-

Posts

1,771 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Mark P

-

Good Evening Matle; Thank you for your thoughts. I cannot help but feel that to some extent you are indulging in hindsight: you know what came later, and are inclined to dismiss other practices as unlikely or 'a silly idea'. Outboard loading of cannon is mentioned often in the sources, and is actually shown in a sketch by one of the Van de Veldes (elder or younger, don't remember which) who are widely regarded as the greatest marine artists of the 17th century, and very good authorities. I suggest that if possible you read the article I mentioned at the beginning of this thread, which is by a well-respected author; is much longer than my brief paragraphs (24 pages) deals with the the subject in depth; is well-researched (it does cover much more than purely Anglo-centric sources and has over 150 references to relevant works, most of them either contemporary, or nearly so) and is well-written. I am not saying that this will necessarily change your mind, but at least you will understand the debate, and the relevant factors and writings much more clearly. For example, neither the author, NAM Rodger, nor I, made any claim that breechings did not exist, only that there is evidence that they were originally not used to restrain the gun during recoil; more specifically in the article, it mentions that they were used to secure the guns to the ship's side during stormy weather. This article (and thousands of other interesting ones) can be found on the website of the Society for Nautical Research, although if you are not a member of the NRS, you will be unable to access this resource. All the best, Mark P

-

Thank you for the further clarification, Dan; In other words, the difference in projectile velocity is unlikely to have been noticeable, and cannot have been a factor in whether or not cannons were allowed/encouraged to recoil when fired. This will help when considering the process behind the changes outlined at the beginning of this thread. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Dan; Thank you for the explanations above, which all seem well grounded. You have summarised matters more clearly in technical terms than I could have done, which certainly helps. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Jaager; Thank you again for your further thoughts, which are very welcome, as they encourage further consideration. The comment re the nose gun is interesting, and may well be true, although it is perhaps (and I only say perhaps, not knowing any facts) subjective more than it is the result of careful analysis. I remember hearing a similar comment about the A10 Warthog, the tank-busting 'Flying Cross'. Remarkable machines, they were, and presumably the F86 was similar: an airborne Gatling gun with a high rate of fire and lethal projectiles. However, a ship's cannon is only fired once, not many times a second, so the result would not be comparable, I suspect, as it is not cumulative, even if the relative masses of the two objects are in the same proportion in either case. I am not arguing that the discharge of the cannon has no effect on the motion of the ship, only that it is most likely to be a very small proportion of the total energy generated, if the cannon cannot recoil. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Jaager; Thank you for your thoughts. Although my study of physics was somewhat less thorough, and I remember very little of lines of force, I suspect that you are probably incorrect here, but certainly correct that some of the energy would be turned into heat, and therefore light also; but that would be a constant with or without recoil. My reasoning re the force would be that as the cannon is immovable, no energy can be used in moving it, although a much lesser amount may be used in attempting to move it. If the cannon cannot move backwards at the same time that the ball is starting to move forwards, then the only viable escape route for the expanding energy lies in pushing the ball down the barrel (disregarding windage around the ball, of course; but that would apply equally in either scenario) It could perhaps be contended that if the cannon cannot recoil, then the energy is in part dissipated by instead moving the ship's side to which it is attached; but as that is a considerably greater mass than a cannon-ball, I believe that the ball would move much more than the ship. It would be interesting to know how much force was exerted on the ship's timbers by a non-recoiling cannon, as compared to a recoiling one being brought up short by its breeching, at which point considerable kinetic energy would need to be absorbed and dissipated over the structure. A corollary of this would perhaps be that a non-recoiling cannon would be more liable to explode. All interesting stuff! All the best, Mark P

