-

Posts

2,441 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Steve, What you are planning looks good to me. There are a couple of things I have done differently: 1. How springy is the fly tying line? I used a fine silk thread to seize lines. When it gets wet it is totally limp and doesn't try to unwind. 2. I used the white glue (Elmer's) to glue the ropes around the blocks. You want the glue to soak into the ropes. I dilute it 1:1 with water. However, the diluted glue does not make a really strong connection with the ropes. One other thing I did was make a "tumbler" and rounded off the edges of the blocks to get a more realistic look. https://modelshipworld.com/topic/19611-albatros-by-dr-pr-mantua-scale-148-revenue-cutter-kitbash-about-1815/?do=findComment&comment=981060

-

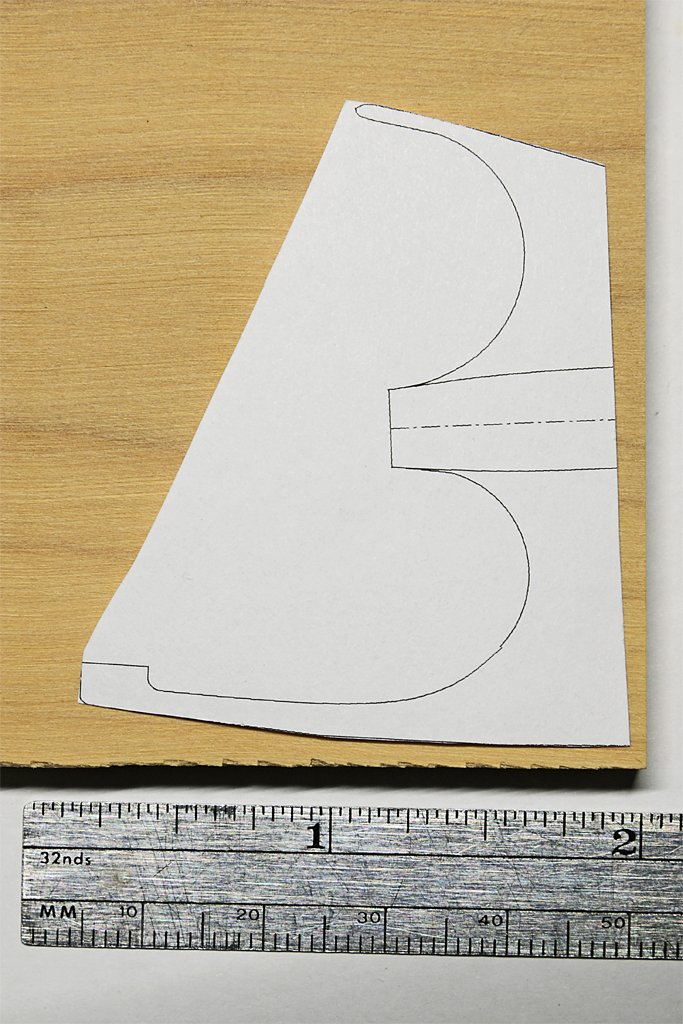

I have received the boxwood sheet that I needed for the stern frame. Here are the first steps for creating this piece. The piece cut from the 5/16 inch (7.9 mm) boxwood sheet nicely with the scroll saw. Now I will finish the carving with knives and files. This will take a while!

