-

Posts

2,438 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Wefalck, I agree. I tried some wooly knitting thread, but when pulled tight it made a pretty thin chafing mat at 1:48. Maybe if it was wound in two or three layers it would work. Or roll a paper tube and wind the thread around it? Likewise, at larger scales the ordinary pipe cleaners I used would probably be too small. But I did notice some larger multi-colored pipe-cleaner-like "craft" things that were about 5 mm/1/4 inch diameter. For "crafty" people who smoke big pipes?

- 15 replies

-

- baggy winkle

- service

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Worst Planking Job Ever

Dr PR replied to rhephner's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

rhephner, As you know, wood will bend, but it has a grain that tries to straighten it back to the original shape. To get it to curve around the shape of the hull you have to "retrain" it to the new shape. Virtually every tutorial about bending wood mentions water and heat. Some people just use water and clamp the wet wood into a form with the desired curvature. Eventually the wood will adapt to the curve - I'm not sure the water has anything to do with it. Steaming wood to get it to bend is a very old technique. The heat is what does the work, and hot water or steam is used to convey the heat into the wood quickly. You also need to taper the planks to compensate for the difference in distances around the large midships bulkheads/frames and the shorter bow and stern bulkheads. The best way I have found for getting planks to form to the shape of the hull is to heat bend them on the hull. This gets all the correct curves and twists - you won't get this with an off-hull bending form. I use an inexpensive ($35) quilting iron (Mini Iron II - Clover No. 9100) as a plank bending tool. I put the plank on the hull in approximately the position it should go. Then I wet the plank with water, using a paint brush. Then the bending iron is applied to turn the water to steam and heat the plank. Quite often a single pass along the plank is enough to get the desired bend. I usually give it three passes anyway, just to be sure. After heat forming the plank It will just lay on the hull with the correct shape without clamping. Then it is easy to glue in place. This is far and away the best way to bend planks that I have seen! This link shows how I have been doing this: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/37060-uss-cape-msi-2-by-dr-pr-148-inshore-minesweeper/?do=findComment&comment=1075263 -

Downloading PDF files

Dr PR replied to popeye2sea's topic in Using the MSW forum - **NO MODELING CONTENT IN THIS SUB-FORUM**

Henry, This could be a browser problem. I'd do a Google search for problems receiving PDF files with your browser. Several years ago high-zoot programmers had a convention to discuss how to "improve" the Internet. One of the problems is that the file type (name.type) for the file names can be anything, thanks to the less than brilliant programmers who created this crap. Anyone can rename a text file type to be a picture file type, or anything else. Computers use the file type to determine which programs should open the file, but in fact, because there is no security built into the system, file types are meaningless. Hackers use this bug to plant software "bombs" that can take over programs that open the files. So the later day geniuses decided that file types would be used no more. The file type must be embedded in the file header (part of the information in the file). Returning from this convention, one of these less than brilliant programmers changed a popular email program to reject all PDF files that did not have the file type embedded in the header. And in one incredibly stupid stroke this idiot denied the program's users access to virtually all the collected wisdom in the world that was in PDF format because this new "standard" had not been implemented yet!! And, of course, most of those old files will never be updated, nor will much of the software that generated them. This is the sort of stupidity that passes for intelligence among the folks who manage the Internet and develop software, web pages and such. And it is quite possible that one of these bozos created an update for your browser that rejects old format PDF files - or any other file created before this convention of idiots. -

Chuck, Push a pin into a piece of wood. Stack thimbles on the pin until you get to the number you want to package (25?). Clip off the pin above the stack. Now to measure the number of pieces you don't have to take the time to count them. Just stack them on the pin, dump into a bag, repeat. And I would do this over a large bowl or baking pan, with the parts in the bowl/pan. That way they can't roll away.

-

I rigged the port anchor buoy about the same as the starboard buoy, mainly because I couldn't think of a more reasonable way to deal with the buoy while the anchor was being fished. In this scenario after the anchor was hauled up horizontal the buoy was pulled in, tied to the forward shroud, and the rope coiled and tied in place to get it out of the way. Now I just need to add the flag.

