-

Posts

5,553 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by wefalck

-

Everything you ever wanted to know about this (and other) lathe(s): http://www.lathes.co.uk/atlas/index.html But beware, it may make you drool, when you see what kind of attachments etc. once were available.

-

Somehow, I overlooked that these are pencils. Then there are not acrylics (probably). They are what is called 'artistis water colour pens'. They have been around for decades. Unlike normal coloured pencils that are bonded with a greasy substance (not sure what they used), the pigments in them are bonded with a water-soluble binder (chatCPT could probably tell you what it is). The problem from my point of view is that after application the pigment remains water-soluble. One has has to keep this in mind for the following steps in painting. Applying light coats of varnish could solve the problem. I suppose the Tamiya 'clear' lacquers are water-based acrylics? That would explain the smudging effect on your 'wood' layers, because you partly redissolved the pen-pigment, particularly when applied by brush.

-

Steamboats and other rivercraft - general discussion

wefalck replied to Cathead's topic in Nautical/Naval History

The Dutch company Artitec makes some resin-kits of small German railway ferries around the island of Rügen (I think) in HO- and N-scale: https://www.artitecshop.com/en/railroad-ferry.html https://www.artitecshop.com/en/wittow-ferry.html https://www.artitecshop.com/en/ferry-fehmarn.html - This one I remember seeing in operation, when we spent our summer holidays with may grandparents up at the Baltic coast.- 277 replies

-

- Steamboats

- riverboats

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Steamboats and other rivercraft - general discussion

wefalck replied to Cathead's topic in Nautical/Naval History

I seem to have read of similar examples from Russia, where tracks were laid across frozen lakes to provide short-cuts, rather than going around the lakes.- 277 replies

-

- Steamboats

- riverboats

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Steamboats and other rivercraft - general discussion

wefalck replied to Cathead's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Interesting subject! These 'Trajekts', as we call them in Geman and neighbouring languages, once have been quite common at places, where it would have been too difficult, not cost-efficient, or impossible to build bridges. Some of them are still in operation, although bridge-building has become more daring in recent years and they were laid off. In some cases there was joint use by railway carriages and vehicles. - On Lake Constance, between Switzerland and Germany was one in operation for many years. - At lower reaches of the River Rhine one took whole trains, including the engine - At the German Baltic coast several connected islands with the mainland to allow through trains. - There used to be a two-stage one that connected the German mainland with the island fo Fehmarn and then on to the Danish island of Lolland. In the 1960s the small rail ferry to Fehmarn was replaced by a bridge. I once took, just for the fun of it, the through-train from Hamburg to Copenhagen along this route. - The once famous Trelleborg to Sassnitz train-ferry that connected Stockholm with the rest of Europe via Germany was discontinued after 111 years of service in 2020.- 277 replies

-

- Steamboats

- riverboats

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Indeed, making the split at the long part and soldering there, as druxey said, would have been my first thought too. Also silver-soldering with some paste might have been easier and stronger.

- 2,444 replies

-

- heller

- soleil royal

-

(and 9 more)

Tagged with:

-

I inherited a whole bunch of pre-war(?) unisolated ones from my father. In general, they are much better stamped/folded and close better, than what you get today.

-

Indeed the SAVOIE (1914): https://www.cgn.ch/en/savoie.html. We had an extended Sunday-lunch cruise. Warming up the engine: Getting ready to put to 'sea':

-

Thank you very much, gentlemen, for your kind comments! Last weekend I did some field studies on Lake Geneva on flags moving in the wind: ...

