Bob Cleek

-

Posts

3,374 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Posts posted by Bob Cleek

-

-

-

A relatively mild solution of oxalic acid ("wood bleach" in the paint and hardware stores) or citric acid in water swabbed on will bleach teak well. I never heard of the Navy's concoction you described. "Boiler compound" is some really nasty stuff. It's a very strong base and highly caustic. Mainly a sodium hydroxide/morpholine mixture. It's used for neutralizing acidity in boiler water. When it hits certain metals, it generates explosive hydrogen gas. When it's mixed with water, it creates heat. Burns when it comes in contact with skin. Thanks for the tasty bit of nautical trivia!

- hollowneck, Keith Black and mtaylor

-

3

3

-

Interesting article. It's another example of why fiberglass or epoxy "encapsulation" does not work. Anybody who's worked on wooden boats comes to know this, but the "fad" seems to continue nonetheless. Coating wood with plastic resin does not make it "impervious to rot!"

-

You might consider masking with friskit and airbrushing. This can be tedious, but less so than hand painting and you'll be assured of razor-sharp edges. Search for "friskit" on Youtube and you'll find many excellent tutorials on using this masking material which is readily available at most all art supply stores.

-

Came across these guys today. https://www.handlaidtrack.com/scalelumber I don't know anything more about them beyond their website.

-

Oh... "...windows for gunports." When I saw this listed on the home page as "Best tool for cutting wind..." Well, I thought it was going to be a much more interesting thead!

-

On 10/11/2019 at 1:12 PM, druxey said:

Bob Cleek: Smalt (another blue pigment) was readily available and economical prior to the invention of Prussian Blue. But we digress.

Ah, yes, indeed we do digress, but that's exactly how trivia wonks like ourselves amass our great store of questionably useful information!

Smalt is ground "cobalt glass" used as a pigment. It's the color seen in blue medicine bottles, Venetian blue glassware, and Chinese and Dutch "Delft blue" pottery. "Cobalt glass," quartz glass made blue by the presence of cobalt oxide and potassium, is near exclusively used in glassware and pottery glazes. It was widely used by some fine artists during the Renaissance because it was another cheap substitute for lapis lazuli pigment, but it never was all that satisfactory as a paint pigment because, for reasons unknown to me, unlike when it is used in glassware and pottery glazes, when Cobalt glass is ground up to be used as a paint pigment, its color is unstable and it discolors fairly quickly. Renaissance paintings containing smalt pigment don't look blue at all today. There wasn't much point in using it in the quantity necessary for structural and marine paint applications because of its cost and color instability.

- Keith Black, mtaylor, druxey and 1 other

-

4

4

-

19 hours ago, rwiederrich said:

Tanning, taring, oiling, varnishing these members to preserve them will in fact gather dirt and all manner of debris (Not failing to mention that these preservatives themselves are dark)....discoloring them to dark brown or grimy black. Reason why I used the Constitution rebuild as an example. These smart restoring folks know what we are talking about...that is why they chose to represent the rebuild with black line and fittings.

Lets not forget the effect of tarred rigging on ships' decks, either. Most know that wooden decks, primarily on naval vessels, were "holystoned" (sanded with sandstone 'bricks" and washed down with seawater) to keep them "bright." Teak, especially, benefits from this treatment, bleaching to an attractive "white" color when freshly holystoned. (Unfortunately, this treatment, essentially sanding the surface of the deck, is very hard on the wood and accelerates the need to replace them.) This was done regularly in earlier times and the British Admiralty and US Navy were much enamored with doing it, especially immediately before making port, so the vessels would look "shipshape and Bristol-fashion." The reason this was done at all sometimes seems lost on ship modelers who favor holly and other "white" wood for decks, particularly on merchant vessels. Holly for decks is a bit bright for my taste in a model, as even bleached teak would appear darker at "scale distance," but it is pretty close to the same color as a bleached teak deck up close in real life. (I don't believe teak decks were common in British naval vessels anyway, at least until England became firmly entrenched in South Asia and commanded a seemingly endless supply of the stuff and a well-established trade route to ship it back to England. Teak's propensity to splinter on impact was also problematic on naval vessels, even considering that teak splinter wounds were less likely to fester owing to teak oil's antiseptic properties than oak splinters with their high tannin content. )

