-

Posts

7,989 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Louie da fly

-

And painted black to represent waterproofing with pitch. It's all a bit monotone now - I'm thinking of perhaps doing a bit of weathering down the track to add a bit of interest. I haven't weathered a model before, so I'll have to do some research before I start. Steven

- 508 replies

-

A very interesting project. It's very different from the kits we get nowadays but I think you could make a very worthwhile model from it. Is it to be planked, or is that the finished hull configuration? Though they're not built the same way, I'd recommend you check out the other Viking model build logs in this section to pick up some ideas. And ask questions if there's anything you don't understand. They're a very helpful bunch here on MSW. Steven

-

Yes it was, rather. They were way cool. But I still have the warm fuzzy feeling of having made them successfully, plus the satisfaction of making something more appropriate - and making it just as successfully, and the evidence that my skills have improved to such a degree that I can take something like that on with the confidence that I'd get it right.

- 508 replies

-

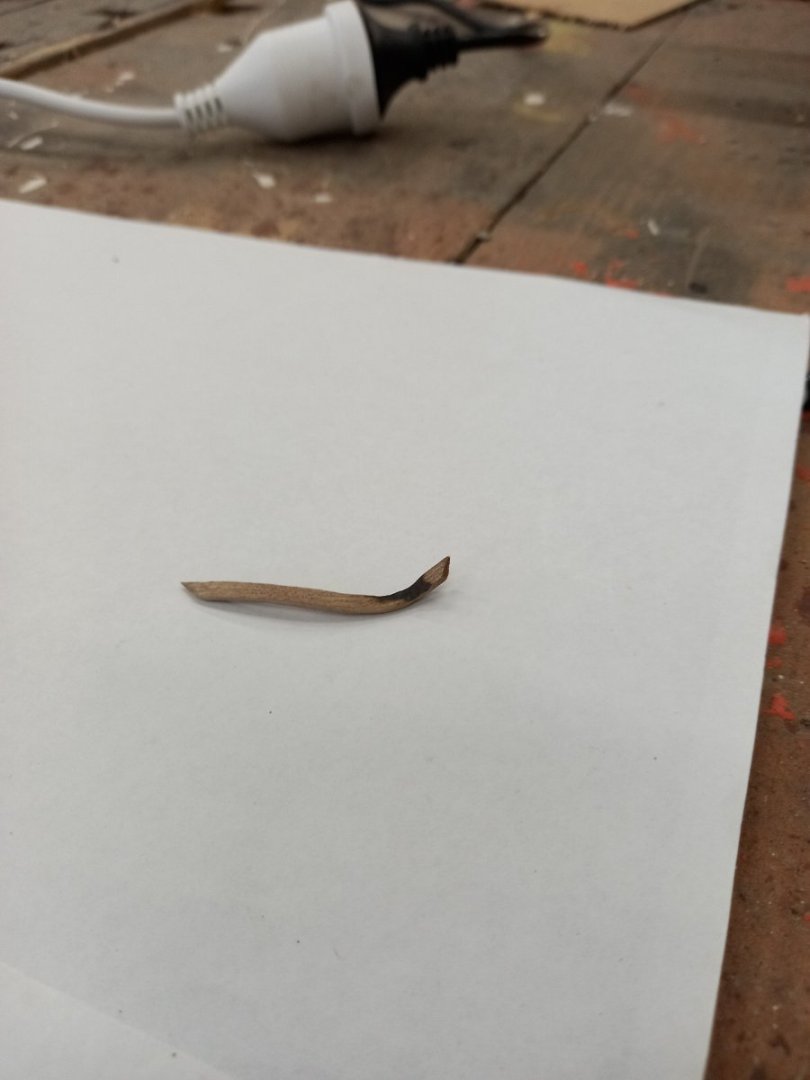

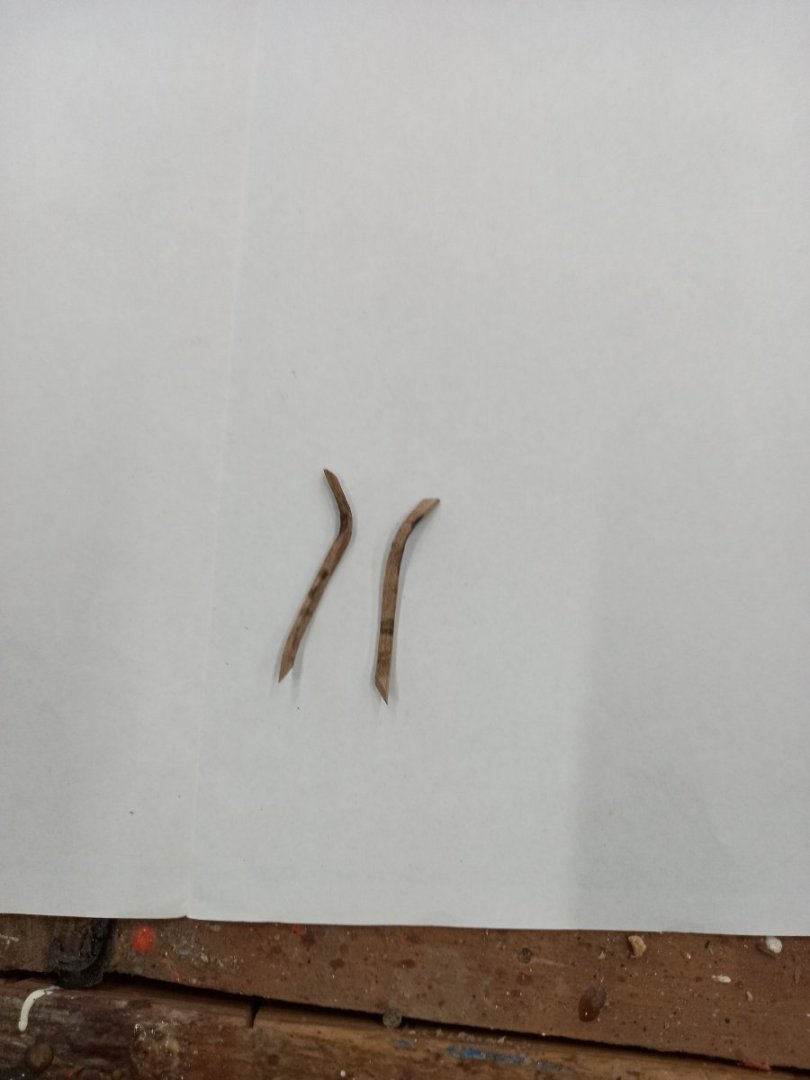

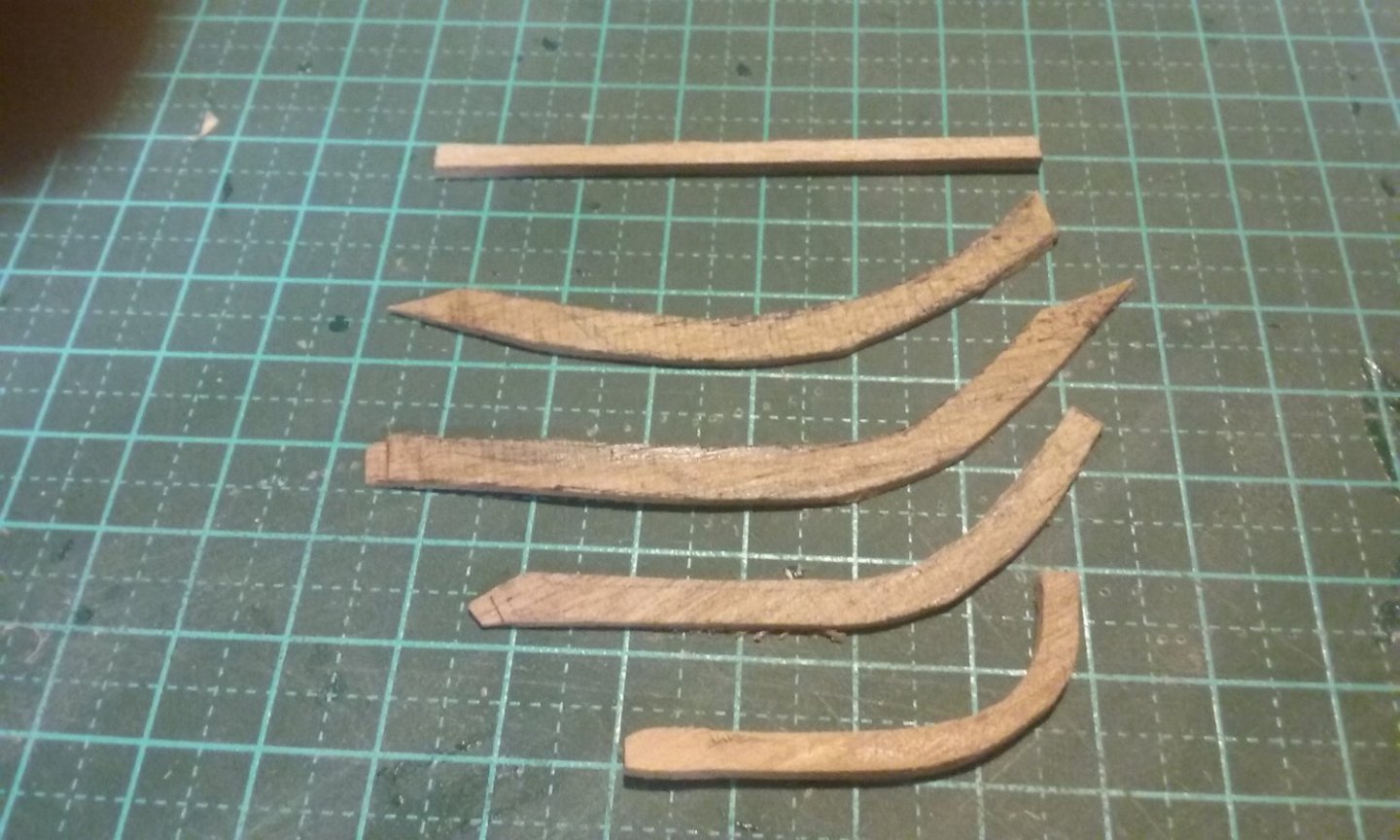

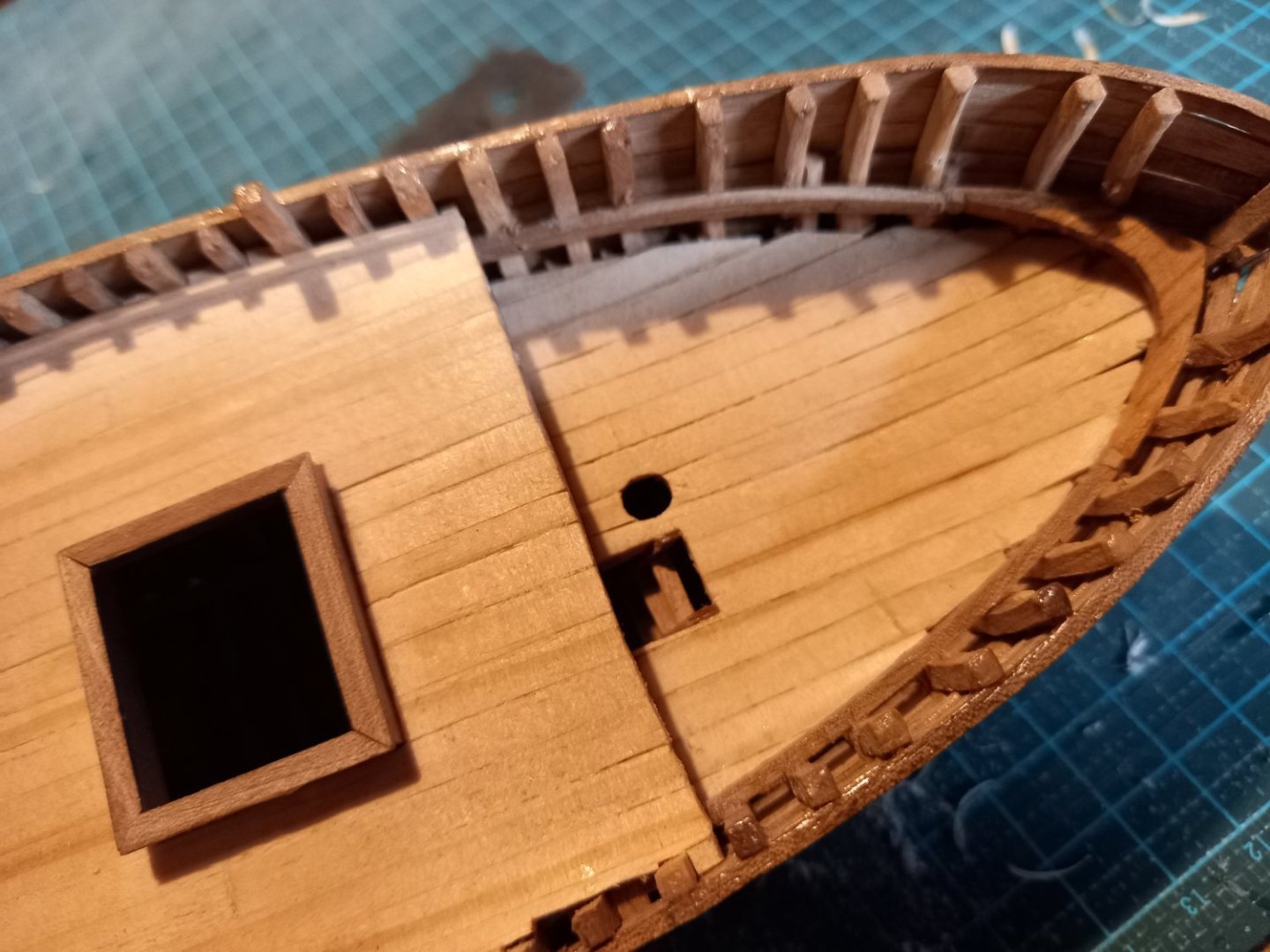

Thanks, Pat. I'm pretty chuffed with how they came out, but . . . see below. Dick, I haven't seen hawse holes in any representations earlier than the 14th century. They may just not have been invented yet. But certainly the bitt in that opening would probably be doing the same job, even if not quite so efficiently. I agree about rabbeting the joints. Much better. And though the joint was probably nailed, my idea was to fix each join with a treenail. Regarding the possibility of an anti-splash cover, well, could be. But I'll go with the way it's presented in the mosaic. I'm doing enough speculation as it is without adding more. Now for the bad news - after a period of existential angst, soul-searching and questioning the meaning of existence I came to the conclusion that those braces just didn't look right. I can't see what purpose those exaggeratedly complex curves would serve, why