-

Posts

987 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Waldemar

-

Once you get familiar with the above listed works, you will easily realise that the parameters adopted for this reconstruction, such as the most important length of the floors and the curvature of the frames, are in reality the standard values recommended for men-of-war. However, as soon as possible, I will try to show the method graphically in this log.

-

Jules, first and foremost in „lasts” cargo capacity was determined, and not the ship's displacement as you have stated. This is understandable, bearing in mind that usually ships' users were just interested in cargo capacity, while displacement was a useless value for them. Nevertheless, if you know of even one reverse case, please let me know. Let me also please explain the basics. Imagine a board floating horizontally in the water. This is the ship in your example. Even with little or no ballast, it is very stable, which is good for an artillery platform and bad for its sailing qualities, making the ship leewardly (unless very long) and liable to lose masts easily. The „Sankt Georg” is the opposite. For simplicity's sake, you can associate it with the same board, but held vertically by ballast. The ship is then softer, which is an advantage for masts durability and its crew well-being. Weatherliness gets better too. The ship's behaviour may be optimized by adding or taking off some ballast. The price to pay is to have more depth in hold and sailing in deeper waters only. And with deeper hulls you gain ballast capacity, still keeping the battery well out of the water level. If you really wish to know how the ship's hulls were shaped, you would better consult the historical sources, as I am now very busy preparing the working draughts for the model. For the first half of the 17th century I would recommend the following, which I consider of the most practical value: – Fernando Oliveira, Livro da fabrica das naos, ca. 1570–1580 – English so-called „Newton” manuscript of ca. 1600 – Manuel Fernandes, Livro das Traças de Carpintaria, 1616 – English anon. manuscript of ca. 1620 – Spanish government ordonances (dimension establishments) of 1607, 1613 and 1618 – Georges Fournier, Hydrographie, 1643 – Bushnell Edmund, The Compleat Ship-Wright, 1664 – Anthony Deane, Naval Architecture, 1670 Now, at the excellent at the time battery height of 5 1/2 feet, the „Sankt Georg” calculated displacement is about 460 tons, and for 5 feet it is 490 tons. It was also calculated that with the gravity centre not being above the level of the main battery barrels in the waist, the ship would get upright from „any” (practical) list. My guess is that the cargo capacity of 200 lasts given in the inventory was estimated (usually by eye) as if for a merchantman of similar dimensions and even rounded, as was often the case for administrative purposes. The best, Waldemar

