-

Posts

25 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Recent Profile Visitors

The recent visitors block is disabled and is not being shown to other users.

-

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

-

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

Starting in Rhino 8

CCClarke replied to GioMun's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

I must have been lucky. The design engineers using SolidWorks where we worked were very good at what they did, but were not artistic. Their renders for presentation packages were basically different colors to identify different parts within an assembly. These types of graphics are common, and we wanted to stand out from our competitors. Once I got my CG footing, I converted our inhouse models, (or used technical drawings to model when conversion was too time-consuming to meet a deadline) into photo-realistic renders. The reaction of the customers to our enhanced presentations was immediate and positive, which gave me a niche that turned a collateral duty into a full-time gig. Everybody won. After that, I started adding graphics to training and documentation packages. This was especially helpful when the hardware was very small or might require a "God's eye" view from a distance. Occasionally, a customer would call with a specific request for one of their presentations, and that became another capability we capitalized on. On more than one occasion, other companies would ask for some of my models, or request me to travel to their facility to collaborate on a shared contract with their graphics people. I never ran out of work. Even after transferring to the East coast to another part of the company, my old management asked to "borrow" me. Those requests were flatly refused, since my other skills in high-reliability, precision assembly and QA were more valuable and we were always short-handed. I still did graphics work for the Director when an important presentation was looming. It was very enjoyable having acquired a lot of useful training and certifications during my career, many of which I apply to ship modeling while retired. -

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

Gregory reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

sheepsail reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

sheepsail reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

Starting in Rhino 8

CCClarke replied to GioMun's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

I have a feeling you're going to amaze me very soon Giorgio! One common theme I read in posts throughout the modeling forums I visit are from people wishing they could model and others who tried and quit in frustration. I was fortunate to attend a top-notch school that focused on modeling and animation with some of the best teachers from the television and film industry to share their experience. I had been modeling for almost a year and my workflow, (really, my best-guest flow) was full of bad habits I had to unlearn immediately. Every student there paid big bucks and all were motivated to get jobs in the industry. I was by far, the oldest student in the school and a subject of much curiosity. The majority of the students were teenagers or in their early twenties. (I was 48, and my training was paid for by my company to help us make better presentations for high-dollar contract bids.) We started with about 31 students the first day. Two weeks later, there were 15. A month later a few more had dropped. I asked the Director of the school if this was normal and he said unfortunately, it was. Every one of those students under-estimated the amount of work was involved to become proficient, both during and after school. The homework load was pretty heavy and modeling things that take me minutes now, took hours then. Living in a hotel without any distractions, I studied at least twelve hours a day. On weekends, even more. Our teacher emphasized the mindset I mentioned before. Even though I was a dedicated student from previous experiences, I still hit a few obstacles and documented them to ask questions in class. I still have that notebook and read it once a year. This is another reason I emphasize writing everything down when starting out. (I still do it now!) A few simple things to model, (especially with digital calipers or a tape measure for large objects) are: A Pair of Dice. -A simple cube with cylinders arranged to form the "dots" subtracted from each side. (The number of dots on opposing sides should equal seven.) A Desk: Entirely composed of square objects stretched and aligned to fit. Your Kitchen: The cabinets are usually nothing more than thin squares and rectangles. The walls can be made from larger rectangles positioned accordingly or a single, six-sided box (reverse the polygons and remove the top and two outer polygons to create a diorama effect with no wall thickness) as another method. A Flying Saucer! Create the exterior profile by making a single spline or group of points turned into a single polygon for the profile, then Spin, Revolve, or Lathe (a very common tool with different names in each app) with the flat side that makes up the middle on the Y axis @ the zero position. The more sides you Spin, Revolve, or Lathe, the smoother your UFO will be. The more points in the profile, the higher the polygon count. A Wine Glass or Goblet: Same workflow as the UFO. Being able to use your tools to create these shapes is applicable when building a ship model. If something I've written doesn't make sense or you need example screen shots to help illustrate my points, feel free to PM me and I'll describe in more detail how I do it. Just tell me what program you're using, (Rhino?) and I'll try to get the tool names right for your application. Chi non risica non rosica! CC -

