-

Posts

3,556 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Cathead

-

@rcmdrvr I think I found the source of your problem. Reading ahead in the instructions, at your stage (page 8 ) they have you pre-drill mounting holes for the cannon, 1/4" deep as you said, but they don't say anything about mounting the cannon at this time. They're just getting the hull ready for later detailing. You don't actually mount the cannon until page 16, where it says "trim [the cannon] as necessary so that the bottom of the muzzle protrudes about 1/8" from the casement, and glue it in place". This makes sense as mounting the cannon this early is just asking for them to get knocked askew during other early building. It would probably have been good for the instructions to clarify that the cannon don't get added at this step, but it's also a good idea to read all directions first! It also doesn't hurt to keep checking against the box imagery and other photos, like doing a puzzle, to make sure things seem right. We've all been there, it's no big deal. Is it possible to remove the cannon and trim them down for later re-installment?

-

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Ken, Alley Spring Mill was built in 1894 but has been in good condition for a long time. The site became a Missouri state park in 1925 and eventually was turned over to the National Park Service when Ozark National Scenic Riverways was formed in the 1960s. Here are the results from a partial day of work. I cut and installed all the purlins on both sides; note the brilliant fall colors on both maple and walnut in afternoon sun. And if you look close in that photo you see that I got started on the roofing as well. I cut metal roofing panels to length using a circular saw. These went up pretty quickly. I got most of one side done before it was time to stop and make dinner. Here you can also see how this will fit nicely with the house itself, since I'm using the same panels as are on the house (making use of leftovers). Here are a couple neat photos Mrs. Cathead took toward the end of the day. She saw pretty clouds behind me, and though I'm somewhat obscured, they have an artistic feel. The second one shows more fall color developing here. Thanks for looking in, more progress should occur in coming days. -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