any shipwright in his right mind would go to all the trouble of making them and why any skipper in his right mind would ask for them. Yes, they are a possible interpretation of the mosaic, but not a likely one. I think Occam's razor - the idea that the simplest solution to a problem is probably the correct one - applies here. After some discussions with and suggestions from Woodrat (thanks, mate!) I've re-considered the braces and made them simpler. Still a 3-dimensional curve, but more logical. But first I revisited the mosaic and decided the stempost was much more curved, and wider, than the original picture shows. So I decided to trim it down to be closer to the one in the picture. Note the pencil line in the photo above. Even that wasn't quite right, so I didn't follow it exactly. Then I put in the rabbets in the gunwales to take the braces. And corresponding rabbets in the top of the stempost to take the other end of the braces. (I later changed the angle of the rabbets so everything fitted as smoothly as possible - a bit of trial and error involved in getting it quite right.) Here are the new braces. Much simpler, and they carry the curve of the gunwale up smoothly to the stempost. A tiny bit of tidying to do, but I'm much happier with this version. Steven

- 508 replies

-

Beautiful work, John. I bet a lot of your talking to the public is because they ask questions about the model. She's a real attention-getter. I find that a ship at the framing stage seems to get more attention than one that's been planked. People get fascinated by the sheer number of timbers needed beneath that outer skin. Steven

-

So here's the "bow brace" (see my previous post). Very complex 3-dimensional curve, bent using soaking in water plus my trusty soldering iron. A bit of charring, but as it's going to be painted black it really doesn't matter. I'm actually very happy with this - I've come a long way in heat bending since my first attempts on the dromon model about 7 years ago. The two sides are virtually identical mirror images of each other, and look a lot like the original mosaic. I have no idea if this is really what that thing looked like, but it seems to work for me. And here's the windlass with holes cut and ready to install. Steven

