-

Posts

645 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Everything posted by Dziadeczek

-

Hi Tomek, What are you complaining of? The model is excellent (IMHO). It reminds me of some wonderful cardboard models built and shown here by Abe Hoving, a Dutch historian and modeler. I have a million questions, if I may. 😁 Is the model built from a kit or is it your own design? What are the deadeyes and blocks cut with? A laser, perhaps? Your English is very good (I did not notice any mistakes). I have never before encountered these "waistcloths" (okrycie szancowe). Interesting! I think that you reproduced them very well. I enjoyed reading your historical note on the Battle of Oliwa and the circumstances leading to it. Great! Congratulations on your built! Another Tomek

-

Has Anyone Used Surgical Binocular Loupes

Dziadeczek replied to rraisley's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

As Gaetan has already noticed, it is important to consider the so called, Working Distance, which means the distance between your eyes and the working area, where the detail is in focus. In the case of a surgeon, this distance is typically greater, since the operator is usually standing next to the table/patient. In the case of a shipmodeler, the person is generally sitting at the table, hence this distance is typically shorter (about 250 - 350 mm in my case). For a long time I have been using a common Optivisor and it works for me. Sometimes I just wipe off the lenses from wood dust with a dry rag or a paper towel, nothing else (the frames are from plastic, but the actual lenses are of glass, I think). Before you buy anything, measure this distance for yourself and make sure you get your magnifier within this working distance, otherwise it will be very uncomfortable for you to use it, or you'll be forced to stand next to your model, while building it. Also, usually magnification of 2x is sufficient, sometimes a bit more, perhaps 2.5x, when you are working on a VERY minute details, like rigging and such. (we are not talking here neurosurgery and sewing up minute nerve fibres). -

In addition to the paint quality, very important is the application method. Early Renessance artists used to grind their own pigments by hand - resulting in various sizes granules, hence excellent paint quality, unlike the modern electric mills, which grind everything in the same size powders, resulting in 'boring' look of the paint. Grounding (the way of priming the surface) was also critical. The best was priming using gypsum media - lean, white and uniform, suitable for tempera, egg tempera or oil paints! One of the great earlier Flemish artists, Johannes van Eyck, devised and popularized egg tempera - a tempera pigment mixed in yolk of an egg - this resulted in one of the most permanent paints, that after half of a millennium still look like they were painted yestarday. (Google "The Portrait of Arnolfini" to see it yourselves in a large resolution). These artists painted with the technique of "laserunek" (Polish term) - the so called "glazing" - multiple layers, one on top of the others, of exceedingly thinly applied paint, heavily diluted in oil in such a way, that earlier layers were visible through the later ones, coming through. It could be more than 10 layers of a detail in a painting, like various shades of skin, jewelry pieces, fabrics, lace...! The end result was a middle color comprised of all intermediate ones. A painting like this was very intense in color and light - you could see it even in near darkness, it had its own light! Also, in those times, there was a separate profession - people preparing wooden panels for artists - they were made from boards of hardwood attached together (tongue and groove usually) into a required size and grounded with that primer - gypsum powder mixed with rabbit skin glue together to form a thin paste similar to watery cream. Those people produced the best panels for artists (I am talking about the era before artists used canvases, which were used later). I encourage you to watch the movie mentioned earlier in this thread - "A Girl with a Pearl Earring" - it shows you, among other things, the steps of preparation of the pigments, grounding them and mixing with linen oil, with all the attention to detail. Also, the technique of painting itself is shown. Vermeer Van Delft was one of the most preeminent artist of his times, known for the quality of his works, which can be appreciated and admired today... One of the mistakes Leonardo made with his "Last Supper", was that he painted it on a dry stucco, instead of fresh, wet one (hence the name al fresco). This resulted in very unstable painting, which quickly started to deteriorate and even today is still deteriorating. So, the paint quality was one variable, but there were other as well...

