-

Posts

2,441 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Salty, Chapelle has a good description of the Lynx in The Search For Speed Under Sail (pages 215-218). There is a full page plan drawing on page 217, and a full page sail plan on page 219. He says the vessel did not have an extreme sail plan. From the drawing I estimate that the rake of the fore mast was 11.5 degrees and the main mast is 13.5 degrees, both relative to the water line.

-

Those hanks on the Star of India are also called "horseshoe hanks" for obvious reason. I have also seen them called "horseshoe shackle hanks" because of the loops at the ends that resemble the bolt eyes on a shackle. I have also heard of a "hank" of yarn. If you stop and think about it the "grommets" (another multiple meaning word) were coiled small stuff (what we called small line in the US Navy) similar to "hanks of yarn or line." So I can see why the later wooden hanks took the name of the earlier coiled line in the grommets, even though grommets weren't called hanks. Or were they at some time or place? Maybe a grommet was a hank that was wound around a stay and tied to a sail? Languages were not designed by intelligent thought. They evolved randomly, and words and phrases were modified by local dialects and legends. And they change with time.

-

Mark, I have no way to know if any other schooner did or did not have the same mast rake as the Prince. As I said earlier, I examined plans and drawings for 17 Baltimore clippers and found the mast rakes to be: Fore mast - 11.5 degrees average, with a range of 7-16 degrees Main mast - 13.75 degree average, with a range of 8-22 degrees So it is certainly possible that other schooners could have had the same rake as the Prince. The angles are close to the average for this type of vessel.

-

Keith, I was thinking of that. I don't recall any flowers on the USS Cape! Instead of a table we had a 0.50 caliber machine gun storage cabinet.

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Glad to help. I have loved schooners since I was a kid and saw Adventures in Paradise on TV. My first scratch build was a schooner, and I enjoy seeing other models being built. I learn something from each one! 7 in 36 = 11 degrees 7.5 in 36 = 11.8 degrees That's better than my measurements from the small illustrations in the books.

-

Howard Chapelle has drawings of the Prince in The History of American Sailing Ships (p147) and The Search for Speed Under Sail (p230). The latter book has drawings showing many details of the Prince's rigging. The fore mast rake was about 12 degrees from the horizontal (waterline) and the main mast rake was about 13.5 degrees. There was some sheer to the deck so the angle from the deck for the fore mast is about 10 degrees and 13 degrees for the main mast. The rake of the masts caused points on the masts higher up to be farther aft. The general rule for rigging was that lines originating higher up were belayed aft of those origination lower down on the masts. The rake of the masts resulted in less "crowding" of the lines as they came down to pin rails on the bulwarks. The lines from higher up came down aft of the mast and caused less interference with the rotation of yards lower down on the mast.

-

I have to disagree about the rake of the masts on Baltimore Clippers. I examined plans and drawings for 17 Baltimore clippers and found the mast rakes to be: Fore mast - 11.5 degrees average, with a range of 7-16 degrees Main mast - 13.75 degree average, with a range of 8-22 degrees I don't recall seeing any that had the same rake for fore and main masts.

