-

Posts

2,466 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

Sheet Metal Shear Recommendations?

Dr PR replied to DerekMc's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Derek, It looks to me as if the shear you posted the link to is just a crude cutter. A good metal brake (shear and bender) has a "table" on one side that you rest the piece to be cut on, and adjustable stops on the other side to control the width of the piece being cut. You place the work piece on the table with the knife blade up, push the piece through beneath the blade until it contacts the stops, and then cut. This allows you to cut many strips of exactly the same width. A good shear will also have multiple "clamps" that lower with the blade, contacting the work piece and clamping it to the table just before the blade cuts the metal. This prevents the cutting forces from twisting the metal during the cut. The device you posted a link to doesn't have a wide enough table, no stops, and only the one clamp that will not prevent the piece from moving during cutting. It is better than scissors only in that it can cut thicker metal. But it is just for chopping the ends off of longer strips. **** A break will also have bending feature. This is usually a lower fixed "V" groove, with an upper moving "V" shaped piece. It doesn't cut the metal, but just bends it 90 degrees. You can also get tool pieces to bend different angles and different shapes These tools usually have sets of the upper "V" pieces of different widths so you can make bends of varying lengths between other features in the work piece. Like the shear, the bender will have a table to feed the metal into the bender, and will also have adjustable stops so you can feed the piece in the correct distance before bending. This allows you to make repeated bends of pieces with the same dimensions. **** Here is an example of a tool with these features. It also has a sheet metal roller for creating controlled radius curves in sheet metal. https://micromark.com/products/3-in-1-metal-worker?keyword=metal shear If the price is a bit too steep, or it is too large for your work space, you should also look into photo etch bending tools. These are good for thin metals. They are not as sophisticated as a real shear and break and do not have a shear. For brass thinner than 0.015 inch (0.4 mm) you can make cuts with a knife. Just clamp the metal to be cut with a steel ruler placed along the line to be cut. Then draw the knife blade (a dull blade will work) along the ruler edge repeatedly until it cuts through the metal. -

Per, thanks. Shooter, When I was in training for the Talos system everyone was talking about missiles that could be stored like "telephone poles" - just put them in the magazine and forget them until you were ready to fire. They should be more reliable, and there was much less danger from handling them all the time. Talos missiles had to have the NiCad batteries recharged and replaced every month, and the entire electronic and hydraulic system tested every other month. That kept the missile crew busy round the clock babysitting 44 missiles. And that increased the danger of mishandling. We had 13,200 pounds (6.6 tons, 5,987 kg) of class A high explosives and 176,000 pounds (88 tons, 79,833 kg) of class B explosives in the missile house. Plus the capability of carrying nuclear warheads. It just wasn't a good place for handling accidents! I am not familiar with how much servicing the newer Aegis system missiles need, but just storing them in the vertical launchers without having to move them around all the time makes the system much more reliable and safe!

- 54 replies

-

- 3d cad

- cleveland class

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

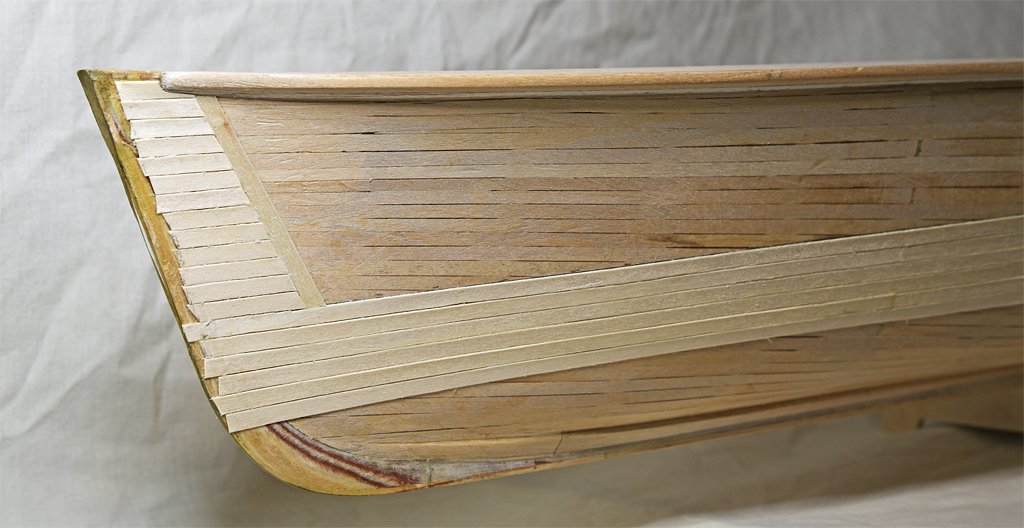

I have been working on the hull sheathing while finishing the topsail schooner build. The rounded edges on the planks created by the draw plate do a good job making the gap between planks. The biggest problem so far has been glue (Sig-Bond Cement) squeezing up between the planks. If it hardens it hides the gaps, so I must wipe off as much as possible immediately after placing the plank. Then I drag a sharpened wooden toothpick point along the groove to gouge out any remaining glue. This also tends to spread the planks a bit, enhancing the gap. The planks are so thin (0.015 inch or 0.4 mm) that they conform to the curves of the hull without any special bending, and are held in place by the wet glue. Nevertheless, I use blue painter's masking tape to hold down the planks until the glue sets. The planks at the stem will be covered by the brass stem band. First I will carve them to zero thickness at the "rabbet" where the hull planks meet the stem so the stem band will conform to the shape of the planking. After the glue sets, if any of the planking gaps are obscured, I pull an old #11 knife blade with a broken tip along the gap, dull side first, to scrape out any dried glue. I can see painting the hull will be interesting because I don't want the paint to obscure the gaps!

