-

Posts

1,763 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Mark P

-

Good Evening Siggi; This does not change anything for you, but I have been looking further into the origin of binding strakes. The contract for Edgar, dated 1666, specifies that 'the gun deck shall be laid with good three inch plank, and one strake of four inch next to the carlings [hatchways] to run fore and aft'. It is not stated that the thicker strake will be let into the beams, but it would be an awful trip hazard if this is not done. So binding strakes were in use long before Blaise Ollivier states that they were not. Presumably, at least in the royal dockyards, this was left to the master shipwright. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Siggi; Blaise Ollivier was a French shipwright sent by king Louis to investigate English and Dutch ship-building methods in 1737. He wrote down his observations, which were published at the time, and later re-published by Jean Boudriot. The italicised note on the left appears to be a quote from the original book. HIs comments on the lack of binding strakes in English ships are true, it would seem. However, it is important to remember that 17th century English ships had two long, continuous carlings along the deck, forming the sides of all the hatchways. This would have made binding strakes un-necessary. Contracts of the time make it clear that the deck plank was all of the same thickness, but that the first strake against the hatchways was to be of oak, even if most of the deck was deal. Later contracts and specifications, those for Warspite of 1755, and Marlborough of 1768, specify that the strake next to the hatchways is to be let down 1 1/2" into the deck beams, to form a binding strake. There must therefore have been a period of time, once the 16th century's full-length coamings were no longer fitted, and before the 1750s (or somewhat earlier) when no binding strakes were used, as Blaise Ollivier comments. I do not have any contracts between 1702 and 1755 which would help to establish the date when they were introduced, though. Chuck: the ogee curves to the underside of the hatch ledges are also featured on the model of the 44 gun Endymion of 1779, and on the steps up from her gangways. See picture below (the one showing this in the hatchway is rather blurred, due to low light and no flash allowed) All the best, Mark P

-

Lovely work Siggi; Well done indeed; a lot of great examples and ideas to absorb. To answer your question above, the long plank each side of the hatchways was called the binding strake. It was 1" thicker than the other deck planks, and was let down into the top of the deck beams by 1". As this is a lot of work for something unseen, it is rarely done on models. All the best, Mark P

