Bob Cleek

Members-

Posts

3,374 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Mike Y reacted to a post in a topic:

Rare complete ship's curves set on eBay

Mike Y reacted to a post in a topic:

Rare complete ship's curves set on eBay

-

Mike Y reacted to a post in a topic:

Rare complete ship's curves set on eBay

Mike Y reacted to a post in a topic:

Rare complete ship's curves set on eBay

-

MichaelT reacted to a post in a topic:

Making reef points behave

MichaelT reacted to a post in a topic:

Making reef points behave

-

JohnOz reacted to a post in a topic:

Cut and Paste - downloadable e-book featuring the work of Ab Hoving

JohnOz reacted to a post in a topic:

Cut and Paste - downloadable e-book featuring the work of Ab Hoving

-

paul ron reacted to a post in a topic:

Copper plate overlapping (< > 1794) - lower overlaps upper or vice versa?

paul ron reacted to a post in a topic:

Copper plate overlapping (< > 1794) - lower overlaps upper or vice versa?

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Model Machines LLC – Byrnes Model Machines - All machines to be back in production soon.

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Model Machines LLC – Byrnes Model Machines - All machines to be back in production soon.

-

Cast Off reacted to a post in a topic:

Belay Pins

Cast Off reacted to a post in a topic:

Belay Pins

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Work area pictures only

-

Nightdive reacted to a post in a topic:

Shellac Cut Rate for Our Hobby

Nightdive reacted to a post in a topic:

Shellac Cut Rate for Our Hobby

-

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Seeking paint advice for Bluenose II

Admiral Rick reacted to a post in a topic:

Seeking paint advice for Bluenose II

-

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Planking precision and wood filler

Bob Cleek reacted to a post in a topic:

Planking precision and wood filler

-

Bob Cleek started following USS United States reborn , Steam Schooner Wapama 1915 by Paul Le Wol - Scale 1/72 = From Plans Drawn By Don Birkholtz Sr. , Frayed lines and 3 others

-

Beginner looking for advice on first kit

Bob Cleek replied to O-Nurse's topic in New member Introductions

I urge you to take Roger's sage advice in the post above to heart. I completely agree with his observations. If the subject you are modeling doesn't enthuse you to one degree or another through to the end of the build, the end of the build is quite likely not going to happen. As Dirty Harry said, "A man's got to know his limitations." -

Who knows? Perhaps McDonald's or another of the fast-food restaurant chains could buy and restore her to operate burning used deep fat frying oil for fuel! (Don't laugh. I know several guys who are running live steam launches or railroad steam engines on used frying oil, waste restaurant grease, and/or strained used crankcase oil. United States set the Hales Trophy record of three days, ten hours and forty minutes, Southampton to New York. The QE2 is the only transatlantic passenger liner regularly operating at present. Given her top speed, she could cross in about five days, but her scheduled crossings presently take seven days which permits a leisurely crossing with sufficient time to adjust to time zone changes without noticing them, a feature of importance to some passengers. United States could easily cross on a seven-day schedule on a directional rotation schedule in the opposite direction to QE2. It's been a long time since my father worked for decades as an accountant for American President Lines, (and myself as well in summer jobs during high school and college,) which ran premier passenger liners on the Pacific runs, but while the advent of the jet airliner ultimately knocked the slats out of the seaborne passenger trade, I believe most in the industry were rather surprised to watch the recovery and regeneration of passenger service in the form of "cruise liners" which now likely carry far more passengers than the great transoceanic passenger liners did even in their heydays. Just as there was a market for the Concorde supersonic jet, the Orient Express, and now again in the United States, certain luxury passenger railroad trains, it may be economically feasible to restore and operate the United States in luxury passenger service once again. Such passenger service is, of course, not practical as a primary mode of transportation, particularly for business, but where folks might be interested in "getting there being half the fun," it might attract a certain niche clientele that might make it pay. Who might take that gamble is another matter entirely and, as mentioned above, the Jones Act, once designed to protect American merchant marine jobs, in the end has come to eliminate as many as it once was intended to preserve and may preclude the economic feasibility of such a scheme. Moreover, the vessel is probably well-beyond her "use by" date, although I can't say off the top of my head what that regulation may be these days. Due to her age, I highly suspect she'd require some sort of licensing waiver from MARAD to operate as a U.S. flagged vessel in any event. Lastly, of course, is the fact that she is at present, from all reports, entirely stripped of all equipment, furniture, furnishings and the like and is simply a shell that would have to be entirely rebuilt to present-day standards. So, no. The dream may be a pleasant one, but I really doubt it could pencil out. If it could, somebody would have done so. In the end, there is really nothing quite so expensive, even to do nothing with. as a large vessel built to sail the seas. A ship that isn't working is a ship that is losing her owners money and that fact often warrants getting rid of them as quickly as possible once they are no longer profitable.

