-

Posts

455 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Posts posted by molasses

-

-

An illustration from The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor by Darcy Lever shows the futtock stave on the inside of shrouds as logic suggests.

The book is an excellent source for answers to almost any rigging question with abundant, clear illustrations. Available as a paperback book from the usual internet sources for about $15.

-

I am kind of puzzled on Aubrey's ship the Polycrest can anyone shed some light on what it might have looked like?

Polychrest is very similar to the two Dart-class sloops, Dart and Arrow. More information here:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Polychrest

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Arrow_(1796)

Here's an oil painting by Francis Sartorius, dated 1805, of Arrow and Acheron in action against the French frigates Hortense and Incorruptible, 4 February 1805, from the NMM collection.

And a close-up of Arrow.

NMM also has the original plans for Arrow and Dart: http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections.html#!csearch;authority=subject-90660;collectionReference=subject-90660;innerSearchTerm=arrow+1796

-

You are correct, David. You made this one look easy.

Columbus was built in 1824 in Quebec. Her dimensions were 301 ft x 50 ft 6ins x 22 ft 5 in, 3690 tons. She was flat-bottomed, with straight sides and made of timbers as nearly square as possible with the intention of carrying a cargo of timber over the Atlantic and then herself being taken apart and sold as part of it. On 5 September she sailed with 6300 tons of timber for London and arrived in the Downs in a leaking condition. With the help of pilots and steam tugs she was brought as far as Blackwall Reach for unloading but her owners did not dismantle her as planned. They sent her back for another cargo but she wrecked outward-bound in the English Channel on 17 May 1825. She had the nickname "The American Raft."

-

NMBROCK:

Your photo is of the Coronation model, not a generic 90-gun second rate of 1675. I looked up the Kriegstein Collection and found more photos of her. The two models are almost identical except for the figurehead and quarter and stern gallery decoration. Please excuse my error.

Here's the next "Name the Ship". Other than cropping out the name and details, the image is not retouched.

Good luck, you'll need it.

-

Coronation 1685, 90 guns, sank in 1691. Wreck found in 1967 and now a protected wreck site.

The model is in the NMM, Greenwich. Here's the description:

"Scale: 1:48. A contemporary full hull model of a 90-gun three-decker (circa 1675), built plank on frame in the Navy Board style. The model is partially decked, equipped and rigged. The model is probably a preliminary design for the 90-gun second-rates of the 1677 'thirty ships’ building programme, and has a gun deck length of 158 feet by 42 feet in the beam and a burden tonnage of approximately 1200. It was restored and re-rigged in 1929, with the lower masts and fighting tops thought to be original. The model illustrates very well the amount of carved decoration these ships carried for this period, in particular the wreathed gunports, a feature that was discontinued in the early 18th century on the grounds of cost."

The NMM photo of the model was used in several articles about Coronation but the model is not of a specific ship.

Here's larger photos from NMM:

There are several more photos of this spectacular model, restored in 1929. This model is not on display.

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/65964.html

Dave

-

Frolick: That bit of information came from the Wikipedia article "HMS Avon (1805)". The article referenced Burke, Edmund (1849) The Annual register of world events: a review of the year. (London: Longmans, Green), Volume 90.

-

Thank you for contributing, Michael. The National Maritime Museum [online] is a wonderful source for plans and information. The ship histories have been particularly useful to me.

I wasn't aware that the four 18-gun Favourite class ship-sloops were a stretch (9 feet deck length and 3 inches beam) of the Cruizer/Snake, thank you.

Just a couple days ago, I came to the same conclusion that the Cruizer class, not the Cherokee class, was the largest class of sailing warships ever built when the actual number launched is considered, not just the number ordered.*

Of the 115 vessels ordered to the Cherokee brig-sloop plan, 11 were cancelled and 2 were not built (Forester and Griffin) but were re-ordered and built at another shipyard (but still listed a second time), for a total of 102 built.

Of the 112 vessels ordered to the Cruizer plans, 3 were cancelled and 4 were in the Snake sub-class (Snake and Victor in 1797-1798 and Childers and Cruiser [with an 's'] in 1827-1828), for a total of 105 Cruizer class brig-sloops built.

It is logical to include the Snake class with the Cruizer class because the hull plans were identical with only a variation in the number of masts. At least 4 Cruizers were altered to a ship rig and one Snake reduced to two masts. If considered as one class, the Cruizer/Snake sloops number 109 built.

It seems clear that more Cruizer class brig-sloops than Cherokee class brig-sloops were built and entered Royal Navy service.

