-

Posts

40 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Posts posted by John Ott

-

-

Marc, your ship needs no rationale or excuse. As model-building in styrene, I've never seen anything like it.

Apocryphal = my status as a middle-class wage-earner in 2023.

Epipelagic = surface waters of the ocean. In other words, don't sink!I pick up strange terms as a science illustrator. —John.

-

(So several months back, I had this huge big plastic model ship kit. Wondering how I was going to paint it. This is what I wrote back in May—)

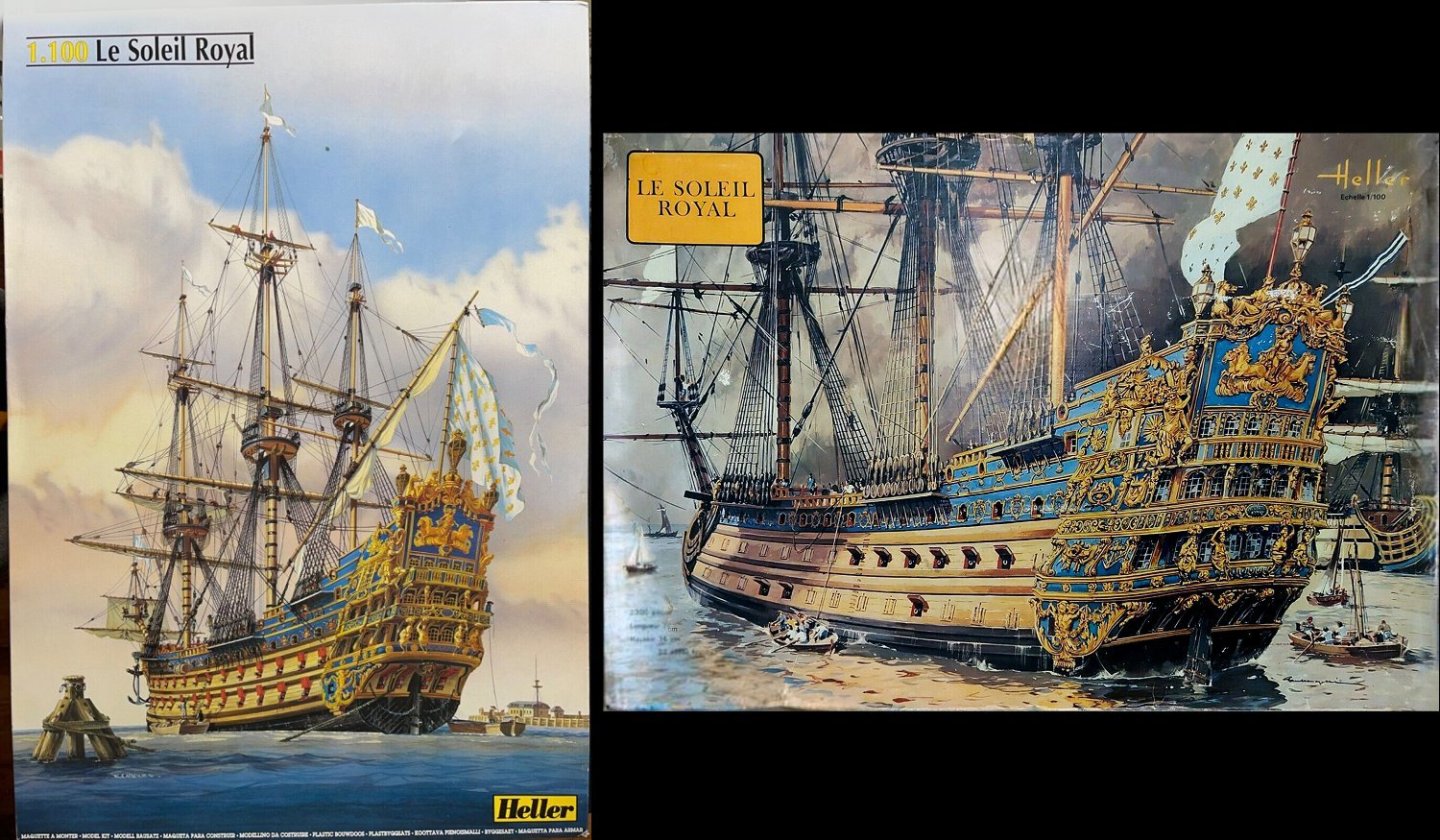

If you’re anything like me, you’ll agree that Heller’s Soleil Royal is a striking beauty in the box art, all blue and gold. As if the shipbuilders for le Marine Royale were UCLA alumni (go Bruins!)

In the last decade or so, there has been something of a pushback on the Heller color scheme (and not just from USC Trojans). Maybe the Soleil Royal wasn’t blue after all. A few things prompted this.

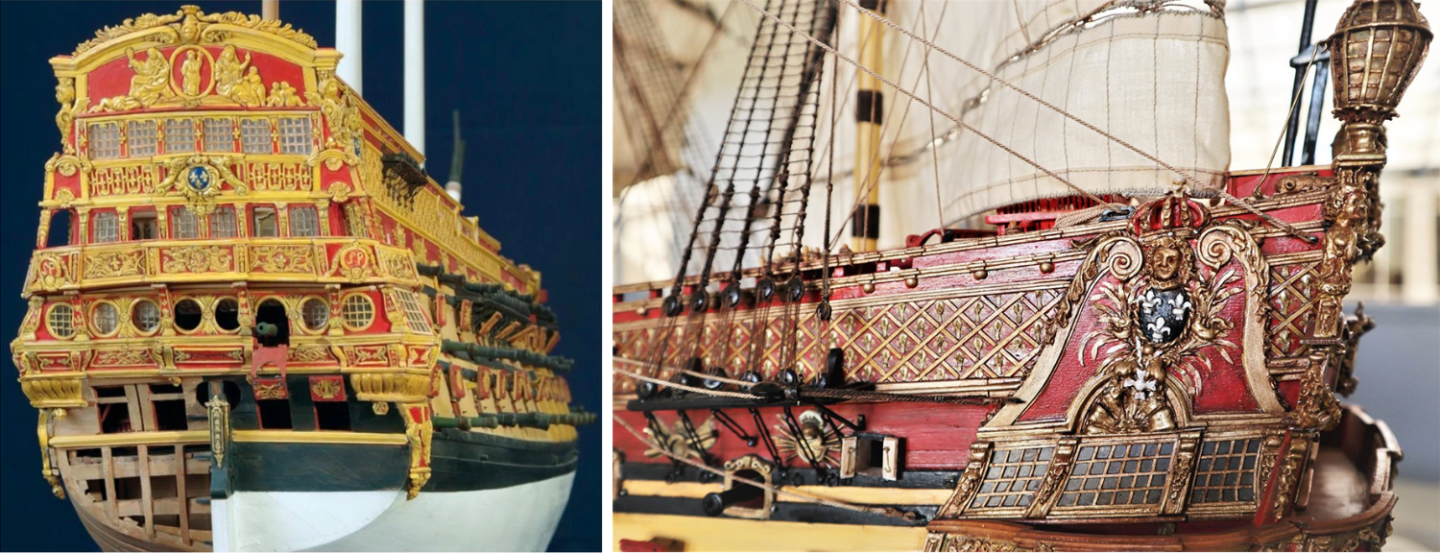

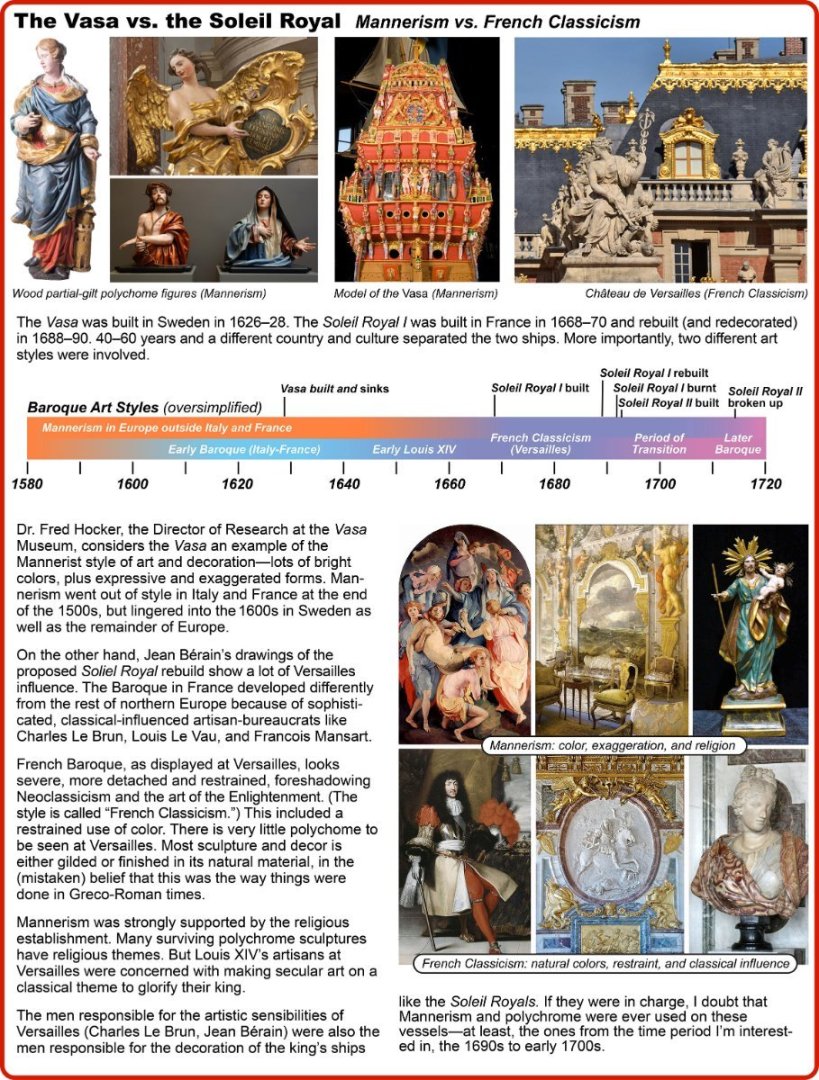

First, there was the late-1990s revision on how the Swedish ship Vasa was interpreted. The 1628 warship, pulled up mostly intact from Stockholm harbor, still had traces of paint, but it took decades to thoroughly examine it. From prior thinking—that the Vasa was blue and gold like the Heller Soleil Royal box art—scholars changed their minds and have now determined that the ship’s upper reaches were mostly red. Plus, the ship’s wooden sculptures weren’t simply gilded—they fully painted in many colors (polychrome). Thoughtful modelers wondered if the Soleil Royal wasn’t likely to have been red too, and if the sculptures were likewise brightly painted instead of uniformly covered with gold leaf.

The gold leaf itself was another issue. It was pointed out that there was far too much gold on Heller’s version of the ship. It couldn’t all have been gilding. Even Louis XIV couldn’t afford that. Someone went into the French naval archives and figured out that the gold leaf budget for some premiere rang warships was barely enough to gild a figurehead. Applying gold leaf to the working surfaces of the ship—rails, ports, or anywhere in contact with abrasive ropes, tools, hands, etc.—was impractical in any case. Might as well take handfuls of Louis d’or and toss them into the ocean, since the gold would end up there anyway. So gold leaf—nope—most of it had to have been yellow paint.

The next prompt came from comments made by author J.C. Lemineur and others, pointing out an alleged scarcity of blue paint in the 1600s. It was claimed that blue pigments were expensive and hard to come by in quantity. “Blue-shade paints were therefore mostly avoided,” Lemineur wrote in his monograph on the 1693 three-decker Le Saint Philippe. Following Lemineur, modelmakers restored their Saint Philippes in red and gold.

Some Soleil Royal modelers absorbed all this, plus the information from the Vasa, and revised their thinking about how the Soleil should be painted. In some cases, they straightaway swapped all the blue for red.

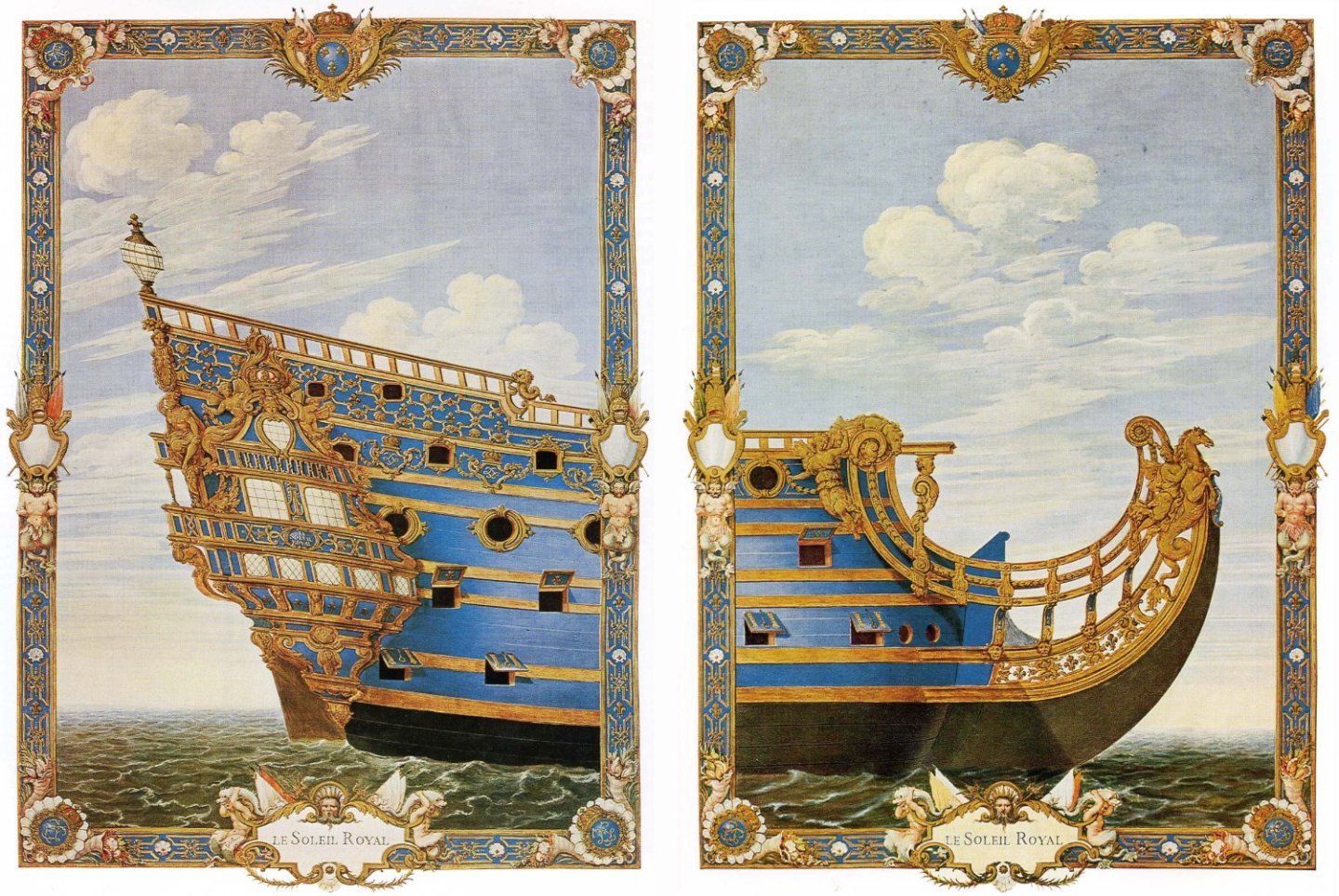

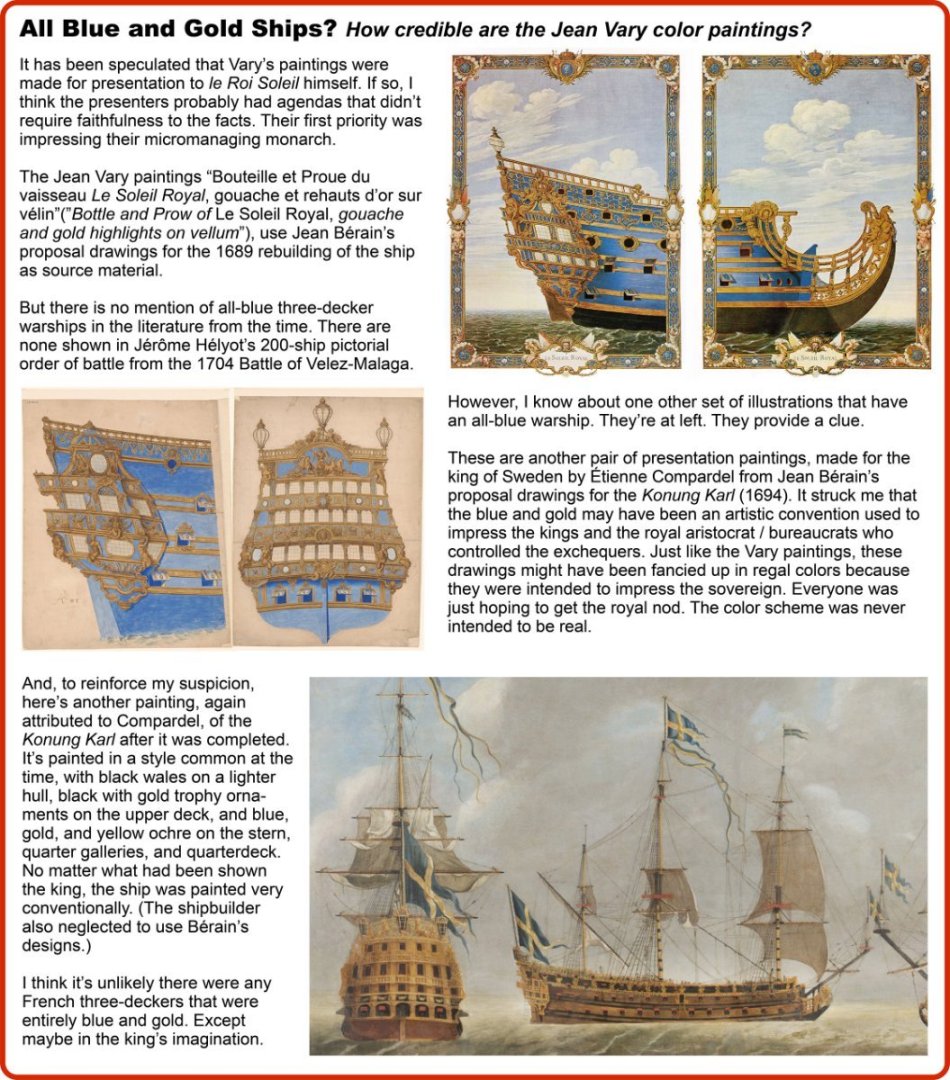

Another red herring dragged across the modeler’s path was the set of c.1689 paintings of Soleil Royal’s bow and stern made by Jean Vary. These showed the ship all blue, stem to stern, main wale to sheer. Wow!

This gave Soleil modelers even more options, some opting for the traditional Heller paint scheme, others going off in a red direction, others going all-blue.

