-

Posts

187 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by G. Delacroix

-

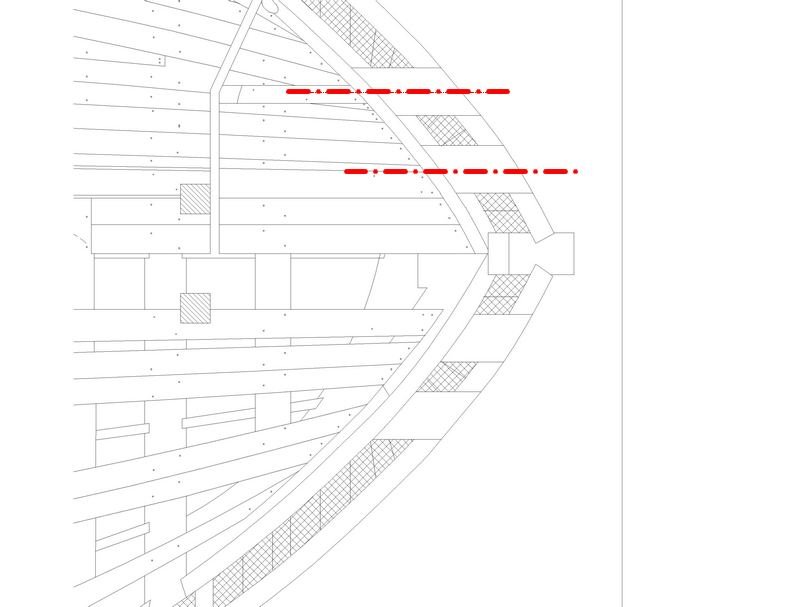

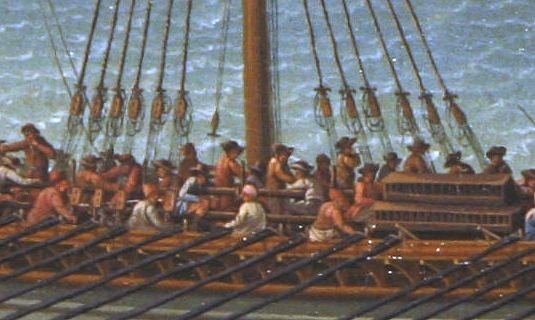

Hello, Concerning the height of Le Mercure deck under the forecastle, I checked in the monograph and, measured on the plan, it is 5 feet 1 inches (0.325 m French feet) from plank to plank. This gives a height of 1.68 m. In his "Traité de Construction" dated circa 1730, the period that interests us, Blaise Ollivier gives, for merchant ships, a height of "4 feet to 4 feet 10 inches / 5 feet above the deck" (still French feet). And this height is also present in the description of small frigates. Jean Boudriot therefore applied the current practices at that time to make his drawings. Often, information from the past surprises us and we tend to think of an error. By cross-checking the data, we realize that this is not the case and above all that our mind is not adapted to the criteria of the time. I think you have been badly advised because there is documentation on the frigates of the time much more suitable than Le Mercure for your reconstitution. Sorry Johannes for this drift of the subject. GD

-

Hello, "Trust but verify"... First, verify your own knowledge in this field, where your culture is obviously very superficial and does not allow you to judge objectively the work of Jean Boudriot, who is otherwise recognized as one of the great, if not the greatest, specialist in French naval archaeology. Using the construction plans of a merchant ship to deduce those of a 40-gun frigate is a very hazardous venture whose credibility can be seriously questioned. But everyone has the right to be wrong. GD