- 489 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

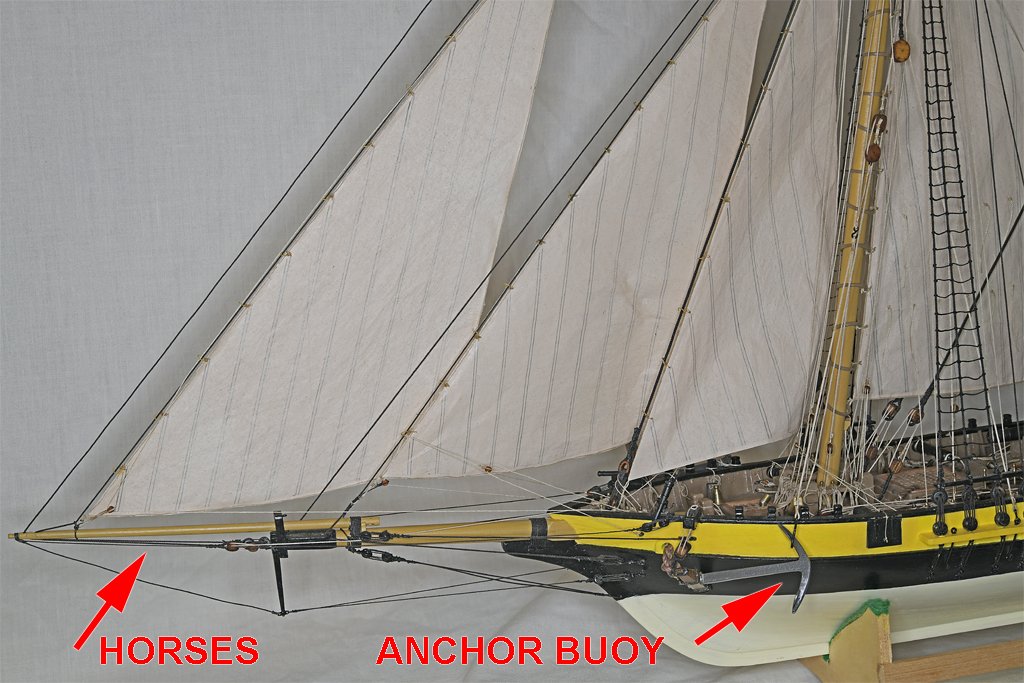

The port ratlines are finished!!!!!!!!! The model is almost finished! There are only three things left to do (that I can remember now). First I need to figure out how the port anchor buoy should be handled while the anchor is being fished. Was it pulled out of the water first before the anchor was fished, or left in the water while the anchor was fished? While the crew is fishing the anchor, if the buoy is brought aboard, what did they do with it while handling the anchor? Second, I need to add horses (foot ropes or man ropes) under the jib boom. Third, there is the chafing mats or serving on the main boom topping lift. I need to check my to-do list to see if there is anything else I have forgotten.

-

Carriage Gun Rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Thukydides, Good point about the thimble(s) being strapped to the neck of the pommelion or cascabel. Why two thimbles? The thimbles or iron breeching ring would solve a problem the cut splice created - the breeching rope would be free to pass through the thimble/ring as the gun is aimed at an angle. This would allow the gun to recoil more in a straight line until the breeching rope pulled tight to stop it. The recoil force would be born equally by both ring bolts in the ship's side. When a gun was fired at an angle with the cut splice the breeching rope would be pulled tighter on the side to which the gun was aimed. Therefore, in the recoil that side would pull tight first and jerk the gun around until the other side pulled tight. Most of the recoil force would fall upon one of the ring bolts. I'm sure gun crews understood that they shouldn't be standing behind one of these things when it fired. But having the gun flailing around a bit more would be "inconvenient." I like your idea that the thimble(s) spliced to the neck of the cascabel would be an evolutionary step toward casting the breeching ring in the cannon itself. -

I Have an Itch to Scratch

Dr PR replied to SaltyScot's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

