-

Posts

7,990 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Louie da fly

-

There are also many other ancient Greek sources, such as the Odyssey and perhaps the Iliad, as well as Thukydides (is that spelled right?) and other contemporary historians. Even with the fictional stories such as the Jason and the Argonuts, and the Odyssey, the author was writing for an audience who knew whether people wrote names on their ships, carried shields on board etc, so the information would probably be fairly reliable. You may find also that if you contact the people who built the Argo reconstruction they might be able to help you. I think the article I linked to in my last post contains a contact section. Steven

-

Pasanax, have you seen the Youtube video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-s_0bwC7Hi8 of the reconstruction and sailing trip of Jason's 50-oared Argo? There's an article about her at http://www.argonautes2008.gr/en/argo-ship/new-argo-ship.html The reconstruction looks very good to me - the construction method is correct, using tenons between the planks, so I think the research for her shape and layout was probably also correct. I don't know the answers o the questions in your first post, but I've never herd of a drum being used on a Greek galley. I expect the oarsmen would have had spears and shields, though I don't remember seeing them on any contemporary pictures of the ships, so perhaps they were stored out of sight somewhere. I've also never heard of an ancient Greek galley's name being written anywhere on the ship - you might try reading such things as the story of Jason and the Argonauts and historical descriptions of voyages to see if it's mentioned. If not, I think you're safe leaving it off. Best wishes, Steven

