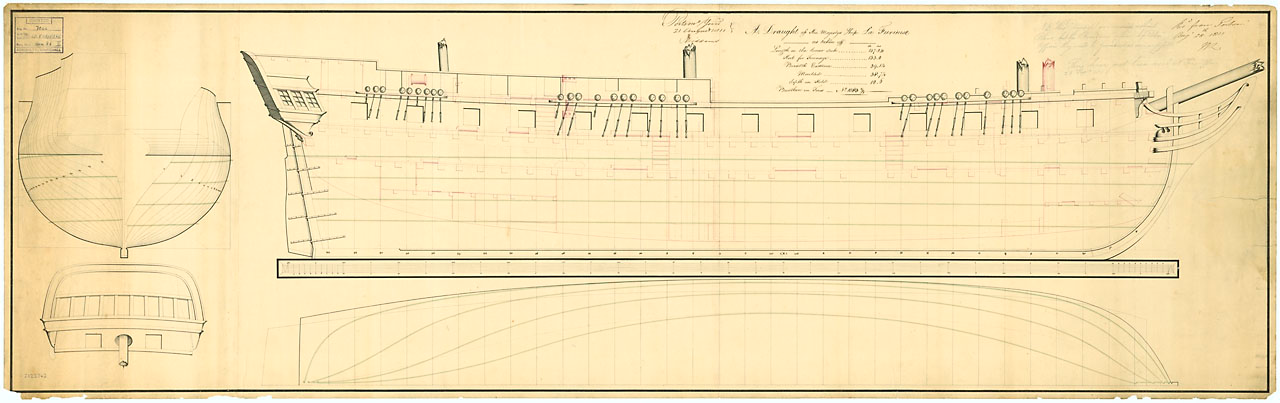

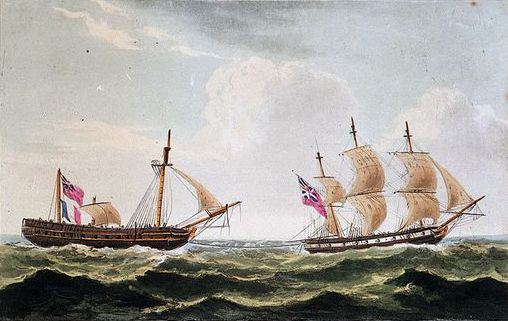

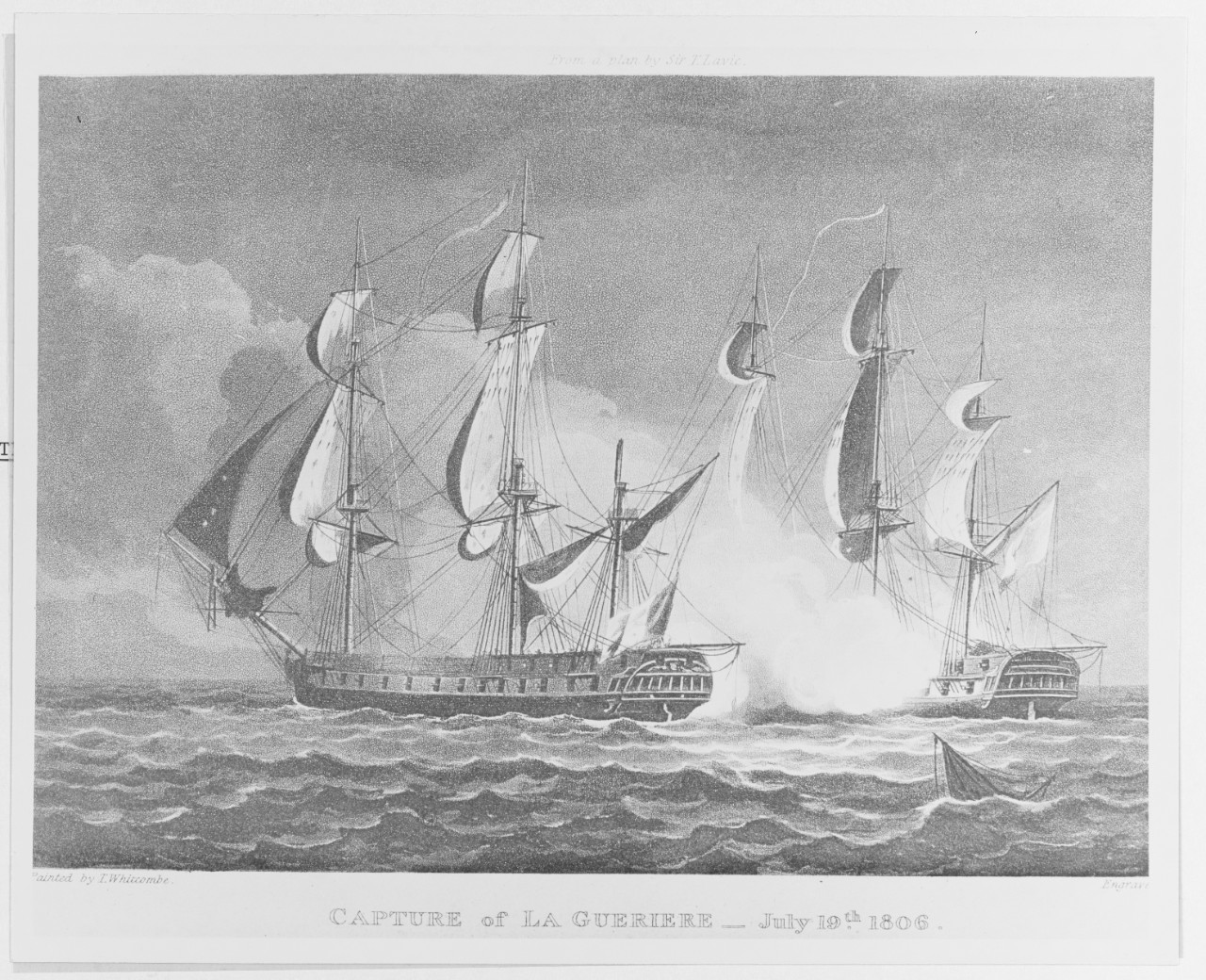

While no plans survive of HMS Guerriere, either in French or English archives we do have an idea what she looked likeLa Guerierre was built at Cherbourg to a design of an engineer named La Fosse. We do know that she was begun as a Romaine Class frigate, a smaller 24-pounder type, but lengthened into a standard 18-pounder ship on the stocks. Nine were built and completed to the original design. We know what the original class looked like, because the original French builders draught survives, and two of the class were taken, L'Immortalite and La Desiree', and their draughts survive in the NMM. They all have a very round midship section, required because the initial draught called for a 10" mortar amidships, and a full midship reduces the recoil downward into the water! At length, all were rearmed with twenty-four 24-pounders on the main deck. The last ships of the class were converted by lengthening them by about 15 feet. Plans for two of these survive, HMS Pique, 36, which has an ironic Constitution connection in 1814 under Captain Stewart, and HMS La Furieuse, 38. A coulee others were altered on the stocks later as well. La Furieuse was fitted out "en flute" when captured in 1806, and was used by the French as an armed troop transport mounting twenty heavy guns. She was taken by the 20-gun sloop of war HMS Bonne Citoyenne in an epic day-long battle. Here are her plans. This reflects her as fitted as a transport, without forecastle barricades. Note the beak-head bulkhead which Guerriere did not have. Note also the nine windows across her stern, a large number shared by Pique, Desire, L'Immortalite, and a Roux painting of sister L'Incorruptable. Note the round midship: So if anyone wanted to build La Guerriere, one option would be to start with La Furieuse, add forecastle bulwarks and an armed bridle-port, and put thirty long 18-pounders on the main deck. La Guerriere taken by HMS Blanche in 1806: -

I have the full set of plans of Imperiuse. They include that drawing in 1/2 inch scale, and another in the same scale of her stern decorations. She is a very lovely ship. They are marked as taken off following her repair in 1809.