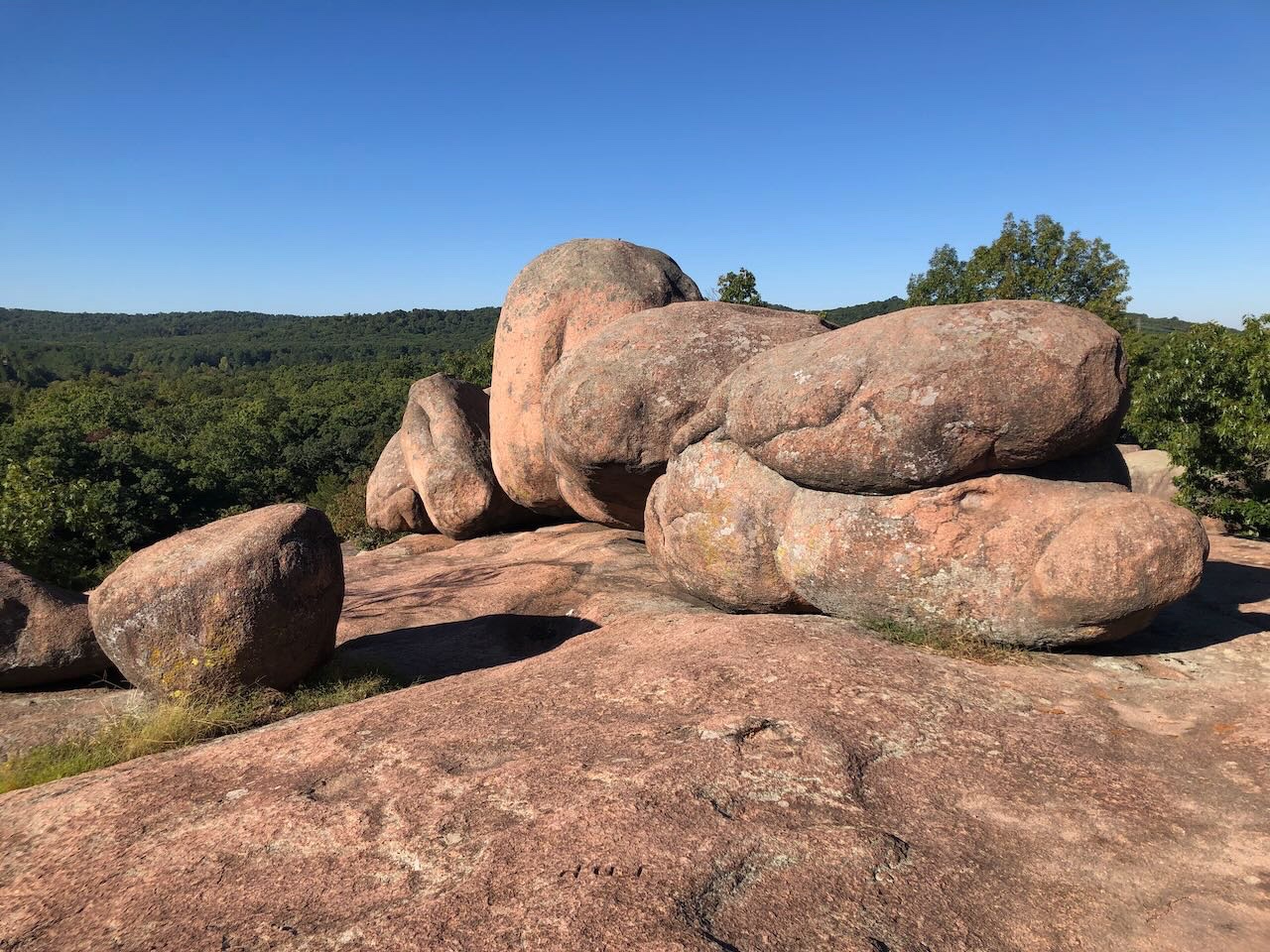

And for those interested, and since the rules are looser here in Shore Leave, here are a few photos from our quick trip down into the Missouri Ozarks. Canoeing along the spring-fed Current River within the Ozark National Scenic Riverways, including the wonderful Cave Spring, accessible by canoe. Alley Spring Mill, one of the most well-known historic sites in the Ozarks: Otters playing in the clear waters of Round Spring: Tumbling waterfalls; deep, clear water along the Black River; and prairie grasses on a ridgetop glade, at Johnson's Shut-Ins State Park: Fabulous granite formations and a granite-walled enginehouse from an old quarrying railroad at Elephant Rocks State Park: And technically not the Ozarks, but part of our recreational reward nonetheless, a Major League Soccer game in Kansas City, in which a dominant home win eliminated one of our greatest rivals from playoff contention. My stepfather's back home now, so it's up to me and Mrs. Cathead to finish the rest of this project! -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

And the rafters are installed. Here they are fully notched and ready to go: I started with the outermost pairs: Then worked my way inward, to help ensure everything lined up ok. A few had to be adjusted to fit, but nothing major. Here's the finished rafters: And here's a shot in the other direction with a nice maple starting to turn: -

I read that book, too, and had the same thought that the ship would make an interesting modeling project. It'll be neat to follow along on this. I enjoyed the book overall, though it was pretty clear the author knew nothing about nautical affairs and hadn't bothered to run the book by anyone who did. But the history itself was interesting.