-

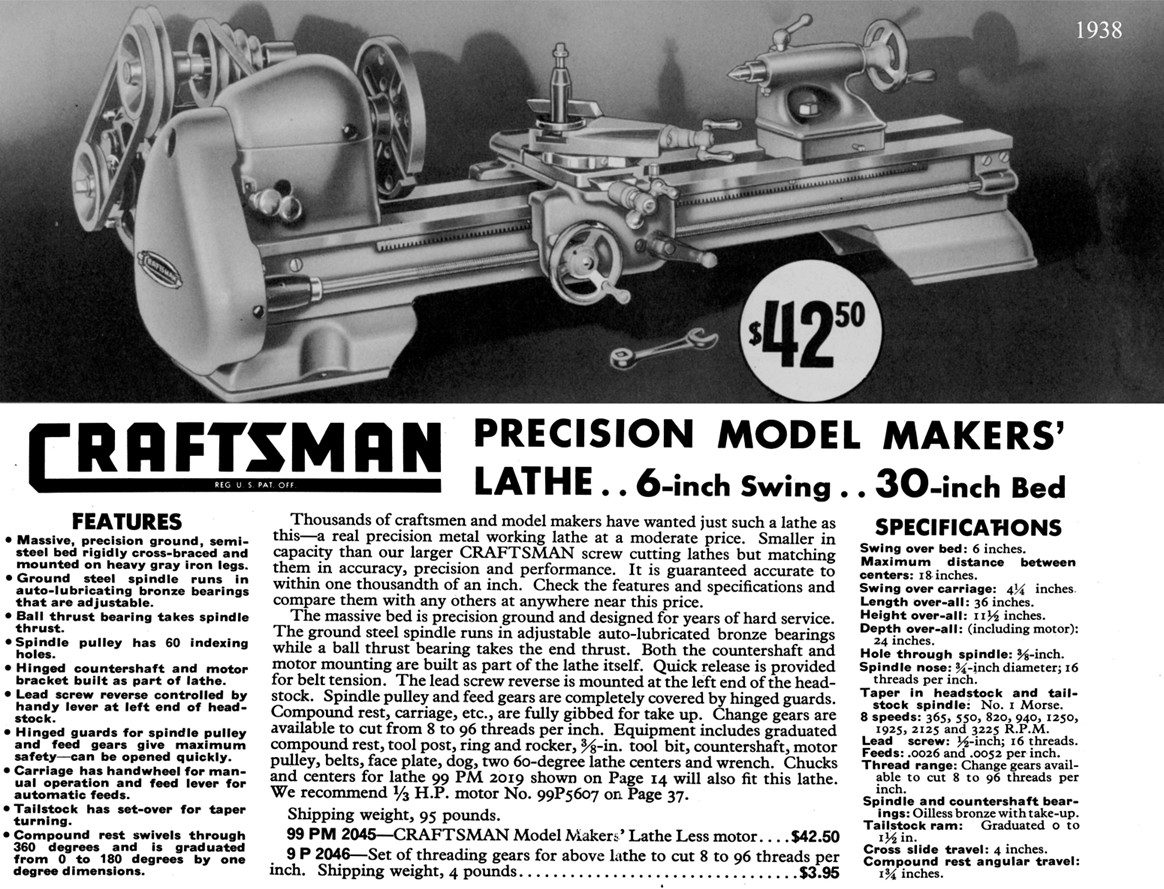

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

See: Atlas 6-inch Lathe (lathes.co.uk) : "Styled to closely resemble its larger brother, the "10-inch", the Atlas 'Model 618' 6" x 18" (3.5" centre height) backgeared and screwcutting lathe was in production from 1936 until 1974 and then, in Mk. 2 form, until 1980. Enormously popular in America - it was affordable and with a specification that allowed it to undertake the majority of jobs likely to be encountered in a home workshop - its likely that the lathe made its first appearance not as an Atlas but badged for the mail-order company Sears, Roebuck under their Craftsman identification tab as the 101.07300. This initial Craftsman model, which carried an inadequate 3/4" x 16 t.p.i. spindle thread, a headstock that lacked backgearing and a countershaft unit and belt-tensioning arrangements of a very elementary, lightweight design, was sold at the very competitive price of $42. However, it was made for one year only before being replaced by the much better specified 101.07301--as listed in the post 1938 catalogs shown here : Craftsman 6-inch Lathe Catalog Extracts (lathes.co.uk) Note advertisement text in left-hand column: "Ground steel spindle runs in auto-lubricating bronze bearings that are adjustable." That may simply be a belt issue. I've heard several reports of surprisingly smoother and quieter running of the very similar Atlas/Craftsman 12" lathes when old standard drive belts were replaced with correctly-sized new Accu-link adjustable link "V" belts or the equivalent. The Accu-link belts are a boon for lathe owners because they permit belt changes without the need to disassemble the headstock and back-gearing assemblies to get a non-opening belt around the belt wheels. There's no problem at all turning wood on a metal lathe other than the need to keep the lathe clean. Wood chips and shavings and sawdust easily finds its was into motor armatures and gearing, quickly absorbs oil, and creates a nasty gunk that isn't particularly healthy for high-tolerance machine tools. Sheilding from sawdust and careful vacuuming up after wood working is required for proper maintenance. That said, if one has any great amount of wood turning to do, it's probably easier to buy a wood lathe, which are relatively inexpensive, especially on the used market, than to keep a machinist's lathe clean if it's being regularly used to turn wood. -