-

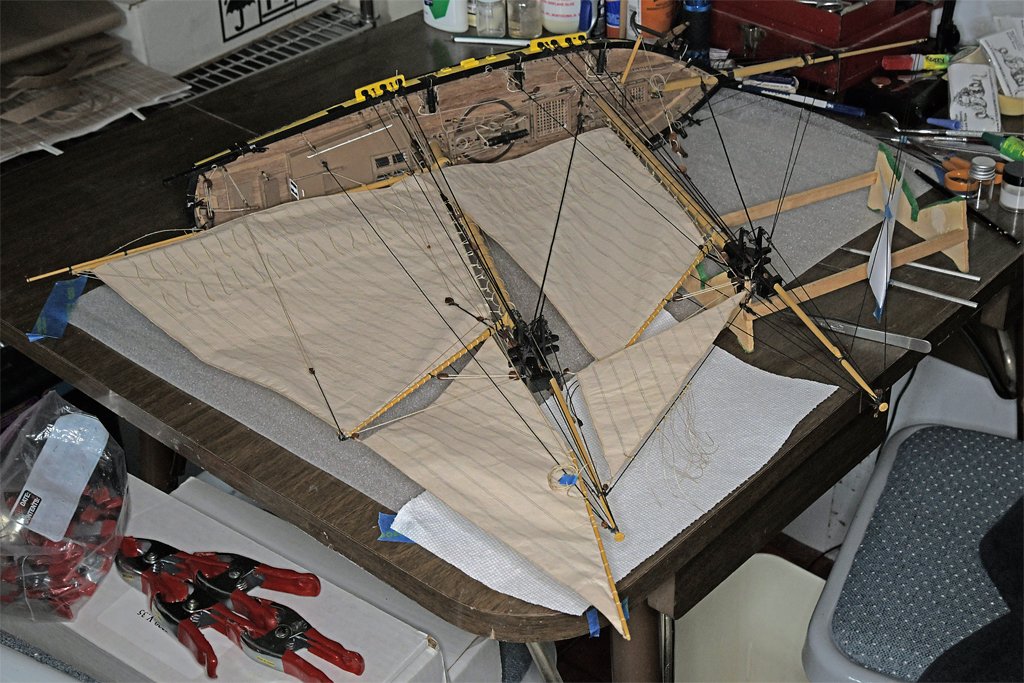

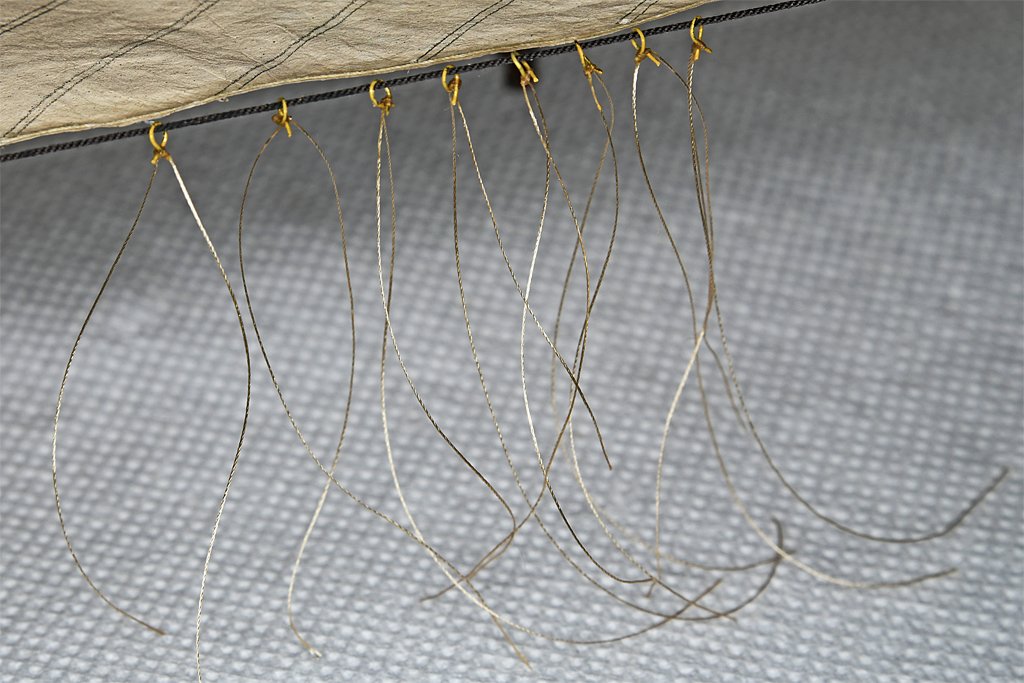

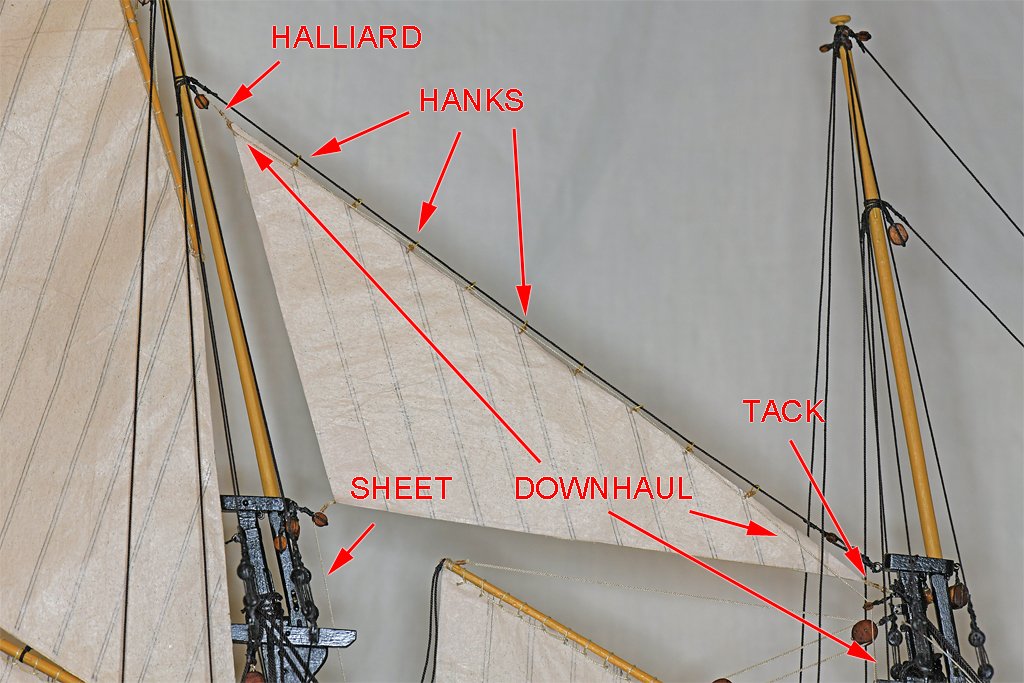

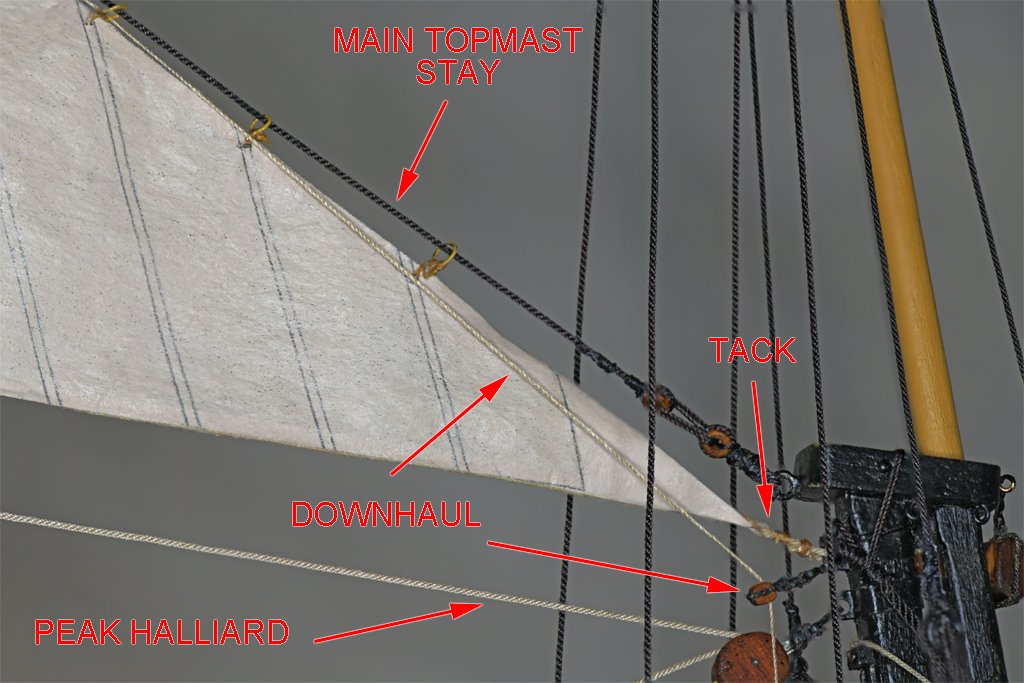

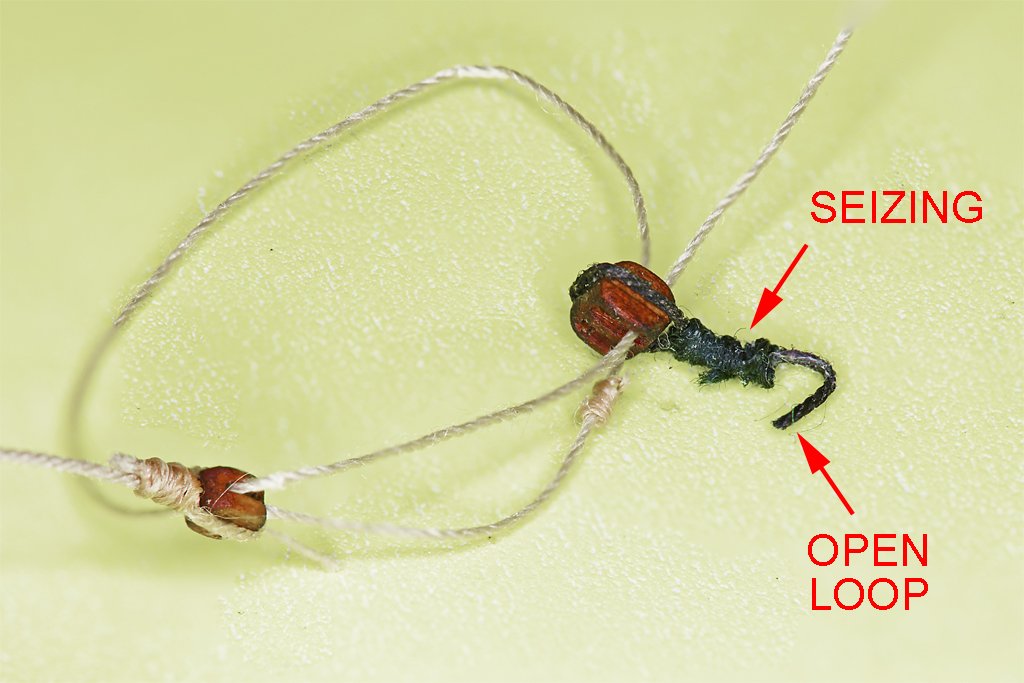

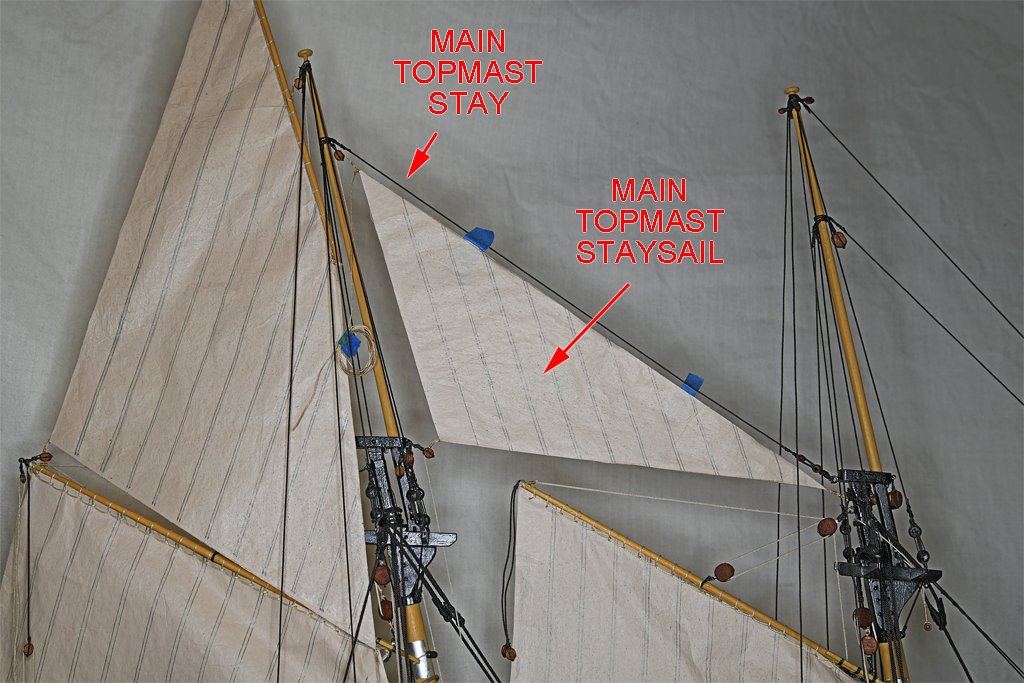

That ^*&@! main sail sheet has been fixed! I have been experimenting with hanks to attach the main topmast staysail to the stay. First I did some research to determine what types of hanks were being used in the early 1800s. I have posted the results of that investigation at this link: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/38044-hanks-for-attaching-staysails-to-stays/?do=findComment&comment=1088102 At the time of my model, about 1815-20, three types of hanks were used, and smaller vessels still laced staysails to stays. I decided that either grommets or wooden hanks would be appropriate for my model. But since I have already rigged the stays putting grommets (three turns of rope around the stay) would be a lot harder that making wooden hanks. I decided to use the wooden hanks. But I think it would be very difficult to work with extremely thin wooden sticks (split bamboo) and get them curved properly. They might want to uncurl, especially when I was trying to tie them in place. So I decided to use 0.012 inch (0.3 mm) brass wire. I used forceps to clamp one end of the wire to a 0.625 inch (1.6 mm) diameter drill bit shank. Then I wrapped the wire around the bit and trimmed off the end, making a "bow tie" shaped loop. These are supposed to be wood so I painted them with the straw color acrylic paint I used on the masts and spars. I really didn't think the paint would stay on while was installing them, but maybe some would. And there is enough remaining on them after they were installed to look something like wood. The first thing I did was lay the ship on its side so the stays would be parallel to the table top. I dreaded trying to fit the hank over a downward angled stay, they try to get it to hold in one place long enough to tie thread around it and then lace the whole thing to the sail. Putting the ship on its side eliminated the problem. The