-

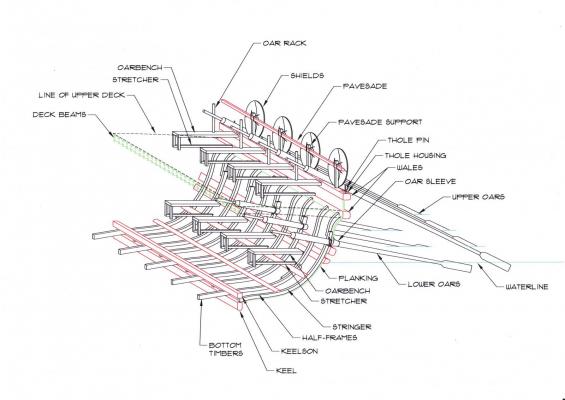

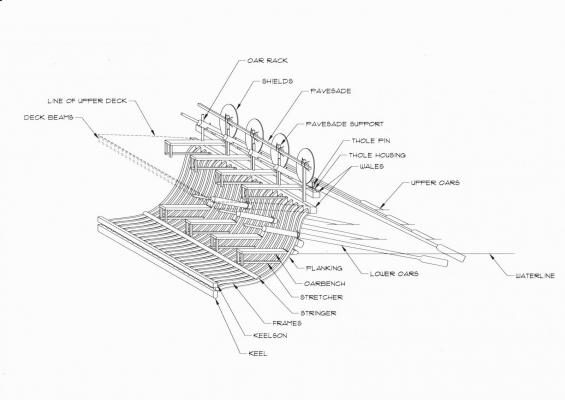

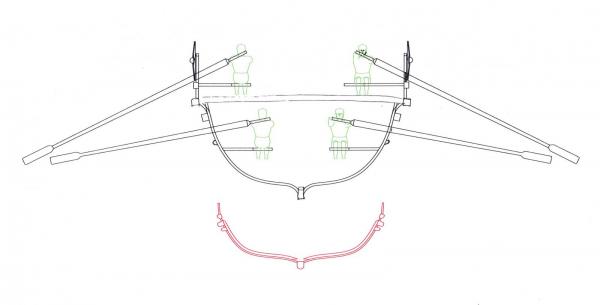

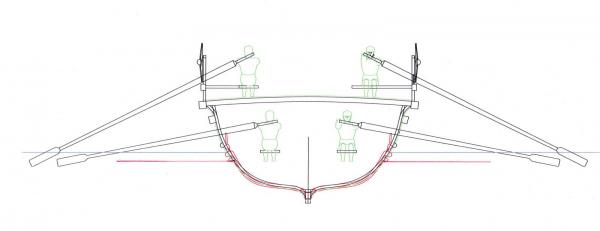

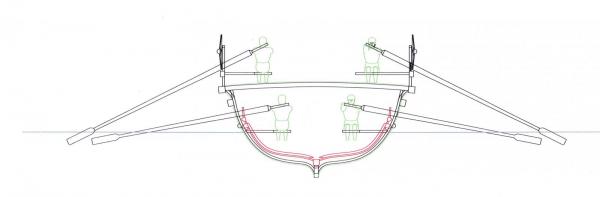

Well, here's the amended drawing of the midships section. I've exaggerated the distance between the frames for clarity - with this you can see the alternating bottom timbers and half-frames. I haven't yet sorted out some of the issues, such as how the lower benches are supported at the inboard end - the outboard end is set into a mortise in the wale, and the inboard end of the upper ones rests on the deck, but I have to work out how to support the ower ones - presumably they'll be supported by the frames. I'm pretty happy with this layout, and I'll probably also see if I can find space to fit such items as water barrels (galley crews needed a LOT of water) within the hull. Prof Pryor's book shows possible places to store stuff, and I have the opportunity to test the theory out in the real world. The house renovations are nearly complete. I'm hoping that will give me the opportunity to get something started fairly soon - but of course life often gets in the way, so we'll just have to see how it goes. Steven

-

Ben, I just caught your video. That's totally amazing! Such maneuvrability! Much better than the previous videos I've seen of model galleys in action. I take my hat off to you, sir. Stven

-

Curioser and curioser - On re-reading the archaeological report of the Yenikapi galleys, I've discovered I'll have to amend my cross-section drawing yet again. It seems the frames in mediaeval (and earlier) Mediterranean ships in general, and in the Yenikapi galleys in particular, followed a . . pattern of alternating floor timbers and paired half-frames . . . Floor timbers span the bottom of the ship, with their extremities extending just to the turn of the bilge [on each side of the ship]; in contrast, half-fames span the width of the keel and extend up one side of the ship, through the turn of the bilge to, or just beyond, the first wale . . . At each frame station, floor timbers and half-frames are paired with futtocks placed adjacent to, but not fastened to, the floor timber or half-frame, with ends overlapping by the width of one or more planks. The bit in square brackets is my addition, to clarify that the floor timbers reach right across the bottom of the ship, from side to side. I can't do it at the moment, but I'll amend the drawing to reflect this framing pattern when I get the chance. Steven

-

I just came across a very interesting video on Youtube of a reconstruction of Jason's Argo under construction and then in action. Shows the "shell-only" (i.e. frameless) construction of the ship, using coaks between the planks - see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-s_0bwC7Hi8 Steven

-

I just came across a very interesting video on Youtube of a reconstruction of Jason's Argo under construction and then in action. Shows the "shell-only" (i.e. frameless) construction of the ship, using coaks between the planks - see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-s_0bwC7Hi8 Steven

-

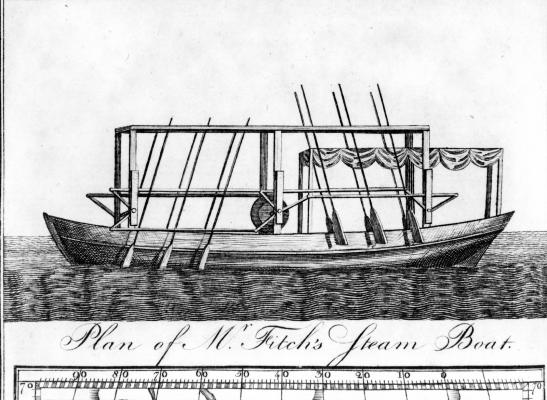

Yes indeed, Ben. In fact Fitch ran the first steam powered passenger service up and down the Hudson River for a considerable time and had a long-running battle with Fulton (of Clermont fame) as to who had the right to do so, and who had stolen the idea of the steamboat from whom. He used lever-driven paddles because Benjamin Franklin had told him paddle-wheels were never going to work. Fulton won in the end, but I have a lot of sympathy for Fitch - an original mind, but with the odds stacked against him because of his origins and lack of education. I found about him from a book called Steam by Andrea Sutcliffe, which my son gave me for a birthday present. It's fascinating, and I'm very grateful to him for it.

