-

Posts

987 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Waldemar

-

... forgot to mention both realistic and attractive shapes.

- 55 replies

-

- Nordlandsbaaden

- Billing Boats

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

A lovely finish, natural, 'everlasting' materials (if properly cared for) and a visible structure. This is my favourite way 🙂.

- 55 replies

-

- Nordlandsbaaden

- Billing Boats

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

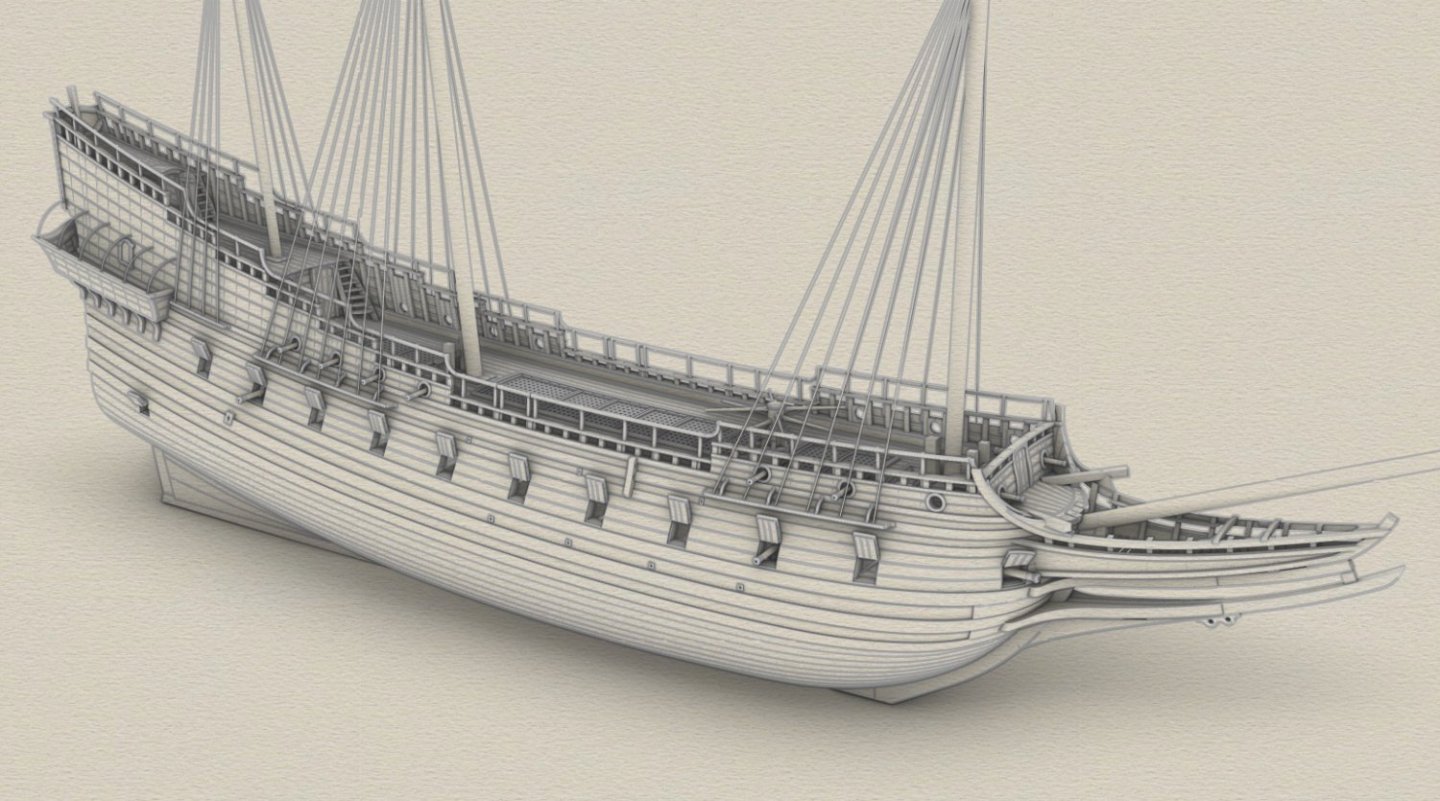

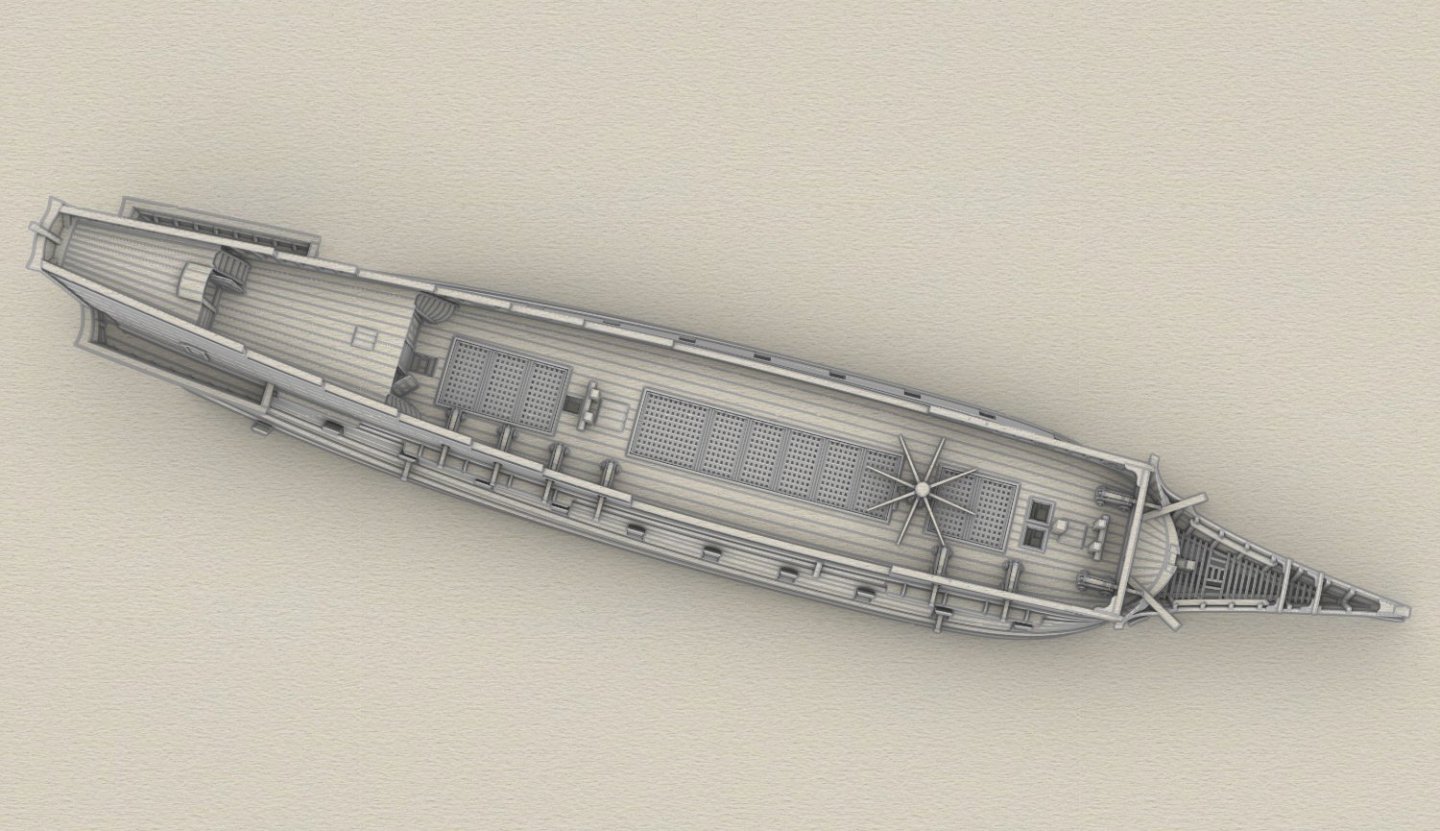

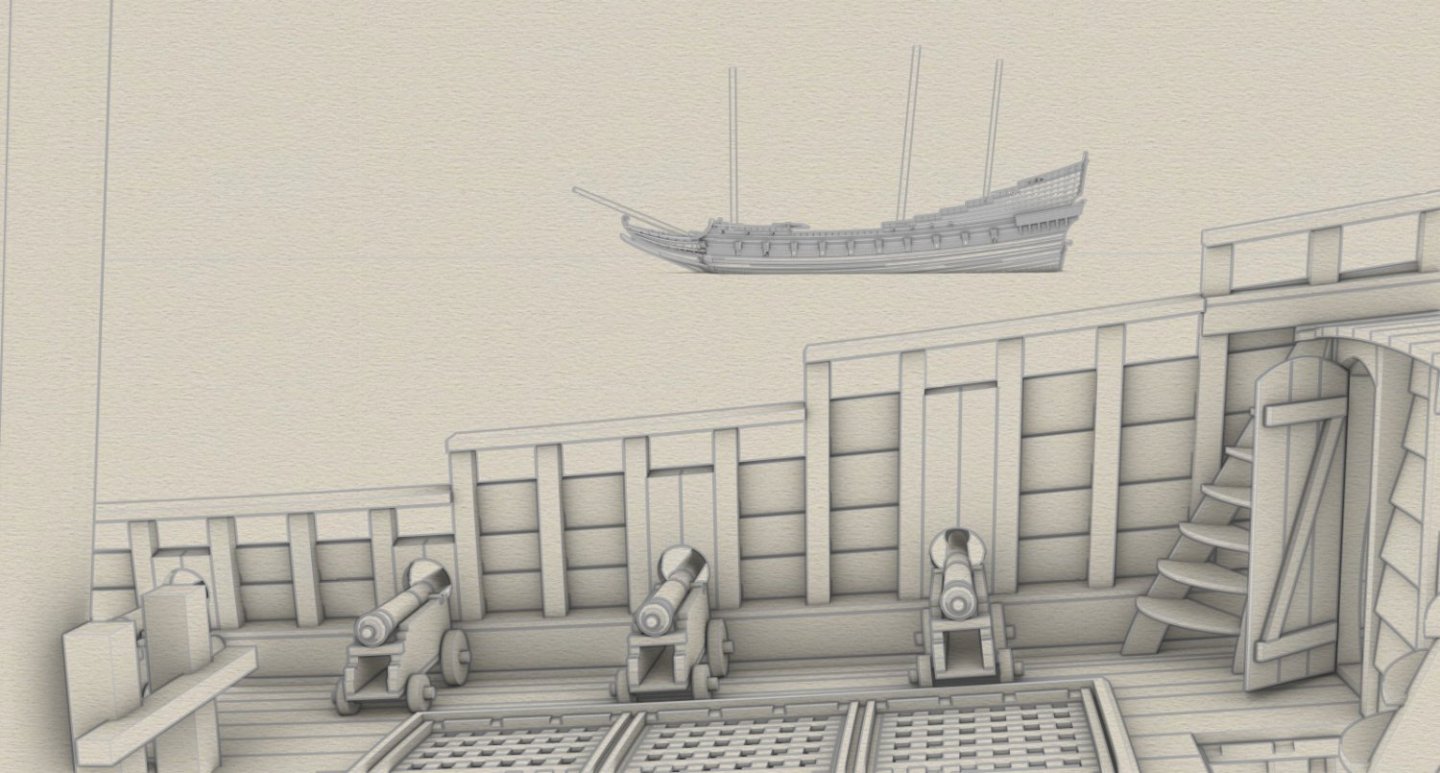

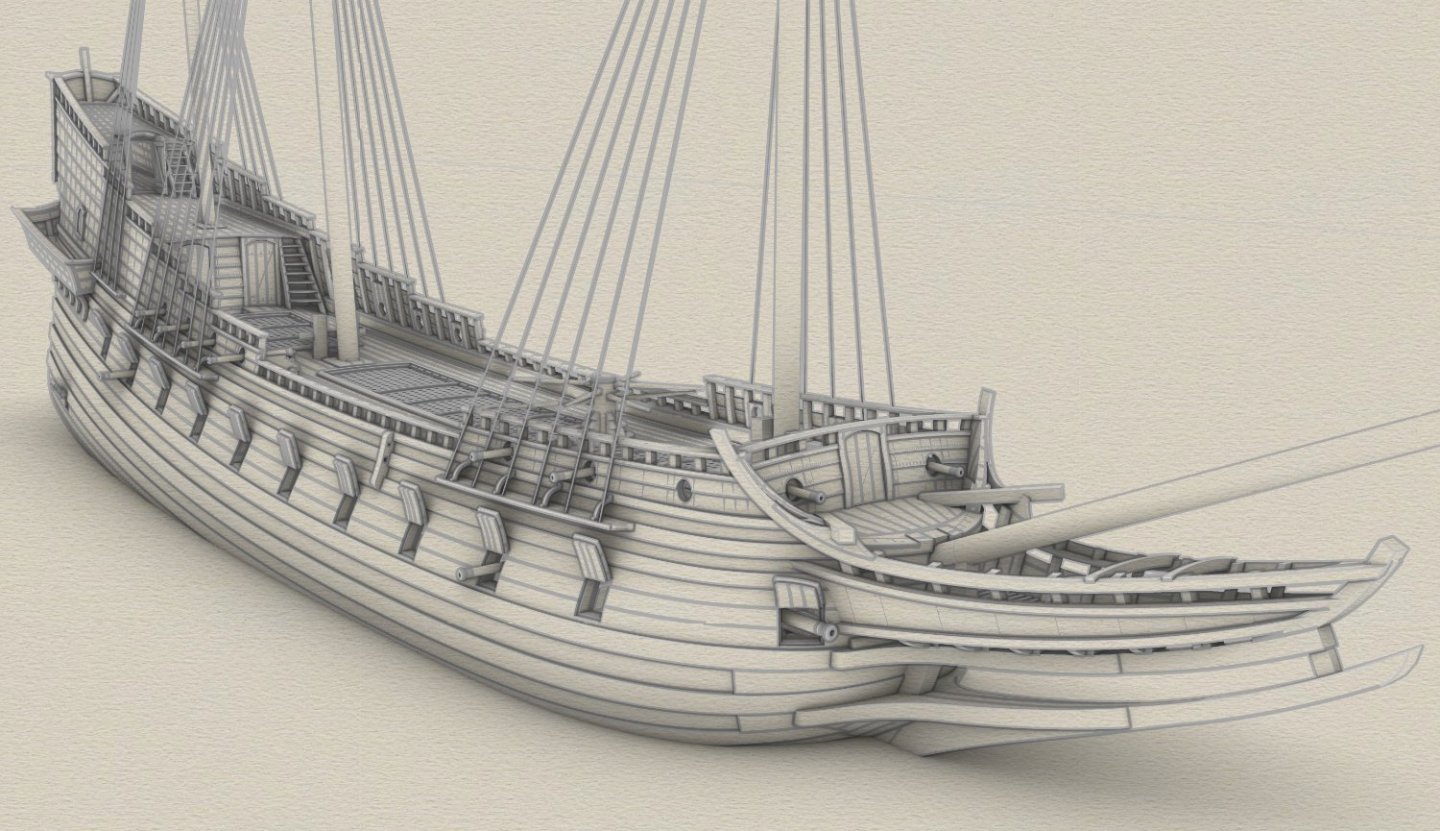

