-

Posts

2,210 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Decal Solution Questions

Dr PR replied to hof00's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

You might try posting the question on model railroading forums. They use a lot of decals on engines and rail cars. I have used a decal wetting/setting solution in the past but I don't remember much about it, and I don't recall any "super strong" versions. I certainly am not an expert with decals! -

Dowmer, Thanks. This build started out to be a theoretical revenue cutter of about 1815, but it seems to be morphing into a similar vessel of the 1820s or 1830s. All the choices do slow things down. I may be slow but that is a good thing because I might be going the wrong direction.

-

I have made a command decision! Although there are a number of inaccuracies and some speculation in this build, I have tried to be accurate where possible. But model ship colors for vessels prior to the mid 1800s are mostly pure guesswork. In some cases there are some published standards or regulations, but mostly it seems, like everything else on ships of earlier periods, things were done as things were done. The colors of masts, spars and tops were not well documented before photography came along, and even then the early black and white photos tell little about colors, just shades of grey. For the early 1800s masts seem to have been wood colored, perhaps with varnish or oil finishes. But some were painted. References like Nelson's orders to paint mast bands the same color as the masts before the Battle of Trafalgar tell us that, but don't say what colors were used for the masts. I have examined many drawings and paintings of schooners in the early to mid 1800s and have found nothing that shows colors. In a very few cases the tops of early 1800s schooners appear to have been painted white. But some tops were dark, and masts were always lighter. It seems to have been the practice in the British Navy to paint tops black (at least some contemporary models have dark or black tops) and many American vessels followed British practice. Later in the mid 1800s white mast tops became common. Perhaps this happened because the British and American navies changed the color of the band on the hull along the gun ports from yellow to white. The ready availability of white paint may have led to it being used elsewhere, such as deck furniture and mast tops. For whatever reason white was normal on these parts after the mid 1800s. I would have preferred white tops because it shows details better. But I would have had to paint the mast bands and eye bolts black. And my model is of an early 1800s vessel, probably before white came into use (it has yellow gun port bands). So I decided to go with black tops. Mast and spar color was another matter. But in reviewing several discussions on the forum I came across a reference to the introduction of straw colored paint sometime in the early to mid 1800s. By the end of that century masts and funnels, and even parts of superstructures, were being painted straw color. Look at the ships of the Great White Fleet. And the straw color has continued to be used throughout the 20th century and even until today on some ships of the US Coast Guard (the Eagle, for example). And since revenue cutters were part of the Revenue Service, the precursor to the Coast Guard, it seemed straw colored masts and spars were appropriate. I have always liked the colors on Coast Guard vessels. So black tops and straw colored spars it is in Phil's Revenue Service! And as was common before any standard colors were defined, I mixed some brown, yellow and white paints to make my own straw color.

-

You are absolutely correct. In photography lighting is the most important part of getting a good photo. I do a lot of outdoor wildflower photography and cloudy bright days are the best because there is a lot of white light (from the clouds) from all directions, not much blue light (from the clear sky), and no harsh shadows. Indoors I try to simulate this with a diffuse white light. Controlling the shadows is key to bringing out textures, curves and such.

-

Valeriy, When you started these boats I assumed they were personnel boats - the captains gig and such. But with the armament, and not a lot of cabin space for personnel, I wonder how these boats were used? Not only are your modelling skills excellent, but your photographic skills are equally good. This allows us to appreciate the quality of your work. Photography is one of my hobbies, so I was wondering what camera and lens you are using to photograph your models?