-

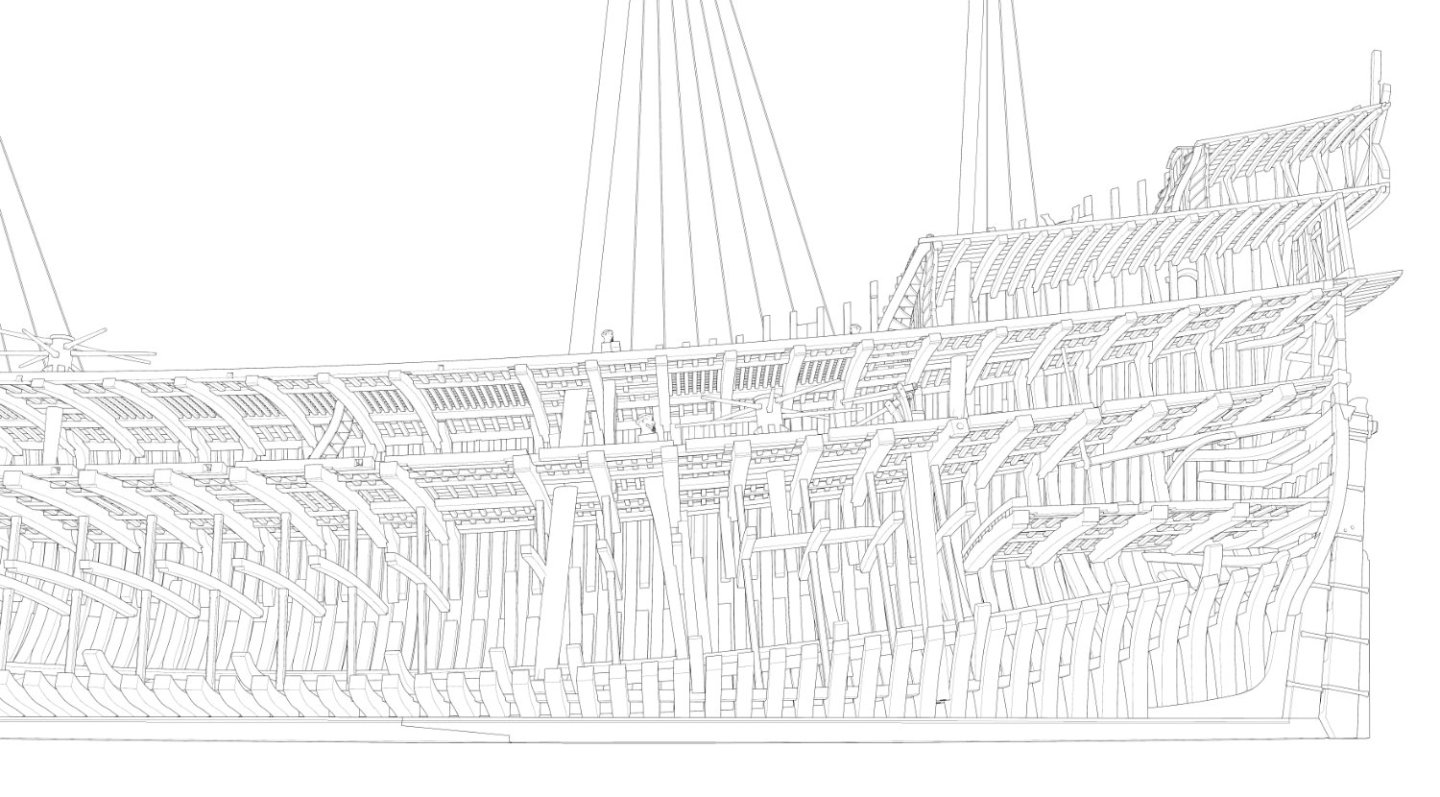

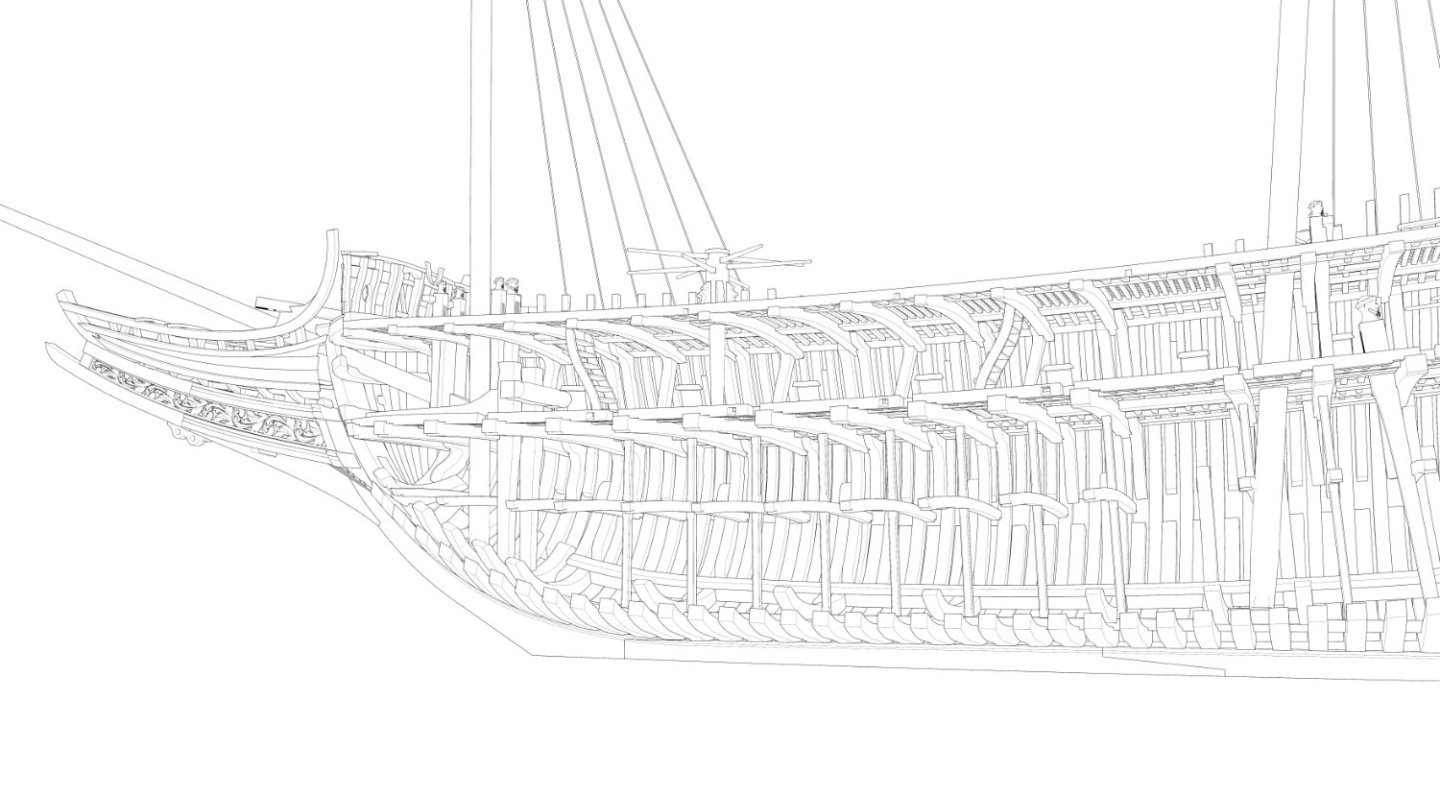

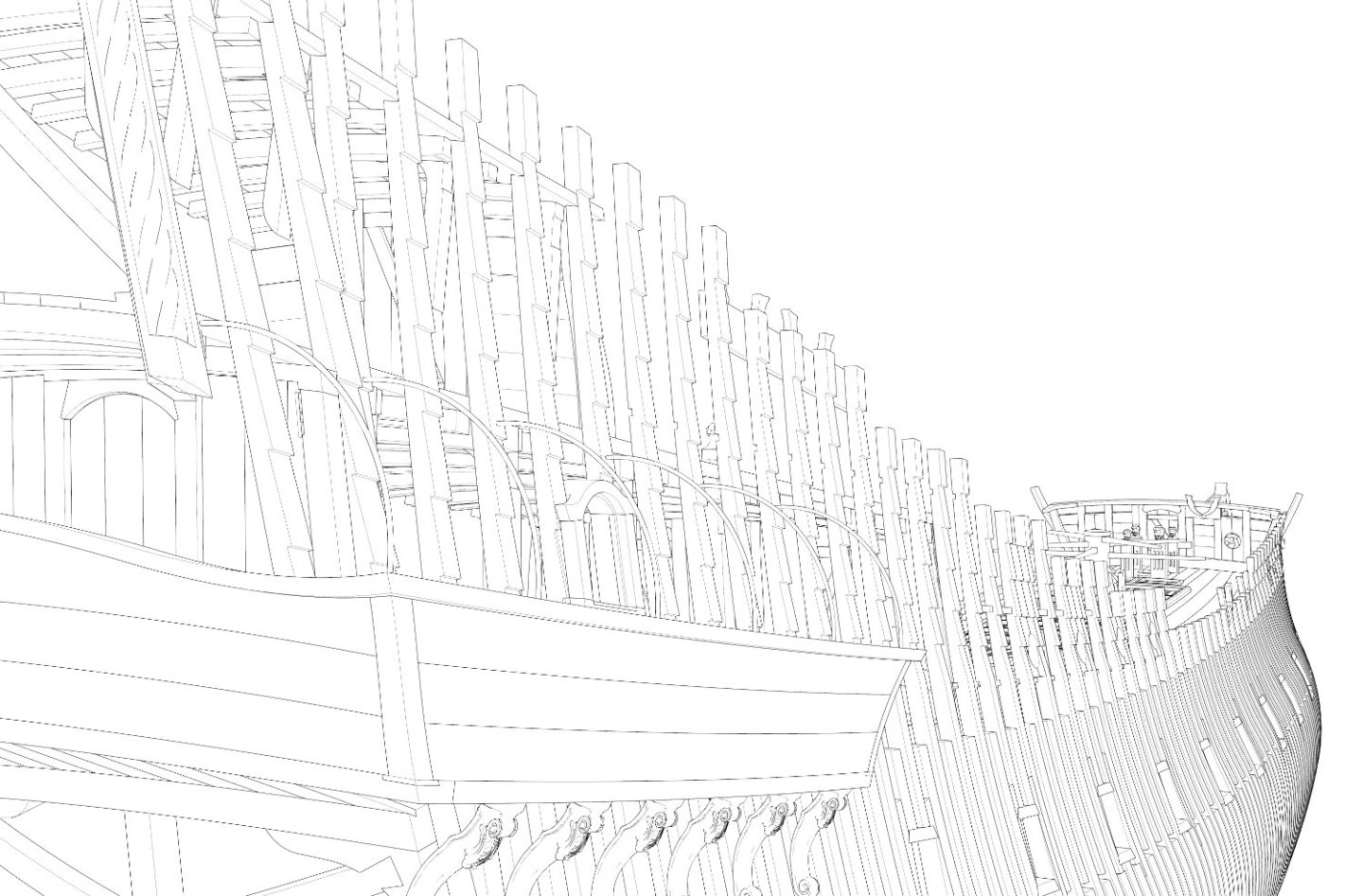

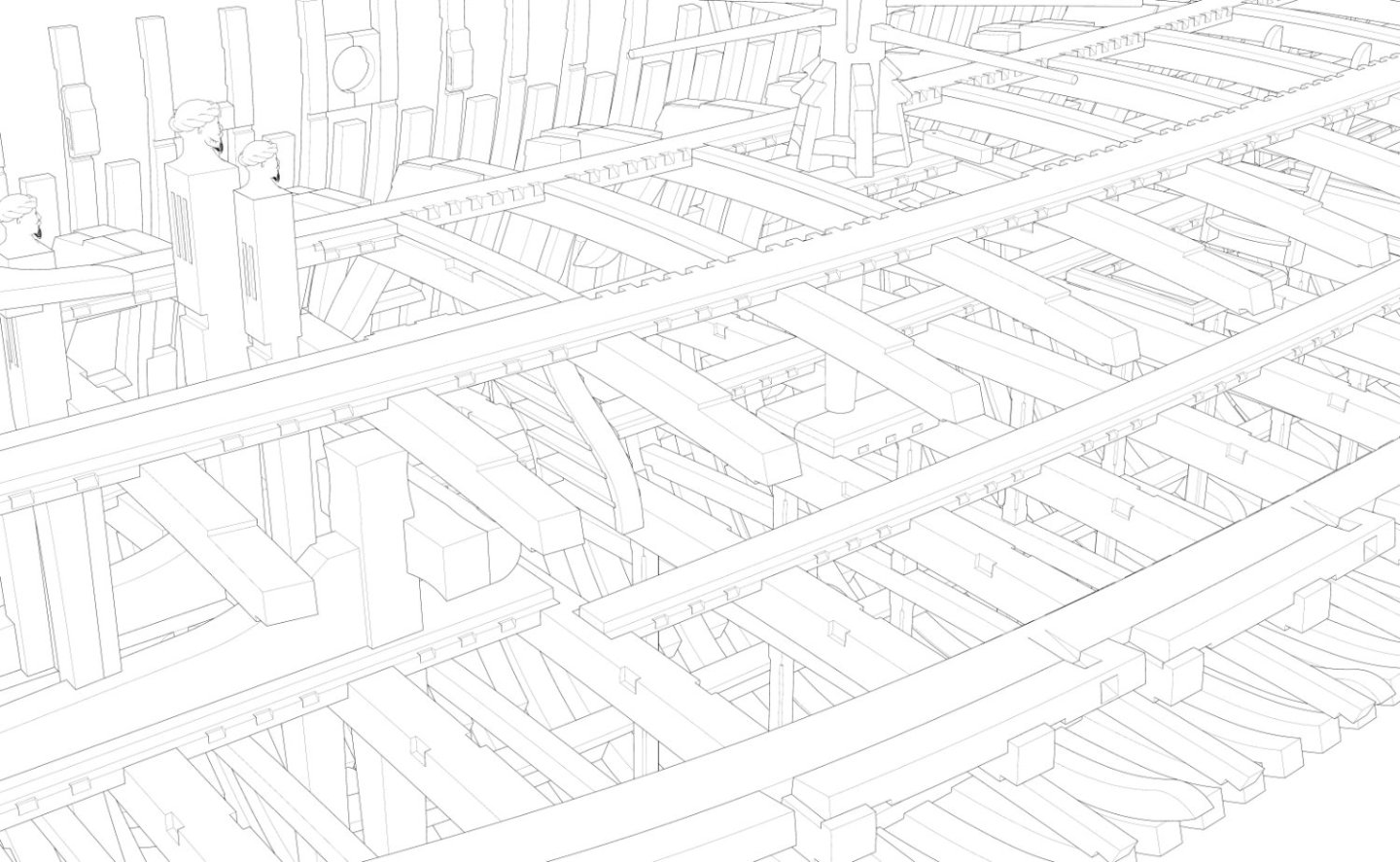

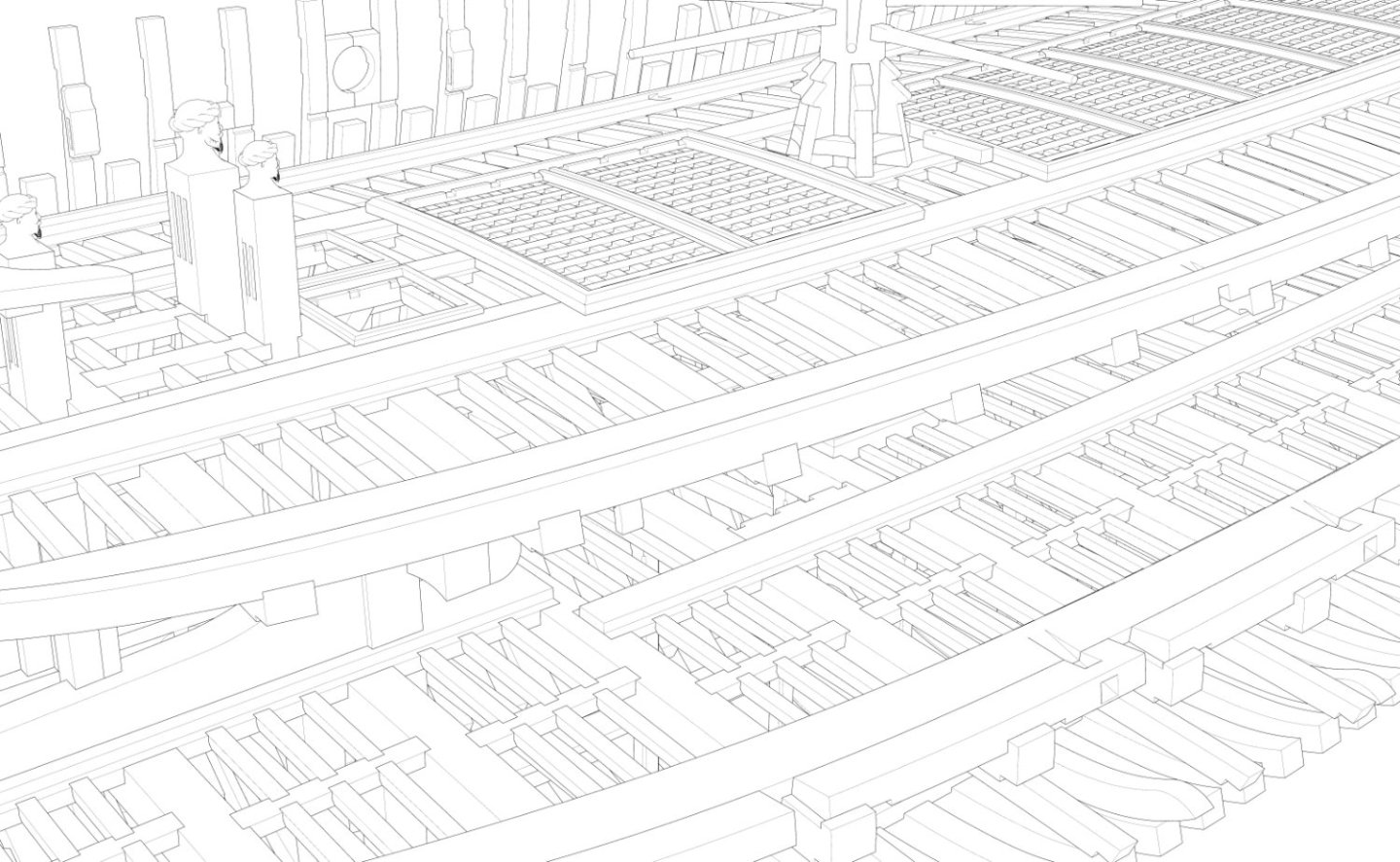

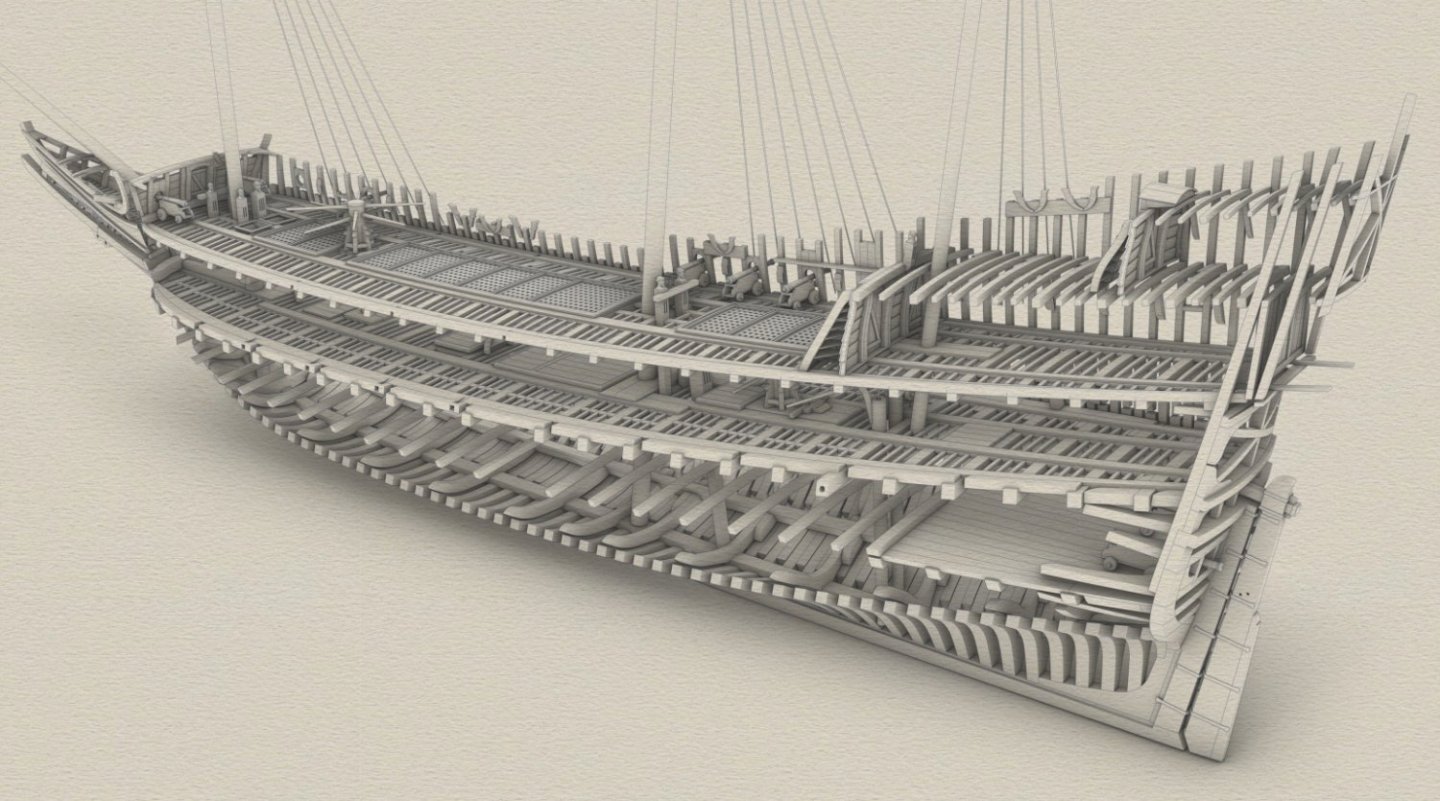

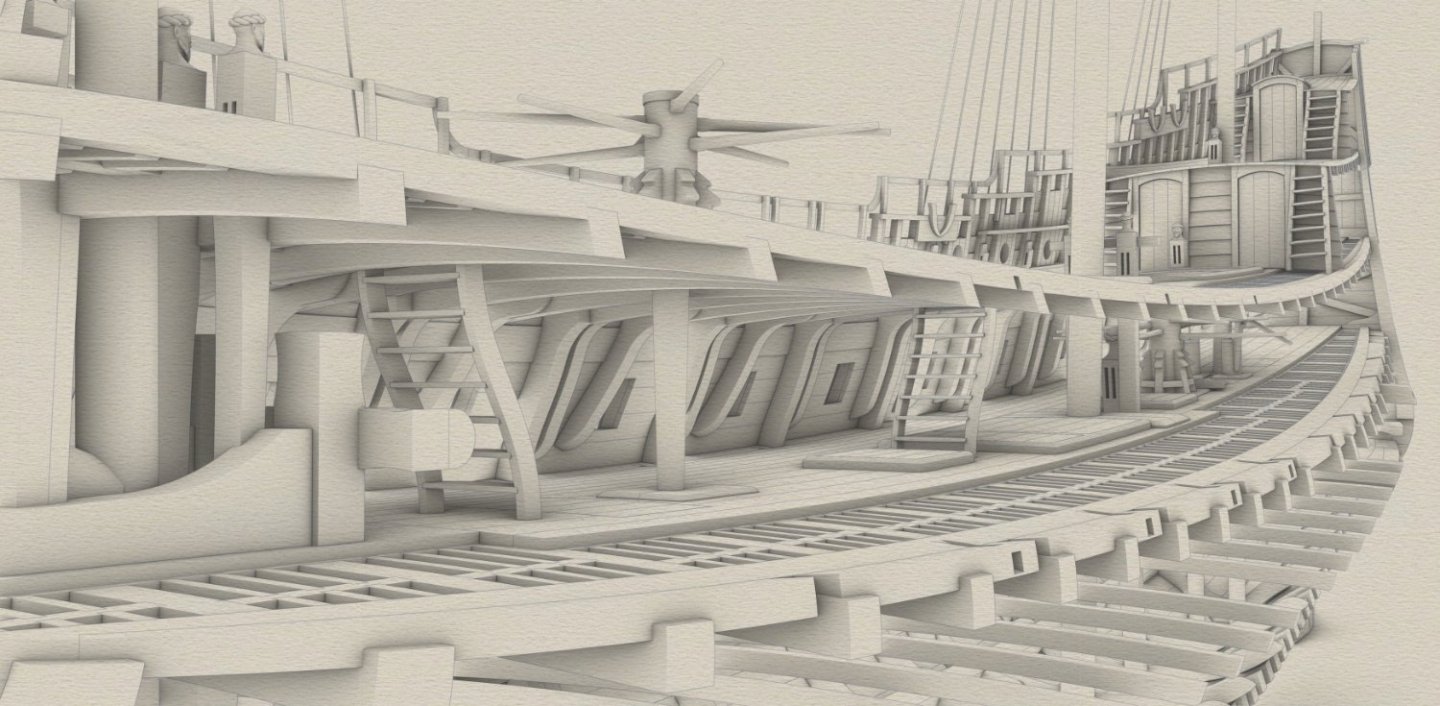

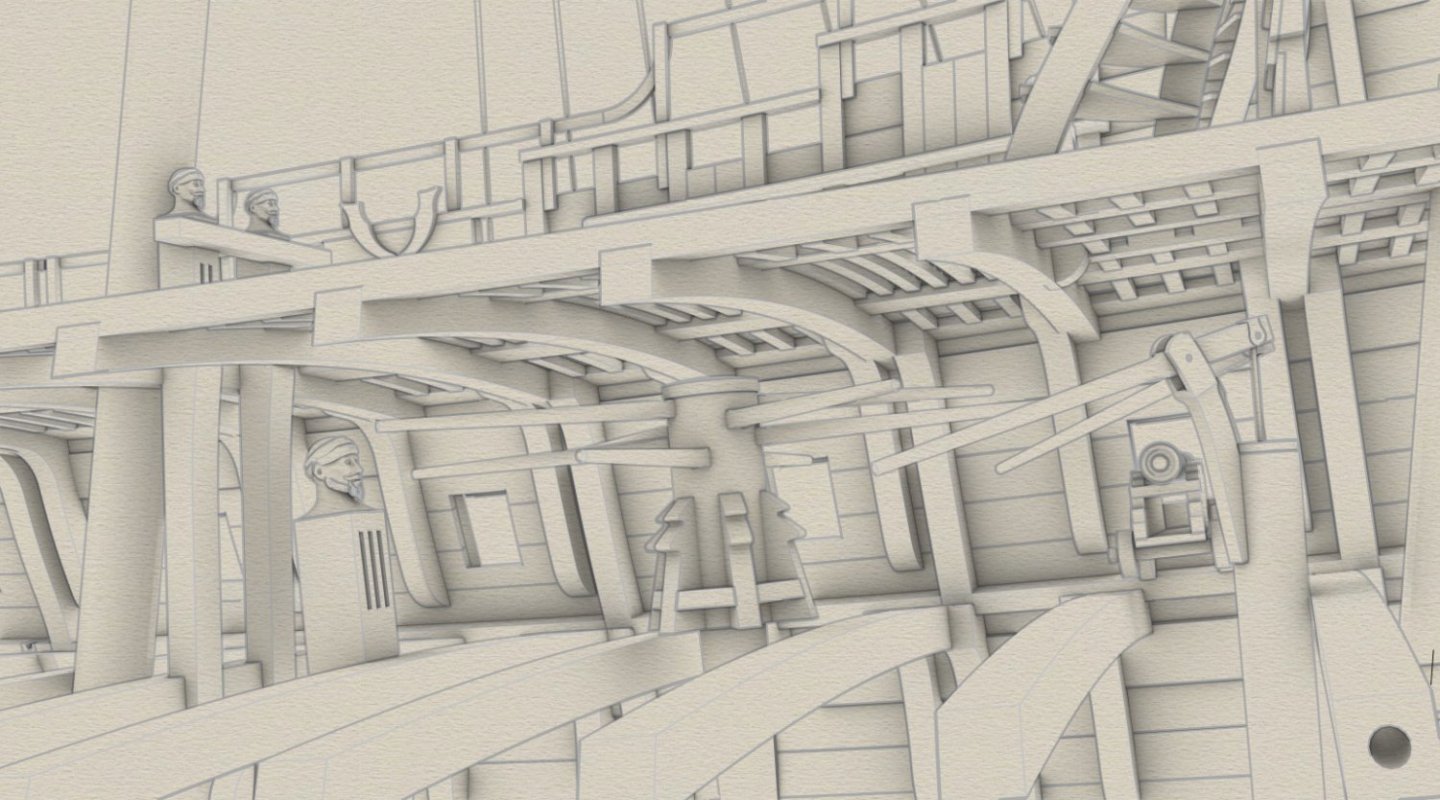

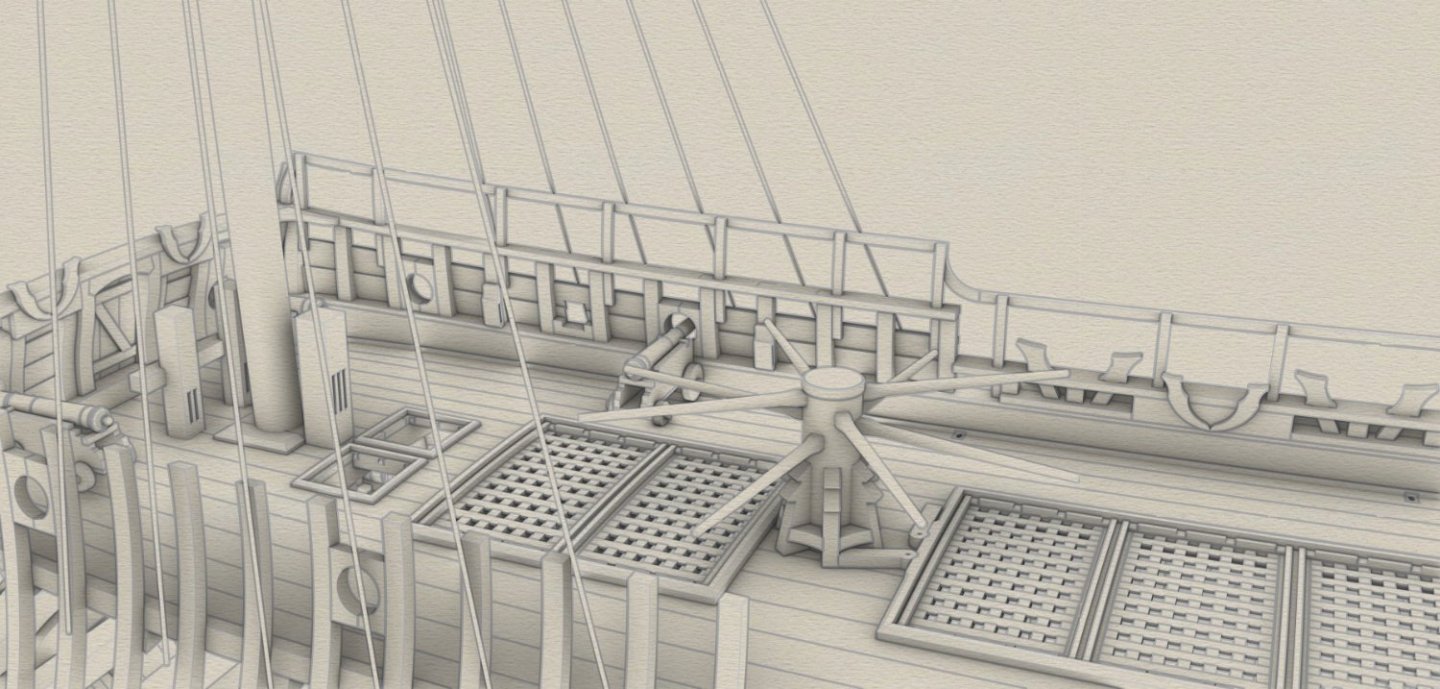

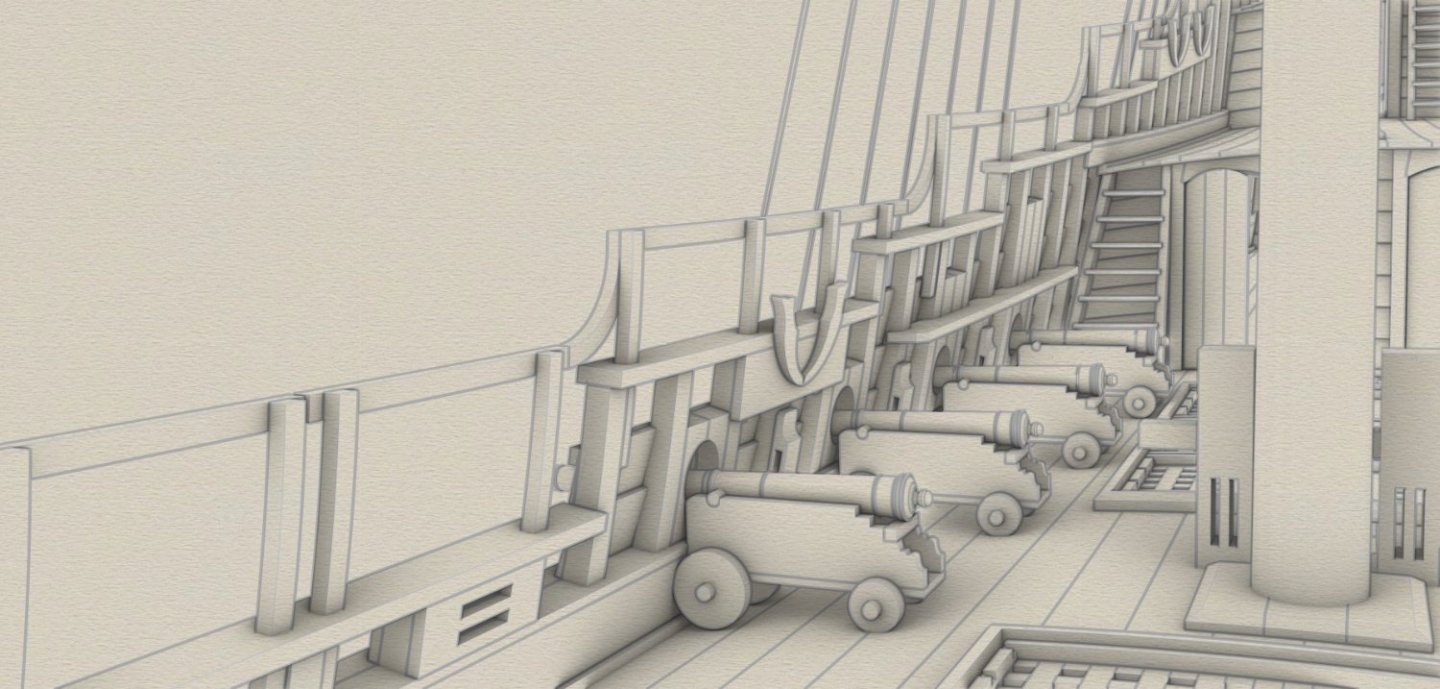

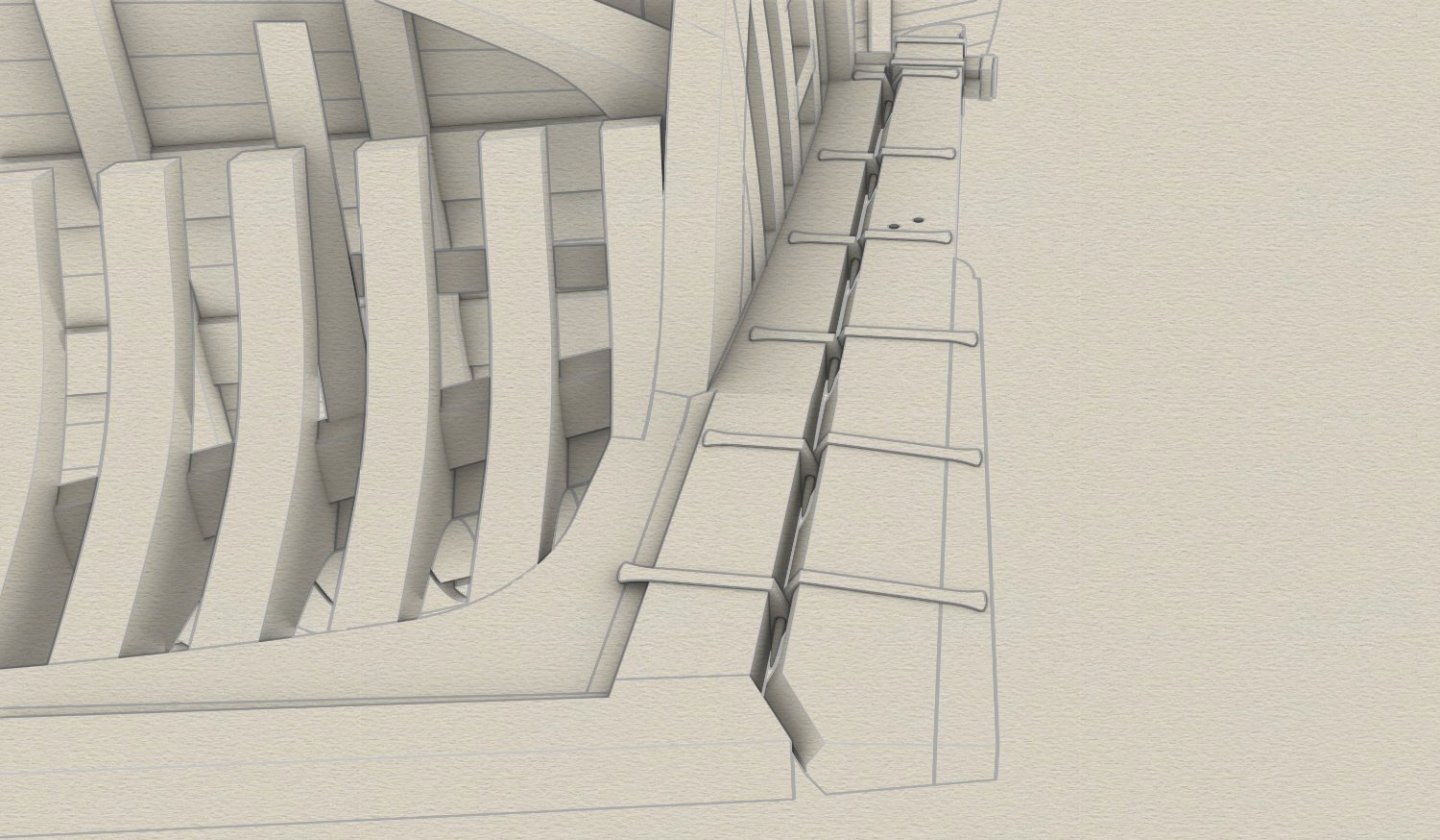

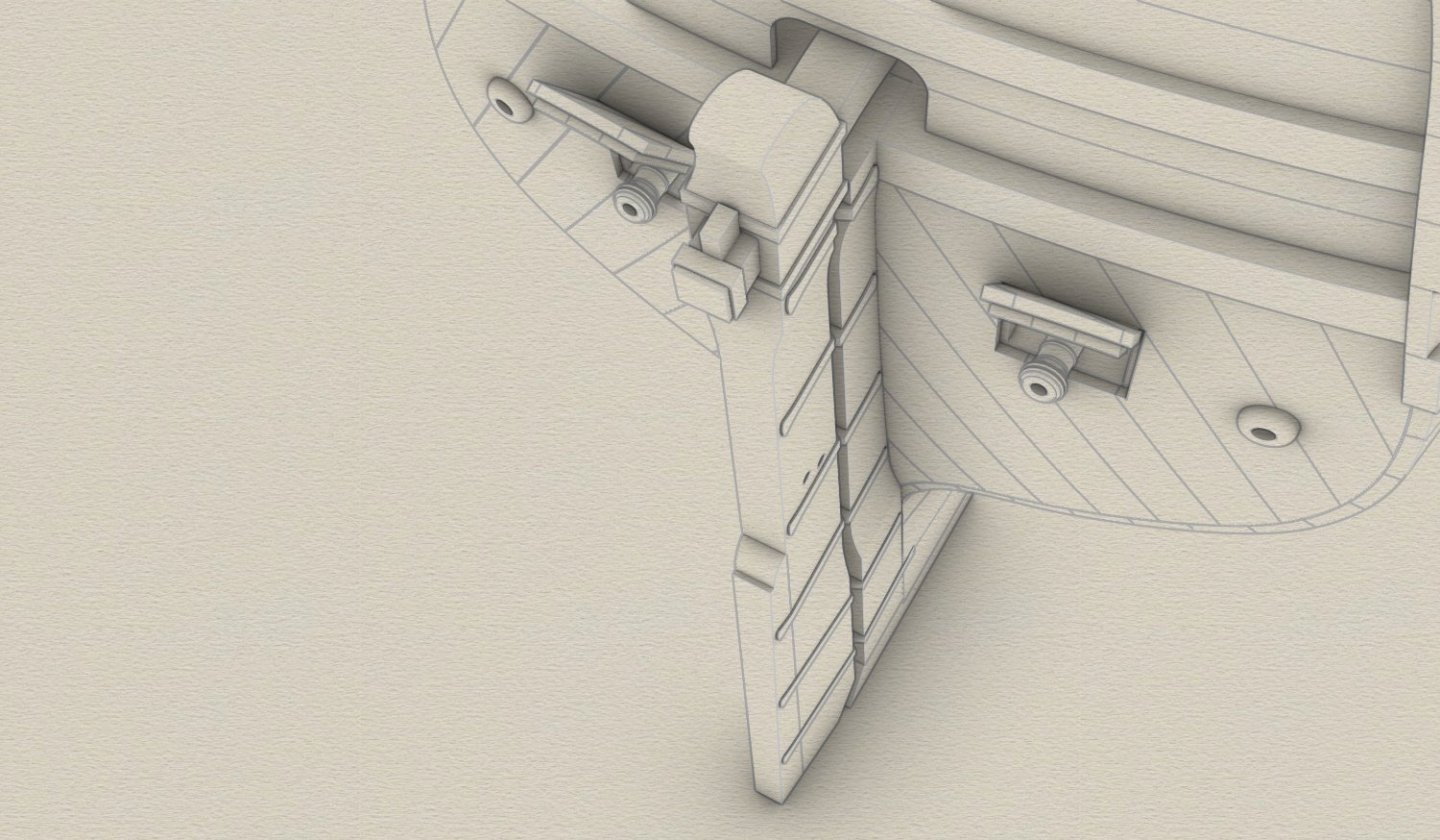

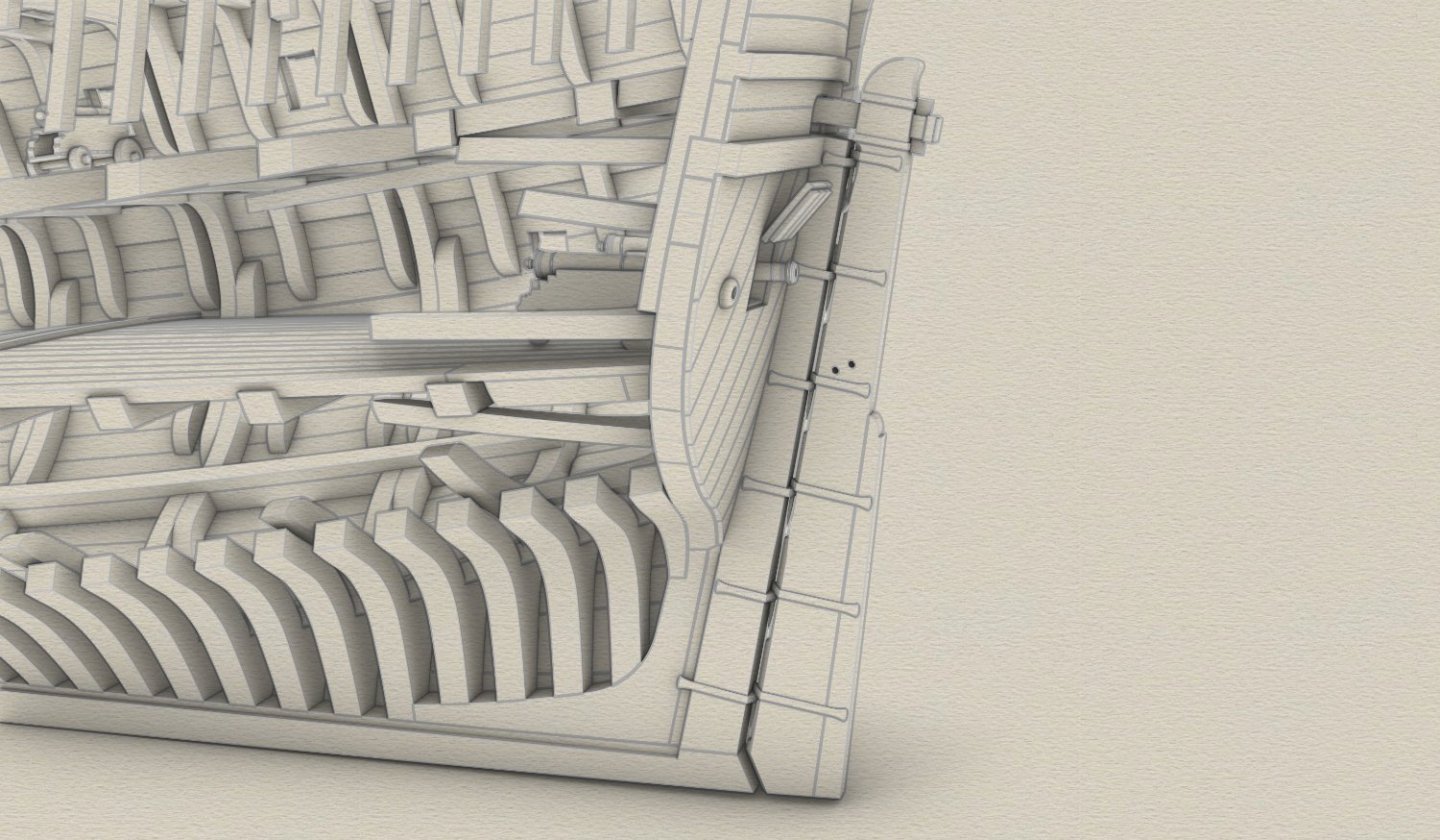

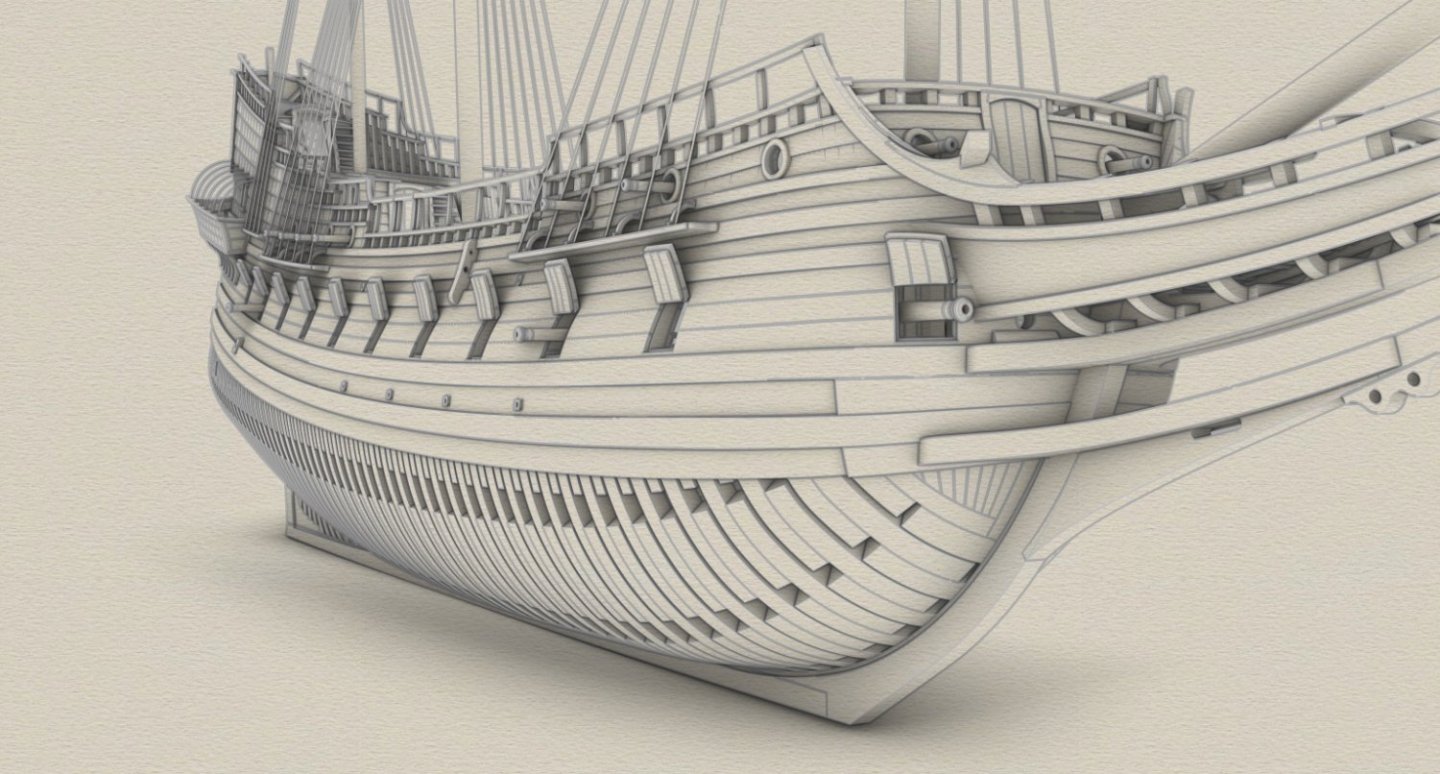

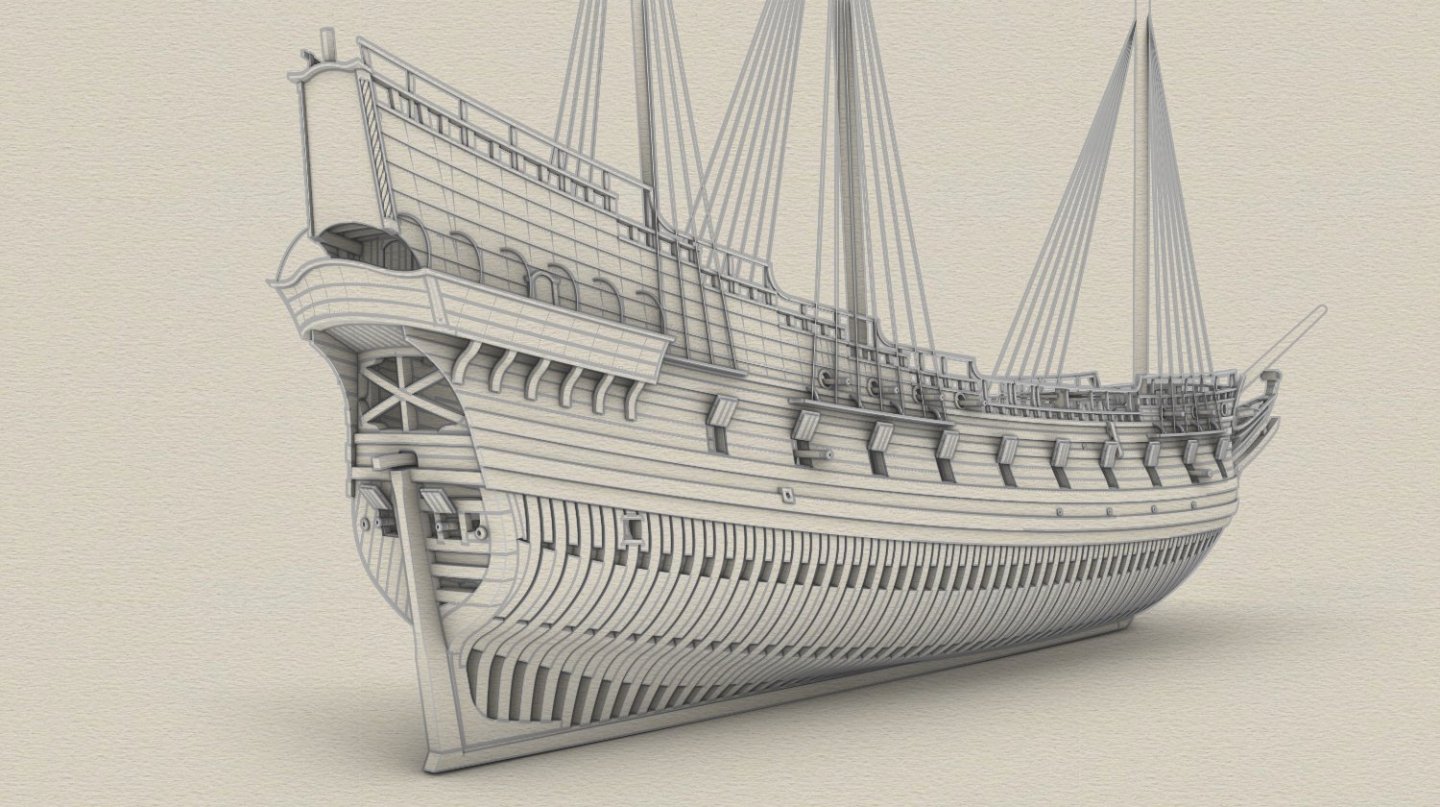

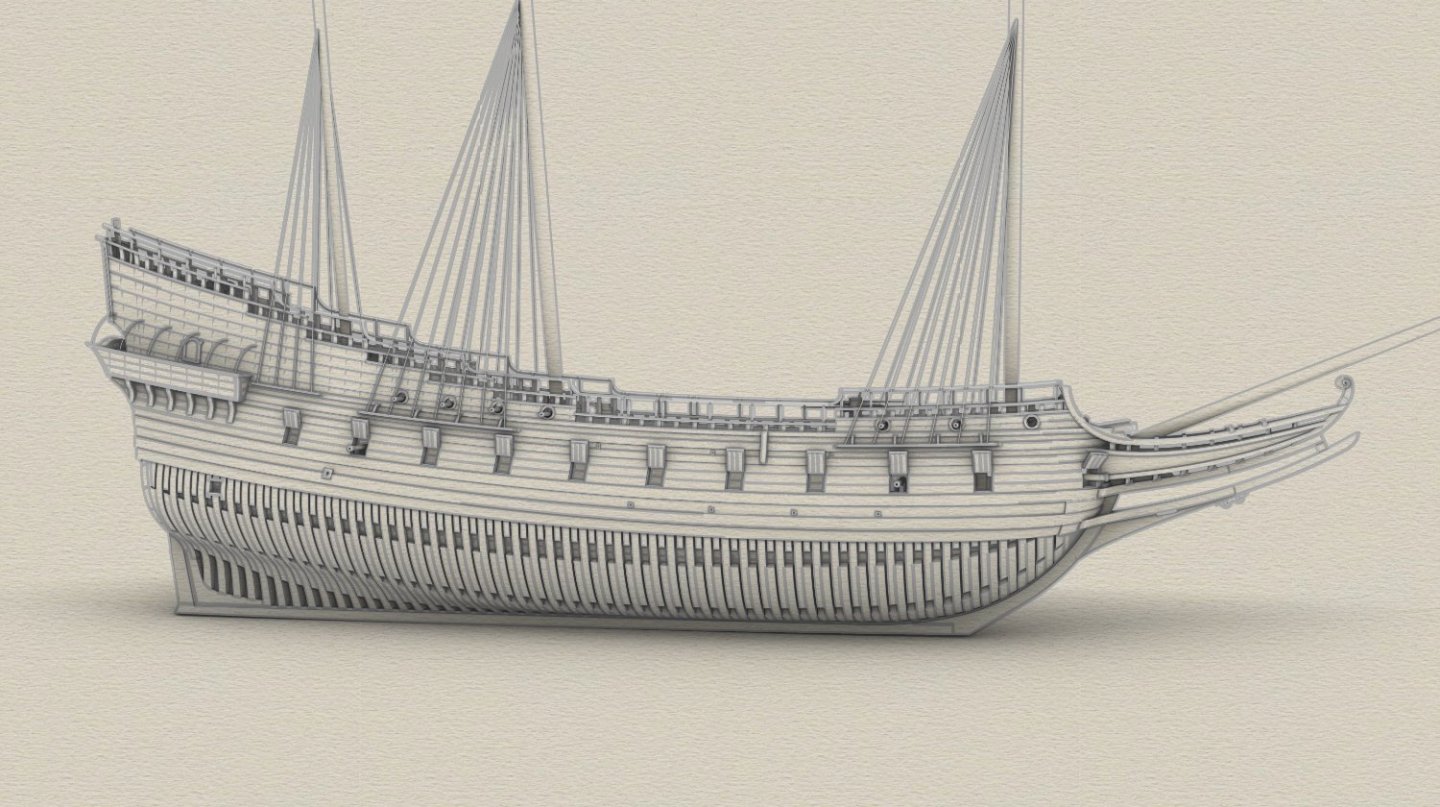

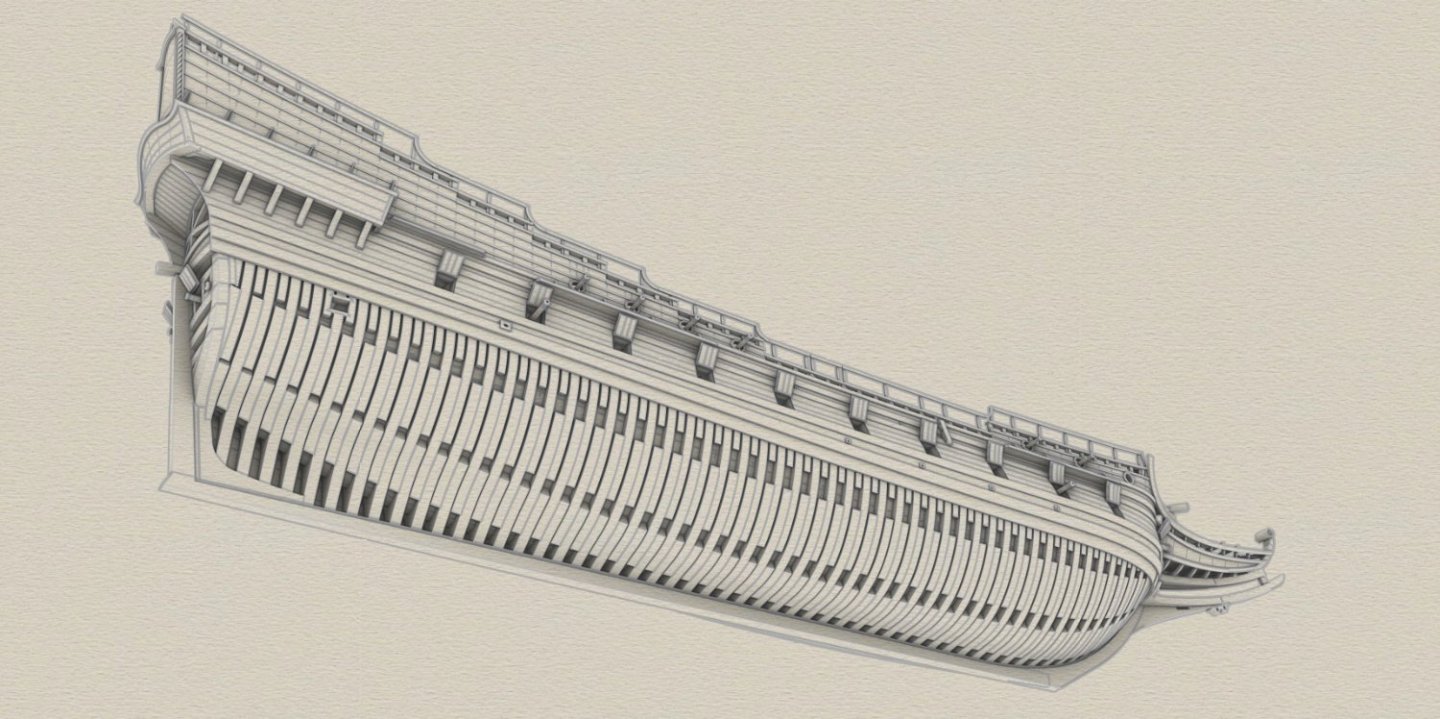

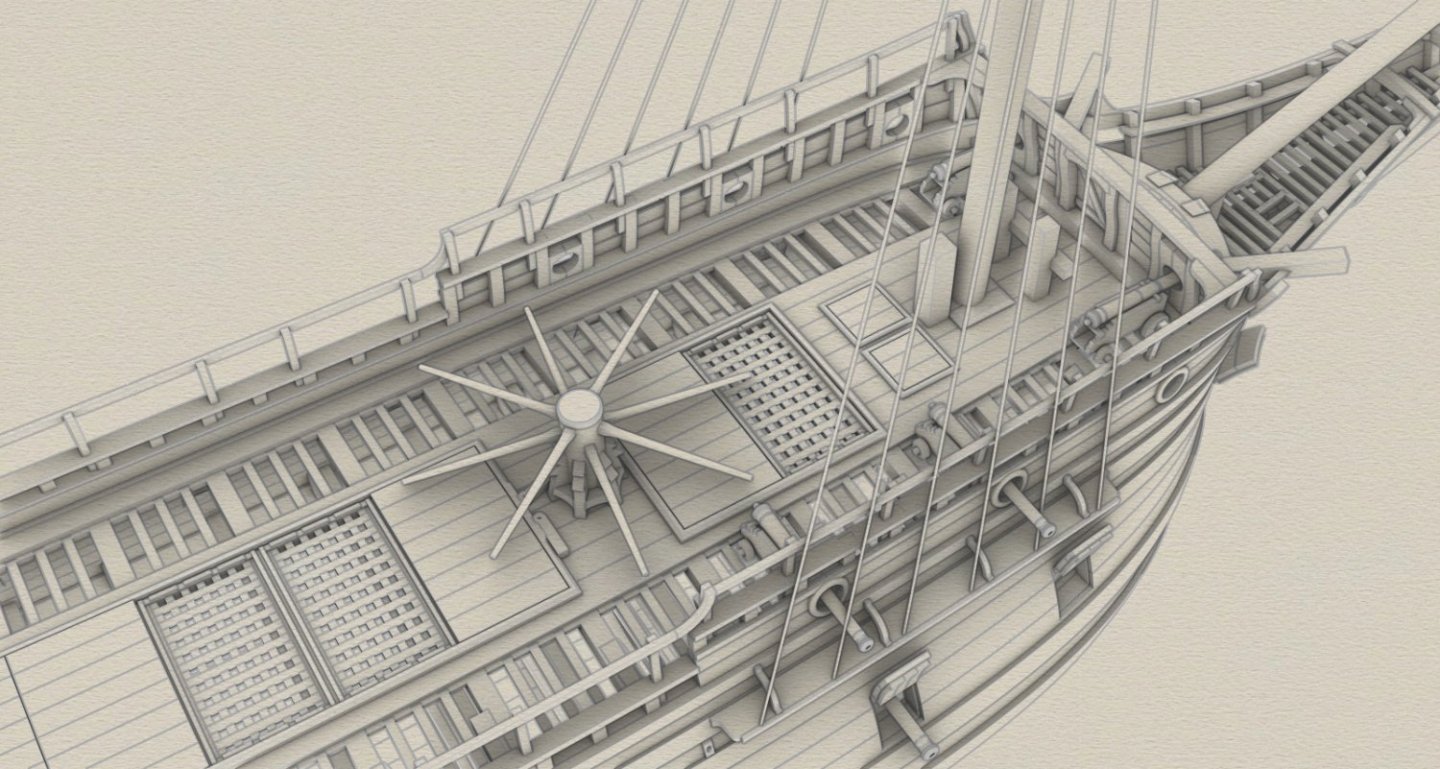

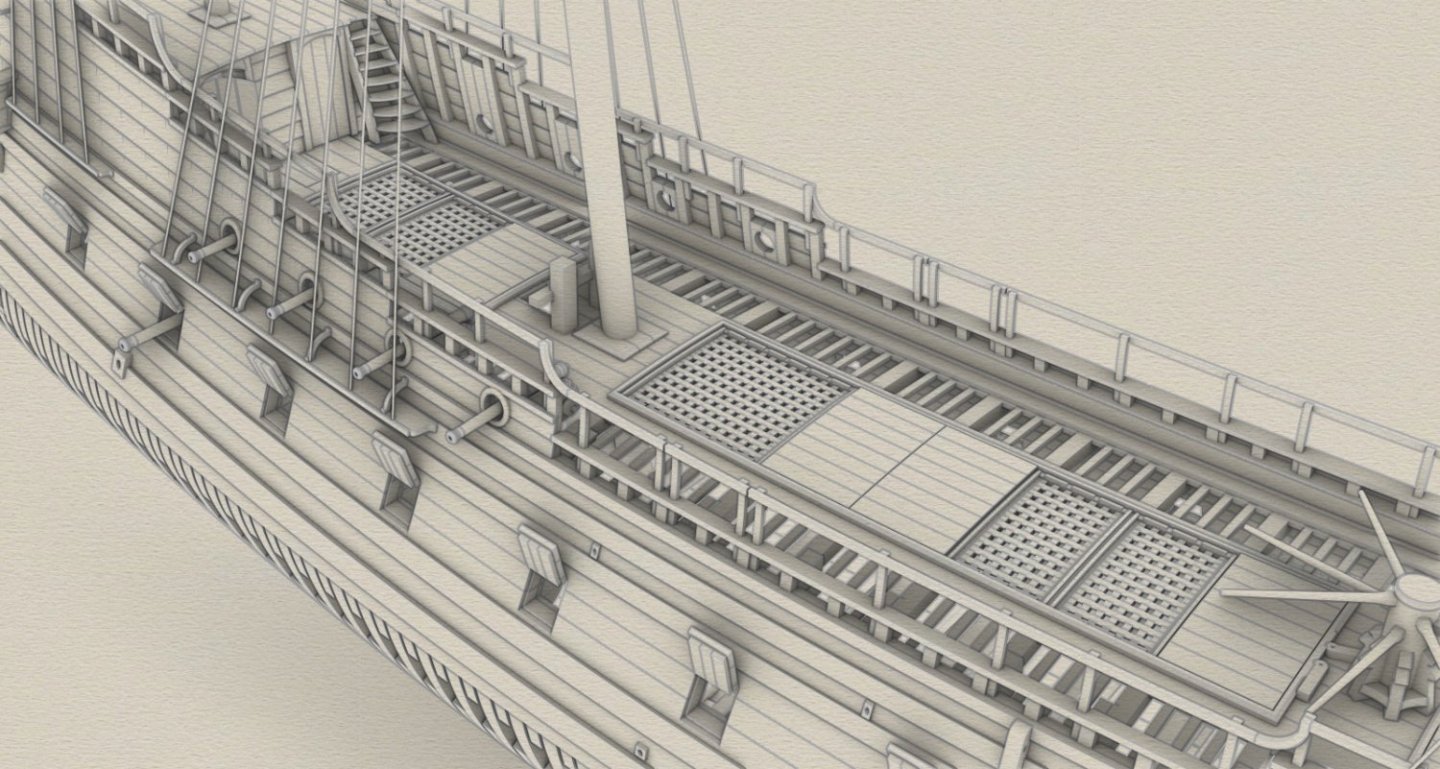

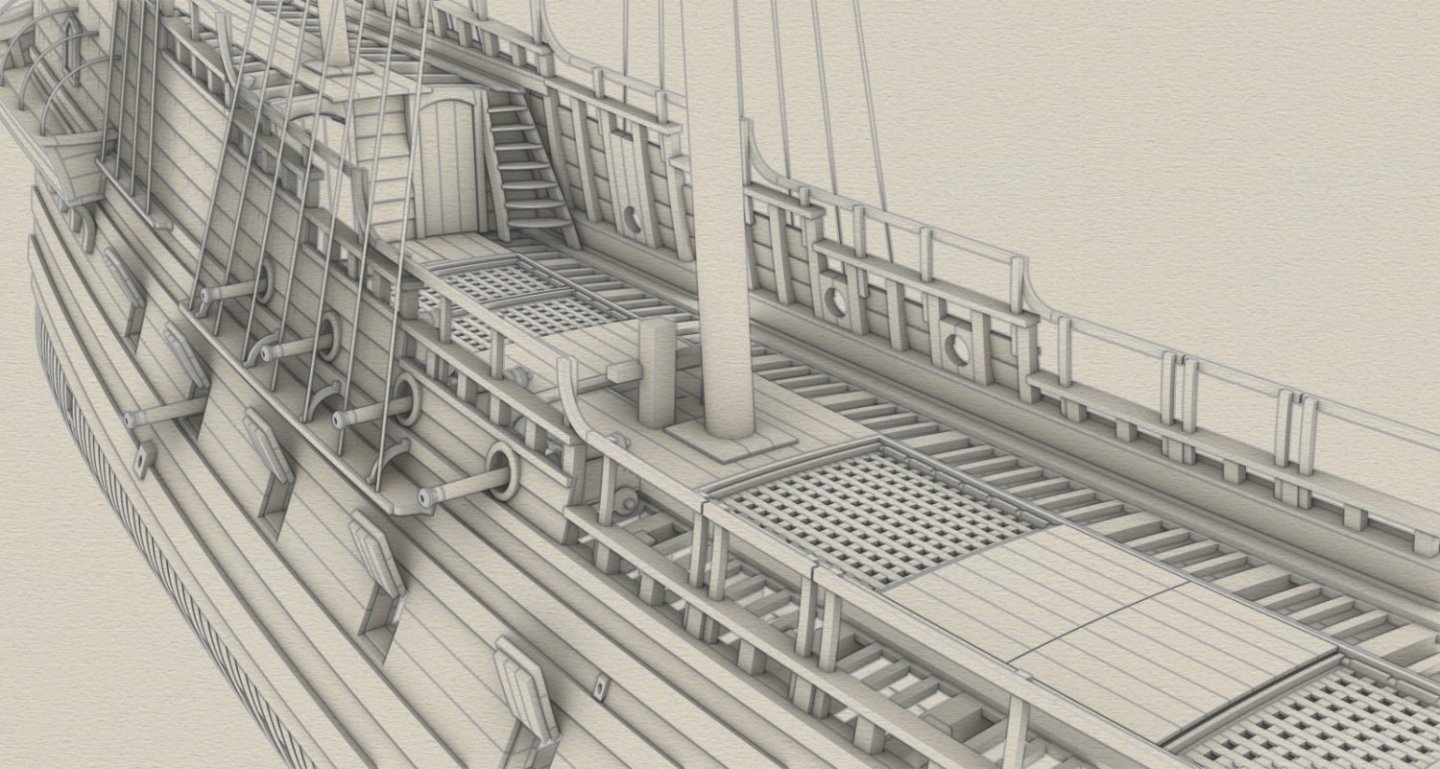

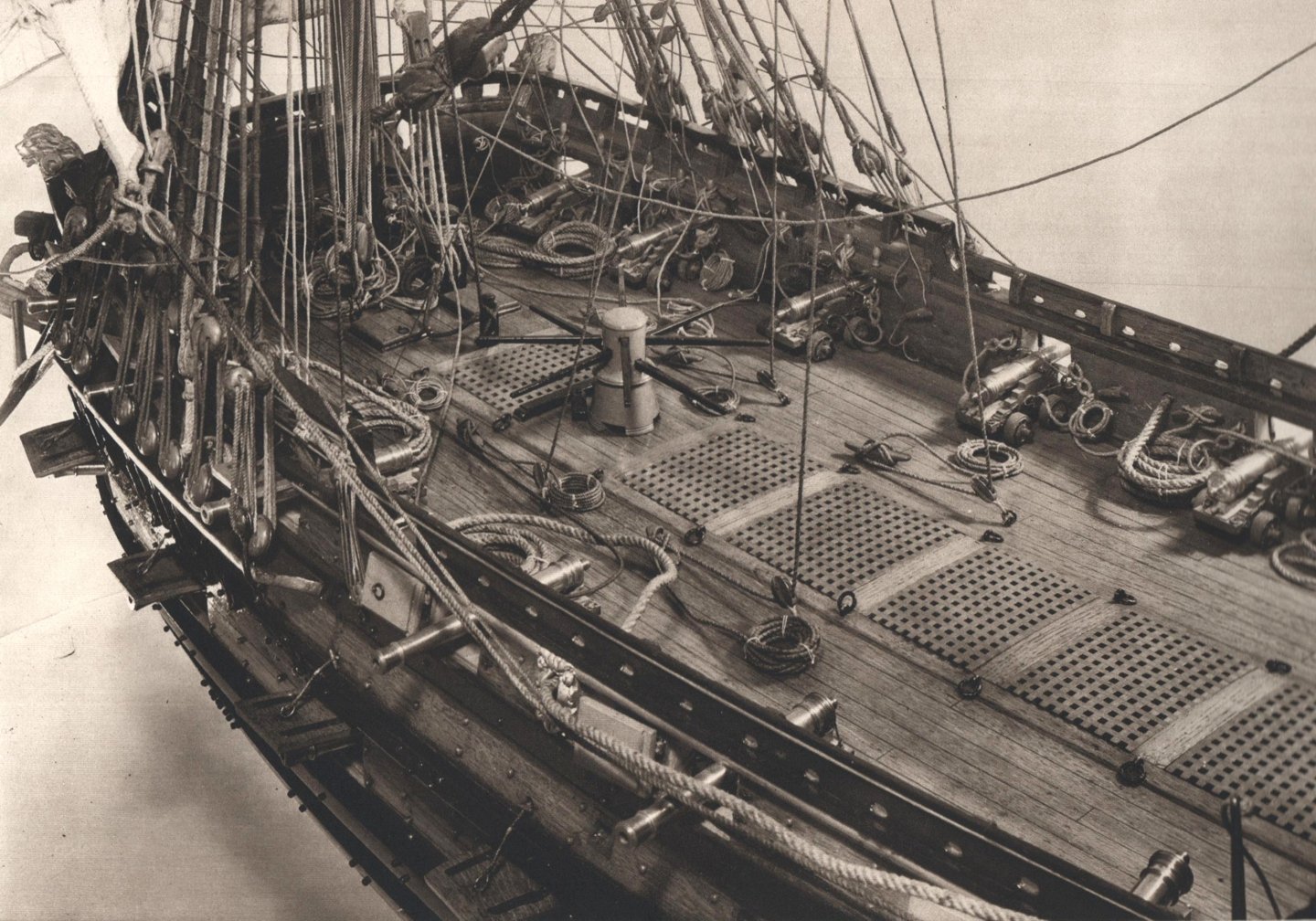

Now that all parts are already trimmed (i.e. cut to the nearest boundary), the so-called "Pen" display mode in Rhino may be used to its full potential. All polysurfaces of the 3D model are closed, no exceptions