-

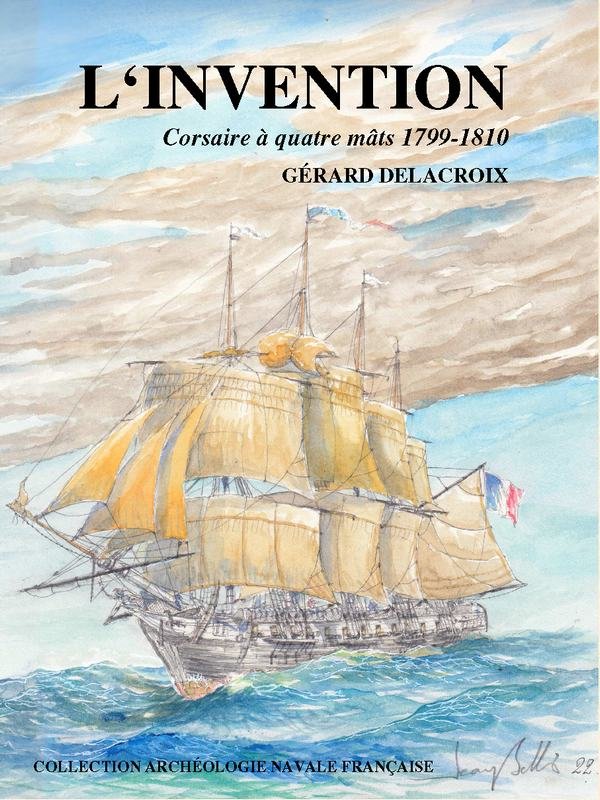

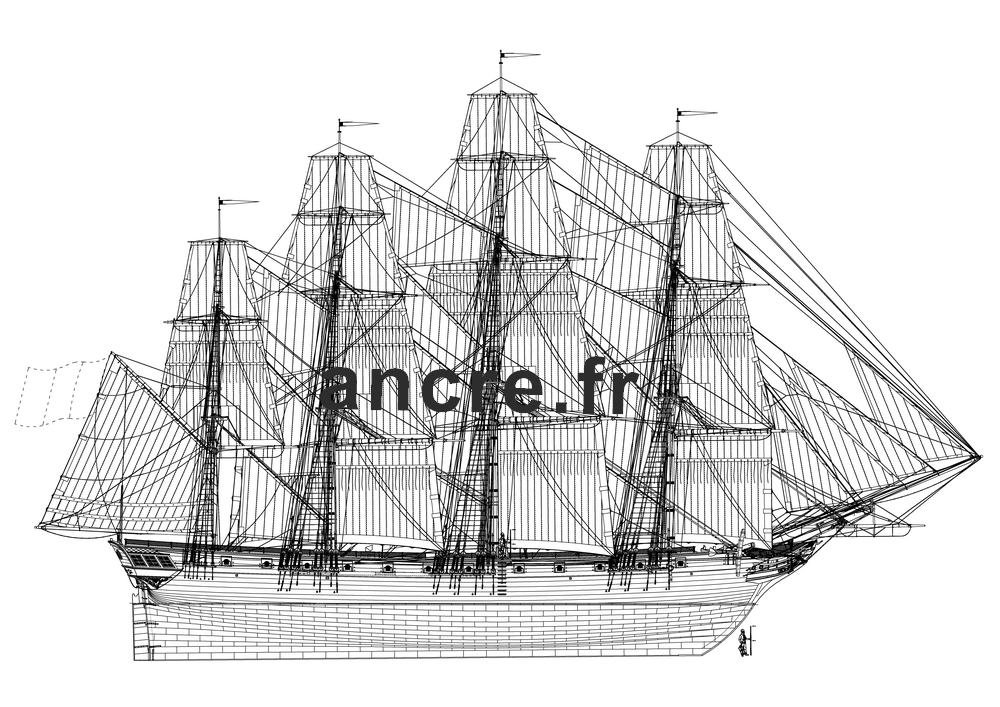

Hello, I am pleased to announce you the publication of my twelfth monograph which is about a four-masted privateer ship: "L'Invention". Built in Bordeaux in 1799/1800, she is of an innovative design for the time with her pioneering hull design with very tapered lines and her unique four-masted rigging. These major innovations were far ahead of the clippers that would follow her a few decades later. It presents the characteristics of ships specifically built to be armed as privateers. Booklet 23x31cm, 130 pages and 34 large format plans. Available in English translated by Anthony Klouda, Editions ANCRE. Gérard Delacroix

-

Hello Waldemar I stopped the elaboration of the monograph of La Néréïde because of the lack of the vertical section plan. I had adapted the sections of a similar ship, Le Jazon, and I had drawn all the frames and a little more. The idea that these were not the sections of La Néréïde bothered me a little and affected the rigor with which I work. On the other hand, monographs of this type of vessel are always somewhat identical. This is why I worked on Le Rochefort or the harbor dredger, which are more original and renew the subject a little. I put this project on hold while waiting to find sources that would have satisfied me. In the meantime, I worked on other projects that gave me much satisfaction. So there will not be two monographs and I am not collaborating with JCL, we do not have the same conception of this type of work. I would like to take this opportunity to announce a (very) big preview of a new monograph to come, that of a privateer four-masted ship, the first modern four-masted ship of 1799, that is to say, very much ahead of those of the 1850s. Michele, sorry for the drift of the subject. GD

-

Hello, I know "La Néréïde" very well because I had started a monograph on this ship a few years ago. Like all the ships of this period, the bow is wide because it has a reverse side, a feature designed to keep the waves away, to save space on the forecastle and especially to keep the catheads away from the side. It must be said that the plans of this ship do not exist, especially the vertical sections. The only drawings we have are a longitudinal section, another vertical one in the middle and the drawing of the decorations. JC Lemineur had to adapt the vertical sections of another ship to make his plans.