-

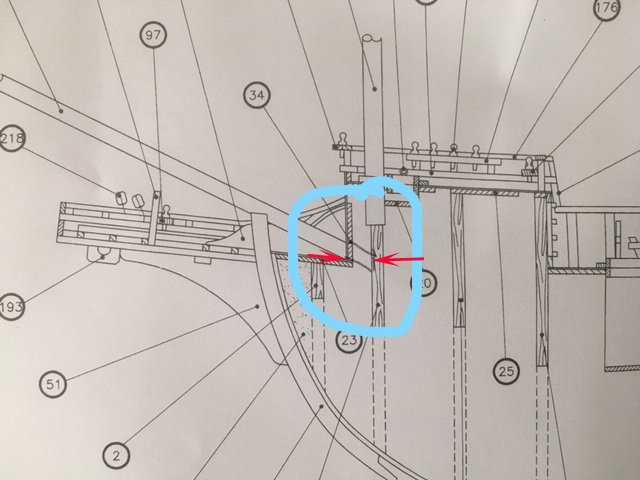

"...After some time upon finishing the model, I noticed that those plastic deadeyes started breaking under tension from shrouds, specifically those tiny eyes on top of each deadeye (?). I would advice you to replace them all with wooden ones and rig them properly..." This is one of the few spare deadeyes from the original kit. Notice the little eye (marked with a red arrow). They want you to attach the chain plates (straps) to this eye, instead of wrapping it around the deadeye. After a while, the strain on the eye breaks it off the deadeye and you'll end up with loosely hanging shroud, which has to be replaced... Hence my recommendation to use wooden deadeyes and have a piece of mind, instead of using these plastic ones. Also, there are other inaccuracies of the kit - the tops are round, which is a bit archaic for the era the ship was built in. They should rather be rectangular and only rounded up in the forward part, like other ships from the end of XVIII C. Also I have doubts about the stern... But, overall, the kit makes a nice looking model, especially if you want to bash it a bit...

-

This was my first kit I built many years ago. I too had difficulties with rigging (had only two sheet of plans printed on both sides of paper). Instruction booklet was not much help... ZuMondfeld helped me a bit, I remember. After some time upon finishing the model, I noticed that those plastic deadeyes started breaking under tension from shrouds, specifically those tiny eyes on top of each deadeye (?). I would advice you to replace them all with wooden ones and rig them properly.