*The assertion that the Cherokee class was the largest class of sailing warship ever built was attributed to J. J. Colledge (1969) & Ben Warlow (rev. ed. 2006) in Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy in the Wikipedia article "Cruizer-class brig-sloops". My analysis of the numbers of vessels built was based on this article, "Cherokee-class brig-sloops" and "List of corvette and sloop classes of the Royal Navy" from Wikipedia with slight corrections made after a little further research, primarily the addition of the Snake class ship-sloops of 1827-28.

David

-

Correct, David. The ship Drumcliff was built in 1887 then sold to a German company, re-rigged as a barque and renamed Omega in 1898. She was seized by Peru in 1917 and held for war reparations then served briefly for sail training in the Peruvian navy. In 1926 she was sold to a guano processing company where she carried guano from the islands to the mainland. In 1953, Omega, with two three masted barques, were the last three square rigged ships hauling cargo - guano. In 1957, she was the last one. She sank in 1958 carrying a full load of bird shi . . er, guano. I thought Omega's name was accidentally very appropriate.

-

-

AJ Fuller

-

Well done, David

Well done, David

This Frolic, launched in 1842, was the only example of her class. Served primarily on slaver suppression where she was very successful.

-

Not Diana or Daring.

-

-

Eye of the Wind. A movie star of sailing ships with appearances in five movies.

-

Cruizers, part 8: HMS Penguin

The Cruizer-class brig-sloop HMS Penguin launched on 29 June 1813 and commissioned in November under Commander Thomas R. Toker, replaced the following month by Commander George A. Byron. In June 1814, command of Penguin transferred to James Dickinson.

HMS Penguin’s Specifications

Length: 100 ft 5 in (gundeck), 77 ft 6 1/2 in (keel)

Beam: 30 ft 7 1/2 in

Tonnage: 387 (bm)

Rig: brig-rigged sloop

Armament: 16 x 32 pounder carronades + 2 x 6 pounder chase guns + 1 x 12 pounder boat gun on the forward platform

Complement: 120 (+12 marines on the day of the battle with Hornet)

On 1 September 1814 Penguin left Portsmouth as escort for a convoy headed for the East Indies and the South Pacific but apparently returned the same day to escort a different convoy the next day headed for Brazil and the Cape of Good Hope where Penguin was to join the South Africa squadron.

At the South African station, the admiral loaned 12 additional marines to supplement Penguin’s crew on a mission to capture or destroy the large American privateer Young Wasp which had been ravaging British shipping in the vicinity.

Penguin arrived near Tristan da Cunha on 23 March 1815. Tristan da Cunha is about 1800 miles west of South Africa and the Cape of Good Hope and about 2100 miles from South America.

The American sloop-of-war Hornet, after sinking Peacock on 24 February 1813, sailed north to New London, Connecticut. Master Commandant James Biddle (the former first lieutenant on Wasp when she captured the Frolic) took command of Hornet after James Lawrence’s promotion and assignment to Chesapeake. Hornet was assigned to the blockaded squadron in New London commanded by Commodore Stephen Decatur of USS United States and Captain Jacob Jones (Biddle’s commanding officer on Wasp) of USS Macedonian.

While blockaded in New London in June 1813, these officers ventured out to pay their respects to the officer in command of the British blockading squadron – Commodore Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy. Hardy had been Admiral Nelson’s flag captain on Victory and his close friend. Near the end of the battle at Trafalgar, Hardy went below to inform the mortally wounded Nelson of his victory and held Nelson in his arms as Nelson died. The American officers admired Horatio Nelson as much as the British admired him, and here was a living legend just a few miles off shore. Biddle and Jones recognized one of the ships in the squadron – HMS Peacock, the ex-Wasp renamed for the Peacock sunk in 15 minutes by Hornet earlier that year and Hornet’s sister ship. During his meeting with Hardy, Biddle asked his permission to challenge HMS Peacock to a ship-to-ship duel. Hardy, knowing quite well the records of the former Wasp and the challenging Hornet, declined. Hardy soon after this meeting with the captain and first officer of the ex-Wasp sent HMS Peacock away southward – no doubt to avoid the public relations nightmare if Hornet should win such a duel and possibly to save face. HMS Peacock foundered with all hands in a storm off the Virginia Capes on 23 July 1814.

Hornet broke out of the blockade of New London on 14 November 1814, sailed to New York to join Commodore Stephen Decatur’s new squadron of the frigate President, ship-sloop Peacock, stores brig Tom Bowline and hired stores brig Macedonian, taking a prize en route.

