-

Posts

2,471 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

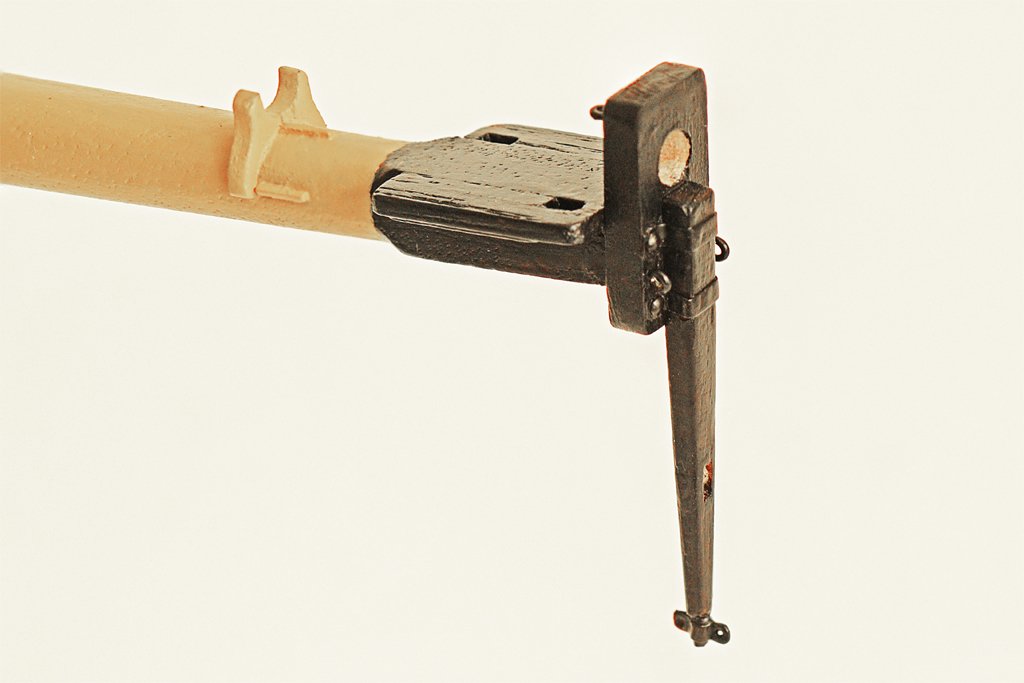

Carriage Gun Rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Thanks to everyone for contributing to this discussion! There is a lot of good information here! -

Valeriy, Thanks. I did notice that you plated some parts with copper before nickle plating, and wondered if that was to get a more uniform nickle plating. But the real solution is to just be careful with the soldering. Using a minimum amount of solder helps, and a good liquid flux (I like citrus based fluxes) helps promote solder flow between pieces. I also have a resistance soldering machine and have experimented some with it. It has the advantage that heat is generated at the contact/solder point, reducing heating of adjacent parts and previous solder joints.

-

Valeriy, Thanks. I have used some rouges for polishing but I was interested in how you do it. Your results are beautiful! I have also puzzled over what to do when a bit of solder flows over visible areas on brass parts. The tin in the solder dissolves into the brass leaving a tin colored stain. Careful positioning of the solder areas to inside or non-visible places helps, but sometimes a visible solder fillet is necessary. Blackening and other coloring agents don't work evenly over these exposed high tin areas. But it seems you solve this problem by nickle plating the parts. The plating covers the brass and solder areas evenly. Looks like I will have to set up plating equipment. I already have power supplies and I was an undergraduate chemistry major so that part will be simple.