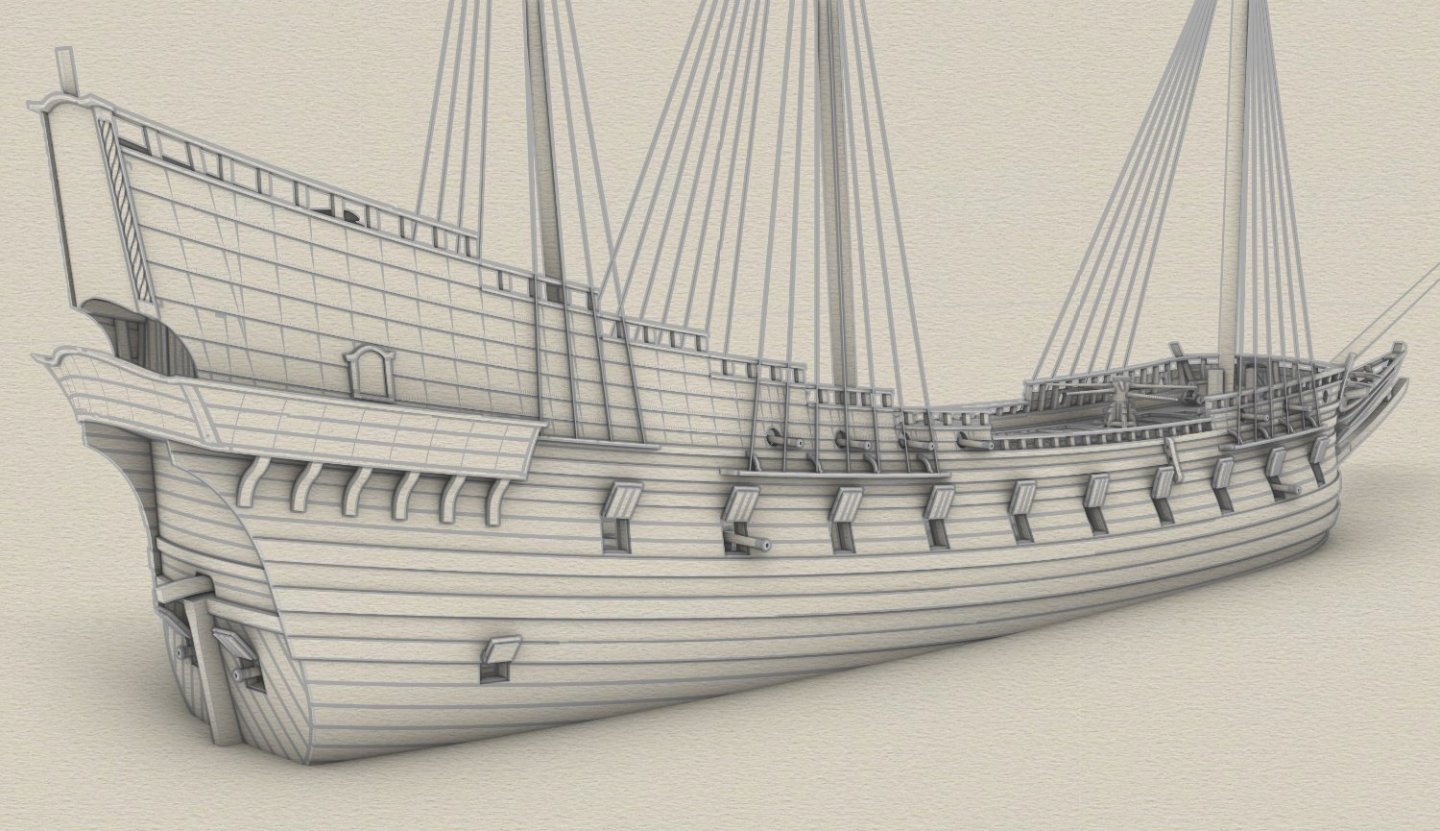

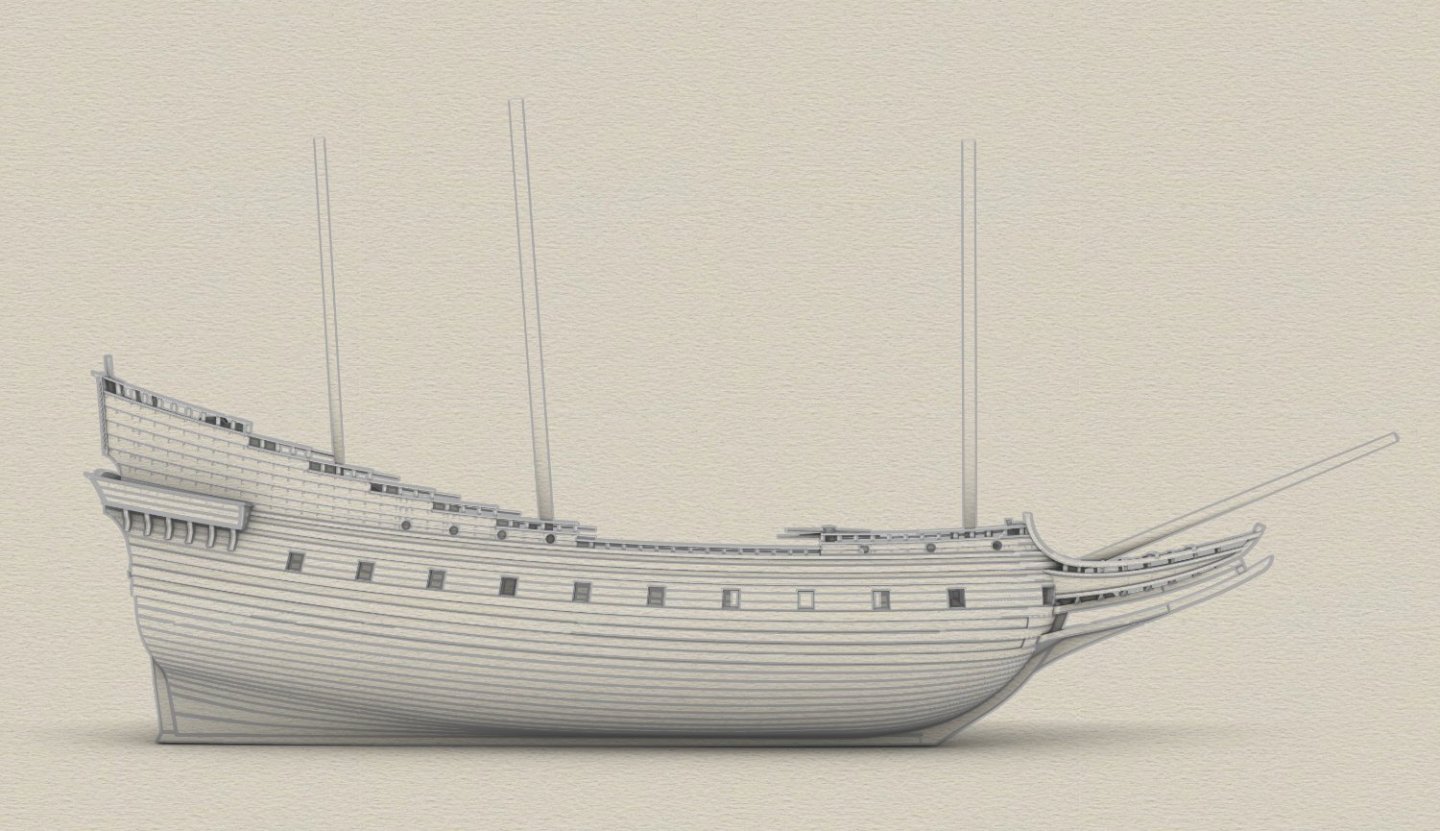

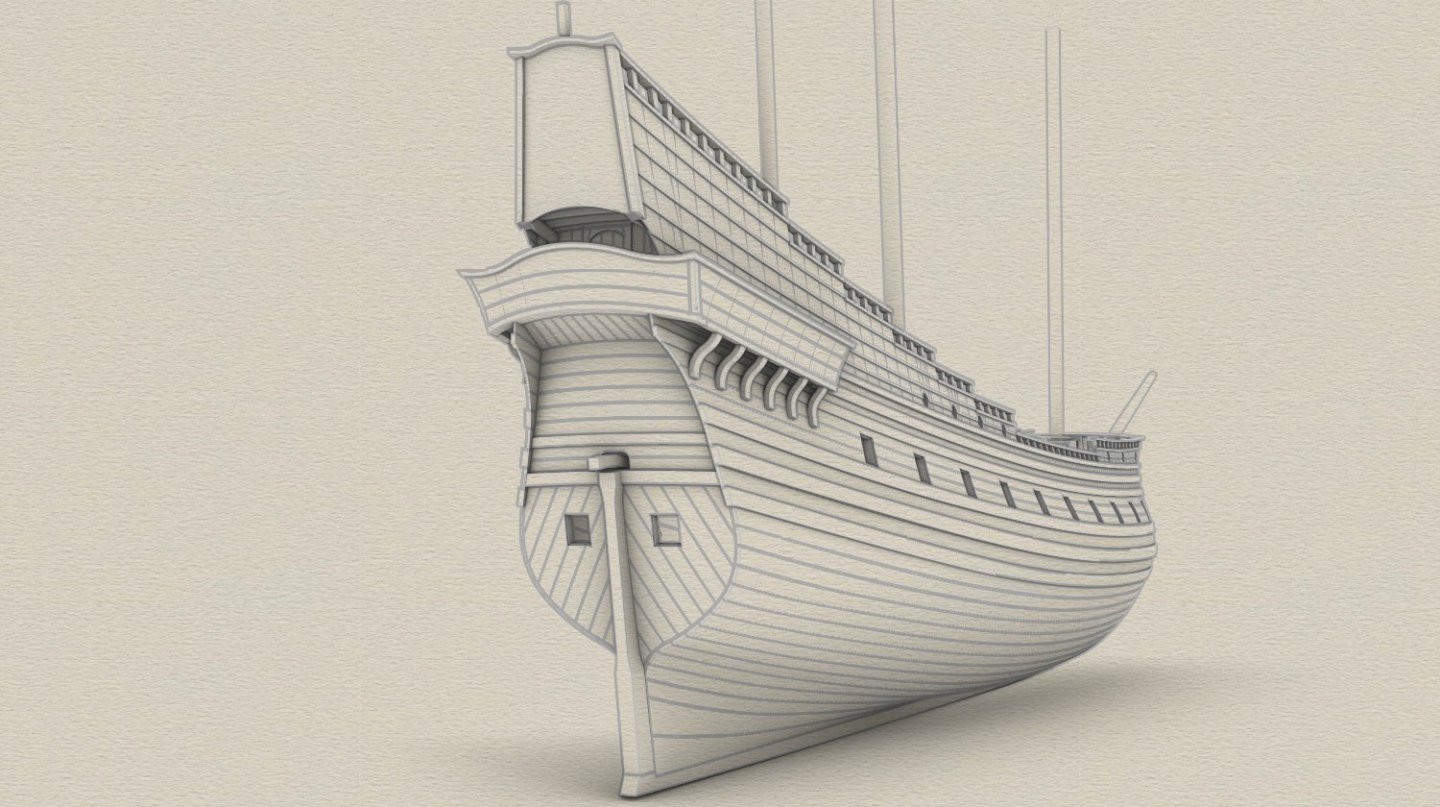

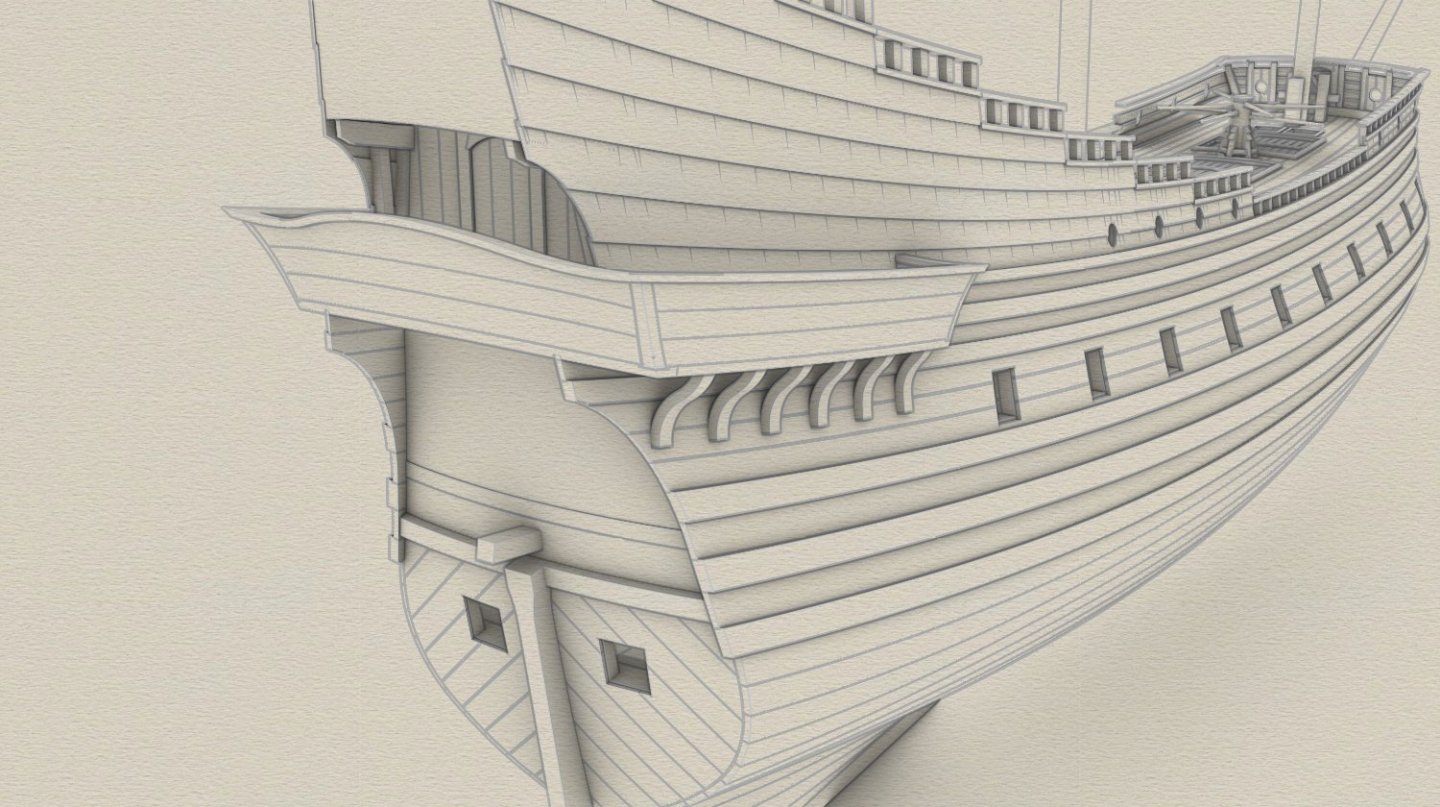

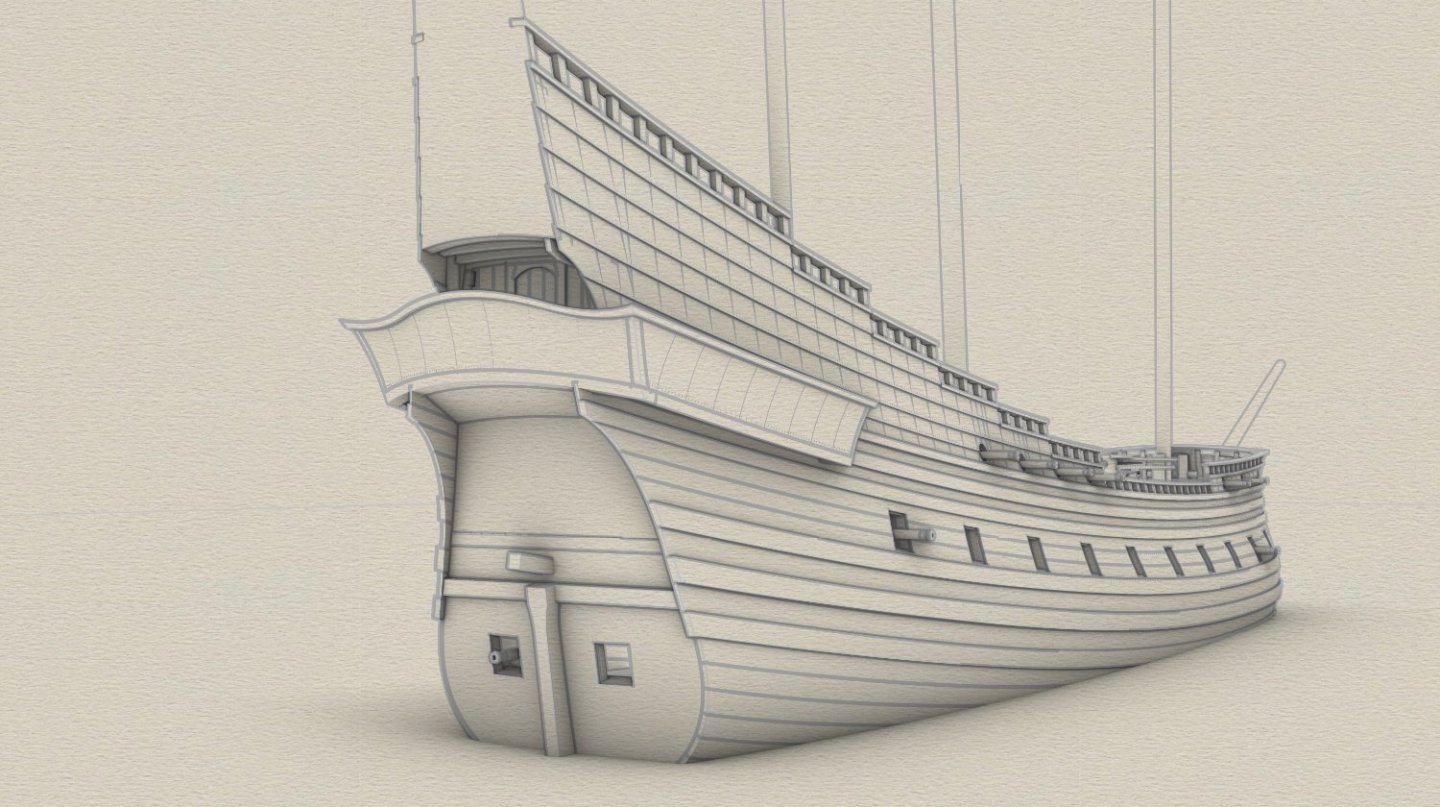

Many thanks guys for the likes and comments... In the quest for speed and weatherliness, the ship was designed with extremely narrow proportions for a warship. The length-to-width ratio is as high as 4,62:1. If highly built with extensive upperworks or multiple decks, she could have capsized, as happened to the 'Vasa' for precisely this reason. Fortunately, the king did not interfere with the ship's design in this case.

-

In those days, only a few ships could match the 'Vasa' in terms of the number of carvings, such as the Danish 'Tre Kroner', the English 'Prince' and 'Sovereign of the Seas' or the French 'La Couronne'. These were all exceptional ships built for show. All the rest, the workhorses of the fleet, were much more modest in this respect. And this ship is such a workhorse for day-to-day duties. There are quite a few shipwrecks relevant to this project. Many of them are well known, except perhaps the Swedish 'Solen', a ship that was sunk in the same battle in which the 'Saint George' participated. Lots of extremely useful material from this site. We still hope to find the remains of the "Saint George" in the river.

-

Thank you very much Scrubby. Well, yes and no. Only scanty data on the actual ship survives (but happily more on other ships of the fleet). There is, however, abundant material when it comes to background information. Archaeological, iconographic and written sources were used for this reconstruction: Venetian, Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, English, Danish and Swedish. All of these proved useful. As a result, the ship can be considered a more or less typical man-of-war of the Baltic area.

