Tony Hunt

NRG Member-

Posts

543 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Tony Hunt

-

Superb work Ilhan. The cabinetry is wonderfully regular and symmetrical. Just like the real thing!

-

Hmmm. Methinks I haven't explained myself very clearly! I'll try again. The idea was to create a sketched 3D rendering of the hull, using the photos to get the shape approximately right, then use the clever ability of the 3D software to view the resulting 3D shape from the same viewpoint as the photographer who took the picture and overlay the rendering onto the picture. Kind of like the beautiful 3D rendering of the the pearling lugger PENGUIN (see below, done by a real Naval Architect, not me!) but much simpler. Any discrepancies between the rendering and the photo could then be noted and adjusted, until the two aligned perfectly. Yes? No? It won't work for the underwater shape, of course, but should be possible for everything above the waterline.

-

She's fairly typical for that period and that location. A lot of the early luggers were remarkably small. A surprising number were built overseas, in both Singapore and Hong Kong, and also in New Zealand. I guess Hong Kong isn't much further from Darwin than Sydney is! I think you could certainly use some of the plans already in existence as a starting point, then use the photos to refine them. There was a wider range of shapes and styles of pearling luggers than most people appreciate, and the point would be to create a series of small waterline models that illustrated that range of diversity. Yet another project for the future! 🙄

-

Welcome! There is a very active group of Donal McKay enthusiasts posting on MSW. The most recent thread is about STAGHOUND, but the masterpiece is the research they have done on GLORY OF THE SEAS. You have a lot of enjoyable reading ahead of you!

-

I'm wondering if it's possible to generate a 3D rendering from a good photo that would enable an accurate waterline model to be built from the resulting plans. Let me explain... 😀, using the two images below as a live example. They show two consecutive views of a small pearling lugger that operated from Darwin in the Northern Territory of Australia, named PETREL. An interesting little boat, it was built in 1898 in Hong Kong, by the Whampoa Dock Company Ltd, and was then shipped (unrigged) to Darwin as deck cargo on a steamship. PETREL was registered, so we also have two accurate dimensions to apply to the photo as scale, namely "Length from forepart of stem beneath bowsprit to aft side of head of sternpost = 39 feet"; and "Main breadth to outside of plank = 11 feet". Using these, would it be possibly to draw an approximate plan for a waterline model, then make a 3D rendering that could be overlaid onto the photo so that it is being viewed from exactly the same angle. then adjust the initial plan so that it perfectly matches the photo? This would then allow all the other visible details to be added in, at which point you would have a reasonably accurate plan for a waterline model. I've tinkered with 2D CAD (without much success!) but I'm amazed at what people can create with the 3D software now available. It seems to open up all sorts of possibilities.

-

Great stuff Steven. Another fascinating build, it's been a pleasure to follow along.

- 508 replies

-

Congratulations on your focus and tenacity across such a long build. The finished model looks superb. All the more impressive that it's been achieved at 1/160 scale.

