Bob Cleek

Members-

Posts

3,374 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Bob Cleek

-

There are whaleboats and there are whaleboats, some with carvel planking, some with lapstrake ("clinker") planking, and some with a combination of both, so it's hard to say without looking 1) at the plans, and 2) at the plank, to answer your question. The plans should clearly show the run of the sheer and what that plank should look like. If the one you got in the kit doesn't fit, just spile the plank shape and cut another couple of them from planking stock and you should be good to go. You can read the planking tutorials in the "modeling techniques" section of the forum to learn how to develop plank shapes by spiling if you aren't familiar with the process. It's simple once you see how it's done. Don't give up! You can do it!

-

No, shellac doesn't come in a "matte finish" as far as I know, although there's no reason one couldn't add a bit of rottenstone or pumice to it and make it so. I've heard that's done by some furniture finishers doing French polishing to make it fill grain better. Generally, and we're talking furniture finishing here, the gloss of shellac is "adjusted" by hand-rubbing with pumice and rottenstone, which are very fine abrasive powders. It's a tiring process that takes a lot of "elbow grease," but it produces an amazing beautiful finish with an incredibly smooth, velvety "hand" (i.e. feeling to the touch.) I've done it on lathe-turned handles (where the spinning lathe does most of the work!) and on smaller pieces, such as a trophy I built once. It works with shellac, varnish, or oil-based paints. Another way the gloss is "knocked down" on shellac and other finishes is by rubbing them with fine steel wool (or bronze wool in the marine environment.) For the modeling applications discussed here, the application of three pound (as bought in the can) or thinner (add your own alcohol to cut it) shellac will not leave any gloss at all. In order to be glossy, the shellac coating has to build up some thickness. A single coat or two's application of shellac that's the consistency of water soaks into the wood and does not have any gloss. The same is true if it's applied to rigging line. You have to build up multiple coats before you get anywhere near seeing any gloss from it. Orange shellac has some color to it, but "clear" or "white" shellac is virtually invisible on bare wood or rigging line until you start building up the coats and that's not anything you need to do unless you want to use the shellac to mimic varnished wood itself on the model.

-

No, it's a very good moisture barrier. There's no question that standing water on it will cloud its appearance. That moisture soaks in to a certain degree, but it seems only on the surface of the shellac. It doesn't penetrate into the wood. If left to its own devices, those cloudy rings will disappear when the moisture evaporates, which may take a few days. This problem occurs when it is used as a table top furniture finish. (Ask my wife how I know this! ) On the other hand, I don't anticipate anybody placing a wet cocktail glass on any of my ship models. I wouldn't soak rigging line in shellac, either. I don't see much point in "soaking" rigging in shellac to "seal" it against moisture, and particularly not on cotton line. (Synthetic polymer line shouldn't absorb any moisture at all, in any event.) I use shellac on rigging line as an adhesive to "set' knots in place or stiffen rigging line in order to form it into desired shapes. A thin application of shellac for that works very well. On the other hand, wood and card stock is sealed very well from moisture when a coating of shellac is applied and soaks into it. This I know not only "from the literature," but also from experience. "Bilayer membranes containing non-plasticized shellac exhibit low water vapor permeability (WVP), from 0.89 to 1.03 × 10−11 g m−1 s−1 Pa−1. A high value of contact angle (≈92°) and a low liquid water adsorption rate (26 × 10−3 μL s−1) indicate that these barrier layers have a quite hydrophobic surface." Journal of Membrane Science, Vol. 325, Issue 1, 15 November 2008, pp. 277-283. I have no idea what this really means, but it sure sounds convincing, doesn't it? While, modernly, many full-size boat builders swear by penetrating epoxy (Smith and Co.'s "CPES," or "Clear Penetrating Epoxy Sealer") as a sealer on wood parts, and, indeed it is very useful stuff, laboratory testing demonstrates that epoxy is far more moisture permeable than shellac and shellac is way less expensive than epoxies. This use is as a sealer and nothing more. The wood sealed with shellac is painted or varnished over after the shellac has dried. This application, as with penetrating epoxy, serves to prevent water from soaking into the wood if the surface coating's integrity is breached, typically when it cracks due to seam movement, and the wet wood beneath the finish coating then lifts and peels from the wood, a common problem with traditional varnishes. The advantage of sealing wood in a ship model is that as ambient humidity fluctuates in the model's environment, the wooden parts expand and contract (i.e. "move") to varying degrees (depending upon species and other variables) in different directions (depending on grain orientation, primarily) and this movement, however slight and imperceptible, imposes stresses that can operate to essentially pull the model apart over time. Sealing with shellac won't prevent the phenomenon entirely. Moisture seeking equilibrium is a pretty powerful force of nature, but shellac will serve to slow down the process and protect the model from rapid and extreme environmental fluctuations in ambient humidity and that just makes them last longer before parts start getting loose and things start falling apart. I wish Ab Hoving, retired curator of the Amsterdam Rijksmuseum's ship models, would show up and weigh in on this. I've reached the extreme limits of my knowledge on the subject at this point.