hanks had a gap between the ends wide enough to slip over the stay. Then I closed the gap with forceps. Next I used small (less than 0.006 inch or 0.15 mm) silk thread to tie an overhand knot horizontally across the "X" where the ends crossed and added a small drop of diluted white glue (about 2:1 glue to water). Then the long ends of the thread were looped under the "X" and back through the eye of the hank, and back down again. These ends were then used to tie an overhand knot vertically across the "X". This is actually the way the books show the real hanks being tied. The long ends of the thread were pulled through a small hole in the sail, one from one side and the other in the opposite direction from the other side. The ends were pulled through the hank loop from opposite sides and tied in an overhand knot. Then all of the thread was soaked with the diluted white glue. Here you can see the thread passed around the bolt rope and through the tabling This is important with silkspan sail material, because the thread could easily slice through the silkspan and come loose from the sail. Just as in real sails, it is the bolt ropes that carry the load. I use silk thread for the seizings and other tying. The main advantage is that it goes totally limp with just a drop of water or water based glue. It isn't springy and always trying to unwind. Here is the finished product. The downhaul is tied to the peak cringle on the sail, where the halliard is also attached. The downhaul passes through every third or fourth hank to keep it hanging near the head of the sail along the stay. At the sail tack it passes through a single sheave block and then descends to belay to a pin on the starboard forward pin rail. The sail tack is tied (or hooked) to a ring on a band around the mast head. The downhaul block is also secured to the same ring on the mast band. It actually was pretty easy attaching these hanks to the stay and sail. If you look closely at the photos you will see that some of the paint did chip off of the hanks. But enough remains that the hanks still look something like wood. Four (sails) down and five to go.

