-

Posts

1,770 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Mark P

-

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi FS; Thanks for your thoughts. Fatfingers found the solution to this for me, which is to go to modify, object, image, frame and make the frame's value 0, which I believe is the equivalent of making them transparent, as you suggest. All frames then disappear. Great! All the best, Mark P -

Hi Tim; Ditto with Allan's comment on your drawing. One thing that springs to my mind immediately when I look at your stern is the window styles. Very often, the outermost windows were either slightly, or very, different to the central ones, due to their being in the quarter galleries, and not being part of the great cabin, nor fixed between the stern timbers. All the best, Mark P

-

Inexpensive powered rope walker

Mark P replied to hornet's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Greetings Hornet; That is a very clever little set-up! Congratulations on your ingenuity, and thanks for sharing this with us. I think I'll have a go at making something similar. All the best, Mark P -

Red Paint or Red Ochre

Mark P replied to davyboy's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Hi everyone; Carrying on from Druxey's comments in his last post here, I have studied Deptford Dockyards letter books for the middle of the 18th century, and there is correspondence about paint, and records of deliveries of oil and pigments. The ingredients were certainly mixed on site, prior to use. All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Greetings everyone; Following on from all the help which I received from fatfingers (for which thank you again) I have found out one thing which may interest fellow-modellers/draughtsmen, and have a further request for any advice or help. I am now able to insert a raster image in a drawing, on top of my background layer. This still has the white rectangle, but, if the image has been made transparent by the process outlined above by fatfingers, it is then possible, using AutoCAD's own properties menu, to turn on and off the background transparency of the inserted image. The white background disappears, leaving the image clear. However, I am still left with the rectangular outline around the inserted object, and I wonder if any other members have an idea of how to remove this unwelcome survivor. All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Fatfingers; Your help has been invaluable. Thank you again. I too look forward to reading the results. But it will be a while yet! All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Fatfingers; Thank you for your patience and the further guidance on how to do this. I am very happy to learn from you. I will purchase a copy of Inkscape, and set to work. I thought I recognised the background in your post! If you are building a model of Royal Caroline, then for God's sake talk to me before you go any further, especially if you are using Sergio Bellabarba's book as a guide (it was his book that piqued my interest in her, but as soon as I did even a modicum of research, I realised that his book is riddled with errors. It is easier to list what he has got right than it is to list what he has got wrong!) Full credit to him though for a beautifully illustrated book. And research is undoubtedly much easier now than it was. But some of the errors are so obvious and so easily avoided that it is not easy to remain polite. All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Fatfingers; Many thanks for all your help. I am very grateful for the trouble you have gone to to answer my query. The explanation of bitmap vs drawing file is very helpful. I have not used bitmap much, and I will certainly not for this project. My scanner only gives the option of bitmap, JPEG, PDF or TIFF files. Will a TIFF be okay to load into Inkscape, and convert to an SVG file. If not, then I will have to get a new scanner, one which offers PNG as an output option. Is conversion to SVG sufficient to create the transparent appearance, or do I still need to set white to transparent. Once again, many thanks for your help. All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Fatfingers; Wow! I have just seen your alteration to my picture. I hadn't seen it when I posted the above reply. That's just what I want to do. How did you do that? It's like magic! Many thanks, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Fatfingers; Many thanks for the post. I can vary the image format from the scanner, if I know what type to save it as in advance. Can you explain the difference between a drawing and a bitmap. Scaleability is important, so it sounds as though I need to look at Inkscape. Thanks again. All the best, Mark P -

Inserting scanned object

Mark P replied to Mark P's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Hi Allan; Thank you for your reply. The attachment is based on a detail from the draught (none of the other carvings are shown on it) I have drawn it on a sheet of A4 paper, and when I scan it, the scan is rectangular in shape. Even if I drew it on clear film, the result would be the same, as a scan will still be rectangular, and will pick up the white background of the scanner lid. I attach an example of this imported into the CAD drawing. Thank you for looking at this. All the best, Mark P -

Greetings everyone; I am preparing a set of draughts of the Royal Caroline of 1749, and I want to include all the carved work. I intend to draw all the carved work by hand, using ink and pencil, and then scan the drawing, remove the background rectangle, and import just the carving into CAD. However, I cannot find any way of permanently removing the unwanted background, and creating a file with just the outline of the carving and all its detailing. Everything I have tried, and I have spent quite a few hours with several programs attempting this, leaves a white rectangle which blanks out all existing objects around it. Is anyone aware of a method of removing the background rectangle, leaving just the lines and shading I have drawn. Any help would be much appreciated. I am using AutoCAD LT2016, and have tried Photoshop elements and Power Point to remove the background. Example file below. All the best, Mark P