On 14 January 1815, President and Macedonian tried to break through the blockade heading for the South Atlantic to raid British shipping and rendezvous with the rest of the squadron at Tristan da Cunha and on to the East Indies. President engaged HMS Endymion (40) and surrendered, damaged and unable to escape, as the rest of the blockading squadron closed in on her. The stores brig Macedonian evaded the blockade during the chase. The loss of President was not known in New York when Peacock, Hornet and Tom Bowline slipped past the blockading squadron without incident on 22 January. Soon after breaking out, Hornet separated from the other two, captured two prizes and sent them back to the states with prize crews, reducing Hornet’s crew by eight.

USS Hornet’s Specifications

Length: 106 ft 9 in

Beam: 31 ft 5 inches

Tonnage: 440 (burthen)

Rig: ship-rigged sloop

Armament: 18 x 32 pounder carronades + 2 x 12 pounder chase guns

Complement: 150 (133 at the time of the battle - eight out as prize crews, nine more incapacitated on the sick list)

Beginning in August 1814, representatives from the United States and Great Britain met in Ghent, Kingdom of the Netherlands (now in Belgium) to negotiate an end to the war. The negotiators signed the Treaty of Ghent on 24 December 1814 ending the war pending ratification by both belligerents, which occurred on 30 December by Parliament and on 16 February 1815 by Congress. It took several weeks or months for news of the end of the war to reach all the far-flung forces around the world. The treaty returned all captured territories to their original countries (except a small portion of the future state of Florida captured from Spain which was a nominal, but non-participating, British ally). The treaty also set the border between Canada and the US that had not been clearly defined after the United States had won its independence some thirty years earlier. A significant part of the Treaty of Ghent was the agreement that the United States and Great Britain were to work cooperatively to end the international slave trade – the first two countries in the world to work actively towards that goal. This cooperative effort by the navies of these two nations over the next forty years helped to heal the wounds of two wars and started them on the voyage towards the friendship that exists today between them.

Peacock and Tom Bowline arrived at Tristan da Cunha on 18 or 20 March 1815 but a gale drove them from the rendezvous.

Hornet arrived on the morning of 23 March with a fresh wind from the south-southwest and prepared to anchor off the north point of the island when the lookouts noticed a sail to the southeast steering west at 10:30. Master Commandant James Biddle immediately ordered the pursuit of the unknown sail.

At almost the same moment Penguin’s lookouts spotted Hornet and Commander James Dickinson changed course to engage her. Hornet then hove to, waiting for Penguin to close.

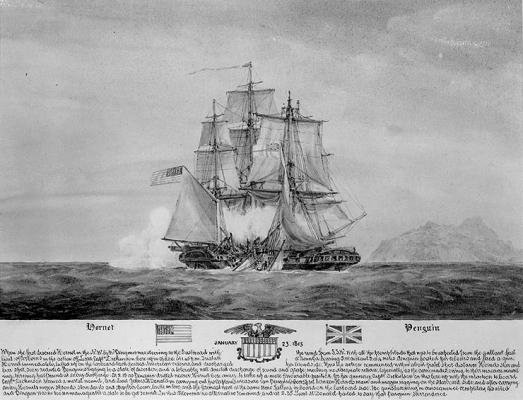

At 1:40 pm Penguin, at about 100 yards from Hornet, turned onto the starboard tack, hoisted her colors and fired a gun. Hornet luffed up on the same tack, hoisted her colors and the engagement began with broadsides from both sloops. The two vessels ran along for about fifteen minutes, gradually coming closer together when Dickinson turned to run aboard his American adversary. At this same moment, he received a mortal wound and command of Penguin fell to his lieutenant, James McDonald, who carried out his commander’s intention.

USS Hornet and HMS Penguin - 23 March 1815

National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Notice that the date is incorrect on this lithograph.

At 1:56, Penguin collided with Hornet with her bowsprit over the Hornet’s deck between her main and mizzen masts on the starboard side. The American seamen were at their posts to repel boarders, but the British did not attempt to board. American cutlass men climbed the rigging to board Penguin but the very calm Biddle stopped them, “it being evident from the beginning that our fire was greatly superior both in quickness and effect.”

With the fresh wind and heavy seas, Hornet forged ahead causing Penguin’s bowsprit to carry away her starboard mizzen shrouds, stern davits and spanker boom, leaving the brig hanging off Hornet’s starboard quarter where only small arms could be used by either side. Biddle then heard what he believed was Penguin’s surrender, ordered his marines to cease firing and leapt onto the taffrail to inquire if she had surrendered. At that moment two marines on Penguin fired at him inflicting a bloody, but not life threatening, wound to his neck. US marines immediately shot them down and Hornet surged ahead breaking off the brig’s bowsprit and taking down the damaged foremast.Hornet wore around to bring a fresh broadside to bear and pour in a raking fire when twenty men appeared at Penguin’s side and on her forecastle with their hands raised and calling out that they had struck. Captain Biddle and his officers found it very difficult to restrain the crew from firing a broadside in retaliation for the manner in which Biddle received his wound. The surrender occurred at 2:02, just 22 minutes after the opening broadsides.