-

That's a good use for the anchor davit! We didn't have any lounge chairs on the foc'sle when I was aboard. I'm guessing that you have a motor for the wildcat and windlass. We had to crank it manually to raise the anchor.

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Valeriy, Thanks! I truly appreciate the complement coming from a master modeler like you.

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

CAD file 3D printing question

Dr PR replied to CPDDET's topic in CAD and 3D Modelling/Drafting Plans with Software

Resizing 3D CAD files is easy. Most (all) CAD programs have scaling functions, and I am pretty sure any 3D printing company can do it. You can even do it on you home PC using free software if you are so inclined. Most likely the 3D files contain scaling information for the size the pieces were originally modeled in (1:12). But even if this wasn't available if you know the desired finished size of some piece - such as the helm (steering wheel) - they can resize the file to produce parts of the desired size. There is a catch to resizing 3D print parts. If you go to a smaller size some of the thinner parts may become too small to print. On the other hand making tiny parts larger may result in really clunky and badly proportioned parts. Check the smallest diameter of the original 1:12 pieces you want to print and halve it for 1:24. Then check with the printing company's minimum dimensions requirements. For example, the outer rim of the automobile style steering wheel in your photo looks to be the smallest diameter part in your photo. Be sure it isn't too small to print at 1:24 or 1:27. -

Johann, I have been following this build and am always impressed with the extraordinary detail you manage to put into the model, especially the rigging. I'll have to think a bit about your belaying needle. I have been pretty lucky belaying lines to the pins in the pin rails on the bulwarks of my model, even though the gaff sails block cross hull access and I have to work blind from the outboard side of the pin rails (I do have a dental mirror, but I need a third hand to hold it). But rigging to the fife rails on the center line becomes difficult as more and more lines enclose it in a web of ropes. I need a tool that is designed to give better control in these hard to reach places and your belaying needle, or a variation thereof, may be the answer. Thanks for posting your build, and for the excellent photos that show what and how you have been making it.

-

Steve, I have a number of ship modelling books that all advise against adding sails. They say the sails detract from the model, and hide some of the deck details. I suppose they might if not done correctly (whatever that means), but I really suspect these guys have tried it and know what a hassle it turns into! I'm sure I won't shelve it permanently. I restarted the 30+ year old build because I got tired of looking at the unfinished model. Having only half the sails on it will be even more annoying! But for now I think I will take a break. The Admiral also "suggests" a break (and you know what a "suggestion" from a superior officer means). I think she is annoyed because she thinks I spend more time on the model than with her. Thanks for all the comments and support. But I'm not sure about that Godfather thing! What am I supposed to do, start rigging a new line and make it an offer it can't refuse?

-

Deck Cleats

Dr PR replied to hof00's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

On all the American ship plans I have seen lines with tackles were belayed to eyebolts on deck (near bulkheads or around the base of masts) and the falls were belayed to belaying pins on pin rails on the bulwarks, fife rails around the bases of masts, or to cleats on bulwarks or other places. There are a few other options, but the load bearing parts usually belay to eye bolts. -