-

That sounds like the best way to go, Ben. I was wondering if that'd be an option. I wish you the greatest success with it. By the way, there are other intersting "oar-powered" vessels out there which would lend themselves to RC. The most interesting in my book is the steamboat built by the American John Fitch in the 18th century - see http://www.nysl.nysed.gov/mssc/steamboats/player_fitch2.htm . The clearest representation I've seen of the boat is below. Thought you might be interested. Steven

-

Thinking about Dick's question regarding the relationship of the frames to the lower oarports, I've come up with what is probably a workable answer. Working on a spacing of 0.96 metres between benches (as this seems to be pretty much the average found at Yenikapi), that would also mean 0.96 metres between oarports. The average spacing between frames found at Yenikapi seems to be between 200 and 230mm, which is between 1/4 and 1/5 of that distance. If I spaced the frames at 240mm centres, there would be exactly four of them between adjacent lower oarports, and there would be no need to modify the frame spacing to allow for them. With the Yenikapi ships the shipwrights had no need to worry about this issue because those had only a single bank of oars. YK16 had two upper wales with a 55mm strake between them (and I believe YK4 is similar) with the benches mortised into the lower wale, and it appears the thole supports were fixed to the upper wale. As the frames end at the top of the upper wale, there would have been no need to take them into account when spacing the frames. Another point is that this was a time of transition when ships were being built "shell-first" - that is, the keel was laid and the planks fixed in place before the frames were added. This would have given the shipwright more freedom when deciding on spacing of both oarports and frames. I'm sure when it came to building dromons the shipwrights with several hundred years of experience behind them would have worked out in advance how to place the frames so the oarports would not cause problems. However, as no dromons have ever been found, we can only speculate and use what's been found on the Yenikapi ships as a basis for a 'best guess' design. Steven

-

Thanks everybody for the "likes". They are much appreciated. Dick, I'm using AutoCad LT 2006, which I use in my 'real world' business designing houses. I find it very helpful, but it's only in 2 dimensions (3D AutoCad is prohibitively expensive). I take your point about frame positions, and for the midships section I'll probably come up against this if I decide to do it in full. However, the Yenikapi ships show considerable variation in the spacing of their frames, benches and oarports, and the spacings quoted are only averages. So I might be able to "tweak" the spacings to allow the oarports to go between the frames without playing around too much with the frames themselves. Additionally, there are quite a few frames on each of these ships where the different frame members are next to each other instead of in the same line, so that could be done as well without feeling I'm departing too much from what was actually done. This has turned out to be quite a challenging build, and I haven't even picked up a piece of wood yet! Steven

-

Oh, I wasn't proposing that all the oars would be stored inboard; only the upper bank, and only immediately before and during battle, at which time the masts were also lowered, and the uppr oarsmen became fighters - the lead oarsman on one side becoming (and I love this name) the siphonator, operating the Greek Fire apparatus. As you say, the lower bank would be needed for manoeuvring, and yes, you're right, there's a case on record where the upper deck was overrun and the lower oarsmen weren't, though there are various versions of the story, including one where the lower oarsmen rowed in the opposite direction to the (enemy) oarsmen of the upper bank. This is covered in Age of the Dromon, but Prof Pryor doesn't believe it's physically possible, and that instead the chronicler embroidered the orginal story. Another reason to store the upper oars inboard is that they would otherwise, particularly if fixed in the same way as those in renaissance galleys (see below), get in the way of missiles being fired at the enemy vessel. The lower oars would certainly help provide lateral stability, which would be very important in a vessel as inherently unstable as these. By the way, I'm amending my earlier post to replace the drawing I attached with one which I hope more accurately depicts what I have in mind, including getting the oars and shields in the right relationship to each other, and adding the leather thongs to the thole pins. Steven PS: Kees, I'd also thought that galleys were always rowed by slaves. It took reading The Age of the Galley to change my mind about that.

