-

Posts

1,366 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by JacquesCousteau

-

Hello - very new builder

JacquesCousteau replied to Rowland_Hill's topic in New member Introductions

Nice work! I highly recommend starting a build log, it's the best way to get feedback. -

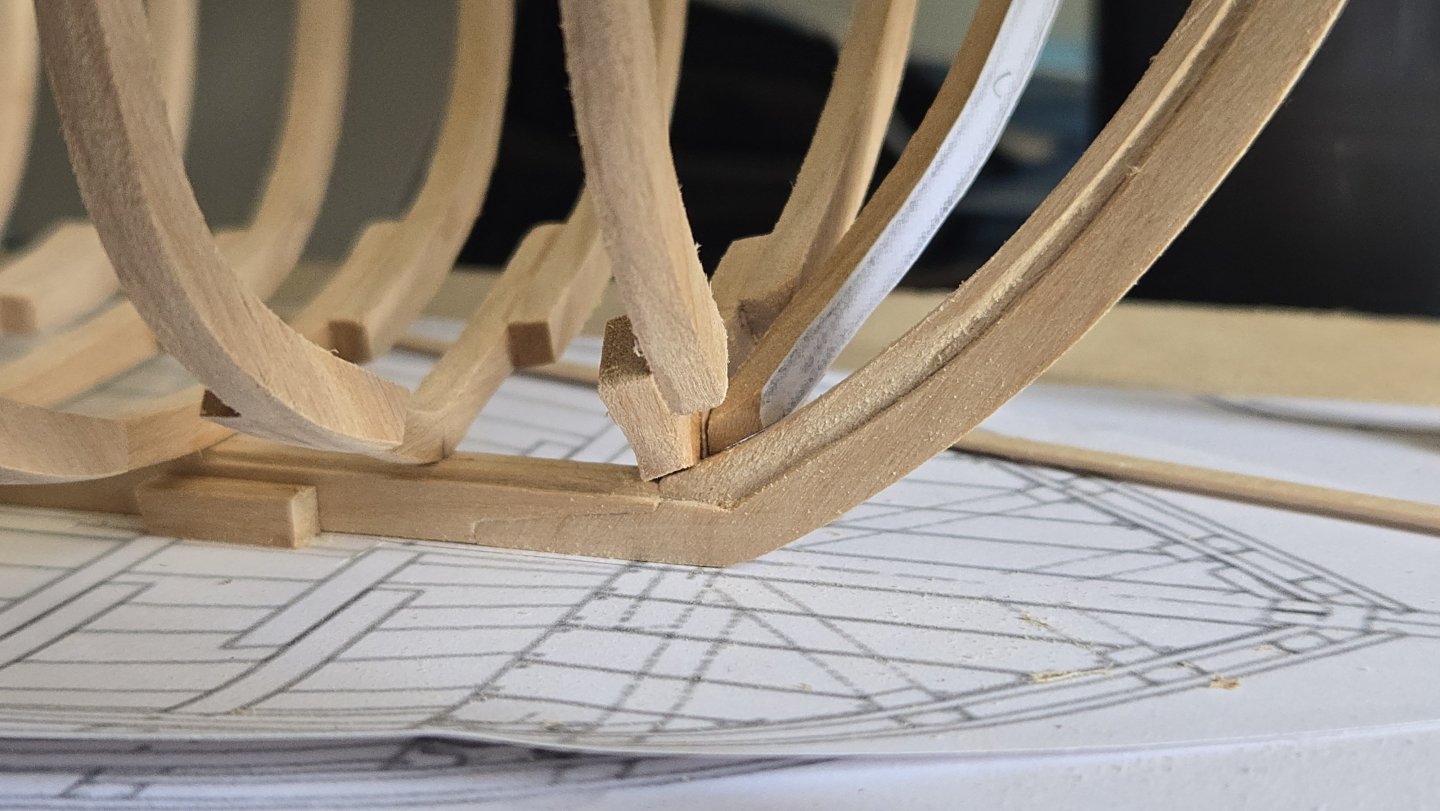

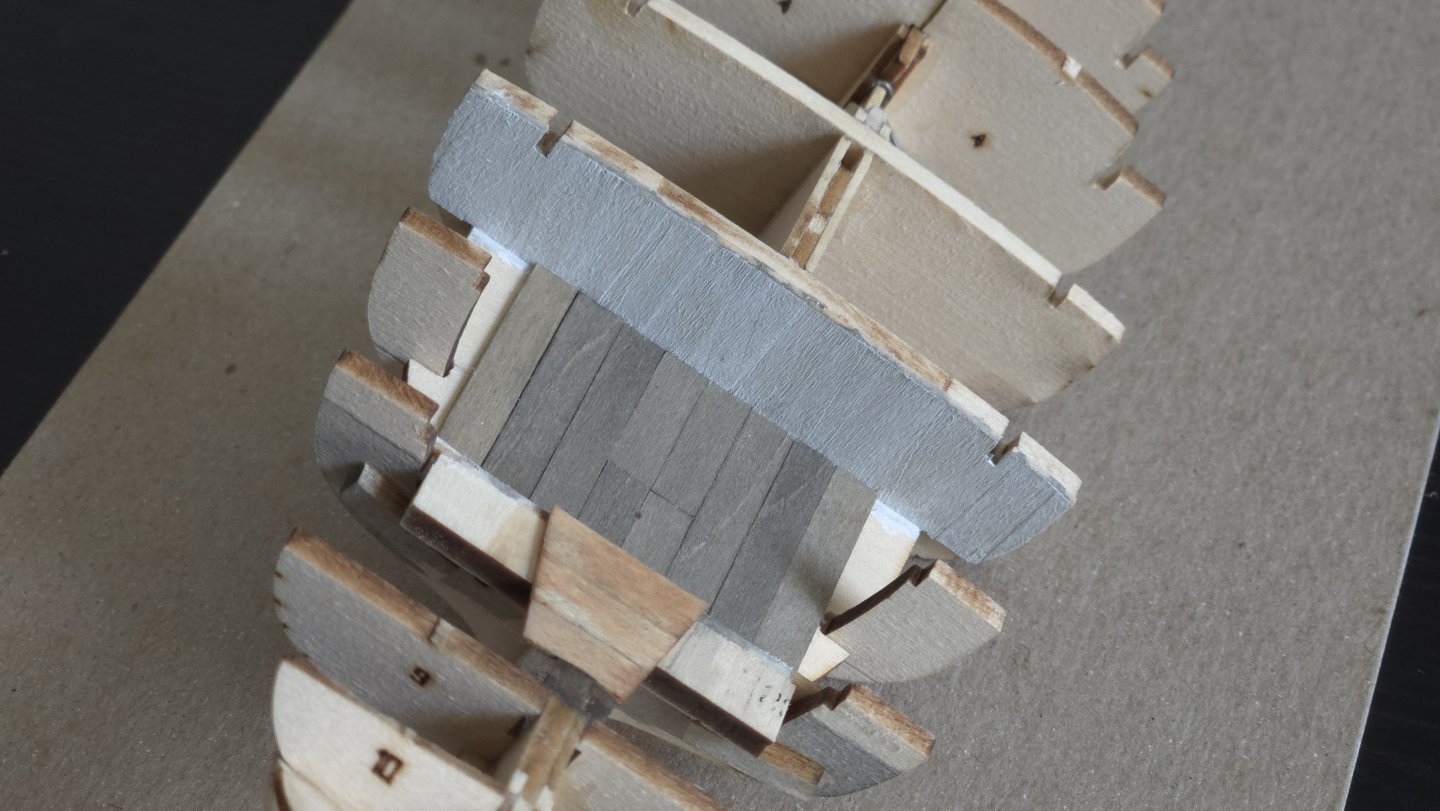

Thanks, Keith! I'll definitely do a test to see how it handles sanding--the interior bottom isn't faired yet and some frames need a good bit of sanding, so I'd hate to add the wire pin and find that it impedes fairing. I know I must sound like a broken record at this point, but the cant frames continue to give me a lot of trouble. As mentioned above, the D frames stuck out way too much, forming a bulge that would be impossible to fair without sanding nearly through the frames. In fact, trying to bend my thinnest batten around this point cracked the wood! I was going to shift the frames a little higher on the deadwood, but before doing so, I checked the height if the top frame end above the bottom of the keel against the plans, and found that the frames were already a good bit higher than they should have been. After some consideration, I ended up trimming material off the bottom, which lowers them slightly and brings the frames in a bit, getting rid of the problematic bulge in the hull. The issue now is that the frames are technically cut shorter at the bottom end than they are shown on the plans, even considering the width of the deadwood. That said, I then realized that the width of the deadwood on the cant frames would have to measured not across the beam, but at the same diagonal as the cant frames. Considering this, they're closer to what's given in the plans. In any case, they seem to be a lot fairer now based on running battens around them, although it's all a little hard to tell given how much fairing is needed. I guess I'll have to see how it goes when I get to fairing, and at worst will have to just cut them out again and make new ones. I've also started on cant frame C at the bow--just the port frame so far--and similarly am having a lot of trouble with it. I'm constantly shaping it slightly, offering it up to the hull and checking with battens inside and out, and trimming it again, while keeping an eye on the height of its tip. I'm not quite their yet, but, while I've trimmed a surprising amount off the bottom, it seems from the battens like it will fair up well? Anyway, I'm still enjoying the build, but as I've already mentioned quite a few times, I really wish the plan set had more accurately depicted how the cant frames intersect the keel/deadwood/stem, as this is really causing a lot of stressful confusion that could have been avoided.