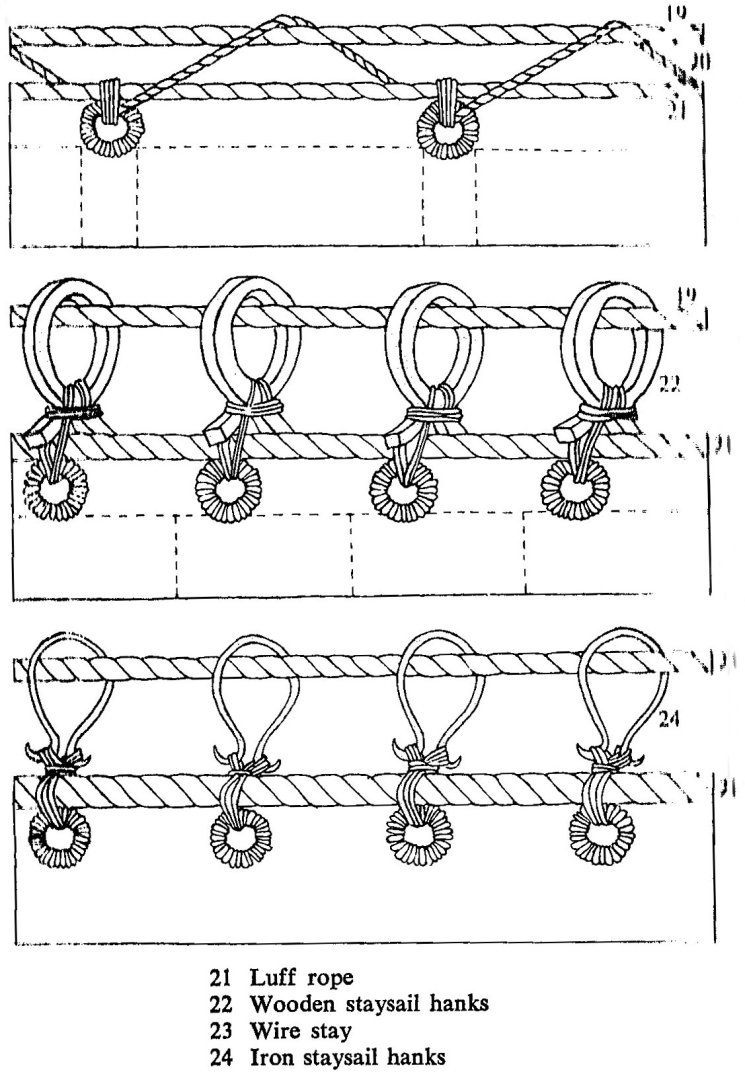

NOTE: Hanks are devices to attach the luff or head of staysails to stays. Some people call the rope coils created when belaying ropes to belaying pins "hanks" but this is a misuse of the term. I am building a topsail schooner model for the period around 1815. I have worked up to rigging the staysails. I have seen a lot of posts on the Forum showing how different modelers have built their models, but nothing that actually considers the different methods for attaching staysails that have appeared with time. I researched the literature I have available and, as usual, found a lot of different opinions. So what should I use for an American topsail schooner (Baltimore Clipper) in the early 1800s? Here is a diagram from Bengt Kihlberg's The Lore of Ships. It shows several methods for attaching staysails to stays. At the top is lacing that is wound in the opposite direction from the lay of the stay. Below that are wooden hanks, showing how they are made, fitted over the stay and tied to the sail. At the bottom are metal hanks showing how they were tied to the sails. Not shown are grommets made of rope to attach the sail to the stay. They were three loops of rope around the stay. I am not sure how they were attached to the sail, but I have seen one instance where the grommet was wrapped around the stay, and then was seized to the sail around the bolt rope similar to what is shown for the wooden hanks. The top two methods are shown using rope stays, and the bottom method is shown with wire stays. But the book doesn't say when each method came into use or for how long it continued to be used. The first place I looked was Howard Chapelle's The Baltimore Clipper and found no mention of how the sails were made or rigged. R. C. Anderson's Seventeenth Century Rigging says "Staysails were laced to their stays with thin lines passed the opposite way to the lay of the rope." Apparently in the 1600s hanks and grommets had not yet come into use and the sails were simply laced to the stays. Falconer's Universal Dictionary of the Marine (1769) describes the following ways to attach staysails to the stays: "GROMMET, ... a sort of small wreath, formed of a strand of rope, and used to fasten the upper edge of a stay-sail to its respective stay, ..." "HANKS, ... certain wooden rings fixed upon the stays of a ship, whereby to confine the stay-sails thereto ..." "They are used in place of grommets, being a later invention ..." " ... framed by the bending of a tough piece of wood into the form of a wreath, and fastened at the two ends by means of notches ..." So grommets were in use in place of the earlier lacing. But by the mid 1700s hanks had come into use to replace the grommets. Steel's The Art of Rigging (1796) says: "GROMMETS. Rings made of worn rope, which are used to confine the nock of spiritsails to the mast ..." "HANKS. Rings made of iron, or hoopsticks bent in a circular form, fixed on the stays to confine the staysails." So grommets were still in use in the late 1700s, but wooden hanks and iron ring hanks were also in use. James Lees' The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War 1625 – 1860 is a popular reference, but he doesn't mention any vessel smaller that large square rigged ships (even though the English had schooners and such). He says "Hanks ... were usually made of iron, bent round to a bow shackle shape, with an eye in each end ..." "Steel ... describes some made of wood ... but I have seen no model with wooden hanks and recommend the modeler to use the metal type." I question his implication that steel hanks were in use in the 1600s. Darcy Lever's The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor (1808) is my normal go-to for early 1800s American rigging. He says "The FORE STAYSAIL ... is bent to Hanks ... made of ash or iron, and sometimes of Rope." He says about the same thing for other stay sails. He actually doesn't give any details for grommets, wooden hanks or iron hanks. Wolfram zu Mondfeld's Historic Ship Models says "The staysails were bent with lacing or grommets until about 1820, after which time metal hanks seized to the sail were used." No mention of wooden hanks! But he implies metal hanks were used from 1820 on. George Biddlecombe's The Art of Rigging (1848) revised Steel's earlier work for the US Naval Academy. It says: "GROMMET. - A kind of ring, or small wreath, formed of a strand of rope, laid thrice round, and used to fasten the upper edge of a sail to its respective stay ..." "HANKS are wooden or iron rings ... They are used in lieu of grommets." He claims grommets were still used in some instances in the mid 1800s, along with wooden and iron hanks. Harold Underhill says in Masting and Rigging the Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier "Stay-sails are bent to their respective stays by means of hanks, or metal rings, which enable the sail to slide freely up and down the stay." But he is mostly concerned with vessels of the late 1800s that used wire ropes extensively for standing rigging and some running rigging. Howard Chapelle gives more specific information in his The American Fishing Schooners 1825-1935. "Wooden jib hank for hemp stays ..." "Horseshoe wrought iron hanks for wire rope …" "Wrought iron jib hanks came into use in fishing schooners when wire rope rigging was adapted, sometime before 1885." "Rings were first employed on all head stays..." "Horseshoe hanks came into use about 1887-9." His dates for the introduction of iron hanks are much later than other references, but he is talking specifically about American east coast fishing schooners. Apparently they adopted the "new technology" later than some navies. **** Do I know any more than when I started researching hanks? Well, yes and no. It would seem that new ideas spread slowly, and old ways of doing things hung on for long times. But that isn't new! To summarize, it would seem that staysails were introduced sometime in the early 1600s, and they were originally laced to the stays. By the mid 1700s staysails were attached to the stays with either rope grommets or wooden hanks. But lacing continued to be used into the early 1800s, and maybe later on very small vessels. By the mid 1800s grommets, wooden hanks and iron hanks were used. When iron hanks were introduced isn't clear, nor is the use of iron hanks and rope stays. But it seems they were used with rope stays on larger vessels before wire rope stays were introduced in the mid 1800s. By the late 1800s wire ropes were replacing hemp and other natural fiber ropes, and the hanks used with metal stays were made of metal. What type of attachments were used seems to depend upon the size and period of the vessel, and consequently the size of the stays and sails. Smaller vessels continued to use lacing and rope grommets into the 1800s and maybe 1900s. Wooden hanks were from the mid 1700s up until wire stays were introduced in the mid 1800s. Metal hanks or rings were used on the largest ships perhaps from the early 1700s on through the end of sailing ships, and probably on all vessels when wire rope stays were introduced. For my American topsail schooner I may use rope hanks or possibly wooden hanks. I think metal hanks would be inappropriate, and the ship is probably too large for simple lacing. References Anderson, R. C. 1955. Seventeenth Century Rigging, Model & Allied Publications Ltd, England. page 133. Biddlecombe, George. 1848. The Art of Rigging. Brattleboro, Vermont, USA: Echo Point Books & Media, LLC. Reprinted 2016. Page 15. Chapelle, Howard. 1968. The Baltimore Clipper, Edward W. Sweetman Company, New York. Chapelle, Howard. 1973. The American Fishing Schooners 1825-1935. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. Page 507-8. Falconer, William. 1769. Universal Dictionary of the Marine. London: T. Cadell. Kihlberg, Bengt et al. 1975. The Lore of Ships, Crescent Books, New York. Page 118. Lees, James. 1990 The Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War 1625 – 1860. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. Page 37. Lever, Darcy. 1808. The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor. Ottawa, Canada: Algrove Publishing Ltd. Reprinted 2000. page 59. Mondfeld, Wolfram zu. 1989. Historic Ship Models. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. Page 266. Steel, David. 1796. The Art of Rigging, His Navigation Warehouse, London. page 10. Underhill, Harold A. 1946, Masting and Rigging the Clipper Ship and Ocean Carrier. Brown, Son and Ferguson, Ltd., Glasgow. Page 13.

