Bob Cleek

Members-

Posts

3,374 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Bob Cleek

-

Most pantographs available today are really little more than toys. The really good ones used back when are very complex pieces of precision equipment and rather heavy. If you can find a complete one, it will likely be quite expensive if the seller knows the collector's market. In practice, the pros used the pantograph to simply mark points from the original to the copy and then "connected the dots." That's much easier than trying to trace lines with the instrument. Using this method, acceptable results can be realized, even with the cheap ones. In most instances, however, scaling is today far easier with a copy machine. If you find one like this at a garage sale, grab it! https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_904629

-

So you guys are the ones responsible for the disappearance of all the antique boxwood rules and scales! Time was, one could scrounge around and amass a collection of traditional boxwood scales and a nice classic folding carpenter's rule without a lot of trouble. Then they started disappearing. I recalled someone said people were buying them because they wanted the boxwood they were made of. I was skeptical, but I'm not skeptical any longer. Realize that the boxwood rules and scales you're cutting up for modeling stock may well be worth a lot more than you think. Not so much plain old "rulers," but be aware of what you've got in your stash. Leave some for those of us who have a use for them. https://garrettwade.com/product/antique-architects-folding-rule https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_904792 https://www.antiquesboutique.com/antique-barometers-instruments/set-of-architect-s-scale-rules/itm30452#.YGPHTVVKgdU

-

A couple of observations: Pine tar is a very dark brown, close to black. "Coca Cola color" is really the best description I've heard. The degree of brown depends upon how much tar is put on the cordage. Standing rigging was heavily tarred (as much as it would soak up) to preserve it and so was so brown it was nearly black. At scale viewing distances, standing rigging would appear black. A bit of thinned pine tar was added to the fibers when rope was laid up to preserve it. This gave new running rigging, which wasn't tarred after manufacture, it's golden brown color, which weathered to gray in the sun after a time. Cordage on sailing ships was traditionally made of hemp fiber, not sisal ("Manila") fibers. Hemp fibers and linen (flax) fibers are close to indistinguishable in their appearance and strength properties, although hemp has somewhat less stretch, is a bit stronger, and weathers better. Hemp was always more expensive than linen and linen more expensive than sisal. Hemp has a softer "hand" than linen or sisal. As the governments around the world become more "enlightened," commercial hemp production is rebounding from near extinction. Hemp fabric and hemp thread, and rope, are again currently being produced and, it seems, becoming more available every day. A bit of googling with produce lots of sources for hemp thread. For ship modeling purposes, I presume hemp thread will be every bit as suitable as linen thread, which has generally gone out of production and is hard to source. I presume hemp would offer the same "archival" advantages of linen. If one wanted to get really authentic, they couldn't go far wrong using real tarred hemp thread for laying up scale rope, although I expect waiting for the tar to dry would be something of a pain and since pine tar is nasty, sticky stuff, dyeing it in some other way would probably be preferable. That said, the wonderful aroma of pine tar would improve the overall effect of any model and a dab behind the modeler's ears might make the modeler more attractive as well. (Disclaimer: I haven't tried laying up scale rope from hemp thread as yet, nor have I researched all the possible sources and sizes of hemp thread available. A quick review indicates that there is a range of quality and sizes may be limited compared to the general thread selection of other types.) Pine tar is readily available. It can often be purchased in small amounts in American sporting goods stores, which sell it for application to baseball bat handles. It's stickiness improves the batter's grip. Pine tar is also a staple in "tack shops" which sell equestrian gear. It is used to dress horses' hooves. It keeps them from splitting. It's also an old-time antiseptic for farm animals, particularly chickens. It's smeared on chickens that have been pecked by other chickens and not only is antiseptic for the "peckee," but also unpleasant for the "pecker." Pine tar is also used in the manufacture of certain soaps and as a treatment for human skin conditions, but isn't approved as such and for that use has been deemed carcinogenic. Pine tar differs a bit, particularly in aroma, due to the methods of its extraction and processing. If anybody wants "real" pine tar as was traditionally used in the maritime trades, sometimes referred to as "Stockholm tar," it is available from at least three sources in the US that I'm aware of. George Kirby Jr. Paint Co. has been selling it from their shop in New Bedford, Mass. since the days of the whaling industry. George ("the fourth") Kirby also sells the best line of traditional oil based marine paint available today, together with all other traditional marine coatings. He is available by phone and will mix up anything you want upon request. https://kirbypaint.com/ George Kirby Jr. Paint Co., New Bedford, Mass. ("Since 1846") : https://kirbypaint.com/products/pine-tar American Rope and Tar : http://www.tarsmell.com/tar.html Fisheries Supply: https://www.fisheriessupply.com/marshall-s-cove-marine-paint-pine-tar

