Bob Cleek

Members-

Posts

3,374 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Bob Cleek

-

I can't speak to New Zealand, but here in the States the most desirable ebony is embargoed pursuant to the Lacey Act, 16 USC 3371-3378. "Gibson Guitar Corporation was raided twice by federal authorities, in 2009 and 2011. Federal prosecutors seized wood from Gibson facilities, alleging that Gibson had purchased smuggled Madagascar ebony and Indian rosewood.Gibson initially denied wrongdoing and insisted that the federal government was bullying them. In August 2012, Gibson entered into a Criminal Enforcement Agreement with the Department of Justice, admitting to violating the Lacey Act. The terms of the agreement required Gibson to pay a fine of $300,000 in addition to a $50,000 community payment, and to abide by the terms of the Lacey Act in the future. For violating the Lacey Act, Lumber Liquidators was sentenced in 2016 to $7.8 million in criminal fines, $969,175 in criminal forfeiture and more than $1.23 million in community service payments for illegal lumber trafficking. The sentence also included five years of probation, and additional government oversight. The U.S. Department of Justice said it was the largest financial penalty ever issued under the Lacey Act. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lacey_Act_of_1900

-

Edge Gluing Planking

Bob Cleek replied to Neil10's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Your mileage obviously varies. In my experience, properly seasoned and heat-bent wood will stay where it is put within normal ambient humidity variations. Those variations are also greatly dependent upon the species of wood involved. (Museums are full of old models that are proof of this.) As a matter of science, the smaller the piece of wood, the less it tends to shrink and swell with changes in moisture content. It is absolutely true that in single-layer monocoque wooden hull construction "If the planks are glued to each other, all stresses are shared by adjacent planks and the movement is also shared." From an engineering standpoint, however, those shared stresses will always need to go somewhere. When movement, as contrasted with stresses, is evenly distributed throughout the structure, such as a wooden hull, the movement is often imperceptible, being relative to the entire structure. The inherent flexibility of most paints and varnishes will accommodate this distributed movement rather well. Even in the extreme environment to which a real wooden vessel is exposed, a good quality paint job over a quality built planked hull will not "show her seams" for a good long while. A model which is properly cared for has no problem at all in this regard. On the other hand, when movement is consolidated by gluing all the parts together, the stresses, will "seek the path of least resistance" and the "weakest link" principle comes into play. Where the glue is stronger than the wood itself, which is the case with many modern adhesives, this can result not simply in one big glue-line failure, but in the actual splitting of a piece itself. This problem is endemic in "strip planked" full size hulls, which is why that construction method places so much emphasis upon resin sheathing to isolate the wood structure from moisture. By the same token, the stresses from movement of the wood structure when a model is built of properly seasoned and bent wood of a suitable species and property exhibited and stored should be insufficient to cause any significant damage to the model, so there's no great harm likely to be done by edge-gluing planks if one is so inclined and not bothered by the inherent drawbacks of the process. If you want to do it your way, go for it and good luck! -