here. This „Pen” mode would also serve for producing any desired number of perspective or 2D projections. In the process, the weather deck (koebrug) structure has been completely rearranged by replacing all carlings, ledges and deck planks.

-

Hello Jules, Thanks for asking. This reconstruction is made on the order of Muzeum Gdańska (Danzig Museum) and in practice I was given a free hand in historical research regarding the ship's characteristics and construction. My concept was seemingly accepted and now the intention is to build a model of wood to the scale of 1:15 (hull alone of about 2,6 m). Most probably the ship was built by shipwrights from Gdańsk (Danzig) and Kołobrzeg (Kolberg) and entered service in 1627. Shipwrights from Gdańsk were German speaking Polish citizens, as was most of the ships' complement, command and fleet administration. The ship's main dimensions were taken directly from the other ship in the fleet of similar complement and armament – the „King David” (König David). The inventory for this ship reads: Das Schiff ist von 200 Lasten, 120 Fuss lang, 26 Fuss breit, 14 Fuss tief ins Raum, 6½ Schuh hoch zwischen dem Uberlauff undt der Koybrucken (length – 120 feet, beam – 26 feet, depth in hold 14 feet, distance between decks – 6½ feet). These proportions, while quite extreme for a man of war (especially length/breadth ratio), may be also found in other ships of Dutch origin or later French light frigates. The „Vasa” herself would have the same proportions if not slightly broadened during actual construction, upon a change in plans for heavier artillery, also requiring in turn stronger and heavier upperworks. The crew and armament for this ship are known and these were already given in this log. As a reminder – 50 sailors as a permanent crew and 100 infantry temporarily embarked for an expected battle.

-

I am still not convinced about the transverse stability of such watercraft, but I would certainly place such an exotic-looking object with attractive lines in my living room. Simplicity of the construction does not matter here. By the way, for some reason it seems to me that actually only ship models are suitable for display in presentation interiors. With perhaps a few exceptions. Sorry tanks, jets and spaceships 🙂.

