-

Posts

128 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Sceatha

-

Hello Slowhand, 1m seems a bit odd indeed. Is the scale printed on the plans? I have seen that the Amati kit has 1/150 printed as scale. Which of course would give a distance of 3m between deck, which is also weird. A lot of the Amati plans are at 1/64. This which would give a height of about 1.3m between decks, which could be considered low but plausible.

-

Hello Keith, your metalwork has been a great education! Just one question (sorry if you said this already and i missed it). Do you find it necessary to treat shiny bronze with anything so that it does not darken/oxidize over time? Is something like that even necessary, or does bronze retain it's shine even without protection indoors? I have only just started working with bronze and have no experience on the subject, especially when the bronze is not blackened. Thanks! George

-

Thanks Druxey, I plan to use soapstone for bases more in the future, trying out more complicated shapes. It's a great material.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you all very much for the kind words! Of course Mark. See the photos of the stands below. I loved working with the soapstone. It carves so easily and holds detail so well that I decided to use it much more going forward, beginning with the stands for this ship. After sanding the stone had gotten a bit dull, so I used on it the same tung oil I use on wood.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks guys! That was my first ever build log (though not my first build). It's been a very beautiful experience. Thank you all for your company, support and your enlightening remarks throughout the build. Some of you are veterans here and maybe do not remember your first forum posts, but for me sharing my work for the first time in this step by step way has been an awesome and really educating process. George

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks guys! With the attachment of the oars its finally complete. It will now have to wait for a base and a lowered anchor with a kellet to be attached according to Mark's info above. But, as I said, this will have to wait, as I am moving houses towards the end of the year and it will be easier to pack and transfer it without the base. So, I declare it done for now and will post a few pictures with the base when that is done, is a few months' time.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

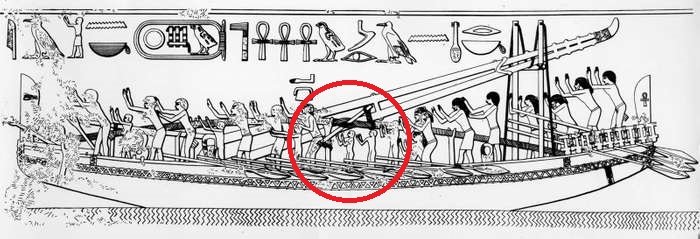

Now that the oars are ready it's time for their attachment to the ship. As is to be expected the ancient depictions do not offer information on how this was done. There is though something to work from. The Byblos ships on Sahure's grave complex clearly show some kind of rope was used: The oars in the image above appear to be retracted and ropes are visible loosely coiled around them. An image of a Nile boat is a bit more clear: The oar here appears to be lowered in the water and the rope is clearly extended. It seems to be tied around the oar at the wale and near the paddle. Could it be that the rope held the rope near the paddle and formed an eye at the wale that the oar could slide through when retracted? That would allow the oar to be used, retracted on deck when not in use and held safely so that they don't fall overboard. I am not aware of any similar oar attachments in a more modern context, but with my limited experience this does not mean much. I have learned so much from everyone's responses to this thread, that I hope someone can offer more info. Meanwhile I am going with my hypothesis, but am willing to alter it in the light of more evidence 😀

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you very much for the comments John, Mark and Christian! Indeed John, I had the same impression when I built the first one. It's something about that teardrop, pointy shape I guess. Now that's a great suggestion Mark. Along with the round stone weights, this could also explain what the archaeologists have come to call "small anchors". These are identical in shape to the large anchors, but are much smaller, too small to hold in place any kind of vessel. Once more, there are those archaeologists who have labelled those as temple offerings, or consecrated talismans for a safe voyage (once more the ritualistic acceptance of ignorance on the archaeologist's part). You have inspired me to add a "lowered" anchor, next to the bow, when the model is on it's base and include such a stone kellet on a secondary line attached to the main rope. Unfortunately this will have to wait, as the model will have to be boxed when completed, but before I make a base for it, anticipating a house move towards the end of the year. Thanks Christian! Growing up on the shores of the Mediterranean there were always stone weights and anchors around, some ancients ones, still being dragged out of the water now and then, and some used by fishermen even to this day.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks guys! Indeed, as John puts it, what on earth could they be if not that? Some writers have gone as far as calling them "bread offerings". A common practice in archaeology, if you don't know what it is for then it's probably ritualistic. Meanwhile onto the oars. Several depictions exist of ancient Egyptian oars and paddles and even some models found in tombs. Oars are almost always teardrop shaped. I decided to make mine from two pieces, cutting a slot to the shaft and adding a paddle with tapered edges. Luckily, for the sake of my sanity, this is nothing like a trireme, or Steven's beautiful dromon. Just 14 oars and 6 steering oars in total, all in all a couple of days work. The fact that a small ship with 14 oarsmen needed six steersmen probably shows how badly this ship handled under sail. Depictions show sailors literally hugging the steering oars, indicating that no tiller was attached to them like on later ships. I would think that the idea of attaching a tiller to the steering oars to get some leverage, when trying to steer the ship under sail, would be somewhat self evident, yet it seems that everything we take for granted had to be invented at some point. George