-

Table Saws Once Again

Bob Cleek replied to Ron Burns's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Call up Jim and have him add the cross-cut sled to your order. You know you want it. You will likely save considerably on shipping if it all goes out in one box. If She Who Must Be Obeyed objects, just tell her that you saved a bundle on shipping ordering the sled too. She'll see the logic of that right away. I'll bet she uses the same approach on you all the time if she's like most! I'd also suggest you spring for the taper jig. It doesn't cost much and is a thing of beauty to behold. It's handy for tapering, too. -

Could not agree more - well said! I agree as well. In fact, with a USS Constitution or HMS Victory kit, there is a high probability that it’s never going to get finished before you croak! (I'd love to see accurate statistics on numbers sold and numbers finished!) However, if someone is assembling a USS Constitution or HMS Victory kit and wants to have it last to perhaps become a family heirloom, and they ask which materials should be used in pursuit of that accomplishment, they deserve an honest answer, not the insinuation that their efforts won't ever be worth that. Just look at all the kit builders who ask questions concerning the often-questionable historical accuracy of their kits. They, too, deserve an honest answer, not the response that it's just a kit that nobody other than themselves will ever care about! I think the best posture to take in all things is to promote "best practices" and if one falls short, that's their choice and if they have fun notwithstanding, so much the better! (This post is written by a guy who when he was a kid used to blow up his old finished models with firecrackers and cherry bombs. The "Joy of Modeling" is in the eye of the beholder. )

-

As Roger explained, it depends on what the cut piece is going to be used for. Grain orientation is a factor in strength and ease of bending, as well as in the piece's ability to hold fastenings and resist splitting. Most good basic books on woodworking will treat the subject of milling and grain orientaton in their early chapters.

-

I think we have to presume that the author of those specifications took it as a given that such a model would be properly cared for and kept properly cased. The hundred year span is certainly arbitrary, as well. It's my understanding that a hundred years is the definition of an "antique" in the trade, anything less being classified as "vintage."

-

Indeed, the exchange of opinions is often enlightening. It gives us the opportunity to see things from the perspectives of others. Opinions, however, are not facts and therein lies the rub. One may have an opinion about anything that is open to dispute or, as is said, "is a matter of opinion about which reasonable minds may differ." We are all entitled to our own opinions, but not to our own facts. What is "true" isn't something that's a matter of opinion. One cannot have an opinion about whether it is raining or not at a given time and place. It's either raining or it's not. They can have an opinion about whether it is going to rain tomorrow, but even that opinion can be negated by a weather satellite photo that shows there's no possibility that it can rain tomorrow. Predicting the weather used to be a more a matter of opinion than not, but science has done a good job of narrowing that window of "opinion" in the modern age. More commonly, opinions are expressions of personal preference. One can be of the opinion that broccoli tastes awful and that is neither "true" nor "false." It's just a subjective expression of personal taste. One can say subjectively, "Broccoli tastes awful to me," but they can't say it's objectively true that it tastes awful to everyone else. In the same way, one can have an opinion of the best way to do something, but their "right to their own opinion" goes out the window when it is certain that their "best way" is simply never going to work. Here is where inexperienced people often get into trouble weighing in on the internet about their "opinion" on political issues when they lack the information necessary to form an informed opinion or are relying on false information in the first place, and, in most instances, they then fall back on the retort that they "have a right to their own opinion." Opinions are subjective. Truth is objective. So, no, I don't think that what is "right" can be different things for different people when the "right" is an objective absolute. like whether or not a material is insufficient for use in an engineering application. An engineer can say with certainty and not as a matter of opinion whether a bridge will carry the weight of a railroad train. We may call that an "expert opinion," but it's really just a matter of scientific fact unless the outcome is just too close to call. Reality determines what is right. Science determines what is reality. On matters of opinion, however, there is no absolute "right." There may be any number of "rights" and any number of "wrongs." So, for example, if one posits the premise that a properly built ship model should last for a hundred years, and then asks what materials should not be used in a properly built ship model, we can see that there are "rights" that are "right" for everybody, like the fact that cheap acidic papers cannot be expected not to show the effects of deterioration for a hundred years or that we can't say for sure whether CA adhesives or acrylic paints will last a hundred years simply because they haven't been around for a hundred years. On the other hand, whether one should not worry themselves about their model lasting a hundred years because they aren't going to live that long is irrelevant to the discussion because the basic premise is that a well built ship model should last for a hundred years.