-

I have just finished reading a very interesting article in Mariner's Mirror, volume 82 (1996) no.3 p301-324. This was written by NAM Rodger, and is titled 'The Development of Broadside Gunnery'. This discusses, amongst other points, the evidence for the development of broadside gunnery as opposed to the use of bow & stern chasers, which latter seemingly continued much longer than most of us might suppose. Several points arise which I will try to summarise here, as they will be of interest to fellow modellers: Firstly, in 16th & early 17th century ships, the heaviest guns were frequently mounted to fire forward over the bows, as tactics generally dictated that the bows were pointed at the enemy in an attack, and not the broadside. The broadside guns were angled forwards, or 'bowed', as much as possible, to allow them to participate in the action. Secondly, the guns were loaded and fired relatively infrequently, being re-loaded in progression by a team of gunners once the ship had wore (assuming she had the weather gage) and moved away from the enemy fleet. Thirdly, the guns were fired from a fixed position, and were not allowed to recoil inboard, with re-loading carried out from outboard (this is a reasonable method if the ship is not engaged broadside to broadside with an enemy vessel) Rodger gives examples of early writings which support these arguments, and also dismantles some previously quoted texts which seem to support broadside firing from an early date, by showing that they have been mis-translated. One piece of evidence cited is Sir Henry Mainwayring's 'Seaman's Dictionary', written in the early 1630s, which specifically states that breechings are not used in a fight, but only at sea, chiefly in foul weather. An advantage to firing without allowing a recoil, not stated by Rodger, but which may well be a good reason for it, is that all the energy produced by the explosion of the powder is used to propel the shot from the barrel. By allowing recoil, the amount of energy necessary for this is thereby not used to propel the shot. The amount of energy necessary to move a 1-ton cannon backwards, especially if up a sloping deck, would be considerable, and would represent a noticeable reduction in the force of the cannon-shot, presumably. With the development of broadside firing (which Rodger shows was probably not fully developed until the mid 1620s) and a much more rapid rate of fire (early gun-crews were too small to allow individual running-in and out) it presumably became apparent that an increased rate of fire, brought about by allowing recoil and allocating much larger gun crews, outweighed the loss of projectile force. There is a lot more there, and I recommend the article to all with an interest in this era. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Kate; It looks to me like what is called an 'open heart', which is used to set up the lower end of one of the principal stays of a sailing ship, with a lanyard (a length of rope passed repeatedly through each of a pair of hearts, placed end to end, and about 3 feet apart) The two metal loops of one heart would have been fastened to the end of the stay, and those of the other heart would be fixed to a firm anchorage point. The lanyard was used to pull it all taut, and could be adjusted if necessary. The stays were large diameter ropes which ran down and forwards from the top of the masts, to a fixed point on or near the deck or bowsprit. I believe that open hearts were also sometimes used to set up the bowsprit shrouds in some merchant vessels. I am not fully qualified to comment on the date, but I would suspect it to be of either 19th century date, or early 20th. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Afternoon Gentlemen; Another interesting point re the rabbetting of timbers in the stern is that the planking of the ship's side was actually set into rebates in the outer stern timbers, which would have needed to be made thicker than the other timbers by the size of the planking, to accommodate this. This is stipulated in quite a few contracts from the later 18th century. I suspect that it is a detail too far for modellers though, as most of this joint is covered by the quarter galleries and associated carvings. All the best, Mark

-

gun ports

Mark P replied to Anthony Hearne's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Good Evening Kevin; Yes, it was common practice for merchant vessels to imitate the Navy paint scheme; as you surmise, this was indeed to discourage predators of all types. All the best, Mark P -

Good Morning Vladimir; She's coming along beautifully. Thanks for sharing the pictures and your progress. There is a lot of good detailing there, and a nice method of building the boats. Keep up the good work; I look forward to seeing what you will do next. All the best, Mark P