Penguin suffered casualties of 18 dead or mortally wounded, including Commander Dickinson, and 24 wounded. Her hull was riddled with shot holes, she had lost her bowsprit and foremast in the engagement and her mainmast was severely damaged.

Hornet suffered 1 dead and 10 wounded, including her captain and first officer, Lieutenant David Conner, most from small arms fire. Mr. Connor was at first listed as mortally wounded due to the severity of his wound but he eventually recovered. Hornet suffered no damage from cannon fire in her hull, masts or spars although her sails and rigging were considerably shot up. The damage was quickly repaired after the action. The worst damage to Hornet came from Penguin’s bowsprit after the vessels collided.

A comparison between the specifications of Penguin and Hornet show that the two vessels were a very close match with Hornet holding a one gun advantage in their broadsides and parity in number of crewmen and tonnage of the vessels. The tonnage shown in the specifications is as listed in the respective navy records; the difference in those figures is the result of different formulas used by the two navies. When calculated by Roosevelt using the same formula, the disparity in tonnage was less than 3% with the advantage to Hornet.

William James, in his Naval Occurrences and in his six volume work The Naval History of Great Britain, goes to greater lengths than usual to diminish the apparent superiority of the American crew’s gunnery. As he has done in the previous engagements against American vessels, he excludes the ship’s boys in the number of crew on the British ship, a distinction he does not make when the opponent is not American. In this battle, he mentions the twelve marines loaned to Penguin but then forgets to include them in his crew count of 104. He also claims that only twelve of the crew, excluding officers, had previous nautical experience without citing any corroboration. Fifteen months had passed between Penguin’s commissioning and setting sail on her first voyage; it is possible that her three captains in this period had difficulty with finding crews, which might explain the replacement of the first two captains, but Dickinson had more than six months at sea to train his crew before the action with Hornet.

James also claimed that Penguin was quickly and shoddily constructed. However, Biddle, when first of the Wasp, had led the boarding party onto Frolic where he personally hauled down her colors and had been in the process of making repairs to her when Poictiers (74) arrived, recaptured her and captured the wounded Wasp. His assessment of Penguin has some validity considering this previous experience with Frolic. In addition, records for Penguin’s construction show it took ten months to build her and five months to outfit her, a bit longer than average for the Cruizer-class brigs. James claims that many of Penguin’s carronades dismounted when fired during the engagement, but this fault with the carronades, based on a review of his accounts in The Naval History of Great Britain, occurred much more frequently in the actions against American opponents.

According to James, Biddle and Warrington learned of the end of the war from a neutral ship encountered en route to Tristan da Cunha but he neglects to mention where, when and from what ship they received this news. He alleges they ignored this information in order to enrich themselves with prize money. If greed was his motivation, then why did Biddle engage Penguin in an even match considering the risk involved to himself, his crew and his ship?

During James’s discussion of Hornet’s crew size and the number of casualties Hornet suffered, he made the most astonishing accusations. He claimed that Mr. King (or Kirk, the name varies in James’s two books), a midshipman from Penguin, upon coming on board Hornet after the battle, observed American crewmen throwing dead – and wounded – overboard. James said this was done in order to conceal from the British prisoners the true size of Hornet’s crew and the number of casualties. He also claimed this was done because the American surgeon was incompetent and the wounded may die under his treatment. Finally, James alleges that a drunken Captain Biddle corroborated all of James’s assertions at dinner with one of Penguin’s officers without giving a hint to his source.

Several hours after the end of the action Peacock and Tom Bowline arrived at the rendezvous. After assessing Penguin’s damage and thoroughly examining her, Biddle removed the useable stores and scuttled her before daylight the next morning, 24 March. James Biddle regretted very much the need to scuttle her because he found her to be a new, well built and very fine example of her class but too damaged to repair and survive the long voyage back to the States. Master Commandant Lewis Warrington of the Peacock, as the most senior officer at the rendezvous, decided to transport the prisoners to San Salvador, Brazil on Tom Bowline. Peacock and Hornet remained at Tristan da Cunha until 13 April waiting for President, as ordered by Commodore Decatur. The hired store brig Macedonian arrived with news of President’s probable fate sometime in this period of waiting.

