-

Posts

690 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Ab Hoving

-

Thank you for the undeserved praise, Justin. I doubt that there is a consensus on this side of the ocean for what I have done. What I think is interesting in your answer is that you mention curators who want things to be like new. Over here it is most important that the age of the object shows, being restored or not. A restorer is much more criticized for working too clean than for delivering a product that shows its age. Especially with metal objects it is hard not to make them too shiny. I remember a large brass quarter of a dry-dock which had to be restored and was therefore placed a few days in a reservoir with water with a mild cleaning agent. It came out shining like gold and that caused something like a panic under curators. As an experiment we once treated one of the pewter candlestick holders found on Nova Zembla, where they were left by discoverer Willem Barentsz in 1597 when he stranded there on his way to China through the North, with a very mild electric current in a basic bath (we call it electrolyse, but I can't remember the English term for it). It came out quite nice and clean, but panic again... I agree that for students it is important to know that every step they take should be considered over and over again, so you are doing your teachers job perfectly. The proces is to be reconsidered in every phase. Dogma's are good als long as one can deviate from them. I sometimes was jealous at my collegues of the painting restoration workshop one floor below my attic. They have the choice to select a method from a limited number of regular treatments, all tested and scientifically researched. In my field of work every restoration was a new experiment. Every object asked for its own treatment and there were a lot of methods to choose from. Many restorations were pure inventions, which made the work challenging every single day. Never a dull moment. Thanks also for the clips of the painting restorers. To many people the treatments seem extremely rude and messy, but as could be seen, there was no harm done (although I doubt I would have delivered the object as new as these ones. But fortunately I was not a painting restorer ). It is a beautiful profession and I enjoyed my existence in the museum every single day. As for the figurehead: we deliberately did not fill all the cracks and kept the guilding a bit 'damaged', as you can see here: https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/zoeken/objecten?q=boegbeeld&p=3&ps=12&st=Objects&ii=5#/NG-NM-11549,29

-

I was afraid this was going to happen when I first saw this thread and I must say I am rather unwilling to jump in, because I cannot find my way through all these well-educated opinions and propositions. But as there seems to be no escape: here is my 50cents opinion. If I learned one golden rule about restoration/restoring, it must be that there is no golden rule. Hundreds of historical objects passed my hands in the 23 years of my active career in the Rijksmuseum and even looking back at all the processes of recovering or maintaining original objects I still cannot find a general line in the treatment of all of them. It is an unflinching law that everything that exists will disappear over the years and we can only try to stall that proces. Of course I must have 'repaired' some ship models in a way some of you would call a crime. But hey, what is the point in finding a beautiful but dismantled 17th century hull of a very rare 40-gun man-of-war and leaving it in that state, if such a model is needed in the museum's presentation. Is it allowed to take off the 20th century paint with which it was mistreated and rig it in the way how it to my best knowledge should be done? Of course I did all that and I'm proud I did. On the other hand I saw many ship models pass my workbench of which the running rigging was deteriorated beyond repair, but which still had a perfect standing rigging. I would be mad if I replaced both parts of the rigging. Whatever is still intact, I keep it that way. Fortunately I am a lazy person and nothing is better for a historical object than falling into the hands of a lazy restorer. But anything that is literally falling to dust has to be replaced. We had models in the depot which we passed on tiptoes because any shock would cause rigging parts to fall off. There is something I have to add here. Being a conservator in a museum mainly presenting art objects I always tried to fight for my own place between my respected collegues. A ship model in my opinion is not a work of art, although out of admiration we are most willing to judge it so if the build was done in exquisite way. But in reality it is a depiction of something technical. It shows for instance how the rigging was done, which allowed the vessel to sail the oceans. If such parts turn into dust (and I have seen many examples of that, carefully rubbing it between my fingers and ending with nothing but dust) and you want to maintain the intention of the maker, showing a working rigging, what harm have you done replacing the missing part with material as close as you can get? (The Victory in Portsmouth seems to be 'renewed' for over 90 % so I was told. Should all the rotten pieces have been still there, sooner or later we would have ended up with a pile of debris.) What is always interesting to see is the attitude of the curators. If we lived in a perfect world the curator was to be the one to say yes or no to a restoration or a technique. In practice dealing with objects is something completely different from what an average curator has studied. Doing archives was his training, not dealing with objects. So what happens is that the conservator (or restorer if you like) makes the decisions and carries them out. Next the curator ceremonially cries out about the mistreatment of the object, immediately followed by its placement in the showcase to show it to the public. I experienced this literally with an old figurehead of a knight in armor which was in a terrible state. Me and my co-operator closed the many cracks, re-applied the guilding and paint (after intensive research), added missing wooden bolts and repaired the not-original stand, at the same time suggesting a better solution to present the object. For a short time we were the talk the town and the next thing that happened was the installation of the object as it was in the hall as an eye-catcher. It is still there.... The bottom line? There is no golden rule. I applaud every researcher trying to find solutions to maintain old objects that show their age and I am most willing to apply any solution to solve problems without intervening in the object, but I am not a chemist, I only know a lot about ships and their ins and outs and I would be lying if I denied that every object I had in my hands has taught me something. The museum allowed me to have an extensive library both on technical ship-matters and on conservation techniques and I have always loved to find a happy marriage between the two. If you want one unavoidable rule in this matter it must be a deep love and respect for the object, but I'm sure every participant in this discussion feels that too, with apparently totally different outcomes.