-

Absolutely! I seal wood parts with shellac painted on before and during assembly. I never spray whole models with it! I also use it sparingly to glue knots so they don't come undone and to mold rigging line into desired fixed positions, such as a fall coiled and hung on a beylaying pin. Nothing offends my eye like pinrails with stiff circular coils that look like cowboys' lariats. Real rope coils hang.naturally by gravity. Scale cordage doesn't do that naturally. You have to help it along. I never apply shellac so thickly, or in so many coats, that it shows any glossy sheen, unless, of course, I am using it to represent varnished bright wood on the model. I that case, of course, I knock down the sheen to avoid a high gloss sheen in order to achieve a "scale gloss" appearance. From my reading and first hand experience, shellac is a very effective moisture barrier. I've never heard of, nor seen it "wick moisture." One of its major uses at one time was as spark-proof electrical insulation. It wouldn't be much of an electrical insulating material if it soaked up moisture. Reports are the "wicking moisture" thing was a marketing scam perpetrated by the "wipe on" finish industry. See: http://www.woodworkstuff.net/shellac2.html

-

Not "card models," per se, but it would work fine for them, too. sometimes I have need of a flat panel piece, or perhaps a thin combing somewhere. I use "card" (paper) wetted down with shellac. It can be shaped into curves and becomes stiff and impervious to moisture when the shellac dries. It can then be painted. It would be perfect for paper friezes printed on printer paper. I've had success lightly tacking very thin tissue paper to printer paper with "glue stick" and running the sheet through my printer to print small font letters, like a ship's name, then peeling off the tissue and applying it to the model and shellacking it. You need to test it first, though. Some inks (e.g. felt tipped pens) are alcohol-soluble and shellac will make them dissolve and run.

-

I think wefalck mentioned that he uses orange shellac because that's what's easily available to him. I'd advise using the "clear" shellac, which imparts little or no color. The "orange" appears a bit orange on the first coat and, if coats are built up, darkens to a rich mahogany brown. It's great for finishing wood, if that's the effect you want, but not unless you want that color.

-

I've become more aware of these facts in recent times. The destructive effects of acids in the stagnant atmosphere of ship model cases are well-documented. I've decided to avoid them as much as possible. Perhaps it's time to return to the use of hide glue for model assembly applications? Justin, what do the professional restorers and conservators consider the best archival adhesives for ship modeling applications?

-

In the US, three pound cut Zinsser "Bullseye" Brand shellac can be bought in any paint or hardware store. The "clear" (bleached) version is the most common, actually. The "amber" version (which we used to call "orange shellac") is only found in the stores with a wider selection. (Orange shellac, which enhances the color, is used as a wood finish.) "Natural" (amber) and "bleached flakes are also available. I've read that mixed shellac has a shelf life of about two years. I've never had any "go bad" in the can, but I can't say that I've not ever consumed a can over that long a time. I heartily concur with your comments about shellac. I've been using it for over forty years, to. It's my "go-to" sealer for modeling and other woodworking applications. I always apply shellac to every part of my models except, as appropriate, on rigging line. Shellac is one of best moisture barriers known and limits the movement of wood parts due to changes in ambient humidity. As you mentioned, I also soak various weights of card stock in shellac for modeling purposes. A shellac-impregnated piece of paper costs virtually nothing, is easy to work, and is an archival material of great longevity. It's far preferable to styrene sheet material for similar applications. I also use shellac on "fuzzy" wood species, such as basswood. Once the wood surface is well-shellacked, it can be sanded or rubbed with steel wool to a perfectly smooth, "fuzz-less," surface. The shellac hardens the wood into which it soaks, making it possible to achieve the crisp edges desired on fine work without resorting to more expensive and/or hard to source wood species. Shellac is the only finish available that is totally "green." It's made entirely from renewable resources, is non-toxic, and meets all air quality standards.

-

Yeah, lac bettle crap makes jelly beans shiny. The same is true for M&M's and other candies. You'll just have to get over it. What more can I say? The main ingredients in jelly beans are sugar, food starch, and corn syrup, which combine to give them a soft but chewy texture. Although jelly beans are considered vegetarian because they are not made from animal products, they are not classified as vegan because their outer shells are made from an animal byproduct. Shellac is responsible for providing the exterior that makes jelly beans shiny. It is produced from the secretions of female lac beetles. After the substance is dissolved in alcohol, it is applied to jelly beans and other candies to create a glossy shell that protects the softer middle from melting or sticking to packaging. See: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/91129/jelly-bean-day-fact-jelly-beans-are-made-insect-secretions

-

Interesting discussion. I'm a member of the "avoid CA as much as possible" school of thought. My objections to it are mainly that it's nasty to work with and hard to control in a lot of instances, it invariably gets someplace you don't want it, that often being my fingers, it's quite expensive as far as adhesives go, and it too often kicks off in the bottle, stored in the freezer or not. That said, I do find it convenient for stiffening the ends of rope for threading it through blocks and deadeyes, as well as certain challenging adhesive applications. By the same token, though, I prefer clear acetone-based nail polish for stiffening rigging line points, which is more convenient to use with its brush-in-the-cap feature and low price. I've nothing to add when it comes to CA, but I'm surprised that nobody's mentioned clear shellac for stiffening the ends of rigging line, cementing knots, and for shaping catenaries and coils of cordage. It is easy to apply, it doesn't leave any visible gloss or change color (unless you apply multiple coats of the stuff,) it is alcohol soluble and easily undone if need be, its "archival" and contains no acids, and it's dirt cheap. Heck, it's even edible, if your one who worries about such things. (It's what makes jelly beans shiny.) As the alcohol in a shellac-soaked line begins to evaporate, which can be accelerated by blowing on it, the line becomes progressively less flexible. At that point, it can be shaped in any fashion desired and, once the alcohol is fully evaporated, the line will remain fixed in the position desired. Shellac was once a basic material in ship modeling. It seems to have been forgotten over the decades. it's good stuff.

