-

Posts

1,648 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by SJSoane

-

Thanks so much, Cisco. I struggled a little to explain some of the issues, I am glad it eventually made sense. druxey, I wondered how you did your beautiful fretwork, and the answer of old school piercing and shaping is just as astonishing as the quality of the product! You continue to set the highest bar for us. Your work also points out that old school techniques could have accomplished the delicate filigree work on the second Bellona model. I wonder why they chose to render that detail as crudely as they did, when every other detail is highly refined and well crafted. The big holes in the white stanchion covers are not even accurately located and drilled. I cannot imagine that this detail was an effort to accurately represent the detail on the actual ship. Maybe they were running out of time on a deadline, maybe some original good details were damaged and later replaced later with this cruder version. A lot could have happened to that model in 240 years.

-

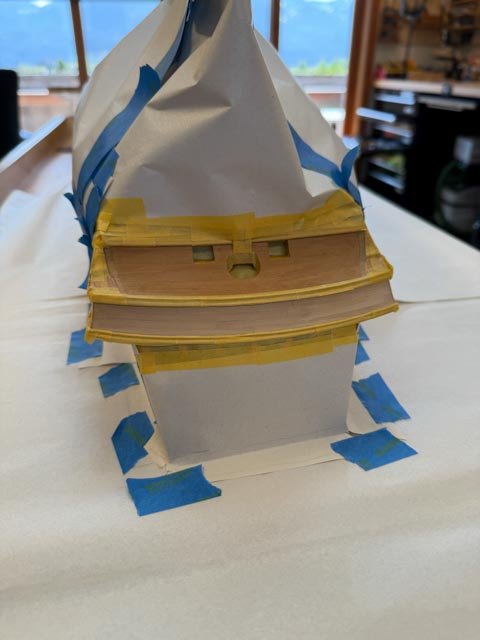

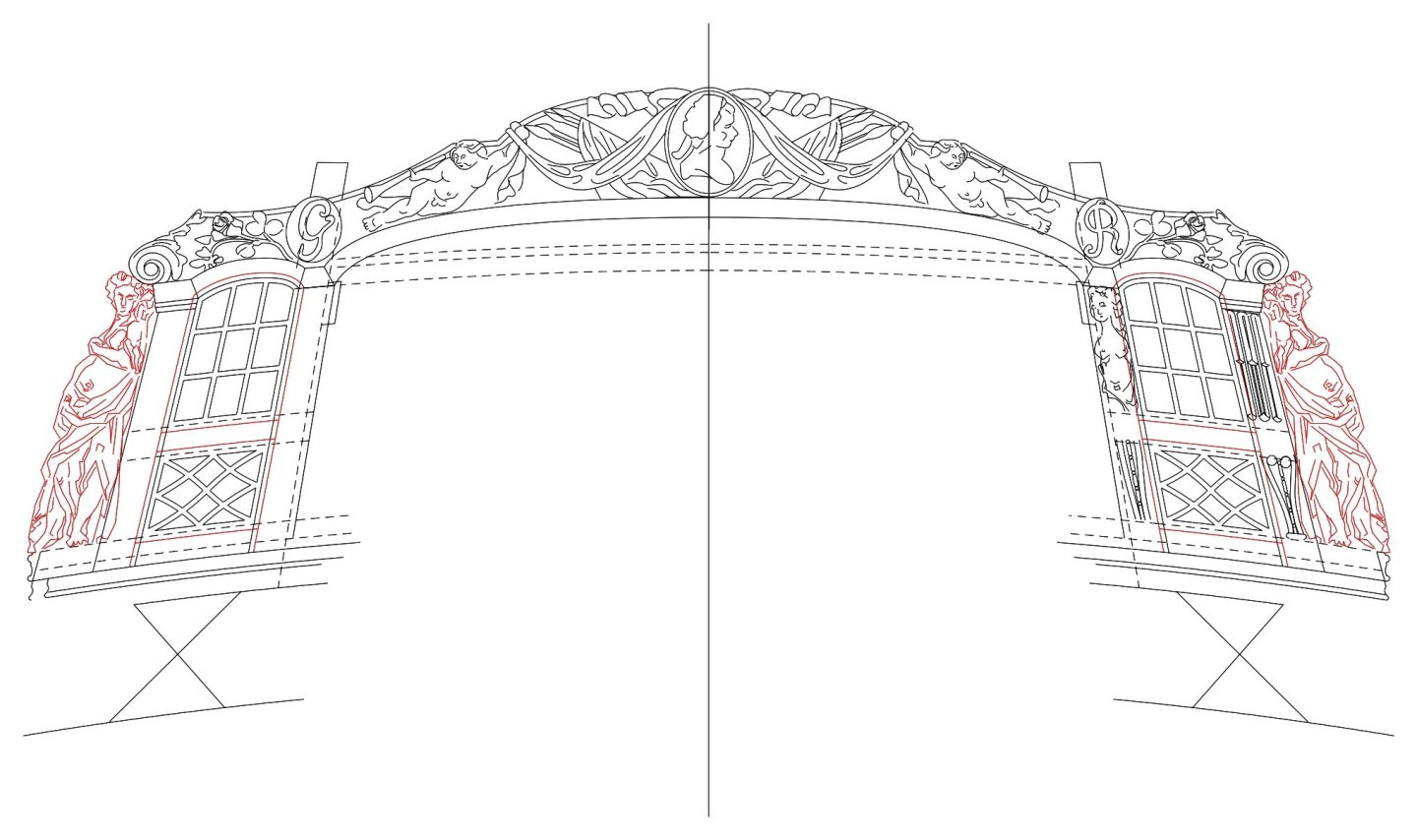

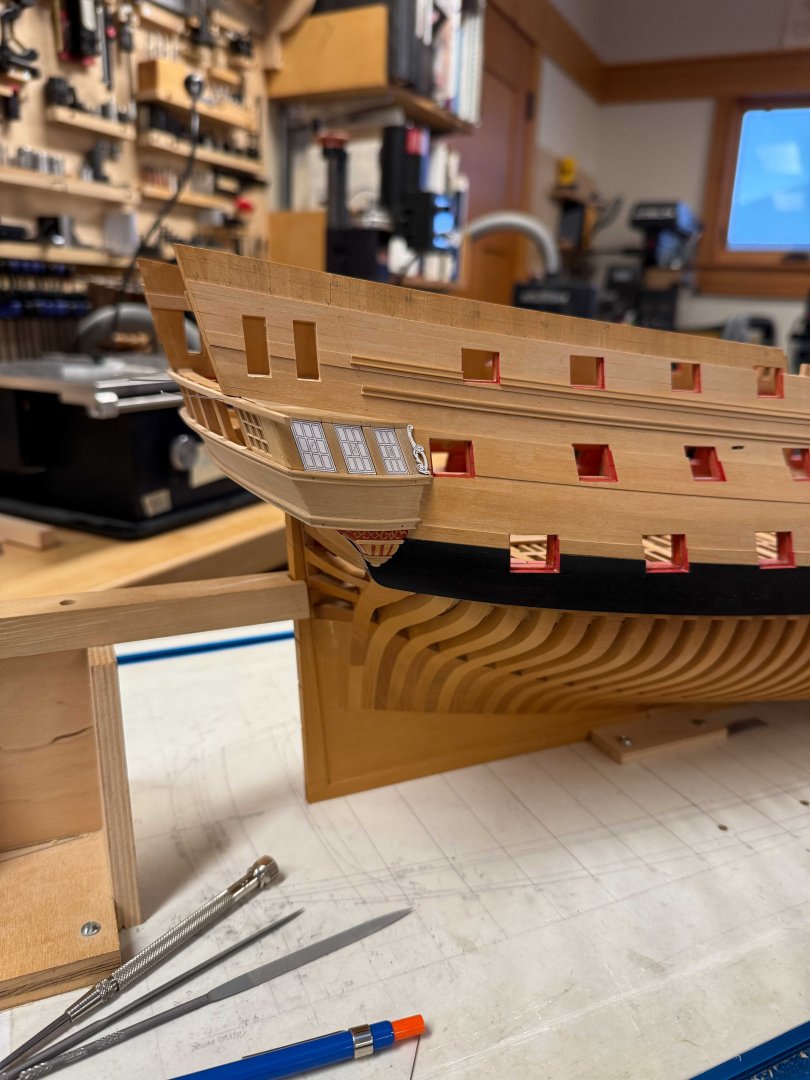

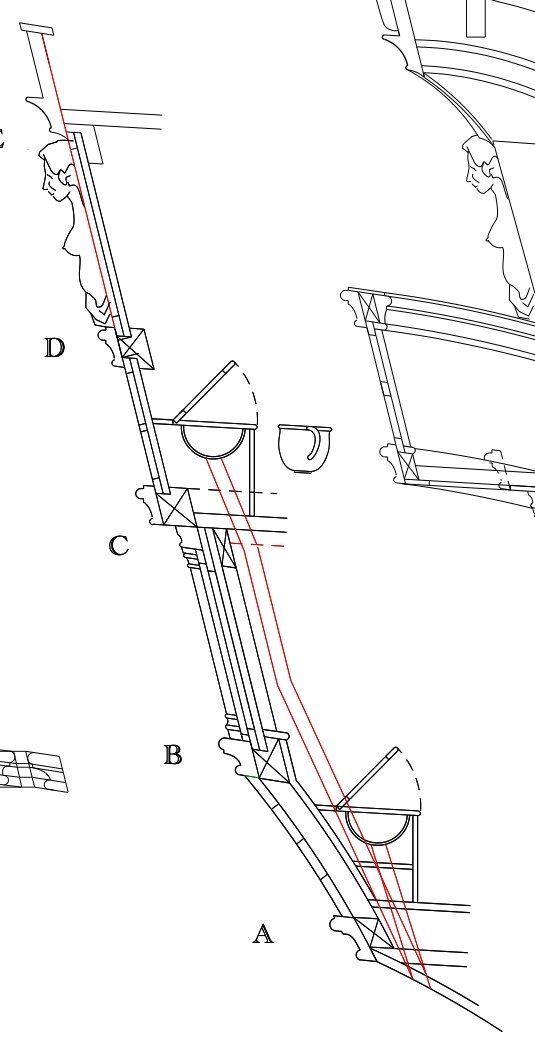

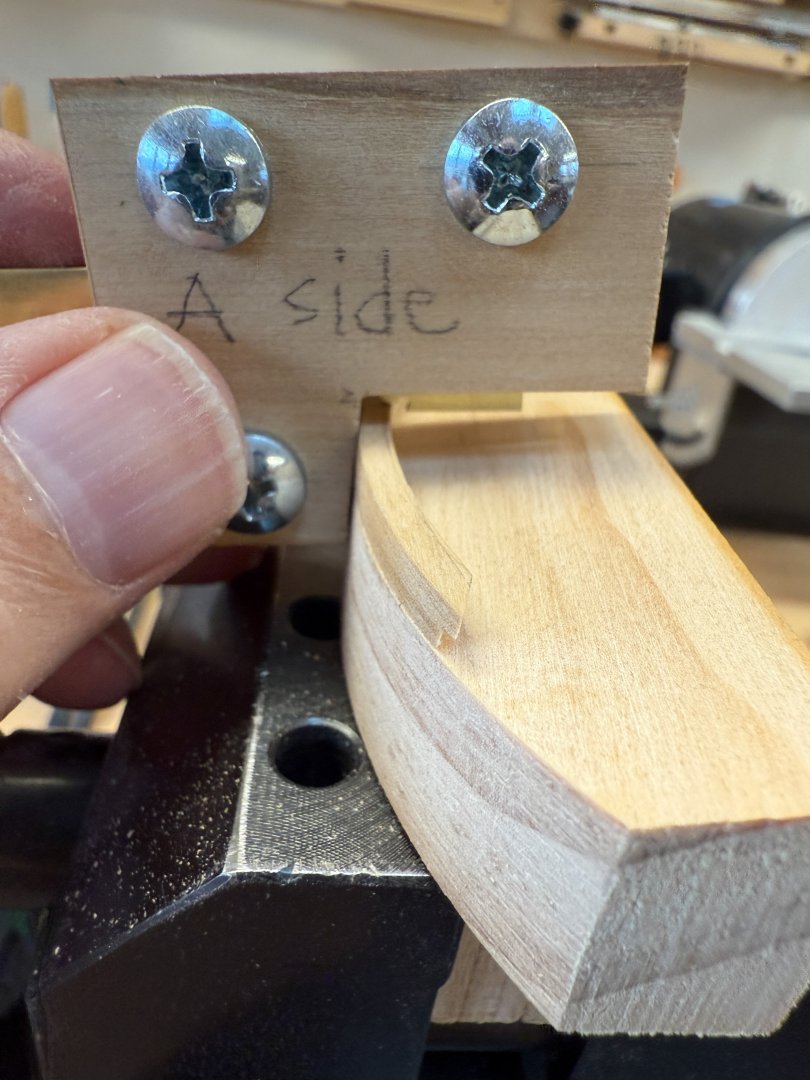

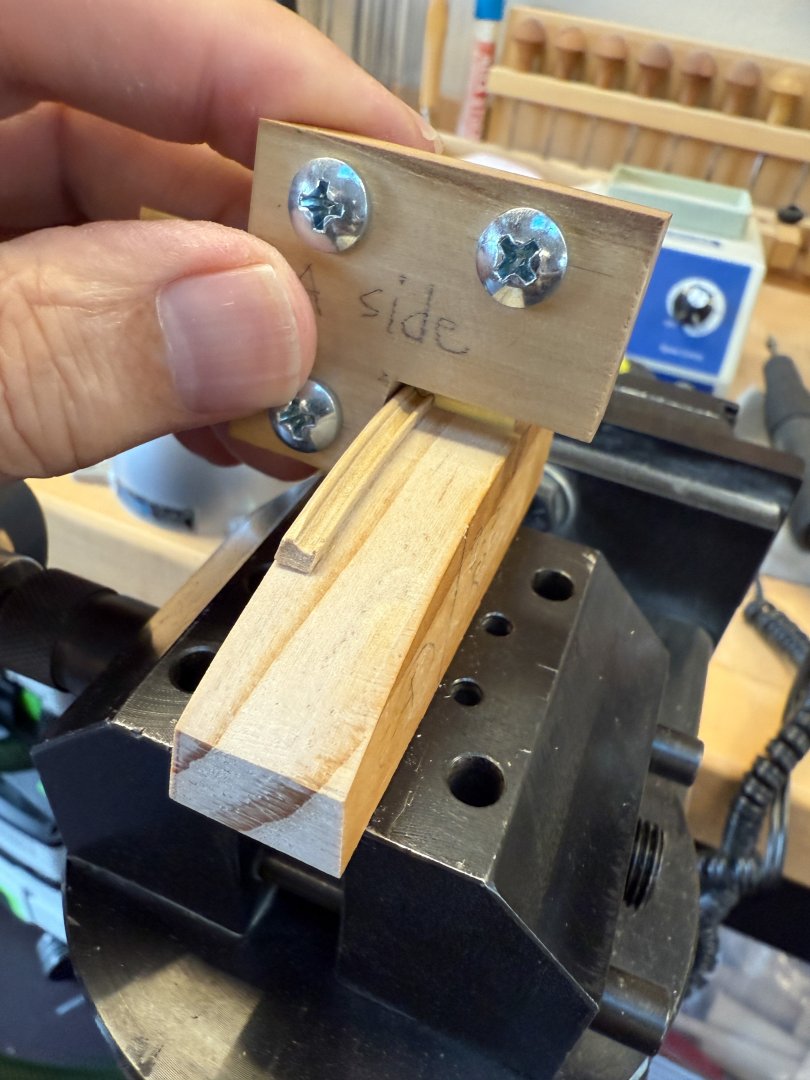

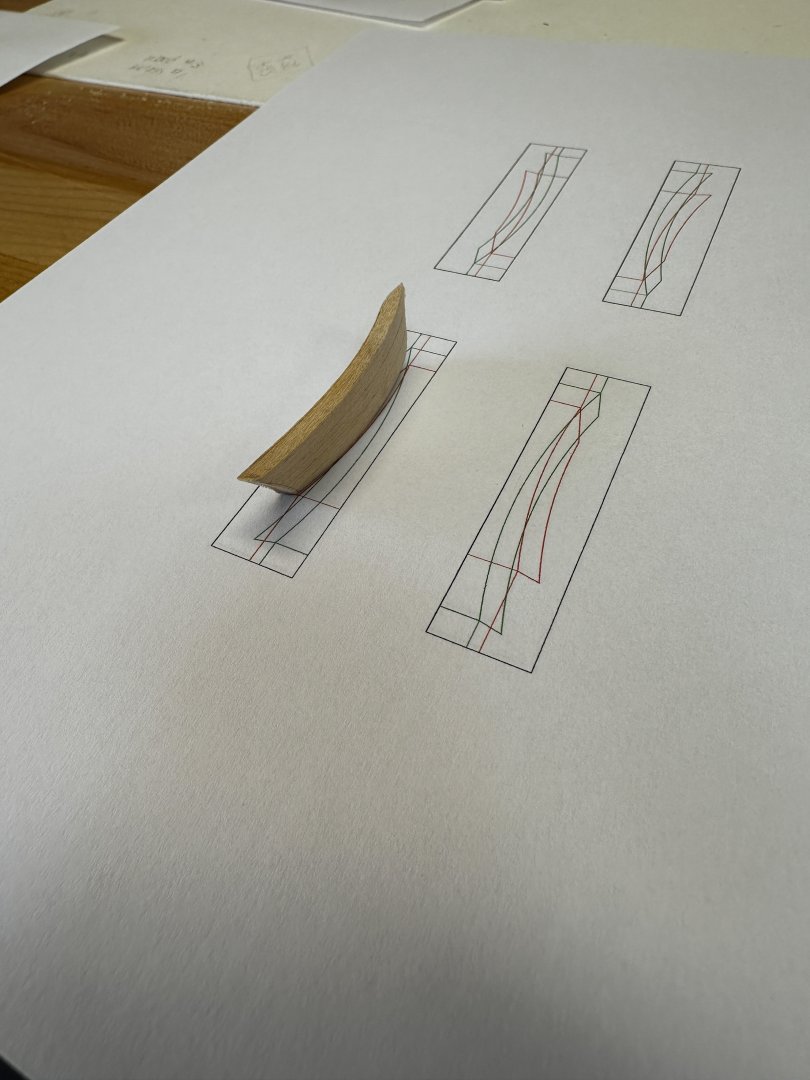

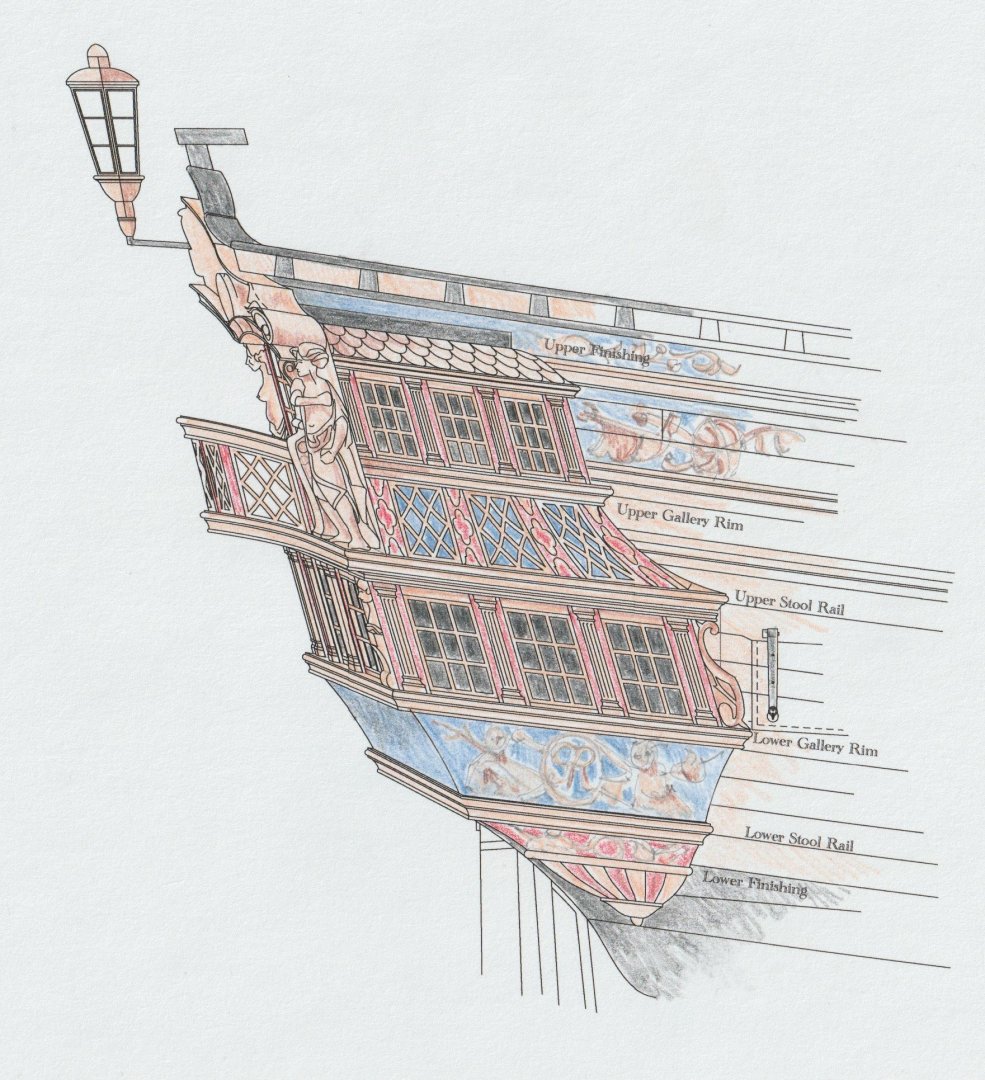

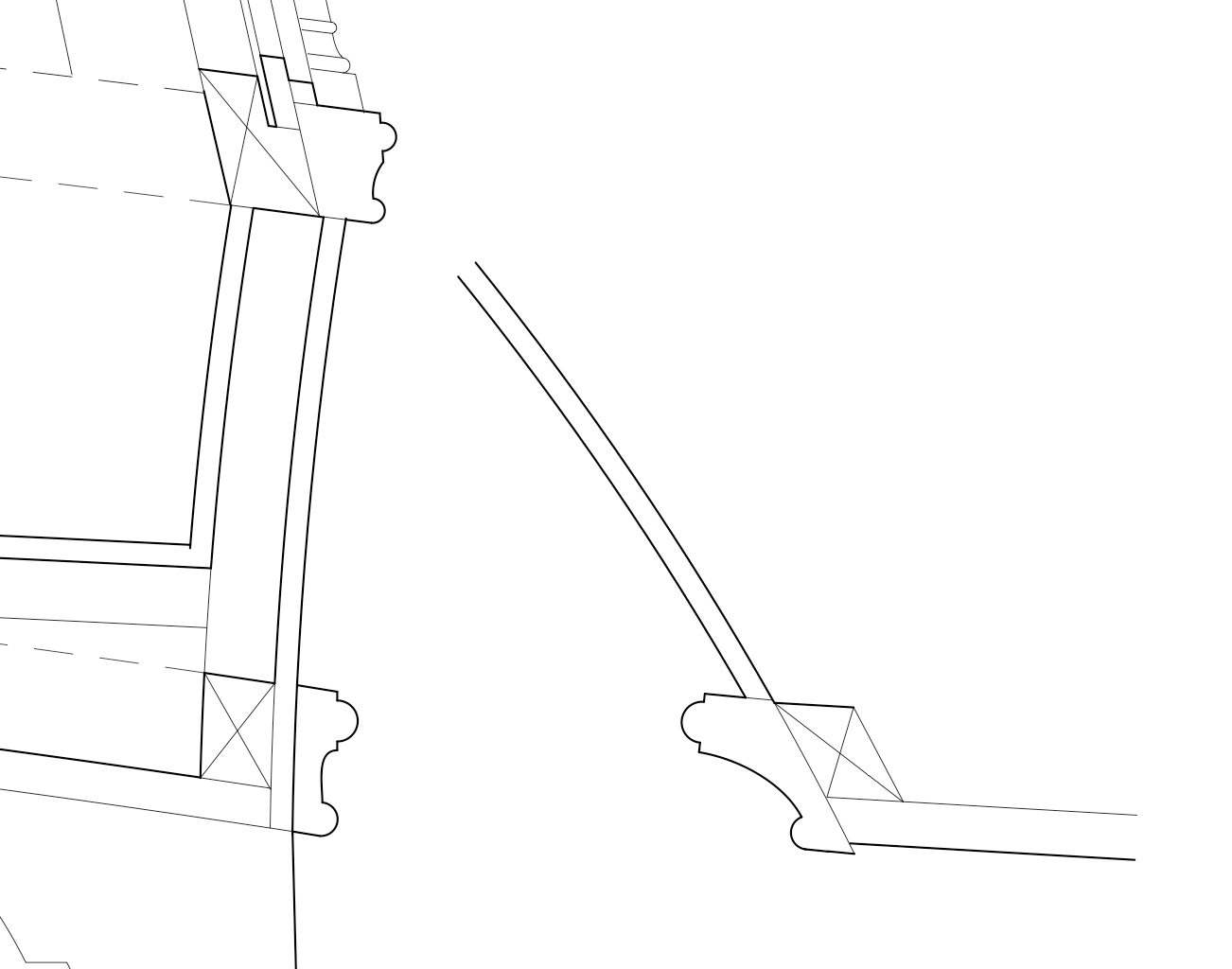

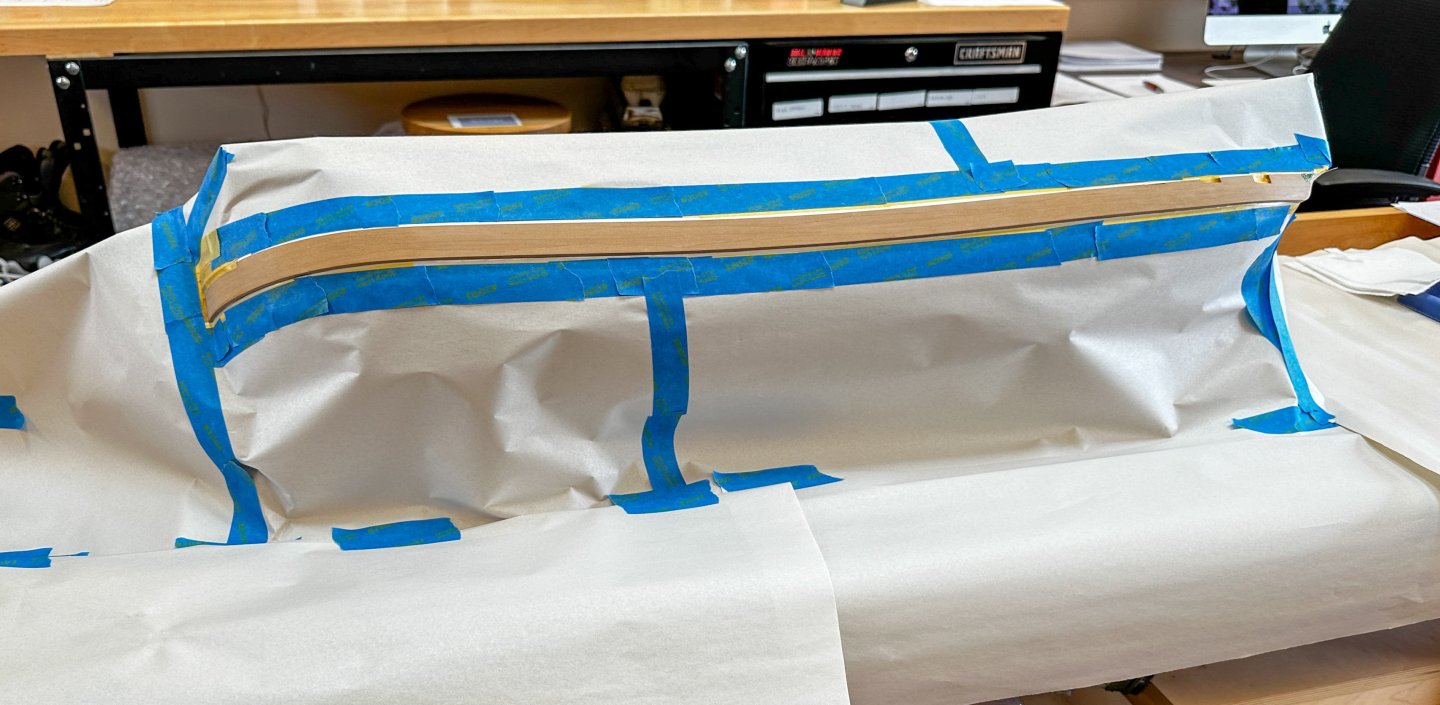

Time for an update, even though things are in flux. I have finally tackled the balcony and the fretwork on the quarter galleries that correspond to the fretwork in the balcony. First a bit of a re-visit on this detail that I knew was going to be the most challenging part of this build so far. In the images below I am showing the first Bellona model built ca. 1760 followed by the second Bellona model representing the ship after its major refit 20 years later. My project is reconstructing the Bellona as she was originally designed, as shown in the original admiralty drawings and in this first model. However, the first model did not show the quarter galleries, and so I have had to interpolate