-

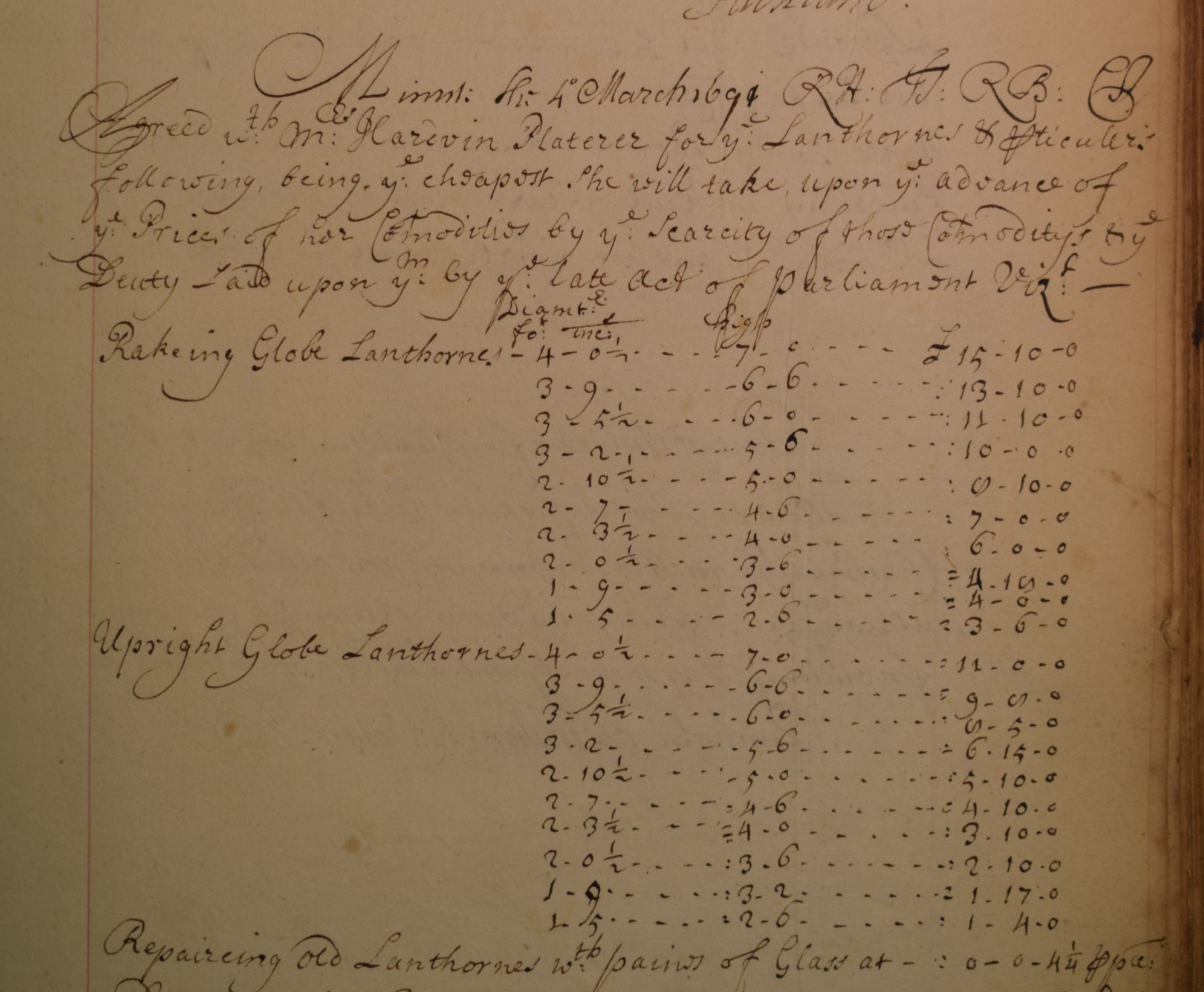

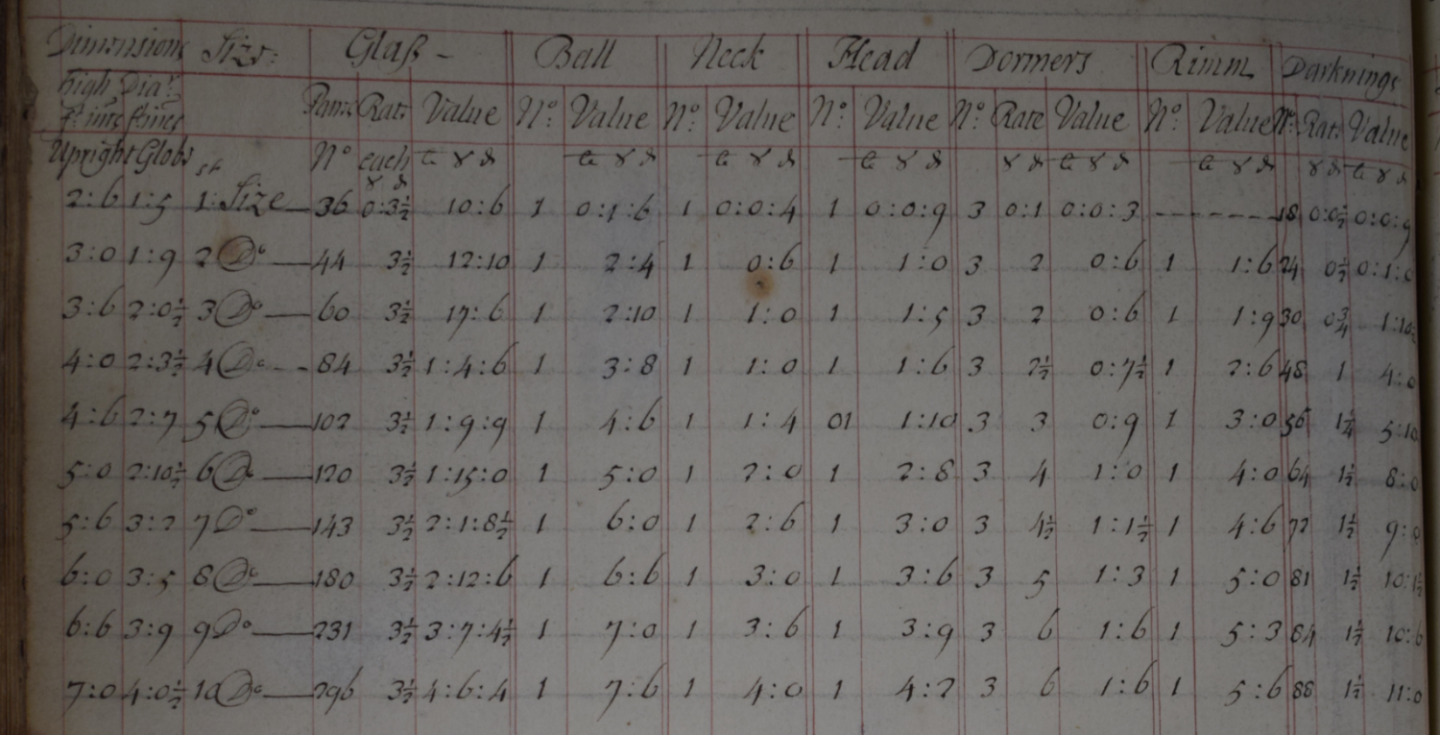

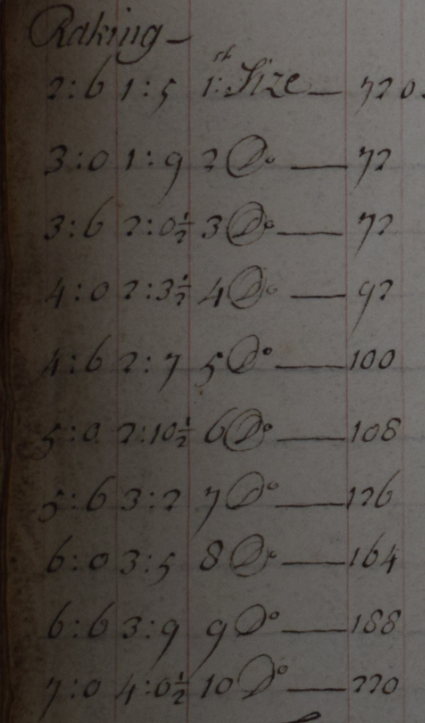

Good Morning Michael; See below a photograph of a document dated 1690/91 which lists all the sizes of globe lanterns to be provided for ships. I can't tell you which size would go with which rate, but you will know that the largest 7ft x 4ft (and a half inch) will be for first rates. Although this does not give top lanterns, other info I have states that for first rates with a poop lantern of 7ft high, the height of the top lantern will be 5' 7" so work in the same proportion and you won't be too far off. All the best, Mark P The below extract is from the 1680s, and gives the number of panes of glass for each lantern, although, as there are 296 in the largest size, I doubt that you will want to go to this much detail! The largest raking lantern has 'only' 220 panes, interestingly.

-

Good Evening Mary-Ann; As Chris said above, sorry for your loss. If it helps at all, in my experience all modellers would like to think that their carefully accumulated tools, and bits and bobs, would end up in the hands of someone who will use and appreciate them. If you can clarify what is included under the paraphernalia heading this would also help. Are there any kinds of power tools, for example. Unfortunately, in both England and Scotland, I believe, ship modelling clubs are not as common as they once were. However, I don't doubt that if you can supply a bit more detail of what is included, someone will be glad to have it. All the best, Mark P

-

One small point regarding the use of European boxwood logs: the trees are normally not large (not the ones that survive in most areas, anyway) and rarely contain much in the way of long straight pieces. Although it is easy enough to obtain a good number of pieces which are certainly straight enough to provide long planks, a good many pieces will have curving grain, which is very useful for a framed model. Whilst it is not necessary to have the grain following the curves of the timbers, it will create a stronger structure if this can be done. All the best, Mark

-

