-

Posts

2,384 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dr PR

-

White lettering decals..How?

Dr PR replied to wmherbert's topic in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Here is another option using rub-on letters as stencils. 1. Get some rub-on letters in the desired font and size. Color doesn't matter. 2. Paint an area with the desired letter color (white for example). Let the paint dry thoroughly. 3. Rub on the letters, placing them carefully, of course. 4. Paint over it all with the background color (black, for example). 5. Let the paint dry. 6. Use tape to remove the rub-on letters. Now you have white letters on the black background (or whatever colors you use). There is no decal film around the letters, and they are only as thick as a layer of paint. The lettering will not yellow as decals do over time. I have been using this process for many years, and other that getting the rub-on letters aligned properly it is pretty simple. -

Tiny Spar on 17th Century English Yacht

Dr PR replied to catopower's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Clare, I have seen this method of strengthening the peak of sails a number of times. I think a short spar like this that is attached to the peak of a sail is called a "club" but I am not certain. The Dutch used a very short spar like this at the peak/head of sails in the 1600s on small vessels (Sailing Ships, Bjorn Landstrom, Doubleday & Co., Garden City, New York, 1969, page 156). This later grew into the common gaff. So if it is on a sail rigged aft of a mast perhaps it should be called a gaff. If rigged before the mast as in your picture I guess it is just a "spar" or perhaps a "club." Somewhere I have a reference that shows how to make these. The sail is laced to the club/spar. The halliard attaches to the spar. I don't know if it matters how, but in your picture it looks like the halliard block is riding on a line attached to the ends of the spar. It may be securely attached to the line at its center, or just sliding along the line. I can't tell from the picture. But I see no reason when the halliard couldn't be attached directly to the center of the spar. Since this idea seems to date back many centuries it is possible it has been used in many rigs in many places. I am sure I have seen it in photos of modern vessels. What is the name and period/date of the English yacht in the photo? The Dutch were using something like this on their yachts in the 1600s and 1700s. The English copied a lot of the Dutch ideas. -

Travis, You have a decision to make. You are working on the beginner's three boat series where you will learn about wood, paints, tools and the basic practice of ship model building. Good for you. You are off to a good start. But what then? You have three choices: 1. Ship modeling just isn't your "thing." Give it up and do something else. 2. If you enjoy ship modeling pick another kit a bit more challenging than the last, a brig, schooner or fishing boat, and build it just for fun according to the supplied plans. 3. Get really deep into the hobby and research every part of your next build to make it as historically accurate as possible. It may be a kit or a scratch build, but the real fun is in the research. Most of us repeat step 2 several times before we plunge into step 3.

-

USS Constitution by mtbediz - 1:76

Dr PR replied to mtbediz's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1751 - 1800