-

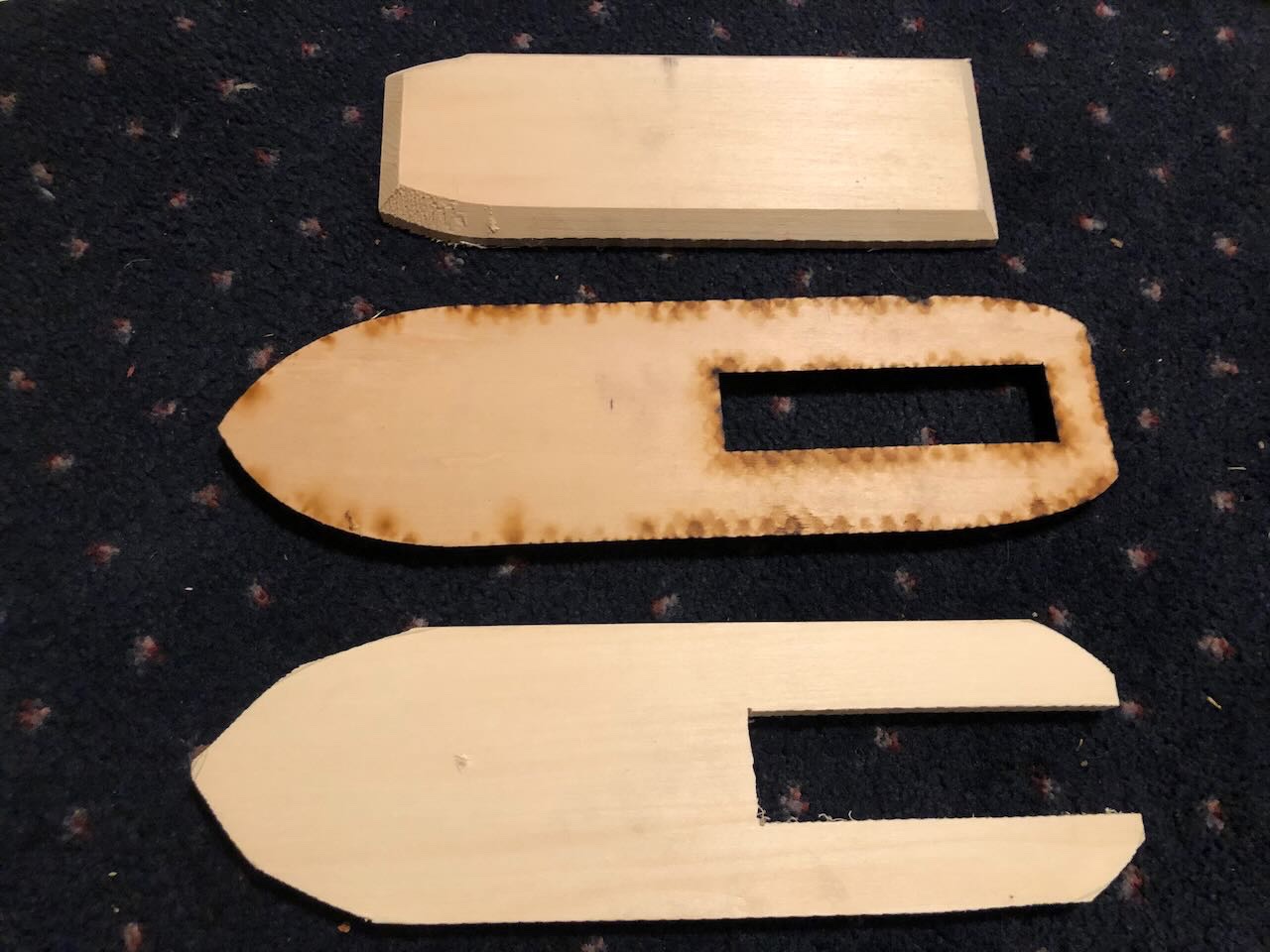

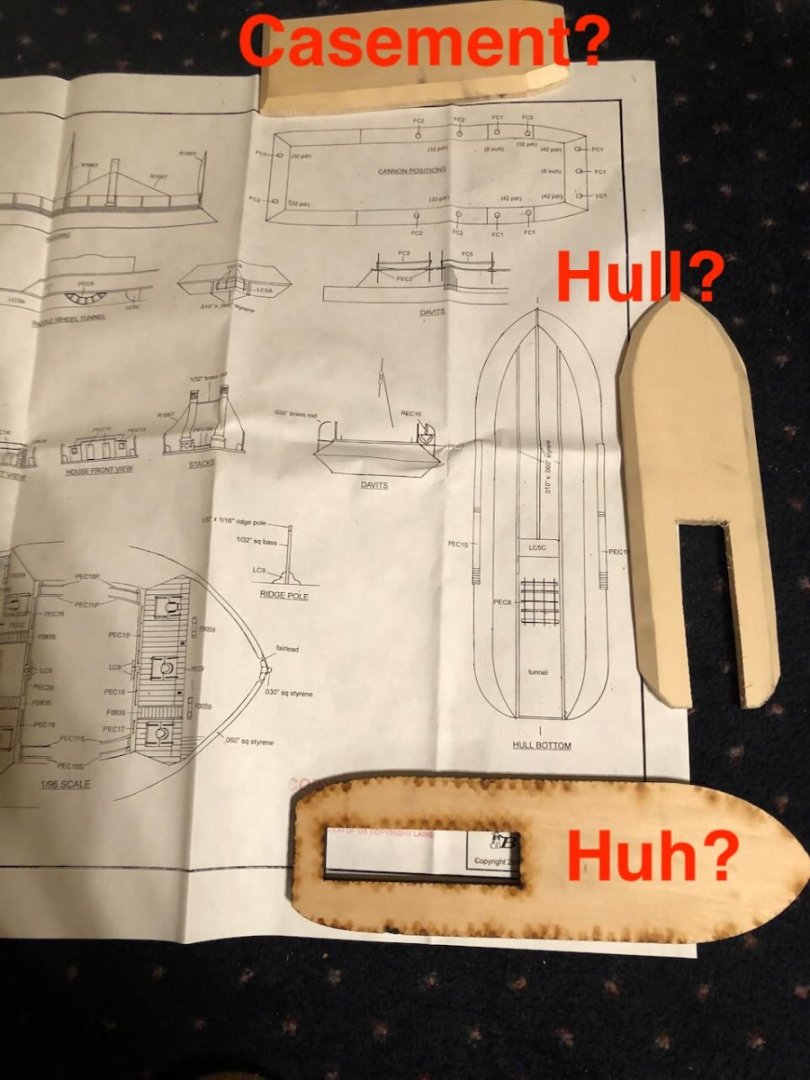

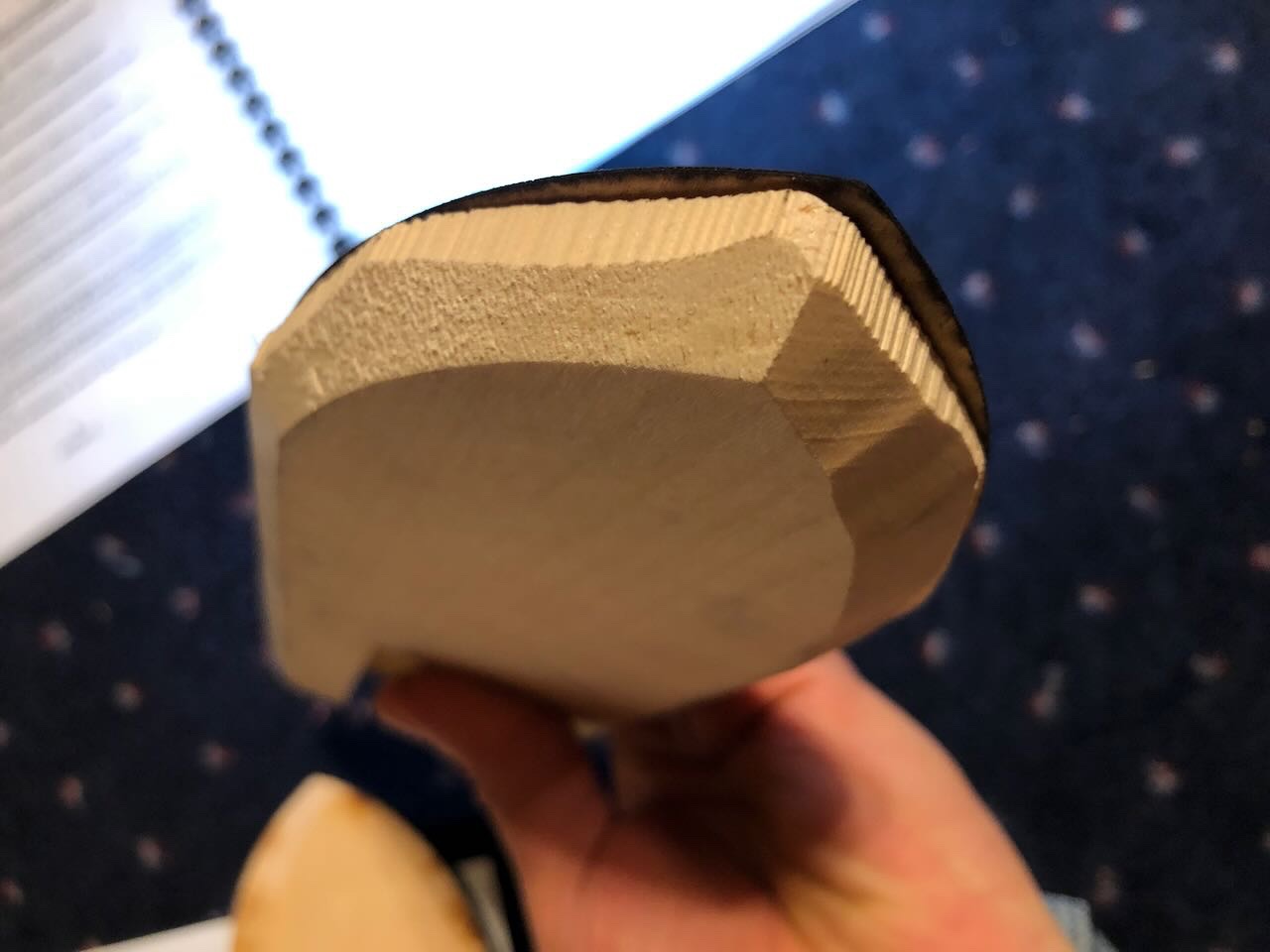

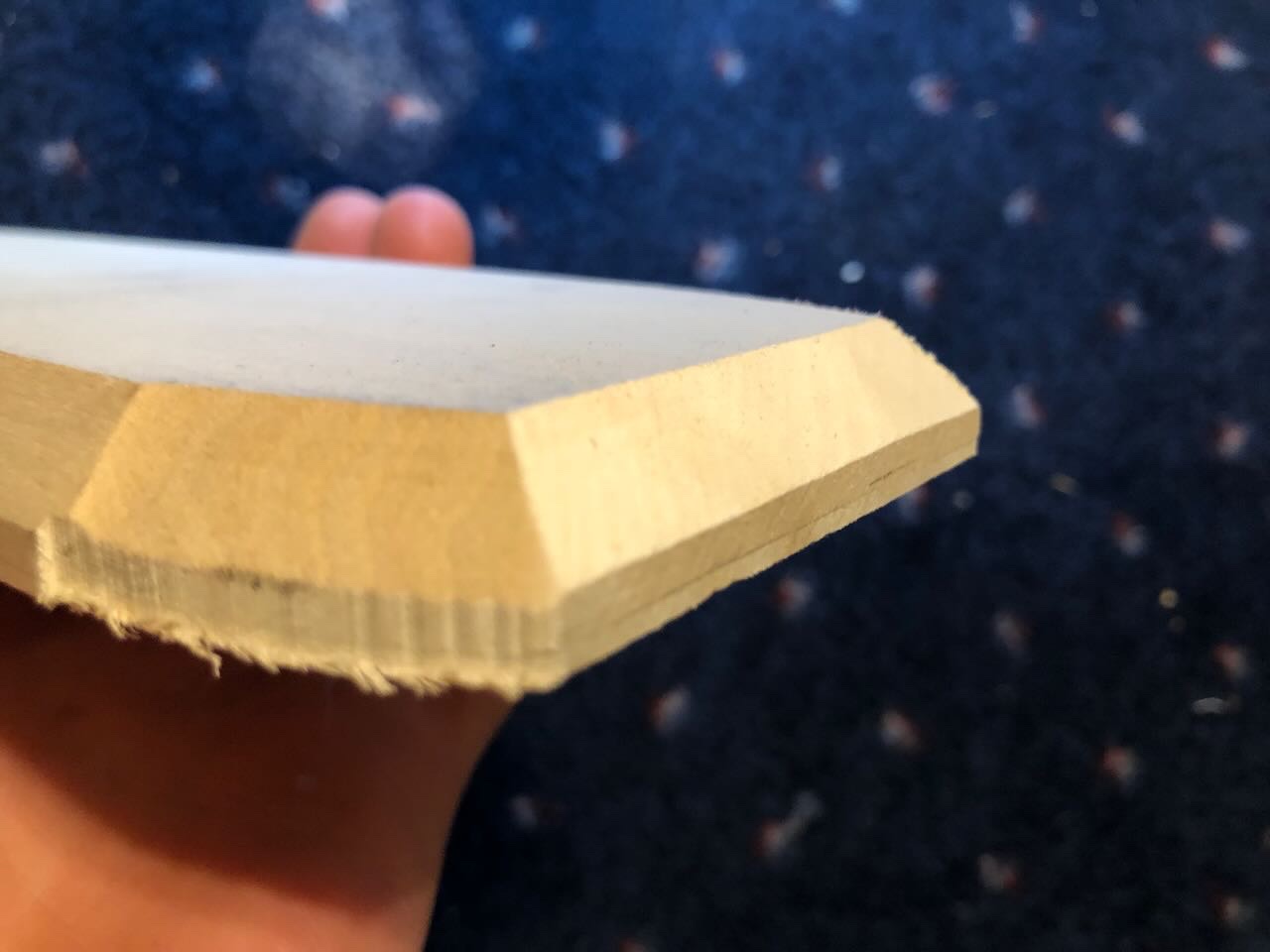

Thanks, Phil! Just a quick update, as I've been away from home for the past week. But the replacement hull/casement parts promised by @MrBlueJacket arrived, and boy do they make a difference! They're cut much more crisply, at the proper angles, and essentially answer most of the questions I posed earlier because now it's obvious how to shape them. So thanks for that quick response; errors happen in manufacturing and it's no big deal since I've got the finished parts now. Here are two side-by-side comparisons of the old flawed and new correct hull: And same for the casement: Now I'm excited to get back to this sometime next week, since I can see a clear path forward with these parts. I also updated the earlier part of the log, so as not to scare off any readers who see those old parts. Also, be sure to check out the other new Cairo build log by @rcmdrvr, who's making rapid progress so far.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks for starting this! You've shot ahead of me as I've been out of town most of the week, so now I can use you as a trailblazer. Looks like you got the right-shaped hull and casement pieces, unlike the oddball pieces that showed up in my kit (and that BlueJacket quickly replaced). Keep up the good work.

-

Lovely! A pride-worthy endeavour. I hope you enjoy viewing it for many years to come, and thanks for sharing your work with us.

- 104 replies

-

- Bluejacket Shipcrafters

- smuggler

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Another productive day, but only one image. After assembling most of what we'd pre-prepared, it was back to manufacturing. My stepfather spent much of the day carefully setting up a jig to precision-cut all the rafters so they'll drop nicely onto the beams, and finished cutting them as the day ended. I got all the longitudinal angle braces finished and