-

Topsail schooner sail plans and rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

wefalck, I have seen the triangular course as well. And there is a triangular topsail (rafee topsail). The sail in the photo is flown on the windward side where it would have some effect. Because the fore staysail is also raised a full course would probably chafe against the staysail. So from a functional standpoint this makes sense. Or maybe they were just drying laundry? **** When I started this thread I naively thought there was a "way" to rig a schooner. But after finding 10 different ways to rig just the main gaff topsail I realized that if a way to rig a sail is possible someone has probably tried it!- 104 replies

-

- schooner rigging

- Topsail schooner

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Topsail schooner sail plans and rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Just when you think you have seen it all, something new pops up. Look at the sail marked with the red arrow on this nice photo (by Tyler Fields) of the modern replica of the Lynx. What do you call this sail? It might be a studding sail, bit it isn't attached to the studding sail yard. It is attached to the course yard (spreader). Is it a "half course" as opposed to a "full course?" It might be a triangular sail.- 104 replies

-

- schooner rigging

- Topsail schooner

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

What Am I Missing

Dr PR replied to acaron41120's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Allen, I have a collection of rulers gathered over the ages, and it is surprising that some of them differ greatly from the rest - even the triangular "engineering" and "architecture" scales. Some are off as much a 1/8 of an inch in 12 inches (1 part in 96 or 1.042%). Good enough for grade school or making dresses, but not OK for precise measurements. I have a steel ruler marked in 100ths of an inch and it agrees exactly with a CAD created scale printed at 1:1 (viewed with a magnifying loupe). This is my "standard" ruler. When I need to measure around a curve (like the edge of a bulkhead) I cut paper strips, mark them carefully, and measure with the ruler. -

Good choice. From what I have read many American ships followed the British color scheme of black from the water line up to the band along the gun ports. This was a yellow color. They repeated the black/yellow/black pattern for each gun deck. The mast tops were painted black - probably because they had that paint on hand. This changed to black and white sometime before 1830 on some ships, and on nearly all by the 1840s. When they switched to white bands along the gun ports they started painting the mast tops white. I have never seen a comprehensive discussion of ship colors in the 1700s and up until the mid 1800s. Chapelle did write a paragraph about schooner colors in The Baltimore Clipper on page 170. Blue is one of the colors he mentions for hulls, and dark (Navy) blue would be appropriate.

- 257 replies

-

CA (cyanoacrylate) "super glue"

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Thanks to everyone for all the tips and information. I am familiar with Bob Smith Industries. In my company's work making oceanographic instruments and some other industrial controls we special ordered custom glues specific for unusual environments (8000 psi deep ocean pressures or high temperatures). I haven't seen BSI products on the shelves around here, but I'll look again. Maybe I will try Gorilla CA - I have seen Gorilla products in stores here. **** To answer Gary's question "Is Corvallis, Oregon, particularly humid?" This is western Oregon, 36 miles from the Pacific Ocean! If the ground gets dry folks call it a drought! Some years it rains from November to May almost non stop. However, it isn't "rain" like you get in the southwest. It mostly drizzles, and what Oregonians call rain we called "sprinkles" when I grew up in Arkansas. We get only about 40 inches per year here in town, but up to 120 inches on nearby Coast Range mountains. The saving grace is that it doesn't rain much in summer and fall, and it rarely gets hot. So it never gets hot and muggy. -

I learned long ago to rig the ropes with barely enough force to pull them straight, without bending anything. This will eliminate almost all slack lines. You can permanently fix ropes in the straight shape by painting the rope with shellac or white glue (shellac for polyester and white glue for cotton and silk). This is also good for "training" lines to have a smooth curve or sag where appropriate. However, I do have this problem on my current build with lines to the fore course (spreader) yard because there are several lines lifting the yard and none pulling down. The yard rides up and the lifts and buntlines go slack. If I had rigged the course the lines to that sail would have pulled the yard down. I can probably solve this problem by weighting down the yard to stretch the lines tight and then fasten (glue) the trusses to the mast. Another option is to drill a small hole through the yard and into the mast, and push a wire or pin through to hold the yard in position.