For cutting bulkheads, frames and other curved pieces as scroll saw is very handy. You can do this with a coping saw or jeweler's saw, but the scroll saw is much faster. You can use it for cutting small pieces of any shape from larger sheets. A disk/belt sander is very useful for finishing edges, bevels and such. You can use it for the final trim of parts that were cut out with the scroll saw. The one tool I miss the most is a milling machine. This will allow drilling a sequence of evenly spaced holes in a straight line, like the holes in a pin rail. You can also mill precisely dimensioned shapes with holes and cutouts, like parts for cannon carriages or "mag" wheels for cars. A drill press with an X/Y table is a poor substitute but better than nothing. A drill press is designed for up/down drilling only. A milling machine has bearings designed to take lateral forces, so you can use end mills to rout out grooves and finish surfaces with high precision. I want a small mill that has little runout or wobble (very good bearings). For large drill bits it doesn't matter much, but with small bits it is very important. If the drill bit wobbles the hole will not be round, and small bits will snap off. A ventilated paint booth would be good if you do much spray (airbrush) painting. Or you can do what I do, and wait until it warms up outside and do the painting in the back yard. I find my quilting/wood bending/sail making iron very useful. You need some sort of vise to hold things while you work on them. If you do much work with brass or other metals an sheet metal shear (brake) would be useful for cutting custom dimension strips. A sheet metal bender is useful. If you work with small pieces of thin metal a photo etch bender will do. A soldering iron is useful for working with brass and other solderable metals. -

It's good that you have that problem solved. When we moved my Mother into assisted living (at age 101) she didn't want to leave her home. But she really was lonely there, even though neighbors visited occasionally and she was across the street from my brother. But she really blossomed in the retirement community, making a lot of new friends and becoming the matriarch of the place. Lets hope your mom is as happy with her new home. And you have the plus that when you visit you can also inspect the ship model(s). Did you notice any other models in the place?

- 257 replies

-

Mark, The white glue soaks into the threads of cotton and silk lines (I prefer silk) and binds the knots. But it doesn't bind to polyester ropes. So the knot really is free to slide up and down on the polyester shrouds if you tug on it hard enough. But for ratlines that isn't a problem. If you did somehow manage to move the knot you just have to slide it back in place and apply a drop of water to loosen the glue. When the water evaporates the glue will set again. I really like silk thread for seizing and such. When it gets wet it goes totally limp, making tight knots and seizing. Cotton is almost as good when it is wet.

-

Carriage Gun Rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

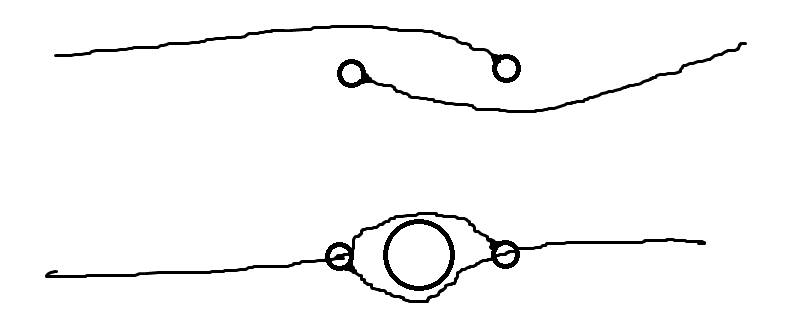

Here is a wild guess - just that, a guess. 1. Suppose you cut the breeching rope in the middle (at the cascabel). 2. Then splice a thimble in each end (double thimbles). 3. Run the other end (without the thimble) of one rope through the thimble on the other rope. 4. Repeat with the other rope (the loose end through the thimble of the opposite rope). 5. Now you have an "eye" between the two thimbles that can be slipped over the cascabel. Top: two ropes with thimbles in one end. Bottom: each rope passes through the thimble on the other. This might be easier to rig than a cut splice, and it would be easier to attach and remove from the cannon. REPEAT: wild guess! -

Best White Wood Glue For Ship Building

Dr PR replied to OldeManToad's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Gregg, Shellac is an alcohol solution. You can keep it in any container that you can use for alcohol. I'm sure the plastic needle-tip applicators will work. Remember that it is an alcohol solution, and the alcohol will dissolve other alcohol-based dyes or alcohol soluble compounds. I used to use shellac to stiffen ropes to get the proper catenary or droop. But I made the mistake of using an alcohol based dye on the blocks in my current build. When I wet the ropes with shellac the alcohol dissolved the dark brown dye and it wicked down the ropes, leaving an ugly brown stain in the ropes near the blocks. Now I have to use diluted white glue to stiffen the ropes! Shellac is available in 12 ounce (340 grams) spray cans (Zinsser Bulls Eye Shellac). This would be handy for covering large areas, as in furniture finishing. But you can spray a small amount into a jar or cup and apply it with a brush or just get a small drop on a needle. I am told it will "go bad" after a while, but I haven't seen this in a can several years old. I also have the shellac flakes that can be dissolved in denatured ethanol to get a desired concentration (cut). Discussions of the "right" way to mix, store and use shellac can develop into almost fanatical arguments. There is a lot posted about it on the Forum. -

