-

Posts

6,651 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by wefalck

-

Very nice machining, but I am not sure that I understand, how such stopper worked. There is some sort of hand-wheel, would that actuate a compressor ?

-

'Penetration' was not necessarily the objective. When rifled canon and solid ogival projectiles were introduced, the projectiles tended to go straight through wooden hull with little damage and small holes that could easily be patched up. The effect of the older round shot was rather different, as their impact would generate significant splintering inside the hull with massive collateral damage to the crew and frayed holes that were more difficult to patch up. With the 'old-style' guns you bought impact by a closer fighting distance, while with rifled guns you did not get the same impact until shells became available sometime later - and functioning impact detonators became not available until after the time of wood walls.

-

Designing my own hull...

wefalck replied to Rom104's topic in Building, Framing, Planking and plating a ships hull and deck

Given the constraints you mention, wouldn't it be wiser to look for plans of a real ship. Then you know that everything will fit together in the end. As you are talking about buoyancy, is this going to be a working model ? People have used styrene for say POB-construction, but that tends to become quite heavy. At 900 mm LOA, you will not have a lot of displacement available. -

Nice model of a subject that one does not see too often, the transition from sail to steam ! I found various plastics, polystyrene, Plexiglas and bakelite-paper very versatile materials, although some people have reservations re. the longevity and stability of polystyrene. On the other hand, at such small scales and for ships built from metal, rather than wood, many parts would be difficult to reproduce in wood, which would take a lot of effort to achieve a smooth metal-like surface. Looking forward to further progress ! I do have an old 1980s catalogue of Underhill plans and he lists indeed a wide range of subjects, but not all plans were drawn by himself. The catalogue usually gives the original author of the plan, I think. Isn't the model of the SERVIA in the Maritime Museum in Halifax, I have a vague recollection of having it seen there.

-

Just looked at the pictures in the gallery, very nice result indeed ! I love these little unpretentious boats, that were just meant to scrape out a living for their owners. I found them more interesting than all the VICTORYs and what not ...

-

At that scale almost indistinguishable from the real thing ! These 'basket' valve handles are interesting. I gather the design was chosen to maximise grip, while minimising mass and, hence, heat transmission - although there shouldn't be any heat in a compressed air loco. Perhaps cold, as the pipe-work certainly would cool down in operation ?

-

The question is how fixed you are on the time-frame and nationality. There are various non-British sources to consider as well ... A colleague of ours (who unfortunately died a few weeks ago much too early ...) wrote a three-part article on the development of the carronades a few years back, but it is in German unfortunately. However, I had a quick look at the reference list to pick some works that might be helpful: Bugler, Arthur: H.M.S. VICTORY - Building, Restauration & Repair, London: H.M.S.O., 1966. - I do not have this book, but it seems to contain some detailed and measured drawings of the carronades on VICTORY (state of knowledge of that time, of course). Lafay, Jean: Aide-Mémoire D´Artillerie Navale, Paris: Librairie Militaire, Maritime et Polytechnique, 1850. - This book is available as eBook from the French National Library: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9737980n.r=lafay arillerie navale?rk=21459;2; it contains details of barrels and carriages of French ordnance pre-1850. Another source of drawings are the archives of the Danish naval yard in Copenhagen. Much of is digitised and can be downloaded. It is difficult to navigate through it, but if you were seriously interested, I can give you some archival references for carronades.