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

This is an awesome build Steven! I am relatively new to the forum and just got around to finally reading this thread beginning to end yesterday and today. Really educational, both historically and technically. George

-

Back to the regular programming indeed. And it is time for the mysterious and elusive "deck devices". At least that is what Landström calls them. Fact is nobody has the slightest idea what they were. The issue might be due to loss of information from the ancient depictions. Egyptians carved most of the shapes in stone. Then they used plaster to cover imperfections of the stone, or their own mistakes. Finally they painted finer details on the carving. Of all the above what survives today in most of the cases is just the stone carving, the plaster and paint having long detteriorated. All that survives of these devices is their basic shapes and the fact that they were tied with thick ropes and probably attached to long poles and/or the foot of the lowered mast. Landström's assumption is that they were stone weights that would be lifted with levers and attached to the foot of the lowered mast to weigh it down and help raise it, without having to pull the entire weight of the mast with ropes and risk one snapping, since dropping the heavy mast would probably damage the ship. I was initially a bit skeptical, as carrying heavy stones just to be able to easier raise the mast seemed a bit much. But when viewed in conjuction with ancient wrecks it seems more and more plausible. Most of the wrecks discovered carry an abundance of quite large perforated stones that arceaologists have labelled "anchors". They might well be anchors, since the ship needed stone ballast anyways and it is well known that to this day ships tend to lose a lot of anchors and spares are always needed. So why not ballast the ship with anchors if they are made of stone? And if you do, you might as well use a couple of the rounder ones to help you safely raise the mast. Since I liked working with the soapstone to make the anchors, I decided to go with this assumption and build the weights from sopastone two:

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks Steven for all the incredibly interesting info! It was great making the connection that what I was actually working on is steatite! I come from Greece and have seen many steatite sculptures both from the Byzantine and the Minoan eras, but did not actually make the connection, even though the Greek names for the stone are exactly equivalent to the English (στεατίτης and σαπουνόπετρα). Having to think between languages does make you miss the obvious sometimes! The soapstone was soft but extremely dense, and it does allow for great detail, it did not break or flake at all, even when cut with saws or drilled very close to an edge. I also loved it's hardness, which is just right so that it is quite sturdy (much harder than chalk) but can easily be worked with steel blades, felt in fact a lot like the harder pieces of basswood. My name is George by the way, Hellmuht just had the kindness to quote me above. The nickname is Old English indeed, meaning injurious person, or something like that (like sceathena threatum in the first lines of Beowulf), it's the same root as the modern English scathing.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