- 508 replies

-

Thank you, Glen. Yes, Louie's been around since the early 60's when he was in black and white on TV (and pretty primitive). He's got a place in Australian folklore and we're actually rather fond of him because of his rebellious attitude - he's what we in Oz call a larrikin ("Larrikin is an Australian English term meaning "a mischievous young person, an uncultivated, rowdy but good hearted person", or "a person who acts with apparent disregard for social or political conventions") which fits very well with the Australian psyche. But it's "rubbish tip" (i.e. garbage dump), not "rubbish tin" - a whole bigger area of rubbish to come from and much more shudder-inducing - which is what the advertisers had in mind . . . Steven

- 174 replies

-

- Waa Kaulua

- bottle

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

That's very impressive, Glen. She's really taking shape. I wish you the best of fortune in inserting her in the bottle without mishap. (BTW, I used weeds I found growing across the road from my home in one of my own models, as 'padding' or perhaps 'underlay', for the cargo in the hold (as it had been found in the remains of a 15th century cog). Your deckhouse looks very good. Steven

- 174 replies

-

- Waa Kaulua

- bottle

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

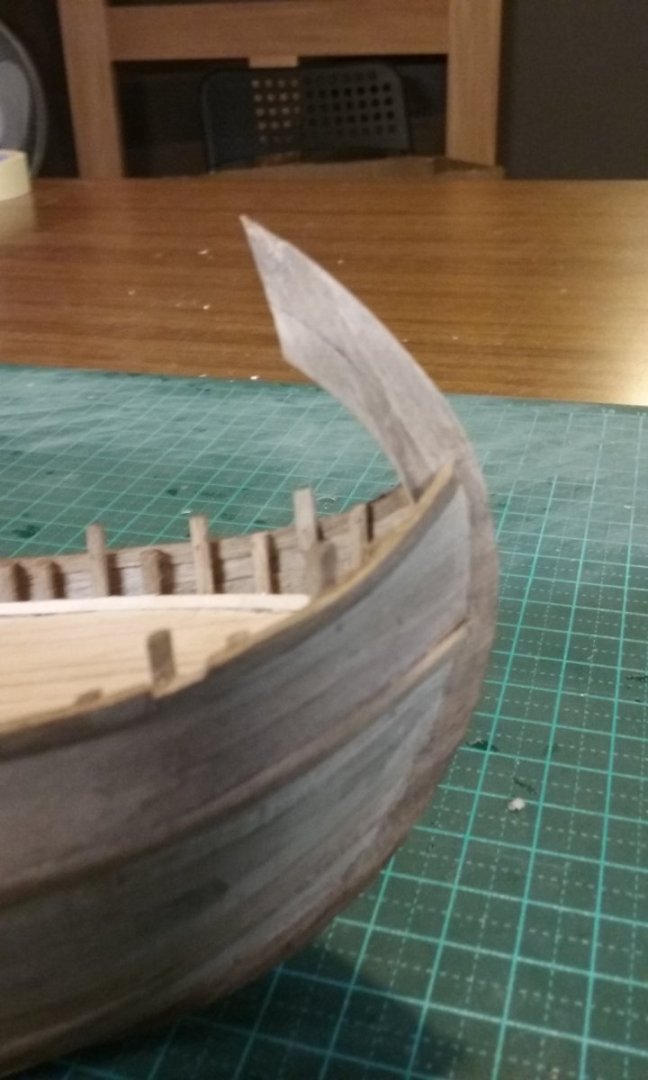

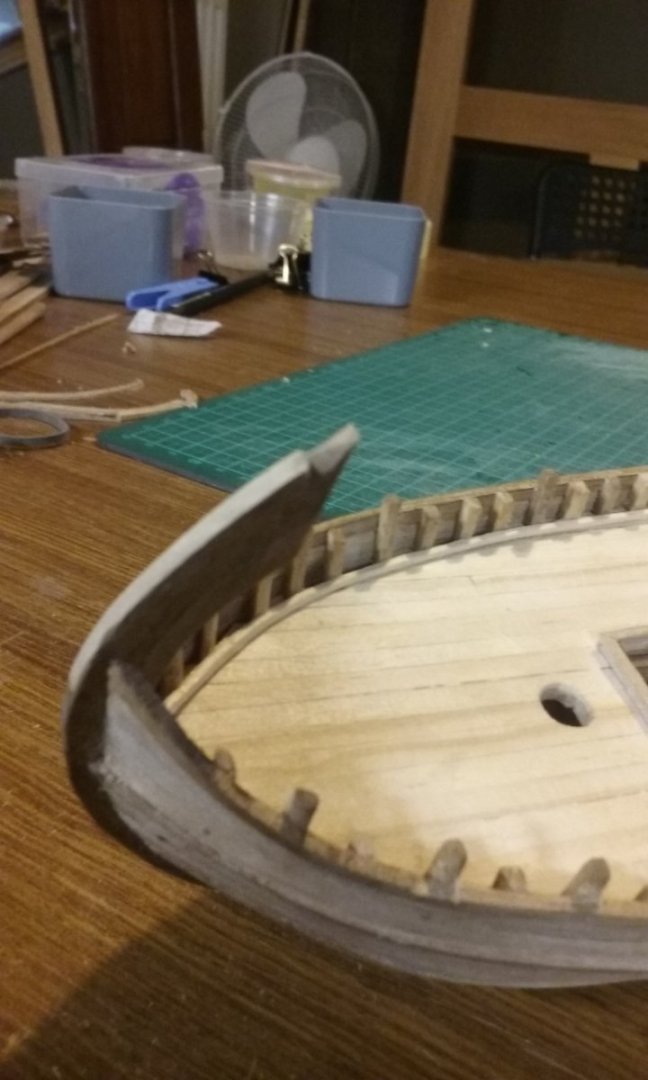

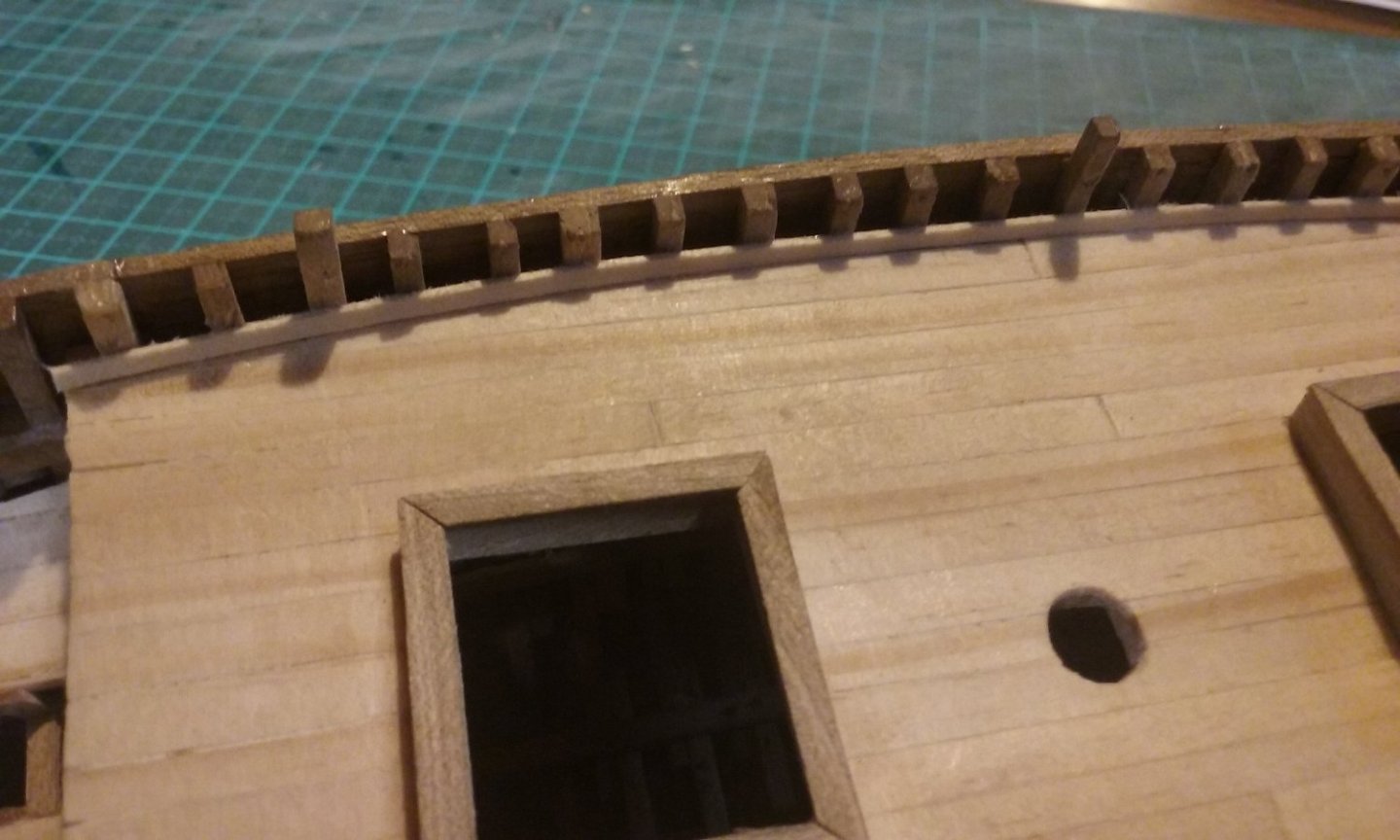

