-

Posts

6,652 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by wefalck

-

At this scale buckets should be easy to make from thin paper or sheet-metal. They were either zinc-coated sheet-metal or emaille. Just look up photographs of the real thing and get inspired. The typical brushes as used on boats could be made in a similar way with thread as the pommels on childrens' knitted ski-caps - talk to a female family member, they probably will know, or have again a look on the Internet. This thing should be fitted to a wooden broom-handle then.

-

I am teaching a course of which one element is the interaction between science and society. One thing I tell my students is that it is sometimes (more) interesting to look at what is not subject to research and why. There is the myth of 'independent' science and research. In reality, much of the science is driven by what politics think is 'relevant' and, hence, makes research grant money available. One of those effects could be that pre-Hispanic culture is favoured over the 'colonial' culture. Similarly, there is a lot of money for research on societal/social issues, but little on the material culture of the respective societies. This overlooks the fact that these are usually closely interwoven. For these reasons, research into boats as such in many parts of Europe finds little interest on the side of public funders and museums neglect this aspect often.

- 286 replies

-

Indeed, I thought that many of the photographs may have been taken by (international) travellers. The Baltic coast, in which I am currently interested in, didn't quite attract so much international tourism. For the local summer vacationers, these maritime things were not attractive enough I suppose. In addition, due to WW2 there have tremendous archival losses. It's also a question of attitude towards the maritime history. The UK has much closer links with the sea than most other countries. There is a lot of information also in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Italy, and to some extent Spain and Portugal. France has caught on in more recent decades, but Germany is a developing country in comparison.

- 286 replies

-

I like that kind of research and it’s quite surprising how many photographs there are of this ‚remote‘ area. I found it difficult to find similar pictures for certain European areas. Perhaps there were more travellers in Mexico? For the bananas, you could look into seeds. I thought of caraway seeds, but they may be a bit small for 1/32 scale.

- 286 replies

-

I thought that the smokebox and the stack were a bit on the large side … but then such ships were often crowded around the bow. Check that in then end there is enough space for cranking the winch.

- 128 replies

-

- zulu

- sternwheeler

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thank you very much gentlemen. I don't do this kind of painting very often these days, so I missing a bit the routine (the last time I painted figures is already ten years ago. Thank god, the hands are still as steady as they used to be (which is not as much as I would wish). I found working acrylics with a brush always a bit of awkward because they either dry too fast or run too much. Perhaps I don't have the necessary practice. Perhaps I should go back to using oils for the faces etc., as I used to for 1/35 scale figures many decades ago. I gave it a try on some 1/87 figures for the botter-model, but was not so successful either. However, oils stay workable a long time, which is a plus and minus. With acrylics you can go back to the same area after a few minutes. It's always amazing to see what the real figure modellers can do with their brushes ... And yes, we may go through several bottles of Port per year, so there is always a supply of fresh corks.

-

HMCSS Victoria 1855 by BANYAN - 1:72

wefalck replied to BANYAN's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1851 - 1900

Pat, think a jig like this will work. On the other hand, I wonder whether a simple (but dimensionally precise) mock-up of the mast-head wouldn't be sufficient. The cheeks could be held temporarily in place with pins driven through the holes. This would then ensure a tight fit to the mast-head.- 1,013 replies

-

- gun dispatch vessel

- victoria

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Already another month passed, but not idle, albeit interrupted by several travels ... ******************* Painting the figures In order to better see how the sculpting turned out and any imperfections, the figures were given a spray-coat of matt white paint (Vallejo Model Air). This also served as a primer that made hand-painting easier. I like the consistency of Vallejo Model Air paints also for application by brush, but several coats may be needed for certain colours. The crew figures with a white base-coat Unfortunately, only at a relatively late painting stage some molding flash was noticed that could not be removed anymore. Also, it turned out, that some faces were actually not molded very well, which made it difficult to paint them. Painting such small figures requires a bit of a strategy. However, regardless of scale, I usually begin with the face and any other exposed skin. The reason is that, apart from white, most other clothing colours tend to be darker and have a better coverage and perhaps more importantly, clothing covers the skin, so in order to get precise edges between the clothing and the skin, it is more natural to paint towards the skin, rather than trying to approach the clothing with the skin colour. At this scale no attempt is made to paint eyes and such details, but rather to paint the shadows under the eyebrows and in other parts of the face. I find the way of how Canaletto treats the staffage in his paintings a useful reference. It is fascinating, how he can bring the ‘people’ to life with just a few brushstrokes and blobs of paint. Almost completed paint job on the crew figures It may be counterintuitive, but it is sometimes better to begin with painting details and then work with the main colour towards them. Or to use an iterative procedure: painting say the main colour of the clothing, then adding detail, followed by touching up with the main colour, where the brush had gone astray. Narrow lines, such as embroidery, are difficult to achieve, but too wide lines can be reduced in width by painting the main colour against them. The painting proceeded in several iterations and I have not taken pictures of the various steps. The crew ready to go on board The Vallejo Model Air paints have a slight satin sheen, which is good for many applications, but in order represent cloth better, the figure were given at the end a light spray coat with matt varnish. To be continued ....

-

BTW, if you repost pictures from other peoples' Web-sites, it would be polite to provide a reference to the source ...