- 200 replies

-

- cutty sark

- clipper

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

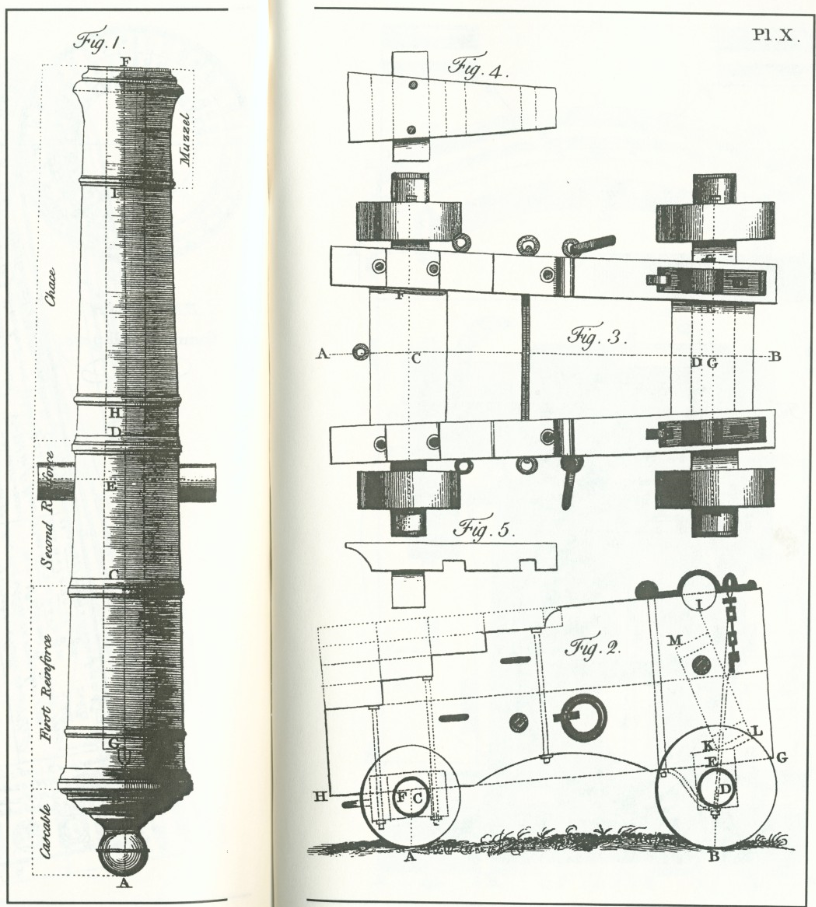

Good Morning Gentlemen; Just as a matter of caution, and for future reference, the ring-bolts shown in the drawing in Allan's post above look like ladies' earrings: very delicate and lightweight (no reflection on Allan; but whoever drew it appears to have been in error) The contract for 'Warspite', 1755, one of the first 74s, states that on the gun-deck (which would be for the 32 pdrs) the ring bolts each side of the gun-ports are to have rings with an internal diameter of 5", and to be made of 1 3/8" diameter iron. On the upper deck, for the 24 pdrs, as in the illustration, the rings are to be 4 3/4" internal diameter, and to be made of 1 1/8" diameter iron. As a rough approximation both these indicate that the metal forming the ring is around one quarter of the size of the hole in the ring. Which would look much more capable of restraining a 2 ton plus cannon on recoil. As these ring-bolts are for the breechings, as are the ones in the carriage cheeks, I would believe it a fair supposition that they should be the same. See below a plate from Robertson's mathematical treatise of 1775: (yes, I agree, not the first place one would look for gunnery-related items, but a very good contemporary source, nonetheless) All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Gary Sir; It all depends upon what sources the author uses. Don't fret too much; certainly the floors were once covered with brick. I did read somewhere, don't remember if it was a modern book, or a contemporary document, that brick stoves were done away with because the maintenance cost of them was very high. Re the joints in the lead, these would almost certainly be what we over here call 'welted' seams, where the edge of one sheet is completely enclosed in a folded edge of the adjoining sheet, and then the two are beaten flat. All the best, Mark