-

Dick, you make a good point, and certainly renaissance galleys had their oars at "rest" angled upward but supported in their rowlocks. However, they were used in a very different kind of fighting where a galley's function was to sink other vessels with gunfire. They also had only a single bank of oars, which they kept in use during a battle. Mediaeval galleys' crews relied on attrition of the enemy's crew with missile fire, followed by boarding, and after a lot of thought about this, I believe the upper bank oarsmen would have been most likely to put their oars in "storage" to give them the greatest freedom of action. But my proposal is that they are stored running fore and aft right next to the sides of the ship. In this way they shouldn't restrict mobility on board. You're right, though - the approved tactic seems to have been to try to attack an enemy vessel from the quarter, preferably smashing up their oars with the bow-mounted spur, followed by boarding. I can only think the lower oarsmen must have pulled their own oars inboard (they were shorter than the upper ones) just before impact, but the information available is so thin on the ground that we really know nothing for certain. Even the replacement of the ram with a spur is still not fully accepted by academics, let alone a lot of the other information we have on battle tactics. Much of the contemporary battle advice, such as the treatise of Emperor Leo VI, seems to have been written from the comfort of an armchair by someone who'd never been to sea. The flare of the upper works is in fact what Prof Pryor believes is the only possible solution to the problem of clashing oars. He devotes a whole chapter of Age of the Dromon to this problem, but he acknowledges that it's still only theory till it's tested in the real world. Kees, the oarsmen in galleys of antiquity and the middle ages were free men, and galley slaves don't seem to have been introduced until the renaissance, as a response to a shortage of skilled oarsmen and freemen willing to work at the oars. Rowing a galley was a skilled activity, and good oarsmen were valuable. The most valuable on a dromon were the upper oarsmen, as they doubled as fighting men, and Leo VI recommends that the less brave of the oarsmen be placed on the lower bank. Steven

-

I don't know how much of the ship was below the floor planking, but there are cross sections at http://nautarch.tamu.edu/class/316/oseberg/ and at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/33098/33098-h/33098-h.htm#f22 which might let you know if it's enough to fit your radio control equipment below it. Hope that helps, Steven