-

Thank you very much for your comment Nicolas. Yet, somewhat ironically, I really only use a tiny fraction of Rhino's capabilities, still getting the shapes I want with the perfect fit. Believe me or not, but only a few basic functions and commands are constantly used in this project and, very occasionally, the more advanced ones if in trouble or need. So I think you can handle it perfectly as well, although to be honest I don't know the specifics and capabilities of Fusion 360. I think the secret lies not so much in a thorough knowledge of the software, but in the right philosophy of constructing a 3D model, especially of this kind. Generally, first I define the master surfaces of the hull, decks, stern "flat", beakhead, bulkheads, etc. True, some are simpler and others more complex to define, but well worth of effort, as these master surfaces are later an indispensable basis for creating the actual parts of the ship by offsetting them (not just moving!) and then cutting to shape. Almost nothing else but offsetting, cutting and other Boolean operations. Well, I know, easy said, but despite of thousands of interrelated parts already generated I am still able to control this beast... 🙂 Best regards

-

Due to the only one possible place for the fish-davit and its aperture, the fore gun ports had to be rearranged. Many other rigging-related fixtures, although inconspicuous in the images, were also made: kevels, pinrails, fixed blocks. In this type of reconstruction, at least 90% of the drawing time is consumed by various changes, corrections and fine-tuning.

-

Maybe so, but gold painting this nearly four-foot beast was a real horror show. Everything around became solar 🙂.

- 63 replies

-

- Finished

- Khufus Solar Boat

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hello Johnny, Many thanks for this log, as for some reason I also have a weakness for ancient Egyptian ships. I once made a simple block model of a solar barge myself, which I gave to my sister. If time permits, I will still try to build an Egyptian boat one day in the way you do.

