-

Posts

3,064 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Cathead

-

That's a wonderful model. Nicely balances clean workmanship with artistic attractiveness. I hope you have a proud place to display it.

-

Your wooden kit progression - go big, or keep learning/practicing?

Cathead replied to Esap's topic in Wood ship model kits

Not all wooden ships have PE. I'm one of those who hates working with metal, and there's a fair argument that I just haven't learned how to do it properly. But I think the broader point here is that starting small and/or dabbling also lets people learn what they're good at or not, and what they like to do or not. I've learned over and over that I'm happiest working in wood, and that's helped me focus (for the most part) on projects I'll enjoy. There's a fair counter-argument that learning new skills helps keep the hobby fresh, but it's still worth learning/knowing your strengths and weaknesses. -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

Jack, all the wood is Eastern Red Cedar, which we harvest and mill on-farm. Its sapwood has that brilliant purple hue when it's freshly cut, but it quickly weathers to the dull orange you see on most of the structure, and eventually to grey with sufficient direct sunlight. You can preserve some of the color with wood oil, for example in this table I built from the same material (photo repeated from earlier in the thread): Paul, beans would be an option but we'd rather plant a perennial vine that will take up long-term residence, rather than something we'd have to restart every year. That'll also speed up the shade production, since an established vine will create shade as soon as it leafs out, rather than waiting for a new vine to climb up the trellis again. And we don't want to do grapes because we don't want to draw lots of birds into a food-handling area. We have plenty of garden space and trellises for beans (we grow our own full annual supply of dried beans as well as green beans). So it'll be something hardy and flowering. -