-

Hi Frankie; Thanks for posting this. I too have the others, and they are excellent. The frigate and ship of the line books were published by Seaforth, a wide ranging military/naval specialist. This book is available for pre-order on Amazon uk, but I notice it is published by the US Naval Institute Press. Presumably the author got a better offer! All the best, Mark P

-

Greetings Dafi; The top ropes were used to raise and lower the topmasts. Prior to 1800 (according to Lees) the top ropes were not unrove once the topmast was in position, but were a permanent feature of the rigging. This was probably because in stormy weather it was a not uncommon procedure to lower the topmasts to reduce top-hamper, as shown in several paintings I have seen. I would imagine that your thought that this is to allow for a lead to the capstan to be quite correct. I have only seen the scuttles before on third rates. So as Druxey says above, they probably only appeared aft of other masts on first rates, although perhaps on second rates also. Thanks for passing on your observations. All the best, Mark P PS: I always think it is such a shame that the beautiful carved work to the stern and the bows was ripped off just before Trafalgar. If only they had done it afterwards. She was a much more attractive ship prior to the alterations.

-

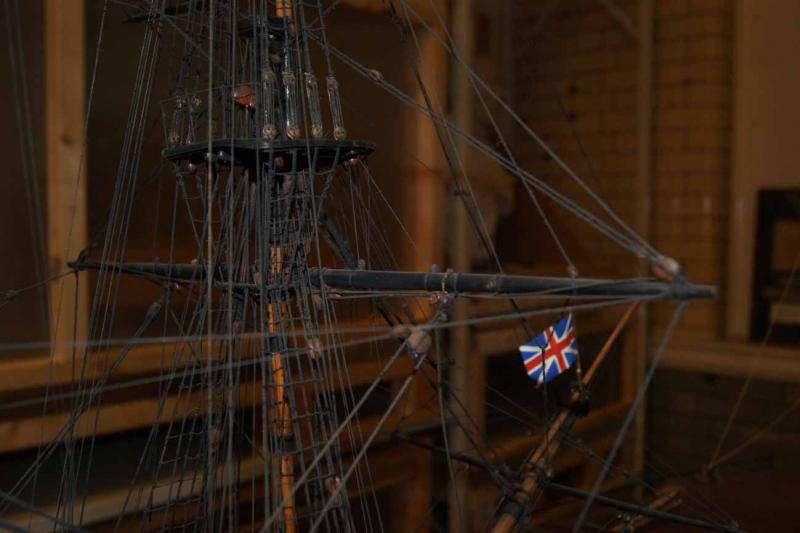

Hi Macgoodwin; If the sails were removed for a shortish period of time, normal practice was to join together the lines which would have been attached to the clew of the sail, and pull them up to the yard. Buntlines would be made fast to the strop of their block on the yard (or perhaps to the jack-line, if these were fitted to the Cutty Sark) The idea was to save time when bending the sails to the yard. Re-reeving ropes took much longer than simply re-attaching them. The attached picture (contemporary rigged model, in the Science Museum Archive since 1881) shows this in a much earlier, Naval, not merchant vessel; but if the Navy, with high manning levels, did this, then it would seem very reasonable to expect the merchant ships, with a smaller crew and time/profit considerations driving them, to be even more likely to take the route that saved time/money. The picture shows the sheet, tack and clew blocks all pulled up to the yard. Buntlines are visible coming from the lead blocks under the top. All the best, Mark P

-

THE 74-GUN SHIP by Jeronimo

Mark P replied to Jeronimo's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

I have to agree. A real quality piece of craftsmanship!- 194 replies

-

THE 74-GUN SHIP by Jeronimo

Mark P replied to Jeronimo's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

Hi Karl; Congratulations on a beautifully constructed model. Does the construction method of the frames mirror full-size contemporary French practice? If so, it is interesting to note the differences from English techniques at the time. All the best, Mark P- 194 replies

-

What are these? does anybody knows? thanks.....

Mark P replied to BIGMAC's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Greetings Gerard; Many thanks for the explanation. That's completely logical once it is made clear, as with so many things. All the best, Mark P -

What are these? does anybody knows? thanks.....