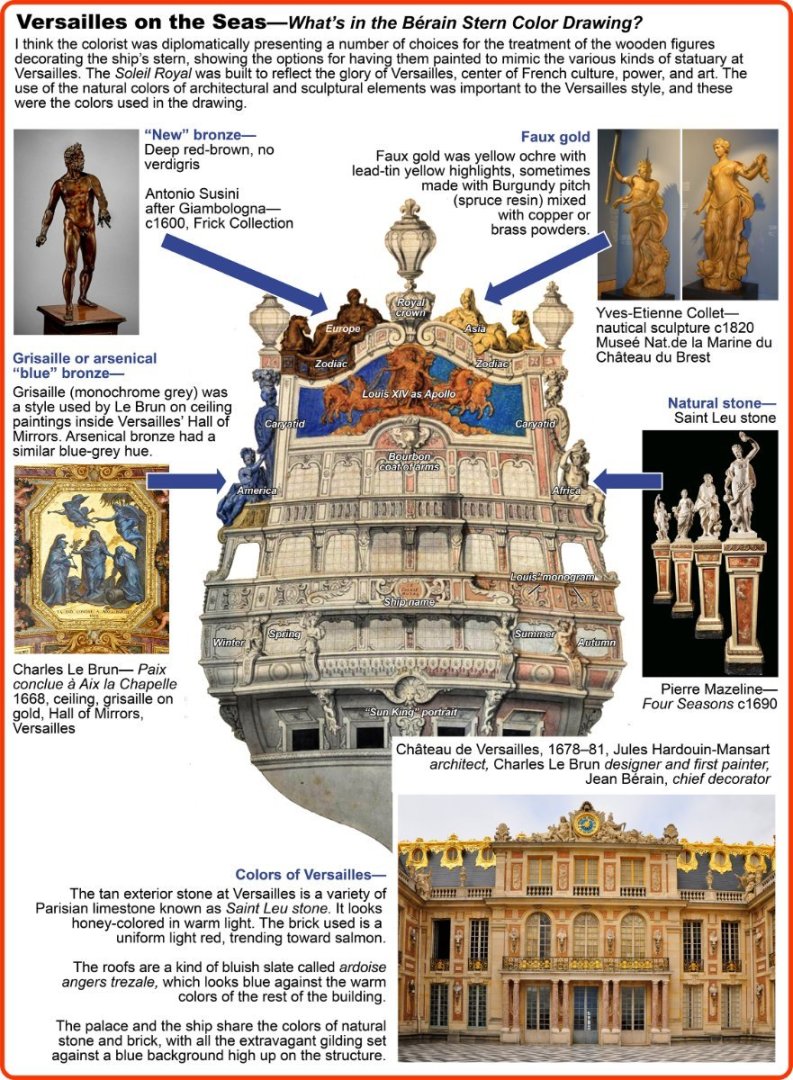

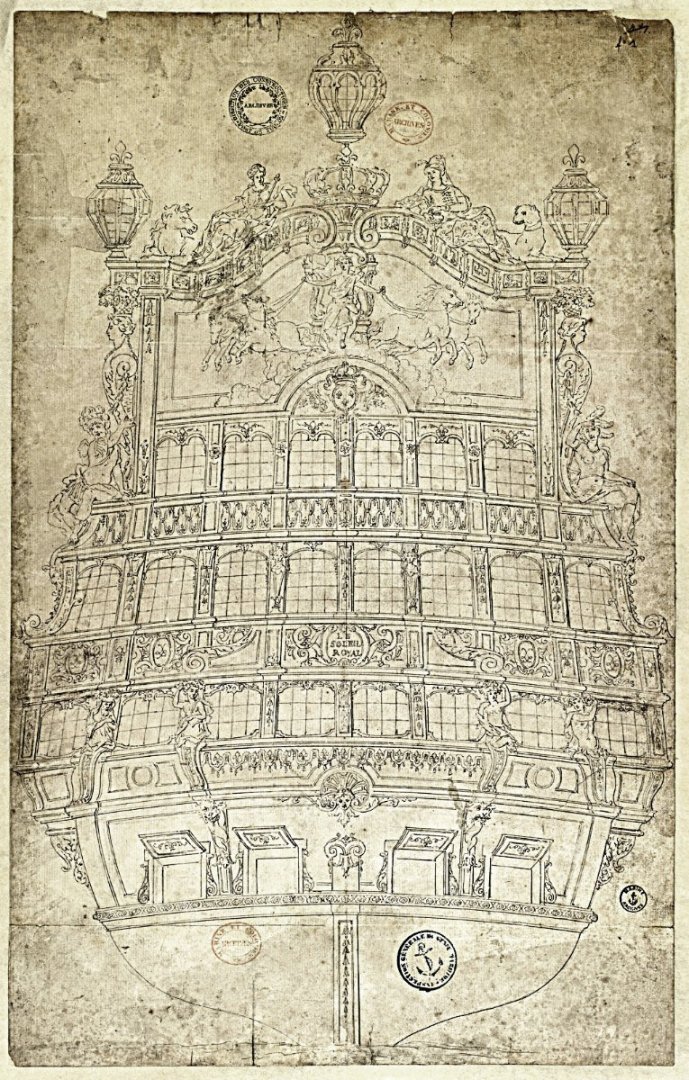

Finally, there was a fourth bit of drama. It was noted that one version of the Jean Bérain drawing of Soleil’s stern had color indications—

Some parts light red, some a kind of tan, deep blue on the stern plate, and the figure carvings are in several different color treatments. What was up with that?

So I pretty much know the Heller kit's paint instructions are, um… apocryphal. There couldn’t have been that much gold leaf on a real warship, and the whole issue of whether or not it was actually painted blue was being questioned. How should the Soleil Royal be painted? More important to me, how was I going paint my ship? Was it possible to untangle all this information and come up with a likely and justifiable color scheme? Hold my beer.

Please keep in mind that the following information is the product of someone who is admittedly sometimes a mad modeler and a dunderhead, poster boy for the Dunning-Kruger effect. Marc LaGuardia's (Hubac's Historian's) build log is a better informed source. If it’s important to you, always do your own research and come to your own conclusions! And paint your own ship however it makes sense to you.

First, it should be remembered that there were three Soleil Royals in Louis XIV’s reign. (This was discussed in the last post.) Paint never lasted very long in a marine environment—ask any former Navy swabbie. Given the need for frequent repainting, it’s not likely that the three ships had only one paint scheme between them. They undoubtedly changed, year to year, refit to refit. And tastes changed too, over the forty-year period the three ships sailed, as did the artisans and bureaucrats who decided such things. Point number one to consider—the Soleil Royal(s) likely had several paint schemes.

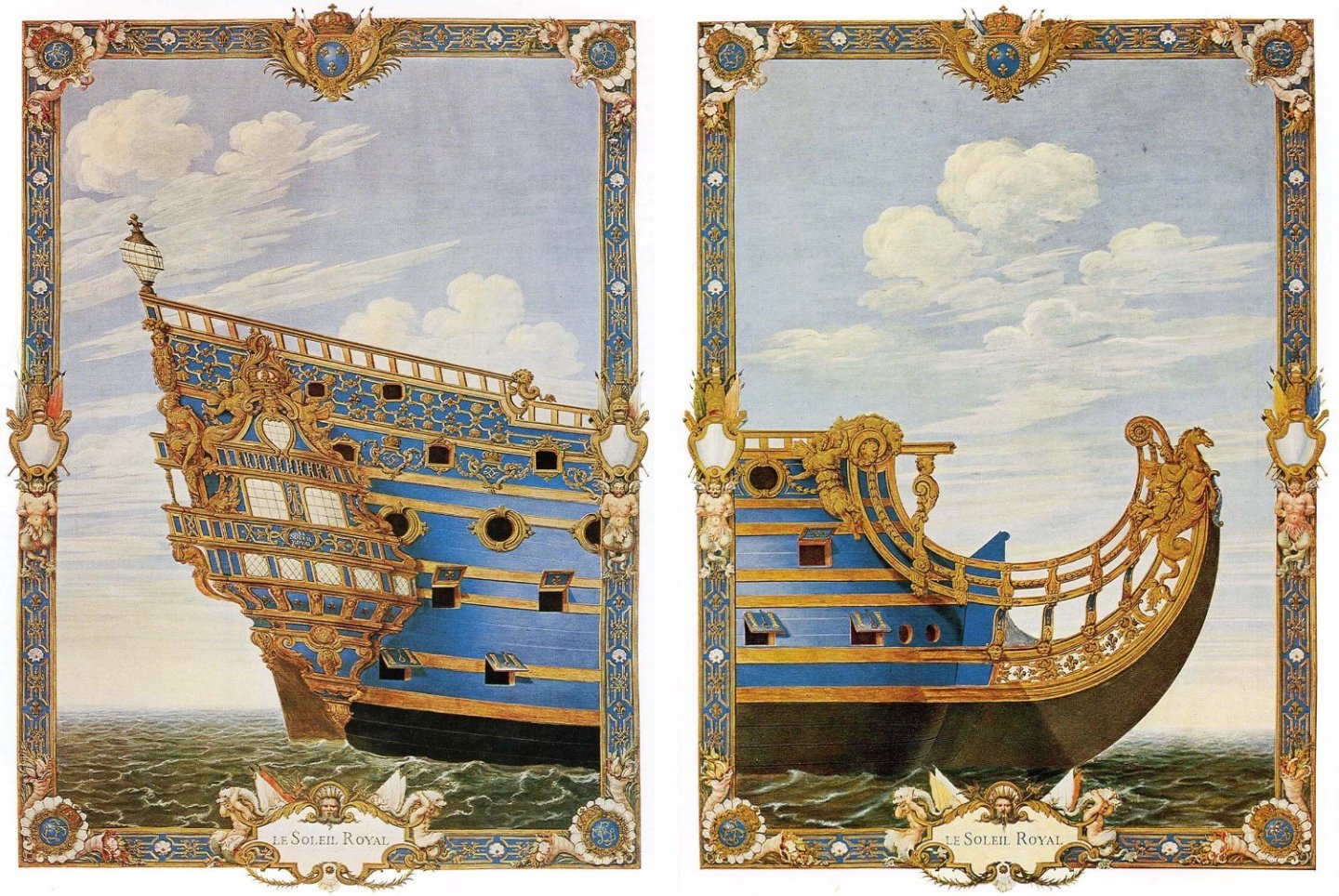

That being said, the Soleil Royals got associated with blue paint early on. Blue was a logical color for a royal ship. Besides being a mobile gun platform, a French warship was intended to proclaim the might and majesty of the Sun King and his Bourbon dynasty wherever it sailed. Blue, gold, and white were the royal colors. The Bourbon coat-of-arms had gold fleur-de-lis on a blue field.

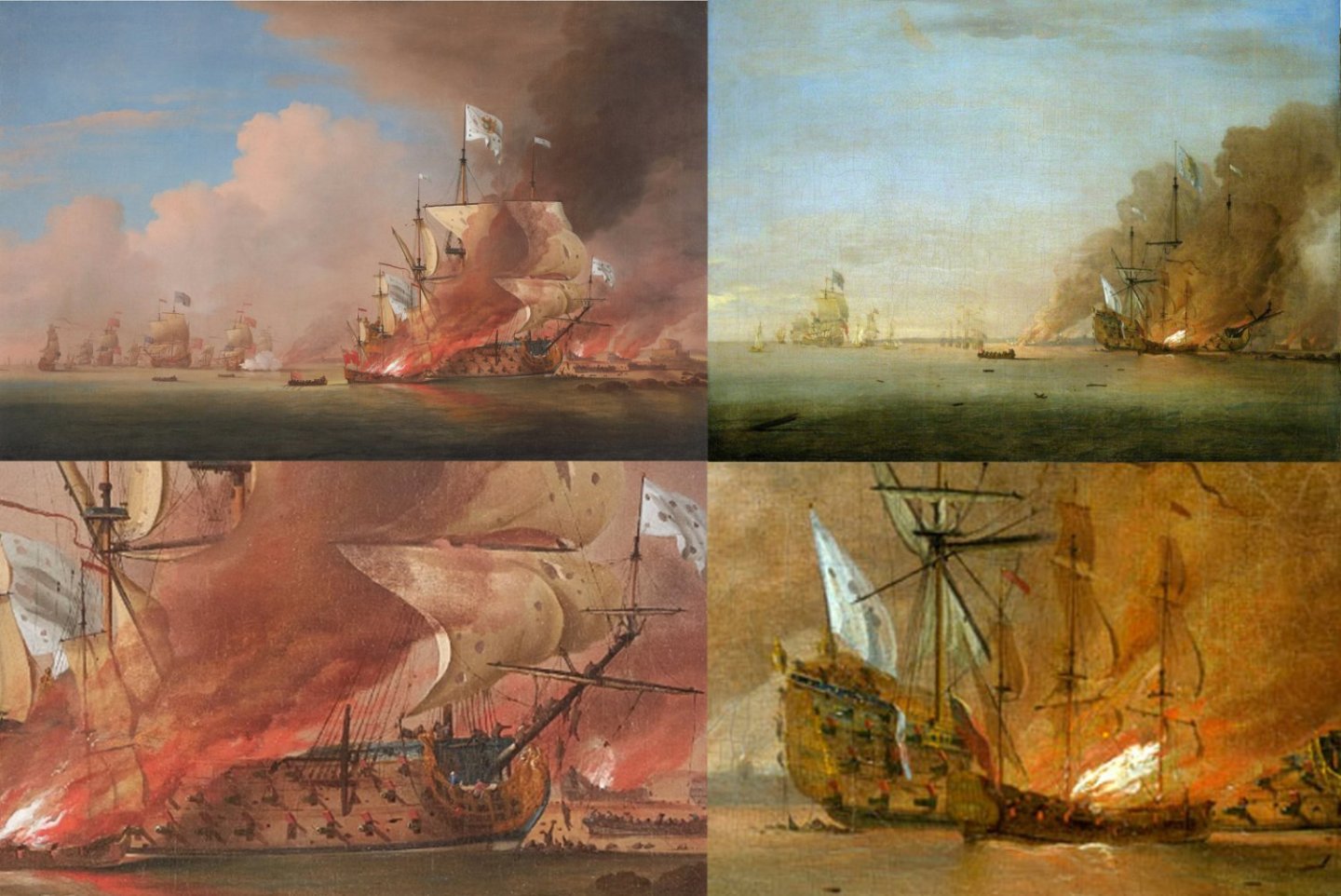

In much of the art from the early 18th century, the Soleil Royal I(a) is shown with blue on the hull above the gundecks, like in these details of paintings by English artist Peter Monamy dramatizing the destruction of the ship at La Hogue in 1692. Monamy was known for his accurate depictions of naval battles and ship portraits, and he made these paintings when the battle and the ship were still recent history.

Keep in mind that right-hand image, with light blue on the quarterdeck level and dark blue (with gold fleur-de-lis) on the poop deck level above it. Hmmmm.