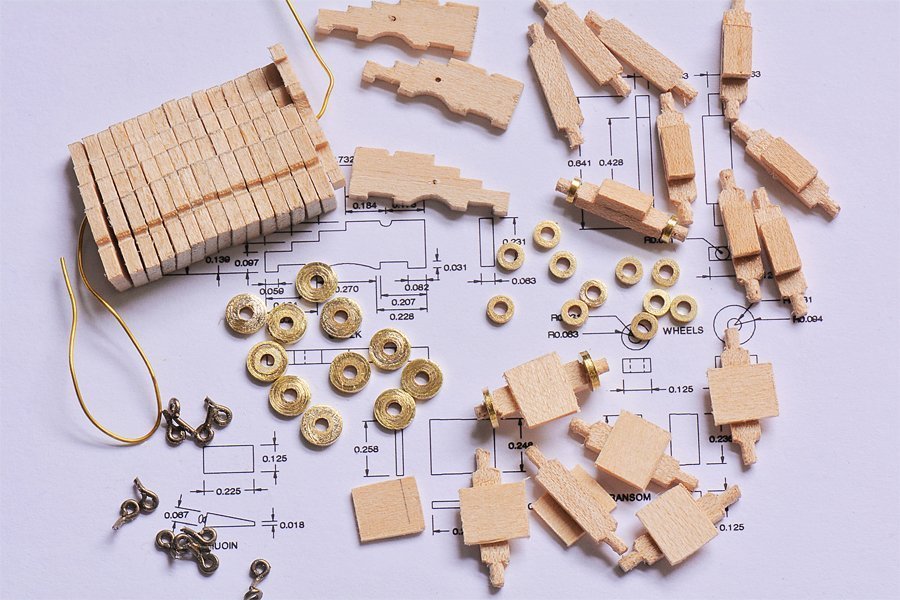

Mustafa, Nice work! The Constitution has a special place in the hearts of us US Navy folk. I too have been lusting after the Proxon MF70! There is a trick I use to simplify the making of many identical gun carriage sides (cheeks) or any other similar parts without using a table saw (I don't have a table saw!). I cut a long piece of wood to the right height and thickness of the carriage sides. Then I cut off pieces that are a bit longer than the carriage sides. I line up all of these rectangular pieces side by side and clamp them together. Then I file the ends flat and glue a strip of wood across each end. This produces a single "block" of many identical side pieces that can be milled as a single piece. Then I milled the block, cutting each feature of the carriage sides in all the pieces in a single pass, just as you did with your milling machine. After all the cuts were made I milled off the glued-on end pieces to free up all the individual carriage sides. This also cut the side pieces to the correct length. This produces carriage sides with the wood grain running the length of the pieces instead of across the parts. You can see a stack of side pieces as they came out of the mill (after the glued-on end pieces were cut away) at the upper left of the left photo, and some assembled carriages in the right photo. -

Allan, Good point! Lines couldn't belay to pins unless there were pins to belay to! Before pinrails, fife rails and such, lines were belayed to kevels (cavels), cleats, bitts, knight heads, timberheads and such. Whatever was available it seems. Over the last few hundred years of sail the ships became larger, with more masts and more sails, all with more and more complex rigging. I suspect fife rails and pin rails came into use as a necessity to deal with the ever growing number of lines that had to be belayed, and organizing them in a rational way. There is another exception to the general "rules" I mentioned above. On some vessels some lines, like halliards and bowlines, were run forward of the mast, and the higher they originated the farther forward they were belayed. Again, it was whatever worked to avoid fouling lines.

-

Brig USS Enterprise 1799 info gathering

Dr PR replied to CharlieZardoz's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Thanks. Looks like the search for the Holy Grail will have to continue! -

Nissan Fairlady 240Z by kpnuts - Tamiya - 1/12 - PLASTIC

Dr PR replied to kpnuts's topic in Completed non-ship models

This brings back memories! I saw the original "Fairladys" when I was stationed in Japan in the late '60s and early '70s. But that name was too tame for the American market where it would compete with Camaros, Trans Ams, Chargers and Mustangs, so the marketing morons coined the much more macho "240Z" name for imports into the states. After all, would James Bond be seen driving a "Fairlady?" -

Bob, I discovered this fairly cheap source of good quality wood (along with bamboo barbecue skewers) long ago. Other useful sources of supplies are paint mixer sticks, roofing gutter flashing, jewelry supplies, carpentry wedges and even bundles of fire starters! Walk through a crafts store or hardware store with an open mind and you can find all sorts of materials useful for our hobbies.

-

Allan, I am fairly new to the study of sailing ship rigging, having started on a topsail schooner about five years ago. But one thing I have discovered is that it is probable that no two ships were ever rigged the same way! So Lees (Lever, Marquardt, zu Mondfeld, Chapelle, McGregor, Peterson, Underhill, Biddlecomb, Steel ...) may show the way a particular ship was rigged, but that doesn't mean every ship was rigged that way! There is only one rule that I have discerned that applies to every ship - a line must not foul other lines, spars, masts, etc., and when possible it should be routed so it doesn't chafe against other parts. Given this rule you have to attach lines and blocks wherever necessary and find a place to belay them to clear as much of the other rigging as possible. I suspect it was the Captain, Mate or Bosun who decided how things were rigged on their ships, and that might change with time and experience. There are some general trends for belaying that I have found: 1. Lines that originate lower down in the rigging generally belay forward on pin rails, fife rails and cleats. Lines from higher points belay farther aft. 2. Lines descending from near the mast belay near the bottom of the mast (partners). Lines descending from yard arms belay along the bulwarks or deck edges. 3. An exception to 2 is that lines from very high in the rigging, whether from yard arms or from near the mast, may belay along the bulwarks or near deck edges. The prime rule is that lines must not foul other lines. They may be led through fairleads on crosstrees or the bowsprit, through thimbles/trucks on shrouds, or running blocks attached where necessary to lead them around obstacles. How all of this is accomplished depends upon the configuration of the masts, spars and rigging on the particular vessel. For example, I have found three different ways the fore course (spreader) yard braces were routed on topsail schooners, and there may well be other ways. Perhaps the most frustrating thing I have encountered is that almost every "authority" I have read that describes ship's rigging says for every line that it was "belayed below" or "on deck." Very few books show where the lines were belayed "below." I eventually figured out that this is because no two ships were rigged the same. So unless you have the original rigging and belaying plan for a particular ship you are pretty much on your own to figure it out for yourself!