installed; these definitely had some quirks and took some adjustments to fit right. It doesn't look all that different overall, but it's another day closer to completion. We had various other friends and neighbors stop by to help out and socialize; all weekend has been like a grand old neighborhood barn-raising with a nice community of people. Work will stop now for a week, as the reward for a week of hard work is a week of hiking/floating/sightseeing in the Missouri Ozarks and a quick trip to Kansas City. So I won't be getting back to this until early October. But the building is now nice and strong and can wait quietly for me to return. Thanks for reading, take care, looking forward to being able to update again in a week or so. -

@rcmdrvr Welcome! I find build logs to be a really useful resource, both for advice and help, but also for motivation. Knowing others are paying attention to, and care about, my work, helps keep me going and helps discourage sloppiness.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Got them, wonderful resource, thank you! May not get back to this project right away as (a) still very involved in kitchen-building and (b) will be taking my stepfather on a hiking/floating trip in the Ozarks next week as a thank-you reward for all the hard work this week. Plus I want to wait for the new hull from BlueJacket.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Today we started assembling and raising the structure. We essentially declared an open house at the farm over the weekend, with various friends and neighbors invited to stop by and help as desired, which they did. One fellow showed up in the morning and stayed through evening, he was having such a good time. We'd made a bunch of food and had a nice spread available for snacking (sourdough bread, homemade hummus, grain salad with garden veggies, homemade sumac wine, orchard persimmons and pears, etc.). I'm too tired to go into serious detail, but here's a photo essay of the day's progress. Hauling the "kit" up around