CDR_Ret reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

CDR_Ret reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

GioMun reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

GioMun reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

Starting in Rhino 8

CCClarke replied to GioMun's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Keep at it Giorgio! There's lot of good advice in this thread. As a beginning modeler, (even when you understand all of the basic tools) one of the hardest things to learn is where to begin. For me, that was the hardest part, and it was very intimidating. Like karate, you can learn to punch and kick, but combining variations of those moves is what gives you the confidence and ability to prevail in a real fight. Modeling is very similar. Too many tutorials focus on tools without showing how to combine them to create and modify more complex shapes. Combining tools to make what you want is called workflow, and it comes to you over time and many, many dead ends. The other quality needed to become proficient is the correct mindset. Modeling isn't easy or everybody would be doing it. The AI generative 3D modeling programs being shown online are a poor substitute for real-world modeling skills. Once you learn to model, you have a skill that can never be taken away from you. Nobody learns anything without making mistakes. Perseverance is a big part of learning the craft. I've had times where I couldn't make a particular tool perform the way I thought it was supposed to. Every tool has rules that must be learned and some of those rules aren't well-documented - if at all. I spent three eight-hour days once, using the same tool over and over to learn what made it unable to continue, while the program gave me error messages that made no sense. Every time I got it to work, I wrote down what made it fail. I was surprised how many conditions could cause this and submitted a post online explaining how I made it work. The many replies of thanks were astounding! Many modelers had given up on that tool, limiting their ability to progress. I had to break through that wall by chipping away at it, little by little and documenting everything. The things I learned went into my workflow, and contributed to my ability to inspect the mesh for irregularities when using other tools, that I still use today. I don't even think about it anymore, I just use those skills automatically the second something doesn't work and quickly solve the problem. The learning never ends, which is another facet of modeling I enjoy - problem-solving, which really sums up what 3D modeling is, and I've been doing it almost daily for twenty years. A lot of what you're starting out with in your examples is basic spline modeling to create hull curvatures. A spline is nothing more than a curved line defined by how many points are in it. Those points can be patched, (automatically or manually) to create polygons which becomes a "skin" as more polygons are added to the mesh. Every model is composed of points, edges, and polygons. Each modeling program manipulates them in similar ways using different tool names. Personally, I would recommend modeling simple things around your house. A salt-shaker can be made with a couple of basic modeling tools. Those same tools can make a cannon or pedestal. Be realistic about your expectations to keep your progress moving forward - even if in tiny increments. A ship's hull is more complex and can lead to great frustration or worse, giving up. Start simple, (like making a table or the afore-mentioned salt shaker) to get the basics of creating and moving and aligning shapes before progressing to more complex shapes. You will be surprised how quickly you begin to create a workflow that gives fast results. One of the first (physical tools) I invested in to help my modeling of simple objects was a set of inexpensive digital calipers. It helped me to create the everyday things around me more accurately and proportionately. Success builds enthusiasm, and enthusiasm is contagious! Time how long it takes to make a simple object if you're following a tutorial. Repeat the tutorial the next day. The day after that, build the same object without the tutorial, until you have the workflow memorized. Notice how fast you build it compared to the first time. My modeling speed doubled every three months once I had the basics figured out. Some of the tutorials took me hours to complete at first. Using the method I described allowed me to do in minutes what had taken hours in a very short period of time. Timed modeling is an excellent way to measure your progress and keep you motivated. When you have the basic tools memorized, (and more importantly, how to use them in combinations) move into spline modeling, which is a different style of modeling. Like math, there are many ways to get the correct answer when modeling. The best way is the one that works for you in the least amount of time achieving the shape you need. Maintaining the correct mindset is the one tool not included with your software that ultimately determines your success. Everybody who invests the time to create beautiful models can relate to this philosophy. All of them started knowing nothing. I look forward to seeing your progress, even if it isn't ship-related. CC -

CCClarke reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

CCClarke reacted to a post in a topic:

Starting in Rhino 8

-

FreekS reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

FreekS reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

-

thibaultron reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

thibaultron reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

-

CDR_Ret reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

CDR_Ret reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

-

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

GrandpaPhil reacted to a post in a topic:

CG Renders of the USS Seawolf (SSN-575)