-

Auto login failure

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in How to use the MSW forum - **NO MODELING CONTENT**

Any further suggestions for getting auto login to work on the forum? Nothing I have tried so far has gotten it to work. -

I have searched through many books looking for guidance for paint colors on ships. So far I haven't found much. Large expensive ships were tricked out with details and colors. Smaller ships, especially merchant vessels, were often pretty drab. As others have said, the colors seem to have been up to the Captain or ship owner. Cost was a factor, as was availability of paints. Black, white, yellow, brown and red seem to have been common in the mid to late 1700s. Some blue and green started appearing in the 1800s. I wonder if the red paint was actually red lead? This was used on exposed wood to prevent rotting. White lead mixed with tallow was an inexpensive way to protect the underwater parts of hulls. Copper sheeting was much more expensive. Brown may have been just the color of oiled or greased wood, especially on the masts of fore-and-aft vessels with mast bands for the sails. In the first quarter of the 1800s white started replacing the yellow on hull exteriors. By the mid 1800s deck furniture, mast heads and other details were painted white. My opinion (and it is just that) is that the modeller can do whatever seems best if there is no specific period information about the colors used on a particular ship at a particular time.

-

Les, First, you need a tight fit into the hole. You need to get a smaller drill bit - 0.39 mm or 0.40 mm. As you noticed, they will drill slightly larger diameter holes than the bit diameter. I usually bend slight curves into the shaft so the part goes in with a press fit. You can use needle nose pliers to push the part into the hole. I have also just used the shaft of drill bits slightly smaller diameter than the hole (1 mm) in the eye. It depends upon how much clearance you have around the place the part is being fitted. I use a needle point to put a small amount of glue into the hole and immediately wipe off any excess. I also wet the shaft of the eye bolt with a small amount of glue before inserting it into the hole. I wouldn't use CA because it will soak into the wood around the hole. This doesn't matter if you are going to paint the wood, but it will prevent stain from soaking in and leave a discoloration around the hole. I use Duco cement, white glue (Elmer's) or PVA. Whatever can be wiped off without staining the wood. Epoxy is even better because if fills the hole with a solid plug that is stronger than the wood. The combination of glue and a tight fit will hold against moderate tension on the rigging - but don't press your luck! Rigging doesn't need to be very tight, just enough to pull it taut.

-

Auto login failure

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in How to use the MSW forum - **NO MODELING CONTENT**

Robert, I can edit the login IDs and passwords for different web sites in Firefox. I found three different login names for Model Ship World and deleted two that I don't recall ever using - or creating. Mark, I do not have "Always use private browsing mode" enabled for "Browsing History." I don't know if there are other "private" modes. -

A while back I was having trouble editing/adding to some of my posts. The recommendation was to clear my browser cookies. Well now I can edit things, BUT ... Auto login no longer works, not only on Model Ship World but also on some other forums. This happens on the first time I try to access the forum after my laptop has been shut down. After that, the auto login works every time until the machine is shut down again (every evening). When I do try to log on I am presented with two name/password options. But when I look at settings only one is shown. Note: I found the problem here. The browser (Firefox) actually had three different logins for Model Ship World - one without a name. I deleted all but the one I normally use. It isn't a big deal, but a bit of a nuisance, especially since it used to log on automatically every time I accessed the forum, even after the machine had been turned off. Note: I do have the "Remember me" option selected in the login dialog. Any suggestions?

-

I had to pipe in on this one. Back in the '50s and '60s I bought all sorts of chemicals in our local drug store and acids (sulfuric and hydrochloric) were available at auto parts stores. I did blow up a few things and burned a few. One day the druggist asked what I was going to do with some of the stuff I was buying. He said my father had told him he wouldn't be surprised to come home someday and find a hole in the side of the house. But our (the kid across the street and me) biggest boondoggle was experiments with rocket fuels for a science fair project. We made a rocket from a 2 inch (5 cm) diameter 18 inch (47 cm) long piece of steel automobile exhaust pipe. It had a machined steel nozzle in the back and a wooden nose plug. The rocket was suspended beneath a long piece of fence wire pulled tight between two trees some distance apart, with a heavy blanket at the far end to stop the rocket. Our experiment was to measure the time of "flight" between the two trees with a stopwatch and rate different rocket fuels accordingly. The fuels we made really weren't very impressive. We tried filling the rocket with home made gunpowder and it just fizzled and sputtered. So we went down to the local sporting goods store to buy some real gunpowder. The fellow said he wasn't allowed to sell gunpowder to minors. But he did sell us cans of shotgun and pistol powder (nitrocellulose soaked with nitroglycerine) - basically plastic explosive in pellet form. We decided to try a quarter load of pistol powder in the "rocket". The other kid's dad lit our home made fuse and ran behind the house. I was watching from a distance. I saw the flash first and then the BANG hit me. Later a kid who lived all the way across town told me he heard the explosion. The rocket nozzle cut an inch deep (2.5 cm) plug out of one tree. We found shrapnel bits all over the neighborhood. We couldn't find the nose piece until we walked the probable trajectory across the street and through a field. It had hit and split a fence post about a city block away. Good thing the post stopped it because it was aimed at a window in a restaurant across the street! Fortunately none of the shrapnel did any damage to nearby houses and no one was hurt. So our science fair project was over when the rocket blew up. But it caused me to have sympathy for the guys at Cape Canaveral who routinely blew up really big rockets back in those days. Kids now days lead dull lives. Only virtual explosions on cell phones.