behind the house: First frame assembled, bolted together, and raised: Second frame assembled, bolted, and raised. Both frames braced temporarily: Setting a king post: Both kingposts installed: Getting the large longitudinal beams up onto the structure: Setting a beam in place (I designed the structure so these heavy pieces would just drop into their slots, with minimal fussing): Marking the external overhang on a beam before raising it into its slot: Raising the center beam onto the king posts: Checking for plum and making final adjustments: A dusty, tired, happy work crew (stepfather on left, me at center, super-helpful friend at right): Status at end of day. You can also see more of Mrs. Cathead's work on the creekstone walkway left of the structure: We took some really cool time lapses of the construction process, which at some point I'll edit into something I can share. But not right now, I'm whipped. Tomorrow is more of the same. A variety of friends and neighbors stopping by throughout the day, lots of good on-farm food on hand, glorious weather (sunny and temperate both days). Tomorrow we'll cut and install the six angled braces that help support the longitudinal beams, then move on to shaping rafters. Like many models, this looks great from afar, but has some flaws when you look closely. Some of the joinery doesn't match as well as it seemed to when we tested it in the workshop, but it all holds together nicely in the end. Bolts cover many sins. You'll notice I stuck to faraway shots! Overall I'm pretty thrilled with how this came together, my schedule for the week has played out the way I hoped and this was what I hoped to achieve by the end of today. Thanks for reading, hope you enjoy the photos. We'll see what tomorrow brings. -

Thanks, Nic, that's a relief! Will look forward to the new piece. I'll send you a PM with the order number to ensure you know where to send it. Brian, it would certainly be interesting to see your plans if it's not too much trouble. Did you mean digital or mail?