-

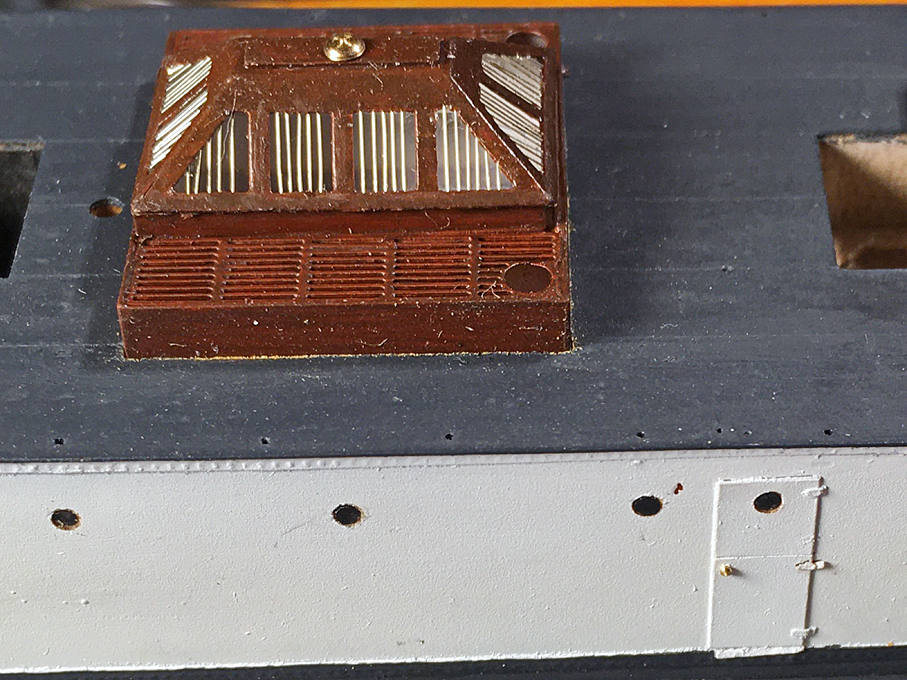

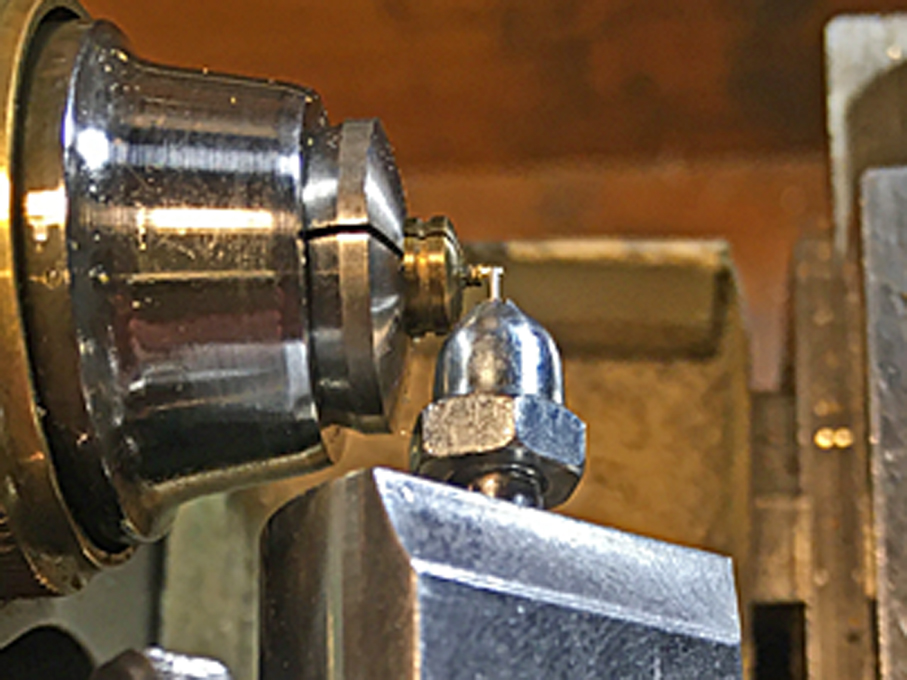

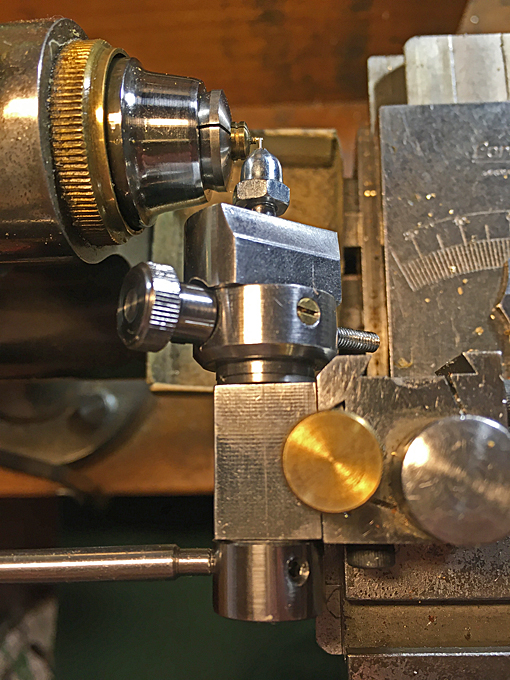

Thanks !!! ********* Door-Knobs I felt like doing some lathe-work, so I tackled the knobs for the various doors in the deckhouse and the back of the fore-castle. That is, I assume there were knobs and not handles. However, it is likely that they used knobs, as handles pose a higher risk of getting caught with some clothing or lines getting caught. I turned these from brass nails. I like to use these as the process of stamping seems to work-harden the brass a bit. Otherwise, it seems to be difficult to get hard brass wires. The target-diameter of the knobs was 0.4 mm, equivalent to 64 mm in real life. It took a number of tries before I had developed a tool-setting and protocol for turning them that allowed me to produce a reasonably uniform set of eight plus a few spares – they do like to jump off the tweezers when you try to insert them into the pre-drilled holes. Turning door-knobs: Step 1 – roughing-out the shape with a square tool The turning proceeded in three steps, namely 1) roughing-out the shape with a square tool, 2) shaping the knob with the ball-turning tool, and 3) thinning out the shaft until it breaks off the stock by itself. Turning door-knobs: Step 2 – shaping the knob with the ball-turning tool Turning door-knobs: Step 2 – shaping the knob with the ball-turning tool (close-up) The tool-bit in the micro-ball turning tool is a broken 0.4 mm drill, the end of which was ground to a cutting angle. It produces nice curling swarf. While turning the knobs was easy, once the right settings had been found, inserting the knobs into the pre-drilled holes precipitated a lot of (mental) bad language … Example of door-knob in place (Grrr … this close-up show every speck of dust and all imperfections) To be continued ....

-

Have any volumes covering the era post-1815 actually been published ? I only see the first two volumes popping up, covering the period 1523-1715 and 1715-1815 respectively. Or is it the same story as with Mondfeld's book, where the later 19th volume was never written/published - a most interesting and large uncovered era in modern literature.

-

Over here in Europe they are very common, probably the most common rig on trawlers. They also replaced, I think, beam-trawls except in the shrimp fisheries. The 'otters' do not actually scrape along the sea-bottom, unlike the beam-trawl, and therefore considered more environmentally friendly.

-

