Bob Cleek

Members-

Posts

3,364 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Bob Cleek

-

Who knows? Perhaps McDonald's or another of the fast-food restaurant chains could buy and restore her to operate burning used deep fat frying oil for fuel! (Don't laugh. I know several guys who are running live steam launches or railroad steam engines on used frying oil, waste restaurant grease, and/or strained used crankcase oil. United States set the Hales Trophy record of three days, ten hours and forty minutes, Southampton to New York. The QE2 is the only transatlantic passenger liner regularly operating at present. Given her top speed, she could cross in about five days, but her scheduled crossings presently take seven days which permits a leisurely crossing with sufficient time to adjust to time zone changes without noticing them, a feature of importance to some passengers. United States could easily cross on a seven-day schedule on a directional rotation schedule in the opposite direction to QE2. It's been a long time since my father worked for decades as an accountant for American President Lines, (and myself as well in summer jobs during high school and college,) which ran premier passenger liners on the Pacific runs, but while the advent of the jet airliner ultimately knocked the slats out of the seaborne passenger trade, I believe most in the industry were rather surprised to watch the recovery and regeneration of passenger service in the form of "cruise liners" which now likely carry far more passengers than the great transoceanic passenger liners did even in their heydays. Just as there was a market for the Concorde supersonic jet, the Orient Express, and now again in the United States, certain luxury passenger railroad trains, it may be economically feasible to restore and operate the United States in luxury passenger service once again. Such passenger service is, of course, not practical as a primary mode of transportation, particularly for business, but where folks might be interested in "getting there being half the fun," it might attract a certain niche clientele that might make it pay. Who might take that gamble is another matter entirely and, as mentioned above, the Jones Act, once designed to protect American merchant marine jobs, in the end has come to eliminate as many as it once was intended to preserve and may preclude the economic feasibility of such a scheme. Moreover, the vessel is probably well-beyond her "use by" date, although I can't say off the top of my head what that regulation may be these days. Due to her age, I highly suspect she'd require some sort of licensing waiver from MARAD to operate as a U.S. flagged vessel in any event. Lastly, of course, is the fact that she is at present, from all reports, entirely stripped of all equipment, furniture, furnishings and the like and is simply a shell that would have to be entirely rebuilt to present-day standards. So, no. The dream may be a pleasant one, but I really doubt it could pencil out. If it could, somebody would have done so. In the end, there is really nothing quite so expensive, even to do nothing with. as a large vessel built to sail the seas. A ship that isn't working is a ship that is losing her owners money and that fact often warrants getting rid of them as quickly as possible once they are no longer profitable.

