-

Posts

2,472 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Thanks for posting that fisherman's staysail rigging information. Because it says the sheet leads down to the aftermost deadeye doesn't necessarily mean it is rigged to the deadeye the way shrouds are rigged. I have seen several instances of where a line is just tied off to a deadeye, sometimes below the lower deadeye. The rigging for the tack is interesting. I would like to see a diagram or photo showing how this was set up. Happy Holidays!

- 48 replies

-

USS Constitution by mtbediz - 1:76

Dr PR replied to mtbediz's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

According to Darcy Lever's The Young Sea Officers Sheet Anchor the tackle you are referring to is called the burton tackle (page 23), especially if it descends from the upper mast top. Sometimes it is just called a mast tackle, especially on the lower masthead. The line from the top is called the tackle pendant. These tackles were used for handling cargo, boats, cannons and other heavy objects. For what it is worth, the heaviest and strongest winch used for handling cargo on US Navy ships is still called the burtoning winch. A swifter is the after shroud if there is an odd number of shrouds. It is fitted over the masthead with an eye splice and the shrouds run down on both sides of the mast to deadeyes like the other shrouds. -

John, Thanks! Brian, The large center pipe is the vent for the heating boiler. The other ten pipes are exhausts for the four main 6-71 diesel engines, the four 6-71 diesel minesweeping generator engines, and two 4-71 diesel ships service generator engines. The diesels each had a muffler in the overheads of the engine rooms with a rats nest of insulated exhaust pipes leading up into the uptake on the main deck level (also the access down into the engine rooms) and then up into the stack.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