'Otter' are the 'doors'. Not sure why they are called otter, but it probably has to do with the otter-like shape of floats that were used in mines-sweeping gear, where they have a similar function as the 'doors'. The 'Zeese' was held open by the spars projecting from the boat, rather than 'doors' or beams, as in beam-trawls.

-

Slightly off topic: 2009 I lived in Alkmaar, Noord-Holland, and it was the first winter for many years, when they had a period of real frost, cold enough for the canals etc. to freeze over. On smaller ones people could even skate (missed that myself because of other occupations and the thaw came only a couple of days later). The Dutch were looking forward to do the 'Cities Tour' again, whereby you skate from place to place around the Ijsselmeer/Zuiderzee. We also had a little bit of snow and it was the first time my neighbours' seven year old daughter experienced snow. The children around got so exited that day, that I didn't need to worry about cleaning the pavement in front of my house - when I got home from work, they had swept up every snowflake in the neighbourhood to build a snowman The climate now is rather different from that of the so-called Little Ice-Age of the 16th and 17th this is portrayed so vividly in many winter-landscape of the painters of the Dutch and Flemish Golden Age. BTW, the Zeesboot or Zeesenboot (both are correct) uses a particular type of trawl-net that is spread between two booms projecting from the drifting boat - certain types of botters used a similar net and fishing technique.

-

Then I failed 😕 ... the idea was to create the feeling of bright, but freezing cold day - like this: The Zuiderzeemuseum in Enkhuizen in February 2009.

-

Keith, talking about the 'warmth' of a winter-setting with the Zuiderzee frozen over sounds like a contradiction in terms Anyway, thank you very much for your kind words ! Brian, you may have come across material on the Zeesboot on the Web, there is quite a bit, as various specimens have been saved and restored over the decades, even during GDR times. There is also a very detailed building-log for a 1:20 scale model on a German forum: https://www.segelschiffsmodellbau.com/t2889f685-Zeesboot-um-ca-Massstab.html. The text, of course, is in German, but you probably can translate it with the help of Google. It is a wonderful model, I have seen it myself. The model is based on the reconstructed specimen in the Nautineum in Stralsund (https://www.nautineum.de). We held the GA of our association there in 2019 and I have various pictures of the boat.