-

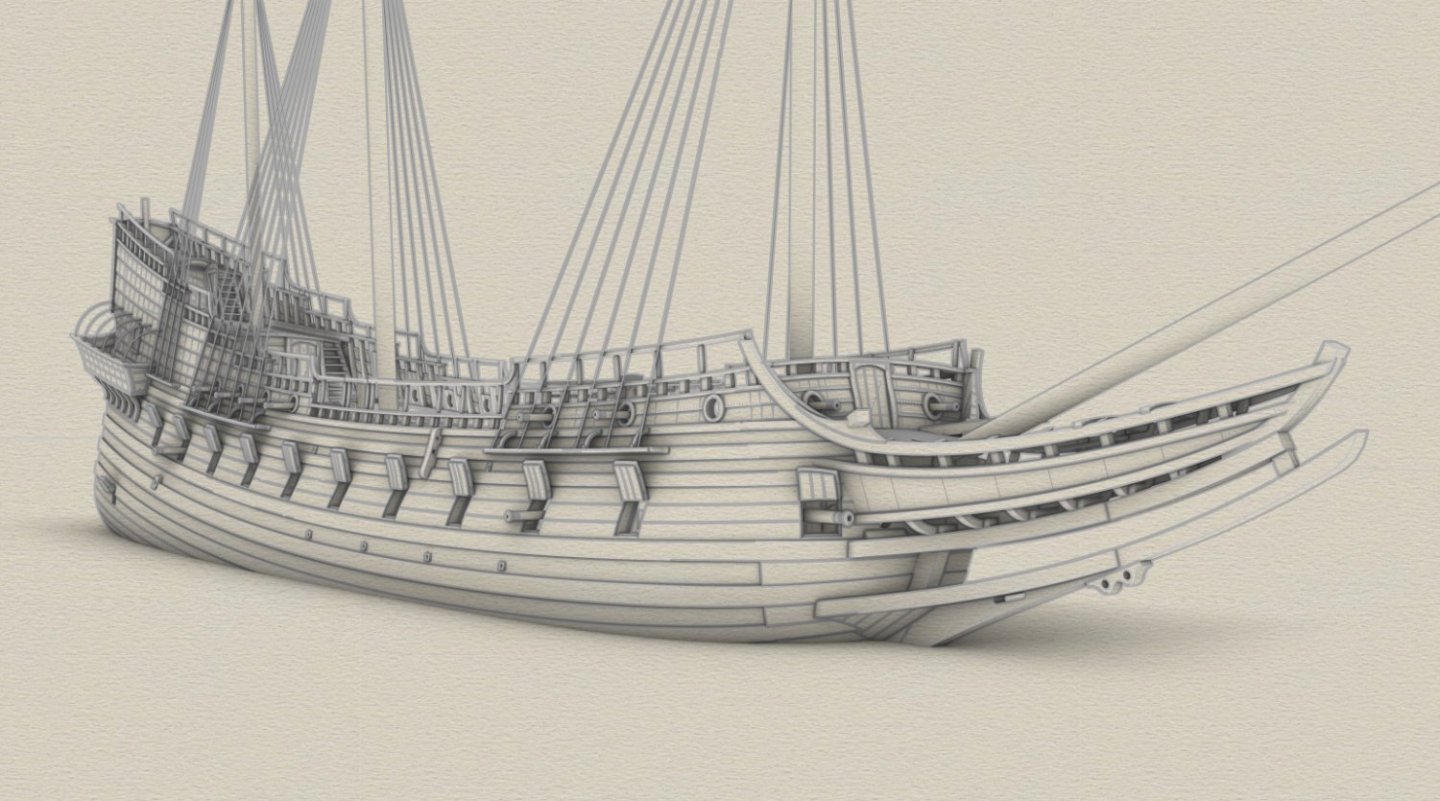

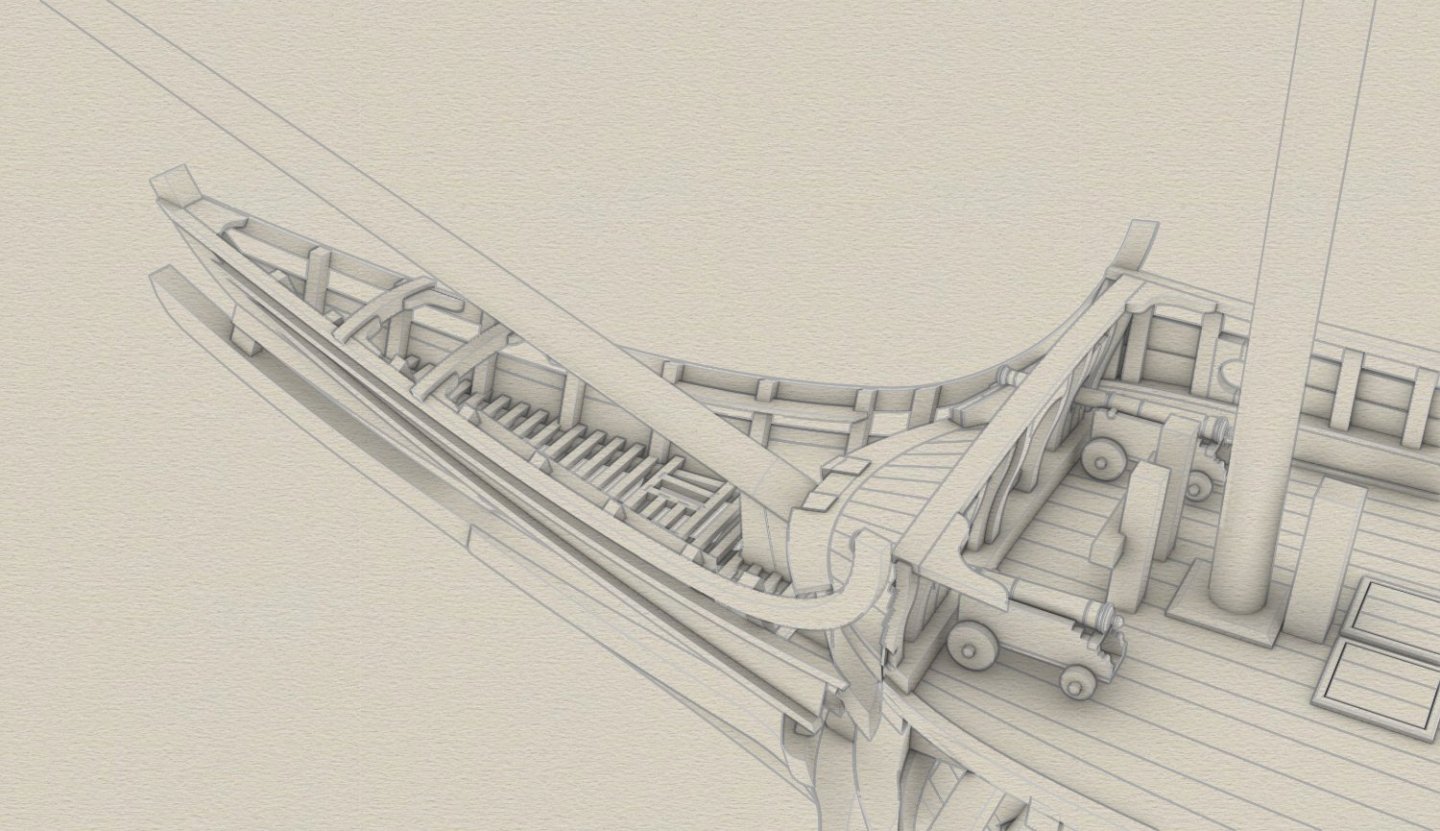

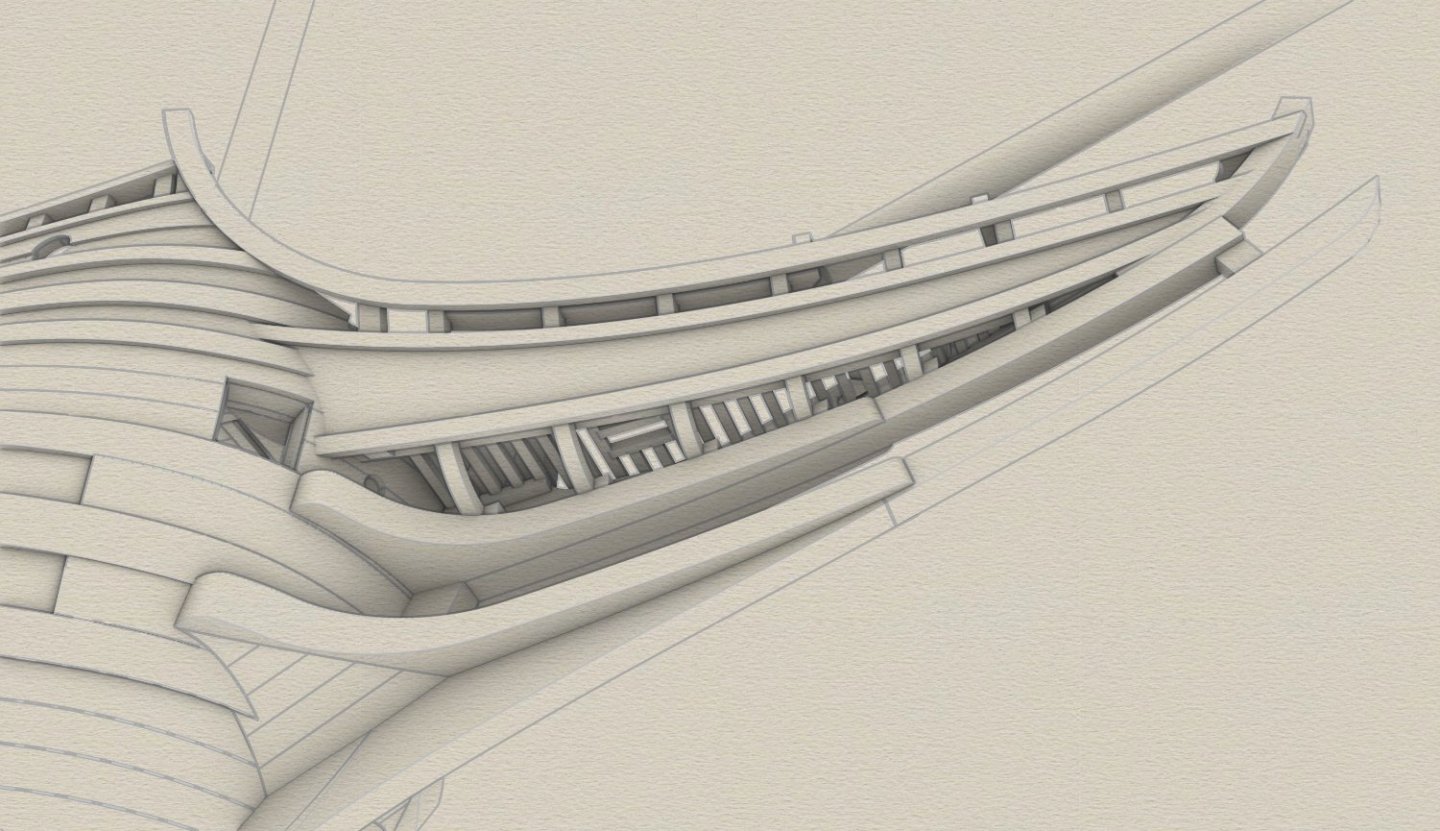

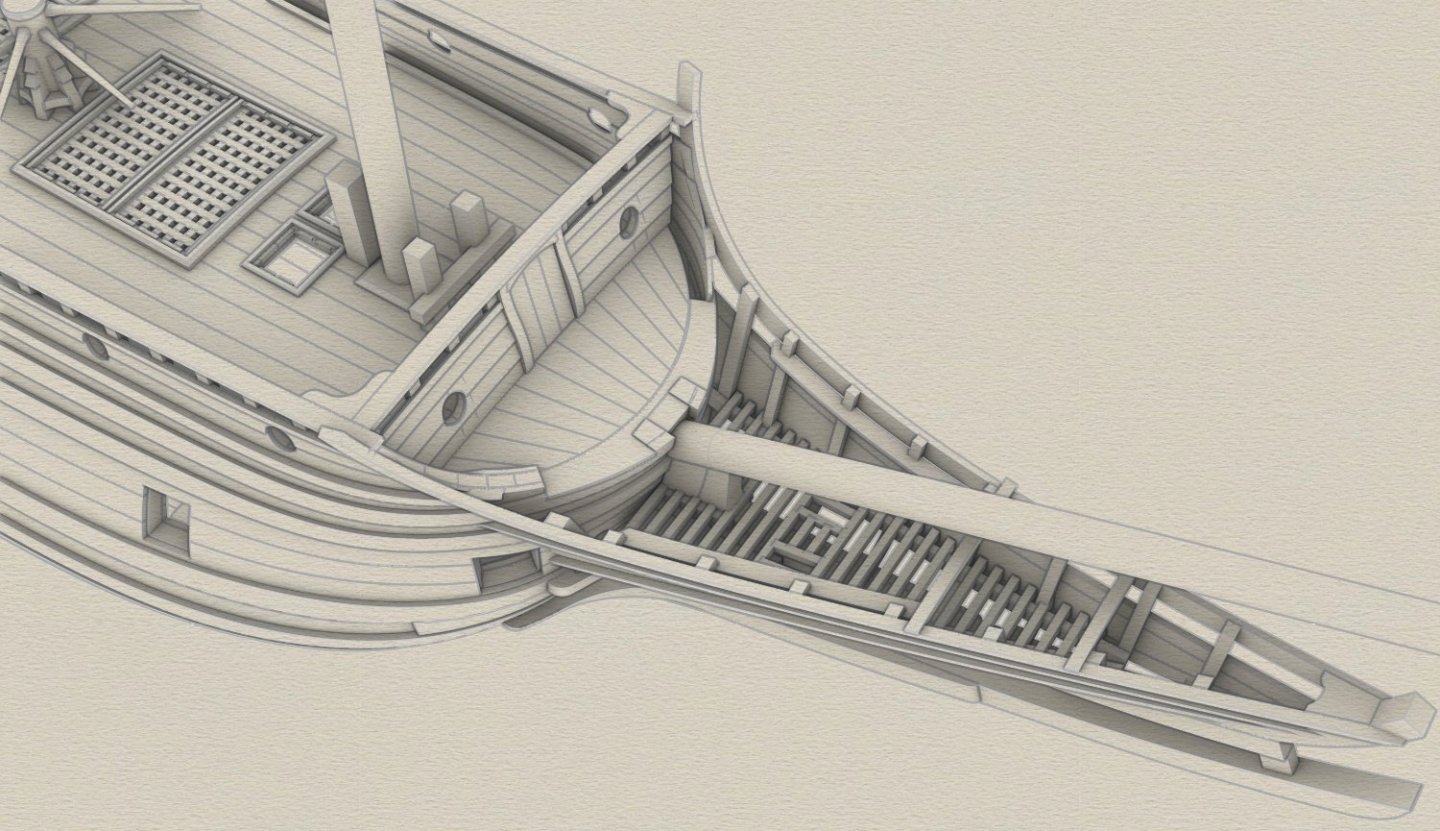

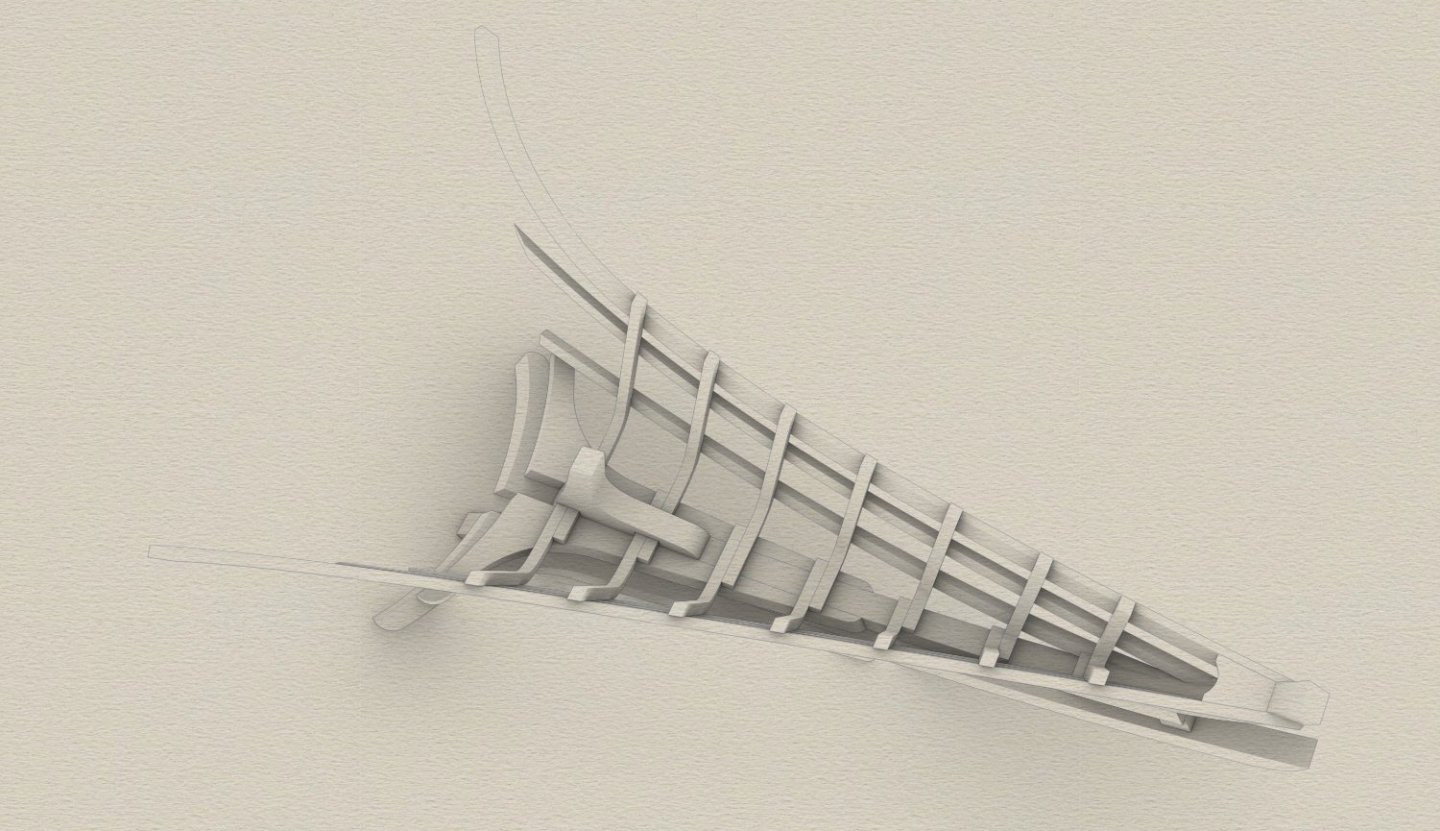

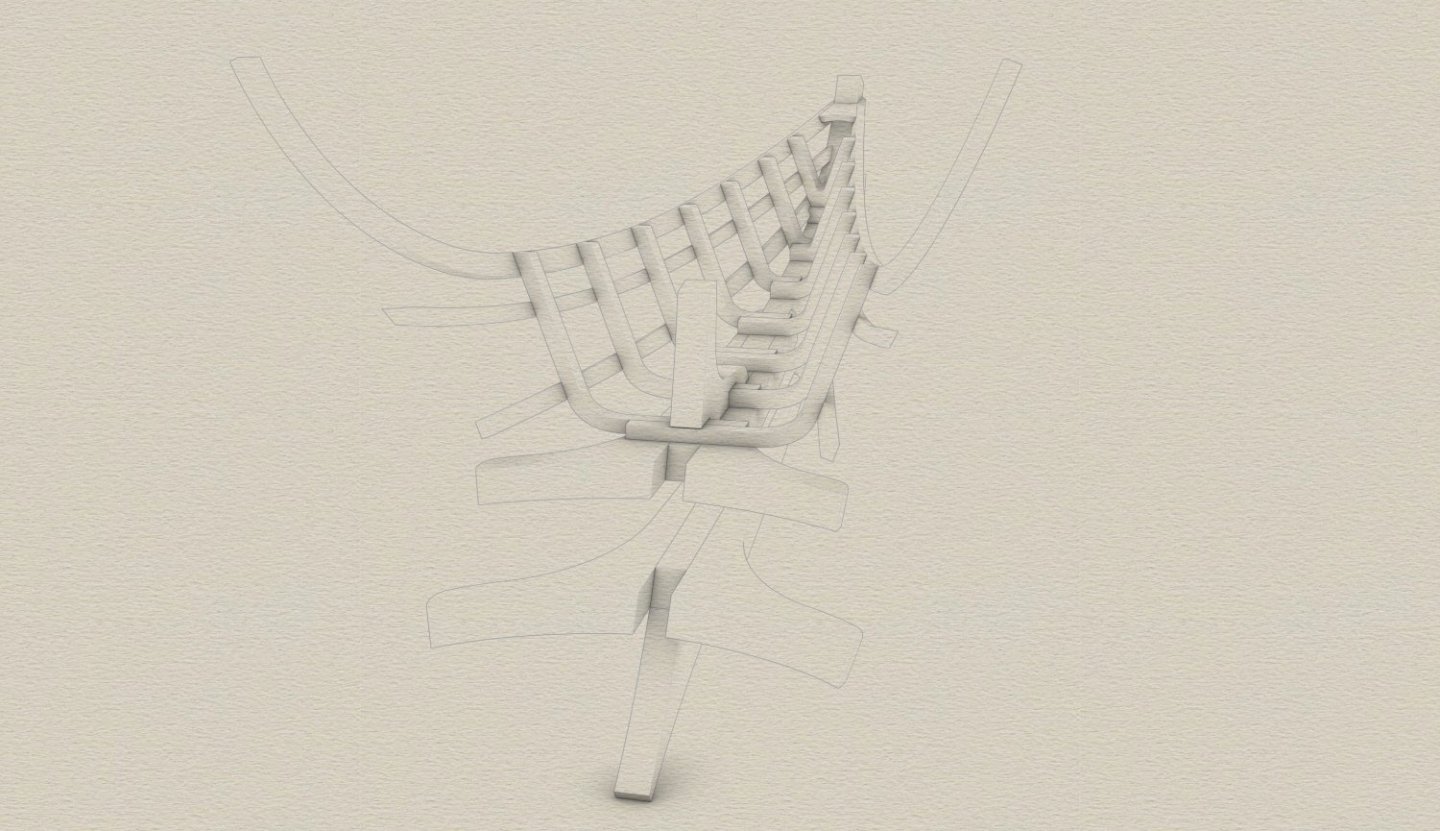