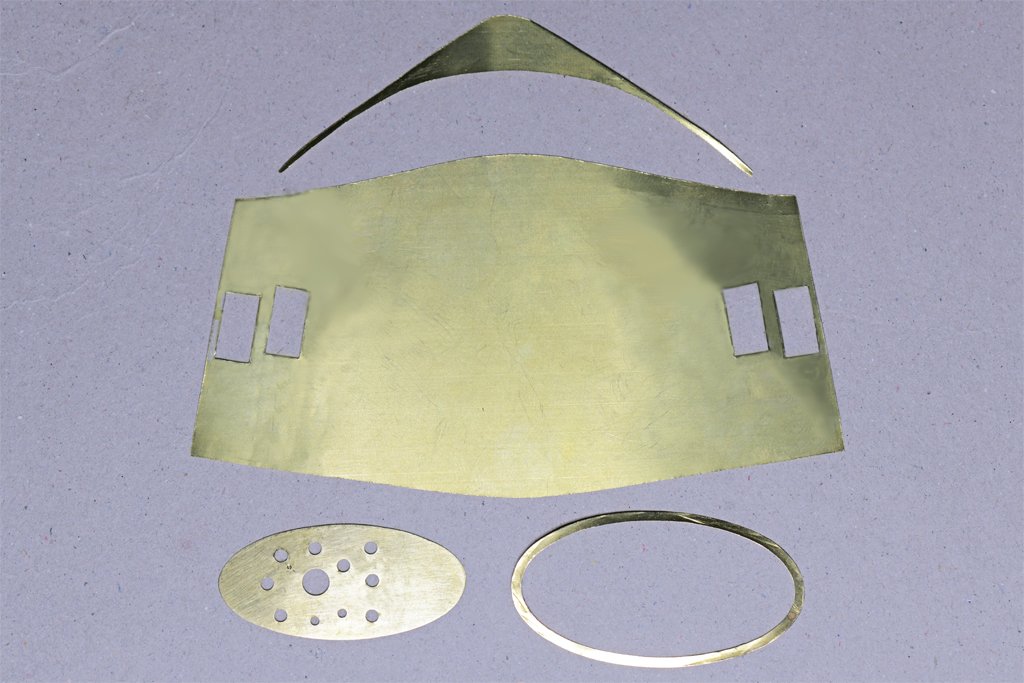

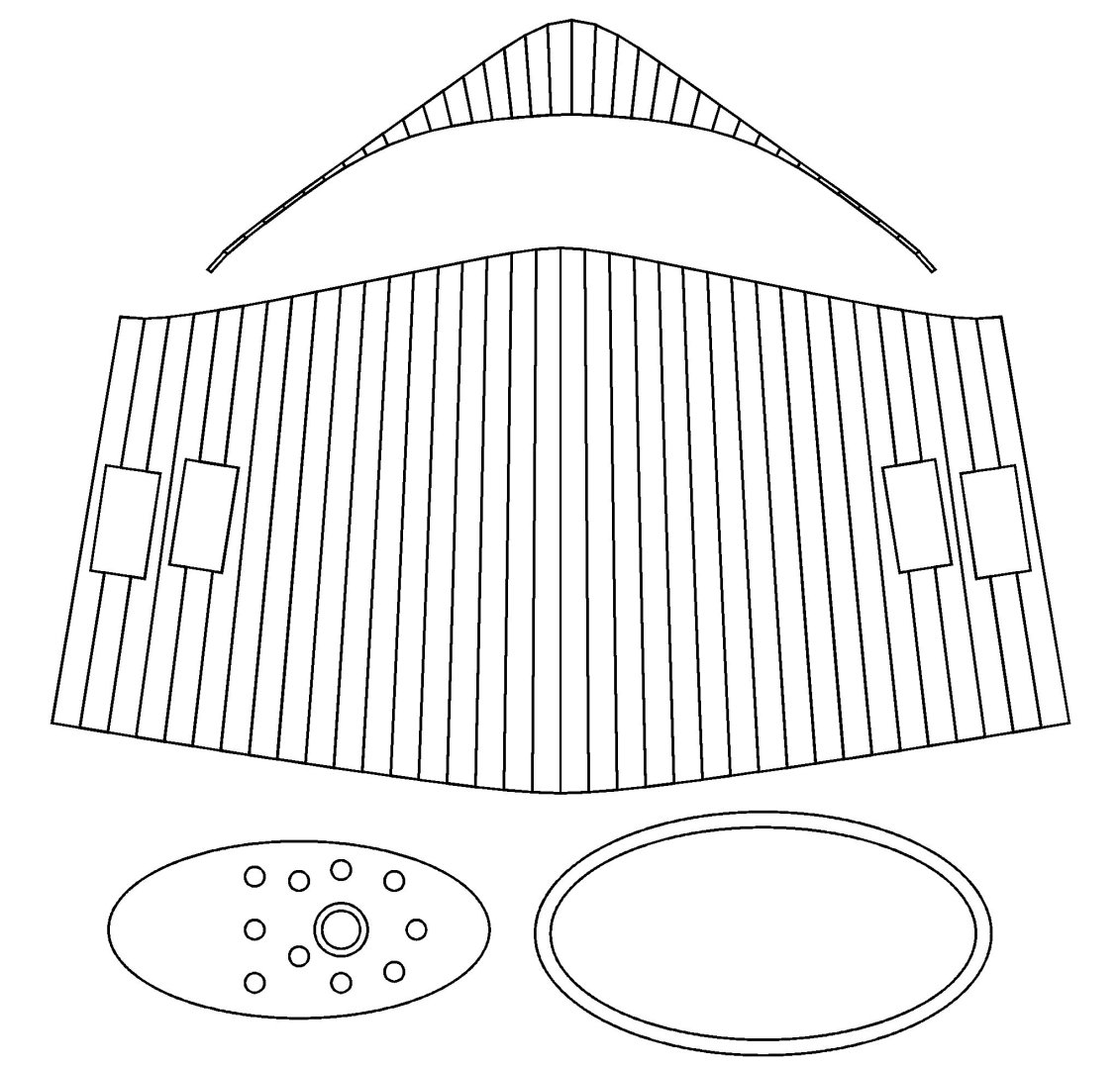

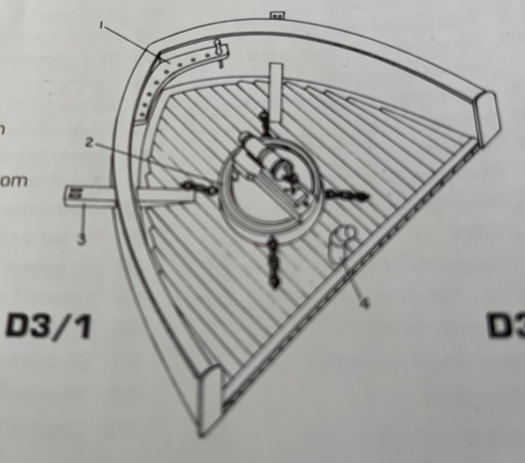

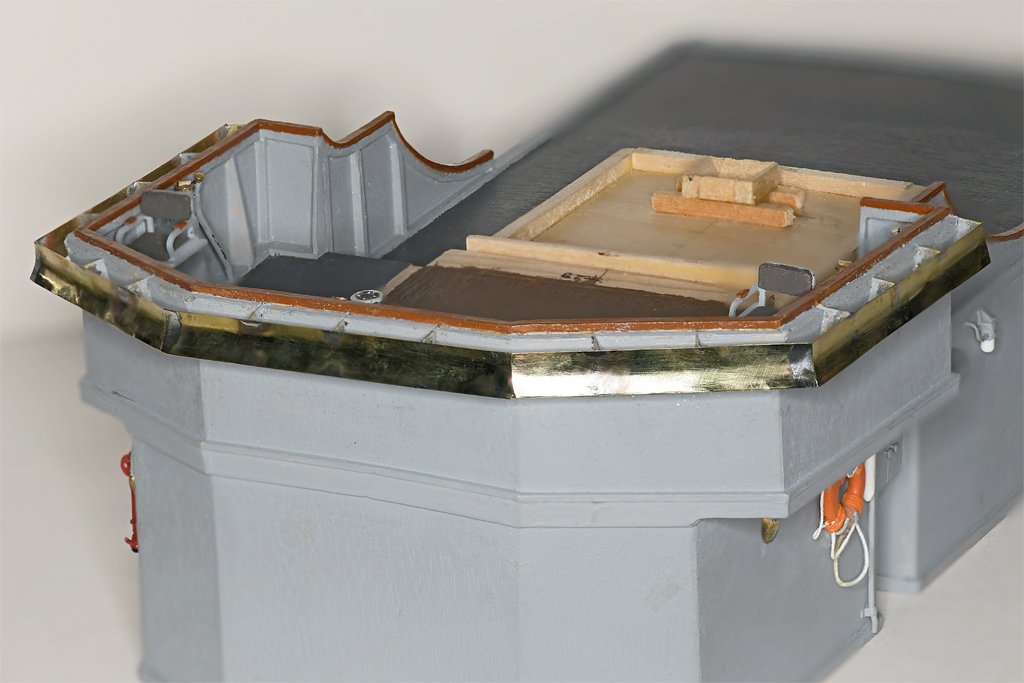

Smoke Stack/Funnel The next "detail" to add to the deck houses is the smoke stack. It is a fairly complicated truncated oval cone. I suppose I could have carved it out of a block of wood, but I wanted to try making it from brass sheet. All this brass work is practice for the machinery on the stern of the ship. First I made a CAD model of the smoke stack. The funnel cap piece was a bit tricky in CAD, but there is no way I could have made it free hand! Then I unfolded the 3D CAD parts to make 2D patterns for the pieces. I made the base for the smoke stack from 1/16 inch (1.6 mm) basswood sheet. It was sanded to the correct thickness (about 0.055 inch/1.4 mm) at the edges, and to fit the curvature of the deck. It was glued in place with Titebond Original glue, and this is where Murphy stepped in to help. While I was working on the other pieces the wood curled up at the edges to a shallow "U" shape. I didn't notice this until the glue had set, so I soaked the glue under the edges with water until it loosened. The wet glue was removed, more fresh glue added, and the thing was weighted down with a small anvil resting on a plywood scrap to force the edges to lie flat. I cut out the oval ring at the base of the stack from 0.005 inch (0.13 mm) brass sheet. Then the oval top plate that holds all the exhaust pipes was made and drilled for the pipes. A paper template for the shell of the stack was rolled up and taped closed to form the oval cone. The paper cone was fit into the base ring and the top plate was slipped into the top of the stack. This assembly fit nicely in place at the rear of the main deckhouse on the O1 level. The paper template seemed to be the correct shape so it was time to cut out the remaining brass pieces. These parts were cut from 0.005 inch (0.13 mm) brass sheet. It is pretty thin, but I think this will be sturdy enough after it is rolled up and the base ring and top plate are soldered in place. I will install the 11 exhaust pipes into the top plate before starting the assembly. They should all have tiny cover pieces, but I doubt that I can make the minute hinge parts shown in the CAD image. That top cap piece will be a bit of a challenge to solder directly onto the top edge of the shell piece. Then a 0.025 inch (0.6 mm) diameter brass wire is to be soldered along the top edge of the cap piece! It will be good soldering practice. I have already done all this once before with the funnels for the USS Oklahoma City CLG-5 model - but at 1:96 scale.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Joggling Deck Planks