-

If turnbuckles were used, the stays and shrouds connected to them would certainly be wire cable. The wire cable would be spliced around a solid wire thimble with a hole in the center through which the turnbuckle pin would be fastened. Alternately, the wire cable would have a "poured socket" terminal attached which would match the connection to the turnbuckle. (tongue to fork, pin through hole, etc." These poured terminals would have the wire cable run through them and the wire cable unlaid (this unlaid end was then called the "broom.") Molten zinc, or modernly, epoxy, was then poured into the terminal and, when hardened, would lock the terminal to the cable. These sockets are rather easily made to modeling scale from short lengths of copper tubing filed to shape at the terminal end and filed to a taper at the "neck." These scale terminals can be fastened to the cable the same way the real ones are. Just run the cable through the center of the terminal, unlay a bit of the end of the cable and then pull that down into the socket, and fill the socket with a bit of silver solder, CA adhesive, or epoxy. Types of patent poured socket terminals:

- 337 replies

-

- finished

- mountfleet models

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Lead corrosion is primarily a function of its reaction to acids. Sealed in plastic bags may have provided an anaerobic environment that slowed or prevented entirely the process of the lead turning to lead carbonate. The rest of the process is "above my pay grade," as they say. Just about everything a modeler might want to know about lead corrosion in ship models is in this research paper from the Curator of Navy Ship Models, Naval Sea Systems Command, the office in charge of all the US Navy's hundreds of ship models. It's something anybody building an older kit model should read. https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Home/Warfare-Centers/NSWC-Carderock/Resources/Curator-of-Navy-Ship-Models/Lead-Corrosion-in-Exhibition-Ship-Models/