Timber-framed outdoor kitchen - Cathead - 1:1 scale

Cathead replied to Cathead's topic in Non-ship/categorised builds

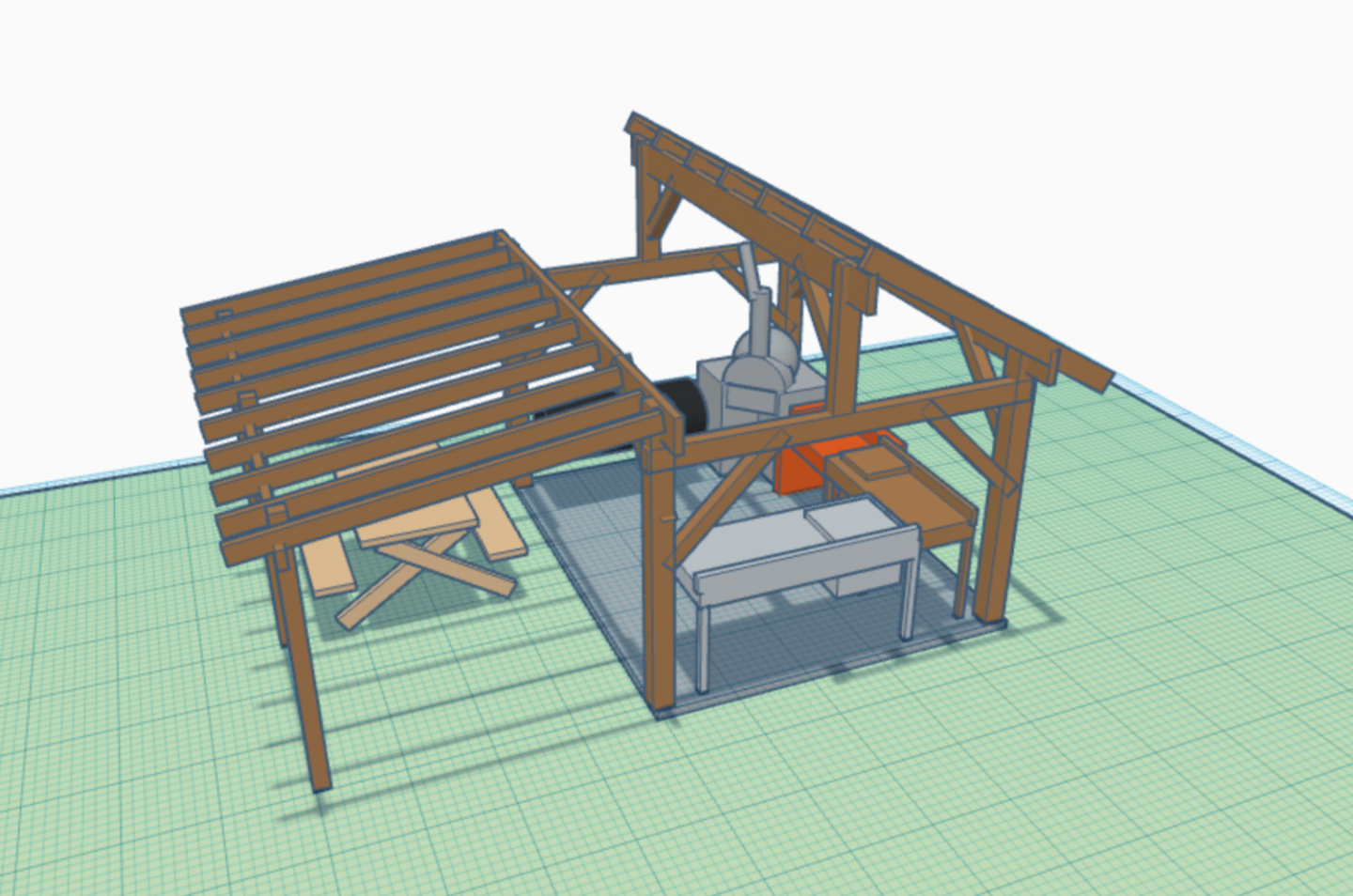

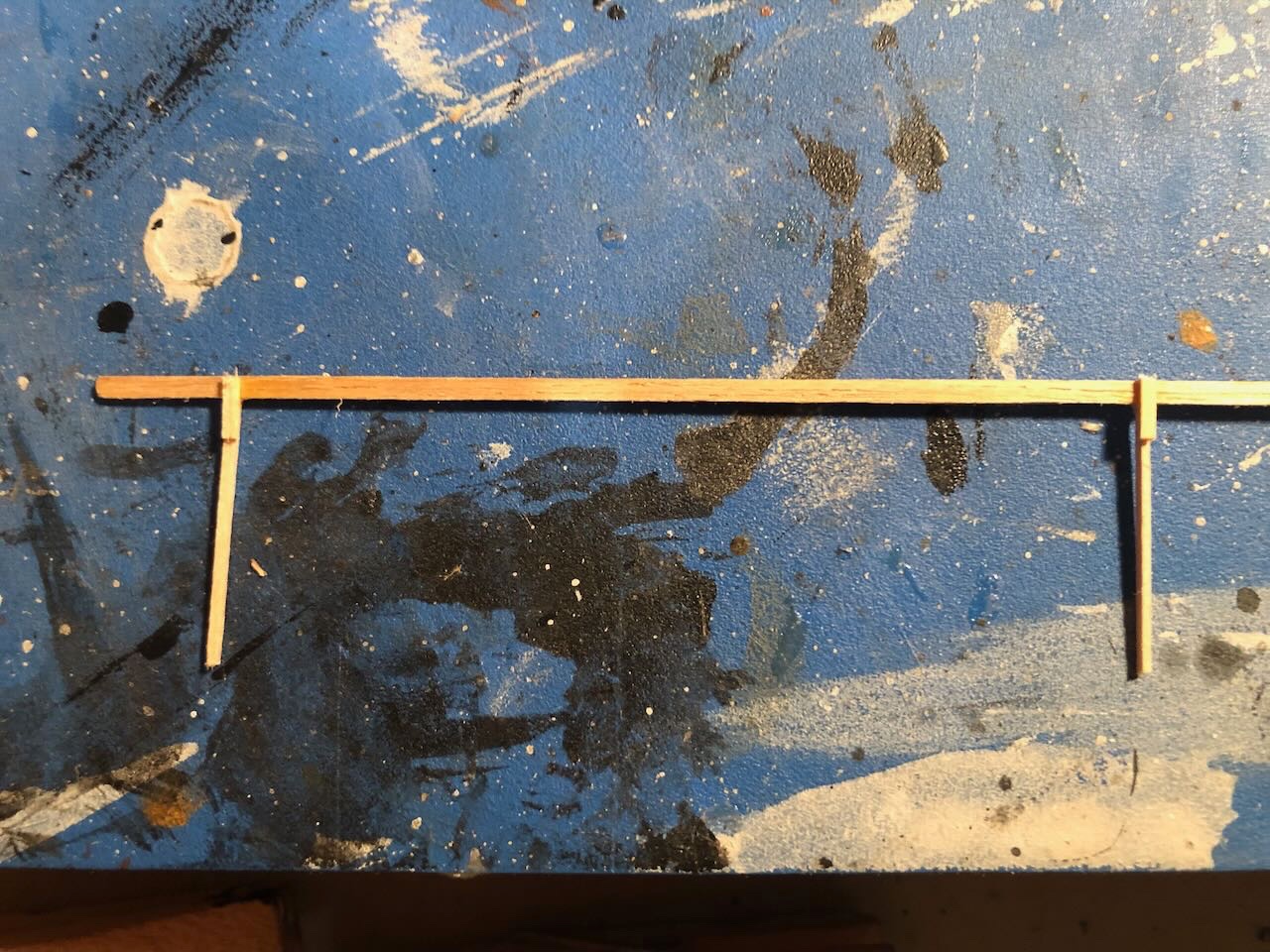

I took advantage of a few warm days last weekend to add an arbor off the west side of the structure. As a reminder, here's the original digital model showing one theoretical approach to this. I ended up using far fewer rafters/beams as the goal is just to grow and train some shady vines up onto it. Step one was to set up the two outer corner posts. I built a mock-up using braces to make sure I got my dimensions, design, and post locations right. The plan was to set the two posts using a metal bracket that pounds into the ground, avoiding the need for any post-hole drilling or other foundation work. I've used these before for light-duty construction, they're great. Image below from Lowes: I notched both the posts and the cross-beam so they'd fit tightly together and make the joint stronger and more symmetrical: And here's the main frame erected and temporarily braced for stability: I added a couple angle braces for extra stability: I then measured, notched, and cut each of the six rafters individually, as the structure isn't perfectly square. Here are the outer two installed; I did these first to stabilize the structure: And here's the final version with all six rafters: It'll be fun to get the vines growing this spring, hopefully we can get some nice shade there on the western side to keep the summer sun from blazing in to the main kitchen late in the afternoon. -

Your wooden kit progression - go big, or keep learning/practicing?

Cathead replied to Esap's topic in Wood ship model kits

The advice to "buy ahead", getting a kit you might be interested in someday so you have it on hand as inspiration, comes with a caveat. Hobbies move forward and develop, and if you wait too long, you may end up with an outdated kit. Model ship kit design has progressed amazingly in the last decade, at least among the more conscientious, forward-thinking manufacturers, to the point that older kits can feel impossibly clunky in comparison (poor materials, poor instructions, etc.). This is similar to other hobbies like model railroading. If you come back to that now, after dabbling in, say, the '90s, you probably won't want your old '90s trains from their dusty box in the closet, because their quality is so much worse and the options available now are so much better in every respect (except one, which I'm about to get to). People also change. You may be sure now that you want to build a USS Constitution someday, but after a couple years in the hobby working your way up, you may develop a fascination with steamboats or aircraft carriers or Chinese fishing boats, and you'll want that money and shelf space back. Or, as Roger suggested, you may end up diving into scratchbuilding and never going back to kits. The caveat here is price. Kits go up in price just like everything else over time, and you may well be better off buying something now for ten years later, IF you're sure it's something you'll want and build ten years from now. If not, if it just ends up on a shelf destined for eBay or the dumpster someday, it may not be worth it. Don't make your kids clean out your closet full of unbuilt kits. So my strong advice is that, at whatever rate you progress, go one model at a time, whether it's a big jump or a little one. What helped me most in my progression wasn't necessarily developing physical skills, as important as that was, but rather developing a mental understanding of the history and engineering of vessel design. My first scratchbuilt steamboat model was terrible (at least below the main deck) because I had no idea how hulls worked and hadn't tried to understand (just plowed ahead ignorant), so just made it like a barge. After that, I took a deep dive into the history of steamboat development and design, and once I actually understood the vessels, was able to make much better models. The same was true for other projects: even doing a basic Viking ship kit, I took the time to research and understand how and why these ships were built, which let me apply and develop skills toward improving that kit. Building a revenue cutter, I worked to understand rigging and was able to make significant improvements to the kit's rigging plan. The bonus is that I value each project more when I understand it, and it isn't just a shallow display piece. To again use model railroading as an example, even more important than physical modeling skill is an intellectual understanding of how railroads work. If you can design a layout that will "feel" real and represent realistic railroad operations (whether complex or simple), and if you understand which equipment goes together, you'll likely enjoy the hobby more than just running trains in a circle, no matter how good your scenery and weathering are. So to summarize this long-winded post, in my opinion the most important skill to develop is intellectual curiosity, and that should be applied one project at a time to allow for a flexible future and a minimum of waste. -

Well done, such a beautiful and crisp model.