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

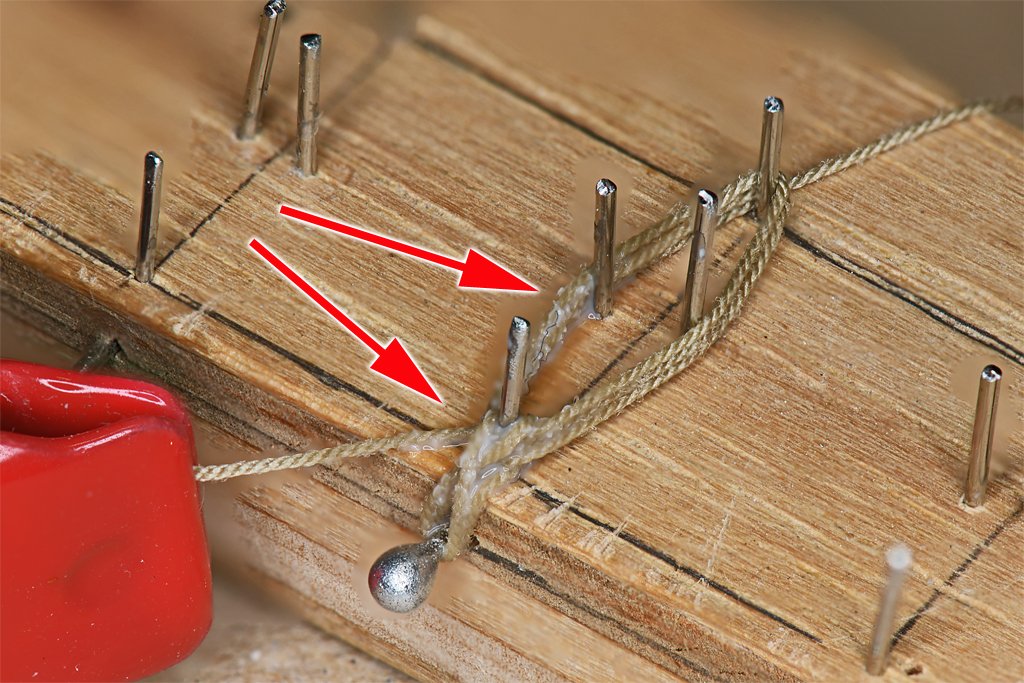

Mass production has started. Here are 37 coils of 0.012 inch (0.3 mm) rope - 30 finished and 7 in progress. The method I described above works pretty good. So far I have had 6 failures out of 36 attempts - a 16% failure rate. All of these occurred because I got into a rush and failed to follow the steps correctly. Operator error. Actually, on a few I thought I found a better way to loop the rope, and it turned out not to work. Also, the dilute white glue is a VERY weak glue and if the lines are not wrapped correctly the thing falls apart as it is being removed from the pins. However, the rope is still useable and already cut to length, so I just wrapped it again When I am on a roll I can complete wrapping a coil in about 45 seconds. But occasionally I lose control and the rope springs off the pins and I have to start over. Patience is a virtue ... I have found one slight modification that improves success. The last step before applying the white glue is to pull the long end around the pin on the right, to the opposite side of the pin from where the coils would normally wrap. This puts a bit of pull on the rope as it passes the two middle pins. I apply white glue to the side of the loop to the left of the center pins where the long end lays along the other strands to hold it in place after the loop is removed from the pins. With a bit of luck I am about half through this phase of the build. I had an "OH!" moment when I wondered if I had accounted for the 6 inches (152 mm) of rope I was using for these coils when I ordered the rope from Syren? I checked my rigging spreadsheet and I had allowed 7" (178 mm) for most of the rope coils, but only 3.5 inches (89 mm) for those that wouldn't need as many loops. So I was planning ahead. I should have over 100 inches (2.5 meters) excess rope for all the ropes used on the model! Whew!!

-

Thanks to everyone for the information.