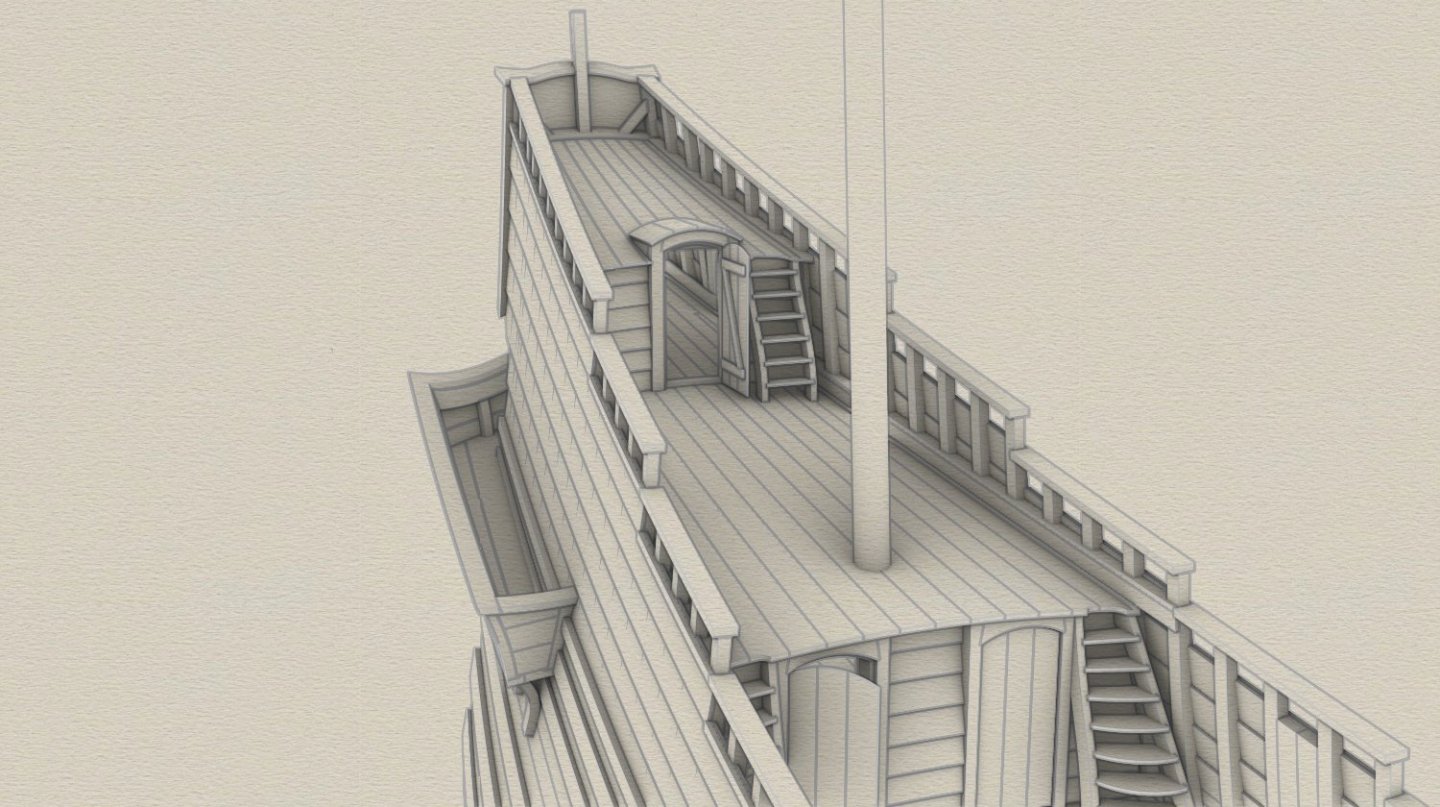

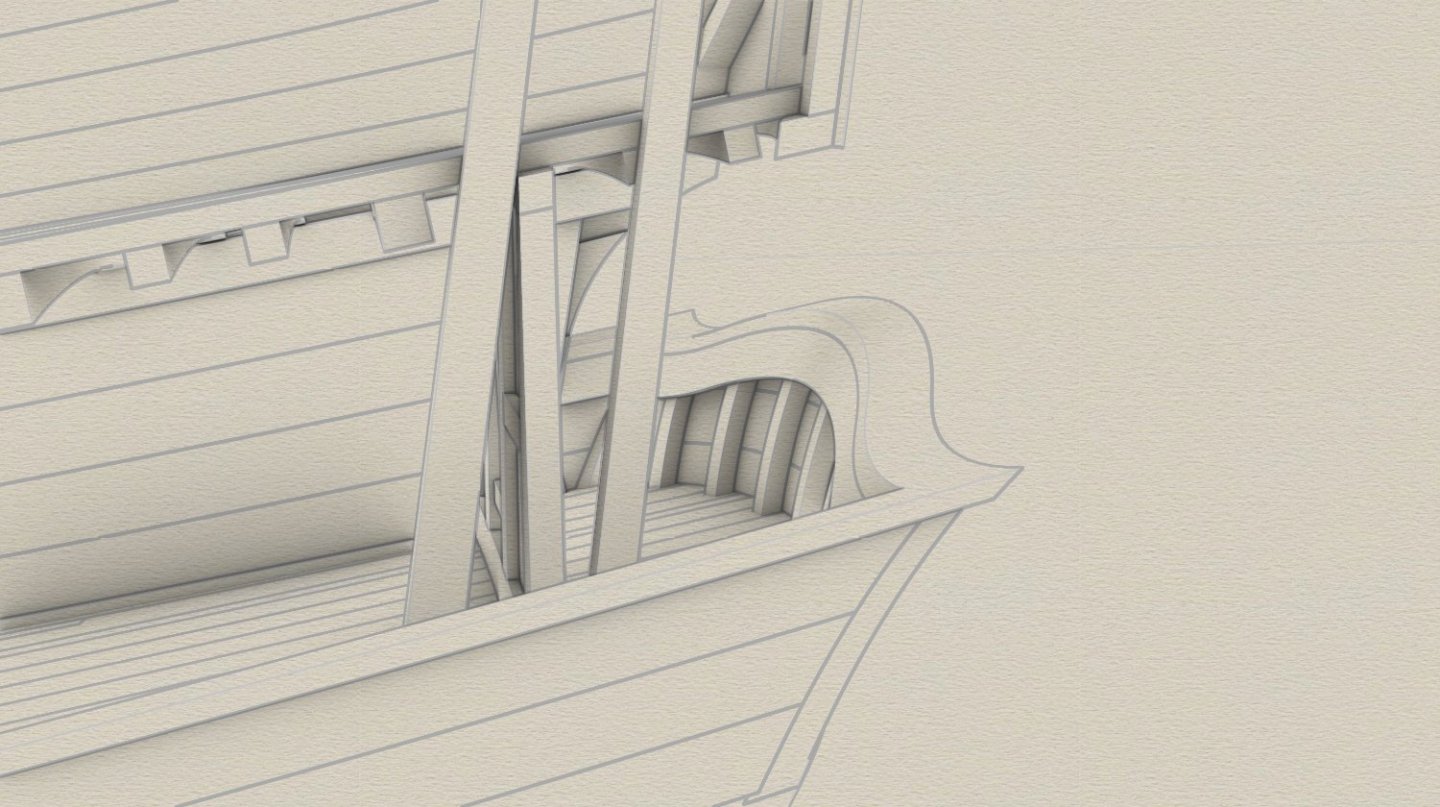

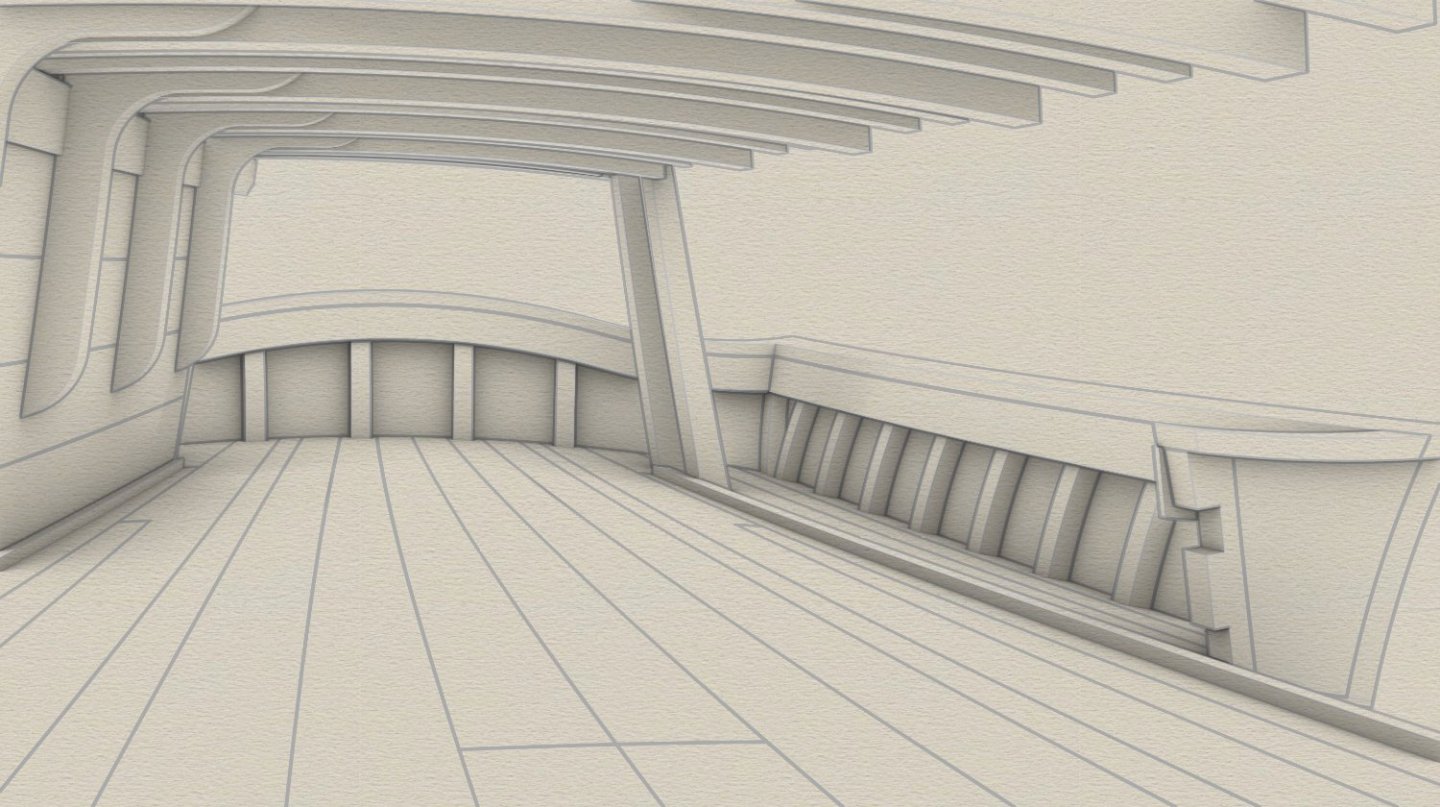

Ye dredded reer ormanents stryke yette agayn (making forum server down for two days). In the meantime... ... the final lines of the stern taking shape. I have modified the internal structure slightly (not shown here) in order to lay a row of planks under balcony lengthwise rather than across as was originally intended.