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Mark, I should have clarified that the instructions do provide a clear photo of how to round the stern sections, but not for any other part.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

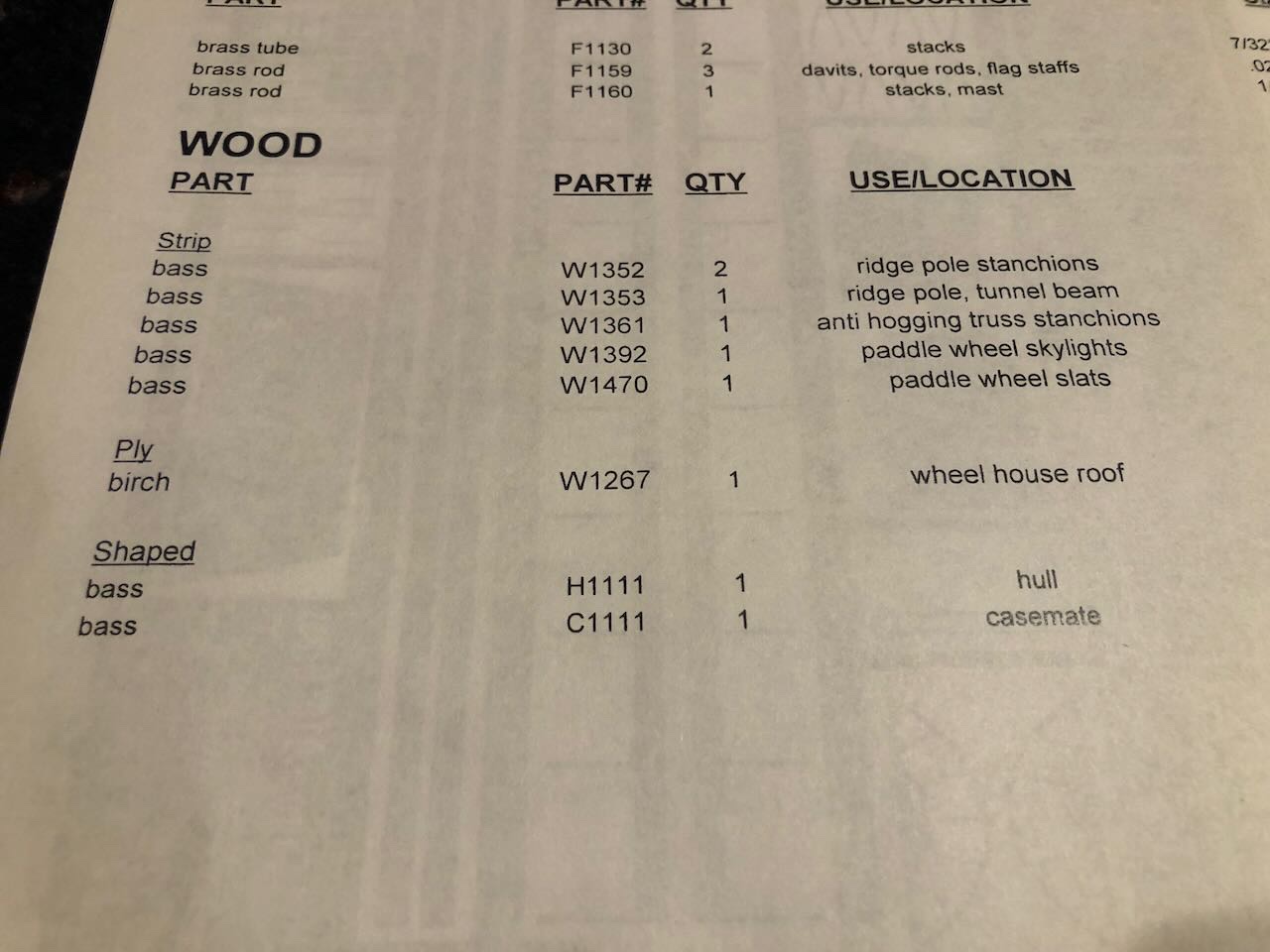

So after an intense week cutting and shaping all the parts for the outdoor kitchen (essentially making the "kit" we'll start assembling this weekend), I decided to take Friday evening to relax and fiddle with my other kit. By the way, if you want to follow the kitchen project, I yielded to peer pressure and started a Shore Leave build log. I started reading through the instructions and comparing them to the kit contents and, unfortunately, halfway through the first page I'm already pretty confused. The instructions are pretty minimalist with almost no useful graphics or drawings. Let's work through my confusion step by step. LATER EDIT: Most of the confusion related below turns out to have been caused by faulty hull and casement pieces in the kit I was sent. After I sent a message to BlueJacket asking about this, they promptly sent out new parts which are much cleaner and clear up most of the confusion. See later posts in this thread. Just noting it here so prospective builders aren't scared off; you shouldn't expect to see the parts below in your kit! Although the instructions remain a bit vague, proper kit parts make it much easier to work out what to do. Question 1: What is this piece? There are three big pieces of hull-shaped wood in my box. Unfortunately, only two seem to exist in the instructions: casement and hull: And the plans pretty clearly show a two-part hull; I'm pretty convinced I've identified the listed casement and hull. The mystery/extra piece seems to be the extra-charred piece in the middle of the first photo, as it doesn't correspond to anything on the plans: So what is this? A packing mistake? Question 2: Is gluing the laser-cut deck on before sanding the hull really a good idea? The hull/casement pieces are VERY rough and will need extensive smoothing and reshaping. The very first step in the entire project is to glue the thin laser-cut main deck sheet onto the solid hull, before doing any shaping. This order makes me very nervous. First, it'd be really easy to take off too much of the deck while sanding the much thicker hull. Why not do rough shaping BEFORE gluing on the thin deck? Here are four photos showing how the deck looks when held onto the hull. The instructions blandly say "align it [the deck] with the hull and glue it in place" but it doesn't feel that simple. Notice in the photos below that the deck both overlaps and underlaps the hull in places, so how to achieve a smooth line along the entire thing? They also say that the deck should be slightly wider than the hull, but mine seems to fit with no overhang. Question 3: Is gluing the casement onto the deck before sanding really a good idea? Similar to Question 2, the instructions next tell you to glue the casement to the top of the main deck before doing most shaping (they do tell you to sand the fore/aft parts, presumably because these cut across the deck surface). But as with the hull, there's a LOT of shaping to be done, and it makes me nervous to do this with the thin deck already glued on. Here's the very rough casement piece: Basically, you're supposed to make a hull-deck-casement sandwich before doing any shaping around the perimeter, and that just makes me really nervous. Question 4: What's the intended shape of the hull/casement when sanded? Guidance for shaping the hull/casement is also very limited. The instructions just say "sand the hull and casement sides smooth". OK...does that mean convert the two angles present to one single surface? Or sand both surfaces smooth, preserving the original angles? If they're supposed to be one surface, why not just cut the piece that way in the first place? Same question for the hull, which is also a rough two-angle surface over much of the piece (see earlier photos). The plans imply that all of these pieces should be single surfaces from top to bottom, but it's not made clear and is really making me hesitate. The curve of the bow is also pretty inconsistent on the port and starboard side, which will make shaping extra-fun. Question 5: How to align the casement on the hull? When it's time to glue the casement on, the instructions just say "mark the location of the casement on the main deck and glue it in place". OK...based on what? I guess measurements from the plans? This is confusing because the scribing on the deck extends well underneath what the casement would cover, so it's initially unclear whether we're supposed to be lining up one of the casement ends with where