-

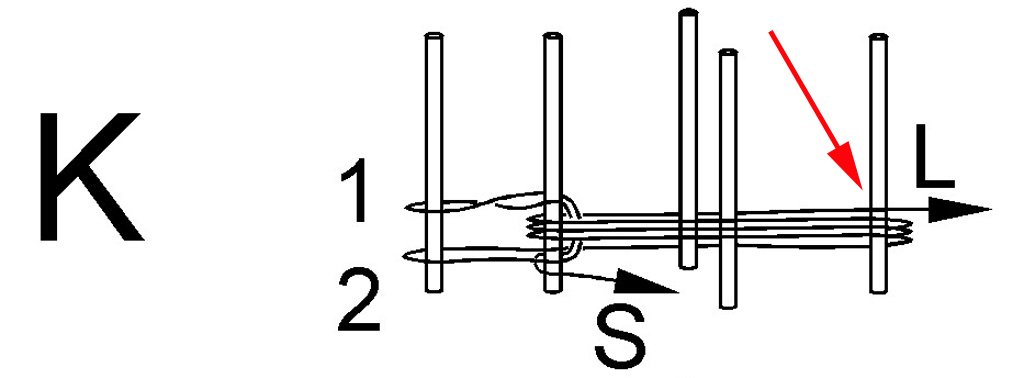

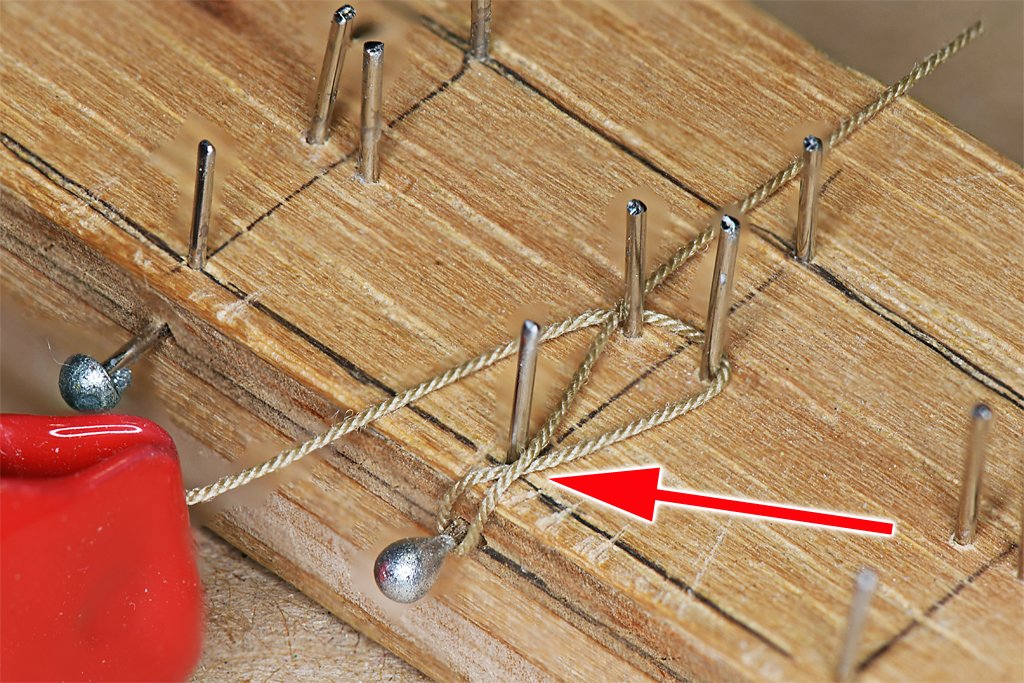

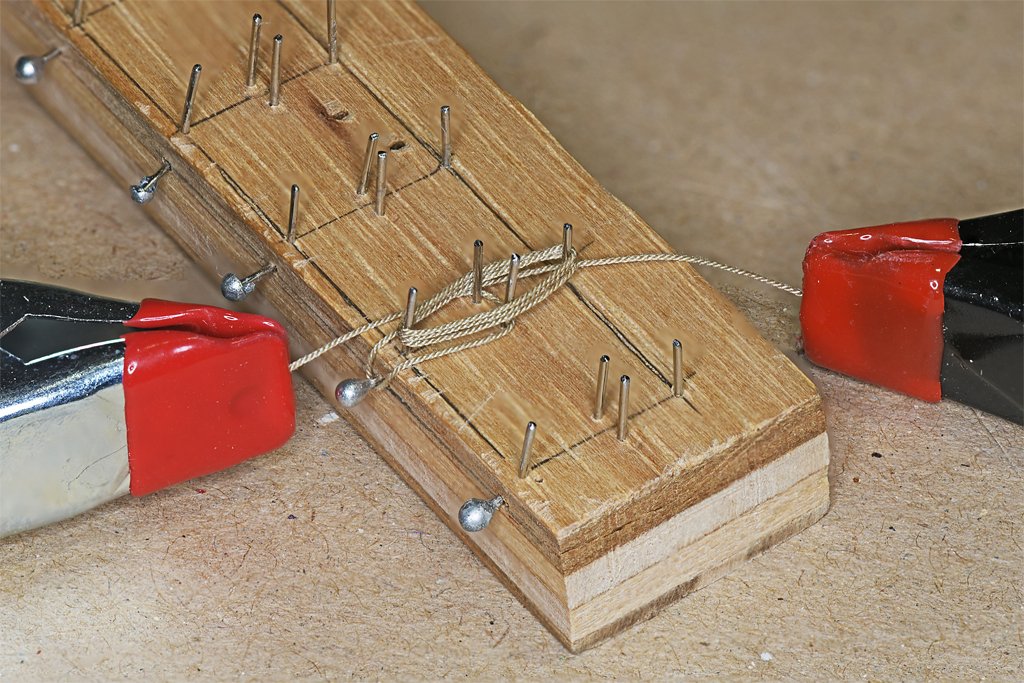

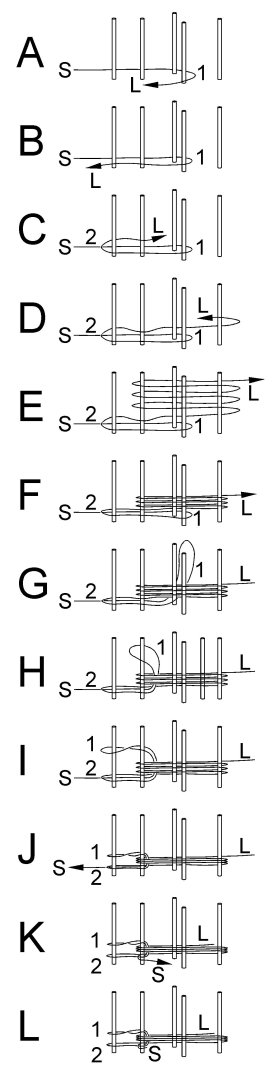

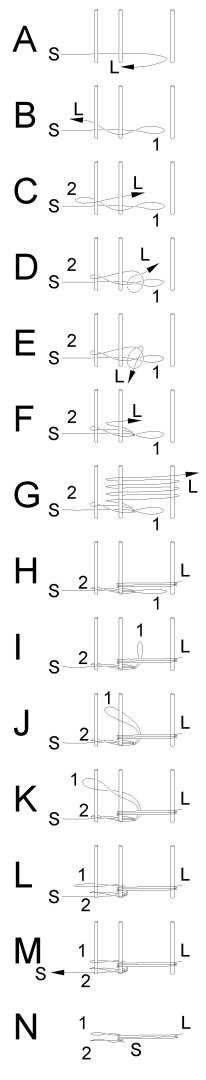

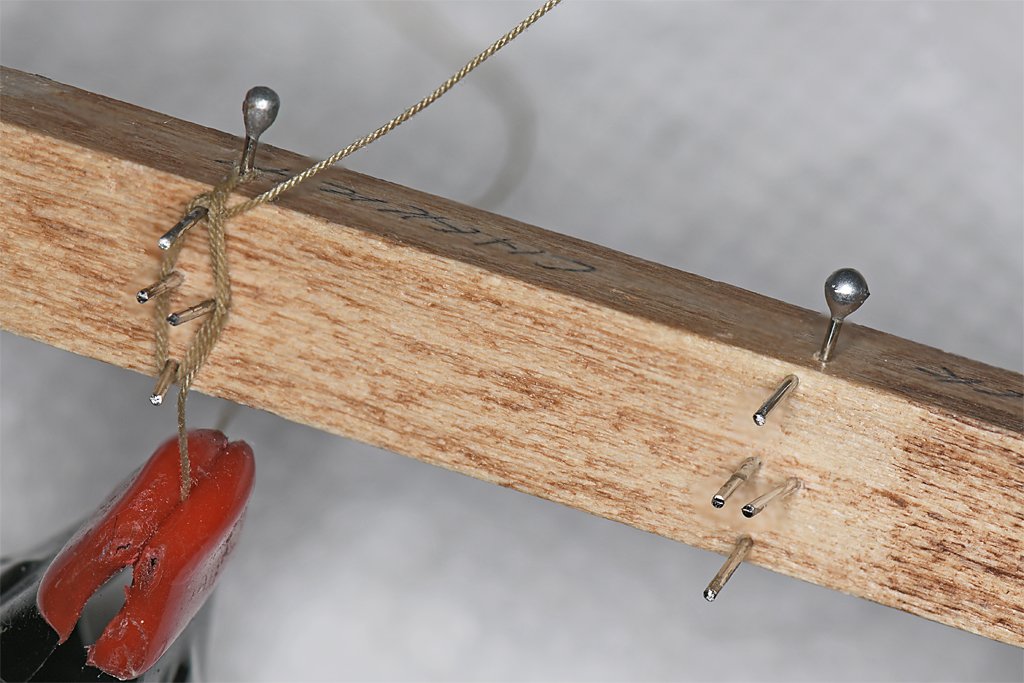

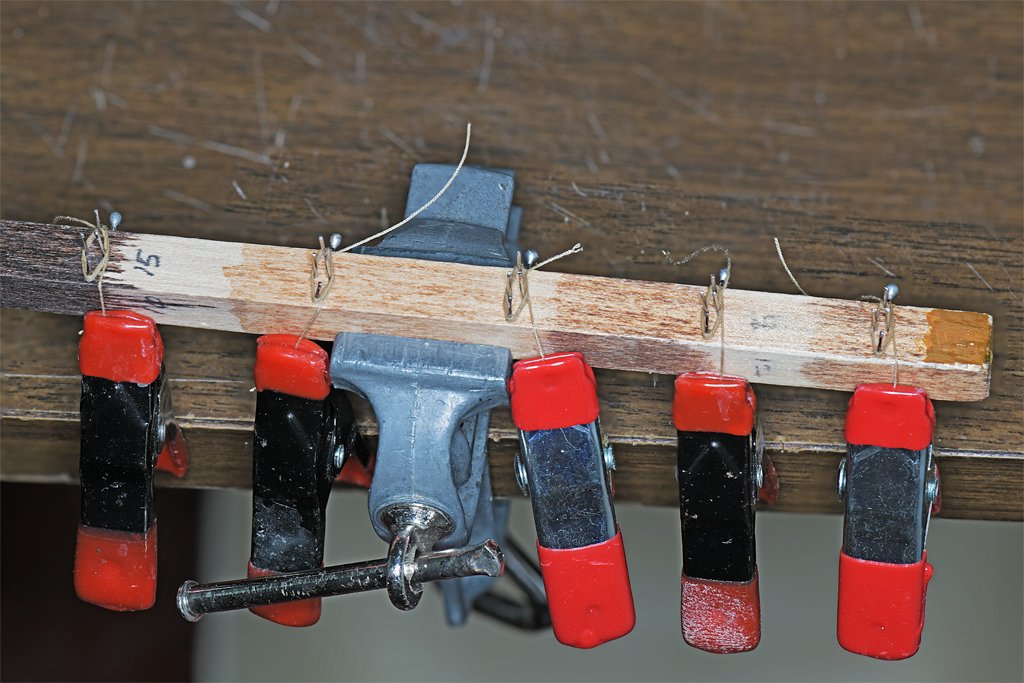

Try again, and again, ..., until you get it right! I think I am getting somewhere. I improved the technique described above, eliminating the knots. As before I have an initial loop to fit over the belaying pin and provide a fixed end to pull on, and a final loop that fits over the belaying pin to hold the rope coils in place. Here you see two coils made with the new method. They look pretty good! No bulging knots and they hang reasonably "naturally." These are test pieces made with carpet thread. I made a new tool, lengthening the distance between posts so the coils would hang almost to the deck. With the new tool I start with a 6 inch (150 mm) piece of rope and have only about an inch (25 mm) of scrap cut off the ends after the coil is finished. Here is the step by step procedure. S = the short, unmoving end of the rope, L = the long end that is wrapped around the posts. 1 and 2 are the two loops that fit over the belaying pin in the pin/fife rail. The arrows show when the ends of the rope are pulled. Be careful to not cut the short end too short! The new fixture has four pins for the rope coils to wind around, placed in an elongated "diamond" or parallelogram pattern (see photos farther down in the post). The fifth pin on the left serves as a pseudo belaying pin. A. I attach a small clamp on to the short end (S) to keep it from moving. Then the long end (L) is pulled around the two pins in the middle of the diamond pattern. This forms the start of loop 1. B. The long end is pulled to the pseudo-belaying pin (left most in picture). C. Now the long end curves back around this pin to start loop 2. It must curve back around the second pin to the left in the picture on the same side as the first leg of the loop. This ensures that loop 2 will be formed correctly to loop around the base of the belaying pin under the rope coils. D. The long end runs all the way to the right around the right most pin and curves around to start making the rope coils. E. The long end continues to wind around the four pins that form the coils until enough turns have been made for the piece that is appropriate for the rigging at a particular belaying point. Some may have fewer turns, and