- 204 replies

-

- marine model company

- charles w morgan

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

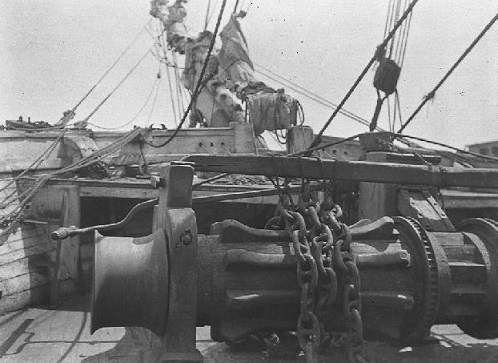

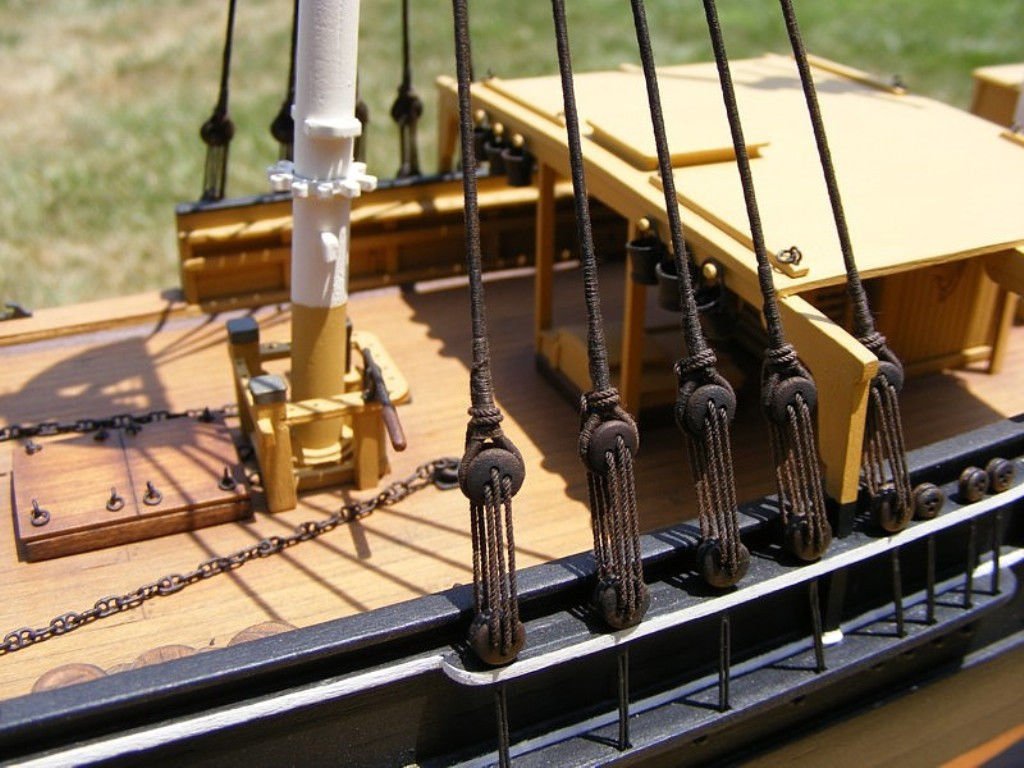

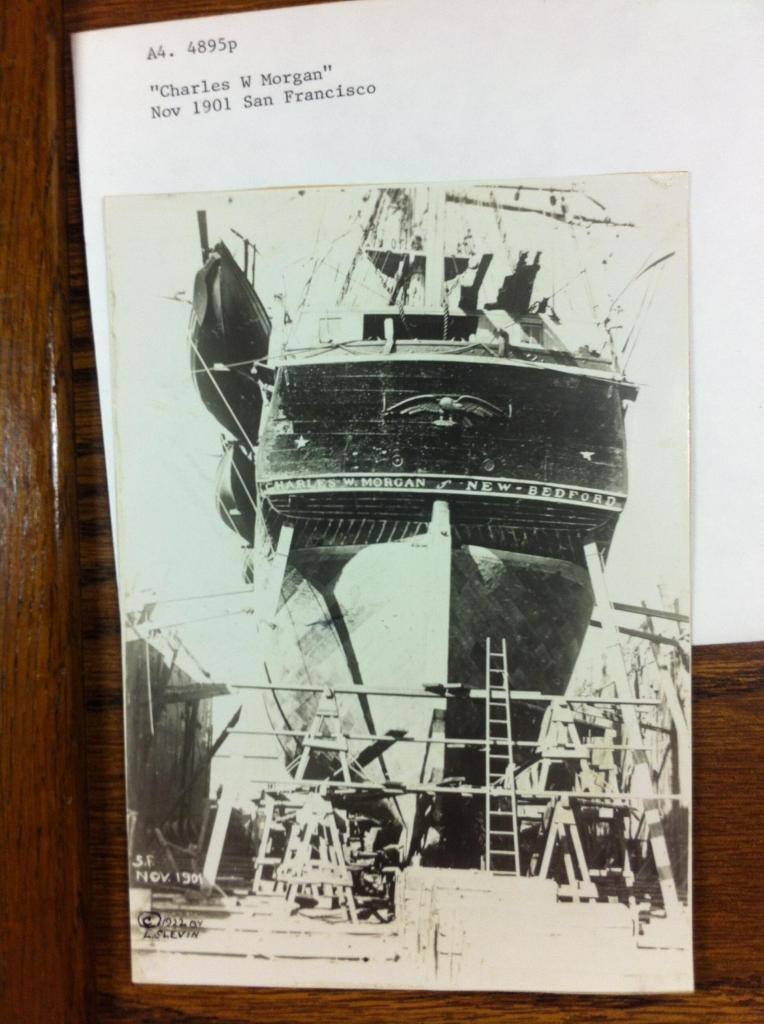

The anchoring chains run aft to chain pipes in the deck aft of and to port and starboard of the mainmast, running into the chain locker below, as pictured in the bottom picture of a model below. (Chain, due to its weight, was commonly stowed amidships so it wouldn't negatively affect the vessel's trim.) I can't say offhand whether the anchor chains were left shackled to the anchors when at sea. It would seem to me that when "off soundings," they would have been stowed below entirely and not left on the windlass or run across the deck. Whalers were floating factories and it doesn't seem that they'd want a couple of lengths of heavy chain running down the decks right across the working space where the whales were being butchered and the blubber cut up for the try works. They'd serve no purpose and just be underfoot. The Morgan would have had stud-link mooring chain, at least for most of her lifespan, not the plain link chain supplied with the kit. (Date of the first below picture unknown.) You may want to replace the kit-supplied chain, if you can find stud-link chain in the proper scale. Making your own at 5/32" scale would be a bit tedious! I've had the Marine Models Company Morgan kit now for over 45 years and I suppose I will get around to building it one of these days, sooner or later. A good practicum of sorts for the Morgan model can be found at https://www.charleswmorganmodel.com/ if you haven't found it already. That one is for the Model Shipways kit. There is also series of YouTube videos by a fellow chronicling his build of the Marine Models Company version we have. I haven't built the model as yet because 1) years ago, I realized I needed to develop my skills before tackling such a complex build and 2) when I developed my skills I realized along the way that this model was hopelessly dated and it would not be possible to build it to my then-established expectations except as a scratch-build, as is my current intention... one of these days. In the interim, I've continued to collect extensive photographic files and related written data on the Morgan, including visiting her and examining her with an eye to modeling her. The Marine Models kit I have is somewhat rare at this point and there are many more common Morgan kits. It's scale at 5/32" to the foot, which is somewhat of an oddball scale that will occasion some inconvenient math to accommodate. That's not a problem once started, though, as my mind "gets in the groove" and I start thinking in that scale. Your post says it's 1/64" to the foot. I'm not familiar with that Marine Models Company version. Are you sure your model isn't 5/32" to the foot scale? Your pictures certainly appear to be that. I'll share a few bits of information of which you may, or may not, be aware. This is an old kit. The plans were drawn in 1939, a couple of years before she came to Mystic Seaport. They were carefully researched and represent the vessel as launched, not as presently configured. Notably, the plans depict her with her original ship rig, not the bark rig she later came to carry. If I remember correctly, there was also an overhead built over the tryworks at some point later in her life. If you are building her to her original 1841 "as launched" configuration as in the Marine Model Co. plans, you'll find some discrepancies in the published Model Shipways practicum which I see from your photos that you are consulting. Whether the stern windows were present at launch and closed up later will require further research. (I think not.) They weren't there in 1901, at least. As an old kit, the standards of quality and accuracy are far below what we aspire to today. Marine Models Co. put out some of the best kits in their day, but kits have come a long way since then. They went out of business in 1970 or so and this kit was last updated in 1957, as I recall from my plans set. Major problem number one: The metal fittings contain lead and will eventually corrode. There's really no cure for this. Paint won't stick to them worth a darn... or at least will be a crap shoot. At worst, they will turn to dust and crumble away to nothing. They all will have to be discarded to avoid the risk of this occurring. That, alone, brings you to "scratch-build level." Sometimes, if the phase of the moon is just right, these lead-based metal fittings do seem to survive to some extent and nobody really knows why, but it's just not worth bothering with them. Once they begin to turn to dust, replacing them is a nightmare because access becomes very difficult in many places on the model. These will have to be rebuilt from scratch or, perhaps, new pieces molded of epoxy or baked Fimo modeling clay, using the originals, if they are suitable, as patterns. Some of the prefabricated parts are crudely fashioned. This is notably so with the rudder casting, which merely has pins cast in the edge and was intended to just be stuck into the stern post. Today, such a rudder on a model of this scale would be made of wood and copper or brass pintels and gudgeons fashioned for hanging it. The kit-provided whaleboats, of cast lead, are of a weight that probably would challenge the strength of the model. Securing the lead cast davits to hold them would be a challenge. Tedious as it may be, the whaleboats really should be made of wood or card stock with their interior details visible. It's details like this that really make the Morgan a special subject. Some research should be done to ensure the whaleboats are correct for the period of Morgan's service that is being depicted. Importantly, whaleboat designs changed over time and didn't last much more than a single voyage. Morgan was launched in 1841. Whaleboats didn't have centerboards until the mid- to late-1850's when the sperm whale was hunted. (The sperm whales were "spook-ier" and they had to be approached silently against the wind so they wouldn't hear or smell the whalers. The centerboard permitted better upwind sailing performance.) Earlier whaleboats were partially clinker-planked, as well. What seems to be the biggest value of the Marine Models Company kit are the hull blank, which is by now well-seasoned and of good quality basswood, and the plans. The plans were drawn by somebody who really knew what they were doing at a time when there were still people alive who had sailed on the vessel and knew her history, perhaps even as far back as the Civil War period when most of the rest of the American whaling fleet was destroyed by the Confederate commerce raiders. Drawn for modeling purposes, they are highly detailed and presumably accurate. Not only is the Morgan still extant, but she's been extensively photographically documented throughout much of her long life and a lot of these photographs are conveniently available on the internet. Mystic Seaport even has "as built" construction plans for her available for purchase (for a price) if one were to want to build a plank on frame model of her. I'm going to watch your build log with great interest. I expect it will be a very rewarding build and a learning experience for me.

