-

Posts

1,003 -

Joined

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Waldemar

-

.thumb.jpg.c6343966b029e7941df5b987d129aac6.jpg)

2nd rate London 1656 – the art of the shipwright

Waldemar replied to Waldemar's topic in Nautical/Naval History

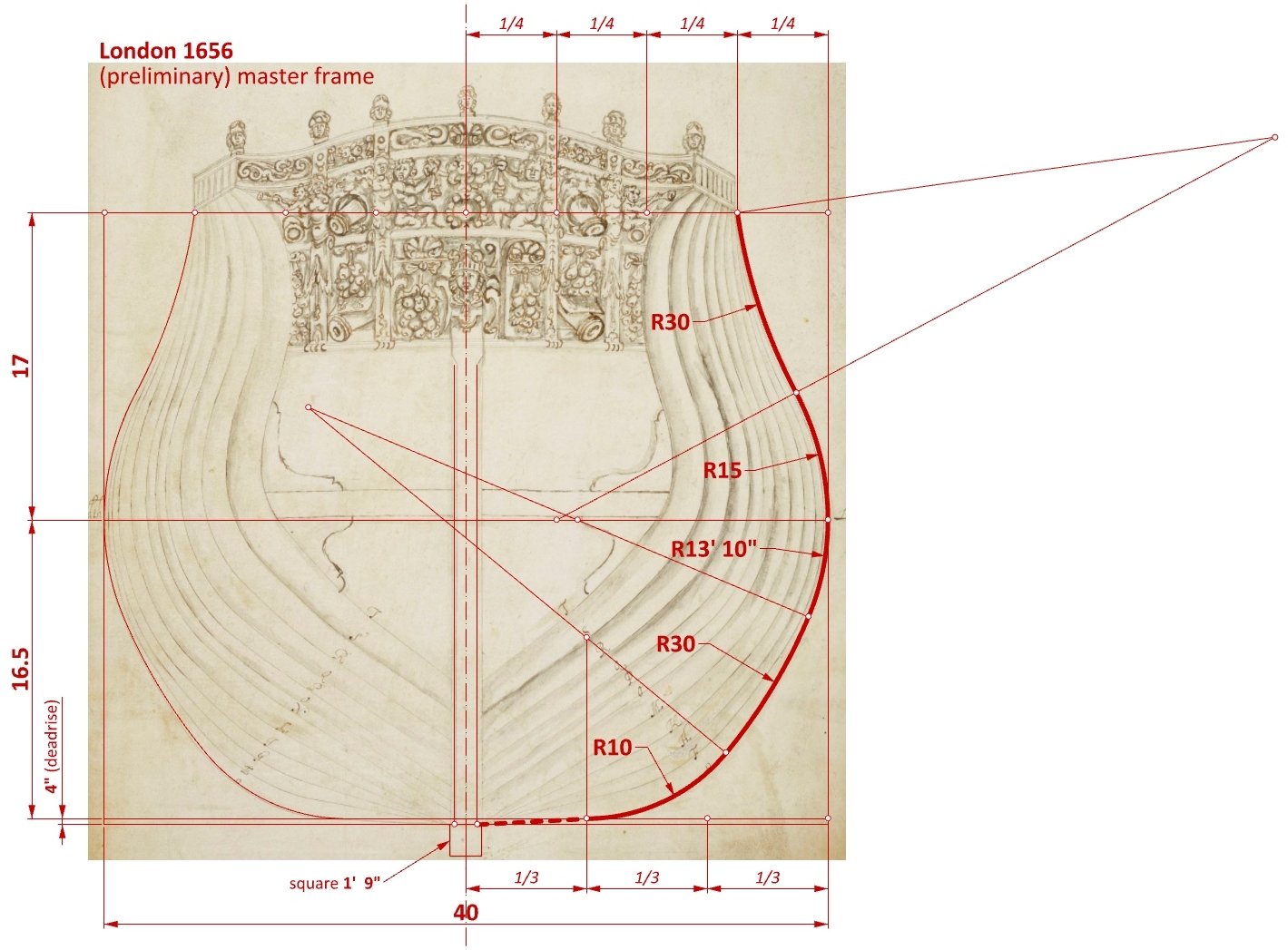

Right, good question. If you mean the radii of the main frame, they were read by me from the original drawing by fitting circles of different diameters to the original curves. In contrast, the early modern shipbuilder chose these radii arbitrarily, within the limits imposed by past experience, the geometrical constraints of the designed ship's hull, the properties of the available material and the result he wanted to achieve (e.g. greater capacity or better seaworthiness of the ship, etc.). -

.thumb.jpg.c6343966b029e7941df5b987d129aac6.jpg)

2nd rate London 1656 – the art of the shipwright

Waldemar replied to Waldemar's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Martes, thanks for posting the rest of the graphics. Admittedly they will not be needed for the reconstruction itself, so I did not post them, but they indeed may be of interest to others. Allan, thanks for the calculations. I am still wondering if and how such data can be effectively used in this case, and in particular room & space. The problem is that evenly distributing the ribs as drawn on the original plan along the hull, according to any regular room & space, would result in a wavy hull. One can ignore this circumstance and start building the model according to the original contours, but such an attempt will only end up with a hopelessly wavy as well as generally spoiled hull, because the original plans are also deformed in other ways. Anyway, this thread is not so much about woodworking, but it is rather on the underlaying concept employed by the creator of these 17th century plans. * * * Relatively the easiest part of the job is recreating the ship's master frame. It's hard to imagine a more classic shape than this one. As it happens, the proportions of the design grid perfectly match the ship's known dimensions. -