-

Brig USS Enterprise 1799 info gathering

Dr PR replied to CharlieZardoz's topic in Nautical/Naval History

Has anything come of the drawing Geoffrey Footner found in the archives of the Arsenal of Venice believed to of Enterprize? Is is actually a drawing of that vessel? -

Melissa, I have a Paasch airbrush set (VL-SET) that I got 20-30 years ago. It has a VL double action airbrush - push the button down to increase/decrease the airflow and forward/back to control the amount of paint. This "double action" allows very good control of the amount of paint you apply, and you can shut off the paint and just use it as an air supply to blow dry the paint. I don't remember what I paid for it back then, but it has been worth the money for all the painting options it allows. I see it for under $80 on Amazon (less the 3 ounce bottle). It came with three needle/nozzle sets for fine (narrow), medium and heavy (wide) paint application. This is good for painting small parts or larger surfaces like hulls. It has a paint cup for small amounts of paint and two bottles (1 and 3 ounce) for larger paint jobs (but not large enough to paint your house if you are in a hurry). **** The air compressor and regulator are as important as the airbrush. Be sure you can adjust the pressure to the 20-30 psi range. An air tank on the compressor output is good because it will absorb some of the pressure pulsations from the compressor and collect moisture from the cooling compressed air. Just about anything you can find that meets these requirements will work.

-

Here is a bit of trivia for you: In 1980 I started working for a company that had the contract for automating plywood lathes from the company that owned the patent. We supplied the computers and software to peel veneer from logs. By the mid '80s nearly all of the plywood lathes in North America were operated by a small (6" x 6" x 6.5") multiprocessor computer I designed. If you used plywood in North America from 1985 through to about 2000 the veneer was probably produced by that small computer. It was a fun project! https://ao-cs.com/Projects/little computer project.html

-

Another bit about rivets as a reference to putting them on models. On the Cleveland class cruisers of WWII that I am familiar with. Below the water line rivet heads were to be "as nearly flush as possible." The leading edges of hull plates of different thicknesses were chamfered by grinding to about 45 degrees. Backing plates were inside the hull plating. Quite a bit of effort was made to reduce drag. Above the water line backing plates were outside the hull plating. Rivet heads were visible if you were standing close to them, but had very slight height above the plating and slightly conical. This was also true of the rivets on the turrets. None of the riveting would be noticeable from more than a few yards/meters distant. There is no reason to put them on models. I don't know how many decades this type of riveting goes back before the 1930s, but at some point builders began taking steps to reduce underwater drag.

-

Per and John, I call myself a frustrated perfectionist. Although my goal is always perfection I have yet to achieve it. Maybe because I think achieving perfection is impossible! But it doesn't hurt to try. My primary goal with this build was to learn about topsail schooners, and I am doing that! Almost all modeling information (spar dimensions, rope sizes, etc.) is for larger square rigged ships. I have encountered "surprises" several times, like the difference in gaff halliard size calculations for ships and schooners, or mast diameter calculations. And in the end I learn about both schooners and ships! Unfortunately, John, this model isn't historically accurate. I made mistakes when I first constructed the hull decades ago, and additional mistakes when I started up again five years ago this month. At least some of the details are probably historically accurate. But I have enjoyed the build immensely - and I am learning!