-

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

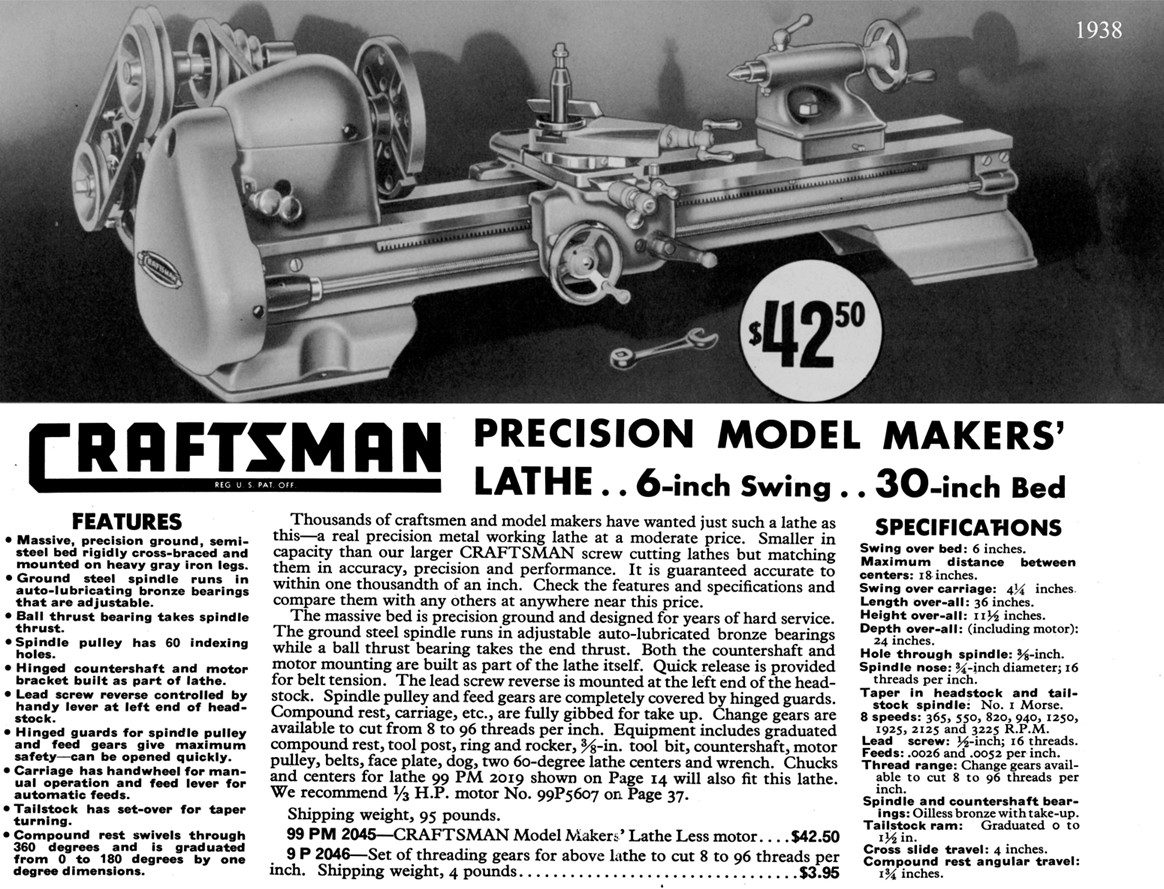

See: Atlas 6-inch Lathe (lathes.co.uk) : "Styled to closely resemble its larger brother, the "10-inch", the Atlas 'Model 618' 6" x 18" (3.5" centre height) backgeared and screwcutting lathe was in production from 1936 until 1974 and then, in Mk. 2 form, until 1980. Enormously popular in America - it was affordable and with a specification that allowed it to undertake the majority of jobs likely to be encountered in a home workshop - its likely that the lathe made its first appearance not as an Atlas but badged for the mail-order company Sears, Roebuck under their Craftsman identification tab as the 101.07300. This initial Craftsman model, which carried an inadequate 3/4" x 16 t.p.i. spindle thread, a headstock that lacked backgearing and a countershaft unit and belt-tensioning arrangements of a very elementary, lightweight design, was sold at the very competitive price of $42. However, it was made for one year only before being replaced by the much better specified 101.07301--as listed in the post 1938 catalogs shown here : Craftsman 6-inch Lathe Catalog Extracts (lathes.co.uk) Note advertisement text in left-hand column: "Ground steel spindle runs in auto-lubricating bronze bearings that are adjustable." That may simply be a belt issue. I've heard several reports of surprisingly smoother and quieter running of the very similar Atlas/Craftsman 12" lathes when old standard drive belts were replaced with correctly-sized new Accu-link adjustable link "V" belts or the equivalent. The Accu-link belts are a boon for lathe owners because they permit belt changes without the need to disassemble the headstock and back-gearing assemblies to get a non-opening belt around the belt wheels. There's no problem at all turning wood on a metal lathe other than the need to keep the lathe clean. Wood chips and shavings and sawdust easily finds its was into motor armatures and gearing, quickly absorbs oil, and creates a nasty gunk that isn't particularly healthy for high-tolerance machine tools. Sheilding from sawdust and careful vacuuming up after wood working is required for proper maintenance. That said, if one has any great amount of wood turning to do, it's probably easier to buy a wood lathe, which are relatively inexpensive, especially on the used market, than to keep a machinist's lathe clean if it's being regularly used to turn wood. -