-

Mark, I have some tiny brass nails with round/domed heads that are 7, 10 and 12 mm long. The diameter of the wire in the 7mm parts is 0.020" (0.5 mm) and the heads are 0.052" diameter (1.3 mm). This is 2.5 inches (6.35 cm) at 1:48 scale. I have been using them to represent round bolt heads on my 1:48 scale build and they look respectable. I have had them for years (pre Internet) and cannot remember where I got them. But it was a hobby shop or mail order shop that carried hobby supplies. Doll house stores might carry them. Some ship model kits come with these tiny brass nails, so you might search through kit manufacturer's web sites. Small nails with domed heads are also called escutcheon pins.

-

Spritsail yards on Niagara and Constitution

Dr PR replied to gak1965's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Some vessels used the spritsail yards as spreaders - similar to how crosstrees and spreaders are used in topmasts to support the shrouds and stays. Jib boom stays were often routed through the ends of the spritsail yards to create a more stable triangular support for the ends of the jib boom. -

Mango, With wood strips you can soak them multiple times. However your bulwarks appear to be plywood Soaking might cause the plys to delaminate. The kinks at the bow gun ports are a problem. The bulwark strip is much weaker at the ports and that causes the kink when the strip is bent. One way to correct this is to place another strip of wood without holes outboard to the bulwark strip. This shouldn't be glued to the bulwarks, but just bent along with the bulwarks and clamped to the bulkhead extensions (the posts inside the bulwark strip). You may also need to clamp the bulwark strip to this outer piece at each side of the gun port to eliminate the kink. You shouldn't have any waviness down the length of the bulwarks. If you do the frames have not been properly faired. Use a long sanding block to shape the outer edges of the bulkheads to remove any materiel that is too "high" (causing outward bulge)s. You can glue thin wood strips to any bulwarks that are too low (causing inward curves in the bulwarks). The normal method to test the fairing of the bulkheads is to use a thin strip of wood what is pinned/clamped to all bulwarks and look down the hull length for waves along the strip. Keep removing or adding material to the bulwarks until this test strip has a smooth (fair) curve along the entire length of the hull.