As for the real color of period sailing ships' decjs, providing they weren't kept holystoned, they ended up being pretty dark. (You can look up the old Admiralty orders. At one time regular holystoning was mandated until they realized how much it was costing them to replace decking!) In hot weather, particularly in the tropics, the tar on the miles of tarred rigging aloft would thin in the heat and drip down onto the deck below, as would the tow from the cordage. Particularly in the doldrums where there wasn't a lot of wind to blow the tow overboard, the decks would accumulate a lot of bits and pieces of broken strands from the cordage. (Hence the daily bosun's call, "Sweepers! Sweepers! Man your brooms! Port and starboard. Fore to aft!") The black pine tar with the tow stuck in it created quite a black, sticky mess, which, of course, was tracked about by the sailors' (often bare) feet. So, if one wants to be really accurate about it, and isn't depicting a naval vessel that's tricked out "shipshape and Bristol-fashion" for inspection, or a merchant vessel, most of which gave little or no thought to appearances (excepting the passenger-carrying Blackwall frigates and clipper ships,) a rather dark brown colored deck would be the more accurate depiction. Real pine tar, as great-smelling and useful as it was, and still can be, is also a nasty, filthy, sticky stuff that gets all over everything and ends up being tracked everywhere.

- Keith Black, mtaylor, jchbeiner and 2 others

-

5

5

-

There's nothing like the smell of tarred hemp in the morning...

I used to work near the cable car barn and "wheel house" in San Francisco. It's a working museum and you could go in and see the cable wheels turning to pull the cables that pulled the cable cars. They tarred the steel cables with real pine tar and the place smelled strongly of it. I used to stop by just to watch the Victorian machinery running and smell the pine tar. Great stuff. One outfit even sells pine tar scented men's cologne.

If you want to really be accurate, use the real deal on your models! Kirby Paints in New Bedford, Mass. has been continuously selling marine paint in New Bedford since 1846. They still sell real Stockholm tar exactly as it was made two hundred years ago. It's 100% historically accurate and made from kiln-burned pitch pine. (You can buy the cheap modern-made pine tar by the gallon from Walmart, even, but it's not really the same.) Give George Kirby III a call and he'll fix you right up. I don't know another paint company you can call on the phone and have the owner answer! https://kirbypaint.com/products/pine-tar

Kirby's makes pine tar soap, too. For manly men. (They make a lighter version for the ladies.) https://kirbypaint.com/collections/kirby-standard-goods/products/new-papa-kirbys-pine-tar-soap

Kirby's makes some of the best oil based marine paint around, as well, of course. Great people. Great service.

-

2 hours ago, rwiederrich said:

Since none of us are first hand experts, to weather blocks or deadeyes of period ships....(and generally any ship built between 1700~1900), were weathered brown or black based on the material supposedly used to preserve standing rigging at the time....is actually factual....we have to do a lot of guessing based on preferences..

Okay, I'll bite. No, I wasn't actually there back in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, but I've used enough pine tar on enough cordage, blocks, decks, and other wood not to feel like I have to add the disclaimer, "IMHO." I know firsthand how it looks and how it weathers. There's several options.

Real pine tar ("Stockholm tar") is dark brown, almost black, colored, The more coats you apply, the darker it gets. (It's much like orange shellac in this respect.)

Straight pine tar on new wood: This with bring out the figuring and darken the wood, as might be expected of any "oil."

Straight pine tar on old wood, multiple coats: Dirt and dust will make it darker still. Mold will often grow in and on the wood surface beneath the tarred coats and make it darker still. So, depending upon how many coats of tar have been applied, it will eventually look darn near black, or sort of a charcoal grey eventually when in use.

Color of blocks and shells when tarred: This depends upon the species of wood used. At the top of the list was lignam vitae, which was always hard to come by. It's a dark brown color. Locust, another dark wook, was another favorite, As mentioned above, tarring the wood makes it darker. Weathering makes it darker still. It ends up black or charcoal grey eventually.