No difference, really. Just remember you can paint oil-based paint on top of acrylics, but not acrylics on top of oils. Paint manufacturers long ago discovered that if they created the impression that one had to use primer, they could sell twice as much paint to people who didn't know whether they needed to prime a piece before painting or not. The fewer coats of anything that you put on a model, the less detail is lost and the better the scale impression will be. (Ideally, you want the thickness of your paint coats to be "to scale" too!) I don't use primer unless I need it to make my finish coat cover with less coats or to make incompatible coatings adhere. If I don't need a primer, I don't use one. The fellow in the video wasn't using primer on his plastic plane model because he was using oil-based enamel which sticks to plastic well. He probably would have used a primer on it if he were using water-based acrylic paint because the water would tend to bead up on the slick plastic surface. Oil doesn't bead up on slick impermeable surfaces like water does. Primers have a variety of purposes. One essential purpose of a primer is to serve as an intermediate coating between two surfaces and/or coatings that aren't compatible. (Hence the market term: "Universal Primer," of which dewaxed shellac is one of the best.) When two non-compatible coatings must be applied one on top of the other (which one ought to avoid in the first place,) a "universal" primer compatible with both oil and water-based paints creates a common surface that "sticks" the two together. Primers are also useful for creating a uniform base color, particularly when successive colors aren't likely to cover as well as you'd like. A highly-pigmented primer coat in a neutral color is much easier to cover with a finish color coat than an unevenly colored surface. Finally, "sanding primers" contain chalk which makes them easy to sand. If you have a rough surface, a sanding primer or "basecoat" is easier to sand to perfect smoothness than finish coats. Bare wood requires a "sealer," which some incorrectly call a "primer," although a first thinned coat of paint or varnish can often serve double duty as a sealer. The purpose of a sealer is to seal an absorbent surface, such as bare wood, that would otherwise soak up the finish coat paint unevenly, requiring additional finish coats and likely more sanding. I seal all my wood with thin shellac. ("Out of the can," which is two pound cut shellac, I'll add 25 to 50 percent alcohol to thin it well.) I keep the thinned shellac in a jar and often simply dip small pieces into the shellac and then shake off the excess. It soaks into the wood and dries very quickly. (And faster if you blow on it.) The alcohol evaporates quickly. This provides a "hardened" wood surface for final fine sanding and an impermeable surface for applying paint so the paint won't soak into the wood unevenly and leave "rough spots." When you see close-up photos of models on the build logs that look like the parts were cut with scale-sized dull chainsaws and painted with a an old rag on a stick, they haven't been sealed and sanded before painting. (The unsightly finish is less noticeable when viewed with the naked eye, of course.) Yes, artists' oils will take seemingly forever to dry because they contain no driers. Oil paint is made up of a pigment, the color material, and a binder, an oil that cures and hardens so the pigment adheres to the surface that's painted. The oil, often "raw" linseed oil (which can be purchased in food-grade as "flaxseed oil" in health food stores for much less than in art stores,) polymerizes over time and becomes hardened. Artists often blend color for various effects right on their canvases and a slow drying paint is desired by them. "Boiled" linseed oil (which isn't boiled at all) contains added driers, usually "Japan drier," which accelerates the polymerization of the oil binder. Adding boiled linseed oil to artists' oils will cause them to dry more quickly, or one can buy "Japan drier" and add small quantities of that to artists' oils (or any other oil paint) and that will cause it to dry more quickly. How quickly is a matter of "feel" and experiment and tests on scrap material should always be conducted before applying mixed paint to the model itself. Oil paint will dry with a glossy finish if there's enough oil in it. Thinning tends to dull the finish, but sometimes not enough to achieve the flat finish required on scale models. To achieve a flat finish, a small quantity of "flattening agent" may be added. This can be purchased wherever artists' oils are sold. Grumbacher makes the industry standard "flattener." Japan drier is a mixture of 3% cobalt in naptha. Linseed oil is simply linseed oil, a natural vegetable oil. Gum turpentine is simply refined tree sap. While I am no fan of climate change, one unfortunate consequence of many environmental protective regulations is that they too often attack the "low hanging fruit" and not the larger causes of the problem. Despite the relatively limited environmental impact of releasing oil paint related organic solvents into the atmosphere, oil based paints and solvents which contain high amounts of "volatile organic compounds" or "VOCs," are no longer allowed to be sold in some jurisdictions, notably in the U.S. in California. (Hence the "Not available in California" notations in many mail order catalogs these days.) There are a few exceptions to these regulations, generally involving packaging amounts. Linseed oil, Japan drier, and gum turpentine can still be obtained in small amounts at ridiculously high prices when sold as art supplies, but you'll have a hard time in many areas finding quart cans, let along gallon cans, of stuff like turpentine, linseed oil, mineral spirits paint thinner, naptha, tolulene, and the like. In times past, these substances were staples for anybody who knew what they were doing and did any amount of painting. Now, if you find yourself in a area where they've become unobtainable, you have to resort to "smuggling" your supplies from outside the areas where they are banned or pay the huge premiums charged for the ounce-sized containers in the art stores. For those who wish to use acrylic paint, tubed acrylic artist's paints are readily available, of course. They are, however, acrylic paint and, like just about everything that "mother" tells us is "safe and sane," they are no fun at all. Those of us who were building models before about 1980 mourn the loss of "real" model paint like the legendary Floquil, which was so "hot" (full of aromatic hydrocarbons) you could get a buzz on using them. They worked perfectly every time right out of the bottle. Sadly, with their demise, modelers wishing the same results today have to teach themselves how to mix and condition their own paint.

-

Black ebony is nearly commercially extinct at this point. Pure black ebony only comes from the heartwood of very old trees, most all of which are now gone. What little is available is not pure black and full of checks and voids. Real ebony is very oily and presents challenges when gluing. The prices are astronomical. Ebony is also subject now to various national and international import bans. Some nations will not permit the importation of items made of ebony without acceptable documentation of the age of the wood being prior to the effective date of various endangered species laws. This has caused a lot of musicians with instruments containing ebony and rosewood a lot of grief when they try to bring their instruments into a foreign country to play at concerts. Your only real option is to take another species and stain it black. Some old modelers have stashes of ebony and real European boxwood, but good luck trying to find any on the retail market these days.

-

Edge Gluing Planking

Bob Cleek replied to Neil10's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

I can't imagine why anyone would have any need to edge-glue planking at all. It adds nothing structurally and creates a lot of messy work. Properly spiled and bent plank should easily lay fair on the frames or bulkheads and glue at the faying surfaces between the frame or bulkhead and plank face should be more than adequate. A plank which has to be forced into place isn't done right. Do watch Chuck's videos to learn how it's done correctly. You'll be glad you did. -

Even to this day, stern-in "med-mooring" is common practice in Mediterranean ports. Many local vessels carry a gangplank for the purpose.