- 431 replies

-

- Flying Fish

- Model Shipways

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Here is a bit more progress. I have added foot ropes to the bowsprit. Apparently these ropes were called "horses" up through the end of the 1700s (in English). Then they were called "man ropes." Today to be politically correct perhaps we should call them "people ropes." Horses, manropes, people ropes - they are all silly. Obviously they are foot ropes (or footropes)! When I started investigating how these ropes were attached I found varying opinions - probably all correct for particular ships at a certain places and times. Lee's Masting and Rigging of English Ships of War says the ropes were attached to eye bolts on the sides of the bowsprit cap. But he talks about large square rigged ships of the line and doesn't belittle himself to talk about the other less important ships like schooners. But I have seen foot ropes on schooner models rigged this way. Lever's The Young Sea Officers Sheet Anchor, Marquardt's Global Schooner and Mondfeld's Historic Ship Models all say the rope was looped around the jib boom behind the bowsprit cap and lead forward to the end of the boom. This is how I have rigged it on this schooner model. The forward ends of the lines could be attached to the end of the jib boom with a cut splice or two eyes. I used two eyes. The books say that often knots were placed at intervals to give the sailors better footing. Again there are different opinions. Depending upon which author you read the knots were this type, that type or some other type. But most say overhand knots were sometimes used, and this is good enough for the model. However, bosun's mates like to tie fancy knots. Left to themselves they often tie elaborate knots to escape the boredom of life at sea, or to look busy when the bosun is looking for someone to do real work. Now I just need to train the foot ropes to hang in a smooth catenary. **** I think there are only two things left to do on the model. I am working to finish rigging the port anchor buoy. I will probably rig it like the starboard one, although it might not have been tied in the storage position until after the anchor was secured to the rail. The flag is a problem. I have a good image of the fifteen star and fifteen stripe flag used from 1795 to 1818 (the "Star Spangled Banner"). So far I have printed it only on 24 pound printer paper, and that is pretty heavy. I need to try to print it on thinner paper if I can find some suitable for my printer. I have lost my "to do" list so I think that should finish the model. But I still need to build a suitable display stand.

-

Many on the Forum seem to prefer super glue to other cements. I dislike it! I guess I am jinxed when it comes to super glue. I have purchased maybe six tubes in my lifetime. Of the first three one hardened in the tube before I ever got to use it. I used only a few drops from the other two before they became solid. The only good luck I have had with it was recently. I bought a tube of Loctite gel in a fancy applicator "bottle." This was just a plastic shell with things on the sides that squeezed an ordinary tube of glue inside. I used it between one and two dozen times before the cap became glued to the tip. While trying to get the cap off the tube began turning in the plastic shell. This twisted the tube about half way along its length, trapping about half of the remaining glue in the bottom. I eventually disassembled the thing and found the top half hardened. I poked a hole in the bottom half of the tube to get a couple more drops. Then the rest hardened. Then I bought these two tubes a couple of days ago. The instructions said to screw the end/cap pair onto the tube to puncture the thin metal diaphragm on the top of the tube. Try as I may it didn't work with the tube on the left. So I tried to puncture the diaphragm with a sharp metal point - it wouldn't puncture! The entire brand new tube was rock hard! The second tube was still pliable so the glue inside was still liquid. I tried to open the second tube and the cap would not screw on straight and puncture the diaphragm. I punctured the diaphragm with a metal point and used the end/cap from the first tube. So far I have gotten three small drops of glue from this second tube. So out of six tubes of superglue I have purchased only one gave me at least half a tube of glue before it hardened. Two were hardened before I opened them. Two more solidified shortly after I opened them. Considering the relatively high cost of this stuff, it has cost me two to three dollars per drop. That is extremely expensive! Apparently other people have had better luck and have actually been able to use super glue regularly. Does anyone ever get to use an entire tube before it hardens? What's the secret? **** Of course there is the other problem with super glue - the fumes are very irritating! Many glues have odors, but super glue is the worst! **** I have several other types of glues and these last for years after opening. I have even emptied some of the containers while the glue was still good!

-

Dan, What material are you using for rope and seizing? Every material I have used (cotton, silk, polyester) is a bit springy, and knots will try to come undone. However, silk becomes totally limp when wetted with white glue, and this prevents unwinding while the glue dries. Cotton is not quite as good, but it does lose most of its springiness when wet. Polyester rope is very springy, and knots will come untied if they aren't fixed with some type of glue. Unfortunately, the only glue I have found that will stick to polyester is CA (cyanoacrylate, super glue), and I am not sure just how good that bond is. White glue will not stick to polyester! I glue the larger rope strands together with a small drop of CA and then wrap the seizing, with a bit of white glue after the seizing is done to hold it. I normally dilute the white glue 1:1 with water, but I have also used about 70% glue and 30% water.