-

It seems that one can spend a fortune on those fly-tying vises ... I would rather spend those 200-400 US$/€/£ on a machine tool. You have think a bit over what operations you want to use it for and then design your own from materials at hand and according to your machining capabilities. I gather with a piece of curtain-rail and some pieces of wood and steel-rod you could make a very useful tool for tying blocks and the likes. At least over here in Europe, alligator clips are designed to fit over 4 mm banana-plugs, so starting with 4 mm rods is a good idea. You have to have two blocks or two angles that can be screwed to the curtain-rail, so that you can adjust the distance according to the need. The exact design you have to figure out yourself to suit the material you have (or are prepared to buy). I made various clamps and hooks with 4 mm stems so they all fit into the same holders and can be combined to suit the need. If you are as unlucky (and ignorant) as I was in my younger years and bought one of those multi-articulated and poorly manufactured 3rd-hand-thingies, you may want to dump most of the pieces and just keep the foot and may be some rods to build something useful around it. Fewer degrees of freedom are more useful for preparing the rigging.

-

Flag with ship name reversed on one side?

wefalck replied to daschc01's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Pennants or streamers with the ship's name on it are commonly seen on paintings of merchant craft (sail and steam!) throughout the 19th century. I don't know, whether these were sewn on or painted, but tend to think they were sewn for longer life. Given that the material of pennant would be very light, in translucent light they would become viurtually unreadable, if they were executed with the lettering in the correct way on both side. Usually, the name begins on the side towards the mast. I seem to recall having seen paintings, where the lettering on the pennant was in mirror image. Usually these name pennants were flown from the truck of the main mast or the foremast of schooners and brigs. I suspect on long sea-passages they were taken down. As most ship's portraits show the ship near the coast, they are usually represented. In the second half of the 19th. century or so, name pennants were gradually replaced by number flags for identification (which required that you had to have an up-to-date 'flag-book' to hand). On paintings they are often seen together though. -

I think the stand quite matches the somewhat improvised look of these boats.

- 163 replies

-

These machines are just not worth the (financial) effort for something that can be done with simple hand-tools. Keep in mind that the copper-sheet should be very thin, 0.1 mm max (which is the thinnest one can normally get), and this would be very soft, so no machinery needed to shape them. Another aspect would be, that one would literally iron out any embossing to simulate the nail pattern, if one goes for that. Or vice versa, putting the embossing in after rolling the plates would straighten them again.