-

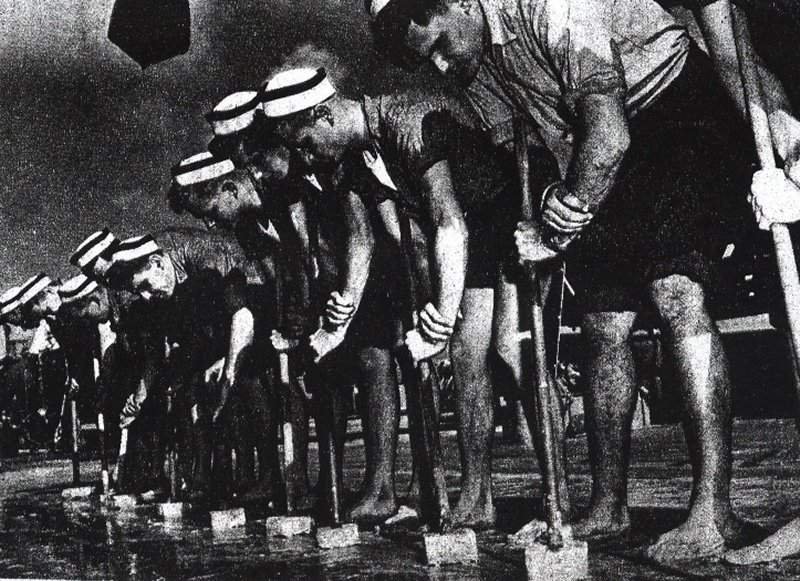

I appreciate the work you've put into your approach, but, as allanyed mentioned, there are specific butt shift patterns which are distinctive to the construction method of vessels and periods. Your "every other plank" butt placement is glaringly incorrect to a knowledgeable eye. Similarly, deck planks are always fastened with trunnels (wooden pegs) or with metal fasteners which are countersunk with the holes plugged with wooden plugs. No bare metal is visible on the deck surface. Wooden decks were regularly holystoned (sanded with abrasive stone blocks) to keep them clean and free of tar. Protruding metal fasteners would prevent holystoning. In fact, at scale viewing distances, deck plank fastening pegs or plugs would be invisible on a real planked deck. Portraying them on models at most scales is greatly out of scale. I could have passed on this comment, but as you posted this as a tutorial, I felt it might be helpful to some to note the discrepancies. Depicting deck plank fastenings of contrasting colors in scale models seems to be a matter of taste with many modelers, and if it satisfies them, that's their choice, but it does not create an accurate impression of the prototype.

-

Converting a Backyard Shed into a Model Workshop

Bob Cleek replied to Hank's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

"Powder horn values range widely depending on condition, type of carving, and market conditions. A simple piece containing a name and date could be worth a few thousand dollars, while intricate examples with historical engravings have been valued at $30,000 or more." https://www.invaluable.com/powder-horns/sc-UVH6H0R6BL/ See: https://www.pbs.org/video/antiques-roadshow-appraisal-1849-ohio-carved-powder-horn/ -

Converting a Backyard Shed into a Model Workshop

Bob Cleek replied to Hank's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I'd suggest you have that 1850's powder horn appraised if you haven't already. -

Lovely model, Roger! I'd say a great example of "understated elegance." The original poster was specifically asking about finishes applied with a brush, so I didn't mention spraying. I'll say this about that... I do a lot of spraying and, for a long time now, even more spraying than brushing, especially on "the wide open spaces." I use my trusty old Badger double-action airbrush. I would never approach a model with a "rattle can!" I hate them. They are expensive in original cost and more often than not, they crap out before they're empty. And more importantly, they're risky, since, for me, at least, I never know when one is going to start spitting and sputtering and ruin an entire finish job. I do my spraying as a model is built, paying attention to masking schedules and accessibility. While the model you have pictured is somewhat unusual in its lack of detail and bright finish throughout, which lends itself to spraying the whole model when complete, you're a more daring man than I, shooting the entire finished model as you did. I'd be afraid I would never get a sufficiently even application with a gun. How did you ever get the hard-to-reach places done? I'd never be able to get the "innards" coated evenly without getting too much build up on the outside of the framing. Congratulations on a job well done !