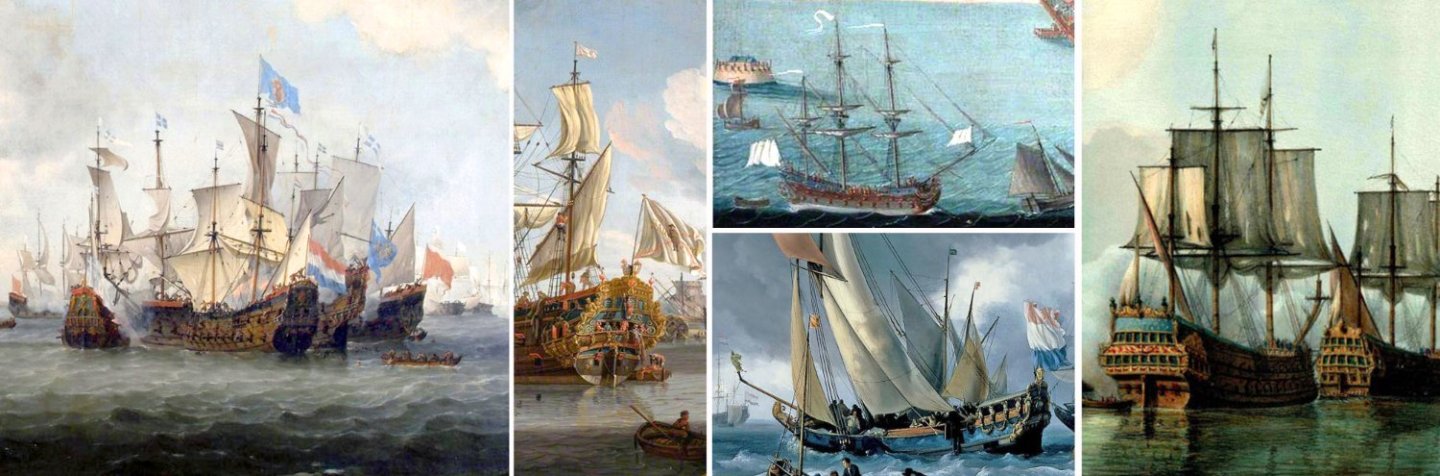

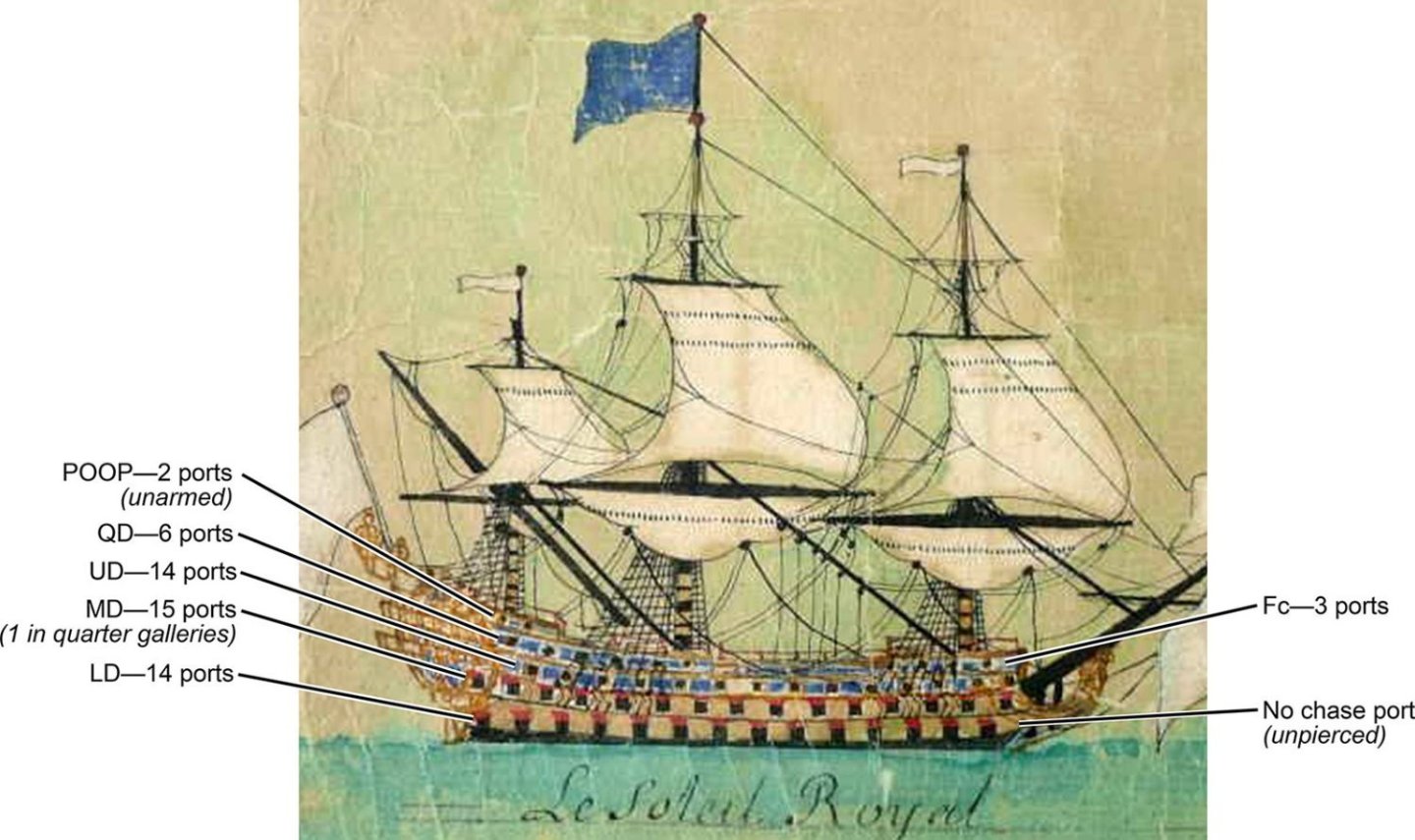

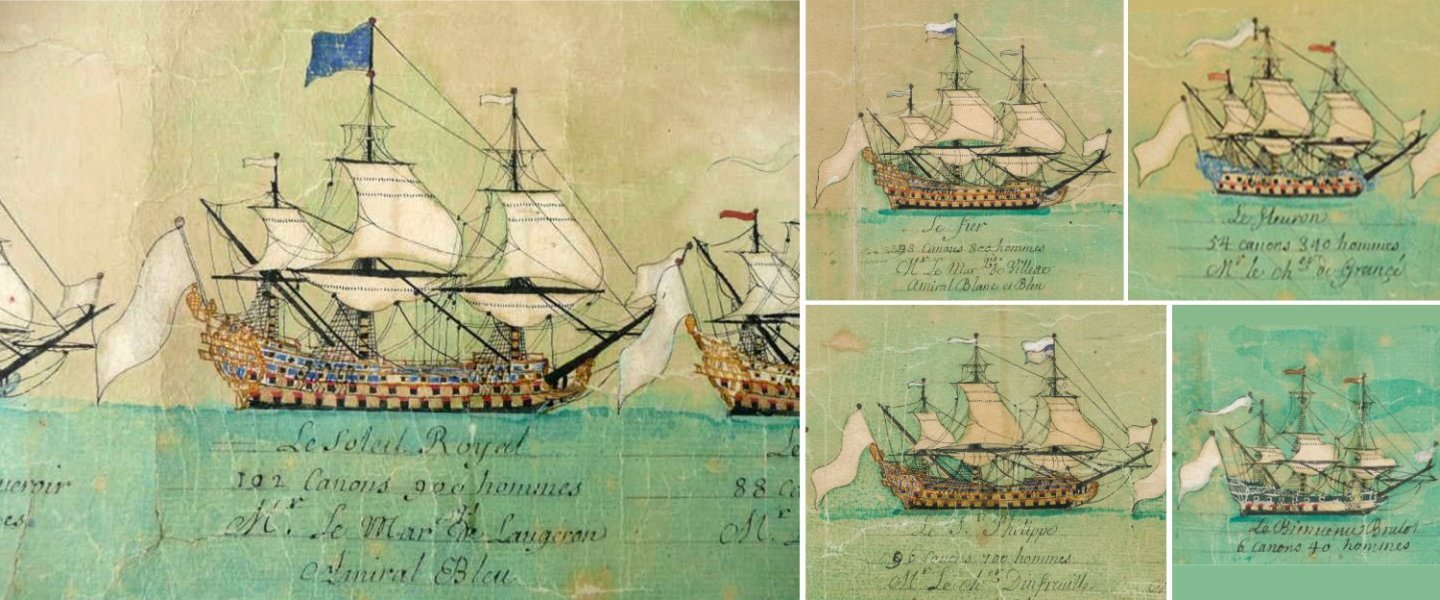

And here’s the image of the Soleil Royal II on the 5-meter scroll painting of the order of battle for Velez-Malaga in 1704, made by eyewitness and battle participant Jérôme Hélyot.

Ship’s got the blues. From the upper gun deck up, and some on the middle gun deck level of the quarter galleries.

So at least two versions of the ship were painted blue above the gun decks after all. The Heller box art wasn’t that far off. But what about those claims of blue pigments being rare in the 1600s?

Turns out, maybe not so much!

Some blue pigments were rare, or unavailable in large quantities, or unsuitable for ship paint, or simply not invented yet. Ultramarine blue (lapis lazuli), a powdered gemstone from faraway Afghanistan, was worth more per weight than gold and was used only for things like painting the royal crest on first-rate warships. Smalt was blue pigment made from ground potassium-cobalt glass. It wasn’t available in quantities large enough to paint a ship. Plant-based indigo (woad) made poor paint that faded fast in sunlight; it was a better clothing dye. The synthetic pigment Prussian blue (Paris blue) wasn’t invented until 1706. Cerulean and cobalt blues weren’t synthesized until the 19th century.

Yet many ship paintings from the Baroque period show blue-painted ships.

There’s even a book that discusses it—The Colour Blue in Historical Ships, by Joachim Mullerschon. There are several more blue-painted French ships on Hélyot’s scroll, including— ironically— the supposed-to-be-red Saint Philippe from Monsieur Lemineur’s monograph mentioned above. It had blue above the middle gundeck just like the Soleil Royal. At least, it did in 1704. Huh!

So where were French shipwrights getting blue paint?

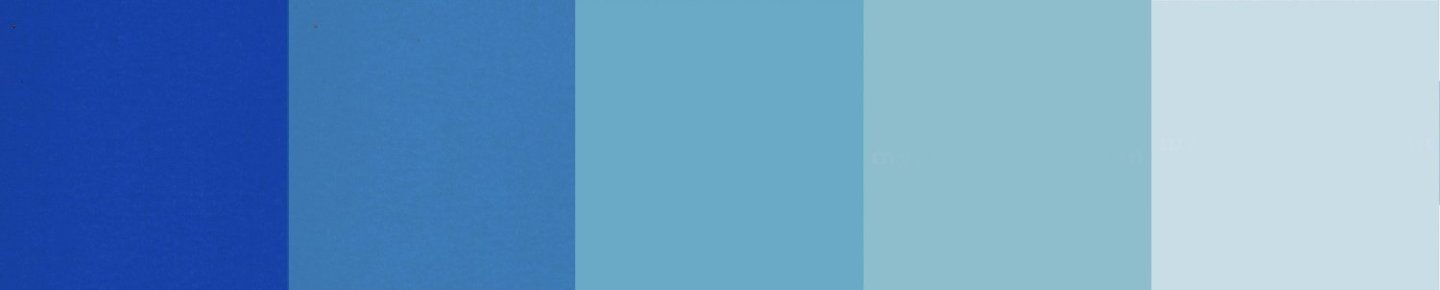

Azurite (azure, azul) is a deep blue copper mineral mined near Lyons, France. It was the most important blue pigment used in the middle ages. By the 17th century, it had been synthesized and manufactured in quantity by mixing copper nitrate with calcium carbonate (chalk). The inexpensive synthetic pigment was called blue verditer (Bremen blue, blue bice) and common enough to be used as wall paint during the 1600s.

Verditer comes from verd de terre (earth green) because natural azurite often came mixed with another greenish copper ore, malachite (copper carbonate hydroxide). Depending on how much malachite was in the mix, azurite could be green or a greenish blue. But synthetic blue verditer could be close to cerulean or cyan in hue. See the swatches below. Blue verditer was often mixed with lead white to make a light blue shade (Versailles blue), or with lampblack, to deepen it.

Blue verditer isn’t used any more because it needs other paint binders, like casein, rather than common linseed oil and turpentine. Linseed is too acidic and causes the pigment to degrade to dull olive green or black in time. Ship paint rarely lasted long enough for that to happen.

Yes—there was plenty of blue paint to paint ships with in the 1600s.

But were any of them painted all blue, like in the Jean Vary paintings?

What about the Vasa being red with polychrome figures? Was it possible that some version of the Soleil Royal had been painted that way? Well… maybe. We don’t know how the Soleil Royal was painted when it was first built by Laurent Hubac in 1668–70. From the look of his ships, Hubac built with a large helping of Dutch influence, and the Dutch painted their ships with a lot of color. Color was an important component of early Baroque art in Northern Europe. The art style is called Mannerism. It was a holdover from the styles of the Late Renaissance, and by the mid-1600s it was still popular everywhere, it seems, except around Versailles and the French court.

As head of the French navy, Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert tried to separate the decoration of the royal ships from the actual shipbuilding, with different officials presiding over each function. The same artists and designers working at Versailles were given the job of designing the decorations for the ships, but management was limited to an exchange of letters and drawings. We don’t know how that played out in the shipbuilding port of Brest, which was isolated out on the western tip of remote and rebellious Brittany. It could have been that all those independent, conservative shipbuilders took direction well and dutifully painted the new warships in the approved Versailles style. But maybe Colbert's instruction letters went into la poubelle with the fish wrappings. I think it’s at least possible that Dutch-trained Hubac still had a say in how his ships were painted, and that would have included using a lot of Mannerist-styled color.

On his log on this forum, Hubac’s Historian (Marc La Guardia) has an absolutely beautiful partially-scratchbuilt Soleil Royal that I would place as painted in the Mannerist tradition. It’s the most amazing Soleil Royal model I’ve ever seen! If there were no Soleil Royals painted in the Mannerist tradition, Marc shows us that there should have been!

Laurent Hubac died in 1682 and by the late 1680s, the Royal bureaucracy at Versailles was in full control of the shipyards. Jean Bérain was filling in for the aging Charles Le Brun as chief decorator of the king’s warships. From surviving documents we find out that Bérain exercised more control over the process than his predecessors. His detailed drawings of ornamentation and sculpture were apparently followed, and we can suppose his chosen colors were too.

What about that one version of the Bérain stern drawing with the color indications? The one with the odd-colored statuary? How do we interpret that? Well—it not only shows all the signs of French Classicism in action, it also directly invokes the architecture of Versailles. Remember that Jean Bérain was the chief decorator of the palace.

But I’m more interested in working up a color scheme for the 1693 Soleil Royal II. The end of the 17th century was an age of bright yellow sterns.

Ludolf Bakhuizen, Battle of Barfleur

L to R—Konung Karl, Le Foudroyant (actually painted in 1834, but I like it), Le Royal Louis.

The sketch of the Soleil Royal II on Jérôme Hélyot’s 1704 scroll of the Battle of Velez-Malaga shows a ship that looks like it fits right in with that paint scheme.

What would this look like on the model?

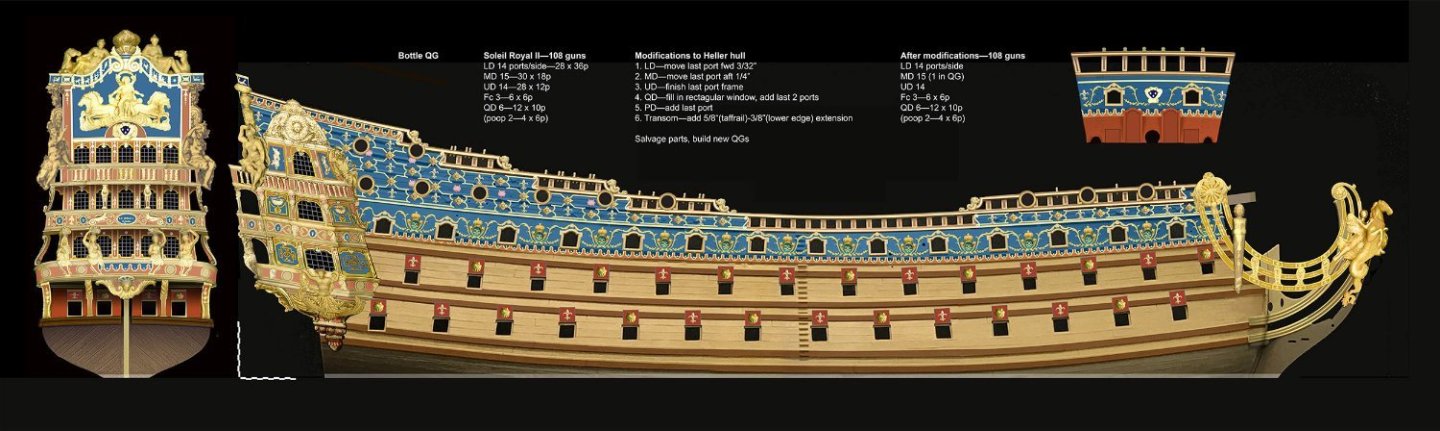

This is one of my Photoshop/Illustrator sketches—I made several. Okay, fine—but what about separating the decks? Specifically, separating the upper gun deck from the quarterdeck? The way I drew it, they have two different ornamental schemes going on. (I’ll discuss the decorations in a future post.) How about going dark blue / light blue, like the Konung Karl in the All-Blue-and-Gold-Ships box above?

Cool. But now, what about the poop? Maybe the poop should get its own decoration scheme. Dark / light / dark?

And yeah—the poop now gets some fleur-de-lis on a dark blue field, similar to other period French warships depicted in art. (See that Monamy painting at the beginning of this post.) Each deck now has its own color and ornamentation. I stared at this variant for about two weeks before deciding I liked it best. Finally decided, you know, I could live with this.

Okay, so—paint! How should I approach painting this plastic model?

If we were absolutely true to our perception of scale, all small ship models like Soleil Royal would be built with smooth styrene. Not a hint of texture. There’s hardly any texture to finished and painted wood anyway, and certainly none that would be detectable in 1/100 scale. I dislike many small-scale models made of real wood for this very reason—real wood grain doesn’t show up on that small a scale!

This is not what most modelers and viewers expect. They like to see indications of what the thing being modeled was supposed to be made of. Wood should—in most viewer’s minds—look like wood. Metal should look like metal. Stone should look like stone. Never mind that at 1/100 scale, everything should look like smooth plastic.

Besides, modeling and painting textures is really cool. The Heller die-makers certainly thought so. They did a hella (Heller) job of giving the sides and decks of the Soleil Royal a great-looking raised wood-grain texture.

This sets up an interesting dialog. The real ship was a fairly new, well-kept, premier rang warship that was also a national symbol, cared for by hundreds of low-ranking swabbies with an officer-enforced mandate to keep all hands busy. (“If it moves, salute it; if it doesn’t move, paint it.”) In other words, ships like the Soleil Royal should look almost new.

On the other hand, modelers love to age, weather, wear, begrime, and texture surfaces. The Heller model invites this. I don’t want to sand away all that nice wood grain. Likewise, I don’t want to paint over it and pretend it’s not there. I can’t resist the temptation to work with it. At some point, the casual model-builder (me) has to shrug and go with the flow. I’m left trying to find a middle ground between this—

And this—

(The Victory and Neptuno are, IMHO, just really, really big model ships.)

But I’m not much of a fan of weathering. To my mind, a model ship should look like it has had at most a few weeks at sea, not months and years of neglect.

So I’m going to try and make the Heller wood grain subtle, but still present. I’m not going to emphasize joints and plank edges with subsequent washes of detail-enhancing dark color. Decks will look used but well-scrubbed. The hull can look like it has weathered one hard blow off Ushant, but no more. No nails, bolts, trennals or other passages for the Big Wet to penetrate will be visible.

And not much attention will be given to places where I don’t want to attract your eye. Forget about seeing much beyond featureless light grey below the waterline, I don’t want your attention there. And I’ll be using the old illustrator’s trick of using flat black on any details that I want to disappear. Hopefully, the end result won't look too different from my Photoshop sketch.

(Nope, it didn't.)

Next week I'll go through the process of painting the lower hull and the decks. Stay epipelagic 'till then.

-

Hi Marc. It would be nice to think that the ship had its ornamental program finished at some point. Given that it was in the middle of a war and that there was controversy about the weight of the sculptures, I think it's questionable from a practical standpoint, but as you say, there's enough vagueness in the historical record that the answer can go either way. (Specifically, either way we as modelers want.)

I heard the term "harbor queen" used for party boats that never left port. Maybe it's a local thing. Lots of harbor queens in the marinas around southern California. -

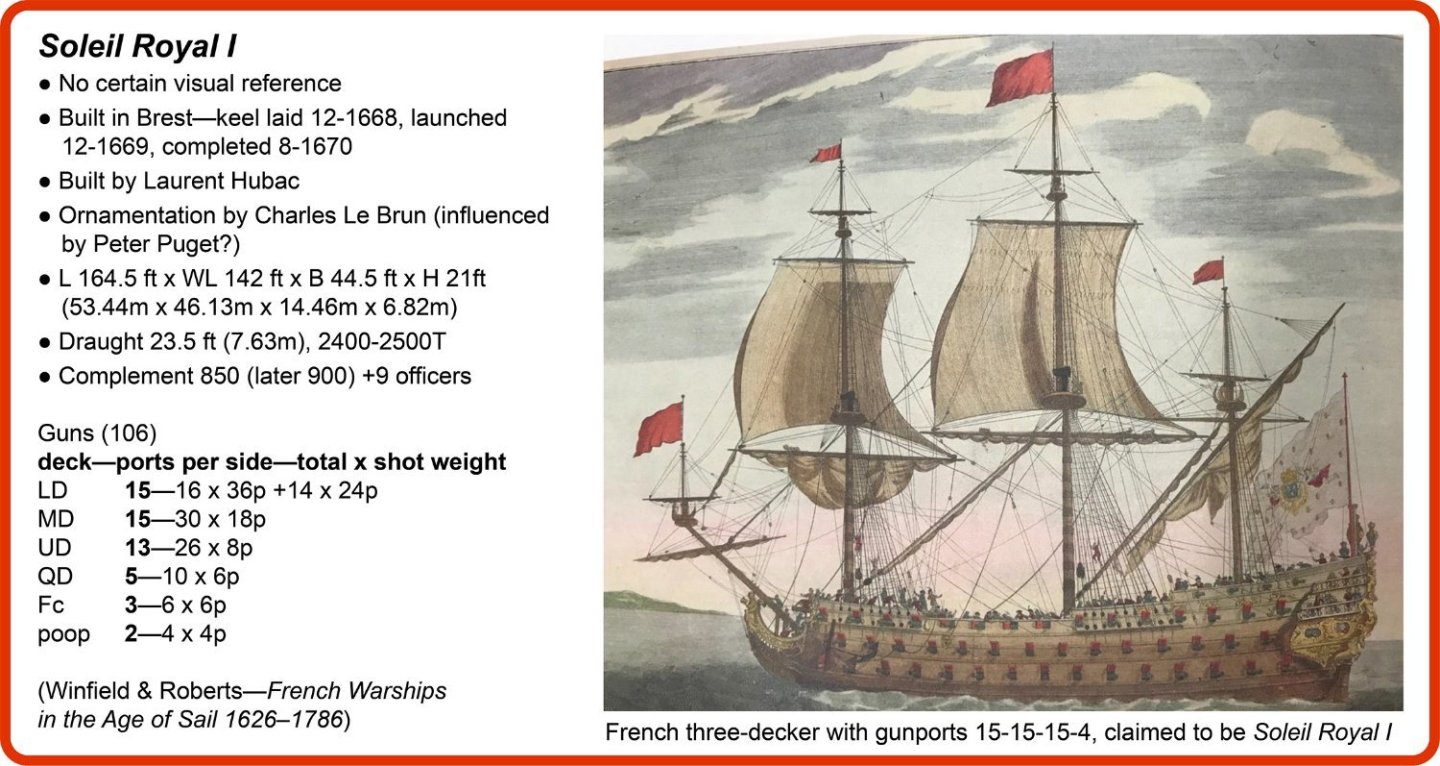

Let’s see the three Soleil Royals and figure out why I decided to build the last one. Thanks to Guy Maher and his Soleil Royal log on Ships of Scale for organizing a lot of the following information. His PDF guide to the ship is a treasure trove. (It’s in French—get a good online translator.)