-

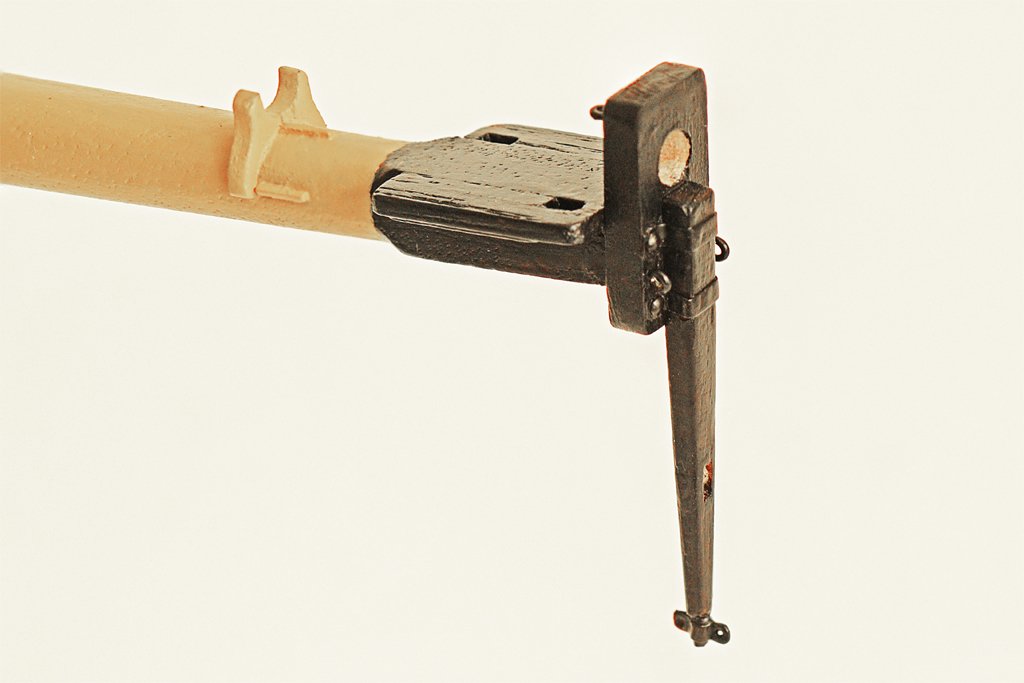

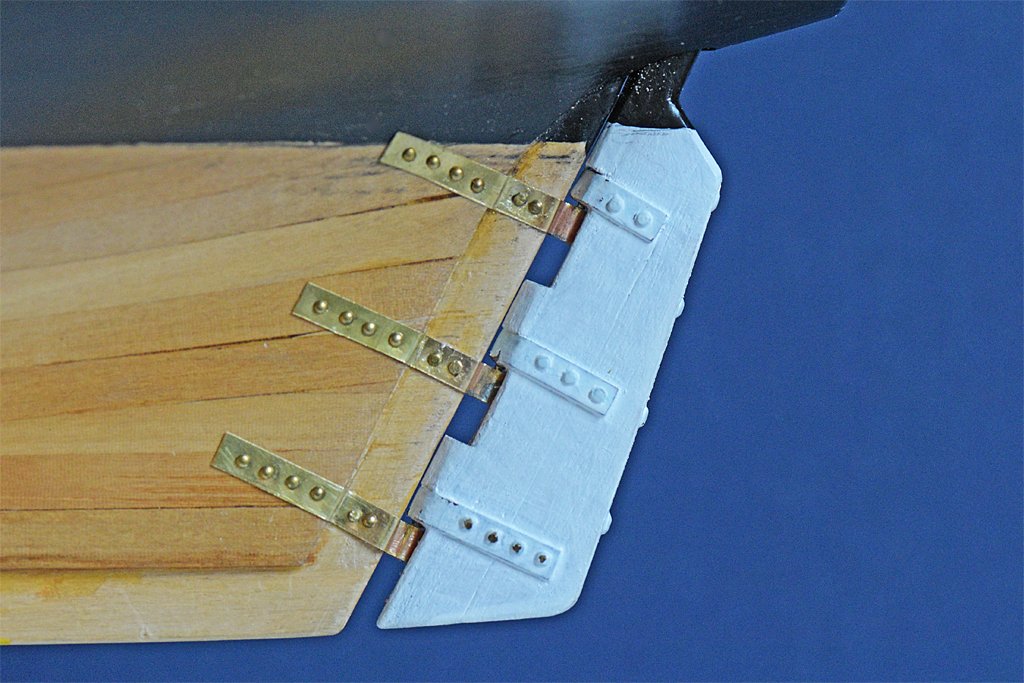

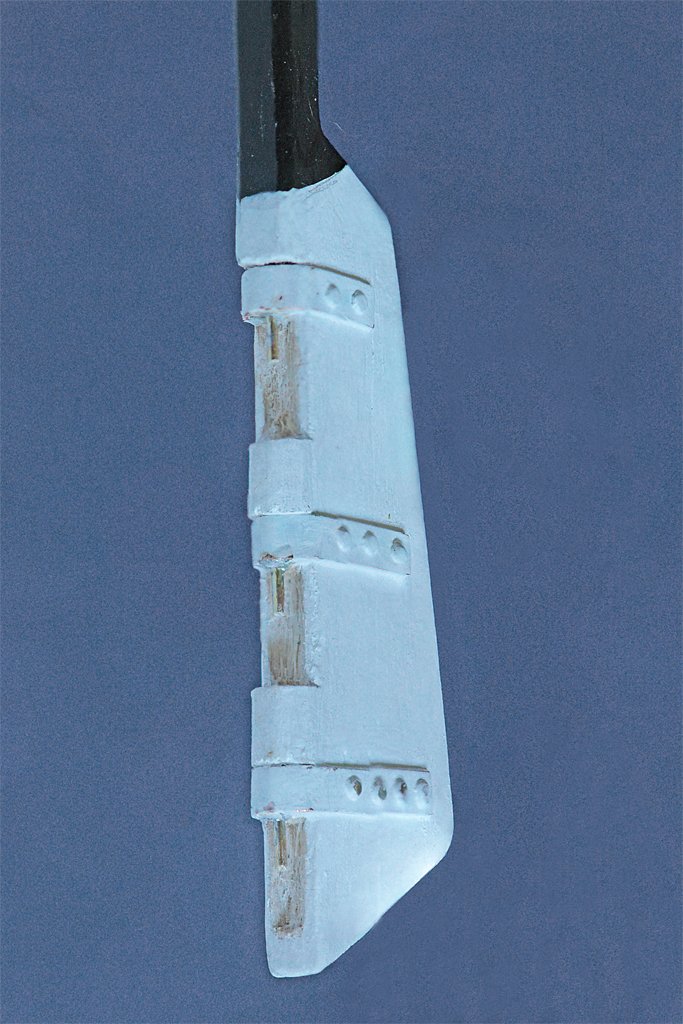

Today I decided to correct a blunder I made earlier on. I swapped the gudgeons and pintles on the rudder! I knew better but got involved with making the pieces and put the pintles on the stern post instead of the rudder! What a lubber's mistake!! I was so embarrassed! Now the pintles are on the rudder where they should be. I also added more appropriate strapping for the gudgeons. Now I can sleep easier knowing that mistake has been corrected!