Dave: thanks for the advice; I will do as you suggest with anything a bit dubious. Some of the boxwood I have now had for over 5 years, so there shouldn't be a lot of life left in the fungus now. However, I have always burnt all the bits I did not keep, and all the sawdust too; so that will hopefully minimise any risk. Andrew: the pictures posted by Vahur certainly look absolutely identical to the logs I got in England. It looks like Buxus sempervirens to me. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Afternoon Al; Thanks for the explanation of what you need; sounds like a decent project, certainly. I did not keep a lot of stock at 1" thickness, only some for some carvings, but I will look through and see what I can find. Dave's comment in the previous post is worth noting. Some of the boxwood I have has similar grey or even black markings in it, often rendering it unusable in terms of colour. Not sure if the fungus is still active, though, or if it dies once the wood dries out. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Al; I have a reasonable selection of timber now, most of it well-seasoned; however, much of it is relatively small stuff, fine for model ships, but not so good for furniture perhaps. If you need long lengths for inlay strings or bandings, I don't really have anything suitable. For repairs to marquetry work, I might be able to help, but I would not want to part with much of it, as I cannot be sure of future supplies! All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Gentlemen; Just to add a bit of further information on studding sails, when these were set, the windward ones were set aft of the 'main' square sail; and the leeward studding sails were set forward of it. This was to prevent the wind escaping between the sails. Changing tack must have been a really time-consuming business! Presumably, the studding sails were only set when there would not be a need for regular changes of course. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Gentlemen; It was usual to walk along the bowsprit. I have seen an example (can't remember if it was a model or a draught) with cleats along the top to provide a more secure foothold. That's a nice model, Druxey. All the best, Mark