-

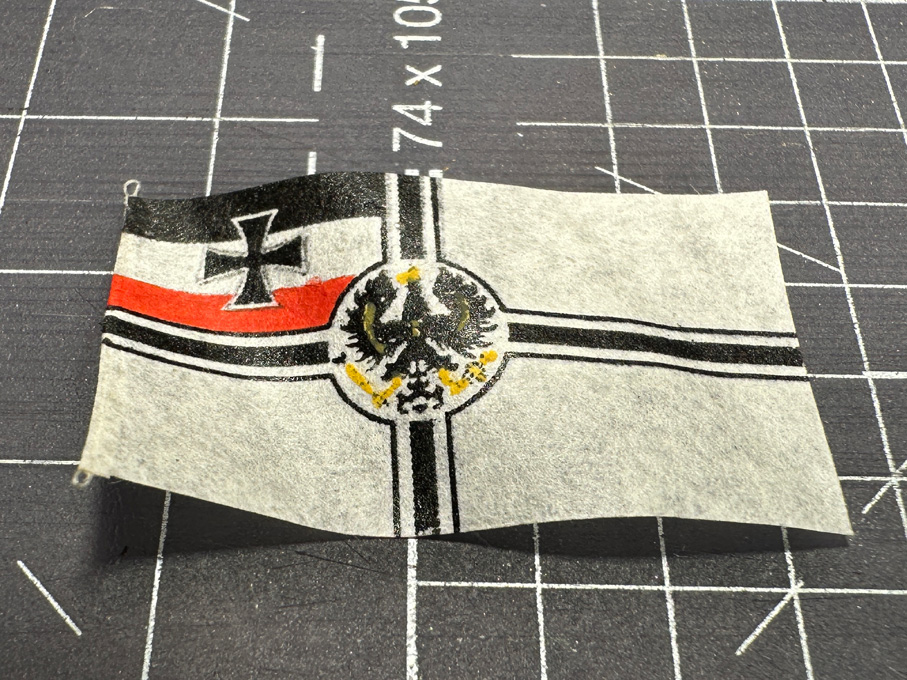

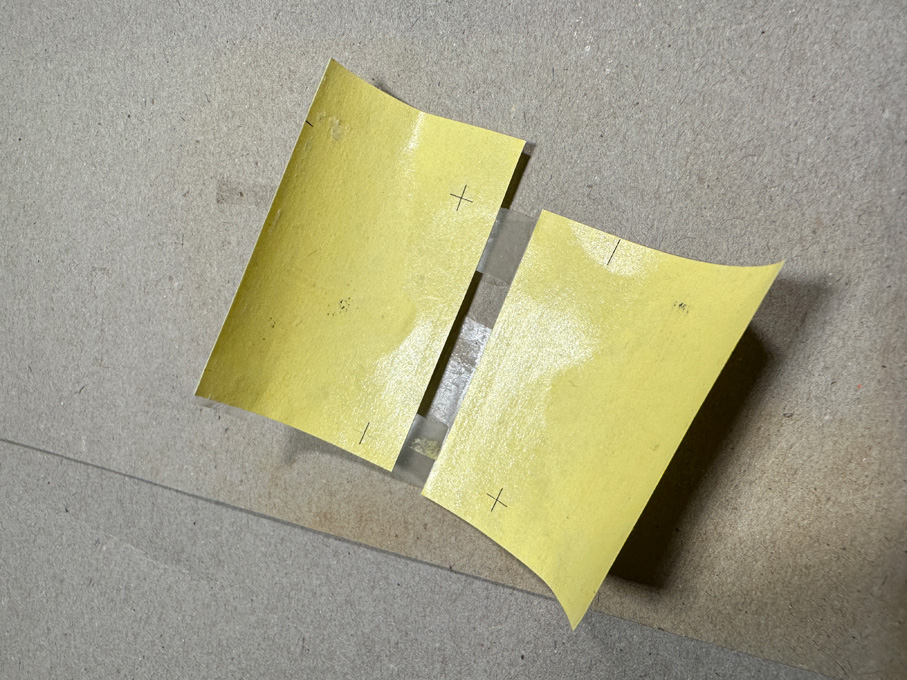

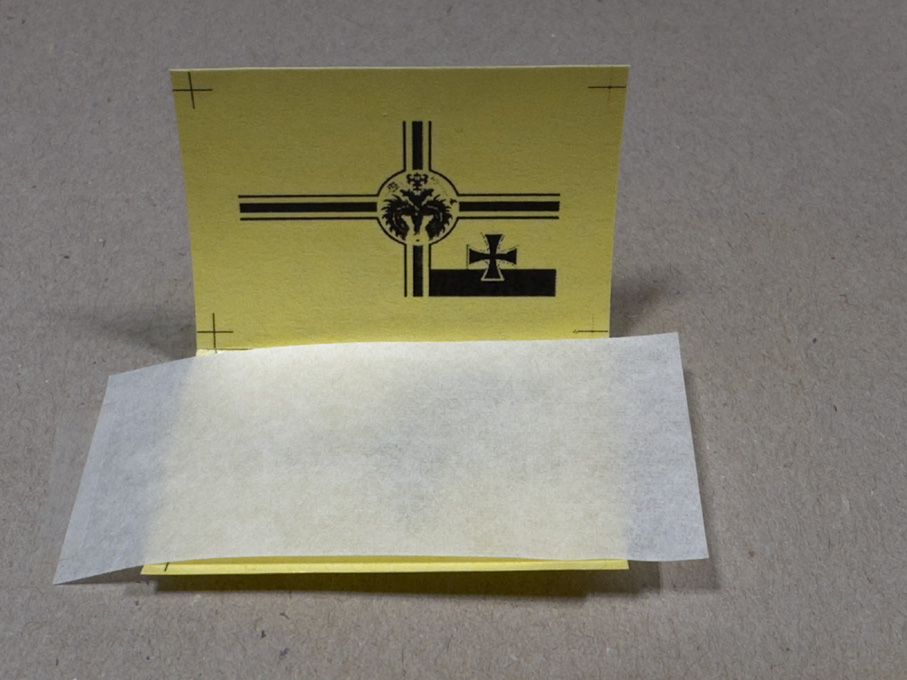

Once again, Thank You for your kind comments ! Again, real life including (business) travels got in the way of progress on this project. In addition, while I was having dinner in a restaurant together with colleagues, suddenly some ‘floaters’ appeared in one eye. I went immediately to the eye-doctor, who checked my eyes thoroughly. Luckily the floaters are harmless, but annoying signs of age. No retina-detachment or something else serious. Apparently, they can spontaneously disappear or the brain sort of ignores them after a while – keep fingers crossed. For the moment they are quite bothering, when working on really small things … so on to the ensign. ************************************ The Imperial German Navy Ensign This ensign was first conceived for the navy of the North-German Alliance (Norddeutscher Bund) in 1867, bringing together the colours of the dominant powers, namely Prussia (black-white) and the Hanseatic City States, Hamburg, Bremen und Lübeck (red-white). The design obviously was inspired by the British White Ensign and makes reference to various medieval symbols, such as the cross of the Teutonic Order, and the more recent Iron Cross from the Napoleonic War. After the proclamation of the 2nd Empire on 18 January 1871, this ensign became also the ensign of the Imperial German Navy and remained it until the end of the Empire in 1919. There have been, however, some smaller modifications over the years, thus the eagle was somewhat modified and in 1902 the arms of the cross were made heavier in order to avoid confusion at distance with the White Ensign of the Royal Navy. Overall, it is rather complex design to reproduce purely manually. First, I had to find a correct image for the ensign, as it looked in about 1878 and was lucky, as the Internet furnished a digital image of sufficient size and resolution. The idea was to print it on both sides of very thin paper (the kind that was used in the old days for carbon copies on type-writer, of which I kept a small supply). Such paper, however, does not feed well through the laser-printer and aligning for double-sided printing is practically impossible. Therefore, I resorted to so-called transfer-sheets. These are a kind of waxed paper that is used to transfer laser-printouts to T-shirts, mugs and such things. Laser-printer toner is basically carbon-black mixed with some plastics powder. It can be remelted with a heat-source, such as an ironing-iron and thus transferred to another substrate. I also experimented with overhead-sheets, but the results were not as good. Printing layout for the ensign (as it would appear on the transfer sheet) In a first step, the red stripe in the flag was eliminated from the image in Photoshop, as it would print grey otherwise. The ensign was then scaled to