Another tip for you and anybody else who hasn't discovered it as yet: There is a wealth of fine detail brushes available at a fraction of the cost charged by modeling and artists' supply stores, in fact, at almost "disposable brush" prices, to be found listed for sale to manicurists. It seems there's a lot of fine detail painting now fashionable in the manicure business. Check out the manicurists' "nail art" sites for ultra-fine brushes of all types, particularly lining brushes. See: Amazon.com : nail art brushes and Nail Art Brushes for sale | eBay For example: Nail Art Brushes Nail Liner Brush Liner for Nails Easy Hold Thin Nail Art Design | eBay, $7.91 w/ free shipping:

-

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Indeed it is! I should have looked more closely at the photos. They appear quite a bit alike. The 6" is a sweet small modeling lathe, but they don't seem as available on the used market as the 12"-ers. -

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

And still are available on eBay or from after-market manufacturers... for a price. Check out "Mr Pete 222" or "Tubal Cain" (same guy) on YouTube. He's a retired shop teacher with great instructional videos on the Atlas/Craftsman 12' lathes. Everything you even wanted to know. I believe you can look up the age of yours with the serial number on lathes.co.uk under the Craftsman entries. There were a number of refinements over the several decades that this lathe was manufactured. There are many of them floating around and so parts are readily available. They are somewhat of a cult thing now. They aren't state of the art anymore with CNC and DRO features, but they'll do anything you could possibly need to do (including milling with the milling attachment) on a medium to light duty 12" manual lathe. If you have one that hasn't been "destroyed" along the way by misuse, they are certainly worth restoring. They're worth money even if they are trashed because of the continuing market demand for parts. (Threading gear sets are still available if you are missing any. Be careful not to "crash" the gears and damage the gear teeth. The gears are made of Zamac, a relatively weak alloy and it's not difficult to break teeth if you don't know what you are doing operating the lathe. Not to scare you off, but lathes are not a machine you ever want to learn how to use by just "fiddling" with them and they can be very dangerous in the hands of an untrained operator. All the operating manuals for these lathes are available for free online. Google them up. I love mine. I picked it up along with just about every possible attachment (except a taper jig, darn it... but those are still made by an aftermarket manufacturer) from a retired old school machinist's widow for a very reasonable price. -

That's an excellent explanation of how to make a Ballentine coil. There are a number of ways to coil falls for the same purpose as a Ballentine coil. Other's make use of "figure-eight" faking, and so on. The original question, if I understand it correctly, addressed a "Flemished" line coil where the line lays in a tight flat coil on the deck without any overlapping turns.

-

Yes, you have stated it correctly. I got it bass-ackwards. Sometimes it's a lot easier to do something relying on "muscle memory," than it is to write an instruction on how to do it! The photo above is indeed correct. What I should have said was that the coil begins with the bitter end in the center and is rotated until the line is fully coiled with the working end of the line running off of the outside of the coil. Obviously. it one tried to rotate the coil on the flat of the deck with the working (belayed) end in the center, the line would twist up between the center of the coil and the belaying point and get all kinky! Thanks for spotting the error! BOB

-

Or a lot of razor blades, as the saying goes!