-

One of the details I wanted to add to the model was the "baggywrinkles" (baggywinkles, chafing mats) on the main boom lifts. I posted how I made these from pipe cleaners in this link: https://modelshipworld.com/topic/38184-chafing-mats-or-service-on-lines/?do=findComment&comment=1100130 Here are some photos of the finished part in place on the main boom topping lift. I had to unhook the standing part of the lift runner tackle from an eye bolt on deck to give the lift enough slack to wrap into the pipe cleaner coil. Then the tackle was hooked back to the eye bolt to pull the lift taut. The eye bolt is close to the bulwark so I had to use a small dentist's mirror to look down between the deck house and the bulwark to see the hook and eye. As I slowly withdrew the mirror the end of the handle caught on something (fore gaff vangs?). There was a slight tug and then "pop." Another plastic hook broke - on the fore gaff peak halliard upper block. You can see the block hanging down over the gaff at the upper left of the last photo. One step forward, one step back!

-

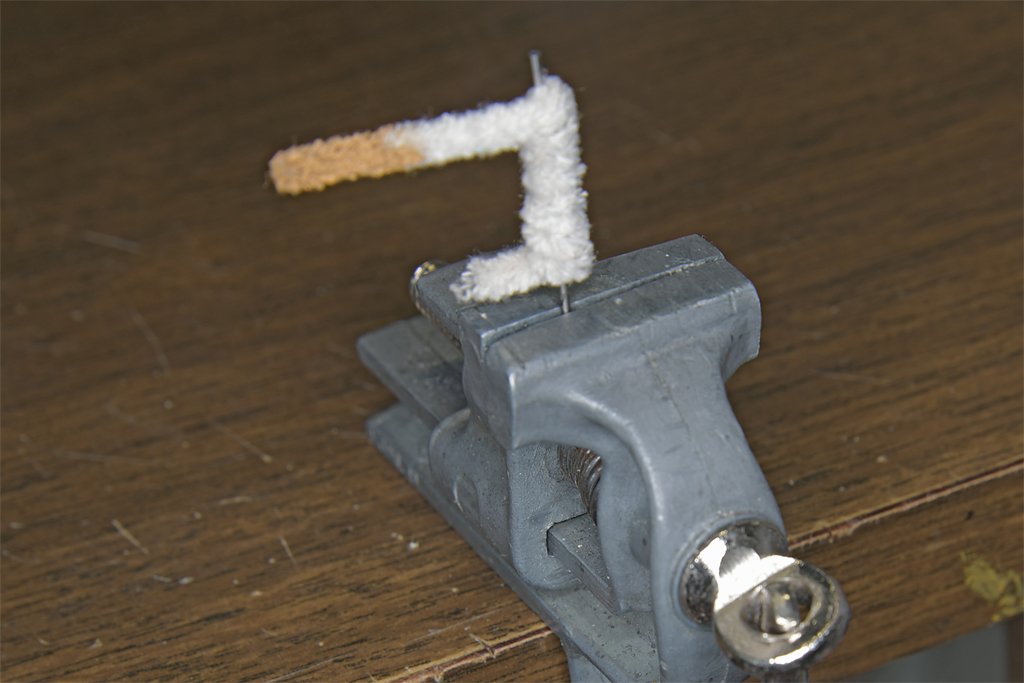

Baggywrinkles revisited. I looked at "fuzzy threads" for knitting at a local store, and they have very little bulk. I think if they were wrapped around a rope they wouldn't make much of a bundle. Then I got the idea to use one of my standard tools/building materials - pipe cleaners! I don't smoke, but I have had this package of pipe cleaners in my modeling kit for decades. They are handy for cleaning out small orifices and such. First I clamped a small drill bit into a vise. Then I wound the pipe cleaner around it tightly, leaving short "handles" at each end. Here you can see I was also experimenting with coloring the mat. The pipe cleaner material is cotton, and cotton absorbs water. I dabbed on some acrylic paint to give it the color of "used rags." The paint soaked up nicely. I am adding these after the boom lifts were already rigged. The trick here is to pull the spirals of the mat open. This allows the rope to be wrapped into the gap between spirals. But that means the rope must hang loose while you are wrapping it into the mat. The standing part of the boom lift running tackle is hooked to a ring bolt on deck. The lift wasn't installed tightly so the hook came loose easily. This allowed the lift line to be wrapped around the mat. After it was in place I cut off the "handles" and touched up the paint. Here is a photo (left below) of the baggywrinkle on the model's boom lift. The photo on the right is a mat on the replica schooner Lynx.