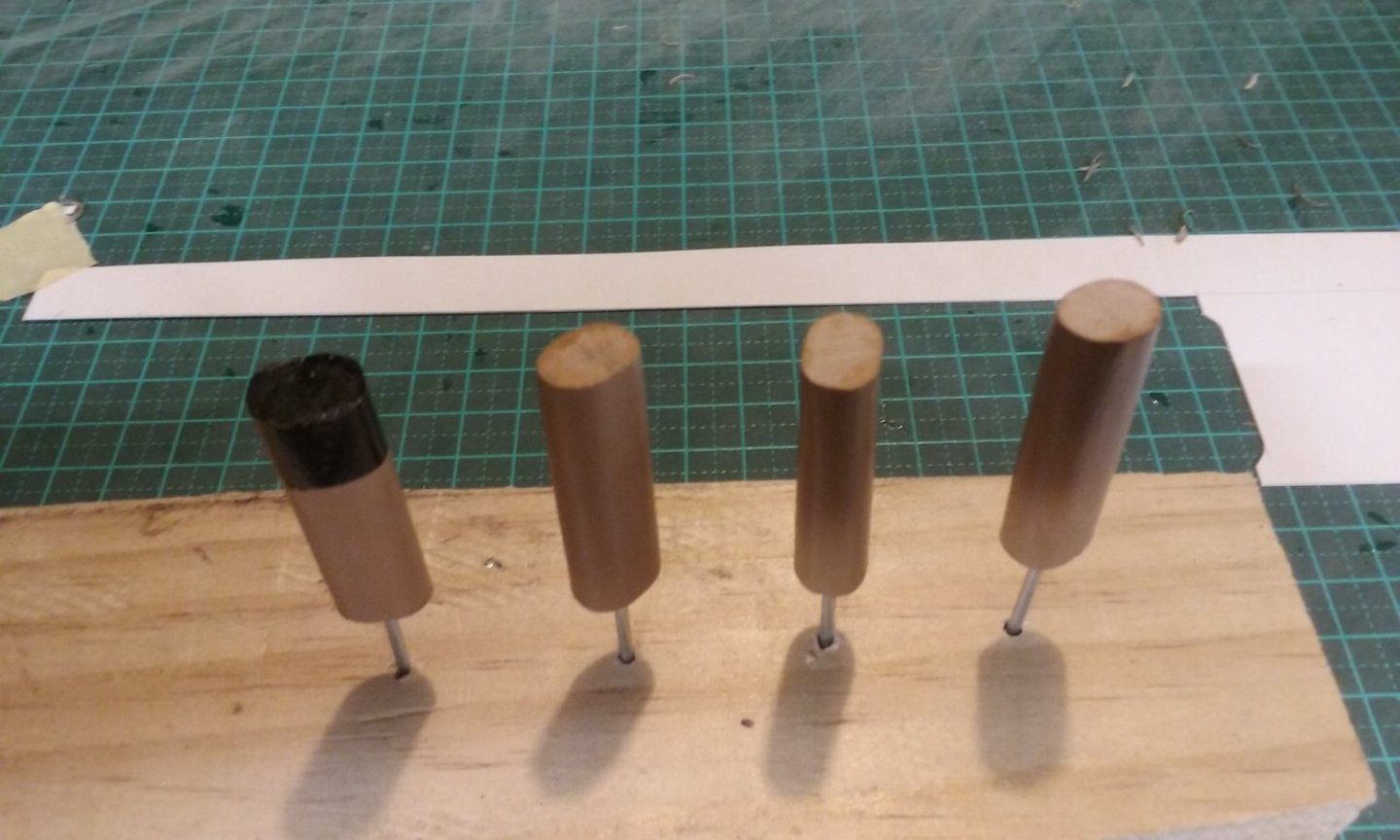

Hull sanded, gaps filled. She's looking very smooth and nice. I've been working on the curved 'brace'(?) at the stempost, as shown on this mosaic. Once that's on I can paint the hull (black, to imitate pitch). This thing presumably curves in three dimensions. My idea was to make 2-dimensional curve on a flat piece of wood following the shape in the mosaic, and curve in the 3rd dimension by heating and bending. Here is the evolution of my prototype - trial and error. I made two pieces, one for each side of the ship, glued together so they would be identical, and then separated. But I got a surprise - every time I tried a prototype out against the hull I discovered I had too much curve - until I realised this thing must have been made from a straight piece of wood and the curve developed from bending it. Waterways added. I'm thinking of adding scuppers. I have some very small diameter brass pipe which would probably do the job. I've been considering fitting out the owners' cabin below the poop deck with furniture - table, hanging cots, storage chest. Trouble is, unless you look directly down the stairwell from the poop deck you can't see anything anyway. That staircase down from the cabin is to the bilge or orlop. It's very nice, but it won't be visible when the poop deck is in place, so it'd be a bit pointless to add anything else - except out of masochism. And I've been working on the windlass. That's all for now. Steven