- 204 replies

-

- marine model company

- charles w morgan

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Beautiful collection! I particularly like the wall mounted display platforms. Maybe I'm wrong, but I think this forum is for ship models of all kinds (and even models of other things occasionally.) RC models are just another sub-set of models. (And an interesting one, too!) Thanks for sharing your collection! BTW, does "Radio-controlled Barbie" actually really water ski behind that runnabout?

- 27 replies

-

- queen frederica

- cruise ship

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Probably not. The problem is a lack of a data baseline. Model kit sales data doesn't tell us much, given that so many kits are never built for however many reasons. I think the question of model valuation and making any sort of money building and/or restoring models isn't about how many people are building models, and especially kits, but how many are selling models and how much is being paid for them. I'd hazard the guess that many other types of crafts, if not art work, aren't much better compensated than ship model building. As with a lot of "crafts" and "hobbies," making money at it is often a far more sure thing selling the shovels to the miners than striking gold digging for it. If you want to make a living in a gold rush, sell shovels, rather than digging for nuggets. Still and all, that seems to be a tough row to hoe as well from the indications given by some of those MSW forumites who try to make a living at it. Just look at the difficulty of finding milled wood suppliers. They've all gone out of business for one reason or another and nobody's picked up the gauntlet to replace them. I suspect it's because there's more money to be made for less work and hassle flipping burgers at McDonald's or working as a Walmart greeter. But again, the question is this: "Why is a unique, top-quality scratch-built model made of the finest materials which is as historically accurate as possible, in other words, a "masterpiece," not marketable for anything remotely close to what would compensate its builder with reasonable compensation commensurate with the time, skill, and expertise reflected in the finished work? Only the top one percent of the modelers are capable of this level of work and yet nobody wants to pay them a living wage to do that work. The best they can do is to write a book about how they did it or market a kit that makes it look easy for somebody without their skill to build the same model and hope to make something on that. It just doesn't make a lot of sense.

- 27 replies

-

- queen frederica

- cruise ship

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

I don't dispute that it was never a great number of people who did so, but there were once more collectors (as opposed to those of us who build and display our own at home) than there are now. Ship models were once a fairly common "presentation gift" exchanged between gentlemen and heads of state (these sometimes being distinctly different classes ) and were frequently seen in executive offices. John F. Kennedy was a well-known ship model collector and famously presented Nikita Khrushchev with a model of USS Constitution as a state gift. All things considered, this is a rather limited area of endeavor. I'd hardly say there are "plenty of people" involved in it. Unfortunately, being quite familiar with these types of models, few possess the level of detail and complexity of execution that is required to elevate them to the level of "art." Most of the "modern" models of "modern" vessels are as sterile as their prototypes. That said, bespoke models are produced, but, they are relatively far and few between. The cost of doing one well usually exceeds the client's desire to spend what it is worth to compensate the builder adequately. Consider the skills and experience necessary to do the craft work necessary to build any sort of model. In today's marketplace, a worker capable of doing it ought to command at least $100 per hour. Have you checked how much your plumber charges to come and fix a leaking sink lately? I don't know the actual statistics, either, but I'm not so much talking about how many people are building models as I am how interested the marketplace is in sustaining building models as a craft and art. I do know that here in the US, the teaching of any sort of "manual arts" or trade skills in secondary schools, which was once commonplace, has all but ceased to exist. Consequently, few people under the age of forty even know how to hold a hammer. I find myself not infrequently telling adults "lefty loosey, righty tighty" to which they react in amazed enlightenment, having never been apprised of the concept! Well, ship modeling forums never existed before, so their growth can't be taken as an indication of much of anything. This, the preeminent and most popular ship modeling forum on the internet, has 35,359 members as of today. That's 35,359 members in the whole world. Based on the World Population Clock as of this minute (or so,) the membership of this forum represents .000000455516 of the world's population. I was surprised and gratified to learn, through this forum, that there were avid ship modelers in Eastern Europe. I can't say this is because that is anything new, but rather only that our improved international communications systems make it possible to know what others are doing. It would seem that they are "ahead of our curve" in terms of the quality of their work, as well, but I can't be sure of that. Perhaps we are only hearing from the "cream of the crop" in that respect. Who knows? Far be it from me to dissuade them, though. I've learned much from them. As for interest, though, the days when gentlemen came home from a day at work and relaxed by building models are long passed. Television killed that, along with "the art of conversation." Look no farther than the tremendous interest in "model engineering" that once existed in the UK. The Model Engineering expositions that once drew thousands are now a thing of the past. Those of us who are old enough to remember a world without the internet remember when every city neighborhood and village had it's own "hobby shop." In the US, at least, most of us are hard put to find a "brick and mortar" hobby shop anymore. Those that do exist serve a broadbased clientile, addressing all sorts of hobbies from doll house miniatures to radio controlled toy cars. If it were not for internet marketing, we would be unable to source ninety-nine percent of what we require to build ship models today. Most of the small businesses (Syren ship models and Byrnes Model Machines being good examples) would not be able to make a go of it without an internet-based marketing model. Modeling is not alone in this respect, of course. Not as much of a "whole host" as you might think. I have some first-hand experience with the entertainment industry. I live in "Lucas-land" and knew some of those "host of professional model makers" you mention who did the early Star Wars and other movie model-making. Most of the skills they had to offer have been rendered obsolete by "CGI," "computer graphic imaging." The entertainment industry is not about art. It's about profit. CGI is far less expensive, and, frankly, far more advanced, than the old stop-motion-model special effects technology. The movie industry model shops have been a thing of the past for quite some time now. What you see on the screen is not the result of hand-crafted modeling skills, but rather of the magic created by computer geeks who probably don't know the difference between an Xacto knife and a butter knife. No question about it, we have access to a huge amount more information than we ever did before the internet and we have the ability to communicate with others way more than we ever did before. For years and years before the internet, many of us built models without knowing another person who did. That makes the learning curve less steep, but it really doesn't indicate anything about the number of modelers or the state of ship modeling in the world.