- 15 replies

-

- baggy winkle

- service

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Carriage Gun Rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

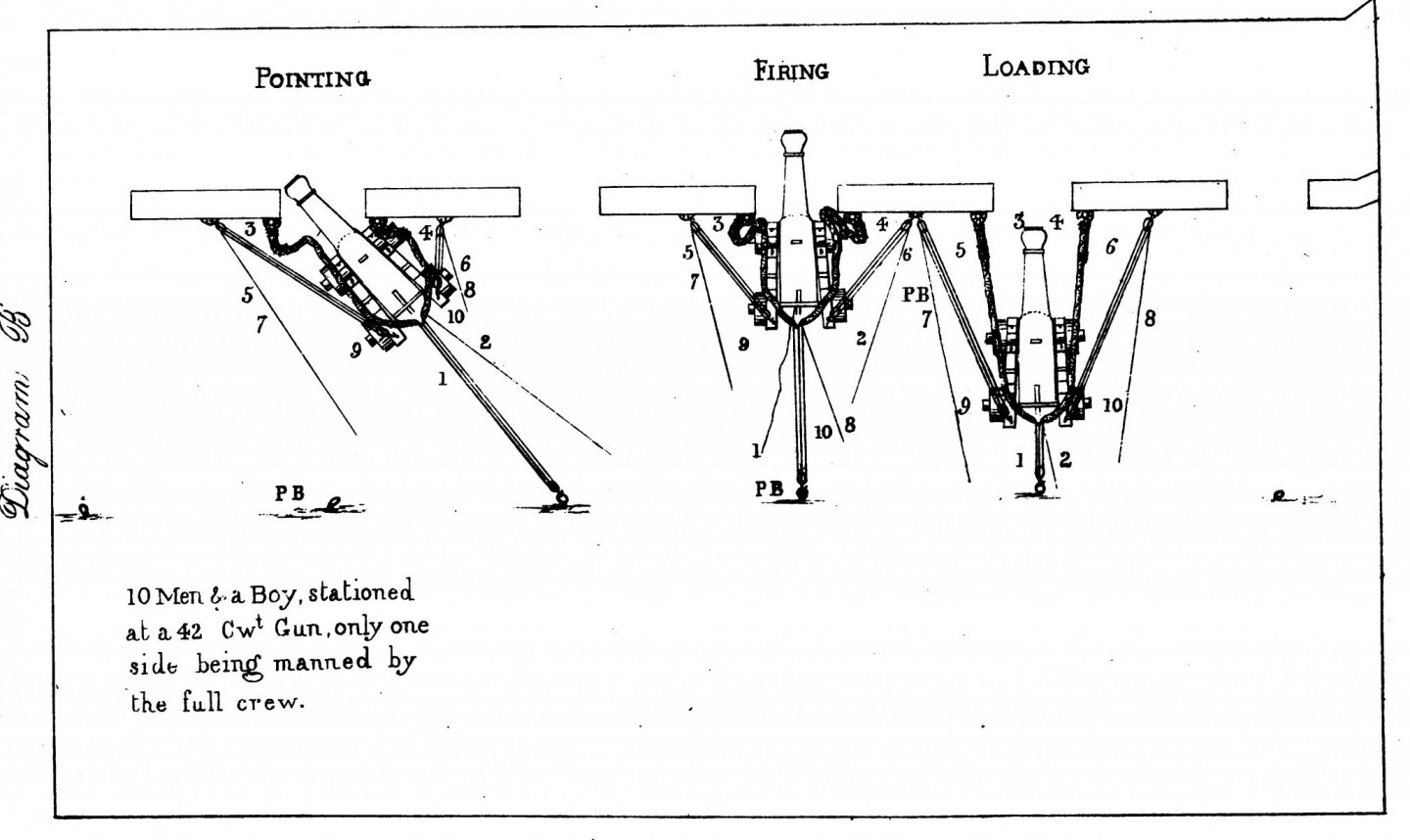

Here is a drawing from Ordnance Instructions for the Unites States Navy (1860). It shows the method of pointing a gun at an angle to the centerline of the ship. For the big lumbering square rigged ships of the line what wefalck said is probably true. But there are accounts of smaller, more maneuverable vessels like schooners pulling up off the quarter and out of the firing field of larger ships and blasting away at them. In this case angling the guns toward the target would be useful. Pivot guns apparently were often used this way. In any case the Navy seems to have thought it would be useful to train gun crews to point their guns at different angles. -