The biggest issue with building any model of the Soleil Royal is simply that we don’t know much about what the ship looked like in real life. The few pieces of surviving artwork raise as many maddening questions as answers. It’s like getting a story from an unreliable narrator. In spite of in-depth research by half a century of dedicated hobbyists, we don’t seem to be much closer to finding out how the Soleil Royal really looked as we were when the Heller kit was first produced.

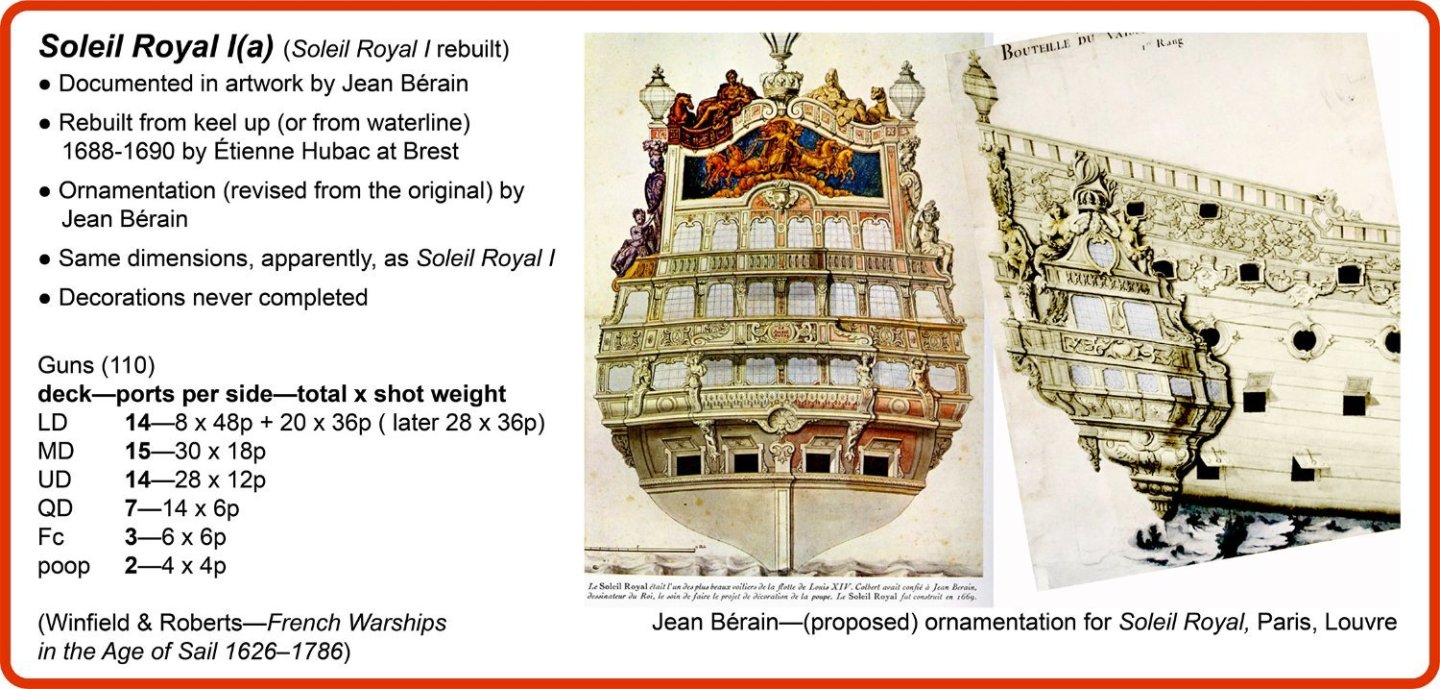

Soleil Royal I was a harbor queen at Brest for 20 years. The big 106-gun three-decker was intended to be a flagship for the channel fleet. It needed a huge crew and was expensive to maintain in sailing condition, so it was laid up and never got much attention until its timbers were so rotten that it was taken apart in 1688 and rebuilt from the keel up. See Soleil Royal I(a).

Not much is known about the first version of this ship, built by Brest shipwright Laurent Hubac (1612–1682). Hubac built around 50 ships-of-the-line heavily influenced by state-of-the-art Dutch warships. There are no surviving plans for the Soleil Royal because it’s probable that none were used in its construction. There are letters in the French archives from First Minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, head of the French navy, encouraging his shipbuilders to start using uniform dimensions and plans on paper. Unfortunately, the ship constructors in Brest were a stubborn and conservative lot who built their vessels the same way that medieval architects built French cathedrals—by knowledge and rote, without drawing plans. So the first Soleil Royal was probably built without visual documentation. Nobody bothered to draw artwork of the ship, either. We have some paragraphs broadly describing the stern sculpture, that’s all.

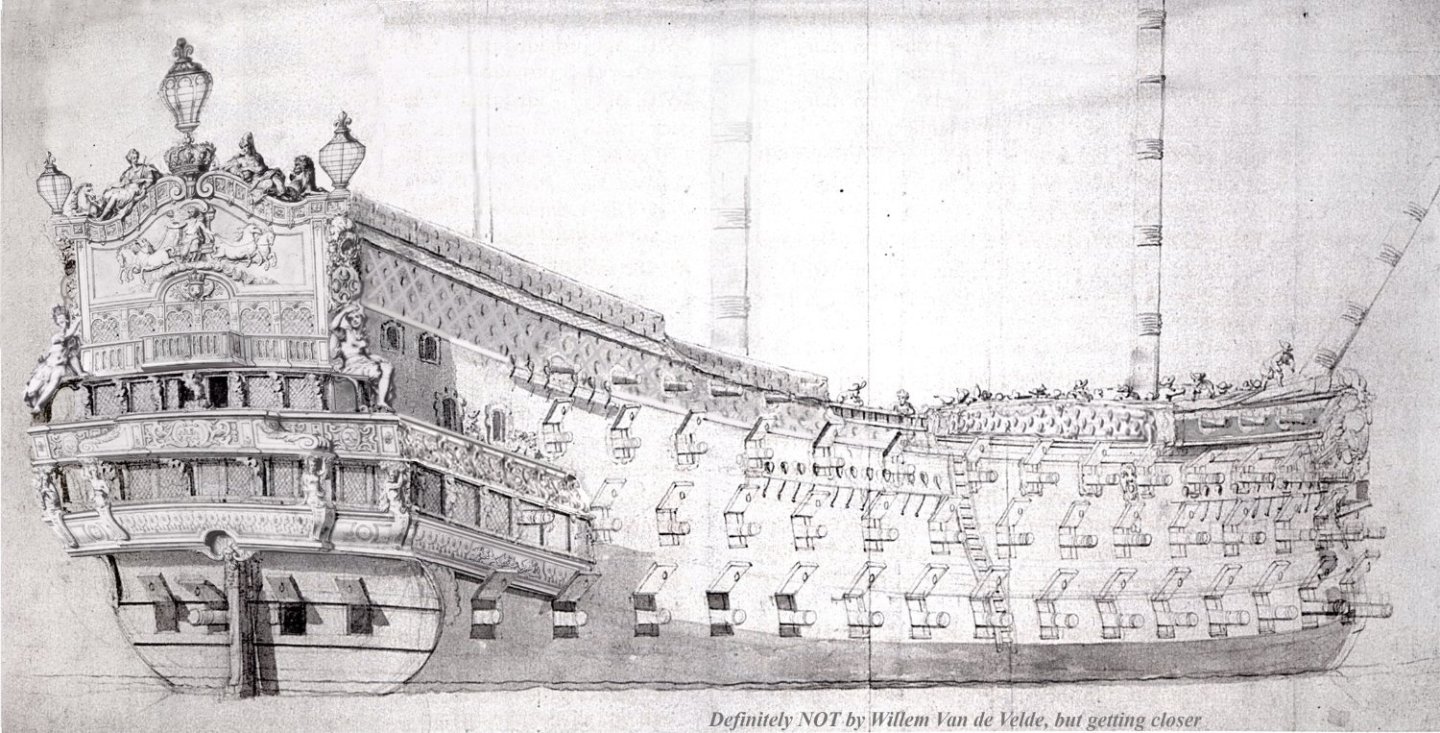

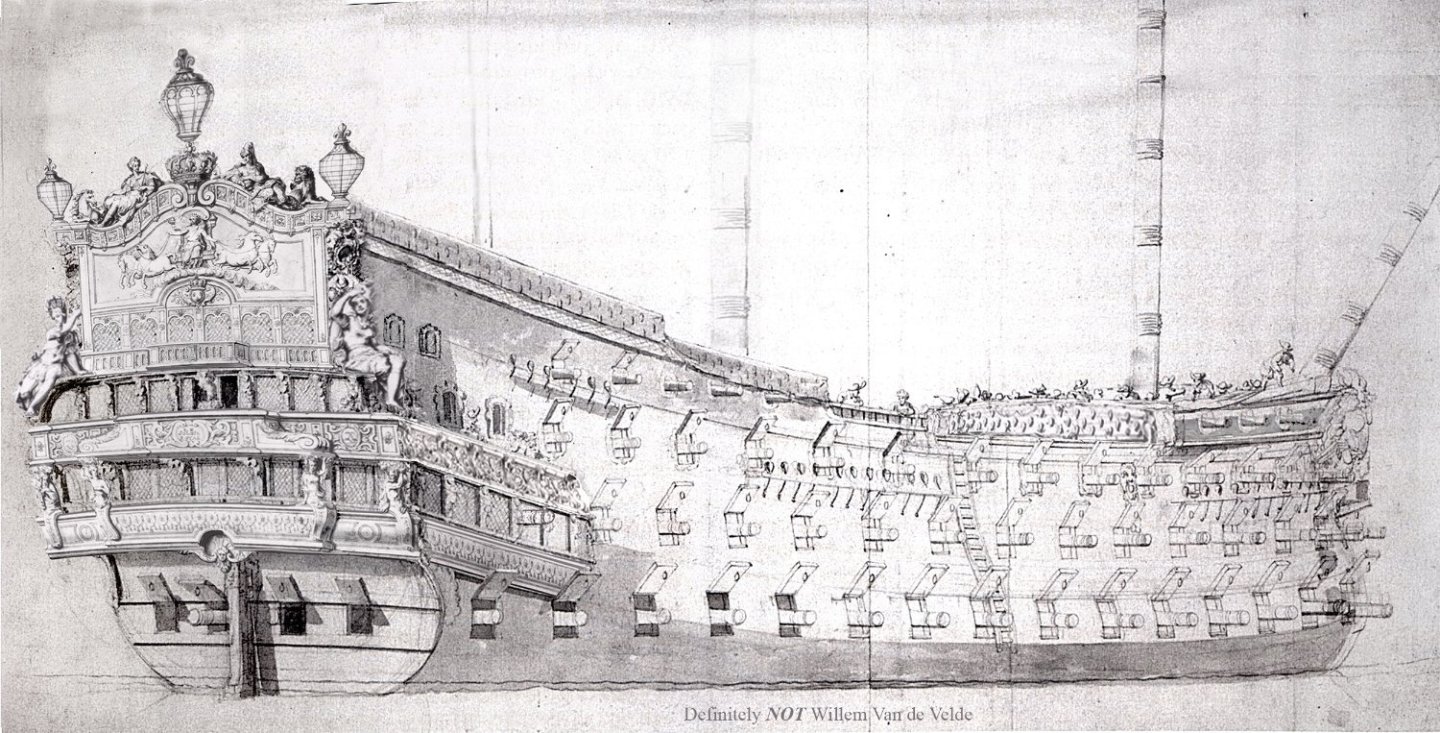

The print above is from an engraving in a 1690 book on French ships by Henri Sbonski de Passebon, and was thought to be the Soleil Royal by some authors. But Sbonski de Passebon was a galley captain in Toulon who had no opportunity to see (or draw) a ship harbored at Brest. The engraving was, at best, guesswork. It’s no good as a representation of the Soleil Royal because the numbers and arrangement of the gunports are different and it has no armed forecastle. Who knows what other details are wrong?I think a better starting point for considering how this ship looked would be one of Willem Van de Velde’s drawings of a similar ship built by Laurent Hubac in the same time period. Here’s another one of his premier rang 104-gun three-deckers, Reine (ex-Royal Duc), built by Hubac the same year as Soleil Royal. I’ll bet the first version of the Soleil looked similar. It has an armed forecastle, a fat stern (a Hubac trademark), a big stern plate, and full-figure sculptures sitting on the stern quarters, just like what the Soleil Royal was supposed to have.

If we use a little Photoshop and attach the Soleil Royal’s stern… the result doesn’t look too bad. Plausible. But—

But as the subject for a model, Soleil Royal I leaves too much to the imagination. The Heller hull would need massive modification and a lot of scratch-building to look anything like this. Too much work. Let’s move on.

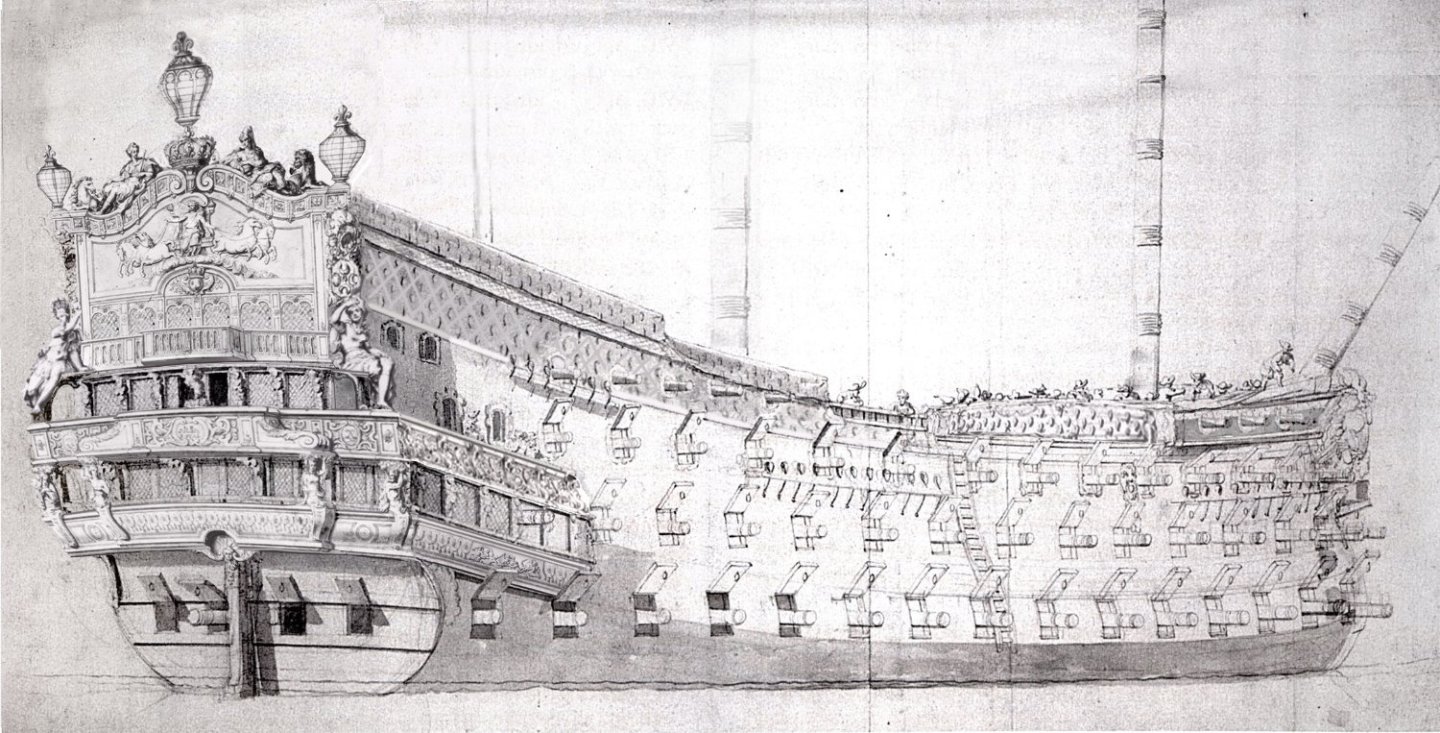

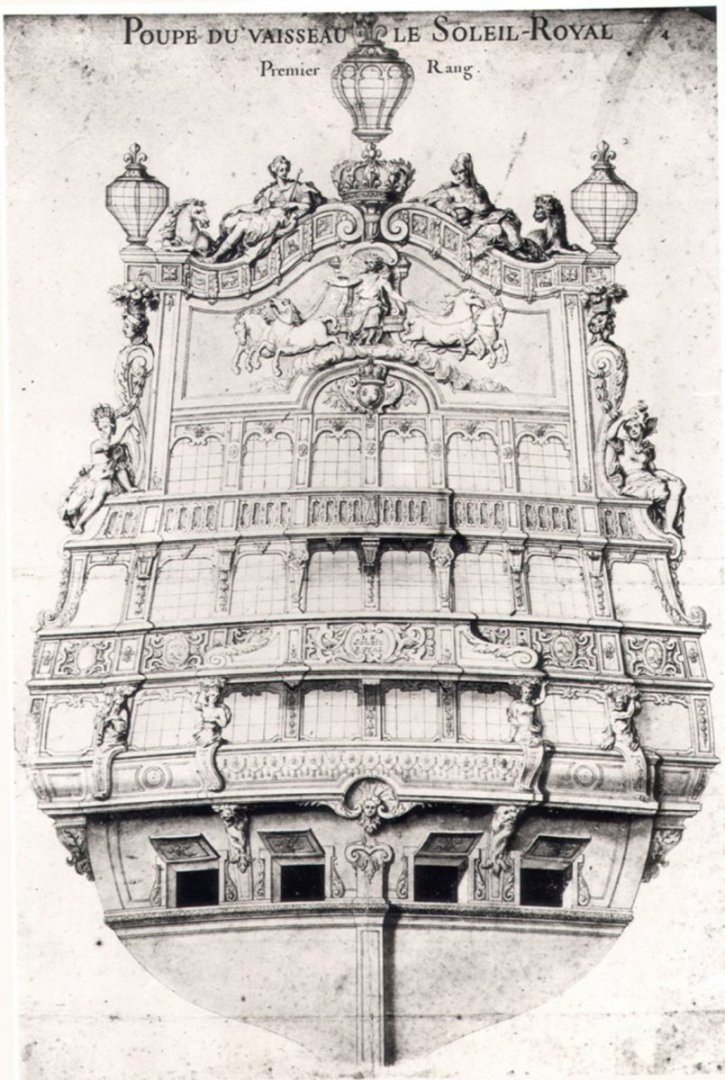

This is the version many modelers seem to want to build, thanks to the superb artwork by Jean Bérain (1640–1711), dessinateur de la Chambre et du cabinet du Roi, the king’s chief decorator, who made the drawings as a proposal for dressing up the 1688-1690 rebuild of the ship. In addition to the drawings, we have paintings, made by Jean Vary, that show the ship entirely painted in blue. (Spoiler—it probably wasn’t. This will be discussed in a later post.) These may have been made for presentation to the king, showing le monarque what his ship-decorators intended for his favorite namesake royal vessel.

The son of Laurent Hubac, Étienne Hubac (1648–1726), was responsible for rebuilding the ship. Surviving documents say that much of the ornamentation from Soleil Royal I was recovered and reused. Some of the weighty sculpture was redone in a smaller size to reduce the ship’s top-heaviness. Bérain designed “bottle” quarter galleries for the ship—all balconies enclosed. This was the regulation style after 1673.

Regrettably, there’s a good chance Berain’s designs were never implemented. The Nine Years’ War broke out before the ornamentation on the rebuilt ship could be finished. In 1690, the ship sailed off to fight le perfide Britannique sans fancy paint or sculpture, and met its end in a fateful kiss with a fire ship at La Hogue in 1692.