-

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

It's just a short drive from Mystic Seaport in the town of New Bedford a couple of blocks from the waterfront. It's not in a real "touristy" area, or wasn't when I was last there years ago. New Bedford is, or was, still a working waterfront back then. If whaling is your thing and you're in the area, take the ferry from Hyannis to Nantucket and check out the whaling museum there. It's a very good one as well. -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Hard to say the date on the New Bedford Flags poster. I tried to enlarge it, but I couldn't get a legible look at the date, if any. It's from a Pinterest post that credits it to the New Bedford Whaling Museum's collection. (Home - New Bedford Whaling Museum) You could probably call them and ask. You might get lucky and connect with somebody who could check for you. The "poster" does contain the identity of the printer, although I can read it, and it probably has a copyright date on it somewhere. It looks to have been a printer's advertising "give-away." The New Bedford Whaling Museum isn't a large museum and so staff may be accessible by phone or email, unlike much larger institutions. It's a great museum nonetheless and definitely worth a visit. (Also the home of the largest whaling ship model in the world, Lagoda at 1:2 scale. Lagoda - Wikipedia ) -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Happy to oblige, Allan! If it weren't for opportunities to share this trivia, I'd have no excuse for storing all of it in my cranial hard drive! -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Pennants used to identify individual vessels, be they naval, merchant, or pleasure craft, were commonly carried prior to the wider use of code signals (flags) to indicate the code (usually "five level" - five letters and or numbers) assigned to the vessel by navies, marine insurance companies, and national documentation agencies. Pennants were rarely opaque with lettering on both sides. Actually, in practice, it was much easier at a distance to identify a signal that wasn't opaque because the sun would shine both on it or behind and through it. If a pennant or signal were opaque, its "shaded side" would appear black at a distance. Additionally, there are advantages to a pennant or signal being made of light cloth which will readily "fly," in light air. In fact, when a square-rigged vessel is running downwind, her signals, ensigns, and pennants on the ship moving at close to the speed of the wind itself, would cause the signals, pennants, and ensigns to "hang limp" and be difficult to see at any distance. Even today, when racing sailboats routinely show "sail numbers" on their sails to identify themselves, the numbers must appear reversed on the "back side" and no attempt is made to overcome this. The international racing rules require that sail number and class logo, if appropriate, must be shown on both sides of the mainsail in that case each side of the sail will have the number shown "in the right direction." There are very specific universal regulations for the placement of sail numbers on racing yachts which specifically dictate how the obverse and reverse lettering must be applied to a vessel's sails. (See: TRRS | Identification on sails (racingrulesofsailing.org) Today, adhesive-backed numbers and letters are applied to synthetic fabric sails. In earlier times, the letters and numbers were cut out and appliqued to the sail. In earlier times, several systems, other than identification code signals, were in common use and these are what we commonly see on contemporary paintings. The two primary signals used were a large flag or pennant with the vessel's name on it, or the owner's name, or company name, on it, or a logo of some sort. The latter were usually called "house flags" which designated the identity of the owner of the vessel. When steam power came on the scene, these owner's "house flags" were supplemented by painting the funnels of the steam ships with the colors and logos of the owners' house flags as well. House flag chart from the 1930's or so: The house flags and ship name pennants we see in the contemporary paintings serve to identify the vessel in the painting, but in order to fully appreciate the purpose of "naming pennants" and house flags, it has to be understood that until radio communications came into being (first Marconi transmission at sea by RMS Lucania in 1901 and first continuous radio communication with land during an Atlantic crossing ... RMS Lucania in 1903.) there was no way for a ship owner to know much of anything about their vessel until it returned home which, in the case of whaling vessels could be two or three years. Shipping companies, marine insurers, and maritime shipping companies, among others, had a desperate need for news about their ships, but they could only know the fate of their ships, crew, and cargo (though not necessarily in that order!) when the ship showed up. Ships at sea would hail each other when they ran into one another at sea: "What ship? What port?" and sometimes get word back to owners that their ship was seen, on the Pacific whaling grounds, for instance, months or even years earlier, but there was no way to know what was going on with a ship until she returned to her home port. Businesses ashore were desperate to know the fate of ships and shipments and being the first to learn of a particular ship's arrival in port gave a businessman a particular advantage in making investments, commodities trades, purchases, and sales. This was especially true in the United States before the construction of the transcontinental telegraph system owing to the immense size of the nation "from sea to shining sea." For example, in San Francisco, which was for a time shortly after the discovery of gold, isolated from communications with the East Coast, things as simple as newspapers would arrive only by ship and when they did, the race was on to get in line to read the "news of the world." An organization called the "Merchants' Exchange" was created to operate a semaphore telegraph system from Point Lobos at the farthest west point of the San Francisco Península to what came to be called "Telegraph Hill" to communicate the identity of ships arriving off the Golden Gate often many hours before they actually docked and to make East Coast newspapers and other information sources available to local subscribers. On the East Coast, seaport homes had their famous "widows' walks" where the ship captain's wives would look for their husband's ship in the offing to know whether he'd ever return, and they'd know by the house flag which ship was which. Yes. That's a good description of the device used to set pennants and house flags "flying." The device is called a "pig stick" as it is a short stick similar to what a pig farmer would use to herd his pigs. A pig stick has a wire or wooden "auxiliary stick" from which the flag or pennant is flown independent of the main stick. This device, pictured below, prevents the signal or pennant from wrapping around the "pig stick" and fouling on the pole or otherwise becoming unreadable. The middle two paintings of ships posted above show those two ships simultaneously flying a "name pennant" from the maintop, a "house flag" from the foremast top, and a "five level code" (likely assigned by Lloyds Insurers.) identifying the vessel in a commonly redundant fashion at that time. -