-

I will be happy to share any information I have on the blueprints, weapons, radars, directors and such. However the CAD model is in DesignCAD file format and the files are not compatible with other software, and I don't intend to spend more years trying to translate them. I do have a few STL files that I can share. These are from my 3D printing experiments. You can contact me by personal message on this Forum or through my contact page on my Okieboat web site: https://www.okieboat.com/Contact page.html

- 54 replies

-

- 3d cad

- cleveland class

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Ras, Thank you. That project turned out to be a very deep rabbit hole and it took me about 14 years to find my way out again! In addition to the blueprints from the Archives I had hundreds of photos I took on the ship and hundreds more that other OK City sailors sent me (plus tech manuals for the equipment, etc., etc.). I originally posted the CAD model build on the DesignCAD Forum (for the CAD program I use) over the 14 year period. That is where I first met Valeriy - a friend of his in Ukraine was building a model of the ship using the pictures I posted on the DesignCAD forum and he contacted me. I still want to build a 1:96 scale model of the USS Oklahoma City CLG-5, but right now I don't have the space or tools to do so. I started on one in 2005 but stopped when I realized I didn't have enough information to do a good job. So I dove down the rabbit hole. You can see some photos of that early attempt here: https://www.okieboat.com/Ship model page.html I had planned to use styrene and Plexiglas for the main structural parts and brass for the details. Recently I have obtained a 3D printer and have been experimenting with that, but it just isn't good enough (too fragile and too much pixelation/jaggies) for what I want to do at 1:96 scale. And I have seen Valeriy's work (and Kieth Aug and others on the Ship Model Forum) and that has raised the bar for what I would like to achieve. Now I am planning a workshop addition to my garage so I will have a place to work, and accumulate the tools needed to do good work. But don't hold your breath. It may be years before I resume work on the real model.

- 54 replies

-

- 3d cad

- cleveland class

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Valeriy, I just spent the day re-reading your log from start to here to refresh my memory of your building techniques. I wanted to see how you get such beautiful finishes on your metal parts. You said you used Zapon varnish on the brass parts, and you nickle plate a lot of the metal. How do you polish the metal before paining or plating it? Does the metal plating just naturally produce a smooth shiny surface?

-

There was also a Black Pearl yacht in Newport, Rhode Island back in the 1960s.

-

Work bench width and height - any recommendations?

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

More good ideas! Thanks! Steve, I will have a contractor do the main work and that will have to go through the city engineering department for permits, etc. What I have drawn is just a conceptual drawing. The city's inspectors are pretty thorough. Insulation is important. We rarely get down to freezing here, and rarely over 90F in the summer, so it is pretty mild. But the uninsulated garage gets down into the high 30sF (~4C) in winter and into the 90sF (~35C) in summer. So I'll need good insulation to make the space usable year round, and for the benefit of the machine tools. I had not thought of insulation beneath the concrete floor. I have never seen that used here. It might compress and allow the concrete to break. I'll see what the contractors recommend. I think I recall reading in our building codes that at least one window is required since this will be an "occupied" space (as opposed to closets and such). Having a flow of fresh air when it is nice outside will be good. -

Lateen. You can see pictures of his build in the llink he posted. I have no idea how the lateen sail was used.

-

Work bench width and height - any recommendations?