Another tip for you and anybody else who hasn't discovered it as yet: There is a wealth of fine detail brushes available at a fraction of the cost charged by modeling and artists' supply stores, in fact, at almost "disposable brush" prices, to be found listed for sale to manicurists. It seems there's a lot of fine detail painting now fashionable in the manicure business. Check out the manicurists' "nail art" sites for ultra-fine brushes of all types, particularly lining brushes. See: Amazon.com : nail art brushes and Nail Art Brushes for sale | eBay For example: Nail Art Brushes Nail Liner Brush Liner for Nails Easy Hold Thin Nail Art Design | eBay, $7.91 w/ free shipping:

-

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Indeed it is! I should have looked more closely at the photos. They appear quite a bit alike. The 6" is a sweet small modeling lathe, but they don't seem as available on the used market as the 12"-ers. -

Atlas craftsman lathe

Bob Cleek replied to kgstakes's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

And still are available on eBay or from after-market manufacturers... for a price. Check out "Mr Pete 222" or "Tubal Cain" (same guy) on YouTube. He's a retired shop teacher with great instructional videos on the Atlas/Craftsman 12' lathes. Everything you even wanted to know. I believe you can look up the age of yours with the serial number on lathes.co.uk under the Craftsman entries. There were a number of refinements over the several decades that this lathe was manufactured. There are many of them floating around and so parts are readily available. They are somewhat of a cult thing now. They aren't state of the art anymore with CNC and DRO features, but they'll do anything you could possibly need to do (including milling with the milling attachment) on a medium to light duty 12" manual lathe. If you have one that hasn't been "destroyed" along the way by misuse, they are certainly worth restoring. They're worth money even if they are trashed because of the continuing market demand for parts. (Threading gear sets are still available if you are missing any. Be careful not to "crash" the gears and damage the gear teeth. The gears are made of Zamac, a relatively weak alloy and it's not difficult to break teeth if you don't know what you are doing operating the lathe. Not to scare you off, but lathes are not a machine you ever want to learn how to use by just "fiddling" with them and they can be very dangerous in the hands of an untrained operator. All the operating manuals for these lathes are available for free online. Google them up. I love mine. I picked it up along with just about every possible attachment (except a taper jig, darn it... but those are still made by an aftermarket manufacturer) from a retired old school machinist's widow for a very reasonable price. -