-

As I recall, the famed miniature ship modeler Lloyd McCaffery, uses wire on all of his amazing miniature models. As I recall, he discusses his techniques for that in his book, Ships in Miniature. https://www.amazon.com/SHIPS-MINIATURE-Classic-Manual-Modelmakers/dp/0851774857 Indeed, the synthetic thread, particularly the earlier stuff, isn't anywhere as long-lasting as the linen thread that used to be available is. Fear not, though. There may be a solution at hand. While the linen thread manufacturers have left the field, there's a growing market for and production of hemp thread happening right now. For all intents and purposes, linen and hemp are virtually identical, save that hemp tends to curl counterclockwise and linen clockwise (or is it the other way around?) Sourcing some and seeing how it lays up as rope is on my "to-do" list one of these days.

-

I'm more bothered about what they are going to do with my models after I'm gone than I am about what they are going to do with my stinking carcass. Of course, enjoying oneself is what it's about at the end of the day and that's a subjective determination. However, as the original poster noted was set forth in the NRG specifications: "...it is reasonable to expect a new ship model to last one hundred years before deterioration is visible." He then asked, "...what materials (adhesives, woods, metals, paints, rigging materials, fillers, etc.) might appear suitable for a model, but should definitely NOT be used in a model expected to last a century?" So I addressed that question. I suppose that like it seems to be with everything else on the internet, when it comes to ship modeling, there's a right way to do things and then there's a myriad of opinions on how to do it by people who don't know their butt from a hot rock, followed by a contingent who argue, "What difference does it make, anyway?" I think the better course is to advocate "best practices" in the first instance and let circumstances dictate the exceptions. "What difference does it make? You won't be around to that long yourself." sort of seems to be beside the point to me. Somebody famous once described ship modeling as "the pursuit of unattainable perfection," or words to that effect. It's the process of striving for perfection that it's about. Such perfection being unattainable in any event, why else would anyone bother to do it?

-

Very true. Most quality artists' paints, in the US, these would be Windsor and Newton, Grumbacher, Liquitex, and the like, have various levels of quality, priced accordingly. Their "professional" or "archival" level is the "good stuff," from there, they sell less expensive "student" or "amateur" paints. The big difference is in the quality of the pigments, both as to color stability and fineness of their grinding. It's generally been my impression, at least since Floquil went off the market, that "modelers' paints" are generally of a lower quality compared to professional "archival" quality artists' paints sold in a tube. I first used an acrylic paint on a model back in the early 1980's. I needed to paint an "H" signal flag ("I have a pilot on board") for a pilot schooner model and didn't have any red paint handy. Being lazy, and it being a small part, I used some from my daughter's kid's paint set that "cleaned up with water." The model has always been in a case and kept out of direct sunlight. That signal flag, which used to be red and white, is now pink and white!