-

Paint should be thinned to about the consistency of milk, or even thinner in some instances. If you are experiencing brush strokes and runs, you are applying the paint too thickly, either because your brush is overloaded, your paint is too thick, or both. Repeated thin coats should "lay down" without any brush strokes or runs whatsoever. Keep applying until the coat is even and covers fully. This can sometimes take several coats. The goal is to cover the surface adequately with the least amount of paint build up. For sanding between coats, "less is more." Many sand so aggressively that they remove the coat they just put on! A properly prepared surface, with paint properly applied, should require very little sanding. 120 grit is way too coarse. You should be using 400 to 600 grit, and sparingly at that. If you've painted properly, you shouldn't have much more than a speck of dust here or there on the surface that you need to remove. Paint needs to be "conditioned" before use. They aren't generally intended to be applied "right out of the can." Conditioning generally involves interdependent processes: 1. Thinning: this involves adding the thinning solvent to the paint from the can to get the thickness of the paint adjusted. 2. Retarding: this involves adding a "retarder," generally more of the oil "binder" to the paint. This will slow the drying of the paint, which permits brush strokes to "lay down" or "level" naturally. 3. Accelerating or drying additives: this involves adding "Japan drier," or other additives which accelerate the drying time of the paint. This is only necessary when mixing your own paint using tubed artists' oil paints, which generally do not contain driers to begin with. Decent brushes are a worthwhile investment. When using oil-based paints, you should use natural bristle brushes. Synthetic bristle brushes are for water-based paints. Use the largest brush you can for a job. This allows you to easily maintain a wet edge as you paint. You don't want to be running a brush back over paint which has started to dry. Don't rush. Multiple coats are better than fewer thick coats. Painting is an acquired skill. The more you do it, the better results you will achieve, although there can always be surprises, so be sure to test your conditioned paint first on a scrap piece. YouTube has many video tutorials on painting models and miniatures. This guy's series, although addressing plastic aircraft models, is fairly good:

-

A lot depends upon the type of wood you're planning to finish bright (clear.) If the wood has open grain, it will be difficult to finish bright and obtain a smooth finish without considerable filling and that filler will have to match the appearance of the wood, which can sometimes be tricky. When finishing a model, "less is more." Others may have a different opinion, but I am not a big fan of clear acrylic or polyurethane finishes for models, although they are great for finishing bar and table tops. That said, some claim good results using thinned polyurethanes (sometimes marketed pre-mixed as "wipe on polyurethane.") If you plan to apply a finish with a brush, you will have to apply a very thin coat, or coats if you want to avoid brush strokes, puddles in the corners, and overall loss of fine detail. Because models are viewed up close, the finish must be perfect if the artistic impression of the model is to be effective. Assuming the wood that is to be finished bright is a suitable species (i.e. a closed grain "finish" wood, such as pear, boxwood, ebony, or the like,) I would opt for a thin coat of clear shellac, hand rubbed with fine steel wool and/or pumice and/or rottenstone after drying, if necessary. If the surface is well prepared and perfectly smooth, the thin shellac should soak into the wood well and little, if any, hand-rubbing should be necessary. If, after that, the surface appears a bit too flat, I'd apply a light coat of Renaissance Wax. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renaissance_Wax If the wood species isn't suitable for fine clear finishing, I would not finish it bright, but would fill it in the usual way and paint it. As the saying goes, "You can't polish a turd."

-

‘Universal’ Primer

Bob Cleek replied to CTYankee's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Zinsser's "Universal Sanding Sealer" (de-waxed shellac) is a different product from plain shellac. I've never used it, but according to their product description, the removal of the natural wax from the shellac in this product permits this coating to adhere well to previously coated surfaces. Like any product with alcohol used as a solvent, it's applied to alcohol-soluble coatings, it will soften the coating beneath it, of course. I only use shellac as a sealer on bare wood. I sand smooth and apply a single liberal coat of shellac, which soaks into the wood. When the shellac is dry, I give the surface a final sanding with fine grit sandpaper, and then apply paint over the surface, or if the wood is to be left bright, I just leave it without any further coating. See: https://www.rustoleum.com/product-catalog/consumer-brands/zinsser/interior-wood-finishes/sealcoat-universal-sanding-sealer/ -

‘Universal’ Primer

Bob Cleek replied to CTYankee's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

The color range of natural shellac runs from orange which, with multiple coasts, will appear dark brown. Shellac flakes are bleached to achieve varying darknesses ranging from "clear" on up. You can obtain flakes from mail order houses and dissolve them in your own alcohol, but buying premixed "two pound cut" shellac in quart cans is cheap and easy. (Most paint and hardware stores carry it. In the US the brand is Zinsser "Bulls Eye.") It comes in two types, "orange" or "amber" and "clear." For modeling purposes, the clear is what you want. If you wish to thicken it, simply take some out and let the alcohol evaporate. To thin, just add more alcohol. A quart should last you a long time. Brushes clean up with alcohol. I store my used brush cleaning alcohol in closed containers and start washing a brush by rinsing in the "dirtiest" jar of alcohol, then move to another that's a bit less dirty, and finally rinse in a jar of clean alcohol. As the alcohol in the jars gets progressively dirtier, it gets moved into the "next dirtiest" jar. I use the "dirtiest" used brush cleaning alcohol for adding back into the can of shellac to thin it as needed, or even, if there's enough shellac dissolved in it, I use it for when I want very thin shellac. You save a lot on alcohol that way and don't waste shellac, either. One can also always leave the "dirty" jar of brush cleaning alcohol open for a day or two and let the alcohol evaporate and yield shellac of a desired thickness. Shellac that is "molasses" consistency is sometimes used to good effect as an adhesive. Dried alcohol is easily removed by simply washing with alcohol. Shellac permeates the wood surface and does not produce brush strokes or raise the grain. It dries flat on bare wood, but with multiple coats, will build to a gloss finish. It sands easily to a very smooth surface. Shellac is an archival material. Three thousand year old shellac covered artifacts in good shape have been found in Egyptian tombs. And it's really cheap compared to other coatings on the market. It's non-toxic (aside from the denatured alcohol it's mixed in. Shellac is what is used to coat jelly beans to make them shiny. What's not to like? Shellac contains a natural waxy substance that supposedly interferes with the adhesion of polyurethane and water-based (acrylic) coatings, although I've never encountered any problem applying oil-based finishes over dry shellac. If one is concerned about this, Zinsser also sells "SealCoat," a "dewaxed" shellac for use beneath polyurethane and water-based finishes. "SealCoat" is advertised as a "universal sanding sealer" for this reason. (Don't waste your money buying shellac in a rattle can. If you don't want to pay sixteen to eighteen bucks for a quart, you can buy a half-pint for ten bucks.) See: https://www.rustoleum.com/product-catalog/consumer-brands/zinsser/interior-wood-finishes/bulls-eye-shellac/ -