Some wooden hull vessels had a thin layer of oak sheathing applied over the normal hull planks. The sheathing consisted of planks attached to the hull to protect the hull in places where it could be damaged by objects being lowered/raised over the side. This sheathing was replaced when it was damaged. In two cases I know of the planks were not tapered. In one case the entire underwater hull was covered with thin sheathing, and the planks were not tapered. Does anyone have any information about how these planks were applied? What pattern? How do you plank a hull without tapering the planks?

-

Gary, About the epoxy and the Navy. I don't know how far back that goes. But we did use epoxy paint in the missile house and warhead magazines because we couldn't paint in those spaces while ammunition was loaded. So it was a big project to offload everything at a Weapons Depot and repaint the magazines. However, the grey paint that was used topsides seemed to me to be water soluble and had to be repainted continuously. When I asked our Weapons Officer why epoxy paint wasn't used topsides he replied that there wouldn't anything for the crew to do to keep them busy. "Idle hands are the tools of the devil ..." So they chipped paint. I don't like how this planking is turning out. I have finished the sheathing down to the bilge keel. The planks from the bow are at a sharp angle to the planks from the stern. I have no way to know how they should come together. It looks like a mess to me!

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Sheet Metal Shear Recommendations?

Dr PR replied to DerekMc's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Derek, I do not have a shear right now. I used to use the one in our shop at work - but it was a 48 inch wide cutter for large sheet metal work. I like the looks of the 8 inch machine grsjax posted the link to. I think MicroMark used to sell one similar to this. Sorry to say Trump's Hobbies has closed. Jim was at retirement age and Internet competition was really hurting the business. He tried to sell the business but had no serious offers. -