some may have many. F. After all the coils have been made they should be pressed down to make easy access to the end of loop 1. G. Pull the end of loop 1 up through the center between the coils. It was initially looped around the outside of the two central pins. Now it must be lifted over these pins so the "legs" of the loop are free to move inside the coils. This will pull in the short end of the rope. Be sure it doesn't pull in past the left most pin! H. Continue pulling the end of loop 1 back over the second pin from the right. This is where it hooks over the coils. I. Hook the end of loop 1 over the top of the left most pin. Put a twist in the loop as you hook it over the pin. J. Now pull on the short end (S) of the rope to tighten loops 1 and 2 around the left most pin. K. Place a drop of thin white glue on the cluster of ropes around the pin second from the left. The glue must soak into all the ropes at this point so the assembly doesn't become unwound after it is lifted from the pins. Pull the short end (S) back along the side of the coils so it will be glued in this position. L. After the glue has set you can lift the assembly from the pins. Trim the long end (L) to the desired length. Trim the short end (S) fairly close to the glued ropes, but leave a bit between 1 and 2 mm long. I find it useful to place a small drop of cyanoacrylate (CA) glue on this "tail" of the short end just to be sure it doesn't come loose. Here is a photo of the tool and a coil assembly in progress. The four pins of the "diamond" to form the coils are on the top of the tool. The middle two pins serve to open the coils and also serve to form loop 1. The "leftmost" pin in the illustrations above is the ball headed pin on the side of the tool. This represents the belaying pin. This illustrates step C showing how both legs of loop 2 pass on the same side of the left most pin in the diamond. This is important! This is a better view of the tool. I made seven "stations" so several coils can be made at a time. You can see how I use the small clamps to "tame" the rope - it wants to unwind from around the pins. This is step H after the coils have been pushed down on the tool. This is step M after the short end has been pulled to tighten loops 1 and 2 around the "belaying pin" shaft. I apply dilute white glue where the arrows indicate. I soak the bunch of ropes around the pin, and also paint some glue on the ropes down the side of the coil to glue the long end (running off the top