Peacock and Hornet continued east where they sighted on 27 April what they thought was a large East Indiaman east of the Cape of Good Hope. As they closed, Warrington and Biddle realized their mistake soon after the unknown sail turned to meet them rather than running. It was the 74 gun ship of the line HMS Cornwallis. Peacock escaped without difficulty, being both larger and faster than her companion. Hornet finally escaped three days later on 30 April only after throwing overboard all but one of her guns, most of her shot, all her spare spars, her anchors and anchor cables, boats, forge, small arms and even some of her food and water and some ballast. Hornet twice came under the fire of Cornwallis’s bow chasers and suffered some damage including one shot that penetrated the hull below the waterline, but no casualties. Of course, James Biddle had no choice but to order Hornet back home. She arrived in New York 30 July.

Peacock continued across the Indian Ocean, captured and burned three or four prizes, then encountered the East India Company cruiser Nautilus (14 guns, 4 long 9s and 10 x 18 pound carronades, 80 men, 180 tons) in the Sunda Strait connecting the Indian Ocean and the Java Sea on 30 June 1815 near Anjier. The vessels approached to within hailing distance when Lieutenant Boyce in command of Nautilus informed Peacock of the end of the war but Warrington, thinking the claim to be a ruse to allow Nautilus to escape under the guns of the Anjier shore battery, opened fire when Boyce refused to haul down his colors as Warrington ordered. Nautilus struck her colors after two broadsides. She suffered heavy damage and casualties of 7 dead and 7 wounded including Lt. Boyce. Warrington released her the next morning, assisted in making repairs and set course back to the United States, arriving in New York on 30 October. As soon as the news of the encounter reached Britain and the United States, Warrington received criticism for his handling of it. Roosevelt said of it some 70 years later, “There could not have been a more satisfactory exhibition of skill than that given by Captain Warrington; but I regret to say that it is difficult to believe he acted with proper humanity.”

The engagement between Hornet and Penguin was the last battle of the war and the action of Peacock against Nautilus the last exchange of fire.

In 1818-1819, Hornet operated in the West Indies and the Mediterranean and in the 1820s participated in the suppression of piracy in the Caribbean. She foundered with the loss all hands in a storm near Tampico, Mexico on 29 September 1829.

James Biddle continued his career in the US Navy, eventually attaining the rank of Commodore, the highest rank in the US Navy before 1862. In 1846, he negotiated the first treaty between China and the United States. Later that year, he also attempted to negotiate a similar treaty with the Japanese Tokugawa Shogunate, but at first contact, a samurai guard knocked Commodore Biddle down and threatened him with his drawn sword, ending the attempt. Commodore Perry succeeded seven years later. David Connor, first officer on Hornet, also attained the rank of Commodore.

As an alternative subject for Caldercraft’s Cruizer, Penguin would need a change in armament to 32 pounder carronades plus the 12 pounder boat gun and the addition of the fore and aft platforms like those on Snake.

Next: Cruizer, the original of the class, followed by Weazel

Sources:

Naval Occurrences by William James, 1817

The Naval History of Great Britain by William James, 1824

History of the Navy of the United States by J. Fenimore Cooper, 1836

The Naval War of 1812 by Theodore Roosevelt, 1900

The Age of Fighting Sail by C. S. Forester, 1957

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Dept US Navy, (online)

“NMM, vessel ID 373130”, Warship Histories, vol v, National Maritime Museum (online)

“HMS Penguin (1813)”, “USS Hornet (1805)”, “Sinking of HMS Penguin”, articles on Wikipedia (online)

Master Commandant James Biddle’s action report dated 25 March 1815 as recorded in the US Congressional record (posted on ancestry.com)

-

MV Elda, aka Empire Atoll (1941-46) and Hadrian Coast (1946-67)

-

I spoke too soon.

Just a few minutes ago while reading the accounts of the HMS Penguin (a Cruizer-class brig) v USS Hornet, I came across a footnote in Teddy Roosevelt's narrative of the War of 1812 in which he references a letter by Hornet's commander. In this letter Penguin was described as having swivel guns on the capstan and in the tops but no further details about them. Typical practice was that these "small arms" would not be set up except as part of clearing for action.

Just a few minutes ago while reading the accounts of the HMS Penguin (a Cruizer-class brig) v USS Hornet, I came across a footnote in Teddy Roosevelt's narrative of the War of 1812 in which he references a letter by Hornet's commander. In this letter Penguin was described as having swivel guns on the capstan and in the tops but no further details about them. Typical practice was that these "small arms" would not be set up except as part of clearing for action. -

In actual use true brass (an alloy of copper and zinc) was not used on ships because it would corrode and turn green very quickly in the salt water environment. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin which has very good resistance to corrosion and good strength but is much more reddish brown than brass. What was used was naval brass which is an alloy of copper with both tin (for corrosion resistance and strength) and zinc (for color and self-lubricating property).