alcoholic stain on blocks

Bob Cleek replied to Frank Burroughs's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Well, that would depend upon whether you wanted to color them differently from the natural color of whatever you made them from, no? The color of blocks will depend largely upon the period of the ship one is modeling. Some blocks were oiled bare wood. Later, blocks were painted, usually white or black. -

Interesting. I've never heard the term "cheesing" used before. I presume this is a reference to a "wheel" of cheese. It's also called "Flemishing" or a "Flemish coil." I suppose this was a reference to where it was commonly done. Banyan gave a number of good reasons against flemishing line on deck. There's more. Long exposure to weather and UV will cause uneven deterioration on the surface of the line is another one. A properly Flemished coil will run fair, however. This requires that the working end of the line is pulled from the center of the coil. The "bitter end" should always end on the outside of the "coil" (pad) and not in the center. The way a Flemish coil is created in real life is that the coil begins in the center and the entire (growing) coil is turned round and round on the deck while lying flat until the bitter end is reached. As Banyan said, it was only done for display purposes at formal inspections, but was never done in ordinary use.

-

Use canned clear shellac (about a 2 pound cut - Zinsser Bullseye brand or equivalent) to cause the line to stiffen. Shellac is dissolved in alcohol. As the alcohol evaporates, the shellac soaked into the line will begin to harden and the line can be formed into any shape. Once the shellac has dried (within minutes) the line will be stiff and hold whatever shape you have given it. If more working time is needed, simply apply additional alcohol and the shellac will soften again. Results example below. Coils made on a form consisting of map pins placed into a wooden base around which the coils were wound. Coils were installed on the model, softened with alcohol, and formed in place to depict normal hanging behavior of full-size line.

-

QuadHands are "finestkind." You'll love them. Nobody should waste their money on those near useless ball-jointed "helping hands" that you have to adjust by tightening wing-nuts. They are really junk. (And, like so many others years ago, I bought one, too! ) One thing to be careful about, though, is to make sure you buy the real QuadHands fixtures. There are "carbon copy" Chinese knockoffs all over the internet, but they aren't the same quality at all. The QuadHands uses high quality alligator clips for one thing. Cheap alligator clips are a dime a dozen, and they don't hold well at all. Don't subsidize intellectual property theft. Buy the real McCoy!

-

Sorry about that. I got interrupted writing the above post. In the meantime, it looks like you "pulled the pin" and ordered a vise from Micro-Mark when you could have ordered it from Walmart for ten bucks less. I won't rub it in, but only to say that it always pays to shop around before buying anything from Micro-Mark.