-

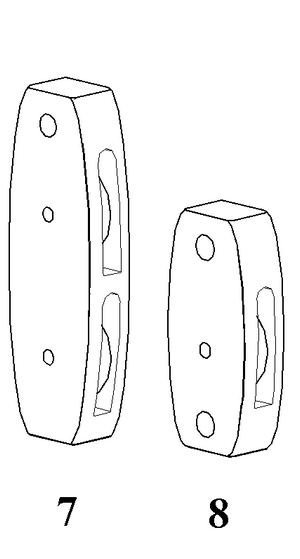

Hello, I regret to inform you that the upper blocks are installed upside down. The small part of the block should be down. Moreover these blocks are not exactly good, (see the drawing below) Concerning the rope, the running part is tied to the shroud chains, the surplus of rope is rolled on the upper block (see the illustration below). GD

- 510 replies

-

- reale de france

- corel

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Le Soleil Royal by Nek0 - 1/72 - Marc Yeu

G. Delacroix replied to Nek0's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1501 - 1750

You should read my message, #177 of this topic.- 208 replies

-

- le soleil royal

- 104 guns

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Le Soleil Royal by Nek0 - 1/72 - Marc Yeu

G. Delacroix replied to Nek0's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1501 - 1750

B. Frolich used the plans from Jean Boudriot's research on the Chevalier de Tourville, he is not a researcher nor a historian but he is a good modeler.- 208 replies

-

- le soleil royal

- 104 guns

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Le Soleil Royal by Nek0 - 1/72 - Marc Yeu

G. Delacroix replied to Nek0's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1501 - 1750

Hello, Concerning the belaiying pins, it is certain that they existed at the time of the SR, their creation does not date from 1790 as I read above. For the period we are interested in, they are mentioned in Blaise Ollivier's dictionary of construction which dates from 1729 and are obviously common practice. In French the term is called "cabillot" or "chevillot" and comes from the Provençal vocabulary "cabilhot" from "cabilha" meaning wooden peg and attested since 1283. GD- 208 replies

-

- le soleil royal

- 104 guns

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hello, Congratulations for all your work. I just wanted to point out that the yards of the galleys are not square but round. Making them square is technically useless and implies using bigger wood, thus wasting money for an identical result. GD

- 510 replies

-

- reale de france

- corel

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hello, Thank you for your compliments. The video of La Fleur de Lis is a kind of synthesis of this monograph in which I tried to describe the galleys of the late 17th century as well as possible. Nearly fifteen years of research and study (interrupted, of course, by other monographs) have made it possible to present these ships that are so particular and ultimately endearing when one is interested in them. GD

-

In France but I imagine also in the other countries of Europe and I specify well in the 17th and 18th century, it is the basic thread, taken out of the winding-machine of the spinning mill which is tarred (with hot pine tar) before before the confection of the final rope. It thus presents a brown-red color. Only one thread is not tarred in the final rope, it allows to recognize the ropes belonging to the king. The threads of the white rope are not treated with tar at all, so it keeps the natural color of the hemp. It is called "white" in comparison with the tarred rope which is dark. In big ships, only the wheel-rope is made of white rope because of its resistance and the confidence that one grants to him.

-

I can assure you that what is called white rope in the 17th and 18th centuries is indeed a hemp rope without tar. No marine rigging treatise of that time mentions linen rope. The process and considerations I have written about are well described in the texts about galleys.

-

I was referring of course to the galleys of the "modern" era, i.e. the 17 th and 18 th centuries. Homer's galleys are far too old for us to know much about their technical features.

