-

Posts

3,156 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by trippwj

-

Nicely done, Mobbsie. She came out a beauty. Looking forward to the next one.

- 129 replies

-

- armed launch

- panart

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Welcome to deciphering 17th, 18th and 19th century "ratings"! The number of guns was meant more as a guide than a fixed rule, in most cases, and reflected the nominal armament that a ship was designed to carry. Captains, however, had some leeway in the actual arming of the ship. As but one example, the frigate Constitution was "designed" by Humphreys to carry 44 guns as the main armament. Various cruises over the years carried as many as 52 guns. There are reports that some vessels were regrettably overarmed by the Captain, resulting in poor handling and stability. At best, use the number that the hull was pierced for along the sides as a guide for the intended number of guns, recognizing that there may have been more carried as chasers or lighter guns on the weather deck that increased the count. Yep, not much help, I'm afraid!

-

Well, now. This has been an interesting quest. I have not been able to track down any easily available archeological survey information (but, that is not to say that there is none). What I have found is the following from 1977: Marsden, Peter, and David Lyon. 1977. “A Wreck Believed to Be the Warship Anne, Lost in 1690.” International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 6 (1): 9–20. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1977.tb00984.x. Endsor should have some fairly authoritative information in his book - he recently (2015) presented a fairly well attended symposium concerning the Anne. Hope this helps!

- 4 replies

-

- 70 gun

- third rate

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Bill - I haven't had the chance to check my files yet, but should have some time later today. In the interim, have you checked on academia.edu?

- 4 replies

-

- 70 gun

- third rate

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Both the CD set and the shop notes are worthwhile investments. They complement rather than duplicate each other. For me, having the "how to" tips in printed form is more practical- I can work over the guide, so to speak. For the casual, hobbyist builder (rather kit or scratch), I think the shop notes can serve a very practical, long-term purpose. I find I use the NRJ CD collection as a stepping off point for research on specific ships or topics. For me, at least, I find a well documented article with a rich bibliography more useful than pretty pictures. I use the references cited to dig back to primary sources when possible, rather than rely solely on the interpretation in the article.

-

Some, yes. Some, no. The articles are of widely varied quality (historical perspective and how-to perspective). While some of the "how-to" books are better than others, most contain useful advice. If you are concerned with absolute historical accuracy, there are no books to guide you. However, if you want to learn how to build a model, then many of the older authors offer great tips (people like Davis, McGann, Underhill, Hahn, & Longridge). They were writing for the home modeller mostly in the days before there were affordable kits. If you get one reference, get the NRG Shopnotes (okay, that would be 2 books now).

-

Let me offer a brief assortment that you may consider. This listing contains both print and PDF verswions (with open-source links where available). My suggestion is to seek out reviews on books of interest (some are more user friendly than others, some geared more for experienced builders than others, and so on). Enjoy! Model Shipbuilding Resources 20Mar2016.pdf

-

All very good resources, and most available via the interweb or used book sites. The entire series by Salisbury in MM is worth a look, if only to trace practice back to source documents. In terms of contemporary records, Sutherland (1711) offers a good description. You have me curious, sir - tell us a bit about your book, please. The brief tease you offer is tantalising!

-

There is no way to determine the actual keel length using keel for tonnage. The actual rake of the stem would allow one to determine the foremost position, but you would also need the rake of the sternpost. 3/5 max beam is an estimate of the rake at bow and stern, although the accuracy for a given vessel could vary greatly. Ideally, you may be able to find reference to length of keel "to the touch", which is total keel that "touches" the sea floor, including the rising wood. Alternatively, it could be measured from the plan.

-

I enjoy the tactile experience of books. There are many I would not consider obtaining in digital format. I also enjoy holding a print magazine or journal. I am, however, a realist. We have more than 500 books still in storage, with no space in the house for them. I like the option of obtaining magazines as PDF files for future reference. I have no space to keep printed copies. The digital spin (Kindle etc.) are not as appealing to me. Many books, sure, but not magazines.