-

Read the article you cited. If they mention a material, it's suitable. If they don't, research it online. "Archival" is a term used by the fine arts professionals to mean a material will last for at least a hundred years. Search and find out whether the material is considered "archival." Many modern materials, generally plastics, acrylics, polymers, and cyanoacrylate adhesives, are not archival. You want to avoid anything that deteriorates, which includes particularly materials containing acids. For a more detailed set of specifications, see Howard I. Chappelle's General Preliminary Building Specifications, written for submissions to the Smithsonian Institution's ship model collections. http://www.shipmodel.com/2018SITE/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ship-model-classification-guidelines-1980.pdf Paints and varnishes are a particularly dangerous pitfall in modern times. Chapelle's Specifications were written in 1961, just as acrylic coatings were becoming available. His broad reference to paints addresses traditional oil-based paints, not the water-based paints now dominating the market. The water-based paints, not yet a hundred years old, are seen by conservatives as not proven to be archival, although others are very optimistic that they will prove so in time. As with any paint or varnish, the archival quality is in large measure a function of their manufacture. Cheap paint will never be archival, regardless of its type. Only the highest quality paints should be used, which will cost more, but not so one would notice it in the small amounts used in modeling. Such archival quality paints will generally say so on the tube or bottle. Since Chapelle's Specifications were written, some then-common materials have become relatively unavailable, notably ivory, ebony wood, and linen thread. Modern substitutes have to be found, but great caution must be exercised in their use. For example, early Dacron thread deteriorated quickly when exposed to UV radiation, not what you'd want to use for rigging! Some respected museums are comfortable with modern synthetic thread and others are not. We have to make do with what's available. This requires doing a fair amount of online research to identify suitable substitutes, a skill most modelers come to realize is essential. Sometimes, we just have to close our eyes, hold our noses, and jump in. Leonardo Da Vinci's Last Supper began to exhibit marked deterioration less than 25 years after he painted it and has continued to deteriorate to this day, only five percent of it remaining as original, because he decided to experiment with a new oil painting technique instead of using the tried and true tempera paint fresco techniques of his time. The "Old Masters" enthusiastically used the then-newly-invented blue smalt pigment as an alternative to the very expensive ground azurite or lapis lazuli pigment which were previously available in their day without realizing that over decades smalt in oil becomes increasingly transparent and turns to brown, dramatically changing the appearance of colors. Consequently, Rembrandt's later works look overwhelming dark and brown and what we see today is not what they looked like when new. Vermeer, on the other hand, "bit the bullet" and used the very expensive ultramarine blue pigment, and so his Girl with a Pearl Earring's blue head scarf remains with us to this day, albeit with a fair amount of cracking. Many modeler's will say, "Oh, posh!" I build models for my own enjoyment and I could care less how long they last. To them I say, "Very well. Go for it!" The task of those who pursue perfection is more challenging. Do we stay with the "tried and true," like Vermeer, or do we experiment with new techniques and materials, like Rembrandt and Da Vinci? I suppose the real question for our age is whether we good enough at what we do to risk a surprise, which Rembrandt and Da Vinci unquestionably were able to do.

-

Electric sanding belt file

Bob Cleek replied to Don Case's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Oh yeah! And not just "looks like the same...," either. Some years back I bought a set of bathroom fawcets to replace the ones in a remodel we were doing. They were a name brand, Delta, I believe. I got them from Home Depot, I recall. When my buddy, a plumber, came by, he asked where I got the fawcets and when I told him, he shook his head and said, "If you want to pull these ones out and return them, I'll get you better ones. I pulled them out and he came by with what looked like the identical fawcet set, new in the box from the same manufacturer. I said, "These are the same." He smiled and opened one up and pulled the valve cartridge out of it. It was some sort of plastic. Then he opened up one of the replacements he'd brought from his shop and pulled the valve cartridge out of it. It was all metal. In short, the outside castings were the same, but the "guts" of the two models were very different. I was happy to pay him the lower (wholesale) price for the ones he brought me and I returned the cheapo ones. He explained that the big box stores often buy huge numbers of units and have the manufacturers cut quality to bring the price down. You think you are buying the very same name-brand product, but it isn't. -

"Gun metal, also known as red brass in the United States, is a type of bronze – an alloy of copper, tin, and zinc. Proportions vary but 88% copper, 8–10% tin, and 2–4% zinc is an approximation. Originally used chiefly for making guns, it has largely been replaced by steel." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gunmetal Yet another example of imprecise nomenclature in common usage!