- 72 replies

-

- Glad Tidings

- Model Shipways

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

One more resource for getting one's head around how river tows work: the PBS series "Rivers of Life" has episodes on the Mississippi and Yukon Rivers, both of which feature towboat operations. The Yukon one is especially fascinating given the distinct challenges of navigating that river. Overall I found the series a little simplistic for my taste, but they do have some nice footage of working/navigating along the rivers. https://www.pbs.org/show/rivers-life/ If you're not a PBS member for streaming, you might be able to get DVDs through a library. Otherwise, great to see the build underway. Envious of your workspace setup, I'm still operating out of a small portable tray as we haven't been able to move forward on renovating the spare room that's intended for my workshop long-term.

-

Kurt or Roger may correct me, but as I recall, in the steamboat era, steamboats started towing extra rafts or other simple vessels behind them to carry more goods. This was very unwieldy and difficult to control, so as riverboat designs evolved, the extra barges shifted to the front of the vessels, but the phrase "tow" and "towboat" stuck around. In other words, there was a slow evolution from the powered river vessel being the primary means of carrying cargo (classical steamboat) to the powered vessel towing some of the cargo in independent loads, to the powered vessel being adapted to push those separate loads (the beginning of the modern towboat), to the powered vessel becoming nothing BUT the power source (more like a railroad locomotive) for independent barges. But the original terminology never changed. Just like how we still "dial" phones.

-

Who you callin' elderly? I'm 42! Jokes aside, so glad this was useful to you, and good luck with the project!

- 29 replies

-

- ships lifeboat

- model shipways

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Mark, I agree. It’s long befuddled me why kit makers almost completely ignore river craft. A towboat or steamboat isn’t any more obscure than some of the centuries-old sailing vessels that get churned out. Canoeing on the Missouri River last year, we passed a rare tow and it was cool to see it up close and experience just how powerful those engines are; the effects of its wake lasted a long way downriver as they reverberated from bank to bank. Anyway, rambling way to cheer on this choice of model by someone who will do it justice.

-

That's as good a motto for this hobby as any! Nice progress.