-

Lots of good replies posted in response to your questions. 1. I bought a resin printer five years ago, (Phrozen Mighty 4K) along with a cure station, (-also from Phrozen, using a turntable with UV lights surrounding it, with a UV-proof plastic cover) for just under $500 during an Amazon Prime Sale. I keep a log for each print to record how long they took, and any lessons along the way. The elapsed time is important since decent LED arrays are rated to 2000 hours. I'm on print #297 with zero issues with the printer. Any problem prints were my fault and easy to diagnose. Depending on the size requirements for your needs, you may be able to get by with a small printer. Check the print volume before pulling the trigger. I'm at the point now where I need a larger one and will upgrade soon. I'll keep the smaller one for small parts. I printed a set of anchors yesterday that took six hours to design, and an hour to print. Each is smaller than my small fingernail. The quality is always amazing! As for cleaning, I use one plastic tub to spray the build plate/printed parts with 91% IPA using an old Windex bottle, let them soak for three minutes, dry them with my airbrush set to 60 psi, then repeat the process once more. This saves a small fortune in submerging everything in IPA -as many other do. I dump the leftover IPA from the cleaning tub (usually about 1/8 of a cup) into the plastic-lined trash can next to my bench with some paper towels to absorb it. The trash can goes outside where the IPA can evaporate. I went from buying gallons of IPA, (and dealing with the aftermath) per year to a few quarts using this method. A foam brush also helps when cleaning large parts. If I find any residue, I use an IPA-soaked cotton swab to clean it, and blast it with air to evaporate any remaining IPA. After that, I place the build plate in an identical plastic container with enough hot water to submerge the build plate to cover the surface the parts are adhered to. The hot water loosens the parts and expands a miniscule amount allowing the parts to be removed with a slim metal spatula. I let the removed parts soak for a couple of minutes making part support removal easy. For some smaller parts, (like the aforementioned anchors) I leave the supports on, since fishing them out of the water is a PITA. Once all the parts are out, I blow-dry them once more. Some people like the vortex cleaning stations, but again, you're dealing with a larger mess when trying to cure/re-filter IPA in bulk. Time is one thing I never seem to get enough of. 2. Resin is a skin irritant and any resin dust from sanding is not something you ever want to breathe. Nitrile gloves are needed when handling uncured parts. A respirator and is recommended when sanding large parts. Eye protection should be worn anytime liquid resin is present. Some resins put out stronger fumes than others. Unless you have a dedicated indoor space with a good way to ventilate it (via air extractor venting outside) the garage is the place to print. Spill resin on indoor carpet and you're in real trouble. Carpet should never be near a workbench anyway. 3. Temps. Resin changes viscosity (thinner when hot, thicker when cold) which can greatly affect how the parts print. Ideal temp is between 70-75 for most resins, but check the mfr's recommendations before ordering any. In New England, I was limited to printing during warmer weather. You can use a heated enclosure made for 3D printing but if the duty cycle is too great, print quality will suffer. I compromised when I moved to Arizona three years ago on a two-car garage (I wanted the extra work space afforded by a three-car garage) but changed my mind because this one came with a dedicated heat pump - I can print year-round now in comfort with consistent results. I had to replace the large, cylindrical hot water heater to a small, wall-mounted on-demand unit that is more economical, freeing up additional space. If you're on social media, there are plenty of manufacturer sites where members can bitch and moan, with lots of failed print pictures. Besides keeping a personal print log, this is another great way to learn from other's mistakes, or learn how to troubleshoot (very rare) hardware failures. Like I mentioned, my printer has been trouble-free. The majority of my prints take 15-18 hours, and it works as well as when I first started. A handy tool in my arsenal is a Phrozen Cure Beam. This works well to cure small parts in < 10 seconds or the inside of the hulls I build. A set of silicon mats, (resin doesn't stick to them are under my printer, (in case of a printer spill) and my work area where I clean parts. Any printer that comes with a hook to hang your build plate to drip dry is a bonus. It recovers a little bit of the excess resin and decreases the amount you need to clean off the top of the plate by hand. I used an FDM printer to make a hanger for mine that I found for free on Thingverse. When I switched from FDM to resin printing, (far less sanding and resolution you'll never get from a .2" nozzle extruding hot plastic) I didn't like the cleaning phase, but once you get used to it, (and see the quality of your printed parts) it isn't a big deal and takes 15 to 30 minutes - 45 min or so if you print fifty parts at a time like I sometimes do. If you have any more questions, fire away. Someone here will be able to answer them. CC