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

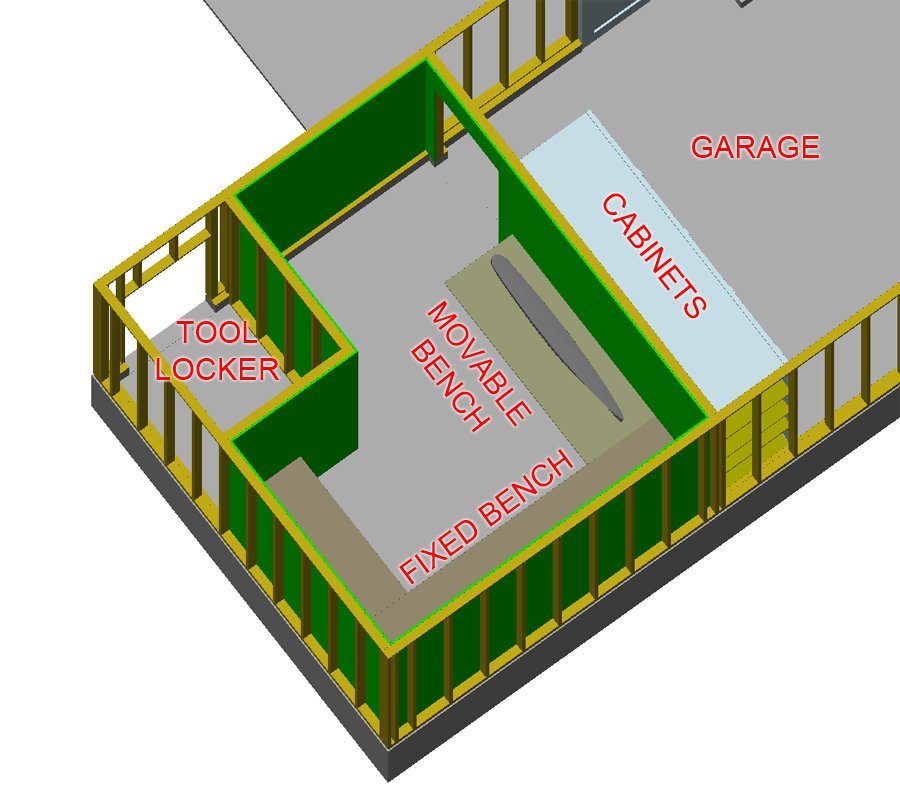

Thanks again, everyone. The floor will be reinforced concrete continuous with the floor of the garage. Who knows, someone may want to work on something heavy in there some day. I will need mats on the floor, at least in front of machines (mill, lathe) that I will be standing in front of for long periods. I'll use adjustable height stools or chairs that I can move in front of other work areas. I like the way the bench was constructed in the video vaddoc linked to. There will be a "L" shaped bench across the end of the room and along the short side where the outside tool locker will be. I think 30" (76 cm) deep will be about right. This bench will be about 12 feet (3.66 meters) on the long side and ?? feet (?? meters) on the short leg. Here is an overhead view of what I have in mind: It is a small "retirement" house, with a single car garage. The workshop is an extension of the garage. The wall with the door is 13.75 feet (4.2 meters) long and the wall along the long side of the fixed bench is 11.65 feet (3.55 meters) long, inside dimensions. You can see the 6.5 foot long (2 meter) CLG hull on the moveable bench. The benches are 30 inches (76 cm) deep. The "tool locker" is an outside accessible store room for a lawn mower and gardening tools. They currently occupy the space in the garage between the end of the cabinets and the upper wall in the picture. When I put in the doorway I will need somewhere to put all those things. I will put the vacuum and air compressor in the cabinets in the garage and plumb them into the work room. That way the noise will not be in the work room. The shop isn't very large but it is a major improvement. Right now I do most of my work on the kitchen table with hand tools. Now I just need to draw up 2D plans and get some bids from contractors. I'm sure there will be changes. I will need at least one window. I have been building and remodeling houses since I was a kid, and I suppose I could do most of this except the concrete work. But I'll have a contractor build the foundation, framing, exterior walls and roof. That's a caveat to my age (and my significant other). I can finish the interior myself. -

Work bench width and height - any recommendations?

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Jaeger and Bob, Excellent suggestions! I had been thinking about a bunch of AC outlets below the front edge of the benches, alternating with the vacuum outlets. Your point about not dragging power cords across the bench top is well taken! The idea of running some 220 VAC to outlets above the benches is also a pretty easy thing to add. There are already 220 VAC circuits in the main breaker panel in the garage. One thing to keep in mind before planning a lot of separate AC circuits - have you priced Romex lately? I recently installed a whole house fan in the attic and I needed about 150 feet of 14/2 Romex and it was going to cost a small fortune. Fortunately I discovered most of a 250 foot roll hiding in the back of the garage storage, left over from a wiring project long ago. I planned to put the vacuum inside a cabinet to reduce the noise. I still wanted to be able to pull it out and roll it around so I could use it in the garage also. However, on the other side of the common wall between the shop and garage is a large storage cabinet that I could put the vacuum in! No need for the wireless on/off. I can just put a switched AC outlet in the garage cabinet. A hole can run through the wall from the vacuum to the vacuum manifold. I do plan to have the shop floor level with the garage floor, with a 36" door between the shop and garage. I will need to roll some pretty heavy tools and boxes into the shop. I had also thought about having a roll-around work bench so I could get at all sides of a large model without having to turn it around. One of the benches will be about 90 inches (228 cm) long. I suppose I could make it movable. It is the one closest to the door and is where I was thinking of putting the model. I would attach the AC outlets to the wall above where it would normally be positioned. I plan to put pegboard above these wall outlets. These would remain on the wall when the bench is moved. The room isn't very large so I will have to plan the size of a moveable work bench so it can be turned around without having to roll it out to the garage to turn it and then back into the shop. I just tried it in the CAD model and an 84" x 30" (213 x 76 cm) table can be rotated 360 degrees in the shop if I champfer the corners about 6 inches (15 cm)! -