Best White Wood Glue For Ship Building

Dr PR replied to OldeManToad's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

vaddoc, When the acetone in Duco Cement evaporates it leaves a plastic-like solid. I think it is just dry nitrocellulose, with no chemical curing like other glues. It will fill narrow gaps to a degree, but the volume reduces significantly as the acetone evaporates. In narrow cracks it usually leaves a "U" shaped surface across the crack. So it doesn't really fill the crack completely. However, I have mixed it with wood powder/dust from sanding to make a good crack filler. One other interesting thing - nitrocellulose is gun cotton, an explosive. It is very flammable. But so is wood, plastics, cotton thread and many other things we use in modelling, so that really isn't a problem. I have yet to have one of my models explode! -

Tom, Not all gaffs had jaws and parrals. On many ships the gaffs (and booms) were attached with goosenecks that pivoted in sockets fixed to the masts. The sails were furled by hauling on brails attached to the sail trailing (leech) edge and drawn up to the gaff and mast. In fact, I think this was more common on larger square rigged vessels with "spankers" or "drivers" on the mizzen masts. The gaff with jaws and parrals seems to have been more common on smaller vessels, especially fore-and-aft rigged ships.

- 206 replies

-

- Endurance

- Shackleton

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Andoni, Glad you enjoyed this log. Since the Albatros is your first wooden ship you should worry less about historical accuracy and getting it "perfect," and use it to learn different methods for building things. There are a lot of folks on the Forum who are happy to answer questions.

-

Progress, slowly but surely! The starboard side rat lines are finished. Half way there! The forward ratlines were tied with 0.012 inch (0.3 mm) brown polyester rope. The polyester is springy and the knots were untying themselves as fast as I could pull them tight. The clove hitches on the center shroud weren't much of a problem, but the lark's head (cow hitch) knots on the outer shrouds were horrible. I had to put a tiny drop of Duco Cement in the loose knot and then pull it tight and hold until the glue set (20-30 seconds). CA gel would probably work but you would have to be fast - one slip and it could set before the knot is tight or in the right position. I looked through my modeling materials and found a small spool of what appears to be cotton rope of about the same dimension. It was left over from a previous kit - or perhaps this one! I used this for the after ratlines, and used simple overhand knots. After I pulled the knots tight I put a small drop of diluted white glue (1:1 with water) on them. The white glue soaked in and fixed the knot after it set for half an hour or so. This allowed plenty of time to reposition the knot and pull it very tight. It was MUCH easier than trying to use the polyester! **** Falconer's Universal Dictionary of the Marine (1769) has this to say about "RATTLINGS, enflechures, certain small lines which traverse the shrouds of a ship horizontally, at regular distances from the deck upwards, and forming a variety of ladders, where by to climb to any of the mastheads, or descend from them. Hence the term is apparently derived from rath, an obsolete word, signifying an hill." Webster's Third New International Dictionary says "rat-line also rat-lin or rat-tling [origin unknown] 1. or ratline stuff : small, usu. 3-stranded, tarred rope used for cross ropes on ship's shrouds. Webster thinks rath is an Irish earthwork fortification, perhaps on a hill? "Fairy denizens of rath and hill." And now we know.