- 508 replies

-

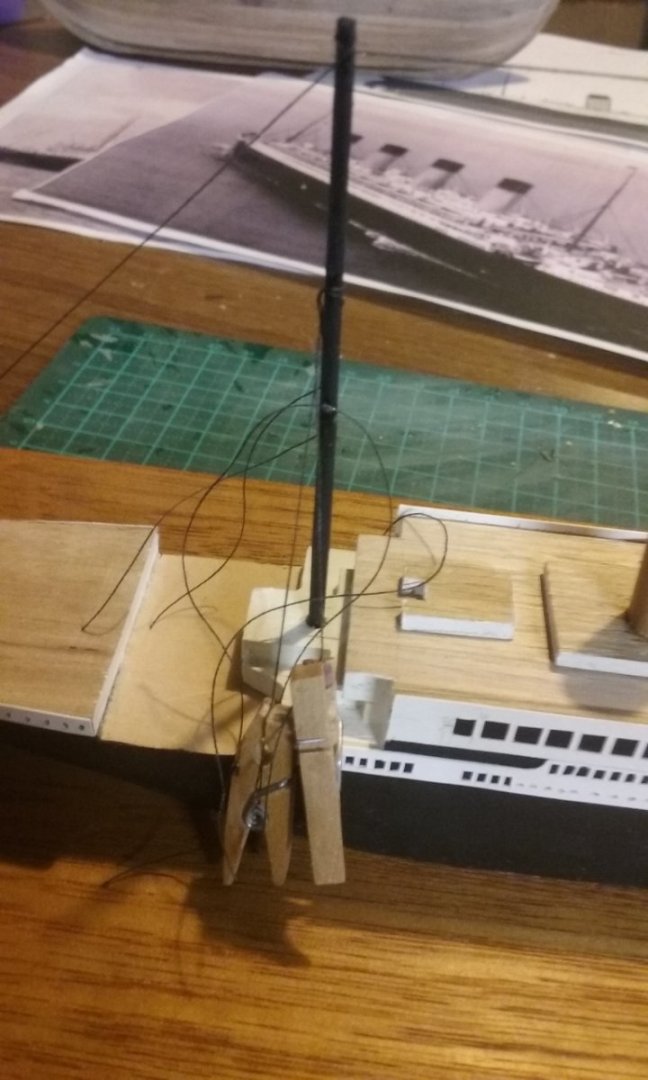

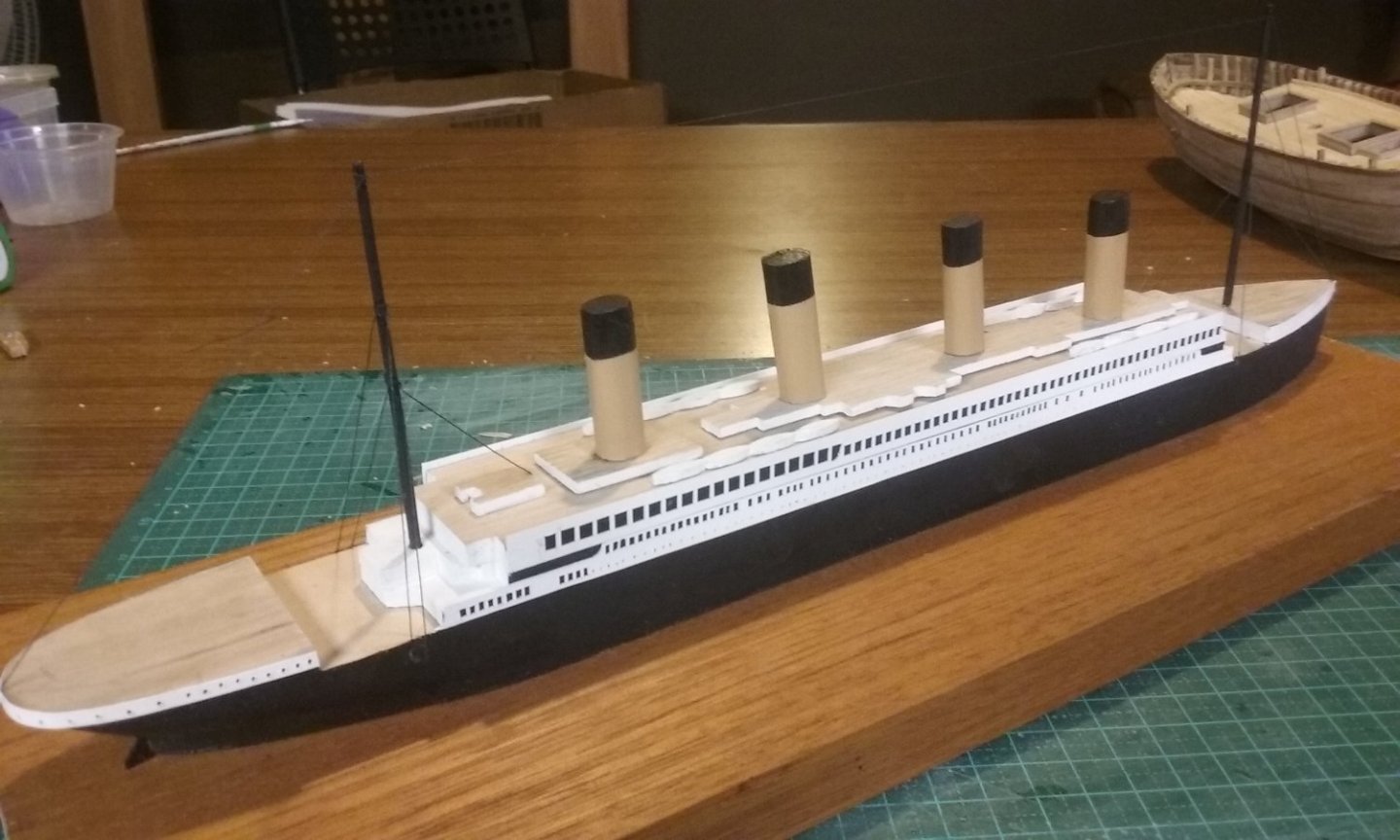

Thanks everybody for the likes and comments (and 'Wows!') Guy wires added - and she's done - finished - complete. Steven