-

Hello, Except for the anchor ropes and the shrouds (I'll spare you the Mediterranean terms), the rigging of the galleys is exclusively made of high quality natural hemp and not tarred. The process of obtaining hemp fibers is more elaborate and results in more refined ropes, with longer fibers and less dust, wood remains or little oakum. This rope is called "white rope" in opposition to the tarred rope which is dark. This white rope is obviously not white but straw colored as it has been said. The white rope is imperatively used for galleys because it has an advantage: its resistance is one third higher than the tarred rope or, if you prefer, a tarred rope loses one third of its resistance by the tar applied to it. This implies that for equivalent strength, a white rope is less thick than a tarred rope and therefore lighter and, as in a galley, the weight and strength is very important given the size of the sails, white rope is preferred. The galleys do not sail in winter (only from May to November) which avoids the problems of bad weather on the not tarred ropes. For the chebecs whose rigging has approximately the same characteristics although of lower size, I think that the same type of white rope was used. GD

-

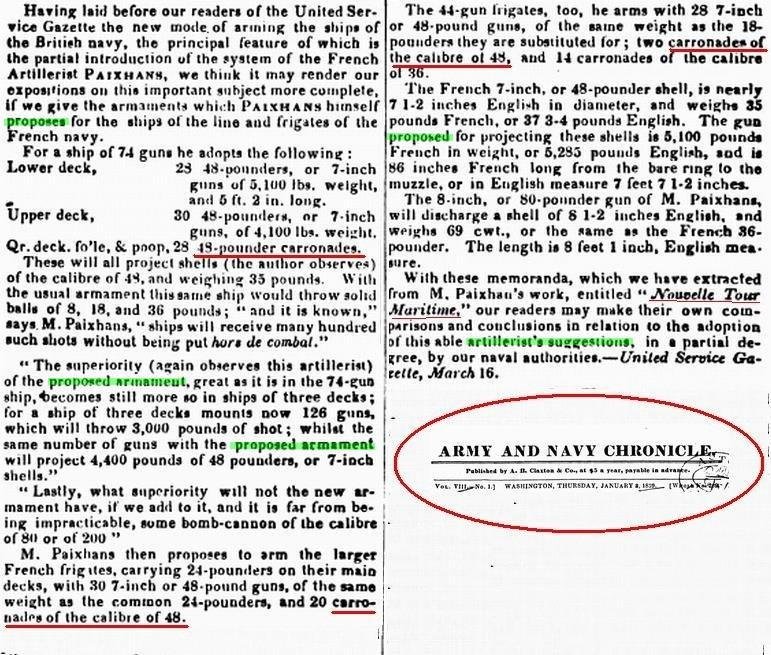

Hello, Concerning the calibers, at least in the French navy, to make it simple and in fact, without mentioning the aborted proposals: The denomination of a traditional gun until the arrival of howitzers is done by the weight of the ball it is capable of firing. For a 36pdr cannon for example, the ball weighed 36 French pounds (old pounds of 0.489 g) thus a weight of 17.60 kg. The gun is thus called: "canon de 36 livres, term shortened to "canon de 36" or abusively "canon de calibre 36", abusively because the true caliber concerns the diameter of the bore which is never mentioned. The classical calibers were 36, 24, 18 for the "big" calibers and 12, 8, 6 and 4 for the "small" calibers. The 48 is exceptional and very rare, the very small calibers of 3 and 2 are used by the civil navy. For the carronades it's identical, a 36pdr carronade fired at the beginning, in the 1780's and then named "obusier de vaisseau", shells of the same diameter as the 36 cannonballs, then, in front of the difficulty of implementation of the shells not very advanced at the time, the shooting was limited to the real 36 cannonballs and to the grapeshot. The carronades are declined in several calibers, 36, 24, 18 and some 12 caliber in the civil navy and the privateers. When the howitzers were admitted in the navy in 1827, they were named by the diameter of the bore to simplify the terms, first in inches ("canon obusier de 80 : 8 French inches bore) then in cm (canon obusier de 22 : 22 cm bore). The howitzers will then be declined in several calibers and named according to the diameter of their bore (canon obusier de 16 ou 27...) with variations according to their shape. Several proposals, tests and full-scale trials were of course practical, but in reality, the navy's artillery was basically summed up in this quotation. So, to answer the question : 36pdr carronade = carronade of the calibre 36 = carronade of the calibre #6.5 inches, the last denomination is not used. And I remind that the 48pdr carronades have never been admitted in the French Navy, which confirms that the text quoting Paixhans published above is indeed a proposal resumed without follow-up. GD

-

@ Lieste Obviously, we are not talking about the same things. @ Thanasis The text concerning the French naval artillery is a theoretical proposal by Lafay, a proposal which, like many others in the navy, was not followed up. As far as I know, there were never any 48 carronades in the French navy, at best only a few 50pdr guns in 1849.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.