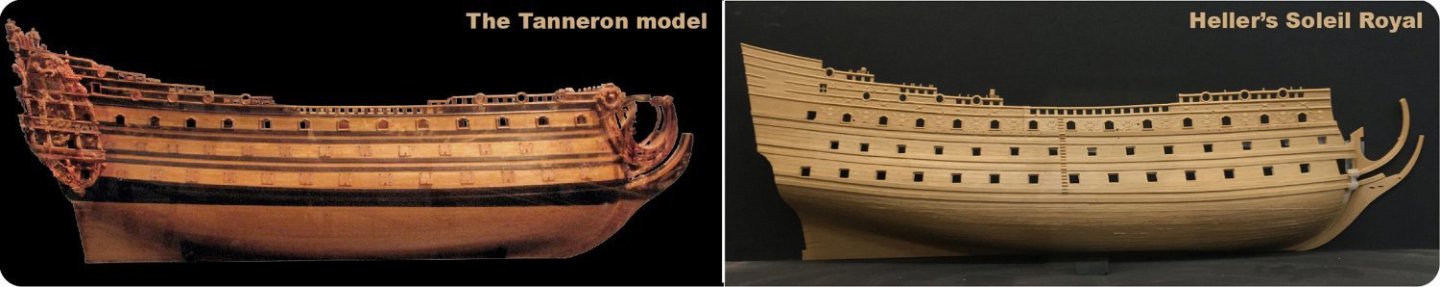

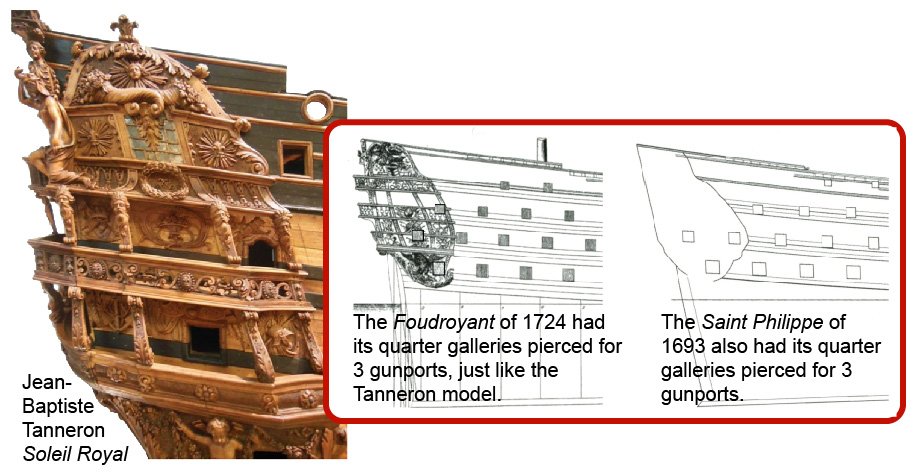

There are obvious differences between the Bérain drawings and the Tanneron-model-based Heller kit, notably, the design of the quarter galleries, the proportions of the stern, and the number of lights—windows—on each deck balcony. Tanneron had access to the Bérain drawings and it seems like he deliberately disregarded them. Even by the lax standards of historical representation in Tanneron’s time, there are just too many discrepancies. These issues vanish if we assume he was modeling a different ship.

Modifying the kit to resemble this version is a good project for those who like to scratch-build in styrene and have the time to invest. They have to widen the Heller hull and more or less replace the entire model fore, aft, and above the gundecks. Hubac’s Historian (Marc LaGuardia) has a wonderful build log on this site describing his adventures doing this. If this approach interests the reader, I strongly suggest continuing with that build log. I’m content to admire it from afar. This is too much work for me. My Soleil Royal build will be simpler.

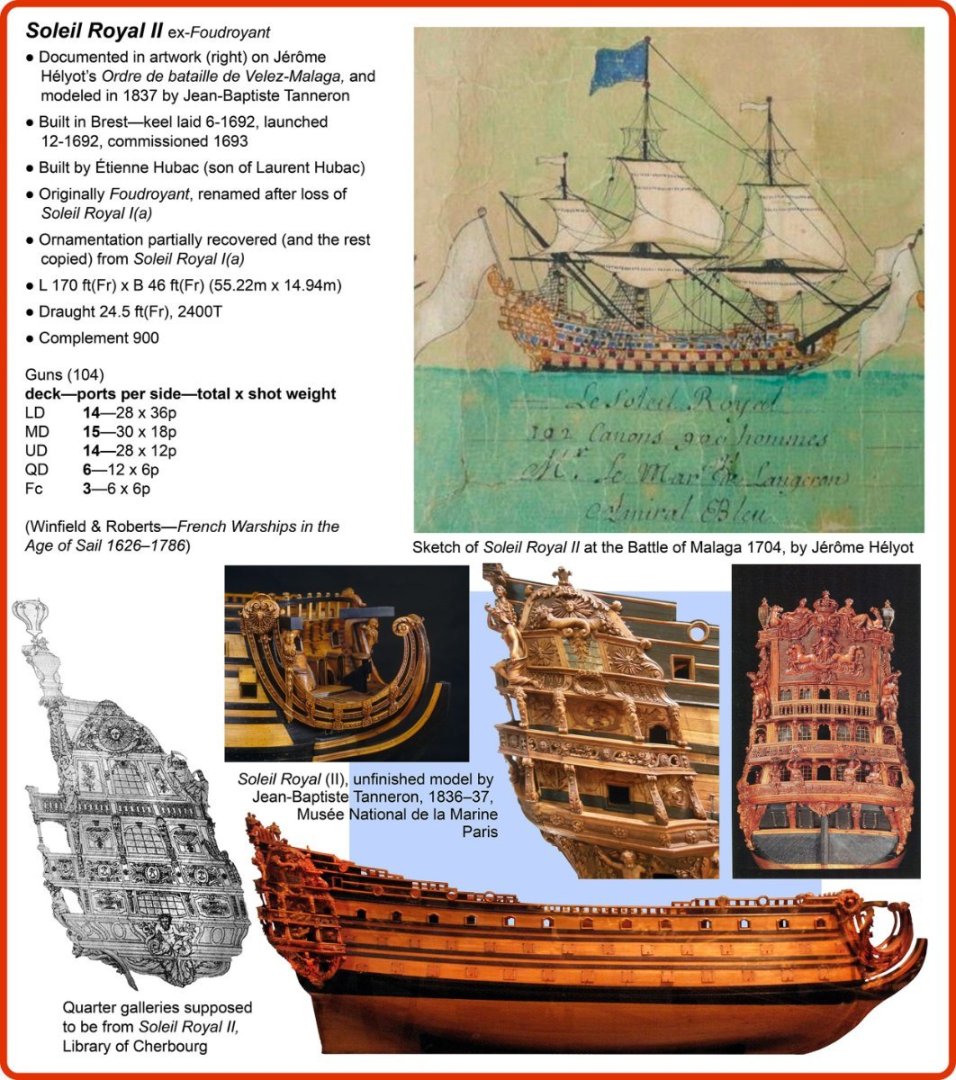

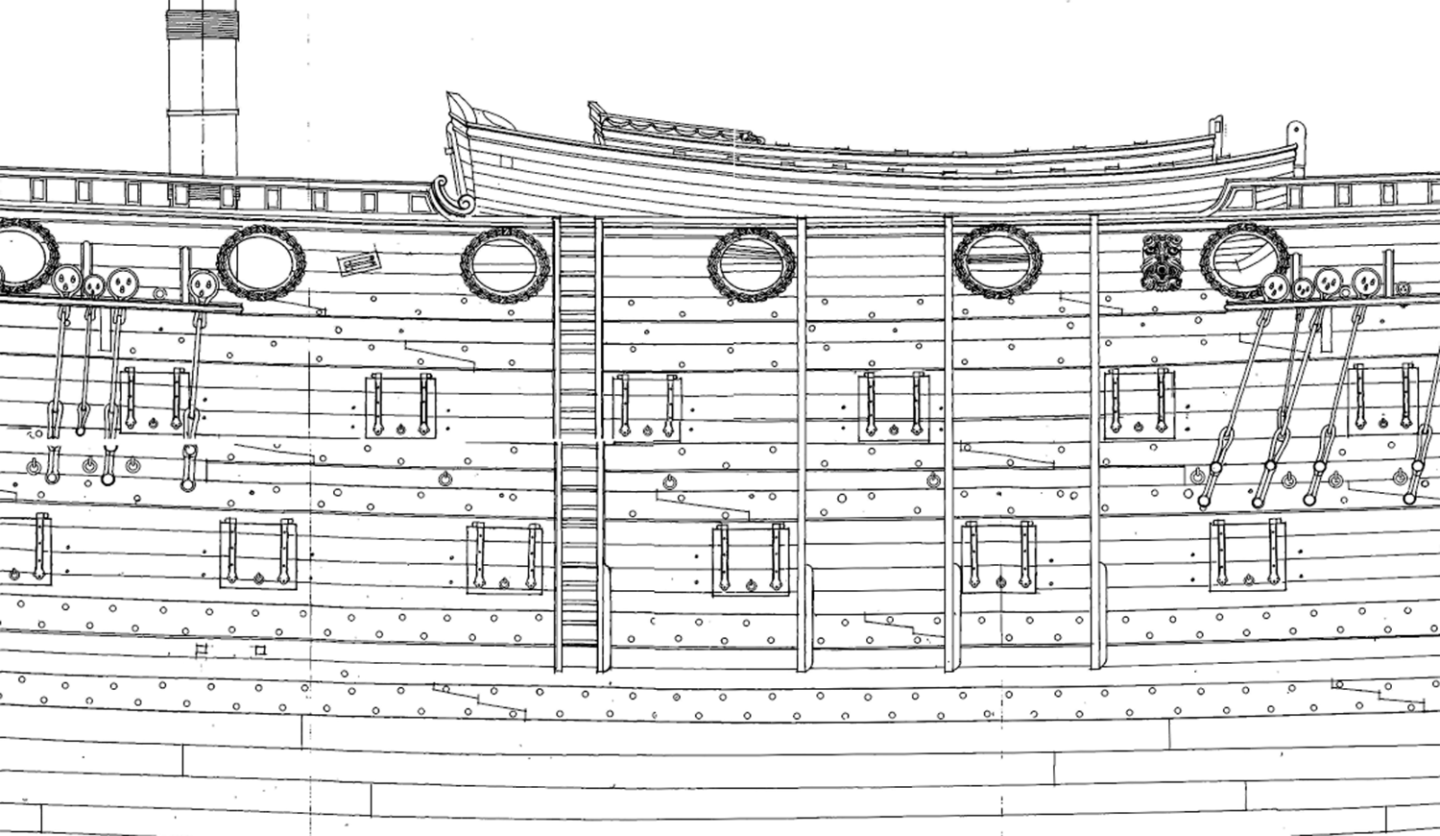

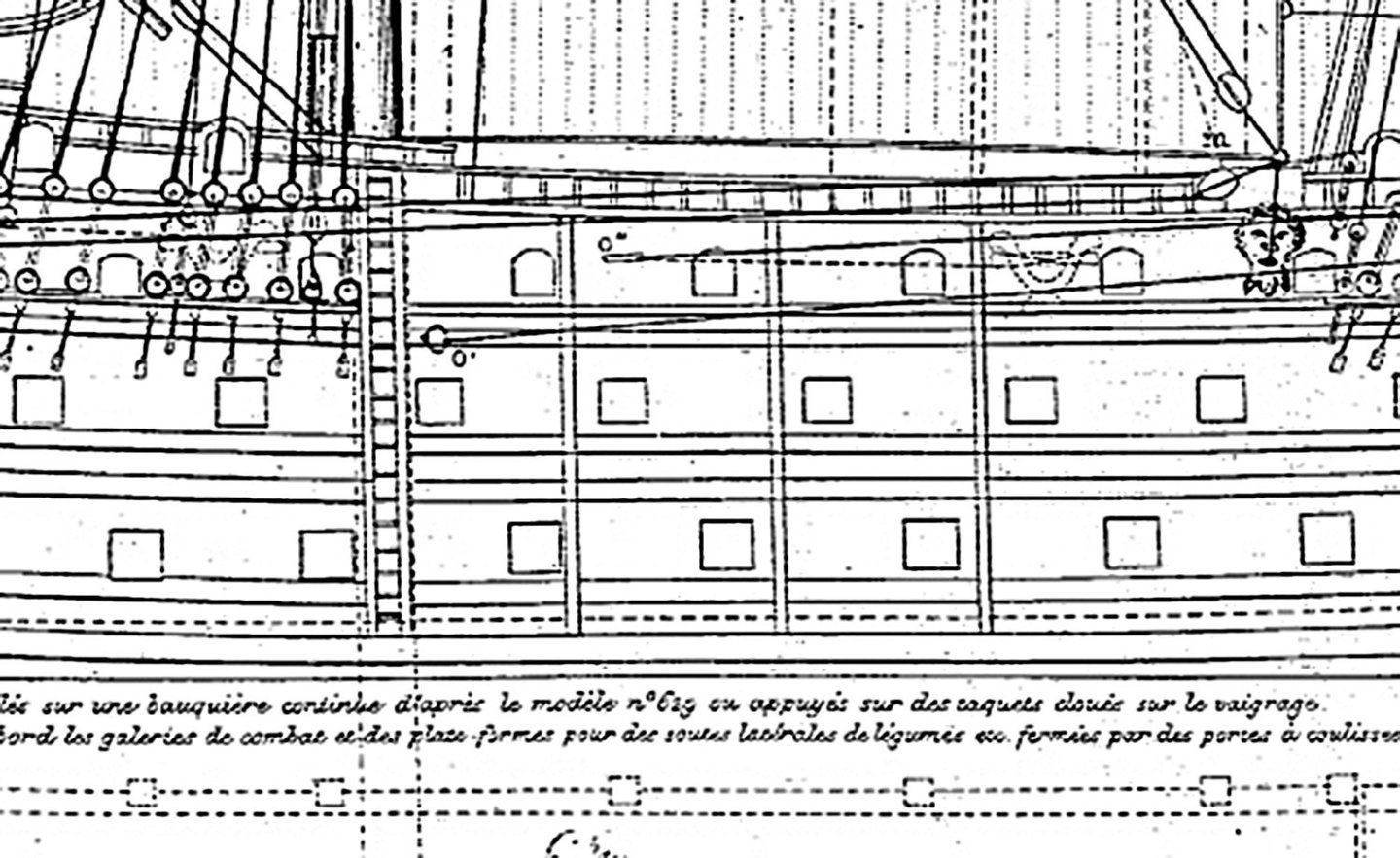

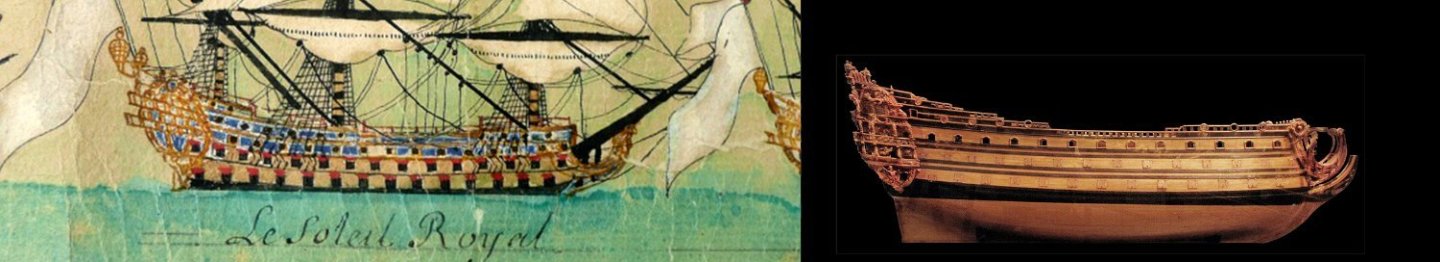

The simple little watercolor-and-gouache sketch above is the only artwork of a Soleil Royal in action made by an eyewitness, so we know this version of the ship was really painted blue. It appears on the five-meter scroll made of the order of battle for Velez-Malaga in 1704, painted by French officer Jérôme Hélyot, who participated in the engagement. This ship is likely the inspiration for the Tanneron model. One of the prominent researchers of the early French navy, Jean-Claude Lemineur, author of The Ships of the Sun King, identified the Tanneron model as being the Soleil Royal II. Skilled French modelmaker and researcher Michel Saunier thought the same thing. These are strong arguments from authority.

The model’s arrangement of gunports and the design of the quarter galleries are close to what we know about the Soleil Royal II. Tanneron built other model ships in the Musée from the same 1690s time period as Soleil Royal II. It’s possible his intent was to document the time of the “Second Marine,” when the French fleet was rebuilt following the disaster at La Hogue.

The Soleil Royal II was built in 1692 by Étienne Hubac. In a letter to Louis XIV, he pleaded to be allowed to rename his recently-completed ship from Foudroyant to Soleil Royal in honor of his dad’s ship lost at La Hogue. In the same letter, Hubac disclosed he still had all les gabarits (moulds, maquettes, and templates for the decorations) from the previous ship. The Soleil Royal I(a) had been stripped of many of its finished sculptures before the battle. All these were apparently available for reuse on the Soleil Royal II. New carvings based on the surviving les gabarits filled in the gaps.

I figured that it took the least amount of effort to turn the Heller model into a semi-respectable resemblance of the Soleil Royal II. That was going to be my goal.

And no, I wasn’t going to accept all the peculiarities built into the Tanneron model and copied by the kit. It’s clear that Tanneron wasn’t completely faithful to historical sources. I saw no reason to be completely faithful to him.

Besides, it’s fun to do your own thang, man.

Now that I had decided which ship to build, I could plan changes to the hull.