-

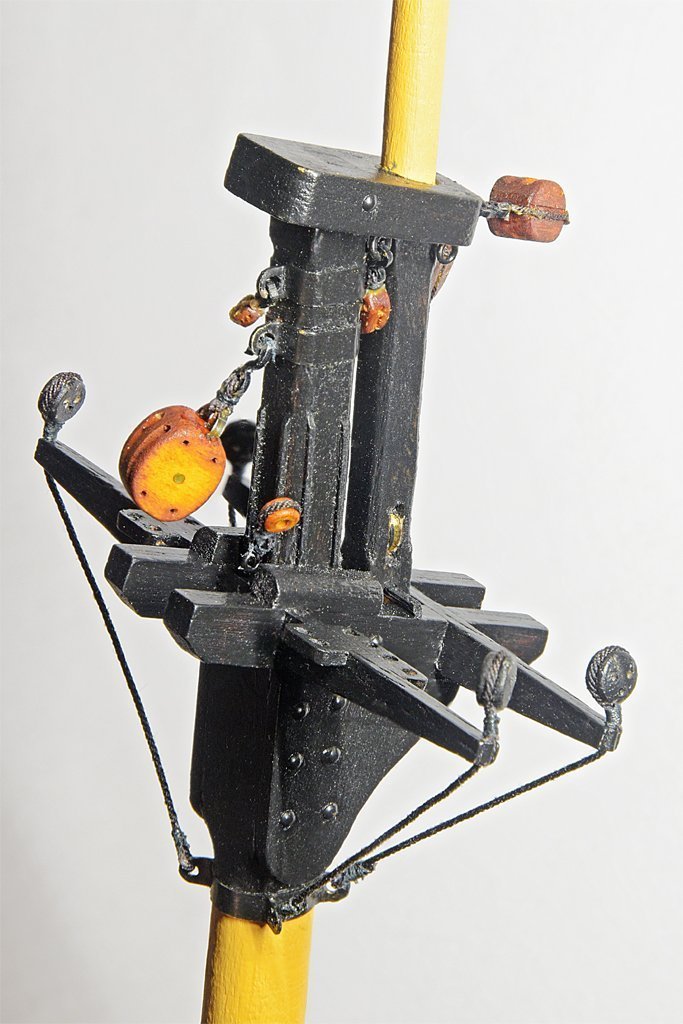

I have run into another problem with dimensions of parts for schooners versus large square rigged ships. My initial calculations for the size of the blocks for the gaff peak halliard and throat halliard was 5/16 inch (8 mm). I have calculated this using formulas from several authors and they all say the same thing. But look at this photo. The 8 mm peak halliard block hanging from the band on the mast is ridiculously large. Its height is about the same as the diameter of the mast. I have looked at a number of period models and recent kits, and none have blocks this huge! I think my calculations are just wrong! According to several sources the fore stay circumference is 1/2 the mast diameter (0.350 inch, 8.9 mm), or 0.175 inch (4.4 mm). The halliard size is 1/2 the fore stay size, or a circumference of 0.088 inch (2.2 mm) and diameter of 0.028 inch (0.7 mm). So far all sources agree. I will use 0.025 inch (0.0635 mm) rope. But the block size is supposed to be about 12.6 times the rope diameter (4 x circumference), or 5/16 inch (8 mm). The block in the photo is an 8 mm block! Lees Masting and Rigging says the height of blocks should be about 4x the rope circumference. The circumference is 0.088 inch, so the block should be 4 x 0.088 inch = 0.352 inch or (8.9 mm). This is even larger that what I have used!! To look at it another way, for a 1:48 model 0.352 x 48 = 16.9 inches. Or 5/16 inch x 48 = 15 inches. Both seem too large. These calculations are all for large square rigged ships of the line, but schooners have lighter tophamper than square riggers. Marquardt's The Global Schooner says the schooner throat halliard size is 0.4 x (not 0.5 x) the main stay circumference, or 0.175 x 0.4 = 0.07 inch (1.7 mm). This would give a block size about 0.28 inches (7.1 mm). 0.28 x 48 = 13.44 inches. This is a lot closer to the 14 inch blocks listed in Marquardt's tables for many American schooners' peak and throat halliards. 14/48 = 0.29 inch (7.4 mm). I think I will use 7 mm blocks for the gaff halliards. I have ordered some 7 mm single and double blocks. I'll have to stain them to match the other blocks, and then I can get on with rigging the gaffs.

-

Beautiful model! I have liked the lines of this ship ever since I saw drawings of it in Chapelle's The Baltimore Clipper.