- 63 replies

-

- Finished

- Khufus Solar Boat

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

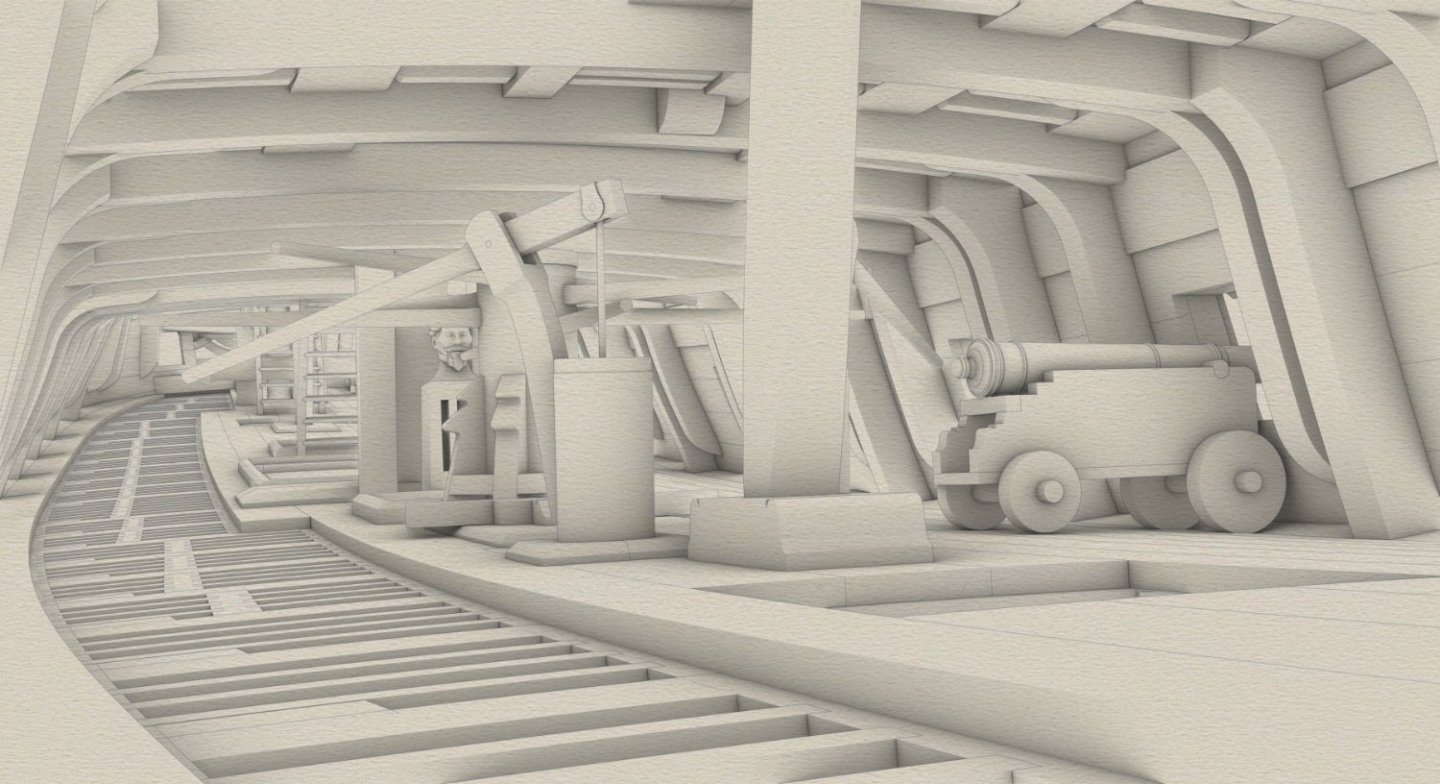

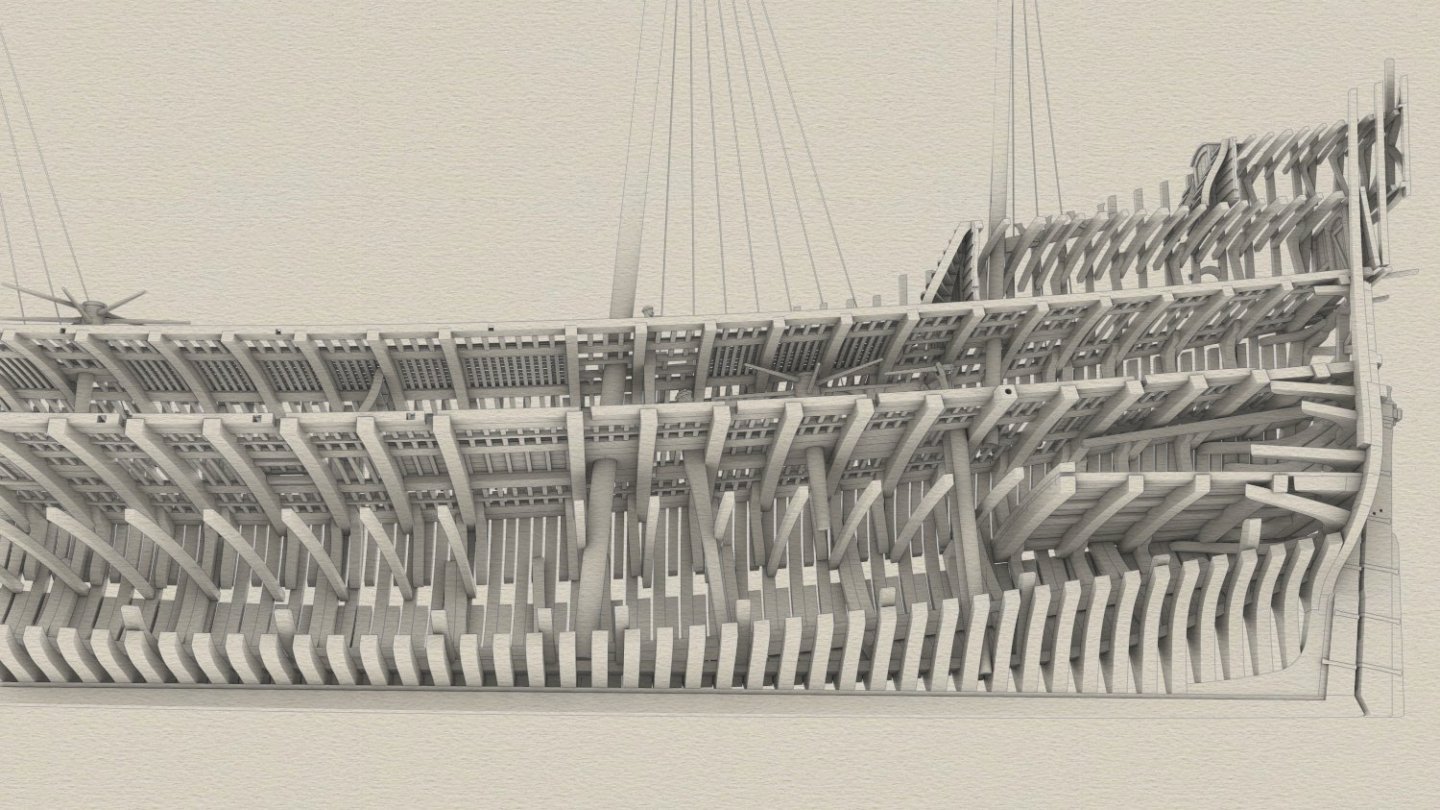

Many thanks Peter for your kind words. I took a break from drawing for a while. So no new elements, just playing with the Navy Board style for this model. Perhaps you will like it too. On the 3D model everything is tidy, but in reality the look of the framing would be closer to a mess. Note the removable part of the waistcloth frame close to the main hatch in the waist, making it easier to board the vessel.

-

These two ships you mention are from two different worlds. Again, simplifying somewhat, but to start somewhere: almost exactly in the middle of the 17th century there was a radical change in tactical doctrine, with shifting from boarding and small arms distance fight to gunnery duels (the First Anglo-Dutch War), and this affected not only the ships' design, but also the crew proportions, with sailors and gunners gradually taking over the infantry numbers on board. While building „Papegojan” of 1627 make sure there is enough room on board to live and fight for a squad of 60 infantrymen, besides 48 sailors. And this is a very small ship of only about 270 tons and the length of 86 feet. In my reconstruction she would have overloop (principal deck) serving both as a platform for the main battery and living quarters for the crew, and unbroken upper/weather deck for handling the ship and fighting infantry (very light, mostly gratings; it is called bovenet in the ship's inventory). In other words, the large body of infantry must have a place to fight, otherwise it would be useless. And no forecastle, to not make the ship unnecessarily top-heavy and leewardly. In the 1627 campaign the "Papegojan" served as supply ship and according to the ordnance inventory carried only four light guns (bronze 3-pdrs) instead of the usual a dozen or so. The frigates of the second half of the century are somewhat different proposition, but I do not know the frigate "Berlin" to make any reasonable comments.

-

Simplifying somewhat, the forecastle was an asset on merchant ships, but could be a nuisance on men-of-war in wartime, especially during battle. Its bulkhead took up available space (for artillery) and blocked the free movement of the crew. Due to the heavy loads (guns) above the waterline, as opposed to the merchant cargo held below in the hold, it was also desired to lower the gravity centre of of the whole as much as possible by removing it, if a merchant ship was pressed into the naval service. It had some advantages though. It made the ship drier in rough seas and was useful while defending the ship against entering party.