-

3D printing material question

CCClarke replied to CPDDET's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

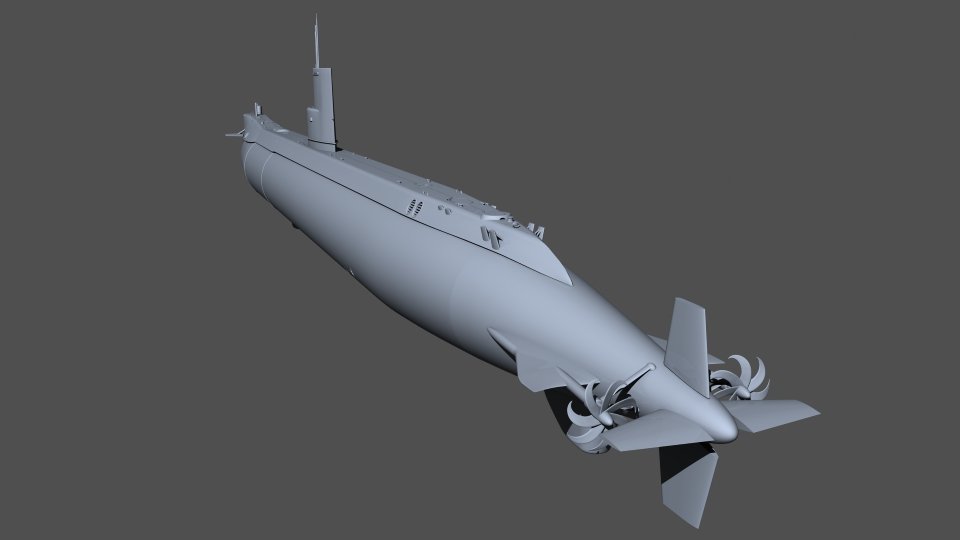

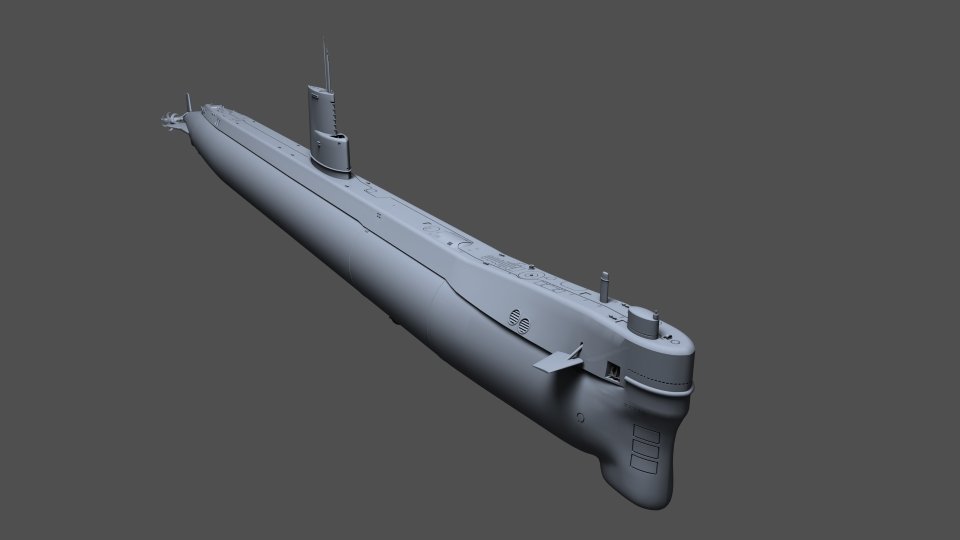

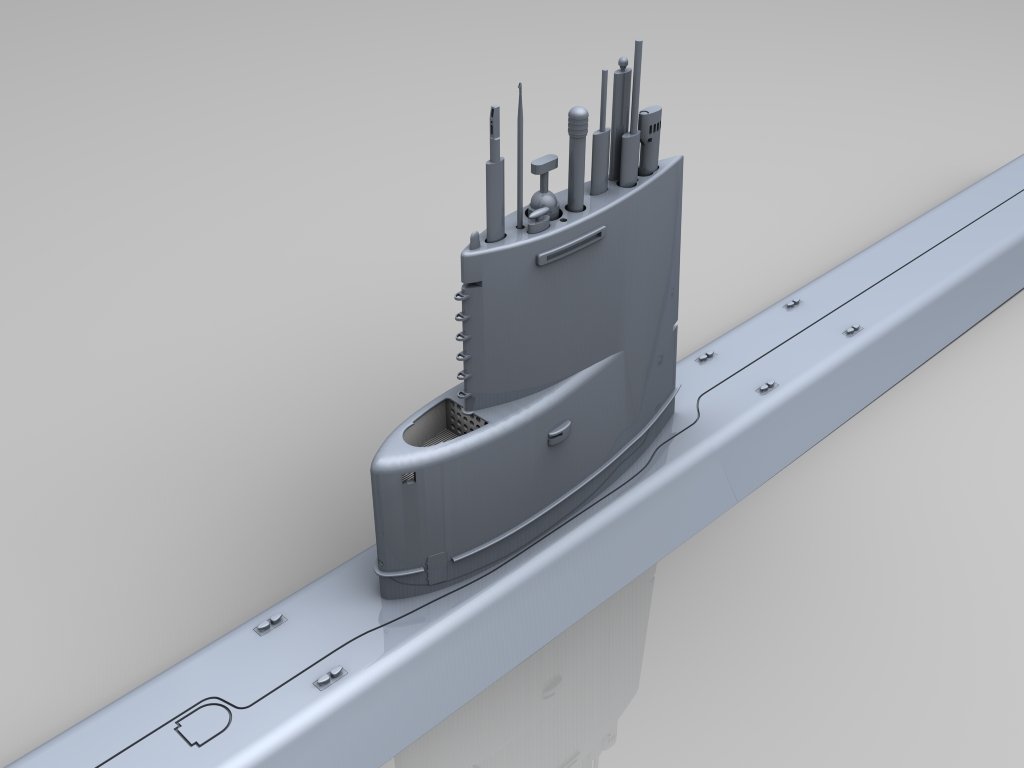

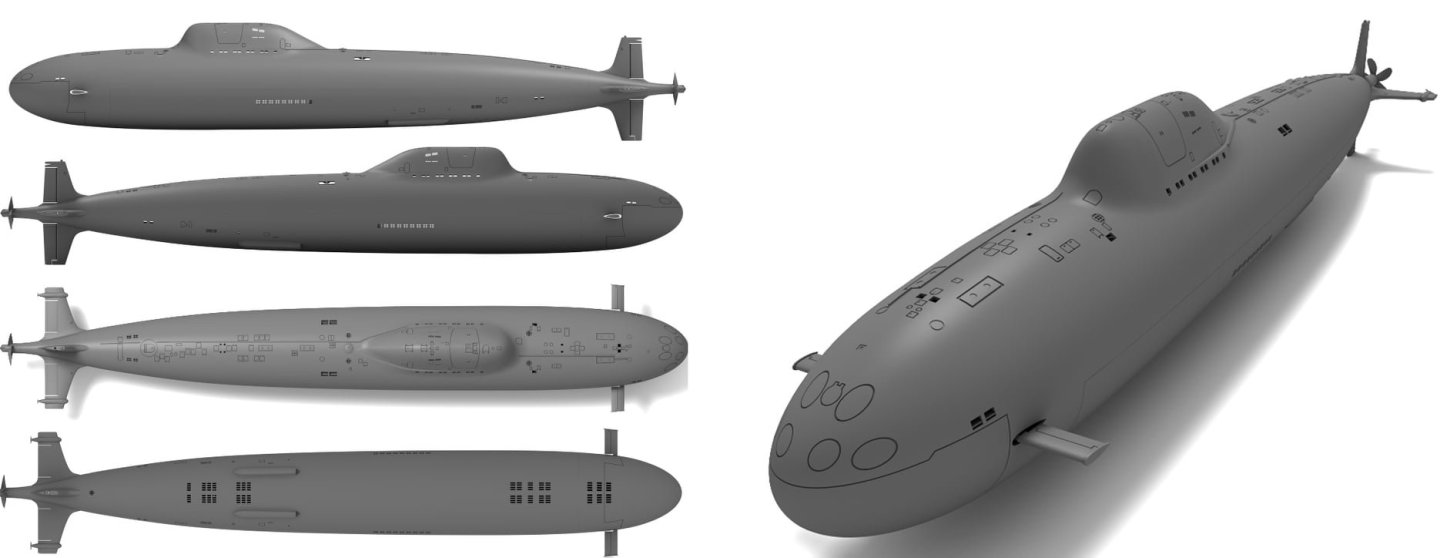

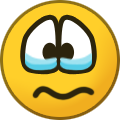

FDM printing is ideal for those who enjoy sanding and aren't interested in small, detailed parts. Using wood-like material is irrelevant since it's going to be painted over anyway and usually requires a larger nozzle diameter, reducing details further. I cut my teeth on commercial FDM printers that cost thousands, and bought a $350 Phrozen resin printer just to see what it could do. I was immediately blown away by