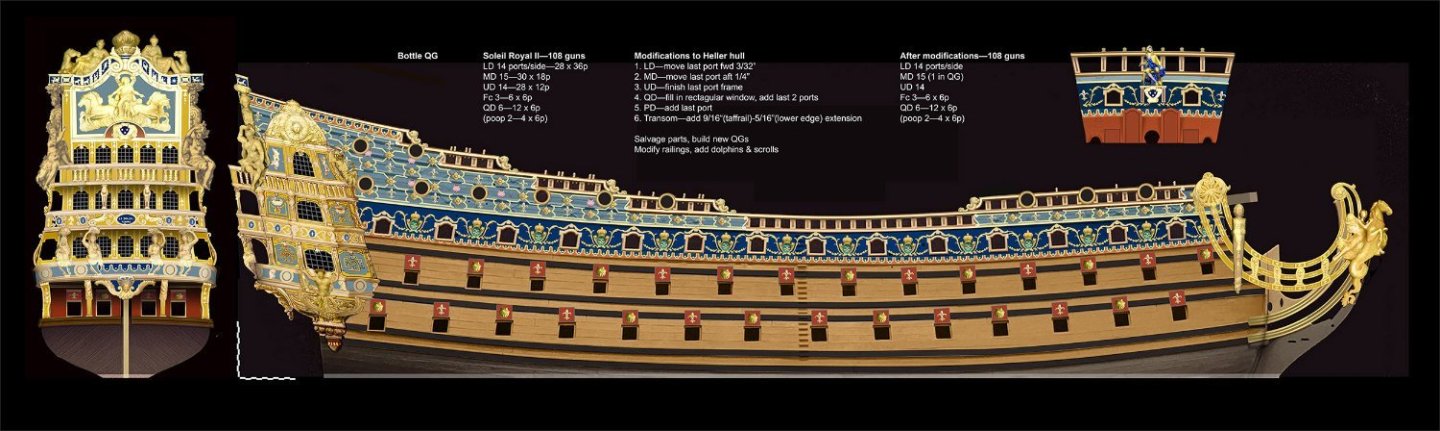

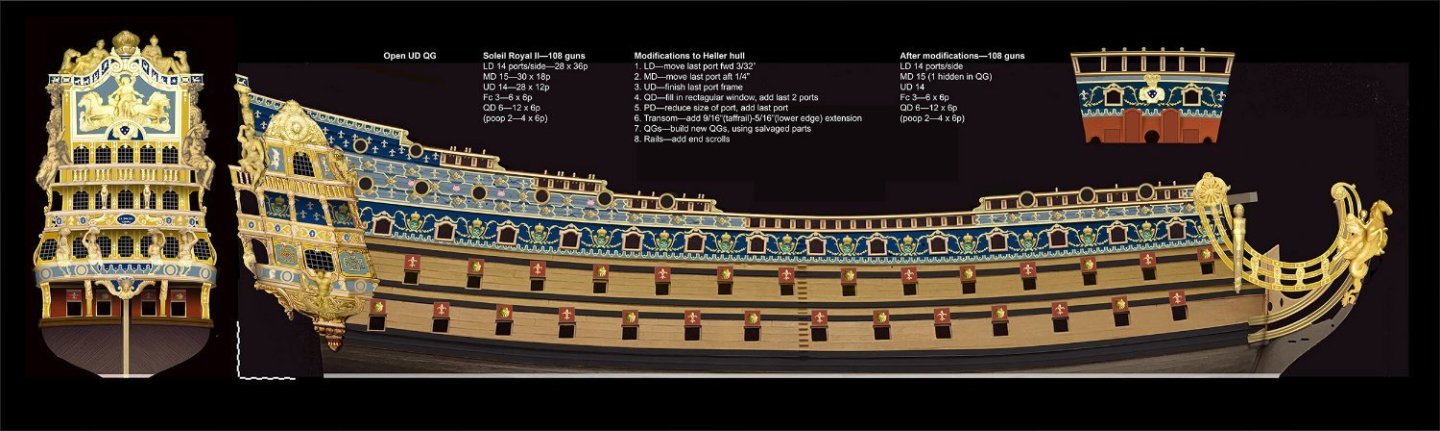

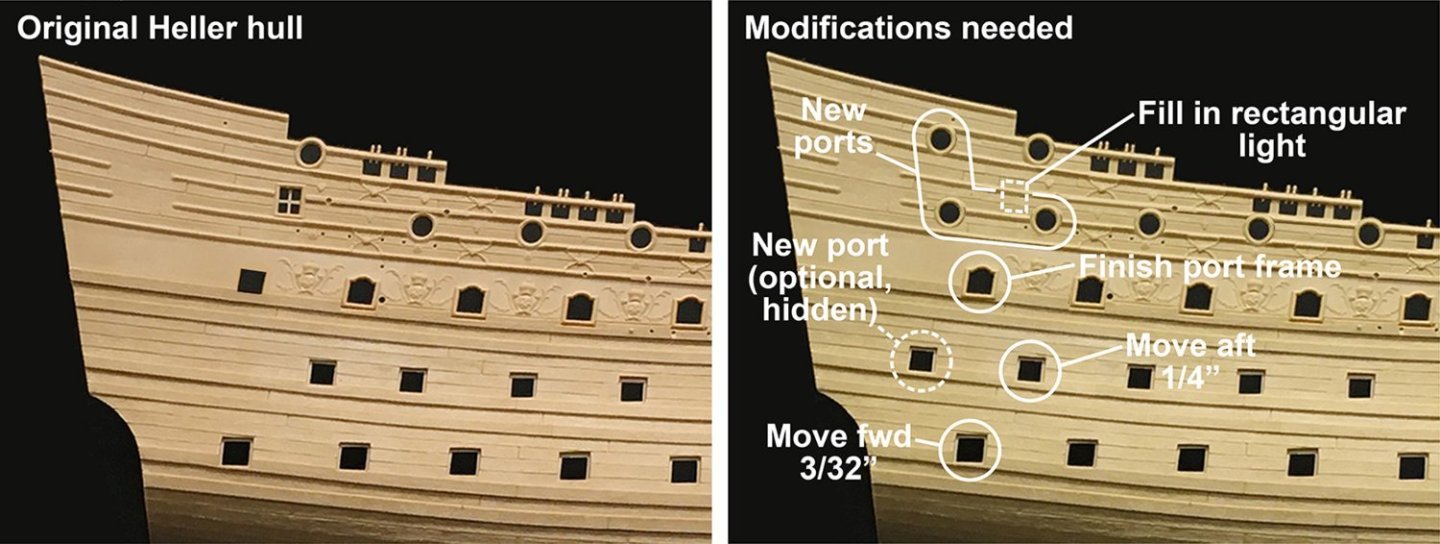

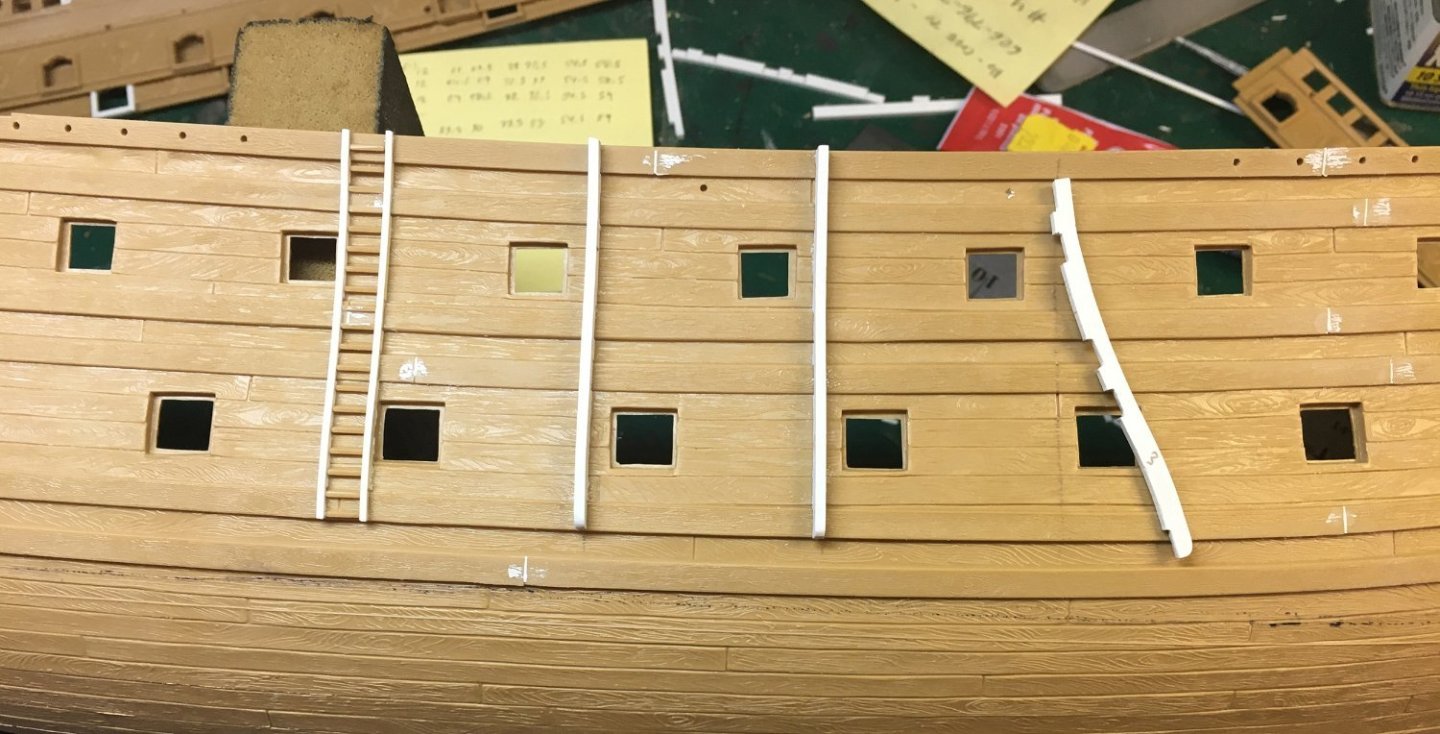

I chose Winfield & Roberts’ French Warships in the Age of Sail 1626–1786 to be my guide. It’s always fun to piggyback off other people’s meticulous research. In their description of the Soleil Royal II, they listed the armed gunports on each deck (104 total), and happily, the Hélyot sketch agreed with them. This meant the Heller hull needed a few ports added and a few ports moved.

Tanneron gave his model 102 armed gunports. This was because the ship was armed with 102 guns at the Battle of Velez-Malaga. Later research showed that the ship actually had emplacements for 104 guns (minus the fore and aft ports, and the four poop deck ports, which usually did not have guns mounted.)

There are 100 gunports on the Heller kit (again, not counting the fore and aft ports). The last pair of ports on the middle gundeck is supposedly hidden inside the kit’s enclosed quarter galleries, but they're visible on the Tanneron model, which has open galleries. So the middle gundeck is missing the last port on each side. The kit’s quarter deck is short two ports on each side, and the poop needs an additional one. Also, the spacing of the last pairs of ports on the middle and lower gundecks is uneven. No chase ports needed to be cut; a note in Winfield & Roberts said that the chase ports in Soleil Royal II were never pierced.

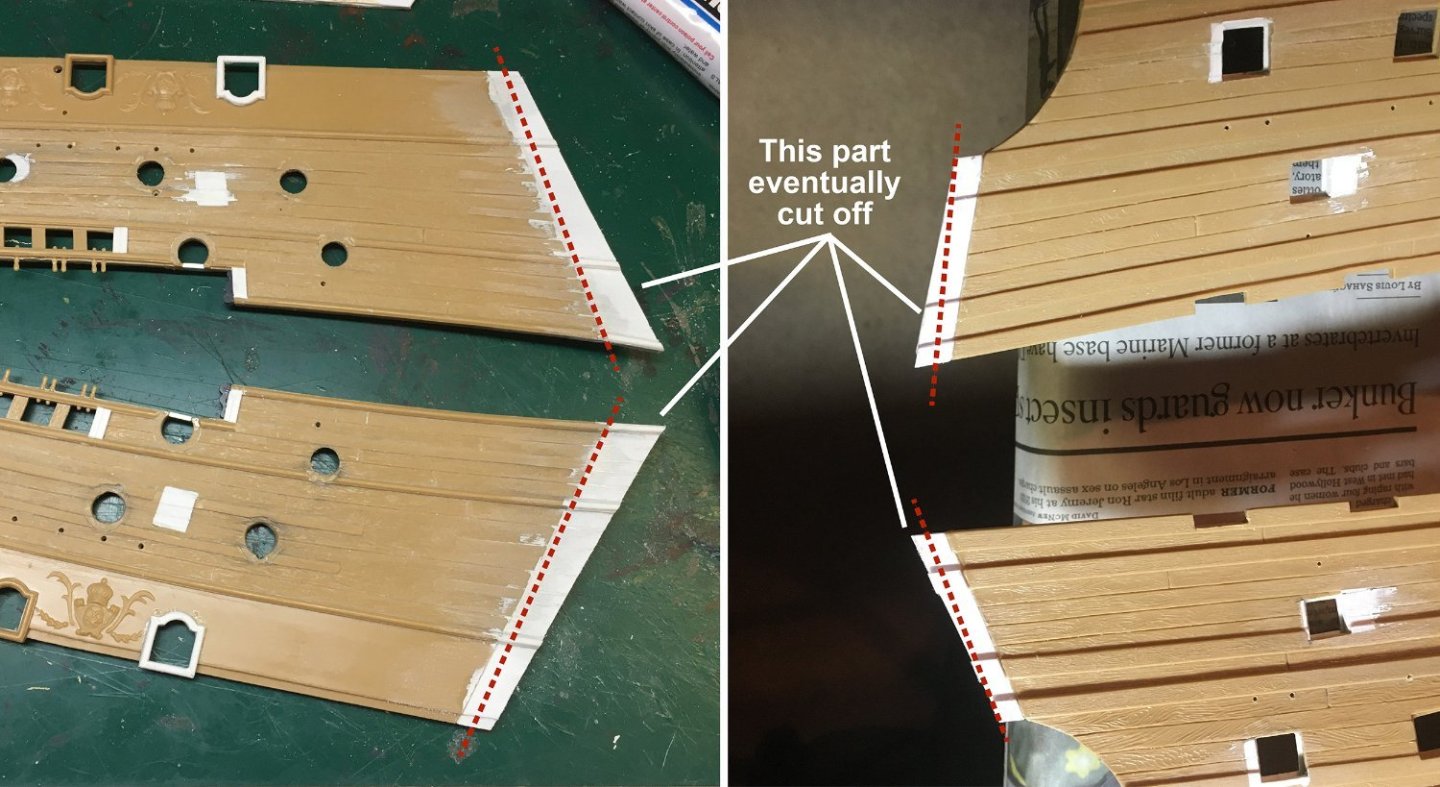

I decided that the last ports in the middle gundeck didn’t need to be cut because I was going to have them hidden behind the panels of the quarter galleries. I had made the decision to modify (and shrink) the kit’s quarter galleries. There are several good reasons for this, which will be covered in a later post. For now, the major consequence of that decision was that four of the gunports of the Heller kit formerly incorporated into the quarter galleries were now going to be exposed like the others.

In real life, the framing of the ship dictated regular spacing of the gunports. The Heller hull had to be modified to reflect that.I made a list of things to do for each hull half—

- Lower deck—move last gunport forward 3/32”

- Middle deck—move last gunport aft 1/4” (and optional—add last port)

- Upper deck—finish last port frame (formerly part of the kit’s quarter galleries)

- Quarter deck—fill in rectangular window, add last two ports (for a total of six QD ports on each side)

- Poop—add one more port

When complete, the modified hull sides would have 108 ports, armed and unarmed—just like the Hélyot sketch.

I Photoshopped the changes to be made:

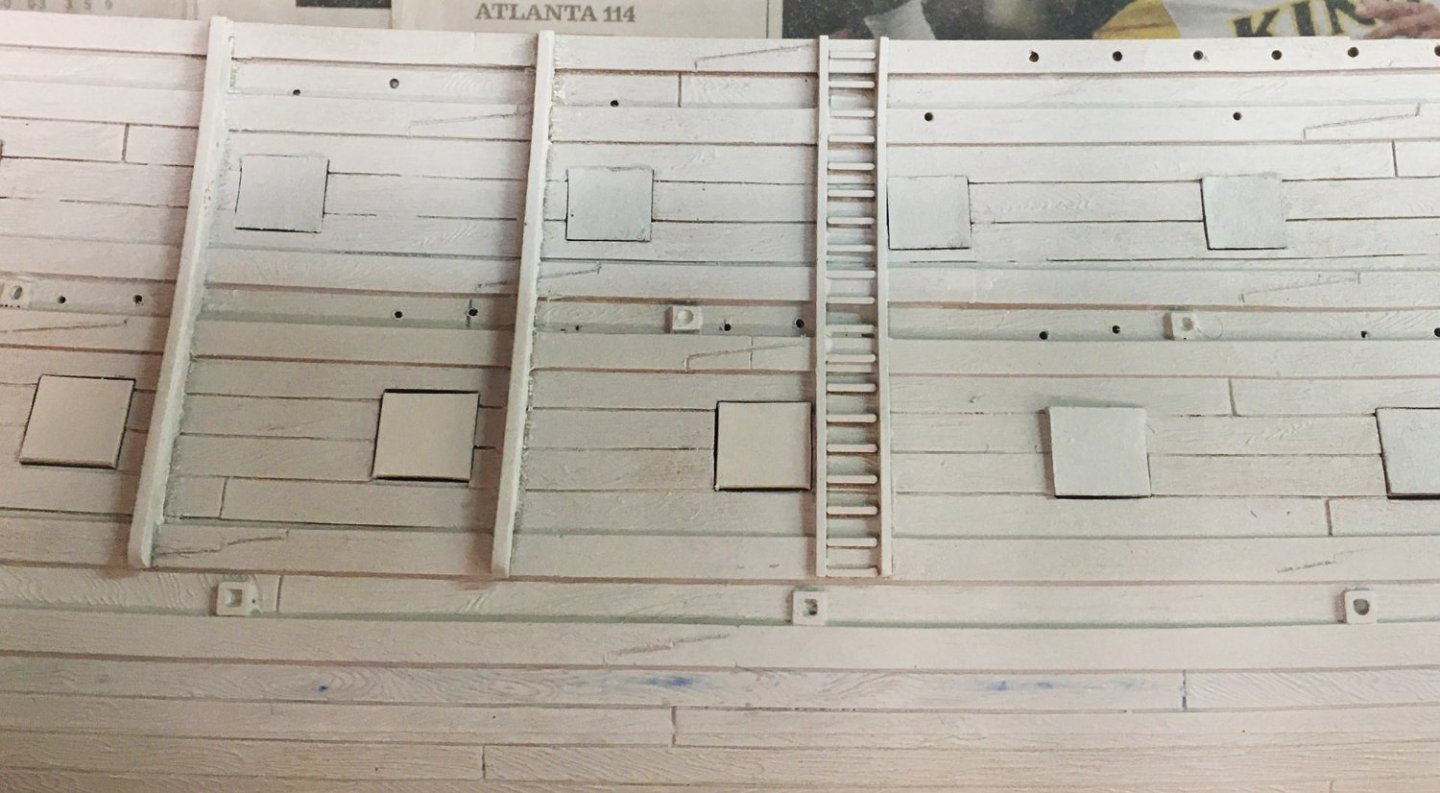

And went to work with X-acto blades and my variable-speed Dremel with a grinder attachment.

Sheets of Evergreen plastic in a variety of thicknesses provided the patches, and Tamiya white putty filled in the cracks and oopsies. The job was finished off with a variety of needle files and sanding sticks. New wood grain was carved in with the X-acto blade and the whole thing roughed up with a wire brush.

One of the good qualities of the Heller kit is that the quarter deck and forecastle are separate pieces. Easier to work on that way. A lot of the decorative strakes had to go so they wouldn’t interfere with the new décor. There is a lot of floral carving detail on both pieces. None of it is from the Tanneron model and it looks like it was halfway inspired by the Bérain drawings, but it is also really insignificant and looks like the Heller die-maker was having a rotten day after fighting with his wife. I opted to remove it all and substitute something of my own. I was also going to replace the plain round gunport frames with new decorated ones, so away they went too. Sanding sticks, Ho!

I drilled out the additional round gunports. The spacing of the last three on the quarterdeck was tightened up a bit for fit. With everything else to attract attention on the finished ship, I don’t think it will be noticed. The missing rectangular gunport frames on the aft upper deck were made from 2mm sheet styrene and 2mm 1/2-round Evergreen strips. I ordered new round gunport frames—little brass jewelry whatchamacallits from the craft website Etsy. In the photo, I tried on a few for size. They won’t be attached until a later step.

Last step for the gunports for now—I added some thickness to the hull visible through the gunports. Ships of the line back then were true castles of oak, with thick walls of framing and planks, not thin shells. I probably should have used 1/8” styrene strips, but I didn’t want to go back to the hobby store and I had a big surplus of 1/8” stripwood. Someone with better ship-modeling knowledge than me would use precise thicknesses and taper the thickness from lower deck to middle deck, but for me, the 1/8” (approximately a scale foot) helps the appearance just enough.

Now that I had all the gunports in order, I made a list of extra things to add to the hull—

- Bolts and trennals (NOT!)