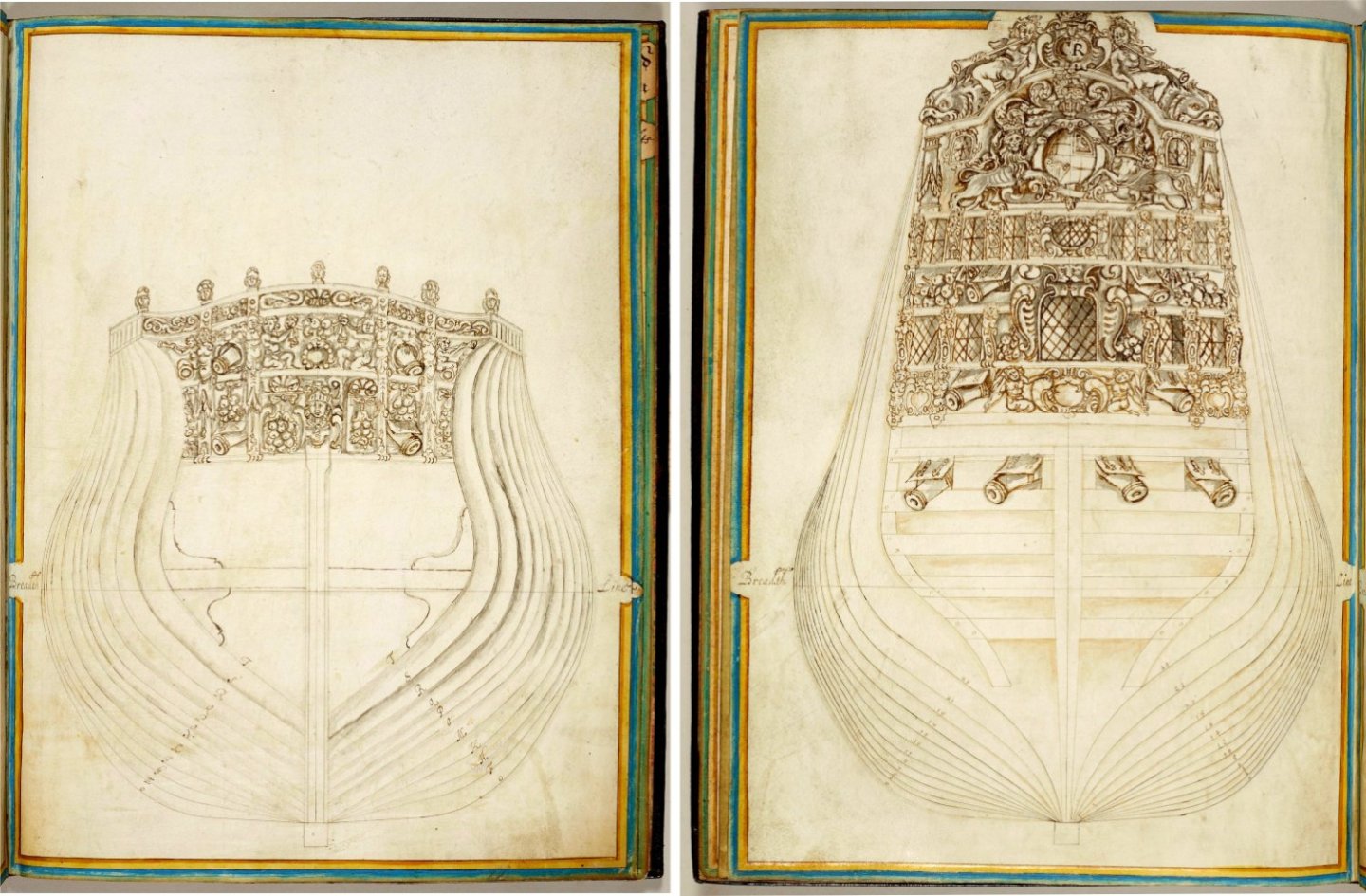

Persuaded by a clever ruse by Martes, one might say - a specialist in finding both important and interesting material on the history of shipbuilding in the on-line archives, I became more interested in the plans of the 2nd rate ship London of 1656 (built by John Taylor), which were apparently made during the ship's years of service. Be that as it may, the drawings of this ship deserve the utmost attention, as they come from a period from which hardly any shipbuilding plans have survived, so it is not entirely clear how exactly the conceptual methods known more or less theoretically from the textbooks were actually applied at this particular time. Ship dimensions (taken from British Warships in the Age of Sail 1603-1714 by Rif Winfield): as built: 123 1/2 (keel) x 40 x 16 1/2 as girdled: 123 1/2 x 41 x 16 1/2 The plans are promising, however already a preliminary graphical analysis of the plans has shown that the contours of the frames have been drawn in a very irregular way, as if the room and space value was randomly varying along the length of the hull, which clearly cannot be the case. This is a fatal circumstance, as it makes the reconstruction of the conceptually extremely important longitudinal guides (rising and narrowing lines of the floor and breadth) very difficult, if not possible at all, on this basis. In other words, it is difficult to establish whether and which guides were fragments of circles, ellipses or logarithmic curves. Certainly, one can refer to written works, but the point is, after all, to read it from the drawing, not to arbitrarily select their shape from other sources. But there is perhaps no other way... And here are those drawings:

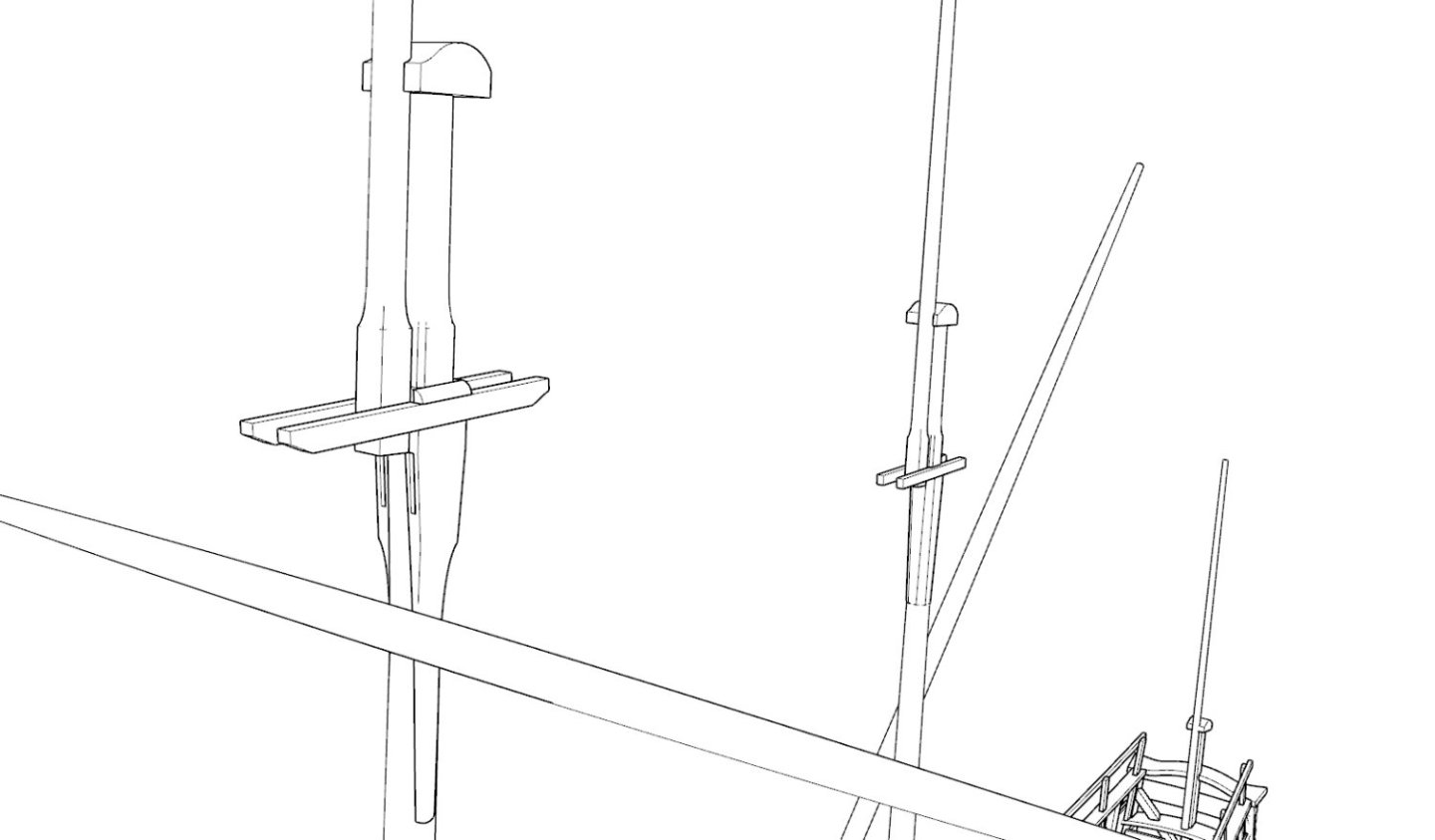

-

@Blas de Lezo Blas, your question is a very good one, as it will allow me to clarify the general mechanism of my reconstruction. This reconstruction is not based on any plans, because such plans are non-existent. I am also not basing it on any modern interpretations or today's reconstruction/modelling plans of other ships (unless for results comparisons), but solely on the primary sources from the period. In fact, I am creating this 3D model from geometrical-visual scratch in order to later produce 2D documentation for modellers on this basis. The example of the main mast illustrates this reconstruction process very well: From the notarial fleet inventory of 1629 (Inventarium uber Ihre Königl. Maytt. zu Polen undt Schweden etc. Erlogs Schiffe, so den 8 February A[nn]o etc. 1629 zu Wismar glücklich einkommen, undt daselbst besichtiget worden. Wismar den 3/13 February 1629) it is known that the larger ships of the fleet had a main mast of four parts, as it lists three sails for this mast, and flags: main course (ein Schon Vor Segel mit seim Bonnett), topsail (ein gross Marss Segel) and topgallant sail (ein gross Bramm Segel). Then, the dimensions, shape, position, rake, accessories and arrangement of the masts are taken from the two 17th century Dutch manuals I mentioned earlier in this thread: Evenredige... (c. 1650) and Witsen (1670), and in addition from iconography, shipwrecks and period models such as Peller-model (1603), Tyresö-model (early 17th century), Vasa (1628), Norske Løve (1634/1654), all of which are Baltic ships models. Now, back to your question: Generally, masts taper at the top between 2/3 and 3/4 of their largest diameter (at the partners), and the length of their tops (i.e. above the circular fighting top) is 1/10 the length of the mast (taken from the works above). Masts are shaped like a fragment of a circle rotated around the mast axis. But that's not all, the cross-sections of the mast change along its length. They can be circular, elliptical, quadrangular, octagonal, be it regular or irregular. Below is the appearance of my mast at the fighting top height (please note its variable cross-section and the side cheeks supporting the trestletrees). I personally have no need in this particular case to convert NURBS geometry to a mesh (i.e. to STL or OBJ format), but Rhino does a good job at such an export. You can also convert NURBS geometry to a meshes and then edit them inside Rhino, as Rhino has advanced tools for such mesh editing. I love this program, it only has one drawback, acutely important to me: it doesn't always do a good job of converting 3D shapes to 2D projections, and as a result, it often has to be done manually. But this actually may not apply to you... Feel free to ask any other questions, preferably ones that I can answer. 🙂

-

@Martes Martes, I saw in your thread that you were creating attractive images of 3D models of ships from this era, but you have now just made me aware of your diligent approach to this project. Few, maybe even no designer for movie, animation or video game purposes except you, would care about such details, especially after encountering any difficulties. The secret of the appeal of your models is also explained – they are not sloppily based on the designer's imagination, but on real, historical data. It is something like this that distinguishes a reliable professional/researcher from others and creates his authority. Respect is due.