the scribing stops: As far as I can tell, and based on the plans, you just have to overlap the deck scribing at both ends, but this seems unnecessarily confusing to me. So far, not that impressed. I'm a few paragraphs in, already I have five questions that are confusing me, I just spent a bunch of time photographing and writing up these questions, and I'm definitely not relaxed. I'd be very grateful if @MrBlueJacket is around and could clarify these for me. I think I understand how things are meant to align (based on the plans and writing up these questions), but it took a while to figure out from the vague instructions. I'm a reasonably experienced modeler and wasn't expecting to be this stumped this quickly. BlueJacket sells a separate CD of build images that would probably be really helpful in figuring out stuff like this, but I didn't buy it. Felt kind of like a luggage charge, and I thought it was reasonable to think the original instructions and plans would be sufficient. Maybe I'm just thinking slowly after a long week of 1:1 scale woodworking, but these seem like questions that could confuse other builders, especially new ones. Probably won't get back to this for a few days, so letting these ideas simmer will probably help me sort them out, along with any suggestions/interpretations from commenters. Thanks for reading, hopefully I can show some actual progress soon!

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

A hint for future builds, you can see some places in the planking where there are pretty clear knuckles, which tells you that the underlying frame could have used more fairing. All the planking should be perfectly smooth, ideally you shouldn't be able to tell where the frames are. But as said before, some nice filling and sanding will work wonders, as will paint. And you've kept the planking runs straight, avoiding the dreaded upward-sweeping bow curve that happens when people don't pay attention to how hull planking works. I forget, is this a double-planked hull or is that the outer layer?

-

Sorry I didn't catch up on this until now. I've never done a double-planked hull but I think I've seen advice elsewhere to primarily wood glue but use small spots of quick-curing CA to hold the planks down while the wood glue dries (which still doesn't take long when you use a thin layer). But make sure you use a thin layer of glue, overdoing it will warp planks and make a mess. Stern repair looks nice.

-

Polaris by JDillon - OcCre

Cathead replied to JDillon's topic in - Kit build logs for subjects built from 1801 - 1850

Have you considered making some simple drawings, using colored pencils to sketch out different color schemes? If you have digital skills you could take a photo of the hull and use a simple art program to lay different colors over that. Having a set of comparable images/drawings in different color patterns may help you (and anyone you want to run it by) make a decision. -

@juhu, that image is from my scratchbuild of Arabia, an 1856 sidewheeler, so isn't directly relevant to Chaperon, an 1884 sternwheeler. In that case, the planking layout was based on photos of the wreck as it was excavated. The remaining planking was incomplete but clearly showed a set of angles converging toward the stern, following the boundary between guards and hull, with a straight run of planking only being found within the hull: For visual comparison, here's the photo you referred to, which was my interpretation of the evidence available: There was a discussion of this planking in the log, starting with this post, if you want to read more. Only a tiny fraction of riverboats built were ever photographed, and especially not from angles that clearly showed the layout of their deck planking, so we can only draw so many broad conclusions. Even fewer have been found and excavated. Also note that the planking pattern you're asking about is at the stern, not the stem. Arabia was a sidewheeler, while Chaperon was a sternwheeler, so the deck and hull layouts were quite different. Sternwheelers had a much squarer end, more like a barge, to support the sternwheel, while sidewheelers had a rounded stern more like a normal ship because the wheels were along the sides. For example, Bertrand, an 1865 sternwheeler, had a straight run of planking all the way along, like the kit depicts for Chaperon. We know this from the archeological drawings from her excavation; here's a photo of her planking underway on my model (based on those drawings), where you can see that the layout is pretty similar to Chaperon. I'd say the Chaperon kit has it right, between the fact that it's a more recent and well-documented prototype, as well as being a sternwheeler whose hull shape lends itself to straight planking.