- 27 replies

-

- queen frederica

- cruise ship

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

Oh yea, and Mike did a really nice job on it. Dealing with the detail on smaller-scaled steamships isn't easy!

- 27 replies

-

- queen frederica

- cruise ship

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

I'm glad you got the $2,800. I doubt the model, nice as it may be, would bring anything near that. The market for ship models is an interesting phenomenon. Everybody likes looking at them, but few buy them. With very few exceptions, the market demand for models simply doesn't support their production, nor even their conservation. Perhaps this thread is as good a place as any to explore and discuss the reasons for this and what modelers might do to increase the value of their works. It's not that everybody does it only for the money, but as they say, "Money talks and .... walks." I really don't think the art form gets the respect it deserves. I recently had an interesting conversation with a client of mine who has spent a lifetime working in the high-end art gallery business. He was admiring the models in my office and, while he knew little about ships and boats, recognized the quality of the work, commenting that he considered it art. (Such as it was. ) I asked him why there were only a handful of galleries in the US specializing in ship models and, as far as I knew, all of those also sold maritime paintings. His explanation gave me a new understanding of the market for ship models as art. He explained that, generally speaking, wealthy people spend large sums on fine art because it is a way that they can advertise their wealth without being too crass about it and, given that the asset can be expected to appreciate in value over time, do so without cost. As he put it, "They buy art because they can't hang their stock portfolio statements on their living room walls." He went on to explain that it is the buyer's perception of the value of the artwork that sells it as much as it's the attractiveness of the work itself. He noted that he can sell paintings of little or no real artistic value all day long for amazingly high prices if the artist is "known." One of Winston Churchill's paintings recently sold at auction for $2.8 million. That price wasn't about the quality of the painting! My gallery owner friend explained that it's not unusual for a customer (he calls them "clients,") to tell him that they are looking for "something blue" of a particular size that "will go well in the living room" in a particular price range. Only a few more sophisticated collectors will express an interest in a particular artist, style, or period. The key to the price point, however, is about what it says about the purchaser. It's only a small segment of the market who are truly knowledgeable collectors. He also noted that most people don't have the knowledge required to recognize a good ship model from a poor one, himself included. He said, "I can see the work that goes into these and recognize they are good ones, but how good, I have no idea." (And lucky for me. They aren't that good. ) He observed that oil paintings generally command higher prices than other media because people who don't know art seem to perceive oil paintings are somehow "real art" and "the best." One point he made hit home, "Ship models tend to be hard to display, particularly in homes. Everybody's got walls to hang pictures on, but a ship model is often so large that it becomes the focus of a room. Where to put them becomes an interior decorating problem, which is why they aren't very popular with the women." As for galleries, he said that there just wasn't enough of a market for them to justify the overhead of the gallery space. "You can easily fill a gallery with top-end ship models, but if the product doesn't move, you aren't going to be in business very long." It's my own observation that as technology has evolved, the interest in "all things maritime" has waned. There is still a certain cachet in coastal areas. If you have a fancy summer place on Nantucket, you've got to have a gold leafed carved eagle over the front door, a "lighthouse basket," few marine paintings, and a ship model or two... and your interior decorator will make sure you do. That's a pretty small market niche, though, all things considered. There was a time when half the people in some of our largest seaport cities would turn out for the arrival of a new clipper ship or the launch of just about any large vessel. The interest just isn't there like that anymore. Those events have been overshadowed by air shows, NASCAR racing, and football. Our younger folks are glued to a video screen playing interactive games. In a sense, I can hardly blame them when I watch the traffic coming through the Golden Gate. The modern "generic" super tankers, container ships, and monster "high rise hotels laying on their sides" that pass for passenger liners these days really aren't that interesting or beautiful. (In terms of "eye candy," the USN has nothing tdday that can hold a candle to an Iowa class battleship.) I grew up with a father who worked as an accountant in the steamship industry all his life (as did I during summer vacation in the days when your father got you a summer job whether you wanted one or not! ) I can't remember ever not being infatuated with ship models, which were everywhere in San Francisco "back in the day." The Maritime Museum was full of them, as were the lobbies of most of the office buildings in the downtown financial district where my dad worked. Today, we see our maritime museums relegating the world's great collections of ship models to basement storerooms and remote off-site warehouses in order to free up space for "interactive exhibits," because video games contribute more to their admission fee receipts than ship models do. It's no wonder people don't value what they don't know anything about. I believe ship models are truly an art form which has been practiced for as long as mankind has taken to the sea. It's now "threatened," if not "endangered" with extinction. Building kits of the same few vessels over and over again by a few "old pfarts" only prolongs its "last illness," I'm afraid. In the current vernacular, what it seems we need is more effective "outreach." I'm not sure what that looks like. Maybe getting PBS to run a show about ship modeling would generate some interest, like that fuzzy-haired bearded guy's long-running show did for oil painting. Is there anybody "famous" who's into ship models? (How long has it been since we had a President who had a ship model in the Oval Office?) Maybe there's hope in the "Makers' Movement." Who knows? What say ye?