-

John, Thanks. Flattery will get you everywhere! I will fix that ^*&@! main sail sheet! But I may recall some sailor talk from when I was in the Navy! I have a shipment of scale lumber on the way to add another layer of planking to the MSI hull. I will probably work on that project for a few weeks, and maybe do a bit of cleanup on the schooner. But the schooner rigging isn't even close to half done, and there will be a LOT of lines belayed on the fife rail at the base of the fore mast! Imagine all the joy in that!

-

I bought some Amati "Single Hole Deadeyes, 2.5 mm (20/pk.) AM4280/25" from Ages of Sail. The measured dimensions were 2.66 mm (0.105 inch) outside diameter, 1.13 mm (0.054 inch) inside diameter, and 1.67 mm (0.066 inch) thick. They have a groove around the outer edge for a rope/thread to fit into. 3/32 = 0.09375 so 0.105 is a bit larger. 1/16 = 0.0625 so 0.054 is a bit smaller. But these dimensions are pretty close to what you want. Here are some photos of these "deadeyes" in use at 1:48 scale. These have been stained darker than the original color.

-

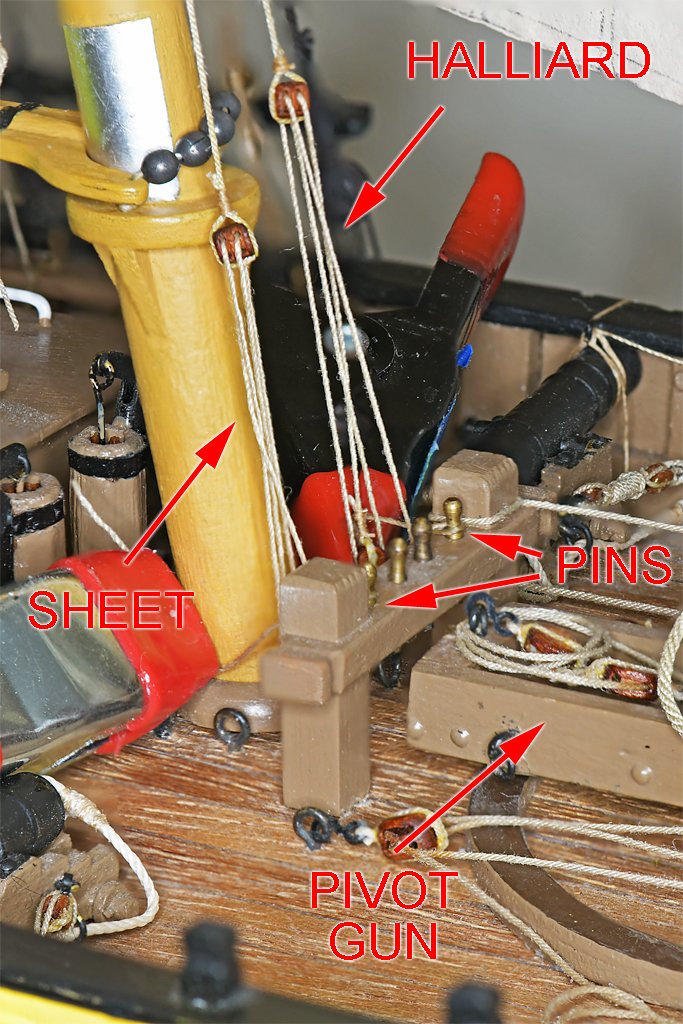

The ship now has a main topmast staysail The tack is tied to a ring on a metal band on the fore mast head. The halliard and stay pass through single blocks on the main mast and descend to belay on a fife rail in front of the main mast. I haven't rigged the downhaul yet (it is coiled beside the main top mast). It will pass through a single block tied to the same loop that the tack is belayed to and then descend to a pin on the fore starboard pin rail. Right now the sail is supported only by the halliard and the tack. I am trying to decide how to tie the sail to the stay. Some people use wooden or metal hanks, but other books say metal hanks were introduced in the mid 1800s when wire rope came into use. Lees says they were used on English ships much earlier than that. And others say only wooden hanks or rope grommets were used with rope stays. I think I will use rope grommets, but haven't made up my mind. This was another trying day! Some place where I have shopped was hacked and my credit card number was stolen. I blocked a couple of illegal purchases last week, but my card was disabled. Then we had snow and ice for a couple of days and the credit union was closed Thursday through Monday. Finally today I got down there and got a new card. When I got home I started rigging the main topmast staysail. And this turned out to be an exasperating exercise! This picture shows the luff tackles for the halliard and sheet. The lower blocks hook to eyebolts in the deck in front of the main mast partners - that was no problem. But the falls from those tackles belay to the outer pins on the fife rail in front of the mast. It took one hour each to fasten those falls to the belaying pins! The area is on the centerline, and there are dozens of stays and lines coming down all around, leaving very little room to get my hands in there. I had to work with two long tweezers and a hook to pull the lines in under the pin rail, loop them around the lower part of the pins, then back up behind the rail, over the top of the pin, and then pull the loose end under the part of the line looped around the pin. For every step the rope kept springing back out of position, sometimes undoing two, three or all steps. So I started over, and over, and over ... When I finally got everything in place I put some white glue on the rope where it crossed over and hooked under the rail. Part of the real problem can be seen where the back part of the pivot gun slide comes very close to the fife rail. I can't belay the line to the front side of the rail because the rope coils would interfere with the motion of the gun! The lines have to be belayed from the back side of the rail. And that is a VERY tight workspace! I still have two more lines to belay to the two center pins on that rail. They are the foremast topsail yard braces, and the yard isn't installed yet. That would have been difficult if the main topmast staysail halliard and sheet were not there. But they are, and they may make belaying the other two lines virtually impossible! I'm pretty sure I will have to figure out a way to belay the braces to the pins before the lines are rigged up to the brace pendants. When I finally got the halliard and sheet belayed I leaned back, took a deep breath, and reached to put a tool back in the box. My hand brushed the trailing edge of the main sail and there was a "pop!" AARRRGGGGGHHHHHH! The double block of the main gaff sail sheet luff tackle pulled loose from an eye bolt on the bottom of the boom jaws! Two steps forward and one step back! The seizing on the rope eye around the eye bolt failed. Again, the white glue failed to hold and allowed the end of the rope to pull through the seizing. This is the same thing that happened to the main gaff topsail sheet block on the end of the gaff. But the eyebolt under the jaws of the boom is in a very crowded, narrow space, with lines all around it. Repairing this will be like working through a spider's web without disturbing the web. It was time to put the build aside and take a muscle relaxer. A double martini took the edge off for a while! This build was a lot of fun up until I started on the sails and their rigging. Every step since then has been tedious, frustrating and very unrewarding. I started the hull in the 1980s and then other things took priority. The unfinished hull sat on the shelf for 35 years until I took up the build again about six years ago. I am thinking I may put it back on the shelf again for another 35 years!