In my research into the Cruizers I found a definite description of Commander Peake of the Cruizer-class Peacock (which had the reputation of being a "yacht" for her tasteful appearance) keeping the "brass" elevating screws and the brackets for the traversing wheels highly polished instead of exercising his crew at the guns which resulted in USS Hornet all but sinking her in 15 minutes of battle with almost no damage received. Peacock sank shortly after striking taking several crew members of both vessels with her who were trying to save her.

Manganese was not identified as a separate metal until just a few years before this period and was not isolated (it is naturally occurring in most iron ores) until a later time so there was no manganese bronze is this period.

I have also seen photos of period carronades that show a threaded bushing in the cascabel that the elevating screw passes through. This bushing may have threaded into the cascabel or may have been a press or interference fit. This would be a much better arrangement than having threads for the elevating screw cut directly into the cascabel for several very technical reasons which I won't go into here.

Jason, your cannons and carronades look great with the added details

-

The only Cruizer-class brig to be armed with 9 pounder long guns was Cruizer itself and those were changed out to 16 x 32 pounder carronades + 2 x 6 pound guns before any of her 105+/- sister ships were built. At least two Cruizers had 24 pounder carronades substituted for the 32s, in one documented case after the captain threw most of his battery overboard to survive a storm. So far my research into the Cruizers (which is by no means comprehensive) suggests that the fore and aft platforms were common, if not universal, on the sisters to Cruizer. Many Cruizers, when refitted for the American theater at the outbreak of the War of 1812, were also armed with a 12 pounder "boat gun" - a 12 pounder carronade with trunnions mounted on a standard gun carriage. In some cases captains added to this armament with a second boat gun or another 6 pounder or two. For example, the Cruizer Frolic when it met USS Wasp had two additional brass 6 pounders at the transom ports (how those were worked is beyond my comprehension given the space limitations under the aft platform) the 12 pound boat gun set up on the forward platform and a very recently acquired 12 pound boat gun barrel lashed down on deck which the captain planned to re-mount and set up on the aft platform. Commander William Layman took command of Raven when it came off the ways in 1804 and removed the 2 x 6 pounders, re-planked over the forward gun ports (not the bridle ports) and the transom ports and then mounted a 68 pounder carronade

on a transverse (rotating) carriage on each of the modified fore and aft platforms.

on a transverse (rotating) carriage on each of the modified fore and aft platforms.The Snake and Victor ship-rigged sloops were armed as Caldercraft supplies the kit as listed above. By the way the masts on Victor were located a little differently than on Snake (NMM Greenwich has copies of the original plans available if someone wanted to build Victor instead of Snake).

Based on my monitoring of all the Snake builds (in preparation for bashing Cruizer slightly to build one of her sisters) it appears that the aftermarket 32s sit a bit tall for the gun ports without reworking them. Substituting aftermarket 24s or even 18s might remedy this and would be indistinguishable from the 32s except to someone who can spot the difference by eye alone.

Swivel guns were considered small arms, like muskets and pistols, and I have not seen any mention of them in my research into the Cruizers. I have seen them mentioned on privateers but their crews had a profit motive and would be reluctant to damage a potential prize making swivel guns an alternative. I did find reference to 4 pound guns in the tops of USS Hornet in 1813.

And thanks for the plug, Jason, you're very kind!

I envy the very nice work all you guys are doing on what is turning into a very interesting group build of Snake. You are all going to be tough acts to follow.

- Brigg Fair, drtrap and mort stoll

-

3

3

-

Very good David.

Your turn.

-

-

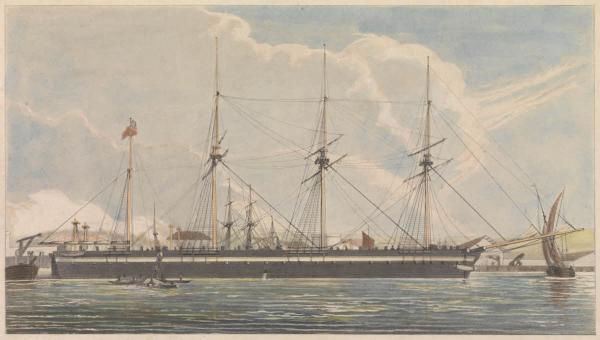

HMS Queen Charlotte, renamed HMS Excellent as part of the Maritime Warfare School.

-

Thank you, Jason.

I covered HMS Pelican's victory over Argus. What more do you want?

I'm looking for a Cruizer-class brig-sloop to examine after Penguin, but I'm not finding sources like those for the War of 1812 ship battles.