-

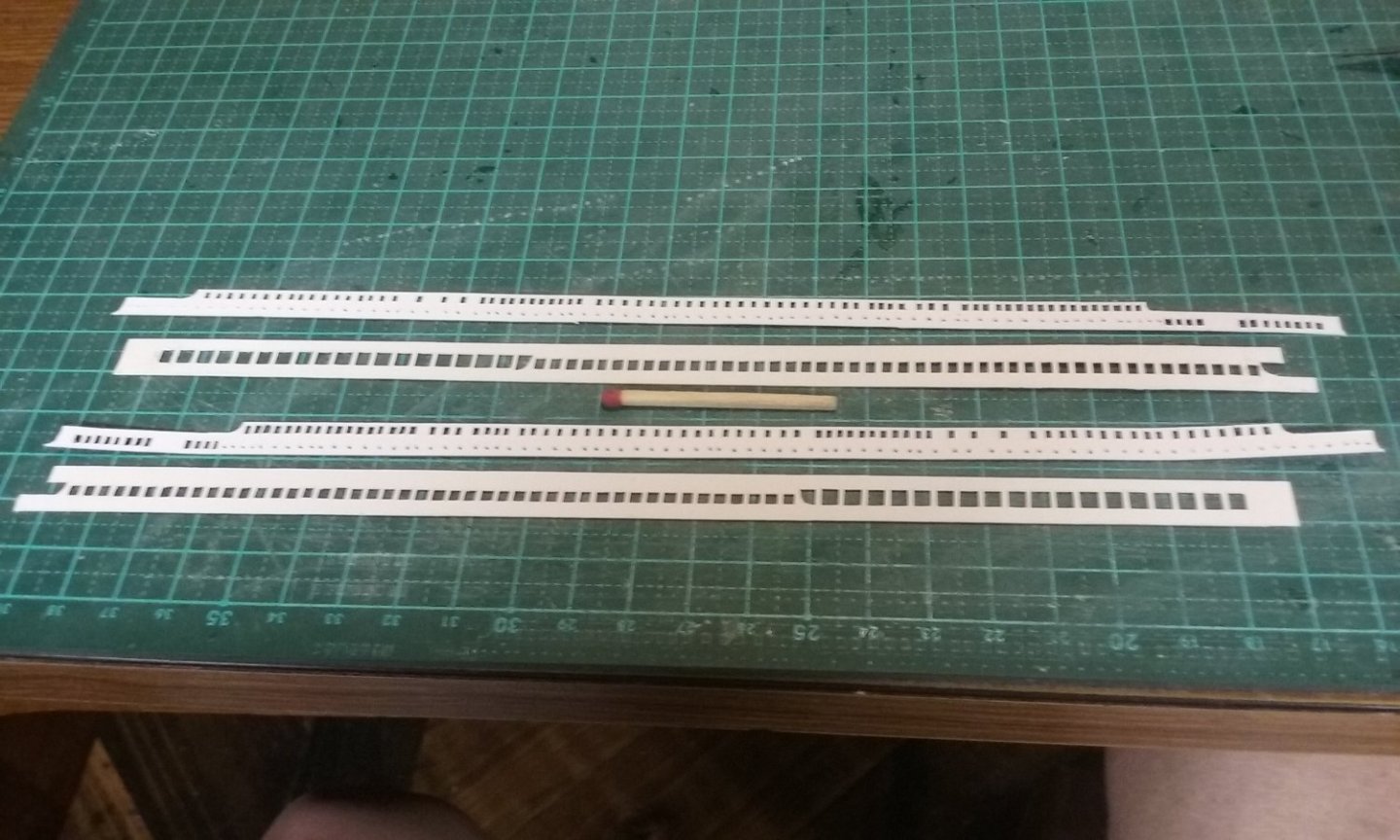

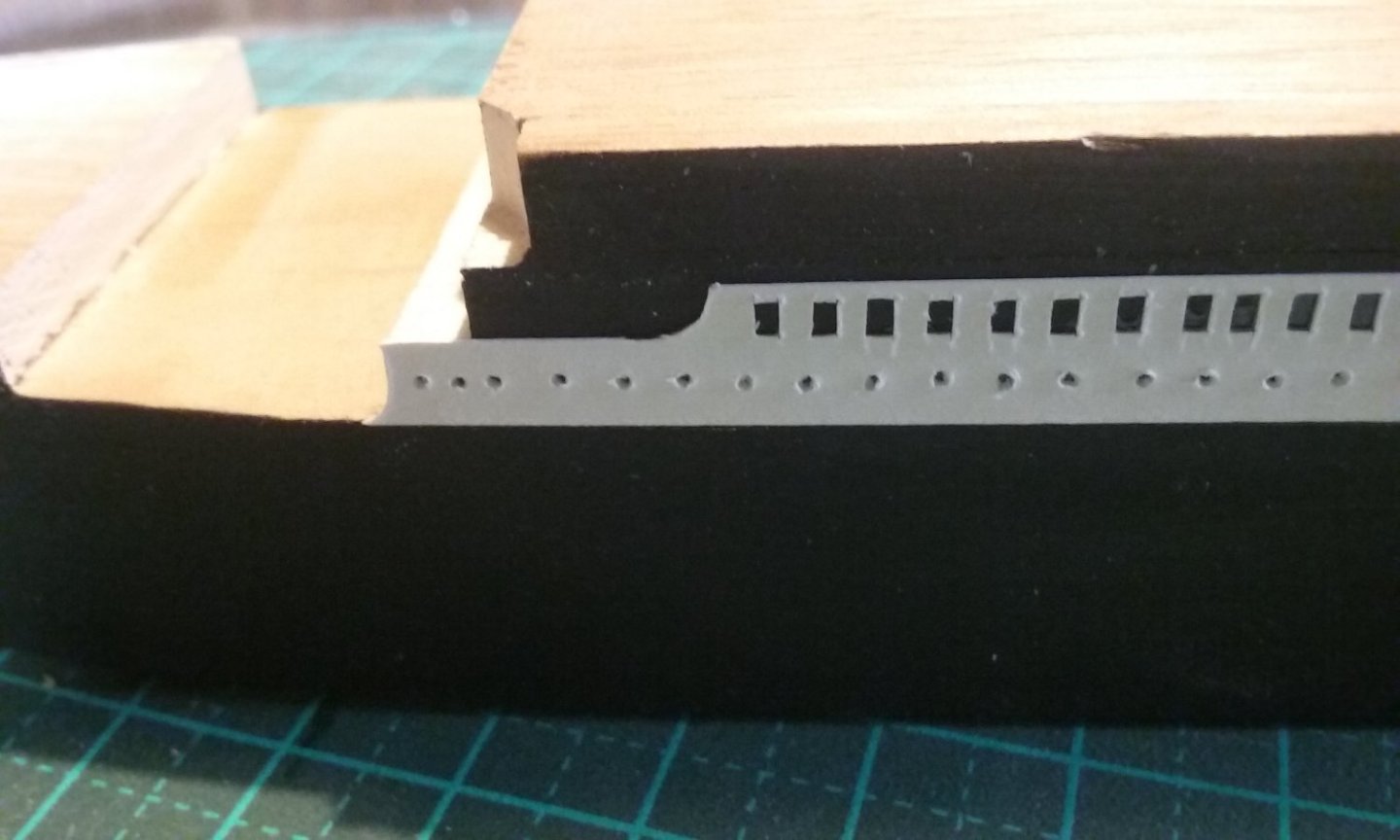

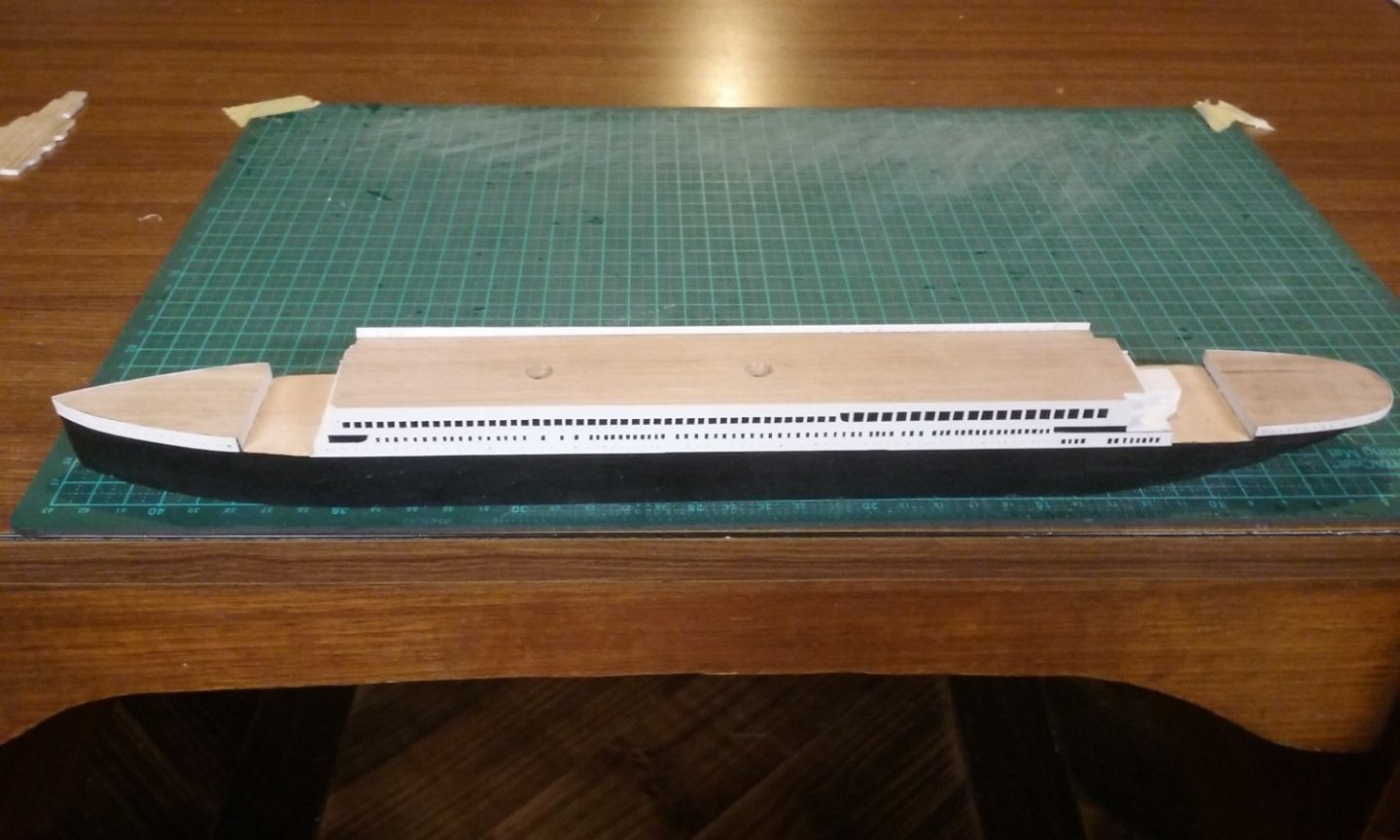

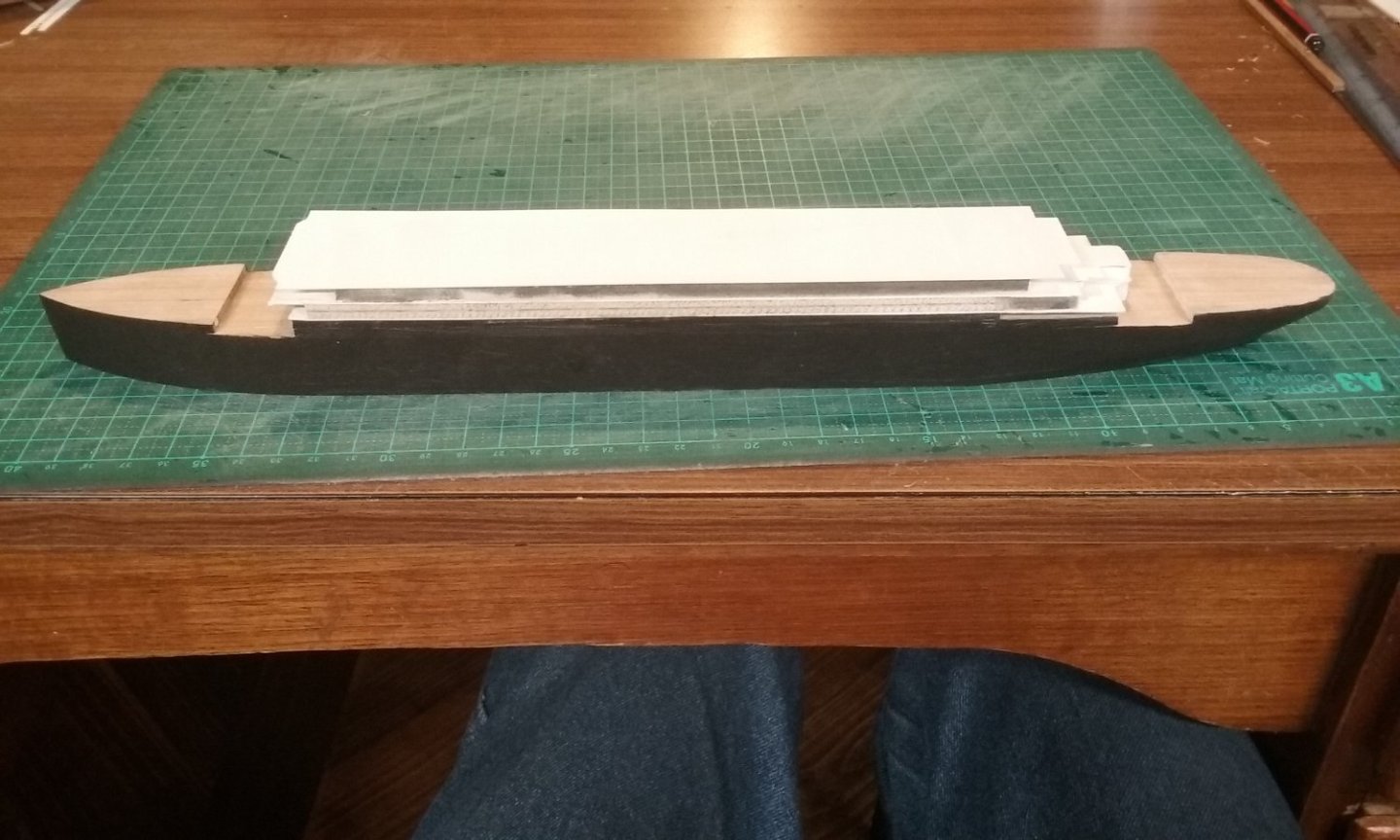

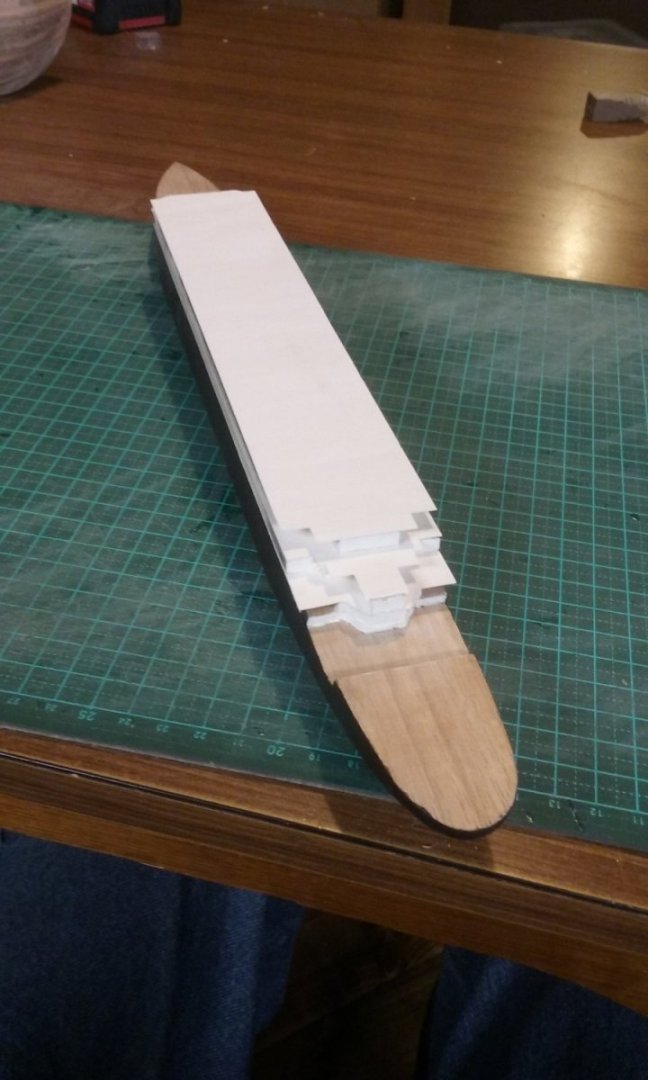

Well, now that it's (almost) finished I'm feeling rather better about the Titanic. I made strips out of card and cut the openings, portholes etc along the bulwarks and promenade decks into them. Not perfect, but hey, they're pretty small . . . Started gluing the strips along the sides: Actually starting to look quite good. Now for the superstructure for the boat deck, the funnels and masts. Tilted at 5 degrees from the vertical - fortunately my drill press has a swivelling bed. Just need to add some guy wires for the masts and she's done. Oh, and wax the raw edges of the base so it doesn't look so freshly cut. Turned out rather better than I'd feared. I think the client (and his girlfriend) will be happy with it. Steven

-

Welcome, Deyson. Looks like you started out the hard way, but you've struggled through, made a second model more suitable to starting out, and you're off and running! Don't forget to start a build log for your San Juan - go to the section marked Build Logs for ship Model Kits and then to Kit Build Logs for subjects built from 1751-1800 and follow the instructions at Before you post your build log please read this - Starting and naming your build log A build log is a great way to get help and advice, ask questions from our helpful and knowledgeable members, and of course show off your model's progress. And have fun with it! Steven

-

Looking good, mate. I seem to recall reading many years ago that shallow bodies of water have nastier storms because there's no deeper water to modify the effect of the wind - i.e. the effect of the wind goes all the way down and stirs up all the water instead of just the top layer. Something like that, anyhow. Steven