- Wale scarfs

- Fenders and ladder rails

- Anchor linings

- Scuppers

- Stern plate extensions

My reference for these was Peter Goodwin’s Construction and Fitting of the English Man of War 1650–1850. I made a leap of faith in thinking that shipbuilding technology in the 1690s wasn’t all that different in la nation de boutiquiers across the Channel.

NUTS TO BOLTS—

I planned to add bolts. I even went online and bought a shi(p)load of 2” HO bolt-heads from Tichy Train Group. God, they were TINY!

A lot of ship modelers add bolt-heads to wales as a matter of course. They also indicate trennals (tree-nails) on planks. It looks cool, but it has always bothered me. Were bolts and trennals really all that visible on ships of that period? They show up in period artwork, but they aren’t that apparent on the HMS Victory or the USS Constitution. These are ships from a century later than the Soleil, I know, but still. The remains of the Vasa in Stockholm is covered with bolt-heads, but they’re all modern replacements to keep the rusty iron of the originals from further corroding and damaging the ship. There aren’t many other period ships to examine for guidance.

2,000+ exposed bolts on the surface of a wooden ship’s hull doesn’t make sense to me anyway. 2,000 bolt-holes exposed to the sea? Dry ship? No way!

So what does Goodwin say about trennals and bolts?

Trennals—“The advantage of wooden dowels was that when they got wet the wood expanded, thus tightening the fastening.” After boring the plank and frame underneath, “the trennel was then driven in, and made flush.” So, no surface indication for trennals.

Bolts—“It was considered good practice to bore out the timber on either side, to a depth and diameter of the head and the rove. Once the bolt was fastened the remaining space was filled with some form of caulking, and faired off with the faces of the timbers.” No surface indication of bolts, either. And I can’t imagine a premier rang French flagship being built without “good practice.”

That left the question of why all those bolt-heads show up in period drawings. In truth, I don’t know the answer, but in the end I opted to go with instinct and forego the bolts. My Soleil Royal would have smooth sides and wales, like the HMS Victory.

Whew. Too bad I bought all those bolt-heads. On the other hand, I don’t have to drill 2,000 holes in the wales. That’s a relief. I think my old Dremel would die screaming.

WALE BUTTS—

Say that three times without cracking up. One thing that I could fix easily was all the butt joints Heller’s die-makers put on the wales. Should be scarfs instead. I filled in the butt joints with Tamiya white putty and referenced one of J.C. Lemineur’s drawings of L'Ambitieux (cribbed from online) to place some scarfs.

J.C. Lemineur, L'Ambitieux

It took very little time to scribe in the new ones. Here’s how they looked a little further on, after some primer had been applied.

Have a good look. The scarfs will be invisible when the wales are painted dark brown.

FENDERS and ladder rails—

were added using Evergreen styrene strips. According to Goodwin, the dimensions were usually 14”–16” proud from the sides of the ship by 4”–5” wide, but those honestly looked too big and distracting. I cut them down to about a foot. Goodwin also says there were usually 4 or 5 fenders per side, but he’s probably referencing later English ships. I opted to copy a drawing of the 1693 Royal Louis and added three.

ANCHOR LININGS—

I got out the kit’s anchor castings, built one, and swung it from where I supposed the catheads would be to figure out where the anchor linings should go. Goodwin’s book also had diagrams. Built them from more Evergreen strips. The gap between the main wales was filled in from the anchor linings forward. My linings are probably too robust—but they’re going to have a lot of distracting detail close at hand, so I’m not inclined to perform a do-over.

SCUPPERS—

According to Goodwin, there were six to eight per deck per side. I settled for seven. Goodwin said they should be flush with the sides, but I like them standing out a bit, as J.C. Lemineur has drawn them in one of his detailed renderings of Le Saint Philippe. Cut from Evergreen square tubing.

STERN EXTENSION—

When I started, I had the idea of using most of the kit’s quarter galleries, just moving them aft about 1/2 inch to clear two of the gunports. In order to do this, I figured I needed to extend the stern 7/16” at the taffrail and slanting down to 3/16” at the lower edge of the stern plate. This was done with 2mm sheet styrene. That exaggerated the already-too-high taffrail even worse, so I redesigned the quarter galleries yet again (you’ll see them in a later post) and ended up chopping off most of the new stern extension. I left the 3/16” at the bottom edge, though.

Can we glue stuff yet? Not anywhere close.

I still have to think about what I'm going to paint this thing. Next week, we’ll see what goes into that decision and find out where some of the divergent information about the Soleil Royal’s paint and color—um, diverged.

Fluctuat nec mergitur. Happy modeling .

-

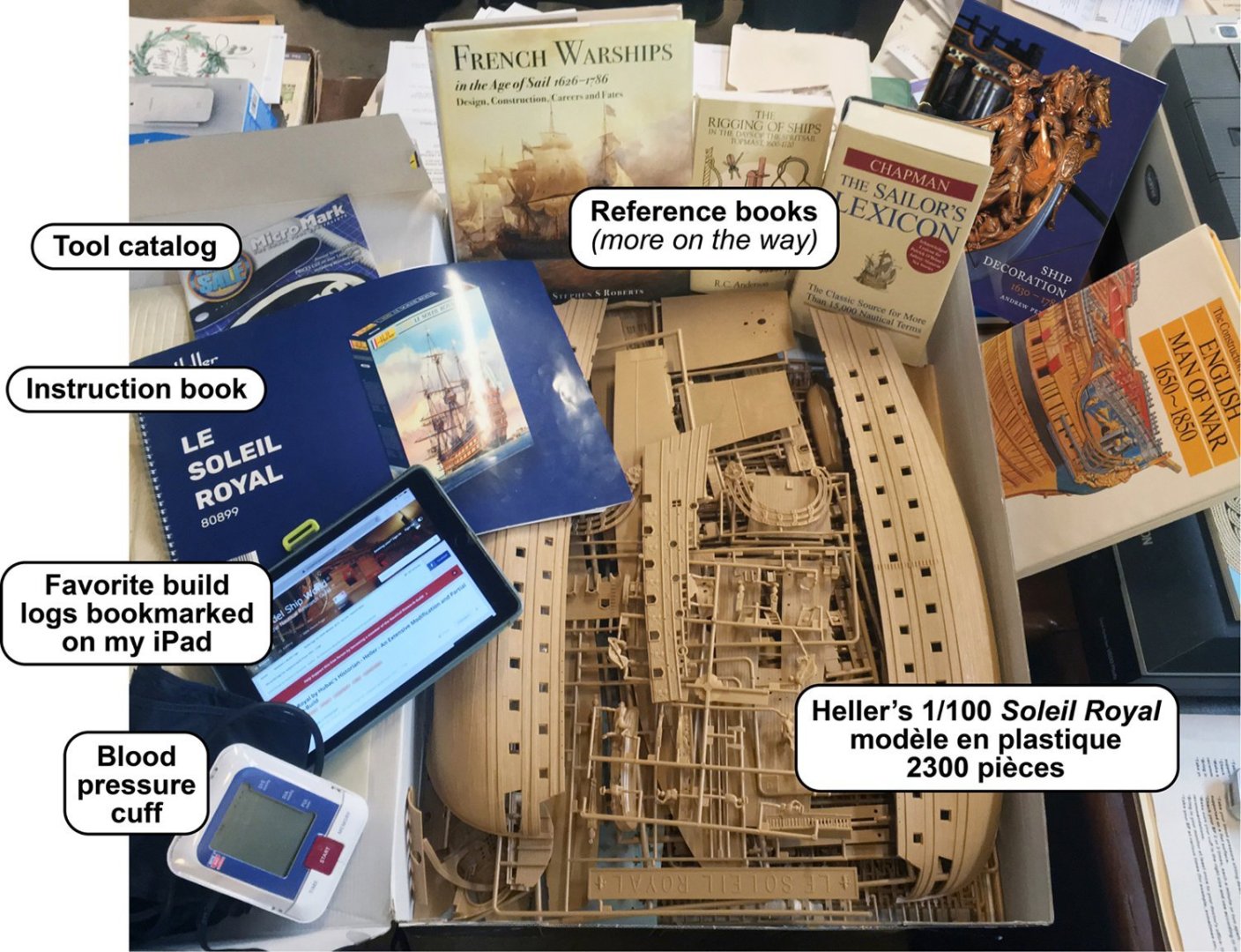

I guess we’ll find out if this forum has the patience for another Heller 1/100 Soleil Royal build log. This one will be focusing on changes, mods, upgrades, additions, styrene-bashing, and general mess-making in pursuit of something just a little different from the boxtop. Hello modelers—my name is John. I’m a lifelong plastic model kit enthusiast who never builds anything according to instructions. I first saw Heller’s 1/100 Soleil Royal when, as a commercial art student, I worked for a short time at Revell in Venice, CA, airbrushing backgrounds for box cover art. It was around 1978–79. One of the big shots had the unbuilt Heller kit opened on his desk. I was gobsmacked, and vowed to build the kit one day.

Unfortunately, display space at home was scarce, and I knew that the model wouldn’t survive the irregularities and frequent moves of a twentysomething punk’s lifestyle. I kept putting off getting the kit until things got settled a bit.

Now, 45 years later, I figure it’s now or never.

In the half-century the kit’s been in production, it’s been controversial, an inspiration for a lot of palaver and condemnation. For a supposed “scale” model, there’s a lot that’s questionable about it, and if you aren’t familiar with the shortcomings, it’s because you haven’t read the other Soleil Royal build logs yet. However, the more I read and the more knowledge I picked up, the better this kit looked. I decided I could build an attractive representation of one of Louis XIV’s premier rang (first rate) ships-of-the-line from this kit. It would be impressive, if not wholly accurate. Many features would be exaggerated, but I’ve never had a problem with a certain degree of caricature modeling in small scales. I’m not a fine-scale modeler. I’m familiar with all the compromises accepted in other categories of modeling. Why not ships?

Besides, I had decided my Soleil Royal would look different from the usual. I love to add stuff and change the detailing on kits. I haven’t found a kit yet I couldn’t customize.

Here’s what I started with in November, 2022.

The kit is beautiful, well-detailed and nearly free of flash and mold lines. State of the art when it was released in 1974. Parts fit well and the few large pieces that were slightly warped (no kit is perfect) were fixable with a little work. The box was delivered in November. I stared at the pieces for a while and then started reading reference books, websites, and build logs. I learned a lot from other Soleil Royal build logs on this forum and others. I am continually delighted, amazed, and entertained by the work of Marc LaGuardia (Hubac’s Historian) and his correspondents. The work I’ll be showing off here is the direct result of the knowledge they have generously shared. I’m a metaphorical fig newton, standing on the shoulders of giants, or however it goes.

I didn’t clip a sprue or squeeze a glue tube until February, but here’s what my project looked like in August, after six months work—finally ready for masts and rigging. (More beauty shots at the end of the post.)

I propose to show how I got to this point in weekly posts that will also contain some hopefully-interesting-slash-useful history and background of the ship. There’s a lot of stray information (and disinformation) about this ship floating around, and I’m going to try and assemble all the important bits in one place. The prototype was a remarkable work of Baroque art as well as a weapon of war. A floating castle of death-dealing artillery decorated by the same artistes who built and filigreed the palace of Versailles. The dichotomy is delicious.

SO WHAT IS BEHIND HELLER’S KIT?

The model is patterned after an 1837 wooden ship model in Paris’s Musée National de la Marine, made by the skilled ship modelmaker Jean-Baptiste Tanneron. You’ll be hearing about the Tanneron model a lot. Copying it was a logical thing for the Heller mold-crafters to do, since it was the only well-known detailed representation of the Soleil Royal from historic times. One of the first things I did was tape together half the hull and propped it up to make a comparison photo.

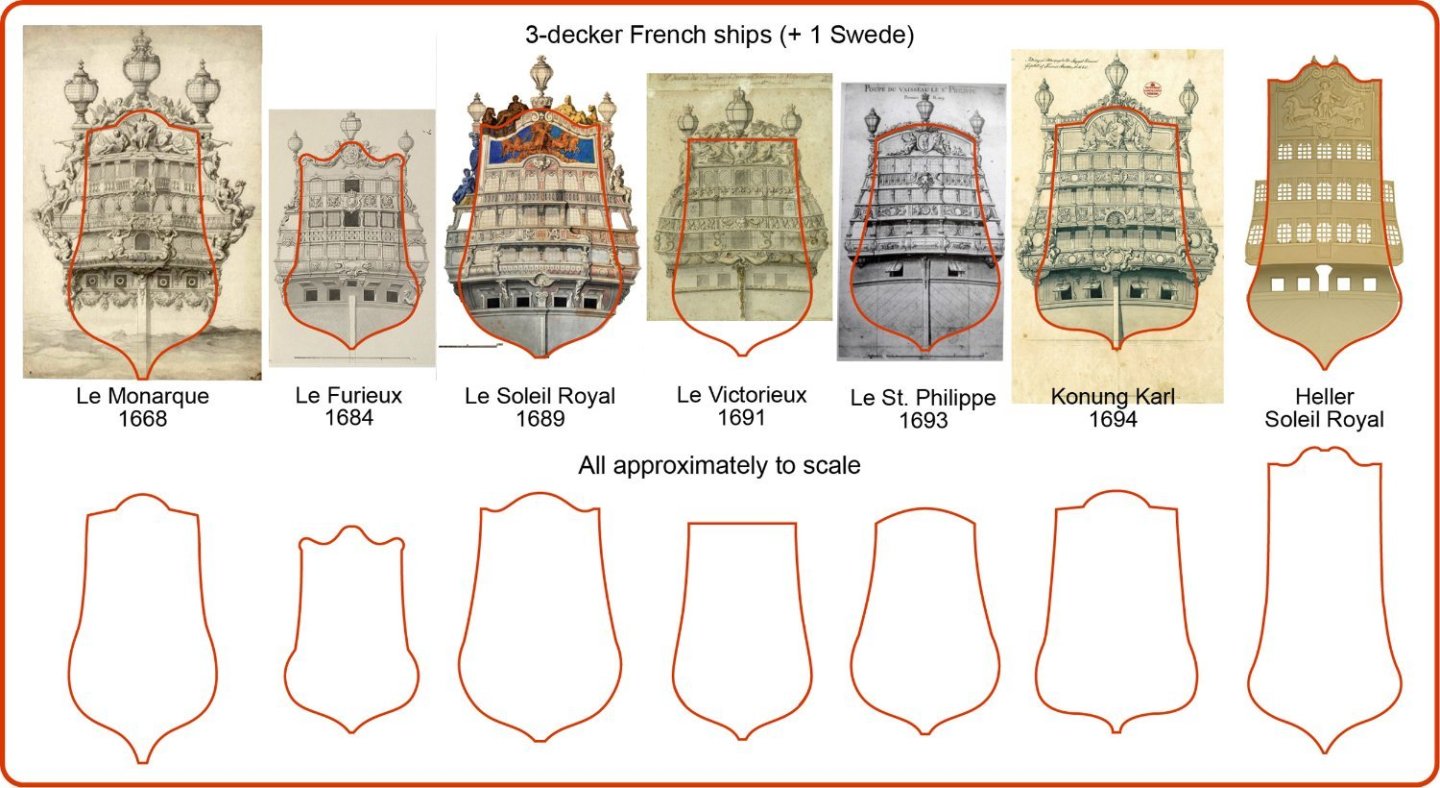

But copying the Tanneron model brought Heller problems. The first is the true identity of the ship. There were three ships built in Louis XIV’s time named Soleil Royal. The first was built in 1668–70. Hereafter, I’ll call that one Soleil Royal I. The second was a from-the-keel-up rebuild of the first ship in 1688–90. That’s Soleil Royal I(a). The third was a new ship built in 1692–93, Soleil Royal II. All three were 100+-gun premier rang three-decker royal flagships, extravagantly ornamented to reflect the glory of Louis XIV, le Roi Soleil, the Sun King. The Musée de la Marine is noncommittal about which ship Tanneron’s model represents.

According to Heller’s literature, the kit represents the first two ships (considered as one), which met its fate in an encounter with an English fire ship in 1692. I’ve come to believe this is the wrong ship. Heller is partially to blame for the confusion, but in their defense, the Heller die-makers working in the early 1970s didn’t have the instant access to books and internet information we enjoy today, and the museum authorities they consulted were apparently not very helpful.

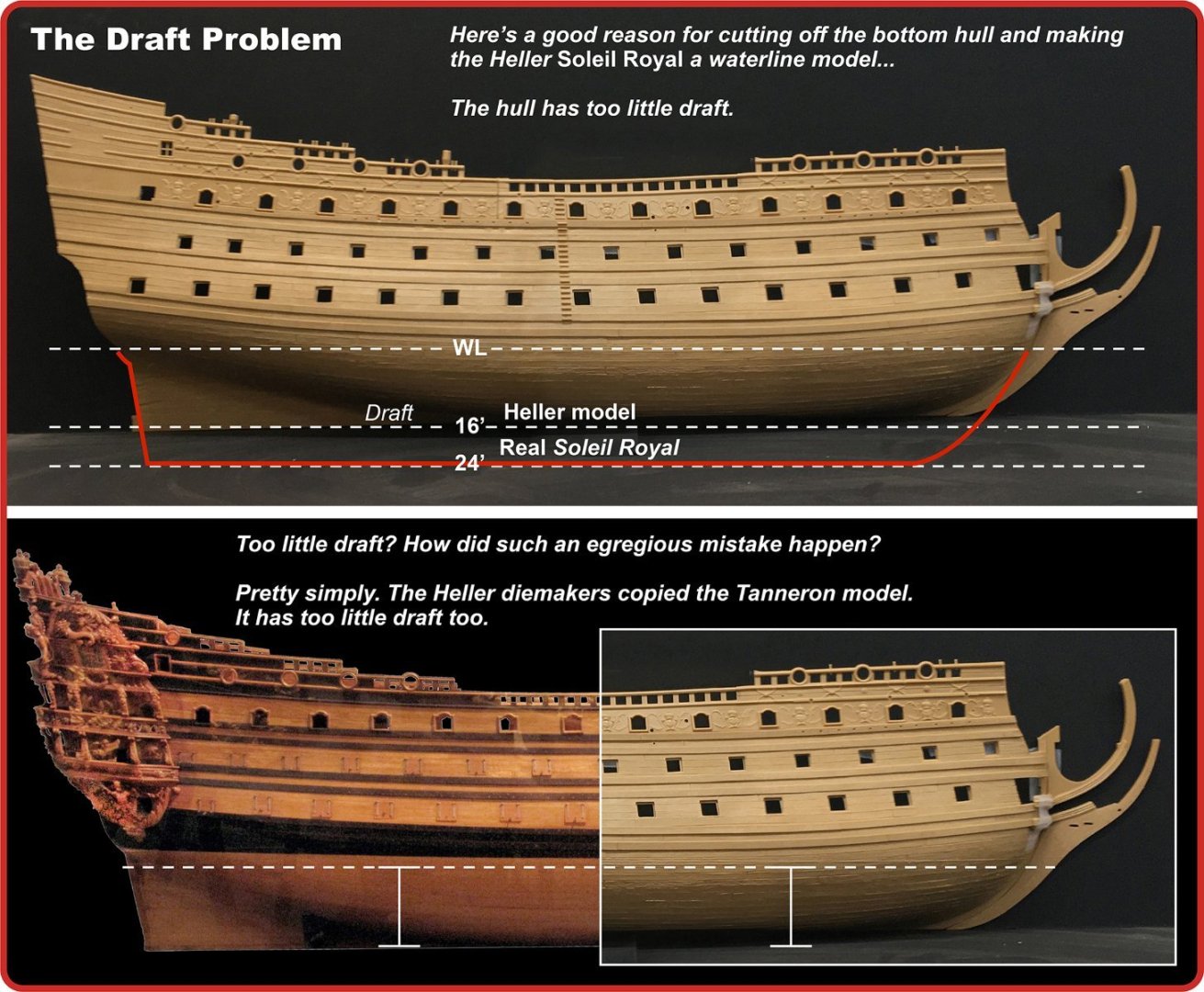

The second major problem with the model is that the hull has too shallow a draft. According to surviving records, the 2400-ton 170-foot ship should have a draft of 24 feet. The Tanneron and Heller models—nope!