-

Why masts are square at the top?

Mark P replied to Tommy Vercetti's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Good Evening Tommy; Masting ships is quite a wide topic, and the exact reply depends upon the period in which you are interested. If you are prepared to purchase some good books to learn from, then I strongly recommend the following: For merchants ships, look for 'Masting and Rigging the Clipper ship and Ocean Carrier', by Harold Underhill. For English warships, look for 'The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War', by James Lees. There are other books for ships of other nations. All the best, Mark P -

Good Evening Everyone; There has been quite a lot of discussion here about the colour of lanyards, and I am surprised that nobody has suggested referring to the works of the various marine artists who flourished for at least four centuries and recorded the actual things which they saw. Below is an extract from Henrik Vroom's painting of the Prince Royal, with nice dark deadeyes and lanyards. Back then, interestingly, they were called 'deadman eyes'. A look through a book showing work by an artist working in the period in which one is interested would surely be a good first port of call for anyone seeking further information. On a slightly different topic, the deadeyes of royal yachts were sometimes gilded. All the best, Mark P

-

Manning the capstan

Mark P replied to dafi's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Good Evening Dafi; I have not read any contemporary references, but C. S. Forester, in his 'Hornblower' books, made references to the marines helping with tasks where minimal sailor skills were needed. He knew his stuff where the Navy was concerned, it seems; so when this is confirmed by a contemporary print, I would take it as a definite. Note that the outermost person on each bar is a sailor. An interesting print, thanks for posting it. All the best, Mark P -

Good Evening everyone; Thanks Marcus, I will see if I can get a copy of this. I believe that you will find that the two volume set is known as the Robinson volumes, as they were in large part put together by Michael Robinson (d. 1999) who worked at the Maritime Museum as keeper of the pictures, and was an expert in the works of the Van de Veldes. There is a set in the British LIbrary, and probably others in many other places; the second hand value of these is rather too high, unfortunately. All the best, Mark P

- 7 replies

-

- Marine artist

- Dutch

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Good Morning Michel; The usual practice when sails were taken down from the yards was as follows: On lower yards the sheet, tack and clew/clew garnet line, which are all attached to the clew of the sail, were shackled or lashed together in the raised position where they would have been when the sail was furled, or hauled up tight to the clew blocks on the yard. On the upper yards the sheet and the clew lines were similarly fastened together in the 'sail furled' position. Buntlines, leech lines and slab lines were made fast to the jackstay, if fitted, or to their lead blocks on the yard if no jackstay was present. For headsails, the halliard and downhaul were made fast to the traveller, or hitched to the lower end of the say. I do not remember where I read all this, it was a long time ago, so I cannot give the name of the book it was in, unfortunately. I attach below a photograph of a model of the Yarmouth, an 18th century model in the NMM. If you look carefully at the mainyard, you will see the position of the ropes normally attached to the mainsail. Ignore the yardarm tackle which is stowed horizontally and made fast to the futtock shrouds or stave. All the best, Mark P

-

Definition of 'Single' WRT rigging/ropes

Mark P replied to BANYAN's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Good Morning Pat; I think that you will find that the single refers to the possibility that some large ships in the 19th century had inner and outer lifts, to cope with very long yards. All the best, Mark -

Ships name 1700s

Mark P replied to DaveBaxt's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Good Evening All; As Druxey says above, the Navy Board ordered that the ships of the Royal Navy should display names on their upper counters. This practice was discontinued not long after, as it was felt that letting an enemy know what ships he was facing might be disadvantageous. Below is a photo of the stern of the Ajax, a 74 launched in 1767 and sold out of the service in 1785. She took part in several notable battles, and the model could commemorate her building, or one of these. The well-known model of the Bellona, also in the NMM's collections, has its name in similar manner on the upper counter. All the best, Mark P -