Mark P replied to BIGMAC's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Greetings everyone; With regard to this object being a counterweight, I do not think this is very likely, as it is on the longer part of the yard. A counterweight would need to be on the shorter part to balance the additional length of the longer arm. At least, if it was countering the weight of the yard this would be so. If it was somehow intended to counter a force exerted by the wind this could be different, but a rope would seem the easiest way of countering the wind. Would a weight at this point be advantageous or disadvantageous when changing tack? How is a lateen sail handled when manoeuvring? Could it be intended to act as a damper, taking some of the spring out of the yard that could arise due to its length, especially during a change of tack? There is no sign of any rope reeving through it on any of the illustrations shown (although that could, of course, be artistic licence) so a truck for flag halliards seems unlikely. Especially as one vessel is shown with a flag at the masthead. Although, certainly, the absence of flags from the yard-arm does not prove anything in this case. More food for thought, I hope. All the best, Mark P -

Wales

Mark P replied to -Dallen's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Greetings dallen; gentlemen; I am glad to know that several people found my post useful. Mike: the reason for the gradual reduction in the sheer of a ship seems to be that the higher the bow and stern are built, the more they catch the wind, with the result that the ship will heel over more easily, and make more leeway. In earlier centuries, it was considered an advantage to have one's decks higher than those of an enemy, for the purpose of shooting down at them with bows or spears etc, whilst it was much harder for the enemy to respond. Shipwrights therefore curved the hull upwards as much as they could. As cannon became more important in warfare, this height became less important, and performance considerations drove a gradual flattening. Improved construction techniques developed under Robert Seppings, chief surveyor to the Navy, led to the ability to build longer ships that were less likely to hog due to the greater strength of their hull structure, thus removing the last reason to build with an upward curve. Ships could then be made with little or no sheer. All the best, Mark P -

Wales

Mark P replied to -Dallen's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Hi dallen; To answer your question in general terms, relating to British/American warships: The wales were lengths of planking which were considerably thicker than the general exterior planking of a ship, and so projected beyond the face of the other planks, which makes them obvious features on both drafts and models. The main wale normally followed the line of the widest part of the ship's body, known as the line of maximum breadth. On the majority of British and American vessels, this was mostly vertical amidships, and changed profile towards the bow and stern. As Jaager remarks above, the wale was intended to counter-act 'hogging' or the tendency of the bow and stern to curve downwards over time, leading to curvature of the keel and affecting the ship's performance. This was caused by a combination of over-loading the ship at these points, normally with too many/too heavy cannon, and by the fact that when at sea, the movement of the waves often means that the ends of the vessel are not as deep in the water as the midships, leaving the ends less well supported. As a way of increasing the effectiveness of the wales in resisting this hogging tendency, the wales were curved upwards at each end more sharply than the decks curved upwards. Ships normally had one wale per deck, with the main wale the lowest, and those above diminishing in size. The method of constructing the wales varied considerably over time, and is one of the diagnostic features used to help date models in Museums and other collections. The upward curvature of the ship at each end is known as the 'sheer', and was much greater in earlier centuries than in more modern times, decreasing gradually, until by the first quarter of the Victorian era, most vessels were almost straight from end to end. All the best, Mark P -

Red Paint or Red Ochre

Mark P replied to davyboy's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Greetings gentlemen; I have a feeling that the red paint used was actually red lead, which has some anti-bacterial, or anti-fungal properties, and is still often used as a primer for wooden boats. This paint is, I believe, more hard-wearing than one based on red-ochre. However, this is based on a feeling that I read this somewhere. I will check up on this and see if I can find something more concrete than a feeling. All the best, Mark P -

Hi Jray; The classic modern reference is James Lees' 'Masting & rigging of English ships of War 1625 - 1860' published by Conway Maritime, and available on Amazon and others. Karl-Heinz Marquardt wrote '18th Century rigs & rigging', which covers all major nations, and the merchant fleets also. Both of these are informative, although Lees' work is probably better illustrated, and is specific to English warships. There are several contemporary works from around the late 18th/early 19th centuries, available as facsimiles, or on the internet as pdfs. A search under 'Steel's mast-making and rigging' should bring up the best-known of these. There are a few typos in the Steel's tables, though, from what I have seen discussed on MSW. Depending upon what type of vessel you are considering, there are some very good books out there which illustrate the building of beautiful models step-by-step. Most of these include a volume on masting & rigging. David Antscherl, Allan Yedlinsky & Ed Tosti have produced some very good books in this field. Check out Seawatch books, or again, Amazon. Some of the establishment lists from the 18th century also include complete listings of mast and spar dimensions. All the best, Mark P

-

Frame construction

Mark P replied to jbeyl's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Hi Jon; The TFFM books are a very good source of detailed descriptions of building techniques, and give information which is clearly explained and illustrated. This is valuable, because contemporary sources contain few illustrations, and are generally written in a hard-to-understand-now fashion. I would certainly recommend obtaining what you can of these, depending upon the type of vessel you are interested in. Another source of information, again depending upon the type of vessel, is the number of original contracts which survive for vessels built for the Royal Navy by merchant shipbuilders. These exist from the later 17th century onwards, and can be obtained from the NMM. Detailed information concerning the size of scarph joints, and all scantlings, is normally contained within these. The down-side of these is the sometimes difficult to interpret phrasing, and the lack of illustrations. All the best, Mark P

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.