the intricate details it could produce. Minimal sanding was the icing on the cake. My time is the most important commodity I have control over. Cons: Resin printing requires a dedicated, well-ventilated space and parts cleaning can be messy, despite the vortex cleaning stations available. 91 IPA is one consumable along with resin, but I've learned how to minimize how much IPA I need, using a discarded Windex sprayer, foam brush, and compressed air (60 psi from my air brush) to blow the excess resin from the .1 to .4 mm details. A half quart bottle of IPA lasts weeks instead of submerging the entire part in a plastic bin and contaminating a larger volume of IPA which becomes less and less effective over time and then has to be disposed of. For test fixtures and jigs, I still like FDM prints and farm those out to friends to produce my designs. Learning how to properly orient parts in a slicer takes time to acquire -usually through multiple failures (part of the learning process.) Resin printing is not plug-and-play as advertised despite new advances in printing technology. Being able to create parts with injection-molded precision at home is pretty darn cool though, and worth a look if that's what you need. My first resin model renders (for an RC submarine project) and the printed results were virtually identical. -

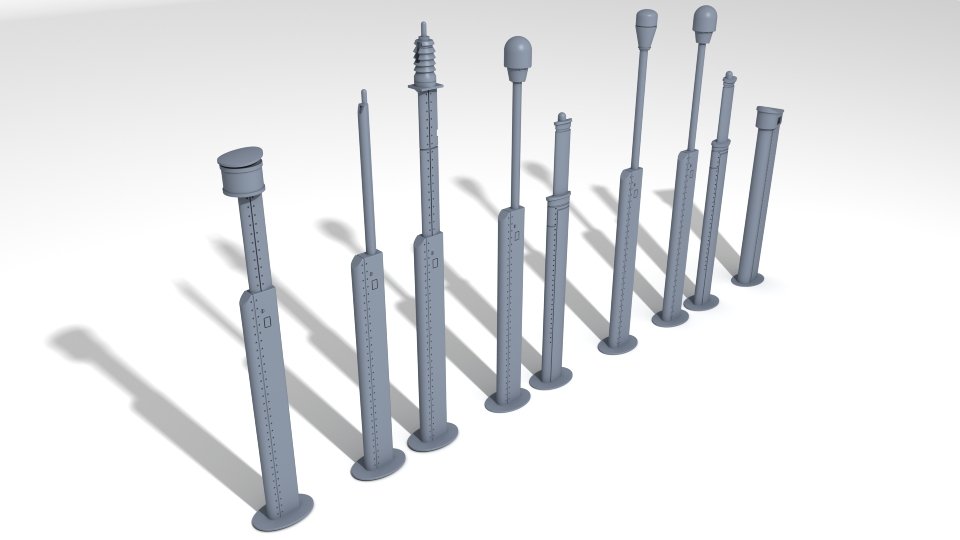

Decals for draft markings

CCClarke replied to g8rfan's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