-

Thanks a lot Martes! But wait a minute! After all, these are two different photographs and we can even play the popular game "find 10 differences in two pictures". In one there is no rudder chain, in the other there is no boom support, they are at a slightly different angle, maybe something else....

-

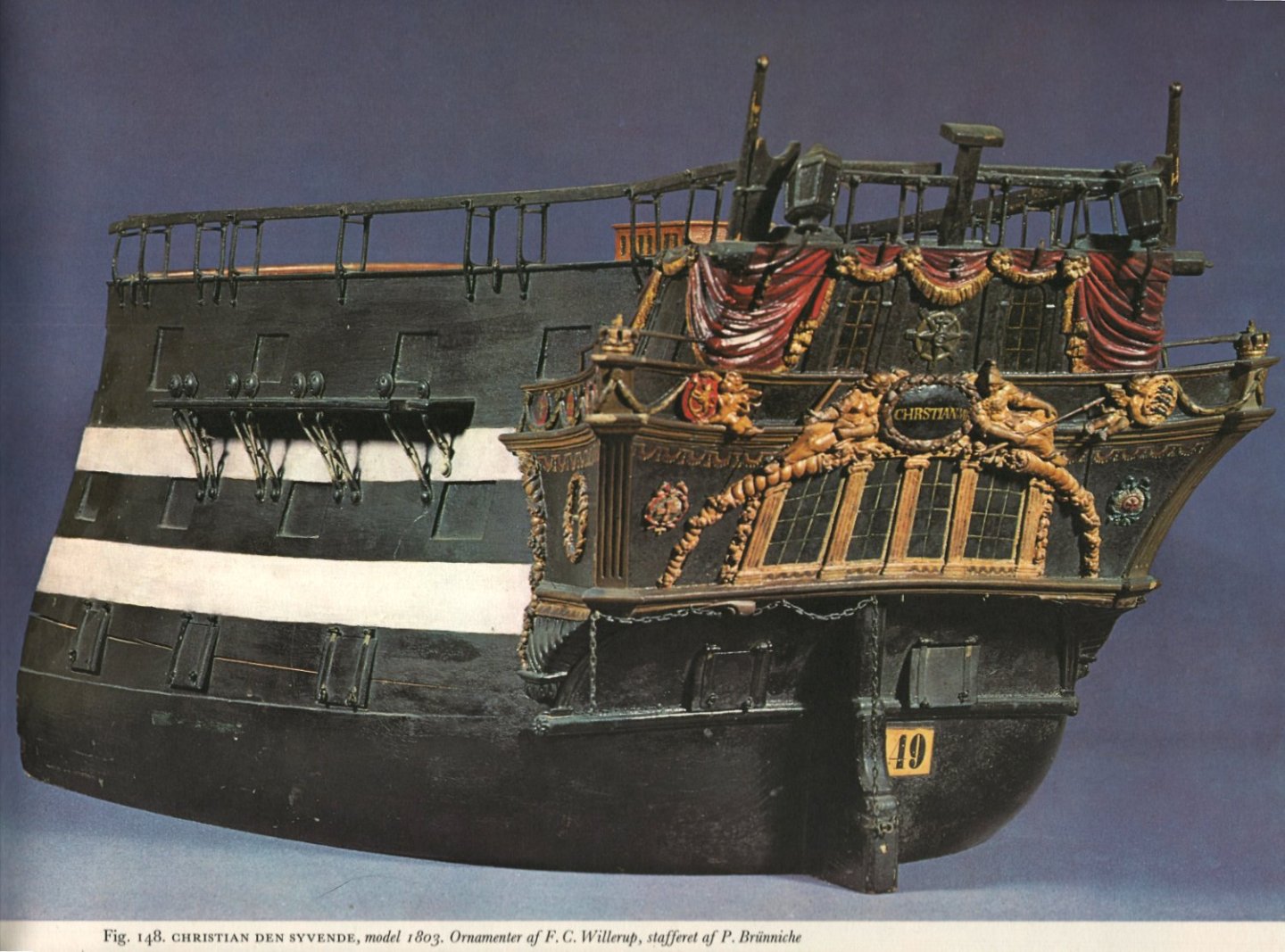

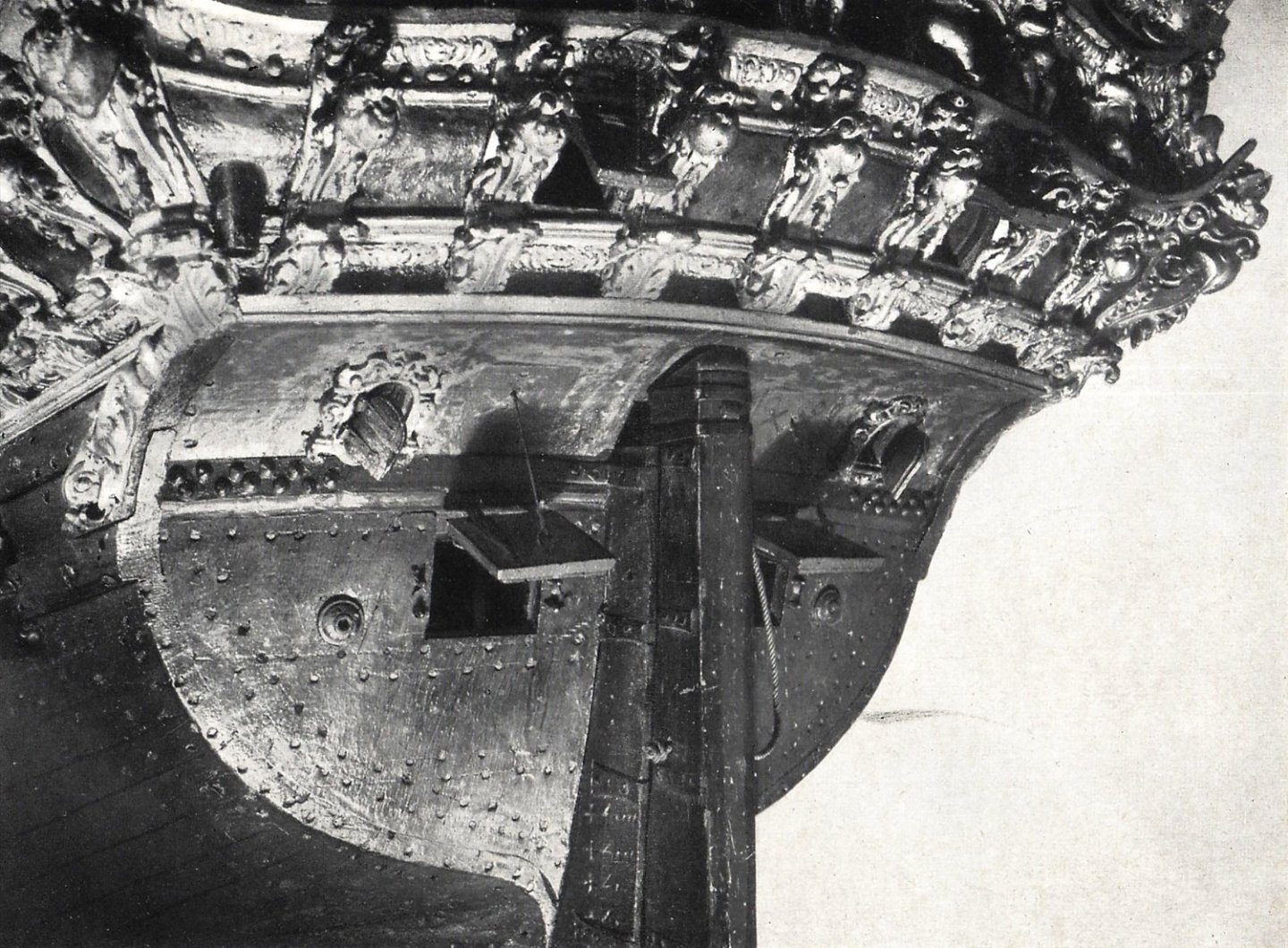

@Martes Ah, it's as much your space as mine. And you in particular are always welcome, as after all I am still in your debt especially for pointing out good copies of the originals of early 17th century ship plans in the Russian Hermitage (those presumably by David Balfour or his contemporary). Anyway, now you have no choice but to make the inevitable detective visit to Europe, specifically Copenhagen next summer 🙂. That's how I've had to go to Stockholm and a few other places on more difficult cases in the past, too. Until then... however, I decided to scan the one photo shown above, which may not be in the Danish online archives. Indeed some bending can be seen there... Compressed JPG file (6804x5037 pixels): model of the Christian VII's stern.zip

-

@Martes You have probably already found something on the web about the model of Christian VII. If not, and if the matter is still relevant, I can offer you to make scans of the below illustrations from the Danske Orlogsskibe 1690-1860. Here only photos, because of the large format. Anyway, when asking for help of this kind, it is essential to show your work. This is always effective, and the Scandinavians are particularly kind and helpful, as I have personally experienced many times.