the right size on the basis of some trial-and-error, as the laser-printer prints a few percent undersize. I then added reference marks some distance from the image and duplicated this for mirroring. Several of these left-right-pairs were arranged on an A4-sheet and then printed onto the transfer-sheet using the highest quality print setting. Preparing the pouch for double-sided toner-transfer to the ensign-blank Using the best matching pair, I made a small pouch (as you would do for the masks, when producing photo-etched parts), aligning the images against each other for a perfect match on an illuminated board (they can be bought for a few €/£/US$ on ebay et al. and are powered through a USB-charger). An oversized strip of the thin paper was slipped in between and everything taped down onto a piece of thick cardboard. I pressed down an ironing-iron set to the lowest temperature onto the package, which made the toner firmly stick to the paper and no residues left on the transfer-paper. And voilà, a double-sided printed flag with a very detailed eagle etc. The toner is (almost) completely transferred to the ensign-blank In the next step the missing red stripe was added using red acrylic paint. I also added colour to the legs and beak of the Imperial Eagle, to the Imperial Insignia and the crown using yellow-ochre acrylic paint. If one has a colour laser-printer this step would not be necessary. The flag was cut out exactly to size, except for the rear, where it was left a tad longer to provide for a hollow ‘seam’ into which a thread with two loops at the end was laid The seam was glued down with some diluted white glue. This area also needed a bit of touch-up afterwards with black acrylic paint. The ensign before adding the colours Draping the flag is best done or least pre-arranged on the flag-staff. The paper was slightly wetted and the flag laid into diagonal folds in alternate directions. Toothpicks ensured that they became folds and not creases, which would be unnatural. Such a large ensign (2.9 m x 4.96 m) would fully unfold only in a moderate breeze and not in the light wind assumed in the scenic setting. So it flaps lazily in the wind, which I tried to reproduce. The completed ensign To the thus prepared ensign the halliard was attached as a loop. This loop was taken over the top of the flag-staff and a tiny laser-cut paper disc glued on as truck. There was no way to cross-drill the staff for the halliard. The halliard was belayed on the clamp. With this the assembly is ready for installation on the boat. But I will not hoist the ensign before the crew is on board. The recruitment process is still on-going … Ensign wetted and shaped Sorry, this was a rather lengthy essay on just and ensign, but the idea was to describe in detail, how to arrive on a reasonably realistic looking flag at such as small scale. The ensign attached to the flagstaff To be continued ....