-

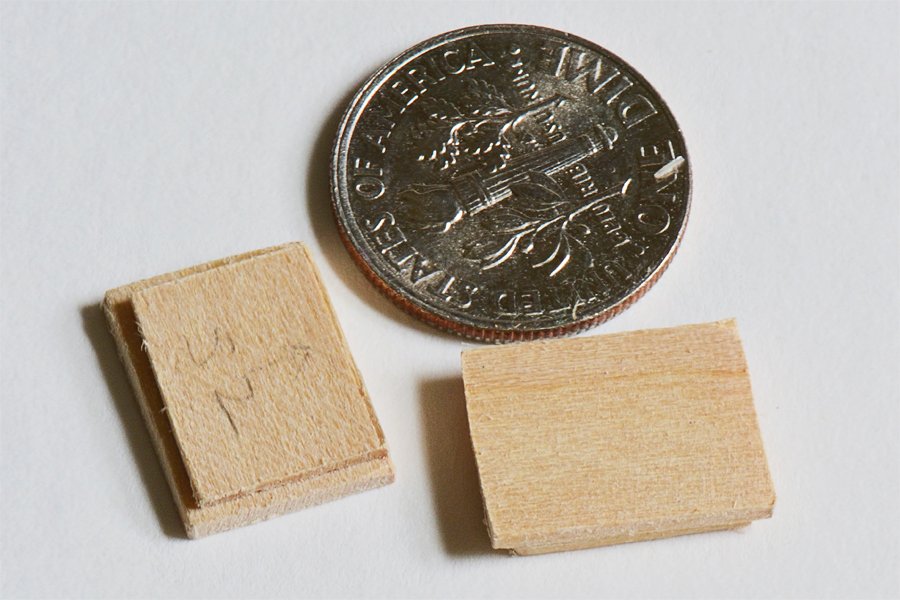

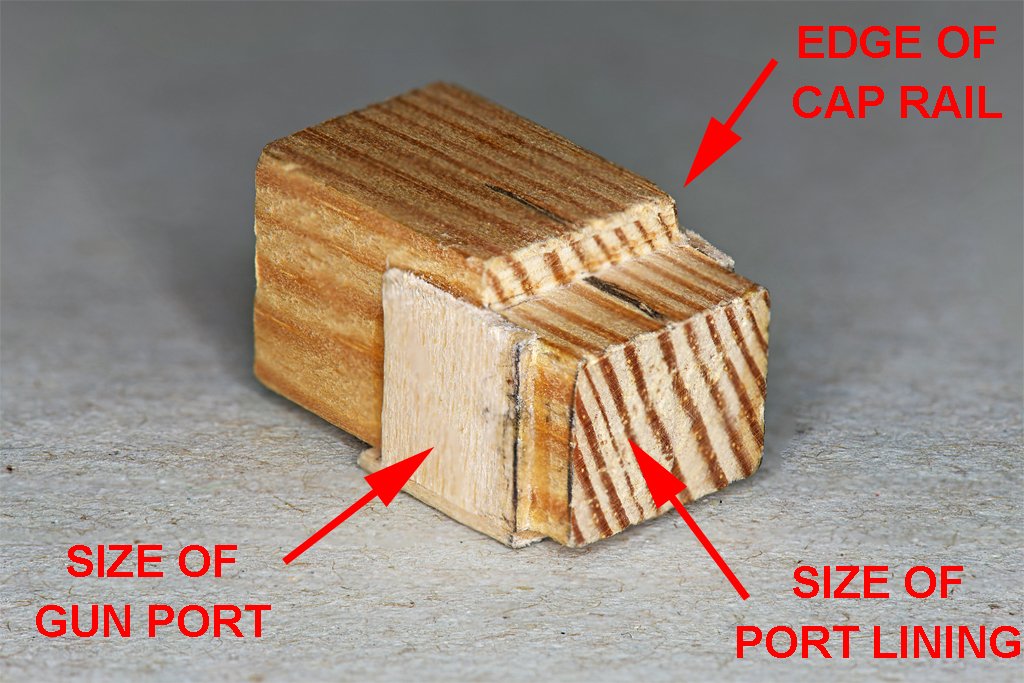

Mark, I was worried about getting all of the gun ports exactly the same size. I made a gun port tool from some scrap wood to ensure that all of the ports came out the same. Can't say this was my invention - I saw it in a book about building the hull of ship models. On the Albatros build the gun ports were cut immediately under the cap rail. The tool fit under the cap rail to the point marked "edge of cap rail," The surface with the black centering mark slid under the cap rail. The gun port opening was cut just large enough for the part marked "size of gun port" to slip fit through. I used files to open the original small drill hole to the right size and shape for the tool to be inserted until the edge marked "edge of cap rail" fit against the cap rail. Then I built up the port lining inside the bulwark so the part marked "size of port lining" slip fit into the lining. The gun port lids fit into the opening and rest against the port lining. The trick is to remove material from the planking slowly until the tool fits tightly into the opening. Here are a couple of pictures showing the results. On the left you can see the port linings inside the port opening. On the right is the view of the inside of the bulwarks showing the lower cill (lighter color wood) and the vertical linings (darker wood) inside the bulwark framing around the gun port. The gun port lids had a thin inner layer just large enough to fit into the lining/cill opening, while the outer layer fit tightly into the port opening and rested against the lining/cill. Hope this helps.

- 257 replies

-

I agree with Bill. Don't worry about it. After all, we have examined Chapelle's drawings of the Lynx and Musquidobit and he has drawn the rake angle of the main mast a bit greater than that of the fore mast. So maybe he changed his mind? We will never know what the actual rake angles were. Who knows, maybe what you have decided on is what the vessel really had?! I posted that Chapelle quote with chagrin because I have been reading over everything I could find about this vessel and had missed this bit at least several times!

- 257 replies

-

Mark, I just came across something about the Musquidobit in Chapelle's "The Baltimore Clipper" (page 82): "Her spars rake very sharply aft and both masts rake the same."

- 257 replies

-

Carriage Gun Rigging

Dr PR replied to Dr PR's topic in Discussion for a Ship's Deck Furniture, Guns, boats and other Fittings

Mondfeld's Historic Ship Models (page 167) says the breeching ring was found on English cannons from the late 18th century and early 19th century. But where did the guns on the Lynx come from? There probably is no record of that, other than they were put on a vessel built in America. Then did the British change out the guns on the Lynx/Musquidobit after it was captured? I looked for the history of the vessel after it was captured and didn't find anything, How long was it in British service? -

Best White Wood Glue For Ship Building

Dr PR replied to OldeManToad's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

vaddoc, Duco isn't what I think of as a contact cement. The contact cements I have used are rubbery and sticky when set. You apply it to both surfaces, let it dry until it is tacky, and then press the pieces together. They bond on contact, hence the name. Duco is a solution of nitrocellulose in acetone. The liquid flows into pores and cracks. When the acetone evaporates the nitrocellulose hardens to hold the parts together. In this respect it is just another glue for porous materials. Acetone is very volatile and evaporates quickly, letting the glue set up quickly. However, because it leaves a film on smooth surfaces it can be used to glue wood to metal and metal to metal. However, this is not a really strong bond. The hardened nitrocellulose can be knocked loose from the smooth surface with a blow. -