No matter how you cut it, cutting the rolling bevel in a planking rabbet (sometimes called a "rebate") is a tedious process that takes some thought and care. You will find lots of theoretical instructions in boat building and modeling books about how to do it using the information that may be developed using lofting techniques. The exact angle of the rabbet can be developed for any point along the rabbet's length from the lofting (or lines drawings) and from that the rabbet, back rabbet, and bearding lines can then be developed and drawn or lofted. These varying angles define the shape of the rolling bevel that forms the rabbet. In small craft and model construction, there's an easier way to cut the rolling bevel without reference to the drawn or lofted the rabbet lines at all. Experienced boat wrights dispense with a lot of the lofting by "building to the boat," as they say, rather than "to the plans." With the planking rabbets, this means that the angle and depth of the rabbet at any given point along the rabbet is developed using "fit sticks" and battens to define the rabbet lines and the bevel's rolling angles. It's easier done than said. What you do is frame out your boat or model. Take care, as is always necessary, to fair the frame face bevels. This requires setting up the frames and sanding the faces so that a flat batten laid across the frames in a generally perpendicular relation to the frames, as well as at lesser angles, will always lay flat against the frame faces. (You may need to place temporary blocking between the frames or otherwise secure them well so they don't wobble when you sand across them.) Your frames should be cut and set up as in full size practice, with the corner of the outboard-most side of the face precisely cut and set up on the section lines such that when fairing wood is removed from the forward side of the faces of frames forward of the maximum beam and from the after side of the faces of the frames aft of the maximum beam. The accurately cut frame corner, the forward corner on frames aft of the maximum beam and the aft corner of frames forward of the maximum beam, is the reference point for fairing your frames. Use one batten for marking the faces of the frames and another, with a suitable sheet of sandpaper glued to its face, or a manicurist's emory board, to sand the excess off the faces until they are fair. The batten used for marking is chalked with carpenter's chalk and rubbed against the faces of the frames to mark the high spots. Where the colored carpenter's chalk transfers from the marking batten to the frame faces is where the frame face is too high and needs to be sanded down some more. When the marking batten lies flat in contact with all the frame faces, transferring chalk to the entire frame face, the frame faces are fair. Now, with your frames faired, take a small stick of wood the same thickness as your planking and cut across at the ends perfectly square, which is called a "fit stick," and place it against the face of a frame and slide it down until the lower back corner of the fit stick (the inboard corner) rests against the keel. Accurately mark the point where the corner of the fit stick and the keel meet. This mark is where your bearding line is at that point. Then take a second fit stick and place it on top of the first with the first in the position it was in when you marked the bearding line point and slide it down over the first fit stick until its lower back (inboard) corner touches the keel and mark that point. This mark is where your rabbet line is at that point. Make these two marks at each frame. Spring a batten between all the upper and lower marks on the keel and draw lines through all the marks. These lines will be your bearding and rabbet lines. Extend them out as far as they will go, but, for the moment, they are relevant only for the span from the forward-most frame to the after-most frame. Now, at each frame, with your two fit sticks stacked as when you marked the lower rabbet line, take a knife or chisel and using the lower edge of the upper fit stick as a guide, cut into the keel at the same angle as the face of the bottom edge of your upper fit stick, i.e. with the flat of your blade against the edge of your lower fit stick. This cut should be as deep as your planking is thick. (This first cut can be easily made with a small circular saw blade on a rotary tool if you know what you're doing. Mark the blade face with a Sharpie to indicate the depth of cut.) Cut down to the point of the rabbet cut you've made from above so that you end up with the back rabbet face of the keel at a right angle to the rabbet line cut. Test your cut with a fit stick, which, when the rabbet section cut at that frame is done, should lie perfectly fair on the face of the frame with its bottom edge fit perfectly into the rabbet you've cut. Because the angle of your rabbet is defined by the lower edge of the top fit stick and it's depth by the thickness of your planking, there's no need to worry about where the back rabbet line is. You'll develop the back rabbet naturally when the two lines you are cutting to meet at right angles at the bottom of the cut. Now, you simply "connect the dots" or rabbet "notches" you've created at each frame by carving out the wood in the way of the rabbet and bearding lines between the frames to form a continuous rabbet with a fair rolling bevel. The stem, deadwood, and stern post are a bit trickier than the sections where the frames are set up on the keel, but the method of marking them and taking the rabbet angles off of fit sticks is the same and shouldn't need much further explanation. The main difference is that a batten of the same thickness as your planking is place across the frame faces, rather than perpendicular to the frame faces, and extended to where its bottom inboard edge touches the stem, deadwood or stern post and is marked there for the bearding line, and then another fit stick batten is placed on the first to find the rabbet line. You will find a chalked marking fit stick batten to be handy again in fairing up the dubbing on the wide deadwood rabbets. These techniques are a lot easier to learn by doing than to explain in writing. On a real vessel, cutting the planking rabbets is a very exacting process because the ease of caulking and the watertightness of these seams are dependent upon the perfect fit of these faying surfaces (where the planks and keel touch.) This isn't a big consideration in a model. What's important for a model is only that the visible rabbet lines and the planking are fair and tight. If the angle is off behind the planking and a bit too much wood is removed, it makes no difference because a sliver can always be glued in place to raise the plank to where it has to be and the rest filled with glue, or if too little is removed, the plank face can be sanded fair after it's hung. (The latter being the less preferable. It's generally better to remove wood from behind the plank than from the plank itself.) This may seem like a tedious exercise and it is, but doing it correctly will make your planking a far easier task, particularly in hull forms where there is considerable twist in the planks at the ends. A final word of caution for the modelers with a machinist's background: This is a hand job. You won't find a way to do it more easily on your mill. Many have tried to devise some sort of jig which would permit cutting these rolling bevel rabbets with saws, routers, or other power tools. As far as I know, and those I know who know a lot more about it than I do, nobody's succeeded. Don't waste a lot of time trying to figure out what nobody else has been able to accomplish. I expect that it could be accomplished, in theory, at least, with very sophisticated CNC technology, but would probably take a lot longer to program and set up than doing it by hand will. This video of full-sized construction illustrates the method described fairly well:

-

The fingers are more reliable "blemish detectors" than the eyes in any event. If it feels smooth, it is smooth. Sealing wood with shellac prior to a final fine-grit sanding, and then the use of a tack rag before painting, will go a long way to avoiding specks and blemishes that the eye cannot detect.

-

Tips on rigging small ships

Bob Cleek replied to DispleasedOwl's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

What you are asking about are called "bolsters." (See diagram below.) They are simply pieces of wood fastened to the side of the mast which keep the strop from sliding down the mast. You should fashion them from wood and glue them to the mast where you want them, but then drill two or three small holes through the bolster and into the mast and glue small wooden pegs (made with a draw plate) into the holes and sand the top of the peg flush with the face of the bolster, or, alternately, glue a brass pin in the drilled hole, set slightly deeper than the face of the bolster, and fill the top of the hole with a bit of putty and sand fair with the face of the bolster. The pins are necessary to make sure the bolster will be able to stand the load when the rigging is under tension. Glue alone may not be sufficiently strong to do so. The strops are made up separate from the mast "on the bench" and then installed by sliding them over the top of the mast and down onto the bolster when the mast is rigged. This will require your planning the sequence of setting up the standing rigging so you can get the shrouds and stays over the mast in the correct order. It's generally easiest to rig as much of a mast or spar "on the bench" before installing it on the model, because it is far more difficult to do the work if one has to do so when the mast is erected. Your kit may have provided the eye-bolts you have pictured on the mast about. The pictured eye-bolts are are grossly over-sized and out of scale. If your kit's eye-bolts are out of scale, as is often the case with kit parts, I would urge you to replace them with eye-bolts that are properly scaled. The ones pictured are at least two or three times as large as they ought to be. They also lack mast bands. (See diagrams, lower left, above.) In real life, these eyes would be part of a metal band set around the mast, not eye-bolts simply screwed into the mast. The mast band is a much stronger fitting. Mast bands can be simulated in modeling by gluing a thin strip of black paper around the mast, then drilling holes through the paper band and into the mast and gluing the eyes into those holes. This video on making your own eye-bolts may be helpful to you. -

That's a treasure! Photos, please! I'd love to hear the story of how you came by it. Is it the large "builder's model" or one of the models made for use in the travel agents' office windows? ("Travel agencies..." now there's another trade that the internet has pretty well obsolesced into oblivion.)