-

Blocks move easily in both directions. A free-turning block makes the work easier because the friction is low. Deadeyes, on the other hand, aren't intended to move freely. Friction is a good thing in a deadeye. Deadeyes, having no moving parts, are also somewhat easier to manufacture than blocks and they are stronger because they distribute their load more. Blocks carry their entire load on the sheave axle. Deadeyes are adjusted when first "setting up" rigging or when taking up the stretch in new standing rigging after it "settles in," but aren't otherwise generally intended to be adjusted periodically. The lee shrouds will be slack and the windward shrouds tight when the ship is under sail. They change places every time the ship is tacked. Nothing is done to the deadeye lanyards when that occurs.

-

Electric sanding belt file

Bob Cleek replied to Don Case's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I'd draw the same conclusion! I think the reviews on MSW are quite reliable. -

Electric sanding belt file

Bob Cleek replied to Don Case's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Before I could say, "Don't get me started...." Wen Tools used to be a mid-range US electric tool manufacturer of fair repute during the last half of the 20th Century . They were perhaps best known for their "second best" or "DIY quality" soldering gun, which competed with Weller's, and their "second best" rotary tool which competed with Dremel's . Wen has always targeted the occasional, non-professional user, rather than the professionals and its greatest selling point has been its lower price. Now the Wen brand has, from all indications, become just another casualty of the power-tool market. Remember reputable brands like "Bell and Howell," (movie cameras,) "Emerson," (radios and TV's), and just about every tool company you've ever heard of? Times have changed. Today, the brand names themselves have become commodities, monetized for their "customer loyalty" and established good reputation. The business model is 1) buy out a brand name with a good reputation, 2) "value re-engineer" the products by reducing the quality, plastic parts replacing metal where possible, etc., 3) close domestic manufacturing operations and move manufacturing to low-labor-cost Third World factories, 4) slap the reputable label on "generic" offshore products, 5) flood the market with advertising touting the brand name without disclosing the change in ownership and manufacturing origins, and 6) reap the profits for as long as possible until the consumers finally, if ever, figure it out. You still get what you pay for, to a large extent, because the higher priced units will generally have better quality control, warranties, and customer service, although, sometimes you get lucky and find a lower-priced brand of the same unit, built in the same factory in China by the People's Patriotic Power Tool Collective which just happened to be assembled "on a good day." If you think today's Milwaukee are any different, think again. Milwaukee is Chinese-owned and Chinese-made, one hundred percent. Unfortunately, these new offshore "name brand owners" are very internet savvy. If you go trying to find reviews and comparisons of their products, you'll find multiple websites posing as "neutral reviewers" which, using the identical language, wax eloquent about how great their products are. It's all a big con job. While Wen tools were once "Made in the USA," Wen is, by all indications, simply selling Wen-branded generic Chinese-made tools these days. Wen never was a top tier tool manufacturer, anyway. It's market niche, even in the 1950's, was the homeowner interested more in price point than quality. Find the Wen: Read the links below to get some idea of how pointless it is for us to even begin to look to a label as any indication of the quality of a tool these days! With all the internet purchasing, we can't even hold one in our hand before buying it. About the best we can do is to ask the guy who has one, and be careful of doing that if it's just an Amazon review! https://pressurewashr.com/tool-industry-behemoths/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_tool_manufacturers So, sorry for the thread drift, but I couldn't help but rant about the sorry state of tool quality these days. -