-

I have been busy with home improvements and a vacation, but finally got around to finishing the mast tops. The mast caps were the same size for both masts, but the square holes were different for the two masts, so I marked them with "M" and "F" so I didn't get them mixed up. Paint will cover this. Marquardt's "Global Schooner" said the caps were bolted to the top of the mast, so I used some 7 mm brass nails to simulate the bolt heads. This ensures the caps are securely attached to the mast top. The main mast cap has three ring bolts on the front. These are for the port and starboard fore topsail yard braces and the main top staysail sheet. The lower forward ring bolts are for the port and starboard fore course yard braces. The after two ring bolts are for the top ropes for raising and lowering the topmast. The brass band with the eye around the mast top is for the main gaff peak halliard. The complete main top shows the bolts that fastened the crosstrees to the mast and the fid that supports the top mast. I set short pieces of hypodermic tubing in the outer ends of the crosstrees for the futtock shrouds to pass through. I suppose I could have just run the lines through notches in the ends of the crosstrees but I worried the wood might split when I tensioned the lines. The mast top has eight battens around the lower part of the mast head. Marquardt said these were often used to prevent chafing of the mast by the stays and shrouds. They are chamfered at the top to make it easier to place the shrouds and stays. Very few models have these pieces but I decided to include them. The fore mast cap has two ringbolts on the forward edge for the port and starboard fore course yard lifts. The lower front ring bolts are for the topping ropes to raise and lower the topmast. The rear pair of ring bolts are for the port and starboard fore course buntlines. The upper brass band with eye is for the main topmast stay. The lower band and eye are for the fore gaff peak halliard. The fore mast top is similar to the main mast top. Not shown is a ring bolt on the aft side set into the mast above the crosstree. This is a fastening point for the lashings used to tighten the main topmast stay. The bottoms of the fore and main topmasts are nearly identical. Small cheeks are attached to the sides of the topmasts to make these narrower masts fit the gap between the trestletrees. The fid holes can be seen, as well as the sheaves for the top ropes. The sheaves were constructed from two small #2 brass flat washers soldered together as described earlier in post #32. I tried a new method of making ring bolts that was described by others on the Forum. Both methods use 0.020" (0,5 mm) 24 American Wire Gauge brass wire. The method I have used for decades is shown on the right. The wire is formed into the ring and the gap is soldered. The new method involved twisting the wire together as shown on the left. I thought this "screw thread" like form would allow glue to fill the hole around the wire and secure the ring bolt in the hole better. However, as the close-up photo on the right shows, the rings are distorted and not flat as they should be. I do not like this! They may be more secure but I think I won't use this method again. The straight wire type shown above can be pulled out if the rigging is tightened too much. In the past I have bent slight kinks in the part that fits into the mounting hole making a tighter fit, and this works OK if you don't over tighten the rigging. The entire topmast assemblies have a coating of shellac to seal the wood grain and cracks between pieces. Now I have to decide what color I am going to paint the mast tops. Most models of American and British ships from the early 1800s have black tops. Black paint was cheap and readily available. By the end of the century mast tops were almost exclusively painted white. Apparently this practice started in the 1830s, but I have found no definitive period description of masthead colors. I prefer white because it shows details better than black.

-

Topsail schooner sail plans and rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

I found this image on line that shows what you are talking about a bit better I do not know how they attach the sail to the ring around the mast. It is possible that they have a line attached to the sail that passes through the ring and down to the deck. There is a line visible in this photo but it could be the halliard. When the sail is hauled down the line would come down with it. The line would loop through the ring and both ends would be belayed on deck when the sail was removed. When they rig the sail on deck the line would be attached to the sail, and could be used to help haul the sail aloft. Once aloft this line could be pulled taut to pull the point on the sail down and close to the ring. But that is just a guess. This is another example of the many variations on rigging found with the fore-and-aft rigs.- 104 replies