- 11 replies

-

- president cleveland

- ocean liner

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

What Canute said. Stain penetrates the wood, so if shellac seals the wood, stain can't penetrate it. One of the problems to note about staining is that the stain has to be compatible with whatever coating you apply over it, as well. I don't want to start a big controversy here, but I can't resist offering my two cents' worth. I'm not a fan of staining on models. There are some times when it might be indicated, on spars, perhaps, or possibly laid decks, but the simple fact is that the real purpose of stain is to make one wood look like another and, like most faux finishes, it may come close, but never hits the mark completely. Stain enhances the figuring of some woods, which is good for furniture, but since there aren't any woods that have grain features that are to the scale of most any model, enhancing the grain of wood on a model is the last thing a modeler should want to do. Some like to portray their models "au natural," without any paint. This style best exhibits the exact construction features of the prototype and the skill of the modeler, with each faying surface highlighted in black and every fastening in its proper place. In that case, the best approach is to use a fine finish wood species that serves the purpose and looks well clearly sealed or lightly oiled or waxed. If it's the beauty of bare wood you want, there's so little wood in a model that there's no reason not to buy the good stuff and show it off. Staining basswood is like trying to polish a turd. And I'll mention in passing that "wipe on poly" is a rip off. It's just polyurethane varnish that's been thinned, canned, and marketed to consumers who don't know the difference. Thinner is relatively cheap. Buying thinned varnish and paint for the same price as the thick stuff is a waste of money. Thin your coatings yourself and save a bundle.

-

Just what Thunder said. Today's bottled modeling paints, particularly the acrylic "water based" types, are the result of complex chemistry and there is a lot that can go wrong with them, especially when they are combined with other types and brands. Acrylic water based paint often does not adhere well, if at all, over oil based paints, while oil based paints will adhere to acrylics. Under coats are sometimes incompatible with finish coats. While dried pigment generally appears darker than wet pigment, colors may, upon drying, appear different in unanticipated ways. If paint ages in the bottle, it sometimes won't perform as expected. Using the wrong thinner or conditioner, which works for one brand and not another can cause problems, too. A common malfunction occurs when paint doesn't dry, or in the case of acrylics, "cure" fully and remains tacky to the touch. The only cure for this problem is to remove the paint completely and start over. That's a terrible, nasty, messy job. You don't want to have to go there ever. So, the moral of the story, at least until you are completely certain and comfortable with a particular coating, is to test it first on a piece of scrap material or, as the professional painters call them, a "chip." That "paint chip" gives you a preview of how that paint will perform. If it doesn't perform as you require on the chip, you've lost nothing. On the model, it's another matter entirely. These chips are also worth saving, with any helpful information written on the back with a Sharpie pen, such as the brand and color and they type of thinner and/or conditioner used. Other colors can be applied over a section of a chip as well, and this will provide information on how well that color "covers" and what it will look like when dried on top of the earlier coat. This practice comes in very handy if and when you graduate to painting with an airbrush, which is more demanding of properly conditioned paint than brushes are. I'll pass on writing an entire dissertation here on conditioning paint, but suffice it to say that it is a rare bottle of paint that contains paint ready for use "right out of the bottle" or can. Environmental factors such as temperature and humidity affect the behavior of paint to greater or lesser degrees depending upon the paint, oil or water based. (You will probably end up preferring one or the other. I prefer oil based paints and often use fine arts artists' oil paints sold in "toothpaste" tubes from art supply stores, which I condition to my own taste. Your mileage may vary. "Dance with the gal ya brought.") These conditioners create the characteristics of the paint. Thinners simply are solvents (or water or alcohol with water based acrylics) that make the paint thinner. Thinners can also contribute to the "flattening" of glossy paint, a desired effect for models, which should not be finished glossy because gloss is out of scale. "Flatteners" will also flatten glossy paint. The more you add, the flatter the paint gets. Other conditioners will improve the "flow" of the paint, basically slowing its drying time, so a brush won't "drag" and a "wet edge" can be maintained more easily. Paint that "flows" well will also "lay down" easily and brush strokes will disappear as the paint "levels." Too much, on the other hand, can cause paint to sag and create drips and "curtains." Driers, often sold as "Japan Drier" in the case of oil paints, contain heavy metals which speed the drying of the paint, the opposite of conditioners that improve flow. On hot days with low humidity, you will add conditioners to slow the rate of drying, while on cold days with high humidity, you'll add conditioners to speed up drying. These skills become even more important when airbrushing and spray painting because the atomized sprayed paint has to hit the piece before the solvents kick off, and then lay down before drying to achieve a perfectly smooth finish, yet not be so thin or retarded (slowed down) that they run or "curtain" after being sprayed. (And if you are of a mind to spray paint, forget the rattle cans and go for an airbrush. It will pay for itself over the rattle cans, which always seem to crap out while they're half full and never really give the same control or results.) You need to also remember that wood has to be sealed before painting so the paint won't soak into the wood and produce an uneven coating. I use shellac for this because it is easy to work with, dries fast, is economical, soaks into the bare wood well, is compatible with all other coatings when dry, and sands very nicely to a very fine smooth finish. This may all sound a bit overwhelming at first, but it's not rocket science. If you're lucky, you'll find somebody who can show you how it's done and you'll be on your way. It's a lot easier to learn by watching somebody do it than it is to learn it out of a book. Experiment a little and get the hang of it, but, most importantly, practice and learn on scrap pieces before starting to slap paint on a model you've spent a lot of time on. That will save you a lot of grief. This fellow seems to have a pretty good video on the subject.painting miniatures.