Dr PR replied to DGraley's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Here is a drawing from the Anatomy of Ships book on the Beagle. This shows nibbing and not hooking. You can see the planks near the bow were not nibbed because the met the margin board at less than a 45 degree angle. The nibbed planks seem to be cut into the margin board about half a plank width. It is difficult to see a consistent angle for the nib cut, but it doesn't seem to be cut in perpendicular to the margin board edge. Most appear to b cut perpendicular to the plank edge. This came from usedtosail's Beagle build: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/37665-hms-beagle-by-usedtosail-occre-160/?do=findComment&comment=1083788 -

Joggling Deck Planks

Dr PR replied to DGraley's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

The purpose of trimming the ends of planks is to avoid sharp points that might foul lines or break off and leave a gap in the planking. Basically, if the point on the end of a plank will be sharper (less) than 45 degrees the plank should be trimmed. Planks that fit up to the margin boards with greater than a 45 degree angle do not have to be trimmed. At least that is the way is was done in the 20th century on US Navy ships. But I have seen some models where an attempt was made to nib every plank, even where the angles were much greater than 45 degrees. Check to see what Royal Navy practice was in the 1800s. For "nibbing" planks into the margin board the important thing to remember is that the cut into the margin board for a new plank starts where the outboard edge of the last laid plank meets the margin board. Then you cut into the margin board 1/3 to 1/2 a plank width. From there the cut angles back to where the outboard edge of the new plank meets the edge of the margin board. The length of the outboard edge of the nib is different for every plank. The length of that first nibbing cut seems to vary from vessel to vessel (model to model). Some people cut 1/3 of a plank width, some cut 1/2 the plank width. But the cut depth should be the same on all nibs on a vessel. The modern Navy ships I served on had 1/2 plank width nibs, but it seems older sailing vessels may have had 1/3 plank width nibs - at least some modelers do it this way. See if you can find a reference for the Beagle. The angle of the nib cut also varies. Some modelers make the cut perpendicular to the edge of the plank - this would be the same for all planks. Others seem to make the cut perpendicular to the edge of the margin board, but this means the angle of the cut on the end of the plank would be different for each plank. I know of no reference for this practice, but it may have been used on some vessels. Again, see if you can find a reference for the Beagle. This is a link to how I nibbed the planks on my topsail schooner build: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/19611-albatros-by-dr-pr-finished-mantua-scale-148-revenue-cutter-kitbash-about-1815/?do=findComment&comment=605072 I used black construction paper for the grout between planks. Some people use pencil and some don't model the grout. Just about everyone seems to have their own opinions about grout and whether to model it. ***** Older sailing vessels (pre 1800) seem to have used "hooking" instead of nibbing. In this case an extra wide plank was used where the plank run encountered the margin board. Each new plank was cut into the inboard extra wide plank by about half a plank width, and not into the margin board. The wide plank was trimmed back to the width of a normal plank from the "hook" that was formed on the end that met the margin board. The hook planks were shaped to fit the curvature of the margin board, and there were no cuts into the margin board. To do this properly you need a supply of extra wide planks for the ends of the plank runs, and ordinary width planks. For me this is trickier than simple nibbing. There are example of hooking on the forum, but I don't have a good link. Maybe someone else can provide a link. -

Nice work! Doing good work in a situation where everything fits together orthogonally is relatively easy. Fitting things together where all the angles are different and curved surfaces are involved requires skill and a LOT of patience! Card templates help reduce the amount of waste of good materials. Enjoy your holidays with the grandkids.