-

sail plan for Ballahoo (Fish class) topsail schooner

wefalck replied to georgeband's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

'Taking in' a sail would mean to clew it up or fasten, if it is rigged permanently. Otherwise ii would mean sending it down. For instance, the main top-sail with square head would be sent down, as it is always set 'flying'. In later years, when triangular top-sails were used, these could be clewed up to the top-mast. BTW, an indication, whether a square fore-sail could be set would be the presence of foot-ropes on the lower yard. In order to manage this sail there would need to be foot-ropes. At least in the Baltic many, if not most gaff-rigged schooners as well the sloop- or cutter-rigged smacks (whatever they may actually be called) could set a large square fore-sail flying. They did not have a parrel or similar, but were shackled to a stay that ran down the mast. Sometimes they only had a halliard and braces, sometimes only topping-lifts and braces, and sometimes all of them. As crewing was expensive and you probably needed at least three crew (including the skipper) to manage such rig, rather being square this sail was triangular with a single tack fastened to somewhere near the mast. When going about, one needed to attend only to the braces, as there were no sheets. Such schooners seem to have been run sometimes just by the master and a mate or even only a boy. When rigged with top-sails, one would need a crew of at least four. This is talking about the merchant navy.- 22 replies

-

- caldercraft

- jotika

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Are you aware of the concept of table saw push-blocks and -sticks ? Have a look here: https://www.google.com/search?q=table+saw+push+block&newwindow=1&sxsrf=AOaemvKPStG6ZDKxbv40FJt5DdRaG2gdEw:1640887753307&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicqJudj4z1AhWnxoUKHZZLAwMQ_AUoAnoECAEQBA&biw=1276&bih=695&dpr=2 They come in all sorts of guises and configuration, can be mad by oneself or Rolls-Royce-versions can be bought ...

-

sail plan for Ballahoo (Fish class) topsail schooner

wefalck replied to georgeband's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

Nomenclature and terminology can be discussed for hours without conclusive results. People in the old times seem to have been much less preoccupied by this than modern ship-modellers and -historians. One should rather focus on the function. Sail-plans before the end of the 19th century tended to be much more flexible. Wooden spars and the necessarily installations could be changed much more quickly and even at sea, compared to the later ships with steel spars. In desperation, every piece of available canvass could be set somewhere on the masts. The rigging details were also the prerogative of the master, at least on commercial vessels, who would observe the vessels performance and have alterations made, if needed. Concerning the description/definition of a 'flying-jib', I think there are two possibilities: it could be the head-sail that is set from the 'flying-jib-boom' or it could be an outer head-sail that is set flying. I am not certain about the actual time-frame, but I think around the middle of the 18th century the jib-boom was extended with another spar, the flying-jib-boom. As the term indicates, it was not rigged all the time and in consequence may not have a stay attached to it. Around the second quarter of the 19th century it tended to become a permanent feature, at least on larger ships, and merged into one spar with the jib-boom. In consequence, the jib-boom now had two stays attached to it, namely the fore-topgallant-stay around its middle, and the fore-royal-stay at its outer end. This now allowed the once really flying jib-sail to be attached with hanks to the fore-royal-stay. ___________ I have some reservations towards Marquardt and Mondfeld, which are not meant to diminish their merits in anyway. However, one should always try to corroborate their information with other sources. I think after the 1980s, when his writing activities really began, Marquardt did not have access anymore to much original European sources, so he draws on the observations he made in the decades before and on the models he restored between the end of WW2 and his emigration to Australia. The good thing is that he did not venture much outside the 18th century. To the contrary, Mondfeld began for commercial reasons to cover periods and regions in his later works on which he seems to have had only limited knowledge. It would be quite difficult for a single person to have a real in-depth knowledge of the whole sailing-ship era in all countries, but this is what his modelling encyclopedia seems to attempt. To be honest, I do not own any of his books, but looking over them occassionally and what I hear from others seems to support this perception.- 22 replies

-

- caldercraft

- jotika

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

Yes, it is rather strange, how often we do things against better knowledge and spite of recognising at the moment that we shouldn't do it ... I gather it is often lazyness ... My father had a peculiar way of rolling up his shirt-sleeves, not inside-out, but outside-in. He explained to me that he was taught that by his father, who trained as locks-smith, joined the Imperial German Navy in the early 1900s and after WWI worked on shipyards. The purpose was to prevent sparks or hot metal swarf from being caught in the rolled-up part. There used to be special blouses and overalls for mechanics operating lathes etc. that had very close-fitting and buttoned cuffs and where cut with sleeves as tight-fitting as possible.