-

I have seen historic and contemporary films on YouTube that show the use of English Wheels and there may be one or two that show the construction of shop-made ones. To be honest I don't really see a need for such a gadget in ship-model building. In the automotive sector they are used to reproduce complex and tightly curved panels with beads or similar features. If you use single copper-plates or even whole strakes in most cases no particular shaping apart from pushing it snug against the wooden hull would be needed. In the worst case you could gently rub on it with a round wooden dowel or something like this on a soft and thick cardboard. In boat-building the vertical iron panels for so-called Francis-patent boats were hammered to shape over wooden formers. The same later in the early years of the car industry, before mass-production.

-

Thanks, Kurt, these are interesting insights into the operation of such tow-boats. Of course, if these flanking rudders can move, they make perfect sense, when going backward. This would be a classical application for Schottel-props, but I gather they may be too delicate for the shallow rivers full of debris. There is also a limit to the amount of HP they can bring into the water. Turnable pods with Kort-nozzles would obviate the need for all those rudders, but again debris might be a problem and the shallow draught needed. In the early 20th century for working on shallow (central and eastern) European rivers systems, where the props worked in half-tunnels were developed. Some tow-boats also used early forms of water-jet propulsion to aid maneuvering and turning in tight bends.

-

Greg, what do you mean by 'dernier line'? Dernier normally is a measure for the fineness of a thread (1 den = 1 g per 9000 metre) and was also used to classify ladies' stockings and pantyhoses. There are other systems, such as the tex. I am not a great fan of monofilament, as it tends to be relatively springy and, thus, knots tend to unravel, unless immediately secured with some varnish. Some time ago, I became aware of this high-end Japanese fishing line. It's braided, available in 'steel-gray' and down to diameters of 0.06 mm: https://fish.shimano.com/en-GB/product/line/braided/a155f00000c5ijoqa3.html. Quite pricey. I have not tried it myself, because I didn't have a need for 'wire-rope', which it might simulate quite well.

-

BTW, talking about toolmaker's buttons: I learned about them about 25 years ago, when I purchased from Lindsay Publications (now sadly defunct) a bunch of reprints of early 20th century machinist textbooks and the likes. Among these was JONES, F.D. (1915): Modern Toolmaking Methods.- 309 p., (Industrial Press, reprint 1998 by Lindsay Publications Inc., Bradley IL). Just checked on archive.org and one can now download a copy from there: https://archive.org/details/moderntoolmakingmethodsbyfranklind.jones.

-

I have a separate hard-drive for backing up everything (as I also use the computer for work) around once a month and I only remove images from the telephone, once I have copies on two independent devices ... I was wondering about these rudders in front of the Kort-nozzles: do they move? If not, the boat would be quite sluggish to turn, I could imagine. And: oh, yes, the project is coming on nicely !

-

OUTSTANDING Mini Drill

wefalck replied to Bill Jackson's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

That's a bit of thread drift now, but for really delicate work I use a watchmakers archimedean drill that requires both hands, as it does not have a return spring. I can precisely control the pressure needed/permissible (with tiny drills). Of course, the workpiece has to be fixed (some 'cello-type' suffices often), but this is good practice anyway. Mine can clamp drills down to 0.1 mm diameter.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.