- 103 replies

-

- Grecian

- baltimore clipper

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

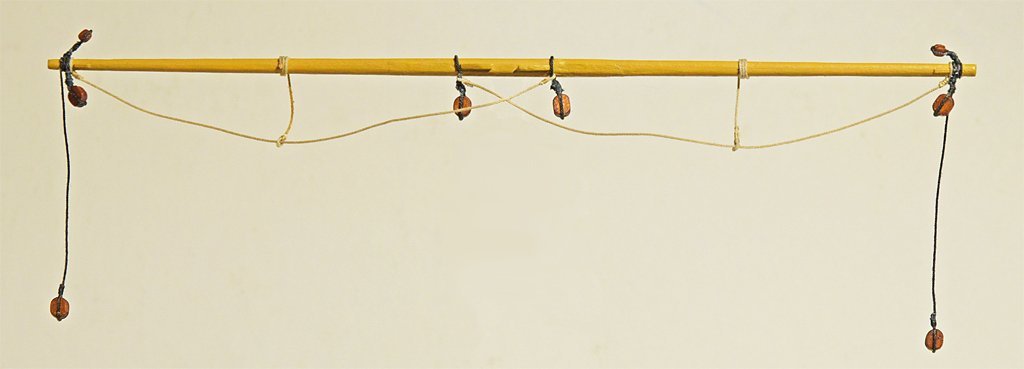

A little progress. I have rigged the yards for the fore mast. Fore course yard. Some topsail schooners carry a simpler spreader yard for the topsail, but I have rigged this yard so it can carry the large square fore course sail. The upper blocks on the yardarms are for the fore course yard lifts and the topsail sheets. The brace pendants hang from the yardarms. The larger blocks at the center inside the sling cleats are for the topsail sheets. At the outboard ends of the sling cleats are the fore course clewline blocks. Farther out are blocks for fore course buntlines. The yard sling and trusses will be at the center between the sling cleats. Normally the vessel would have raised just the fore staysail. But in good wind from astern the fore course could be raised. These two sails occupy some of the the same space forward of the fore mast so they wouldn't have been raised at the same time. The yard also has irons for studding sails. Fore topsail yard. The lower blocks on yardarms are for studding sail halliards. The upper blocks are for the topsail yard lifts, and the blocks near the center of the yard are for the topsail clewlines. The brace pendants hang from the yardarms. Now I need to "train" the footropes (horses) to hang naturally with some shellac and weights. Some of this rigging would have been very difficult if the yard was mounted on the mast, and with the mast mounted on the hull.

-

Who uses nails?

Dr PR replied to bigcreekdad's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

BCDad, Back in 1969 I built my first ship model kit, the Santa Maria by Billings Boats (I think). Before that I had built two scratch builds (a schooner and a Chris Craft motor yacht) before I knew there were such things as wooden ship model kits (or could afford one). The kit had tiny steel finishing nails, the instructions said to use them, and I did. They were used to hold the hull planks in place on the bulkheads. I didn't like the looks of the metal heads so I countersunk the nails. Then I mixed a paste of wood dust and glue and filled in over the nail heads. It didn't work all that well. That was the only time I used nails for planking the hull. In all subsequent builds I glued the planks in place with wood model cement (like the Duco nitrocellulose in acetone glue). I used rubber bands and a bit of ingenuity to hold the planks in place until the glue dried (it sets in 20-30 seconds and hardens fully over night). I still use small brass nails like Barkeater does. -

drilling hole through wire

Dr PR replied to BETAQDAVE's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

Dave, I hope you get a good answer! I have tried 3D printing hand rails at 1:96 scale and they are so fragile that it seems that breathing heavily over then will break them! I need to work with 1.5 ", 1.25" and 1" outside diameter pipe railings. At 1:96 that is 0.016" (0.4 mm), 0.013" (0.33 mm) and 0.010" ((0.26 mm) brass wire. Drilling a 0.013" hole in0.016" wire will require a milling machine with very little runout, and a very accurate table positioning setup (and a tremendous amount of patience). I think Sherline makes a machine that might work. -

I have one of those two-arm gadgets with the magnifier. The magnifier is almost useless! It actually gets in the way of seeing things. Get a magnifying visor! The other thing to remember is that these things have CHEAP ball adjustments. They wear out quickly and cause problems setting the desired angles. Still, mine must be 20+ years old and I am still using it, although it can be quite annoying to work with. The screw clamps to hold the alligator clips crush the thin metal tubes of the alligators further adding to the frustration when trying to reposition them. I got my money's worth out of it, but there must be something better.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.