-

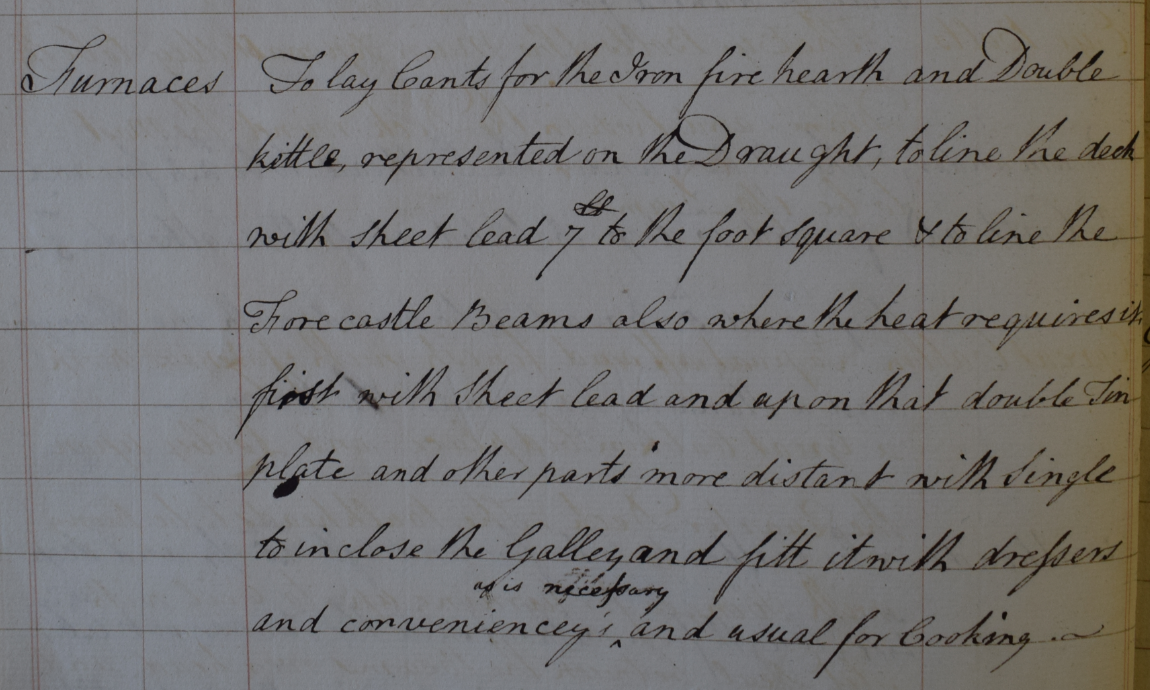

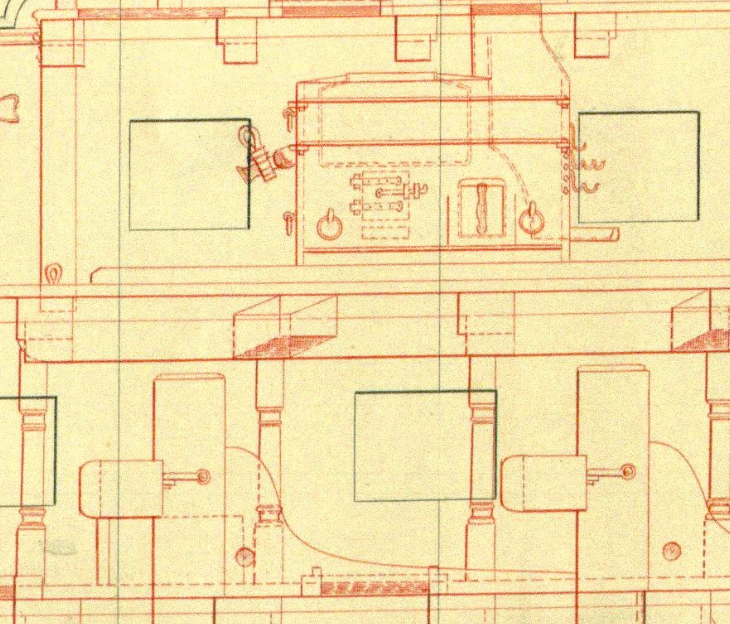

Good Evening Mark; Glad to be of assistance in any way with such a delightful build. I have the Dorsetshire draught on paper, and the upstand is most definitely a side view, not a section. Taken in conjunction with the contracts specifying that cants are laid, I would surmise that what you see is actually a timber edging around the hearth (to contain spilt liquids, probably, and ashes) with a slot in the top for the lead to be tucked into for a tidy finish. Cants, as I am sure you recall, are frequently laid on the deck under the bulkheads, and are also used to receive the outer ends of the manger boards. It seems to be a term for a timber with a slot in it; derived, one must assume, from a passing resemblance to something which has fascinated men for millenia. Hence, I think it is safe to interpret the draught and the contracts in this way. Note that the cants, or slotted timbers, are laid, which in construction terms implies that they are positioned horizontally. Additional structural strength would not be necessary on the deck, as this was supplied by fitting a couple of very large carlings below the stove area. It is also likely that the stove was supported either on feet, or on small areas of brickwork, to leave a mostly void area below the stove, allowing air to circulate and prevent direct heat transmission to the lead and deck. This was certainly the case with the earlier brick stoves. The Brodie stoves, once in use, were fitted by specialist contractors, not dockyard staff, so it is possible that if bricks were used for this purpose when iron stoves were introduced, they were fitted by the contractors, and so were not mentioned in the contract, being a specialist item. All the best, Mark P