-

Here’s a drawing of the proposed midship section for the dromon, to be built at a scale of (probably) 1:20, and intended to sort out whether the upper and lower banks of oars will successfully avoid fouling each other when in action. I haven’t decided how detailed to make it – just a basic mechanical construction to test out the above question, or something fully detailed? After all, the dromon itself is the main goal, but in the meantime I’ve drawn the section in full, in case I choose to do it that way.. Though for the full model I’ve followed Professor Pryor’s lead in having the oar benches angled at 18.4 degrees to an athwartships line , I’m still in two minds about it, and I’ve shown the benches in this section as being directly athwartships (i.e. at right angles to the keel). Interestingly, a thole and its “housing” were found in one of the Yenikapi wrecks, but the housing only contained a single hole. Experience with the Olympias reconstruction showed that most of the force expended by the oars at the fulcrum was taken not by the thole pins themselves, but by the leather thong which tied the oar to them. I've now shown the thongs on the drawing, but I haven’t yet added the leather sleeves for the lower oarports, designed to keep water out. As the upper oarsmen doubled as marines during sea-battles, and fought the ship rather than rowing - I've had to figure out what did they do with the oars. The dromon is 4.4 metres wide at its widest point, but the upper oars are over 5 metres long. You can’t pull them inboard – they’d stick out by about a metre either side, making it impossible to come alongside and grapple the enemy (and expose the delicate ends of the oars to damage). Not only that, but it would be murder trying to clamber over them to get from one part of the ship to another – an important consideration during a battle. If you lay the oars fore-and-aft along the deck inboard of the benches, they obstruct access to the benches themselves (the benches are only about a metre apart, so you’d have a stack of oars rolling around getting in the way). The best solution I've been able to come up with – and I’m aware it can’t be proven to be correct – is to have a row of uprights sticking up out of the benches about three oars’ thickness in from the side of the ship. The oars can be racked between these uprights and the side, two or three high, with very little obstruction either for access to the benches or for crew fighting at the side of the ship. Another question I have yet to resolve – was there a catwalk for the oarsmen of the lower bank, or did they simply walk along the tops of the frames? I believe the frames would be close enough together (200-230mm or 10-11 inches) and sturdy enough to be walked on, so a catwalk would be unnecessary. You’ll note the ship has several heavy wales – about 150mm (6 inches) square, to help prevent hogging, and a stringer running along the bottom for the same purpose. These have been found on the Yenikapi galleys, and on a dromon the deck would strengthen the vessel further. There are shields along the sides to protect the upper oarsmen, and it’s mentioned in contemporary accounts that they fought from behind them. The shields are supported by a rail known as a pavesade, probably hung from the pavesade uprights by the enarmes – the leather or rope straps by which the warrior carries his shield in battle. At sea the shield would also have to be tied down further so it wouldn’t flap around with the movement of the ship. Steven PS: The attached drawing has now been amended to show (I hope) the proper relationship of oars, shields etc.

-

Well, Viking ships came in all kinds of sizes - from the Wikipedia entry: "Longships can be classified into a number of different types depending on size, construction details and prestige. The most common way to classify longships is by the number of rowing positions on board. Types ranged from the Karvi, with 13 rowing benches, to the Busse, one of which has been found with an estimated 34 rowing positions." So perhaps you'd be interested in making a Karvi. The only problem that might arise is that Viking longships were basically just really big open boats so there'd be a difficulty hiding the radio control mechanism, if that's the way you're planning to go. Otherwise - go for it! I may be able to help; having spent many years as a Viking Age re-enactor, I've done a lot of reading on Viking ships and might be able to answer questions as they come up. The model is looking really good. I'm very impressed, and look forward to seeing her in action in the water. Steven

-

But your galley is already a warship – that’s why it’s got a ram! I’m not sure the smallest war galley that existed in Ancient Greece, but the most common before the introduction of the trireme was the pentekontor (or penteconter) – the 50-oared galley. The 50 oars was I think a pretty loose description, and I think yours would count as a pentekontor despite only having 44 oars. The best and most comprehensive book I know on galleys is The Age of the Galley, http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=nb_sb_noss?url=search-alias%3Dstripbooks&field-keywords=the%20age%20of%20the%20galley and I’d highly recommend you get hold of it if you can – perhaps your local library can obtain it. It gives a good overview (and a lot of theoretical detail as well) on Mediterranean galleys of the ancient, mediaeval and renaissance eras. The video of the model galley ramming the merchant ship is pretty cool, but it looks like the oarsmen must have taken performance enhancing drugs to get that rowing rate. Perhaps the owner needs to gear the thing down a bit. I don't really know what would be the best material to represent leather for the oarports - perhaps fine fabric with varnish or some other sort of goop through it? Or thin vinyl? I don't think real leather comes thin enough to do the job. On Olympias the sleeves were made of four pieces of leather, each in the shape of a tapered rectangle (if that makes sense - I suppose I could call it a trapezium), and sewn together at the edges. An interesting thing about ancient vessels, galleys included (at least if I read The Age of the Galley right), is that they were built without frames – the planks were fastened edge to edge with hundreds of coaks – small tenons fitting into slots cut into the edges of adjoining strakes, in the same manner as “biscuit” joints in modern woodworking. The skill and precision needed to do this completely blows my mind. Even when frames were introduced in the early Middle Ages, they were added after the shell was built, and coaks survived till at least the 11th century AD, though in much reduced numbers. It was this frameless construction that made ancient galleys vulnerable to ramming – the coaks just broke or came undone, letting the water in. Vessels with frames were too strong for ramming to be effective, and rams disappeared from the scene. Fascinating stuff . . . Steven