-

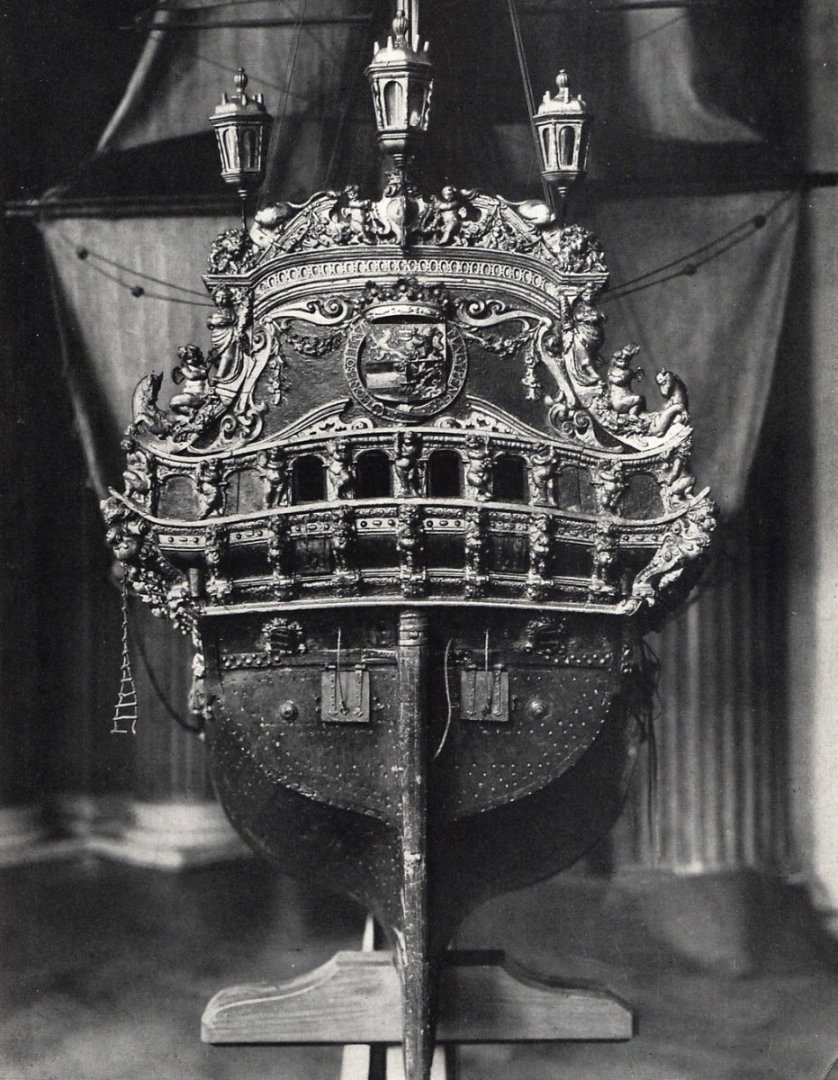

Thanks to the extraordinary kindness of Danish museum curator Peter Kristiansen, I can now also exploit the full potential of an extremely important model of the Danish ship Norske Løve (ship built 1634, model built 1654), especially for reconstructing the masting and rigging. The masts themselves are almost complete. To give an idea of the appearance of this unique model, I include below a photo taken from the website of The Royal Danish Collection in Rosenborg Castle:

-

Hi Patrick, huge congratulations! The model is wonderful, but just as good is your ability to finish a very long, arduous build. Have you noticed that, for some reason, it is only sailing ship models that are suitable for beautifying prestigious spaces like living rooms in houses or halls in residences? You said another one was the Mary Rose...? 🙂

- 756 replies

-

- galleon

- golden hind

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Hopefully it may be even more interesting for you, as this model is believed to be actually left by the Sea People in one of the fortress they occupied in the Nile delta. I just wanted to make sure you knew of its existence.

- 142 replies

-

That's right, again. There is more about it in the book and it was used to date the model, but I am not sure if it will be needed by Dick. But I would also scan the passage if necessary.