what the original quarter galleries might have looked like, related to the original balcony and then to the quarter galleries shown on the second model. So let's look at these more carefully to see what is the same and what is not. The original model shows a very distinctive fretwork on the face of the balcony, which we can assume was meant to be open as seen on the second model. The vertical stanchions in the original model are painted red, with a covering filigree subtly projected out forward of the fretwork within the rectangular panels. Note also that the first model balcony sweeps in a gorgeous serpentine curve from one side to the other. the second model, on the other hand, curves the balcony into a sharp corner one panel in from each side. It took me a long time also to realize that the first model is wider outboard of the outermost rectangular panels, with a more substantial bracket between the panel and the carved female figures. I saw the necessity of this extra width when I tried to reconcile the stern design with the original admiralty plans. The extra width was needed to make the quarter galleries big enough at their after ends. This then had a knock-on effect for the windows below. which also needed the extra width. You can see my interpretation of how this might have worked in the line drawing below, a little bust on a pedestal. Final thing to note before leaving the balcony. The original model has this beautiful filigree detail over the red stanchions. The second model did not even attempt to recreate this, choosing instead to drill crudely arranged holes in white panels. I had sympathy for their plight, attempting to cut these exceptionally fine filigrees. My own efforts at this failed spectacularly. Then I thought, I'll bet Chuck and his laser cutter can accomplish what the 18th century model builders had failed to do. Before looking at this in more detail, I'll turn to an overview of the quarter galleries themselves. Following are the quarter galleries on the second model. The model builder continued his scheme from the balcony, with stanchions represented as crude drilled holes in white panels. I decided in contrast