of the photo) to the lower ropes of the coils. This prevents it from coming loose and causes it to hang down when the assembly is on the pin/fife rail. The short end is pulled off to the left side of the picture to pull it tight around the metal pin. After the glue dries the "belaying pin" is removed and the coil assembly is lifted off the pins. It helps if the pins are bent inward slightly. The coil shown in these photos was made with 0.012 inch (0.30 mm) rope. It is the first of 70 rope coils for the model.

-

Paul, The Wapama was one of my favorite museum ships. I visited it a couple of times back in the 1970s. I loved the interior woodworking, the spiral staircase to the passengers quarters, and the Captains cabin decorations. It was very interesting to go below into the engine room and get a close up look at the triple expansion steam engine. It was a crime for the National Parks Service to let it rot away! I am glad you are making this model. I have considered making one myself - for some time down the road.

-

Well George, You have come up with a puzzle there! Personally, I would go with putting the tackle pendants on first, and not last. Why? You are modelling a British ship, and the Admiralty was notoriously conservative about how things were done - and any change to the "right" way was resisted. And on their ships the mast tackle went on first. Marquardt was German and most familiar with northern European vessels - and those in Australia after he moved there. Petersson's rigging was based upon a model of the American made schooner Experiment, built in 1808 and sold to Sweden. He says the model was not an exact replica of the Experiment. Many in America followed Royal Navy standards, but each ship yard had their way of building vessels. The only certain thing I have found about rigging for sailing vessels, and especially schooners, it the it is probable that no two were built and rigged the same - not even in the Royal Navy. Ship owners, Captains and bosuns all had their "right" way to rig things. Unless you have the actual rigging plan for the Ballahoo, for the time period you are modelling it, I think you can do whatever you want with your ship! I agree with your reasoning for serving the after shroud to avoid chafing with the gaff sail. The fore course wasn't commonly rigged so it wasn't a concern for chafing the forward shrouds, and the spreader yard was usually fixed in position and not raised or lowered, so it wasn't a chafing hazard.