That's an excellent explanation of how to make a Ballentine coil. There are a number of ways to coil falls for the same purpose as a Ballentine coil. Other's make use of "figure-eight" faking, and so on. The original question, if I understand it correctly, addressed a "Flemished" line coil where the line lays in a tight flat coil on the deck without any overlapping turns.

-

Yes, you have stated it correctly. I got it bass-ackwards. Sometimes it's a lot easier to do something relying on "muscle memory," than it is to write an instruction on how to do it! The photo above is indeed correct. What I should have said was that the coil begins with the bitter end in the center and is rotated until the line is fully coiled with the working end of the line running off of the outside of the coil. Obviously. it one tried to rotate the coil on the flat of the deck with the working (belayed) end in the center, the line would twist up between the center of the coil and the belaying point and get all kinky! Thanks for spotting the error! BOB

-

Or a lot of razor blades, as the saying goes!

-

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

It's just a short drive from Mystic Seaport in the town of New Bedford a couple of blocks from the waterfront. It's not in a real "touristy" area, or wasn't when I was last there years ago. New Bedford is, or was, still a working waterfront back then. If whaling is your thing and you're in the area, take the ferry from Hyannis to Nantucket and check out the whaling museum there. It's a very good one as well. -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Hard to say the date on the New Bedford Flags poster. I tried to enlarge it, but I couldn't get a legible look at the date, if any. It's from a Pinterest post that credits it to the New Bedford Whaling Museum's collection. (Home - New Bedford Whaling Museum) You could probably call them and ask. You might get lucky and connect with somebody who could check for you. The "poster" does contain the identity of the printer, although I can't read it, and it probably has a copyright date on it somewhere. It looks to have been a printer's advertising "give-away." The New Bedford Whaling Museum isn't a large museum and so staff may be accessible by phone or email, unlike much larger institutions. It's a great museum nonetheless and definitely worth a visit. (Also the home of the largest whaling ship model in the world, Lagoda at 1:2 scale. Lagoda - Wikipedia ) -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Happy to oblige, Allan! If it weren't for opportunities to share this trivia, I'd have no excuse for storing all of it in my cranial hard drive! -