- 27 replies

-

- queen frederica

- cruise ship

-

(and 3 more)

Tagged with:

-

I acquired a copy of William Frederick's (1874) Scale Journey: A Scratchbuilder's Evolutionary Development, by Antonio Mendez C. recently and now note that somebody is presently "remaindering" new copies of this volume on eBay for the paltry sum of $7.50. (And another $3.50 or so for shipping.) In the spirit of full disclosure, I don't have any connection with the seller. I'd not been familiar with this book prior to recently acquiring it, but had heard of its author, a highly-thought-of Mexican ship model builder of long standing, which I'd noticed only upon taking a closer look at it. This book's title is a bit odd. "William Frederick? Never heard of the guy. What kind of models does he make?" As it turns out, "William Frederick" is a three-masted cargo schooner built in 1874, and its "scale journey" is a description of the building of a scale model of her. "Who'd a' thunk it?" It was the word, "scratchbuildler" and the known model-maker author's name that caught my eye. As it turned out, I discovered what was one of the better collections of great modeling techniques and tricks I've come across in a long time. The book is a compendium of a highly experienced and creative modeler's techniques presented in the framework of a description of his scratch-building a highly-detailed radio-controlled sailing model of the William Frederick. It's not a practicum or "how-to-build-it" book, but rather a "how I built it" book. I'm one of those "We know a thing or two because we've seen a thing or two." kind of guys, and I've bought more than a few books on modeling, only to lament that there wasn't anything in them I hadn't seen before. For instance, I must have close to twenty or more books on modeling that contain, to me now, boringly repetitive chapters on "the tools you need to have." I'm sure most MSW forumites have had the same experience. William Frederick's Journey is little different in this respect, as might be expected. What sets it apart, however, is the relatively large number of new, to me at least, approaches to common challenges encountered in building ship models that I haven't seen in other books. Mendez has one of the best collections of ideas I've seen on setting up a building shop and, for example, provides plans for mobile tool carts I found truly inspiring. He's a creative jig-builder and modeling tool-maker who offers many which are useful as he's designed them, or serve as starting points for those with a creative approach to problem-solving. I was particularly impressed with his extensive treatment of "mass production" block-building. He has two or three separate solutions, including a jig for turning out a dozen identical elliptically-shaped blocks at a time on a disk sander. His treatment of block-making is the only one I've seen that acknowledges and addresses different techniques for mass-producing the variously-shaped blocks found at different periods in history. Reading this book gave me a lot of new perspectives on how to deal with the many challenges scratch-building provides. It isn't just for "scratch-builders," though. "Scratch-building" seems to have taken on some sort of mystical aura in recent times. To me, it's simply the logical progression of the hobby for anyone who stays with it any length of time. Most modelers quickly "outgrow" the usual run of kits, with a few exceptions (e.g. Syren kits,) and necessarily evolve into "scratch-builders." It starts with buying aftermarket blocks and rigging line and before they know it, their making their own and "it's downhill all the way" after that. This book will make you a better kit builder as well as a better scratch-builder, which, in my book, at least, are inevitably one and the same thing. Other books are fancier and have more full-page color pictures and drawings and diagrams which may be more sophisticated. Others still may have more extensive treatments of rigging schedules, spar dimensions, and so on (and which duplicate information so many authors of these books seem to employ as "padding.") I'm sure most modelers have come to realize there's no single modeling book that covers it all. This one is no different. The simple fact is, though, that this one has a lot that no others have, much more, in fact, that others don't have than I've ever seen in a single book before. In that respect, it's a gem. It's definitely worth buying for $7.50. I'm sure it was priced much higher when it was published in 2005. 266 pages, hardcover, tons of illustrations, and an index. It just might change for the better how you think about modeling. Priced at less than a snort at the corner pub, you can't go wrong grabbing a copy. https://www.ebay.com/itm/William-Fredericks-Scale-Journey-Scratchbuilders-Development-Model-Ships/202632143331?_trkparms=ispr%3D1&hash=item2f2dd121e3:g:w~0AAMXQqBxRGwHl&enc=AQAEAAACQBPxNw%2BVj6nta7CKEs3N0qX2rUt1kMWu04v79%2BQt6%2Fc5KwGGM2txm5wMkabdZRx99zBYT8W7%2BtRzhRxwYTIE7OCqlqcg9LShIsVtAkben0OX7PIzBw7IWBQJIPgBH%2F9GJztvrQUZsGeX7YaNgrqwJwb%2F0Igwsj6z6dOPXMnvTmUeuuXaS8npjn0omAzUhV%2B0b6krrYbwEU43DuP5g5rlIwurD6RCJf1xZRNCklWUW6%2FUbNd3zWO5rE0Ae9hmyVAXGREqWj1HIRTsEqxhH4aHEZ%2BMyS%2Bf32edQrTd8ORY2flRO1lQDow9tcaJYSFMNspy%2B3%2FBq83imiaLsHrv7b%2FfcU5W5muzOygMHUakhfJzHqmhxXTuR0u0Wnhhzdl%2FhV5et4cJxRrqag9hFct2Y%2BeXXcsPf34%2BHZjrnw9w362Vlaqyaja%2FwPc%2Fk4aEWe6NZzXAbo1CaEf9jzB6Zf347lBZztpOiCoFEFYd9SUpiSv8nbZLPieLNtvAbw9BX0NARs0EHugOFI2N6%2FxR5Q4TVYWdDldvhm5Us911jIZ15GwXV%2FyoWlCqJirr91qPiZaTioDhx5VtlqQtzQIRSLtXwNQQEg7NII%2FHjJbNntl2kSp5cpAQCRvZ85hmFOR9vRjPsVlPEsZfFa9YpkAValb0uJABcCFKB98QTN0WQC%2BSCvg9fM2m2PzNJIbAK1pqdd06U23IYgB3fUhKdUHSt5l6tcnns0QHtiTb6o43wZjtVYI2DQshpGka3jInlkf%2FeJpVxA5Vlw%3D%3D&checksum=202632143331e891b87235dc49a8a55d59d9b9e0867e Also see: https://www.amazon.com/s?k=William+Frederick’s+(1874)+Scale+Journey%3A+A+Scratchbuilder’s+Evolutionary+Development&i=stripbooks&ref=nb_sb_noss_2