-

sail plan for Ballahoo (Fish class) topsail schooner

wefalck replied to georgeband's topic in Masting, rigging and sails

I cannot really contribute to the actual substance of the discussion, but I think one should keep in mind that until at least the early 19th century it was more common to denominate ships by their hull shape than by their rigging. A particular hull type could have different rigs and the rigging layout, indeed, may change over its life-time. So the first example above refers to an 18th or early 19th century type of ship that was constructed on the Bermudas or other (British) islands in the Caribbean. Sometime in the early 20th, I think, perhaps through the so-called Huari-rig (a very steep gaff, almost parallel to the mast), on yachts and pleasure boats they began to do away with the gaff altogether - resulting in a triangular sail called a 'Bermuda'-sail. This is what Underhill illustrates here, an early- to mid-20th century schooner-yacht. The underlying reason for this development probably is that 'Bermuda'-sails are less top-heavy and require less power/crew to hoist them. OK, the log-books are probably authoritative, but it seems somewhat strange that no square fore-course should have been foreseen. Many contemporary illustrations show them, but they would have been definitevely fair-weather sails and mainly used on suitable courses, when top-speed was called for. They seem to have been also common on commercial schooners (even, when not having top-sails) in northern European waters right to the end of the sailing-ship period. They may not have been permanently bent and in the HMS WHITING, there may not have been an occasion/need to bring up such large sail, hence it was not mentioned in the log-book. Concerning the flying-jib: I wonder, whether it would have been really set that high up on the mast. I seem to have seen this only on more modern vessels (such as the North American fishing schooners) and in combination with an outer jib. The term 'flying' basically refers to fact that it was not attached to the stay, but only to the outhaul and halliard - in this way it could be quickly set or stroke without crew laying out on th jib-boom. Yes, Marquardt was German and only went to Australia in the 1980s in search of more gainful employment in the car-industry for his drafting skills, I seem to remember. His terminology seems to be contaminated at times by his native language (I am not judging, as this happens to me as well). In addition, to his books, he also published numerous topical articles in relevant English and German journals, that may be worthwhile perousing. Nice piece of research, btw. 👍- 22 replies

-

- caldercraft

- jotika

-

(and 4 more)

Tagged with:

-

That applies even more so to cars and motorcycles ... 😈 Another good principle is to make yourself always aware of the potential trajectories of workpieces or tool-parts coming off a machine and keep your body and mainly your face out of the way, if possible ... or use safety-shields. When using a lathe, try to opt for collets, rather than 3- or 4-jaw-chucks whenever possible - they are inherently safer. A worthwile investment, as they also have less run-out.

-

Acrylic paint retains a slightly rubbery consistency for a long time. This is due to the time it takes for the water to diffuse out of the interlocking mat of acrylic molecules. It may not be possible to sand for weeks, depending on the thickness of the paint layer. For the same reason, acrylic paint will initially not adhere that strongly to most surfaces and can be easily peeled off. Building up the paint from very lightly sprayed layer accelerates the overall process. Rather than using paper and perhaps even a sanding block, I would use very fine steel-wool (say 0000). Another possibility is pumice applied with a humid paper towel. However, as others have asked, why would you want to sand the paint at all ? If there are specks of dust or other imperfections, the above methods will help.

-

Well, you should actually be happy that the caulked seams are shallow and that the wooden plugs are barely visible: On the real thing, the caulked seams may be a couple of millimeters deep in dry weather and may protrude a couple of millimeters, when the planks are really wet. On average the seams are flush with the deck and that's how people wanted it. The bolts or nails with which the planks are fastened to the beams are sunk in and the holes are plugged with wooden discs cut from the same wood as used for the planks and cut perpendicular to the grain - the objetive was to make them as little visible as possible. They are also inserted with the grain in the same direction as the planks, so that they expand and shrink in unison with the planks. So, less is more On modern ships, the planks would be caulked with 'oakum' and the seams filled up to deck level with molten bitumen, which then would be scraped clean to the deck. So you would have a black seam of about 1 cm width, which translates to 0.03 mm in 1/350 scale ... My painting technique is to spray-paint say in Vallejo 'wood', perhaps run a sharp engraver's chisel along the seams once the paint is dry, remove the fuzz lightly with very fine steel-wool, and then run a 0.1 mm permanent felt-tip pen along the seams, wiping off the excess immediately. In the next round, random planks are picked out with a brush-washing of the base colour to which a tiny amount of white has been added. The procedure is repeated with another set of random planks, adding a tad more white. Depending on your patience, you can do this several times, varying the base-colour just by a tiny shade.

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.