-

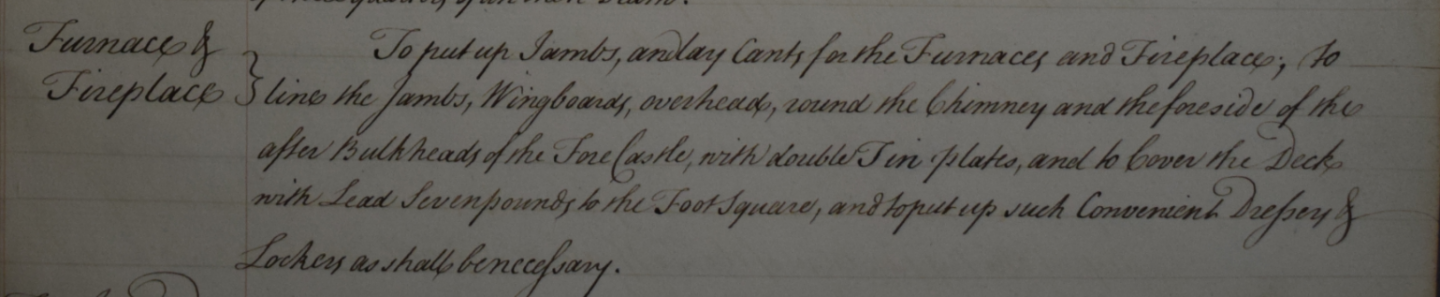

Good Evening Mark; See below extracts from a few contracts which give some detail of what was done. Warspite, William Wells, Deptford, contract date 17 Nov 1755: Furnace & Fireplace. To put up Jambs, and lay Cants for the Furnaces and Fireplace; to line the Jambs, Wingboards, overhead, round the Chimney and the foreside of the after Bulkheads of the Fore Castle, with double Tin plate, and to Cover the Deck with Lead Seven pounds to the Foot Square, and to put up such Convenient Dressers & Lockers as shall be necessary. Resolution, Henry Bird, Northam, contract date 28 Nov 1755: (repeat of the above) Culloden, specification for Deptford Dockyard, 1770: As you can see, they all seem pretty much of a muchness. Not much variation. Earlier contracts speak of lead and bricks on top of it; but probably best here to just rely on lead. There seems to have been a raised border around the edges of the hearth, which might give the illusion, viewed from the side, of a raised hearth. All the best, Mark P

-

Translation help needed - Renaissance German

Mark P replied to Louie da fly's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Good Morning Louie; Thanks for posting a very interesting picture. It looks to me as though the last four words on the second line say 'von den turken skafft' or something very similar. I stand to be corrected, though, by someone with a better knowledge of German than mine. All the best, Mark P -

Good Evening Pat; Thank you for your reply; I suppose it could be referring to a knee used as a fairlead for setting up the shrouds in the bows. Whisker booms themselves, when used on the catheads, were only a fairlead, as I am sure you know. But I don't think that the spread would be sufficient. However, to come at it from a different angle, I note that it is referred to as the 'head knee'. The 'pointy bit' in the bows is normally called the 'knee of the head'. Could it be that the author is actually referring to the cheeks, which are like knees, and function to support the head. A metal bracket could be fixed to the cheek. all the best, Mark P