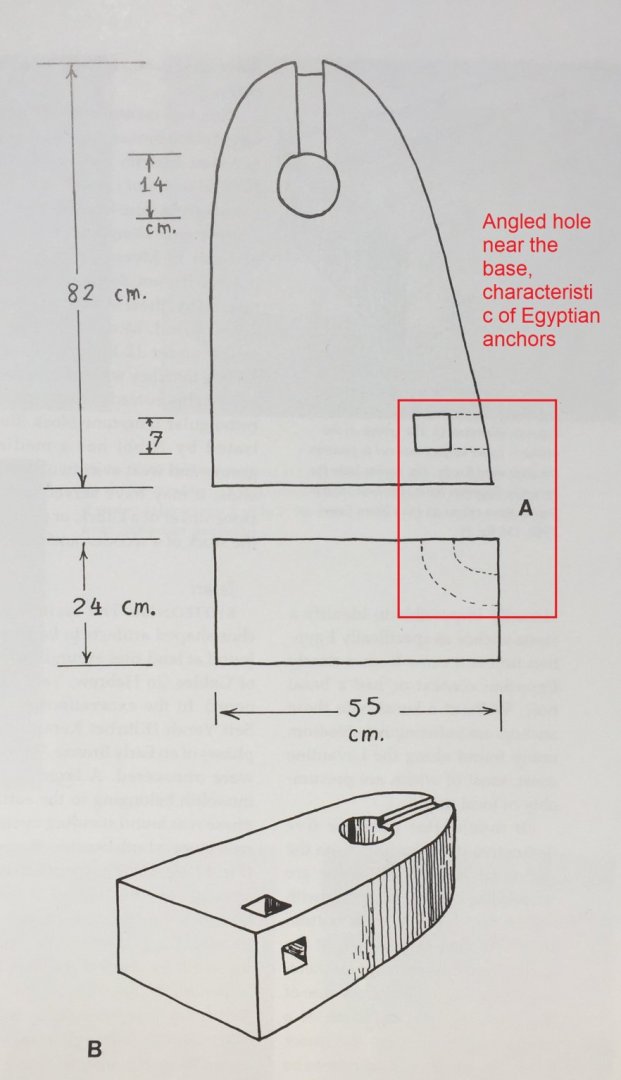

Definitely worth it Hellmuht, it's a fun ship to built! The tripping line sounds like the perfect answer Keith! Goes to show that actual practical experience (i.e. in sailing) can give much more useful insights than archaeology, when studying technological subjects, such as ships. It is in fact such a good answer that it makes me think why other seagoing nations did not have such secondary holes in their anchors. One possible answer to this could be found in the fact that Egyptian anchors were much better made in every respect, with much more regular shapes. That could mean they were the only ones that actually pulled up the anchors when wanting to depart. With ships at the time being quite flimsy and anchors being crude pieces of readily available rocks, it could be that most nations preferred to cut the anchor if the weather was even a bit rough, rather than risking damage to the ship. One of the bronze age shipwrecks found along the coast of Turkey, seams to have been carrying more than 150 stone anchors. When anchors are made of stone it makes sense to ballast the ship with spare anchors, in that way if you have to cut one and leave the only thing you lament is the length of rope you loose. In this light, it might be that nations other than the Egyptians did not bother with using a tripping line, thus their anchors missing the secondary hole.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks again guys for the comments! I decided to take a break from wood and focus on the anchor. Now ancient anchors are a very rich subject. As they were made entirely or mostly from stone a lot of them have been discovered across the eastern Mediterranean. Several were also reused as building material or as temple offerings, so there really are more than enough well preserved samples around. Although anchor technology was pretty basic (cut a hole in a big stone and pass a rope through it), anchors from different nations had enough unique characteristics to allow us to easily classify them. I will, of course, focus on Egyptian anchors. Below is the plan of a characteristic Egyptian anchor that formed part of pedestal for a stele, from Shelley Wachsmann's Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant: The basic characteristics of an Egyptian anchor were two: A secondary angled hole was dug near the base of the anchor, probably for a secondary rope that would probably allow for better handling of the anchor and better securing of it when on deck. A slightly angled base, to allow for the anchor to stand upright on an inclined foredeck. Now on to the building process. Since original anchors were stone, I decided to stay true to the method and carve my own from stone too. After looking around for appropriate pebbles and several failures (I began this even before I started building the ship), I came across a stone called French Soapstone by the merchants. It's apparently one of the minerals that talcum powder comes from and it carves beautifully. It's much harder than chalk, but carves easily with a steel blade. It's also incredibly dense without any pores or fault lines. Also quite nice looking, with a slight transparency and nice marble like grain. It's a particularly cheap stone, but it's widely used in stone carving, so there are a lot of small pieces, cutoffs from larger sculptures that are available online for next to nothing (that's how I got my flat slab). The only issue with carving it was the insane amount of dust (yes, much more and much finer than wood). Since I lack a proper den and am working inside the house, my wife was about to murder me, so I ended up filling a bucket with water and working with my hands submerged.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you guys for the likes and the kind words! Yes, it does seem so, guess we could call it an 'Egyptian windlass'! I went ahead to attach the mast. Now, Landstrom makes in his book a few assumptions on how the ship was rigged and about the shape of the sail. Yet the ships depicted in Sahure's grave have their masts lowered. It seems that lowering the mast was done when the ship travelled under oars, as the tall and heavy bipodal mast would completely distabilise the ship. All models of Egyptian ships I have seen have the mast raised, so I decided to be original and follow the ancient depictions, having the mast resting on the supports towards the stern.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Big day today, I finally added the hogging truss. The Byblos ships depicted in Sahure's grave complex are probably the oldest seagoing ship depictions in the world and the oldest known to depict what is clearly a hogging truss. The image bellow is from Egyptian Seagoing Ships by R. O. Faulkner. It shows the method they used to tighten the truss, by twisting a pole through the yarns until it was taught and then tying the pole to one of the vertical supports. The method is clearly visible on the ancient Egyptian reliefs: I got this right on the third attempt. In my first try I tried to be neat and twisted a length of thick rope on my miniature rope walk, planing to insert a pole in its middle afterwards. I quickly realized this was not going to work. As the truss was twisted by a pole inserted between the yarn in the middle, half of the truss twists one way towards the bow and the opposite way towards the stern (I really hope this makes sense). Second attempt, I decided to do it as the Egyptians did. I tied straight yarns, inserted the stick and started twisting. This made for a very irregular truss, with very irregular tensions among the six yarns, it really became scary when the hull began to creak. Third time was the charm. I tied the pole to the vertical support, and twisted from the center, first towards the bow, then towards the stern. By that time I had wasted about 4m of hemp rope, and as I am quite happy with the result, I will call it day. It still looks just a bit irregular, but I think that would actually be the case with the real trusses when twisted in such a manner.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you Keith! A very interesting process indeed. The lacings, combined with the great thickness of the planking (7cm to more than 15cm for Khufu's boat) allowed the Egyptians to disassemble their ships and carry them great distances overland to the Red Sea coast to be reassembled for journeys to the Land of Punt. Khufu's boat was in fact discovered disassembled, you could say in "kit form". That is absolutely true Mark! I found out the hard way, the site kept me up reading last night, literally until the sun came up this morning. Totally worth it, a truly great resource!