- 139 replies

-

- ancre

- Bateau de Lanveoc

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

If it's not a restoration, then what is it? As mentioned above, it's basically impossible for anyone to help you on this without posting some photos or giving more specific information. Fregata Española is a generic term which, combined with the link you posted, suggests a generic decorator model. In which case, Chris is right that there really isn't any scale that would be accurate because the model itself isn't accurate. Maybe it actually is a more accurate model, but nobody here can know that without photos. If you need replacement parts and if it's a decorator model, you can just buy whatever seems like a reasonable size. A lot of vendors offer scale rope, blocks, etc in different sizes. If it's not a decorator model, you'll need something that's in scale, but again, nobody can offer any real help with the minimal information you've provided so far.

-

Welcome! I definitely suggest posting a build log.

-

Really fantastic work! I'm struck by the table and chairs--they may be some of the simpler constructions in this build, but they're made beautifully.

-

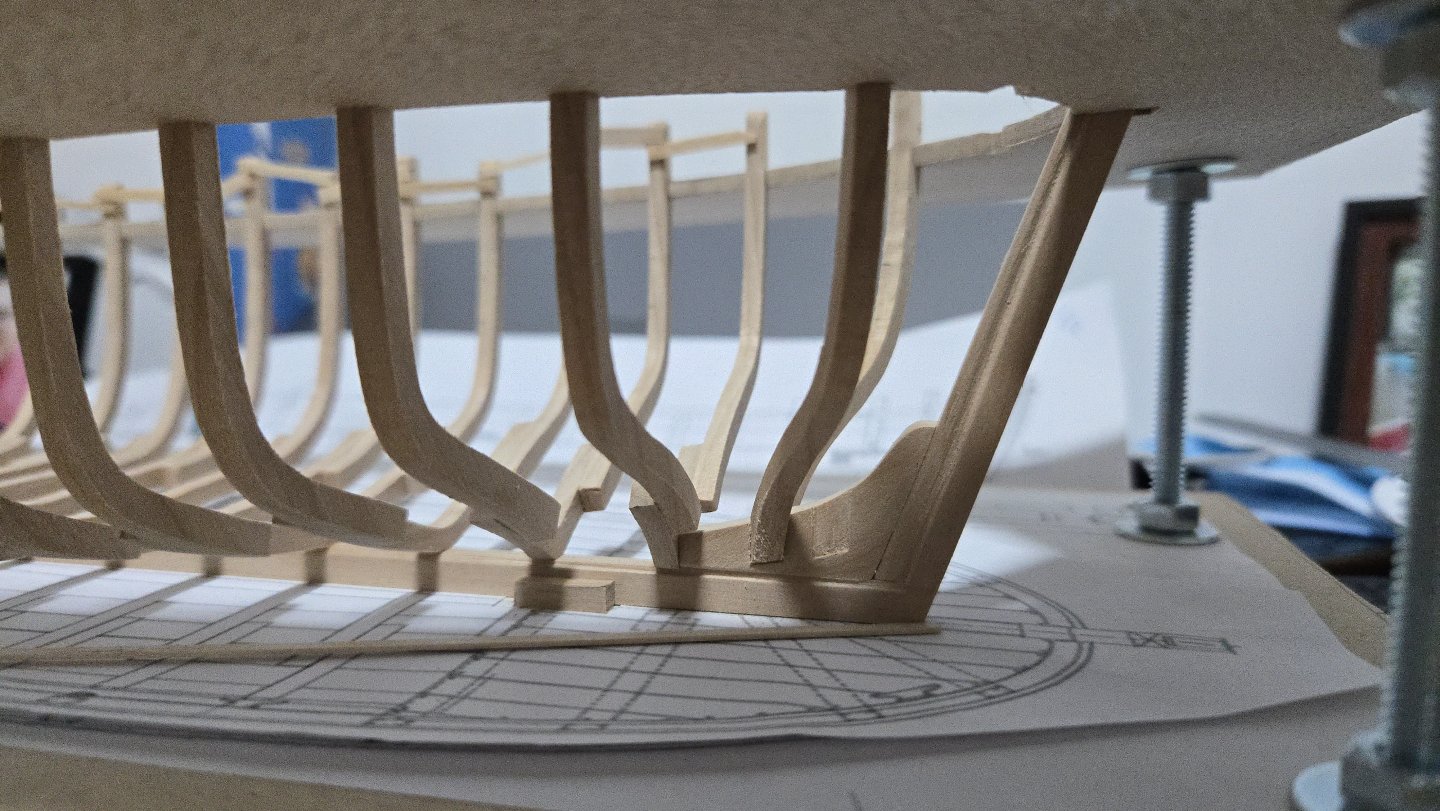

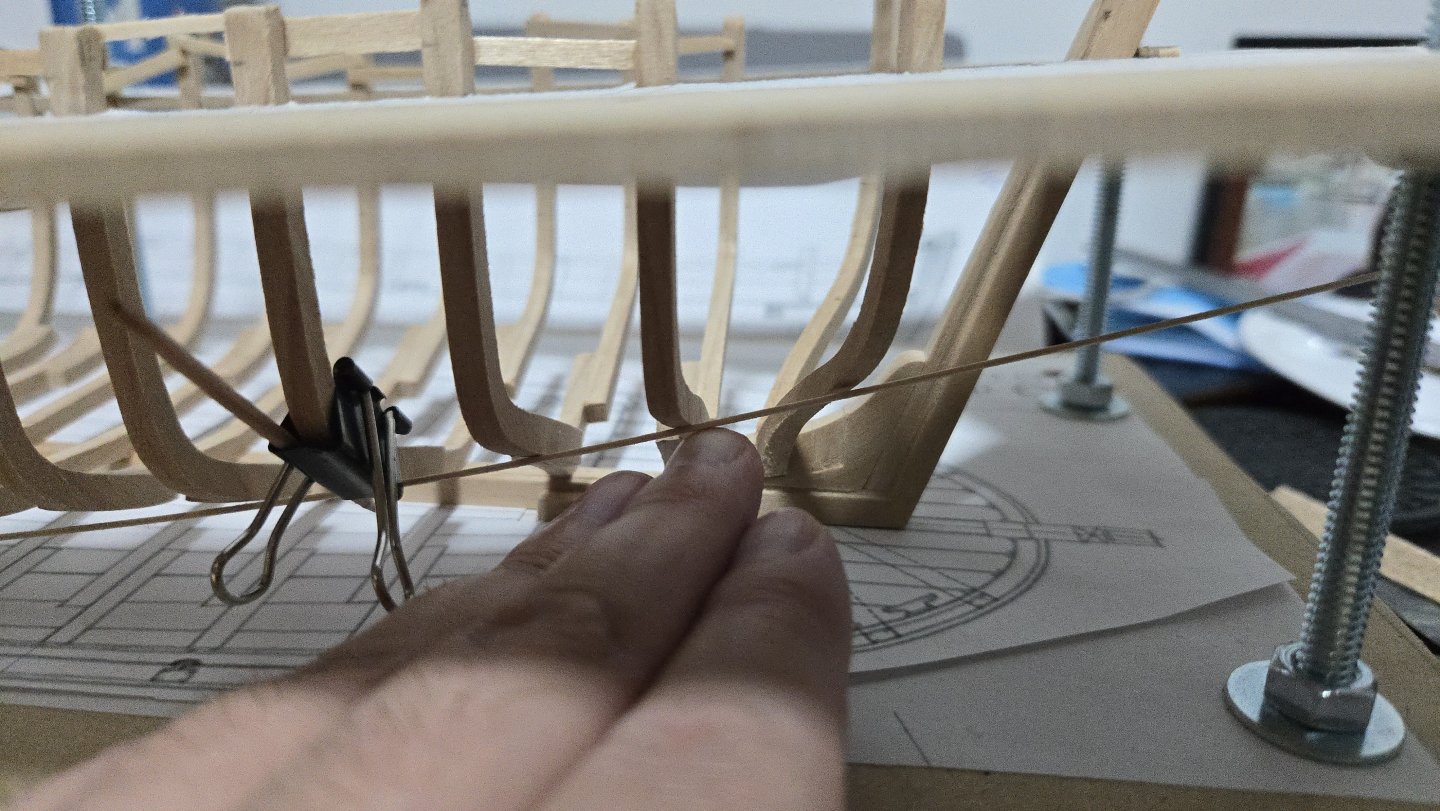

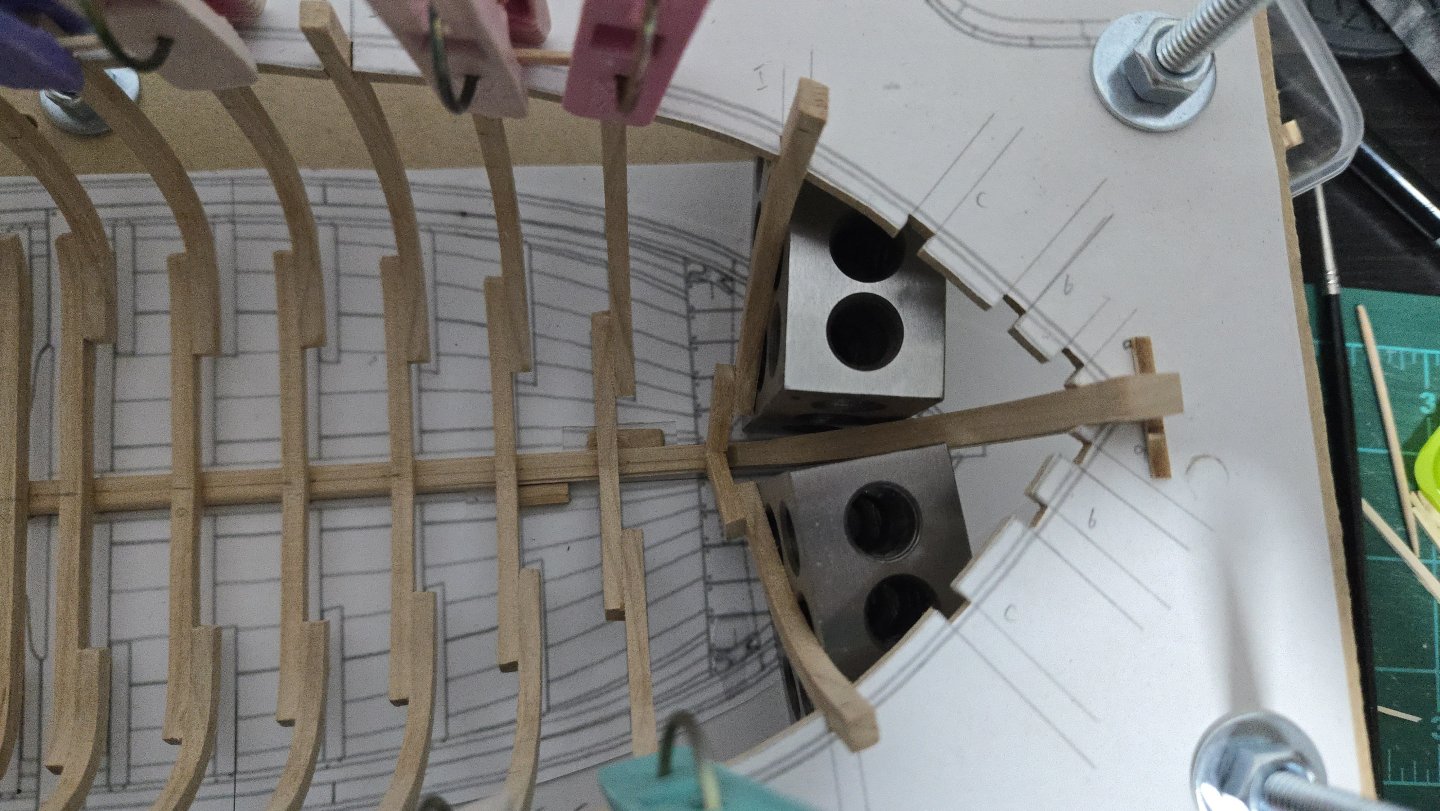

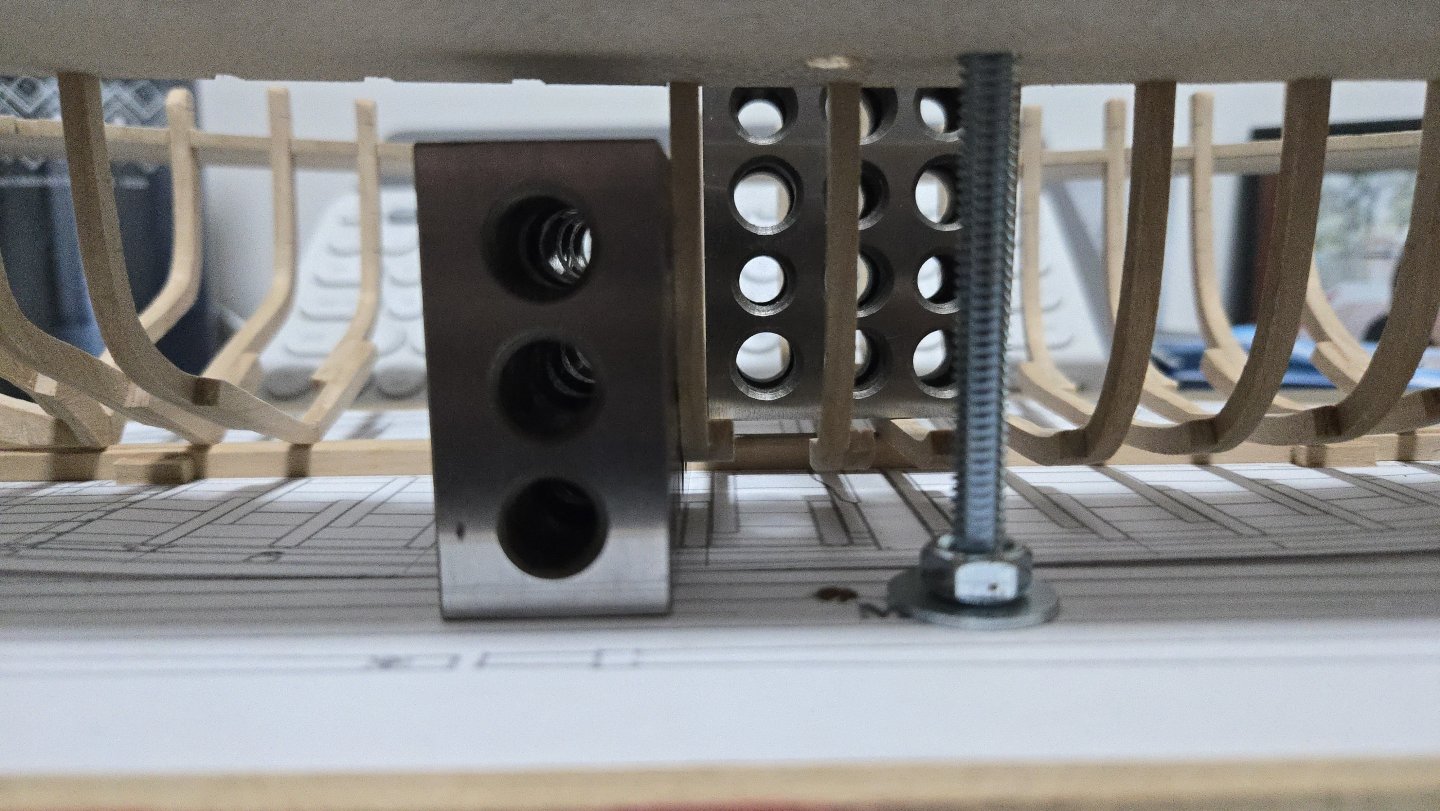

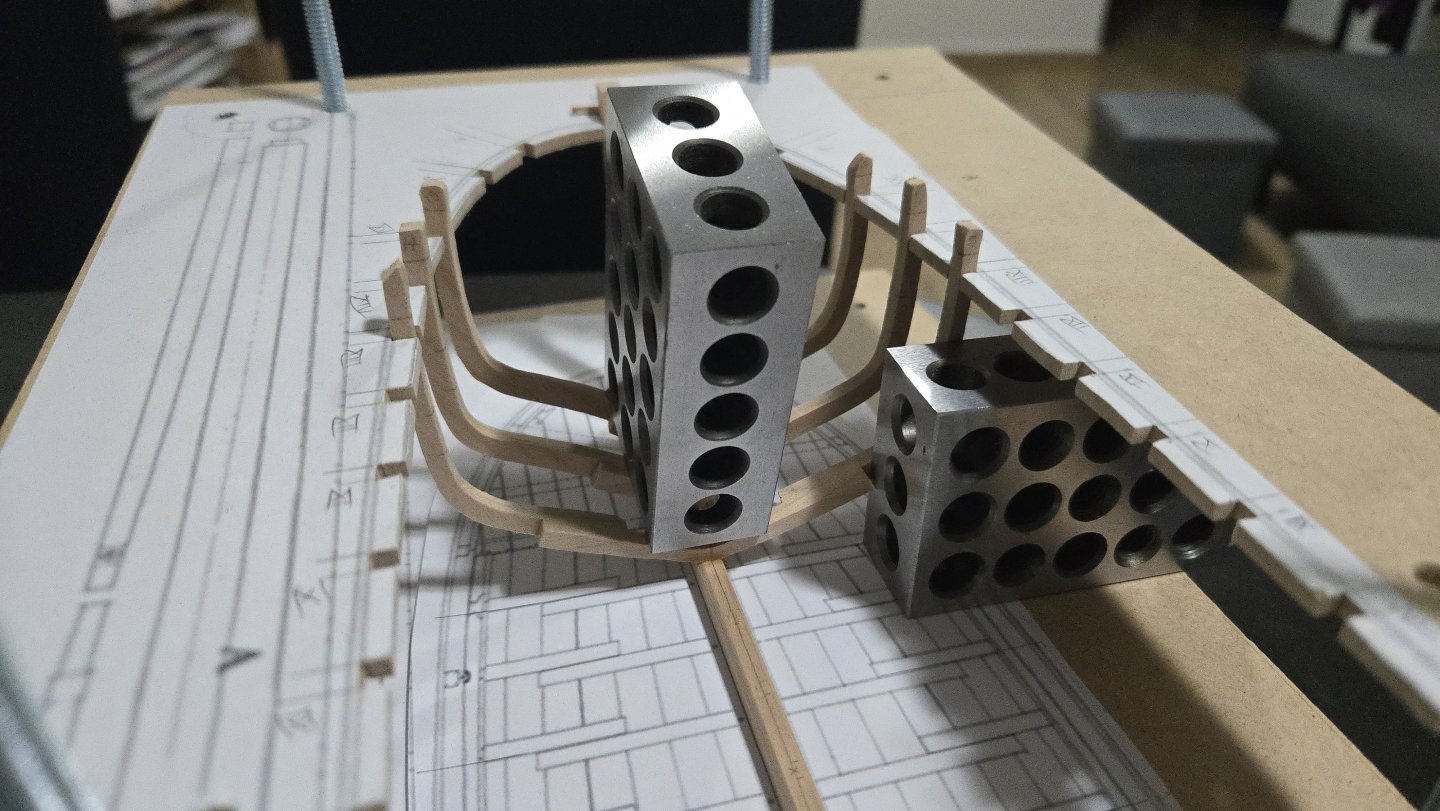

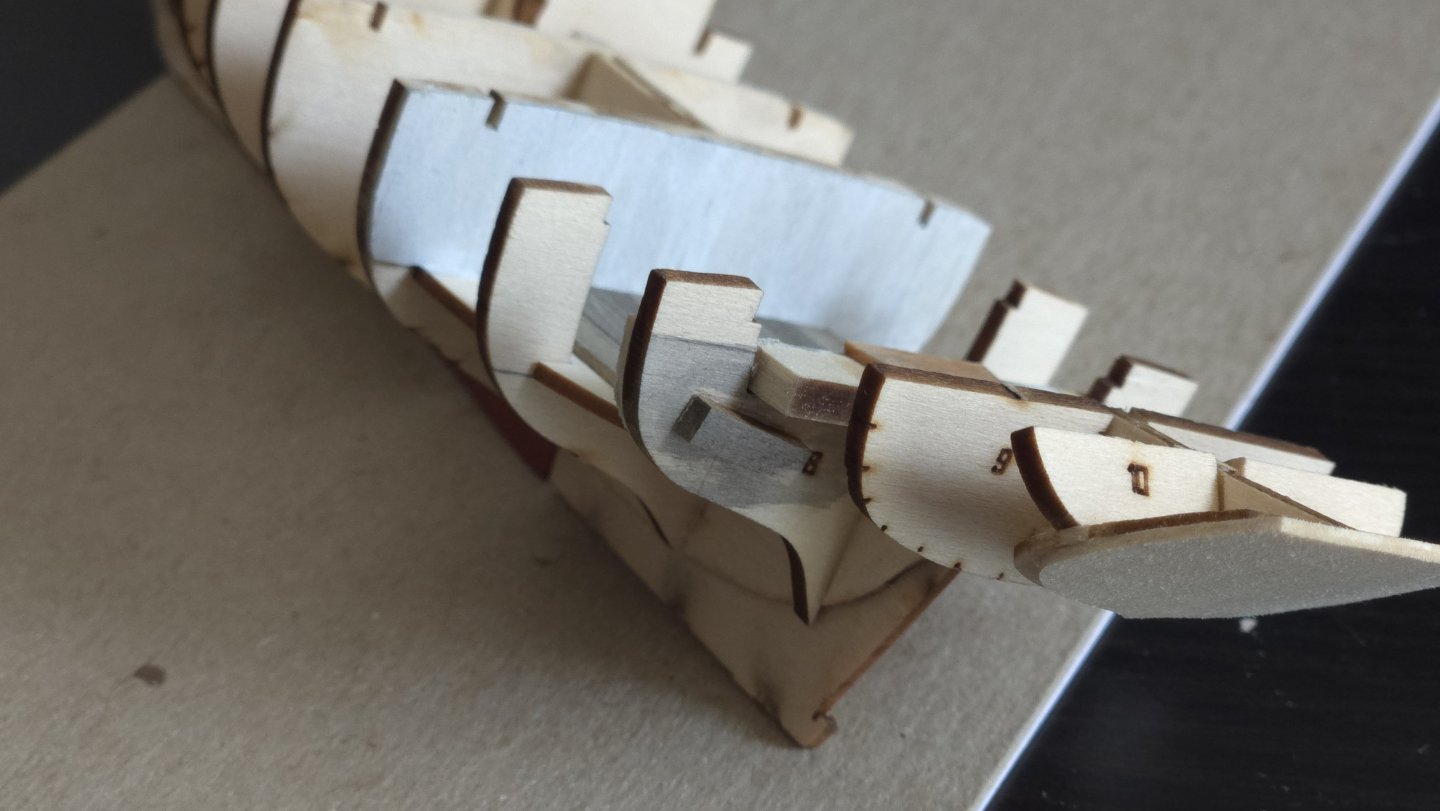

Thanks, all! Keith, I've thought about it, but am a little concerned that the parts are thin enough I'd need to sand down toothpicks or something to a consistent size to serve as pins. A draw plate might be useful, I suppose. I decided to start with the aft cant frame pair D, as they've already been shaped. Gluing them in place was a bit tricky: I used the 3-2-1 block to again provide a vertical surface, and used a clip at the top to keep the frame from dropping too low. The result looked nice! However, I then decided to check the fit with a batten. It's a bit tricky to tell, because the hull hasn't been faired yet and I don't really have a very effective clamp to hold the planks to the frames, but the cant frame seems to be a bit too low, forcing the plank to bend down in a way that goes against the preceding curve (not to mention making it much harder to bend the plank back again to meet the sternpost. So, I think I need to unglue the D frames and reglue them just a hair higher up. Also, I clearly need some more effective clamps before I get to the planking. How do people clamp onto POF hulls?

- 139 replies

-

- ancre

- Bateau de Lanveoc

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

There's a helpful list of banned manufacturers here: Unfortunately, both Unicorn Models and Modelship Dockyard are on the list, so neither model can have a build log here (although you can of course build them without posting a log). If you'd like to post a build log, it would be a good idea to check the list of banned manufacturers first and choose something that isn't banned.