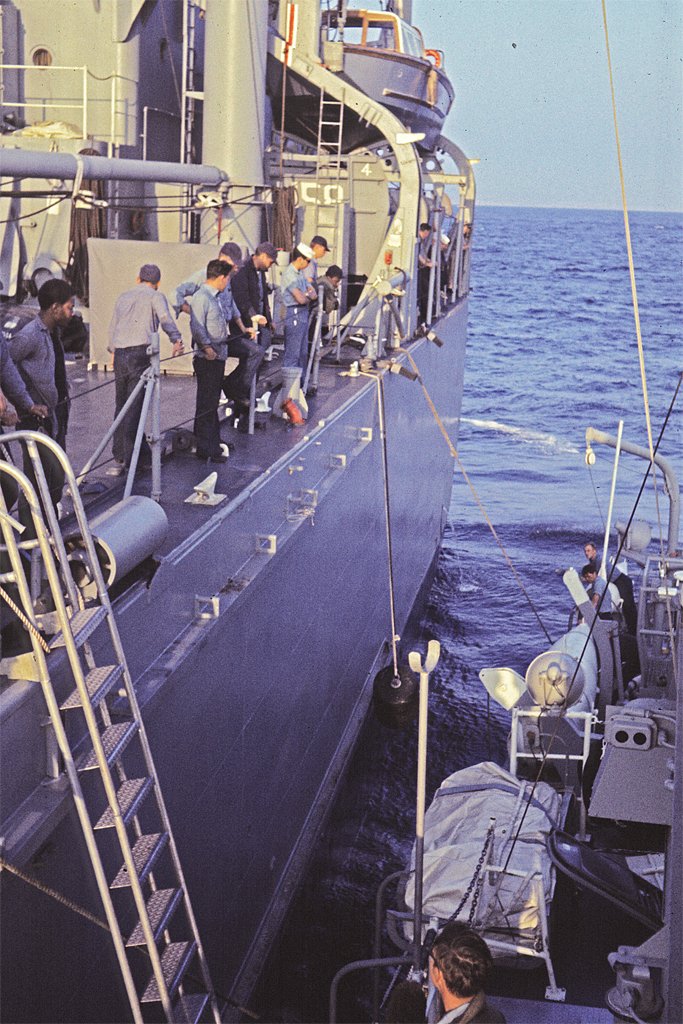

I suspect I have given the impression that everything we did on the Cape was a failure. Much of it was, because the ship was poorly designed for the things it was asked to do. We did have several successful training sessions for everything from streaming mine sweep gear to shipboard firefighting. And for me it was something of an extension of Officer Candidate School where I got some valuable ship handling experience. But one of the more unusual missions called for the Cape to carry Marine commandos close to shore the night before a training assault landing at the Marine Corps Base at Camp Pendleton north of San Diego, California. We rendezvoused with a LST (Landing Ship Tank) in the late afternoon and took aboard the Marines and their boats and gear. Notice how much larger the LST was compared to the Cape (on the right in the photo) – and LSTs weren't considered large ships, only about 300 feet long, or three times as long as the MSIs and 13.5 times a MSI's displacement. That night we proceeded in close to shore where the commandos launched their boats and disappeared into the darkness. Then we motored back out to sea to wait for the morning's assault to begin. Mission accomplished! I guess the MSIs were perfect for this type operation. They were shallow draft and could pass for a fishing boat at night. And if the enemy did spot them and open fire the ships certainly were expendable. We didn't have to wait long before several ships began shore bombardment at first light. It was my first exposure to (relatively) large caliber gun fire. A destroyer was about half a mile from us, and when it fired the 5"/38 guns we saw the flash, followed a few seconds later by the BOOM! The sound hit me like a punch in the gut. That was a surprise! It was just an introduction to Naval Gunfire Support (NGFS). When I was on the Oklahoma City in Vietnam we conducted NGFS for six to eight weeks at a time. I lost my high frequency hearing while standing watch for hours with the 5"/38s and 6"/47s firing only a few yards away. When I see films of Marines landing on Pacific islands in WWII with battleships blasting away nearby I wonder if those guys were totally deaf by the time they hit the beaches? We were ordered to patrol the boundary of the assault area to keep civilian craft out of the restricted zone. We motored back and forth along the south end of the landing area for the rest of the day with few boats coming near. But after a while a huge yacht came up over the horizon headed north at about five knots. It was almost as big as the Cape, and possibly even larger. We had signal flags flying to warn vessels to stay away, but only naval craft would understand the code. As the yacht came closer we used the 12 inch signal lights to catch their attention, but it kept on heading directly into the invasion force. When it was a few hundred yards away we started sounding the ship's whistle, but we could see no one on the bridge. It was running on "iron mike" – a term for auto pilot. We pulled close alongside, sounding the horn and flashing the signal light. Finally someone appeared on deck from a cabin near the stern and raced toward the bridge. We tried to communicate by radio but they weren't listening to the marine frequency. Our Captain shouted at them through a megaphone, but the person on the yacht's bridge didn't seem to understand. Then, shouting as loud as he could to be heard over the Yacht's engines, he said "You are heading into a mine field!" There actually was a practice minefield in the landing area, and the big boy oceangoing minesweepers (MSOs) had started the invasion by sweeping the area. That message finally came across, and with a roar of engines the yacht turned west. As the hull rose to planing the boat raced off into the sunset at two or three times the Cape's maximum speed. Mission accomplished again! Twice in one day!! So the ship wasn't totally worthless.