-

Beautiful Drazen, you both are master model builders! Ab

-

Hello Eberhart, Thank you for enlightening this peculiar thread of which the content seems to wonder into various directions with a nice view on Amsterdam in the 17th century.:-) This is surely a pleasure vessel. We know it under the name of 'kopjacht', a name I cannot explain. It is more often depicted on paintings of special occasions on the water, like this one, dealing with the visit of the Czar Peter the Great to Amsterdam in 1697-98. Another attractive type for model building...

-

Jan is 100% right. Traditional shipbuilding is not an invention. It is an endles developing process that goes back to the bronze age (3000-800 b.C.), consisting of small steps forwards (and sometimes backwards). It took ages before it got to what is described for the first time in Dutch literature in 1671. There were no alternatives though. Because the method of designing ships hulls on paper was not invented yet (here you really have an invention) there was no possibility to do it frame-first. Traditional rules-of-thumb were all our ancestors had. Now is that impressive or not?

-

Congratulations with your work Glenn. It must be years ago that we met in College Station. Keep good memories of that event. Ab

-

Twist in the lower shrouds/ratlines

Ab Hoving replied to Ronald-V's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

In my opinion you don’t have to remove the ratlines to tighten the shrouds. I always leave my lanyards more or less loose until the ratlines are done. Then you can easily tighten them, taking care that the shrouds are stretched in an even way. -

Hello Eberhart, I only recently found out that you are chairman of the Arbeitskreis Historische Schiffsbau in Germany. As you know I sometimes contribute to its magazine Das Logbuch, invited to do so by the editor Robert Volk. You seem to lead an extremely active life. 🙂 Houtboard: I am not an expert on the fabrication of it, but I suppose even wood-dust is used. It causes the material to become more or less 'flexible'. You can make concave shapes by pressing it with round surfaces, like a spoon or an iron ball. It can also be filled and sanded, but I only use it for covering up the skeleton of a planned ship model. You are right that the result is not exactly crispy and clean, but I don't care, as I cover it with self-adhesive plastic strips, which improves the result. In cases where sharp contours are needed, like the wales of a ship (the most important part as it goes for catching the right sheer) I use 2 mm thick polystyrene. Nobody ever told me that you have to stick to paper once you started building in paper.... Compared to what I see accomplished here on this forum, I am not exactly what I call a good model builder, because in fact I have no interest in finished models to put them on the mantel shelf. Sometimes I give or throw them away, sometimes I sell one, I even considered burning some, as they take a lot of space and only gather dust. I only build because I want to learn something. For me model building is a technique I use, a way of scientific research, building itself is never my purpose. The end result is always something different from a ship-model, like knowledge, which is the reason why I am often reviewed by historians and replica builders. I have worked in wood all my life, but getting older, I am running out of time, so I switched to an easier material, being able to work faster. Having explored in model scale the way 17th century ships were constructed, I now turned to the outside looks of the vessels, trying to make them look as real as possible, so a Photoshop painting can be made in a convincing way. This leads to the conviction that too small details are totally nonsense (for me) to apply to a model, as a model can be compared to a real ship seen at considerable distance. From a hundred meters I cannot see what sort of head the nails of a ship have, so why should I bother to model them? I don't make real ships, they are only models, probably the most useless objects in the world... All this beside of the fact that I am notoriously lazy...:-)

-

Hello Jan, (funny how two Dutchmen have to communicate in a foreign language through an American forumsite :-)) In Dutch it is called 'houtboard' and I buy it in Amsterdam at an art-suppliers called Van Beek on the Weteringschans 201. It comes in various thicknesses. I know that local art suppliers don't sell it because it's an 'old-fashioned product', replaced by many more sophisticated materials, which are of course all useless for our purpose. Another problem is that it is so cheap that sellers are not very interested in holding stocks of it. Maybe you are planning a trip to our capital anyway to visit the Rijkmuseum, located at 400 meters from Van Beek....