I highly recommend this guy: Josh at BedlamCreations.com. He's my go-to guy for waterslide (white) draft marks. I told him what font I needed, and he scaled multiple sets for me. Easy to work with and reasonable pricing. CC -

Beginner CAD recommendation

CCClarke replied to krith's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

There could be as many recommendations as there are different software applications for beginning CAD users. Two of the most powerful and popular CAD applications: Fusion 360 has a free version and there is a lot of free training available. The same goes for Blender. -

Jeff, Are you a proficient SolidWorks modeler? If so, there is unlimited potential for use of a 3D printer in this hobby over "old school" fabrication, which is another art form. 3D printing vs established model building methodology has and will be debated for years. I believe there is more than enough room in our hobby for both techniques. A digital fabrication workflow from design to finished part has advantages that are hard to beat, especially being able to up-rev a design and repeatability. I know one master modeler who makes his own propellers the old school way, then makes a mold to cast metal parts. His excellent skills produce a first part measured in days, sometimes weeks as he solders the brass blades onto the hub with a template, then files the filets to a smooth finish. While I certainly marvel and appreciate the skills to produce parts this way, the time required to get the same effect with perfect tolerances can be drastically reduced with a digital design workflow, which is another form of creativity once digital design (or CAD) techniques are mastered. Time is one of my two most precious dwindling commodities, (the other being my health) so I prefer using the newer technologies available to enable me to make the most use of it. The additional time saved translates to more model-building opportunities. Once painted, I doubt most observers can tell the difference between a hand-machined cannon or cast part or a digitally printed part.

-

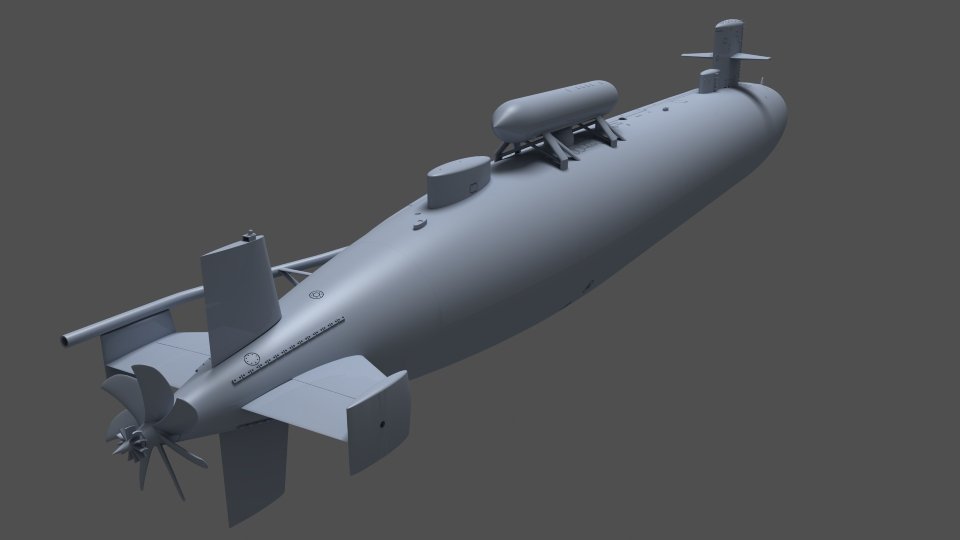

This is her in her second Ocean Engineering revision on the day she arrived for her homeport change from Mare Island to Bangor, WA in Nov '94. I rode her in when this picture was taken. As you can see, the hull is covered in SHT, (anechoic tiles) which ought make 3D modeling fun. The extra lengthening of the hull required larger fairwater planes for better depth control, so a pair of Los Angeles class planes were installed, higher on the sail.

-

3D printing material question

CCClarke replied to CPDDET's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

I use Phrozen ABS-like resin (compatible w/8k) exclusively. It flexes without shattering and handles reasonable (110 direct sun in AZ for hours) heat without warping. Highly recommended. -

Cold War madness

CCClarke replied to Martes's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

If you like that, consider: Command Modern Air/Naval Operations: Fully immersive, excellent graphics, with customizable, real-world scenarios and weapons.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.