-

If at first you don't succeed ... The main problem I was having is that there is no line connected to the belaying pin to provide a solid point to pull on. You can see this in this video about 1 minute 15 seconds from the start. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=awiFzE5SXzU When the fellow pulls the rope through to make the loop to go over the pin, he is pulling against the rope already tied on the pin. So I decided to start with a loop that will go over the pin first, then make the coil, and end with another loop over the pin. Note: On the tool I used to make the coils the left most pin was mounted on a surface perpendicular to the surface the other two pins were on. See the pictures in this post above: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/19611-albatros-by-dr-pr-mantua-scale-148-revenue-cutter-kitbash-about-1815/?do=findComment&comment=1084631 In this drawing S = short stationary end of the line, L = the long end that is wrapped and tied around things, 1 and 2 = the loops that will go over the belaying pin. The left most pin on the tool is the belaying pin substitute and the right two are used to make the rope coil. A. Pull the rope long end around the two pins on the left. Leave a long loop 1 to the right. B. Loop the long end around the pin on the left (a substitute for the belaying pin). This creates the second loop that will fit over the belaying pin. C. Bring the long end back over the first loop. D. Wrap the long end around loop 1. E. Make a loose knot (don't pull tight yet) between the end of loop 1 and the pin. F. Now start wrapping the loose end around the two right hand posts. G. Make the desired number of loops for the rope coil. H. Compress the loose loops into the coil. I. Bring loop 1 up through the center of the rope coils. J. Bring loop 1 up and over the the middle pin. K. Put a twist in loop 1 and pull it over the left pin. L. Pull loop 1 down above loop 2. M. Pull on the short end S to tighten loop 1 around the post. Put a drop of glue on the base of loop 1 at the middle pin (use one that won't leave a stain of shine on the ropes). N. Remove the coil from the pins and cut off the short end S. Hang it over the belaying pin. Put loop 2 on first, followed by loop 1. Pull the coils down below the pin/fife rail. Here is the result. The two coils on the right were made as described above. The far right coil was a test made with ordinary carpet thread. The middle coil is 0.012 inch (0.3 mm) rope. While loop 2 did work to provide something for loop 1 to pull against, the knot made in step E is pretty obvious. Not perfect! The coil on the left was made without tying the knot (steps D and E). I put a drop of white glue in place of the knot and when it dried I continued with the rope coils. After taking the coils off the pins and trimming the short end S the white glue failed and the end of loop 1 came loose! I glued it back on with some CA gel, but I can see here that I glued it to the wrong side of the coils!! I think the double loop approach has promise. I'll keep working on this to perfect my "technique." I'll try using the CA gel instead of the white glue to "tie the knot" in steps D and E. I think I am really going to enjoy the MSI build - it has almost no rigging!

-

George, Thanks! Note: "Pin loop" means the small twisted loop that fits over the belaying pin. "Coils" refer to the larger multiple loops that make up the bulk of the assembly. I think one problem I had was caused by wrapping the coils "backwards." In the photos I posted I started wrapping with the end that eventually was pulled up for the loop over the belaying pin. As a result the ends of the pin loop pulled up from the bottom end of the coils. That was wrong! I should have started the coils from the end hanging down loose when the coils are belayed to the pin. When this end was pulled up to make the pin loop only the hanging loose end would be shortened to get material for the pin loop and not rope from any of the coils. The real problem is that when you are belaying a real rope on a real pin, one end of the "pin loop" is already secured around the pin, so when you pull it tight it comes up and around the loops in the rope coil. But with the way I did it there is no way to pull the pin loop tight around the rope coils. So it falls apart! I like your idea of securing the first loop in the coil with a knot at the end where the pin loop will be made. The knot will be covered by the other loops. When the pin loop is pulled up the knot will prevent it from pulling rope from any of the coils. It will be a couple of days before I get a chance to implement your method, but thanks for providing it! PS: Happy Mozart's birthday.

-

John, The ropes on your Bluenose look great! The reason I want to make separate rope loops and not try to make the loops in situ is that on this model there are 70 of them. There are too many lines crowding around the pin rails and fife rails to allow the access I need to tie them in place, especially with the sails in the way. It is going to be difficult enough just to tie off all of those lines on the crowded pin rails.