- 142 replies

-

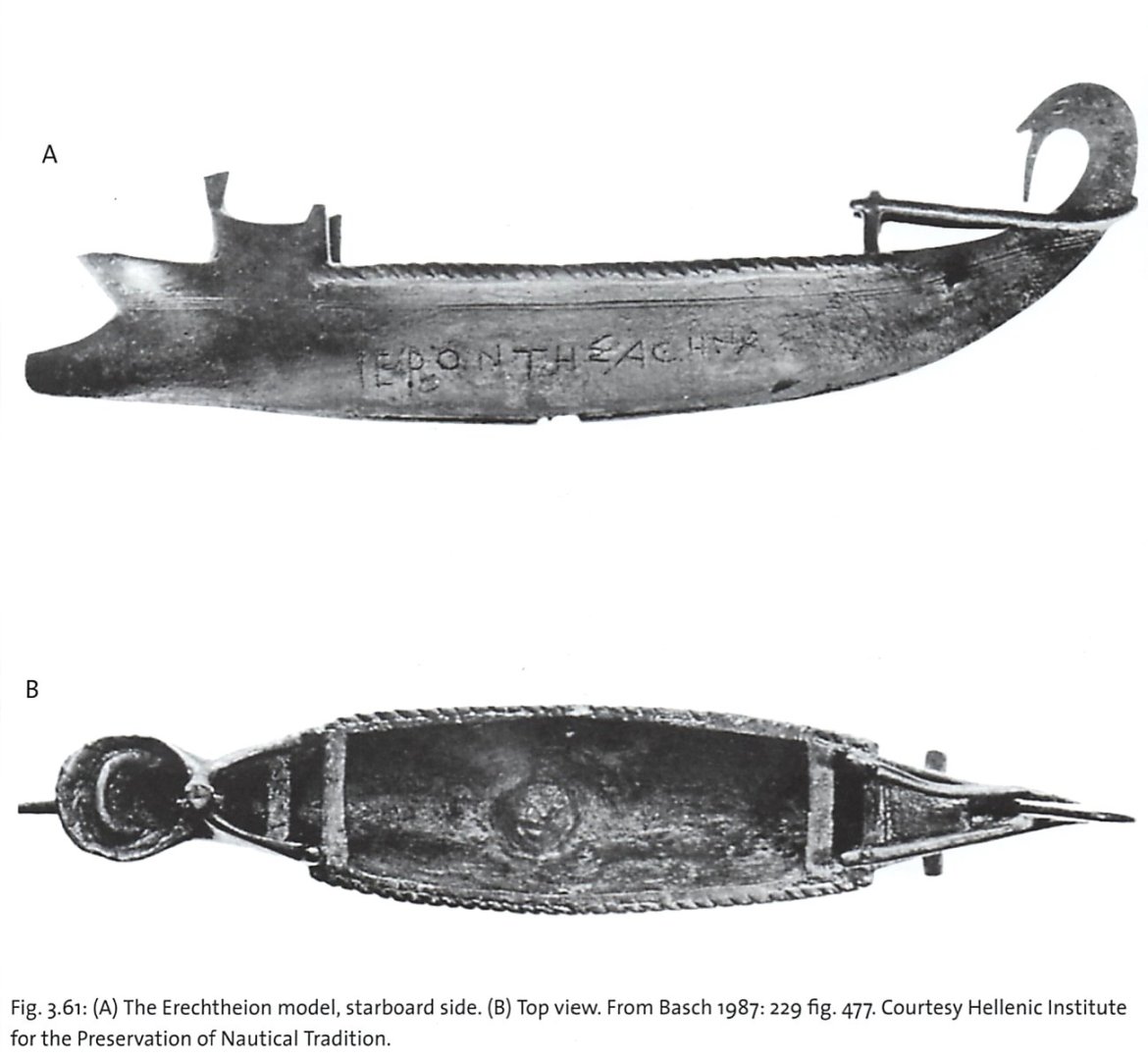

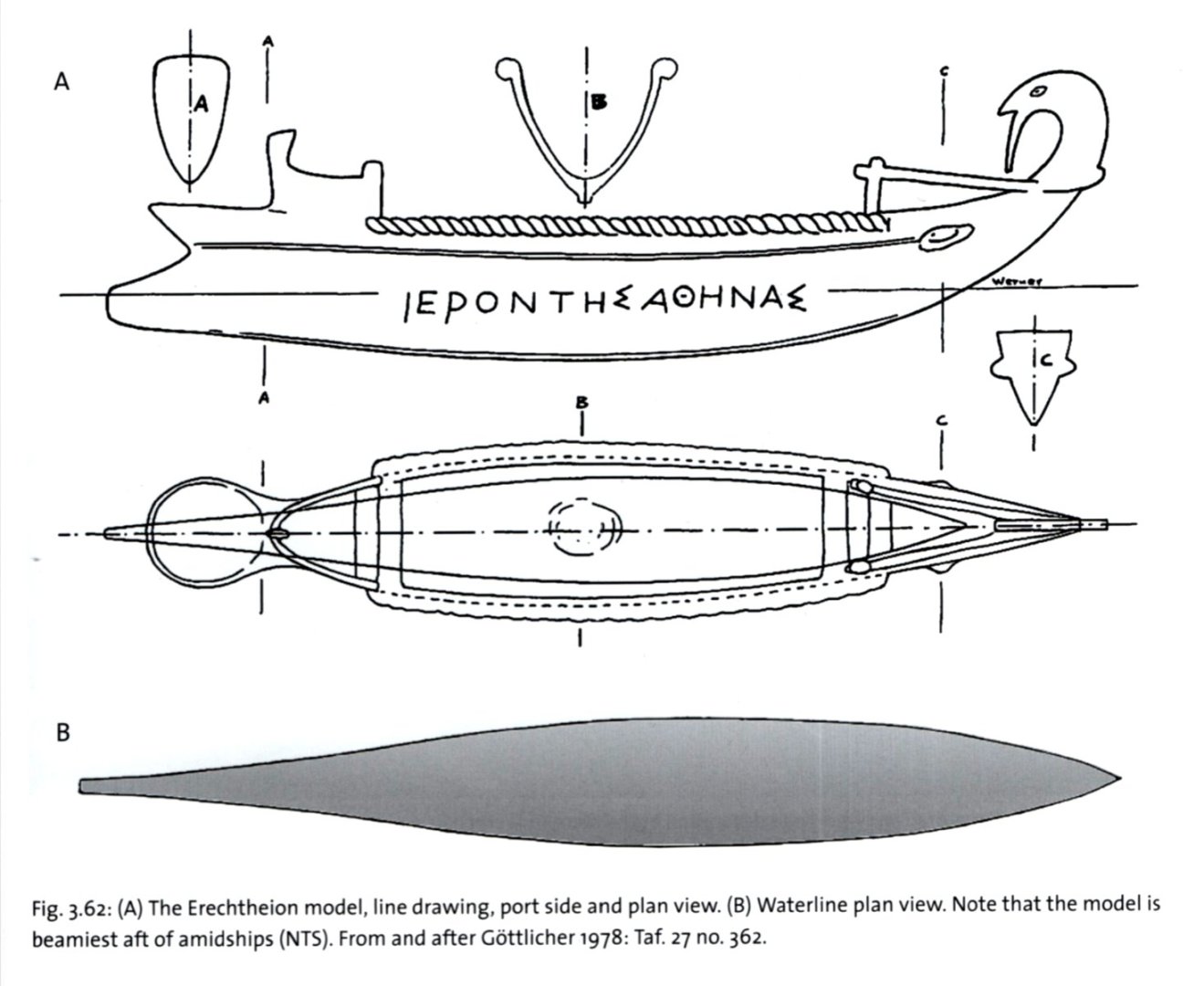

No, there will be no comment from me. I'm just suggesting material that you will or will not use. From the book The Gurob Ship-Cart Model and its Mediterranean Context by Shelley Wachsmann. It's about a model of a vessel found in Egypt, yet identified by Wachsmann as a Sea People's ship. Link to its digital model (showing both remains and reconstruction): Gurob Ship-Cart Model Digital Supplement - VIZIN - Institute for the Visualization of History, Inc. Sample page: And also two illustrations of another model (4th cent. BC?) taken from this work:

- 142 replies

-

Now perfect! I don't think I'll ever forget Ab Hoving's words (from memory): „having seen many dozens of wrecks and models of Dutch ships from this era, I can't even imagine a single instance where the lowest strakes don't cover the sternpost”. But I promise to not interfere with your build at least for a while... 🙂

-

Thank you all. For the time being, and just for my personal use, I consider these coils to be temporary holders for the two heaviest yards, used only in very special situations (say, like replacing worn or otherwise out-of-service yard hoisting ropes). However, any other convincing solutions are always welcomed.

-

I am terribly curious to see what solution Dick finds and what methods he uses. Steven, with your assistance it will certainly be much easier for him, I think more so than with anyone else's. And more interesting for others. I'm now going to limit myself to just watching rather than actively participating. It's bound to be an interesting project, plus Dick's ability to see his projects through to completion.