- 62 replies

-

- belle poule

- OcCre

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Chairs! Let’s see your chairs.

wefalck replied to Desertanimal's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I am surprised that they are allowed to sell this still. I thought stools/chairs with three or four casters don't get a CE certificat anymore due to the risk of them tipping over and rolling away under your butt ... chairs have to have five casters these days. -

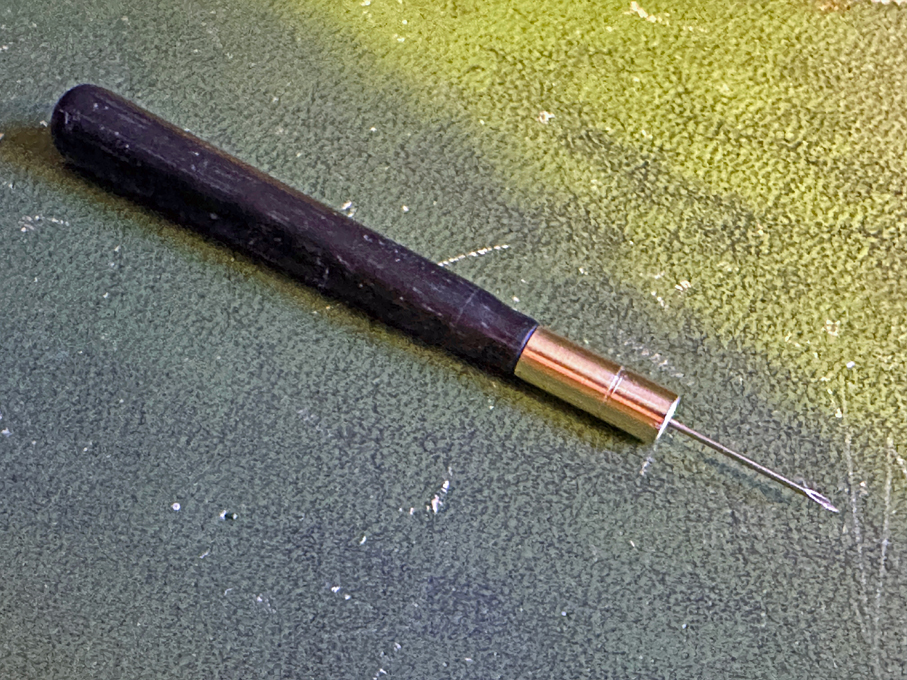

Some people, including myself, use hypodermic needles as marlinspikes for making false splices miniature rope. One has to blunt the edges a bit - they are obviously very sharp and meant to cut, but you don't want to cut your rope. You twist the rope a bit so that it splits and then you push the 'marlinspike' through. Now you can feed the free end into the needle and slowly pull it out with the rope inside - repeat and you will end up with a reasonable splice. As I had a nice ebony handle lying around (which may have come from some antique medical instrument from my fathers estate), I made a brass ferrule for it and cemented a hypodermic needle into it. I think it was a 20G (yellow). For serving, I would try to get hold of some 16/0 fly-tying thread, which is not fuzzy. Indeed, serving without some 'helping hands' is difficult. I tend to use half-hitches, rather than just winding the thread around. Each turn in this way can be set and does not come loose. Of course, having/building a serving machine would be the next step up ...

- 286 replies

-

I gather there various constructional and hydrodyamic factors play together. Modern freight carriers have a much higher L/B-ratio than these rowing boats. A long parallel midship section is not detrimental to water resistance, but rather encourages laminar flow. If you did cut out that part and stuck together the bow and stern sections, the overall shape would not be so dissimilar to that of the boats of old. One can only speculate how clinker building developed and Greenhill believes that it originates in expanding dugouts by adding planks while at the same time the dugout mutes into a sort of hollow bottom plank, eventually becoming the keel. This lends itself to smooth curves in (shell-first) planking with large radii. There is strength in flexibility in this construction as we know from experimental replicas. It is only with plank-on-frame construction that tight bends are possible, leading to a rigid skeleton with a shell around it (certain Dutch vernacular boats are probably the most extreme examples in that respect).

-

Talking about memories, I seem to remember a whole room being dedicated in the NMM in Greenwich to the Sutton Hoo find, where they showed a section of the boat in 1:1 of what it looked like after excavation: basically there were the imprints from the planks long gone and the remains of the iron rivets. I gather if several 'old codgers' get onto the same project that cuts down construction time compared to a single beavering away in his own workshop. Preparation and fitting times for planks are not so much different whether it's 1:1 or a model.

-

Another source for extremely thin, long-fibre 'Japan'-paper are supply shops for art- and book-restorers. This paper is used to 'invisibly' double up ripped or damaged book pages and works of art. I got one that has only has 8 g/sqm. For extremely fine woven fabrics serigraphy (screen-printing) supply shops are also an interesting source.

-

Chairs! Let’s see your chairs.

wefalck replied to Desertanimal's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I use a standard lifting office-chair with armrests. The inclination of the backrest can be also set. It was given to me for free as an office surplus. -

Somehow I haven't been aware of this project, thanks! One process that seems to be not so in line with how they did it in the old days is the use of templates. OK, they try to replicate an existing ship. In those old days they probably strung a cord from bow to stern and used this as reference to ensure that the boat turned out symmetrical, but otherwise everything would have been shaped by eye, I think.

-

Under the right light conditions and with the right background, this could look almost like the real thing 👍🏻

- 174 replies

-

- Vigilance

- Sailing Trawler

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

HMCSS Victoria 1855 by BANYAN - 1:72

wefalck replied to BANYAN's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1851 - 1900

I have both, single and double roller filing guides (or 'rests' as the watchmakers call it), but never really understood the value of a single roller guide ...- 1,013 replies

-

- gun dispatch vessel

- victoria

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

... absolutely and if you are myopic in addition, this multiplies the magnification you get out of your myopia, when you take off your normal glasses. For years I got the 3x magnification by just replacing my normal glasses with plain safety-glasses. Now I need the additional magnification of reading glasses 😢

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.