that I would continue the first model scheme of fine filigree over red stanchions, keeping the dark blue paint behind the rectangular patterns. I drew up the quarter gallery pattern with this idea, and it is shown here as a colored pencil paper pattern: While working on this, I began to realize that this entire panel was a different shape compared to the one on the second model. You can see that the second model panels are much more rectangular with more upright sides, mine were turning out with more extreme sloping sides. And mine had a much stronger sweeping backward curve at the fore edge. What was going on? It took me some time finally to realize that the first Bellona model and admiralty drawings show a much smaller upper quarter gallery off the quarterdeck. Here is the original admiralty drawing immediately below. Note the more extremely curved forward edge of the panel between the lower and upper windows, needed to reconcile the larger windows below with the much smaller windows above. Compare this to the quarter galleries in the second model shown above; the windows above and below in the second model are almost the same size, needing a less extreme slope from the one to the other in the fretwork panel between them. I think we can assume that when the first captain saw that the quarter gallery of his brand new ship was substantially smaller than the one below shared by his officers, he strongly suggested that this would need to be rectified in any subsequent re-build! Pressing on, I worked up the drawings of the panels and sent them to Chuck, who returned the most beautiful fretwork panels and delicate filigree stanchion covers. I am showing them here loosely located; they still need to be glued down to the concave surface to pull them in more tightly. And I still need to paint the blue backgrounds behind the fretwork panels: These needed sanding down in thickness from the thinnest plastic Chuck could provide. I did this by trapping the plastic in a frame as thick as the final desired thickness, giving me a gauge for sanding down to the frame: Meanwhile, I started work on the balcony itself, so I can draw these final panels and