-

Good Morning Pat; This is outside my era, so unfortunately I can't give you any definite help. However, it does seem to be rather odd. The bowsprit shrouds need a decent spread, or they will not perform any kind of bracing function. What the contract seems to describe is rather like fixing the mast shrouds to eyebolts in the deck each side of the mast, thereby rendering them useless. Is there any chance that the author is confusing the shrouds for the bob-stays, or the martingale back-stays. Alternatively, is the knee referred to not the actual knee of the head, but the knee supporting the cat-head. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Gentlemen; I would not be surprised at all at the need to change the facing of the crosspiece at fairly regular intervals. The force exerted by many hundreds of tons of ship being pulled up short at the end of the cable, in any but the calmest weather, would have rubbed away at the wood fibres almost continuously. This would have applied both on active service, wherein ships frequently spent periods of hours or days at anchor; and also when laid up in ordinary; although being more sheltered and moored both ends, this latter would have been a slower process. The hook and eye are mentioned in many contracts, although I don't think it is in any much earlier than those Allan mentions above, and continues throughout most of the 18th century. I cannot give a date when it ended, as my interest stops in the last decade of the century. See below an extract from the draught of Dorsetshire 70 guns, 1757. This shows details of the fastenings. Note that the eye is above the centre line, which would help it to better resist the turning moment from the greater projection of the crosspiece. Just about all crosspieces shown on as-built draughts are shown with the dashed line, indicating a facing piece applied separately. This is the only draught I have which showed the hooks, although I am sure I have seen at least one other example. The iron fire-hearth detail is interesting, and must be an early example, as not long before this they were still made of brick. All the best, Mark P

-

YOUNG AMERICA 1853 by Bitao - FINISHED - 1:72

Mark P replied to Bitao's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1851 - 1900

Beautiful work Hyw; Your work bench and shop look like an operating theatre; I take it that Frankenstein was re-vivified there not too long ago! Congratulations and all the best with the rest of the build. I shall watch with great interest. Mark P- 257 replies

-

- young america

- Finished

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Good Evening Mark; On the topic of ivory, there is a nut grown in South America, called the Tagua nut, which when worked looks very like ivory. I have some of them, and they are very hard and dense, although I have not yet carved any to see how it looks. Might be worth obtaining a few and seeing how they look. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Evening Siggi; Thanks for the pictures above. Is it SLR0472 which has the black spirketting. Looks like a very nice model; and you are right: the spirketting is indeed black. I would still maintain, though, that black spirketting is much rarer than red on models. I have photographed 20 models out of their cases, and all of these have either red or natural wood spirketting, except for the Ajax, which you list above. I have pictures of the Warrior model in the Science Museum, and this also has red spirketting, on both gun-deck and upper deck. Did you see a different Warrior somewhere? The Minerva I don't have any pictures of, but there are several contemporary models of her in existence, and at least one of them has red spirketting (it was copied for a recent model shown in 'Shipwright 2012', which has red spirketting) Even if one of the other models of Minerva has black spirketting, that would still be much less common than red or natural colour. Ajax, Minerva & Victory black, compared with 20 others red or natural. All the best, Mark

-

Good Evening Vladimir; The inboard panelling is looking very impressive. Nice work indeed. As Brian says above, it looks very real. Keep up the good work, and maintain the standard you have reached. All the best, Mark P

- 200 replies

-

- cutty sark

- clipper

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Thanks Druxey; As you say above, the Captain's cabin most often received special treatment. The more mundane parts of the ship were normally painted with whatever was available, or cheapest. Mark is right about the spirketting in the Princess Royal; but that is seemingly much less common. I have not seen it in any of the models I have photographed. Not that I doubt your memory, Druxey (I do doubt my own quite often, though) See below for pictures from the Bellona model in the NMM. The red inboard planking of the gun-deck can be seen between the upper deck ledges. The dark area above it is a shadow from the planked portion above. Note also the red faces of the beams (not the ledges, though) and the vertical sides (the strings) of the ladders. Interestingly enough, it would appear that the Captain's cabin is painted a different colour, see also below. Note the colours of the doors, the beams, and the difference between the small cabin afore the Captain's quarters, and the area aft of it. If you decide to paint this white, do not use a pure, modern white. Georgian white paint was off-white. All the best, Mark P

-

Good Afternoon Michael, and welcome to MSW and England; My only tip is take your time and work to the very best of your abilities. The only sure thing is that in later years, no matter how high the standard you try to achieve now, you will look back at this model, and think 'why did I not do it this way instead of that!' Research the subject as thoroughly as you can, and understand what needs to be done as much as possible, before you try to do it. If in any doubt, ask! There are thousands of years of combined experience available on this great forum, and never forget a very large thank you to all those who work in the background to make this possible, by keeping this site working so well. All the best, Mark P

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.