-

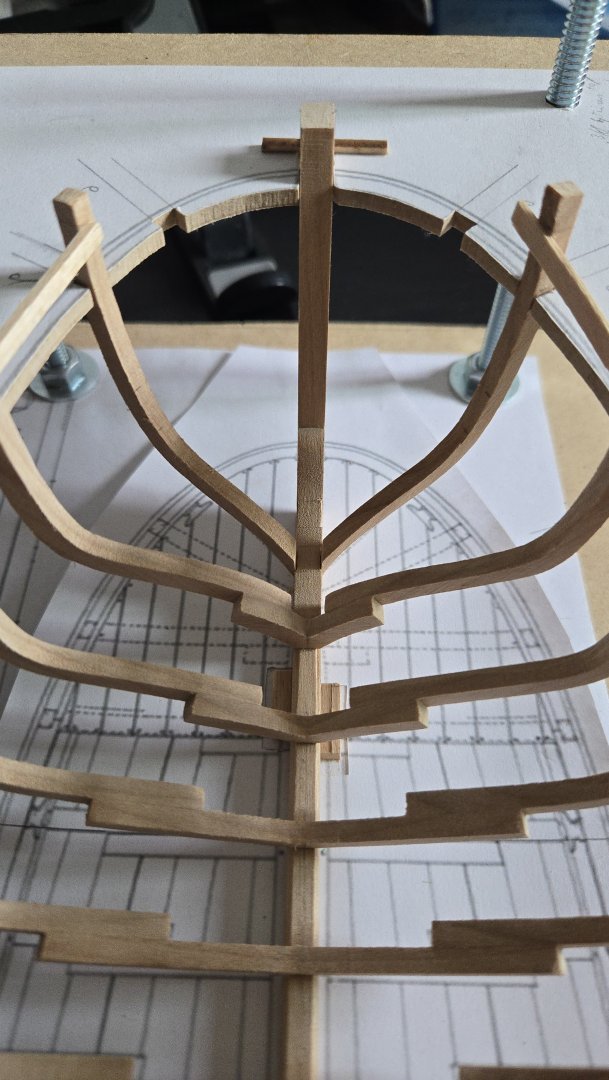

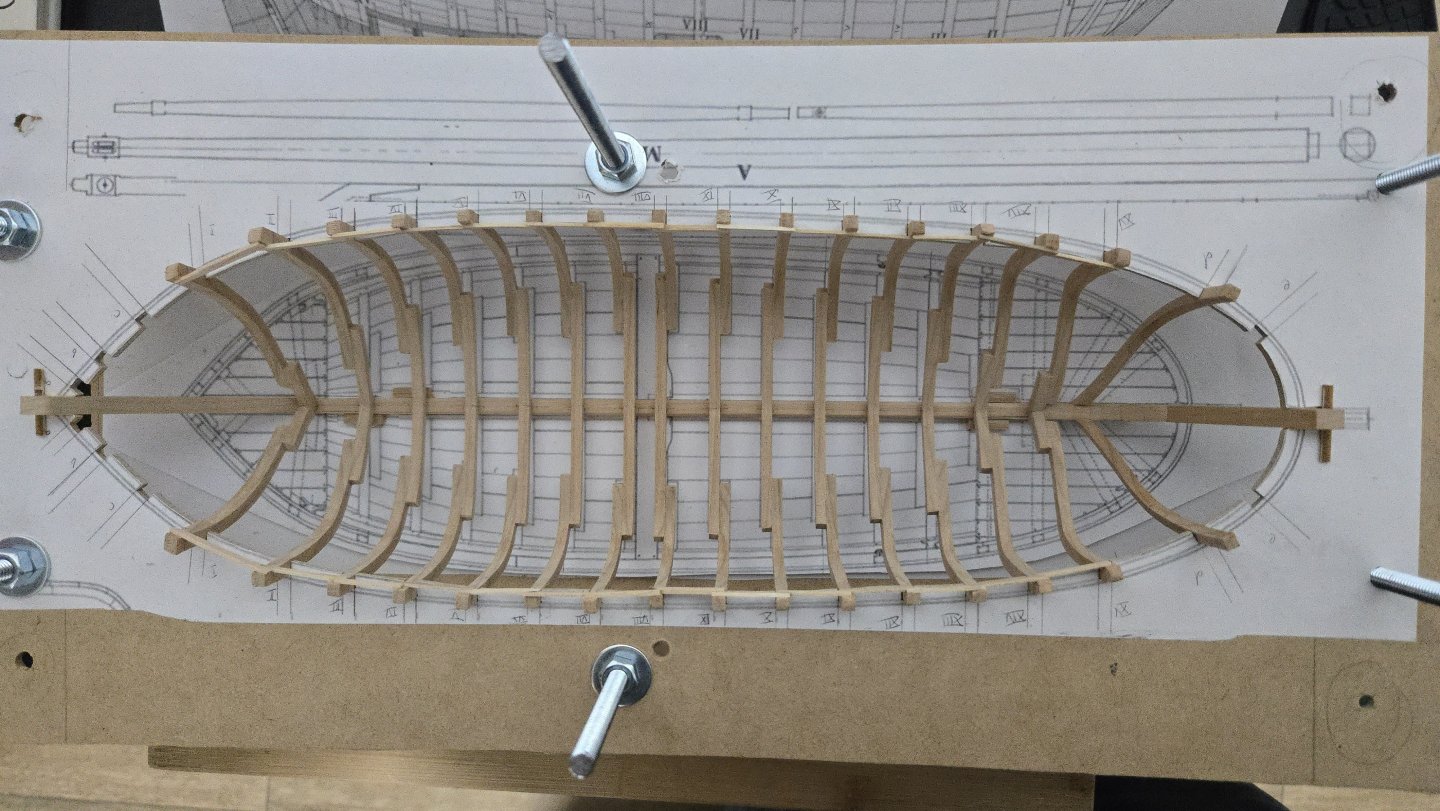

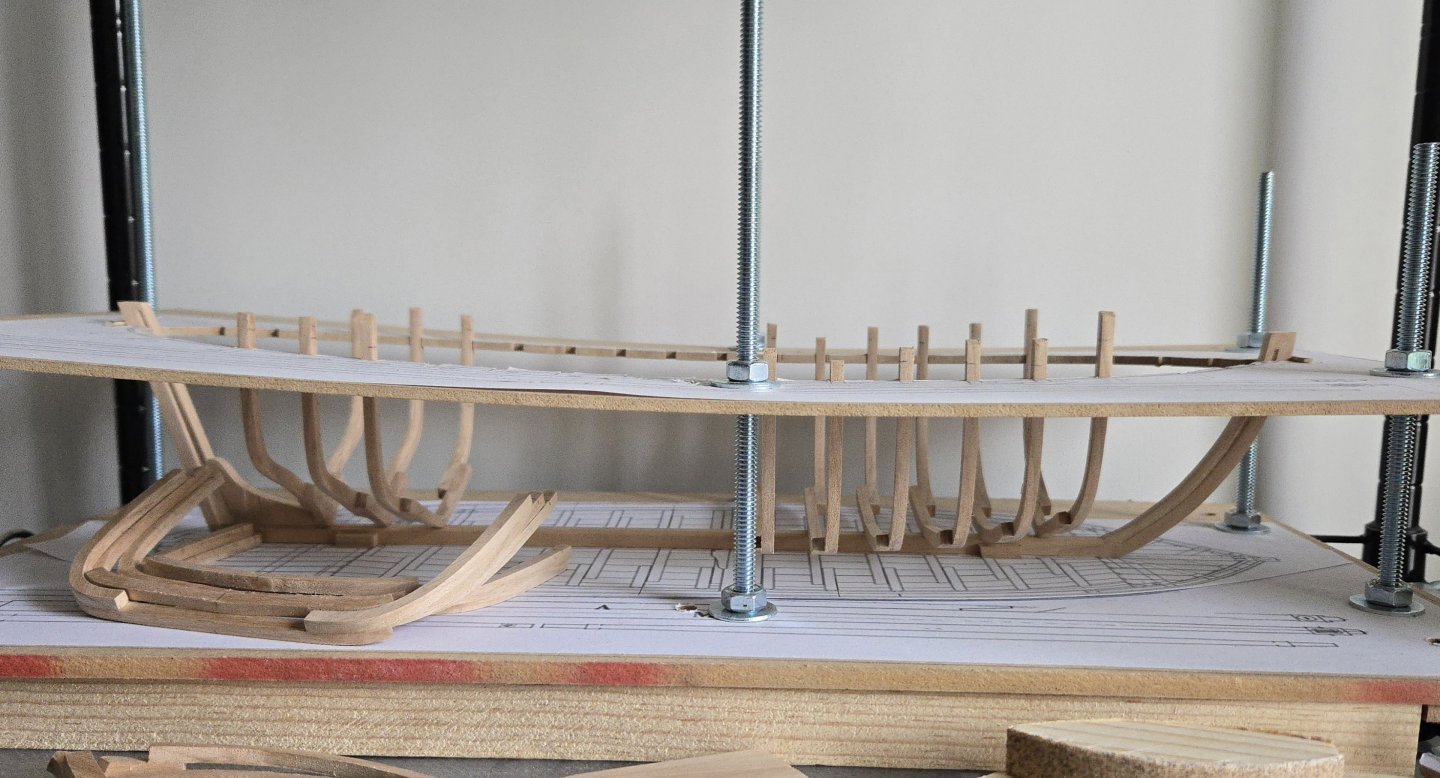

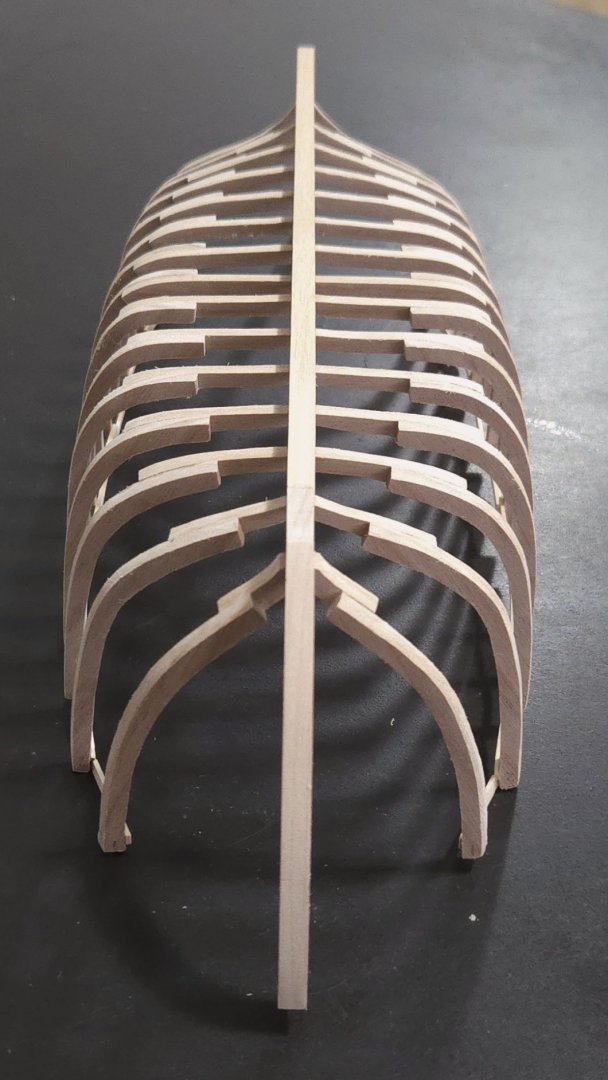

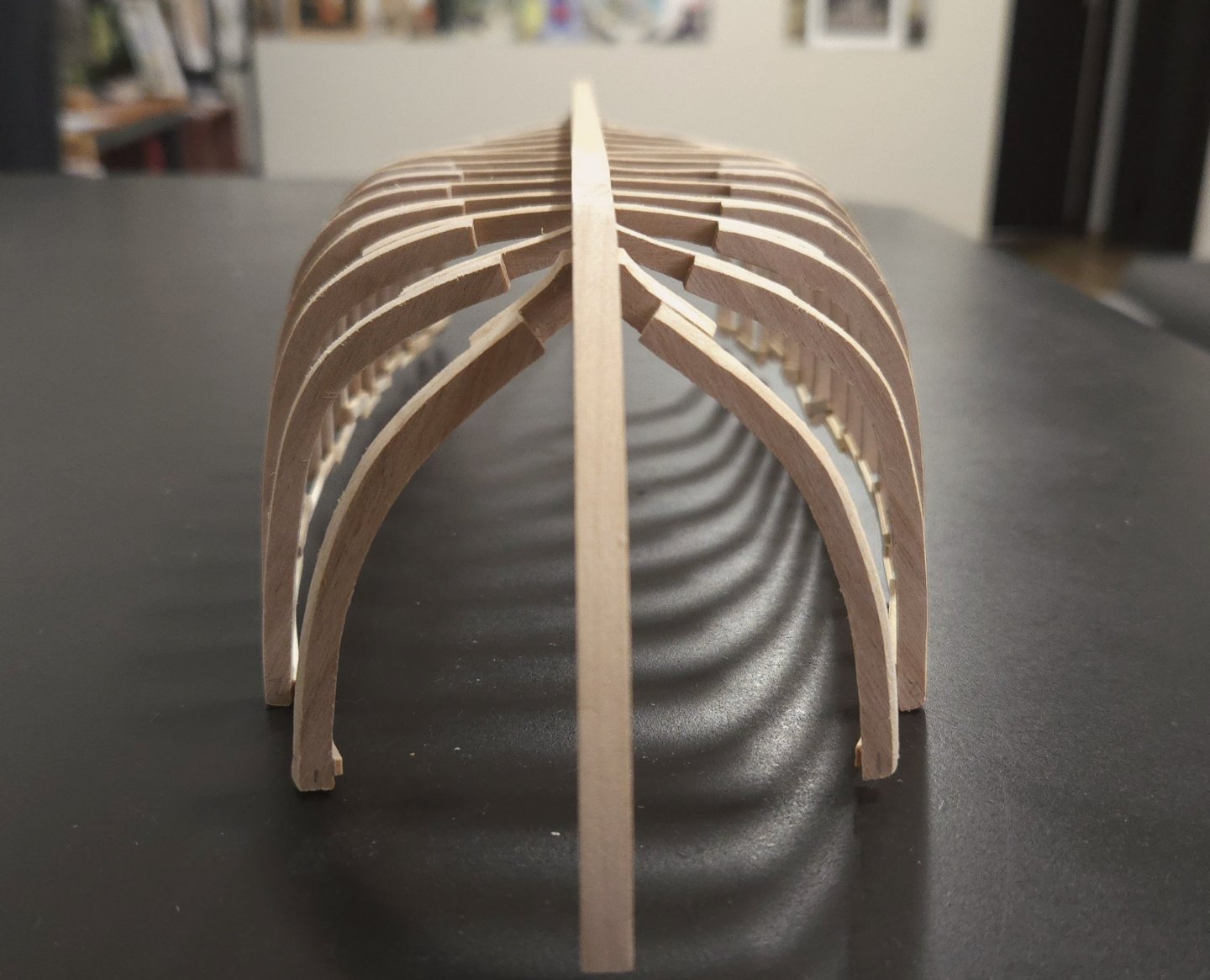

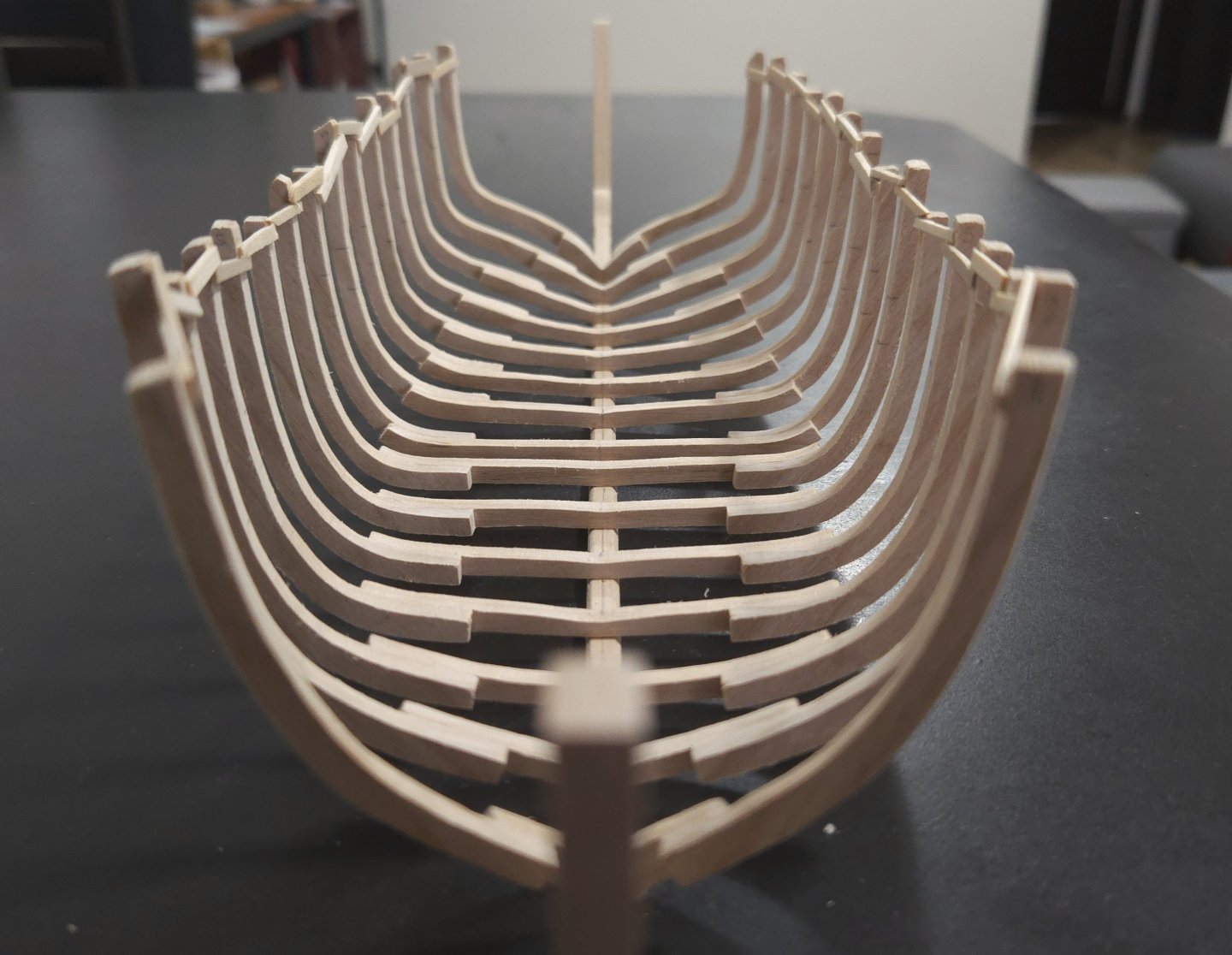

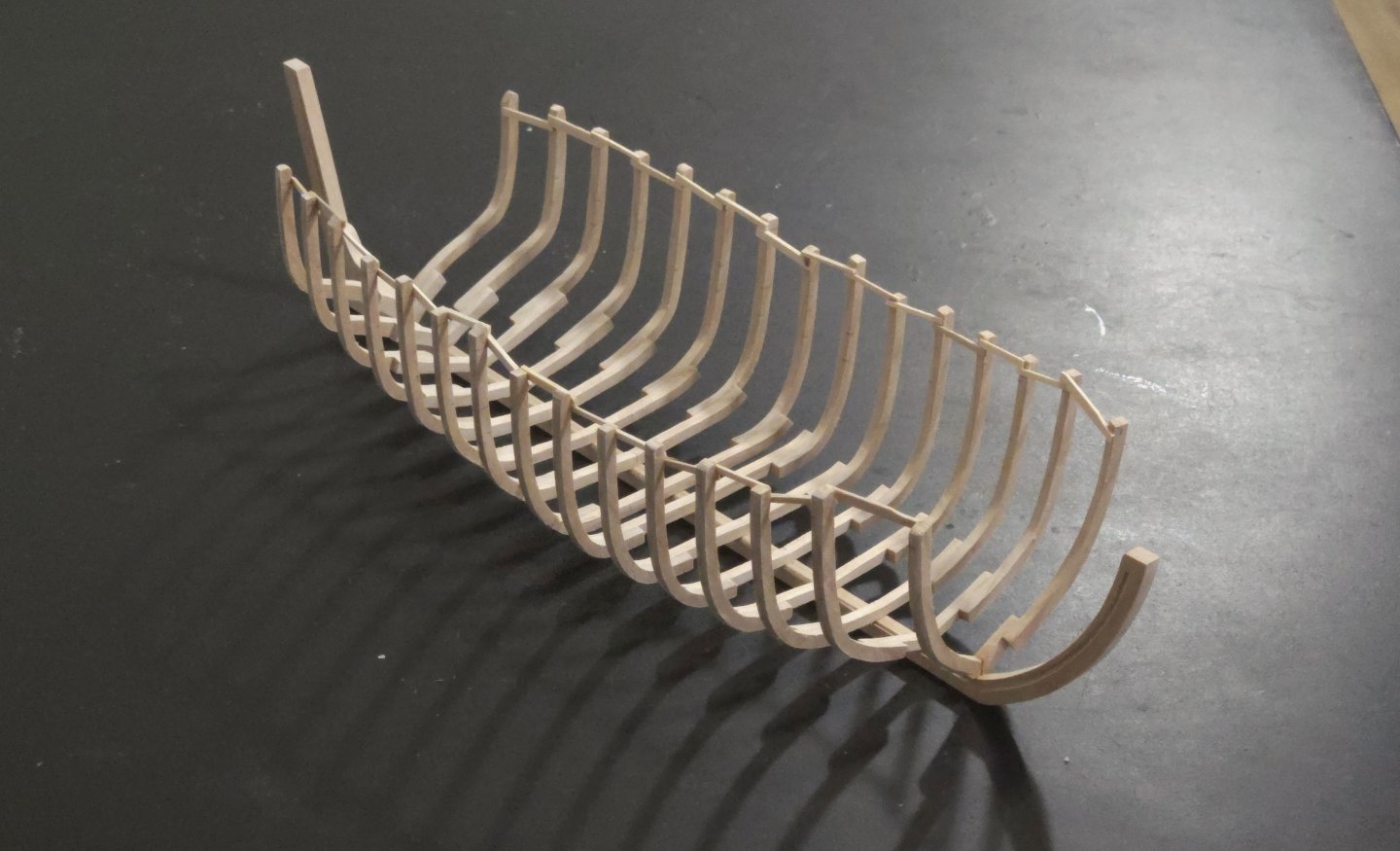

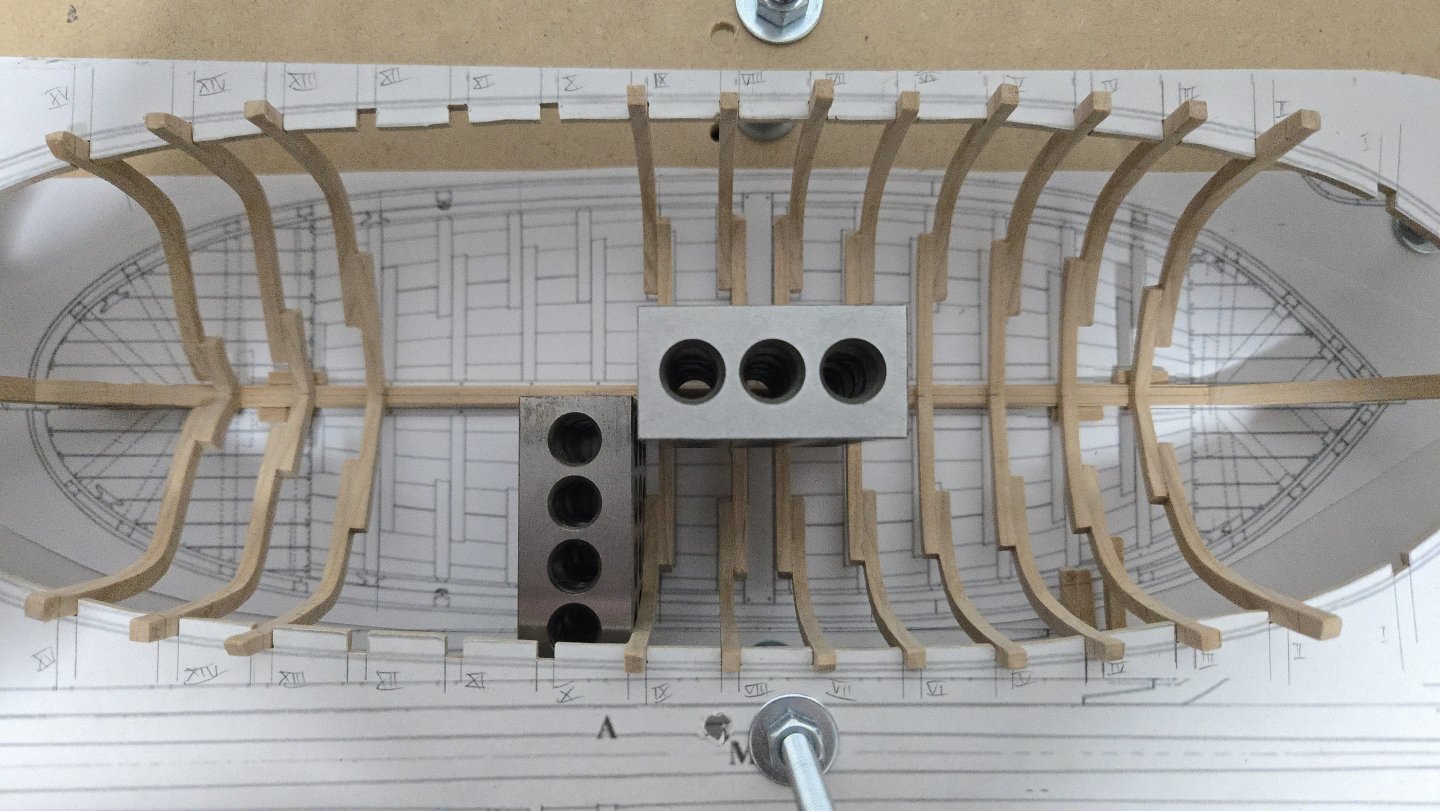

I ultimately decided to add the normal frames now and the cant frames afterward. One challenge I've had with working out how to position the cant frames has been that the frames I was positioning them in relation to weren't fixed in place, so this will allow me to more easily set up ribbands to help position the cant frames. I found the 3-2-1 blocks really useful for this. As seen below, I set up one to mark the edge of the frame, which ensured that the frame would be vertical. The other was used as a weight to clamp the frames while gluing. I used the blocks to also hold Frame 1 at the proper angle. I couldn't really clamp this one, so I'm a bit concerned that it will be fragile. In fact, the frame-keel joints are generally rather fragile, as there are no notches, just parts butted up against each other over a small area. I would like to add the two floor planks (or are they considered a keelson?) before I do much fairing, as they would significantly strengthen the structure, but I need to fair the interior, at least at the bottom of the hull, before I can add that. I've therefore added some temporary supports around the top of the frames, leaving the hull open for now (although I may add some temporary crossbeams before fairing the exterior). The frame tops aren't yet trimmed to their proper size, and the supports are made from scrap, so it's pretty ugly so far. Once they were added, my curiosity got the best of me, and I carefully removed the