-

I will need a couple dozen rope loops of different sizes to hang on the pin rails after all the lines have been belayed. I read through the topics posted in the Masting Rigging and Sails section of the Forum, and came up with a simple way to make these loops. There were several different methods for making rope loops, but most involved looping some rope around pins, pulling out part of the first loop, and hooking it over another pin with a twist. I used a scrap piece of wood that had been used to test different stains. Straight pins were hammered into holes in a diamond pattern, and then the tops of the pins were cut off. The spacing was designed to make loops that would just touch the deck when hanging from belaying pins. The single pin "around the corner" from the loop pins is for the rope "eye" for the belaying pin to fit over. It is removed when the loop is taken off the fixture. You can see the basic arrangement on the right, and a loop in progress on the left. After the rope loop was completed it was soaked with white glue diluted 1:1 with water. The fixture has five sets of pins to allow "mass production" of the rope loops. The loose end from the first loop that makes the eye for the belaying pin will be trimmed off after the glue sets. The other end is pulled taut by the clamps while the glue sets. Then it is trimmed to about the bottom end of the loop. Here are five loops made with 0.025 inch (0.63 mm) rope (left). On the right they are hanging on pins in a pin rail. These suck! The eye that fits over the belaying pin doesn't wrap under the bundle of rope as it should, and it comes off at an odd angle, and not right at the top of the loops. This causes the loops to hang at an odd angle, and too high. When I tried to pull the loops down to a more natural position the glue failed and they unraveled into a rats nest of lines! It was a waste of good rope! Punt! I am going to have to come up with a better way to make rope loops. If anyone has suggestions I am "all ears." Note: In past builds I have rigged the lines and then belayed them on the belaying pins, with sufficient extra line to loop them and tie them off as it is actually done on real ships. Those loops looked really good.

-

George, If you want to make the pictures smaller just double click on them after they have been placed. You can change the dimensions - be sure to check the box to keep the same X/Y proportions. If you want to place two pictures side by side, make the first one left justified and leave the second one with no justification. If you make a picture left justified you can place text to the right of it. If you use no justification text will start below the picture.

-

Thanks John! One more done. The main sail is the most complex sail. In addition to rigging to the gaff and mast hoops, it also has the main boom rigging to deal with. The sail is "loose footed," and is not laced to the boom. The tack is tied to a ring bolt on the top of the boom jaws. The clew has the sheet rope attached to the cringle. The sheet runs through a sheave at the end of the boom and then forward to where it is stropped to a single block. A double block is tied to a ring bolt on the bottom of the boom jaws. These blocks form a luff tackle for the sheet, with the fall tied to a cleat on the port side of the boom. The boom is supported at the forward end by the boom rest on the mast. The aft end is held in place by the boom sheet tackles. Most drawings show the lower double blocks hooked to eye bolts in the deck. I rigged them to eye bolts on the bulwarks, with the falls tied to cleats (not fully rigged in these photos). If the blocks were hooked to eye bolts on deck the tackle would fall on the tiller when the boom was swung outboard. And if the crew ever did haul cannons back to the stern chase ports the boom tackle would interfere with the cannons. So I rigged the tackles high. There are eye bolts on the deck where the tackle also could be rigged. The gaff is rigged pretty much like the fore gaff. The block sticking up above the aft end of the gaff is for the sheet of the spar gaff topsail. A smaller block is also hanging from the end of the gaff - it is for the flag halliard. I designed the masts, spars and sails in 2D CAD drawings and used the measurements to lay out the sails and calculate the lengths of the rigging ropes. But the proof is in the pudding they say. I was pleased to see that things ended up in their intended places after everything was rigged. In particular, the gaff jaws are riding on the metal sheet on the mast, while the boom jaws are resting on the boom support. And the gaff throat halliard tackle hangs nicely and is not two-blocked. Sometimes the best laid plans do work! There are a number of lines still to be rigged. Port and starboard topping lifts will attach to the end of the boom, then run through single blocks on pendants hanging from the crosstrees, and down to single blocks that are part of a running tackle. The standing parts of the running tackles fasten to eye bolts on deck just aft of the pin rails. The falls belay to pins in the pin rails. Like the fore sail, the vangs have not yet been rigged, nor has the flag halliard. I rigged the gaff sails before the higher sails so the running rigging from the other sails would not be in the way of tying the sails to the mast hoops. But this created another problem. The sails block access to the pin rails from the opposite sides of the ship, and this makes it harder to tie ropes to the pins. It still can be done, for I have belayed the throat and peak halliards of both gaffs to their respective belaying pins. But it wasn't a simple exercise. There are 26 more ropes to be tied to these pin rails, and it will be a test of my patience!

-

Peter, Access to belaying points is a problem! I started by installing the gaff sails (foresail and main sail) because the rigging for all of the higher sails would be in the way of attaching the luffs of the gaff sails to the mast hoops. The standing rigging lines created enough obstacles as it is. However, now that these large sails are in place they block access to the pin rails on the bulwarks! I have a method of looping the lines under the rails and around the base of the pins working from the outboard side of the bulwarks but it is tedious. It would be a lot easier if I had clear access from the opposite side of the ship from the pin rail.