-

When and what to paint really depends upon the progress of the build. Generally, apply finish coatings when it is easiest to do so. It's surely easier to paint separate parts and then secure them to the model if that avoids having to mask or carefully cut in edges. If a hull has a lot of "attachments," it's often much easier to finish the overall hull coatings first and then add the attachments because you'll be sanding "wide open spaces" and not having to sand around edges and corners (which you don't want to round off with sandpaper, anyhow.) Bottom line, "use your own judgment." As for protecting finished work, here again, common sense prevails and discovering solutions is part of the joy of the hobby. I often find using those foam insulating split tubes they sell at the hardware store to keep pipes from freezing or to insulate hot water pipes under houses is a good way to protect finishes during construction. They can be cut up in sections and several sections taped together at the ends with duct tape to form a "cradle" that will hold a model hull upright and secure without marring the finish on the hull. You will often read that parts should best not be glued to finish coated surfaces and that's generally sound advice. That said, however, many of us hew to the traditional US Navy contract ship model "mil-spec" requirements and always mechanically fasten parts on our models, most often with a peg glued into a drilled hole or similar. This practice renders the "don't glue to painted surfaces" advise irrelevant and also eliminates most all problems with adhesives letting go. Finish coatings are an essential feature of a well done model and developing the skills necessary to do a good job does present something of a learning curve, even for a somewhat experienced painter. You'd do well to try to find some instructional videos on the subject and study up on it before you start painting your model. YouTube is full of videos on painting models. Don't just look for ship models. Some of the best are done by the military equipment modelers and the fantasy gaming figure modelers. Painting any miniature is all pretty much the same, but it isn't the same as painting a house! Finally, one bit of advice that few new painters learn out the easy way. Always try out every coating you are going to use on a similar surface other than your model and on the test piece determine if the paint's consistency, "leveling ability," and drying time, etc., are as you intend them to be. If we had a dime for every post that started, "I've waited a couple of days after painting my hull and it's still all sticky and not dry..." we'd be rich people today. Learn to condition your paint and always test it first on a scrap piece of material ! (And save those scraps in case you want to paint over it later, too. That's the way to make sure that a later coat is compatible with the earlier one ! )

-

I certainly hope your decision to sell your modeling books and other items isn't the consequence of some personal misfortune! If you are selling it all, please do post what you've got and what you hope to get for it. Many of us are interested in adding to our own collections. The opportunity to purchase used books at reasonable prices is always welcome!

-

BUYING A "PAINT SET"

Bob Cleek replied to MadDogMcQ's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Some purists reportedly still use dry pigments, but preparing them for use is a time-consuming laborious process. The pigments must be mixed with the oil binder in suspension in a process called "mulling." (From whence the phrase, "mull it over" is derived.) (See: https://www.scribalworkshop.com/blog/2019/6/5/mulling-paint-a-beginner-ish-guidef ) Pigments are often minerals as well as organic materials. The difference between oils and acrylics is in the binder, not the pigment, as far as I know. Colorfastness is a sought after quality in good paints and the "chemical dyes" can suffer in this regard. (Here's an interesting site about pigments: http://www.webexhibits.org/pigments/intro/pigments.html) -

BUYING A "PAINT SET"

Bob Cleek replied to MadDogMcQ's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Currently, it seems the "fantasy figure" modeling and gaming community seem to have discovered artists' oils and are using them more widely than any of the other modelers. In times past, the top professional ship modelers always used artists' oils. As a painter, I'm sure you know that the model scale paint industry has long made good money selling the convenience of pre-thinned and pre-mixed paint colors at high prices, but quality artists' oils are still about as good as it gets for archival quality pigments. You may want to leach out some of the oil in your tubed oil paint by putting it on a piece of brown paper bag paper and letting the oil soak out for a bit. That will reduce the gloss, which you don't want for a miniature. Thin your oils with a bit of turpentine and perhaps a bit of acetone if spraying. Add a dash of Japan drier to speed up drying. To improve leveling and flow, a bit of linseed oil. Thinning should flatten the gloss finish. If not, add a bit of Grumbacher flattening solution. You know the drill, I'm sure. There shouldn't be any difference in durability between tubed and bottled paint, as far as I can see. The major difference between the two is in the thickness of the material, bottled paint containing large amounts of thinner and tubed paint not, and, importantly, the Japan dryer which speeds up drying in oil paint. Without that, the tubed paint will take longer to for its raw linseed oil binder to polymerize. (Raw linseed oil is also sold as food-grade "flaxseed oil" in health food stores. "Boiled" linseed oil, which isn't boiled at all, has dryers added to speed up polymerization.) Thin your acrylics with some alcohol, if that's compatible with your brand of acrylics. I prefer oils over acrylics, myself, probably because I'm more familiar with them and the results are more predictable for me. I don't like the acrylics that use water as a solvent for spraying because the water takes longer to dry than a more volatile solvent such as alcohol.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.