-

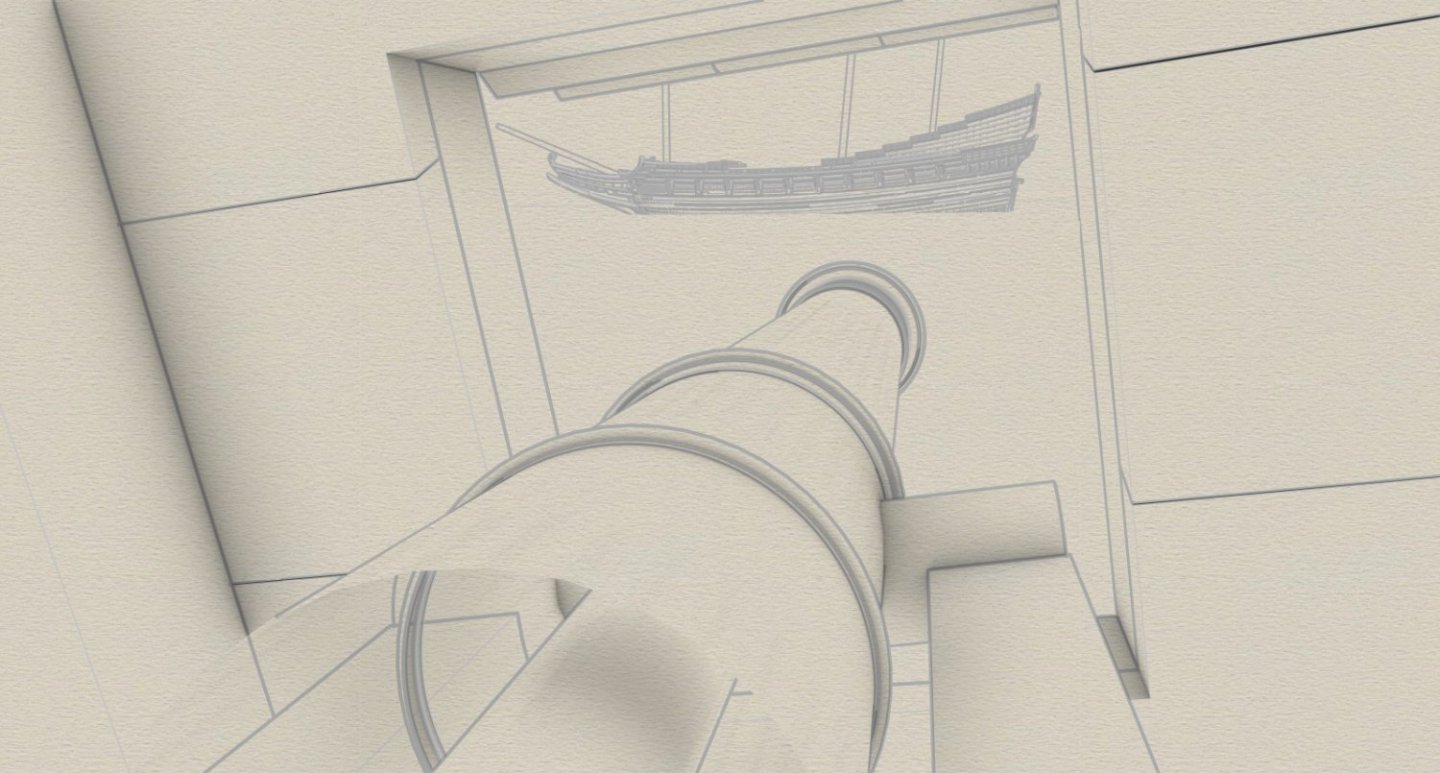

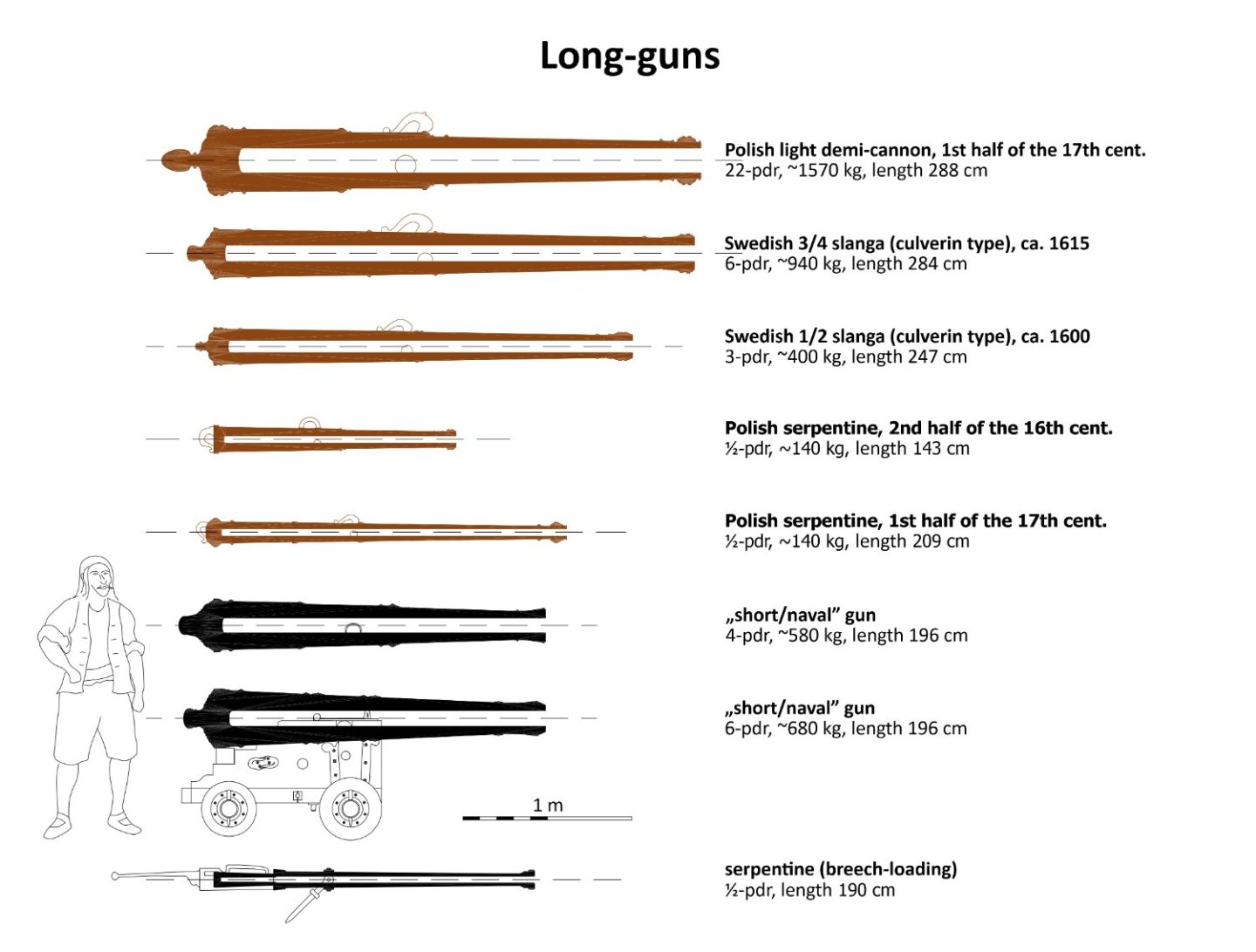

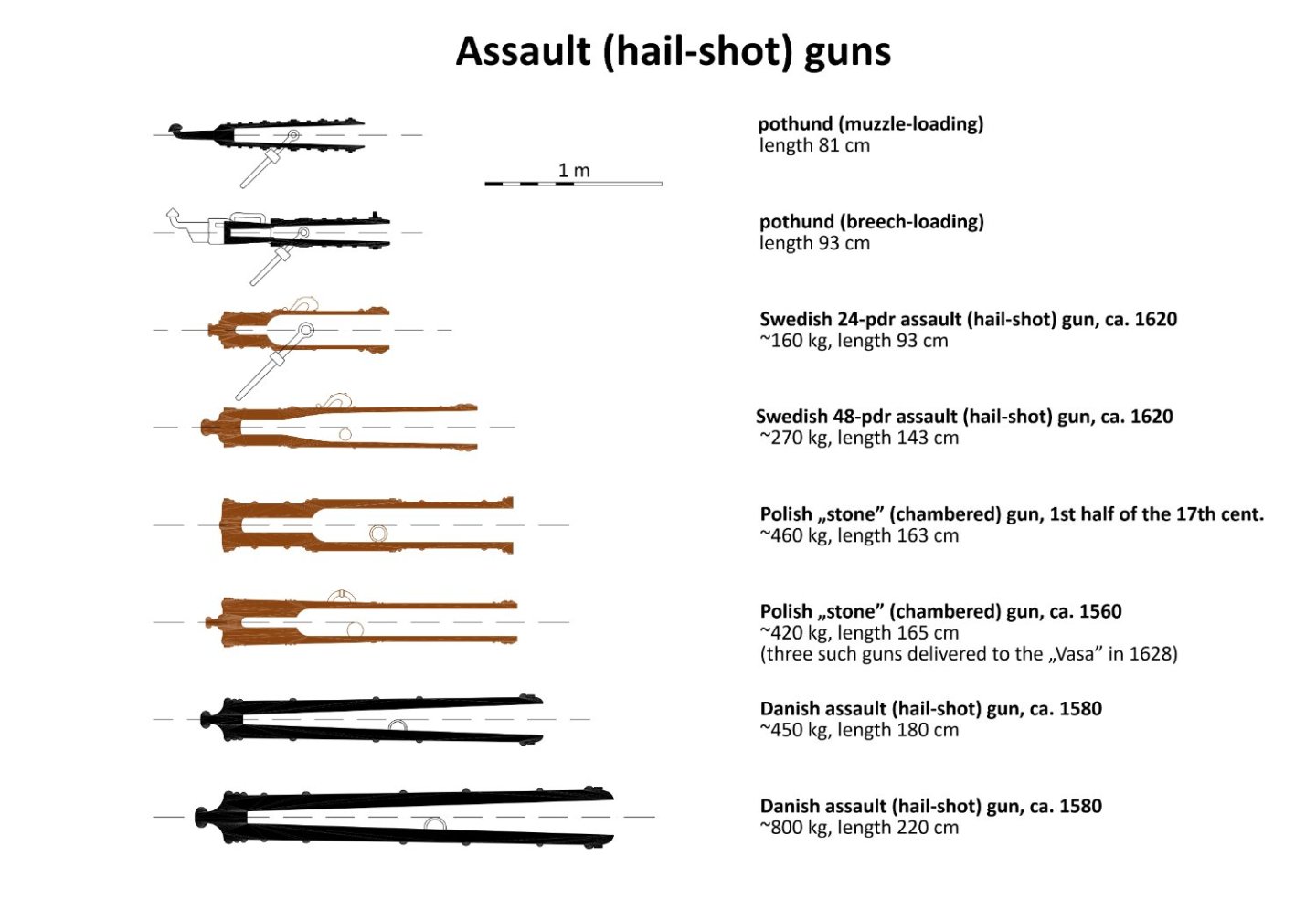

Thank you for this comment Lieste. To make the matter hopefully simpler, I have already prepared a graphic for my soon-to-be-published paper on the fleet's artillery. Shown here are the most typical samples mentioned in both extant inventories. In black are cast- and wrought-iron guns, and in bronze are, of course, bronze guns 🙂. All drawings are based on real surviving artillery pieces. Most interesting are surely assault/hail-shot type guns. They could be large or small, carriage or swivel, bronze or iron (be it cast- or wrought-iron), chambered or not, muzzle- or breech-loaded, conical or cylindrical bored. Larger specimens would be referred to in English as cannon-perriers. As an aside, four large (meaning carriage) Polish bronze assault/hail-shot guns such as depicted below, called at the time „stone guns”, because they used before to shoot stone missiles, were issued to the 'Vasa' in 1628.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.thumb.jpg.c6343966b029e7941df5b987d129aac6.jpg)