Work bench width and height - any recommendations?

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Thanks for all the ideas. I am planning an extension to the back of my garage for the work shop. It will have a "L" shaped shop area, with an inset storage closet with an outside door for storing a lawn mower and gardening tools. The space will be insulated and have its own heating and possibly air conditioning and dehumidifier (this is Oregon and it can rain for months on end). Right now the garage gets too cold in winter to work out there, and pretty warm in summer. It wouldn't be a good environment for machine tools. I am thinking of built in benches along three walls - a "U" shape - with plenty of room in the middle for moving around. I like Jaeger's suggestion to make the benches as deep as I can comfortably reach. As far as bench height is concerned, 36" - 39" (91 cm - 99 cm) is about elbow height and seems to be a comfortable height for standing. It is low enough to allow me to lean over a lathe or other tool for making adjustments. Steve's idea of making it the same height as the deck of the table saw is really good! I want to get a table saw on casters for large scale house work. It will be stored along the fourth wall along with a roll-around tool cabinet. I can roll it into the garage area for working on long pieces,such as making work benches. It also will be handy for cutting large stock for model work. I will have some shelves below the benches and maybe a space for a roll-around tool cabinet.These will be set back enough that I can sit at the bench on a stool. I will definitely have drawers to hold accessories for each tool. Shelves or cabinets will be mounted to the walls above some of the benches, allowing room for taller tools like a milling machine. Lights will be mounted to the bottom of the shelves/cabinets. I was thinking of having AC outlets along the back of the benches at least every two feet. Outlets and wiring are pretty inexpensive relative to the costs of the rest of the project. Each bench will have its own AC circuits and breakers - at least two per bench. I have 17 unused 15 Amp breaker positions in the house 200 Amp breaker panel in the garage close to the shop extension, so I can wire a lot of individual 15 Amp circuits and gang breakers for 30 Amp circuits. I am also considering a vacuum manifold under the front edge of the bench. A shop vacuum will be stored under one of the benches and will normally have a hose attached to the manifold. The manifold will have openings under the front edge of the bench that normally will be covered. This will allow plugging an ordinary vacuum cleaner hose into the opening and into or near any tools that make dust or chips (sander, lathe, mill). The vacuum AC circuit will have its own power switch(s) on each bench section. I can still roll the vacuum out into the workspace or garage. I have a fair amount of experience with lathes and milling machines - the large industrial machines. I will have the small "hobby" machines, but the rules for working with them will be the same. You need plenty of room for the table on a milling machine to move back and forth and for working on the ends of extra long pieces. A lathe should have lots of room behind the chuck end so you can feed long stock through the center of the chuck/collet. I am designing the shop on my CAD system, and I have a 6 1/2 foot (2 meters) long 1:96 scale model of a 610 foot cruiser hull in the plan so I can make room for a big model. This is actually one of the things that made me decide to add on the shop addition. I need lots of room to build the real USS Oklahoma City CLG-5 model. Any other models will certainly be smaller than that! **** Here is another question. What tools should be located near each other for working convenience. For example I can see where having a bench sander located close to a bench saw would save steps moving between them. A metal shear and bending tool probably should be near the milling machine. Any other suggestions? -

I am planning an addition to my garage for a workshop. I have looked at commercially available work benches and they vary from 20 inches (50 cm) wide to 36 inches (91 cm). Height ranges from 30 inches (76 cm) to 39 inches (99 cm). I am planning for a variety of small tools including a lathe, milling machine, sander, metal press, etc. I have dimensions for a variety of these tools and all will fit on a 24 inch (61 cm) wide bench. But I would appreciate advice from those of you with experience with such tools as to how wide and high the benches should be. I will likely be building all of the benches with wood myself, so I can make any size and height.