-

I put dilute white glue on the ratlines after it has been tied, and hang a wire hook with a light weight attached (small clamp) to make the catenary droop. Leave the weights on until the glue dries and then move on to another catenary. The white (school) glue dries without a stain. But if you are going to paint the ratlines you can use any glue.

-

John, Yes. I was a 120 day wonder (from Naval Officer Candidate School) and knew nothing of mine warfare when I reported to the Cape. Like 2nd Lt Fuzz in the Beetle Baily cartoon. I had some schooling for my new job on the USS Oklahoma City CLG-5. I did a better job there!

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

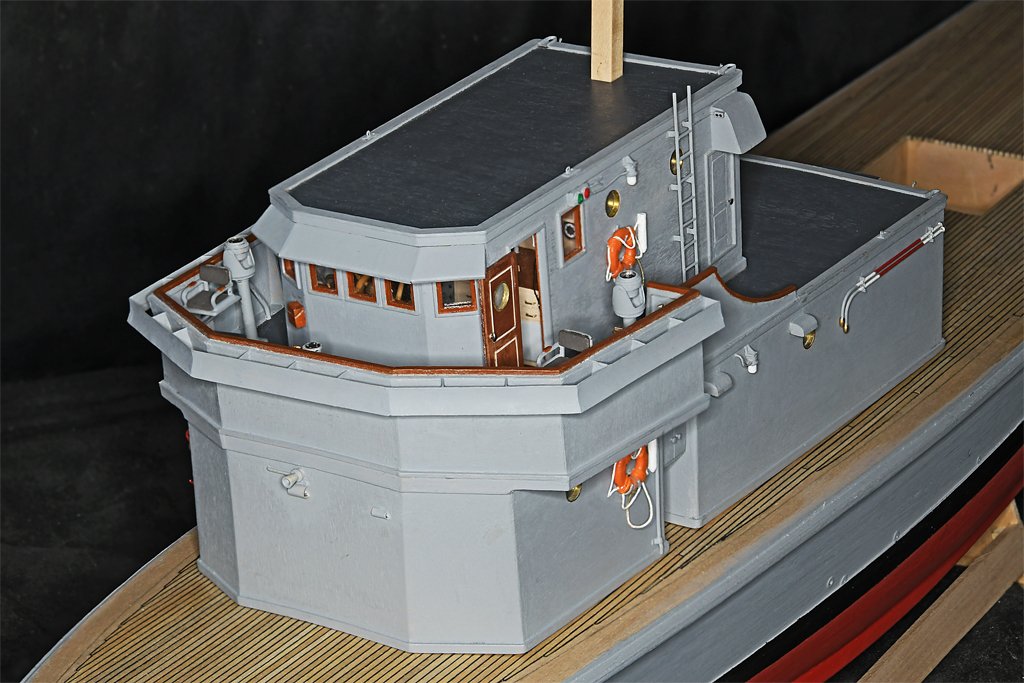

A number of things have kept me away from the Cape model over the last couple of weeks. One was an experiment to see if I could make some 1:48 scale crew figures for the Cape. Here is a link with details about the figures. https://modelshipworld.com/topic/1006-in-need-of-shipyard-workers-or-boats-crewmembers/?do=findComment&comment=1124933 I made two enlisted men and four officers, plus one female "Rosie the Riveter" figure for comparison. The officers were experiments with different dress and working uniforms. They won't all be used on the model. Here you see Captain Fred (seated), Devine Dave and Ensign Fuzz on the Cape's bridge. Dave's uniform had a lot of sand on it - he must have just gotten back from surfing.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