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

Bob Cleek replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Pennants used to identify individual vessels, be they naval, merchant, or pleasure craft, were commonly carried prior to the wider use of code signals (flags) to indicate the code (usually "five level" - five letters and or numbers) assigned to the vessel by navies, marine insurance companies, and national documentation agencies. Pennants were rarely opaque with lettering on both sides. Actually, in practice, it was much easier at a distance to identify a signal that wasn't opaque because the sun would shine both on it or behind and through it. If a pennant or signal were opaque, its "shaded side" would appear black at a distance. Additionally, there are advantages to a pennant or signal being made of light cloth which will readily "fly," in light air. In fact, when a square-rigged vessel is running downwind, her signals, ensigns, and pennants on the ship moving at close to the speed of the wind itself, would cause the signals, pennants, and ensigns to "hang limp" and be difficult to see at any distance. Even today, when racing sailboats routinely show "sail numbers" on their sails to identify themselves, the numbers must appear reversed on the "back side" and no attempt is made to overcome this. The international racing rules require that sail number and class logo, if appropriate, must be shown on both sides of the mainsail in that case each side of the sail will have the number shown "in the right direction." There are very specific universal regulations for the placement of sail numbers on racing yachts which specifically dictate how the obverse and reverse lettering must be applied to a vessel's sails. (See: TRRS | Identification on sails (racingrulesofsailing.org) Today, adhesive-backed numbers and letters are applied to synthetic fabric sails. In earlier times, the letters and numbers were cut out and appliqued to the sail. In earlier times, several systems, other than identification code signals, were in common use and these are what we commonly see on contemporary paintings. The two primary signals used were a large flag or pennant with the vessel's name on it, or the owner's name, or company name, on it, or a logo of some sort. The latter were usually called "house flags" which designated the identity of the owner of the vessel. When steam power came on the scene, these owner's "house flags" were supplemented by painting the funnels of the steam ships with the colors and logos of the owners' house flags as well. House flag chart from the 1930's or so: The house flags and ship name pennants we see in the contemporary paintings serve to identify the vessel in the painting, but in order to fully appreciate the purpose of "naming pennants" and house flags, it has to be understood that until radio communications came into being (first Marconi transmission at sea by RMS Lucania in 1901 and first continuous radio communication with land during an Atlantic crossing ... RMS Lucania in 1903.) there was no way for a ship owner to know much of anything about their vessel until it returned home which, in the case of whaling vessels could be two or three years. Shipping companies, marine insurers, and maritime shipping companies, among others, had a desperate need for news about their ships, but they could only know the fate of their ships, crew, and cargo (though not necessarily in that order!) when the ship showed up. Ships at sea would hail each other when they ran into one another at sea: "What ship? What port?" and sometimes get word back to owners that their ship was seen, on the Pacific whaling grounds, for instance, months or even years earlier, but there was no way to know what was going on with a ship until she returned to her home port. Businesses ashore were desperate to know the fate of ships and shipments and being the first to learn of a particular ship's arrival in port gave a businessman a particular advantage in making investments, commodities trades, purchases, and sales. This was especially true in the United States before the construction of the transcontinental telegraph system owing to the immense size of the nation "from sea to shining sea." For example, in San Francisco, which was for a time shortly after the discovery of gold, isolated from communications with the East Coast, things as simple as newspapers would arrive only by ship and when they did, the race was on to get in line to read the "news of the world." An organization called the "Merchants' Exchange" was created to operate a semaphore telegraph system from Point Lobos at the farthest west point of the San Francisco Península to what came to be called "Telegraph Hill" to communicate the identity of ships arriving off the Golden Gate often many hours before they actually docked and to make East Coast newspapers and other information sources available to local subscribers. On the East Coast, seaport homes had their famous "widows' walks" where the ship captain's wives would look for their husband's ship in the offing to know whether he'd ever return, and they'd know by the house flag which ship was which. Yes. That's a good description of the device used to set pennants and house flags "flying." The device is called a "pig stick" as it is a short stick similar to what a pig farmer would use to herd his pigs. A pig stick has a wire or wooden "auxiliary stick" from which the flag or pennant is flown independent of the main stick. This device, pictured below, prevents the signal or pennant from wrapping around the "pig stick" and fouling on the pole or otherwise becoming unreadable. The middle two paintings of ships posted above show those two ships simultaneously flying a "name pennant" from the maintop, a "house flag" from the foremast top, and a "five level code" (likely assigned by Lloyds Insurers.) identifying the vessel in a commonly redundant fashion at that time. -

alcoholic stain on blocks

Bob Cleek replied to Frank Burroughs's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Well, that would depend upon whether you wanted to color them differently from the natural color of whatever you made them from, no? The color of blocks will depend largely upon the period of the ship one is modeling. Some blocks were oiled bare wood. Later, blocks were painted, usually white or black. -

Interesting. I've never heard the term "cheesing" used before. I presume this is a reference to a "wheel" of cheese. It's also called "Flemishing" or a "Flemish coil." I suppose this was a reference to where it was commonly done. Banyan gave a number of good reasons against flemishing line on deck. There's more. Long exposure to weather and UV will cause uneven deterioration on the surface of the line is another one. A properly Flemished coil will run fair, however. This requires that the working end of the line is pulled from the center of the coil. The "bitter end" should always end on the outside of the "coil" (pad) and not in the center. The way a Flemish coil is created in real life is that the coil begins in the center and the entire (growing) coil is turned round and round on the deck while lying flat until the bitter end is reached. As Banyan said, it was only done for display purposes at formal inspections, but was never done in ordinary use.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.thumb.jpg.5a33ce11c7bd2c0f448734dd2e7ea95b.jpg)