- 158 replies

-

- chaperon

- Model Shipways

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Those were all closeups, so let's take a broader view of today's work. First, here's the glorious bank of clouds sweeping in with the cold front. Quite a change from the blazing clear sky: Here are a couple shots Mrs. Cathead took of us working in some nice afternoon light; by this point the temperature had dropped so far that the sun felt good rather than brutal: Here are two shots of a completed frame being test fit: Using the diagonal method to check square, this came out to < 1/2" off-square for an 8'x10' frame. Seems acceptable for hill country carpentry. We got a good start on the second frame before dinner time. With a chance of rain overnight as this cold front passes, we cleaned up the workspace and stacked all the pieces well off the ground and under cover. Seems so small like this: Tomorrow I hope we can finish the other frame, putting us on track for erecting the structure this weekend, as Friday will be somewhat busy with other commitments. Not sure that really does the last few days justice, but maybe you get the idea. Will be really fun when I can show photos of this all coming together in 3D. Thanks for following along! EDIT: Meant to add that, at dinner, we rewarded ourselves with 100% on-farm tacos (home-grown and -processed corn tortillas, stuffed with garden beans, peppers, onions, and tomatoes, along with log-grown shiitake mushrooms). OK, I lied, we added grated cheese from a good friend's nearby goat dairy. Also a big pile of fresh sweet corn picked 10 minutes before dinner. Fresh pears and persimmons from our orchard are also abundant right now. -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

It's actually been a very dry heat, more like North Texas or New Mexico. We've been in moderate to strong drought most of the summer, and this late fall heat especially has been desiccating. A minor blessing, since I'd much rather work in dry heat than Missouri's normal swamp-like humidity. On to the project update! It started out brutally hot again, racing up above 90º by noon, but then the cold front arrived. Clouds built in, cooler winds started to blow, and the afternoon was quite lovely. We're forecast for a high of 68º by Thursday and 62º on Friday. We got a lot done and I'm feeling pretty good about the timeline. Here's a sequence showing how I cut the long, thin mortises at the top of the posts, which will hold the 2x10 main beams. After measuring out the slot, I drilled out the ends to make chiseling easier, then cut the outer edges freehand with a chainsaw: I then cut a few inner slots with the chainsaw to ease material removal: I then used a chisel to empty the slot and clean up the interior: And finally tested the fit with a scrap piece of 2x10: Elsewhere, we cut a lot of mortises and tenons for all the different angled supports. Here's my usual way of doing that. After measuring the mortise, I used a small drill to mark the corners and edges: I then used a 1-1/2" spade bit to ream out most of the area. I used a drilling jig with a stopper to get the depth roughly right. Notice how I used the small drill bit to pre-open the areas the spade bit wouldn't reach: I then used a chisel to clean up the edges and interior: Cutting the tenons was pretty straightforward and I only took one photo. I just marked out the area, use a circular saw set to the right depth to cut a bunch of slots, then cleaned them out with a chisel. Here's what it looked like partway through one: With that I hit the system's photo limit for a single post, so will continue in a new post. -

Polaris by JDillon - OcCre

Cathead replied to JDillon's topic in - Kit build logs for subjects built from 1801 - 1850

I'm no expert, but those cannons look awfully packed together. No room to work around or behind them. Plus no room for a train tackle (to haul the guns inboard after firing). When you post other peoples' photos, can you provide a link to the build log or other location you got them from? That way they get proper credit, and readers can follow up (for example, understanding the gun spacing shown here would be easier if I could locate the relevant log). -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Yep, we're honing regularly. And drinking lots of ice water. I don't drink soda anyway and restrict my liquor to at most a beer or glass of wine with dinner. Yep, it smells amazing. The sawdust is supposed to be especially caustic to lungs, and I often wear a dust mask when sanding/cutting cedar, but it's just too hot out. I'd collapse from heat stroke if I did that. So I've just been trying to keep out of the way of the worst dust streams and breathe through my nose. Today was even hotter, reaching 98º. But we had what felt like a really productive day, in which things started to come together. No buffoonery! We were able to test-fit a whole post-crossbeam-kingpost-diagonal brace assemblage and confirm that the joinery is working as it's supposed to. My stepfather put his high-end woodworking skills to work and made some tightly fitting plugs for the wrong-way mortis. Never took any photos, too focused (or heat-addled?), but I'll get some tomorrow. Feeling cautiously optimistic that we're on schedule to raise the frames by this weekend.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.

.jpeg.09f6b4b017339a743d8c64098da16cd5.jpeg)