- 86 replies

-

- king of the mississippi

- artesania latina

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

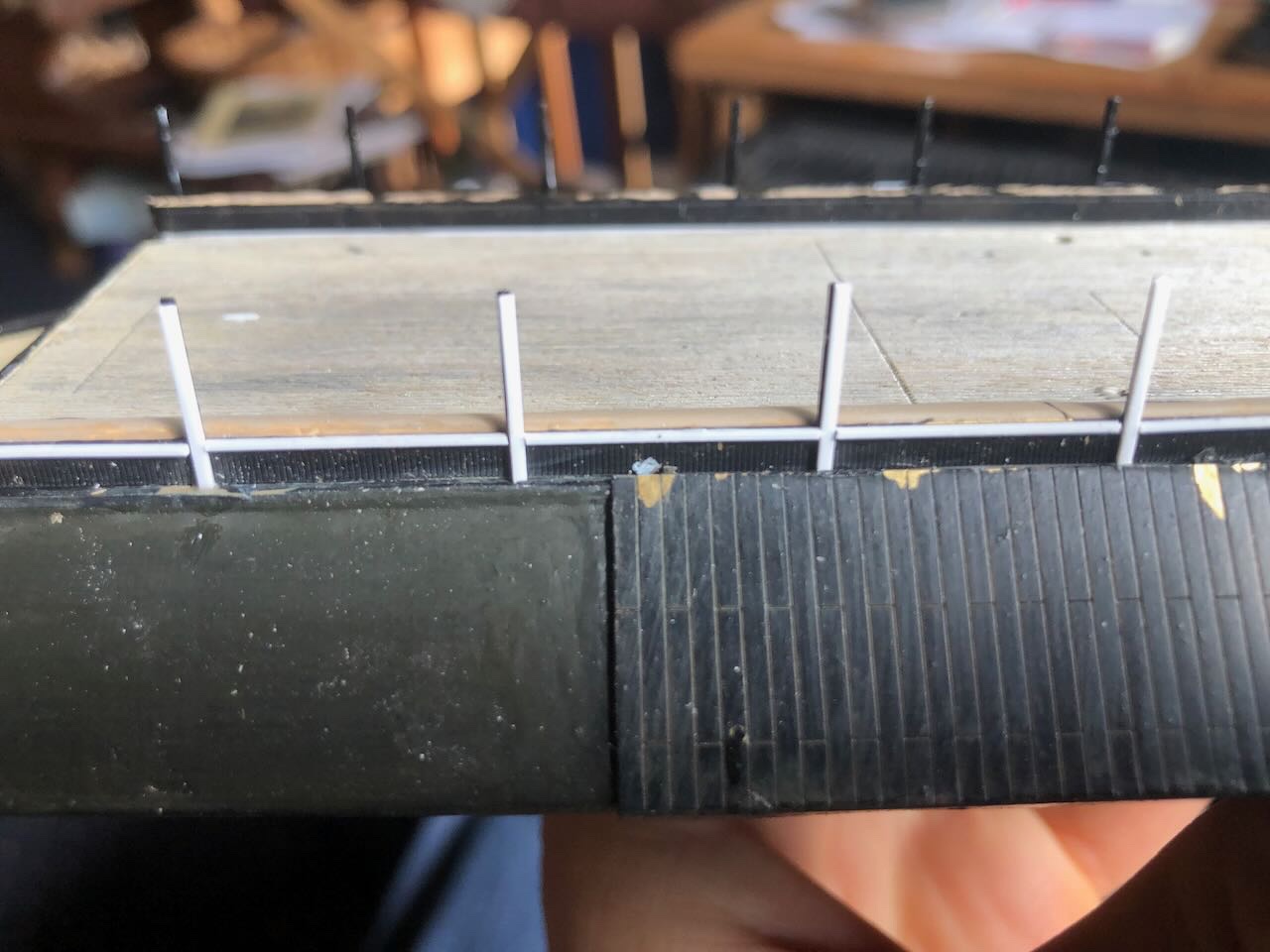

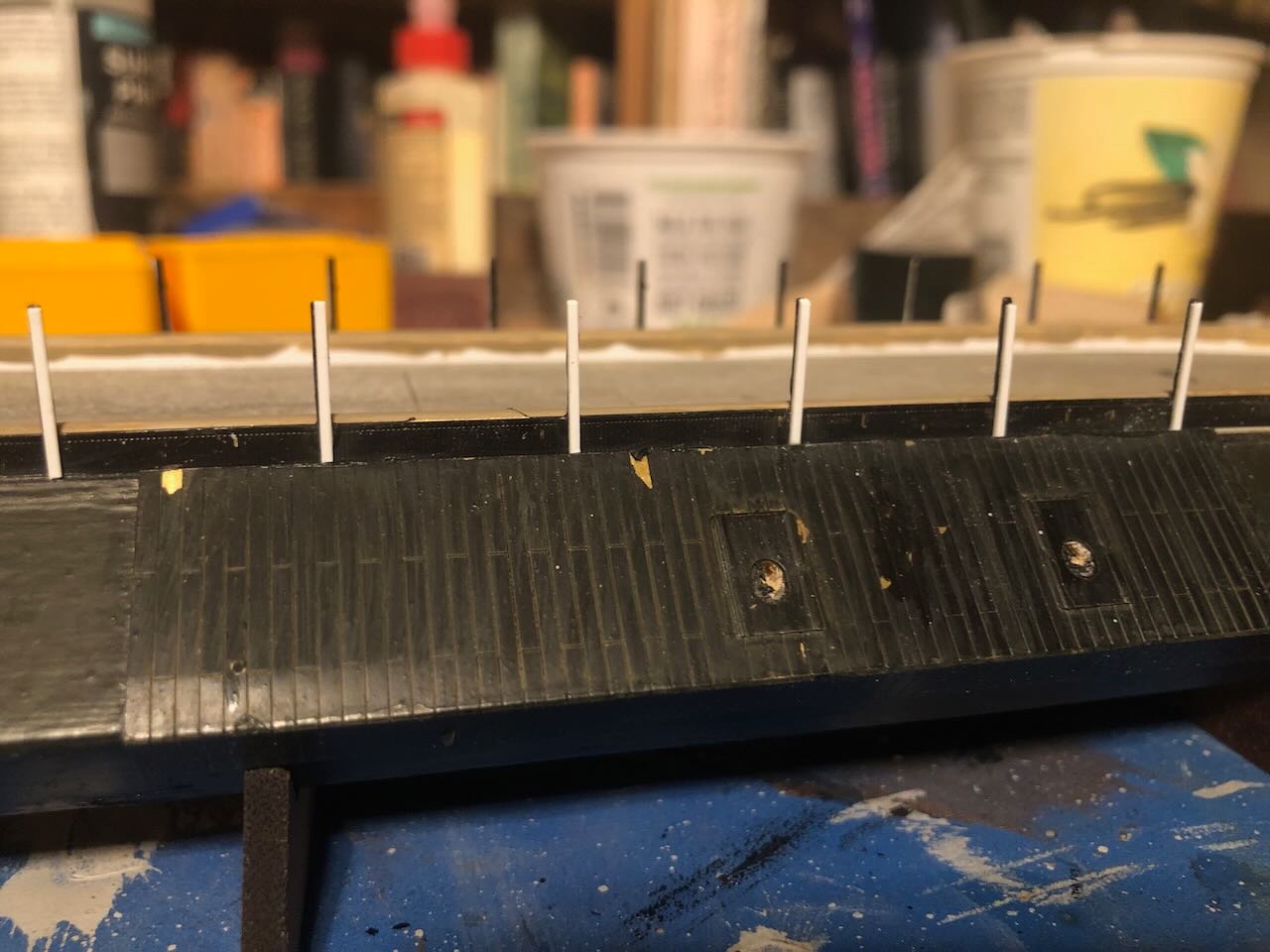

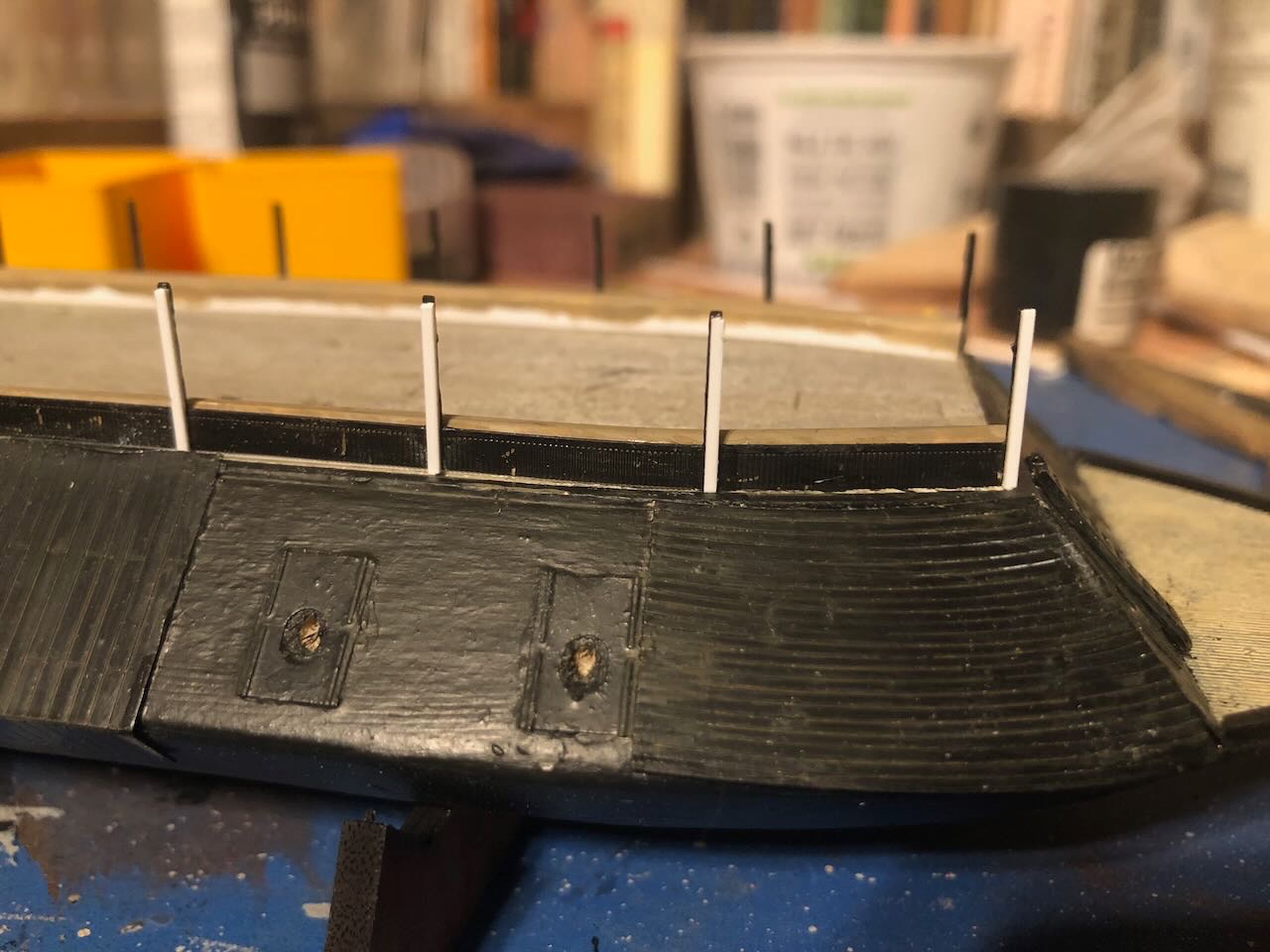

Next up, the ridgepole. This is an elevated beam that runs the length of the hurricane deck, supported on thin posts. At this model's scale, the posts are 1/32" square and the beam is 1/32x1/16". Tiny. The instructions tell you to glue the posts to the deck, then to glue the beam on top. Making a series of 90º 1/32-1/32 joints in mid-air 3/4" above a delicate model while holding the entire assembly straight and steady struck me as darn-near impossible, and not something I was going to attempt. So I made the assembly on the workbench. I couldn't find any piece of wood that matched the 1/32x1/16 dimension called for in the instructions (not necessarily blaming the kit, I could well have misplaced it), so I pulled something close out of my scrap pile. It's a little wider/taller than called for, but that also makes it stronger, and I care more about that. I used dividers to measure the distance between each post on the hurricane deck (they're marked by tiny divots in the laser-cut piece), then end-glued the posts onto the beam with an extra dab of glue over the joint to soak in. I still didn't trust these joints, and decided they simply had to be reinforced. At that point I went back to look at @mbp521's build, which gave me a lovely excuse to do this. Notice that his build included metal brackets making the connection between beam and post (logically, really). Look at the wood-colored beam running down the center of the model: So I simulated the same with small scraps of wood, first gluing all one side and then the other: Here I'm test-fitting the assembly onto the deck, and it lines up great. It's also strong enough to be handled. I just can't imagine trying to keep those joints solid without reinforcement. And here are a few pictures painted and installed. It actually adds a lot to the model, visually, especially with the grey-black brackets. Here's another case where I diverged from the instructions, which tell you to paint this on the model. No way I'm doing that and risking any paint spills onto the deck from trying to get a brush down a 1/32" square pole right to a ridged deck surface. I can't imagine why the kit doesn't call for doing it this way, it's so easy and adds so much strength and accuracy. If you look really closely, you'll see that I had to adjust for another of my own mistakes. I'd intentionally cut the posts long, but when I trimmed them to length, I did it too shot, so the beam rested on the paddle wheel housing. So I had to file a gentle curved notch into the underside to make everything fit. It's barely visible, but the beam should be a bit higher. Mea culpa. We're actually sort of getting there. I think adding the cannons will be next. What could go wrong?

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Sure, there'll be a lot of touch-up at the end. In the case of the post tops, I'll just use the same black paint the rest of the assembly used.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