-

- schooner rigging

- Topsail schooner

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

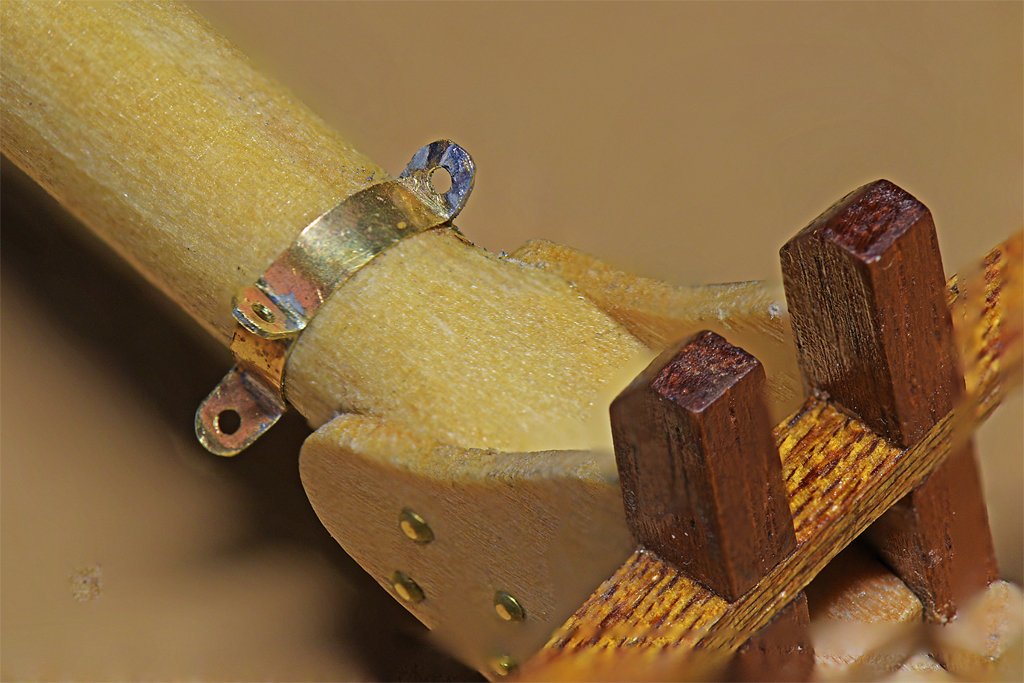

Nice weather and home improvement projects have delayed progress on the model, but 101 F (38 C) temperatures today have confined me to the house. Here is a bit more work on the masts. The topmast shrouds come down to hearts or eyes at the ends of the crosstrees. I haven't decided yet which I will use. The lower eyes/hearts are attached to the futtock shrouds that lead down to a futtock necklace below the cheeks. About 1815 the futtock necklace came into fashion. This was a metal band around the mast below the cheeks - and above the gaff jaws. It had either ring bolts or formed eyes for the futtock shrouds to attach to. I cut a 0.100 inch (2.54 mm) wide strip of 0.005 (0.127 mm) inch thick brass for the bands. I measured the diameter of the mast below the cheeks and selected a drill bit close to this diameter to serve as a jig for forming the band. As I progressed the strip was bent to fit tightly around the drill bit. I started with a simple 0.100 inch (2.54 mm) tab bent at a 90 degree angle from the brass strip. I determined that the two eyes should be 0.200 inch (5 mm) apart around the circumference, so I bent another 90 degree angle in the strip this distance from the first tab. Then I folded the strip over and crimped it with pliers to form a double thickness tab protruding from the band. Next I folded the strip again perpendicular to the tab to continue around the mast. This gave me the first eye formed from the brass strip. I added a drop of liquid solder flux and then soldered the two sides of the tab together. The eyes are not evenly spaced around the mast, but are in a "X" pattern, with two eyes a bit closer together on each side of the mast, with wider spacing between the pairs. I estimated the distance around the mast to the next eye and formed two more tabs protruding at 90 degree angles from the band, spaced 0.200 inch (5 mm) apart, and soldered them. The spacing is a bit tricky, so if you try this don't expect the first attempt to come out perfect. Finally I bent the last tab at 90 degrees from the band, leaving a bit of extra brass strip (this will be cut off later). This part will be soldered to the first tab to complete the circle around the mast. But before placing the part on the mast I drilled holes in each tab for the futtock shrouds to attach to. Then I shaped each tab to a "D" shape. It is easier to do this off the mast. The next step is to place the band around the mast and use forecepts to draw the first and last tabs together, tightening the band around the mast. Then a drop of liquid flux was added to the joint and it was soldered. After this the excess bit of brass strip was cut off, the hole was drilled through the last tab, and it was filed to a "D" shape like the other tabs. I have used this technique for attaching lines to masts for several decades and it produces a very strong attachment point without weakening the mast. This was one of the more difficult bands because it had four tabs that needed to be spaced correctly around the mast. Something similar was used on real ships starting around the mid 19th century. I thought about blackening the band before attaching it to the mast, but decided to not do this. The blackening might interfere with the final solder joint after the band is positioned on the mast. I plan to paint the tops black, and this paint will extend down to and over this band.

-

I have a fine silk thread that I use for serving eyes and such. It has no fuzz. Belding Corticelli size A. It is about 0.0025 inch diameter (0.064 mm). No special reason for using this. It was in my wife's sewing kit.