- 489 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

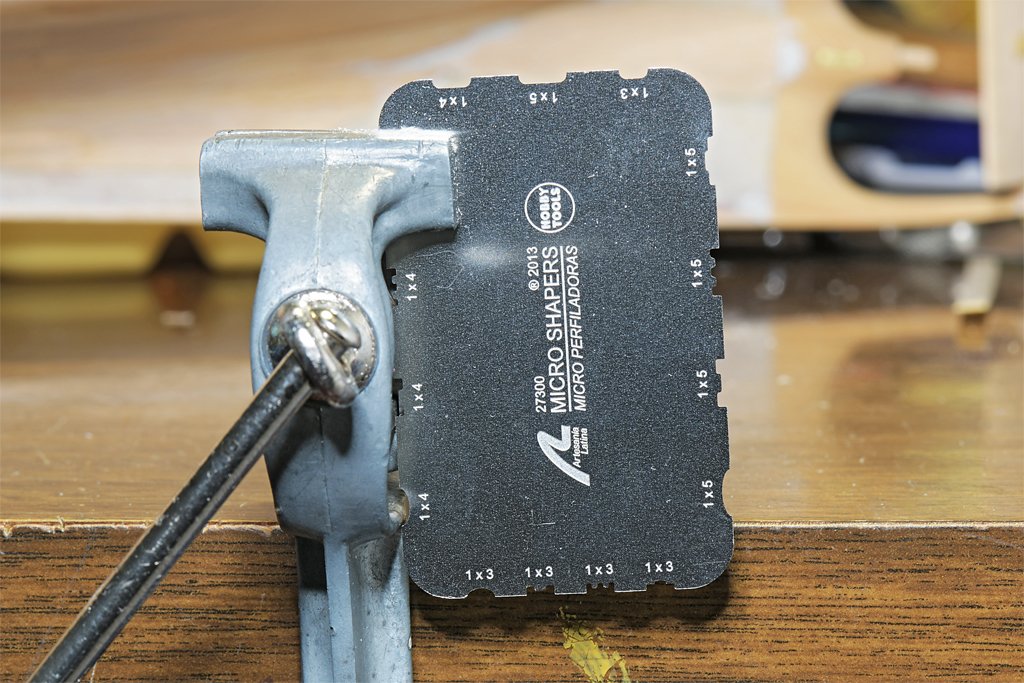

So how am I supposed to create this sheathing with the scale 0.005 inch (0.13 mm) gaps between the planks? I quickly abandoned the idea of using 0.005 inch thick brass shims to space the planks. Instead I decided to bevel the edges of the planks and jam them together, leaving a visible gap at the top surface. A couple of years ago I was looking through build logs on the forum and was envious of some of the models that had elaborate moldings instead of plain rectangular trim. I knew that this effect was achieved with draw plates with a variety of cutouts, so I bought four Artesania Latina draw plates for future use. Well, the future is here, and I used the 1x4 mm cutout to round the edges of the 3.9 mm wide sheathing planks. This worked petty good. The "corduroy" effect is very subtle, but with the proper lighting angle it is noticeable. I have finished the port bow and the port aft sections above the water line. The very thin basswood planks bend and twist to shape without the need to use heat, and the glue is good enough to hold them in place without clamps. But I did use blue masking tape to hold the planks in place until the glue (Sig-Bond Cement) set. I need to be sure to remove excess cement between the planks after they are positioned. It fills in the gaps and is hard to remove after it has hardened. I use the tip of an old #11 blade drawn backward (top or flat edge first) through the gap to scrape out any glue that flows there. Austin Cox (the current Cape owner) has confirmed that the sheathing planks that remain at the bow of the ship today were not tapered. They are the original 7 1/4 inch wide planks, and he has replaced at least one of the original parts. So I will complete the sheathing planking below the water line without tapering the planks. Fitting and trimming the pieces to the bilge keels, garboard strakes and keel should be interesting! It definitely will be contrary to the traditional modelling dogma of tapering the planks precisely to meet that preconceived "ideal."