-

Galleys were built incredibly light - the Byzantine ones they've found in Istanbul's Yenikapi district have frames 50-60mm (2 to 2.4 inches) square in section, and the planks were 20-30mm (3/4 to 1.18 inches) thick. The oarports are that close to the water, and they've found nail holes which seem to confirm the existence of leather "bags" around the oarports, something mentioned in Ancient Greek texts. Olympias, a reconstruction of an Athenian trireme is 121 feet long, with a crew of 170. There's a video of her sea trials at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZcsrNrRkQis which is very enlightening. The practical trials turned up a lot of worthwhile data - the Olympias didn't reach speeds as fast as recorded in antiquity, and it is thought that the speed would have been higher if the distance between oar-benches had been slightly greater to allow the oarsmen freer action. It's also believed there would have been less interference between oars (and fewer broken oars) if the arrangement of the oars had been somewht different. Olympias was very sensitive to changes in trim - even the movement of one person on the top deck. All galleys were very sensitive to weather conditions and generally completely unsuitable in seas above 3 feet high. There are many recorded instances of entire fleets of galleys being lost in storms, and the Mediterranean campaigning season was only during the calmer months of the year, and even then an unexpected storm could be catastrophic. Nonetheless. the galley was the front line warship of the Mediterranean for over 1000 years. Steven

-

The other thing is that perhaps many of the ships pictured were portrayed as the artist saw them, in harbour, empty except for ballast, waiting for a cargo. Carpaccio's St Ursula carracks certainly seem to be riding high enough in the water for this to be so, and probably several others. Steven

-

Well, if as Dick says many the pictures are taken from ships out of water (or sitting in dock empty) this would be understandable - the artists simply got the position of the waterline wrong. Looking at the picture immediately below the photo of the model seems to me to show a more likely position for the waterline. And other contemporary representations, though they do seem to be riding fairly high, show a more realistic waterline position.

-

I dips me lid, Dick. That is seriously beautiful work. If I can get to that kind of standard, I'll be very happy. And every time I think there couldn't be any extra pictures of carracks, you come up with more! Wonderful stuff. Steven Jan B. Not to derail the thread, but those flying cats are just amazing.

-

A couple of days ago I saw in the archaeological report of Texas A&M University's excavation of ships from the Yenikapi find in Istanbul, something I hadn't noticed before . The drawing of the most intact galley of all, a light galea known as YK4, includes a diagram of the 35th frame of the vessel, which is effectively a midship section. Out of curiosity I printed it off as large as I could, drew up a grid of 1 metre squares around it and copied its shape on my computer to the same scale as the plans for the proposed dromon model, taken from Professor John Pryor's reconstruction. To compare the two I superimposed the images, and the correspondence was uncanny - at the point they diverge most, the discrepancy between the two shapes is only about 50mm! That a theoretical reconstruction, particularly given the scarcity of information available to base it on, turned out to be so close to the archaeological reality is amazing. Needless to say, I was very impressed, and I take my hat off to Professor Pryor. The only major difference I could see was that the dromon's tholes appeared to be about 170mm higher than those of the ship found in Istanbul. But that was a galea, vessel with just a single bank of oars. A double-banked dromon would be considerably larger and heavier and would sit deeper in the water, so the tholes would be lower. Taking the galea's waterline as being at the bottom of the lowest of the three wales, I re-did the superimposition. They line up perfectly. This has confirmed my confidence in the reconstruction, and that I'll be making something that is very close indeed to the reality of the actual vessel. Steven

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.