The distinction appears to be a matter of semantics. Bronze is a copper alloy commonly used below the waterline. While I'm aware of the use of copper bolts, rivets, and drifts as construction fastenings, which are somewhat encapsulated in the wood and not in direct contact with the salt water electrolyte, I've never heard of copper, as opposed to bronze, underwater rudder fittings. Copper, alone, isn't all that strong. Bronze is much easier to cast than copper, as well. I'm also aware of the corrosion issues realized with wrought iron in contact with a coppered bottom. In Cutty Sark's case, she was indeed a composite build with iron frames and sheathed with Muntz metal, another copper alloy that is considered a brass. The Muntz metal, which is very resistant to galvanic corrosion, may have been closer to wrought iron on the galvanic scale, or they simply considered the iron rudder fittings "sacrificial" and replaced them as needed, as they would have had plenty of "meat" to spare. I do know that when I was in her hold, decades ago before her total rebuild, when she was, shall we say, "less than fully restored," her iron frames showed no gross corrosion, but appearances can be deceiving, I suppose. Your mention of HMS Pandora demonstrates the semantic confusion. An alloy of 87.3 percent copper and 6.9 percent tin, with trace amounts of lead and zinc (commonly added to improve machineability) is decidedly a bronze, which are alloys of copper and tin, albeit with a somewhat lower amount of tin than is seen modernly. (Copper-zinc alloys are brasses.) Clearly, the terms "hardened copper" and "copper alloy" were referencing a bronze. (The zinc in brass being, less noble than copper and iron, would deteriorate in short order, leaving something of a micro-crystaline copper "Swiss cheese" which would have little or no strength.)

-

Trix X acto history?

Bob Cleek replied to FlyingFish's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Correct! -

That copper wouldn't stay shiny bright like that for more than a few weeks, at most. Polished brass (not bronze) is standard procedure for naval ships, and most others that are kept "Bristol fashion," but that's going to be limited to binnacles, bells, bulkhead clock cases, signage plates, door knobs, railings and the like. Only brass is kept polished. Never bronze, which is left to weather gracefully to bronze brown. BTW, those ham-fisted monkeys in the picture posted of them coppering Constitution are making a dog's breakfast of it. They are using regular carpenter's hammers and the denting of the plates sure shows it. There's a proper tool for the job called a "coppering hammer." Its face is convex and smooth. It drives the tack home and makes a smooth dimple in which the tack head sits and has a claw made to fit copper tacks. Here's a photo of Cutty Sark's coppered bottom, which has never seen water. Done properly with a coppering hammer, she doesn't look like she's got the pox. She was sheathed with Muntz metal, a patent alloy used in her time which is 60% copper, 40% zinc, and a trace of iron, in essence, a brass. It has to be heated when worked, but it's about two-thirds the price of pure copper. Nobody polishes it, though. Muntz metal holds it color about the same as brass and the photograph was taken when the ship first went on display after her restoration. But bright metal on the prototype will be less glaring at scale viewing distance on a model. It's reported that some gun crews kept their gunmetal (brass) guns polished as a matter of pride. Iron guns and all other ironwork was painted with a mixture of linseed oil, Stockholm tar, and lampblack to prevent rust. And copper gudgeons and pintles, never. They were bronze, if not wrought iron. Copper was not sufficiently strong for heavy load-bearing. Brass was never used for chain for the same reason. Note the photo of Cutty Sark above. Here rudder fittings are wrought iron, her yellow metal bottom notwithstanding.