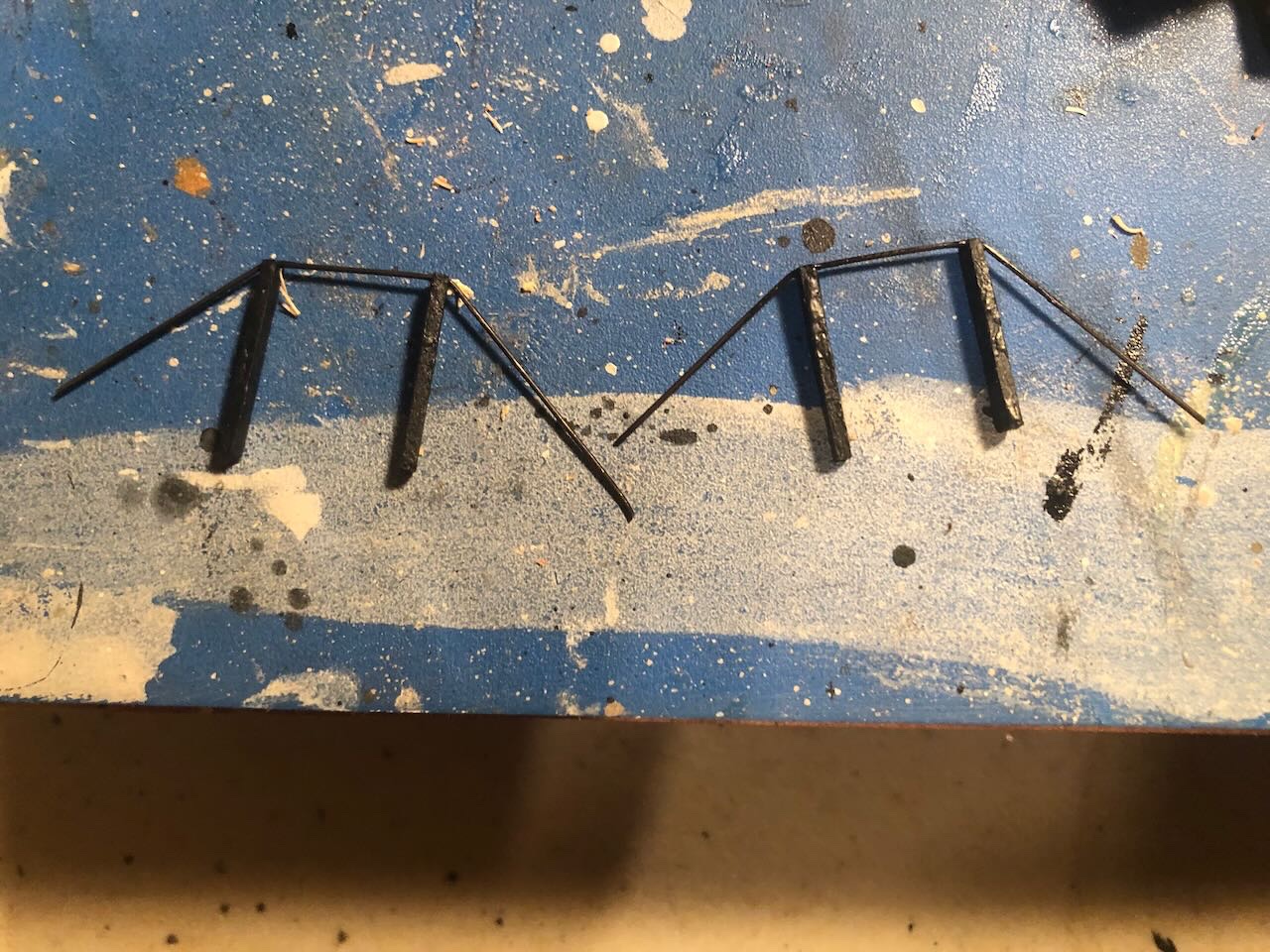

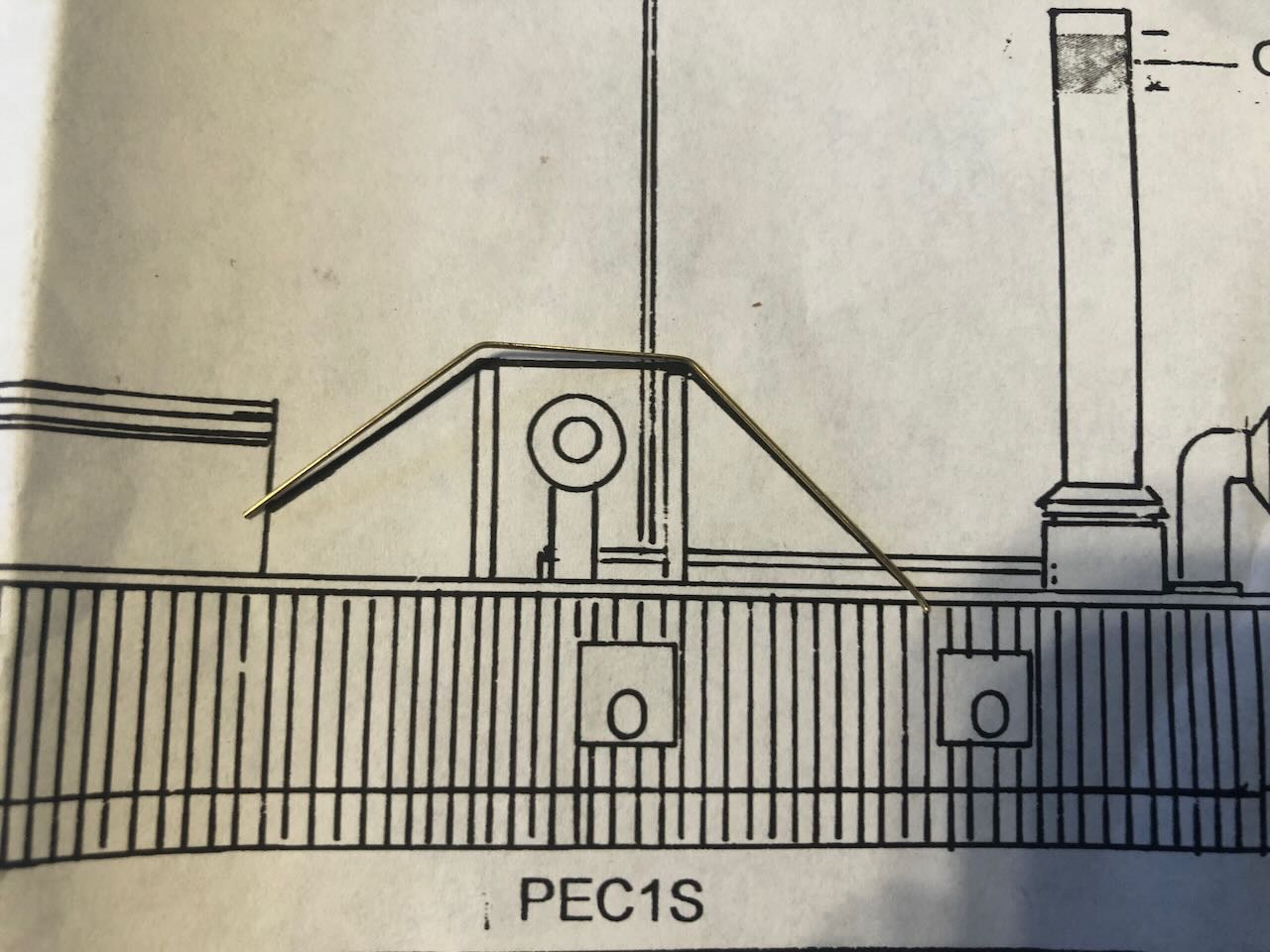

Another day, another detail, another dammit! Last night I was working on what the instructions call Torque Rods, what I would call hog chains on a normal riverboat but I don't know if different terminology was used for these vessels. Following instructions, I bend some thin brass rod to match the plans: Then cut some support posts. The instructions tell you to glue the support posts onto the deck and then install the rods over them, with the rod ends fitting into drilled holes on either side. This made me suspicious, as a tiny post glued end-on to a deck is going to be a very weak joint on its own. So I pre-made these assemblies on the work bench, filing slots in the top of the posts to help hold the rods in place: Installing these was absolutely maddening. The joints between the posts and rods kept breaking (I used CA), and getting things to line up straight was really hard. Even the tiniest bit of torque (ironically) broke or deformed the assembly and created a cascade of trying to fix that and causing other problems. I eventually gave up in frustration and went to bed, then got back at it this morning, when I finally got a version of this installed. You can see that things don't like up well, and a glob of glue on top some posts where I had to keep re-gluing joints. I don't care. I also pre-blackened the rod and pre-painted the posts. The instructions tell you to paint all this AFTER installation, which seems crazy to me. Much harder to do without getting anything on the deck, and if you do, you'll never get it off again. They'll need another coat since I wore some off with all the handling, but pre-painting still made sense to me. You'll also notice that a bump from my finger rubbed some paint off the central skylight; that's going to be a major pain to fix. I'm using Vallejo primer and paint, but it just doesn't like to hold on the brass even though it's supposed to. Now I'm working on the ridge pole that runs down the center of the whole vessel, over the deck, which is already being super-fiddly as it's incredibly small and delicate.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Yeah, I'm planning on doing some final weathering, but I've learned my lesson and won't do it until the very end. I've already had to paint over one weathering job when further work damaged it.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

On the damaged deck, you could consider hiding those areas under some detail, like a crate, a bench, a rope coil, or even a figure, depending on the exact setting. On the warped piece, you could try soaking it, then sandwiching it between hard layers (like glass or metal) and weighting it down until it dries (hopefully flatter).