-

And here is a picture of us (rigger Floris Hin and me) finishing the re-rig of the model in 2012. The model was relocated twice, once in 2007 and once in 2012. Dismasting took 2 1/2 days, rigging 4. I made a u-shaped construction to take off the masts with all its rope work and sails together, with the shrouds temporarily attached to the legs of the U and the mast tightly connected to the middle piece. Those were the days...

-

Thanks for sharing Kenny. I'm sure many people will be very glad to see all this. I hope you also enjoyed the 'special collections' with all the ship models well hidden in the basement of the museum?

-

It seems to me that you made a wrong choice. If it is a pirate ship you want to model, forget these big monsters. Pirates were not so well organised that they could manage big ships. You better find a smaller ship, about a hundred feet. That means of course that 24 pound cannons are a bit over the top. Fortunately you can simply scale your cannon down and you will never see the difference. If it is the 17th century you are looking for, you might consider the Heemskerck, Abel Tasman’s ship when he discovered New Zealand and Tasmania in 1642. His 100 feet long ship might have been suitable for a pirate. If you are interested you can send me a PM and I will send you the draughts.

-

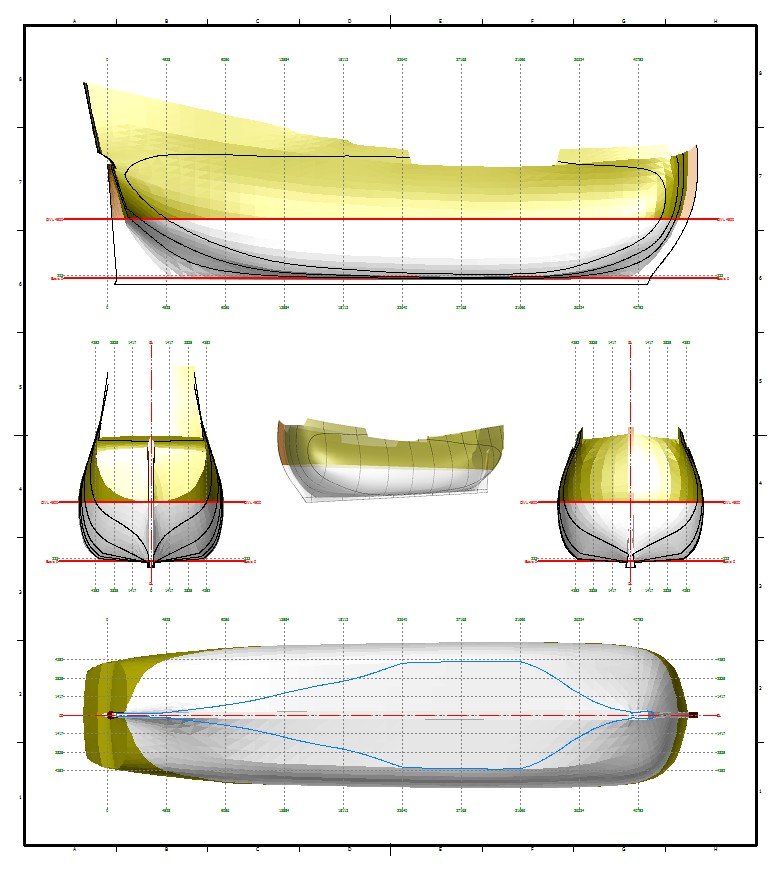

Hi Marcus, You must have a lot of time at your disposal. If I look at your plans, you could easily fill two lives with them. 🙂 There must be plans for the William Rex, but I don't have them. About ten years ago I let a group of students do calculations on the ship because I did not trust the shape. Too little volume below the waterline. From this project (it turned out I was right) there must be a report in the museum. I will ask and come back to you about this matter. As for the rigging of 18th century Eastindiamen you might be interested in a rigging plan for 160 foot retourship I reconstructed from a VOC document from the middle of the 18th century. It was published in a book about the archaeological finds of VOC ships, the Hollandia Compendium, published by the Rijksmuseum in 1992. The plans might reasonably fit the Valkenisse rigging. The oldest VOC retourship of which plans have been published was Prins Willem (1651) by my predecessor Herman Ketting. There is a book from 1979 and there are plans, but I don't know how to get them. Perhaps other members can help you out, for instance Amateur? Apart from the plans for Valkenisse (1717) I don't know of any published plans, but I do have plans made after the 1697 Resolution, after which I started a model some time ago, but never finished it. I have no recent pictures of the state it is in at the moment but I can tell you, it takes a lot of study to get even this far. Anyway, if you are interested in the plans you can have them, send me a PM. Here is a preview: I hope you know what you are looking at. As I said, your plans will take a double life-time to execute.....