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks for the great info and link Mark and Guy! That is why I love this forum so much. Definitely a lot to dig through! Some of my main sources are included in the list, but there is a lot more there that looks very interesting. Luckily I find myself with a lot of free time these days. Meanwhile, I did some work on the bow. Next up, the hogging truss.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Started out on the steering deck. As seen in the reliefs from Sahure's grave complex it rests on a series of logs, probably to make sure those operating the steering oars do not trip on the hogging truss. Now this is where it gets really hypothetical: First, we can easily assume the deck was planked, making sure the helmsmen (all six of them!) did not have to balance on the logs. Second, the relief clearly shows the oars passing behind the short railing. Landström silently assumes this is a mistake, planking the deck in his plans from railing to railing. I had the chance to take a look at the plans for the Amati model which, despite the many glaring mistakes (especially in the shape of the hull), seem to have found an elegant solution that does not contradict the sculptures. The deck planking leaves a narrow space for the oars to go through behind the railings. This looks plausible, as Khufu's solar boat is also not planked from bulwark to bulwark, leaving a narrow gap on each side.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks all for your kind words! Did some soldering and finalized the lacings around the bow, as well as the rope that that holds the beam where the hogging truss will be attached.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

So, three days of 12 hour building sprints I have the hull almost completed. Unfortunately, I did something stupid. Since this is my first time recording a build log, I forgot in my building fervor to take step by step photographs of the interior lacing. Luckily, I have decided to leave part of the deck uncovered so the interior structure is still visible. Below is a general plan of the interior structure. This is mainly based on Khufu's Solar Boat, a more or less contemporary ship to the one I am building, but designed for river use. So here is the work on the interior, with battens covering the plants joints and laced from side to side. Since the thickness of the planks does not allow for the V shaped channels to be dug into the wood, without showing on the outside, the lacing had to be "faked". The lacing threads go through channels dug into the deck beams at the sheer: The ship has no keel and no typical frames. There is a number of relatively flimsy false frames, but their sole use seems to be to distribute the pressure of the stanchion that hold up the long plank that supports the deck beams at their center: Decking is also almost done. Based on the decking of the Khufu ship, the Egyptian did not shy from beveling the planks to sharp points, despite the loss in structural integrity. Supposedly their need to preserve as much of the rare wood's original length was greater.

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Got some time today to work on the yards. Especially the upper yard with the characteristic carved yard ends. The shape of the yard is based on contemporary stone carvings of river boats: Started with the carved ends, made from two pieces of linden each:

- 81 replies

-

- egyptian

- byblos ship

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.jpg.32ac8d7978d0813c0fb2a83e81f05f79.jpg)