stanchions for Chuck's laser magic. It frankly took a great deal of trial and error to craft the geometry of the serpentine curve. It needs to fair into the curved side panels and then reverse its curve twice. Also, the upper balcony railing is narrower in athwartship width but still needs to slope back enough in its narrower space to maintain at the center of the balcony the backward slope of the side panels. I could not visualize how this would work. I tried carving a blank out of basswood, which helped, and then built a card blank multiple times to keep refining the curves until they seemed right. Then I worked out the actual geometry in plan: This gave me the patterns for roughing out the lower and upper moldings, shown here. the blocks are spacers to keep the two moldings parallel to each other while I refine their fit against the side panels. These are still much oversized, until I get all of the parts to talk to each other handsomely. I intend to trap the laser cut fretwork in rabbets as shown here: I now need to create an accurate pattern of the shape between the two railings, to draw the fretwork and filigrees for Chuck. The saga continues! Mark

-

Thank you, Frank, for your kind comment. And druxey, I think the removable or hinged rudder cover is an interesting idea. It would be way easier than removing the entire cover, and a tackle rigged over the rudder head could pull straight up. Regarding the model not the real ship, I found it most convenient to construct the rudder cover as one unit, to keep things square and shipshape. The five sides would have been difficult to keep in alignment to each other without the top as a guide. So my entire unit will have to slide out now that I have the beginnings of a quarterdeck above that will prevent pulling straight up. I notice that in Rob Napier's Legacy of a Ship Model, pp. 83-85, he and David Antscherl speculated on a similar problem in the Princess Royal model, with a rudder cover struggling to accommodate shipping a rudder once the cover had been installed in the model. Always fun to see how our 18th century predecessors sometimes struggled with the same things we struggle with!