- 489 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Vaddoc, That is a very good question! The blueprints don't say anything about the function of these "sheathing" planks. However, I can make an educated guess. The sheathing extends above the waterline in places where heavy objects (anchor, minesweeping floats, acoustic minesweeping device, etc.) are hoisted over the side. So it seems to be there for protection of the hull planking. Minesweepers often operated in shallow waters (especially an "inshore minesweeper" or MSI) where they might run aground. The entire hull surface below the waterline is covered by the sheathing. I guess the sheathing below the waterline is there to protect the hull planking. The sheathing itself provides no water tight integrity given that the planks were placed with 1/4 inch (5 mm) gaps between the planks. The blueprints specifically say that nothing is to be placed in the gap. But the sheathing was installed over a waterproofed cloth covering on the hull planking. That would provide some protection for the hull planks. Maybe the sheathing was there to hold the water tight cloth covering in place? I know the larger ocean going minesweepers (MSO) had similar sheathing along the sides where heavy objects were handled - I have a photo showing this. So this seems to be a common feature of wooden minesweepers after WWII. But on the MSOs the sheathing planks were placed vertically - with gaps between them - instead of horizontally like the MSIs. The MSIs were built in shipyards that specialized in wooden fishing boats. I wonder if they had the same type of sheathing? So far I have found no answer to that question. **** Scale (1:48) planks are VERY thin - 0.015 inch (0.4 mm). They curve and twist to fit the hull curvature with little effort. Just the glue holds them in place without any clamps. But I have been taping them down with blue painter's masking tape to give the glue a chance to set.

- 489 replies

-

- minesweeper

- Cape

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Best White Wood Glue For Ship Building

Dr PR replied to OldeManToad's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

I have been building wooden models for at least 70 years, and have used a lot of different glues. Way back then I used Testor's wood glue. I don't know if it is still made, but Duco Cement is the equivalent. It is nitrocellulose dissolved in acetone. It is one of my primary wood glues because it sets in 20-30 seconds, giving time to reposition parts. It makes a good bond, leaves a shiny film, and can be loosened with acetone. I used it for most of the Albatross topsail schooner build - that hull is about 40 years old now. My local hobby shop (killed by the pandemic and on-line sales) specialized in radio controlled airplanes, but also carried a selection of wooden ship model kits. The wood glue of choice there was Sig-Bond aliphatic resin used by model airplane folks. It is a very good white wood glue that leaves very little (if any) visible film. It can be loosened and washed up with water. Heat also liquifies the dried glue, and it resets when it cools (maybe not as strong as the original bond). It is what I am using on the MSI build. I recently used Titebond Original for the Vanguard 18 foot cutter model. This is what Vanguard recommended, and many on this forum recommend it. It is pale yellow and leaves a slight film. It can be loosened with heat as Gregg said, but I found that it will also loosen with water. If you loosen it with heat it will reset again with a good bond when it cools. I use Elmer's Glue-All white glue in places where I do not want any visible dry glue. Office Works school glue seems to be the same. They clean up with water. These are not as "strong" as the other glues mentioned above. I use these glues diluted 1:1 with water to fix rigging knots with threads like cotton and silk that soak up the glue. Shellac can be used to fix knots in ropes and to shape the curves in ropes. It dries very quickly and is soluble in alcohol. It is also used as a wood finish. NOTE: None of the glues listed above will adhere to polyester rope! They do not soak into the polyester thread and just form a weak coating that will come loose with a bit of pulling. Duco Cement does dry to a hard coating that is stronger than the other glues. I have used Locktite CA gel (cyanoacrylate or "super glue") when I need a very quick setting glue in small spots. It usually sets in 5-10 seconds, but the latest use took 30-40 seconds. I don't like super glue - the vapors irritate my eyes. High heat will weaken or loosen CA. It leaves a white residue when it hardens. None of the glues listed above are good for wood to metal or metal to metal. If you want to glue wood to non-porous materials like metal or plastic the only good adhesive that I know of is two part epoxy. I am reminded of the slogan on inner tube repair kits from the 1920s and 30s. "If you don't want it on, don't put it on!" It will clean up with rubbing alcohol (isopropanol). Hardened epoxy can be filed and drilled, but is not as hard and strong as metal. You should brush/sand the metal/plastic surface to be glued to roughen it a bit so the glue can adhere properly. I use liquid two part epoxy "paint" to seal the inside of planked wooden hulls. It soaks into the wood, bonding planks edge to edge, and planks to bulkheads. It makes a rock solid hull that will not develop cracks between planks as the wood swells and shrinks with changing humidity. For the topsail schooner hull I used epoxy paint flying model airplane builders use to seal wood from fuel. On the MSI build I used the clear two part resin used to form clear "plastic" layers on counter tops. **** Although all of these glues will adhere to painted surfaces, the bond is only as strong as the paint bond to the wood/metal. Remove paint from surfaces that are to be glued. None of these glues will adhere well to greasy or oily surfaces (including finger print oils). Some won't adhere to wet surfaces. Clean and dry the surfaces before gluing. -

Mark, Your mast positions look good! It was common on ships of this period to make the transom (fashion piece) a bit wider than the hull, and with a rounded outer edge. Then a decorative piece was placed against the hull planking and the front side of the curved transom outside the hull planking. However many schooners of this period had very little decoration at the bow or stern. Chapelle's lines drawing in The Baltimore Clipper (page 83) shows this curved outer edge of the transom extending slightly beyond the hull planking (the drawing in your post #134 above).

- 257 replies

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.