Good Evening Toni; I have the first Sea Watch volume (the second was similar size, with a couple more models, I believe) and the differences are notable. The new book is larger and with at least double the number of pages. As there are pictures on every page, there must be a lot more pictures than the earlier volumes have, although I have no intention of counting them. I don't think that the number of large 'Admiralty' and 'Georgian' models covered is much greater, although there are certainly some new ones; but rather that the artwork and additional items are much greater, as also is the section on small boats and prisoner-of-war models. All the best, Mark P

-

Back in February, I made an advance order for a forthcoming volume about the Kriegstein Collection of 17th & 18th century ship models, to be published by Seaforth Books. After several postponements this was finally published at the end of September. There have been two previous books published by Seawatch Books on this subject, both of which were highly informative and desirable works. Owners of these books will have some idea of the quality of both the Collection, and the photographs of it; but this latest offering is larger, has many more pages, and gives greater details of other areas of the collection than has been the case with either of the preceding volumes. The Kriegstein Collection is the largest collection of contemporary 17-18th century models in private hands, and consists almost entirely of museum-quality examples, superbly made and decorated. Each model is photographed many times, and is well-described, with a history of the model, its acquisition by them, and reasons for its stated identification, where known. The two brothers Kriegstein, who along with their supportive father, are the owners of this beautiful collection, take their role as guardians of such valuable heritage very seriously. Their admiration for the models, and for the craftsmen who made them so long ago, is clear to any reader; as is their mission to preserve them, and to make as much information as possible about them available to interested parties. The collection also contains many valuable and beautiful artworks by top-drawer maritime artists, such as the Van de Veldes, as well as some very interesting ancillary items; and a good number of prisoner-of-war models from the Napoleonic era. The photgraphs throughout are in full colour, and are of a good size, with many close-up details of each model. The book's overall size is 293 x 285 x 30mm (11 1/2 x 11 1/4 x 1 3/16 inches. It has 288 pages, including notes and an index. The recommended price is £50. The first 14 chapters are about models of English warships; there follow two on French models, and then a model of the American ship 'Franklin' of ca 1800. Three sectional models of bomb vessels follow, then six models of various ships' boats, including several with detailed figures of the crew on board. One of these is a troop transport, for landing soldiers from ships, and has no less than 16 oarsmen, a naval officer, 38 redcoats, a sergeant and two musicians, all with their uniforms painted in detail. There follows a Dutch state yacht of ca 1690, a model carving of the figurehead for Royal Caroline, and another for the Queen Charlotte of ca 1784. A model of the Victory's foremast with battle damage as received in 1805 is next, then two chapters on the various artworks in the Collection. Prisoner of war models follow these, and the book finishes by covering 'Care and Conservation', and 'Fakes and Forgeries'. Their latest acquisition, a previously unknown late 17th century model of an English ship, is covered in an appendix. This model is still in France, and is awaiting an export licence. It is very interesting in that it shows how much some models have been altered by owners during their long lives, acquiring extensive additions which are completely anachronistic, and obscure the original model to a remarkable degree. If previous models are any indication, this model, once safely in the brothers' hands, will be lovingly and carefully restored to as close to its original appearance as can be achieved; as its new owners have both the drive and the resources to see this accomplished. This is a beautiful book, and I thoroughly recommend it to any member with more than a passing interest in models of this period. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Dave; Strictly speaking, the bolts would not be visible, except perhaps at the extreme ends of the channels. This is because a 'cover-strip', a separate, long thin piece of timber with a simple moulding on it, was nailed over the outer edge of the channels. The chains themselves were rebated into the outer edge of the channel, and the cover-strip was then fitted over the top. Also, if you want true verisimilitude, the channels are actually tapered, with the outer edge around 1" to 3/4 " thinner than the long edge against the hull. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Ian; One thing which may be worth knowing if you have not yet started making all the hammock rolls, is that once the hammocks were stowed in the netting, they were covered with tarred or painted canvas, usually black or very dark grey, to keep them dry. This was certainly done in the Royal Navy, maybe not for French ships. Sailors did not want to sleep in soaking hammocks. Most likely, the nettings were lined with lengths of canvas, like a long trough, so that the hammocks were stowed inside it. Once the netting was full, one edge of the lining could be turned over the top and tucked down behind the other side, to create a seal. All the best, Mark P

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.