- 222 replies

-

- sultana

- model shipways

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Having done a bit of 3D modelling myself (USS Oklahoma City CLG-5 and modeling parts for other builds) and scratch making things by hand in wood and metal, I say both techniques are equally good for ship modelling. I put in 14 years of research on the CLG CAD model, and I am starting on my seventh year researching my 1:48 topsail schooner model. However, I have doubts about the suitability of the resins used for 3D printing. I have 3D printed some tiny but very detailed parts for my future 1:96 scale model of the CLG - much better detail than I could do by hand in any material. But how long will these resin parts last? 3D printing is relatively new, especially for the home printers. Will the resin deteriorate with time? Only time will tell. I am reminded of the problems that came up when pot metal parts came into fashion more than a century ago. Some of those metal parts corroded and are just dust today. And a very early (1940s) plastic body for a kitchen mixer began to crumble in only a few years. So if your model is just a throw-away, or something that your heirs will have to dispose of, the 3D printed parts are OK. But I have doubts about anything you want to last beyond your lifetime.

- 235 replies

-

Vaddoc, I appreciate the work you are doing to get the angles leading into the rabbet just right. However, I found on my MSI hull that the only really important part was the shape (curve) of the rabbet. The planks curved based on the bulkheads and fit into the rabbet without much trouble. At the bow I just filled the spaces between the bulkheads and faired the filler with the bulkheads. And the way I got the rabbet precisely where I wanted it, and to the right thickness, was to glue keel extension pieces to the sides of the keel, to the top edges of these extension pieces formed the rabbet. I did a little cutting to deepen the rabbet a bit at the bow and on the stern deadwood, but I didn't have to be too careful because it is all hidden under the planking.

-

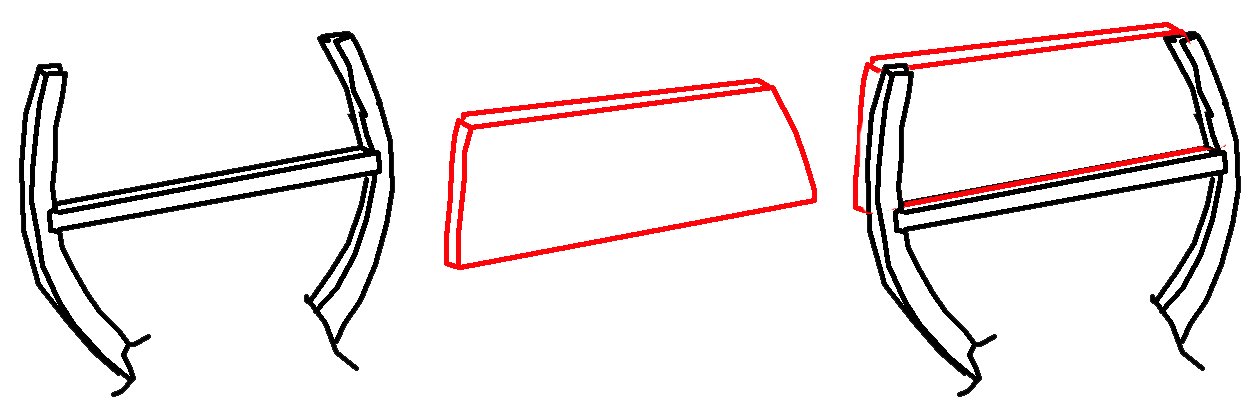

Always glad to see another schooner model coming along. Your design process for making the parts with the laser is an interesting twist to the time tested scroll saw and wood method. It seems you are finding ways to work around the "traditional" problems, but discovering new problems that are inherent to the new method and materials. I assume you are using MDF instead of plywood because it cuts better with the laser? **** One way you can solve the problem of forming the bulwark pieces without breaking the bulkhead extensions would be to cut a new set of pieces that had the outer curves and spacing of the frames and that fit transverse onto the upper deck between the bulkhead extensions. These would be long rectangular pieces with the curves of the bulkheads on the ends. Fasten them to the corresponding upper bulkheads. Because they would be solid material between the bulwark curves they would not break under the forces of forming the bulwarks. Then they and the upper frame parts could be removed. Here is a sketch of the idea. The red piece is the "bulkhead support" shaped to fit across the bulkhead extensions.

-

Duco Cement is fairly fast drying - hold pieces together for 20-30 seconds. It is a nitrocellulose solution in acetone, and the acetone evaporates quickly. It also has a strong smell and is flammable. I use Sig Bond aliphatic resin for most work and clamp the pieces together. It is slow hardening - 40 minutes to hold and over night for full cure. If you need to bond to metal or glass use epoxy!

-

It helps to rough the surface of brass with fine sandpaper or steel wool before painting or blackening. This gives the metal some "tooth" for the paint to grip. But use very fine abrasives so you don't gouge deep scratches in the metal. Use 400 to 600 grit sandpaper or #0000 steel wool. Also, be sure the brass is very clean! Wash it with acetone or rubbing alcohol to remove grease and fingerprints. I sometimes wash with dish detergent and rinse thoroughly before washing with acetone or alcohol - just to be sure. You can also etch the surface with acetic acid (vinegar) or Sparex (sodium bisulfate). Vinegar does a minimal job, and is slow. Warm Sparex does a better job. If you are trying to blacken a large surface etching first will produce a more even coating.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.