-

An excellent tool that everybody should have. However, you should shop around on the internet to find the lowest price. As usual, Micro=Mark has more tools for modeling than most any catalog, but nearly always at a considerably higher price. For example, see: Universal Work Holder Peg Clamp Jewelers Engraving Hand Tool for Jewelry Making - Walmart.com This tool has a handle that can be screwed off and the base neck is hexagonally shaped so it can be placed in a bench vise. That's often a more convenient way to use it than holding it in one hand and some tool or paintbrush in the other. Fancy articulated bench top holders are made for it, or sold with this vise, but all are of questionable utility (often too weak) and overpriced. The best option is to buy a decent small 2.5" or 3" bench vise with a clamping attachment for $30 or less. E.g.; $23.50 Clamp-On Swivel Vise - Lee Valley Tools Another option that is very handy to have is one of the extremely versatile QuadHands holding platforms. These are heavy iron plates with flexible arms holding heavy duty alligator clips that attach to the base plate with rare earth magnets. Sold on Amazon and elsewhere. They are really useful for lots of applications, particularly holding parts for painting, gluing, and soldering. This is a commercial grade tool made for and marketed to the electronics assembly industry. Beware of identical-appearing Chinese knock-offs. The quality is not the same. "QuadHands" is the brand you want. See: QuadHands® - Helping Hands Tool They come in several sizes and additional "arms" and attachments are available, starting at around $40. Also sold on Amazon.

-

You might want to reconsider the above. In practice, it appears that reef points on any given sail would all be of the same length in any event. The "rule of thumb" from Falconer's above sounds right, but here again the maxim, "Different ships, different long splices." applies. The reef points need to be long enough to conveniently encircle the mass of gathered canvas in the sail to be secured. Therefore, the size of the sail is the determining factor. In different periods, the common square sail sizes varied. In later times, particularly with merchant vessels, the size of the sails was reduced to permit easier handling and, thus, smaller crews, which meant more profit in the operation of the vessel. Obviously, a longer square sail will require longer reef points than a sail that's half as long. Naval vessels would furl sails very tightly such that the sail gathered and tied on the spar would not exceed the diameter of the spar. On the other hand, a merchant vessel would characteristically be less fastidiously maintained, and sails might be furled less tightly, if not just making a sloppy job of it sufficient only to get the canvas under control and out of the way and so might have longer reef points. Not to make you crazy or anything, but depending upon the scale you're working in and the level of detail you are depicting, note also that reef "points" were so called because they were "pointed" by working a taper into their ends. There were general standards for the length of the reef points. (Note the term "reef points" references the pointed shape of these lines. It does not have anything to do with the gromets worked into the sail through which reef points are passed, as is modernly a commonly heard misuse of the term.) A bit of research in the appropriate sources for the period of your model will answer your questions much more specifically. For example, see "Steele's" for both the Admiralty and merchant marine practice circa 1794: https://maritime.org/doc/steel/large/pg148.php There you will also see the number of gaskets that are required for each rate of ship (by the number of guns) to tie the completely furled sail to the yard. Illustrations are also provided. For example, excerpts from Steele's: GASKETS. Braided cordage used to confine the sail to the yard, when furled, &c. ARM-GASKETS; those gaskets used at the extremities of yards. BUNT-GASKETS are those used in the middle of yards. QUARTER-GASKETS; those used between the middle and extremities of the yards. GASKETS are made with three-yarn foxes. Those for large ships consist of nine foxes, and those for smaller of seven. Place four foxes together, but lay them of unequal lengths; mark the middle of the whole length, and plait four foxes together, for eight or nine inches; then double it and plait the eight parts together for five inches, and work in the odd fox. The whole is then plaited together for eighteen inches in length; then leave out one fox, and so keep lessening, one fox at a time, till you come to five. If the foxes work out too fast, others must supply their places, till the whole length is worked, which is from five to seven fathoms long. To secure the ends, make a bight, by turning upwards one of the foxes, and plait the others through the bight, then haul tight upon that laid up. (Obviously, few modelers will actually plait their reef points as described by Steele, but an understanding of the full-scale practice better enables the modeler to depict such detail as they may wish secure in the knowledge of what it's supposed to look like.) POINTS, short pieces of braided cordage, plaited together as gaskets are; beginning in the middle with nine foxes, and tapering to five at the ends, and from one fathom and a half to one fathom in length. They are used to reef the courses and topsails. ROPEBANDS differ from gaskets only in their length, being from seven to nine feet long. POINTING. Tapering the end of a rope, or splice, and working over the reduced part a small close netting, with an even number of knittles twisted from the same, to prevent the end untwisting, and to go more easily through a block or hole. REEF. That portion of a sail contained between the head or foot, and a row of eyelet-holes parallel thereto, which portion is taken up to reduce the surface of the sail when the wind increases. Sails, according to their sizes, have from one to four reefs. A BAG-REEF is the fourth, or lower, reef of a topsail. A BALANCE-REEF crosses boom-mainsails diagonally, from the nock to the end of the upper reef-band on the after-leech. When modeling, the best approach is to experiment with a sample of the sail material you'll be using and simply measure how much line it takes to tie the reef lines and let that be your guide for the length of reef lines and gaskets. Many will reduce the model's sail size in order to more easily depict a tightly secured sail on the spar, in which case a similarly sized sail sample will yield the proper length of reef line or gasket needed.