-

My main goal now is to construct the stern balcony enough to get drawings to Chuck for the fretwork. But before that I have to build a stub deck at the end of the quarterdeck. But before I can do that, I had to build the stern of the upper deck with the rudder cover and benches, since they will be covered up once I install the stub deck above. And before I could build the rudder cover, I needed to mock up the rudder head to ensure it will turn freely in the rudder cover. And on it goes..... So, here is the mocked up rudder head, checking clearances: And then the rudder cover itself. Note in the first photo, I somehow built it too wide. The second photo below shows the trimmed down version. I had to selectively deconstruct the cover, then slice out the excess, and reassemble. It reminded me of chopping tops for hot rod models when I was a kid! I discovered that if the rudder cover top surface stays below the level of the stern lights, there is not enough room under it to ship the rudder. It will have to be removed and then reinstalled after the rudder is in place. So when I built the benches on either side, I made all of this a slide fit so the rudder cover can be taken out later to ship the rudder when I get around to building it. The benches proved to be unexpectedly difficult to build. They had to accommodate different curves at different levels, since this is all sitting on the fore side of a convex upper counter whose curves are different from the upper deck upon which the benches sit. It was a lot of tedious trim and test, trim and test, for several days. But now it is done, ready to be covered up by the quarterdeck stub deck above. At least I could get some sense of the standard of living for the officers. Not bad, sitting on the bench, elbow on the window sill, looking out at the sea through the wall of windows.... Mark

-

druxey, scrubby, Albert, Chuck and Marc, thanks so much for your kind comments. I am feeling so slow on progress these days, even though I am working at it pretty diligently. It really helps keep me going to get these great notes of appreciation from all of you! I cannot sing the praises of Chuck's work enough. Working with exceptionally tight tolerances, his window frames fit like a glove. The filigree work above is going to be an even greater exercise in close tolerances, and I am still working on how to captures these in rabbets strong enough to hold against a surface curved in two directions. I'll post some drawings when I get a little close to a final idea. And I continue to be amazed at the design of the Bellona in all of its detail. Those guys really knew what they were doing! Mark

-

A quick update. I finally installed all of the upper deck lights, with the red cover plates holding them in place with the help of a little LockTite Extreme glue. This was necessary for bonding the plastic window frames to the wood, giving a few minutes repositioning time to settle everything in the right location. I had considered using superglue, but it has no leeway with repositioning time. I placed mica behind the frames for the glass. It was easy to cut, and as thin as the windows ought to be in scale, greatly facilitating the construction details. Chuck's laser cut window frames look fantastic! Thanks so much, Chuck. I still have to construct the architectural columns in the centers of the red cover plates, and I am showing here some paper placeholders for later carvings. But I have decided to move onto the balcony for now, which will probably be the most challenging part of this build. It has open fretwork between stantions, and the whole thing is a serpentine curve, as seen in the original 1760 model (here the fretwork is carved out of a solid blank; they are open in the second model which I assume is the intention of the model shown here). Mark Chuck already laser cut the fretwork for the side panels, as seen best in the last photo below the curved top window. This again shows the beauty and delicacy of Chuck's work. this same pattern will hopefully run across the balcony, and then around the quarter galleries at the same level.

-

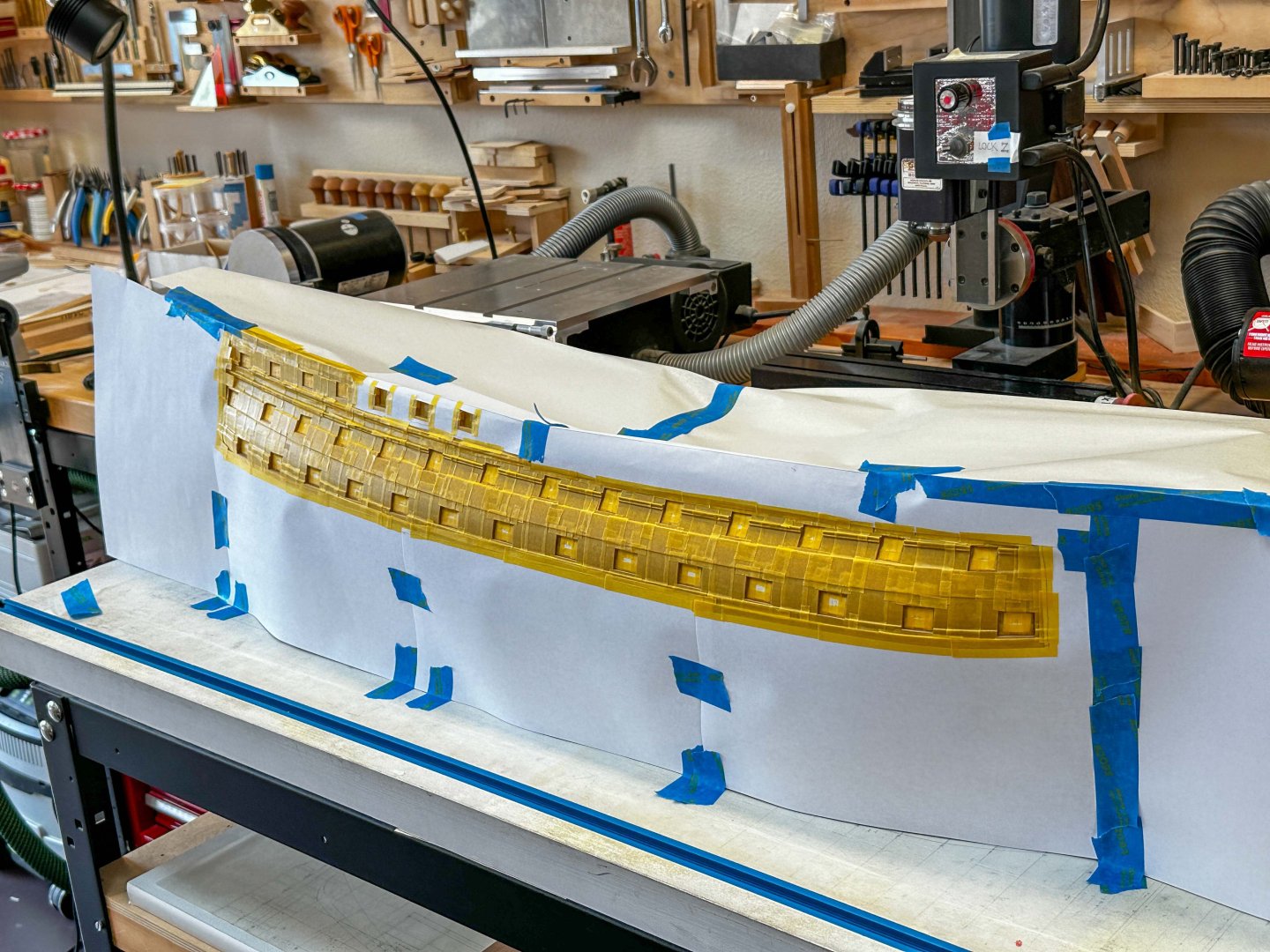

Thanks so much, everyone. This was a major hurdle for me, thinking about it for many years, and now able to move forward. A couple more thoughts, for those working on paintings like this. 1. Using frisk to lay down the base yellow ochre actually accomplished a couple of things. Not only did it allow a smooth application of airbrush paint, but it also solved part of the problem of getting the design transferred to the hull. Because the frisk is based on an accurate drawing, there is no need to worry about sketching in the design on the model itself, trying to keep faithful to proportions and sizes. It is as accurate as the drawing used to cut the frisk. 2. To get an accurate underlying drawing, I scanned photos of the painting on the original Bellona model, and imported them into my CAD software (HighDesign 9 for Mac). I then resized them to approximately the correct sizes and printed them. When I cut out each print and laid it onto the hull, I could see where the shape needed to be adjusted for more or less curve, a little wider or narrower. I would then make these adjustments to the CAD drawing, print again, adjust and so on until the CAD drawing was an accurate fit. Then I knew the frisk would fit well in its assigned space. 3. Regarding airbrush paint, I also started with Vallejo, which is highly regarded by many modelers online. But I also had problems with these clogging my airbrush (Harder and Steenbeck Evolution). Although I tried a number of suggestions for thinners seen on YouTube videos, nothing seemed to work reliably for me. It may be that I did not work out a good way of mixing the paint and thinner, or it may be that spraying on wood rather than plastic makes a difference. Golden High Flow paints worked without thinning, which does allow for a greater consistency in what is going to happen when you pull the trigger. And they match the Golden Fluid acrylics for hand painting. 4. As David Antscherl pointed out in his section on painting in the Fully Framed Model, the base layer of yellow ochre is a translucent paint, not opaque. So when spraying or hand brushing yellow over Prussian blue, the resulting color goes green. David's advice of mixing some white into the yellow ochre for hand brushing helps, while a number of layers of airbrushed yellow ochre eventually goes opaque. They dry so quickly that it is possible to get an opaque finish in one session of airbrushing. I look back and wonder why it took me so long to work out this painting business; and now I remember the many experiments, dead ends, different products.... Mark