-

Copper bottomed Baltimore Clipper?

trippwj replied to Rat-Fink-A-Booboo's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Coppering of a ship's hull was coming into common use for naval vessels during the late 18th century (I believe around 1780 for the Royal Navy). the US coppered, at great expense, our first Frigates (1794-98). As to the use of copper on merchant vessels, due to the expense it was much less common. At the period in question, the process for rolling sheet copper was still relatively new in the US (see discussion in Smith's The frigate Essex papers) and, while more metal smiths were able to make it, the physical plant required was substantial. I think our colleague Frolick hit on the answer above - if they had the money. Then copper bottomed it was, otherwise white stuff.- 6 replies

-

- copper

- hull design

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Interesting question. i suppose the answer is "it depends". If it was custom built for the purpose, perhaps - intent was to appear as somewhat innocent, confused for a merchant until in range. I suspect the level of fancy work was reflective of the owners, but no documentation I can cite.

-

Framing Math

trippwj replied to vwmiller's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Regrettably, for the time period in question, it was done as you are attempting - various reference points were marked based on some method of estimation (ratio of a to b, stuff like that, which varied over time and between designers) and then connected using splines or other similar flexible forms (not the ships curves as we know them today, but a flexible adjustable form. I appologize for not having the reference right to hand, but there is a very nice contemporary illustration available showing the tools of the trade at the time. These did not include ships curves, ducks or anything similar - just rather basic compass, dividers, squares, straight edge, and adjustable battens/bows for curves. Not the types of tools that readily converted to numeric modelling. You may want to take a look at Mungo Murray (1754), Sutherland (several editions, most published posthumously, but each very good. I prefer his 1748), and Stalkartt (1781 - a bit later than the period in question, but still relevant) to get an insight into how the naval architect of the period developed a design. Rees (1819), Steel (1794-1805) and others of that period are also quite handy, if a bit more advanced scientifically (related to displacement and resistance calculations, but still no mathematical models of the hull form itself). The use of "whole moulding" was pretty much limited to small vessels by the 18th century. There is some discussion in the 1711 Sutherland (which is repeated by many others in later publications). It is difficult to find much reference to the method prior to Sutherland. Richard Barker has several excellent articles concerning not only whole moulding but other old methods of ship design available on his website. One other item to consider - has several very nice chapters - is Nowacki, Horst, and Wolfgang Lefèvre, eds. 2009. Creating Shapes in Civil and Naval Architecture: A Cross-Disciplinary Comparison. BRILL. https://books.google.com/books?id=8FoHYXEwAXEC -

Looking at things logically, there would likely be very few actual ports on a merchant converted to privateer. The hull and deck structures were not sturdy enough to handle the number of guns required for naval service, and a privateer would do everything possible to avoid contact with a military vessel. Given the fact that the gun ports would be more for show than practicality on the privateer, the spacing could be somewhat arbitrary - to get the most present with the minimum compromise of structural integrity (remember, these were not built to the same scantlings as a naval vessel, so not nearly as many frames present, with more space between frames). You may want to take a look at the Dutchess of Manchester (while actually a snow, it is a good exemplar of a documented American merchant vessel of the timeframe). You may also be able to extract some useful information from Robinson, John, and George Francis Dow. 1922. The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607-1907. Salem, Mass. : Marine Research Society. http://archive.org/details/sailingshipsofne00robirich. Salisbury, William. 1936. “Merchantmen in 1754.” The Mariner’s Mirror 22 (3): 346–55. doi:10.1080/00253359.1936.10657196 provides a good reconstruction of several samples from Mungo Murray (1754. A Treatise on Ship-Building and Navigation. In Three Parts, Wherein the Theory, Practice, and Application of All the Necessary Instruments Are Perspicuously Handled. With the Construction and Use of a New Invented Shipwright’s Sector ... Also Tables of the Sun’s Declination, of Meridional Parts ... To Which Is Added by Way of Appendix, an English Abridgment of Another Treatise on Naval Architecture, Lately Published at Paris by M. Duhamel. London, Printed for D. Henry and R. Cave, for the author. https://archive.org/details/treatiseonshipbu00murr. ) There may also be some useful information in Chapman's Architectura Navalis, though I have not looked in there recently.