-

Cruizers, part 7: HMS Avon

The Cruizer-class brig-sloop HMS Avon launched on 31 January 1805, commissioned in February and set sail for the Mediterranean on 18 April with Commander Francis Jackson Snell in command.

HMS Avon’s Specifications

Length: 100 ft 0 in (gundeck), 77 ft 3 1/2 in (keel)

Beam: 30 ft 6 in

Tonnage: 382 (bm)

Rig: brig-rigged sloop

Armament: 16 x 32 pounder carronades + 2 x 6 pounder chase guns

Complement: 117, 4 short of full complement of 121

Avon captured a smuggling vessel in May and shared with Pomone (38) the recapture of a British ship with a French prize crew in January 1806.

Commander James Stewart took over command in March through May 1806 when Commander Mauritius Adolphus Newton De Stark received command and orders for Channel patrol. When Napoleon started hostilities with Russia the Admiralty ordered Avon as escort to the Russian exploratory vessel Neva on its return to the Baltic. For this service, De Stark received 100 golden guineas and a breakfast service of plate from Tsar Alexander of Russia.

Avon sailed on 28 August 1806 for North America carrying Mr. Erskine, HM Minister to the United States. En route De Stark evaded the cannon fire from the French 74 Regulus in an eight hour chase. After disembarking the minister at Annapolis Royal on 30 October, Avon stopped an American vessel for a routine examination and found dispatches from a French admiral on board. She arrived at Spithead on 7 January 1807.

Commander Thomas Thrush received command of Avon with orders to prepare for service on the Jamaica station and he set sail on 16 April 1807. During a storm, lightening struck Avon, which caused a lot of damage but no casualties. Thrush also took advantage of an opportunity to transport £103,000 in coin from Cartagena to Britain earning him a commission of £2,056. On 1 May 1809, Thrush received promotion to post-captain and a new command.

Commander Henry T. Fraser took command in June 1809. On 15 March 1810, Avon and Rainbow (28) encountered the French Nereide (38) which took to her heels. In the ensuing chase Rainbow made better speed than Avon. The separation between them eventually allowed Nereide to turn on Rainbow and batter her enough to give up the chase before Avon could catch up. Fraser on Avon continued the pursuit of the escaping Nereide and engaged her in a 30 minute battle that forced Avon to abandon the chase and retreat towards Rainbow. Nereide, unwilling to continue the fight, resumed her course to Brest.

On 3 December 1811, Avon, with Commander Percy in command, arrived in Portsmouth under jury masts.

On 22 July 1813, Commander George Sartorious took command of Avon and served on the Cork station until June 1814 when he received promotion to a post command.

Commander the Honourable James Arbuthnot recommissioned her in July. In the morning of 1 September, Avon, Castilian (another Cruizer brig) and Tartarus (16) recaptured Atlantic.

The American sloop-of-war Wasp, after burning Reindeer on 29 June, set course for L’Orient, captured a brig on 4 July, a schooner on 6 July and arrived on 8 July.

USS Wasp’s Specifications

Length: 117 ft

Beam: 31 ft 6 inches

Tonnage: 509 (burthen)

Rig: ship-rigged sloop

Armament: 20 x 32 pounder carronades + 2 x 12 pounder chase guns + 1 x 12 pounder carronade boat gun (from HMS Reindeer)

Complement: 173

Wasp, with Master Commandant Johnstone Blakeley still in command, put to sea on 27 August. On 30 August, she captured a brig and on 31 August captured another. Early in the morning of 1 September, she encountered a convoy of ten ships escorted by the 74 gun HMS Armada bound for Gibraltar. The swift cruiser hovered around the convoy and captured the Mary laden with iron and brass cannon, muskets and other military stores of great value. After taking off the crew, she was burned and Wasp tried to capture another but eventually gave up due to the effective defense of the convoy by Armada.

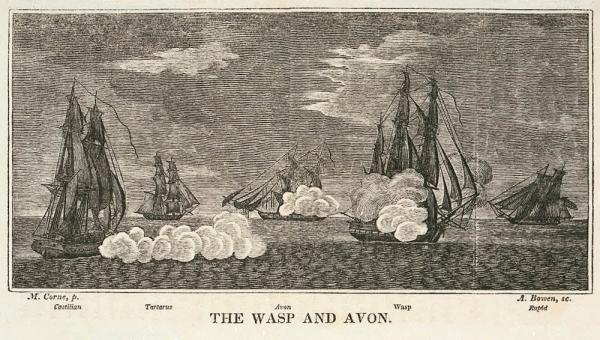

That evening at 6:30, while running essentially before a fresh southeast wind about 250 miles west of Brest, four sail were made out in the twilight, two off the starboard bow and two off the port bow more to leeward. Blakeley immediately ordered Wasp into pursuit of the closest to starboard, fully aware that any of the unidentified brigs might prove to be Royal Navy vessels. The chase was HMS Avon steering almost southwest with the wind abaft the port beam. At 7 pm, the chase made night signals with lanterns and flares but Wasp, disregarding them, came steadily on in the darkness. At 8:38 with the moon just past full rising in the east, Avon fired a shot from her stern chaser and another from one of her lee or starboard guns. At 9:20 with the Wasp positioned on the Avon’s weather quarter, the officers exchanged several hails and orders to heave to which were ignored by both sides. Avon then set her weather fore topmast studding sail.