-

Update: This series is turning out to be really good. There was nearly ten hours on The Surgeon's Mate alone, divided up into nine pats. Great discussions, and many episodes feature special guests, who are experts of specific topics, such as medicine, period formal parties, music, sailing, history, etc.

-

Thanks Moltinmark, but I'm getting zero results for Hamilton, Scourge or Lord Nelson.

- 16 replies

-

- figurehead

- Thesis

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

USS Delaware 1817 by threebs

uss frolick replied to threebs's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1801 - 1850

Don’t forget the USS New York, 74. Although unlaunched, she had been completed and was ready to fit out, if required. ... all that beautiful southern live oak, up in 🔥 flames 🔥! -

These are not summaries or dramatic readings of the books, but discussions about the characters, plot twists and impacts the series has had on the literary world. They are really well done, and if you need some appropriate background noise, 'whilst you're widdlin', these might be of interest to you. This series started, with Ian and Mike, about six months ago, and there are currently 35, roughly hour-long episodes, yet they are only up to the book, 'The Ionian Mission'. I urge you all to subscribe to their Youtube Channel. There are only 66 subscribers to date, so maybe we swabbies we can do something about that there low number! Here is episode One, Master and Commander, part 1. Enjoy:

-

Thanks Wayne. Your excerpt of Kopp, Nadine, 2012, “The Influence of the War of 1812 on Great Lakes Shipbuilding.” MA Thesis, East Carolina Univeristy ,gave some very helpful measured dimensions of both schooners for anyone attempting to reconstruct them.

- 16 replies

-

- figurehead

- Thesis

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

I flatter easily ... 😛 I would recommend both Scourge/Hamilton books, as well as "A Life Before the Mast", by Ned Myers, a Scourge sailor's narrative of the sinking. The Cain book is getting hard to find. Crisman definitely!

- 16 replies

-

- figurehead

- Thesis

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hey Wayne, Can you find any papers or any technical archeological articles on the 1813 Lake Ontario wrecks of the US Schooners Hamilton and Scourge? I mean, other than the books "Ghost Ships" and "Coffins of the Brave", and that National Geographic article from the 1980's?

- 16 replies

-

- figurehead

- Thesis

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

A couple of recent additions to US Naval History

uss frolick replied to trippwj's topic in Nautical/Naval History

The latter link is turning out to be a great read, especially the reviews of Samuel Elliot Morrison's classic 'Sailors Biography of John Paul Jones', Meville's 'White Jacket', and Roosevelt's 'Naval History of 1812'! Thanks! -

A couple of recent additions to US Naval History

uss frolick replied to trippwj's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Me neither ...😥 -

The British Schooner of War Dominica mounted a 4-pounder brass swivel/cohorn on her capstan when she fought the privateer Decatur in 1813. The Frigate Constitution mounted a seven-barreled swivel Chambers Gun on her capstan when she fought the Cyane and Levant in 1815, for defense against enemy boarders, in addition to additional Chambers guns in her tops. The Privateer Fair American, of the Revolutionary War fame, mounted a large swivel on her capstan, according to the memoirs of one of her crewmen, (Jacob Nagel - who would later sail to Australia in the 'First Fleet) that was used to good effect in defeating an enemy's nighttime boat attack.

-

There was an account I read about a formal evening party thrown on the deck of the new frigate USS Potomac in 1828 while fitting out in Washington. They covered the spar deck with canvass and created a candelabra on the capstan by ringing it with muskets with bayonets fixed. There was a candle placed in each muzzle and this illuminated the spar deck ...

-

Great to see you posting again, Wes. I really like the clean fairing of the cant-frames and hawser timbers. Nice. Interesting that you are working on the stem post. The Essex's stem was, according to Josiah Fox, the only part of the ship, above the waterline, that didn't have to be replaced! I have anecdotal evidence too, that she retained her Indian figurehead ...

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.