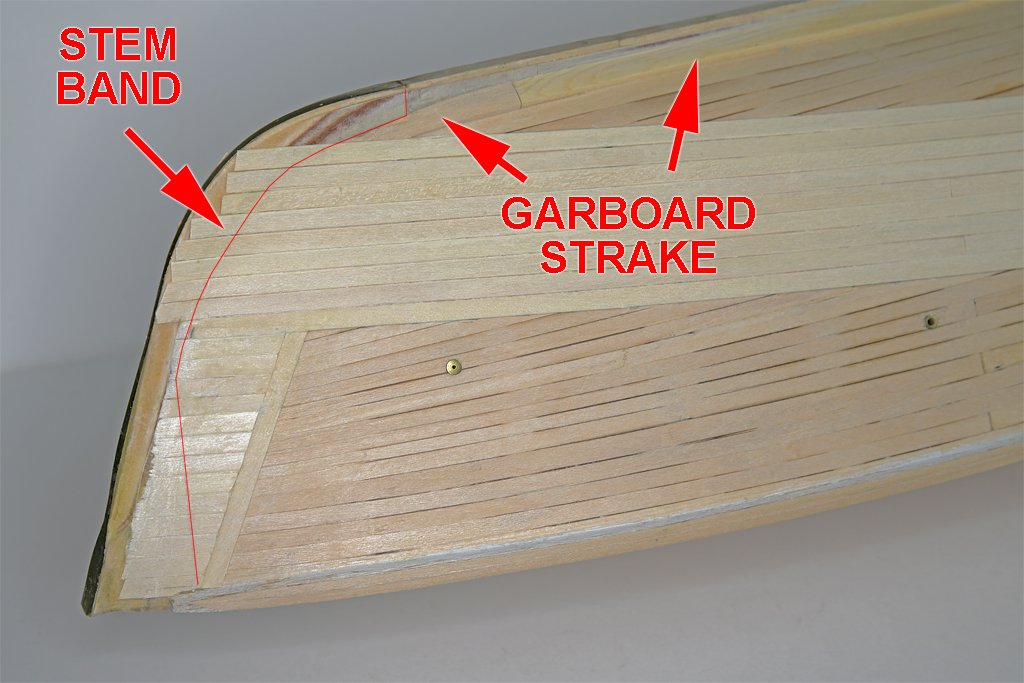

Here are a couple of photos to show the "lay" of the sheathing. On the real ship this sheathing was made of 3/4 inch thick red oak planks. The blueprints say nothing about how to place the planks around the bilge keels - but they do say to cover the bilge keels with the sheathing. Tricky! But you can see how I am trimming the planks to fit up to the bilge keel. The blueprints say to trim the sheathing around hull openings, rudder plates, seachests and the stern frame. I will have to relocate the sacrificial anode adjacent to the starboard sea chest. Here you can see how the sheathing planks meet the garboard strakes at an angle, rather than being spiled to run along beside the garboard. The blueprints say to cover the garboard strake and the keel with sheathing, but to not cover the worm shoe (it is also made of red oak). The thin red line shows where the brass stem band will fit over the sheathing. The sheathing planks will be tapered gradually to zero thickness where they meet the stem so the stem band will fit smoothly over them. It's "deja vu all over again."

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Gary, Thank you very much! This is not only interesting information about fishing boats, it does help me understand the origins of this practice. Interestingly, the Cape's planking was 3/4 inch red oak, even though the ship was built in Washington State where Douglas fir was abundant and cheap. You mentioned trim to protect the end grain. A vertical angled strake behind the bow sheathing is shown on the MSI blueprints, and in the photos of the bow of the current Cape. The blueprints don't say anything about how the sheathing was applied between the bow and stern! My photos of the ship in the 1960s don't show this end grain protection for the sheathing farther back along the sides. But the pictures are pretty grainy and hard to interpret. Do you think it should have vertical pieces to protect the end grain? Not tapering or spiling the planks really goes against the grain (pun intended) of everything I have learned about wooden hull construction. I am now carefully cutting the planks to sharp points where they fit around the bilge keels. And soon they will be tapering to fit the garboard strakes. And somehow the planks will have to flow off the after curved hull surfaces onto the flat deadwood and stern frame around the prop and rudder. The blueprints show them running parallel to the bottom of the keel on the deadwood at the stern. I don't know how this will turn out! **** I have been following and admiring your Pelican build. You are doing a beautiful job.

- 464 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Sheet Metal Shear Recommendations?

Dr PR replied to DerekMc's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Derek, It looks to me as if the shear you posted the link to is just a crude cutter. A good metal brake (shear and bender) has a "table" on one side that you rest the piece to be cut on, and adjustable stops on the other side to control the width of the piece being cut. You place the work piece on the table with the knife blade up, push the piece through beneath the blade until it contacts the stops, and then cut. This allows you to cut many strips of exactly the same width. A good shear will also have multiple "clamps" that lower with the blade, contacting the work piece and clamping it to the table just before the blade cuts the metal. This prevents the cutting forces from twisting the metal during the cut. The device you posted a link to doesn't have a wide enough table, no stops, and only the one clamp that will not prevent the piece from moving during cutting. It is better than scissors only in that it can cut thicker metal. But it is just for chopping the ends off of longer strips. **** A break will also have bending feature. This is usually a lower fixed "V" groove, with an upper moving "V" shaped piece. It doesn't cut the metal, but just bends it 90 degrees. You can also get tool pieces to bend different angles and different shapes These tools usually have sets of the upper "V" pieces of different widths so you can make bends of varying lengths between other features in the work piece. Like the shear, the bender will have a table to feed the metal into the bender, and will also have adjustable stops so you can feed the piece in the correct distance before bending. This allows you to make repeated bends of pieces with the same dimensions. **** Here is an example of a tool with these features. It also has a sheet metal roller for creating controlled radius curves in sheet metal. https://micromark.com/products/3-in-1-metal-worker?keyword=metal shear If the price is a bit too steep, or it is too large for your work space, you should also look into photo etch bending tools. These are good for thin metals. They are not as sophisticated as a real shear and break and do not have a shear. For brass thinner than 0.015 inch (0.4 mm) you can make cuts with a knife. Just clamp the metal to be cut with a steel ruler placed along the line to be cut. Then draw the knife blade (a dull blade will work) along the ruler edge repeatedly until it cuts through the metal.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.