-

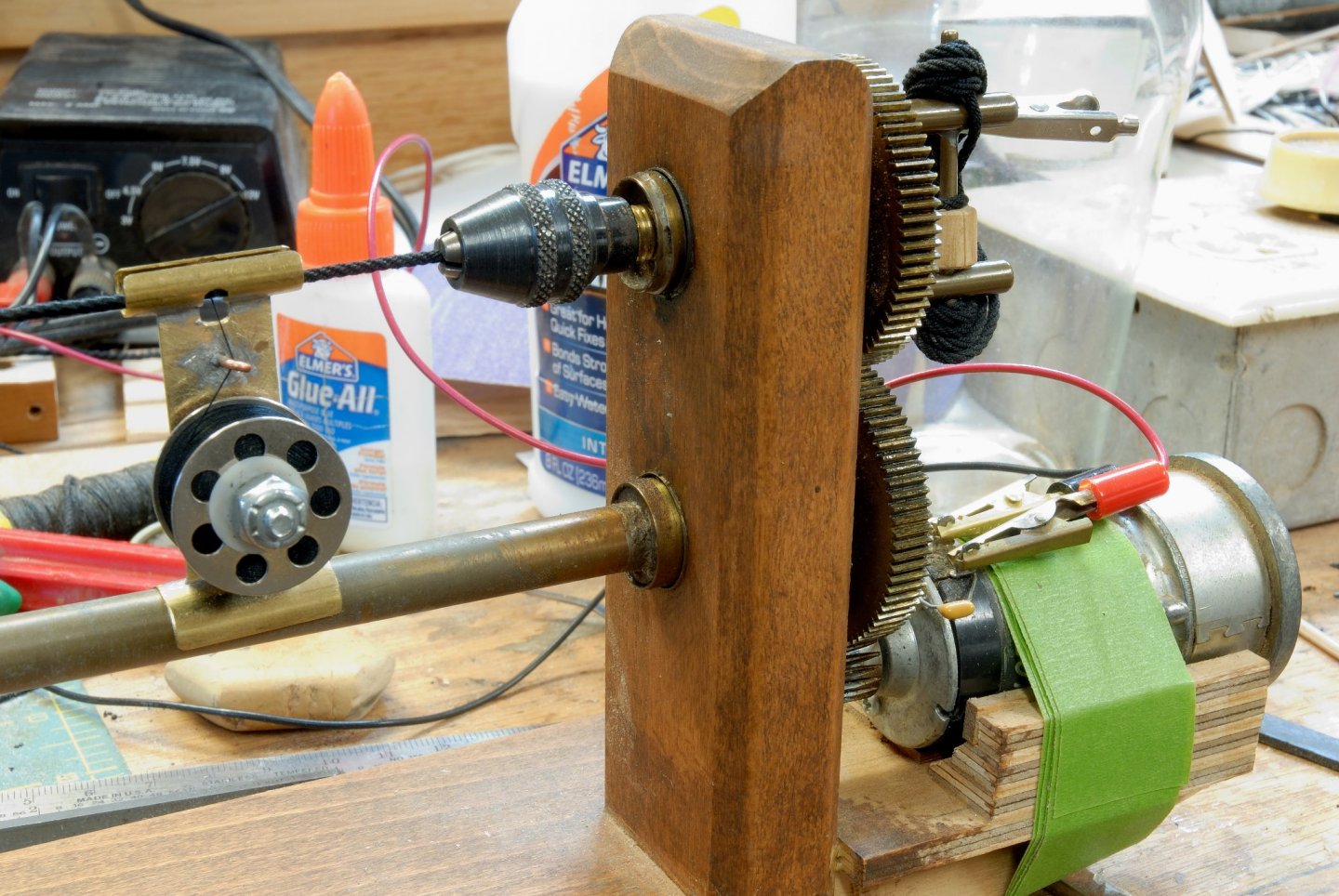

If you do a lot of serving, it pays to fashion from scraps of brass a small device, that is suspended under the served rope and contains a spool of thread for serving, is moving along the rope while serving it simultaneously. A sort of, small variation on the so called, bow string server, used in archery. I made one long time ago and it works perfectly every time. I also made a long(er) serving machine - mine is 2.5 ft long and powered with a DC motor, so the entire process of serving is fully automated, hands free, and the serving is very even and tight along the entire length of the rope. Here is one of the served stays for my model of the French 74 gun ship 1:48.

-

Papegojan 1627 by mati - FINISHED - 1/48

Dziadeczek replied to mati's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1501 - 1750

Thank you, Mati. -

Papegojan 1627 by mati - FINISHED - 1/48

Dziadeczek replied to mati's topic in - Build logs for subjects built 1501 - 1750

Outstanding model and the attention to detail! Congratulations!!! Can you share the secret, how did you achieve the dark grooves in your rigging? Staining the lines and immediately rubbing it off, perhaps? Thomas -

Are there any decent clamps?

Dziadeczek replied to bigcreekdad's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