-

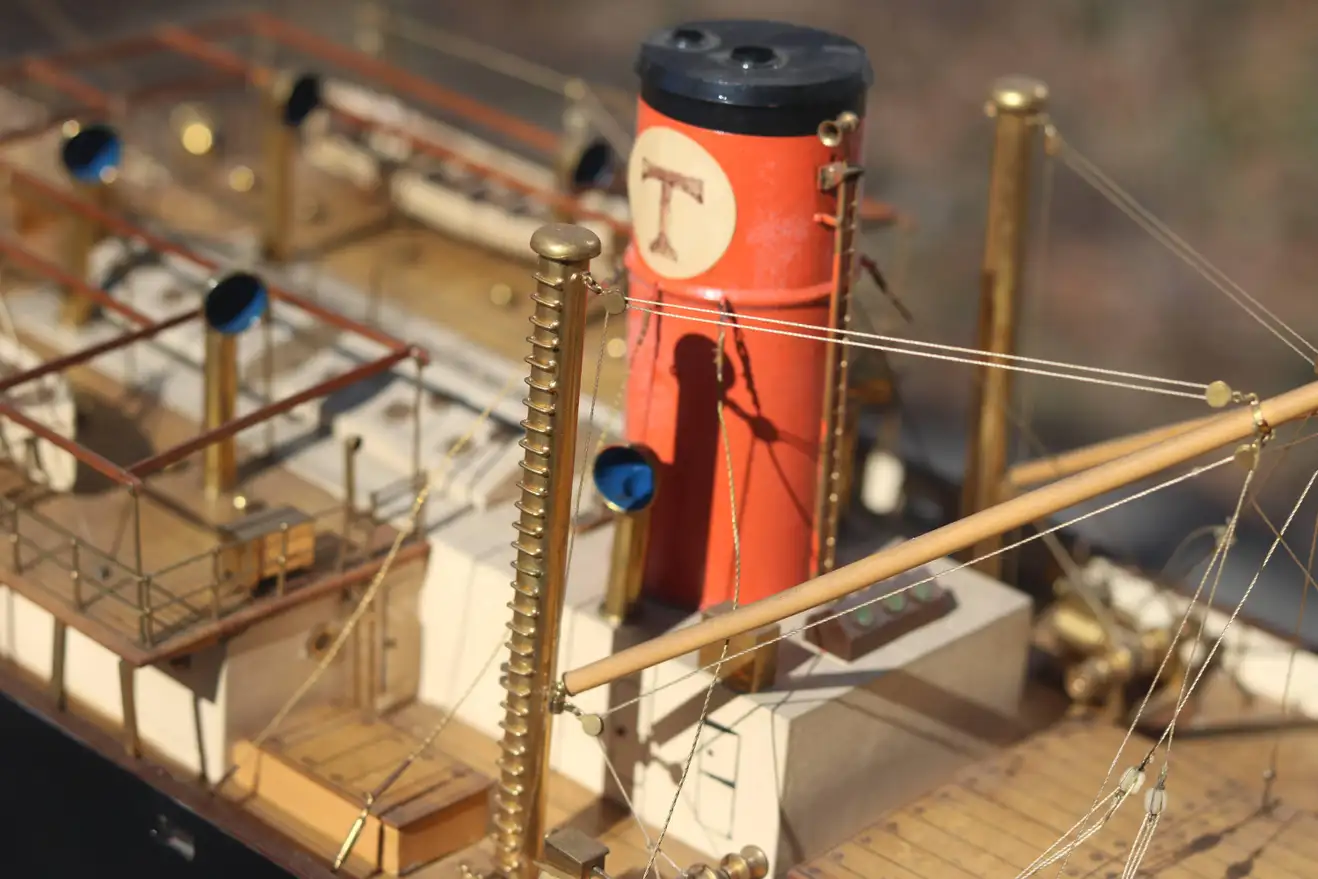

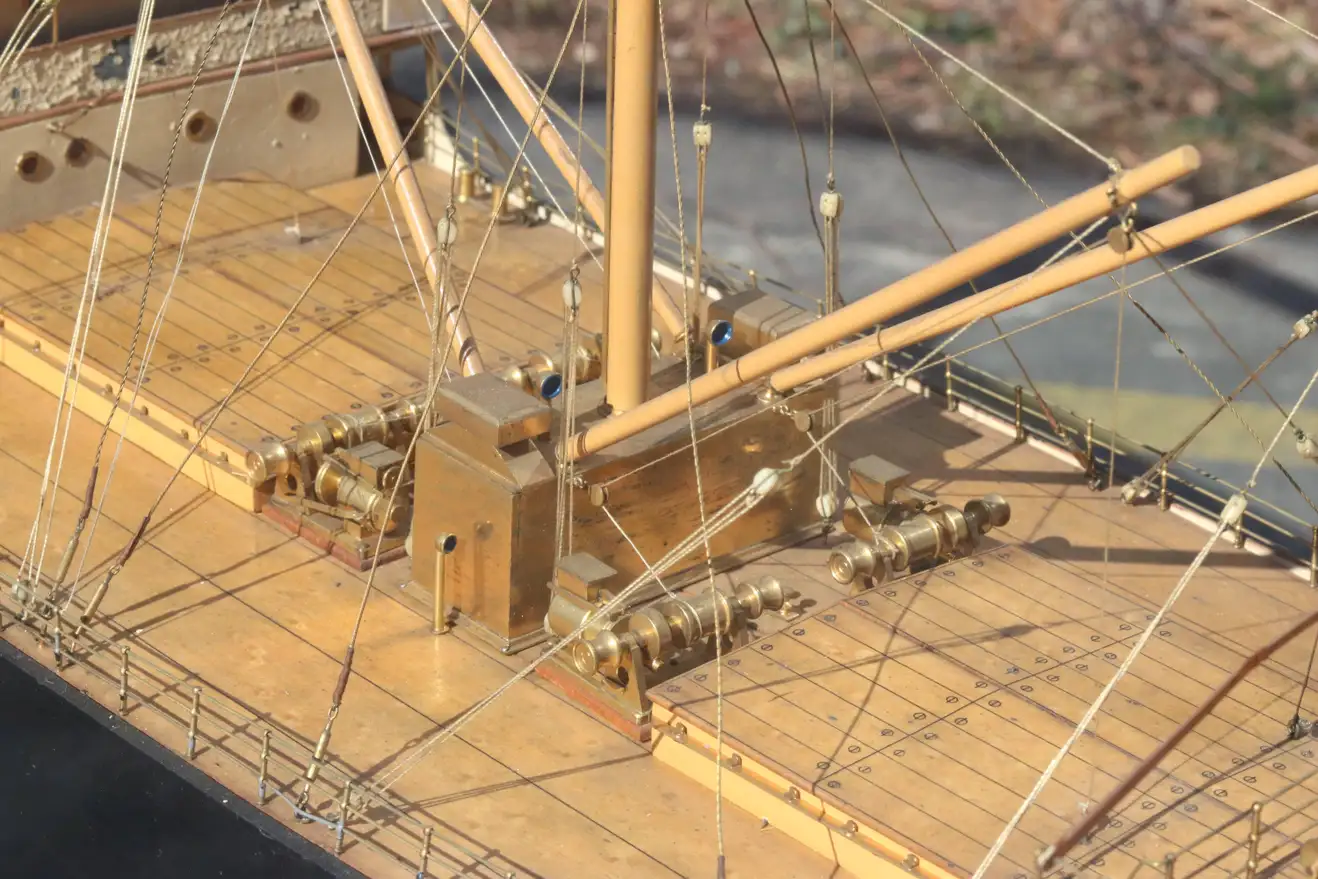

And whoever said it was ever appropriate to use bright copper and brass on an historically accurate ship model? It's a matter of style. To my mind, in MY opinion, as others have said, an historically accurate ship model should portray the historical features accurately. That said, some amazing builder's yard models of the "golden age" had all their metal parts gold plated! It was a style in vogue at the time to show off the quality of the craftsmanship and it yielded a spectacular artistic effect. These models were historically correct, but not visually correct. An alternate style is to leave all materials "bright," i.e. "unfinished" as is the style currently in vogue in European modeling of "Admiralty board" style models. (Not all of which were so built.) Finally, there is the style of modeling a "compelling impression of reality in miniature," which portrays the subject as the viewer would see the subject vessel from a "scale viewing distance" in real life. All of these classic styles are valid and can produce spectacular models. That said, mixing these styles up in the same model is often detrimental to the overall result, and sometimes catastrophically so. Needless to say, out of scale and misplaced trunnels, deck planking butts, copper sheathing tacks, and a myriad of incorrect colors are not historically correct, and yield a crude result. It should be noted that leaving uncoated copper unfinished will, as the copper naturally oxidizes, yields a very convincing appearance of naturally weathered bronze fittings. This is a good technique for portraying bronze railings and handholds, cleats, winches, and the like, particularly on models of yachts which carry quality metal fittings. For those who may not be familiar with a bright metal builder's model (in apparent need of some restoration attention... note the faded paint on the stack, damaged rigging, and bent stern railing): and, if you want to give your model-maker's ego a real beating, check out the builder's model of Mauretania! : And RMS Berengaria, with bright metal only where it would have appeared at "scale viewing distance."

-

Trix X acto history?

Bob Cleek replied to FlyingFish's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Bingo! You win the internet today!

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.