skeleton from the jig. The structure is fragile, but sturdy enough to be handled a bit. This model has been a keel and a pile of disconnected frames for so long, it was exciting to see and hold it as an actual 3-D structure! I can see some areas I could have been more careful with in framing--some of the joints between floors and futtocks don't form as fair of a line as I would have liked. That said, Pâris described these vessels as having roughly-made frames, so I think it will be fine enough as long as the hull itself is fair. Clearly, I have a lot of fairing in my future. I've made some pine sanding blocks with different curves to better fair the interior. My plan for the next steps is to put the hull back in the jig, fair the bottom of the hull interior, and add the two floor planks to better secure the frames. I'll then work out the cant frames, in part by running battens to make sure they're lined up properly. After that, I'll have the choice of either continuing to fair the interior and adding the stringers* to strengthen the hull, or doing the exterior first. *As is often the case, I'm not totally sure about the proper terminology here. From what I can tell, a lengthwise strip of wood running across the interior of the frames is a deck clamp if it supports a deck, or a riser if it supports thwarts, and a stringer is a more generic term for such a part. On this build, it will support tiny decks fore and aft and a crossbeam that supports the mast, but nothing else, so I'm not sure whether it would be a clamp, a riser, or a stringer.

- 139 replies

-

- ancre

- Bateau de Lanveoc

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

You're welcome! I mention it because, on my Lobster Smack build, I was surprised to see that the planking of the cockpit bulwarks turned out barely visible after I added a thin white wash. It may be more visible across the full length of a hull, though.