-

Bending hard brass.

Bob Cleek replied to navarcus's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

Probably. For a good example of brass skeg fabrication see: -

Bending hard brass.

Bob Cleek replied to navarcus's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

It's not about the type of vessel or style of hull. He has as 10" x 1/2" x 1/8" piece of "hard" brass to use as a skeg which he wants to bend in order to make it "3/4" lower at the middle to clear the prop." If the stock is to be a skeg, given it's dimensions, I'd expect he wants to know how to bend it 3/4" across the 1/2" wide vertical face of the skeg. "Hard" brass can easily be annealed with a torch, but there are limits to "bending across the flat" which would seemingly be exceeded in this scenario. -

Bending hard brass.

Bob Cleek replied to navarcus's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

I'm sorry. Maybe it's me, but I can't figure out the bend you are contemplating. A picture is worth a thousand words sometimes. I'm not sure how you want to bend it. If you're trying to do what I think you are trying to do, I'd have to answer "No can do." -

It's nice to hear of another who remembers Ray Aker, a man who certainly deserved greater fame than he realized during his lifetime. He was a very good maritime historian and one of the better draftsmen around. I still have the copy of his beautiful technical drawing of the remains of the 1840 whaling bark Lydia uncovered during excavations for the 1978 construction of the San Francisco Peripheral Sewer project which he gave us when I knew the archaeological impact report consultants on that project. http://library.mysticseaport.org/ere/odetail.cfm?id_number=1961.72 Without passing any judgment pro or con regarding your posting your research records on the Drake Navigator's Guild's website, as a fellow member of our generation, I would urge you to strongly consider making provision for the donation of your research files to the J. Porter Shaw Library at the San Francisco National Maritime Museum at Fort Mason, San Francisco. As you probably know, the J. Porter Shaw is the best recognized repository for such subject matter these days.

-

Sorry for the confusion. I was in the middle of an edit, so you caught only the beginning of the post. Check out the link I provided above to the U.S. Amazon and eBay websites and you'll see they are both offering new and used copies. Beyond that, I expect the cost of shipping is prohibitive. We keep hearing that in recent times on all sorts of modeling essentials. The cost of an item on the opposite side of the Pond seems to almost double when the shipping is added. We have U.K. books listed on U.S. eBay, so I'm not sure why it doesn't work the same the other way around. Is it possible the "not available" status is a result of some sort of E.U. customs issue?

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.