-

HI everyone, A long time since my last post. I realized that I was getting to far ahead of myself, building up the stern with everything just pinned. I needed first to paint the lower and upper counters before I could actually start assembling things. And learning how to paint the friezes was a major learning curve! I greatly followed David Antscherl's advice on painting in the Fully Frame Model, vol. II section 7.26. It was exceptionally helpful for everything from paint and brushes to technique. Alas, I discovered after a great deal of experimentation that hand painting alone did not work well for me. Particularly for the background Prussian blue and the letters "Bellona" on the stern, I needed a way to get things sharper and more even in tone. So, I turned to my airbrush. I masked everything but the counter and sprayed away. I glued artist's frisk onto a print of the upper counter letters and frieze elements (a woman riding a sea monster, a man riding a galloping horse). I could then turn the frisk/print every which way on my light table, and very carefully cut the frisk with a scalpel. I then attached the frisk and sprayed everything that would be the yellow ochre base for all of the frieze work: I then used white graphite transfer paper to trace the rest of the pattern onto the surfaces: Then following David's advice of painting highlights and shadows on the basic forms, I eventually got to an imperfect copy of the original Bellona model: I learned to admire those original model builders for their painting skill. Try as I might, I just could not get to the same level of skill. But as good as I can do! So, moving on to actually gluing together the stern! I did learn a few good things that I will pass on for anyone else attempting these kinds of friezes. First, after trying a number of airbrush and hand paint brands, I settled on Golden. They have the same colors in different densities, for airbrushing and hand painting; the colors match the historic colors I was looking for; they come in plastic bottles with ball bearing inside, for mixing. They spray without problems through my airbrush. And they are highly regarded in the artist community. Second, I struggled with the acrylic paint drying too quickly on the palette when I was trying to mix colors. My son introduced me to the model gamers' favorite tool, the Army Painter Wet Palette. This tray holds a water saturated pad, upon which is placed a parchment sheet. Paint mixed on top of the parchment can stay wet and mixable for as long as 48 hours. A huge help! A glass of wine tonight in celebration, and on to assembling the stern! Mark

-

Hi everyone, Sorry for the long silence; other things going on! To catch up. First, Der Boss, thank you for your kind comments. Slow and careful keeps me moving along! Trevor, thanks for the reference to Roberts. I haven't seen that, but I do have the facsimile book and set of plates for Steel's Naval Architecture. I have used that to help with several questions of drafting, but could find nothing on the curved surface between the upper deck and quarter deck windows on the quarter galleries. And Gary, good to hear from you! We old timers go back a long way on our 74s! And druxey, thank you for your list of tools and materials you used. I did a little test fret-sawing boxwood, and if I find myself going down the route of fret sawing, I have determined that wood is too crude for the very thin cross grain pieces (see below). I can see plastic would be a much better material, no grain to deal with. And once I saw that plastic might be the right material, I mocked up the curved surface in basswood to see just how sharp the compound curves would be. This would be to test whether glue would be enough to hold flat plastic against the curved surface. And the surface turned out to be less curved than I thought. The front edge sweeps back at a good angle, but at any line drawn between the upper and lower moldings, the surface curve is gentle. So for now, I will explore having these laser cut. I first need to reinstall everything with the final windows (coming from Chuck, thanks so much!), and then carve the final curved surface to measure and expand for a true elevation of the fretwork. Mark

-

Thanks, everyone, for your comments. Kevin, intriguing idea about 3-D printing, but I don't think I have the skill to work up a 3-D drawing of the double curved quarter gallery surface. It is no known regular geometrical shape, and would have to be built up in sections and faired like a hull. I may come back to this if I can't figure anything else out. And thanks for reminding me of Marc's fabrication techniques. Marc, thanks for thinking about this. Your techniques could well provide a way to build these forms up, rather than attempting to pierce saw them out as a whole. My first experiments showed me some problems with attempting to cut these out of boxwood--grain runs across some of the thin pieces, doesn't have any flexibility--and so I may have to explore other materials if I go down this route. Or, maybe I just make up individual strands with the grain running the length of the piece, and then glue them together at the intersections. This would be more like a mesh that could settle onto the curved form behind, because it could slightly bend at each joint. druxey, I greatly admire your fretwork on the Polyphemus. That is exactly the same kind of fine delicacy of inter-weaving lines that I need to produce. And your's is flawless! Did you fret saw those out of boxwood as individual strands, or pierce-sawed some of them as panels? Sailor, thank you for your kind thoughts. I admit that this challenge slammed on the brakes for a bit, but I remind myself that I have always found a way forward when this happened in the past, particularly with help from this forum. And Greg, like you, I sometimes reflect on the astonishing skill of the 17th and 18th century model builders, especially given their technological limitations relative to our age. Like the old saying about Ginger Rogers--that she did everything Fred Astair did, but backwards and in high heels--the original model builders often did more with less than we have. One can hardly believe humans are capable of such fine work. I also find myself sometimes channeling the original shipwrights, when I am fashioning a piece and realize that a number of people did exactly this same thing two to three centuries ago. What a great hobby. Mark

-

Hi Alan, Feel free to use the expanded sketch of the stern works. Amazing that it would fit both the Bellona and Bellerophon, but then they were sister ships. And I guess you and I are building pretty close to accurate.... So maybe instead of pierce sawing, I temporarily glue a thin layer of wood to a curved backing, and carve down like a bas-relief all the way through. When it is released from the backing, it will look pierce sawn and pre-fit to the needed curve. I will try to think this through.... Mark

-

HI everyone, I have hit one of the most challenging parts of my Bellona build, the fretwork on the quarter galleries and balcony rail. Here is photo I took of the first Bellona model a number of years ago, showing the serpentine curve of the balcony I am intending to reproduce: And here is a photo I took a few years ago of the second model, showing how the balcony railing is actually pierced, not solid. and this shows the fretwork on the quarter galleries, which is not shown in the first model. I had been planning to have these laser cut from plastic, based on my drawings of the correct shape and proportions of each frame (thanks to Chuck!). But when I mocked up the double curved surface on the quarter gallery, I discovered that these fretwork panels will have to conform to some very warped surfaces. I am not sure plastic with very little gluing surface can be reliably fastened down by glue alone. I toyed with capturing them in rabbets behind the horizontal mouldings, then I realized that this would not exert enough pressure at the extreme edges to press them against the warped surface. This led me to thinking about maybe pierce sawing them out of a more pliable material, or maybe pierce sawing them out of blanks that are already curved to the correct shape. Or, maybe having them laser cut out of a more pliable material. I tried an experiment of pierce cutting these out of thin boxwood, but the grain was too course for these thin filaments, and the piece broke when I tried to curve it. It looks to me like the second model pierce cut these out of probably ivory, which would solve the problem of a fine enough grain. Maybe Tagua nuts since ivory is not an option? I even thought about pierce sawing them out of thin metal that could bend to the warped surface, then painting them a tan color. Any thoughts about any of this? Best wishes, Mark

-

Hi Vossiewulf, Yes, the Knew Concepts saw was a game changer for me as well. I was hesitant to try the Knew Concepts metal bench pin, fearing dulling my blades when accidentally cutting into the pin. But I tried it and will never go back to a wood bench pin. This pin gives exceptional stability when sawing very small parts. I periodically slide the piece and the saw back and forth sideways until I find the center of the slot, and then line up the cutting line with the slot. I rarely hit the metal any more. I also finally figured out, after too many years of struggling, that the size of the blade really matters for smooth and accurate sawing. Relative to the thickness of the wood, I read a rule of thumb that at least 3 teeth should be in the wood for smoothness, and at the other end, not too many teeth because it goes very slowly. I tended to use whatever blade was last in the saw, no matter what the thickness of the wood, and the results were not great. Once I decided to size the blade to each piece of wood to be cut, I drew up some charts and glued them to my saw blade storage containers. These show the thickness of wood along the top, and the details of the various blades down the left side. The blue squares show the range of blades suitable for that thickness of wood. I may redraw these soon, because I have found after using these for some time that I am always choosing a finer blade than my chart would suggest. Maybe that is a consequence of the wood I use. I stick a bent piece of wire into the hole of the blade I am currently using, so I can easily put the blade back in its proper place when I switch blades. That means I am mixing up new and used blades in each hole, and I randomly choose one each time. If the blade I choose seems dull, I toss it and grab another. This hasn't happened often. These blades really hold up. There is only one blade that overlaps in size between the Otto Frei jewelry saw blades on the left, and the Pegas fretsaw blades on the right. Together they accommodate wood from .016 to 1 inch. Up at the greater thicknesses, I tend to use my bandsaw. Mark