- 142 replies

-

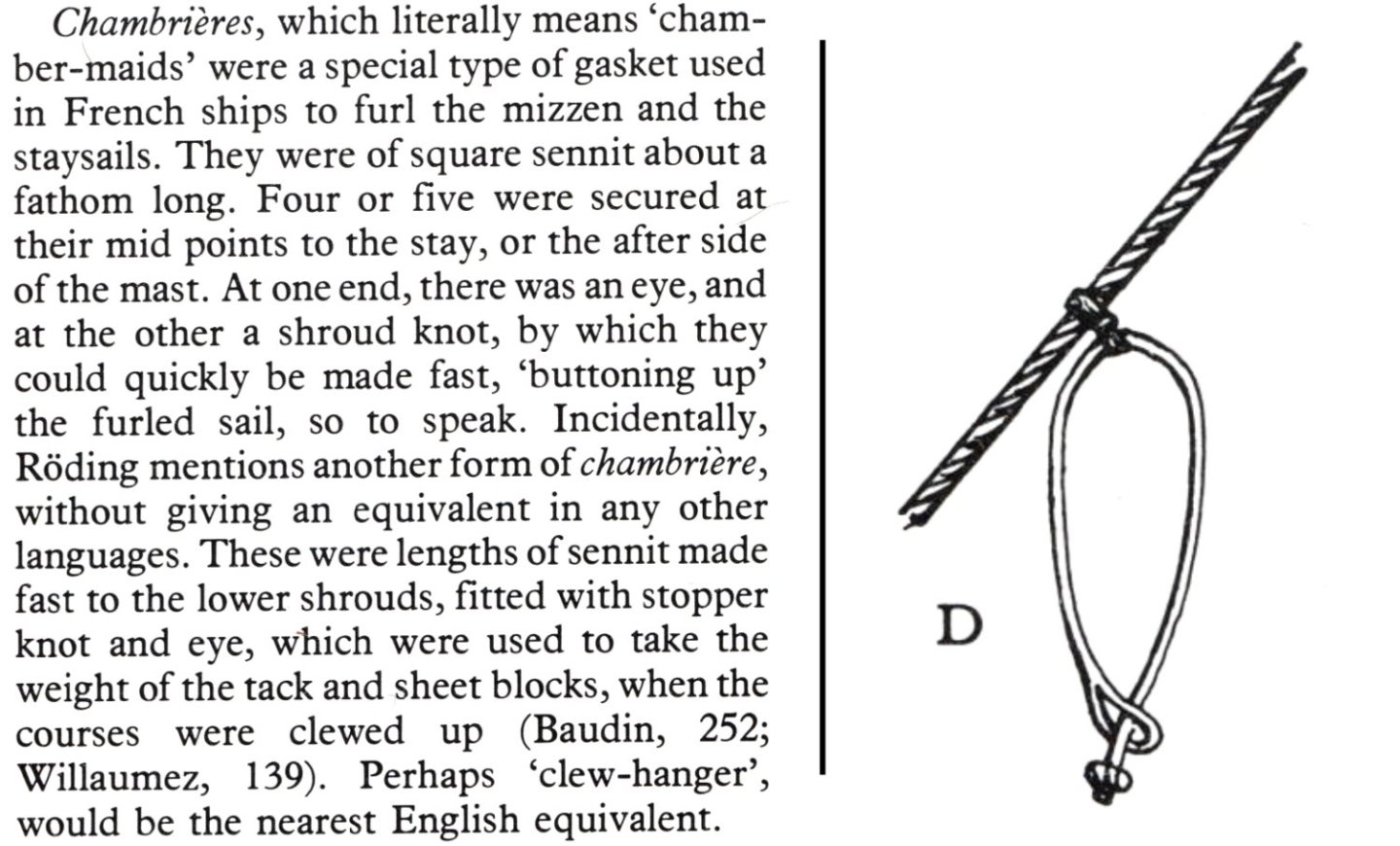

I have to admit that I was also thinking of these coils as spar ropes, or as extra protection for the yards during battle etc. I also looked into some nautical works and found something very close. Among others in Bonnefoux, Pâris, Dictionnaire de la marine à voile,1856, in van Beylen, Zeilvaart lexicon, 1985 and also in Harland, Myers, Seamanship in the Age of Sail, 1984. Below just an extract from Harland: The problem is 'only' that in the paintings the furled sails do not use these chambrières / slaglijnen at all.

-

Or should we hold a competition with prizes for solving that elusive stay coils puzzle? It often works... Wanted Double Coil Solution! Dead or Alive

-

@kirill4 Kirill, many thanks for the clarification, but it's still not enough. We need to establish the purpose of these coils in the first place. Then maybe the way they were formed will become clear. Always on the main- and forestay only, always in pairs, and always very close to the fighting tops. ???

-

Yes, and it is not just a question of stability or more generally of the ship's seaworthiness. Classic oar-powered galleys need to be proportionally very long with the smallest possible hull cross-section and at the same time of extremely lightweight construction (like today's Oxford-Cambridge racing boats, for example) in order to be effective. But in choppy waters such a structure would be torn apart in the blink of an eye. Not to mention that it is probably impossible to row effectively using dozens of long and heavy oars unisono in such less than ideal conditions. Apart from the technical considerations, I was most impressed by the descriptions of naval campaigns from the Punic Wars. When caught by the heavy seas, entire fleets with many thousands of lives aboard went bottom at a stroke, often reversing the strategic situation of the parties involved by 180 degrees. Yet, navigare necesse est, vivere non est necesse.

- 142 replies

-

I too seem to be getting headaches from these mysterious coils already. As for the actual number of rudder ropes, normally one, but that's definitely for a slightly later period. As on many drawings by van de Velde's or on the famous Hohenzollern model of 1660–1670 (shown in the two black and white photos below). But... The Vasa has two holes in her rudder evidently for this purpose, and not just one. So Landström's interpretation showing two ropes instead of only one seems reasonable too. I have included also his illustration with this feature below.

-

But perhaps we worry about it too much unnecessarily? For most of the year, the Mediterranean is as flat as a ping-pong table. Only in winter was sailing refrained from in ancient times due to frequent storms. And that's how ships were designed, just for good weather. But if they were caught by surprise by an unexpected storm, whole fleets of hundreds of ships would go down straight away... This is why the classic galleys performed so well in Mediterranean conditions, and at the same time so inadequately in the usually wavey northern waters.

- 142 replies

-

Indeed. The requirements in this particular case are so contradictory that, in order to verify the correctness of the reconstruction, I would probably require at least basic hydrostatic calculations on a mandatory basis. On the other hand, it is just modelling largely for fun...

- 142 replies

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.