-

When I am tying knots in things like rat lines where I need to control the length of spans between knots I use this technique: First I tie a knot at one end of the line - and pull it tight. Next I tie the second knot but leave it loose. Then I use a needle or similar thin tool (fid) to move the loop of the knot back and forth along the line until it is in the correct position. Then I pull it tight around the end of the fid and slip the fid out at the last moment. This prevents the knot from wandering as I pull it tight. The third knot (and subsequent knots) are formed the same way. I leave a little excess line past the last knot in case I have to reposition it. If you need to reposition one of the knots you can loosen it with the fid and move it. When you pull it tight again the overall length of the line and positions of the other knots will be the same. After all of the ratlines are finished I apply a suitable glue, paint or shellac to lock everything in place. Then I trim the line ends.

-

deckdog, Almost all topsail schooners have the same proportions of hull shape, beam, length, etc. However, topsail schooners with square sails on the foremast had the widest part of the beam more forward (closer to the fore mast) than pure fore-and-aft rigged schooners. This increased buoyancy forward under the heavier fore mast. The major difference in hulls seems to be the deadrise - the angle between horizontal and the hull surface transversely (side to side). Cargo vessels had a shallow angle giving them a more "U" shaped fuller midships section to increase cargo space. But vessels built for speed, such as slavers, privateers and blockade runners, had a pronounced "V" shape cross section below the waterline. This produced less drag and that increased speed. The proportions for masts and spars were also about the same for a given nation, but American Baltimore clippers of the late 1700s and early 1800s typically had taller masts and larger sail area than their British counterparts. The fore masts were also thicker than the main masts on topsail schooners. However, I think it is a safe bet that no two ships were alike, at least in the Americas, so you have a lot of leeway. You are right about having to rescale deck furnishings and cannons if you are modifying a kit designed for a larger scale. But many kits are assembled with whatever parts the manufacturer had on hand, and often things like cannons and anchors were way out of scale anyway.

- 36 replies

-

- Harvey

- Artesania Latina

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Question about Sails on the Yacht "Westward"

Dr PR replied to Ferrus Manus's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Roger, "Fisherman's staysail" makes sense. Chapelle ("The American Fishing Schooners") shows various lengths of these four-sided sails on many of the east coast fishing vessels, dating back to the late 1700s. Looking through books dealing with schooners from other nations I can't find a single example of this type staysail. Ferrus, Chapelle shows the clews of these sails rigged to the main boom on some vessels, but it appears to be rigged to the main mast or shrouds on some shorter sails. If the clew line of one of the really large sails (like in the Westward photo) was rigged to the deck behind the main mast it would interfere with the outboard movement of the main boom. Attached to the boom I would think it wouldn't require as much handling. But that's just a guess. I have never sailed on one of these vessels. -

The only power tools I have for modelling is a Dremel and a regular electric drill (poor man's lathe). However, there is one thing I really want - but I have to make room for it first. That is a small milling machine - something with very good bearings and little run out (wobble). It would be handy for making jigs and tools for modeling/ But I think the most useful feature is the ability to reposition the work piece for precision distances in a straight line. This would make drilling an accurate series of uniformly spaced holes as in pin rails, fife rails, etc. This is difficult to do by hand, especially with very tiny drills. And a milling machine is designed to be used as a router for making horizontal cuts (drill presses aren't designed for lateral forces, only vertical forces). If you like to work with sheet metal (brass, aluminum, thin steel, etc.) a metal brake is very handy for cutting precise edges and making repeatable bends. It is something that most modelers don't have, so you can get by without it. A soldering iron is very handy for working with brass (photo etch). Good high resolution 3D printers have come down in price to less than $200. These are really good for making complex parts like propellers, anchors, cannons and other small parts with lots of complex curves. BUT you have to be proficient at 3D CAD design and learning a new program can be a huge and frustrating time sink. I am not sure how good the 3D parts will hold up with time.

-

DEVICE TO FINISH ROPE ENDS TO HANG ON BITTS AND BELAY PINS

Dr PR replied to Peter6172's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Some people make the rope coils separately from the actual rigging. You can adjust the rigging all you want, making temporary ties to the belaying points. Then after everything is set you cut off the excess lengths of the rigging lines and attach the rope coils to the belaying points.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.