I am modelling in 1:48 or 1:50 scale (O scale) and have had problems finding suitable nautical figures. I still don't have a source of good sailing ship era figures. But I did notice a 50 pieces set of 1:50 figures for US$14.99: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CSC79VSQ?ref_=pe_123509780_1038749300_t_fed_asin_title&th=1 There are seven different male figures and five different female figures. One of each is seated. At 1:50 the males are about 5'-8" to 6'-2" (1.7 to 1.9 meters) and the women are about 5'-2" to 5'-4" (1.5 to 1.6 meters). These might be typical people found in a railway station or department store. They are made of a fairly soft white plastic - I assume it is styrene. It glues well with plastic cement. I found six of the male figures that were easily painted to represent US Navy sailors for the 1960-1970 period I am modelling. Two were painted as enlisted men and four were painted in various officer's uniforms. Some of the "officers" could be painted as enlisted. I also painted one of the women as a yard worker - maybe Rosie the Riveter - for comparison. I wanted to use the seated male figure for the Captain on the USS Cape MSI-2 model I am making. However, the seated man had folded arms and looked rather strange. In addition, his posterior/legs were too broad to fit into the Captain's chair. I heated the figure with a hair dryer and squeezed the legs closer together. Then some material was filed away from the outside of the thighs until the figure fit into the chair. The arms were a bigger problem. I used files and knives to cut away the arms below the elbows. Then the remaining plastic was shaped to create the lapels of the officer's dress blue uniform. Well, close to what it should be at least. Then the arms were cut off above the elbows on one of the standing male figures. These were shaped and glued onto the stubs of the arms on the seated figure. They fit nicely with a bit of shaping with small files. No putty or filler was needed. Then I made an officer's cap from styrene rod, with a brim fashioned from scrap 0.003 inch (0.08 mm) brass sheet. So here is an inexpensive way to get a few 1:50 scale modern era Naval figures with a little bit of reshaping and add-ons.

-

I usually use Squadron white putty. It dries quickly - 30 minutes. It sands easily. But it is chalky white and not very hard, so it is best for filling small holes and cracks up to about a millimeter wide. For narrow cracks in wood I use a glue mixed with sanding dust from the wood to be filled. Duco Cement is colorless nitrocellulose in acetone and makes a nice hard filler when mixed with wood. SigBond or Titebond aliphatic resins are white or pale yellow when dry so they changed the wood filler color a bit. Elmer's school glue is white, but it dries colorless. These all set up in 20-30 minutes, but need to sit over night to harden.

-

This is a beautiful ship! I will be watching to see how you rig the fisherman's staysail. What little I have found showed the sheets belayed to cleats on the boom. But your photos seem to show it belayed to the bulwark. I suppose it could be rigged either way depending upon how they were sailing.

- 48 replies

-

Kurt, Willapa Bay is on the West Coast of Washington, just north of the Columbia River. There is no clear weather half the year. That lumber would have sat out in the rain at the mill for some time before being loaded (probably in the rain). That's a good photo of a loaded lumber schooner. It always amazes me that they floated at all! It has a high center of gravity, and that means it will roll a lot in swells. And it will be heading south along the Pacific Coast to California for about 500 miles with swells parallel to the coast all the way. That's several days rolling in the troughs between swells. It would be a rough ride in clear weather!

-

Repurposing Pool Cue Lathes?

Dr PR replied to Rich Sloop's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I used to use my drill as a "lathe" and turn masts and spars with files and sandpaper. But when I started my topsail schooner build I decided to get serious about mast construction. Sailing ship's masts were not cylinders or cones and had a lot of faceted sections. Here is a link to the traditional method of mast making: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/19611-albatros-by-dr-pr-finished-mantua-scale-148-revenue-cutter-kitbash-about-1815/?do=findComment&comment=908539 -

I was about 6 when I started building balsa airplane kits. These used very thin sheet wood that had to be rolled and curved to make the fuselage and wings, and it was pretty tricky. Really out of my class at the time. They weren't a thing of beauty when I finished them, but I enjoyed building them. At about 7-8 I saw my first plastic model (panther jet - probably Monogram) and I was hooked. I had a fleet of 18 plastic ships (mostly Revell) and a bunch of airplanes while in grade school. I built three or four plastic sailing ships with minimal kit rigging. When I was about 10 I wanted a model of a schooner but there were no kits in my hometown hobby shops (mid 1950s and no model magazines or Internet). Our city library had no books on ship modelling. So I built my first scratch build out of balsa based on sketches of schooners from television ("Adventures in Paradise"). That was followed a year later with a scratch built 40 foot Chris Craft cabin cruiser like one of Mom's friends had. When they visited our lakefront place I got to drive it! Again, no plans, just sketches. I used a motor drive and propeller from a Lindberg destroyer kit. So you shouldn't rush or delay kids if they are interested in ship models. 10-12 would have been way too late for me! Just encourage them if they show some interest and offer help if they need it. They will either try to build something or just forget it. If you are going to start with a wooden kit, make it very simple, like a canoe kit, or one of the Vanguard wooden boat kits (the 18 foot cutter was pretty easy). There is a lot more to learn with wooden builds than something simple like gluing pre-shaped plastic pieces together. **** Let me stress that there is no "one size fits all" age for kids to start modelling. Watch them, and if they like using their hands to make things they will be ready for some level of modelling. If they would rather read or play video games you will be wasting your time trying to introduce them to modelling.