- 21 replies

-

- Cala Esmeralda

- Santa Eulalia

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Very nice work on a deceptively tricky little part! I forgot to weigh in earlier, but I think painting the deck will look great. You may want to experiment with some scrap, though, to see how visible the planking is through the paint, and whether it would be a good idea to lightly scribe over the joints to make them slightly more visible or not. My sense from photos is that the deck planking is very subtly visible on the actual ship.

- 21 replies

-

- Cala Esmeralda

- Santa Eulalia

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Amazing work, all of the machinery looks incredible. I knew it was small, but the photo with the dollar really brings home just how tiny this model is!

- 457 replies

-

- sternwheeler

- Hard Coal Navy

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

I think you'll have better luck getting helpful responses if you can share photos, and also the measurements of the model. Also, you mention photos of the finished kit--what company made the model?

-

There are a lot of different ways to go about this. A lot of people use legos to hold the bulkheads square, or other things like machinists' 3-2-1 blocks. A small carpenter's square is also very useful. I've also tried using large binder clips along the backbone to try to square up the bulkheads, although it's not wholly ideal. Above all, I think you just have to go slow and repeatedly check each bulkhead as you go. Good luck!

- 5 replies

-

- Bluenose

- Billing Boats

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Welcome! Those are some very impressive builds!