- 134 replies

-

- sea of galilee boat

- SE Miller

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

I just looked up how deep the Sea of Galilee is - apparently it's 43 metres (200 feet). Not all that deep, which as I understand it means that when it's affected by strong winds it really cuts up rough. Here's a quote I found: "The Sea of Galilee lies 680 feet below sea level. It is bounded by hills, especially on the east side where they reach 2000 feet high. These heights are a source of cool, dry air. In contrast, directly around the sea, the climate is semi-tropical with warm, moist air. The large difference in height between surrounding land and the sea causes large temperature and pressure changes. This results in strong winds dropping to the sea, funneling through the hills. The Sea of Galilee is small, and these winds may descend directly to the center of the lake with violent results. When the contrasting air masses meet, a storm can arise quickly and without warning. Small boats caught out on the sea are in immediate danger. The Sea of Galilee is relatively shallow, just 200 feet at its greatest depth. A shallow lake is “whipped up” by wind more rapidly than deep water, where energy is more readily absorbed. Lake Erie [in the United States] provides somewhat similar to the Sea of Galilee. Erie is more than a hundred times larger, but it has the same 200 feet maximum depth, the shallowest of the Great Lakes. Lake Erie is especially well known as the stormy, moody member of the Great Lake system. It is easily stirred up by west winds to produce violent waves and even the largest fishing boats are put at risk." Another site says the waves can get up to 10 feet high. So there's nothing wrong with yours . . . Steven