-

John and Steve, Thanks for the compliments. And thanks to everyone for the likes.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Final venturi work. For all the worrying I did about making the venturis, I think they came out pretty nice! They seem to be very sturdy. The vents and horn on the face of the deckhouse complete (I think) all the details on the sides of the deck houses. But I still need to make the name boards.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

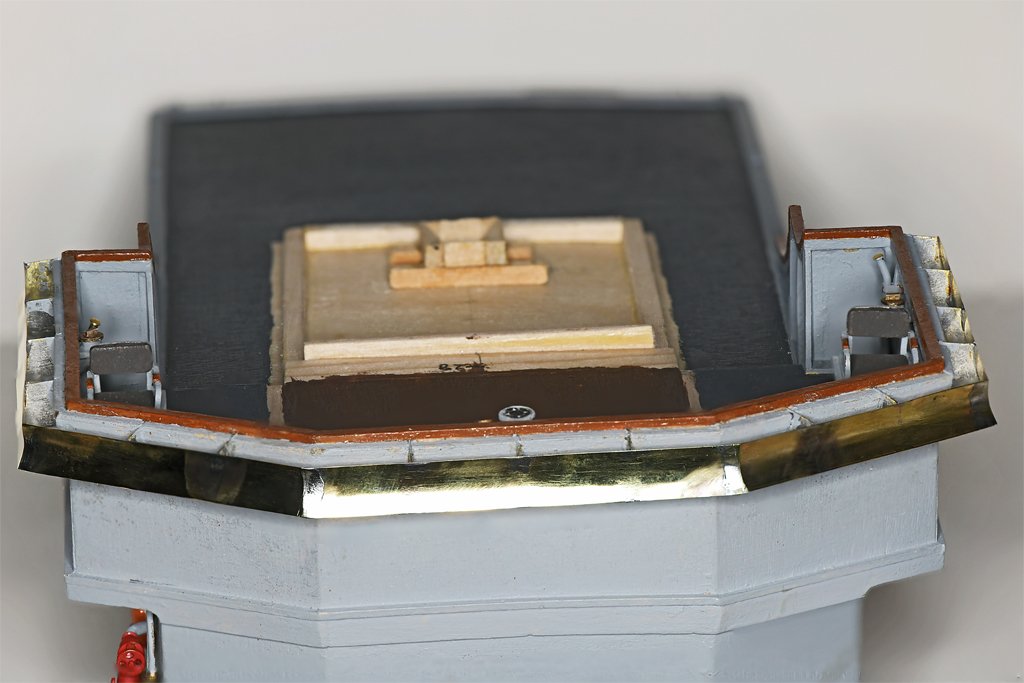

First I painted the chokes and supports. Then I cut cardboard templates for the sections of the venturis. This let me make an approximation of the lengths and angles for the parts. Then I started cutting pieces out of 0.005 inch (0.13 mm) brass sheet. This was frustrating! I used the shear to cut the strips, and it was nearly impossible to make multiple strips of the same width throughout the entire length. I cut eleven 4-6 inch (100-150 mm) long strips in all, and only four were the desired 0.260 inch (6.6 mm) width! I debated whether to use CA glue or to solder the strips onto the supports. CA would be faster and easier, but it is somewhat brittle and might break if the venturis were hit. Soldering would be stronger and less susceptible to breaking. So I chose soldering. It went pretty smoothly, with only one of the supports being knocked off (twice) before everything was all together. Now I just need a bit more clean up to remove excess glue and solder, and then paint. The "mahogany" cap rail on the bulwarks came out a bit worse for wear while I was installing the venturis and needs another coat of paint.

- 492 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.