- 128 replies

-

- King of the Mississippi

- Artesania Latina

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

The rudders were another adventure, this time entirely of my own making. These come as laser-cut pieces that you're supposed to simply glue to the back of the model. I had sanded and painted these when I decided to clean up my workspace. Somehow I managed to throw out the rudders. At least that's the only explanation I have since they had vanished when I'd finished straightening up. Luckily, shaping new pieces from wood is a skill I do have. I didn't have any scrap left from the kit that was the proper thickness and size to make new rudders. So I used some thinner pieces of wood and glued them in pairs of approximately the right size: I then traced the outline of the rudders onto these sandwiches and carved/sanded them to final shape: Painting was simple. I didn't trust the kit's instructions to just glue these to the back of the mode. That seemed highly delicate and likely to be knocked off. So I drilled holes and inserted two pins (made of small brass nails) to give more structural integrity. And here are the finished rudders mounted on the stern. I also installed the absolutely tiny brass tillers and deck protectors (or whatever they're called). These were pretty hard to work with, they bend super-easily and I lost a couple in the carpet for a few minutes when I dropped them. Even trying to glue these down was hard without leaving any glue trace on the wooden deck. But the final appearance is close enough. This also shows why I reinforced the rudders. Once you connect them to the fragile brass tillers, having them get knocked off would be disastrous since it would probably bend the tiller and you can't replace it. Actually, I see in the photo that the paint has chipped off the tillers in a few places that I need to touch up. Sigh. My version of this model doesn't hold up to close scrutiny! The instructions want you to simulate hinges by cutting .020" strips of paper and gluing them to the rudders. I decided there was no way I was going to be able to do that in a way that would look better than just leaving them off. At this point it's obvious that I left the whole hull black, as the instructions tell you to do. I know that others have argued for the lower hull being a dull red, and that's the sort of upgrade I'd initially intended to do, but I gave up on it as I started to get discouraged and annoyed with the kit. Simple hull color it is. I'll never make a claim that this is anything but a loose representation of the Cairo. Now we move toward final assembly and detailing.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Welcome back! Glad to see you haven't given up. Love me some cats.

- 86 replies

-

- king of the mississippi

- artesania latina

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

The chipped paint might be realistic, but the shiny brass glinting out from underneath it...less so! I don't know what to say regarding a recommendation. On one hand, I do think the kit has many flaws in both design and instructions. On the other hand, many modelers could probably make a pretty good go of it. I don't think it was a good choice for me at this time, it wasn't what I expected or wanted right now, but that doesn't mean it wouldn't be a good choice for someone else. I'll write more about this in a final review when I'm done. Thanks for reading, I'll have another update this weekend.