-

Here's my two cents - and that's about all it is really worth. I started modelling in the early '50s with simple balsa airplane kits (before plastic came along). They were mediocre at best. Next came the early plastic models that seemed to be wonderfully detailed at the time, but pretty crude by modern standards. They were a LOT easier to build, with MUCH better results. At one time I had a fleet of 15-20 plastic ship models - almost every penny of my allowance. Then I started building wooden models from scratch in the late '50s, with just a few sheets and sticks of aircraft balsa (all that was available from hobby shops at the time). I wanted to model vessels that weren't available in plastic. Scratch building every last piece - without any decent plans - was quite a challenge, but a lot of fun. But those early models really weren't much to look at and nowhere near accurate. My first kit was Billings Santa Maria in 1969. After scratch building it seemed like doing a paint by number painting. Not very challenging, but I learned a lot about wood ship model building, especially planking! With that kit many of the parts had to be cut from sheets of plywood that had the outlines printed on. I built a couple other kits, and added increasing amounts of hand made details. I have several more in my stash. Now you can get kits with all the parts pre-cut and shaped. They seem to me to be like 3D jigsaw puzzles. I am now kit bashing a kit of one vessel into something different, a blend of kit and scratch building. And I am 3D printing hundreds of parts parts for a large (6 1/2 foot) scratch built metal and plastic model based on a commercially available fiberglass hull. Again, it will be a ship for which no kit is available, either in wood or plastic. All of the parts (printed or not) will be from my CAD model of the ship. And I am working on plans for a wooden model of a wooden minesweeper. Again, every piece will be hand made. So I have tried a little of everything, and I think there is a place for all of these versions in our hobby.

-

An adaptation of Johnny's idea would be to saw a groove vertically above the slot for the keel on the face of the part on the inside of the curve. Don't cut all the way through the bulkhead. Just cut about half way through the part or enough to allow you to bend the part around the groove. It looks like t is three layer plywood so cut down through two layers. Then bend the part flat. Be careful - if it is an old kit the wood will be brittle and might break (but that would be easy to repair). Now lay it flat with the cut side up and weights on the outer edges to hold them down. Glue a wide wood patch over the cut from just above the keel notch to just below the deck. This should give you a bulkhead of the proper dimensions with no significant curvature.

-

A friend, William McCash, wrote the book "Bombs over Brookings" about Nobuo Fujita and the attacks on the Oregon coast. The aerial attacks weren't on towns or forts, but in the Coast Range forests. The idea was to start forest fires to destroy the timber resource. It failed. No significant fire resulted. The Coast Range is wet. Very wet. Lots of fog and rain. The rain isn't heavy - what we called "sprinkles" back east - but it is continuous in the winter months. There have been years when it clouded up and started raining in late October and we didn't see clear skies until April or May. I used to tell people that any time the ground got dry in Oregon it was a drought. However, in the last 20 years it has been much dryer, and we have had some horrendous forest fires. Fujita's attacks were just 75 years ahead of time.