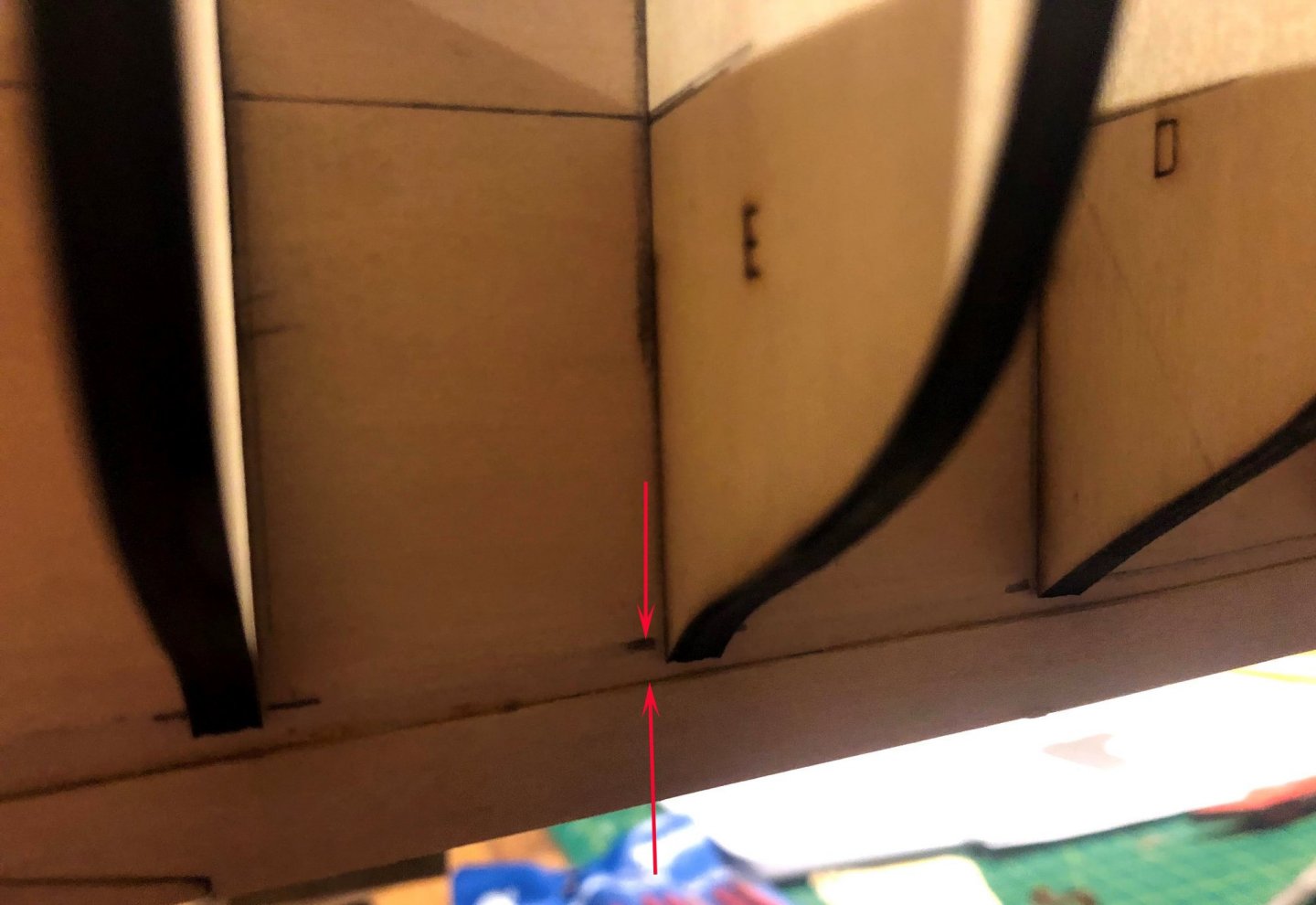

After all these years I found out, that if I properly spill and heat bend my planks off the model, I don't need any planking clamps afterwards. The planks should lay on the bulkheads almost perfectly, you only need to gently press them in place. For this I use ordinary sewing pins, sometimes those with colored heads. I gently tap them into a bulkhead with a small jewelry hammer, maybe two or three times - just enough to hold them in there, placing the tip of a pin directly under the edge of the plank, NOT THROUGH IT! That way, I don't end up with a hole in the plank, but rather a small hole In the bulkhead (which will be covered by planking anyway, so it won't be visible). This is my old model of the MS Rattlesnake, showing this process. -

He is doing it correctly. La Créole 1827 by archjofo - Scale 1/48 - French corvette - Page 59 - - Build logs for subjects built 1801 - 1850 - Model Ship World™

-

Miniature Drill Bit Chuck for Dremel Tool?

Dziadeczek replied to turangi's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

There is also the Pfingst rotary tool... -

Youtube photoetching tutorial

Dziadeczek replied to Nirvana's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

For more info on the topic, check out this link: Photo Etching - do it yourself - Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings - Model Ship World™ I did not use the Micro Mark kit, since my pieces had to be way bigger - hence I had to build my own UV exposure lamp, get a bigger laminator and a bigger developing tank. I based the entire procedure on the very informative tutorial by Gene Berger (link included in the above mentioned thread), so I used different chemicals and exposure parameters than those proposed in the video. There are many ways to "skin the cat", one has to choose what is better for him and what is available in his area. This is definitely doable at home, but it is a learning curve - one has to determine all variables based on one's trials and errors. Do not expect to do it once and end up with gorgeous results! Patience!!! Have fun... -

If it is Butapren (which I think it is), than its equivalent in the US is contact cement. Butapren also stinks fiercely, so I wouldn't use it for shipmodeling...