Pine tar with lampblack on wood: I'm not sure of the date this started, but was a pretty common thing eventually. They say it made the tar last longer, which it probably did, slowing down the UV degradation. This was not used on running rigging cordage. Only on served standing rigging.

Painted wood: Pine tar and lampblack early on. Later pine tar, lampblack, and a bit of Japan drier. Ultimately, linseed oil and lampblack with a bit of Japan drier. All thinned with turpentine. The color of this was black, obviously. Pine tar and lead oxide with a bit of drier made white paint. White's reflective qualities made it even better than black for withstanding sun damage.

Most cordage was hemp and hemp cordage must be tarred to preserve it in the marine environment. Running rigging is tarred with thinned pine tar, turpentine historically being used as the thinner. When manufactured, the yarns of the larger diameter cordage were run through heated copper troughs of thinned pine tar, then spun. They were able to run the yarns through rollers that, by squeezing the yarn, could regulate the amount of tar on the yarns and in this way vary the qualities of the cordage produced. "Small stuff" was spun first and then dipped in thinned pine tar. When tarred, new hemp cordage is a fairly dark golden bronw color, but it darkens with use (picking up dirt.) Weathered, it's a grey-ish brown color. Manila cordage isn't really suitable for the marine environment because it shrinks when it gets wet and, if tied, and gets wet, the knots are very difficult to untie. Light straw colored running rigging wasn't used on boats and ships. (It was sometimes called "Manila hemp," but that was because all cordage was called "hemp" back in the day. It's not made of hemp at all, though.) White colored cordage was never seen until the advent of the synthetic fibers after WWII. While frequently seen today, white or other light colored lanyards run through deadeyes is a glaring inaccuracy on any ship model prior to circa 1950 or so. Hemp production was once a huge industry, but was pretty much rendered obsolete by synthetic fibers, not to mention a "certain prejudice" against hemp that arose in the 1930's when marijuana was outlawed. It's rare to come across a length of hemp line these days, but well broken in hemp line is wonderful stuff. It's soft and supple, yet very strong.

As for other colors, forgedaboudit! The only blue pigment available until 1704 was ground up lapis lazuli, which was hugely expensive. Artists used it. Nobody was painting ships and boats blue until a German guy discovered how to make Prussian Blue. In 1828, a Frenchman created another blue, French Ultramarine. Yellow was not as expensive, but pretty much the same. It wasn't until 1820 that Chrome Yellow was available at a reasonable price. Until mid-Nineteenth Century, the world was pretty drab, at least outside of artist's colors. Lots of blacks, whites, yellow, red, and brown ochres and rust oxides. (The "red barn" wasn't a fashion statement. It was just a cheap color, as was "red lead" used in marine construction.) Those rainbow colored Mayflowers, Ninas, Pintas, and Santa Marias... no way!

Nobody's going to go wrong coloring standing rigging black, running rigging medium to dark brown, or deadeyes black or dark brown. Remembering "scale viewing distance," it's pretty much going to look black or charcoal grey with a touch of brown on a model. Given what we do know of the history of the maritime trades, many of which are still practiced today by some, I don't see any argument that can adequately justify the "oak colored" deadeyes and "white" or "straw colored" lanyards we see on some models today. Except of course that is the was the model maker felt like doing it for who knows whatever reason.

Real pine tar:

- Keith Black, CDR_Ret, catopower and 7 others

-

10

10

-

Got ya beat, jud! I did the "punch card two-step" as an operator on IBM 360s on one of my working-my-way-through-college jobs at Standard Oil about 50 years ago. I remember, in those pre-internet days before "sexual harassment" and "hostile work environments," the programmers would work up printouts of the Playboy Playmate of the Month foldouts using ASCII characters as a "dot matrix" and print them out on tractor feed paper and pass them around. On a later college job, working for ITT Telecommunications when ITT was setting up the DARPA-net, the operators were sending that "ASCII art" out on the 33 and 100 KSR teletype terminals of what eventually became the internet. "Computer graphics" have come a long way since then, and I can't claim to be a CAD maven by any stretch of the imagination, but for modeling purposes, I find the old-time "ducks and battens" drafting technology is easier and faster for me, at least as far as what I need for ship models. I suppose it's different for younger folks who never learned "mechanical drawing" in high school when is was taught everywhere and for those who have mastered one or another of the CAD programs and kept up with their developments, often on the job, but when the contemporary hand drawn lines of period ships scale up to an inch or more wide at full size, I'm not sure I understand the point of trying to work with them at the "space age" tolerances of today's CAD software.

-

45 minutes ago, wefalck said:

Only, if coal tar was used, say post 1840s.

In my experience, pine tar tends to pick up dust and dirt and turns "black" in use eventually. I'm not sure of the exact date, but at some point, I've heard they also added lampblack to pine tar to produce a rigging "slush" that was decidedly black in color. I'm not exactly certain why they did this. It may have been that the darker color served to limit UV degradation of the tar.

- mtaylor and Keith Black

-

2

2

-

8 hours ago, bruce d said:

Without more insight from the original poster it is difficult to know if the problem is solved. However, the thread has covered some useful ground and it seems like a good place to point out another tool: proportional dividers.

I use them and they are as helpful now as they were decades ago when drawing offices had no scalable digital images or CAD systems. Just pick 'em up, set the scale and shazam, it works. Here is one:

https://www.artsupplies.co.uk/item-derwent-scale-dividers.htm

Also, they are easy to make.

HTH

Bruce

The "scale dividers" pictured in the link above are for artists' use and are rather crude. For modeling use, what one wants is a highly accurate set of "proportional dividers." The best ever made can still be found on eBay for relatively reasonable, and sometimes "steal me," prices. See this MSW thread about them:

-

On 10/2/2019 at 1:31 PM, druxey said:

Pantographs were originally used for enlarging sketches, not scale drawings. As remarked already, scan and print to the size you need is far more accurate and reliable!

I collect mechanical drawing instruments and have a fairly good metal pantograph, although not one of the fantastic contraptions that were once (rarely) sold back in the day. As druxey said, pantographs were generally used for sketch enlargement, and not for highly detailed changes in scale to close tolerances. It's my understanding that when they were used at all in technical drawing, they were used primarily to transfer points of a scaled drawing. The scaled drawing was then redrawn using the transferred points for reference and these were checked for accuracy, of course. To enlarge or reduce a curve, the pantograph would be used to lay out a series of points and then standard drafting curves, rather than the pantograph, were used to draw the curve itself.

This is what the "professional grade" pantographs looked like. They're now very expensive collectables. They weren't cheap to begin with and few have survived with all their parts intact.

-

-

54 minutes ago, MESSIS said:

Thank you old good friend. So painting hearts black isnt necessary.

Christos.

Repeatedly tarring the cordage would turn the cordage and the hearts and deadeyes virtually black in a very short while. Viewed from a "scale distance," they would certainly appear black, or very nearly so.

-

Service was employed not only to protect the cordage or cable from chafe, but also, and in far larger measure, to prevent weathering and rot which would weaken it substantially. Worming, parcelling, and serving, with each layer well tarred, prevented UV degradation and moisture intrusion. Shrouds were customarily served their entire length, while stays, which had to carry sails fastened to the stays and running up and down them, which made chafe inevitable, frequently were only served at their ends with the "working" length of the stay left bare. When that wore down, they just replaced the stay.

Where there were areas of substantial chafe, as where a yard, line, or sail might come in regular contact with a shroud, other chafe prevention gear was used, such as puddenings or baggywrinkle installed on top of the served shroud or on the offending yard, line, or sail, or both. This latter chafe protection was common practice. It's a whole lot easier to fasten a new puddening or length of baggywrinkle when it needs replacing than to re-serve even a short length of served standing rigging that has chaffed through. It's also a lot more effective than letting a sail chafe against a tarred shroud and get all black and sticky with tar, which certainly makes it even less fun to hand and furl for the crew working aloft.