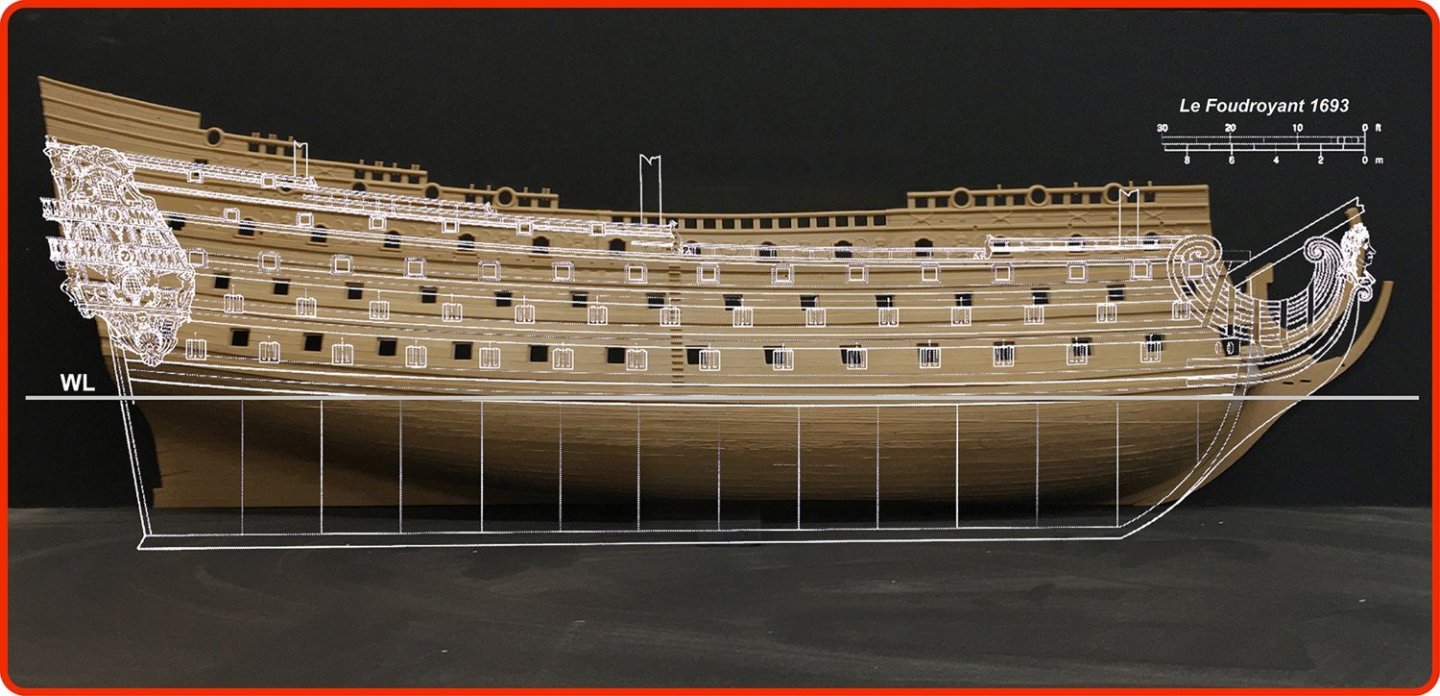

Third, to compound the problem, the above-the-waterline dimensions are exaggerated. The gundecks have lots of headroom—eight feet, compared to the six feet on actual 3-decker warships. There would be very few cases of concussion by clumsy gunners going bonk on overhead beams if they sailed on a ship with Tanneron’s dimensions. Here’s the Heller model with a scale line drawing of another ship from the same time period, the Foudroyant:

Aaaand… let’s quit there. Let’s not even discuss the height and width of the stern.

What was Jean-Baptiste Tanneron thinking? Unfortunately, we can’t ask without a ouija board. It should be noted, however, that before the invention of photography, representations of historical objects in artwork (or sculpture, or modelmaking) weren’t anywhere near modern standards of accuracy. Living in an information-and-photography-saturated society, our attitudes about fidelity to prototypes have evolved a lot.

For myself—I think the impression of a tall, castle-like warship is enhanced by Tanneron’s exaggeration of the proportions. And this is no modern interpretation. Have a look at the only eyewitness sketch of one of the Soleil Royals in action. Look how high the exaggerated sheer is in the drawing and compare that to the Tanneron model. Oh yeah! Both artists made this ship big, and high, and a true seagoing fortress. That should be the biggest takeaway from seeing artwork or a model of this leviathan. I think the Tanneron model (and the Heller kit) gets the point across nicely.

So in the end, if you choose to build the Heller Soleil Royal, you’re really building a model of a 19th-century model, and it’s a caricature model anyway. For complete intellectual honesty, you should get out your wood-colored paints and wood-grain-duplicating techniques and make the model look as if it were carved from fine hardwoods; a model of Tanneron’s model. That would be a commonsensical approach.

Fortunately for me, I have no common sense when it comes to models. I want have fun detailing, painting, and rigging a plastic model ship. Here are more photos of my progress up to August, 2023.

Not much gold leaf on my version of the ship. After some reading, I don’t believe there was a great deal of gilding on the prototype. Figuring out what to paint the ship, based on surviving descriptions, old artwork, historical painting practices, and antique models, was a major part of the research. Paint choices and decorations will be discussed in later posts.

Deck furniture got changed. Many trips to Ikea.

Much time was pi—ah, productively spent—rigging tiny guns and rebuilding tiny boats.

Guns were either replaced or rearranged and drilled out to the right calibre. Colorful gunport lids will be installed as soon as I finish the channels and shrouds. 104 guns were mounted, same as the ship had in the period I’m trying to model (very early 1700s). The waterline got raised to squeeze in a few more feet of draft. Quarter galleries got entirely rebuilt to better resemble a surviving historical drawing.

I believe that the enclosed “bottle” quarter galleries on late 17th-century French warships had removable panels—whether for weather or for war. I left the upper gundeck balcony open to demonstrate this.

Most of the ship’s gilding is up high—out of the way of waves and wear.

Wasn’t happy with the too-big kit-supplied figures, plus, I needed a few new ones to match the drawing of the quarter galleries I was referencing, so I sourced new figures from the Shapeways 3D-print marketplace. Figuring out all the ship’s iconography was a deep research rabbit-hole, but a rewarding one. For the curious, the figures on the forward edges of the quarter galleries are Kronos, “father time,” (starboard), and his consort Rhea, mother of the Olympian gods (port). The other two figures are replacements for the kit’s too-large allegorical figures of America (port, with feathers) and Africa (starboard, with elephant-head headdress). The figures were “dressed” with additional sheet styrene.

Next week we’ll get the project going by seeing what mods and additions were made to the hull, plus background on the three Soleil Royals and the whys behind which one I’m modeling. I invite discussion in the meantime. Happy modeling 'till then!

-

I feel like framing that side view. You'd better think about getting some good photography and making prints when you're done. We can hang them over our workbenches to remind us what all is possible building in styrene.

- Hubac's Historian and mtaylor

-

1

1

-

1

1

-

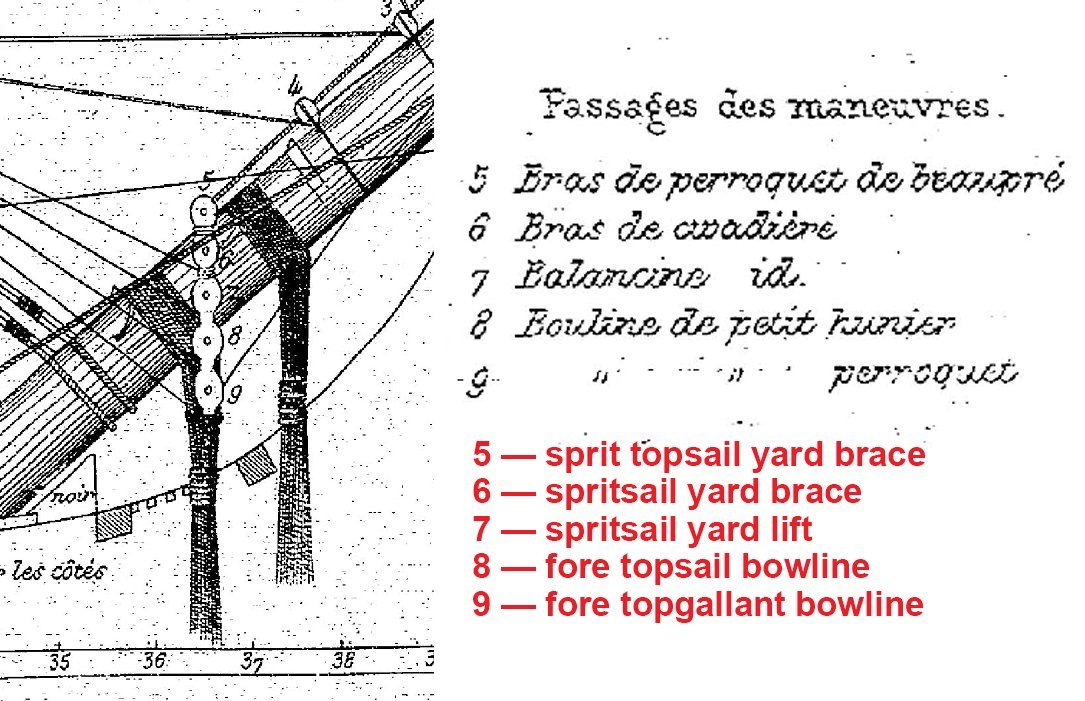

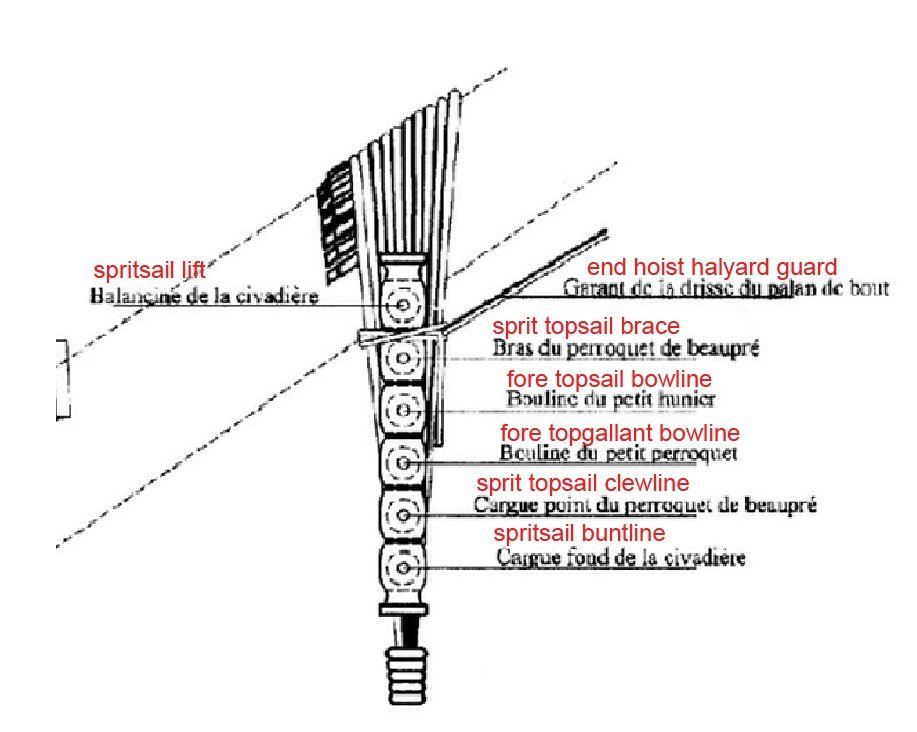

Bill, these are called rack blocks in Karl Marquardt's book on model ship rigging. I can't tell yet which lines are which on the Heller kit, but here are two prototype diagrams showing the lines that ran through. The first is from the 1690's Royal Louis model described by Admiral Paris. The second is from JC Lemineur's Le Francois plans.

John O

-

No doubts on climate change. Just regrets that the fire/smoke thing is now happening to you too.

And most of us in California are thankful that we won't have to go through it again this year.John O

-

In the 1960s and 70s, a gentleman named Alan Armitage wrote a bunch of magazine articles popularizing the use of styrene in model building. Alan was a superb railroad artist, plan draftsman, and an amazingly skilled modeler who made the masters for a lot of the favorite styrene railroad model kits that are still around today. People called him (in good 60s fashion) the "guru of styrene." I—and a lot of other modelers—learned to scratchbuild in styrene from his articles. I haven't thought about him much in the last thirty years until your work brought him back to mind.

It's really enjoyable to see such artistic model-making being created, one step at a time.- FriedClams, mtaylor, Hubac's Historian and 1 other

-

3

3

-

1

1

-

Marc, any reply to an offhand comment like you gifted me with deserves a detailed response of its own.

Although I never meant to go back to it, I've attached a new version of the sketch that incorporates a lot of your suggestions—higher taffrail, upper balcony balustrade and figures in better proportion, windows and decks lining up better, etc. I left the lower and middle stern lights alone, since the whole point to the exercise was to see how well SR's features would graft onto a drawing of a real Hubac hull. I can very easily see that a seven-light solution would be practical, though, and Tony Devroude's DR framing corresponds nicely with similar diagrams in Peter Goodwin's book.Not to be contrary, but the field of fleurs on the upper bulwarks was used on both Hubac ships that I have VDV drawings of (La Reine and Terrible). They also show up, as you pointed out, on Le Monarque and DR. Looks like it was a First Marine thing. So unless somebody can provide an authoritative description of the first SR's bulwarks, I'll stick with the fleurs. It's the lys amount of effort. Same goes for the vestigial QD upper balcony tier. No tiers shed.

Besides, if I work on this Photoshop thingie any more, it'll take time away from my own Heller SR build.There were some other things in your reply that spark conversation. I—uh,—swiped the 1853 D-M-J Henry description of the SR the first time you posted it. It looks like it was written by someone who saw this version of the stern drawing:

As opposed to the version we all know and love, and everybody wants to attribute to Bérain.The mention of the ostrich feathers is a dead giveaway. Has anybody come to any conclusions about who did the original artwork and which version came first? The figure of Africa in the Bérain drawing has the same elephant-head headgear that's on Le Brun's Africa at Versailles. This might be a telltale as to who actually designed the SR figures.

It's weird that D-M-J Henry didn't mention that the figures represented continents, not just "East" and "West." Attributing the designs of the figures to "the pencil of Puget" seems to me a misplaced leap of faith, considering that Le Brun had already designed all the allegorical statuary with the same subjects and attributes for the Versailles gardens. Makes me doubt that Henry had any more insight into the ship than researchers have now.

You mentioned all the gold leaf at Versailles and the likelihood the first version of the ship was adorned similarly. I recall that in one of your posts you discussed some period document that gave a budget for gold leaf for one of the warships. I can't find that post, but I remember that the amount was scarcely enough to do much more than gild the figurehead. I've been thinking about how to limit the amount of gold leaf on my own Second Marine SR build. One thought was to use most of the gilt on the stern Apollo frieze and the upper reaches of the quarter galleries—keep all the major areas of gold leaf high up on the structure surrounded by blue, just like at Versailles.

Under this plan, I'd paint the major figures in shaded faux gold (original formula was yellow ochre with lead-tin or Naples yellow highlights, and darker yellow—red ochre mixed in—for shadows. I painted the SR figurehead this way as an experiment. (I can still repaint it metallic gold if I want to.) There would still be the Bourbon crest and crown on the forecastle surrounded by gilded ornament, so there would be some gilding forward. Any thoughts on how much gold leaf seems appropriate for the Second Marine period?

Thanks again for the information and all the inspiration. This has been a sweet deal— I post an odd little Photoshop and get a college-level education in return. Looking forward to your next post. Building and painting 104 guns in the meantime.

John O

- GrandpaPhil, yancovitch, druxey and 5 others

-

5

5

-

3

3

-

Many thanks, Marc, for the treasure trove of drawings you posted. Your log continues to be a delight.

Back in January, planning my own Heller SR build, I grew frustrated at not having a reliable period rendering of the original 1669 ship, so I took Van de Velde's drawing of La Reine and "edited" it, figuring that the two back-to-back 1669 Laurent Hubac ships wouldn't have been that much different in looks (La Reine was about 10 ft. shorter, but had the same gun layout). I thought that if I could see a decent representation of the original ship, it might spark some inspiration. Long story short—it didn't. I opted for a simpler SR build (now in progress).

Hope you truly enjoyed France.John O

-

Thank you much for your reply, Marc. To briefly answer your question—Le Fleuron attracted my attention because of the nice Bérain drawing I found and also because it was one of the blue-painted ships on Jérôme Hélyot's order of battle scroll for the 1704 Battle of Velez-Malaga, which might make a good topic of discussion one day. I'm waiting to see if my last flurry of emails to France can find me any better pictures of the scroll than the ones I can swipe off the internet.

As for Le Fleuron becoming a scratch-project, I feel like I'll be fortunate if I can get through the Heller kit successfully. My own build is very much in the just-out-of-the-box phase, moving around gunports and scrubbing unnecessary detail off the quarterdeck and forecastle pieces, etc. I have modest goals, most of them based on things I've read in your log. I'm leaning toward making it the 1693 ship, because it looks easier to account for the gunports, because I think that's what Tanneron's model was based on (his other models in the Musée are Second Marine ships), and because it seems to be the only version of the ship reliably documented by an eyewitness with period colors, thanks again to Hélyot's Malaga scroll.Thanks once more,

John O

-

A huge amount of appreciation goes to Marc's log and his knowledgeable commenters. I've learned so much in the last few months from going back and reading from the beginning.

It might be that it wasn't just the figure carvings that were removed in preparation for war. I have a strong suspicion that the panels of the "bottle" quarter galleries may have been removable, too. There are several surviving line drawings and illustrations that show that some galleries on some ships were pierced with gunports. I have a feeling that the glass lights in the galleries wouldn't have gotten along well with cannon fire. All that flying glass must have made using the officer's heads exciting during battle. In all seriousness, maybe this is why Tanneron chose to "open up" the galleries on his model instead of making them the typical closed "bottle" galleries seen in the drawings of the Second Marine ships.

Is there any documentation that would confirm/deny my suspicion?

Everything best,John O

_3D_104_PUGET_VDV.thumb.jpg.f908fdfcbd2cb95ca5024255fdc70fa9.jpg)

Soleil Royal 1693 by John Ott - Heller - 1:100 - PLASTIC

in - Kit build logs for subjects built from 1501 - 1750

Posted

Hi Ian—thanks for the encouraging comments. I ended up adjusting the waterline three times to increase the draft. I found artwork that showed ships with a wet main wale and also knew that back then, in the days before slide rules, nobody could really figure a ship's displacement until it was launched and loaded. So, as long as it wasn't Vasa, no big deal.

The wet gammoning was a by-blow, but again—it didn't seem to bother J.C. Lemineur in his Saint Philippe plans. So I left it alone. At least I gave it a coat of white stuff.

And yeah—I changed the "angle of attack" because it leveled out the gun decks and just looked better to my eye. I like the aggressive look of a down-at-the-bows Baroque warship. I'll let others decide if it was a successful decision.