-

Auger, I have a 2D CAD model profile that has all the rigging. From this I can measure the lengths of the lines. However, it isn't perfect! It also takes a bit of guesswork about how much line is used passing through blocks, deadeyes and such, how long the ropes in tackles will be, how much rope will be used in rope coils, etc. So far it has been pretty accurate, but in at least one case so far my guess was about an inch (25.4 mm) short and I had to splice the line. Later I went back and replaced the spliced line with one long enough. Even with my estimations there is a lot of scrap rope in the waste basket!

-

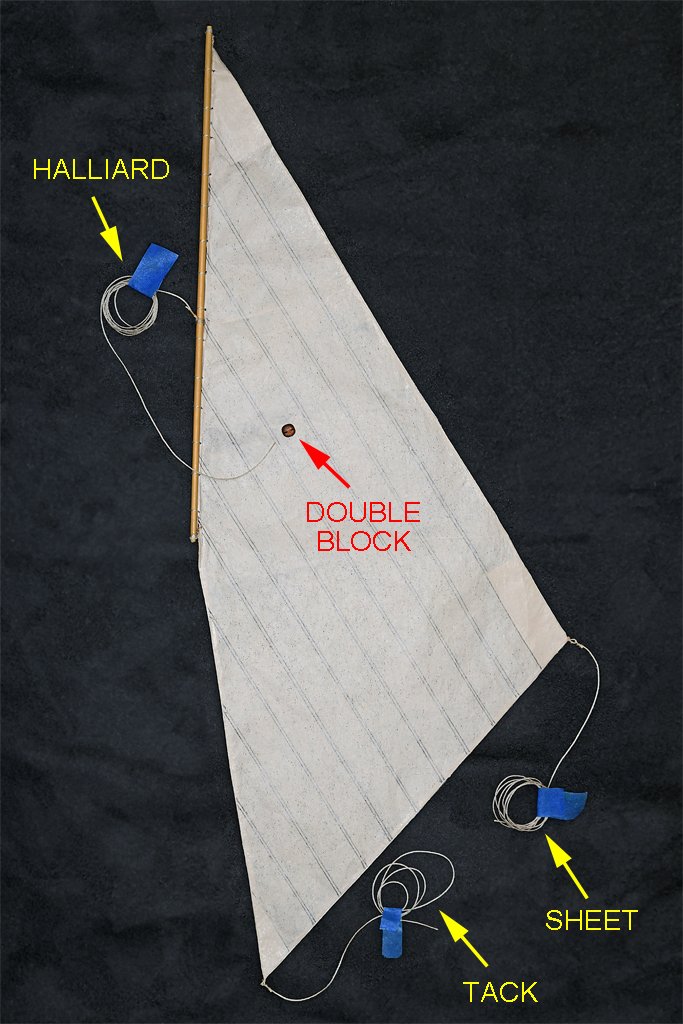

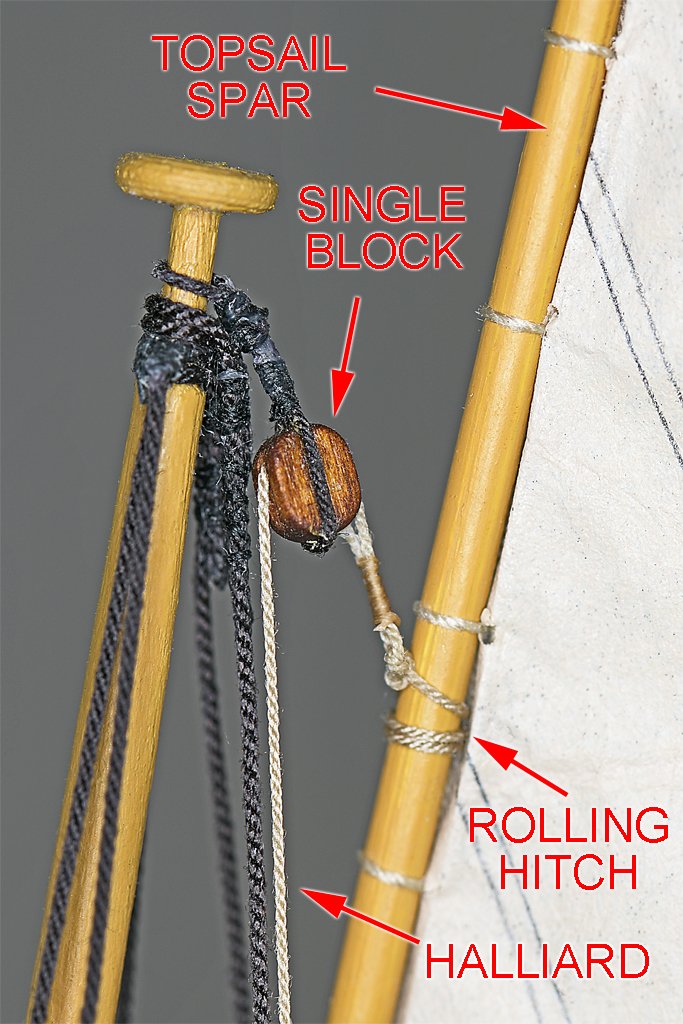

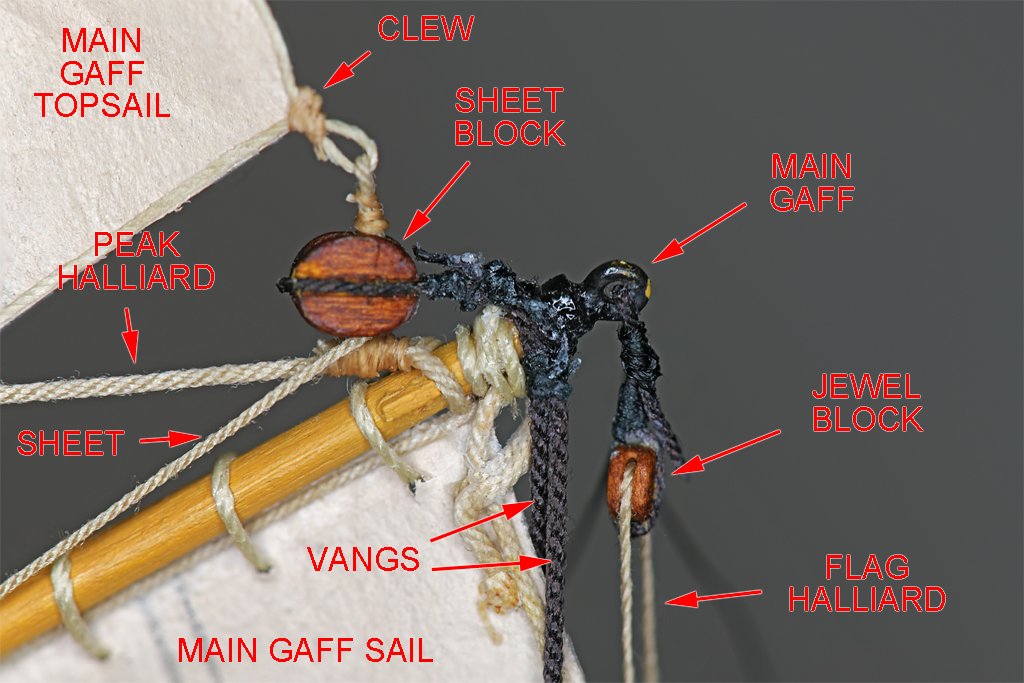

Ever have one of those days when nothing seems to go right? This was one of those days! I have been preparing the main gaff topsail for installation. Lines for the tack and sheet were measured and cut to length, then tied to the cringles at the lower corners of the sail. The halliard posed a special problem. One end of this line was tied to the sail's spar a bit below the center. The other end will be stropped around a double block that is part of a luff tackle that belays to a ring bolt on deck. However the line must pass through a single block at the top of the main topmast. Since neither the sail and spar nor the double block will pass through the sheave hole of the block on the mast I had the fasten one end first, then pass the line through the single block and then attach the other end. And since the single block is already rigged to the mast, all of the work must be done in situ, on the mast. I decided it would be more difficult to tie the halliard to the spar while everything was dangling from the mast top than it would be to strop the other end to the block after the sail was hoisted on the mast. The halliard was tied to the spar with a rolling hitch. I got this idea from Darcy Lever's The Young Sea Officer's Sheet Anchor. This part was pretty easy. Then the halliard was reeved through the single block at the top of the mast and the sail was raised into position. So far, so good. The other end of the halliard was pulled down to deck level and a small clamp was fastened to it to keep tension on the line and pull the sail into position as shown in this picture. The double block of the luff tackle was to be stropped to the lower end of the halliard while the sail was hoisted. Next I ran the sheet line through a single block tied to the end of the gaff and then to another single block tied to an eye bolt on the underside of the gaff jaws. From there the line runs down to belay on a cleat on the main boom. This is where Murphy stepped in. I pulled the sheet through the blocks and down to the boom, but just placed a small clamp on the lower end of the line to put a bit of tension on it. But when I pulled the line taut to haul down the clew of the sail the seizing on the strop of the block at the end of the gaff failed, and the block pulled loose! The strop around the block was still good, but the loop around the end of the gaff had pulled open. So I had to stop rigging the gaff topsail