-

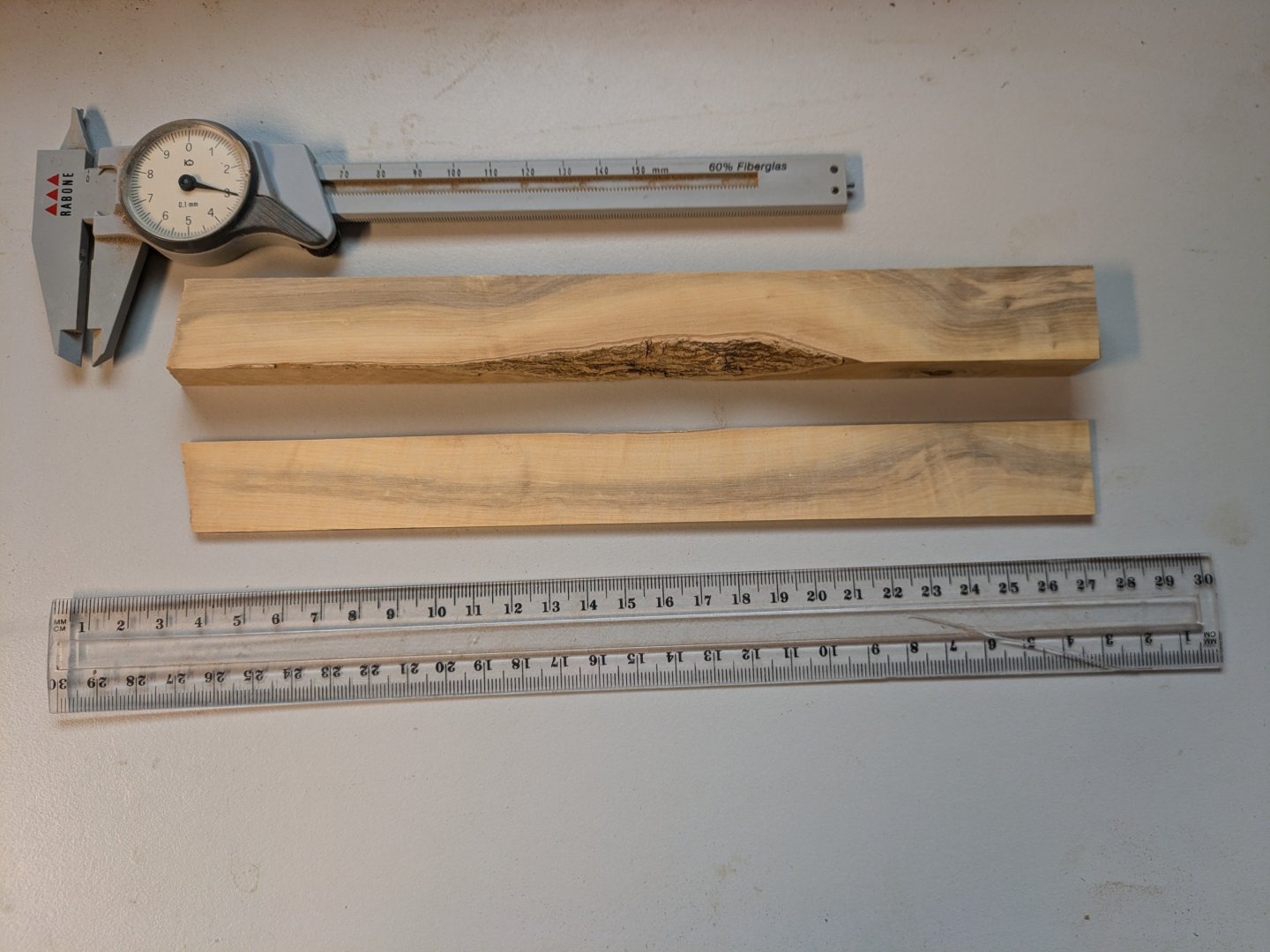

I didn't seal the ends, it was already dry when I got it and it's been kept dry ever since. If it's a fungal stain I think it will be long dead by now, it doesn't seem to have softened the wood. I'll certainly try to quarter saw as much as possible, it doesn't look like it will be a problem to do so. I ended up gluing the block to an offcut of fibreboard, using Weldbond, which is pretty strong. This made it easy to run the block through the saw. For the longer pieces, still to come, I'll use the same technique but I think I'll make a slightly heavier sled using thin ply as the base, and glue a hefty block of pine as a butt stop at the rear of the workpiece to give it more support going into the blade.

-

I agree with Wefalck, it's a superb museum that hasn't lost its way. The models on display are numerous and magnificent. An excellent place to spend a few hours. Or days.

-

Well, I took the plunge and cut a shortish piece off one end, then had a crack at milling it into model-sized lumber. It went surprisingly well, I'm happy (and relieved!) to say. The thin piece was cut to ~3mm thick on the table saw, then brought down to 2.5mm using my little thickness sander. The boxwood seems to have a nice hard, tight grain, mostly the expected yellow colour but with a grey streak through it, quite pretty! It has that unusual honey-like smell that boxwood seems to have when freshly cut. So far, so good!

-

I just found this build log. It's looking great so far! I'm just down the road, in North Rocks. I like the Triumph in your avatar too - we'll have to go for a ride together sometime!

- 92 replies

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.