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

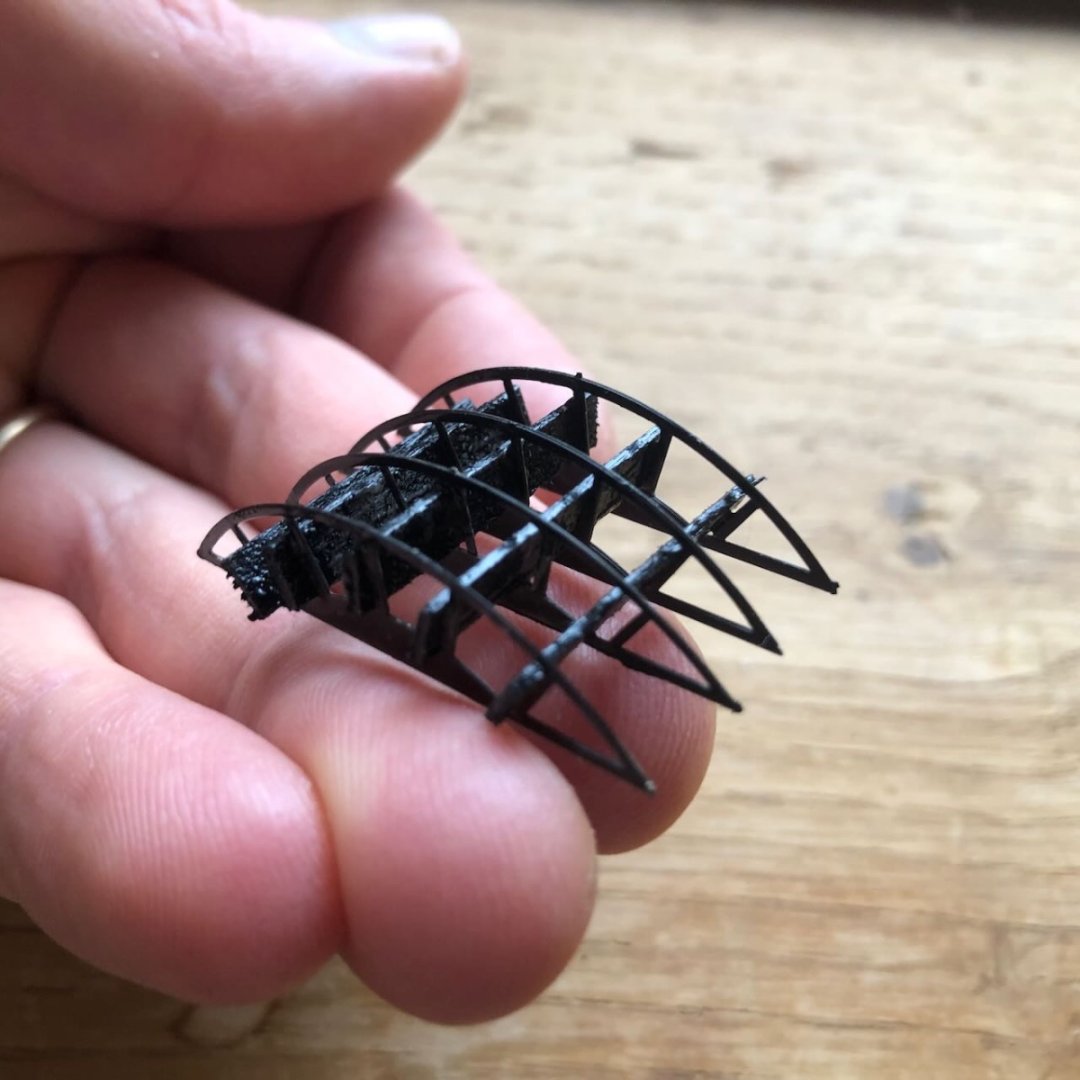

A certain amount is my fault, too, and I'll end up writing a recap/review of the whole process and kit eventually. I'm not blameless. But I do think this kit has serious flaws. Anyway, here's the process of building the wheel. It's just a fraction of the total wheel, meant to show the part that sticks down below the main deck, between the two halves of the hull. The kit provides a jig to assemble this, basically a piece of wood with four laser-cut slots that are meant to hold the wheel parts while you glue up the assembly. Makes sense in theory. Except that the slots in the jig are much wider than the very thin pieces of brass, so they aren't held in place, but wobble all over the place. I had a devil of a time assembling this because nothing stayed put and I found it impossible to keep all four pieces lined up. You're supposed to feed five strips of wood through the wheels and glue them in place. Here's the best I could do: Doing this was a royal pain in the butt, with every brass piece sliding all over the place as I tried to slide the first piece of wood in there, while trying not to get glue everywhere. Even once the first one was dry, the assembly wobbled and deformed as I tried to get the next one in. That jig is nowhere near enough to hold this steady. If I were designing the kit, the jib would be a piece of wood the full footprint of the wheel, with guides slots the actual thickness of the brass cut the full length of the brass pieces, so they could be slid snugly in and held tightly in place during assembly. If you look closely, you see that the one at far right is oddly spaced; it's at the opposite side of the struts as the rest. That's because it wouldn't fit in the smallest space provided, where it's supposed to go. It's a measure of how disgusted I was after doing the first four, that when I discovered this, I didn't even bother just thinning it down a bit to fit, but slid it in the other darned side and glued it up. This gets hidden under/inside the hull anyway and I'll just put that toward the back where no one will ever see it. The good news is that paint hides many sins, and this is getting hidden under the model (I almost didn't bother making it): One more step on the road to completion!

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Next step is to install the hammock nettings. This is an area where I initially thought I'd consider some nice upgrades, but I'm now very much in "just get it done out of the box" mode. The instructions for this stage were, as elsewhere, both confusing and in my opinion oddly structured. These are made by sandwiching a piece of styrene (the hammocks) in between two pieces of etched brass (the stanchions and nettings). This is the order of operations in the instructions: Round off the top of the styrene to look like rolled-up hammocks Glue the styrene onto the deck. Glue the brass netting strips onto the styrene. Glue various tiny pieces of .020x.020" styrene onto the nettings to fill out the stanchions. Paint in place on the model. In retrospect this order makes no sense, and I should have seen that coming. It's insanely fiddly to do all that detail work when the basic structure is already glued to the model, and in the process of trying to handle and tilt it so I could do this work, paint started chipping off the armor. Plus, I found it impossible to paint parts after they were already installed and got into a nasty cycle of leaking paint onto the deck/armor, then trying to correct it, then trying to cover those leaks, and so on. This was a super maddening stage and I came close to binning the whole thing. Here's what my attempts looked like: I pre-painted the top of the styrene in an attempt to head off the "painting on the model" problem, then glued the strips on: I also prepainted the brass netting/stanchions for the same reason, and glued those on. What I did not do, and should have, is prepaint all the styrene detail strips (though these are so tiny, this would have been awkward). I also should have assembled the styrene details on the brass strips BEFORE adding them to the model, as I found it nearly impossible to glue them on straight. You can also see the paint chipping that developed as I attempted to maneuver these microscopic pieces into place. Next you're supposed to cut a bunch of tiny styrene strips and fit them horizontally between these stanchions. I found this nearly impossible to do well on the model. I wish I'd done this all on the workbench as one assembly. And look, more paint chipping! You can also see how I'm building up too many layers of paint in attempts to correct past mistakes and damage, such that the surface is looking ever less realistic. So the problem here was that, despite my pre-painting of the main parts, I found it impossible to paint these styrene details without getting black paint on the styrene hammocks. So then I had to try and touch up the hammocks, and doing that in place on the tiny model meant some brown paint got on the stanchions, so I had to touch those up...and you see where this is going. I'm not done trying to correct each round of mistakes yet and the paint layers are getting thicker than they should. Here's two shots after I just gave up and painted the whole darn thing black before trying to reapply a solid layer of brown (which didn't work well but I haven't taken photos): You're also supposed to glue a thin styrene strip all the way along the inside of these assemblies, after they're on the model. I decided to skip this step. I didn't think I could maneuver a 10" long .020"x.020" strip into place behind those tall stanchions, with glue drying on it, without making a giant mess, and it's such a small detail it won't even be seen. If I could do this over again, I'd build each hammock assembly on the workbench, paint it, then install it. That would make it so much easier to install all the tiny bits when the assembly is flat, when there's no risk of damaging the model while fussing with it, and where I could correct mistakes without making anything else worse. I just don't understand why the instructions think you should do all of this ON the model, raw, and THEN paint it all while somehow keeping the hammock color separate from the surrounding netting and stanchions, much less off the inner deck, at this scale. Like this: Round off the top of the styrene to look like rolled-up hammocks Lay out the brass strips and install all styrene details flat on the workbench. Pre-paint the styrene hammocks and the brass/styrene assemblies. Glue finished/painted brass assemblies onto styrene hammocks at the workbench. Install finished assemblies on the model. I've also started on the paddle wheel, which was just as frustrating and oddly designed, but I'll recap that separately once I'm done (in multiple sense of the word). Can you tell I'm not having fun? Thanks to a kind member for contacting me privately and offering support for just binning the whole thing. I really appreciate the logic behind that advice, but I want something for my hundreds of dollars and many hours, even if it lives in a darker corner of the display cabinet. Thanks for putting up with my whining!

- 113 replies

-

- Cairo

- BlueJacket Shipcrafters

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.