- captain_hook, mtaylor and allanyed

-

3

3

-

-

1 hour ago, mtaylor said:

Are the oars actually just about touching when rowing on the real vessel? I've wondered about that ever since seeing "Ben Hur" if they were close or separated.

They'd pretty much have to be very close and rowed in perfect unison. What's apparently inaccurate in the Ben Hur galley scene is when the rowers start "falling out" from exhaustion, what happens to their oars? Nothing, in the movie. In real life, a dropped oar's loom would likely immediately start flailing about inboard, making it impossible for adjacent rowers to row in unison, and the blade outboard would foul the blades of adjacent oars, creating a mess, and probably a "chain reaction" type of mess at that. Imagine what below decks would look like in combat when the vessel was rammed amidships. I guess naval tactics in that age boiled down to "ram and hold fast, board and kill all the other guys, then hope there was at least one ship left to make it to shore on.

- J11, mtaylor and EricWilliamMarshall

-

3

3

-

14 hours ago, Richard Braithwaite said:

Before I embarked on this project I built a section model to see if I could fit machinery below the central walkway to operate the oars. This remains an option for this model which is why the canopy and internal hull structure is removable (see bolts in the above pics). The machinery is quite crude (I would aim to improve on that with the full model) but did demonstrate that independent control of port and starboard oars would be possible with machinery that would give an elliptical oar path with the right stroke length.

Simply amazing! Are you talking about a radio-controlled galley? (Maybe even with a speaker for the sound effects of the cadence drummer and lashing whips?) How cool is that, or what?

-

-

Definitely a "keeper!" Thanks for sharing. I've not seen this one before.

My first stop in the dictionary department has always been the Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea, from the publishers of the Oxford English Dictionary. I have a hardcover first edition, but it's now out in a later second edition, hardcover and paperback, and, also accessible on line by subscription:

https://www.amazon.com/Oxford-Companion-Ships-Reference-Collection/dp/0198800509

https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199205684.001.0001/acref-9780199205684

-

1 hour ago, ragove said:

The instructions in the yellow box kits were like: take the pieces of wood and turn them into a ship. Refer to the plans for hints. Also be prepared to purchase 1000s more blocks as we don’t give you nearly enough.

And those "yellow box" kits were some of the best available back in those days! As for coming up short on blocks, there wasn't any internet or email or overnight shipping to even begin to buy more blocks. We had to make them ourselves!

-

Building these old Model Shipways kits can be a real education. You really had to bring some skill to the table to build a ship model in the days before laser-cut parts and internet advice forums. Once they had a couple of these old kits under their belts, the old timers were all "scratch-builders." These days, kit models are assembled, not built!