-

Masting and Rigging Spreadsheet Danny Vadas

trippwj replied to John Allen's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

I just downloaded it again (have been using it for a few years now without any problem). The newly downloaded version asked twice about enabling content - answered yes both times. Works fine for me using Excel (Office 365). Also worked fine under Excel 2007 and 2003. -

I would say the NRJ if you like how to build and how I built mine articles. If looking for historical research that actually examines the construction and so on, don't bother, you won't find it there. At best, there is a cursory history of the subject vessel before the how I built mine, but nothing like there used to be back when folks like Chapelle and his peers were contributors.

-

An interesting comparison - muzzle loading black powder guns of old had a muzzle velocity on the order of 1,600 feet per second. The 5"/54 caliber Mark 45 gun used by the US Navy has a muzzle velocity on the order of 2,600 ft/sec. 16 inch guns on an Iowa Class Battleship likewise were about 2,600 ft/sec.

-

For an interesting discussion of the history and production of pine tar (same stuff, generic name) during the day of hemp, see https://maritime.org/conf/conf-kaye-tar.htm The utility on model shrouds and standing rigging is at best marginal - the scaling of the lines (and the material used) will likely result in a change to the accuracy of the hue relative to the material. It also is potentially a source of frustration over time as it could become a great dust attractant and collector, as well as occasional liquification and dripping onto otherwise clean woodwork. I am not sure if anyone has taken samples of rigging from contemporary models to determine the nature of the compound used to obtain the tinting. Would be an interesting analysis!

-

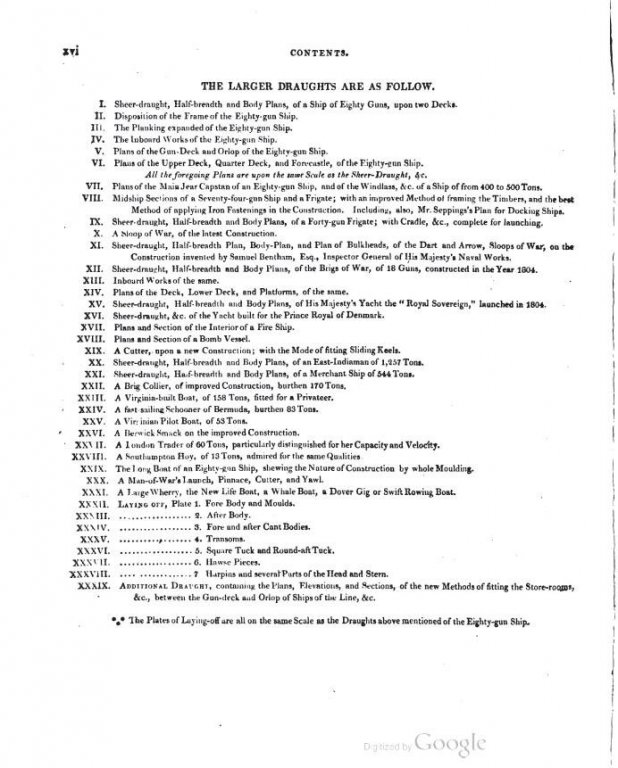

Very nice find! Here is the link (note it is the 1812 edition) Steel, David. 1812. The Elements and Practice of Naval Architecture; Or: A Treatise on Ship-Building, Theoretical and Practical, on the Best Principles Established in Great Britain. With Copious Tables of Dimensions, &c. Illustrated with a Series of Thirty-Nine Large Draughts, ... Steel and Company. https://books.google.com/books?id=TWsmw-QqvmAC

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.