At 9:29, Blakeley, making use of one of the lessons learned from his recent engagement with Reindeer, opened fire with his 12 pounder carronade shifting gun (the boat gun from Reindeer). Avon responded with her stern chaser and the aftermost larboard guns. Wasp steered diagonally across Avon’s wake, fired a raking broadside into her starboard quarter then ranged up alongside to prevent Avon from escaping downwind towards the other three brigs still in pursuit from leeward. Wasp’s first broadside cut Avon’s main gaff sail slings dumping the sail over the lee quarterdeck guns with the entire main mast falling within a few more broadsides.

At 10:00, with Avon unmanageable and no longer firing, Blakeley hailed to know if she had struck. With no answer and some firing from Avon, the action recommenced. At 10:12 after two more broadsides, he again hailed to know if the brig had struck and received the answer that she had. While lowering boats to take possession, the closest sail (the Castilian, Commander David Braimer) was seen astern. The men were called back to quarters and were put to work to repair damage as rapidly as possible but at 10:36 the other two sail (Tartarus, 16, and Rapid, 14) were seen closing in as well. Blakeley decided to put Wasp before the wind. Castilian pursued until she came up close, fired a broadside well over Wasp’s quarter, damaging some rigging, then returned to Avon which had been firing a gun as a distress signal.

USS Wasp and HM Brigs Avon, Castilian, Tarturus and Rapid

Collection of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich

Castilian returned to Avon at 10:55 when Arbuthnot informed Braimer that Avon was sinking rapidly and had no useable boats. Avon sank at 1:00 am, just minutes after the last of her crew had been taken off. Avon suffered 10 dead including her first lieutenant and 32 wounded including her captain, second lieutenant and one midshipman.

Wasp never learned the identity of any of the four brigs or that Avon sank. Two men were killed and one wounded (by a cannon wad) on Wasp during the action and she suffered only four round shot in her hull with some damage to her sails and rigging. Ten minutes after leaving Avon in a sinking condition, Wasp was ready and her captain and crew willing to engage Castilian until the sails of two more brigs appeared.

Wasp sailed generally south, captured and scuttled small brigs on 12 and 14 September then captured the Atalanta of 8 guns and 19 men 500 miles west southwest of Gibraltar on 21 September. Considering her and her cargo too valuable to destroy, Blakeley removed her officers and sent her with a midshipman, Mr. Geisinger, as prize master to Savannah, Georgia where she arrived on 4 November. On 9 October, Wasp came upon the Swedish merchantman Adonis about 400 miles west northwest of the Cape Verde Islands, took two American officers from the USS Essex aboard, transferred some of her prisoners to Adonis and sailed away headed for the Caribbean – and was never seen again.

HMS Castilian has the distinction of being the only Cruizer-class brig-sloop to fire on one of the large US Navy Sloops and survive.

Four Royal Navy vessels have borne the name “Avon” in her honor.

As an alternative subject for Caldercraft’s Cruizer, Avon or Castilian would need a change in the armament to 32 pounder carronades and the likely addition of the fore and aft platforms like those on Snake.

Next: HMS Penguin

Sources:

The Naval History of Great Britain by William James, 1824

History of the Navy of the United States by J. Fenimore Cooper, 1836

The Naval War of 1812 by Theodore Roosevelt, 1900

The Age of Fighting Sail by C. S. Forester, 1957

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Dept US Navy, (online)

“NMM, vessel ID 380427”, Warship Histories, vol v, National Maritime Museum (online)

“HMS Avon (1804)”, “USS Wasp (1814)”, “Sinking of HMS Avon”, articles on Wikipedia (online)

The London Gazette, 4 citations listed in “HMS Avon (1804)”, Wikipedia

Name the Ship Game

in Nautical/Naval History

Posted · Edited by DFellingham

I got confusing, mixed results.

In one location it's identified as Svetlana 1856-1892 and in another it's identified as her sister ship Boyarin 1856-? At a third location the English text says it's Svetlana but a hidden Russian caption says it's Boyarin.