-

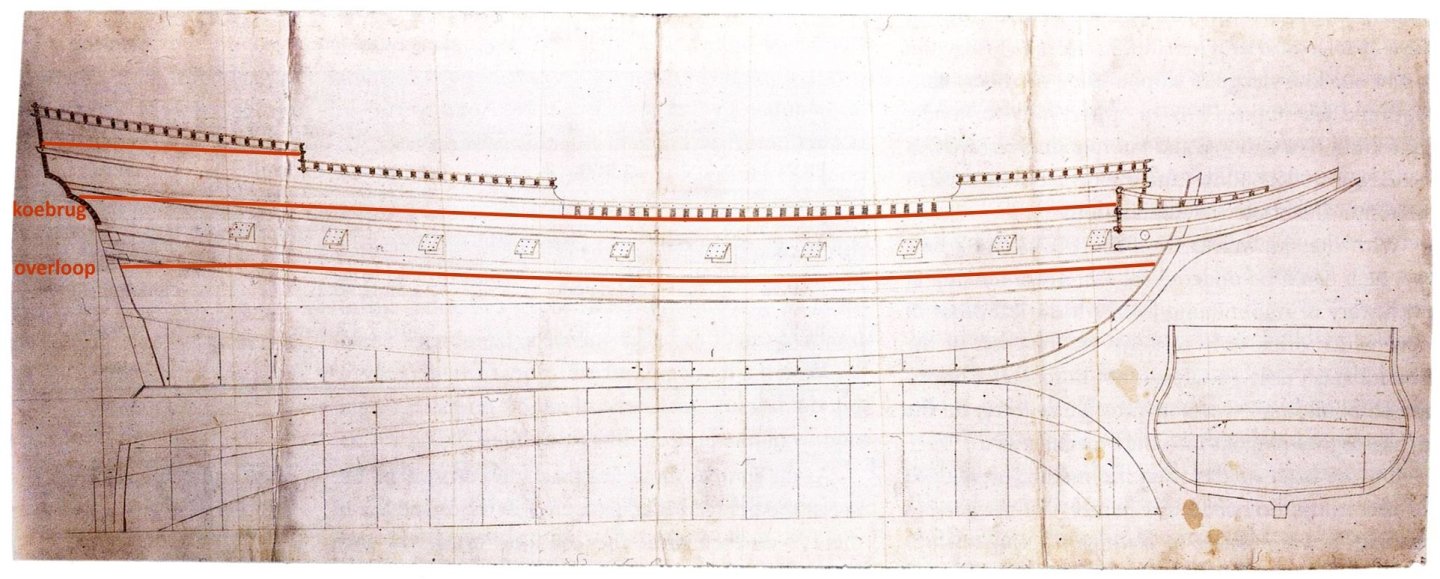

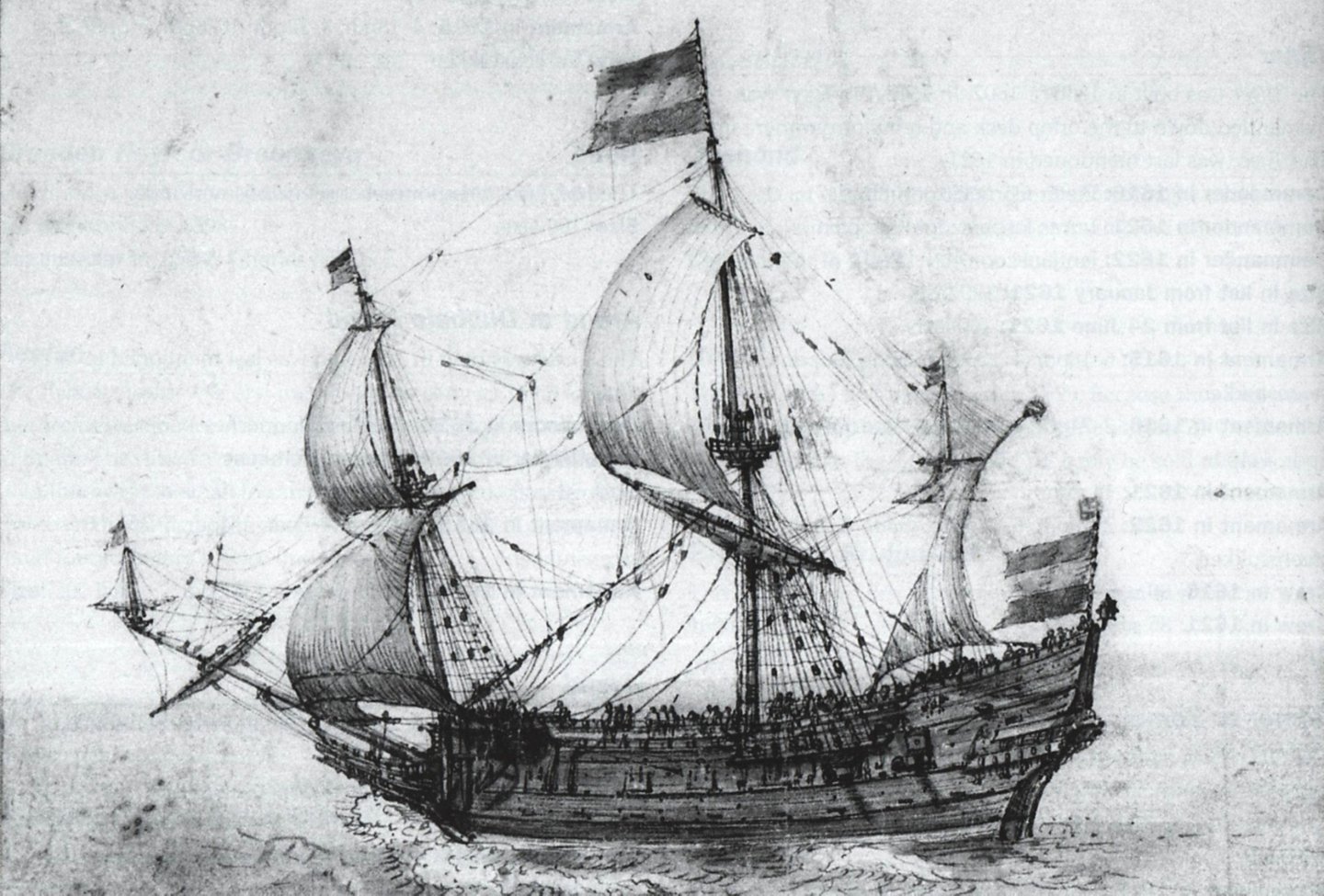

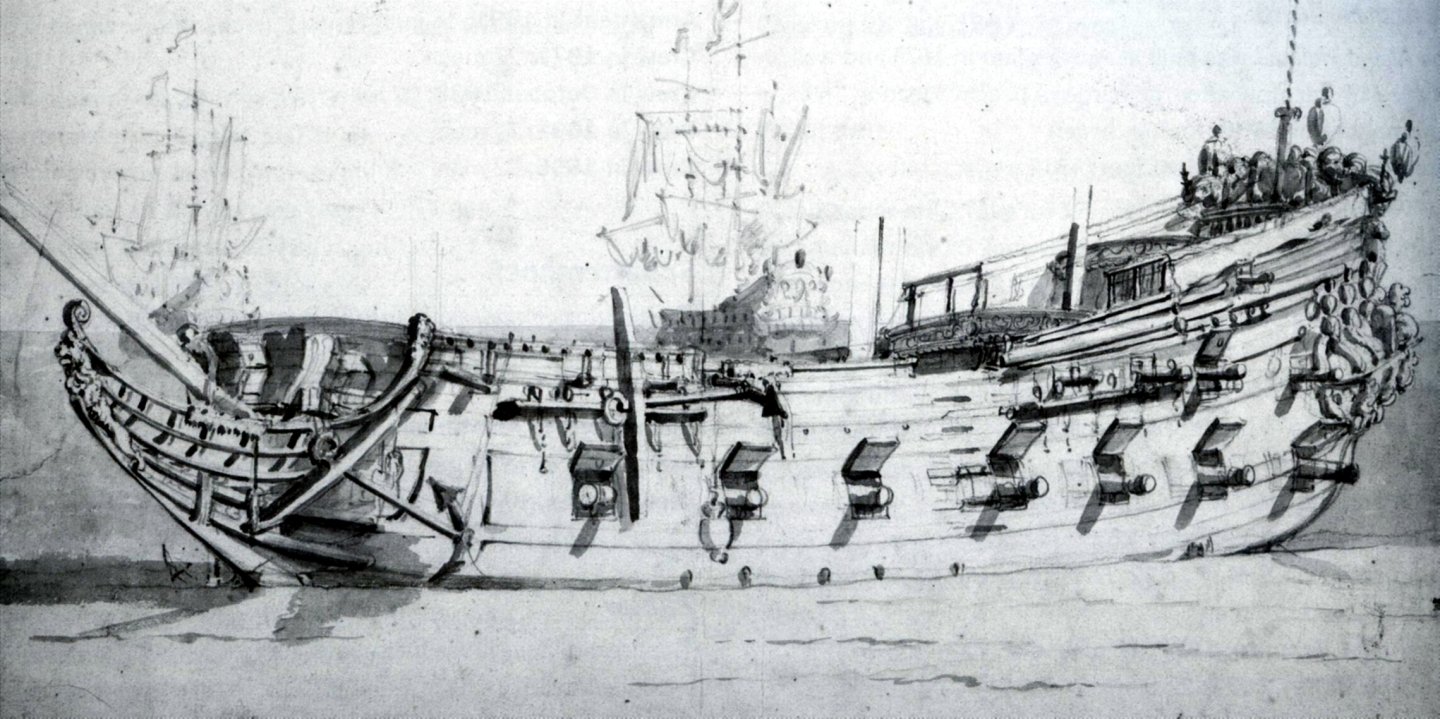

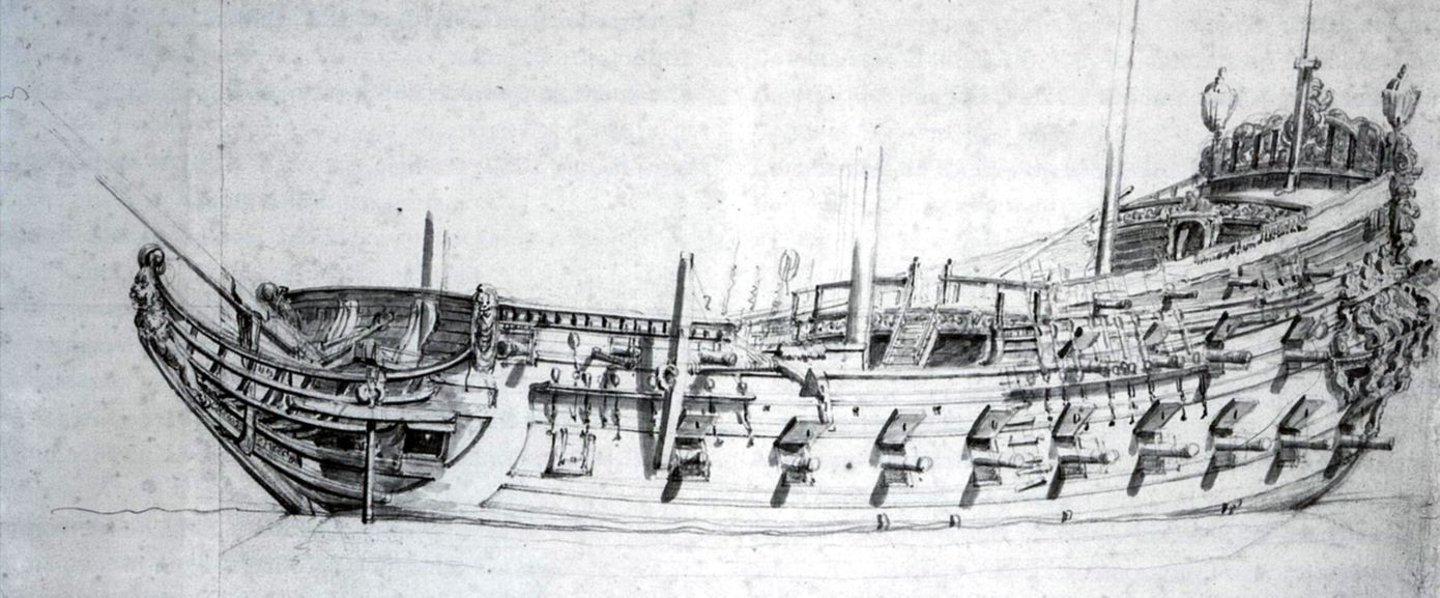

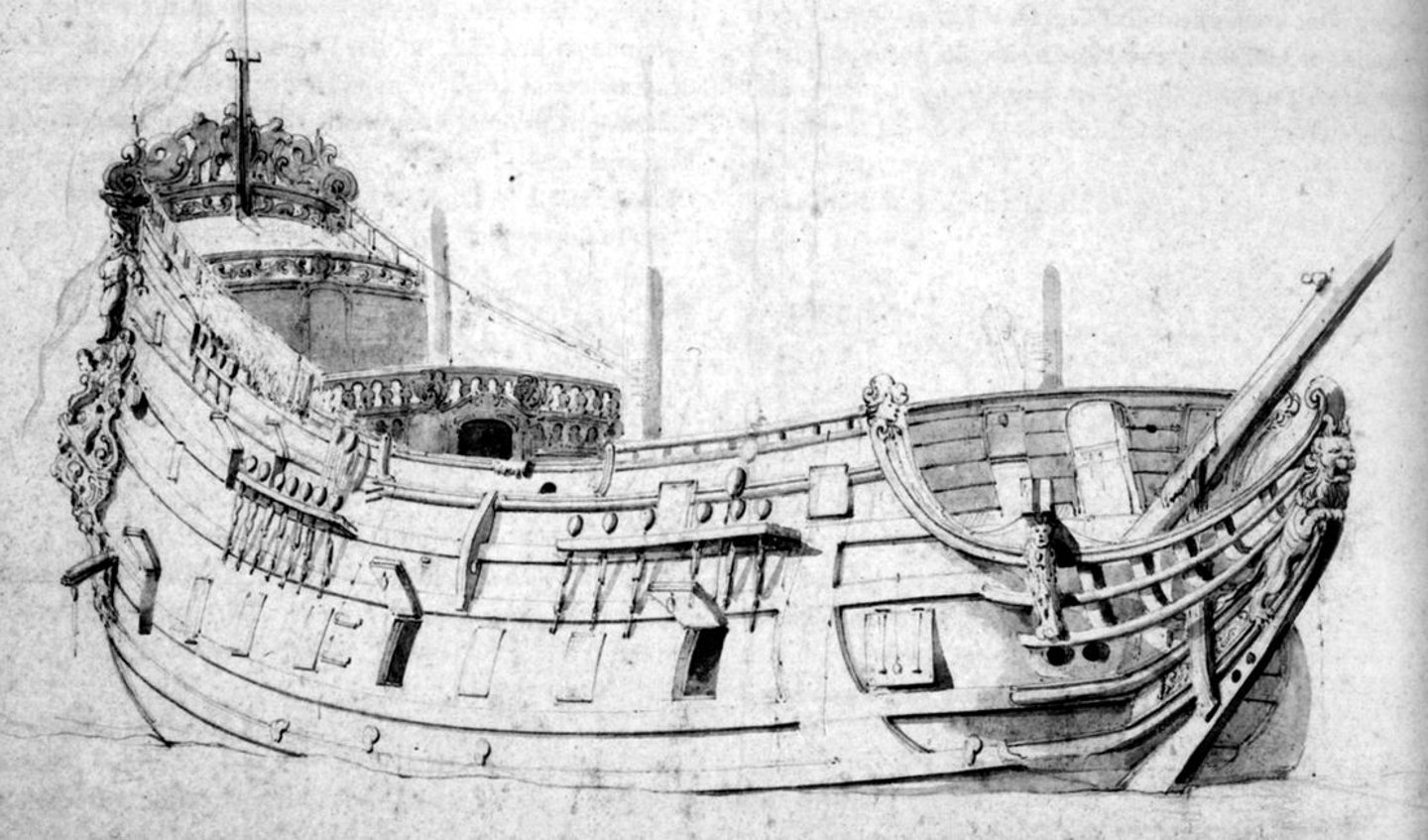

Many thanks Petr for the compliments and your very rational question as well. While it is true that many, or even most ships of the time are depicted as having a fore deck, there are still many examples of warships without one. I have selected for you a number of samples: – contracts for the building (1613) and rebuilding (1630) of the Danish warship 'Fides' (builder: Dutchman Peter Michelsen), in which all decks are listed, but the fore deck is not mentioned; – contract and draught of the Danish warship „Hummeren” (designer and builder: Scotsman David Balfour), built 1623–1625 (the run of the decks highlighted with red lines by me); Hummeren 1625 – portrait of a Dutch ship of about 1620 by Cornelis Verbeeck, which may be interpreted as having no forecastle; Dutch ship of about 1620 – case of the Dutch-built VOC ship „Prins Willem” built 1649–1650, with her fore deck removed upon pressing for naval service (it seems quite typical procedure in such circumstances); – depiction of a Dutch warship by Experiens Sillemans (1611–1653); Dutch warship of about the middle of the 17th cent. – 17th cent. model of the Swedish warship „Amarant” built 1653; Amarant 1653 – a number of van de Velde drawings of Dutch frigates of about the middle of the 17th cent. Wulpenburg 1659 Harderwijk 1659 unidentified frigate of the Amsterdam Admiralty 1665 So, given a choice - with or without a fore deck, first of all I had taken into account the extremely narrow hull of the reconstructed ship.

-

Thank you Scrubby. Yes, once the formalities are settled, which should be soon, the first model will be built in wood. But first the general concept of the ship's reconstruction, so different in some important aspects from the existing ones, has to be accepted by the investor (museum). In any case, I will try to show further progress as far as possible, be it a 3D or a wooden model.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.thumb.jpg.c6343966b029e7941df5b987d129aac6.jpg)