- 134 replies

-

- sea of galilee boat

- SE Miller

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

Still waffling around on this build. Not the way I usually work - normally I'd spend a lot of time researching and getting everything worked out before I started building, but with a deadline - and over-confidence - how hard could it be? (famous last words) I rushed in before I had everything sorted out and made even more mistakes than usual, which is why I've ended up with two versions, neither of which I'm terribly happy with. So - here's version two, with card for the decks so the promenade decks can be seen through the "side walls". Painted and with filler to hide some problems - with a fault in the timber and with the shape of the stern. Funnels made and painted. Card decks At which point I got hold of another, better side view of the ship which I blew up to 1:1 with the model and discovered I'd added a top deck which didn't exist. Plus the card was very fragile and bent when I looked at it. I've gone back to version 1, and I'm afraid the client will have to be happy with what he gets - I doubt that anyway he and his girlfriend will see the inaccuracies it took me all this time to notice. (BTW those things at the bottom of the pic are the lifeboats). I think it won't be long before it's all complete. I don't think in future I'm going to accept commissions for ships I'm completely unfamiliar with, and certainly not with a built-in deadline. Steven

-

That's quite a wave she's going through. I wouldn't want to have to walk on that! Steven

- 134 replies

-

- sea of galilee boat

- SE Miller

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

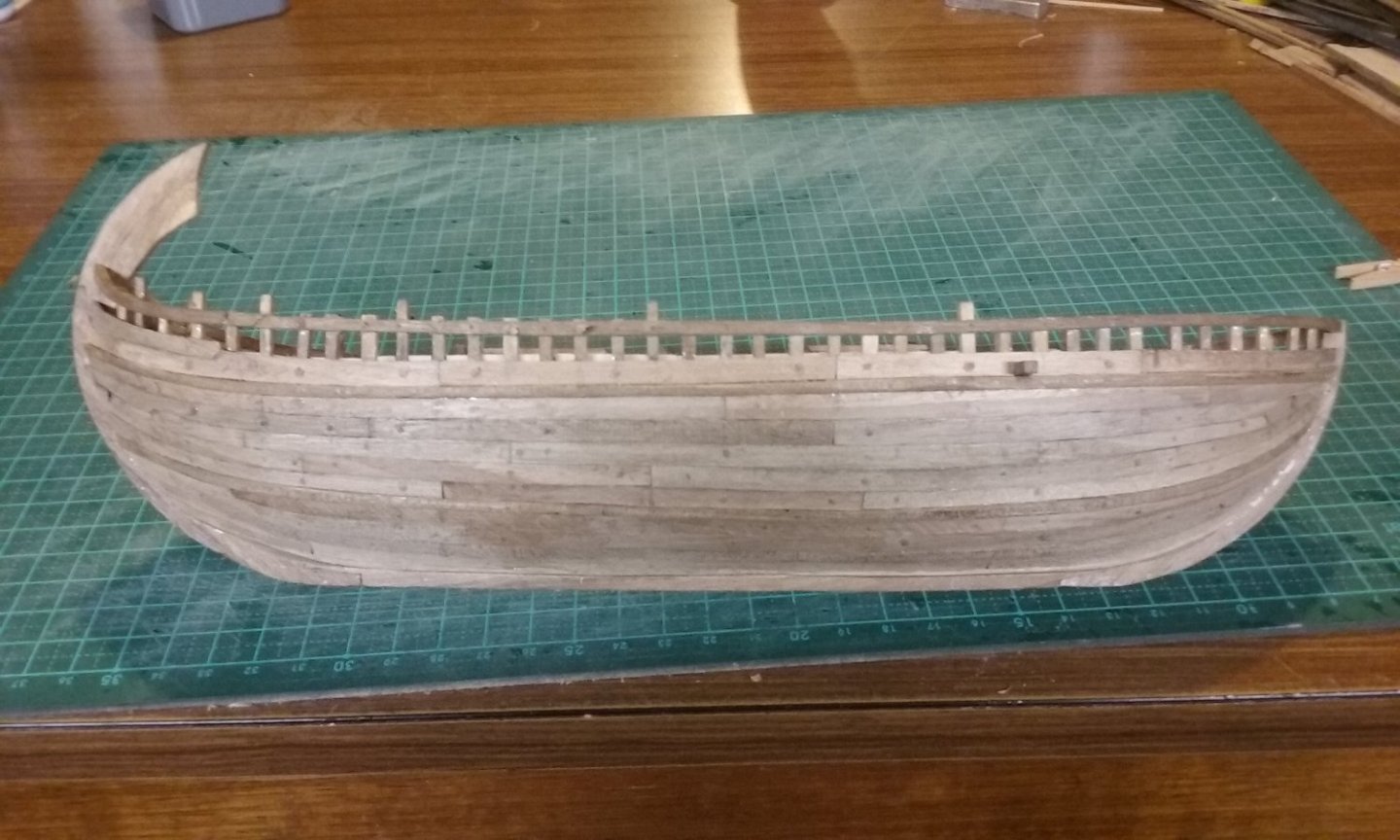

Planking: Only the top row of planks still to do: Adding a stealer to the bow, which curves up rather dramatically. Treenails made of whatever scrap wood that came to hand. And filling the gap on the starboard side. But I discovered the sheer on the larboard gunwale was not correct, so I had to undo the glue and cut the treenails to move it down into a curve that worked better with the top planking: Ah, that's more like it . . . Planking complete on port side (old Goon show joke: Ned Seagoon, on board P & O steamer: "Purser, where's the rest room?" Purser: "Port Side". Neddy: "Port Said??? I can't wait that long!" Antepenultimate plank: Penultimate plank: AAAAAND - Planking complete! Aftercastle and masts dry fitted: (sorry about the picture quality) Steven

- 508 replies

-

Looking for plans or possible models of Magellan's ships.

Louie da fly replied to J11's topic in Nautical/Naval History

J11, did you ever go any further with plans to build Magellan's ships? I just revisited this thread and it's over three years since you posted. I hope you're still thinking about the project - I think it would be very worthwhile. And I (rather late, I'm afraid) got google to translate your Spanish article above It says "The term 'nao' is used for a ship, vessel or boat, although in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries in Spain it was also used to designate a certain type of ship dedicated to transporting passengers and merchandise, moved by sail, without oars, with high sides, a castle at the bow and poop at the stern, a round stern and axial or central rudder. At the end of the 15th century, it was standardized into a ship of a certain size, with a continuous deck, a covered castle at the bow, an awning cover at the stern and a tonnage or loading capacity of 100 to 600 toneladas (= tuns: barrels weighing a ton). It was equipped with a rig capable of withstanding strong winds consisting of a bowsprit or bowsprit at the bow with a feedsail(?) and three vertical masts, of which the foremast and main had a rectangular rig, and a triangular or lateen mizzen, with a crow's nest on the main. At first, it was the merchant ship par excellence, although in the 16th century it also began to be used as an armed or warship, to be used especially in voyages to the Indies." Not really all that helpful, I'm afraid. I've seen somewhere on Facebook someone making a very nice model of a carrack from about the right period with some extremely good plans. I'll see if I can find it. Aha! You can find it at https://www.facebook.com/groups/2235633576538313/search/?q=carrack - look for Caracca Veneziana being made by Giuseppe Chiavazzo - if you contact him on Facebook he may be able to help you. BTW, another point to keep in mind is that the ships wouldn't all have been the same size. If you look at the last photo in post #14 above, you can see carracks of different sizes in a single picture. Basically all very similar, but with differences of detail (apart from size, some have four masts, some have three). And here you have scope for variation - things like the awning at the stern can have the ridge beam running either fore and aft or side to side. If you check out various different pictures of carracksyou'll see other kinds of variation you could introduce to show a bit of variability in the different ships of the fleet. I hope you're still out there to read this Best wishes, Steven -

HMCSS Victoria 1855 by BANYAN - 1:72

Louie da fly replied to BANYAN's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1851 - 1900

Had a sausage sizzle yesterday. Unfortunately as it was in Ballarat, the sun stayed away. But nothing better than Chrissy on the beach! Preferably with your feet being burnt by the hot sand. Steven- 1,013 replies

-

- gun dispatch vessel

- victoria

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Beautiful work, particularly for a first wooden build! Steven

- 24 replies

-

- Ships boat

- Ships of Pavel Nikitin

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

This level of detail helps me understand why you chose such a large scale. Nice work, Dick. Steven

- 30 replies

-

- roman

- merchantman

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

-

Beautiful work, Dick. Is that timber jarrah? Steven

- 30 replies

-

- roman

- merchantman

-

(and 2 more)

Tagged with:

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.