-

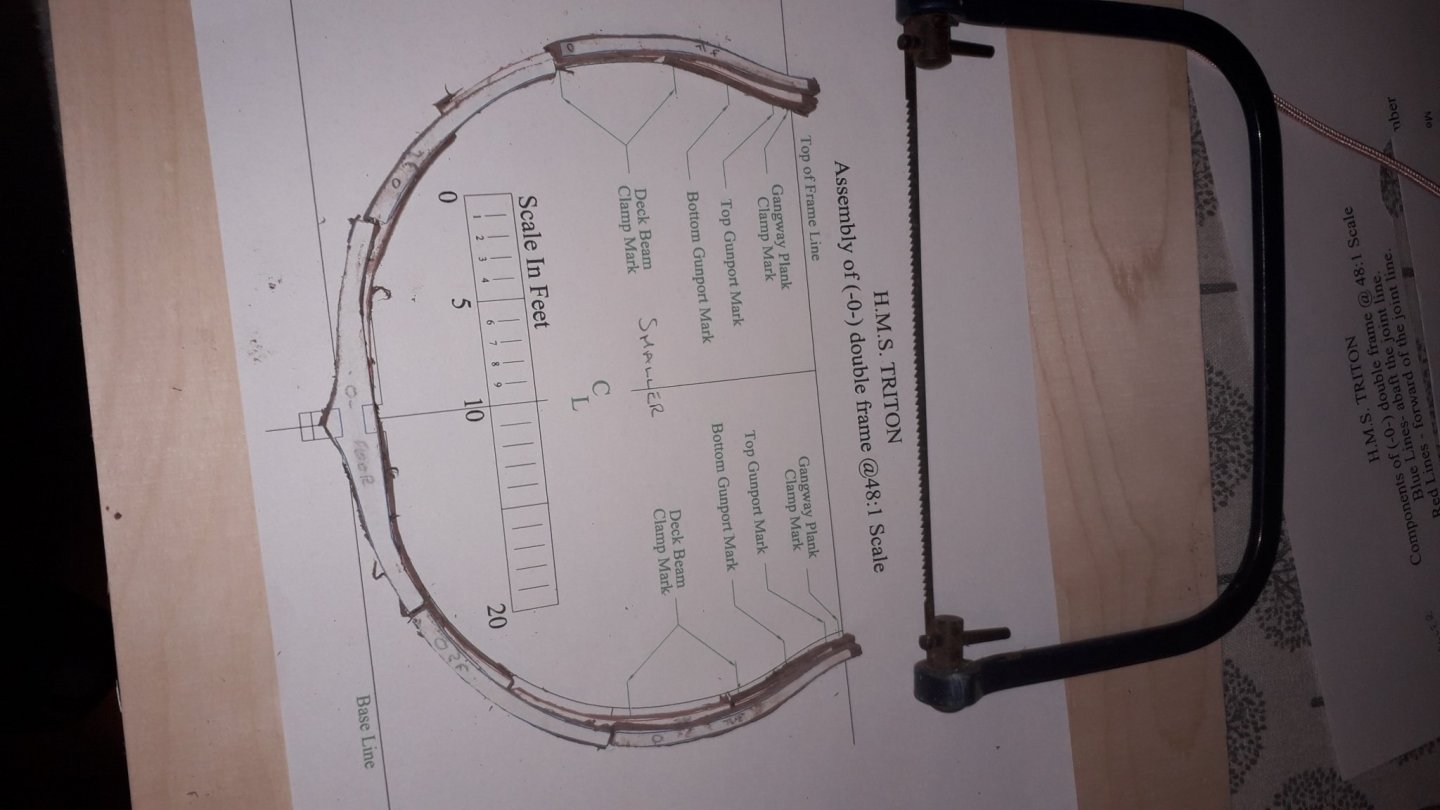

If you haven't done so by now, may I suggest you consider using a much smaller and finer toothed blade on your coping saw. Really good coping saws cost as much as a cheap scroll saw, but you might find a better coping saw, if not a scroll saw, a good investment, considering the amount of use you would get out of it on this build and in the future. An investment in such tools could well pay for itself in money saved on sandpaper! A good cutting tool is always a better option than sanding in terms of overall cost, efficiency of use, and quality of the result.

Watch the Knew Concepts saws video on their web page: https://www.knewconcepts.com/Coping-saws.php A bit pricey, but you get what you pay for. For around $100 USD, one of these will change your life. I don't know if they are readily available in the UK, but they should be easy enough to order on line. You're doing great work with the one pictured above, but it's got to be a bit like trying to sharpen a pencil with a broad axe !

- Edwardkenway and mtaylor

-

2

2

What would be the correct colour of unpainted Wood?

in Painting, finishing and weathering products and techniques

Posted · Edited by Bob Cleek

High traffic areas would much more likely be darker than low traffic areas because the high traffic areas would have a lot more tar tracked over them from the sailors' feet.

The color of any unfinished wood depends upon the species of the wood and the degree of weathering. There wasn't ever any unfinished wood on ships and boats, save for teak decks, which came on the scene rather late and were, essentially, "sacrificial," in that they were holystoned (sanded) and washed down with saltwater regularly to keep them "bright" and bleached. Wood was always protected with something to preserve it, be that bitumen, pitch, pine tar, vegetable oils, and paints and varnishes. Most of the earlier coatings were dark and tended to result in a blackish color after a short while in service.