-

hi everyone, Druxey, those 18th century shipwrights sure enjoyed playing with fluid shapes; the shipwrights must have groaned when they saw the latest shape to manufacture! Greg, Kevin and Cisco, thanks for your thoughtful comments about the complexities of these constructions. I continue to be amazed when the underlying logic or geometry finally reveals itself, as I struggle to fit all the parts together in three dimensions. I am in awe of the original shipwrights who could visualize and then construct such complex forms. And how the complexity all adds up to something exceedingly beautiful, and simple in its overall visual effect. Hakan, yes, that is a Tormek in the background. I bought it many years ago, struggled to make it work for me, and then put it away. I pulled it back out more recently, to see if I would have better luck now I have had more years of experience with tools. It doesn't help with the small chisels, but some success with the larger ones. Steady progress, but slow going as I work out the intricate geometries of the stern and quarter galleries. I redrew the stern, expanding the geometry in the x and y directions to get a true projection of the sizes and angles. I taped some card to the stern and marked various key points including the important diminishing of the verticals. I then scanned this and put it into CAD, where I could extend the verticals to a common point on the centerline, allowing me then to find the correct angles for the outer edges of the quarter galleries. Here is the flattened drawing: This then allowed me to fabricate the false window walls on the aft side of the quarter galleries, which provides all of the important locations for everything in this area: and then I used spacers to locate the middle railing and top surface of the captain's head. (The horizontal plate one down from the top is a temporary form to help me locate the railing at the base of the windows at this location; it will go away once the railing is in place). I discovered that in this recreation of the original Bellona design of 1760, the captain's space here is pretty tiny. He has about 14" of clearance between his forward door and the curved side of the quarter gallery. It gets a little wider towards the seat at the stern, but even there he has only 2'-9" of clearance. It looks great on the outside, diminishing the entire quarter gallery as it ascends to the top; but the captain could not have been very happy with this. Indeed, in the 1780ish rebuild shown in the second Bellona model, the captain's head is much expanded to match a little closer the size of the officers' head below. Today is the 254th anniversary of Thomas Slade's death, the famous shipwright for the Bellona and Victory. He must have been annoyed when asked to expand the captain's quarter gallery; it looks so much better the way he originally drew it! To help with cutting and shaping these increasingly small and awkward pieces, I bought the Veritas miniature workbench clamping devices. I made up a surface with regular holes, which can attach to the front of my workbench with the GRS mounting plate: Here is the GRS plate holding a Knew Concepts bench pin and saw. I am turning to these increasingly to shape these small parts. This turned out to be such a handy surface for fine work, I added a bench hook for cutting small pieces with the razor saw. It has dowels on the bottom that drop right into the flat surface holes: All for now, Mark

-

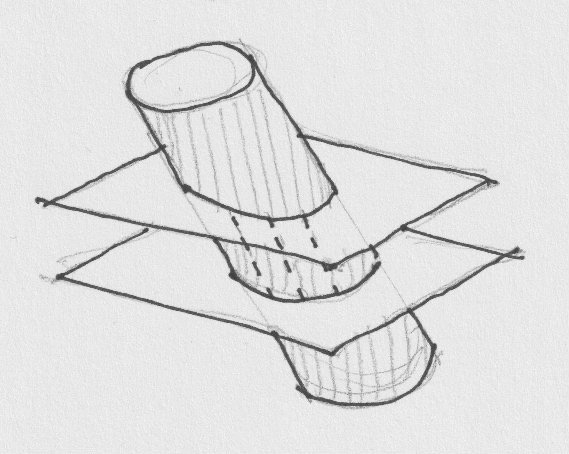

Hi everyone, Thank you, Kevin, for your kind words. It is definitely turning into my life's work after all these years, and many more to go at my current pace. I might as well make it as good as I can! druxey, I agree with your "gazunder" conclusion. Given the geometry of the quarter galleries, the only direct drop from the upper--captain's--seat of ease would discharge directly onto or out of the face of the false window in the quarter gallery below. Not likely. I am sticking with a chamber pot and proceeding accordingly! The stern construction is undoubtedly the most difficult thing I have ever attempted to make. Even planking the upper counter seemed straightforward at first, but the wood is so thin here that I struggled to keep the surface fair while rounding up and aft, and on a curved frame in the vertical direction. I had to redo in order to remove some initial hollow low spots. All is well now, ready for paint. It also strikes me the ridiculous fragility of this entire stern. No wonder captains dreamed of raking their opponents through the stern. Moving to the side lower windows of the quarter gallery, I had read long ago that the upper and lower boundaries of these windows had to be exactly the same radius, held in the same orientation when the top one is offset to the stern. This is to ensure that the vertical mullions between the three windows are parallel to each other in the x and y axis. If they are twisted, the windows would be twisted and could not be paneled with flat sheets of glass. I thought of it as a cylinder sloped back at the angle of the windows across the stern, and then parallel planes aligned with the sheer of the hull cutting through to define the tops and bottoms. Hopefully this diagram makes this clear. The dotted lines are the lines of the window mullions: I arranged this by making panels top and bottom to the same template, then ensuring that the curves coming forward made the same angle with the stern moldings top and bottom: And these resulted in window surfaces that are flat and untwisted. However, the three windows are not geometrically the same, which initially surprised me. Although the length of the sides are the same--since the two planes forming the top and bottom are paralleI--the angles these form with the top and bottom edges of the window are not the same. The sternmost window has a sharper angle, the middle one somehat less but still sharper than the foremost window. I eventually realized that this would have to be. The aft most is most parallel to the side of the sloping cylinder, while the foremost is coming around to the fore face of the cylinder, which is less angled relative to the cutting planes. The sides of a window on the front surface would be at right angles to the tops and bottoms. I also noticed that the changing geometry created an optical illusion. I initially made the three windows the same width fore and aft, then saw that the aft most window looked too skinny relative to the other two. I made a number of paper templates installed in the openings, varying the widths until they "looked" the same width. It turned out that the aft most had to be made wider, then the middle a little less but still wider than the foremost window. Here is the result with the final paper templates: I also discovered the reason for the little scroll work carving at the fore end of the windows, which shows up in every 74 gun ship of this era. It hides the fact that the fore edge of the foremost mullion is not parallel to its aft edge; the upper edge has to be longer than the lower edge in order to fair to the side of the hull. This would have been visually clunky, so they disguised it with a little carving to cover it up. Looking forward, here are paper templates of the upper works: Still a lot to do! Mark

-

Interesting, interesting! Thanks everyone! So here is a first thought about how the pipes would run to a discharge in the lower counter, under the quarter galleries. Some assumptions: 1. The pipe from above has to run down the outer face of the hull--along the inner wall of the lower quarter gallery, in other words--because there is no place to bury the pipe in the hull itself. Presumably there would be a paneled chase to disguise it. 2. Offsetting the seats doesn't appear possible, or helpful. The Bellona admiralty drawing show the lower one centered in the bench. The upper bench is so short that there is not much room to offset. And given number 1 above, there is no advantage gained in an offset a few inches one way or the other since the pipe has to bend inboard to run down the outer face of the hull anyway. 3. The two discharges could be aligned athwartships, with the upper pipe closer to the hull and the lower pipe further out. maybe closely paired like twin exhausts in a sports car! 4. I don't see these both bending sharply forward another three feet--and outward to clear the tumblehome-- in a two foot drop to discharge through the lower finishing. It is just asking for clogs. 4. I have provided a chamber pot for the upper toilet, just in case those long runs of pipe with bends doesn't always do the job!🙄 Mark

-

Thanks so much, Alan and Marc. I don't know if I am slowing down because I am getting older or the work is getting more complicated, or both. But it is a good push to keep going when I am able to share progress. Interesting question about the plumbing arrangements in the quarter galleries in the mid eighteenth century. I have only found Brian Lavery's account in the Arming and Fitting of English Ships of War, pages 202-204. He says that "presumably there was some form of piping...especially from the upper galleries." And he refers to some pipes on models. I have not seen this. Can anyone send me a photo of a model with this piping showing? I am looking at the path piping would have to take, particularly from the upper quarter gallery, and there are some serious bends and long horizontal runs to get to a discharge in the lower finishing. One wonders how this was efficiently flushed out. Lavery notes that a flushing cistern and water closet was first ordered in 1779, 20 years after the Bellona was completed, and even then few ships were fitted with such. Without such a device, it would have been jugs of water poured down, and maybe a long loo brush or sewer snake? The alternative idea, of a chamber pot, would have replicated the same toilet arrangements many of the officers would have experienced in their land based homes at the time, I presume. I also noticed that in the HMS Victory quarter gallery open to public viewing, the hole is in a hinged hatch on the bench, which I interpreted to be the access to the chamber pot beneath. But that is pure speculation on my part. Small point that I probably won't address further in my model, but it is an interesting question about 18th century technology. Any further information on this would be greatly appreciated!