and put the sheet block back on the gaff! I think the diluted white glue that was supposed to hold the seizing for the loop failed to prevent the end of the line from pulling through. The seizing itself just pulled off the end of the line. To prevent this from happening again I pulled the loop closed and placed some super glue (cynaoacrylate) on the lines. When this hardened I wrapped new seizing around the throat of the loop, tied it off, and soaked it in white glue. After all the glue had dried I started to place the loop over the end of the gaff and found I had another problem - this was operator error. The flag halliard had already been rigged through a small "jewel block" tied to a eye at the end of the gaff. There was no way to get the sheet block loop over the end of the gaff! This was poor planning. I really wanted to keep the hardened loop on the sheet block, so I moistened the seizing for the jewel block attachment to the eye and pulled it loose. Then the sheet block loop was pulled over the end of the gaff and more seizing was added to pull it tight around the gaff end. Before putting the jewel block and flag halliard back on the end of the boom I decided to finish rigging the gaff topsail. But Murphy wasn't done for the day! As I pulled the sail sheet through the sheet block at the end of the gaff and the single block under the gaff jaws the rope twisted and a kink hung up in the block. Then I heard a "pop" and the gaff dropped down a bit on the mast! I wasn't pulling hard but apparently it was hard enough to break the plastic hook that attached the lower single block of the gaff throat halliard to the gaff. I have broken several of these hooks while rigging the model, so a while back I made a bunch of metal hooks to be used where more strength was needed. I used one here. Great! Now I had to repair the throat halliard before I could finish rigging the sail!! One step forward, two steps back! This was becoming tedious and frustrating. But as you can see in this picture I did get the throat halliard tackle back in place. And I did get the topsail sheet installed and run down to belay on a cleat on the port side of the boom. The tack was pulled down and belayed on a cleat on the starboard side of the boom. Then I installed the jewel block and flag halliard back on the eye at the end of the gaff. And I did get the double block stropped to the lower end of the topsail halliard. I am waiting for the glue to dry completely before I rig the luff tackle for the halliard. The single block will hook to an eye bolt on deck near the bulwark, and the fall of the tackle will belay on a pin on the port aft pin rail. Over the past week or two I have been tidying up loose ends for lines already belayed to pin rails and fife rails. All of the lines for the main gaff sail, the main gaff and main boom have been belayed, so most of the rigging for the main mast has been completed! This picture shows the schooner as it stands today. But if you look closely you will see several lines with clamps hanging from them to keep the lines taut while glue dries so that rigging can be finished.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.