-

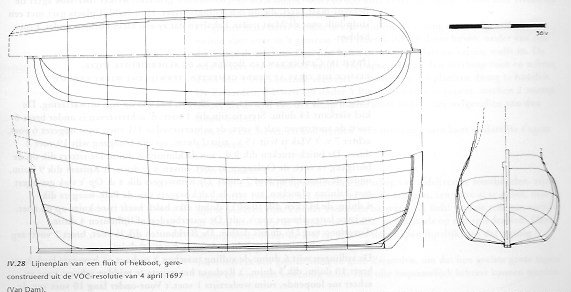

A hekboot was a hybrid ship, with the lower part lend from the fluit and the upper part from a pinas. Think of it as a fluit with a transom. The combination produced a wide merchant vessel with the accommodations of a pinas, like a wide captain's cabin. The only draught there is of the type is the elementary drawing I made from data from Van Dams book "Description of the East Indian Company" (1701). I add it here, but you have to a lot of imagination to make a model out of it.

-

I'm happy to take part in any discussion about shipbuilding, as long as you don't expect me to have all the answers. The contrary is true. The more I look at the subject, the less I understand. 🙂

-

Marcus: You cannot tell the difference. It is a matter of background. Apart from the big 'retourships' the VOC also built small warships, which they called 'yachts'. In admiralty circles such ships would be called 'frigates' and they looked very much the same. The only difference is in the decoration of the stern. Usually a frigate was a man-of-war with less than 40 guns. Jaager: I have a document written by Charles Bentam, the English shipbuilder who worked for the Amsterdam admiralty in the second quarter of the 18th century. He describes his method of design and starts with the location of the frames. The location was important for where the gun ports were placed. He is surprised that the Dutch cut their gun-ports after completion of the framing of the upper works. The conclusion must be that the idea of sliding frames was no option. The philosophy about how a ship should move through the water differed from location to location and from time to time. In the 17th century the Dutch idea of how a ship should sail was that it should more or less slide over the water, instead of cutting through it. The comparison with a duck's breast was made. This way of design produced very 'dry' ships, totally different of what we see in the age of the tea clippers, which were sharp and sailed more under than on the waters.

-

Peculiar. Van Yk describes the location of all of the four frames (of which two of them were identical) and does not mention the possibility of sliding. He does give a trick to derive the aft one from the fore one, counting in the amount of greater depth at the stern and the narrowing of the width of the hull. Archaeologists found a lot of traces and proof for shell-first building in Dutch shipwrecks, but so far I have never seen a report dealing with a typical 'Van Yk'-method built ship. There are so many questions to be answered and there is so little knowledge on the subject... The more I learn, the less I know.

-

I totally agree with you on the last point. For me it even the question if Van Yk used a mold loft floor at all. In my opinion it is very well possible that the shape of the four initial frames was drawn on the wood right away, without a drawn design on paper or on a floor. Rules of thumb work that way. Taking the shape for a new frame-part was done from the splines that that were fastened to the four frames. Even after 1725, when the first Dutch war ship (Twikkeloo) was built on the Rotterdam admiralty wharf by Paulus van Zwyndregt after a pre-drawn design, the same yard only placed 10 or 12 pre-drawn initial frames on the keel and proceeded taking the shapes of the missing parts from the ship itself. The advantage was a obvious: The demands for the quality of such a frame-part was much lower that whatever was made after a drawing. So the hybrid method of working after a drawn design and the shell-first method actually continued in the practice on the yard for ages.

-

My views on the matter of the development of shipbuilding in Europe is extremely limited. I have only been busy with Dutch efforts. There are very good studies done, for instance by Larry Ferreiro: Ships and Science: The Birth of Naval Architecture in the Scientific Revolution, 1600-1800 MIT Press 2006. ISBN 9780262311472 OCLC 743198863 Bridging the Seas: The Rise of Naval Architecture in the Industrial Age, 1800-2000 Mr Richard Unger has written something about the subject too if my memory serves me well: Dutch Ship Design in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (1973) Dutch Shipbuilding before 1800: Ships and Guilds (1978) Ships and Shipping in the North Sea and Atlantic, 1400-1800 (1997) I think you can find answers to your questions in those books. I'm just a model builder and not even a good one :-).

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.jpg.2068e80448faa0a8347b55e06b19e25f.jpg)

.jpg.0761e084b0057632bae18470c29022ec.jpg)

.jpg.e1106bbdf0a88350bf0d54f8c580b15a.jpg)

.jpg.7da9c1fc21447b104d2a7dd9d7cb74f2.jpg)

.jpg.c2bda51212d673f463e2708814d29a3f.jpg)