-

Painting a BB-63 Missouri

Bob Cleek replied to Rubi's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Given USS Missouri's long span of service, you may want to give some thought to the time at which she is portrayed by the model. That would determine the proper paint colors. I can't say whether Tamaya's indicated colors are historically accurate or not. As the saying goes, "there are many shades of grey." At some times, vertical surfaces were painted in one shade of grey, while horizontal surfaces were painted in another shade of grey. While the practice changed after the Pearl Harbor attack, until that time, the tops of the turrets of USN battleships were painted red, white, blue, black, and yellow with the colors of the multiple turrets on each ship following a code which served to identify which ship it was and which squadron to which it belonged for the purpose of identification from the air. USS Missouri was launched after this practice ceased, but the regulation colors and paint schemes of USN vessels changed continually during the many years of USS Missouri's active duty span. Certainly, her "shades of grey" changed significantly between her launch in 1944 and her service in the Gulf War! This link may give some helpful information: https://www.shipcamouflage.com/development_of_naval_camouflage.htm -

Properly rigging this model is not a big deal. All it takes is a bit of research. The rig is pretty much generic. A build log would be a good way to get lots of input on correcting the rig errors. My concern would be that following the kit rigging plan will be frustrating because the inaccuracies will likely make it difficult to rig in the first place.

-

I quite agree with your assessment that the sail plan looks oversized. That said, note that Chapman shows two, or perhaps three, shrouds, no running backstays, and places the gaff jaws properly below the hounds. The model plans are clearly in error and not an accurate portrayal of Chapman's drawings. This kit is going to take some research and substantial "bashing" to get it corrected. Par for the course with a lot of kits, but, IMHO, these are pretty glaring discrepancies.

-

The rig in the later drawing above is more detailed. I see there is a shroud and a running backstay and the throat halyard tackle is pictured. As a period yacht, it is what we modernly call a "character boat." It's a reduced-scale pleasure boat version of a larger vessel, something for people who want to make believe they are sailing a bigger boat. In and of itself, a square topsail on a boat of that size wouldn't be all that practical and inefficient. It would reqiure to much work to set and manage in return for the motive power it provides. On the other hand, character boats can be a lot of fun and that's the whole point of a yacht. I didn't check Chapman to see what the source plans were, but I suspect that Chapman may only have provided the hull, but not the rig, which was a later interpretation of the kit designer.

-

The species of wood used in a model is chosen not only for work-ability, but also for appearance. Pear, ebony, and boxwood were used on the well-known Admiralty Board models of the 18th Century and much of the wood on those models was left "bright" (a natural finish, rather than painted) because the purpose of the Admiralty Board models was in part to depict the construction methods to be used in building the prototype. Building a model today with the wood left bright is a stylistic thing of the moment, indeed something of a fad, though not in the bad sense of the term. Basically, it's a duplication of one's interpretation of the Admiralty Board model style. It requires exotic species that offer the trifecta of great physical properties, relative ease of working, and beauty, which comes at a very high price. It also demands the highest skill to yield the desired result. From the standpoint of "historical accuracy," in real life, with the exception of decks and perhaps spars, there was very little bare wood on vessels. Wood was painted to preserve it. (Decks were left bare to provide good footing.) Even bare decks quickly became black with pine tar tracked all over them. Admiralty Board models primarily showed how a vessel was to be built, not how it was actually going to look. There are very few actual contemporary Admiralty Board models in existence. In fact, the majority of the "masterpiece" models in our museums are painted and, the appearance of the wood thus being of no matter, are built of species of wood other than the rare, exotic, and expensive. These models are built in a different style, emphasizing not the construction details of the prototypes, but rather their appearance. There are very few kits which are intended to produce a true Admiralty Style model. Certainly, no kits which are double planked do. There's no denying the impressive craftsmanship and beauty of an Admiralty Board style model done well, but other, more realistic appearing styles are every bit as worthy of appreciation. Those who have not yet attained the pinnacle of skill and experience it takes to build one are better advised to develop their skill and experience "doing the common thing uncommonly well" in less demanding styles than to produce faux impressions of "the Old Masters."There's little point in hacking up expensive, exotic finish species unless one can really do them justice. "Historically accurate," well-done beautiful models finished with paint (and even faired with putty ) are far easier for the vast majority of us to create and enjoy while developing our craft skills painting Picassos until we get to the point where we can realistically attempt a Rembrandt. As Dirty Harry said, "A man's got to know his limitations."

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.