-

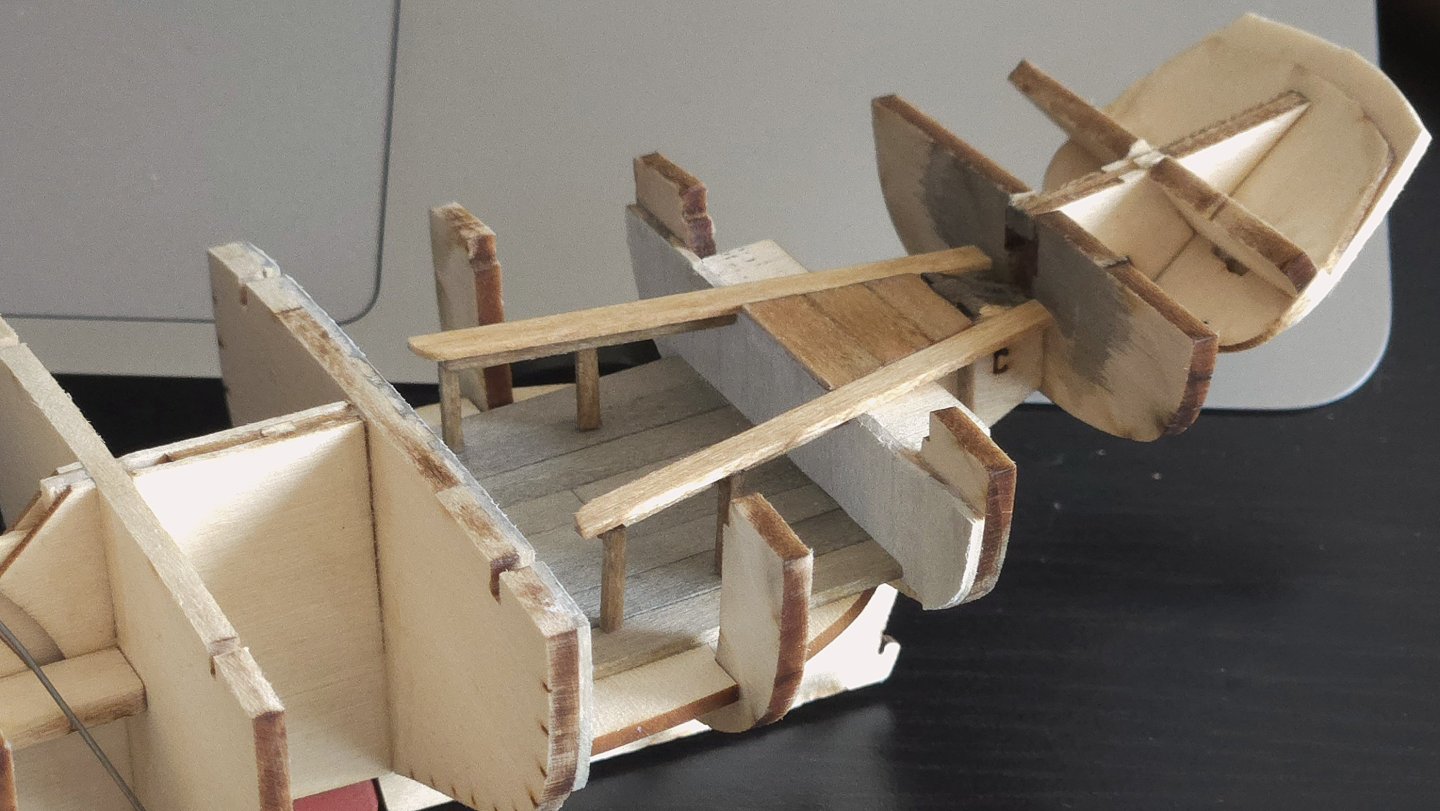

Thanks, Keith! I decided to work a bit on the side seats before planking the hull and blocking a lot of access, although I'll be gluing them in later. I took the photo below as my guide, although I'm modifying it to fit with the bulkhead aft. As you can see, the seats are supported by a framework that rests on columns at the front end and, at the back, is held up by supports that run back to the hull and are attached to a stringer and the frames. Source: https://penobscotmarinemuseum.historyit.com/items/view/digital-collection/298307/search?resultsMode=search&searchInterfaceId=1&search=eyJxIjp7InNmMTI3IjoiRnJpZW5kc2hpcCBjb2NrcGl0In0sIm9iIjoic2NvcmUiLCJvIjoiZGVzYyIsInBzIjoyNCwidiI6ImdyaWQiLCJyY2kiOjAsInNzZiI6MCwicHJlIjp0cnVlLCJpcCI6MSwicmEiOltdLCJwZyI6MCwidmlld01vZGUiOiJncmlkIiwiZmFjZXRTdGF0ZSI6ImVKeE5UanNPd2pBTXZRcnkzSUd5SURJeUZIVURNU0tHa0xqRkltMUNuQ0JWVmUrT29VVmlzWi9mVHg2aE82TkRrOGozdkI4cWJUQlZoTTZDR3FjQ3VvVndDV1BkaDV6KzZVUDBPZkFjUndsY3JqL2xxRnZreFZyM2xFaTd1UVB0S1dNY1JJTG5aM0JUYnJhZ29JcUV2ZVU3aFpYeDVoRW9nV1Q5VFNRMlBpTElJZGdpRzRGQnVuY0Z2SVJwSTFsaG9pRlE2d0tZbSs4T0VsRXBaaXlBQXFoU0hIcCtNTFJpbUtZM0ROWlJudz09In0= I won't be able to attach the stringer or supports running out to the hull until the hull is planked, but I can fabricate the front of the seats, with the columns, now so that I can make sure they're even. Everything was made from basswood. I stained the framework a darker color than the seat planks. Unfortunately, due to the fragility of the 1/16‐inch square basswood columns, I did not include the decorative elements visible in the photo above. I left the planks long at the aft end, as they will be covered by the seat back, and left the columns a hair oversized so I could carefully trim them to fit properly. And here both seat fronts are dry-fit. The seat planks need a bit more staining. For now, these will be removed so as to not interfere with finishing the floor planking after covering the hull.

-

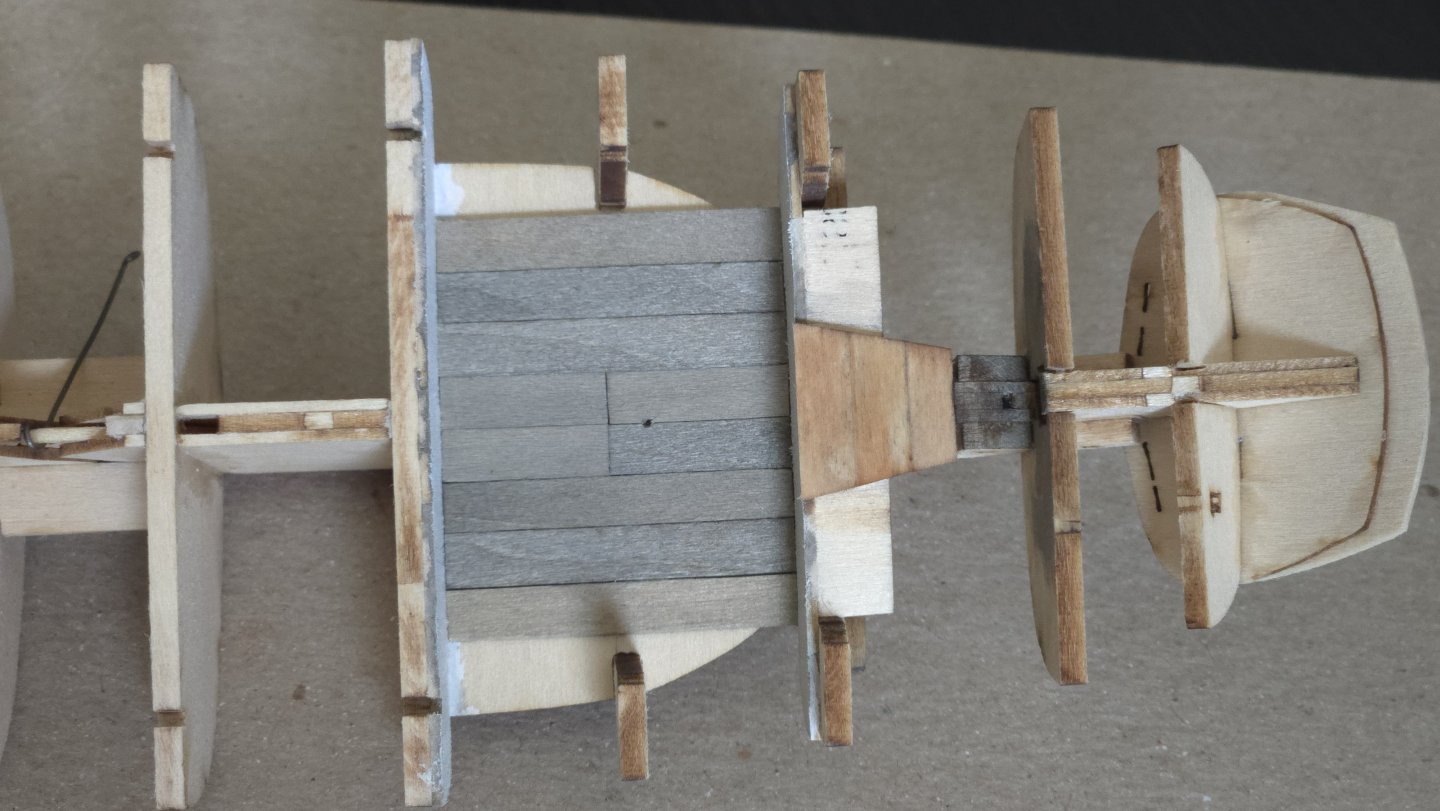

A bit more progress with the cockpit. Originally I was planning on cutting away the sides of the frame under the aft cockpit seat, hence why I only planked partway to the sides. But then I noticed that Ansel describes the Ranger as having a full bulkhead running across the hull under its aft seat. That made sense to me, so I redid the planking. I also added the central portion of the seats. The planking for the side benches, not yet added, will run back over the bulkhead all the way to the back of the seat. As can be seen, I needed to glue supports over the portions I had already scored on the bulkheads, and re-scored a new line to remove to upper portion of the bulkhead after planking the hull. Next, I wanted to get a sort of dirty, weathered whitewash on the bulkheads--like they were in need of a new coat of paint after a hard season. I began by applying a dark wash as an undercoat, followed by a white wash on top. I tried using tape to selectively strip off random portions of the white wash, but it didn't quite work as planned. I then decided to try to add at least the central portion of the cockpit floor planking, figuring it would be slightly easier before planking the hull. I drew inspiration from the photo shown in an earlier post of a Friendship Sloop cockpit, which had short central planks with a finger hole in the middle, presumably to allow the central planks to be removed for bailing. I colored the planks with a dark wash before gluing them in place. This is as far as I can plank the floor without removing a portion of the bulkhead, so the rest will have to wait until the hull is planked. I already cut planks to the right width and gave them a dark wash, though, so it won't be too difficult then. Unfortunately, my attempt to color the seat by staining and then adding a dark wash revealed some glue stains. I think I may remove the central seat and redo it.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.