-

There was a very good story with lots of photos about these submarines in Sea Classics magazine. It also has a first hand account of the pilot from I-25 Flying Officer Fujita who bombed the Oregon coast on 9 September 1942. Sea Classics, Vol.4, No. 1,January 1971, page 44

-

Auto login failure

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Using the MSW forum - **NO MODELING CONTENT IN THIS SUB-FORUM**

The problem resolved itself a couple days ago. I use the Thunderbird browser, and occasionally the programmers screw up something when they post updates. I had checked Thunderbird's list of auto logons and the user ID and passwords were all there, but the program just wasn't using them. They occasionally do stupid things to improve "security" that prevent users from doing things like opening PDF files and such. Eventually they receive feedback (although this is almost impossible to accomplish) and correct the problems. My guess is that is what happened with the auto logon failure. There was a new update recently (Monday?) and auto logins started working on MSW and other forums. So that seems to be the answer. -

Roger, Thanks for pointing that out. I had noticed those odd "bilge keels" and wasn't aware of keel condensers. A quick search brought me up to date. l learn something new every day (at least I hope to)!

-

Decal Solution Questions

Dr PR replied to hof00's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

You might try posting the question on model railroading forums. They use a lot of decals on engines and rail cars. I have used a decal wetting/setting solution in the past but I don't remember much about it, and I don't recall any "super strong" versions. I certainly am not an expert with decals! -

Dowmer, Thanks. This build started out to be a theoretical revenue cutter of about 1815, but it seems to be morphing into a similar vessel of the 1820s or 1830s. All the choices do slow things down. I may be slow but that is a good thing because I might be going the wrong direction.

-

I have made a command decision! Although there are a number of inaccuracies and some speculation in this build, I have tried to be accurate where possible. But model ship colors for vessels prior to the mid 1800s are mostly pure guesswork. In some cases there are some published standards or regulations, but mostly it seems, like everything else on ships of earlier periods, things were done as things were done. The colors of masts, spars and tops were not well documented before photography came along, and even then the early black and white photos tell little about colors, just shades of grey. For the early 1800s masts seem to have been wood colored, perhaps with varnish or oil finishes. But some were painted. References like Nelson's orders to paint mast bands the same color as the masts before the Battle of Trafalgar tell us that, but don't say what colors were used for the masts. I have examined many drawings and paintings of schooners in the early to mid 1800s and have found nothing that shows colors. In a very few cases the tops of early 1800s schooners appear to have been painted white. But some tops were dark, and masts were always lighter. It seems to have been the practice in the British Navy to paint tops black (at least some contemporary models have dark or black tops) and many American vessels followed British practice. Later in the mid 1800s white mast tops became common. Perhaps this happened because the British and American navies changed the color of the band on the hull along the gun ports from yellow to white. The ready availability of white paint may have led to it being used elsewhere, such as deck furniture and mast tops. For whatever reason white was normal on these parts after the mid 1800s. I would have preferred white tops because it shows details better. But I would have had to paint the mast bands and eye bolts black. And my model is of an early 1800s vessel, probably before white came into use (it has yellow gun port bands). So I decided to go with black tops. Mast and spar color was another matter. But in reviewing several discussions on the forum I came across a reference to the introduction of straw colored paint sometime in the early to mid 1800s. By the end of that century masts and funnels, and even parts of superstructures, were being painted straw color. Look at the ships of the Great White Fleet. And the straw color has continued to be used throughout the 20th century and even until today on some ships of the US Coast Guard (the Eagle, for example). And since revenue cutters were part of the Revenue Service, the precursor to the Coast Guard, it seemed straw colored masts and spars were appropriate. I have always liked the colors on Coast Guard vessels. So black tops and straw colored spars it is in Phil's Revenue Service! And as was common before any standard colors were defined, I mixed some brown, yellow and white paints to make my own straw color.

-

You are absolutely correct. In photography lighting is the most important part of getting a good photo. I do a lot of outdoor wildflower photography and cloudy bright days are the best because there is a lot of white light (from the clouds) from all directions, not much blue light (from the clear sky), and no harsh shadows. Indoors I try to simulate this with a diffuse white light. Controlling the shadows is key to bringing out textures, curves and such.

-

Valeriy, When you started these boats I assumed they were personnel boats - the captains gig and such. But with the armament, and not a lot of cabin space for personnel, I wonder how these boats were used? Not only are your modelling skills excellent, but your photographic skills are equally good. This allows us to appreciate the quality of your work. Photography is one of my hobbies, so I was wondering what camera and lens you are using to photograph your models?

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.