-

It has been a long time since I last posted. This stern structure is undoubtedly the most complex and difficult thing I have ever attempted to build. But I am making progress. I had to use the horizontal moulding between the lower and upper counters, and also between the upper counter and the window sills, as templates for determining the curve and width of the quarter galleries. So these were left unmoulded for a time--and therefore a little stiffer--in order to keep everyone in alignment. Here I am confirming the window layout. the window frames will obviously require some leveling when they are finally installed: And here is a template to see how it is all going to line up: Next, the officer toilets are constructed. Working from a cryptic plan drawing in the original admiralty draughts, and a photo of Victory's quarter gallery, I decided that these were likely just holes in a bench with a chamber pot underneath, retrieved by a hinged top to the bench. Fun work for the officer servants to clean up every day. I wonder where they dumped these overboard--at the head, perhaps? And then the mouldings are given their profile, and glued in place at last! Next to come, planking the upper counter and the veneer of planking on the quarter galleries, druxey's great suggestion. I don't know how I would ever have formed these pieces without carving them from a whole piece. Curves in too many directions!

-

druxey, great idea, planking over the blank rather than scratching in the plank lines. That way, I can get tight joins to the mouldings, and also cope with how the planking on the counter intersects the planking on the quarter gallery. I am thinking that the planking on the quarter galleries runs past the planking on the counter, so the planking ends are seen from the stern and not from the side. that was going to be very hard to do, if I had to rabbet the quarter gallery blanks to receive the ends of the planking on the counter. And thanks, Marc, for reminding me of Siggi's work. There is always much to learn from him. His post was like a road map for me, what is coming next and how to deal with it. It also reminded me that I have some challenging painting to do on the lower counter! Mark

-

Thanks so much, Yves, Scrubby and Mike, for your kind comments. I have not posted in a while, because I was having to work out a few new challenges as I begin to work my way up from the lower finishing. First challenge: how to frame and plank the quarter gallery surface above the lower finishing? This is the blue band between the lower stool rail and the lower gallery rim, below: It curves, twists, and fays to the side of the hull with a shape I could not determine in advance. Also, how would I plank the inner surface once the framing was in place? I remember seeing a model of the Superb, with its stern in pieces. With the quarter gallery lying on its side, it is possible to see that this piece appeared to be cut out of a single block. So I decided to do that. This way, I could fair each edge to a known surface, and thereby discover the actual form. Then I could scribe the planking on the outer surface later. First, I drew the top and bottom profiles as best I could determine from my drawings. I pasted one on top and bottom of a blank, then shaped the outer surface to match each edge. After refining while checking against the actual model, I came up with the shape and how it fit against the hull: Here you can see the wicked twist in the shape. And here you can see it pinned temporarily in place (this is a trial blank I made out of basswood, to quickly see if this would work): Next, I had to work out the shapes of the mouldings on its lower edge, which is the knuckle between the lower and upper counters. It took a long time to realize that the moulding here is the not the same profile along the counter as it is along the side of the quarter gallery. These have to miter cleanly at the corner, but they are very different profiles. Looking carefully at the sections below (cut through the quarter gallery on the left, and through the knuckle of the lower and upper counters on the right), you can see that the face of the quarter gallery is almost vertical, whereas the face of the upper counter slopes back quite substantially. I finally realized that in order for these to miter together, the important thing is the thickness of the moulding in both locations has to be the same at the top and the bottom. Also, the top edge of the moulding on the quarter gallery has to align with the roundup of the moulding along the counter, whereas the top edge of the moulding on the counter has to align with the sheer of the external hull planking. A little geometry worked out the profile for each, so they would fair to their own surfaces while mitering cleanly at the corner. Next challenge: how to cut the profiles with a scraper? All of my earlier mouldings were just straight blanks cut on a flat surface and later gently bent to the sheer of the hull. But these mouldings are on sharply curved surfaces. I decided for reasons of accuracy in the overall construction to shape the blanks of the mouldings to their final curves, rather than making flat mouldings and bending them to the shape later. I saw too many places for things to get out of alignment if I did not make accurate blanks to start with. So how to scrape a shape on a curved blank, which also has top and bottom edges not at right angles to the face of the moulding? I decided to make formers, to which I could temporarily glue the blank, and use the former to guide a fence on my cutter holder. Here you can see the cutter for the moulding on the quarter gallery. The face of the fence is at an angle to the cutter, corresponding to the angle of the top of the moulding. You can see the necessity of the angle, because if the fence were at right angles, the cutter would tear up the shape as it progressively works its way down. Here is the scraper at work: And here is the moulding temporarily spot glued in place, to check its fit and final size. This is also the final faux planked piece, cut out of boxwood after the basswood trial worked: The flat piece faintly labeled STAR BD eventually goes away. This was a temporary former for getting all of the railings in their proper location and shape. The rabbeted rail is the base of the window frames still to come. I have frankly struggled with making scraper profiles, until Chuck suggested I just make them out of brass rather than fussing with tool steel, softening to file and hardening to use. Each profile here is only going to be used for one or two parts, and then can be thrown away. So I worked out profiles based on the two semi-circles, and accurately drilled these in the brass blank on a mill: Then I carefully filed the remainder of the profile using a needle barrette file and a jewelers clamp to ensure right angles to each side. This is important for the cutter to work the same in both directions. At last, I got accurate profiles with no heat treating challenges. Thanks, Chuck! Now on the port side, and the big moulding along the knuckle here. Best wishes, Mark

-

And in just one more day, the port side is painted. Much faster second time through. I got more efficient with the masking: The port side. I am glad I took the time to paint the edges of the planking at the ports with red, giving a very clean junction where they cut into the wale at the stern. And very satisfying to see both black wales from the bow: And now back to the quarter galleries! Mark

-

Hi JD and Mike, I use General Finishes Gel Topcoat, Wipe On Urethane in Satin (cleans up with mineral spirits). It is a rub in, rub off finish. On the raw boxwood, it darkens it up and gives the slightest sheen. You can see it on the exposed futtocks below the wale, compared to the raw wood above the wale. It is a little challenging to apply to all of the ledges and carlings on the exposed deck frames; I haven't quite figured out an efficient way to apply it between the spaces, and then rub off well into the corners. I used Vallejo Model Air acrylic for the black. Thanks, Chuck, for the kind comment. I am trying some Vallejo colors for spraying the plastic window frames to look like boxwood. I'll let you know what works best! Mark

-

Thanks, Greg, for the kind comment on the project. And druxey, thanks for clarifying why the quarter galleries shape to a point at their fore end. While "ensconced", the Captain could keep an eye on the trim of the sails from a different perspective! After a great deal of fussing with airbrush and compressor, I finally got the starboard wale painted. It is currently flat black, but will have a coat of the transparent poly gel over it, the same finish as for the rest of the hull. it will give a little sheen and lighten the color, according to my test pieces. It looks nice with those mean black cannon poking through the ports... Another fun masking process before the paint. I had to turn the hull on its side so I could spray the under edge of the wale, avoiding using an airbrush pointed upwards.... Next, the port wale, and then back to constructing the quarter galleries! Mark

-

The starboard masking for the gunport edges went much faster, only 3 days of masking..... So now I am ready for the black Wales at last. Just one more round of final sanding for the sides (some masking tape ghosts to clean up). As I was preparing to paint this last round of red, my airbrush compressor suddenly stopped pushing air. I looked around for the cause and noticed that the hose connecting the compressor to the filter had completely severed at the fitting pressed onto its end, either rotted away or twist stressed. I did my best to cut a clean edge on the hose and reattach it to the screw fitting, only to discover that there were slow leaks at several other cramped points in the hose. I taped those up, completed the painting, and then the other end of the hose severed from its pressed on fitting. I had to order a new hose, and the black wales will have to wait for delivery. The compressor was probably 15 years old, maybe the shelf life for hoses.... Mark

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.