-

When Divers Located The Ship That Survived Pearl Harbor, They Saw What Sank WWII’s Toughest Vessel (likeswifty.com)

-

Model Photography/Scheimpflug Principle

Dziadeczek replied to Charles Green's topic in Modeling tools and Workshop Equipment

Some time ago I took this pic of my (unfinished) model of the Rattlesnake, using focus stacking and Photoshop. It works. -

-

Here is an email address I got earlier today from a friend in Canada for Wendy in Australia, (he uses her sewing skills for his models and swears by her). shipwheel@bigpond.com He also took the trouble to inform her that you would be inquiring about the sail set for your model. So, I think she will be expecting your email soon and you both can discuss the particulars. Regards, Thomas

-

In the good old days of the Seaway's Ships in Scale forum, there was a woman called Wendy from Australia, who used to take custom orders for making sails for models. I don't know her personally and never ordered anything from her, but supposedly her sails were excellent. If you are interested, I could get you in touch with someone who got her sails, and find out if she is still active. Thomas

-

Silver soldering

Dziadeczek replied to Dziadeczek's topic in Metal Work, Soldering and Metal Fittings

Thank you all for your input. After some thinking, I decided to go with a silver-enriched solder wire I obtained long time ago from Home Depot. I don't think it is called Stay Brite, but I forgot its exact name. I remember that it can be applied either with a soldering gun or with a torch and it is significantly stronger than regular 50-50 or 60-40 wire. I have a tiny soldering pen that gives me a lot more control than a mini torch, so I've been able to resolder those broken joints with this wire and give it a bit thicker joint (previously I was filing off extra thickness of solder to make it as thin as the brass rings. That turned out to be too thin and week). The joints will be covered with a rubbing pounch anyway, so they will be invisible. The solder joints don't get as black as the brass with Birchwood Casey, so I use just for these spots a different blackener - used for stained glass work, which seems to work there somewhat better. Thanks again Everybody!!! 🙂 -

Hi, I need help with the silver soldering of small brass parts. I am trying to make brass reinforcing rings for the masts of my 74 gun ship model. I prepared (cut) thin strips from a brass sheet and soon after I solder both ends together to close a ring, frequently they spontaneously break apart. I need a stronger medium. I tried to silver solder them, but every time I try to heat them, the flame from my torch immediately blows the tiny sliver of silver away from the place i put it, even before it gets melted. How do I keep it there?

About us

Modelshipworld - Advancing Ship Modeling through Research

SSL Secured

Your security is important for us so this Website is SSL-Secured

NRG Mailing Address

Nautical Research Guild

237 South Lincoln Street

Westmont IL, 60559-1917

Model Ship World ® and the MSW logo are Registered Trademarks, and belong to the Nautical Research Guild (United States Patent and Trademark Office: No. 6,929,264 & No. 6,929,274, registered Dec. 20, 2022)

Helpful Links

About the NRG

If you enjoy building ship models that are historically accurate as well as beautiful, then The Nautical Research Guild (NRG) is just right for you.

The Guild is a non-profit educational organization whose mission is to “Advance Ship Modeling Through Research”. We provide support to our members in their efforts to raise the quality of their model ships.

The Nautical Research Guild has published our world-renowned quarterly magazine, The Nautical Research Journal, since 1955. The pages of the Journal are full of articles by accomplished ship modelers who show you how they create those exquisite details on their models, and by maritime historians who show you the correct details to build. The Journal is available in both print and digital editions. Go to the NRG web site (www.thenrg.org) to download a complimentary digital copy of the Journal. The NRG also publishes plan sets, books and compilations of back issues of the Journal and the former Ships in Scale and Model Ship Builder magazines.